?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The benefits of financial development to economic growth are conspicuous, but due to the heterogeneity across regions and firms, the effects of financial competition have not been fully proved. There is a puzzling phenomenon in many developing countries, that is, banking monopoly coexists with economic growth. This study uses industrial enterprise data to analyse how banking competition affects firm total factor productivity (T.F.P.) and the influence of firm size and ownership in this process. The results show that the competition in banking promotes firms to improve their T.F.P., which is realised by alleviating financing constraints of firms through increasing banking competition and aligns with the market power hypothesis. Moreover, banking competition enables small firms to improve their T.F.P. in regions with fewer state-owned banks branches and more small banks branches. Intensified competition in banking leads to an increase in the T.F.P. of private firms, but it has no effect on the T.F.P. of state-owned enterprises (S.O.E.s) and foreign firms. The expansion of bank branches and the cross region operation of city commercial banks are helpful to improve firm T.F.P. This study confirms the impact of competition caused by changes in bank branches on firms and the determinants of productivity.

1. Introduction

Productivity plays a key role in promoting long-term economic growth, while improving productivity is difficult. As productivity stimulating factors change the progression of economic growth (Arora, Citation2001), verifying the determinants of firm productivity is important. An increasing number of studies have proved that financial development can promote the growth of firms. An efficient financial system can alleviate financial constraints of firms and improve the efficiency of loans allocation in the financial industry, thus promoting the productivity of firms. The supply of bank credit has significant effects on firm productivity (Franklin et al., 2020). The heterogeneous financing conditions of different industries promote the effective allocation of funds and the improvement of aggregate total factor productivity (T.F.P.) (Meza et al., Citation2019). Ignoring financing constraints leads to inaccurate productivity estimates, but there is no evidence that credit constraints reduce the productivity of small businesses (Cao & Leung, Citation2020). Although verifying the determinants of firm T.F.P. is important for policy makers and academics, rigorous studies that link banking competition and firm T.F.P. are sparse.

As the largest developing country and emerging economy, China has been experiencing an ongoing economic boom for 40 years, but there is still a puzzle. Under the background of complex and unstable economic situation, China’s previous growth mode of extensive economic driven by factor input is unsustainable. Loans from banks are the main source of firms financing. With the development of small banks, the asset share of state-owned banks has dropped from 63% in 1995 to 35% in 2020, but small firms are still faced with the problems of difficult and expensive financing.Footnote1 There is an irrational allocation of funds in the financial market (Lin et al., Citation2015). Thus, this study investigates the determinants and influencing mechanisms of firm T.F.P. from the perspective of competition among financial institutions, which is conducive to improving the efficiency of fund allocation.

Our empirical strategy utilise firm-level differences in T.F.P. across a number of industries to investigate how banking competition impact T.F.P. in China. Robust evidence reveals that banking competition promotes firm T.F.P. by alleviating financing constraints. The results show support to the market power hypothesis where higher competition lowers the market power of banks and eases firms’ financing constraints. We perform sensitivity analyses, which prove the robustness of these main results. Increased competition in banking institutions can improve the T.F.P. of small and private enterprises, while has no influence on large firms, state-owned enterprises (S.O.E.s) and foreign firms. Moreover, the expansion of bank branches and cross region operation of city commercial banks are helpful for firms to improve T.F.P. In addition, firm size, capital–labour ratio, profitability, export, operating years and industrial agglomeration are beneficial to the improvement of T.F.P. Therefore, promoting financial competition by privatising state-owned banks would be effective way to promote the productivity of firms.

This study has made some contributions. First, this article contributes to banking competition measurement. The structural and non-structural approaches are the primary methods to measure competition in the previous literature. We use the banking ownership structure and city commercial banks to measure the level of banking competition faced by firms in different regions. Second, we add microscopic evidence to the determinants of T.F.P. from the perspective of competition among financial institutions. In the past, most literatures studied the determinants of T.F.P. from the macro level, ignoring the influence of financial competition and heterogeneity of enterprises. Third, this article deepens the understanding of the mechanism that banking competition affects productivity. China is at a critical stage of the transformation of new and old kinetic energy, and the lack of strong evidence of productivity determinants has caused regret for promoting innovation-driven development strategy and high-quality economic development. Under the background of global economic slowdown caused by COVID-19 epidemic, the conclusions of the study are significance.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

2.1. The effects of banking competition on T.F.P.

There are two financing channels for enterprises, one is internal financing, the other is direct financing and indirect financing through financial institutions. The functions of financial market in capital supply, project evaluation and risk dispersion has an important impact on business operation and growth. A reduction in financing constraints is conducive to improve aggregate productivity (Caggese, Citation2019; Jimi et al., 2019). The development of banking can reduce the negative effects of the natural resource curse on productivity (Badeeb & Lean, Citation2017).

The market power hypothesis argues that banking competition alleviates firms’ financial constraints. The intensification of financial market competition improves firms’ financing accessibility by decreasing the lending rate (Santiago et al., Citation2009) and the adverse influences of rent-seeking by officials (Barth et al., Citation2009). On the contrary, the information hypothesis argues that competition results in financial constraints (Petersen & Rajan, Citation1995). The view holds that financial institutes tend to obtain soft information on opaque borrowers in the banking market with stronger market power, which is conducive to reducing information asymmetry and agency costs. If the market information is asymmetric, the intensification of banking competition reduces the motivation for banks to establish close relationships with firms by investing in the acquisition of firms’ soft information (González & González, 2014). In addition, when the information is asymmetric and the internal control of enterprises is imperfect, the competition in the banking industry aggravates the risk of stock price collapse of listed companies (Zhang et al., Citation2019). The development of banking can help firms overcome moral hazard and adverse selection, and reduce financing costs (González, 2020).

Although the banking structure has undergone profound reform under the guidance of the Chinese government, it is dominated by state-owned banks. The government controls the banking sector and has a powerful influence on the allocation of loans through holding state-owned banks, but has less influence on the operation of small banks. Therefore, market economic mechanism and economic fundamentals have less impact on the lending decisions of state-owned banks than that of small banks. Since the mid-1990s, the efficiency of loan allocation of state-owned banks has been low, because they have to provide loans to poorly managed S.O.E.s (Cull & Xu, Citation2003; Park & Sehrt, Citation2001). Lin et al. (Citation2015) find that small banks is positively associated with economic growth. An intermediate level of banking competition is desirable, since it can improve financing efficiency (Biswas & Koufopoulos, Citation2020). In Europe, low-level banking competition can support economic growth, reduce non-performing loans and improve financial stability, while financial stability significantly promotes economic growth. At the same time, the resilient banking system is of great significance to promote economic growth during the financial crisis (Ijaz et al., Citation2020). The discussion leads to the hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: There is a positive correlation between banking competition and firm T.F.P.

2.2. The effects of size competition on T.F.P.

The debate on the puzzling relation between banking competition and firm productivity remains inconclusive.

Size competition view emphasises that the monopoly of large banks is inappropriate, which leads to more credit resources being allocated to large firms (Berger et al., Citation2017). According to this view, there may be differences in the sensitivity of enterprises of different sizes to the competition of banking institutions (Beck et al., Citation2008). The competition among banks of different sizes leads to the dilemma that small enterprises are faced with financing difficulties and expensive financing than large enterprises (Chong et al., Citation2013). Large banks tend to lend to large firms that have hard information that can be easily quantified and transmitted (Stein, Citation2002). In contrast, small financial institutions have advantages in maintaining relationships with small enterprises (Berger et al., Citation2005). These enterprises have less chance of access to loans from large banks (Berger & Black, Citation2011; Berger & Udell, Citation2002), while small banks can alleviate the financing difficulties of small enterprises than large banks (Acharya et al., Citation2006; Chong et al., Citation2013).

Large companies have more business opportunities with less risks and low default rate (Borisova et al., Citation2015). Small firms have a smaller pool of financial institutes from which to obtain loans and have fewer opportunities to enter the direct financing market than large firms (Liu & Li, Citation2020). As a consequence, the financing needs of small firms cannot be met although they have comparative advantages in productivity. The rising share of bank financing provides funds for investment activities, thus improving the productivity of small firms (Adegboye & Iweriebor, Citation2018). Firm T.F.P. increases following the implementation of banking deregulations for small businesses, and that the increase is significantly higher for financially constrained firms (Krishnan et al., 2015). Financial competition increases the opportunities for opaque borrowers to obtain loans in homogeneous market dominated by small financial institutions, and reduce the opportunities for opaque borrowers to obtain loans in heterogeneous market with many large banks (Heddergott & Laitenberger, Citation2017). The cost of direct financing in China’s capital market is high, and it is difficult for small enterprises to improve their productivity through equity financing. Therefore, under the bank-led financial system, bank loans are important for small enterprises to achieve the goal of improving productivity. The discussion leads to the second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: The influence of banking competition on T.F.P. is stronger for small firms than for large firms.

2.3. The effects of ownership competition on T.F.P.

Ownership competition view pays attention to the monopolistic behavior of state-owned banks, and thinks that these banks are more inclined to provide loans to S.O.E.s than private enterprises (Borisova et al., Citation2015; Le et al., 2019). The domination of state-owned banks allows S.O.E.s to gain low-cost favourable loans through political connections. China’s financial structure is dominated by banks that tend to favour government-controlled firms (Chen et al., Citation2013). The view thus suggests privatising, as happened in Britain, or downsizing the large state-owned banks.

The government has great influence on S.O.E.s and banking institutions, such as through the allocation of loans by state-owned banks. There are more bank loan discrimination in areas with underdeveloped finance or more government management (Jiang & Li, Citation2006). Moreover, the state-owned shares strengthen the government’s implicit guarantee for corporate debt, so the bankruptcy probability of S.O.E.s is low. As a result of implicit debt guarantees, ineffective supervision and moral hazard, state ownership results in financial resource misallocation. Due to S.O.E.s’ soft budget constraints (Kornai et al., Citation2003), state-owned banks are more likely to rescue poorly managed S.O.E.s than distressed private firms to maintain the employment rate and social stability (Clement et al., Citation2010). Reducing the intensity of governments’ intervention is beneficial for private firms to obtain long-term debts (Liu et al., Citation2018). These discussions lead to the third hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: The effect of banking competition on T.F.P. is stronger for private firms than for S.O.E.s.

3. Methodology and data

3.1. Empirical methodology

We estimate T.F.P. to measure the performance of industrial enterprises and develop the following baseline equations to identify the influences of banking competition on firm T.F.P.:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

where j indexes the firm, i indexes the prefecture-level city and t indexes the year.Footnote2 T.F.P. is the dependent variable and denotes firm T.F.P. Following previous studies, the primary method for calculating firm-level T.F.P. in this study is the Giannetti et al. (Citation2015) and Schoar (Citation2002) estimator, which is commonly used to measure T.F.P. Moreover, we use the estimation method of Wurgler (Citation2000) to measure capital allocation efficiency as an alternative estimation variable of T.F.P.

State_bank and City_bank are the independent variables. Analysing the effects of banking competition requires the examination of competition metrics to check whether the results are consistent across different measures. Studies on industrial organisation provide various methods to measure market competition. The structure-conduct-performance theory suggests that industry concentration is negatively related to competitive conduct and results in lower profitability. Since IBBEA promotes the establishment of branches across states, there are more banks to compete with each other (Rice & Strahan, Citation2010). We construct structural measures to proxy for banking competition: the concentration ratio of prefecture-level bank branches (Carlson & Mitchener, Citation2009; Temesvary, 2015). Specifically, we use State_bank and City_bank to measure banking competition.

The control variable F denotes firm characteristics. The data’s panel dimension allows us to control for prefecture-level and firm-level heterogeneity. Following previous studies (Giebel & Kraft, Citation2019; Hsieh & Klenow, Citation2009), EquationEqs. (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) control firm and industry characteristics. ωi denotes the prefecture-level fixed effects and addresses concerns regarding omitted variables that may be correlated with firm T.F.P. ηt is the year fixed effects. εj,i,t is the error term. Standard errors are clustered at prefecture level and industry level. reports the variable definitions.

Table 1. Variable definitions.

Because there may be reverse causality and omitted variables, we need to identify the causal impact of banking competition on T.F.P. First, there are obvious differences in state-level characteristics that affect the timing of financial competition among different states in the United States (Kroszner & Strahan, 1999), and these differences may trigger banking competition. Moreover, firms with higher productivity have better access to funds, and that fewer credit constraints is positively associated with productivity (Altomonte et al., Citation2016), while firms with low productivity are more likely to be rejected by financial institutions (Motta, 2020). Banking competition is measured at the prefecture level in this study, whereas firm T.F.P. is measured at the firm-level which is derived from a different data set. Thus, the T.F.P. of firms is unlikely to affect banking competition at the prefecture level.

Second, omitted variables may bias the estimations and statistical inferences. Region and industry characteristics related to both banking competition and firm T.F.P. may remain in the residual terms and result in incorrect statistical inferences. It is hard for standard OLS regressions to produce correct statistical inferences when there are unobservable characteristics (Cornaggia et al., Citation2015). Therefore, following the work of Rajan and Zinagales (Citation1998), we use a panel-based fixed-effect identification approach to address the problem of identifying the specific effect mechanisms through which banking competition influences firm T.F.P. The approach controls the time series and cross-sectional dynamics. Moreover, we perform the regressions by lagging the independent variables and control variables by one year.

3.2. Data

We collect information about 1052608 industrial enterprises for the 1998–2013 period from the Annual Survey of Industrial Enterprise by the National Statistic Bureau of China. The information about banking institutions is from the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission. We match the two databases based on the geographical location information of the enterprises. Moreover, the observed values of all samples have non-missing values and are truncated by 1% at the top and bottom.

reports the summary statistics. The correlation coefficients among the independent variables are less than 0.53, and multi-collinearity is not an issue in the regressions.

Table 2. Summary statistics.

4. Empirical results

4.1. Baseline specification and result

presents the baseline models. The significantly negative coefficient on State_bank in column (1) and the significantly positive coefficient on City_bank in column (2) imply that banking competition is positively associated with firm T.F.P. The results in columns (5) and (6) confirm this finding while controlling firms’ characteristics which potentially affect firm T.F.P. These results suggest that increased banking competition (i.e., decrease in State_bank and increase in City_bank) leads to an increase T.F.P. This conclusion supports Hypothesis 1 that it is a positive correlation between banking competition and firm T.F.P., and align with the estimations of Bai et al. (Citation2018). After adding control variables, the goodness of fit of the estimated results of the model is improved, which shows that ignoring the role of enterprise characteristics and geographical location will misjudge the impact of banking competition on enterprise productivity.

Table 3. Baseline regressions.

State-owned banks dominate the financial market, while the development of small banks alleviates firms’ financing constraints and promotes firm T.F.P. Banking competition promotes the screening of borrowers, which enables firms to improve productivity (Chemmanur et al., Citation2020). However, Tello (Citation2015) observes no relationship between public financial support and the T.F.P. of manufacturing enterprises.

The significantly positive coefficients on firm size suggest that large firms have higher T.F.P. The coefficients of K_L and ROA are significantly positive, whereas debt ratio, management expenses and current assets of firms are negatively related to their T.F.P. These results show that higher capital to labour ratio and profitability favours higher T.F.P. for firms, possibly because obtaining funds is a way to improve T.F.P., such as internal financing. The significantly positive coefficients on Export reveal that an increase in firms’ export ability increases T.F.P. The significantly positive coefficients on Age mean that the T.F.P. of old firms is higher. Moreover, the coefficient estimates for Industry are significantly positive, suggesting that industry agglomeration results in economies of scale and then improves firm T.F.P.

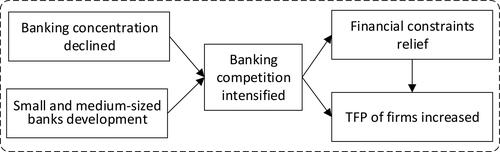

4.2. Impact mechanism test

If obtaining loans is an influencing mechanism of bank competition to promote enterprise productivity, then the promotion of bank competition to enterprises with severe financing constraints is more significant. Market competition intensifies, and external financing of enterprises increases, which is especially beneficial for enterprises with light financing constraints to obtain more funds, thus stimulating these enterprises to over-invest (Zhang et al., Citation2019). Hence, the competitive market of the banking industry become a key channel for firms to improve their T.F.P. by alleviating financing constraints, as shown in . We use two dimensions to measure firms’ financing constraints: the dependence of on external financing and the cost of pay for external financing (Beck et al., Citation2006; Yuriy & Monika, Citation2013). When the firm has external financing, Financing is equal to 1, otherwise it is equal to 0. Debt_cost is the ratio of interest expense to the debt. We expect that firms that rely more on external finance and have higher debt costs have an increase, instead of a decrease, in T.F.P. when banking competition intensifies.

Figure 1. The role of financial constraints in banking competition affecting firm TFP.

Source: The authors.

In columns (1) to (4) of , the positive coefficients of State_bank and the negative coefficients of City_bank suggest that the promotion of banking competition to firm T.F.P. is driven by enhancing the availability of financing. The coefficient estimate of City_bank is significantly negative in column (6), thereby suggesting that banking competition has a negative influence on firms’ debt costs.

Table 4. Impact mechanism test results.

The intensification of competition among financial institutions improves the accessibility of funds and reduces the debt cost of enterprises (Wang et al., 2020), which is beneficial for firms to improve productivity. Similarly, Li et al. (2020) argue that the intensified competition in the banking industry reduces the debt cost of enterprises. In the highly competitive loan market, small financial institutions are more willing to provide low-cost financing to enterprises than large financial institutions (Lian, Citation2018). Therefore, financing costs play a key role in banking competition impacting firm T.F.P., especially for firms who suffer high financing cost.

4.3. The role of firm size in banking competition affecting T.F.P.

The sensitivity of T.F.P. to banking competition may vary by firm size. Small firms face more information friction and lack of external financing channels than large firms. We check whether small business have higher T.F.P. in areas where small banks occupy more market than areas where state-owned banks occupy more market. This study classifies firms into three categories according to their asset size and re-estimate EquationEqs. (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) . Specifically, we define firms with assets less than 40 million yuan as small firms, firms with assets between 40 million and 400 million yuan as medium firms, and firms with assets over 400 million yuan as large firms.

The negative coefficient on of State_bank in column (1) and the positive coefficients on City_bank in columns (2) and (4) reveal that banking competition improves T.F.P. for small firms. The results in columns (5) and (6) show that banking competition has no effect on T.F.P. of large firms. Moreover, the coefficients of State_bank and City_bank have higher absolute values for small firms than for medium and large firms, which implies that the T.F.P. of large and medium-sized enterprises is less resilient to banking competition than that of small enterprises. These findings support Hypothesis 2, and Adegboye and Iweriebor (Citation2018) find similar result for Nigeria.

The promotion effect of banking competition on T.F.P. is primarily observed in small firms that are more vulnerable to information asymmetry and adverse selection. One possible explanation is that although financial institutions are more motivated to provide funds for companies with transparent management, as the competition among banking institutions intensifies, their funds for companies with low transparency increase than before. Large financial institutions are reluctant to provide services to small companies because they may be a source of bad debts (Dimelis et al., Citation2019), while credit competition alleviates the financial difficulties for small firms (Rice & Strahan, Citation2010). Therefore, the improvement of the financing environment for small firms improves their T.F.P. ().

Table 5. Banking competition and TFP: the role of firm size.

4.4. The role of firm ownership in banking competition affecting T.F.P.

The regression results show that regional banking competition can promote the T.F.P. of enterprises, but the promotion effect may be affected by the ownership of enterprises. Following Shailer and Wang (Citation2015), we decompose the sample into private firms in which natural person is are the controlling shareholder, S.O.E.s in which the government is the controlling shareholder, and foreign firms in which foreign investor is the controlling shareholder. EquationEquations (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) are applied to private firms, S.O.E.s and foreign firms, respectively.

We expect S.O.E.s and foreign firms to be less influenced than private firms by banking competition on T.F.P., which is confirmed by the results in . The coefficient estimates of State_bank and City_bank in the subsample of private firms have higher absolute values and are significant, whereas those for the subsample of S.O.E.s and foreign firms have lower absolute values and are not significant. Private firms are sensitive to banking competition, while S.O.E.s and foreign firms are not affected by changes in banking competition. In column (1), the coefficient of State_bank means that each extra proportion of competition increases T.F.P. by 0.016 bps. The significant coefficient on City_bank reveals that the promotion impact of banking competition on T.F.P. is 0.033 bps for private firms in column (2). These results support Hypothesis 3.

Table 6. Banking competition and TFP: the role of ownership.

S.O.E.s suffer fewer financial constraints than private firms because S.O.E.s can obtain loans from banks via loan guarantees by governments. Firms with political ties face lower financing constraints than those without political ties (Song et al., 2015), while the benefits brought by government guarantees are few where banking institutions are highly competitive. Although S.O.E.s can obtain loans from banks due to government guarantees and are less influenced by banking competition than private firms, the enhancement of banking competition increases the opportunities for private companies to obtain loans despite having fewer political connections. Therefore, the increased competition among banks can explain why the T.F.P. of private firms is higher than that of S.O.E.s, and why the T.F.P. of S.O.E.s failed to catch up with private firms. Similarly, Gao et al. (Citation2017) find that increased competition among banking institutions will improve the efficiency, sales and investment of firms, especially for private firms. Moreover, foreign companies can obtain funds from their foreign parent companies, which will meet their capital needs. Therefore, the competition of banking institutions has little influence on the TFF of S.O.E.s and foreign-funded enterprises.

4.5. Robustness tests

This subsection presents several methods to check the robustness of the main findings. In columns (1) to (4) of , the negative coefficients of State_bank and the positive coefficients of City_bank suggest that banking competition is correlated with higher labor productivity and capital allocation efficiency. These results are consistent with earlier observations and provide supports for Hypothesis 1.

Table 7. The results of the robustness examination.

Second, State_bank2 and City_bank2 are included in the regressions to consider nonlinear relationships between banking competition and T.F.P. In column (5), the positive coefficient of State_bank2 and the negative coefficients of State_bank suggest a U-shaped relationship between banking concentration and T.F.P. This result supports the view that, initially, as the banking concentration value increases (i.e., banking competition decreases), firm T.F.P. decreases until State_bank reaches the inflection point. Above that level, banking concentration is positively associated with T.F.P. We compute the inflection point for State_bank and find that the threshold is 0.64. This value is in the range of values for the prefecture-level observations of banking competition but exceeds 75% of the prefecture-level observations. In other words, the negative relationship between banking concentration and firm T.F.P. aligns with the findings that greater banking competition fosters T.F.P. in 75% of prefecture-level divisions in China. Rising banking competition promotes firm T.F.P. when State_bank is lower than 0.64, whereas banking competition hinders firm productivity when State_bank is higher than 0.64. In column (6), the squared term of City_bank is significantly positive, and the linear term is positive but not significant. The inflection point of this model is negative, which does not exist in economic sense. Therefore, adding branches of city banks can promote T.F.P.

Third, this study uses the total number of branches of banks in different regions and the strength of cross-regional branches of city commercial banks to measure banking competition. Specifically, Branches is the logarithm of the number of commercial bank branches (Chemmanur et al., Citation2020). Cross is the ratio of cross region branches of city commercial banks to commercial bank branches. The positive coefficients of Branches and Cross in columns (7) and (8) imply that setting up branches of banks and expanding in different places of city commercial banks will promote T.F.P. of enterprises.

In addition, we perform estimations by separating for old firms and young firms defined as which has been found no more than six year. We divide all the observed firms into two groups by using the median operating years of the firms (i.e., young firms and old firms). Specifically, the negative coefficients on State_bank and the positive coefficients on City_bank in reveal that reduction of bank concentration and the expansion of city banks not only improve the T.F.P. of young enterprises, but also improve the T.F.P. of old enterprises. Moreover, the expansion of city commercial banks has a greater effect on the productivity of young enterprises than that of old enterprises.

Table 8. The results of the robustness examination.

5. Conclusions and implications

Productivity is a major source of long-term economic growth and competitive advantages. In this study, the change of market share of branches of state-owned banks and city commercial banks is used to measure the competition of banking institutions. The regression results show that enhancing the competition of banking institutions can improve the T.F.P. of enterprises. This finding contradicts the claims of Petersen and Rajan (Citation1995), who believe that the increase of bank concentration is beneficial for enterprises to obtain funds. Moreover, the promotion effect of banking competition on T.F.P. mainly occurs in small enterprises and private enterprises. Banking competition expands access to credit for these firms and alleviate their financial constraints, thus promoting their T.F.P. In addition, the expansion of bank branches and cross region operation of city banks are beneficial for T.F.P.

An effective mechanism to improve firm T.F.P. and reduce credit discrimination for small firms and private firms is to enhance the competition of banking industry. The conclusions give reason for caution, increased banking competition improves firm T.F.P., but large firms, S.O.E.s and foreign firms benefit less than small firms and private firms. State ownership results in low firm T.F.P. as a result of implicit debt guarantees, implying that reducing unreasonable government interventions should be effective way of improving loans allocation efficiency and productivity. These suggestions are helpful to policymakers and provide information for the marketisation of developing economies. In addition, the competition among banking institutions promotes highly transparent enterprises more than opaque enterprises, so further improving the information disclosure mechanism of small enterprises and non-S.O.E.s plays a key role in improving the productivity of these enterprises (Liu & Li, Citation2020).

Because the loans of the state-owned banks are disclosed at the provincial level, we have to use the concentration of branches to measure competition. According to the institutional economics theory, we believe that there are alternative institutional arrangements to replace the formal institutions in financing allocation arrangements. These alternative arrangements may be informal rules based on corrupt practices. Therefore, the impacts of bribery on loan allocation and productivity should be investigated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The state-owned banks are the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the Bank of China, the Construction Bank of China, and the Agricultural Bank of China.

2 As of June 2018, China has 334 prefecture-level administrative regions. Specifically, Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing are treated as an independent sample in this study.

References

- Acharya, V. V., Hasan, I., & Saunders, A. (2006). Should banks be diversified? Evidence from individual bank loan portfolios. The Journal of Business, 79(3), 1355–1412. https://doi.org/10.1086/500679

- Adegboye, A. C., & Iweriebor, S. (2018). Does access to finance enhance SME innovation and productivity in Nigeria? Evidence from the World Bank Enterprise Survey. African Development Review, 30(4), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12351

- Altomonte, C., Gamba, S., Mancusi, M. L., & Vezzulli, A. (2016). R&D investments, financing constraints, exporting and productivity. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 25(3), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2015.1076203

- Arora, S. (2001). Health, human productivity, and long-term economic growth. The Journal of Economic History, 61(3), 699–749.

- Badeeb, R., & Lean, H. (2017). Natural resources and productivity: Can banking development mitigate the curse? Economies, 5(2), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5020011

- Bai, J. J., Carvalho, D., & Phillips, G. M. (2018). The impact of bank credit on labor reallocation and aggregate industry productivity. The Journal of Finance, 73(6), 2787–2836. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12726

- Barth, J. R., Lin, C., Lin, P., & Song, F. M. (2009). Corruption in bank lending to firms: Cross-country micro evidence on the beneficial role of competition and information sharing. Journal of Financial Economics, 91(3), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.04.003

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Laeven, L., & Maksimovic, V. (2006). The determinants of financing obstacles. Journal of International Money and Finance, 25(6), 932–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2006.07.005

- Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2008). Financing patterns around the world: Are small firms different? Journal of Financial Economics, 89(3), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.10.005

- Berger, A. N., & Black, L. K. (2011). Bank size, lending technologies, and small business finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(3), 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.09.004

- Berger, A. N., Bouwman, C. H. S., & Kim, D. (2017). Small bank comparative advantages in alleviating financial constraints and providing liquidity insurance over time. The Review of Financial Studies, 30(10), 3416–3454. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhx038

- Berger, A. N., Frame, W. S., & Miller, N. H. (2005). Credit scoring and the availability, price, and risk of small business credit. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 37(2), 191–222. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.315044

- Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2002). Small business credit availability and relationship lending: The importance of bank organisational structure. Economic Journal, 112(477), 32–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00682

- Biswas, S., & Koufopoulos, K. (2020). Bank competition and financing efficiency under asymmetric information. Journal of Corporate Finance, 65, 101504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.101504

- Borisova, G., Fotak, V., Holland, K., & Megginson, W. L. (2015). Government ownership and the cost of debt: Evidence from government investments in publicly traded firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 118(1), 168–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.06.011

- Caggese, A. (2019). Financing constraints. Radical versus incremental innovation, and aggregate productivity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 11(2), 275–309. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20160298

- Cao, S., & Leung, D. (2020). Credit constraints and productivity of SMEs: Evidence from Canada. Economic Modelling, 88, 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.09.018

- Carlson, M., & Mitchener, K. J. (2009). Branch banking as a device for discipline: Competition and bank survivorship during the Great Depression. Journal of Political Economy, 117(2), 165–210. https://doi.org/10.1086/599015

- Chemmanur, T. J., Qin, J., Sun, Y., Yu, Q., & Zheng, X. (2020). How does greater bank competition affect borrower screening? Evidence from China's WTO entry. Journal of Corporate Finance, 65, 101776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101776

- Chen, Y., Liu, M., & Su, J. (2013). Greasing the wheels of bank lending: Evidence from private firms in China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(7), 2533–2545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.02.002

- Chong, T. T.-L., Lu, L., & Ongena, S. (2013). Does banking competition alleviate or worsen credit constraints faced by small- and medium-sized enterprises? Evidence from China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(9), 3412–3424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.05.006

- Clement, C., Song, F. M., & Wong, K. P. (2010). Investment and the soft budget constraint in China. International Review of Economics & Finance, 19(2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2009.10.003

- Cornaggia, J., Mao, Y., Tian, X., & Wolfe, B. (2015). Does banking competition affect innovation? Journal of Financial Economics, 115(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.09.001

- Cull, R., & Xu, L. C. (2003). Who gets credit? The behavior of bureaucrats and state banks in allocating credit to Chinese state-owned enterprises. Journal of Development Economics, 71(2), 533–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00039-7

- Dimelis, S., Giotopoulos, I., & Louri, H. (2019). Banking concentration and firm growth: The role of size, location and financial crisis. Bulletin of Economic Research, 71(3), 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/boer.12184

- Franklin, J., Rostom, M., & Thwaites, G. (2020). The banks that said no: The impact of credit supply on productivity and wages. Journal of Financial Services Research, 57(2), 149–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-019-00306-8

- Gao, H., Ru, H., Townsend, R. M., & Yang, X. (2017). Rise of bank competition: Evidence from banking deregulation in China. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3087081

- Giannetti, M., Liao, G., & Yu, X. (2015). The brain gain of corporate boards: Evidence from China. The Journal of Finance, 70(4), 1629–1682. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12198

- Giebel, M., & Kraft, K. (2019). External financing constraints and firm innovation. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 67(1), 91–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12197

- González, F. (2020). Bank development, competition, and entrepreneurship: International evidence. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 56, 100642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2020.100642

- González, V. M., & González, F. (2014). Banking liberalization and firms' debt structure: International evidence. International Review of Economics & Finance, 29(1), 466–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2013.07.008

- Heddergott, D., & Laitenberger, J. (2017). A simple model of banking competition with bank size heterogeneity and lending spillovers. Economic Notes, 46(2), 381–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecno.12083

- Hsieh, C. T., & Klenow, P. J. (2009). Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4), 1403–1448. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.4.1403

- Ijaz, S., Hassan, A., Tarazi, A., & Fraz, A. (2020). Linking bank competition, financial stability, and economic growth. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 21(1), 200–221. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2020.11761

- Jiang, W., & Li, B. (2006). Institutional environment, state ownership and lending discrimination. Journal of Financial Research, 51(11), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1109/MILCOM.2006.302511

- Jimi, N. A., Nikolov, P. V., Malek, M. A., & Kumbhakar, S. (2019). The effects of access to credit on productivity: Separating technological changes from changes in technical efficiency. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 52(1-3), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-019-00555-8

- Kornai, J., Maskin, E., & Roland, G. (2003). Understanding the soft budget constraint. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(4), 1095–1136. https://doi.org/10.1257/002205103771799999

- Krishnan, K., Nandy, D. K., & Puri, M. (2015). Does financing spur small business productivity? Evidence from a natural experiment. The Review of Financial Studies, 28(6), 1768–1809. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhu087

- Kroszner, R. S., & Strahan, P. E. (1999). What drives deregulation? Economics and politics of the relaxation of bank branching restrictions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4), 1437–1467. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556223

- Le, M.-D., Pieri, F., & Zaninotto, E. (2019). From central planning towards a market economy: The role of ownership and competition in Vietnamese firms’ productivity. Journal of Comparative Economics, 47(3), 693–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2019.04.002

- Li, S., Fu, H., Wen, J., & Chang, C.-P. (2020). Separation of ownership and control for Chinese listed firms: Effect on the cost of debt and the moderating role of bank competition. Journal of Asian Economics, 67, 101179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2020.101179

- Lian, Y. (2018). Bank competition and the cost of bank loans. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 51(1), 253–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-017-0670-9

- Lin, J. Y., Sun, X., & Wu, H. X. (2015). Banking structure and industrial growth: Evidence from China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 58(9), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.02.012

- Liu, F., Bian, C., & Gan, C. (2018). Government intervention and firm long-term bank debt: Evidence from China. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 12(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-03-2016-0040

- Liu, P. S., & Li, H. J. (2020). Does bank competition spur firm innovation? Journal of Applied Economics, 23(1), 519–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/15140326.2020.1806001

- Meza, F., Pratap, S., & Urrutia, C. (2019). Credit, misallocation and productivity growth: A disaggregated analysis. Review of Economic Dynamics, 34, 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2019.03.004

- Motta, V. (2020). Lack of access to external finance and SME labor productivity: Does project quality matter? Small Business Economics, 54(1), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0082-9

- Park, A., & Sehrt, K. (2001). Tests of financial intermediation and banking reform in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 29(4), 608–644. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcec.2001.1740

- Petersen, M., & Rajan, R. G. (1995). The effect of credit market competition on lending relationships. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2), 407–444. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118445

- Rajan, R. G., & Zinagales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 559–586.

- Rice, T., & Strahan, P. (2010). Does credit competition affect small-firm finance? The Journal of Finance, 65(3), 861–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01555.x

- Santiago, C.-V., Francisco, R.-F., & Udell, G. F. (2009). Bank market power and SME financing constraints. Review of Finance, 13(2), 309–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfp003

- Schoar, A. (2002). Effects of corporate diversification on productivity. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2379–2403. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00500

- Shailer, G., & Wang, K. (2015). Government ownership and the cost of debt for Chinese listed corporations. Emerging Markets Review, 22(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2014.11.002

- Song, M., Ai, H., & Li, X. (2015). Political connections, financing constraints, and the optimization of innovation efficiency among China's private enterprises. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 92, 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.10.003

- Stein, J. C. (2002). Information production and capital allocation: Decentralized versus hierarchical firms. The Journal of Finance, 57(5), 1891–1921. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00483

- Tello, M. D. (2015). Firms' innovation, public financial support, and total factor productivity: The case of manufactures in Peru. Review of Development Economics, 19(2), 358–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12147

- Temesvary, J. (2015). Dynamic branching and interest rate competition of commercial banks: Evidence from Hungary. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 43(6), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2015.09.003

- Wang, X., Han, L., & Huang, X. (2020). Bank competition, concentration and EU SME cost of debt. International Review of Financial Analysis, 71, 101534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101534

- Wurgler, J. (2000). Financial markets and the allocation of capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1-2), 187–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00070-2

- Yuriy, G., & Monika, S. (2013). Financial constraints and innovation: Why poor countries don't catch up. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(5), 1115–1152. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12033

- Zhang, X. R., Zhao, Y. L., Qi, R. K., & Usman, M. (2019). The impact of bank competition on stock price crash risk: Evidence from the Chinese market. Transformations in Business & Economics, 18(2b), 900–920.