?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Exports experienced extraordinary growth rates during the last decade in North Macedonia capturing above 50% share of the country’s GDP. However, the COVID-19 crisis interrupted the positive export series imposing various constraints in multiple dimensions on export-oriented firms. This study explores the multidimensionality of the COVID-19 impact on exporters in North Macedonia. We find that COVID-19 caused a systematic slowdown in the exporters’ revenue, profit, investment, capital, employment and salaries growth rates. Moreover, the limited access to finance, import exposure to EU markets, high labour-intensity, export exposure to non-EU markets and lower competitiveness make exporters less resilient to the pandemic shocks representing the main obstacles exporters are/will be facing in the recovery stage.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

COVID-19 crisis hit North Macedonia after years of unprecedented export growth, and deteriorated the expectations that both net export and FDIs would continue to bring positive and increasing contribution to the growth of economic activity in the near to long term (Ministry of Finance, Citation2019). In 2019, exports of goods and services from North Macedonia grew by 9.6%, continuing the increasing trend of the past 10 years, and reaching 56% of GDP. In the past ten years, FDI inflows in North Macedonia averaged 3% of GDP annually, providing direct benefits to the economy by contributing to sectoral and export diversification, import coverage and job creation.Footnote1

The early evidence shows a significant disruption of global trade as a result of COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic instigated supply chain disruptions mostly affecting globally-oriented and heavily interconnected sectors and firms (e.g. Aral et al., Citation2020; Balla-Elliott et al., Citation2020; Barrot et al., Citation2020; Bonadio et al., Citation2020; Buchheim et al., Citation2020; Carletti et al., Citation2020; Davis et al., Citation2020; Ding et al., Citation2020; Hyun & Kim, Citation2020; Inoue & Todo, Citation2020; Meier & Pinto, Citation2020; Navaretti et al., Citation2020; Pichler et al., Citation2020; Ramelli & Wagner, Citation2020; Sforza & Steininger, Citation2020). The extent of firms’ interconnectedness inflates the significance of indirect shocks over the direct loss caused by the pandemic. The greater access to finance and accumulation of liquidity helped firms to better weather the initial shock caused by COVID-19 (e.g. Acharya & Steffen, Citation2020; Aral et al., Citation2020; Beck et al., Citation2020; Carletti et al., Citation2020; Ding et al., Citation2020; Fahlenbrach et al., Citation2020; Ramelli & Wagner Citation2020; Schivardi & Romano, Citation2020). The small and financially constrained firms face greater challenges as the COVID-19 pandemic evolves.

Additionally, the COVID-19 impact is a combination of supply and demand shocks reflecting the heterogenous sectoral effects across the countries. To one side, the lockdowns and the spread of infections restrict labour supply and limit workforce management mostly affecting upstream firms’ capacities to produce and deliver their goods and services. The labour-intensive sectors and firms with lower capacity to allow workers to work from home (WFH) experienced significant supply-side disruptions during the pandemic (e.g. Alstadsaeter et al., Citation2020; Gottlieb et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Hatayama et al., Citation2020; Koren & Pető, Citation2020; Papanikolaou & Schmidt Citation2020). On the other side, COVID-19 caused direct shocks to the aggregate consumption through the changes in households’ behavior and indirect demand shocks through the closures of non-essential sectors (e.g. Aral et al., Citation2020; Barrot et al., Citation2020; Beck et al., Citation2020; Bodenstein et al., 2020; Gourinchas et al., Citation2020). Finally, the pandemics/epidemics affect firms’ competitiveness through increasing the trade costs and depressing the market share, investments and profitability (e.g. Altig et al., Citation2020; CIT0013Beck et al., Citation2020; Carletti et al., Citation2020; Fernandes & Tang Citation2020; Sforza & Steininger Citation2020), but also their competitiveness is pivotal in cushioning the negative effects (e.g. Hyun & Kim, Citation2020). The heterogenous effects of COVID-19 arise from the multidimensionality of the impact as some firms are prone to increasing losses depending on the constraints they are facing with. The recent literature has investigated each of these shocks separately; however, no study integrates the knowledge and examines the multidimensionality of the impact.

In this study, we analyze the findings from a comprehensive survey, focused on the obstacles of export-oriented firms before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in North Macedonia. The survey was conducted with export-oriented firms residing in North Macedonia, through a computer-assisted and telephone-assisted interview between October 1st and October 23rd, 2020. We structured the survey to target five firms’ segments heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: liquidity, supply chain, competitiveness, demand and workforce. We explore the importance of each segment and identify the main firm characteristics which make firms susceptible or resistant to the COVID-19 shocks. The survey targets the largest export-oriented firms in North Macedonia. While no survey sample is fully representative, due to the selection bias created by the limited survey coverage and limited response rate by the firms, we find that our respondents broadly match the characteristics of export-oriented firms in North Macedonia by leveraging an alternative survey data from the Enterprise Survey 2019 conducted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB) and World Bank Group (WBG). Such survey structure allows us to implement the ES2019 weights constructed for making inferences on the population level. The survey data was supplemented with financial statement data used as an input in the descriptive and regression analysis.

The results show that the COVID-19 crisis has caused systematic deceleration of revenue, profit, investment, capital, employment and salaries growth among exporters in North Macedonia. While largely negative, the effect was heterogenous among sectors, where the Automotive and Computer and electronic equipment sectors experienced the hardest hit. Certain firm characteristics such as the limited access to finance, import exposure to EU markets, high labour-intensity, export exposure to non-EU markets and lower competitiveness make exporters less resilient to the pandemic shocks representing the main obstacles exporters are/will be facing in the recovery stage.

This study contributes to the existing literature in two aspects. Firstly, this study joins the expanding literature of firm-level analyses of COVID-19 impact, mainly concentrated to the developed economies. The influence of COVID-19 on firms has been investigated largely in the US (e.g., Acharya & Steffen, Citation2020; Alekseev et al Citation2020; Aral et al., Citation2020; Davis et al., Citation2020; Fahlenbrach et al., Citation2020; Ramelli & Wagner, Citation2020), Germany (e.g. Balleer et al., Citation2020), Denmark (e.g. Bennedsen et al., Citation2020), Italy (e.g. Carletti et al., Citation2020) and in international context (e.g. Beck et al., Citation2020; Ding et al., Citation2020; Hyun & Kim, Citation2020). Our study examines the COVID-19 impact on exporters for a small open developing economy located in South-Eastern Europe and closely relates to Stojcic (Citation2020) who analyses the COVID-19 impact on the export competitiveness of manufacturing firms in Croatia. Moreover, the study is explorative in nature analyzing multiple dimensions of firm operations by leveraging a uniquely designed survey. Secondly, this study adds to the existing literature focused on trade disruptions during epidemics/pandemics by analyzing the exporters’ perceptions and expectations during the pandemic (e.g. Bonadio et al., Citation2020; Fernandes & Tang, Citation2020; Sforza & Steininger, Citation2020).

The study is structured as follows: In Section 2, we review the most recent literature on COVID-19 impact on firms and map firms’ segments mostly affected during the pandemic; in Section 3, we present the survey summary and describe data and methods used; in Section 4, we assess the COVID-19 impact on exporters and we identify the exporters’ obstacles during and after the pandemic; In Section 5, we provide concluding remarks.

2. Background discussion

The literature concerned with COVID-19 consequences on businesses is rapidly growing. Researchers uncovered that the extent of firms’ international orientation, financial flexibility, labour-intensity and customers’ behavior are determining factors of firms’ susceptibility to increasing losses due to COVID-19. The short-term COVID-19 shocks may easily translate to mid- to long-term deterioration of firms’ competitiveness. While many firms would suffer from the pandemic shocks, some may face novel opportunities for expansion and development as the pandemic subsides.

The pandemic has induced broad trade disruptions as the negative shocks diffuse not only across countries, but also across sectors within a country. The evidence of cross-country transmission of COVID-19 shocks mainly relates to the developed countries. Bonadio et al., (Citation2020) show that the reopening of large economies (such as China and USA) would have a significant impact on GDPs of other countries. Similarly, Sforza and Steininger (Citation2020) argue that higher degree of integration in global production network of one country means higher susceptibility to transmission shocks caused by the pandemic. The empirical evidence shows that firms more exposed through their international supply chains suffer larger stock price declines compared to less exposed firms (Ding et al., Citation2020). For instance, US firms and sectors with higher degree of Chinese imports experienced significant losses (Meier & Pinto, Citation2020; Ramelli & Wagner, Citation2020) and even lost part of their Chinese suppliers at the beginning of the pandemic (Aral et al., Citation2020).Footnote2 On the contrary, Hyun and Kim (Citation2020) find that market power supports globally-oriented firms to withstand the pandemic shocks. While the COVID-19 shocks may diffuse across countries, researchers argue that the diffusion effects arise across sectors within a country. Inoue and Todo (Citation2020) show that one-day lockdown in Tokyo causes significant production loss outside of Tokyo. Navaretti et al. (Citation2020) identify the central sectors in the national production network of Italy and argue that the activation of the central sectors would significantly increase value of production during the lockdown. Finally, Balla-Elliott et al. (Citation2020) find that the firm’s decision to re-open after a lockdown depends on the activation of its suppliers. Consequently, we hypothesise that the magnitude of the COVID-19 impact on export-oriented firms depends on their sectoral and geographical (input) exposure, as well as on their procurement capacity.

The heterogenous impact of COVID-19 on firms does not arise only from their supply chain exposures, but also from their differential access to finance. Ramelli and Wagner (Citation2020) and Ding et al. (Citation2020) find that stock markets punished firms with limited cash reserves and higher degree of leverage during the initial shocks of COVID-19. Generally, greater financial constraints relate to the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) which are more likely to rely on state liquidity support programs (Cororaton & Rosen, Citation2020). However, Paaso et al. (Citation2020) attribute the low take-up rates on state loan programs to the debt aversion of small entrepreneurs. Alekseev et al. (Citation2020) find that SMEs tend to primarily use their personal savings and informal sources of financing to fight the pandemic shocks. On the other side, Fahlenbrach et al. (Citation2020) find that highly financially flexible firms suffered less during the pandemic.Footnote3 Moreover, Stojcic (Citation2020) observe that firms that solve their liquidity issues through equity financing, deferred payments and state-aid grants are less likely to experience decreasing export revenues. The good capitalization and better access to finance enable firms to avoid debt overhang which may deter future investments (Aral et al., Citation2020; Carletti et al., Citation2020). Thus, we expect the magnitude of the COVID-19 impact to vary according to the ability of exporters to leverage capital and debt markets, and the size of their cash reserves.

The financially weaker firms have a tendency to downsize during the pandemic (Alstadsaeter et al., Citation2020). Barrero et al. (Citation2020) find that COVID-19 caused a significant labour reallocation shock as the negatively affected sectors relied on layoffs, while positively affected recruited new workers. However, the state support through labour subsidies significantly alleviates the job losses (Bennedsen et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the sectors and firms which have higher capacity to allow their workers to work from home (WFH) reduced their workforce by less compared to the sectors and firms with lower WFH capacity (Alekseev et al., Citation2020; Papanikolaou & Schmidt, Citation2020). While workers in developed countries have higher WFH ability (Gottlieb et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Hatayama et al., Citation2020) find that workers in North Macedonia fare better with respect to the WFH ability compared to its peers in the developing world. While WFH capacity supports jobs retention, it has ambiguous effects on workers’ productivity (Bartik et al., Citation2020; Koren and Pető, Citation2020; Morikawa Citation2020). Finally, the investments in automation may reduce susceptibility to labour supply shocks caused by the pandemic (Caselli et al., Citation2020; Chernoff & Warman, Citation2020). Hence, we hypothesise that human capital constraints and labour intensity explain the variation in COVID-19 impact.

The slump in employment translates in anemic aggregate consumption (Bodenstein et al., 2020). Balleer et al. (Citation2020) find that COVID-19 demand effects dominate on the short-run causing drop in inflation. Additionally, the sectors and firms located downstream in the supply chains and deemed as non-essential suffer the most due to administrative closings. For instance, firms with high exposure to travel and leisure received the hardest hit, while telecommunication and technical services experienced minor negative and even positive effects (Balla-Elliott et al., Citation2020; Barrot et al., Citation2020; Davis et al., Citation2020; Gourinchas et al., Citation2020). Evidently, the drop in consumption could be significant during the pandemic, however businesses could be less exposed to the demand shocks depending on their market power (Hyun & Kim, Citation2020), substitutability of their products (Fernandes & Tang, Citation2020), flexible relationships with their customers and employees (Beck et al., Citation2020) and investments in corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities (Ding et al., Citation2020). Consequently, we expect the magnitude of the COVID-19 impact to depend on the importance of the demand shocks, sectoral and geographical (output) exposure.

The immediate COVID-19 shocks may be cushioned depending on firms’ competitiveness, but also these shocks may translate to mid- to long-term effects on firms’ competitiveness through their decisions for current and future investment activities. For instance, Hyun and Kim (Citation2020) find that market power supports globally-oriented firms to withstand the pandemic shocks. On the other side, Beck et al. (2020) find that businesses prefer to reduce their investments rather than to execute layoffs in order to fight the economic consequences of the pandemic. Moreover, Carletti et al. (Citation2020) argue that firm indebtedness would deter investments in future. Another channel could be the rise of trade costs, especially on imported intermediate inputs. Sforza and Steininger (Citation2020) claim that trade barriers would exacerbate the income losses in addition to those generated by COVID-19. Finally, Fernandes and Tang (Citation2020) show that firms with capital-intensive, skill-intensive and differentiated products could better withstand export disruptions and drive the economic recovery, while firms with mass-produced and low-tech products could be easily replaced during temporary trade disruptions. Thus, we hypothesise that exporters’ competitiveness plays pivotal role in mitigating the COVID-19-induced losses.

While export-oriented firms would be most likely affected through the trade disruptions, the effects on their liquidity, workforce, demand, and competitiveness may be more relevant for some firms given the heterogenous impact of COVID-19. Not all firms are equally affected within each of these segments. We aim to quantify the size of the COVID-19 impact. Some firms are well-prepared to respond to the initial shocks and drive the economic recovery, while others may be more-constrained to react during pandemics and similar crises. For instance, the possession of adequate financial reserves limits the financial obligation of a firm in case of financial crisis without creating obligations which may lead to bankruptcy or liquidation. The 2008 financial crisis highlighted the need for more robust financial capital for firms to withstand systemic events with prolonged uncertainty (Spatt, Citation2020). The lessons learned from the 2008 financial crisis contributed to capital restructuring of firms which might be helpful for overcoming the shocks caused by the current pandemic. We aim to identify the main obstacles of export-oriented firms in each segment during and after COVID-19 crisis.

3. Data and methodology

The Finance Think–Export-oriented Business Climate Survey on COVID-19 Impact (FT–XBCS–COVID19) was fielded in a computer-assisted and telephone-assisted form between October 1st and October 23rd, 2020.Footnote4 Initially, we sent the survey to 390 firms in North Macedonia allowing them to self-select as an export-oriented business at the beginning of the survey, otherwise they exit the survey. The initial response was supplemented with telephone interviews targeting the largest exporters in North Macedonia. Our attempt was to capture the largest possible exporters’ share of the value-added to the Macedonian GDP. The survey was voluntary, without financial compensation, while participants were informed that their responses were confidential and only aggregated results would be published.

The survey was completed by 73 export-oriented firms resulting in 19% response rate. The sample is biased towards larger exporters which constitute 63% of the sample. To check the representativeness of our sample, in absence of data on the structure of the population of export-oriented firms in North Macedonia, we leverage the sample statistics of the Enterprise Survey 2019 (ES2019) conducted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB) and World Bank Group (WBG).Footnote5 We extract a sub-sample of the ES2019 taking the firms which reported positive (direct) export share and classify our and ES2019 sample according to the ES2019 criteria. shows that our sample has similar characteristics as the ES2019 sample. In our sample, small exporters and exporters providing other services are under-represented at the expense of larger and manufacturing exporters, with 11% and 9.6% comparing to the ES2019 numbers 23.7% and 28.9%, respectively. Our survey’s regional dispersion almost replicates the ES2019’s one. Drawing from the ES2019 (stratified) sampling design, we apply the ES2019 weights (under the median assumption)Footnote6 to make inferences about the whole population.Footnote7

Table 1. Survey characteristics.

We augment the survey data with 2019 financial statements data. We report descriptive statistics of selected variables in (Appendix). The exporters in the sample on average exist over 20 years and employ 448 workers per firm, with dominantly export-oriented business (over 70% of their revenue). A 51% of the firms are greenfield, brownfield and joint venture types of investment, while the rest is completely domestic. The revenue growth rate in the past 5 years averages 22.4%, while profitability, investment and capital growth approximate 15%.

To evaluate how firm characteristics shape growth movements and expectations of growth of various dimensions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we use the following regression model:

(1)

(1)

where the dependent variable,

is the difference between reported growth rate during COVID-19 and reported average growth rate before COVID-19 for each firm

for each dimension (revenue, profitability, investment and employment) or the difference between reported expected growth rate for the following year and reported growth rate during COVID-19 for each firm

for each dimension. We regress the dependent variables on five sets of variables controlling for different firm characteristics. We provide detailed description and basic statistics of the variables in and A3 in the Appendix. The first set of variables (

) refers to the supply-chain perspective. To measure the sectoral and geographical (input) exposure, we create two dummy variables, input_manufacturing and EU-import, respectively. We expect those heavily exposed to certain sector (manufacturing) and region (EU) to have greater deceleration in growth rates during COVID-19 due to the prolonged administrative closings, especially in the EU. Additionally, we define three variables to assess the significance of procurement disruptions in driving COVID-19 growth rates: the ratio of inventory over assets, input substitution and import replacement. We expect those with higher inventory levels, with possibility to substitute inputs from domestic market and with possibility to replace their disrupted imports to better weather the crisis and experience lower drops in growth rates. The second set of variables (

) refers to the access to finance perspective. We define three ratios to measure the liquidity constraints of firms: capital to assets ratio, cash and other short-term financial investments to assets ratio and debt to assets ratio. We expect the firms with higher levels of capital and cash reserves, as well as greater access to debt markets to cushion the COVID-19 liquidity shocks and experience lower drops in growth rates.

Table 2. Demography of the changes in key firm variables during COVID-19.

The third set of indicators () refers to the human capital perspective. To measure the labour market constraints, we define three dummy variables with respect to firms’ difficulties to find low-skilled, medium-skilled and high-skilled workers: LS workers, MS workers and HS workers, respectively. We expect firms facing greater constraints on the labour market would suffer more during the pandemic. Additionally, we create a dummy variable labour intensity which represents the importance of labour costs in total costs of firms. We expect labour-intensive (less-automated) firms to experience greater deceleration in growth rates. The fourth set of indicators (

) refers to the demand perspective. To measure the sectoral and geographical (output) exposure, we create two dummy variables, output_manufacturing and EU-export, respectively. We expect those heavily exposed to certain sector (manufacturing) and region (EU) to have greater deceleration in growth rates during COVID-19. Moreover, we create a dummy variable, demand shock, to capture the firms more exposed to demand shocks. It is expected those firms to suffer more during the crisis. The final set of indicators (

) refers to the competitiveness perspective. We define two variables: output price and operating profit to assets ratio. We expect the firms with ability to increase the prices during the pandemic and higher operating profit to assets ratio to better withstand the pandemic. Finally, we control for the size, age, export share and investment type. We estimate EquationEquation 1

(1)

(1) using OLS method with robust standard errors for each dimension (revenue, profitability, investment and employment) before and (expectations) after COVID-19 resulting in eight regressions (4 × 2).

4. The COVID-19 impact on export-oriented firms in North Macedonia

4.1. A ‘demography’ of the impact

As the literature suggests, the propagation effects of COVID-19 are heterogenous and widespread across many sectors and countries. Our initial attempt is to provide descriptive analysis of the impact with respect to some firm characteristics which make firms prone to significant growth losses during COVID-19 and which support strong recovery after the pandemic ends. We classify exporters according to the turnover, size, ownership, age, export share, labour intensity and sector essentiality during lockdowns. We analyze the impact across the following dimensions: revenue, profitability, investment, capital, debt, employment and salary growth. Additionally, we observe the sectoral effects on the same dimensions before, during and after COVID-19.

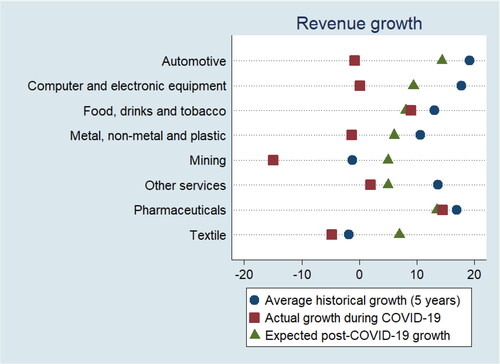

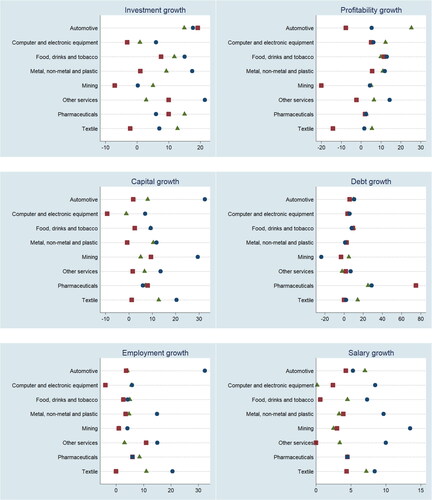

To assess the impact of COVID-19, we have asked exporters the following set of questions for each dimension: 1) What is the 5-year average annual growth before the start of the pandemic?; 2) What is the growth in the first 3 trimesters of 2020 comparing to the same period last year?; 3) What annual growth do you expect for the next calendar year?Footnote8 presents the difference in growth rates across the dimensions ‘before-during’ and ‘during-after’ COVID-19.

COVID-19 caused significant deceleration in revenue, profitability, investments, capital, employment and salary growth. The revenue, profit and investment growths slowed down by 8.9, 6.6 and 9.6 percentage points comparing to their historical growths, respectively. Such declines are clearly related to the dwindling demand and the lockdown during the spring of 2020, while the decline in investment growth is a reflection of the ‘wait and see’ position that firms attained amid the negative shock. We observe the greatest decline in capital growth, while no acceleration in debt growth. This evidence suggests that exporters rationalised through cutting their long-term investments slowing down the capital growth to weather the pandemic shock and maintained their debt growth rates at their historical levels.Footnote9

Since exporters were extensive employers in the labour market in the past, averaging 17.6% annual employment growth, the pandemic severely affected employment and salaries growth, however the rates never reached negative growth. Еxporters expect significant rebound in revenue, profitability, investment and capital growth rates in the following year, while debt, employment and salaries growth rates are likely to stay on their pandemic levels. However, the expected rebound in revenue, investment and capital is not full, i.e. is not expected to reach the pre-pandemic level, which is an articulation of the high uncertainty firms were operating in during the surveying.Footnote10 Such hesitation is further reflected into the expectation of no-growth jobs and salaries over 2021.

The recent empirical evidence shows that smaller firms would be the most severely hit by the pandemic (e.g. Ding et al., Citation2020; Ramelli & Wagner, Citation2020). However, our results show that both SME and large exporters, regardless of their turnover levels, similarly suffered during the pandemic with respect to their revenue, investment, capital, employment and salaries growth rates. The notable exception is the greater drop in investment, capital and salaries growth among the SME exporters compared to the drop in rates of large exporters, which may imply that SME exporters are yet more vulnerable which imposes more difficulties in their coping with the crisis. This is likewise reflected in the differences between SME and large exporters in the post-COVID-19 period: large exporters expect significant rise in post-COVID-19 revenue, profit, investment and employment growth rates, while SME exporters would keep their pandemic rates. All exporters are confident regarding their re-capitalization capacities and would not search for additional liquidity on debt markets. Finally, large exporters expect significant acceleration of employment growth, while those with less than 10-million-euro turnover expect a slight acceleration of salaries growth.

The foreign and domestic-owned exporters experience similar declines in investment and employment growth rates during COVID-19. However, foreign exporters’ revenue and capital growth declines are significantly larger compared to the domestic exporters’ ones. The drop in revenue growth is 14 percentage points, while the drop in capital growth is 16.7 percentage points for foreign exporters. They likewise experienced deeper decline in jobs, but shallower decline in salaries. This may suggest that foreign-owned exporters were less reluctant to fund revenue declines and salaries maintenance from own reserves, likely in an expectation of quicker rebound. Indeed, after COVID-19 period, foreign exporters expect rebound in their revenue, profitability and capital dimensions, and not in investment, while domestic would increase capital and investment growth rates.

Additionally, the period of existence on the Macedonian market plays a significant role in explaining the resilience to the COVID-19 impact. Exporters present on the market more than 20 years suffer less during the pandemic comparing to the ‘younger’ counterparts. The insignificant drop in revenue and profit growth rates suggest that ‘older’ exporters have stable (and potentially more diverse) demand. Finally, exporters aged 10 years and more would regain their pre-pandemic capital and investment growth rates during the following year.

Lastly, exporters’ extent of exposure to foreign markets, labour intensity and essentiality of their activities during lockdownsFootnote11 are important determinants of their resilience during COVID-19. Exporters with moderate and high percentage of exports in their revenues experienced significant deceleration in revenue, profit and investment growth rates, while those more domestically-oriented curtailed only their investment efforts without significant reductions on their revenues and profitability. Nevertheless, the post-COVID-19 boost on revenue, profit, capital and investment growth is expected for those more exposed to foreign markets, which may signify that for those less-exposed the negative shock has been slow or extended. Namely, the ‘low-export-share’ exporters would experience a slowdown in their revenue growth compared to the during-COVID-19 growth rates.

While this result seems surprising, the division of exporters on essential and non-essential provides reasonable explanation. Obviously, more of the domestically-oriented firms come from the essential sectors, such as manufacturing and retail of food, drinks, tobacco and pharmaceuticals, which had steady growth rates during COVID-19 facing an abnormal demand for their products.Footnote12 As expected, the non-essential sectors suffered the most during the pandemic, although they expect to recover with respect to their revenue, profit and capital growth rates in the following period.

Finally, exporters with high labour intensity received stronger hit in their revenue, profitability, investment and capital growth rates, while milder hit in their employment growth rates compared to their counterparts with low labour intensity. This could be also a result of the interference of the government job-retention measure “14.500 MKD per worker”. In absence of such measures, the demise of labour-intensive sectors would translate in augmented disruptions in domestic demand (Carletti et al., Citation2020). However, the expected slower rebound among labour intensive exporters may signify that policy interventions exclusively focused on jobs and wages may keep employment up only artificially (i.e. implicitly entice their plummeting once such aid is over), which then gears the need towards a government support addressing firm’s fundamentals (how to spur investment and revenues). Subsequently, exporters’ attempt to retain their employees put pressure on their capital and profit positions. In the following period, those with higher level of technological development (low labour intensity) would drive the recovery in the capital, investments and employment.

4.2. Sectoral disaggregation of the impact

In the next step, we disaggregate the data on sectoral level to provide more granular analysis of the impact. shows the reported revenue growth before, during and after COVID-19 by sectors. The distance between the historical growth rate and COVID-19 growth rate is greatest for the automotive, computer and electronic equipment manufacturers highlighting the most severe impact among the sectors. Their revenue growth rates entered negative territory during COVID-19 and largely rebound after COVID-19 comparing to the other sectors’ growth rates, however they could not reach the pre-pandemic levels. The patterns are similar for the metal, non-metal and plastic industries. The mining sector is severely affected by the crisis reaching −15% revenue growth with modest expected post-COVID-19 growth of 5%. The sectors deemed essential (Food, drinks and tobacco, and Pharmaceuticals) retain their revenue growth rates before, during and after the pandemic. While positive, the revenue growth rates of services exporters dropped compared to their pre-pandemic levels. Finally, the textile industry shows optimistic patterns exiting the negative pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 growth territory in the following period.

We graph the cross-sectoral patterns for the other dimensions in . Automotive sector together with the essential sectors retain its pre-pandemic investment activity besides the significant deceleration of revenue growth. There are two possible reasons. Firstly, this could be potentially related with the swift revival of China’s market, where the automotive sector mainly imports from, which mitigates the supply-chain shocks and retains the investment sentiment despite the sluggish demand. Secondly, the inertia of the investment growth as firms that initiated investments in the previous years continue up to their completion in the upcoming period. The textile sector expects improving investment activity after-COVID-19 period. Automotive, mining and textile sectors are the most severely hit by the crisis in terms of their profit growth. The capital and debt growth patterns are similar across the sectors, except for the pharmaceutical sector where the capital growth is steady and modestly positive, while debt significantly increases during COVID-19, apparently to meet the increasing demand. The employment growth during COVID-19 approaches zero for almost all sectors, while only textile and pharmaceutical sectors show tendencies for improvement in employment after COVID-19. Finally, the salaries growth decelerates for almost all sectors, but remains positive during and after the pandemic.

The general conclusion is that most of the sectors would not recover to the pre-pandemic levels next year. However, the hardest-hit and most-export-oriented sectors, namely: automotive; electronic and computer equipment; metal, nonmetal and plastic sectors tend to bounce back faster in terms of revenue growth. While, mining and textile sectors are likely to maintain their levels during the crisis setting a stepping stone for the post-COVID-19 period. The leading role in investments will rest in pharmaceutical and automotive sectors. Profitability is geared positively for those export-led sectors positioned to take advantage of the post-COVID-19 global boost, such as: other services; pharmaceuticals; metal, nonmetal and plastic; and food, drinks and tobacco sectors.

4.3. Firms’ characteristics relevant for exporters’ resilience

The previous analysis provides insights about the variation generated solely from the FT-XBCS-COVID19 with respect to the different dimensions, however it does not delve how firms’ characteristics explain the variation of different dimensions during and after COVID-19. In the next stage, we uncover which firm characteristics, with respect to the themes (perspectives) defined, are relevant for the resiliency of exporters to the COVID-19 shock and for their recovery after COVID-19. In addition to the FT-XBCS-COVID19 data, we extract data from the exporters’ 2019 financial statements to create continuous variables to explain the variation of our dependent variables to a larger degree. We focus on four output dimensions: revenue, profitability, investment and employment growth. We regress the difference in growth rates before and during COVID-19, as well as the difference in growth rates during and after COVID-19 on various factors within the defined themes (liquidity, supply-chain, human capital, demand and competitiveness), controlling for the age, export share, size and investment type.

reports the results of the eight regressions on revenue, profitability, investments and employment growth changes during COVID-19.Footnote13 Each dependent variable is regressed on the same groups of factors. To examine the relevance of liquidity constraints on COVID-19 impact, we define three ratios: Capital to Assets, Cash and short-term financial investments to Assets and (Long- and short-term) Debt to Assets ratio. The results show that the access to finance plays crucial role in mitigating the COVID-19 impact on revenue, profitability, investment and employment growth. Exporters with high debt to assets ratio suffer less during COVID-19 due to their ability to exploit the access to debt markets in case of liquidity emergency. Similarly, the better capitalised exporters experience lower drops in growth rates, but the greater capital buffer is only relevant to alleviate the drop in investment growth. While we expected exporters with accumulated liquidity (higher cash/assets ratio) to withstand the initial shock on revenue growth, the coefficient is negative and significant at the 10% confidence level. The exporters decided to leverage the enhanced access to debt markets during the crisis rather than to deplete their cash reserves. Acharya and Steffen (Citation2020) argue that firms with higher credit risk increased their cash holdings drawing from credit lines at the beginning of the pandemic to avoid heightened financing constraints later. Possibly, the exporters with lower cash reserves replenished their liquidity through the debt markets to retain their access to finance, suffering less during the pandemic. The post-COVID-19 results clarify the whole picture with respect to the liquidity constraints. The greater reliance on debt markets would keep the post-COVID-19 revenue, profit and employment growth rates at slower pace, while the liquidity buffer would provide swift response to the post-COVID-19 increasing demand.

Table 3. Channels of transmission and changes in key firm variables during COVID-19.

The supply chain disruptions reflect on growth rates depending on exporters’ procurement constraints and are more pronounced in exporters with lower inventories, lower substitutability of inputs, lower ability to replace imports, more concentrated sectoral and geographical exposures. On the other hand, we find that exporters with high inventory to assets ratio are severely affected during the crisis with respect to their revenue, profit and investments growth rates. This result suggests that demand shock prevails and exporters suffered due to their increasing costs for inventories management during the crisis. Additionally, the exporters more exposed to the manufacturing sector with respect to their procurements, experienced weaker hit on their profit growth rates, while importers from EU countries encountered stronger deceleration of their profit, investment and employment growth rates. Arguably, the importers from non-EU countries, especially China, suffered less due to the quick acceleration of the Chinese economy after the initial impact. This is in line with Bonadio et al. (Citation2020) who show that the reopening of large economies (such as China) would have significant transmission effects on other economies. The exporters with lower flexibility to replace disrupted imports, with higher manufacturing and EU exposure expect lower post-COVID-19 revenue and profit growth rates. The disrupted supply chain undermines exporters’ confidence to respond to the post-COVID-19 improving demand. The exporters’ inventory capacity and input substitutability help them to overcome supply chain problems and accelerate employment growth. While the EU importers expect slower revenue and profit growth rates, the acceleration is expected with respect to the investments and employment comparing to the non-EU importers.

The primary government and firms’ concern during the crisis was job retention. This issue is especially relevant for labour-intensive sectors where COVID-19 downward pressures on revenues depleted firms’ profits as employees’ costs remained fixed. Moreover, the lack of skilled labour augments the severity of COVID-19 impact. shows that labour-intensive exporters suffered considerably experiencing drop in their revenue and profit growth rates. As literature suggests, the automation reduces susceptibility to labour supply shocks caused by the pandemic (Caselli et al., Citation2020; Chernoff & Warman, Citation2020). Moreover, the difficulties in finding low-skilled workers induce exporters to refrain from downsizing resulting in decelerated revenue and profit growths. Barrero et al. (Citation2020) argue that COVID-19 instigates job reallocation shocks as the portion of workers who lost their jobs would find alternative jobs in other sectors. Given the difficulty in finding new workers, the exporters tend to retain their workers during the pandemic. The exporters constrained in finding medium-skilled workers were less affected during the crisis. One possible explanation could be the capacity of exporters to allow their workers to work from home (WFH). Those more constrained to find medium-skilled workers may have higher WFH capacity, thus making them less affected during administrative closings (Gottlieb et al., Citation2020a). The inability to find appropriate skills does not play significant role in the post-COVID-19 period, possibly due to increase in labour supply as many become unemployed and search for a new job. However, the more capital-intensive exporters would significantly accelerate their investments in the post-COVID-19 period. Skill shortage was existing on the labour market in North Macedonia before the pandemic (see, Petreski & Petreski, Citation2020, forthcoming) while our findings suggest that they augmented the severity of the pandemic impact. Still, it is likely that during the pandemic such pressure has been eased, given market’s propensity for lay-offs and its reduced absorption capacity.

The pandemic caused a significant slump in consumption largely hurting downstream firms. Customers have changed their behavior during the pandemic which may result in persistent demand sluggishness in the following period. To assess firm exposure to demand shocks, we construct variables that measure the firm exposure to demand problems, to specific sector (manufacturing) and to specific region (EU). The results show that firms which reported high importance of the demand problem during the pandemic have significant reduction in their revenue and investment growths. However, if the firm has directed higher percentage of its sales to the EU region, it better sustained its investment activity during the pandemic comparing to its counterparts which largely sell to non-EU countries. The last evidence highlights the positive external shocks which arise from the differential geographical exposures of exporters. In the post-COVID-19 period, the firms more susceptible to demand shocks expect rebound in demand and improved revenue growth rates, however the improvement in demand would not translate in acceleration of profit, investment and employment rates.

Finally, the literature suggests that competitiveness plays crucial role in ameliorating exporters’ capacity to cushion the pandemic shocks, however these shocks may in turn impair their competitiveness in the post-COVID-19 period. We expect exporters which were able to increase their prices during the pandemic and which had higher mark-up (operating profit) would better weather the crisis. shows that the more competitive exporters (with higher operating profitability and increased output prices) suffer less with respect to their revenue, profitability and employment growth rates during the pandemic. As Hyun and Kim (Citation2020) find that firms with higher mark-up fare better during the pandemic. However, the more competitive exporters expect slower post-COVID-19 revenue, profitability and employment growth. This might be an indication of harmed competitiveness in the following period. Fernandes and Tang (Citation2020) argue that export disruptions during SARS epidemic in China had medium-term impact on export and import growth rates. Regarding the controlling variables, the investment type significantly explains the pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 growth rates, while age and export share only the post-COVID-19 growth rates. The greenfield investments in the TIDZ and brownfield investments experienced severe drops in revenue, profit and investment growth rates, however they expect significant rebound in the post-COVID-19 period in the same dimensions. The older exporters would accelerate their sales, investment and employment growth rates in the following period.

In summary, the movements of COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 revenue, profit, investment and employment growth rates are determined by the differential access to finances, supply-chain considerations, human capital constraints, demand shocks and competitiveness. Firstly, exporters leverage debt markets not only to cover the liquidity gap, but also to improve their cash reserves to alleviate their access to finance later, if the pandemic lingers. The higher indebtedness would limit the post-COVID-19 growth rates. Secondly, the geographical exposure and disruptions of imports significantly explain the growth rates during COVID-19. The EU importers suffered more as the virus spread escalated around Europe, however they expect rebound in their investment activities in the post-COVID-19 period. Thirdly, the labour market constraints and labour intensity aggravate the magnitude of the COVID-19 impact on growth rates. The capital-intensive exporters would drive the post-COVID-19 investment growth. Fourthly, besides the significant demand shocks, the exporters are confident that consumption would accelerate in the following period. The EU region arises as a market with more stable (prospective) demand. Finally, the more profitable exporters weather better the crisis suggesting that the competitiveness helps exporters to cushion the COVID-19 shocks, however the deterioration of competitiveness is possible on the long-run.

5. Conclusion

The pandemic slashes the steady export growth rate in North Macedonia imposing significant challenges for exporters and policymakers to revive the economy in the upcoming period. The export slowdown would mean limited contributions to the sectoral and geographical diversification, import coverage and employment growth. Additionally, the COVID-19-triggered trade disruptions exacerbate investment sentiment of exporters. Furthermore, as the developed economies recover the positive shocks would transmit through export-oriented firms to the domestic economy. Thus, stakeholders need to be aware of the constraints that exporters are facing with to support post-COVID-19 economic recovery.

The exporters experienced systematic slowdown in their revenue, profit, investment, capital, employment and salaries growth rates. The sectoral distribution of the impact shows that the Automotive and Computer and electronic equipment sectors suffered more in comparison to the other sectors. The exporters with limited access to finance, import exposure to EU markets, high labour-intensity, export exposure to non-EU markets and lower competitiveness were less resilient to the pandemic shocks, representing the main obstacles they will be facing in the recovery stage.

This study provides valuable insights for researchers, managers and policymakers. Firstly, we map the important channels through which COVID-19 affects exporters. The researchers should account for the multidimensionality of the impact when examining the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. It is evident that liquidity shortage is a typical characteristic of any systemic crisis, however this pandemic instigated significant supply-side shocks expanding the variety of risks to which firms can be exposed. Secondly, managers receive valuable lessons about the importance of geographical risks and technological advancements. The exporters may diversify the geographical risk by expanding towards new markets mitigating the losses caused by the closure of certain markets. Moreover, much heavier reliance on technological development would strengthen the resilience to the risks and restrictive measures prompted by the pandemic. Finally, policymakers could use the empirical evidence to design proper policy actions. Namely, the supply-chain disruptions harm exporters’ competitiveness elevating the production costs. Policy actions directed towards reduction of exporters’ input costs should limit their losses and help them to retain or support their competitiveness. Additionally, the skill shortage arises as a crucial impediment to the post-COVID-19 economic recovery. While the wage subsidies served to support the firms’ liquidity positions and limit the unemployment shock, similar policy actions (such as, training subsidies) may expand the workers’ skills and establish more resilient workforce. Lastly, the COVID-19 crisis highlighted the importance of domestic producers’ preparedness to replace the exporters’ disrupted import. Policymakers could support the domestic producers to seize the potential for connecting with multinational firms present in the domestic market.

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, attention has not been devoted to the endogeneity issues which expectedly arise in the regression analysis. The data constraints and limited sample do not allow for a proper tackling of simultaneity and endogeneity biases. Secondly, the sample is highly biased and underrepresents the service sector. One should be cautious when generalizing and interpreting results on population level besides the correction of the applied weights. Finally, the survey has been conducted before the start or at the beginning of the second wave of COVID-19 spread in North Macedonia. The second-wave-phase and the prolonged COVID-19 crisis may have modified the expectations of the firms.

Notes

1 FISCAST (Citation2016) find a positive net benefit of FDIs for the economy. Additionally, export-oriented firms employ a significant number of workers. According to the data supplied by the Directorate for Technological Industrial Development Zones (DTIDZ), FDIs in the country created over 25.000 jobs, mainly in manufacturing during the period 2007–2020.

2 Similar evidence exists during the SARS epidemic in China by the end of 2005 when Chinese exporters permanently lost part of their customers from abroad (Fernandes & Tang, Citation2020).

3 Fahlenbrach et al. (Citation2020) relate financial flexibility to greater cash reserves, less debt and lower long-term debt over assets ratio.

4 The FT-XBCS-COVID19 contains 39 questions classified into four sections. In Section 1, we ask for general firm information related to its size, industry, region, export and import share, ownership, investment type, age and other, and for firm's uncertainty perceptions with respect to its revenue, profitability, investment, capital, debt, employment and salary growth before and during COVID-19, as well as its expectations in the following period. Section 2 comprises questions related to the constraints faced by export-oriented firms structured according to the affected segments of their businesses: liquidity, supply chain, human capital, demand and competitiveness. Section 3 encompasses questions about potentials of the firms in their capacities to re-adapt, introduce novel production line, augment their production potential, increase their automation level, and target new markets. Finally, Section 4 covers questions related to potential policy actions to support firms' growth and competitiveness through cheaper imports, improved human capital capacity and technological advancements.

5 The ES2019 was conducted to improve the understanding of private sector experiences and perceptions in North Macedonia. The data was collected between December 2018 and October 2019 and the sample was selected using stratified sampling methodology ensuring unbiased selection of firms with respect to the industry, establishment-size and region. For more information, see https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3737.

6 The weights were designed based on assumptions on the number of eligible establishments in each stratum. Based on the median assumption, the eligible establishments are those for which it is directly possible to determine eligibility and those that rejected to answer.

7 The application of weights corrects the importance of the individual observations by the inverse of their probability of selection. We apply the svy command in Stata to calculate the weighted statistics.

8 The uncertainty over prolonged COVID-19 crisis during the survey period was rather low. The optimism generated by the inventors of vaccines implied that the following year might be a ‘COVID-19-free’ year. To simplify the wording throughout the paper, we treat the growth expectations for the next year as a ‘after COVID-19.’

9 This is in line with Beck et al. (2020) who find that firms primarily reduce their investment spending and much less rely on downsizing.

10 The COVID-19-induced uncertainty affects both, firms and consumers, impeding investments, hiring and expenditures on durables (Altig et al., Citation2020).

11 The Macedonian government provided strong recommendations and protocols for individual behavior, as well as decided the temporary suspension (lockdown) of almost all economic sectors. Industries were suspended with the exception of those considered ‘essential activities’ necessary to either survival of the population or to the full operation of the healthcare sector.

12 Balla-Elliot et al. (2020) find that businesses deemed essential are less likely to be temporarily closed.

13 We run OLS regressions with robust standard errors without weight corrections. Additionally, we re-run the same regressions applying the ES2019 weights and the results remain qualitatively similar.

References

- Acharya, V. V., & Steffen, S. (2020). The risk of being a fallen angel and the corporate dash for cash in the midst of COVID (No. w27601). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27601

- Alekseev, G., Amer, S., Gopal, M., Kuchler, T., Schneider, J. W., Stroebel, J., & Wernerfelt, N. C. (2020). The effects of COVID-19 on U.S. small businesses: evidence from owners, managers, and employees (no. w27833). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27833

- Alstadsaeter, A., Bratsberg, B., Eielsen, G., Kopczuk, W., Markussen, S., Raaum, O., & Røed, K. (2020). The first weeks of the coronavirus crisis: who got hit, when and why? Evidence from Norway (no. w27131). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27131

- Altig, D., Baker, S. R., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Chen, S., Davis, S. J., Leather, J., Meyer, B. H., Mihaylov, E., Mizen, P., Parker, N. B., Renault, T., Smietanka, P., & Thwaites, G. (2020). Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (No. w27418. )National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27418

- Aral, K., Giambona, E., & Lopez Aliouchkin, R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: supply chain disruption, wealth effects, and corporate responses (SSRN scholarly paper ID 3686744). Social Science Research Network, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3686744

- Balla-Elliott, D., Cullen, Z. B., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. T. (2020). Business reopening decisions and demand forecasts during the COVID-19 pandemic (No. w27362). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27362

- Balleer, A., Link, S., Menkhoff, M., & Zorn, P. (2020). Demand versus supply: Price adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://VoxEU.Org. https://voxeu.org/article/demand-versus-supply-price-adjustment-during-covid-19-pandemic

- Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 is also a reallocation shock (no. w27137). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27137

- Barrot, J.-N., Grassi, B., & Sauvagnat, J. (2020). Sectoral effects of social distancing (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3569446). Social Science Research Network, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3569446

- Bartik, A. W., Cullen, Z. B., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. T. (2020). What Jobs are Being Done at Home During the Covid-19 Crisis? Evidence from Firm-Level Surveys (No. w27422). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27422

- Beck, T., Flynn, B., & Homanen, M. (2020). COVID-19 in emerging markets: Firm-survey evidence. VoxEU.Org. https://voxeu.org/article/covid-19-emerging-markets-firm-survey-evidence

- Bennedsen, M., Larsen, B., Schmutte, I., & Scur, D. (2020). Preserving job matches during the COVID-19 pandemic: Firm-level evidence on the role of government aid. In GLO discussion paper series (no. 588; GLO discussion paper series). Global Labor Organization (GLO). https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/glodps/588.html

- Bodenstein, M., Corsetti, G., & Guerrieri, L. (2020). Social distancing and supply disruptions in a pandemic. VoxEU.Org. https://voxeu.org/article/social-distancing-and-supply-disruptions-pandemic

- Bonadio, B., Huo, Z., Levchenko, A. A., & Pandalai-Nayar, N. (2020). Global supply chains in the pandemic (no. w27224). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27224

- Buchheim, L., Krolage, C., & Link, S. (2020). Sudden stop: when did firms anticipate the potential consequences of COVID-19? In IZA discussion papers (no. 13457; IZA discussion papers). Institute of Labor Economics (IZA). https://ideas.repec.org/p/iza/izadps/dp13457.html

- Carletti, E., Oliviero, T., Pagano, M., Pelizzon, L., & Subrahmanyam, M. G. (2020). The COVID-19 shock and equity shortfall: firm-level evidence from Italy. In CSEF working papers (no. 566; CSEF working papers). Centre for Studies in Economics and Finance (CSEF), University of Naples. https://ideas.repec.org/p/sef/csefwp/566.html

- Caselli, M., Fracasso, A., & Traverso, S. (2020). Mitigation of risks of covid-19 contagion and robotisation: evidence from Italy. CEPR PRESS: COVID Economics - Vetted and Real-time Papers, May 13, 2020. Issue 17, 174–189.

- Chernoff, A. W., & Warman, C. (2020). COVID-19 and implications for automation (no. w27249). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27249

- Cororaton, A., & Rosen, S. (2020). Public firm borrowers of the US paycheck protection program (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3590913). Social Science Research Network, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3590913

- Davis, S. J., Hansen, S., & Seminario-Amez, C. (2020). Firm-level risk exposures and stock returns in the wake of COVID-19 (no. w27867). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27867

- Ding, W., Levine, R., Lin, C., & Xie, W. (2020). Corporate immunity to the COVID-19 pandemic (no. w27055). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27055

- Fahlenbrach, R., Rageth, K., & Stulz, R. M. (2020). How valuable is financial flexibility when revenue stops? Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. In NBER working papers (no. 27106; NBER Working Papers). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/27106.html

- Fernandes, A. P., & Tang, H. (2020). How did the 2003 SARS epidemic shape Chinese trade? In CESifo working paper series (no. 8312; CESifo Working Paper Series). CESifo. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ces/ceswps/_8312.html

- FISCAST. (2016). Foreign direct investments in North Macedonia: Cost-benefit analysis of the policy for attracting FDIs in North Macedonia. https://www.fiscast.mk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/%D0%A1%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8-%D0%B4%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82%D0%BD%D0%B8-%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%86%D0%B8%D0%B8-%D0%B2%D0%BE-%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%BA%D0%B5%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%98%D0%B0.pdf

- Gottlieb, C., Grobovsek, J., Poschke, M., & Saltiel, F. (2020a). Lockdown accounting (SSRN scholarly paper ID 3636626). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3636626

- Gottlieb, C., Grobovsek, J., Poschke, M., & Saltiel, F. (2020b). Working from home in developing countries. In IZA discussion papers (no. 13737; IZA discussion papers). Institute of Labor Economics (IZA). https://ideas.repec.org/p/iza/izadps/dp13737.html

- Gourinchas, P.-O., Kalemli-Özcan, Ṣ., Penciakova, V., & Sander, N. (2020). COVID-19 and SME failures (no. w27877). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27877

- Hatayama, M., Viollaz, M., & Winkler, H. (2020). Jobs' amenability to working from home: evidence from skills surveys for 53 countries. Policy research working paper; no. 9241. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33753

- Hyun, J., & Kim, D. (2020). The role of global connectedness and market power in crises: Firm-level evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. CEPR PRESS: COVID Economics - Vetted and Real-time Papers. Issue 49, September 18, 2020. pp. 148–172.

- Inoue, H., & Todo, Y. (2020). The propagation of economic impacts through supply chains: The case of a mega-city lockdown to prevent the spread of COVID-19. PLoS One, 15(9), e0239251. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239251

- Koren, M., & Pető, R. (2020). Business disruptions from social distancing. PLoS One, 15(9), e0239113. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239113

- Meier, M., & Pinto, E. (2020). Covid-19 supply chain disruptions. In CRC TR 224 discussion paper series. (crctr224_2020_239; CRC TR 224 discussion paper series) University of Bonn and University of Mannheim. https://ideas.repec.org/p/bon/boncrc/crctr224_2020_239.html

- Ministry of Finance. (2019). Fiscal strategy of North Macedonia for 2020-2022. https://www.finance.gov.mk/files/u6/Fiskalna%20Strategija%20na%20RSM%202020-2022_FINAL_c1_2.pdf

- Morikawa, M. (2020). Productivity of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from an employee survey. In Discussion papers (no. 20073; discussion papers). Research Institute of Economy. https://ideas.repec.org/p/eti/dpaper/20073.html

- Navaretti, G. B., Calzolari, G., Dossena, A., Lanza, A., & Pozzolo, A. (2020). In and out of lockdowns: Identifying the centrality of economic activities. VoxEU.Org. https://voxeu.org/article/and-out-lockdowns

- Paaso, M., Pursiainen, V., & Torstila, S. (2020). Entrepreneur debt aversion and financing decisions: Evidence from COVID-19 support programs (SSRN scholarly paper ID 3615299). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3615299

- Papanikolaou, D., & Schmidt, L. D. W. (2020). Working remotely and the supply-side impact of Covid-19 (no. w27330). National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27330

- Petreski, M., & Petreski, B. (2020). Macedonian labour market in a stalemate: Forecasting occupational and sectoral labour demand. ETF publication. ETF Compendium.

- Pichler, A., Pangallo, M., del Rio-Chanona, R. M., Lafond, F., & Farmer, J. D. (2020). Production networks and epidemic spreading: How to restart the UK economy? ArXiv:2005.10585 [Physics, q-Fin]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.10585

- Ramelli, S., & Wagner, A. F. (2020). Feverish stock price reactions to COVID-19. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 9(3), 622–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfaa012

- Schivardi, F., & Romano, G. (2020, July 18). Liquidity crisis: Keeping firms afloat during Covid-19. VoxEU.Org. https://voxeu.org/article/liquidity-crisis-keeping-firms-afloat-during-covid-19

- Sforza, A., & Steininger, M. (2020). Globalization in the time of covid-19. In CESifo working paper series (no. 8184; CESifo working paper series). CESifo. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ces/ceswps/_8184.html

- Spatt, S. C. (2020). A tale of two crises: The 2008 mortgage meltdown and the 2020 COVID-19 crisis. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 10(4), 759–790. https://doi.org/10.1093/rapstu/raaa019

- Stojcic, N. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on the export competitiveness of manufacturing firms in Croatia. Economic Thought and Practice, 20(2), 347–365.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics of selected variables.

Table A2. Definition of variables.

Table A3. Descriptive statistics and correlations.