Abstract

In the current era of accelerated economic growth, project success – successful completion of the final product for which the project was initiated – is the ultimate goal of every organisation. It is essential for organisations to keep project-based employees motivated and focused on successfully accomplishing the project objectives. This research examined the association between psychological empowerment of project-based employees and project success. We explored the mediating role of knowledge sharing to explain the intervening mechanism between psychological empowerment and project success. We also tested the moderating role of employee creativity along with conditional indirect effects by performing a moderated mediation analysis. Using a time-lagged research design, multiple-source field data (N = 327) were collected from employees of project-based organisations in Pakistan. The findings of the study showed a positive association between psychological empowerment and project success and significant mediation of knowledge sharing. Project employees with high creativity are likely to achieve project success when they possess higher psychological empowerment too. Results concluded that psychological empowerment is positively associated with project success directly as well as indirectly through its impact on knowledge sharing. The study has its importance and implications for management specialists and project employees at all levels.

Introduction

Research has demonstrated that project success – successful completion of the final product for which the project was initiated is a key factor in achieving a competitive advantage in terms of performance and output (Baccarini, Citation1999). Given the importance of project success in anticipating successful work outcomes, previous studies have examined its role in terms of political stability (Kwak, Citation2002), flexible project planning (Khan et al., Citation2000), satisfaction of stakeholder groups (Albert et al., Citation2017) and connection of project management practices with project outcomes (Ajmal et al., Citation2017). However, limited studies have examined the role of psychological abilities, specifically employees’ psychological empowerment, that may potentially interact with project success (Rowlinson & Cheung, Citation2008) in project-based organisations (Sok et al., Citation2018), particularly the combination of mediating and moderating mechanisms in the aforementioned relationship.

Theorists have argued that psychological empowerment, as a work-related attitude, is comprised of multiple psychological phenomena including cognitive, evaluative, and behavioural aspects (Kazlauskaite et al., Citation2011). The provision of empowerment enhances intrinsic motivational resources of the employees; thus, they get motivated to exhibit high levels of performance (Arshadi, Citation2010). Thus, as a result of empowerment, the employees tend to perform well as well as to share knowledge. Basing on the above argument, we posit that the success of a project could be attributed to multiple psychological influences. These employee attitudes and behaviours could shape up the success or failure of a project. Depending on the unique nature of each project, it could be argued that extending psychological empowerment to the project employees would motivate them to perform well and achieve the project goals successfully. The employees who feel psychologically empowered, they experience its constituent components, namely meaning, competence, self-determination and impact in their jobs (Barton & Barton, Citation2011; Spreitzer, Citation1995). The empowered employees perform well in their jobs as they happen to get crucial resources that are necessary to shape up their performance (Javed et al., Citation2017).

The main contributions of this study are as follows: First, we focus on the contribution of psychological empowerment in enhancing the level of project success. It is argued that project-based organisations are mostly plagued with bureaucratic culture and red-tapism (Turner & Keegan, Citation1999). This inherent bureaucracy paves the way for delays and failures in the timely completion of the projects. Thus, empowerment is needed for the successful execution of the projects. Indeed, the matrix structure of the organisations, which is a contemporary organisational structure, is suitable for project organisations as it gives empowerment to the employees (Morris, Citation1994). Second, knowledge sharing is studied as an intervening variable which mediates the empowerment - project success link. As psychological empowerment is characterized by meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact, it can be argued that empowered employees are more likely to share their work-related knowledge with their colleagues because they find themselves knowledgeable and autonomous and feel that their job is meaningful and does have an impact on the society. The acute project problems could be solved with this knowledge sharing and resultantly, this would have a positive influence on the execution and completion of project goals (Singh et al., Citation2018). Third, we analyse the moderating role of employees’ creativity. Creativity is tested as a boundary condition influencing psychological empowerment and project success link because the literature suggests that professionally creative employees are crucial for knowledge sharing practices and performance (Kremer et al., Citation2019). Moreover, our study is placed in Pakistan. We collected data from Pakistani project-based organisations operating in different sectors. Research on Pakistani project-based organisations is sporadic. Thus, we address an important contextual gap as well.

Theory and hypotheses

Psychological empowerment and project success

Psychological empowerment can be defined as ‘intrinsic task motivation reflecting a sense of self-control in relation to one’s work and an active involvement with one’s work role’ (Seibert et al., Citation2011, p. 981). The construct of empowerment has attracted tremendous scholarly interest in the last few decades. Numerous subdomains of management and psychology, including leadership, group performance, task performance, motivation, decision-making, creativity etc. incorporated the study of psychological empowerment because it is closely linked with attitudes and behaviours of individuals, groups, and organisations. Four cognitions make up the concept of psychological empowerment: meaning, self-determination, competence, and impact. Specifically, meaning refers to the degree to which the work itself is meaningful for the employee, self-determination is the sense of freedom and autonomy possessed by an employee regarding his/her control over the work, competence is the degree to which an employee is confident about one’s ability to perform the required job tasks, and impact is the feeling that an individual employee’s accomplishment makes a significant contribution toward the unit goals (Seibert et al., Citation2011).

Initially, notion of empowerment was intellectualized as a component of a relational or power-sharing viewpoint (Burpitt & Bigoness, Citation1997; Spreitzer & Doneson, Citation2005). The roots of the concept of empowerment can be traced back to several leadership theories e.g., Ohio State Behavioural Studies of Leadership on “consideration” (Fleishman, Citation1953), participative leadership studies (Locke & Schweiger, Citation1979; Vroom & Yetton, Citation1973), supportive leadership (Bowers & Seashore, Citation1966), Fiedler’s Contingency Theory of Leadership, etc. Contrary to the initial consideration of empowerment as an element of power-sharing, later, it was argued that the conceptualization of empowerment must also take into account the motivational aspect of empowerment on the subordinates (Conger & Kanungo, Citation1988). Later, empowerment was linked with intrinsic task motivation (Thomas & Velthouse, Citation1990). Moreover, the construct of empowerment was extended to the team level by Kirkman and Rosen (Citation1997, Citation1999). They argued that highly-empowered teams are highly effective and experience more autonomy which would lead to team success. Empowerment leads to the realization of job tasks as more meaningful and impactful which leads to intrinsic motivation.

The self-determination dimension of psychological empowerment autonomizes the employees, and they perceive themselves of being in control of their work, thus also enriching the decision-making process (Valentine et al., Citation2018). Researchers like Petter et al. (Citation2002) suggest seven dimensions of employee empowerment as follows: ‘power, decision-making, information, autonomy, initiative and creativity, knowledge, skills and responsibility.’ The fulfillment of all these needs provides intrinsic motivation to the employees, and they persevere and become attached to their job and perform well (Baird et al., Citation2018).

The link between psychological empowerment and project success can be explained through job demands-resources (JD-R) model (Bakker et al., Citation2003; Bakker et al., Citation2003) which posits that two types of work environments, i.e., job demands and job resources influence the employee performance. In this study, we suggest that psychological empowerment of project-based employees plays as a job resource. Job resources refer to ‘those physical, psychological, social or organisational aspects of the job that are either/or: functional in achieving work goals, reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, and stimulate personal growth, learning, and development’ (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007, p. 312). Employee performance, well-being, psychological empowerment, and participation in decision-making are a few examples of such job resources (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). The Resource-Based View of the Firm (RBV) (Barney, Citation1991) emphasizes the importance of resources for a firm’s competitive advantage. RBV explains that psychological empowerment could facilitate firms in obtaining a competitive advantage. García-Juan et al. (Citation2019) note that empowered employees are more responsive to the needs of the customers and they deal with the customers with more cordiality which ultimately leads toward elevated organisational performance. Recovery literature contends that empowerment facilitates service recovery and resultantly, customers and employees are more satisfied (Bowen & Lawler, 1995, 2006). Empowerment practices exhibit advantageous effects on several individual and organisational outcomes e.g., productivity, quality, sales and service, and organisational performance (Birdi et al., Citation2008; Logan & Ganster, Citation2007; Patterson et al., Citation2004; Wallace et al., Citation2011).

Researchers argue that psychological empowerment significantly contributes to the overall improvement in productivity (e.g., project productivity) (Ul Haq et al., Citation2018). As psychological empowerment is characterized by meaning, the psychologically empowered employees find their job tasks as profoundly meaningful and impactful. Thus, enthusiasm kicks in and project employees use a variety of creative ways to achieve their tasks (Javed et al., Citation2017). As project work is mostly time-bound; therefore, project employees usually come across tasks that carry specific deadlines (Nordqvist et al., Citation2004). Empowered employees have the competence to execute the tasks in a timely manner. Chandra et al. (Citation2011) found a significant positive effect of stakeholders’ psychological empowerment on project success. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: Psychological empowerment is positively associated with project success.

The mediating role of knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing is defined as ‘the act of making knowledge available to others within the Organisation’ (Ipe, Citation2003, p. 341). It could be elaborated on as the sharing of task-related thoughts, information, and ideas among the team members (Srivastava et al., Citation2006). Being a principal constituent of knowledge management, knowledge sharing facilitates in ‘codifying the repository of available knowledge in an organisation and increasing it over time’ (Srivastava et al., Citation2006, p. 1241). Knowledge sharing, in the team context, is a vital team process because in case intellectual resources are not shared, they become depleted and could not be utilized to their full extent (Argote, Citation1999). The current corporate world is marked by knowledge-intensive business activities. In this knowledge-driven business environment, it has become imperious for organisations to develop and manage critical knowledge (Wang et al., Citation2019). Previous research has identified numerous employee-level and organisation-level antecedents of knowledge sharing including trust, perceived value of knowledge, rewards (tangible and intangible), self-efficacy, etc. (Chang & Chuang, Citation2011; Hsu et al., Citation2007; Kankanhalli et al., Citation2005; Wang & Haggerty, Citation2009). Psychological empowerment is a critical factor in facilitating the provision and distribution of knowledge among organisational members (Amichai-Hamburger, Citation2008; Psoinos et al., Citation2000). Psychological empowerment enhances interpersonal trust which then translates into knowledge sharing (Füller et al., Citation2009). Although, many pieces of research have examined the effect of empowering leadership on knowledge sharing (Barachini, Citation2009; Field, Citation1997; Srivastava et al., Citation2006; Xue et al., Citation2011); however, how psychological empowerment impacts organisational performance through knowledge sharing is a pertinent question that remains to be answered. Empowerment of employees is, thus, essentially about managers and fellow workers sharing the knowledge and information about organisational direction and performance (Wang et al., Citation2019, p. 1043).

In a project-oriented context, knowledge sharing is the provision of task information to clients, expertise, or receiving feedback on project/product from project managers (Cummings, Citation2004; Huan et al., Citation2017). Drawing upon the JD-R model, we posit that employees will share relevant job-related knowledge when they are psychologically empowered because these employees enjoy sharing knowledge and positively create the desired outcomes (Lin, Citation2007). Job demands, at times, might turn into job stressors and these job stressors take their toll when performing job-related tasks. It requires a high expenditure of cognitive or emotional effort, from which employees do not easily recover (Meijman & Mulder, Citation1998). Achieving and maintain high levels of performance for project-oriented employees are taxing demands. Psychological empowerment acts as a job resource that reduces job demands and facilitates personal growth, and learning and development (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2011). This is in line with Hackman and Oldham (Citation1980) job characteristics model (JCM) that describes autonomy, feedback, and task significance as resources from which motivation could be sought. This also corresponds with the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989) which states that employees attempt to seek and maintain the resources. Resources are important in their own right and are used to accomplish other valued resources (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2011). Decision making is improved in response to knowledge sharing as generation of alternatives is enhanced and more comprehensive knowledge is utilized (Stasser & Titus, Citation1985). Team coordination also enhances in response to knowledge sharing because of mutual understanding and utilization of knowledge (Srivastava et al., Citation2006). These phenomena lead to enhanced organisational performance.

As project team members have to work in close collaboration with their customers, and they ought to meet the requirements of the customers, empowered employees are critical resources for that purpose. Via knowledge sharing, knowledge is exchanged and networks are formed among organisational members and managers. This leads to an enhancement in organisational output (Rafique et al., Citation2018). In the context of project management in project-based organisations, relatively error-free project execution could take place because of low chances of mistakes owing to knowledge sharing (Müller & Stocker, Citation2011); high-quality project results, thus, would be gained. Basing on the above findings, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between psychological empowerment and project success.

The moderating role of employee creativity

Employee creativity is the generation of novel and useful ideas or solutions to problems (Amabile, Citation1983). There is an increasing interest in research on how leaders tend to influence and enhance the creativity of their employees (Zhou & Shalley, Citation2003). It becomes even more challenging for leaders of teams like project teams. Project teams, oftentimes, have to accomplish their tasks creatively and innovatively. Individual team members come up with creative ideas, and a conducive environment and leadership which encourages such creation of novel ideas are important (Dong et al., Citation2017). Creative individuals come up with novel responses in dealing with the job tasks (Amabile, Citation1983), e.g., devising new procedures for carrying out tasks, or identifying products or services to better meet customer needs (Zhou & Shalley, Citation2003). We posit that creative individuals will also have a strong aspiration to share knowledge and skills, as they apply novel and useful ideas in their work (Shalley et al., Citation2004). Knowledge workers and managers disseminate and share experiences, knowledge, and techniques (Wu et al., Citation2012). By actively sharing knowledge, they reveal the value of knowledge which enhances competitiveness and ultimately organisational performance (Dalkir, Citation2013).

In a meta-analysis by Jiang et al. (Citation2012), the authors found significant effects of motivation-enhancing practices, opportunity-enhancing practices, and human capital on voluntary turnover, operational outcomes, and financial outcomes. These variables are closely related to empowerment practices; thus, it is elucidated that empowerment might lead to improved organisational performance. Morgan Tuuli et al. (Citation2012) found varying degrees of the positive relationship of task-orientated leadership and person-orientated leadership with three types of project teams, i.e., contractor teams, consultant teams, and client teams. Employees who feel themselves psychologically empowered experience a sense of ownership regarding their organisation and regarding their job responsibilities. Empowered employees are more likely to share their creative ideas and knowledge with the management of the projects because they experience more autonomy and feel more comfortable (Baird et al., Citation2018). Autonomy induces the employees to look for creative and innovative solutions for the problems. The creative ideas might include cost-cutting measures and innovative solutions to the complex problems in project management, which might enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the project (Baird et al., Citation2018). Project performance is enhanced in response to enhanced knowledge sharing principally because of two key reasons: better decision making and coordination (Srivastava et al., Citation2006).

Therefore, we expect a positive moderating effect of employee creativity between psychological empowerment and knowledge sharing. We thus predict:

Hypothesis 3: Employee creativity will moderate the indirect effect of psychological empowerment on project success through knowledge sharing. Specifically, the indirect effect is higher for employees who are more rather than less creative.

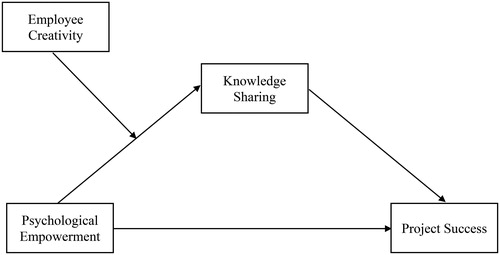

The conceptual framework is presented in .

Method

Study context: project-based organisations in Pakistan

This study targeted employees working in three main sectors that are telecommunications, research & development, and construction. These sectors were selected for two main reasons. First, these industries are projected-intensive and represent a major share of ongoing projects in Pakistan. According to BMI research, Pakistan is one of the 10th fastest emerging markets and recent China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is another project hinting toward 5.4% economic growth in Pakistan since 2018. Similarly, Pakistan Economic Survey (2018–2019) indicated that a revenue of more than 4.1 billion Pak rupees has been generated through telecommunication projects related to software development, website development, medical transcription, game development and system informatics whereas R & D is contributing 0.397% of the total gross domestic product which is the highest in previous nine years. Second, these organisations carry employees who are innovation-oriented and are knowledge-workers as they are responsible for knowledge exchange processes (Butt et al., Citation2019). Thus, the sample we employed consisted of employees who are highly relevant for our study settings which pertain to project management.

Sample and procedure

The study targets employees and their respective supervisors in project-oriented business firms in three main cities (Faisalabad, Islamabad, and Rawalpindi) of Pakistan. By tapping multiple firms in the survey, we aimed to extend the generalisability of the results (Katsikea et al., Citation2011). Before the data collection process, we met administrative managers/human resource managers of the selected industries and got their approval to distribute survey questionnaires. Initially, 26 business firms were contacted and 22 firms allowed us to collect the data. The respondents were professional employees from various departments of these firms related to public relations, marketing, procurement, project management, IT, engineering, research and development, finance, audit, security, HR and information systems. Using convenience sampling technique, we administered field surveys in 22 project-based organisations. To reduce the potential of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), independent measures (self and supervisory reports) were used by employing a time-lagged design. At time 1, we distributed 630 questionnaires in English to full-time project-based employees. We asked them to report their job identity, demographics (gender, age, qualification, work experience as a project employee, organisation) and opinion about psychological empowerment, knowledge sharing, and project success. A cover letter was attached to each survey explaining to them the objective of the research. We indicated that the participation is voluntary and assured them of anonymity and confidentiality as respondents were not required to mention their names on the responses. In addition, self-addressed unmarked envelopes were included for employees to deposit their responses and they were instructed to place their completed survey in the envelope. A total of 486 employees filled out the completed questionnaires yielding a response rate of 77.14%. After a gap of four weeks, at time 2, employee creativity was separately assessed using the supervisor’s ratings. Therefore, 128 immediate project managers/supervisors of these respondents were contacted in order to rate their employees’/subordinates’ creativity. To match the responses from employees, supervisors recognised them through their job identity we took at time 1. We received 327 completed matching responses (a supervisor/project manager rated an employee who had also turned in a survey). On average, each supervisor/project manager rated the creativity of almost four employees for a 67.28% response rate.

Most of the respondents (68.2%) were male. Fifty-two percent had completed their undergraduate (16 years) education, and 43.1% were graduates (18 years). Approximately 57% of the respondents belonged to public sector organisations, and the rest were from the private sector. In the age category, 46.2% of the respondents were 26 to 33 years old and most of them (41.6%) had project-oriented work experience between 6 and 10 years.

Measures

Psychological empowerment was measured by the 11-item scale developed by Spreitzer (Citation1995) with scale anchors ranging from “1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.” The sample item included, “The work I do is meaningful to me.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.84. Knowledge sharing was measured by a 5-item scale developed by Cummings (Citation2004). One sample item is “How often did you share general overviews (e.g., project goals, milestone estimates, or member responsibilities) during the project.” The anchors ranged from “1 = never to 5 = a lot.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78. Employee creativity was measured using a 13-item scale adopted from Zhou and George (Citation2001) using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.” We modified the scale in a project-oriented context to obtain a supervisor’s opinion. Example of the items included “This employee has often new and innovative ideas for project development.” Alpha reliability for the scale was 0.92. To measure project success, we used a 6-item scale developed by Robey et al. (Citation1993) consistent with Eichhorn and Tukel (Citation2018) with little modification. The sample item included “The amount of work I produced.” Scale anchors ranged from “1 = very low to 5 = very high.” Cronbach’s alpha for all items was 0.75. We controlled for employees’ experience and educational level since they could influence project success.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

Before testing our main hypothesis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to establish the discriminant validity of our measurement scales. Overall measurement model provided excellent fit to the data χ2/df = 2.51; incremental fit index (IFI) = .93; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = .92; comparative fit index (CFI) = .93 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06, compared to three-factor model (combining psychological empowerment and knowledge sharing to one factor; χ2/df = 5.44; IFI = .85; TLI = .82; CFI = .85; RMSEA = .11) and the one-factor model (loading all the indicators on to one single factor; χ2/df = 6.64; IFI = .74; TLI = .71; CFI = .74; RMSEA = .13).

Common method variance (CMV)

Owing to the use of self-reported measures, CMV could be a potential problem. We, however, took several remedial measures to avoid this bias. First, we used a time-lagged survey design to create a temporal separation between the measurement of our main variables (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Second, employee creativity was measured by using responses from the supervisor, thus limiting the single-source bias. Third, the respondents were guaranteed about anonymity and confidentiality of their responses and were asked to answer the questions as honestly as possible. Thus, social desirability bias was reduced (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Finally, we performed two ex-post CMV tests on our data. First, given Harman’s single-factor test, the highest Eigenvalue explained only 30% of the variance, which is well below the conventional level of 50%. Second, we performed the unmeasured latent factor model on our study variables (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Results revealed a common factor value of 0.43, which represents a common variance of (.43)2 = 0.1849 or 18.49 percent, which is below the threshold level of 25% as suggested by Williams et al. (Citation1989). Thus, CMV was not a major problem in the study (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Tests of hypotheses

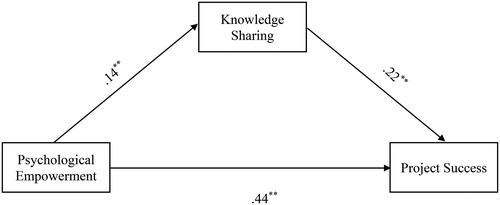

shows descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the variables. To test hypothesis 1 and 2, we used The PROCESS macro for SPSS mediation model (cf. Preacher et al., Citation2007) with 5,000 bootstraps resamples and 95 percent confidence interval for testing the indirect, total and direct effects. This method provides non-parametric estimates and is considered to be more appropriate than the traditional regression mediation approach, as recommended by the literature (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2004). Hypothesis 1 stated that psychological empowerment was positively associated with project success. Given results in and , hypothesis 1 was supported (β = 0.44, p < 0.01). Similarly, the indirect effect of psychological empowerment on project success through knowledge sharing was significant (β = .032; p < 0.05) as upper and lower limit of 95% bootstrap confidence interval did not contain zero (.009 − .070) which confirms the mediation of knowledge sharing in the model. Thus, hypothesis 2 was supported. We found no significant impact of control variables on project success; therefore, we did not include them in further analysis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Table 2. Ordinary least squares regression coefficients from moderated mediation model.

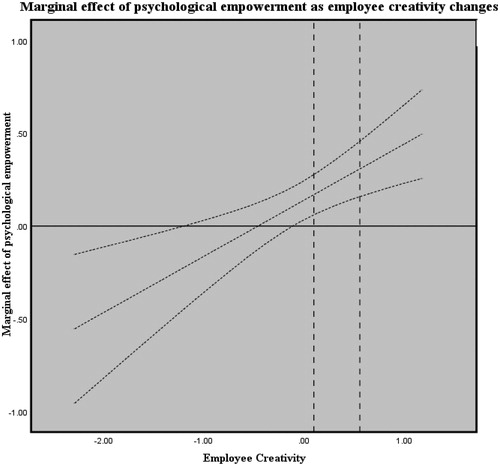

To test Hypothesis 3, PROCESS model 7 was used to investigate the prospect of moderated mediation. According to , the interaction between psychological empowerment and employee creativity reported a significant positive interaction effect (β = 0.30, p < .01). The overall model showed that the index of moderated mediation was significant as the 95% bootstrap confidence interval (.018 − .117) did not include zero. Furthermore, we also established the conditional indirect effects of psychological empowerment on project success via knowledge sharing at three values of employee creativity. One SD below the mean = −.441 was insignificant because upper and lower limits of the confidence interval (−0.28 − .028) included zero. For mean = .098 and 1 SD above the mean = .559, the results were significant as the bootstrap 95% confidence interval did not contain zero ([.012 − .063] and [.027 − .110] respectively).

For formulating a conclusion about the moderated mediation model, we used the Johnson Neyman technique recommended by Hayes (Citation2018) for investigating the conditional indirect effects of the moderating variable employee creativity (Aiken et al., Citation1991). graphically represents these indirect effects with an upper and lower limit of 95% confidence interval. According to , psychological empowerment had a significant relationship with project success at any value of employee creativity situated between -2.28 to -1.07 and -.11 to 1.17. The indirect effect via knowledge sharing was significant when the level of employee creativity was situated between medium (Indirect effect = .036 with a 95% CI of [.012 − .063]) and high (Indirect effect = .067 with a 95% CI of [.027 − .110]) levels. Since the majority of employee creativity values determining the project success in our study were pronounced between the 95 percent confidence interval bound; therefore, hypothesis 3 was fully supported.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated that psychological empowerment favourably predicts project success. Our results are consistent with previous research findings by suggesting that willingness to perform enhances in response to psychological empowerment because psychological empowerment provides the motivational drive to be successful (Dust et al., Citation2018). García-Juan et al. (Citation2019) found a positive effect of structural empowerment and psychological empowerment on organisational performance. Rowlinson and Cheung (Citation2008) formulated a “stakeholder management model,” which links team empowerment and individual empowerment with project objectives. In line with JCM, we suggest that when employees are provided with autonomy, when employees find their tasks significant and feel that their role makes a difference in the accomplishment of the unit’s goals, then they experience responsibility and high levels of motivation. They display high levels of performance in response to the motivation which leads to elevated organisational performance. The positive effect of psychological empowerment could also be explained through self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000) as employees are motivated to grow when their innate needs for competence and autonomy are fulfilled. Empowered employees find themselves competent to perform their jobs and find their jobs meaningful which motivates them to outperform those who are not empowered. These elevated levels of performance are translated into project success in project-based organisations.

Moreover, knowledge sharing significantly mediates this relation because organisational members draw a great deal of intrinsic motivation from the psychological empowerment they are provided with; they, therefore, engage in knowledge sharing, which leads to enhanced organisational performance and ultimately, project success (Law & Ngai, Citation2008). At the organisational level, the importance of knowledge sharing cannot be overestimated; it could be a critical factor in differentiating between successful and unsuccessful projects. Further, we uncovered the moderating role of employee creativity between psychological empowerment and project success. Employees with high levels of creativity lead to success by implementing creative ideas in achieving competitive advantage (Kremer et al., Citation2019). Consequently, project employees high in creativity are likely to engage in knowledge sharing behaviours when they are psychologically empowered.

Theoretical implications

This study advances the literature on knowledge sharing and employee creativity in four important ways. First, our study provides implications for theory by testing the hypothesized relationship of our study variables, which postulates that employee’s project success is greatly affected by their creativity at work. We add to the literature by examining employee creativity with the conditional indirect effects of knowledge sharing. Our findings reveal that employee’s positive and creative attitude motivates them for better performance by displaying knowledge sharing behaviour. In certain situations, knowledge sharing makes employees make better decisions through emotion-focused coping strategies like psychological empowerment helps to counter the variations in the working environment and in achieving project success. Second, we extend existing research on psychological empowerment and project success by incorporating knowledge sharing as a mediating mechanism in this study. Third, this paper strengthens our understanding and adds to scant literature by the operationalization of employee creativity to influence the relationship between psychological empowerment and project success through a moderated mediation approach. Our study emphasized that creative employees play as a motivating force for themselves and their organisations; therefore, they prompt to share knowledge with each other, which in turn leads to project success. Therefore, the higher the creativity, the higher knowledge sharing will take place. Finally, given the Pakistani context of this study, we contribute to the literature by empirically testing the relationships among psychological empowerment, knowledge sharing, employee creativity, and project success and validate our model in a non-US/non-Western context, i.e., Pakistan.

Managerial implications

This study has several practical implications. Due to the direct association between psychological empowerment and project success, the current study suggests that managers should be mindful of employee’s psychological well-being and pay attention to practices that empower employees. As employee creativity has a powerful impact on the employee’s psychological ability to empower them and make their projects successful, in this regard, the tailoring technique recommended by Tims and Bakker (Citation2010) can be used by obtaining employees’ feedback on job-demand resources questionnaires. Moreover, managers must be aware of the challenges that some of their employees may face on a daily basis and help to foster the resilience they may need to persevere when faced with such adversity, in order to meet with project success

Similarly, managers need to take into account multiple factors like employees’ psychological needs, creative self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, and job satisfaction that are closely related to individual work values. Relying on a single factor may even have a detrimental impact on employee creative performance. To promote creativity, job task designing and supportive attitude by managers is crucial for employees in achieving project success. Managers should develop the right group norms by creating a supportive culture to share knowledge among teams (Kremer et al., Citation2019). It also incorporates a supportive work environment that encourages quality relationships with peers in the form of recognition and rewards.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study is not without limitations. According to the cognitive appraisal theory, individuals go through appraisal processes, including emotions and dispositional coping styles (Tomaka et al., Citation1997). In this study, we did not explicitly analyse the role of these dispositional styles like goal selection, performance appraisals and compensation. Moreover, we selected project-based organisations for the study. Future studies may replicate this study in other industries. Finally, causality is also a limitation in our study because the study is without any experiments or assignments. Future researchers may analyse the hypothesized relationship in a longitudinal study. Future researchers might use the manager’s view on project success in addition to the perception of the employees themselves. This might fetch a more objective perspective on this construct. There may be other important mediation and moderation mechanisms to explain the relationship between psychological empowerment and project success. Therefore, future studies may explore the mediating role of job involvement and the moderating role of culture to further explain the link between psychological empowerment and project success.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Ajmal, M., Malik, M., & Saber, H. (2017). Factor analyzing project management practices in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 10(4), 749–769. doi:10.1108/IJMPB-03-2017-0027

- Albert, M., Balve, P., & Spang, K. (2017). Evaluation of project success: A structured literature review. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 10(4), 796–821. doi:10.1108/IJMPB-01-2017-0004

- Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 357–376. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2008). Internet empowerment. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(5), 1773–1775. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2008.02.001

- Argote, L. (1999). Organizational learning: Creating, retaining, and transferring knowledge. Kluwer Academic.

- Arshadi, N. (2010). Basic need satisfaction, work motivation, and job performance in an industrial company in Iran. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1267–1272. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.273

- Baccarini, D. (1999). The logical framework method for defining project success. Project Management Journal, 30(4), 25–32. doi:10.1177/875697289903000405

- Baird, K., Su, S., & Munir, R. (2018). The relationship between the enabling use of controls, employee empowerment, and performance. Personnel Review, 47(1), 257–274. doi:10.1108/PR-12-2016-0324

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., De Boer, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2003). Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(2), 341–356. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00030-1

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Taris, T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. (2003). A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(1), 16–38. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.10.1.16

- Barachini, F. (2009). Cultural and social issues for knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13(1), 98–110. doi:10.1108/13673270910931198

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. doi:10.1177/014920639101700108

- Barton, H., & Barton, L. C. (2011). Trust and psychological empowerment in the Russian work context. Human Resource Management Review, 21(3), 201–208. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.02.001

- Birdi, K., Clegg, C., Patterson, M., Robinson, A., Stride, C. B., Wall, T. D., & Wood, S. J. (2008). The impact of human resource and operational management practices on company productivity: A longitudinal study. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 467–501. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00136.x

- Bowen, D. E., & Lawler, E. E. III, (1995). Empowering service employees. MIT Sloan Management Review, 36(4), 73–84.

- Bowen, D. E., & Lawler, I. I. I., E. E. (2006). The empowerment of service workers: What, why, how, and when. Sloan Management Review, 33(Spring), 31–39.

- Bowers, D. G., & Seashore, S. E. (1966). Predicting organizational effectiveness with a four-factor theory of leadership. Administrative Science Quarterly, 11(2), 238–263. doi:10.2307/2391247

- Burpitt, W. J., & Bigoness, W. J. (1997). Leadership and innovation among teams: The impact of empowerment. Small Group Research, 28(3), 414–423. doi:10.1177/1046496497283005

- Butt, M. A., Nawaz, F., Hussain, S., Sousa, M. J., Wang, M., Sumbal, M. S., & Shujahat, M. (2019). Individual knowledge management engagement, knowledge-worker productivity, and innovation performance in knowledge-based organizations: The implications for knowledge processes and knowledge-based systems. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 25(3), 336–356.

- Chandra, H. P., Indarto, I., Wiguna, I. P. A., & Kaming, P. F. (2011). Impact of stakeholder psychological empowerment on project success. IPTEK the Journal for Technology and Science, 22(2), 65–73. doi:10.12962/j20882033.v22i2.63

- Chang, H. H., & Chuang, S.-S. (2011). Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Information & Management, 48(1), 9–18.

- Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 471–482. doi:10.5465/amr.1988.4306983

- Cummings, J. N. (2004). Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organization. Management Science, 50(3), 352–364. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1030.0134

- Dalkir, K. (2013). Knowledge management in theory and practice. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuıts: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), 01–09. doi:10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Dong, Y., Bartol, K. M., Zhang, Z. X., & Li, C. (2017). Enhancing employee creativity via individual skill development and team knowledge sharing: Influences of dual‐focused transformational leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(3), 439–458. doi:10.1002/job.2134

- Dust, S. B., Resick, C. J., Margolis, J. A., Mawritz, M. B., & Greenbaum, R. L. (2018). Ethical leadership and employee success: Examining the roles of psychological empowerment and emotional exhaustion. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 570–583. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.02.002

- Eichhorn, B., & Tukel, O. (2018). Business user impact on information system projects. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 11(2), 289–316. doi:10.1108/IJMPB-02-2017-0016

- Field, L. (1997). Impediments to empowerment and learning within organizations. The Learning Organization, 4(4), 149–158. doi:10.1108/09696479710170842

- Fleishman, E. A. (1953). The description of supervisory behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 37(1), 1–6. doi:10.1037/h0056314

- Füller, J., MüHlbacher, H., Matzler, K., & Jawecki, G. (2009). Consumer empowerment through internet-based co-creation. Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(3), 71–102. doi:10.2753/MIS0742-1222260303

- García-Juan, B., Escrig-Tena, A. B., & Roca-Puig, V. (2019). The empowerment–organizational performance link in local governments. Personnel Review, 48(1), 118–140. doi:10.1108/PR-09-2017-0273

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Addison-Wesley.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. doi:10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

- Hsu, M.-H., Ju, T. L., Yen, C.-H., & Chang, C.-M. (2007). Knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities: The relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 65(2), 153–169. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.09.003

- Huan, H., Yongyuan, M., Sheng, Z., & Qinchao, D. (2017). Characteristics of knowledge, people engaged in knowledge transfer and knowledge stickiness: Evidence from Chinese R&D team. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(6), 1559–1579.

- Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in organizations: A conceptual framework. Human Resource Development Review, 2(4), 337–359. doi:10.1177/1534484303257985

- Javed, B., Khan, A. A., Bashir, S., & Arjoon, S. (2017). Impact of ethical leadership on creativity: The role of psychological empowerment. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(8), 839–851. doi:10.1080/13683500.2016.1188894

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. C. (2012). How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1264–1294. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0088

- Kankanhalli, A., Tan, B. C., & Wei, K.-K. (2005). Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 113–143. doi:10.2307/25148670

- Katsikea, E., Theodosiou, M., Perdikis, N., & Kehagias, J. (2011). The effects of organizational structure and job characteristics on export sales managers’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Journal of World Business, 46(2), 221–233. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2010.11.003

- Kazlauskaite, R., Buciuniene, I., & Turauskas, L. (2011). Organisational and psychological empowerment in the HRM‐performance linkage. Employee Relations, 34(2), 138–158. doi:10.1108/01425451211191869

- Khan, Z. A., Thornton, N., & Frazer, M. (2000). Experience of a financial reforms project in Bangladesh. Public Administration and Development, 20(1), 33–42. doi:10.1002/1099-162X(200002)20:1<33::AID-PAD100>3.0.CO;2-T

- Kirkman, B. L., & Rosen, B. (1997). A model of work team empowerment. In R. W. Woodman & W. A. Pasmore (Eds.), Research in organizational change and development. (Vol. 10, pp. 131–167). JAI Press.

- Kirkman, B. L., & Rosen, B. (1999). Beyond self-management: Antecedents and consequences of team empowerment. Academy of Management Journal, 42(1), 58–74. doi:10.2307/256874

- Kremer, H., Villamor, I., & Aguinis, H. (2019). Innovation leadership: Best-practice recommendations for promoting employee creativity, voice, and knowledge sharing. Business Horizons, 62(1), 65–74. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.010

- Kwak, Y. H. (2002). Critical success factors in international development project management. 10th International symposium construction innovation & global competitiveness.

- Law, C. C., & Ngai, E. W. (2008). An empirical study of the effects of knowledge sharing and learning behaviors on firm performance. Expert Systems with Applications, 34(4), 2342–2349.

- Lin, H.-F. (2007). Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on employee knowledge sharing intentions. Journal of Information Science, 33(2), 135–149. doi:10.1177/0165551506068174

- Locke, E., & Schweiger, D. (1979). Participation in decision-making: One more look. In B. M. Staw (Ed.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 265–340). JAI Press.

- Logan, M. S., & Ganster, D. C. (2007). The effects of empowerment on attitudes and performance: The role of social support and empowerment beliefs. Journal of Management Studies, 070605080020001–070605080021550. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00711.x

- Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. Drenth, H. Thierry & C. J. d. Wolff. (Eds.), Handbook of work and organisatonal psychology. (2nd ed., pp. 5–33). Erlbaum.

- Morgan Tuuli, M., Rowlinson, S., Fellows, R., & Liu, A. M. (2012). Empowering the project team: impact of leadership style and team context. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 18(3/4), 149–175. doi:10.1108/13527591211241006

- Morris, P. W. (1994). The management of projects. Thomas Telford.

- Müller, J., & Stocker, A. (2011). Enterprise microblogging for advanced knowledge sharing: The references@BT case study. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 17(4), 532–547.

- Nordqvist, S., Hovmark, S., & Zika-Viktorsson, A. (2004). Perceived time pressure and social processes in project teams. International Journal of Project Management, 22(6), 463–468.

- Patterson, M. G., West, M. A., & Wall, T. D. (2004). Integrated manufacturing, empowerment, and company performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(5), 641–665. doi:10.1002/job.261

- Petter, J., Byrnes, P., Choi, D.-L., Fegan, F., & Miller, R. (2002). Dimensions and patterns in employee empowerment: Assessing what matters to street-level bureaucrats. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 12(3), 377–400. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003539

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. doi:10.3758/BF03206553

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. doi:10.1080/00273170701341316

- Psoinos, A., Kern, T., & Smithson, S. (2000). An exploratory study of information systems in support of employee empowerment. Journal of Information Technology, 15(3), 211–230. doi:10.1177/026839620001500304

- Rafique, M., Hameed, S., & Agha, M. H. (2018). Impact of knowledge sharing, learning adaptability and organizational commitment on absorptive capacity in pharmaceutical firms based in Pakistan. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(1), 44–56. doi:10.1108/JKM-04-2017-0132

- Robey, D., Smith, L. A., & Vijayasarathy, L. R. (1993). Perceptions of conflict and success in information systems development projects. Journal of Management Information Systems, 10(1), 123–140. doi:10.1080/07421222.1993.11517993

- Rowlinson, S., & Cheung, Y. K. F. (2008). Stakeholder management through empowerment: Modelling project success. Construction Management and Economics, 26(6), 611–623. doi:10.1080/01446190802071182

- Seibert, S. E., Wang, G., & Courtright, S. H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 981–1003. doi:10.1037/a0022676

- Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J., & Oldham, G. R. (2004). The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? Journal of Management, 30(6), 933–958.

- Singh, J. B., Chandwani, R., & Kumar, M. (2018). Factors affecting Web 2.0 adoption: Exploring the knowledge sharing and knowledge seeking aspects in health care professionals. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(1), 21–43.

- Sok, P., Sok, K. M., Danaher, T. S., & Danaher, P. J. (2018). The complementarity of frontline service employee creativity and attention to detail in service delivery. Journal of Service Research, 21(3), 365–378. doi:10.1177/1094670517746778

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. doi:10.5465/256865

- Spreitzer, G. M., & Doneson, D. (2005). Musings on the past and future of employee empowerment. In T. G. Cummings (Ed.), Handbook of organizational development (pp. 5–10). Sage.

- Srivastava, A., Bartol, K. M., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1239–1251. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.23478718

- Stasser, G., & Titus, W. (1985). Pooling of unshared information in group decision making: Biased information sampling during discussion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(6), 1467–1478. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.6.1467

- Thomas, K. W., & Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. The Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 666–681. doi:10.2307/258687

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1–9. doi:10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841

- Tomaka, J., Blascovich, J., Kibler, J., & Ernst, J. M. (1997). Cognitive and physiological antecedents of threat and challenge appraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 63–72. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.63

- Turner, J. R., & Keegan, A. (1999). The versatile project-based organization: governance and operational control. European Management Journal, 17(3), 296–309. doi:10.1016/S0263-2373(99)00009-2

- Ul Haq, M. A., Usman, M., & Khalid, S. (2018). Employee empowerment, trust, and innovative behavior: Testing a path model. Journal on Innovation and Sustainability. RISUS ISSN 2179-3565, 9(2), 3–11. doi:10.24212/2179-3565.2018v9i2p3-11

- Valentine, S. R., Hollingworth, D., & Schultz, P. (2018). Data-based ethical decision making, lateral relations, and organizational commitment: Building positive workplace connections through ethical operations. Employee Relations, 40(6), 946–963. doi:10.1108/ER-10-2017-0240

- Vroom, V. H., & Yetton, P. W. (1973). Leadership and decision-making. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Wallace, J. C., Johnson, P. D., Mathe, K., & Paul, J. (2011). Structural and psychological empowerment climates, performance, and the moderating role of shared felt accountability: A managerial perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 840–850. doi:10.1037/a0022227

- Wang, Y., & Haggerty, N. (2009). Knowledge transfer in virtual settings: The role of individual virtual competency. Information Systems Journal, 19(6), 571–593. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2575.2008.00318.x

- Wang, W.-T., Wang, Y.-S., & Chang, W.-T. (2019). Investigating the effects of psychological empowerment and interpersonal conflicts on employees’ knowledge sharing intentions. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(6), 1039–1076. doi:10.1108/JKM-07-2018-0423

- Williams, L. J., Cote, J. A., & Buckley, M. R. (1989). Lack of method variance in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: reality or artifact? Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(3), 462–468. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.74.3.462

- Wu, C.-S., Lee, C.-J., & Tsai, L.-F. (2012). Influence of creativity and knowledge sharing on performance. Journal of Technology Management in China, 7(1), 64–77. doi:10.1108/17468771211207358

- Xue, Y., Bradley, J., & Liang, H. (2011). Team climate, empowering leadership, and knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(2), 299–312. doi:10.1108/13673271111119709

- Zhou, J., & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 682–696. doi:10.2307/3069410

- Zhou, J., & Shalley, C. E. (2003). Research on employee creativity: A critical review and directions for future research. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 22, 165–217. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(03)22004-1