?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The emerging literature on migration and security is predominantly focused on the threats that migration movements may have to the security in destination countries. This article shifts the focus to a migrant’s sending country and explores different socio-economic factors that could be associated with the process of radicalisation and the development of violent extremism among youth there. We use survey data collected from a sample of 4,500 young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina (B.i.H.) by USAID MEASURE-B.i.H. An index of radicalisation is constructed and used as a dependent variable. It is based on Bhui et al. and measures sympathies for violent protest and terrorism. It is regressed on a set of demographic characteristics, migration experience and social behaviour. The model was estimated by ordinary least squares (O.L.S.) with the index as a continuous dependent variable. The findings suggest that a range of factors including demographic characteristics, location, employment status, income, practicing of religion, and civic and political activism are associated with a degree of sympathy for violent extremism among youth in B.i.H. These results should provide useful insights into the relationship between the drivers and extremism, which then should help institutions to design more effective preventative and countering measures.

1. Introduction

Following increased number of terrorist attacks round the world, a large scholarly attention and contribution has been given to better understanding the phenomena and drivers of radicalisation and violent extremism, particularly among youth. In general, some authors (e.g., Gullain & Lynn, Citation2009; Harriet et al., Citation2015) distinguish between macro- (country-level), meso- (community and identity related) and micro-level (individual) factors as drivers of radicalisation and violent extremism. Systematic reviews of research on this topic show inconclusive evidence (Harriet et al., Citation2015) about the main drivers influencing radicalisation and violent extremism.

In B.i.H. and the Western Balkan region the topic of preventing youth radicalisation has increasingly become a part of policy discussions over past several years. This subject has gained prominence due to media’s attention on returning B.i.H. citizens who had gained battlefield experience in Syria and Iraq as members of Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (I.S.I.L.), and to some extent to those returning from Ukraine as supporters of pro-Russian rebels (Azinović & Bećirević, Citation2017; Becirevic, Citation2018; Perry, Citation2016). Therefore, in the current public discourse, threat of radicalisation is primarily viewed through the prism of Islamic or I.S.I.L. radicalisation. However, in the last 20 years, citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina (B.i.H.) have witnessed many other forms of radicalisation and extremism, which have been mostly neglected (Becirevic, Citation2018). Those are different forms of ethnic nationalism and separatism and religious extremism, to which we add radical anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (L.G.B.T.) movements and so-called left-wing nationalists. Such movements can be viewed as radical only under the condition that its adherents are willing to use or are ready to justify the use of violence and consequently sacrifice human life in order to support their cause or viewpoint or make political protest.

Therefore, in this study, we assume that radicalisation is a construct used to explain social and psychological processes by which ordinary citizens become so aggrieved that they are willing to sacrifice their lives and the lives of innocent civilians to make a political protest (Bhui et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, it is important that we make a distinction between individuals and groups which might adhere to extreme views or ideologies but are not supportive of violence and those who might hold mainstream views within their communities or adhere to socially acceptable ideologies but are supportive of violence and violent means for initiating a social change. We assume the latter to be radicalised because of their support of violence and willingness to sacrifice human life in order to make a political protest or instigate political change. This distinction is important and relevant to B.i.H.’s context because of the legacy of most recent armed conflict and still present competing and mutually exclusive war narratives among the country’s three main ethnic groups (see, for example, Berdak, Citation2015).

As pointed by Silke (Citation2008), young people are perceived to be more at risk of radicalisation than any other age group, since the most people that join a terrorist groups are young and male. Furthermore, a number of studies point to general susceptibility of young males to taking risky behaviour and resorting to violence (Budd et al., Citation2005; Farrington, Citation2003; Silke, Citation2008). In B.i.H. young people are considered to be at a particularly vulnerable social and economic position because of their extremely high rates of unemployment and social exclusion (Commission for International Justice and Accountability [C.I.J.A.], 2016, p. 36; Becirevic, Citation2018, p. 22), which could induce grievance and desire to revenge. This makes young people more at risk of radicalisation than any other age groups in B.i.H.

Historically, extremism and radicalisation have had their roots in struggles related to nationalism or ethnicity, political beliefs, and class struggle. The process of radicalisation usually happens over a period of time and involves different factors and dynamics. People do not turn to violent extremism overnight and without a cause. Drivers of radicalisation are usually complex, multifaceted and can pertain to various political, social, economic, religious and other factors that might engender conditions in which terrorist organisations could engage in recruitment and win support (OSCE, Citation2012). Neumann (Citation2017) emphasises indiscriminate repression, violent conflict, and migration as the main drivers of current radicalisation. The search for meaning or belonging can also be another important contributing factor. Neumann (Citation2017) points out that radicalisation almost always involves authority figures, charismatic leaders, or tightly knit peer groups for generating trust, commitment, loyalty and peer pressure.

Although unemployment among youth is ‘the usual suspect’ among possible drivers of radicalisation and violent extremism, the research evidence produced so far is ambivalent. The findings suggest that a majority of terrorists were either unemployed or underemployed, e.g., 88% of Chechen militants were unemployed (Speckhard & Ahkmedova, Citation2006). On the other hand, the evidence also suggests that a rather large number of terrorists were relatively well educated (Speckhard & Ahkmedova, Citation2006) and gave up successful careers, or combined them with terrorist activity (Sageman, Citation2004). However, there is at least some agreement in the literature suggesting that militant groups recruit from the ranks of the unemployed (Hassan, Citation2012).

Analogous to the relationship between unemployment and radicalisation, the same applies to evidence on relationship between poverty/deprivation and radicalisation and violent extremism. Research (e.g., Dalgaard-Nielsen, Citation2010) restricted solely to terrorism, tends to conclude that terrorists are definitively not poor, deprived or even relatively deprived. As Krueger and Laitin (Citation2008) put it in a summary of the literature to date, ‘studies at the individual level of analysis have failed to find any direct connection between education, poverty, and the propensity to participate in terrorism. … If anything, those who participate in terrorism tend to come from the ranks of the better off in society’. Furthermore, their econometric analysis shown that economics explains the target, not the origin, of transnational terrorism. Krueger and Jitka (Citation2003) acknowledge that poor countries produce more terrorists, but insist that GDP per capita is not related to the number of terrorists when controlling for other factors, such as the extent of civil liberties. Opinion poll data in Pakistan suggests that support for militancy is higher among middle-class respondents than lower-class respondents (Blair et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, in Central Asia, there is evidence that Islamic radicals ‘have been drawn from the relatively well-off and educated urban populations as well as from among the poorer segments of the Central Asian societies’ (Omelicheva, Citation2010).

Graff (Citation2010) points out that there is no robust empirical relationship between poverty and radicalisation, but it is weak states (the majority of them are also very poor) that are more vulnerable to extremism. Fearon and Laitin (Citation2003) also identify poverty and state weakness as one of the most important salient conditions for the onset of civil war. More importantly, violent extremist groups operating in war-afflicted countries are frequently representing economically deprived minorities. This suggests that poverty may in fact be a factor inducing extremist violence – but only of certain types, e.g., in a civil war situation, or in low-income but highly unequal countries.

We can conclude based on the above review of literature that income poverty, deprivation and underemployment do not provide sufficient explanations for violent extremism. However, it is suggested that they can contribute and provide a fertile ground, which in combination with other factors, particularly grievances, create an environment conducive to violent extremist groups.

The aim of this study is to analyse the effect of different socio-economic factors on possible radicalisation among youth in B.i.H., by using a novel approach to quantify degree of sympathy towards radicalisation. The study is based on the analysis of data from a survey of youth aged 15–30. Consequently, in the quantitative analysis we need to model the relationships and operationalise these concepts in such a manner to be relevant for B.i.H., including the effect of migration experience, experiences of discrimination, grievances, as well as rising importance of religious identity.

Considering the nature of B.i.H.’s recent war and troublesome post-war recovery process, the threats of youth radicalisation have been ever present. In official documents it can be found that perceived risk factors include wartime and post-conflict trauma, perceived or actual social exclusion, peer influence, petty crime and juvenile delinquency, previous experiences with law enforcement authorities, alienation from family members, poor economic opportunities, engagement with religious individuals or communities, and the support (or lack of) available through social services (Ministry of Security of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Citation2016). In addition to the aforementioned, B.i.H. still has a large number of people living in displacement within the country as a direct result of the war during which more than 50% of the population was forced to change its place of living. This includes an estimated 1.2 million refugees who fled during the conflict outside the country (Helsinski komitet za ljudska prava u BiH, 1998). Following the conflict, there has been considerable degrees of movement across the border, as refugees and displaced persons choose to return to B.i.H. and as many migrate, often to diaspora locations in Western Europe. Nowadays maintaining links with relatives and friends living abroad has never been easier due to the rise in Internet accessibility and the emergence of online social networks, as well as relatively cheap possibilities for travel. Moreover, recent literature points out that a significant number of terrorist attacks were committed by individuals who spent the majority or the entirety of their lives in Western societies. This study aims to capture the effect of migration experience of respondents.

2. Methodology

The aim of this study is to identify the main socio-economic factors that could be associated with the process of radicalisation and the development of violent extremism among youth, including the exposure to social remittances, i.e., either through personal migration experience or through regular contacts with B.i.H. citizens currently living abroad. In our study, we use Bhui et al.’s (Citation2014) definitions of radicalisation and violent extremism, where radicalisation is defined as the process by which a person comes to support terrorism and forms of extremism leading to terrorism. Violent extremism is described as endorsement of violence to achieve political objectives. Also, as pointed out in the literature, we need to acknowledge that there are different forms of extremism and not all extremism is necessarily violent.

The list of indicators for measuring dependent variables is designed accordingly and included in the questionnaire (Appendix A). Bhui et al.’s (Citation2014) paper uses a new measure of radicalisation based on sympathies for violent protest and terrorism, which we find appropriate for the purpose of answering the research questions. Moreover, we do not a priori assume that radicalisation and extremism is based on religious beliefs or belonging to a certain religious communities, as was often assumed in previous research. Therefore, rather than reducing radicalisation to religion-based motives, our model uses religion as one of the possible explanatory indicators among a wide set of socio-economic and individual level indicators.

The indicators were grouped into a set of seven dimensions of the Index, based on the IOM study (2016). The dimensions include both indicators of resilience and of radicalisation, and are named as follows: (1) positive youth engagement; (2) youth–community relations; (3) economic opportunities; (4) social and life-skills; (5) risk awareness and community resilience capacity; (6) sympathy for ideologies and causes of violent extremism; and (7) presence of violent extremism in local community. The composition of the Index was further checked statistically through a factor analysis. The table describing the composition of the Index, as well as indicating the list of questions from the survey that were used to measure indicators and their allocations per dimension is provided in Appendix A. As we can see from the table in Appendix A, Positive youth engagement dimension describes civil society and political engagement, but also involvement in extracurricular activities and voluntary work. Youth–community relations dimension measures level of trust and satisfaction with institutions, civil society and religious institutions. The economic opportunities dimension of the Index describes a person’s feeling of injustice, deservedness and economic opportunities in the country. The social and life-skills dimension describes an individual’s value complexity, tolerance and acceptance, trust in neighbours and social network. Sympathy for V.E. ideologies and causes measures the degree to which respondents individually express their sympathy towards use of violence as means to achieve a political/religious goal, and in particular their views and support for foreign fighters. Finally, the remaining two dimensions are about community-level external factors. Risk awareness and community resilience capacity, and the presence of violent extremism in the local community, include responses to questions about a respondent’s perception of the risk within a community due to the presence of local influencers and recruiters, as well as the capacity of a community to resist them through self-organisation and cooperation among civil society actors.

For the independent variables, a range of different studies were consulted and used to make a comprehensive list of indicators that should be potentially used in analysing the phenomenon and identifying the main drivers of radicalisation and violent extremism. According to Ranstrop (Citation2016), violent extremism can be best conceptualised as a combination of micro- and meso-level factors that create an infinite number of combinations. These factors include: (1) individual socio-psychological factors; (2) social factors; (3) political factors; (4) ideological and religious dimensions; (5) the role of culture and identity issues; (6) trauma and other trigger mechanisms; and three other factors that are a motor for radicalisation: (7) group dynamics; (8) radicalisers/groomers; and (9) the role of social media. It is the combined interplay of some of these factors that causes violent extremism. In our case, some of these factors are actually indicators the Index is composed of, so they are not included in the model as independent variables. For example, a set of individual socio-psychological factors that are considered to influence radicalisation include grievances and emotions such as: alienation and exclusion; anger and frustration; grievance and a strong sense of injustice; feelings of humiliation; rigid binary thinking; a tendency to misinterpret situations and acquire conspiracy theories; a sense of victimhood; personal vulnerabilities; and counter-cultural elements. They are included in the Index. This also applies to variables from the groups of factors named ‘Political factors’, ‘Ideological and religious dimensions’, ‘Group dynamics’ and ‘Radicalisers/groomers’.

Individual factors (∑indiv) include respondent’s sex, age, marital status, education level, employment status and ethnicity. Household level factors included in the model (∑hh) are household’s size and household’s income. Social factors (Σsocial) include political and civic activism. Religion (Σreligion) includes both a set of dummy variables for religious affiliation of the respondent, as well as the frequency of actively practicing religion. We also included a set of location dummies (Σregion).

Migration factors (Σmigration) include migration experience, as well as contact with relatives abroad, as a measure of possible connections with more or less radicalised communities in other countries.

2.1. Model specification

The empirical model to be estimated is specified as follows:

(1)

(1)

EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) is a reduced form representing a set of factors that are considered to be associated with the degree of radicalisation and violent extremism among youth.

The dependent variable (Index) is created by combining approaches used in Bhui et al. (Citation2014) and IOM Community Based Approach to Support Youth in Targeted Municipalities in BiH (IOM) (Citation2016), where different items are used to create a composite measure of support for violent protest, radicalisation and terrorism. The measure of sympathy for radicalisation is a commonly used proxy for violent extremism in literature, since it would not be ethically acceptable to use questions that would measure an individual’s degree or experience of violent extremism behaviour. The responses to each individual question was normalised into values 0–100. A higher score indicates less support for violent protest, radicalisation and terrorism.

Since there is no appropriate counterfactual that would allow a quasi-experimental approach to estimation, the analysis of the model described in the previous section was conducted by a regression analysis of the model specification presented in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . This model is estimated by a simple ordinary least squares (O.L.S.) method.

2.2. Data

Data used for the empirical testing of the model are taken from the BiH Youth Survey, conducted by USAID/BiH’s MEASURE Activity in 2017. The survey covers a representative sample of around 4,5000 young people (aged 15- to 30-years-old) in B.i.H. The sampling procedure applied in this survey was a two-stage random stratified sampling, using preliminary estimates from the 2013 BiH Census as a sampling frame. The first stage stratification was by 18 regions in B.i.H. In the second stage, the sample was further stratified by urbanisation level categories within each region, resulting in 49 sampling strata. Selection of sampling units was implemented in two stages. Primary sampling units (municipalities) were selected using simple random sampling from each of 18 geographical regions. Secondary sampling units (streets and village/rural settlements) were selected in the second stage, also using simple random sampling. Then, as the survey was implemented as a computer-assisted personal interviewing (C.A.P.I.) survey, interviewers were instructed to go to randomly selected addresses (using ‘Random Walk Technique’, after being given a starting point in each of the sampling units) and conduct interviews with a representative sample of civilian, non-institutionalised young adults aged 15- to 30-years-old (randomly selected using ‘Last Birthday Procedure’).

The descriptive analysis of the data used is presented in the remainder of this section. First, we present descriptive statistics of continuous variables ().

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of continuous variables.

Source: Own calculations from USAID/BiH Youth Survey 2017.

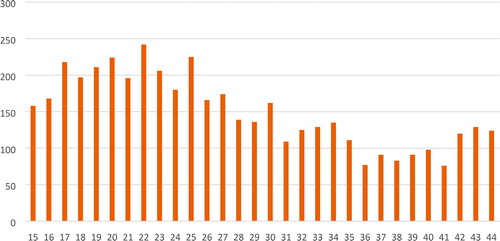

We present the number and share of respondents for the indicative variables. Since the model includes sets of indicative variables for age and region, we also present the share of respondents in each category of these two variables. For the sake of clarity of presentation of the table, these two variables are presented separately in . presents the sample structure by age of respondent. presents the geographical distribution of the sample.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of indicative variables.

Table 3. Number of respondent by region.

Source: Own calculations from USAID/BiH Youth Survey 2017.

As we can see, the sample is balanced with regards to sex, age, marital status, education level, and location. Only with regards to ethnicity and religion, we see that Croats/Catholic religion is under-represented in the sample. It is also worth noting that there is a rather small share of respondents being engaged in civic activism, which is in line with previous studies showing rather low civic activism among the population of B.i.H. Finally, we can see that the vast majority of youth have regular access to the Internet.

3. Results

3.1. Results from regression analysis

The following section describes results of the regression analysis of the model described in the EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . The results are presented in . The results presented include values of estimated coefficients and statistical significance of the coefficients. Since the dependent variable is the Index that measures sympathy towards violence and radicalisation in the way that a higher value indicates less sympathy, the coefficients should be interpreted in a manner that positively indicate a coefficient suggested association of the respective variable with a decrease in radicalisation and increase of resilience. Estimated coefficients from both the full and reduced models are presented in . The full model estimated coefficients for all the variables specified is presented in EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) . In the reduced model, a set of variables that were found to be statistically insignificant were excluded in order to estimate a parsimonious model.

Table 4. Results of the model estimation.

According to the results from both models presented in , we can see that the same set of variables appears to be statistically (in)significant in both models. The results suggest that sex, ethnicity, living in a rural area, religion and migration (if living abroad or if having relatives abroad) are not associated with more or less sympathy towards radicalisation and violence. For those reasons, these variables were excluded from the estimation in order to estimate a parsimonious model.

Most of the estimated coefficients are hypothesised. Household size is associated with less radicalisation. Also, being married is associated with less radicalisation. The same applies for education level, where more education is associated with less radicalisation, but only after secondary level. Social factors, such as participation in civic actions or in elections were also included in the extended model. Results suggest that those who are more active (in civic actions or voting in elections, for example) are less likely to be radicalised. Having more regular access to the Internet is also associated with less radicalisation and extremism.

From the results of both the full and the reduced model we can see that, although radicalisation is relatively equally distributed among different ethnic or religious groups, more active practicing of religion is associated with lower degree of radicalisation. This is important and perhaps to some extent a surprising finding. Another surprising finding is that employment status has a negative indication in that the unemployed, unpaid family workers and students are less radicalised than employed individuals. However, this finding corresponds to previous research that suggested that many extremists or terrorists were not unemployed, but underemployed, which may have caused some grievances and sense of injustice. Finally, our results suggest that a household’s income is in negative association with the Index, suggesting that individuals from more well-off households are more likely to be sympathetic towards radicalisation and violent extremism.

The age of respondents was included in the model as a set of indicative variables in order to relax the assumption of a linear effect of age on radicalisation. Also, regional dummies were included as control variables. As the results suggest, only the ages 22–24, 26, 29, 31 and 33 are associated with more radicalisation. Furthermore, all regions compared to the benchmark Una-Sana Canton appear to be more radicalised, particularly in Bosnian Podrinje Canton, Pale region, Central Bosnia and Brdsko District. However, due to a limited number of observations in many of the above categories for both age and region, these findings should be taken with a caution.

4. Conclusions and recommendations

A number of radicalisation push-factors – including demographic, social, political and economic reasons that fuel grievances, a sense of injustice and discrimination, social exclusion and marginalisation, as well as disappointment with democratic processes – are present in B.i.H. However, as the findings from the regression analysis suggest, the radicalisation among youth is the result of a complex interplay of various factors and should not necessarily be simplified to any of them. Some of the important factors that are correlated with a higher degree of radicalisation among youth are higher household’s income, lower education attainment, marital status, employment status, and not voting nor taking part in civic activities. On the other hand, gender, living in urban areas or having relatives abroad is not associated with more or less radicalisation. Our findings also suggest that sympathies for radicalisation are equally present among all ethnic and religious groups in B.i.H.

Furthermore, our findings suggest that identification of the main drivers of radicalisation among youth is not straightforward. Radicalisation should be explained rather as a process where different factors intertwine, influencing the overall level of deprivation of an individual, which then affects her/his social life, and her/his perception about the community. This in turn significantly affects a degree of each person’s resilience or sympathy towards radicalisation. Moreover, our findings suggest that by focusing on only one of the problems among youth, i.e., unemployment or employment skills or similar, without addressing other factors that affect their social life and general well-being, will not result in desired outcomes. Therefore, in order to decrease the vulnerability of youth towards inclusion in radical groups and participation in violent activities in B.i.H., we need broader measures that should be targeted across all religious and ethnic communities and all socio-economic groups. Considering the country’s recent war and presence of the war narratives, the future research should be focused on linkages between radicalisation and perceptions about the outcome of the war and understanding of what would be a just peace.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Azinović, V., & Bećirević, E. (2017). A waiting game: Assessing and responding to the threat from returning foreign fighters in the Western Balkans. Regional Cooperation Council, Sarajevo.

- Becirevic, E. (2018). Extremism research forum: Bosnia and Herzegovina report. https://wb-iisg.com/wp-content/uploads/bp-attachments/5595/erf_bih_report_British-Council.pdf

- Berdak, O. (2015). Reintegrating veterans in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia: Citizenship and gender effects. Women's Studies International Forum, 49, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.07.001

- Bhui, K., Nasir, W., & Edgar, J. (2014). Is violent radicalisation associated with poverty, migration, poor self-reported health and common mental disorders? PLoS One, 9(3), e90718. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090718

- Blair, G., Christine Fair, C., Malhotra, N., & Shapiro, J. N. (2013). Poverty and support for militant politics: Evidence from Pakistan. American Journal of Political Science, 57(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00604.x

- Budd, T., Sharp, C., Weir, G., Wilson, D., & Owen, N. (2005). Young people and crime: Findings from the 2004 offending, crime and justice survey. Home Office Statistical Bulletin 20/05. Home Office.

- Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA). (2016). Radicalisation and violent extremism in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Assessment Report.

- Dalgaard-Nielsen, A. (2010). Violent radicalisation in Europe: What we know and what we do not know. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 33(9), 797–784.

- Farrington, D. P. (2003). Key results from the first forty years of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. In T. P. Thornberry & M.D. Krohn (Eds.), Taking stock of delinquency (pp. 137–183). Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

- Fearon, J. D., & Laitin, D. D. (2003). Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. American Political Science Review, 97(01), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000534

- Graff, C. (2010). Poverty, development and violent extremism in weak states. Brookings Institution Press.

- Gullain, D., & Lynn, C. (2009). Guide to the drivers of violent extremism. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Harriet, A., Andrew, G., Sasha, J., Shena, R.-T., Emily, W. (2015). Drivers of violent extremism: hypotheses and literature review. RUSI. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a0899d40f0b64974000192/Drivers_of_Radicalisation_Literature_Review.pdf

- Hassan, M. (2012). Understanding drivers of violent extremism: The case of Al-Chabab and Somali Youth. Combating Terrorism Centre West Point CTC Sentinel, 5.

- Helsinski komitet za ljudska prava u BiH. (1998). Izvjestaj o stanju ljudskih prava u BiH, januar – decembar 1998. Godine.

- IOM Community Based Approach to Support Youth in Targeted Municipalities in BiH. (IOM). (2016). Methodology for the research of relationship between unemployment and violent extremism. Version 1.0, July 27 .

- Krueger, A. B., & Jitka, M. (2003). Education, poverty and terrorism: Is there a causal connection? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(4), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533003772034925

- Krueger, A. B., & Laitin, D. D. (2008). Kto kogo?: A cross-country study of the origins and targets of terrorism. In P. Keefer & N. Loayza (Eds.), Terrorism, economic development, and political openness (pp. 148–173). Cambridge University Press.

- Ministry of Security of Bosnia and Herzegovina. (2016, March 1–3). Final report: Countering violent extremism in BiH. Tabletop Exercise.

- Neumann, P. R. (2017, September). Countering violent extremism and radicalisation that lead to terrorism: Ideas, recommendations and good practices from the OSCE region. International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR), King’s College London.

- Omelicheva, M. Y. (2010). The ethnic dimension of religious extremism and terrorism in Central Asia. International Political Science Review, 31(2), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512110364738

- OSCE. (2012). Consolidated framework in the fight against terrorism. Permanent Council Decision No. 1063, PC.DEC/1063. http://www.osce.org/pc/98008.

- Perry, V. (2016, July). Initiatives to prevent/counter violent extremism in South East Europe. Regional Cooperation Council, Sarajevo.

- Ranstrop, M. (2016). The root causes of violent extremism. RAN Issue Paper 1–5. Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN).

- Sageman, M. (2004). Understanding terror networks. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Silke, A. (2008). Holy warriors: Exploring the psychological processes of Jihadi RADICALISATION. European Society of Criminology and SAGE Publications, 5(1), 99–123. http://archives.cerium.ca/IMG/pdf/SILKE_2008_Holy_Warriors_-_Exploring_the_psychological_Processes_of_Jihadi_Radicalization.pdf https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370807084226

- Speckhard, A., & Ahkmedova, K. (2006). The making of a martyr: Chehen suicide terrorism. APA PsycNET.

- United States Department of State Publication, Bureau of Counterterrorism. (2017, July). Country reports on terrorism 2016. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/272488.pdf