?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Using a person-centred statistical approach (latent class analysis) this study aims to categorise young citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina according to their citizenship norms, level of trust in institutions and propensity toward political gender stereotyping. We employed the data from The National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in Bosnia and Herzegovina (NSCP-B&H) 2017, which documents the civic attitudes of a nationally representative sample of adults (18+) from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Since this study focuses on the youth, we extracted a sub-sample of 831 young individuals born between 1987 and 2001. Applying latent class analysis, we derived two distinct classes of young citizens with a unique set of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours related to the role of citizens in modern societies, namely ‘enthusiastic citizens’ and ‘outsiders’. The findings offer valuable insights for policy-makers about the design and implementation of measures that aims to foster active citizenship in the laggard transitional economy. Also, it advances the research agenda on citizenship norms beyond the Western European context.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, citizenship norms have changed considerably in modern societies (e.g., Dalton, Citation2008; Hooghe & Dejaeghere, Citation2007). As a result, a myriad of studies have tried to uncover what do citizens understand by the term ‘citizenship’, ‘good citizenship’ and what forms of citizenship prevail across a range of democratic societies (e.g., Coffé & van der Lippe, Citation2010; Hooghe et al., Citation2016; Hustinx et al., Citation2012; Reichert, Citation2017). Bearing in mind that youth presents the cohort that drives a value shift in modern democracies (Reichert, Citation2017), it is valuable to enhance our understanding of citizenship norms among youth. The present research focuses on young adults in Bosnia and Herzegovina, who have been the target of public policies over the previous decades designed to raise their levels of political literacy and participation. Albeit there is a large body of research providing analytical insight into perceptions, attitudes, and values of youth in Bosnia and Herzegovina ( e.g.,Turčilo et al., Citation2019; UNDP, Citation2017 ) or insight into the practice of peace-building and resolution of dentity/conflict relationship (e.g., Gillard, 2001), to best of our knowledge, no study has been conducted to classify young citizens based on citizenship norms and macro-level social forces (i.e., institutional trust and gender ideologies). By identifying different types of youth citizenship, this study provides valuable information to policy-makers to create and implement policies/programs that foster civic engagement of young people. Also, this study helps to increase the awareness levels of local decision-makers and citizens about the vital role of the civic education policies as instruments of building and maintaining a democratic society.

The intended contribution of this study is two-fold. Firstly, this study explores citizenship norms of young adults in the context of the so-called laggard economy in South-Eastern Europe (SEE) region. Notwithstanding the success in studying young citizenship norms in many Western European societies, researchers have paid less attention to the cases of SEE democracies, which mostly have different political, economic and social contexts that are very important for the formulation of citizenship norms. Bearing this in mind and respecting the characteristics of fragile environment of laggard SEE economies (e.g., weak policies and institutions with the lack of capacity to deliver services to citizens, control corruption or provide sufficient voice and accountability), this study aims to verify and expand existing theories and frameworks pertaining ‘good citizenship’ beyond the Western context. Secondly, the present study goes a step further than previous studies (e.g., Coffé & van der Lippe, Citation2010: Hooghe et al., Citation2016; Reichert, Citation2017) which have investigated the role of normative beliefs in explaining different types of young people’s civic participation by adding two additional domains: (1) citizens’ trust in government and political institutions; and (2) gender ideologies (egalitarianism and traditionalism). Several recent studies have criticised the mainstream literature for taking a ‘narrow’ and normative view of civic participation (Harris et al., Citation2007; Marsh et al., Citation2007). Therefore, the present study strives to create the taxonomy of young citizens based on the nature of the relationship between citizenship norms and macro-level social forces (i.e., institutional trust and gender ideologies). The primary preposition of the present study is that youth in Bosnia and Herzegovina can be classify into groups (classes, clusters) with regards to the citizenship norms and macro-level social forces (i.e., institutional trust and gender ideologies).

We selected the person-centred approach since it accounts for the heterogeneity of the population and has a greater potential to inform policy and practice. Also, the present study strives to identify the demographic characteristics of the explored kinds of civic participation. Overall, this study aims to address the following research question:

RQ: Whether there are any homogeneous subgroups (subclasses) of young citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina exhibiting different profiles of citizenship norms, institutional trust and political gender stereotyping?

This article is structured as follows. We begin with a discussion on theoretical and empirical perspectives of ‘good citizenship’ followed by an overview of the concept of institutional trust and political gender stereotypes. The next part introduces an overview of person-centred statistical approach, data, and measures. The analyses are presented in the third section. We conclude with a summary of the results and suggestions for further research.

2. Literature review

2.1. ‘Good citizenship’ – theoretical and empirical perspectives

Citizenship is an ‘essentially contested concept’ with a non-definitive meaning (Bosniak, Citation2008; Coffé & van der Lippe, Citation2010; Lister, Citation2007). Moreover, the meaning of the concept of citizenship varies across historical, social, political and cultural contexts. In other words, the modern economic and political environments carve our understanding of citizenship (Skeggs, Citation2004). Citizenship represents an abstract, universal concept, but at the same time it is also “interpreted and articulated in specific national social and political contexts, reflecting historical traditions and institutional and cultural complexes” (Lister, Citation2007, p.55).

Moosa-Mitha (Citation2005) present three dominant theories of citizenship: individualistic (liberal theories and neoconservatism), relational (civic republicanism and communitarianism) and difference-centred (radical and post-structuralist). Marsh et al. (Citation2007) argue that normative debates about citizenship revolve around three main issues: the extent of citizenship (the appropriate criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of individuals as citizens), the content of citizenship (the balance between rights and responsibilities) and the depth of citizenship (direct participation of citizens - citizens as subjects vs. citizens as sovereigns). Based on these three distinctions in thinking about citizenship, Marsh et al. (Citation2007) also identified three broad approaches to citizenship: (1) rights-based approaches, i.e., those that focus upon the rights that individuals have as citizens (liberal theories)) ; (2) responsibility-based approaches i.e., those that stress the responsibilities or duties of citizenship (communitarianism and civic republicanism, and neoconservatism); and participatory-based approaches i.e., those that see citizenship in terms of active participation (radical and post-structuralist). Both classification schemas (taxonomies) of existing citizenship theories emphasise three critical pillars of citizenships: rights, responsibilities, and participation.

In recent years, scholars have proposed the emergence of a new kind of citizenship, described in somewhat different terms as ‘active citizenship’ (Marsh et al., Citation2007; Onyx et al., 2012), ‘responsible citizenship’ (Kymlicka & Norman, Citation1994) and ‘good citizenship’ (Bolzendahl & Coffé, Citation2013; Coffé & van der Lippe, Citation2010; Hooghe et al., Citation2016; Reichert, Citation2017; Theiss-Morse, Citation1993). ‘Good citizenship’ focuses on norms of what citizens ‘should do’ and, thereby, explicitly taps into responsibility-based approaches to citizenship. Different conceptualisations of the ‘good citizenship’ have been proposed in the academic literature. The majority of studies emphasize three principal domains of ‘good citizenship’ namely political activity (e.g., voting, being active in social and political associations and keeping a watch on government), civic duty (e.g., paying taxes and obeying the law), and social responsibility (understanding the opinions of others, helping those worse off). However, empirical studies have varied in their definition and conceptualisation of ‘good citizenship’. Theiss-Morse (Citation1993), for example, suggests that ‘good citizenship’ includes four dimensions: voting and being informed, contacting activities, conventional participation, and unconventional participation. Similarly, Reichert (Citation2017) proposes three domains of ‘good citizenship’: conventional participation, socio-political participation and community participation.

Denters et al. (Citation2007) examined the public’s views of ‘good citizenship’ in the Western and Eastern European societies. They assumed that there would be different views of ‘good citizenship’ reflecting the pluralism of civic norms in modern European societies. However, they concluded that idea of ‘good citizenship’ does not vary across Western and Eastern European societies and it includes three dimensions: law-abidingness (not evade taxes, obeying laws), solidarity (think of others), and critical and deliberative principles (form own opinion, be self-critical). It has been argued that the younger generation is cultivating its own sense of ‘good citizenship’. Dalton (Citation2008) empirically distinguished two faces of ‘good citizenship’, namely duty-based citizenship (e.g., the obligation to vote and pay taxes) and engaged citizenship (e.g., to understand the opinions of others and to help those worse off). McBeth et al. (Citation2010) showed that duty-based citizenship continues to be the prevalent view among the youth, although the uptake of engaged citizenship becomes apparent. Using the data from European Social Survey (ESS) for four Eastern European countries (Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland), Coffé and van der Lippe (Citation2010) found that citizenship mindedness varies between the different countries. For instance, citizens from Poland hold the view that citizenship has two facets, namely engaged and duty-based. Citizens from Hungary and the Chech Republic think about citizenship in terms of duty-based citizenship norms (voting and obeying laws), while Slovenian citizens are inclined more towards engaged citizenship (Coffé & van der Lippe, Citation2010).

Scholars have also developed typologies of citizens based on their citizenship norms. For instance, Theiss-Morse (Citation1993) identified four perspectives of ‘good citizenship’ representing different conceptualisations of the participatory duties of good citizens: ‘representative democracy’, ‘political enthusiast’, ‘pursued interest’, and’indifferent’. The ‘representative democracy’ presumes that good citizens have to be informed about political issues so they can vote wisely. The ‘political enthusiast’ perspective highlights the employment of a range of participatory activities (e.g., voting, writing letters to politicians, discussing politics, being informed about politics). The ‘pursued interest’ perspective assumes that citizens have to be engaged in decision making at the level of community. The ‘indifferent’ perspective implies that citizens should vote and be informed about politics, but casts aside the usage of unconventional forms of civic participation (e.g., public demonstration, signing a petition). Using the International Civic and Citizenship Education Survey for 38 countries, Hooghe et al. (Citation2016) identified five distinct types of citizenship norms held by different groups of young people: engaged citizens, duty-based citizens, subject citizens, respectful citizens, and all-around citizens. Engaged citizens emphasised the importance of human rights protection, but they attach a little importance to the traditionally duty-based behaviours such as voting and political party involvement. For the duty-based citizens, they uncovered reversed normative priorities. Subject citizens are more prone toward duty-based behaviours, and they are characterized by the deficiency of political interest and political efficacy. Respectful citizens tend to engage in duty-based and engaged-based behaviours, and they are very respectful towards government representatives. All-around citizens scored very high on both behaviours (duty-based and engaged based), and they have a high degree of trust in political institutions. Similarly, Reichert (Citation2017), based on conceptions of ‘good citizenship’ held by young Australians, identified four classes of young citizens: engaged, duty-based, enthusiastic and subject.

It should be noted that some authors (e.g., Abdelzadeh & Ekman, Citation2012; Doorenspleet, Citation2012; Kowalewski, Citation2019) argue that in the less developed democratic regimes, activism is based on criticism, negativism and complaint, which gives a rise of ‘critical’ citizenship. As suggested by Kowalewski (Citation2019), critical citizens are those who aspire toward a democracy as their ideal form of government, yet they remain deeply skeptical when evaluating how democracy works in their own country.

Distilling from previous research which tries to use available conceptual models of citizenship to generate newer taxonomies of young citizen participation, we argue that both perspectives of political participation (traditional and nontraditional also known as ‘civil’, ‘society’ or ‘community) should be considered. Thus, in the present study, we focus on the duty-based dimensions of participation (e.g., voting) as well as community dimension of participation (voluntary and personal activities such as improving local community conditions, charity work, or just helping others).

2.2. ‘Good citizenship’ and institutional trust

The literature on social capital emphases the relations between social capital (trust, social norms, and networks) and civic community, participation, and membership (Putnam, Citation2000). The social capital theory assumes that trust and relationships are the main pillars of economic development and the political and social well-being of a community. Trust, a product of high levels of social capital, can increase citizen participation in groups and networks that help them identify shared priorities and more effective voice their demands (Coffé & van der Lippe, Citation2010; Hooghe & Dejaeghere, Citation2007). Unlike the general and social trust, institutional trust can induce citizens to cooperate more in public and private affairs.

Two major explanations for institutional trust are cultural theories and institutional theories. Cultural theories postulate that institutional trust has its origins in political culture (see, e.g., Inglehart, Citation1999). In other words, values and attitudes independently create institutional trust. By contrast, institutional theories posit that trust in institutions is shaped by the citizens’ evaluation of the performance of public institutions (see, e.g., Coleman, 1990; Hetherington, Citation1998). The main idea of institutional theories is that citizens who are satisfied with the performance/output of various types of public institutions will show trust and support toward those institutions. Previous studies focusing on citizenship norms and institutional trust have empirically verified the link between trust in institutions and types of citizenship. For instance, Howard and Gilbert (Citation2008), using a cross-national sample of citizens from the USA, Eastern and Western Europe, discovered that active citizens are more likely to be trustful toward public institutions than inactive citizens.

Moreover, in their study of citizenship norms in four Eastern European countries (Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland), Coffé and van der Lippe (Citation2010) empirically verified the significant relationship between trust in institutions and both components of citizenship norms (engaged citizenship and duty-based citizenship). However, Dalton (Citation2008) claims that the level of institutional trust differs among engaged and duty-based citizens. He advocates that engaged citizenship norm is paired with lower levels of institutional trust. Thus, it appears that engaged citizens are inclined to embrace a less favourable attitude towards the performance of political institutions (Hooghe et al., Citation2016). Based on the above discussion, it seems lucrative to deepen our understanding of the notion of institutional trust across different types of citizenship. It has been asserted that young citizens are more suspicious about politicians and governments, they have less knowledge about politics, and they are less likely to join political parties, unions and other formal political organisations (Harris et al., 2007). At the same time, the lack of institutional trust drives young citizens to become the principal agents of cause-oriented activities by which they try to influence government or politics. Thus, we expect that young citizens with different patterns of civic participation will have different levels of institutional trust.

2.3. ‘Good citizenship’ and political gender stereotypes

Citizenship also may be differentiated based on political ideology, i.e., the degree to which citizens support or reject the status quo (Jost et al., 2008). Applying the unidimensional (liberal-conservative or left-right) conceptualisation of political ideology, we posit that conservatives and liberals differ in their general attitudes toward gender stereotypes in politics. Gender stereotypes are “consensual beliefs about the attributes of women and men” (Eagly & Karau, Citation2002, p. 574). On a general level, a typical woman is stereotyped as warm, gentle, kind, passive, loyal, communal, concerned with the well-being and welfare of others, compassionate, and moral, whereas a typical man is viewed as aggressive, assertive, ambitious, analytical, competitive, controlling, decisive, independent, individualistic, rational, and a stronger leader (Devroe & Wauters, Citation2018). In the political arena, gender stereotyping refers to “the gender-based ascription of different traits, behaviour or political beliefs to male and female politicians” (Huddy & Terkildsen, Citation1993, p. 120). Thereby, citizens have different expectations about the issues governed successfully by male and female politicians, about their character traits and their ideological positions. Bearing in mind that men are seen as competitive and assertive, research has shown that people expect male politicians to be more appropriate for challenging tasks in which the primary aim is to conquer rivals. Alternatively, since women are perceived as communal and social, female politicians are supposed to be better in communal topics (Alexander & Andersen, Citation1993; Devroe & Wauters, Citation2018). Gender role expectations are learned and internalised via socialisation processes in social institutions (e.g., family and the education system), and they are shaped by values and norms which are inherent to the specific social context (Parsons, Citation1951). Thus, we argue that the attitude toward gender roles is a discriminating factor between different patterns of young citizen participation. This expectation is closely related to the social and cultural context of studied country - Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the Bosnia and Herzegovina, a traditional family model was prevalent up to the 1990s, with women’s duties mainly in the private sphere of the household, particularly childcare, and men as the sole, full-time employed breadwinners. Albeit Bosnia and Herzegovina made a step forward towards the promotion of gender equality through legal and institutional frameworks, there are still obstacles hindering women’s civic participation. This gap in the available infrastructure for gender equality (e.g., rules and regulations) and reality is mostly the result of retraditionalisation of gender roles i.e., the return to the old gender role models assigning men to the public life of work and politics and women to the private life of housework and motherhood (Brajdić Vuković et al., Citation2007).

3. Research context: A case of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the states established as a result of the disintegration of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). Amongst the former Yugoslav republics, only Slovenia followed the patterns of democratic transition in which civil society had a vital role and political elites were capable to follow trend of political pluralism and the democratization of public life (Fink-Hafner & Hafner-Fink,Citation2009). In Bosnia and Herzegovina, due to the lack of an oppositional civil society, national parties successfully manipulated ethnic feelings of voters and von the first multi-party elections in 1991. Therefore, the disintegration of the former Yugoslavia and the recognition of Bosnia and Herzegovina as an independent country in April 1992 did not yield to democratization (Fink-Hafner & Hafner-Fink, Citation2009). Moreover, the Bosnian war (1992–1995) contributed to the delayed and even more complex movement towards democratization. The process of the transition to democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina was ‘unfrozen’ by the ‘Dayton Peace Agreement’, negotiated and finalized in November 1995. The main aim of the ‘Dayton Peace Agreement’, was to provide a peace-building, state-building and democratization in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although many elements of the peace-building section that the ‘Dayton Peace Agreement’ provided have been successfully implemented, the results are less impressive in the areas of state-building and democratization (Keil & Kudlenko, Citation2015; Majstorović et al., Citation2015). The road towards democratization had been laid down in Article I.2 of the Constitution, articulating that ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina shall be a democratic state, which shall operate under the rule of law and with free and democratic elections. Annex III (Elections) and VI (Human Rights) of the ‘Dayton Peace Agreement’ also implies the focus on democratic elections as well as fundamental rights and freedoms. Although the ‘Dayton Peace Agreement’ was envisaged an embedded democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina, it is not straightforward what type of democracy it should be (Keil & Kudlenko, Citation2015;). Also, local obstacles, the absence of a coherent strategy by international state-builders and the paradoxes deep-rooted in the ‘Dayton Peace Agreement’ (e.g., power-sharing mechanisms between and among different levels and jurisdictions of government) have led to a lack of progress and resulted in the stagnation of democratization. Since it is unclear who is the responsible party in the process of state-building and democratization (local political elites or international actors), the transition to democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina is still lagging behind other Central and Eastern European states (Marčić, 2015). According to the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (Bertelsmann-Stiftung, Citation2018), Bosnia and Herzegovina has exhibited the stagnation in democratic development over the past eight years. It is ranked 43rd in 2018, behind Slovenia (6th), Croatia (14th), Serbia (19th), Montenegro (20th), and Macedonia (31th). Moreover, the Varieties of Democracy ‘Liberal Democracy Index’ (V-Dem Annual Democracy Report, Citation2018) indicates the incremental decline of democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina over the last decade. The V-Dem index particularly pinpoints the problems of media censorship and harassment of journalists, civil society repression, the autonomy of opposition parties, electoral irregularities and vote-buying, noncompliance with the judiciary and legal constraints on the executive, and lack of effective legislative oversight (Kapidžić, Citation2020). Since nature of the democratization process has been shaped by two broad political agendas promoted by local elites and international actors, namely ‘nationalizing state’ agenda and ‘Europeanizing state agenda’ (Mulalić & Karić, Citation2016) the political regime of Bosnia and Herzegovina is often characterized as ‘hybrid’, ‘semi-autocratic’, or ‘competitive authoritarian’ regime (Kapidžić, Citation2020). On the surface, it appears that the ‘Dayton Peace Agreement’ established the transition to good, active, responsible citizenship. However, the problems such as the deficiencies of the rule of law, the presence of corruption, the under-developed culture of responsibility, accountability and transparency of institutions of governance as well as strong nationalistic rhetoric of political parties, hinder citizens’ ability to act as ‘good, ‘active’, and ‘responsible’ citizens. However, the 2013–2014 protests in Bosnia and Hercegovina (e.g., ‘Baby Revolution’ ‘Social uprising’) have reshaped citizenship through collective actions and lead to the rise of the so-called ‘activist citizenship’ (Milan, Citation2017). The activist citizenship refers to the “collective or individual actions that make a difference as they rupture socio-historical patterns’ (Milan, Citation2017, p. 3). The model of plenums reinforced a rights-based approach to citizenship by shifting the focus from the respect for and observance of human rights established in the Constitution to the radical change in the political system (Milan, Citation2017) Thus, it can be argued that citizens’ participation in the plenums fuelled the development of ‘critical’ citizenship. As suggested by Abdelzadeh and Ekman (Citation2012, p. 179), “critical citizens can be viewed as a resource for democracy and driving force for political reform”.

4. Methodology

4.1. Person-centred statistical approach

Variable-centred approaches endeavour to describe the relationships among variables and to identify significant predictors of outcomes assuming that the population is homogeneous concerning these relationships (Laursen & Hoff, Citation2006). On the other hand, the person-centred statistical approach assumes the heterogeneity of the population and strives to uncover unique groups of individuals by detecting the similarity of response patterns (Laursen & Hoff, Citation2006). Within a person-centred approach, two analytic procedures have been used to classify individuals into clusters: traditional cluster analysis techniques (e.g., hierarchical cluster analysis and K-means clustering) and latent class analysis (hereafter LCA). Opposite to conventional clustering approaches, LCA is the more rigorous technique with several advantages. Firstly, LCA relates to the probability distribution of the analysis. The cluster classification is based on probabilities, allowing the identification of different probabilities of belonging to each cluster present in the model. Secondly, LCA is model-based, which means there is a statistical model that is assumed to come from the population from which the data was gathered. In the traditional cluster analysis, the decision about the number of classes is arbitrary or subjective. However, in LCA, a statistical model allows the comparison to be statistically tested, so that the decision to adopt a particular model is less subjective, or at least has some grounding for comparison. The third advantage relates to the inclusion of variables of mix scale types. K-means clustering is limited to the quantitative variables while LCA can use variables of different scale types (e.g., continuous, nominal, ordinal or any combination of these (Vermunt & Magidson, Citation2000; Magidson & Vermunt, Citation2002). In recent years, the application of LCA as a probabilistic form of cluster analysis has become widespread in the various fields of the social sciences.

The LCA model for observed categorical items can be defined as follows. Let yj represent element j of a response pattern y. Let I (yj = rj) equal 1 when the response to item j is rj, and 0 otherwise. Then:

(1)

(1)

Where, γc is the probability of membership in latent class c and ρj, rj|c is the probability of response rj to item j, conditional on membership in latent class c (see Lanza et al., Citation2007). The γ parameters represent the latent class membership probabilities. The ρ parameters represent item response probabilities conditional on latent class membership. The γ and ρ parameters can be estimated by maximum likelihood using the EM algorithm. The parameters of the model presented in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) cannot be estimated or interpreted without specifying a value of c. In many instances, there is a theoretical explanation for selecting a certain number of classes – c. However, researchers prefer to use the data to guide their decision about an appropriate number of classes. The data-driven approach reduces the possibility of under-extraction (choosing a small number of classes - c) and over-extraction (choosing a large number of classes – c). By comparing and contrasting the fit of models with one, two, three, latent classes, it is possible to choose the model (i.e., the number of classes) that fits the data the best. If a c-class model fits significantly better than a (c - 1) -class model, then the actual population is assumed to have at least c classes. As suggested by Nylund et al. (2007), the decision about the optimal number of classes should be based on fit test: the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (aLMRT), the sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SSABIC), the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), and the entropy. The Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR) is the global test of model fit in which the LRT distribution is approximated, thus making the comparison of neighbouring class models possible. The authors also developed an ad hoc adjustment to the LMR to improve its accuracy of inferences. The LMR and adjusted LMR (aLMR) compare the improvement in fit between the (c - 1) and c class models and provide a p-value that can be used to assess whether the increase in fit resulting from adding one more class is statistically significant with 1 - α % confidence (Nylund et al., Citation2007). SSABIC is a relative fit index which imposes some penalty on the log-likelihood function when more parameters are estimated. Comparatively lower values of SSABIS indicate better fitting models. The BLRT uses a bootstrap resampling method to approximate the p-value of the generalised likelihood ratio test comparing the c-class model with the (c - 1) -class model. For BLRT, a small probability value (e.g., p < .05) points out that the c-class model offers a superior fit to the data than the (c - 1) class model.

The final category of the fit tests used to assess latent class models is the measure of entropy. The entropy is based on the uncertainty of the classification. The uncertainty of classification is high when the posterior probabilities are very similar across classes. The normalised version of entropy, which scales to the interval [0, 1], is commonly used as a model selection criteria indicating the level of separation between classes. A higher value of normalised entropy represents a better fit; values > 0.80 indicate that the latent classes are highly discriminating (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2007). In applying LCA, the first step is to determine the optimal number of latent classes for describing the research population accurately. The second step includes the interpretation of l derived latent classes based on conditional probabilities. LCA can be applied in an exploratory manner by beginning with the one-class model and systematically increasing the number of classes to assess model fit.

4.2. Data and measures

4.2.1. Sample

This study uses data from The National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions in Bosnia and Herzegovina (NSCP-B&H) 2017, which documents the civic attitudes of a nationally representative sample of adults (18+) from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Since the focus of this study is youth, we have extracted data only for specified age cohort (e.g., youth). Because the concept of youth is becoming more and more blurred, there is yet no consensus about the commonly accepted definition of youth cohort. Thus, we used the national youth definition, which is based on age. Youth Law in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina defines youth as between 15 and 30 years, whereas the youth policy briefing (2011) in Republika Srpska notes youth as those persons between the age of 16 and 30 years. Therefore, our sub-sample consists of 831 individuals born between 1987 and 2001.

4.2.2. Measures

Based on the theoretical premises, we created seven original indices: five for ‘good citizenship’ (voting, news exposure, contacting activities, conventional participation, and unconventional participation), one for institutional trust and one for political gender stereotype. Voting Index is created based on the categorical responses of respondents to the following question: “How often do you vote in the elections?” The answers are categorical on a scale of four elements: 1 – regularly; 2 – sometimes; 3-rarely, and 4 – never. Voting Index is converted into a binary variable (equals to 1 for the respondents who vote regularly and 0 otherwise). News Exposure Index is derived from responses on the following four items: “On average, how often do you:” (a) read the political/economic/civic news from newspaper; b) watch political/economic/civic news on television; (c) listen to political/economic/civic news on the radio; (d) use the online news sources to obtain political/economic/civic news or information. Initially, these items were continuous variables ranging from 1 to 7 and coded such that high scores represent a higher level of exposure to news. Using a median as the cut-off point, we created the News Exposure Index, which takes the value of 1 for a high level of respondent’s exposure to news and 0 otherwise. Conventional Participation Index captures three conventional citizenship behaviours (‘been a member of a political party/group’, ‘worked without pay in a political party or action group’, ‘and volunteered to monitor/observe elections’). Three unconventional citizenship behaviours (‘taken part in a lawful public demonstration’, ‘boycotted certain products’, ‘and signed a petition’) are used to create Unconventional Participation Index. Three items representing contacting activities (‘contacted a politician’, ‘contacted a government or local government official’, and ‘posted a message with political content in social media’) are used to create Contacting Index. The possible answers for conventional behaviours, unconventional behaviours and contacting activities are measured using dichotomous scales (“Yes” vs “No”). Three indices (conventional participation, unconventional participation, and contacting activities) are binary variables, each taking a value of 1 if the respondent had been engaged in at least one of three corresponding activities. Institutional Trust Index is based on the answers of respondents to the following three items: “How would you rate the work and service by each government level in Bosnia and Herzegovina”: (a) “institutions/state-level government”; (b) “entity-level institutions”; (c) “Municipality/city level institutions”. A 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = ‘extremely poor’ to 7 = ‘excellent’ was used for each item. A composite score of Institutional Trust Index was transformed into a binary variable using the median as a cut-off point. Political gender stereotypes are measured with three items: (a) “On the whole, men make better political leaders than women and should be elected rather than women”; (b) “Women are too emotional and experience mood swings too often to be effective leaders”; and (c) “Women are not good politicians because they are not assertive and dominant enough”. These items were measured on a 7 point-Likert scale ranging from 1 - “strongly disagree’’ to 7 - ‘‘strongly agree”. A summed composite score of political gender stereotypes was dichotomised using the median as a cut-off point.

5. Results and discussion

We started our analysis with the most parsimonious one-class model (“all young citizens are the same”). After that, we estimated the fit of subsequent models by enhancing the number of latent classes, aiming to identify the most parsimonious model that ensures the best fit to the data. Models fit indices for one-, two-, and three - class solutions are presented in .

Table 1. Information criteria and statistical indices for models.

The relative model fit is compared using the sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion - SSABIC (Collins and Lanza, Citation2010). In most cases, the favoured solution is the one with the lowest SSABIC value. The SSABIC value was lowest for the two-class model, suggesting that the two-class model is superior to the model with three classes. The Lo-Mendell-Rubin test (LMRT) compares the model fit between solutions with c and c-1 classes. The p-value less than 0.05 indicates that the class solution, c, is significantly better than the class solution, c - 1. The Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (aLMRT) has a value of 298.321 for the two-class model, and it is statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level. Thus, two classes make a significant increase in fit over one class. However, aLMRT is not significant for the three-class model, suggesting that adding a third class does not make a substantial improvement in fit over two classes. The BLRT test also supports the two-class solution. More precisely, BLRT is insignificant for the three-class solution, indicating that the three-class model is not statistically better than the two-class model. Furthermore, based on the entropy, we confirm that the two-class model provides the most precise distinction between classes. Based on the statistical goodness of fit and theoretical interpretability, we opt for a two-class solution.

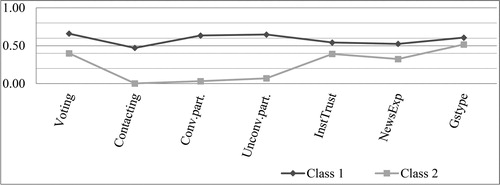

summarises the two-class model of young citizens and their scores on the respective indicators. To highlight the distinct characteristics of the classes, we assigned labels to each class. Even though these labels may oversimplify the actual situation, resulting typology makes different groups of young citizens more appealing and facilitates the discussion of our findings.

Table 2. Two classes of young citizens derived from the LCA and respective.

Young citizens labelled as ‘enthusiastic’ are very likely to participate in conventional and unconventional forms of political participation. The probability of engaging in different types of conventional and unconventional activities is around 60%. Also, the results show that enthusiastic citizens are more likely to contact politicians and government officials, as well as to post political messages on social media platforms, like Facebook and Twitter. These results are in line with the theory of political socialisation according to which news media can inform, educate, and mobilise young citizens to become politically interested and active (Kruikemeier & Shehata, Citation2017; Strömbäck & Shehata, Citation2010). Although enthusiastic citizens are prone to follow engaged citizenship norms, they show a relatively high propensity to vote (around 66% likelihood of voting). Therefore, enthusiastic citizens have an image of citizenship that is both engaged and duty-based. Enthusiastic citizens generally consider the political institutions to be trustworthy, supporting the theoretical view that the higher the institutional trust citizens have, the stronger their social and political engagement (Coffé & van der Lippe, Citation2010; Dalton, Citation2006). In terms of political gender stereotyping, they are more inclined toward a conservative view about gender roles and gender identities (61% probability of exhibiting political gender stereotypes). The ‘ethusiatic citizens’ exibit some chracteristics of so-called ‘critical citizens’ described as citizens who are inclined to support the democracy as an ideal, but not very satisfied with how democracy is working in their country (Doorenspleet, Citation2012). Thus they tend to engage more in unconventional forms of civic participation aiming to foster consolidation, stability and development of a democratic system in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Young citizens labelled as ‘outsiders’ are highly disengaged from politics. They show low propensities to participate in conventional and unconventional political activities. Involvement in the conventional form of political participation such as being a member of the political party or working without pay in a political party/action group is extremely low. Furthermore, for the outsiders, the probability of participating in unconventional activities (signing a petition, participating in the public demonstration) is very low (7%). Thus, it seems that outsiders are not inclined to adhere to engaged citizenship norms. However, they exhibit a high probability (about 40%) of following a duty-based citizenship norm (voting), suggesting that for them voting us an essential building block of ‘good citizenship’. Whereas enthusiastic citizens are more likely to express high levels of institutional trust (likelihood about 54%), the outsiders show a lower probability (about 39%) of trusting their political institutions. In comparison with enthusiastic citizens, outsiders are less likely to express a conservative view about gender roles and gender identity (probability lies around 52%).

LCA conditional probabilities for two classes of young citizens are shown in . The y-axis plots the conditional probabilities that members of a latent class will score high on indicators of ‘good citizenship’ depicted on the x-axis.

6. Conclusion

This study contributes to the theoretical debate about citizenship norms in multiple ways. First, our study showed that there are indeed distinct groups of young citizens who express different norms of ‘good citizenship’. Using LCA, the present study revealed two distinct classes of young citizens with a unique set of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours related to the role of citizens in modern societies. The findings of the present study indicate that young citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina can be divided into two classes, namely enthusiastic citizens and outsiders. Therefore, the current research provides further evidence for the claim that young people living in the same economic, political and social environment tend to follow different types of citizenship norms (e.g., Hooghe et al., Citation2016).

Second, the present study advances the research agenda on citizenship norms and young civic participation by examining these topics in the realm of a laggard transitional economy in SEE (i.e. Bosnia and Herzegovina). Although Bosnia and Herzegovina had some of the best starting conditions in 1989 for implementing a smooth transition from a state-planned economy to a market economy, it faced difficulties in its implementation (e.g., disintegration of the Yugoslav federation in mid-1991, military conflicts, high political and economic instability). Thus, transition-related institutional changes implemented in this particular unstable political and economic environment have not favoured fast economic and social development (Uvalic, Citation2012). Since the environment setting of so-called laggard SEE countries characterized by the state-fragility is very different from that in advanced, exploring what patterns of civic participation young citizens are adopting in the specific environment provides an opportunity to verify existing theories, as wells as extend and develop new frameworks.

Third, the findings of this study to some extent, contradict Dalton’s Dalton (Citation2008) thesis that there is a decline in duty-based norms in a variety of modern societies. Our findings that citizenship based on duty (e.g., voting) prevails among young citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although there is a small group of enthusiastic citizens (16%), the present study suggests that traditional norms of citizenship will not merely disappear but instead continue to coexist with more recent engaged norms.

Fourth, in contrast to previous studies that emphases primarily the role of citizenship norms (i.e., what citizens should do”), the current research focuses on actual citizenship behaviours (i.e, “what citizens actually do”). Moreover, the present study extends the conceptualisation of citizenship by using the political ideology (i.e., beliefs about male and female politicians) and institutional trust as indicators in explaining different types of citizenship.

The current study has provided some reflections on practical implications. Public managers and policymakers in Bosnia and Herzegovina should pay attention to the development of effective policies and measures to enhance the participation of young citizens in both traditional (conventional) and unconventional political activities. In the light of possible implications of the present study for future political behaviour of present-day youth, it is worth emphasising that the enthusiastic citizens and outsiders differ from each other most notably with regard to the participation in conventional and unconventional political activities. Thus, policy-makers should encourage teachers, curriculum-developers, schools to focus on citizenship education.

The Ministries responsible for the implementation of youth policy (Ministry of Family, Youth and Sports in Republica Srpska and Federal Ministry of Culture and Sports) need to take a more active role in the development of civic participation of young citizens through the establishment of youth centers at the state, entity, and municipality/city levels. Also, to increase the political participation of young citizens, government institutions should develop new pathways through which youth should be involved in the process of shaping policy and affecting government decision-making. For instance, the establishment of youth committees/parliaments, the organization of youth training centers and camps about civic education and engagement, the usage of social media or websites to inform youth about governmental programs and collect feedback from young citizens are effective pathways to foster youth engagement. Moreover, non-government organizations (NGOs) can be used to direct the energy and creativity of young citizens towards solving youth- related problems and help them to build social and leadership skills which are necessary for active citizenship. Also, all stakeholders (government institutions, NGOs, educational institutions, political parties) should create youth-targeted information campaigns about democratic rights and values aimed to promote civic activities that are in line with democracy and tolerance.

This study has some shortcomings that need to be highlighted. First, this study is based on cross-sectional data. Although cross-sectional studies may provide insight into different groups of young citizens, they are not able to describe changes over time. Thus, there is a need for longitudinal research to examine developments, trajectories, and attitude change as well as the precise relationships between citizenship norms and future civic behaviours more closely. Such longitudinal analysis could also clarify transitions between the distinct groups of young citizens. Second, this study is limited to one country; young citizens in different parts of the world with different cultures may exhibit different citizenship norms, for apparently varied reasons. Finally, this study emphasised young citizens; thus, it would be lucrative that future studies explore citizenship norms of citizens across different age groups (e.g., younger citizens versus older citizens). Furthermore, it would be valuable to compare the patterns of civic participation among the different cohorts of young people with a particular focus on patterns of younger age cohorts without the right to vote.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdelzadeh, A., & Ekman, J. (2012). Understanding critical citizenship and other forms of public dissatisfaction: An alternative framework. Politics, Culture and Socialization, 3(1/2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299304600305

- Alexander, D., & Andersen, K. (1993). Gender as a factor in the attribution of leadership traits. Political Research Quarterly, 46(3), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299304600305

- Bertelsmann-Stiftung. (2018). Bertelsmann Transformation Index. https://www.bti-project.org/en/home/. Accessed 20 April 2020

- Bolzendahl, C., & Coffé, H. (2013). Are ‘good’ citizens ‘good’ participants? Testing citizenship norms and political participation across 25 nations. Political Studies, 61(1_suppl), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12010

- Bosniak, L. (2008). The citizen and the Allien: Dilemmas of contemporary membership. Princeton University Press.

- Brajdić Vuković, M., Birkelund, G. E., & Štulhofer, A. (2007). Between tradition and modernization: Attitudes toward women’s employment and gender roles in Croatia. International Journal of Sociology, 37(3), 32–53. https://doi.org/10.2753/IJS0020-76593703002

- Coffé, H., & van der Lippe, T. (2010). Citizenship norms in Eastern Europe. Social Indicators Research, 96(3), 479–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9488-8

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press.

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Political Studies, 56(1), 76–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x

- Dalton, R. (2006). Citizenship norms and political participation in America: The good news is … the bad news is wrong (CDACS Occasional Paper, 2006–2001). Washington, DC: The Center for Democracy and Civil Society, Georgetown University.

- Denters, S. A. H., Gabriel, O., & Torcal, M. (2007). Norms of good citizenship. In J. W. J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero, & A. Westholm (Eds.), Citizenship and involvement among the populations of European democracies. A comparative analysis (pp. 87–107). Routledge.

- Devroe, R., & Wauters, B. (2018). Political gender stereotypes in a list-PR system with a high share of women MPs: Competent men versus leftist women? Political Research Quarterly, 71(4), 788–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918761009

- Doorenspleet, R. (2012). Critical citizens, democratic support and satisfaction in African democracies. International Political Science Review, 33(3), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512111431906

- Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

- Fink-Hafner, D., & Hafner-Fink, M. (2009). The determinants of the success of transitions to democracy. Europe-Asia Studies, 61(9), 1603–1625. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130903209152

- Gillard, S. (2001). Winning the peace: Youth, identity and peacebuilding in Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Peacekeeping, 8(1), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533310108413880

- Harris, A., Wyn, J., & Younes, S. (2007). Young people and citizenship. An everyday perspective. Youth Studies Australia, 26, 19–27.

- Heinen, T. (1996). Latent class and discrete latent trait models: Similarities and differences. Sage.

- Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of political trust. American Political Science Review, 92(4), 791–808. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586304

- Hooghe, M., & Dejaeghere, Y. (2007). Does the “monitorial citizen” exist? An empirical investigation into the occurrence of postmodern forms of citizenship in the Nordic countries. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30(2), 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00180.x

- Hooghe, M., Oser, J., & Marien, S. (2016). A comparative analysis of ‘good citizenship’: A latent class analysis of adolescents’ citizenship norms in 38 countries. International Political Science Review, 37(1), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512114541562

- Howard, M. M., & Gilbert, L. (2008). A cross-national comparison of the internal effects of participation in voluntary organizations. Political Studies, 56(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00715.x

- Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111526

- Hustinx, L., Meijs, L. C. P. M., Handy, F., & Cnaan, R. A. (2012). Monitorial citizens or civic omnivores? Repertoires of civic participation among university students. Youth & Society, 44(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X10396639

- Inglehart, R. (1999). Trust, well-being and democracy. In M. E. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and trust (pp. 88–120). Cambridge University Press.

- Jost, J. T., Nosek, B. A., & Gosling, S. D. (2008). Ideology: Its resurgence in social, personality, and political psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 3(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00070.x

- Kapidžić, D. (2020). Subnational competitive authoritarianism and power-sharing in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 20(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2020.1700880

- Keil, S., & Kudlenko, A. (2015). Bosnia and Herzegovina 20 Years after Dayton: Complexity Born of Paradoxes. International Peacekeeping, 22(5), 471–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2015.1103651

- Kowalewski, M. (2019). Dissatisfied and critical citizens: The political effect of complaining. Society, 56(5), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-019-00398-x

- Kruikemeier, S., & Shehata, A. (2017). News media use and political engagement among adolescents: An analysis of virtuous circles using panel data. Political Communication, 34(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1174760

- Kymlicka, W., & Norman, W. (1994). Return of the citizen: A survey of recent work on citizenship theory. Ethics, 104(2), 352–381. https://doi.org/10.1086/293605

- Lanza, S. T., Collins, L. M., Lemmon, D. R., & Schafer, J. L. (2007). PROC LCA: A SAS procedure for latent class analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 671–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575602

- Laursen, B. P., & Hoff, E. (2006). Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52(3), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2006.0029

- Lister, R. (2007). Inclusive citizenship: Realizing the potential. Citizenship Studies, 11(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020601099856

- Magidson, J., & Vermunt, J. K. (2002). Latent class models for clustering: A comparison with K-means. Canadian Journal of Marketing Research, 20, 37–44.

- Majstorović, D., Vučkovac, Z., & Pepić, A. (2015). From Dayton to Brussels via Tuzla: Post-2014 economic restructuring as europeanization discourse/practice in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 15(4), 661–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2015.1126093

- Marcic, S. (2015). Informal Institutions in the Western Balkans: An obstacle to democratic consolidation. Journal of Balkan and near Eastern Studies, 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2014.986386

- Marsh, D., O’Toole, T., & Jones, S. (2007). Young people and politics in the United Kingdom: Apathy or alienation? Palgrave Macmillan.

- McBeth, M. K., Lybecker, D. L., & Garner, G. (2010). The story of good citizenship: Framing public policy in the context of duty-based versus engaged citizenship. Politics & Policy, 38(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2009.00226.x

- Milan, C. (2017). Reshaping citizenship through collective action: performative and prefigurative practices in the 2013–2014 cycle of contention in Bosnia & Hercegovina. Europe-Asia Studies, 69(9), 1346–1361. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2017.1388358

- Moosa-Mitha, M. (2005). A difference-centred alternative to theorisation of children’s citizenship rights. Citizenship Studies, 9(4), 369–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020500211354

- Mulalić, M., & Karić, M. (2016). The politics of peace and conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Epiphany: Journal of Transdisciplinary Studies, 9(1), 139–148.

- Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2007). Mplus users: Statistical analysis with latent variables – user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modelling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Onyx, J., Kenny, S., & Brown, K. (2012). Active citizenship: An empirical investigation. Social Policy and Society, 11(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746411000406

- Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. Free Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

- Reichert, F. (2017). Young adults’ conceptions of ‘good’ citizenship behaviours: A latent class analysis. Journal of Civil Society, 13(1), 90–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2016.1270959

- Skeggs, B. (2004). Class, self, culture. Routledge.

- Strömbäck, J., & Shehata, A. (2010). Media malaise or a virtuous circle? Exploring the causal relationships between news media exposure, political news attention and political interest. European Journal of Political Research, 49(5), 575–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01913.x

- Theiss-Morse, E. (1993). Conceptualizations of good citizenship and political participation. Political Behavior, 15(4), 355–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992103

- Turčilo, L., Osmić, A., Kapidžić, D., Šadić, S., Žiga, J., & Dudić, A. (2019). Youth Study Bosnia and Herzegovina 2018/2019. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES).

- UNDP. (2017). Socio-economic perceptions of young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. https://www.ba.undp.org/content/bosnia_and_herzegovina/en/home/library/publications/young-people-in-bih-share-their-socio-economic-perceptions-and-e.html

- Uvalic, M. (2012). Transition in Southeast Europe: Understanding Economic Development and Institutional Change. In G. Roland (Ed.), Economies in transition: The long-run view (pp. 364–399). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2000). Latent GOLD’s user’s guide. Boston: Statistical Innovations Inc.

- V-Dem Annual Democracy Report. (2018). Democracy for All? V-Dem Institute. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3345071