?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Current theories cannot explain the coexistence of China’s 40 years of rapid economic growth and its imperfect financial system, insufficient investor protection, and government intervention. This study empirically tests hypotheses regarding the effects of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans using econometric models based on survey data of 2,848 enterprises in China collected by the World Bank. The results show an inverted U-shaped relationship between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans: a low level of corruption increases firms’ access to bank loans, whereas a high level of corruption hinders firms from obtaining bank loans. Mild corruption may be a suboptimal choice for firms seeking bank loans, and bank funds allocation based on corruption can achieve Pareto optimality among firms. Moreover, government guarantees are conducive to firms’ access to financing and the link between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans can be explained by the role of government guarantees. The improvement of institutional quality is positively associated with firms’ access to bank loans and weakens the effects of corruption on firms’ external financing. This study thus sheds light on the real effects of corruption and the determinants of firms’ access to bank loans in developing countries.

1. Introduction

There is no doubt that the effective allocation of bank loans is not only a necessary condition for alleviating financial constraints of firms but also an important factor for promoting economic growth. Firms need sufficient funds to carry out innovation and investment, seize business opportunities and alleviate the development restrictions caused by financing constraints. Therefore, how to ensure the Pareto optimisation of bank loan allocation among firms has become a main task for entrepreneurs to achieve commercial success and for developing countries to maintain sustained economic growth. Developed financial markets and financial intermediaries are essential for economic growth (Rajan & Zinagales, Citation1998), as a well-functioning financial market plays a vital role in the evaluation of investment projects, allocation of capital resources and supervision of managers (Hsu et al., Citation2014). Financial intermediaries promote investment productivity by providing funds to the best quality enterprises (Greenwood & Jovanovic, Citation1990). Moreover, fairness of the rule of law, protection of private property and effective corporate governance are important factors explaining enterprise value and economic growth (La Porta et al., Citation2000).

China’s economy has maintained rapid growth over the past 40 years that has been referred to as growth miracle. However, China’s economic growth challenges mainstream academic views. According to institutional economics theory, China’s economic success should not have occurred, because it has an imperfect legal system, inadequate investor protection, and excessive government intervention. At the same time, although China’s institutional construction is lagging behind, its credit has maintained stable and rapid growth over the past 30 years. Private enterprises have higher productivity than state-owned enterprises (SOEs), but they have fewer external financing channels than SOEs (Song et al., Citation2011). This phenomenon of sustained economic growth in a backward institutional environment is often referred to as the East Asia paradox. Scholars provide various explanations for this paradox, with political promotion campaigns and fiscal decentralisation being the two main explanations (Allen et al., Citation2005; Lin et al., Citation2015).

Although previous research on corruption is extensive, there are few studies on the impact of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans. Moreover, this study differs from prior research in that it argues that the current institutional environment hides an alternative institutional arrangement that replaces formal institutions in bank credit allocation tasks. This alternative institutional arrangement is an informal rule based on corrupt acts, such as bribery. As in an auction mechanism, firms’ financing activities based on bribery can achieve Pareto-suboptimal allocation. Corruption provides an effective incentive for public officials to introduce an alternative institutional arrangement into the economy, which alleviates the inhibition of credit resource allocation caused by the backwardness of formal institutions. With the establishment and improvement of formal institutions, the market replaces the credit allocation function of corruption, and corruption activities are accordingly reduced.

This paper uses the World Bank survey data for enterprises’ business environments to investigate the effects of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans. In addition, we analyze the role of government guarantees and institutional quality in corruption affecting firm financing. This study estimates econometric models to examine the hypotheses using a sample of 2,848 enterprises, including 148 SOEs and 2,700 non-SOEs, from the World Bank’s 2012 survey on China’s enterprises, which provides a better understanding of the effects of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans and influencing factors of firm financing in developing countries.

The results show that the relationship between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans is inverted U-shaped, which is different from views of corruption as a stepping stone or stumbling block for firms to obtain bank credit. Specifically, low-level corruption is beneficial for firms to obtain bank loans, whereas high-level corruption hinders firms from obtaining bank loans. Corruption is neither absolutely beneficial nor absolutely harmful in developing countries that have not yet fully established a perfect market system, and the effects of corruption are influenced by the quality of formal institutions. In addition, corrupt acts benefit firms in obtaining government guarantees, which are conducive to these firms obtaining bank loans. This paper provides empirical evidence for the inverted U-shaped relationship between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans and provides favourable evidence that can settle disputes over previous research conclusions.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses how the study relates to the literature and proposes testable hypotheses. Section 3 describes the methodology and data. Section 4 presents and discusses the test results. Section 5 presents conclusions, states the limitations of this article and offers suggestions for future study.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

2.1. Corruption as a stepping stone for firms’ access to bank loans

Financial institutions provide funds within a rigid and binding system, which leads to the exclusion of firms that do not meet the conditions for financial institutions to issue loans. Therefore, maintaining a good relationship with banks has become a strategic behaviour for enterprises to obtain bank loans. Gift exchange generates important social capital, enabling enterprises to maintain relations with officials (Cai et al., Citation2011).The lubricant hypothesis suggests that corruption weakens the rigidity of the system, which can make corrupt acts beneficial to economic development (Dreher & Gassebner, Citation2013; Huntington, Citation1979). Specifically, corruption can soften the rigid system of loans, simplify cumbersome loan procedures, reduce the loan approval waiting time and improve investment efficiency (Levine et al., Citation2000; Lui, Citation1985). We regard bribery and other corrupt acts as the second best choice to improve firms’ bank loan approval efficiency.

Financing under corrupt acts is like a bargaining process. Firms can obtain funds through auctions, as financial institutions sell funds to the highest bidder. According to bidding model theory (Beck & Maher, Citation1986; Lien, Citation1986), the credit allocation efficiency of financial institutions remains unchanged in this case, and thus the lowest-cost enterprises can pay the largest bribes. Therefore, credit allocation mechanisms based on corrupt acts enable the lowest-cost enterprises to obtain formal financing opportunities from financial institutions. Although corruption generally prevents banks from lending money to enterprises, it alleviates enterprises’ financing obstacles (Weill, Citation2011).

Information asymmetry increases the red tape of financial institutions, which reduces credit allocation efficiency and increases transaction costs. Financial institutions’ low cost of collecting business information is conducive to alleviate information asymmetry; thus, they can make more effective decisions, and firms connected with banks obtain bank loans more easily. The bribery of officials by firms reduces the adverse effects of red tape and helps these firms obtain bank loans, although this results in an increase in the short-term bank debt ratio (Chen et al., Citation2013; Fungacova et al., Citation2015). Therefore, corruption acts promote the relationship between banks and firms and are effective strategic behaviours for firms to obtain bank loans. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Corruption has a positive effect on firms’ access to bank loans.

2.2. Corruption as a stumbling block for firms’ access to bank loans

The rent-seeking view of Public choice theory holds that corruption is not conducive to development (Krueger, Citation1974). Because of information asymmetry in the credit rationing process, bank officers usually have decision rights on credit terms, such as loan interest rates, loan maturities, and collateral types (Barth et al., Citation2009). Therefore, the rights of bank officers may lead firms to bribe them. Bribery gives corrupt officials greater motivation to formulate more complicated loan terms, which leads firms to increase their bribes to avoid these new terms (Guriev, Citation2004). Moreover, a high level of corruption leads to opportunistic behaviours in inefficient systems, which increases the non-performing loans generated by bank institutions due to loan defaults. Corruption acts not only increase the uncertainty of banks’ avoidance of default but also increase the risk of borrowers’ default, which reduces banks’ willingness to lend to firms and increases the obstacles of firm financing (Qi & Ongena, Citation2019; Qian & Strahan, Citation2007; Wellalage et al., Citation2019).

The information asymmetry between banks and borrowers results in two effects: adverse selection and reverse incentive (Stiglitz & Weiss, Citation1981). The adverse selection effect refers to the fact that the rise of bank interest rate prevents low-risk borrowers from entering the financial market. Adverse selection theory argues that low-quality enterprises with poor financing ability are more motivated than high-quality enterprises to bribe officials to obtain bank loans. Therefore, to avoid adverse selection and moral hazard, a typical practice of financial institutions is to formulate more stringent firm loan terms; however, doing so increases borrowing costs and causes firms to face more legal restrictions and financing constraints (Ayyagari et al., Citation2008; Beck et al., Citation2006; Firth et al., Citation2009). The reverse incentive effect refers to the fact that the higher the bank loan interest rate is, the greater the motivation of potential borrowers to invest in higher-risk projects. According to reverse incentive theory, the transaction cost of bank loans obtained through bribery is relatively high, which encourages firms to invest in high-risk projects and increases the risk of bank loan recovery.

Because of adverse selection and reverse incentive, firms increase their bribery, which results in the rise of banks’ non-performing loans and the reduction of capital supply by banks. Commercial bribery leads to inefficient rules, which increase the cost for firms to obtain funds (Ahlin & Bose, Citation2007). Fortunately, timely confirmation of loan losses can curb lending corruption and increase the likelihood of problematic loans being discovered (Akins et al., Citation2017). In view of the above issues, the second hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Corruption has a negative effect on firms’ access to bank loans.

2.3. The role of government guarantees in firms’ access to bank loans

The government has a great impact on banks’ lending decisions in government-led economies and extends a helping hand to alleviate financial institutions’ concerns regarding corporate moral hazards (Faccio et al., Citation2006; La Porta et al., Citation2002). Government guarantees influence firms’ access to bank loans in two ways. First, government guarantees are important reputation assets and financing resources for firms. Banking institutions’ behaviours are usually based on national policy considerations in developing countries, so firms with government guarantees can share governments’ network resources to receive more support from banks, such as low-cost loans. After the Chinese government implemented the economic stimulus plan, the responses of SOEs and non-SOEs with political ties to investment opportunities worsened, and SOEs obtained more resources than non-SOEs (Liu et al., Citation2018).

Second, because of implicit government guarantees, even if firms with state ownership have poor management and performance, they have higher political status and are generally considered safer than non-SOEs. State ownership can provide an implicit guarantee for firms’ debt; therefore, firms with state ownership have a lower probability of bankruptcy than non-SOEs (Borisova et al., Citation2015). Private enterprises that receive more government assistance are more likely to receive bank loans (Ruan et al., Citation2018). Hence, firms try to find effective ways to obtain funds from financial institutions and alleviate financing constraints, such as obtaining government guarantees and bribing officials. However, government intervention in capital allocation distorts the allocative function of the financial market and worsens the financing environment of the private sector (Guariglia & Poncet, Citation2008). The third hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Government guarantees facilitate firms’ access to bank loans.

3. Methodology and data

3.1. Empirical methodology

To investigate corruption and other factors that affect firms’ access to bank loans, this study estimates various forms of the model below:

(1)

(1)

where i indexes the firm and Lendi represents the credit or loan status of firm i, which is defined as whether the firm has a line of credit or a loan from financial institutions. Briberyi refers to the corrupt behaviour between firms and public officials; that is, the level of corruption. Model (1) includes a quadratic term of corruption that can measure not only the average effect of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans but also the possible non-linear relation between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans. Zi denotes a control variable vector that includes the firm-level characteristics and the characteristics of the city where the firm is located. Model (1) also includes industry fixed effects and city fixed effects. μk is industry fixed effects that absorb the effects of industrial variation. ωj is city fixed effects, and is used to tackle the problem of unobservable variables omitted from regional characteristics. For example, faster economic growth in certain areas is unobservable and correlates with both corruption and firm financing. εi is the error term.

Previous studies employed multiple evaluation indexes to measure the level of corruption, such as the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), Bribe Payers Index (BPI), Administrative Corruption Index (ACI), and State Capture Index (SCI). Some studies also used the proportion of corruption involving malfeasance to the number of local public officials to measure the degree of corruption. These indexes are influenced by cultural and psychological factors, and corruption is a hidden and non-public behaviour. These indexes therefore cannot accurately reflect the true degree of corruption. The World Bank uses the Graft Index to measure the direct costs of corruption. This index measures the degree of corruption by measuring the informal payments or gifts made by firms to public officials for the successful development of relevant production and business activities. Firms’ informal payments include gifts, meals, cash and other items to seek benefits for firms or individuals. Many scholars have considered informal payment as a form of corruption that only includes the relationship of material interests and characterised by direct and immediate payment (Şeker & Yang, Citation2014; Wu, Citation2019; Yang, Citation1989). This study uses the percentage of total informal payments in the firm’s annual sales to measure the level of corruption in business. reports the definitions of the dependent and independent variables.

Table 1. Variable definitions.

3.2. Data

The paper uses data from the People’s Republic of China 2012 Enterprise Surveys Data Set by the World Bank, which reflects the information of enterprises in fiscal year 2010. The survey uses the stratified random sampling method according to enterprises’ domain name; thus, the sample enterprises in this survey are highly representative. The survey data are provided by the general managers, accountants, human resources managers and other enterprise employees. Specifically, this survey was conducted in 25 cities in China and covered 26 industries, investigating 2,848 Chinese enterprises, including 148 SOEs and 2,700 non-SOEs. After deleting invalid items, the valid sample in this paper is 1,440 enterprises. This includes 71 SOEs, accounting for 4.93% of the valid sample, and 1,369 non-SOEs, accounting for 95.07% of the valid sample. presents the summary statistics of the variables used in this article.

Table 2. Summary statistics.

4. Empirical results and analysis

4.1. Corruption and firms’ access to bank loans

Because of reverse causality and omitted variables, a major challenge of this study is the identification of the causal impacts of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans. Firm financing is likely endogenous with respect to firm characteristics and market characteristics, including the business environment. To control the endogeneity problem and contemporaneous reverse causality, this paper uses an instrumental variable to estimate the main model.

The World Bank’s survey of the business environment provides many instrumental variables, including a dummy variable (Electric). If a firm has submitted an application to obtain an electrical connection over the past two years, the value of Electric is 1; otherwise, the value of Electric is 0. We believe that the firm’s application to the authorities is a prerequisite for solving the power problem, and the firm can operate normally after the problem is solved. The electricity sector is a natural monopoly that lacks effective supervision mechanisms, and public officials have the authority to grant enterprises access to the national power grid. Monopoly is a major cause of corporate bribery and corruption involving public officials (Yang, Citation2005). Hence, firms’ applications for electricity are associated increased rent-seeking behaviours by officials because applying to government authorities to use the electricity infrastructure means that firms have to interact with public officials. In addition, there is no evidence of a direct correlation between firms submitting applications to obtain electrical connections and firms obtaining bank loans. Therefore, this variable, Electric, is a good instrumental variable.

reports the results of corruption’s effects on firms’ access to bank loans by Probit, Tobit, and Instrumental Variable (I.V.) regression. In columns (1), (2), (5), and (6) of , the coefficients of corruption, Bribery, are significantly positive at the 1% level, which indicates that corruption has significant promoting effects on firms’ access to bank loans. Columns (3), (4), (7), and (8) of include the squared terms (Briberysq) for the corruption variable in the estimations to consider the possible nonlinear relation between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans. Specifically, the linear terms of corruption are significantly positive at the 1% level, and the squared terms of corruption are significantly negative at the 1% level, which indicates that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans. The results in show that the thresholds of corruption are 13.3090 (column 3), 13.8333 (column 4), 11.5613 (column 7), and 11.7917 (column 8). Therefore, before the levels of corruption reaches the thresholds, the increase in corruption promotes firms’ access to financing from banks. After the levels of corruption crosses the inflection points, the increase in corruption hinders firms from obtaining financing from banks. In columns (5) to (8) of , the results of the Wald test reject the null hypothesis in the Instrumental Variable regressions, which suggest that corruption is endogenous. The robustness tests of weak instrumental variables (AR) reject the null hypothesis, which indicates that there is no problem of weak instrumental variables. The results of FAR (P) accept the null hypothesis, which suggests that the instrumental variable satisfies the exclusion of limitation (Berkowitz et al., Citation2012).

Table 3. The estimation results of corruption’s effects on firms’ access to bank loans.

These findings are consistent with the conclusions of Faccio (Citation2010) and Li et al. (Citation2008), who argue that corrupt acts help firms overcome market failures and eliminate ideological discrimination to obtain bank loans and reduce borrowing costs. Toader et al. (Citation2018) and Ali et al. (Citation2019) find that a lower level of corruption results in higher credit allocation efficiency and moderate credit growth. In addition, banks’ preferences have greater effects on small enterprises, which are excluded from the formal financial system and face more financing constraints than large enterprises (Adegboye & Iweriebor, Citation2018; Gonzalez, Citation2015). As a result, these firms have sufficient incentives to gain the favour of officials via bribes to evade the investigation of their credit status and to obtain bank credit. Banks’ investment in relationship lending is particularly important for small enterprises’ access to bank finance (Fungáčová et al., Citation2017). Many small firms are forced to engage in bribery to obtain financial resources, whereas large firms are systematically involved in bribery (Zhou & Peng, Citation2012). According to the above viewpoints, corruption can be regarded as a lubricant for firms to obtain bank loans and can reduce the rigidity of the bank loan institution.

Corruption is not absolutely beneficial, as a higher degree of corruption distorts the allocation of bank credit resources and increases firms’ operating costs. Because corrupt bank officials may weigh the best amount of bribery according to the credit status of enterprises, more bribery does not necessarily entail more credit opportunities for these enterprises. Corruption is a cost for a firm seeking financing protection from officials. A higher level of corruption may be due to officials’ failure to fulfil their previous promises made in exchange for bribes, and these officials may demand more bribes from firms. In addition, due to information asymmetry, banks have difficulty in identifying firms’ quality, which leads to banks raising loan rates and requiring borrowers to provide more collateral. In such cases, high-risk firms are more motivated than low-risk firms to offer larger bribes to compete for bank loans, which results in adverse selection and moral hazard problems and an increase in non-performing loans. The rise in non-performing loan ratio increases bank risks, which leads to the deterioration of loan quality and the instability of the financial system (Zhang et al., Citation2016). Our result is consistent with the view that corruption has a negative impact on firm financing and the allocation efficiency of bank loans (Beck et al., Citation2006; Wellalage et al., Citation2019). A possible explanation is that China lacks a sound financial system and legal system, and that government intervention reduces the efficiency of resource allocation in the financial market. However, some studies argue that bribery has nothing to do with firms’ bank financing channel and bank financing scale (Ruan et al., Citation2018; Tian et al., Citation2017).

The results of the control variables are in line with expectations. In , the coefficients of firm size (Scale) are significantly positive at the 1% level, which suggests that large enterprises have more collateral and easier access to bank loans than small enterprises. The coefficients of firm age (Age) suggest that there is no causal relationship between firm age and firms’ access to bank loans. Although banks can obtain more information from old enterprises, such information may not be conducive to these enterprises obtaining bank loans. The coefficients of state-owned share (State) are significantly negative at the 1% level, which indicates that an increase in the proportion of state-owned shares reduces the probability of enterprises obtaining bank loans. Because firms with state ownership can obtain more government shelters, soft budget constraints, and policy subsidies than non-SOEs, they have more financing channels and lower dependence on bank loans. The coefficients on the average annual growth rate of firm sales (Growth) are significantly positive, which is consistent with the previous findings (Chen et al., Citation2013; Faccio, Citation2010). The faster the sales growth of enterprises, the stronger their ability to repay debts, which implies a lower expected default risk for these enterprises.

The coefficients of firm operating margin (Profit) are negative, but most are not significant. The result is consistent with that of Rajan and Zingales (Citation1995), who argue that firm profitability has a negative impact on the debt level, although it is not significant in some regions and countries. The coefficients of firm quality (Quality) and firm financial information transparency (Audit) are significantly positive, which reveal that the more firms are recognised by external third organisations, the easier it is for them to obtain bank loans. The coefficients of city scale (City size) are significantly positive, which suggests that enterprises in large cities can obtain more bank loans. The coefficients of city business level (Business) are significantly negative. The information hypothesis argues that market competition is negatively associated with firms’ access to credit, because competition lowers the incentives of banks to invest in soft information and relationship lending (Owen & Pereira, Citation2018). Therefore, the more prosperous business is in the city where the enterprise is located, the smaller the share of the enterprises that successfully obtain bank loans. This finding is in line with the argument that competitive bank markets reduce relationship lending and increase financial constraints (Berger & Udell, Citation2002; Berger & Black, Citation2011).

4.2. The role of government guarantees in corruption affecting firms’ access to bank loans

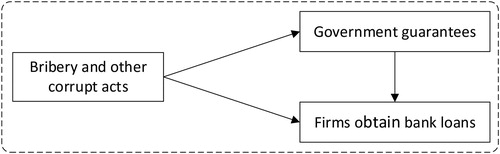

This subsection investigates the role of government guarantees in corruption affecting firms’ access to bank loans. In China, early bank loans were mainly in the form of credit. The interest rates for such loans are low, and borrowers are not required to provide guarantees or collaterals, which leads to an increase in the bank’s non-performing loans. With the gradual development of financial institutions’ credit risk awareness, Chinese banks increasingly require borrowers to provide guarantees and collaterals, especially when providing loans to private firms (Yeung, Citation2009). Therefore, many firms are unable to provide qualified guarantees and collaterals, and they are often excluded from the formal financial system. In addition, state-owned banks and the government have a discriminatory tendency in the loan-granting process, as they tend to provide preferential loans to SOEs rather than to private firms (Cull & Xu, Citation2003; Lin et al., Citation2015). To obtain government guarantees and bank loans, these firms may engage in bribery or take part in other corrupt activities to establish political relations with public officials. Hence, obtaining government guarantees has become an important channel for firms to obtain bank loans and low-cost funds, as shown in .

We regard government guarantees as a credit mechanism that transmits soft information to financial institutions and helps enterprises obtain external financing. This study employs structural equation modelling path analysis techniques to evaluate the logical framework in . We measure government guarantees (Guarantee) by whether enterprises have government contracts (if a firm has secured or attempted to secure a government contract over the last year, the value of Guarantee is 1; otherwise, the value of Guarantee is 0). The results are shown in . The goodness of fit of the structural equation model is 0.6917, and the stability index is close to 0. These results indicate that the structural equation model meets the stability criteria.

Table 4. The structural path coefficients of corruption.

The coefficient of a single path shows that corruption helps enterprises obtain government guarantees (β = 0.0126, p < 0.05). Bribery and other corrupt acts have special effects on resource allocation and enable enterprises to obtain government guarantees, which help enterprises obtain bank loans (β = 0.1308, p < 0.01). Imperfect financial market systems and harsh listing conditions make it difficult for firms to obtain external financing in China’s financial market, while firms with government guarantees have easier access to bank loans and face less risk of default. The government can alleviate the problem of financial institutions refusing to provide funds to high-risk firms and excluding vulnerable borrowers by introducing state-guaranteed funds (Ben-Yashar et al., Citation2018; Wilcox & Yasuda, Citation2019). Thus, to get around the financing constraints, firms may obtain government guarantees and bank loans by bribing officials.

presents the indirect effects and total effects of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans. The path coefficient shows that the indirect effect coefficient of government guarantees via bribery on bank loans is 0.0016, which is significant at the 5% level. This implies that obtaining government guarantees via corrupt acts is an effective channel for firms to obtain bank loans. The government controls the supply of vital resources, and banks are thus influenced by the government when providing funds (Sapienza, Citation2004).

Table 5. The indirect effects and total effects of corruption.

In , the total effect coefficients indicate that firms use corrupt behaviour strategically to obtain government guarantees and bank loans. Entrepreneurs can influence government policies or obtain government support through bribing officials (Djankov et al., Citation2008; Harstad & Svensson, Citation2011). Moreover, bribery can entice public officials to ignore firms’ violations and help firms obtain contracts (Wu, Citation2018). Therefore, bribery and other corrupt acts could be means of establishing political connections with officials, which are key ways for firms to obtain market resources and government guarantees.

4.3. The estimation of generalized propensity score matching

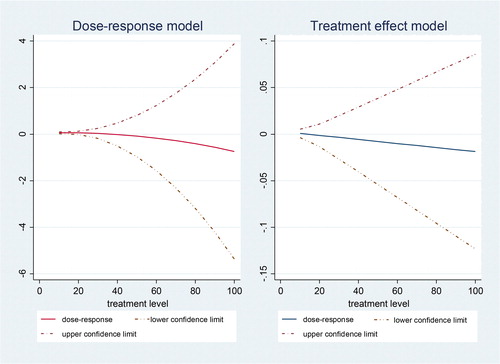

This subsection uses the Generalized Propensity Score Matching (GPSM) method to check whether the influence of corruption on firms’ bank loan intensity varies across different levels of corruption. The GPSM of the processing variable (Bribery) is calculated, and firms’ bank loan intensity (defined as the percentage of loans obtained by a firm from banks in its annual sales revenue) is taken as the dependent variable. The degree of corruption (Bribery) is taken as the key explanatory variable, and the generalized tendency score (Pscore) of the processing variable is taken as a control variable. We then conduct the estimations using the OLS method. presents the estimated results, which show that the coefficients of corruption (Bribery), the squared term of corruption (Briberysq), and the interaction term (Bribery × Pscore) are all significant. We use these estimation results as the basis for the next step.

Table 6. The estimated results of OLS regression.

illustrates the trends of firms’ bank loan intensity at different corruption levels. The trend of the dose-response function estimation indicates that the relationship between corruption and firms’ bank loan intensity is inverted U-shaped. As the corruption level rises from low to high, the positive impact of corruption acts on firms’ bank loan intensity gradually weakens. When the degree of corruption exceeds 0.18, corruption acts have a restraining effect on firms’ bank loan intensity, and this negative effect gradually increases.

We divide the sample into several groups according to the range of the corruption degree and then check the differences in the effects of different degrees of corruption on firms’ bank loan intensity. The estimation results in suggest that when the degree of corruption is less than or equal to 0.02, corruption promotes firms’ access to bank loans. When the degree of corruption is higher than 0.02, corruption hinders enterprises from obtaining bank loans, and this inhibitory effect increases with the increase of corruption degree. These results imply that mild corruption is beneficial for enterprises seeking bank loans, although severe corruption hinders firms’ access to bank funds and development.

Table 7. The effects of corruption on firms’ bank loan intensity.

4.4. Robustness test

This subsection checks the robustness of the main findings using several approaches. The estimation results are reported in . First, we conduct a sensitivity analysis with a substitute variable of corruption. Wang and You (Citation2012) measure corruption by the days when a firm deals with the government. The length of time that firms deal with the government is related not only to corruption but perhaps also to the administrative efficiency. If the influence of administrative efficiency cannot be eliminated, this method may result in incorrect regression results. Therefore, we use the percentage of total senior management time spent dealing with the requirements imposed by government regulations as a substitute variable (Corruption) to measure corruption. The regression results are shown in columns (1) to (4) of . The coefficients of the linear terms (Corruption) of corruption are significantly positive, and the squared terms (Corruptionsq) for corruption variable are significantly negative, which indicates an obvious inverted U-shaped relationship between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans. These results align with the main estimations and confirm the robustness of our results.

Table 8. Results of robustness test.

Second, this study explores the role of institutional quality in corruption affecting firms’ access to bank loans. This study measures institutional quality using enterprises’ evaluation of the court system (Item: ‘The court system is fair, impartial and uncorrupted.’ Answers and variable assignments: strongly disagree = 1, tend to disagree = 2, tend to agree = 3, strongly agree = 4). We include the variable of institutional quality (Law) and the interaction term between institutional quality and corruption (Law_Corruption) as control variables in the regression model. The results are shown in columns (1) to (4) of . The regression results show that when controlling the institutional quality faced by firms, the relationship between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans is still inverted U-shaped. The coefficients of Law are significantly positive at the 1% level, which indicates that increased institutional quality promotes firms’ access to bank loans. The coefficients of Law_Corruption reveal that the improvement of institutional quality weakens the impact of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans, and the effects of corruption are replaced by the resource allocation function of market mechanisms.

Similarly, Wang and You (Citation2012) find a substitution relationship between corruption acts and financial markets on firm growth. Because of the inherent institutional weakness in transition economies, corruption has a potential positive impact on the new product innovation by enterprises (Xie et al., Citation2019). A possible interpretation is that high-quality formal institutions stimulate the market to allocate resources efficiently, which reduces the discretionary space for public officials and the scale of rent-seeking. Higher quality of institutions weakens the adverse effects of collectivism on bank corruption (El Ghoul et al., Citation2016). However, firms have a higher probability of bribery to compete for better resources when they face poor institutional environments and extraneous administrative procedures, such as opaque legal interpretations, inefficient administrative services, and corrupt court systems (Huang & Rice, Citation2012; Wu, Citation2009; Zhou et al., Citation2013).

Finally, this study divides the enterprises into two subsamples according to industry categories (i.e., the manufacturing industry and the retail and service industry) and conducts separate analyses. The regression results are reported in columns (5) and (6) of . The linear terms of corruption (Bribery) are significantly positive, and the squared terms (Briberysq) are significantly negative. These results reveal a nonlinear relationship between corrupt acts and firm financing: initially, the corruption level increases and firm financing increases, but corruption hinders enterprises from obtaining external financing after the corruption level reaches the inflection point. These results indicate that the relationship between corruption and firms’ access to bank loans is inverted U-shaped in both the manufacturing industry (column 5) and the retail and service industry (column 6), which confirms the robustness of the main results.

5. Conclusions and policy implications

This study investigates the effects of corruption on firms’ access to bank loans. The data are obtained from a 2012 survey of Chinese enterprises’ business environment by the World Bank. The estimation results reveal an inverted U-shaped relationship between corrupt acts and firms’ access to bank loans. A low degree of corruption can help firms obtain bank loans, but a high degree of corruption hinders firms from obtaining bank loans. In addition, corruption affects firms’ access to external financing by enabling them to obtain government guarantees which are positively associated with firm financing. Institutional quality has a positive relation with the allocation of bank credit, and the impact of corruption on firm external financing weakens in regions where institutional quality is high, which suggests that institutional quality enhances the resource allocation function of market mechanisms. These results show that corruption is an alternative for the lack of formal institutions and is an important way for firms to obtain bank loans. Financial resources allocation can realise Pareto sub-optimality among firms depending on the amount of bribery. Fortunately, with the establishment and improvement of formal institutions, corrupt activities will gradually decrease. These findings are significant for the reform of banking systems, the construction of clean governments and the allocation of financial resources in developing countries.

First, a sound financial system should be built to ensure that firms have fair opportunities to enter financial markets. A perfect market plays an important role in promoting the efficiency of resource allocation and is the basis upon which firms obtain external funds through a formal financial system. However, in many developing countries, credit allocation is still dominated by the government, which has great discretion in formulating resource allocation policies. Excessive government intervention in resource allocation is an important reason for financial market failure. State ownership of the media is related to a higher degree of corruption in bank lending (Houston et al., Citation2011). Fortunately, information sharing and bank competition reduce lending corruption, and information sharing helps enhance the positive role of competition in curbing lending corruption (Barth et al., Citation2009). The negative impact of collectivism on corruption in bank lending is less serious in countries where the proportion of state-owned banks is low (El Ghoul et al., Citation2016; Zheng et al., Citation2013). Therefore, developing countries need to optimise the operational mechanism of the financial market and accelerate the transformation of financial resources allocation from government-led to market-led.

Second, anti-corruption efforts should be strengthened and a clean government should be established. The function of the government is to construct a market-based resource allocation mechanism to address the adverse effect of market failure on enterprises’ external financing. However, corruption is a kind of rent-seeking behaviour that originates from the power of public officials. The lack of effective supervision and restriction on public officials is one of the reasons for the widespread occurrence of rent-seeking by officials and bribery by firms. Moreover, inefficient enterprises are more inclined to bribe than to invest (Birhanu et al., Citation2016), and a high bribery level is associated with low corporate performance (Hanousek & Kochanova, Citation2016; Şeker & Yang, Citation2014). Haider et al. (Citation2018) find that the correlation between state ownership and firms’ financial constraints is not obvious in countries with less corruption. It is therefore necessary to intensify anti-corruption efforts and improve the effectiveness of legislative acts (Luzgina, Citation2017; Osipov et al., Citation2018), thus creating a favourable external environment for firm financing. The government should withdraw from the resource allocation market and reduce its intervention in areas that the market economy can manage well.

These conclusions are useful for the construction of the market economy and government reform in transition economies. However, there are some deficiencies in this study. The World Bank did not follow up with the sample firms studied in this article. We therefore have to use cross-sectional data for empirical study and cannot use this sample to study the long-term effects of corruption on firm financing. Corruption is a sensitive topic and is not public knowledge, so corruption in this article is measured by informal payment, an indirect variable. In addition, this paper does not consider the effects of regional banking competition on firm financing, which is important for policy makers. Previous studies examine the effects of banking competition on firm financing in developed economies, but seldom analyze the impact of banking competition changes in developing countries. Banks in emerging markets hold most of the free capital and are the main sources of financing for enterprises, whereas the equity market is relatively small compared with the loan market. Therefore, future research can extend this study by exploring the effects of banking competition on firms’ access to bank loans in emerging markets and how both firm characteristics shape the influence of banking competition.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adegboye, A. C., & Iweriebor, S. (2018). Does Access to Finance enhance SME innovation and productivity in Nigeria? Evidence from the World Bank Enterprise Survey. African Development Review, 30(4), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12351

- Ahlin, C., & Bose, P. (2007). Bribery, inefficiency, and bureaucratic delay. Journal of Development Economics, 84(1), 465–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.12.002

- Akins, B., Dou, Y. W., & Ng, J. (2017). Corruption in bank lending: The role of timely loan loss recognition. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 63(2–3), 454–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2016.08.003

- Ali, M., Sohail, A., Khan, L., & Puah, C. H. (2019). Exploring the role of risk and corruption on bank stability: evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 22(2), 270–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-03-2018-0019

- Allen, F., Qian, J., & Qian, M. (2005). Law, finance, and economic growth in China. Journal of Financial Economics, 77(1), 57–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.06.010

- Ayyagari, M., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2008). How well do institutional theories explain firms perceptions of property rights? Review of Financial Studies, 21(4), 1833–1871. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhl032

- Barth, J. R., Lin, C., Lin, P., & Song, F. M. (2009). Corruption in bank lending to firms: Cross-country micro evidence on the beneficial role of competition and information sharing. Journal of Financial Economics, 91(3), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.04.003

- Beck, P. J., & Maher, M. W. (1986). A comparison of bribery and bidding in thin markets. Economics Letters, 20(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(86)90068-6

- Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2006). Bank supervision and corruption in lending. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(8), 2131–2163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2005.10.014

- Ben-Yashar, R., Krausz, M., & Nitzan, S. (2018). Government loan guarantees and the credit decision-making structure. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne D'économique, 51(2), 607–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/caje.12332

- Berger, A. N., & Black, L. K. (2011). Bank size, lending technologies, and small business finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(3), 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.09.004

- Berger, A., & Udell, G. (2002). Small business credit availability and relationship lending: The importance of bank organisational structure. Economic Journal, 112(477), 32–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00682

- Berkowitz, D., Caner, M., & Fang, Y. (2012). The validity of instruments revisited. Journal of Econometrics, 166(2), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2011.09.038

- Birhanu, A. G., Gambardella, A., & Valentini, G. (2016). Bribery and investment: Firm-level evidence from Africa and Latin America. Strategic Management Journal, 37(9), 1865–1877. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2431

- Borisova, G., Fotak, V., Holland, K., & Megginson, W. L. (2015). Government ownership and the cost of debt: Evidence from government investments in publicly traded firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 118(1), 168–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.06.011

- Cai, H. B., Fang, H. M., & Xu, L. C. (2011). Eat, drink, firms, government: An investigation of corruption from the entertainment and travel costs of Chinese firms. The Journal of Law and Economics, 54(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1086/651201

- Chen, Y., Liu, M., & Su, J. (2013). Greasing the wheels of bank lending: Evidence from private firms in China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(7), 2533–2545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.02.002

- Cull, R., & Xu, L. X. C. (2003). Who gets credit? The behavior of bureaucrats and state banks in allocating credit to Chinese state-owned enterprises. Journal of Development Economics, 71(2), 533–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00039-7

- Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2008). The law and economics of self-dealing. Journal of Financial Economics, 88(3), 430–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.02.007

- Dreher, A., & Gassebner, M. (2013). Greasing the wheels? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. Public Choice, 155(3–4), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9871-2

- El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C. Y., & Zheng, X. L. (2016). Collectivism and corruption in commercial loan production: How to break the curse? Journal of Business Ethics, 139(2), 225–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2551-2

- Faccio, M. (2010). Differences between politically connected and nonconnected firms: A cross-country analysis. Financial Management, 39(3), 905–927. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2010.01099.x

- Faccio, M., Masulis, R. W., & McConnell, J. J. (2006). Political connections and corporate bailouts. The Journal of Finance, 61(6), 2597–2635. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.01000.x

- Firth, M., Lin, C., Liu, P., & Wong, S. M. L. (2009). Inside the black box: Bank credit allocation in China’s private sector. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(6), 1144–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2008.12.008

- Fungacova, Z., Kochanova, A., & Weill, L. (2015). Does money buy credit? Firm-level evidence on bribery and bank debt. World Development, 68, 308–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.009

- Fungáčová, Z., Shamshur, A., & Weill, L. (2017). Does bank competition reduce cost of credit? Cross-country evidence from Europe. Journal of Banking & Finance, 83(10), 104–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.06.014

- Gonzalez, V. M. (2015). The financial crisis and corporate debt maturity: The role of banking structure. Journal of Corporate Finance, 35, 310–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.10.002

- Greenwood, J., & Jovanovic, B. (1990). Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 1), 1076–1107. https://doi.org/10.1086/261720

- Guariglia, A., & Poncet, S. (2008). Could financial distortions be no impediment to economic growth after all? Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 36(4), 633–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2007.12.003

- Guriev, S. (2004). Red tape and corruption. Journal of Development Economics, 73(2), 489–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2003.06.001

- Haider, Z. A., Liu, M. Z., Wang, Y. F., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Government ownership, financial constraint, corruption, and corporate performance: International evidence. Journal of International Financial Markets Institutions & Money, 53, 76–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2017.09.012

- Hanousek, J., & Kochanova, A. (2016). Bribery environments and firm performance: Evidence from CEE countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 43, 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.02.002

- Harstad, B., & Svensson, J. (2011). Bribes, Lobbying, and Development. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000523

- Houston, J. F., Lin, C., & Ma, Y. (2011). Media ownership, concentration and corruption in bank lending. Journal of Financial Economics, 100(2), 326–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.12.003

- Hsu, P.-H., Tian, X., & Xu, Y. (2014). Financial development and innovation: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 112(1), 116–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.12.002

- Huang, F., & Rice, J. (2012). Firm networking and bribery in China: Assessing some potential negative consequences of firm openness. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(4), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1062-z

- Huntington, S. P. (1979). Political and economic-change in Southern Europe and Latin-America. Europa Archiv, 34(8), 231–242.

- Krueger, A. O. (1974). Political economy of rent-seeking society. American Economic Review, 64(3), 291–303.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2000). Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1–2), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00065-9

- La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2002). Investor protection and corporate valuation. The Journal of Finance, 57(3), 1147–1170. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00457

- Levine, R., Loayza, N., & Beck, T. (2000). Financial intermediation and growth: Causality and causes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 46(1), 31–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(00)00017-9

- Li, H. B., Meng, L. S., Wang, Q., & Zhou, L. A. (2008). Political connections, financing and firm performance: Evidence from Chinese private firms. Journal of Development Economics, 87(2), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.03.001

- Lien, D. H. D. (1986). A note on competitive bribery games. Economics Letters, 22(4), 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(86)90093-5

- Lin, J. Y., Sun, X., & Wu, H. X. (2015). Banking structure and industrial growth: Evidence from China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 58(9), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.02.012

- Liu, Q. G., Pan, X. F., & Tian, G. G. (2018). To what extent did the economic stimulus package influence bank lending and corporate investment decisions? Evidence from China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 86, 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.04.022

- Lui, F. T. (1985). An equilibrium queuing model of bribery. Journal of Political Economy, 93(4), 760–781. https://doi.org/10.1086/261329

- Luzgina, A. (2017). Problems of corruption and tax evasion in construction sector in Belarus. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 5(2), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2017.5.2(8)

- Osipov, G. V., Glotov, V. I., & Karepova, S. G. (2018). Population in the shadow market: Petty corruption and unpaid taxes. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 6(2), 692–710. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2018.6.2(16)

- Owen, A. L., & Pereira, J. M. (2018). Bank concentration, competition, and financial inclusion. Review of Development Finance, 8(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2018.05.001

- Qi, S. S., & Ongena, S. (2019). Will money talk? Firm bribery and credit access. Financial Management, 48(1), 117–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12218

- Qian, J., & Strahan, P. E. (2007). How laws and institutions shape financial contracts: The case of bank loans. The Journal of Finance, 62(6), 2803–2834. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2007.01293.x

- Rajan, R. G., & Zinagales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 559–586.

- Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure - Some evidence from international data. The Journal of Finance, 50(5), 1421–1460. https://doi.org/10.2307/2329322

- Ruan, W. J., Xiang, E. W., & Ma, S. G. (2018). Lending to private firms: Evidence from China on the role of firm openness and bribery. The Chinese Economy, 51(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2017.1368905

- Sapienza, P. (2004). The effects of government ownership on bank lending. Journal of Financial Economics, 72(2), 357–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2002.10.002

- Şeker, M., & Yang, J. S. (2014). Bribery solicitations and firm performance in the Latin America and Caribbean region. Journal of Comparative Economics, 42(1), 246–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2013.05.004

- Song, Z., Storesletten, K., & Zilibotti, F. (2011). Growing like China. American Economic Review, 101(1), 196–233. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.1.196

- Stiglitz, J. E., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. The American Economic Review, 71(3), 393–410.

- Tian, X. W., Ruan, W. J., & Xiang, E. W. (2017). Open for innovation or bribery to secure bank finance in an emerging economy: A model and some evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 142, 226–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2017.08.002

- Toader, T., Onofrei, M., Popescu, A.-I., & Andrieș, A. M. (2018). Corruption and banking stability: Evidence from emerging economies. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 54(3), 591–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2017.1411257

- Wang, Y. Y., & You, J. (2012). Corruption and firm growth: Evidence from China. China Economic Review, 23(2), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2012.03.003

- Weill, L. (2011). Does corruption hamper bank lending? Macro and micro evidence. Empirical Economics, 41(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-010-0393-4

- Wellalage, N. H., Locke, S., & Samujh, H. (2019). Corruption, gender and credit constraints: Evidence from South Asian SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(1), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3793-6

- Wilcox, J. A., & Yasuda, Y. (2019). Government guarantees of loans to small businesses: Effects on banks’ risk-taking and non-guaranteed lending. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 37, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2018.05.003

- Wu, R. (2018). Does competition lead firms to bribery? A firm-level study in Southeast Asia. Atlantic Economic Journal, 46(1), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-017-9566-2

- Wu, R. (2019). Firm development and bribery: An empirical study from Latin America. Atlantic Economic Journal, 47(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-019-09609-6

- Wu, X. (2009). Determinants of bribery in Asian firms: Evidence from the world business environment survey. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9871-4

- Xie, X., Qi, G., & Zhu, K. X. (2019). Corruption and new product innovation: Examining firms’ ethical dilemmas in transition economies. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3804-7

- Yang, D. D. H. (2005). Corruption by monopoly: Bribery in Chinese enterprise licensing as a repeated bargaining game. China Economic Review, 16(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2004.11.003

- Yang, M. M. H. (1989). The gift economy and state power in China. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 31(1), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500015656

- Yeung, G. (2009). How banks in China make lending decisions. Journal of Contemporary China, 18(59), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560802576034

- Zhang, D. Y., Cai, J., Dickinson, D. G., & Kutan, A. M. (2016). Non-performing loans, moral hazard and regulation of the Chinese commercial banking system. Journal of Banking & Finance, 63, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.11.010

- Zheng, X. L., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Kwok, C. C. Y. (2013). Collectivism and corruption in bank lending. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4), 363–390. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.19

- Zhou, J. Q., & Peng, M. W. (2012). Does bribery help or hurt firm growth around the world? Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(4), 907–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-011-9274-4

- Zhou, X., Han, Y., & Wang, R. (2013). An empirical investigation on firms’ proactive and passive motivation for bribery in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(3), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1596-8