Abstract

In theory, poverty reduction is associated with economic growth and equal access to opportunities for all citizens, regardless of their age, gender and income. Pakistan has reduced its poverty headcount by nearly 66% between 2002–2016, despite poor governance, weak institutions, mediocre economic growth, and poor social indicators. Using ADL/VAR and Granger causality tests, the paper empirically proves that change in political regimes, openness of media and foreign aid have contributed to alleviation of poverty in the country. The paper finds that the shift towards a stable democratic regime has facilitated the delivery of social services, regardless of the motive. Furthermore, it finds that free flow of information through the media has created an awareness among the masses about their rights; the access to information has led to a more equitable distribution of social services. Foreign aid has also contributed to alleviating poverty by focusing on targeted programs towards different groups with the help of various international organizations. These finding have important implications for interactions between the developed and underdeveloped economies as well as the economic and social benefits of democratic regimes.

1. Introduction

Reduction in poverty is widely associated with rising GDP growth rates and access to equal opportunities regardless of gender, income, religion or ethnicity (Haq, Citation2005). Economic literature has advanced away from economic growth as the ultimate objective of all human endeavors and towards the realization of this growth in the form of human development (Ranis et al., Citation2000). This poverty reduction phenomenon emerges from a deliberate policy effort to create a link between economic growth and human development indicators. An appreciable change in the human development indicators critically hinges on the focus of public policy on education, health, nutrition, and redistribution of assets through fiscal policy instruments. Such public policies are poorly functioning in Pakistan thus periodic spikes in the economic growth rates have presented no direct linkage to improvements in the social sector (Younis et al., Citation2015).

Even during its spikes of higher growth, for some indicators such as infant mortality and female literacy, Pakistan has performed worse than its low-income counterparts like Bangladesh (Easterly, Citation2001). Part of the problem can be attributed to inefficient implementation of social policy programs. For example, the Social Action Program (SAP), launched in 1991, targeted the shortcomings of Pakistan’s social development. Despite the heavy disbursements into SAP, the program failed to have any significant impact (Social Policy and Development Center (SPDC), Citation1997). In fact, the primary enrolments worsened over the 1990s and enrolments in private schools increased, reflecting dissatisfaction with public schools. The main reasons for its failure are lack of cost effectiveness and financial sustainability. Despite most basic services falling under the umbrella of the local governments, many functions had to go through higher level government offices, leading to overstaffing and higher costs of infrastructure (SPDC, Citation1997). The poor social development indicators are not reflective of a lack of initiatives but rather, a flawed method of implementation. Despite the erratic rates of growth however, poverty has steadily declined in the country since 2002.

This reduction in poverty comes associated with welfare gains including the ownership of assets, quality of housing and an increase in school enrolment, especially for girls (World Bank, Citation2016). However, the existence of public service policies does not guarantee that they actually reach the intended audience (Ross, Citation2006) and the failure of SAP is just one example. Therefore, the answer to the poverty puzzle lies not in the paradigm of growth but instead on the canvas of development.

For our research, we include variables that either feature heavily in Pakistan’s economy or have changed significantly during our period of interest. They are: democracy, foreign aid and free media. According to the World Bank Economic Development Indicators (Citation2017), Pakistan has consistently ranked in top 15 recipients of foreign aid in the world. Private TV channels were issued licenses by PEMRA for the first time in 2002, which started a new wave of revolution in media. As of 2019, there are 38 news channels in 5 languages operating in the country. The political system in Pakistan has also changed significantly between 2002–2019, switching from a dictatorship in 2002 under General Pervez Musharraf to a democracy in 2007. Given the large changes occurring in these areas between 2002 and 2016, we choose to focus our research on their impact on poverty reduction in Pakistan.

Existing literature finds that the impact of foreign aid varies, depending on the type of regime present in the country. Democratic regimes are more likely to incorporate the conditionality of the aid extended and hold up their sides of the agreement with donors (Kono & Montinola, Citation2009). Furthermore, foreign aid may also promote democracy, to a small extent, through means of technical assistance from donors for the electoral process, promotion of civil organizations and the freedom of press, among other factors. Jones and Tarp (Citation2016) conclude that stable flows of foreign aid have a small, positive effect on improving the quality of institutions in a democracy. Furthermore, allocation of aid is more efficient under a democratic regime (Morrison, Citation2007); an increase in foreign aid and presence of democracy combined may be more effective in combating poverty. Kersting and Kilby (Citation2014) suggest that aid promotes the reforms in a democracy by helping to establish the necessary infrastructure and mechanisms, which facilitate development. However, they also add that donors may be more partial towards democratic countries, which means that the relationship between foreign aid and democracy is not straightforward but also incorporates other variables. Another important aspect of foreign aid is explained by Easterly (Citation2007), who dismisses the notion that foreign aid leads to economic growth. However, foreign aid may lead to development in the absence of growth by improving the health and education infrastructures in recipient countries.

The role of media in combination with democracy is also an important aspect for poverty reduction. For example, Amartya Sen (Citation2004) summarizes that the presence of democracy leads to security of social welfare, by allowing the poor to penalize the government through the electoral process and through the means of free media. He illustrates this rationale with the example of India, which historically experienced several famines under the British regime. Under a democratic government that is subject to public criticism, with free press, famines in India have been reduced drastically (Sen, Citation1999). Free media in a democracy helps social welfare in two ways: Firstly, taking the example of famines in India, it keeps both the government and the opposition parties informed about upcoming food shortages. This results in mounting pressure on the government to respond in time and also allows the opposition to challenge the government if it fails to respond appropriately (Myhrvold-Hanssen, Citation2003). Secondly, free media allows the voters greater transparency on their political candidates of choice, both the positives and the negatives. Due to inadequate access to media, the poor may be marginalized socially and economically because they do not have the proper information available to elect a competent and credible candidate (Keefer & Khemani, Citation2005).

The paradox apparent here is Pakistan’s declining poverty, despite slow economic growth and poor delivery of public services. This paper attempts to examine the underlying reasons for poverty reduction in Pakistan since 2002 in the face of an erratic economic growth. Section 2 introduces the poverty figures in Pakistan, Section 3 attempts to explain the phenomenon of falling poverty numbers using existing literature, Section 4 presents the methodology and results, which Section 5 discusses in detail. Section 6 concludes.

2. Poverty puzzle-the numbers

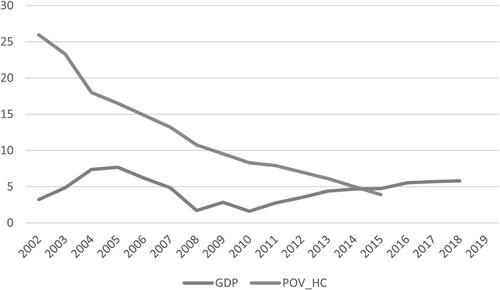

The incidence of poverty in Pakistan has been reduced continuously since 2002. This fall in poverty has taken place in the last fifteen years, during which time, performance of the economy has been erratic with spurts of high growth periods followed by steep decline, indicating a weakening relationship between poverty and macroeconomic variables (Hoynes et al., Citation2006) ().

Figure 1. Annual GDP growth and poverty headcount in Pakistan, 2002–2018.

Source: World Development Indicators.

After 2005, the economic conditions considerably worsened. The economy was fraught with unemployment, rise in inflation levels and depreciating currency. The oil price shock in the world market, accompanied by regulatory and market failures domestically, were the root cause of this economic set back. The economy did pick up again, at a slower pace, under the stabilization package of the IMF. However, contrary to the performance of the economy, the incidence of poverty continued to show a smooth decline. Thus, it seems that changes in economic indicators are inversely related to changes in poverty since 2002 ().

A validation exercise was carried out by the World Bank to substantiate the poverty data for Pakistan and their findings corroborated the fall in poverty. Given the 2011 measure of headcount, Pakistan’s poverty has declined by 66% from 2003–2014 (The World Bank Group Citation2016, World Bank). Given this success in poverty alleviation, the Government of Pakistan announced a new poverty line in 2016 that sets even higher standards of well-being. Even when using this new line as reference, and back casting it, one can observe a reduction in poverty by more than half.

The gains from reduction in the number of people living below the poverty line are even more perceptible with the associated increase in their living standards and well-being. World Bank Pakistan Development Update (Citation2016) shows the increase in ownership of assets such as motorcycles, televisions and refrigerators by the poorest quintiles. This increase was also accompanied with an increase in brick homes versus mud homes and flushing toilets in the lowest quintile (World Bank, Citation2016).

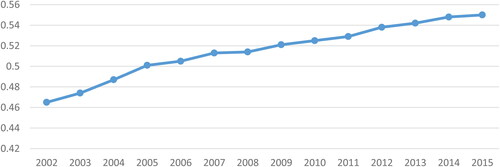

The decline in poverty and improvement in the well-being of the population lying in the lowest income quintile is further substantiated by changes in their consumption patterns and dietary diversity. Food expenditure was reduced with an accompanying substitution with more nutritious foods like chicken, eggs and fish. The World Bank’s HDI lends credence to this claim by showing a consistent rise in the index for Pakistan, commensurate with higher levels of human development effort in education, health, income and inequality ().

The preceding analysis shows that poverty in Pakistan has declined substantially over the past fifteen years, and this decline does not seem to reflect a direct relationship with the growth in GDP, which has been low and bereft with adverse movements. The responsiveness of poverty to a change in GDP growth reveals a relatively inelastic relationship indicating that there are factors, other than growth, contributing to poverty reduction. shows the elasticity of poverty to GDP growth in Pakistan over the years. For example, in 1991, a 1% increase in GDP brought about a 1.02% decline in poverty. (poverty data from World Bank WDI, 1998–2015). From the values for elasticity of poverty to GDP growth, it is evident that there is no discernible relationship between the poverty headcount ratio and GDP growth of Pakistan.

Table 1. Poverty and GDP elasticity.

The paper attempts to explain the reduction in poverty in Pakistan over time. Since 2004, poverty in the country has steadily declined; while Pakistan has experienced some phases of falling poverty in previous years (e.g., 1994–97), these phases have been short-lived and trends in poverty erratic. Even after the switch from a dictatorship to a democracy, the absence of a stable democracy has led to inconsistent growth, which does not correspond to the reduction in poverty during this time. This paper seeks to find a plausible explanation for this relationship with respect to the stability of the democratic system, the inflows of foreign aid and the dissemination of information through media.

3. Literature review: explaining falling poverty without economic growth

3.1. Theoretical literature

The Dependency Theory was first introduced by Raul Prebisch in the 1950s, who was concerned that development in industrialized countries did not lead to growth in poorer countries. This theory attempts to assess the underdevelopment of poorer countries in light of their interaction with richer, more developed nations (Ferraro, Citation2008). Given Pakistan’s dependency on foreign aid (as addressed in Section 3.2) and its poor balance of payments, it is interesting to consider poverty in the country as a result of its dependence in foreign inflows. In recent times however, the dependency theory has faded from mainstream economics as the world has shifted away from colonialism.

Secondly, the theory of Culture of Poverty suggests that poverty is not only a result of macroeconomic factors but also depends on the development of mind-sets and collective values (Grondona, Citation2000). These include religion, employment status, wealth, justice etc. Interestingly, the defining characteristics of a non-development system include censorship and asymmetric information, focus on macroeconomic policies, corruption and poor methods of government appointment (Lindsay, Citation2000). Our focus on free press in democracy will further examine this theory in the context of Pakistan.

3.2. Foreign aid for the poor

The relationship between foreign aid and poverty reduction has been debated to great lengths, with some proposing that foreign aid leads to a vicious circle of low growth and high poverty and others proposing that foreign aid may be used to form a virtuous cycle, where reforms focused on alleviating poverty will result in higher growth, which in turn will mitigate poverty ((Perry et al., Citation2006). There also exists a third school of thought that suggests that examining the channels through which foreign aid affects poverty may provide a clearer picture (Mahembe & Odhiambo, Citation2017). For our paper, we will first assess the channels through which foreign aid assists in poverty alleviation. In Pakistan, foreign aid has predominantly been used to fund cash transfer programs, provide access to basic facilities and encourage microfinance.

Reducing the inequality created by a lack of basic necessities, poverty reduction programs are able to show their effectiveness in the long run, by providing more opportunities to the marginalized poor. Cash transfer programs help alleviate poverty through their impact on human development (Afzal et al., 2019). Rawlings and Rubio (Citation2005) find that providing conditional cash transfers has a positive impact on poverty reduction, by improving their consumption, increasing school enrolment and improving healthcare. Cash transfer programs also found to improve women empowerment, while simultaneously reducing poverty for the beneficiaries (Ambler and de Braw, 2017). Pakistan is host to the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP), which is one of the largest unconditional cash transfer programs in the world and targets the poorest 15% of households in the country (Afzal et al., 2019). In recent years, it has also moved to incorporate a a conditional element to disbursements, contingent upon school attendance and health insurance.

The reduction in poverty is not only achieved just through provision of employment or direct transfers to the poor households, but also through the provision of basic facilities, such as health, education and financial services. Increasing the educational attainment of poorer individuals in the economy by one year can have a varying effect on earnings to as much as 8% (Nasir & Nazli, Citation2000). In the long run, households are able to increase their earnings as their education attainment increases, and thus are able to improve their standard of living, escaping the vicious cycle of poverty (Haq, Citation2005; Abuka et al., Citation2007).

Improvements in access to health facilities are expected to have a similar impact on poverty reduction as well. The health-poverty trap is a vicious cycle because the health of the poor cannot be improved without improving their quality of life, which cannot be achieved without the eradication of poverty (Sala-i-Martin, 2005). Doppelhoffer et al. (2000) find that human capital significantly contributes to the growth of a country, whereas health is empirically found to be the most important factor affecting human capital (Becker & Schultz, Citation1974). It is for these reasons that development projects focus on developing human capital, through education and improved health care, in an effort to eradicate poverty.

3.3. From dictatorship to a stable democracy

Social sector service delivery has been unarguably abysmal in Pakistan in 1980s and 1990s. Despite efforts by successive governments to formulate numerous well-intended policies for the reduction of poverty and increase in the well-being of the people, implementation and attainment of objectives has been extremely limited. Broadly, this failure can be attributed to political instability in the wake of a long military rule in the ’80s, followed by a very unstable democracy in the ’90s. Democracies are evidenced to perform better than non-democracies to produce more public goods and better redistribution of income leading to welfare gains for the poor (Ross, Citation2006). Existing literature also suggests that as democracy takes root in countries, their poverty levels should decline through improved service provision in terms of health, education and social security services ((Pribble et al., Citation2009). However, it is also essential to look beyond the mere label of a democracy and assess the level of engagement between a government and its citizens (Narayan et al., Citation2009). For example, Lewis (Citation2008) illustrates the case of African economies that shifted towards democratic rule in the 1990s but are stuck in “a paradox growth without prosperity”. Another aspect to consider here is the fact that the higher the income inequality, the more likely the country is to move away from democracy (Milanovic, Citation2017). In our empirical analysis, we will also evaluate the direction of causality between poverty reduction and democracy.

3.4. Better information: role of media

The information constraint that low income, less educated voters face is one of the primary causes for lower public service delivery and policy outcomes in terms of targeted benefits that hurt the median voter. Literature shows how this link between equality, particularly in economic terms, and media holds true. Keefer and Khemani (Citation2005) suggest that the poor of a country may be marginalized due to limited access to information, and thus, they may be worse off, in economic and social terms. This incomplete and imperfect information can lead to decisions that may be irrational, such as voting for a politician with a lack of credibility. Furthermore, they explain that due to this imperfect information, the poor may be drawn to vote for individuals who promise personal transfers to a smaller population, compared to broader public services. Thus, without understanding the consequences of their actions, they may make decisions that make them worse off, marginalizing them in the longer term. These findings are confirmed by Ross (Citation2006). Yaser et al. (Citation2011) conducted a study in Lahore, Pakistan that has found that respondents with low income and those with low education do not believe that media has any real impact on their voting decisions and do not get their information about the candidates from televisions.

4. Data and methodology

To investigate the factors affecting poverty reduction in Pakistan, we focus on the role of democracy, media and foreign aid, as well as economic growth. Our data for each variable ranges from 2002–2015; our data timeline is constrained by the fact that the last poverty headcount for Pakistan was published by the World Bank in 2015. Each variable is measured as shown in as follows:

Table 2. Variables and their measures.

Our objective here is to check for cointegration between poverty reduction and economic growth, foreign aid, democracy and free media respectively. Cointegration provides a framework for testing and estimating long-run equilibrium relationships. It implies that in the long run, the pair of variables moves together, even though they may drift apart in the short run. Cointegration does not directly tell us about the causal relationship between the two variables, even though it does indicate Granger causality in at least one direction. In the same vein, a lack of cointegration does not necessarily mean that there is no relationship between two variables at all. It may simply mean that the two series are not integrated as other factors affect the movement of the series. If Granger causality exists in the absence of cointegration, it may be concluded that the two series drift apart due to other factors but there is at least some transmission of signals between the two variables. On the other hand, a lack of Granger causality can also indicate that the signals are being transmitted instantaneously, but given the long-term nature of our variables, this is unlikely.

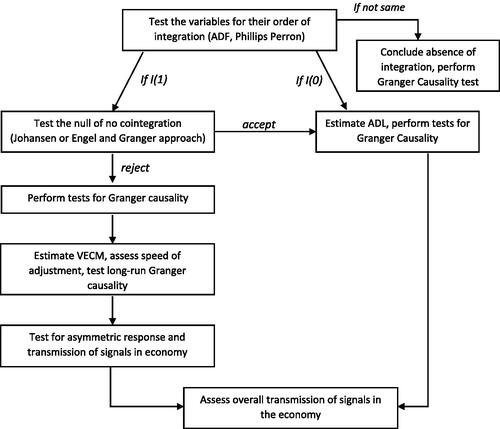

We start by checking each of the variables for stationarity and then check for cointegration between the fall in poverty and each of the stated variables. In case a pair of variables has a different order of integration, we conclude that the two series are not integrated. If the two variables are integrated to the order I(0), we assess the underlying dynamics between them using an Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ADL) model. We run the Vector Autoregression (VAR) framework and test for Granger causality.

In case the pair of variables is integrated to the order I(1), we test the null of cointegration using the Johansen procedure or the Engle Granger model. If the two tests reject the null of no integration, we can conclude that the two series move together and are cointegrated. If the null of no integration is not rejected, we conclude the series are not cointegrated or that we are unable to conclude that transmission of signals between the two series is complete. The diagram below explains the process further ():

Figure 3. Methodology process flow. Source: Rapsomanikis et al. (Citation2006).

Our proposed methodology has previously been used to investigate linkages and causality by various authors (Parveen et al., Citation2020; Chandrashekar et al., Citation2018; Kumari & Sharma, Citation2017). We have used STATA 16 to run all of our models.

5. Results & Discussion

We start by checking each variable for stationarity, using the Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) and the Phillips-Perron Test. The results are presented in :

Table 3. Unit root tests.

The table shows that both the ADF and the Phillips-Perrons test reveal similar results. We can see that poverty reduction, economic growth, free press and foreign aid are stationary and therefore integrated at order I(0)- i.e., economic growth, free press and foreign aid cannot be cointegrated with poverty reduction as they are all integrated to the order I(0). In the next step we perform an ADL model on poverty reduction, economic growth, free press and foreign aid.

On the other hand, democracy is non-stationary; by taking the differenced terms, we are able to determine that democracy is integrated at the order I(1). We conclude that democracy and poverty reduction cannot be cointegrated as they are integrated at different orders; we will only perform Granger Causality test for tese two variables.

We run the ADL model for poverty and economic growth, free press and foreign aid. Using the AIC model, we determine the optimal lag length to be 3 for all 4 variables and run the VAR model and then check for Granger causality. We also look at the relationship between democracy and foreign aid to determine the causality between them. The results are displayed in the following :

Table 4. Granger causality test.

From the results in the table, we see that economic growth does not Granger cause a fall in poverty, which is in line with our reasoning given at the beginning of the paper. Economic growth has been erratic over the years and displays no apparent trend with the fall in poverty in the country.

The results for poverty reduction and democracy are interesting such that a fall in poverty appears to granger cause democracy in the country but democracy does not Granger cause a fall in poverty. It may be argued here that despite being a democracy in name, Pakistan witnessed four regime changes between 1990 to 1999. The politicians at the time focused on providing services that would ensure patronage of the voters (Wilder, Citation1999). The rapid changes in regime meant that the politicians had less time to implement policies that would have long term benefits, so the governments used resources to provide targeted outcomes rather than high quality service which could improve lives of the people in the long term (Easterly, Citation2001). The strengthening of democracy can also be witnessed in the dramatic increase in voter turnout for elections from a mere 35% of the total registered voters casting the vote in 1997, to more than 44% in 2008 elections and 55% in 2013 elections (ECP, Citation2013). This increase reflected the reaction of the people to bad governance and corruption and the need to penalize the ruling party for it. An electoral system developed, which was more likely to provide public goods, by creating competition between political parties to gain voter support. In essence, as the citizens transitioned out of poverty, they exerted their patronage to demand transparency in the democratic processes through which their local representatives were elected. this process has led to reinforcing among the political leadership that welfare projects need to be provided at a large scale and should have the potential for far reaching consequences.

On the other hand, foreign aid and poverty have a bidirectional relationship, where foreign aid Granger causes a fall in poverty in Pakistan and falling poverty granger causes increase in foreign aid flows in the country. Development aid provided by international organizations, including the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, United Nations and USAID, has played an essential role in the alleviation of poverty within Pakistan. In particular, Pakistan’s largest cash transfer program, the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) has benefited from funding from these organisations. BISP has resulted in a decrease of poverty by 7% among its beneficiaries, reducing the poverty gap by about 3% (Oxford Policy Management, Citation2016). Health and education programs are also being focused upon under different development programs, such as the Social Sector Development Program, which established 137 schools between 2004 and 2008, with a majority of their 20,000 students being female (PPAF, Citation2008). The United Nations, USAID and the World bank have all funded education focused projects, by establishing schools, providing low cost education and providing cash stipends as well as scholarships (UN, Citation2016; USAID, Citation2018). Additional initiatives for maternal health and child care reached 7.3 million mothers under the programs designed by UN and 9.8 million under the USAID programs, which have successfully trained 51,000 people (UN, Citation2016; USAID, Citation2018). The UN has also played an important part in in immunization against polio, where polio drives have led to a 93% reduction in cases of polio since 2014 (UN, Citation2016). All of these initiatives have directly and indirectly contributed to poverty reduction in the country.

We also investigate the causality between foreign aid and democracy and observe that democracy granger causes an increase in foreign aid flows. Our data indicates that shifting to democracy has increased foreign aid flows for Pakistan. Prominent international donor agencies such as ADB, World Bank, UN and USAID, have contributed significantly to the economic development of the country and their financial flows have been greatly amplified as Pakistan has transitioned to a democracy. The impact of donations from these organisations cannot be discounted, given the drastic decline in its poverty headcount from 64.3% in 2001–02 to less than 30% in 2013–14.

Next, we see that free press does not cause a Granger cause a fall in poverty and neither has a fall in poverty granger caused freedom of press. The role of media in Pakistan, while more independence over the last decade and a half, is still subject to strict censoring by regulatory authorities. Although press censorship is not formally enforced, journalists may still be indirectly encouraged not to report on sensitive matters (Nadadur, Citation2007). Furthermore, the country enacted the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill (PECB) in 2016, which is vague in its content and grants authorities the power to censor content (Freedom House, Citation2017). Violent protests in 2017 saw all social media websites being blocked for two days in the country, while two men were condemned to death for sharing blasphemous content online (Freedom House, Citation2018). Given that the freedom of media in the country appears to be only surface level, it is not surprising that our results do not indicate that it has any impact on poverty eradication. However, it would be imprudent to simply state there is no existing relationship between poverty reduction, economic growth and free press. It is possible for these variables to be affecting declining poverty through indirect signals.

6. Conclusion

Pakistan has produced phenomenal results in poverty reduction in the last decade and a half whereby headcount poverty has declined by 66% from 2003–2014. This is especially surprising as the economy continues to be bereft with woes of bad governance, worsening global competitiveness and weak institutional structures. The explanation for the fall in poverty can be found in the presence of a relatively stable democratic regime, which led to enhanced social service delivery albeit for political gains. Targeted programs driven by self-interest of electoral candidates, resulted in a steady rise in livelihood of the very poor and a decline in their absolute numbers.

The decline of poverty in a country with steady inflows of foreign aid attest to the fact that Pakistan does not adhere to the dependency theory. Rather, its resources (and aid) are being diverted to the field of health and education, creating long-term improvements in human capital. This also supports the notion that dependency theory may not hold in this era of globalization. In light of the limited freedom of media and the relatively new presence of democracy in the country, it remains to be seen whether Pakistan indeed harbours a “culture of poverty” in certain areas.

The free flow of information through an independent and growing media since 2002 has redefined the performance measures of democratic representatives. The expanding media has made the masses more aware of their rights, and provided a platform to demand these rights for themselves. Access to information has reduced the gap between different strata of the society leading to greater equality in distribution of services. Moreover, the role of multilateral agencies in providing financial and project aid to Pakistan in the last decade has been the cornerstone in efforts of poverty reduction. The World Bank, ADB, and USAID have funded and implemented projects that have made significant impact on the lives of the poor. The funding of targeted programs, growth of microfinance, aid in the agriculture sector to help the rural poor, and assistance in social sector with special focus on education and health have been the focus areas with decent successes for these agencies.

Pakistan is on an appropriate path of poverty alleviation and social sector delivery and the impact of the current programs will show results in the longer term. However, there is still a substantial misdirection of priorities that remain focused more on targeted outcomes and less on more general outcomes like education and health which are more likely to contribute to longer term development and productivity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abuka, C. A., Ego, M. A., Opolot, J., Okello, P. ( (2007). Determinants of poverty vulnerability in Uganda (Discussion Paper No. 203). Institute for International Integration Studies.

- Ambler, K. & de Brauw, A. (2017). The impacts of cash transfers on women’s empowerment: Learning from Pakistan’s BISP Program (No. 113161). The World Bank.

- Becker, G. S., Schultz, T. W. (1974). Economics of the family. The Economics of the Family.

- Chandrashekar, R., Sakthivel, P., Sampath, T., & Chittedi, K. (2018). Macroeconomic variables and stock prices in emerging economies: A panel analysis. Theoretical and Applied Economics, Asociatia Generala A Economistilor Din Romania - AGER, 3, 91–100.

- Doppelhofer, G., Miller, R. I., Sala-i-Martin, X. (2000). Determinants of long-term growth: A Bayesian averaging of classical estimates (BACE) approach (No. w7750). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Easterly, W. (2001). The political economy of growth without development: A case study of Pakistan. World Bank.

- Easterly, W. (2007). Was development assistance a mistake? American Economic Review, 97(2), 328–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.2.328

- Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP). (2013). Report on the General Elections, 2013. Election House. Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://www.ecp.gov.pk/Documents/General%20Elections%202013%20report/Election%20Report%202013%20Volume-I.pdf

- Ferraro, V. (2008). The development economics reader (pp. 58–64). Routledge.

- Freedom House. (2017). Freedom of the Press 2017 - Pakistan. Freedom House. https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1418758.html

- Freedom House. (2018). Freedom of the Press 2018 - Pakistan. Freedom House. https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1418758.html

- Grondona, M. (2000). A cultural typology of economic development. In L. Harrison & S. Huntington (Eds.), Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress (11th ed.). Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Foreign Policy Development.

- Haq, R. (2005). An analysis of poverty at the local level. The Pakistan Development Review, 44(4II), 1093–1109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.30541/v44i4IIpp.1093-1109

- Hoynes, H., Page, M., & Stevens, A. (2006). Poverty in America: Trends and explanations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526102

- Jones, S., & Tarp, F. (2016). Does foreign aid harm political institutions? Journal of Development Economics, 118, 266–281. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.09.004

- Keefer, P., & Khemani, S. (2005). Democracy, public expenditures, and the poor: Understanding political incentives for providing public services. The World Bank Research Observer, 20(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lki002

- Kersting, E., & Kilby, C. (2014). Aid and democracy redux. European Economic Review, 67, 125–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.01.016

- Kono, D. Y., & Montinola, G. (2009). Does foreign aid support autocrats, democrats, or both? The Journal of Politics, 71(2), 704–718. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381609090550

- Kumari, A., & Sharma, A. (2017). Physical & social infrastructure in India & its relationship with economic development. World Development Perspectives, 5, 30–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2017.02.005

- Lewis, P. (2008). Growth without prosperity in Africa. Journal of Democracy, 19(4), 95–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.0.0041

- Lindsay, S. (2000). Culture, mental models, and national prosperity. In L. Harrison & S. Huntington (Eds.), Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress (11th ed.). Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Foreign Policy Development.

- Mahembe, E., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2017). On the link between foreign aid and poverty reduction in developing countries. Revista Galega De Economia, 26(2), 113–128.

- Milanovic, B. (2017). The higher the inequality, the more likely we are to move away from democracy. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/may/02/higher-inequality-move-away-from-democracy-branko-milanovic-big-data

- Morrison, K. (2007). Natural resources, aid, and democratization: A best-case scenario. Public Choice, 131(3–4), 365–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-006-9121-1

- Myhrvold-Hanssen, T. L. (2003). Democracy, news media, and famine prevention: Amartya sen and the bihar famine of 1966–67. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Nadadur, R. (2007). Self-censorship in the Pakistani print media. South Asian Survey, 14(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/097152310701400105

- Narayan, D., Petesch, P., Narayan-Parker, D., Pritchett, L., & Kapoor, S. (2009). Success from the bottom up. World Bank Publications.

- Nasir, Z. M., & Nazli, H. (2000). Education and earnings in Pakistan (Research Report No. 177). Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE).

- Oxford Policy Management. (2016). Benazir income support program final impact evaluation report. Oxford Policy Management. http://bisp.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/BISP_FinalImpactEvaluationReport_FINAL-5.pdf

- Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund (PPAF). (2008). Educating Pakistan's children choices, alternatives and tradeoffs. PPAF. http://www.ppaf.org.pk/doc/HealthandEducation/Educating%20Pakistan's%20Children.pdf

- Parveen, S., Khan, A. Q., & Farooq, S. (2020). The causal nexus of urbanization, industrialization, economic growth and environmental degradation: evidence from Pakistan. Review of Economics and Development Studies, 5(4), 721–730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.26710/reads.v5i4.883

- Perry, G., López, J., & Maloney, W. (2006). Poverty reduction and growth: Virtuous and vicious circles. World Bank.

- Pribble, J., Huber, E., & Stephens, J. (2009). Politics, policies, and poverty in Latin America. Comparative Politics, 41(4), 387–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5129/001041509X12911362972430

- Ranis, G., Stewart, F., & Ramirez, A. (2000). Economic growth and human development. World Development, 28(2), 197–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00131-X

- Rapsomanikis, G., Hallam, D., & Conforti, P. (2006). Market integration and price transmission in selected food and cashcrop markets of developing countries: review and applications. Agricultural Commoditymarkets and Trade, 187–217.

- Rawlings, L. B., & Rubio, G. M. (2005). Evaluating the impact of conditional cash transfer programs. The World Bank Research Observer, 20(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lki001

- Ross, M. (2006). Is democracy good for the poor? American Journal of Political Science, 50(4), 860–874. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00220.x

- Sala-i-Martın, X. (2005). On the health poverty trap. In Health and economic growth: findings and policy implications. The MIT Press.

- Sen, A. (1999). Democracy as a universal value. Journal of Democracy, 10(3), 3–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1999.0055

- Sen, A. (2004). What’s the point of democracy? Presentation, 1878th Stated Meeting, House of the Academy.

- Policy, S. Development Centre. (1997). Review of the social action program. Karachi: SPDC.

- United Nations (UN). (2016). Pakistan one UN programme II. United Nations.

- USAID. (2018). Education. Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://www.usaid.gov/pakistan/education

- Wilder, A. (1999). The Pakistani voter, electoral politics and voting behaviour in the Punjab. Oxford University Press.

- World Bank. (2016). World development indicators 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2020, from https://data.worldbank.org/

- World Bank. (2017). World development indicators 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2020, from https://data.worldbank.org/

- The World Bank Group. (2016). Pakistan development update. World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/935241478612633044/pdf/109961-WP-PUBLIC-disclosed-11-9-16-5-pm-Pakistan-Development-Update-Fall-2016-with-compressed-pics.pdf

- Yaser, N., Mahsud, M., & Chaudhary, I. (2011). Effects of exposure to electronic media political content on voters’ voting behavior. Berkeley Journal of Social Sciences, 1(4), 1–22.

- Younis, F., Chaudhary, A., Akbar, M. (2015). Pattern of development and sustainable economic growth in Pakistan: A descriptive analysis. Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/71473/1/