Abstract

Prior studies on the dark side of the organisation tend to overlook some important mediator(s) in the relationship between the dark triad personalities (D.T.P.s) and counterproductive work behaviour (C.W.B.). Hence, this study examines the multiple-mediation model by incorporating perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability in the relationship between D.T.P.s and C.W.B. The sample of 290 employees is selected through a random sampling technique from the hospitality industry. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (P.L.S.-S.E.M.) and bootstrapping are employed to examine the multiple-mediation model. The results show that perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability mediate the association of the D.T.P.s and C.W.B. Our findings provide policymakers with a vision into the existence of the D.T.P.s and their potential consequences for C.W.B. This study encourages decision-makers and practitioners to develop an ethical climate, job standards, and systems of accountability to achieve productive goals.

JEL CODES:

1. Introduction

Have you ever noticed that colleagues or subordinates deliberately taking long intervals that are more than permissible? Have you ever felt that people of your organisation intentionally misbehaving with coworkers and violating the rules and regulations? These questions give a strong motive to investigate scientifically, why is this happening? Because such work behaviours can harm workers and their organisations in some unexpected ways. The ‘Dark side’ of employees’ behaviour has been recognised as an important component in the recent decade, and a growing body of research is directed toward comprehending these behaviours (Cohen, Citation2016). According to Vardi and Weitz, (Citation2003), counterproductive work behaviours (C.W.B.s) are linked with the dark side of organisational behaviour. C.W.B.s are known as ‘voluntary acts that violate significant organisational norms and are contrary to the organisation’s legitimate interests’ (Sackett, Citation2002). C.W.B. is a devastating act for organisations and their members. It ranges from minor offences to more serious crimes (Czarnota-Bojarska, Citation2015). Several studies provide evidence that C.W.B. is an enduring problem in the organisation. For instance, Dischner (Citation2015) reports that 75% to 95% of all employees are found guilty of activities like fraud and theft. Similarly, business organisations have to tolerate about $2.9 trillion annually due to fraudulent events, and about $3 billion due to the tardiness of employees. Thus, it is obvious that C.W.B. creates financial and nonfinancial losses for organisations.

A brief review of several studies gives evidence that various attempts have been made to investigate possible determinants of C.W.B.s, but much is still unknown. Mostly, prior studies examine the situational or environmental factors related to C.W.B. For example, the study of Karim et al. (Citation2013) show that anger influences aggressive C.W.Bs. Schwager et al. (Citation2016) conduct hierarchical regression analyses and report a negative association between honesty-humility with C.W.B. and mindfulness. Bai et al. (Citation2016) reveal that family incivility negatively influences deviant behaviour. In the same way, considerable research shows personality traits are important determinants of C.W.B.s. For instance, Kozako et al. (Citation2013) relate extraversion and agreeableness with C.W.B.s. The study of Berry et al. (Citation2012) examines the effect of the big five traits of personality on C.W.B. Recently, Smith and Lilienfeld (Citation2013) posit that the dark triad personalities (D.T.P.s) could influence C.W.B.s as major determinants. The term D.T.P. was introduced by Paulhus and Williams (Citation2002) for three traits, i.e. narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism.

Although the previous studies have given special attention to examining the possible consequences of the D.T.P.s for the organisation; this area of research deserves more attention (Palmer et al., Citation2017). In this vein, Ying and Cohen (Citation2018) found the mediating roles of environmental factors such as organisational commitment and organisational justice in the nexus between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B. while they could not find the mediating role of psychological contract breach between D.T.P. and C.W.B. Baka (Citation2018) investigated the moderating role of job control and social support between D.T.P. and C.W.B. Moreover, Palmer et al. (Citation2017) reveal that D.T.P.s are engaged in various types of C.W.B.s. Furthermore, the recent meta-analysis of Muris et al. (Citation2017) concludes that the D.T.P.s are dominant predictors of different kinds of C.W.B.s. However, the overall effect size for the D.T.P. and C.W.B. is found remarkably weak. Baka (Citation2019) investigated the moderating role of D.T.P. and job control between bullying and C.W.B. Palmer (Citation2016) could not find any substantial effect of ethical leadership on the relationship between D.T.P. and C.W.B.

The findings of the studies mentioned above show inconsistent results regarding the nexus between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B. The mutual consensus still needs to settle between D.T.P.s and C.W.B. It might be due to the reason that prior studies may have overlooked some essential mediators within the nexus of D.T.P.–C.W.B. In other words, it can be assumed that the relationship between D.T.P. and C.W.B. could be more indirect – through other organisational variables – than direct. Schyns (Citation2015) emphasises that further research is necessary to comprehend the nexus of the D.T.P.s and C.W.B.s.

Given the above motivation and consistent with (Cohen, Citation2016), this study fills the gap by examining the mediating roles of perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability in the relationship between D.T.P.s and C.W.B.s. Perceived organisational politics is expected to mediate the relationship because it is an intoxicating reality at the workplace. Moreover, it increases the element of self-interest in the workforce. Personalities high on the D.T.P.s are influenced, more than any others, to perceive the political signs at their workplace. When they perceive their work environment as uncertain, unfair, and open to exploitation, they tend to behave in a worse manner (Baloch et al., Citation2017). Consequently, we hypothesise that perceived organisational politics plays a mediating role between the D.T.P. and C.W.B.

Moreover, consistent with the literature (Cohen, Citation2016), we aim to examine the mediating role of perceived accountability in the relationship between the D.T.P. and C.W.B. Perceived accountability is defined as being answerable to the audience for performing up to certain prescribed standards (Schlenker et al., Citation1994). D.T.P.s prefer to operate in the dark because they avoid being answerable or accountable. The fear of being accountable makes D.T.P. less likely to engage in C.W.B.s. Therefore, it is expected that perceived accountability is also a potential mediating factor between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B.

Thus, this study extends the existing literature in the following ways. First, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is a unique inquiry to investigate the multiple-mediation model by considering perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability as potential mediators between D.T.P.s and C.W.B. The only study conducted by Baloch et al. (Citation2017), who investigated the moderated-mediation model in the nexus between D.T.P.s and C.W.B.s. Unlike previous studies, we have employed a multiple-mediation model to examine whether the effect of D.T.P.s is more indirect or not. Besides, this study has compared the strengths of specific mediating effects to determine which mediating effect is stronger than the other. Second, we have adopted an advanced technique introduced by Carrión et al. (Citation2017) to test the multiple-mediation model. This method provides a comprehensive picture regarding indirect effects. It not only determines the power and scope of the indirect effect but also offer the significance of the indirect effect by using the bootstrapping method. Though, the previous testing regarding the mediation analysis was based on the Sobel (Citation1982) test, which can lead to inaccurate outcomes. For example, the Sobel test adopts a normal distribution that is not, although, reliable with the nonparametric partial least squares structural equation modelling (P.L.S.-S.E.M.) method. Furthermore, the Sobel test entails non-standardised path coefficients as an input for testing the statistic and low statistical power, especially when the sample size is not very large. Consequently, research discourages the Sobel test for mediating analysis, particularly in P.L.S.-S.E.M. (Hair et al., Citation2016). Along these lines, we believe that the acknowledgment of present-day forms in P.L.S.-S.E.M. would give increasingly exact outcomes.

The rest of the study designed as Section 2 explains the conceptual framework with hypotheses development, Section 3 depicts methodology, Section 4 reports analysis and results, and Section 5 covers discussion, limitations, and future directions of the study.

2. Conceptual framework and hypotheses development

2.1. The dark triad

D.T.P. is a combination of three traits, i.e., narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism. The trait of psychopathy relates to an individual who is impulsive, highly aggressive, tolerant of danger, and scores low on empathy (Patrick et al., Citation2009). While narcissism is explained with the word self-importance, lack of responsiveness, and immense desire for appreciation (Grijalva & Newman, Citation2015). Machiavellian-type personalities believe in manipulating others. They have a cynical view of human nature and put expediency above moral values (Spurk, Keller, & Hirschi, Citation2016).

2.2. The dark triad personalities and counterproductive work behaviours

Evidence found from previous literature proclaims that those pretending to be high on the dark triad (D.T.) construct tends to involve more in C.W.B. (O’Boyle et al., Citation2012). For example, psychopaths harm others to fulfill their agenda. The act of harming may be a way of psychopaths to divert others’ attention from their task (Boddy, Citation2006). Similarly, narcissism is categorised by extreme self-love, self-exaggeration, and attention seeking. These personalities use manipulative tactics when they are involved in relationships with others. High self-esteem is more vulnerable to ego-threat as opposed to low self-esteem. Therefore, people with high egos are more inclined to anger and aggression. While, Machiavellianism is associated with emotionless and unscrupulous manners along with dishonesty and insensitivity (Campbell et al., Citation2009). Personalities high on Machiavellianism have an immense desire to fulfill self-interest and want to gain control over others. Machiavellianism is also associated with many transgressed behaviours, including a tendency to exploit others, commit fraud and anti-social behaviour (Moore et al., Citation2012). Wu and Lebreton (Citation2011) indicate that Machiavellian-type personalities can be engaged in any immoral and unethical acts for the achievement of their goals even though it may go against convention.

Based on the social exchange perspective, it is believed that D.T.P.s are associated with C.W.B. O’Boyle et al. (Citation2012) indicated a positive relationship between D.T.P. and C.W.B.s. However, the relationship obtained for psychopathy was found relatively small; a reasonable relationship was found for Machiavellianism, and unexpectedly a strong positive association was observed for narcissism with C.W.B.s. Whereas, in another meta-analysis, a weak association was found between narcissism and C.W.B. (Grijalva & Newman, Citation2015). Additionally, Baughman et al. (Citation2012) studied adults and revealed the D.T.P.s as a strong predictor of bullying behaviour.

From the above arguments and existing literature, the following hypotheses have been proposed:

H1-a: Psychopathy has an optimistic association with C.W.B.

H1-a: Narcissism has an optimistic association with C.W.B.

H1-a: Machiavellianism has an optimistic association with C.W.B.

2.3. The mediating role of perceived organisational politics in the relationship between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B

The framework presented by Ferris et al. (Citation1989) gives the basis for the mediating role of perceived organisational politics in the connection between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B. The framework advocates that there can be various predictors and outcome variables that are supposed to inspire and to be influenced by perceived organisational politics. The concept of perceived organisational politics gets much attention after the development of the scale introduced by (Kacmar & Ferris, Citation1991). However, perceived organisational politics is defined by Ferris et al. (Citation1989) as ‘an individual’s subjective evaluation of the level to which the work environment is categorised by colleagues and superiors who exhibit self-serving behaviours’. Buenger et al. (Citation2007) discussed that D.T.P.s are inclined to understand actions and proceedings in political terms because exploitation and deviousness are innate features of those high on the D.T. construct. Moreover, Yang (Citation2017) argues that D.T.P.s can sense politics in their work environment more than others. They have the ability to assess, manipulate, and exploit the political environment to achieve their personal goals.

As for the connection between perceived organisational politics and C.W.B., the findings of several studies show that perceived organisational politics is linked with employees’ adverse behaviour. For example, Colbert et al. (Citation2004) postulate the perceived organisational politics creates an unfavourable situation for an organisation which leads employees to exhibit negative behaviour like C.W.B. Similar facts highlighted by Rosen and Levy (Citation2013) that perceived organisational politics provokes negative performance from employees. Kacmar et al. (Citation2013) argue that perceived organisational politics has an adverse association with serving and promotability. A recent study by Cohen and Diamant (Citation2019) also indicates that perceived organisational politics stimulates C.W.B.

To summarise, it is reasonable to claim that the way D.T.P.s look at their environment is different from others. When they perceive their environment is political and open for misuse, they are most likely to behave in a toxic way. By using existing literature and the above arguments, we made some hypotheses, which are as follows

H2-a: The association between psychopathy and C.W.B. is mediated by perceived organisational politics.

H2-b: The association between narcissism and C.W.B. is mediated by perceived organisational politics.

H2-c: The association between Machiavellianism and C.W.B. is mediated by perceived organisational politics.

2.4. The mediating role of perceived accountability in the association between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B

Accountability is an essential element for the efficient execution of an organisation’s operation (Hochwarter et al., Citation2005). Accountability is ‘being responsible to answer audience for performance up to certain approved standards, thereby satisfying obligations, duties, expectations, and other charges’ (Schlenker et al., Citation1994). According to Tetlock (Citation1992), individuals respond to their responsibilities in ways that maintain their position and public image. They observe the workplace for clues about performances and results that are appropriated by those to whom they must be accountable. Therefore, in the absence of accountability; it would be difficult to sustain the social system within the organisation. Mero et al. (Citation2014) are convinced that accountability is an effective way of controlling individuals’ behaviour and related outcomes. Moreover, accountability impacts on behaviour and decisions of individuals. Boddy (Citation2010) argues that a sound control system and public scrutiny, a standard approach in the public sector, may act as a barrier for the D.T.P.s in the organisation. Empirical studies have revealed that perceived accountability is an integral part of ethical behaviour (Steinbauer et al., Citation2014).

D.T.P.s are more sensitive to conventional norms and behaviour. The presence of job standards and accountability to accomplish the task are likely to mitigate deviant behaviour (Martin et al., Citation2010). D.T.P.s behave consistently with environmental cues, and positively succeed the impression of others and thus adjust their self-interest. Usually, D.T.P.s have a low sense of responsibility, however, as a result of social distinctions of the structural context, they observe a high level of accountability (Cohen, Citation2016). The perception of the high degree of accountability alerts D.T.P.s to refrain from possible C.W.B. because they consider that it might put them in a vulnerable situation.

According to existing literature and the above arguments, it is expected that when the D.T.P.s observe themselves as responsible for a performance or a consequence, they are unlikely to be involved in C.W.B.

Thus, the study proposes the following hypotheses

H3-(a): The relationship between psychopathy and C.W.B. is mediated by perceived accountability.

H3-(b): The relationship between narcissism and C.W.B. is mediated by perceived accountability.

H3-(c): The relationship between Machiavellianism and C.W.B. is mediated by perceived accountability.

2.5. Multiple mediations model

To analyse the possible mediations between D.T.P.s and C.W.B., we rely on the multiple-mediations model. The multiple-mediations model is a situation when an exogenous (independent) variable effects on endogenous (dependent) variable through more than one mediating variable. This scenario demands multiple mediation analyses (Hair et al., Citation2016). Many scholars may apply a simple mediation model, one for each proposed mediator. Nevertheless, Preacher and Hayes (Citation2008) argue that this approach may provide biased results due to two reasons. First, obtaining total effect by simply adding up indirect effects from simple mediations is not recommended, as mediating variables in the model would be correlated. Therefore, the indirect estimates derived from several simple mediation analyses will not be reliable and not the actual total indirect effect of multiple mediators. Second, confidence interval and hypothesis tests used to calculate specific indirect may lead to producing incorrect estimates due to the absence of potentially important mediators.

Given the above motivation, taking perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability as potential mediators in the nexus between D.T.P. and C.W.B. is a suitable case to run the multiple-mediations model. As noted earlier, perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability assume to mediate the relationship between D.T.P. and C.W.B. Perceptions held by D.T.P.s regarding the level of politics and accountability at the workplace prompt workers to either focus on self-interest or organisational interest. Thus, we believe that taking both potential mediating variables into the multiple-mediation model enables us to determine unbiased and reliable estimates.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection and sample

A questionnaire survey was used to collect data. Data collected through a random sampling technique from the hospitality employees of China. The hospitality sector has been selected because C.W.B. is prevalent in this sector and not frequently investigated. Whereas, most research conducted on this issue is based on North American samples (Cohen & Diamant, Citation2019). Jung and Yoon (Citation2012) highlighted that C.W.B. extensively present among hospitality workers and there is room to study the reasons that account for such divergent behaviours. Zhao et al. (Citation2013) suggest that C.W.B. is common in the hospitality sector and needs further investigation by scholars. Moreover, Ariza-Montes et al. (Citation2017) argue that C.W.B. among hospitality employees may decline the organisation’s reputation among customers and there is an immense need to address this mounting problem. Therefore, this research is appropriate and the hospitality employees are the right respondents to analyse the multiple-mediation model. This would help scholars and practitioners to recognise characters and organisational environments that may favour divergent behaviours such as C.W.B.

The research team approached the H.R. departments of these organisations for permission. A letter containing all the necessary information regarding the objective of the study, confidentiality, and voluntary participation was submitted to the respective H.R. departments. The organisations’ H.R. departments granted permission and allowed research team members to have direct contact with their employees. They also announced the commencement of the study and assured the confidentiality and voluntary participation of all employees. More importantly, they confirmed to employees that their responses would not be disclosed to their managers or organisation.

The questionnaires’ data were collected from individual sources and via self-report measures. One can criticise that respondents may underreport the extent they were engaged in C.W.B. and may hide the characteristic of their personalities. To reduce the prospective issue of common method bias, the study followed the guidelines of (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Firstly, the research team explained the main objective of the survey and guaranteed the privacy of the respondents. They also clarified that there were no specified answers considering right or wrong and they can express their answer based on impartiality. Secondly, we collected data with a time lag of two weeks. Overall 370 questionnaires were circulated to hospitality employees in the first stage of the study (Time 1). In the second stage of the study (Time 2), we retrieved 301 questionnaires. After scrutiny, we eliminated 11 questionnaires due to insufficient information and selected 290 for data analysis, resulting in an 81.3% response rate.

The study has also checked the possible common method variance with Harman’s single-factor test. Following this approach, the common method variance is always present if the majority of covariance is caused by a single factor in dependent and independent variables. According to Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003), there is no single factor that affects more than 50% of the covariance. So common method bias does not create any problem in our study.

A combined technique in the translation process has been applied in line with (Cha et al., Citation2007). First, a multi-lingual expert decoded the survey from the original language to the targeted language and then another bilingual specialist again converted it back into the original language for comparison. After a rigorous discussion, bilingual experts removed any discrepancies and errors and confirmed that the questions are understood and clear. Finally, the bilingual experts’ panel approved the study questionnaire in the Mandarin language.

The participants included 130 males (45%) and 160 females (55%). One hundred and fifty-three (53%) respondents were between the ages of 18 and 30, 116 (40%) respondents were between the age of 31 and 40 years, and the remaining respondents were older than 40. Two hundred and sixty (90%) respondents received a university education. Regarding employment tenure, 203 (70%) respondents had five or less years’ experience, and the rest had more than five years of job tenure.

3.2. Variable’s measurement

This study adapts validated and tested scales from previous studies. All scales consist of the 5-point Likert scale, the available response options ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree. As far as D.T.P.s are concerned, the present study adapts the Dirty Dozen (D.D.) 12-items scale from the enormous work of Jonason and Webster (Citation2010). For perceived organisational politics, the study adapts the 6-items scale which reflects the general political behaviour from the study of Kacmar and Ferris (Citation1991). As mentioned by Abbas et al. (Citation2014), general political behaviour is considered as a dominant and demonstrative breadth of political behaviour and has appeared in various studies to quantify perceived organisational politics (e.g., Naseer et al., Citation2016). Therefore, we also focus our analysis on general political behaviour for avoiding complications and confusion associated with the dimensional analysis. A sample item for perceived organisational politics (α = .86) is ‘One group always gets their way.’ We adapt the 3-items scale created by Mero et al. (Citation2014) to measure perceived accountability. The scale of perceived accountability has been employed in previous studies (e.g., Guidice et al., Citation2016). A sample item for perceived accountability (α = .83) is ‘I am required to justify or explain my performance regarding achieving the task.’ Finally, C.W.B.s (α = 0.92) are measured by an 8-items scale developed by Dalal et al. (Citation2009) and have been used in the Chinese context (Bai et al., Citation2016). Participants were asked to respond how often they involved in each of the listed behavior using a 5-point scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

3.3. Data analysis

This section is segregated into two steps. The first step confirms the reliability and validity of the model of the study. The second step evaluates the structural model. This arrangement confirms the validity and reliability of the construct before attempting to conclude the association between constructs. This study addresses the measurement model and establishes the validity of the construct. The study executes a confirmatory factor analysis to eliminate those questions which either have low factor loading or cross-load strongly with another construct. This study employs P.L.S.-S.E.M. to test the relationship concerning constructs. The choice of using P.L.S.-S.E.M. because for the following reasons. First, it has higher levels of statistical power and stronger with fewer identification issues in contrast to C.B.-S.E.M. Second, it is suitable for the current study because the objective of the survey is to predict key ‘driver’ constructs. Third, the model of the research is complex in the hypothesised associations (multiple-mediation), and P.L.S.-S.E.M. is considered a suitable method on behalf of a sophisticated model. Fourth, P.L.S.-S.E.M. is a befitted approach for this study, because this study uses latent variable scores in succeeding analyses (Hair et al., Citation2011; Hair et al., Citation2016). Finally, P.L.S.-S.E.M. is appropriate when the measurement model has few indicators (<6), as in this study most of the constructs have indicators (<6) (Hair et al., Citation2017).

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the measurement model

This study is constructed on a reflective model, as the indicators linked with a specific construct are correlated. Furthermore, reducing an indicator does not change the connotation of the construct (Henseler, Citation2017). First, shows that the measurement model supports all the prerequisites for the fitness of the model. All outer loadings are above the acceptable level, which is 0.7. Secondly, the value of composite reliability (C.R.) varies between 0–1. The standard value of more than 0.70 indicates reliability (). Third, average variance extracted (A.V.E.) is a standard measure to ensure convergent validity. Values of 0.5 or above regarded as acceptable (). Consequently, no problem of convergent validity presents among variables.

Table 1. Measurement model.

Following the recommendations of Hair et al. (Citation2016), the study employs heterotrait-monotrait (H.T.M.T.) and Fornell- Larcker benchmarks to measure validity. The findings shown in confirm the validity of the study since the Fornell-Larker standard (A.V.E.) is higher than off-diagonal and H.T.M.T. estimates are well below the threshold of 0.90 (Baloch et al., Citation2018).

Table 2. Measurement model. Discriminant validity.

4.2. Estimation of the structural model

The study follows the five-step procedure to evaluate the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2016): (1) Assess the structural model for collinearity issues; (2) determine the significance of relevance of the structural model relationship; (3) Assess the level of R2; (4) Assess the f2; and (5) Assess the predictive relevance Q2.

First, the present study examines each set of predictors in the structural model for collinearity. Each predictor construct’s tolerance (V.I.F.) value is lower than 5 as shown in . The results confirm that collinearity is not a problem among predictor constructs in the structural model. Second, this study uses a bootstrapping technique with the help of 5,000 randomly drawn samples with replacement at 0.05% level of significance (Hair et al., Citation2016). Also, Henseler et al. (Citation2009) mention that the implementation of bootstrapping provides standard errors and also calculates the bias-corrected bootstrapping confidence intervals of standardised regression coefficients. The study examines the magnitude and signs of path coefficients. summarises the results of path coefficients and also shows the percentile bootstrap at a 95% confidence interval. Thirdly, the values of R2 for perceived organisational politics (0.548), perceived accountability (0.389), and C.W.B. (0.821) are medium, small, and substantial, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2016). Fourthly, the study measures the f2 effect size. The value of f2 indicates the effect of an exogenous latent variable on an endogenous variable which is 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 for small, medium, and large effect, respectively, as shown in (Limayem et al., Citation2001). presents that the structural model has adequate predictive significance for the endogenous construct, as Q2 values are larger than zero.

Table 3. Effects on endogenous variables.

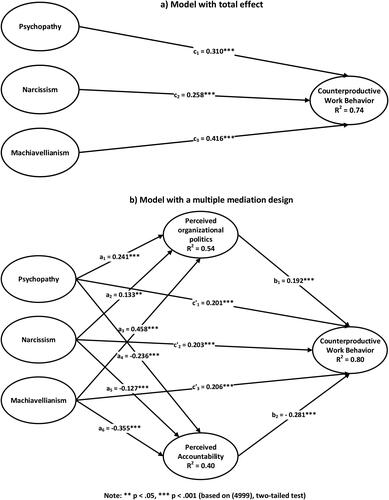

Turning to hypotheses testing, as expected, the study detects a positive and significant path between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B. and show the total effect (c1, c2, and c3) of D.T.P.s on C.W.B. In this scenario, H1-a, H1-b, and H1-c are accepted, which confirms the relationship between the D.T.P.s (i.e. psychopathy, narcissism, Machiavellianism) and C.W.B. (c1= 0.310; t = 8.776, c2 = 0.258; t = 6.446 and c3 = 0.416; t = 8.813 respectively).

Table 4. Summary of mediating effect tests.

For mediation analysis, consistent with recent literature (Baloch et al., Citation2019; Picón et al., Citation2014), the present study follows the latest methodological approach of Nitzl et al. (Citation2016) and Carrión et al. (Citation2017), to test the multiple mediations using P.L.S. This method has obvious advantages over traditional methods. The use of this method allows us to carry out a thorough investigation of the indirect effect regarding its strength and scope. First, the study checks the direct effects of independent variables to mediations and mediations to the dependent variable as reported in . Results reveal the direct effects of the D.T.P.s to perceived organisational politics (a1, a2, a3) and perceived accountability (a4, a5, a6), and from perceived organisational politics (b1) and perceived accountability (b2) to C.W.B. are significant. It fulfills the condition to check the presence of indirect influence. In the next phase, the present study utilises the non-parametric bootstrapping method to investigate the significance of the mediators (Hair et al., Citation2014; Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). The 95% confidence intervals were produced by 5,000 resamples for the mediators. As and present that psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism have significant total effect on C.W.B. (c1= 0.310; t = 8.776, c2 = 0.258; t = 6.446 and c3 = 0.416; t = 8.813 respectively). Consequently, by calculating the mediators (), D.T.P.s reduce their effect, however, maintain a major direct impact on C.W.B. (H1-a: c’1 = 0.201; t = 4.803, H1-b: c’2 = 0.203; t = 4.675 and H3-c: c’3 = 0.206; t = 3.929) respectively. As shown in , the confidence interval of the mediation effect (Product) does not include ‘0’ (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). Thus, these results support (H2-a, H2-b, H2-c) and (H3-a, H3-b, H3-c). These findings mean that both indirect impacts of D.T.P.s on C.W.B. in the research model are significant. represents the total effect of D.T.P.s on C.W.B. as the total of the direct (c’1, c’2 and c’3) and indirect effects (a1b1 + a4b2, a2b1 + a5b2, a3b1 + a6b2).

In the third step, we estimate the type and magnitude of mediation. In present situation both the direct effects (c’1, c’2, c’3) and the indirect effects (a1b1, a2b1, a3b1, a4b2, a5b2, and a6b2) are significant and products of (a1b1 c’1, a2b1 c’2, a3b1 c’3, a4b2 c’1, a5b2 c’2, and a6b2 c’3) are positive. This situation indicates that perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability are complementary mediators between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B. Complementary mediation is a type of partial mediation (Nitzl et al., Citation2016). It means a portion of the effects of the D.T.P.s are mediated through perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability, whereas all three traits cover a part of C.W.B. Also, the study calculates Variance Accounted For (V.A.F.) to calculate the strength of partial mediation. The rule of thumb for V.A.F. suggests that VAF < 20% = no mediation, VAF > 20% but <80% = partial mediation, and VAF > 80% = full mediation () (Nitzl et al., Citation2016).

Finally, the study goes further to compare the mediating effects. We are interested in testing whether the perceived organisational politics has a stronger mediator effect than perceived accountability. For this purpose, following the guidelines of Carrión et al. (Citation2017), this study estimates the difference between (a1b1 and a4b2), (a2b1 and a5b2), and (a3b1 and a6b2). Furthermore, the study calculates the percentile and bias-corrected confidence interval. As presented in , there is not a differential impact between (M1 and M4), (M2 and M5), and (M3 and M6) since both confidence intervals in all three cases contain the zero value. Therefore, we cannot claim that perceived organisational politics has a strong mediator effect than perceived accountability and vice versa

Table 5. Comparison of mediating effects.

5. Discussion

In recent decades, the dark side of the organisation gets greater attention along with the bright side. According to this, the C.W.B. has reinforced interest in the literature of the organisations’ dark side. A subject that has been overlooked for so many years, the recent wave of research has started to develop a fundamental understanding of this significant phenomenon. The present research contributes to the prior literature related to the dark side of organisational research to analyse the nexus of D.T.P.s and C.W.B.s with greater depth. Previous literature showed different outcomes regarding the impact of the D.T.P.s on C.W.B. As far as the present study is concerned, we have taken the D.T.P.s at the beginning of the process, as an important antecedent of C.W.B. However, the perceived accountability and perceived organisational politics play mediating roles between the two variables that is D.T.P. and C.W.B. The outcome of this study based on the general understanding of the C.W.B.s concept and also showed its results particularly on hospitality employees. Firstly, the results of the study showed that there is a direct link between D.T.P.s and C.W.B.s, which is not explained clearly in the prior literature. Secondly, this study found perceived organisational politics mediates the relationship between D.T.P.s and C.W.B. In other words, we can infer that the D.T.P.s have an impact on the events and actions related to political terms. The reason is that exploitation and opportunism are the main features of D.T.P.s (Buenger et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, it shows that when D.T.P.s consider their environment is political, the norms and rules are unwritten, and rewards are dependent on the influence, they are more likely to engage in C.W.B.s. Another possible interpretation of the mediating role of perceived organisational politics is this, that once the D.T.P.s start believing that there are some undefined rules in their organisations, decisions are politically influenced, and performance standards are not based on merit, they are more likely to exhibit C.W.B.s. As explained by Cohen and Diamant (Citation2019), perceived organisational politics change the belief of employees toward organisational justice and a fair system. The moment when they lose their faith in the organisational processes, it manifolds the chances of C.W.B.s at the workplace. Our results coincide with the findings of (Baloch et al., Citation2017; Cohen & Diamant, Citation2019; Meisler et al., Citation2019). It represents that a high level of perceived organisational politics among D.T.P.s are more likely to turn into C.W.B.

The mediating role of perceived accountability shows interesting results between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B. The results are consistent with the notion that when D.T.P.s perceive high accountability at the workplace, they less likely to engage in the C.W.B.s. This outcome coincides with the findings of Hall (Citation2005) who proclaims that the absence of accountability will set the stage D.T.P.s to involve in illegal or C.W.B.s. In other words, the perception of high accountability will lead to control the self-interest behaviour in the organisation. Another plausible reason could be that high accountability may be due to the organisational controls such as written job procedures and effective control systems. As explained by Cohen (Citation2016), D.T.P.s are always alert from such preventive measures and less likely to perform actions like C.W.B.s. Another possible interpretation of these findings could be that D.T.P.s prefer working in the dark, where they cannot be traced or blamed. In this vein, productivity targets, and accountability to meet these targets are important contextual components. When D.T.P.s are exposed to the behaviour and the content it communicates, they feel greater accountability due to the content-related behaviour and may less likely to engage in C.W.B. These results also reinforce the theoretical position of Cohen (Citation2016) who claimed that perceptions of high accountability lead to control self-interested behaviour among D.T.P.s. However, the findings are inconsistent with the results of Ying and Cohen (Citation2018) in the case of Chinese physicians. We believe that this contradiction with the current study is because the dataset employed in this study from a different sector and we have utilised the latest method to analyse the results.

In the nutshell, the results showed that the perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability are important mediating variables in the nexus between D.T.P.s and C.W.B. Perceived accountability is represented itself as the most important predator of the C.W.B.s; 20.77% of its explained variance (R2 = 0.801) and perceived organisational politics (), the direct influence of the D.T.P.s on C.W.B.s is of little significance (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, Citation2012).

5.1. Practical implications

The results of this research show some important practical implications. It is also clearly proved in this research that the D.T.P.s perceive their environment in different aspects as compared to others. When they observe that their environment is facilitating politics and exploitation, they behave in a worse manner. Regular training is considered a useful tool to handle such kinds of situations (Yin et al., Citation2017). The recruitment process is playing an important role in finding out the D.T.P.s. Here it is important to mention that it does not mean to eliminate those who are high on the D.T. construct. Rather, organisations can use different methods like questionnaires and scenario simulation to find out and determine the personality traits so that the managers use their talents effectively and efficiently. The finding of the present study suggests that D.T.P.s affect the decision-making process and their behaviour result. In this regard, the managers should ask and notice the employees or workers about their activities and their progress towards the completion of the tasks. As explained by Mero et al. (Citation2014), if managers monitor employees then their perceived accountability will be increased. A high level of perceived accountability can be achieved among D.T.P.s by the appropriate job standards, the achievement of productivity goals, and the efficiency of the control system (Martin et al., Citation2010). It is also necessary for managers and people who make policies to develop clear and transparent criteria for evaluation because a criterion that is not clear and unfair will affect the behaviour of employees (Chiaburu et al., Citation2013).

5.1.1. Limitations and further research

This study is not without limitations. The present study is about the investigation of perceived organisational politics and perceived responsibility which plays the role of mediators among the D.T.P.s and C.W.B. However, Stone-Romero and Rosopa (Citation2008) argue that authors should not claim that the studied model is the only model consistent with the results when they use S.E.M. in the non-experimental study. Therefore, consistent with the suggestions of Stone-Romero and Rosopa (Citation2008), we do not claim that it is the only model consistent with the results and there can be other causal models also consistent with the same pattern of covariance. An interesting future direction may be to investigate other potential mediation factors in the relationship between the D.T.P.s and C.W.B., and may employ quasi-experimental or two randomised experimental study designs that may explore causal effect between these constructs. Second, the present research has used D.D. scale established by Jonason and Webster (Citation2010) to calculate the D.T.P.s. As stated by Czarna et al. (Citation2016), short measures linked to the D.T.P.s have advantages and disadvantages. The demerit of utilising short measures is, it may not cover the comprehensive characteristics of construct. However, on the other hand, they are useful in eliminating irrelevant items. Thus, it is suggested to utilise other comprehensive scales in future research. Third, there may be some inter-correlations among the few constructs indicating the potential multicollinearity.

However, the outcomes of VIF and comparatively large sample size reduce such possibilities. Fourthly, the present research has only taken adverse outcomes related to political behaviour into account. As noted by Kapoutsis and Thanos (Citation2016), some optimistic results have been written in the previous studies and are open for future investigation, such as greater productivity, career expansion, greater invention, and decision-making consensus. In the end, this study mainly focuses on the hospitality sector and the culture of China. Therefore, other researchers should consciously generalise the results of this study to other cultures. There is scope for future researches to focus on different cultures while investigating this proposed model towards other cultural and organisational setups i.e. education, healthcare, and manufacturing sectors.

6. Conclusion

The published research on the dark side of the organisation has overlooked important mediating factors in the nexus between D.T.P. and C.W.B.s. This research takes a robust and needed approach, i.e., multiple-mediation model to investigate the mediating roles of perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability in the nexus between D.T.P.s and C.W.B. The existence of indirect relationships between D.T.P.s and C.W.B.s through perceived organisational politics and perceived accountability has empirical support. D.T.P.s who perceive their work environment is political and easy to manipulate, they are more likely to engage in C.W.B.s. Whereas, perception of high accountability among D.T.P.s leads to conclude that the risk of being caught is high therefore it would be better to refrain from C.W.B.s. It means by controlling organisational politics and placing organisational controls that increase accountability among D.T.P.s, will lead to reducing C.W.B. It is the authors’ earnest hope that future research expands this rich topic on other sectors and cultures by incorporating other potential mediating and moderating factors in the relationship between D.T.P.s and C.W.B.s.

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to the editor and anonymous reviewers whose constructive comments and suggestions improve the quality and presentation of the manuscript. The authors extend his appreciation to the Research Center, College of Business Administration and the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University for funding this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abbas, M., Raja, U., Darr, W., & Bouckenooghe, D. (2014). Combined effects of perceived politics and psychological capital on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and performance. Journal of Management, 40(7), 1813–1830. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312455243

- Ariza-Montes, A., Arjona-Fuentes, J. M., Law, R., & Han, H. (2017). Incidence of workplace bullying among hospitality employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(4), 1116–1132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2015-0471

- Bai, Q., Lin, W., & Wang, L. (2016). Family incivility and counterproductive work behavior: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and emotional regulation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 11–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.014

- Baka, Ł. (2018). When do the 'dark personalities' become less counterproductive? The moderating role of job control and social support. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics: JOSE, 24(4), 557–569. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2018.1463670

- Baka, Ł. (2019). Explaining active and passive types of counterproductive work behavior: The moderation effect of bullying, the dark triad and job control. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 32(6), 777–795. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01425

- Baloch, M. A., Meng, F., & Bari, M. W. (2018). Moderated mediation between IT capability and organizational agility. Human Systems Management, 37(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-17150

- Baloch, M. A., Meng, F., Xu, Z., Cepeda-Carrion, I., Danish., & Bari, M. W. (2017). Dark Triad, perceptions of organizational politics and counterproductive work behaviors: The moderating effect of political skills. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1972. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01972

- Baloch, M. A., Meng, F., & Lodhi, R. N. (2019). Information systems capabilities and customer capital: A multiple mediation model. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 16(3), 1950022. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219877019500226

- Baughman, H. M., Dearing, S., Giammarco, E., & Vernon, P. A. (2012). Relationships between bullying behaviours and the Dark Triad: A study with adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(5), 571–575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.020

- Berry, C. M., Carpenter, N. C., & Barratt, C. L. (2012). Do other-reports of counterproductive work behavior provide an incremental contribution over self-reports? A meta-analytic comparison. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 613–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026739

- Boddy, C. R. (2006). The dark side of management decisions: Organisational psychopaths. Management Decision, 44(10), 1461–1475. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740610715759

- Boddy, C. R. P. (2010). Corporate psychopaths and organizational type. Journal of Public Affairs, 10(4), 300–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.365

- Buenger, C. M., Forte, M., Boozer, R. W., & Maddox, E. N. (2007). A study of the applicability of the perceptions of organizational politics scale (POPS) for use in the university classroom. Developments in Business Simulation and Experiental Learning, 34, 294–301.

- Campbell, J., Schermer, J. A., Villani, V. C., Nguyen, B., Vickers, L., & Vernon, P. A. (2009). A behavioral genetic study of the dark triad of personality and moral development. Twin Research and Human Genetics: The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies, 12(2), 132–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.12.2.132

- Carrión, G. C., Nitzl, C., & Roldán, J. L. (2017). Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: guidelines and empirical examples. In H. Latan & R. Noonan (Ed.), Partial least squares path modeling (pp. 173–195). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3_8

- Cha, E. S., Kim, K. H., & Erlen, J. A. (2007). Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: Issues and techniques. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(4), 386–395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04242.x

- Chiaburu, D. S., Muñoz, G. J., & Gardner, R. G. (2013). How to spot a careerist early on: Psychopathy and exchange ideology as predictors of careerism. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(3), 473–486. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1599-5

- Cohen, A. (2016). Are they among us? A conceptual framework of the relationship between the dark triad personality and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs). Human Resource Management Review, 26(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.07.003

- Cohen, A., & Diamant, A. (2019). The role of justice perceptions in determining counterproductive work behaviors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(20), 2901–2924. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1340321

- Colbert, A. E., Mount, M. K., Harter, J. K., Witt, L. A., & Barrick, M. R. (2004). Interactive effects of personality and perceptions of the work situation on workplace deviance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 599–609. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.599

- Czarna, A. Z., Jonason, P. K., Dufner, M., & Kossowska, M. (2016). The Dirty Dozen Scale: Validation of a Polish version and extension of the nomological net. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 445–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00445

- Czarnota-Bojarska, J. (2015). Counterproductive work behavior and job satisfaction: A surprisingly rocky relationship. Journal of Management & Organization, 21(4), 460–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2015.15

- Dalal, R. S., Lam, H., Weiss, H. M., Welch, E. R., & Hulin, C. L. (2009). A within-person approach to work behavior and performance: Concurrent and lagged citizenship-counterproductivity associations, and dynamic relationships with affect and overall job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 1051–1066. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.44636148

- Dischner, S. (2015). Organizational structure, organizational form, and counterproductive work behavior: A competitive test of the bureaucratic and post-bureaucratic views. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(4), 501–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2015.10.002

- Ferris, G. R., Gail, R. S., & Patricia, F. M. (1989). Politics in organizations. In Impression management in the organization (pp. 143–170). Lawrence Erlbaum Associate Publishers.

- Grijalva, E., & Newman, D. A. (2015). Narcissism and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): Meta-analysis and consideration of collectivist culture, big five personality, and narcissism’s facet structure. Applied Psychology, 64(1), 93–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12025

- Guidice, R. M., Mero, N. P., Matthews, L. M., & Greene, J. V. (2016). The influence of individual regulatory focus and accountability form in a high performance work system. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3332–3340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.011

- Hair, J. F. J., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publication, Inc. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.002

- Hair, J. F., Hult, T., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling Vol. 46 (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(5), 616–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0517-x

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hall, A. T. (2005). Accountability in organizations: An examination of antecedents and consequences. http://search.proquest.com/docview/304997266?accountid=14549%5Cnhttp://hl5yy6xn2p.search.serialssolutions.com/?genre=article&sid=ProQ:&atitle=Accountability+in+organizations:+An+examination+of+antecedents+and+consequences&title=Accountability+in+organizat

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). Advances in international marketing. In J. Henseler, C. M. Ringle, & R. R. Sinkovics (Eds.), New challenges to international marketing. Howard House.

- Henseler, J. (2017). Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 178–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1281780

- Hochwarter, W. A., Perrewé, P. L., Hall, A. T., & Ferris, G. R. (2005). Negative affectivity as a moderator of the form and magnitude of the relationship between felt accountability and job tension. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(5), 517–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.324

- Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 420–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019265

- Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2012). The effects of emotional intelligence on counterproductive work behaviors and organizational citizen behaviors among food and beverage employees in a deluxe hotel. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 369–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.06.008

- Kacmar, K. M., Andrews, M. C., Harris, K. J., & Tepper, B. J. (2013). Ethical leadership and subordinate outcomes: The mediating role of organizational politics and the moderating role of political skill. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1373-8

- Kacmar, K. M., & Ferris, G. R. (1991). Perceptions of Organizational Politics Scale (POPS): Development and construct validation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51(1), 193–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164491511019

- Kapoutsis, I., & Thanos, I. C. (2016). Politics in organizations: Positive and negative aspects of political behavior. European Management Journal, 34(3), 310–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.04.003

- Karim, A., Samina, K., & Crawshaw, J. R. (2013). The mediating role of discrete emotions in the relationship between injustice and counterproductive work behaviors: A study in Pakistan. Journal of Business and Psychology, 28, 49–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-012-9269-2

- Kozako, I. N., ‘Ain, M. F., Safin, S. Z., & Rahim, A. R. A. (2013). The relationship of big five personality traits on counterproductive work behaviour among hotel employees: An exploratory study. Procedia Economics and Finance, 7(Icebr), 181–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(13)00233-5

- Limayem, M., Hirt, S. G., Chin, W. (2001). Intention does not always Matter: The contingent role of habit in IT usage behaviour. ECIS 2001 Proceedings, 274–286. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2001/56%5Cnhttp://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.83.2394&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Martin, L. E., Brock, M. E., Buckley, M. R., & Ketchen, D. J. (2010). Human resource management review time banditry: Examining the purloining of time in organizations. Human Resource Management Review, 20(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.013

- Meisler, G., Drory, A., & Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2019). Perceived organizational politics and counterproductive work behavior: The mediating role of hostility. Personnel Review, 49(8), 1505–1517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2017-0392

- Mero, N. P., Guidice, R. M., & Werner, S. (2014). A field study of the antecedents and performance consequences of perceived accountability. Journal of Management, 40(6), 1627–1652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312441208

- Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organisational behaviour. Personnel Psychology, 65(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x

- Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., & Meijer, E. (2017). The malevolent side of human nature: A meta-analysis and critical review of the literature on the dark triad (narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 12(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616666070

- Naseer, S., Raja, U., Syed, F., Donia, M. B. L., & Darr, W. (2016). Perils of being close to a bad leader in a bad environment: Exploring the combined effects of despotic leadership, leader member exchange, and perceived organizational politics on behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 14–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.09.005

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

- O’Boyle, E. H., Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., & McDaniel, M. A. (2012). A meta-analysis of the Dark Triad and work behavior: A social exchange perspective. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 557–579. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025679

- Palmer, J. (2016). Examining ethical leadership as a moderator of the relationship between the dark triad and counterproductive work behavior [Theses]. https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/theses/1913

- Palmer, J. C., Komarraju, M., Carter, M. Z., & Karau, S. J. (2017). Angel on one shoulder: Can perceived organizational support moderate the relationship between the Dark Triad traits and counterproductive work behavior? Personality and Individual Differences, 110, 31–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.018

- Patrick, C. J., Fowles, D. C., & Krueger, R. F. (2009). Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness. Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 913–938. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000492

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

- Picón, A., Castro, I., & Roldán, J. L. (2014). The relationship between satisfaction and loyalty: A mediator analysis ⋆. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 746–751. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.038

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

- Roldán, J. L., & Sánchez-Franco, M. J. (2012). Variance-based structural equation modeling. In Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems (pp. 193–221). IGI Global.

- Rosen, C. C., & Levy, P. E. (2013). Stresses, swaps, and skill: An investigation of the psychological dynamics that relate work politics to employee performance. Human Performance, 26(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2012.736901

- Sackett, P. R. (2002). The structure of counterproductive work behaviors: Dimensionality and relationships with facets of job performance. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10(1&2), 5–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00189

- Schlenker, B. R., Britt, T. W., Pennington, J., Murphy, R., & Doherty, K. (1994). The triangle model of responsibility. Psychological Review, 101(4), 632–652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.632

- Schwager, I. T. L., Hülsheger, U. R., & Lang, J. W. B. (2016). Be aware to be on the square: Mindfulness and counterproductive academic behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 74–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.043

- Schyns, B. (2015). Dark Personality in the Workplace: Introduction to the Special Issue. Applied Psychology, 64(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12041

- Smith, S. F., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2013). Psychopathy in the workplace: The knowns and unknowns. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(2), 204–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.11.007

- Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13(1982), 290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/270723

- Spurk, D., Keller, A. C., & Hirschi, A. (2016). Do bad guys get ahead or fall behind? Relationships of the Dark Triad of personality with objective and subjective career success. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615609735

- Steinbauer, R., Renn, R. W., Taylor, R. R., & Njoroge, P. K. (2014). Ethical leadership and followers’ moral judgment: The role of followers’ perceived accountability and self-leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(3), 381–392. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1662-x

- Stone-Romero, E. F., & Rosopa, P. J. (2008). The relative validity of inferences about mediation as a function of research design characteristics. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 326–352. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13813458209103817

- Tetlock, P. E. (1992). The impact of accountability on judgement and choice: Toward a social contingency model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 331–376.

- Vardi, Y., & Weitz, E. (2003). Misbehavior in organizations theory, research, and management. (P. Press, Ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Wu, J., & Lebreton, J. M. (2011). Reconsidering the despotional basis of counterproductive work behavior: The role of aberrant personality. Personnel Psychology, 64(3), 593–626. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01220.x

- Yang, F. (2017). Better understanding the perceptions of organizational politics: Its impact under different types of work unit structure. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(2), 250–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1251417

- Yin, P., Lau, Y., Tong, J. L. Y. T., Lien, B. Y., Hsu, Y., & Chong, C. L. (2017). Ethical work climate, employee commitment and proactive customer service performance: Test of the mediating effects of organizational politics. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 35, 20–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.11.004

- Ying, L., & Cohen, A. (2018). Dark triad personalities and counterproductive work behaviors among physicians in China. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 33(4), e985–e998. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2577

- Zhao, H., Peng, Z., & Sheard, G. (2013). Workplace ostracism and hospitality employees’ counterproductive work behaviors: The joint moderating effects of proactive personality and political skill. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33(1), 219–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.08.006