?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Balanced gender representation in local political life has been a subject of increasing interest to researchers. This paper, based on a unique database, analyses the representation of women in local representative and executive bodies and its impact on budget transparency (BT) in Croatian local governments. The panel analysis shows that a greater representation of women in local councils has a positive effect on the level of local government digital budgetary reporting. This is in line with gender literature settings and theories that explain BT, suggesting that the greater representation of women helps reduce information asymmetry, increase transparency, and promote government legitimacy. We do not find significant results in regard to women’s representation in local executive functions. A particularly indicative policy implication suggests the aim of increasing the gender balance in local political spheres, especially when deciding on good governance practices and fiscal disclosure requirements.

1. Introduction

Budget/fiscal transparency (BT/FT) increases the visibility of fiscal actions, enabling citizens to influence the efficiency of use of public funds, to demand more government accountability and to reduce opportunities for corruption (Alt & Lassen, Citation2006; Kaufmann & Bellver, Citation2005). Improved BT allows citizens and legislative authorities to engage more efficiently in the budgetary planning and to control and scrutinize spending and execution of budgetary funds, thus reducing opportunities for public resource mismanagement. A good and consistent public scrutiny can reveal the deviations from the planned budget funds, indicating the level of governments’ budget credibility. BT, accompanied by constructive citizen participation, can contribute to a fairer distribution and to better local public goods and services.

Most of the BT studies are focused at the national level of government (e.g., Hollyer et al., Citation2011; Wehner & de Renzio, Citation2013). However, the discourse seems to be changing, giving ever more importance to local governments. The local context of representative democracy is particularly significant because of the more pronounced principal-agent (citizen-politician) relations. It is argued that the most important interactions between citizens and politicians take place at the lowest governments’ levels (Sandoval-Almazan & Gil-Garcia, Citation2012), providing a basis for improving good governance activities (transparency, accountability and trust).

The increased importance of local budget transparency (LBT) can be seen in a growing number of research on the determinants of subnational BT/FT. Based on the previous empirical findings, its main determinants are: (a) economic (e.g. income, fiscal capacity, economic conditions like unemployment rate), (b) political (e.g. political spectrum, election results) (see e.g., Caamaño-Alegre et al., Citation2013; Guillamón et al., Citation2011).

However, we cannot neglect that one of the important factors affecting the level and attitude towards BT has its roots in gender differences. It is recognised that a greater representation of women in local councils and as holders of local executive power affects changes in the power structure and in the functioning of local governments (Medina & Antonio, Citation2015). Beck (Citation2001) found that local councillors (both male and female) confirmed that female councillors were more accessible to their electorates, open to suggestions and more responsive than male councillors. It is considered that women in important political positions promote the inclusion and participation of citizens and provide better and more constructive interaction and communication than their male counterparts (Fox & Schuhmann, Citation1999). One should also note the number of stereotypes, e.g. that women do better in education, government affairs and social services, as these settings are mostly female dominated (Eagly et al., Citation1995). These stereotypes can influence the behaviour and actions of women in local political life – especially as councillors and heads of the local executive – where they are expected to adopt a more transparent way of governing and an inclusive modus operandi (De Araujo & Tejedo-Romero, Citation2018).

Accordingly, females could contribute to the greater LBT and thus influence the positive changes. It is why we explore the impact of women’s representation in local politics on the level of LBT, using the Open Local Budget Transparency index (OLBT) developed by the Institute of Public Finance and measured as annual online availability of five key budgetary documents (budget proposal, enacted budget, mid-year and year-end reports, and citizens budget). Documents are chosen in accordance with the best international practices on BT (see OECD, Citation2002), and their availability provides citizens with insight into the planning and spending of local budget funds through all phases of the budgetary process.

To our knowledge, only two studies (De Araujo & Tejedo-Romero, Citation2016, Citation2018) have investigated the impact of women’s representation in local politics on the level of local government transparency. However, they used a wider measure from the Transparency International Spain.

To fill this gap, and having in mind that each of our five documents has relevance and purpose within the budget process (see Ramkumar & Shapiro, Citation2010), we focus exclusively on the OLBT. The originality of this paper lies in its use of a new and unique measure of LBT and a unique panel dataset of 556 Croatian LGs during the 2014–2019 period. It contributes to the BT and gender research field literature by being one of the first attempts to explore the effect of women representation in local representative and executive on the level of LBT in one CEE and the newest EU member country.

The results confirm that a high representation of women in local councils leads to higher levels of LBT. The following sections include the theoretical framework and previous empirical findings, the methodological framework (with presentation of variables), the research results, discussion and conclusion.

2. Theoretical background and previous empirical findings

2.1. Theoretical background

Lacking precise definitions, budget transparency (BT) and fiscal transparency (FT) are often used interchangeably. According to Alesina and Perotti (Citation1996), due to the lack of a unique and unambiguous BT/FT definition, they are challenging to measure. Kopits and Craig (Citation1998, p. 1) define FT very broadly “as openness toward the public at large about government structure and functions, fiscal policy intentions, public sector accounts, and projections. It involves ready access to reliable, comprehensive, timely, understandable, and internationally comparable information on government activities”. Similarly, the OECD (Citation2002, p. 7) defines BT as “the full disclosure of all relevant fiscal information in a timely and systematic manner”. The World Bank (Citation2013, p. 1) defines BT much more narrowly as “the extent and ease with which citizens can access information about and provide feedback on government revenues, allocations, and expenditures”.

Building on these definitions and taking the view that BT should be more narrowly defined (focused only on budgets) and FT more broadly (including information about government structure and functions), this paper is oriented towards the BT defined as the online availability of budgetary information, i.e. the possibility for citizens to obtain complete, accurate, and timely information about local budgets.

The analysis of women's representation in local political life and its impact on local government accountability and transparency is based on two theories. Social role theory explains how the existing (imposed) social structures within a particular culture and society contribute to the constant development of gender stereotypes (Eagly, Citation1987). It postulates that certain gender stereotypes are deeply rooted in the different social roles assigned to men and women within a society. Women are traditionally homemakers and oriented toward domestic roles (e.g., nurses or kindergarten teachers), with attributes such as warmth and compassion, while men are mostly breadwinners, with accompanying descriptions such as task achievers and assertiveness (Eagly, Citation1987). Women and men adapt to these gender roles by acquiring and developing the specific knowledge and skills needed to perform these roles, adjusting attitudes and behaviours according to the gender role requirements (Eagly et al., Citation2000). Gilligan (Citation1982) emphasised that social norms and roles influence the different men’ and women’ understandings and interpretations of realities, ultimately adopting different systems of values and behaviours. Women are perceived to be more compassionate and to care more about others; to have a stronger sense of community and justice (Hamidullah et al., Citation2015); to be more accessible, cooperative and open (Merchant, Citation2012); more socially and politically egalitarian (Eagly & Johannesen-Schmidt, Citation2001).

According to expectation states theory (see Berger et al., Citation1966; Webster & Driskell, Citation1978), a society's cultural beliefs about social roles and categories at the macro level influence the attitudes and behaviours of the individual, who mimic the status characteristics and structures previously formed at the macro level. Such movements produce social stratifications, especially at the individual (micro) level, where social inequalities emerge, making women in the social environment less likely to be accepted as leaders (Correll & Ridgeway, Citation2006). Additionally, such gender roles and characteristics of women's leadership, such as openness, compassion, inclusion and transparency, affect the improvement in governance (Del Sol, Citation2013). Women are also more likely to involve traditionally excluded and vulnerable groups in decision-making and budgetary processes and procedures (Beck, Citation2001; Fox & Schuhmann, Citation1999).

We study the role of women in BT as supported by the social-role and expectation states theories, but we are not neglecting the agency and legitimacy theories useful for explaining information asymmetries in the political context and representing the basis for the selection of our control variables. Principal-agent relationship (agency theory; agency dilemma) can be seen as a contract in which one or more individuals (principals) hire a third party (agent) to perform and provide certain services on their behalf (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). The principals give the agent some authority to make decisions on their behalf. However, if both the principals (voters) and the agent (politicians) are utility maximizers, the agent might not always work for the principal's best interests, but rather for his own self-interest. This is evident in the presence of assymetrical information, when, unlike principal, agents have much more knowledge and information in decision-making processes. Therefore, citizens bear (1) the direct cost, including all the tangible and intangible rewards of politicians (their remunerations) and (2) indirect costs from the mismanagement and poor performance of agents and their mistakes (Lane, Citation2013). According to Holmström (Citation1979), asymmetry of information arises because individuals cannot observe each other's actions, implying the necessity of greater monitoring of actions. Higher transparency helps to solve the principal-agent problem and increases the efficiency of resource allocation (Holmström, Citation1979).

The source of legitimacy theory lies in corporate social responsibility (CSR) literature and organizational legitimacy. Dowling and Pfeffer (Citation1975, p. 122) define the organizational legitimacy as "a condition in which the value system of a particular unit coincides with the value system of the broader social environment of which the unit is a part“. Suchman (Citation1995, p. 574) perceives the legitimacy as a “generalised perception or assumption that the agent's actions are desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions”. Although it arose from CSR, the same arguments apply to governmental legitimacy. In the context of government transparency (including F/BT), this theory seeks to explain the behavior of politicians in meeting social demands for greater transparency and accountability. Since they can be sanctioned for disrespecting such social values, opportunistic politicians reveal more information to ensure their political survival. If government legitimacy is disrupted, politicians increase transparency to restore citizen confidence and the legitimacy of elected public officials, thus securing a good reputation of the government (De Araujo & Tejedo-Romero, Citation2016). Fiscal transparency, as a separate narrower segment of government transparency, particularly enhances the legitimacy of government, given its instrumental nature to contribute to improved governance. This is best represented through: (a) its incentive to help divert the focus of attention from inputs to outcomes, and (b) enhancing the credibility of fiscal policies, giving political and economic actors some power in predicting fiscal activities, making them more effective in making decisions (De Simone, Citation2009; Heald, Citation2003).

The local executive directs its operations and activities in accordance with the standards and norms existing in the social environment of the municipality. Local governments resort to the greater disclosure of information if there are societal expectations and pressures for greater accountability and transparency (Deegan, Citation2002). These social expectations in line with the abovementioned expectation states and social role theories see women as more open, accessible, and transparent, expecting them to reduce information asymmetries better than men. Rosenthal (Citation2000) argues that women are more likely to resolve the agency problem as they are more open and willing than men to have their actions monitored and scrutinised. Greater representation of women in politics “helps lend legitimacy to governing institutions” (Shreeves & Prpic, Citation2019).

We use social role and expectation states theories as an essence underpinning to support the arguments about greater social and ethical sensibility of women.

2.2. Previous empirical findings

While there is a growing empirical examination of the determinants of local budget/fiscal transparency (e.g., Alt and Lassen, 2006; Esteller-Moré & Polo Otero, Citation2012), only a few authors have incorporated the gender variable. De Araujo and Tejedo-Romero (Citation2016), using a sample of the 100 Spanish municipalities, found a positive impact of the greater representation of women among local executives and representatives on the level of government transparency. They used a dependent variable from TI Spain that covers several areas of government transparency (fiscal, corporate, social, procurement and contracting). De Araujo and Tejedo-Romero (Citation2018) built on their earlier work, used the same sample and dependent variable, and obtained similar results. Using additional control and moderation variables they found that when women represented the absolute majority in the local council, transparency was reduced, while when they were represented in moderation, the variable had a positive effect on transparency. They showed that the representation of women had a positive effect not only on general government transparency but also exclusively on the economic and financial transparency. Tavares and da Cruz (Citation2020) did not explore the gender impact on transparency but considered the more extensive context of factors influencing the transparency of Portuguese municipalities, using the data from TI Portugal (including economic and financial transparency dimension). They showed that municipalities with female mayors displayed significantly higher levels of transparency.

The gradual increase in the representation of women in politics in general is argued to have brought about many changes in common activities and governance practices, especially in the more rational allocation of public funds, greater openness and reduction in corrupt practices (Vermeir & Van Kenhove, Citation2008).

Based on above explained theoretical framework and empirical findings, it is worth investigating this underexplored topic in a more extensive empirical context. This study hypothesises that there is a positive significant relationship between women’s political representation and the level of OLBT.

3. Research design, data, and methods

3.1. Sample and Croatian context

Researching all Croatian local governments we create a strongly balanced panel, with six years of observations in 556 local governments (428 municipalities and 128 cities), yielding a total of 3336 observations for each variable.

To briefly explain, Croatia is divided into: regional (20 counties) and local governments (128 cities and 428 municipalities).Footnote1 Municipalities and cities carry out activities of local importance that directly meet the needs of citizens (e.g., utilities, primary health care, childcare, social care, spatial and urban planning, fire and civil protection) while counties perform tasks of regional importance (e.g., economic development, transport infrastructure, maintenance of public roads). All of them have representative and executive bodies - municipal council, city council and county assembly as representative, and municipality head, city mayor and county prefect as executive bodies. They are all elected directly, by secret ballot.

There are two basic laws that regulate BT in Croatia: Budget Act and Act on the Right of Access to Information. Local government budget, the same as the national budget, has to be adopted and implemented, inter alia, respecting the principles of unity and accuracy, balance, universality, budget specification or appropriate classifications, sound financial management and transparency. These laws regulate the publication of three budget documents – the enacted budget, the year-end and mid-year reports. In order to strengthen citizen participation in budgetary processes, the Ministry of Finance recommends timely publication of a budget proposal and of a citizens budget, so that citizens are more quickly and easily acquainted with basic budget concepts and planned activities.

The representation of women in local councils is below 20%, which is significantly lower than the European average of 32% (Shreeves & Prpic, Citation2019). This is not surprising since in Croatia, economic, political and social power and the distribution of resources are generally unbalanced between men and women, which puts women at a great disadvantage, especially in the labour market (Bodiroga-Vukobrat & Martinović, Citation2017). Therefore, as part of the EU's gender equality strategy, Croatian legislative and strategic efforts seek to create a more gender-balanced environment in all institutional bodies (in public and private life). The Act on Gender Equality, Art. 15, clearly states that all levels of government must consider equal gender representation, especially political parties, when compiling candidate lists for elections. The central government has imposed an obligation on local governments to introduce gender quotas on candidate lists in local elections. However, this measure has not significantly contributed to a greater representation of women, perhaps because the formal fulfilment of quotas is not enough. The selection of female candidates in local elections depends primarily on their assigned hierarchical position on the candidate electoral list (Bodiroga-Vukobrat & Martinović, Citation2017). This may be reminiscent of the promotion of gender diversity in the workplace, which is often only of a formal nature, without proper implementation, reflecting the government’s resistance to genuine change (Greve & Argote, Citation2015).

3.2. Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this paper is the Online Local Budget Transparency (OLBT) of the Institute of Public Finance (IPF), calculated for all Croatian local governments since 2014. The OLBT presents the availability of five key budget documents on the official websites of local governments. Depending on the availability of these documents, each local government may have a level of BT from 0 to 5 each year. The documents were selected in accordance with international fiscal transparency practices (see e.g., OECD, Citation2002) and with the Croatian legislative framework and recommendations. Accordingly, key budget documents are:

Year-end report

Mid-year report

Enacted budget

Budget proposal

Citizens budget

Each November and December, IPF researchers are searching for mid-year and year-end reports, and in February and March, for the budget proposal, enacted budget and citizens’ budget on web sites of all local governments. This timing leaves enough time for local governments to publish the required documents. E.g., the executive should submit a mid-year report proposal to the representative government by September 15, while the site search begins on November 1. Likewise, the draft budget proposal should be submitted to the representative government by November 15, while the search for the publication begins on February 1.

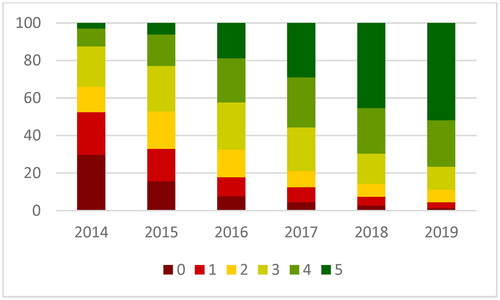

There are large differences among local governments in the levels of their BT, but improvements are visible in annual measurements (Ott et al., Citation2020) – e.g., in the 2014 cycle, almost 30% of local governments did not publish any of the five documents, while in the 2019 cycle, more than half of them published all five documents ().

Figure 1. Budget transparency of Croatian local governments as measured by the OLBT, 2014–2019, in %.

Source: Author based on Ott et al. (Citation2020).

For clarification, e.g., the OLBT 2019 includes the 2018 year-end report, 2019 mid-year report, and 2020 budget proposal, enacted budget and citizens budget (all five documents should have been published in 2019).

3.3. Independent variables of interest

The independent variables in this paper relate to female representation in representative and executive local politics. The women_councillors variable denotes the representation of women in local councils (in percentage), while the female_mayors dummy variable indicates whether the local executive is headed by a woman.

The data refer to the 2013 and 2017 local elections (the source is State Electoral Commission). In these two election cycles, the average representation of women in the local representative bodies increased by almost 8% (from 17.3% to 25.2%). However, women still represent only a quarter of all representatives. Regarding local executives, in both election cycles, less than 10% of all mayors/municipal heads are female (6.5% in 2013; 9% in 2017).

3.4. Control variables

3.4.1. Voter turnout

It is argued that a larger electoral turnout indicates a greater interest of citizens in government decisions and activities (Caamaño-Alegre et al., Citation2013). On one hand, when voter turnout is lower, government activity is less transparent (Guillamón et al., Citation2011), on the other, higher voter turnout denotes more active citizens with greater interest in local political life. In regard with the agency relationship, a local government will have an incentive to act more transparently if it knows that citizens are discussing and monitoring its behaviour. Therefore, in this paper, voter turnout can be perceived as a proxy for active citizenship.

This variable represents citizen participation in the local elections of 2013 and 2017 as a percentage (the source is State Electoral Commission).

3.4.2. Left wing

A large number of authors examine the relationship between transparency and the political ideology of government. Although the results vary according to the context, several studies have confirmed a significant and strong relationship between fiscal/budget transparency (F/BT) and the political ideology of the council majority and/or incumbents (e.g., Caamaño-Alegre et al., Citation2013; Del Sol, Citation2013). Some theoretical assumptions suggest the importance of including this variable, such as the principal-agent model by Ferejohn’s (Citation1999). His argument is that left-wing governments defend a larger public sector, thus they are expected to enhance transparency.

Political ideology represents a dummy variable (the value 1 if the executive comes from the left political spectrum, and 0 otherwise). The source of data is State Electoral Commission.

3.4.3. Residents' income per capita

Some features of the local area, such as the level of income of the population, may also affect the propensity to publish budget information. Ho (Citation2002) stresses that local governments with residents with low per capita (pc) income are less likely to adopt modern online information disclosure, given the weaker demand for web-based services. Municipalities with high pc incomes face greater demand for accountability and political monitoring (Ingram, Citation1984). With regard to the principal-agent relationship, citizens with higher incomes expect quality public services, greater accountability and transparency of public funds, as they pay more taxes than those with lower incomes (Giroux & McLelland, Citation2003; Piotrowski & Van Ryzin, Citation2007). The citizen wealth variable has been examined in several studies, showing a positive and strong relationship with F/BT (e.g., Lowatcharin & Menifield, Citation2015; Styles & Tennyson, Citation2007).

Residents’ average annual pc income for each local government is obtained from the Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds.

3.4.4. Fiscal capacity per capita

According to Christiaens (Citation1999), the greater financial capacity of local government sends voters a signal of good governance, allowing incumbents to improve their legitimacy and likelihood of re-election. In line with legitimacy theory, higher local government taxation can encourage municipalities to become more accountable and, in their quest for legitimacy, publish more fiscal information on how the revenues (collected from taxes) are spent. Several authors have empirically confirmed the positive relationship between municipal wealth and F/BT (e.g., Guillamón et al., Citation2011; Laswad et al., Citation2005).

In line with previous measurements of municipal wealth, this variable represents the local government fiscal capacity pc, measured as operating revenues minus grants. The source is the database of the Ministry of Finance.

The unemployment rate is used as a proxy variable for the economic conditions in the local community to analyse the relationship between the municipal economic situation and BT (Cuadrado-Ballesteros, Citation2014). As in the case of residents’ income pc, in line with the agency theory, employed citizens expect quality public services, greater accountability and transparency of public funds as they pay more taxes than unemployed persons. Previous empirical findings confirm that high unemployment rates are associated with low levels of transparency (e.g., Caamaño-Alegre et al., Citation2013; Tavares & da Cruz, Citation2020).

We use unemployment rate for each local government, as registered by the Croatian Employment Service.

3.5. Research model

The main goal is to analyse the impact of women's political representation on OLBT. We expect to obtain comprehensive and robust results from cross-sectional analysis (Cuadrado-Ballesteros, Citation2014; De Araujo & Tejedo-Romero, Citation2016). The panel database consists of a 6-year period (time-series dimension) and 556 Croatian local governments (cross-sectional dimension), providing a significant number of observations (3336) and many degrees of freedom and allowing an efficient model setup.

The specification of the model for testing the hypothesis is as follows:

where

denotes time-invariant fixed effects,

and

are vectors of the estimated parameters of the variables of interest,

-

are vectors of the estimated parameters of control variables, and ε is an error term.

In accordance with the count-data characteristics of the dependent variable and the existing panel database, we apply Poisson panel data regression analysis (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2013; Hausman et al., Citation1984), suitable for a count dependent variable that takes nonnegative integer values, as is the case in this study (the number of budgetary documents published). Poisson regression is sometimes characterized by weak exogeneity, implying that the parameters of interest can be recovered from the conditional model only. However, we also run fixed-effects Poisson panel regression model which can handle endogenous regressors under weak exogeneity assumption.

Because Poisson models often suffer from overdispersion issues (Greene, Citation2002) that affect model interpretation, we conduct summary statistics for the dependent variable, showing that the variance (2.71) is lower than the mean (3.07), which rejects the existence of overdispersion. Therefore, the obtained results can be interpreted with default standard errors.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive analysis

presents the basic descriptive statistics for all observed variables, first continuous (panel A) and then discrete (panel B). For the variables of interest, in the observed 6-year period (two election cycles), the percentage of women in the local council varies considerably among local governments – from 0% to 67% – but is generally still low, with an average of 21%. In regard to the dummy variable female_mayors (panel B), on average, in both election cycles, only 8% of local incumbents are women. As noted above, such a small percentage precludes a robust analysis of the impact on BT. However, even such a figure has policy implications that support the importance of adopting policies to promote the greater participation and representation of women in the local executive. The dependent variable, OLBT, shows that in the period 2014–2019, on average, 26% of local governments published all key budgetary documents, while 10% did not publish any of requested documents ().

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

The control variables also deserve some comment. Although electoral turnout varies across municipalities, the mean value for the two election cycles observed is relatively small (less than 53%), leaning towards voter apathy. This is in line with Kersting’s (Citation2015) observation that the political participation of local residents in Croatia is among the lowest in Europe.

Additionally, municipal development – in terms of population wealth (income pc), municipal wealth (fiscal capacity pc) and the economic condition of the local government (unemployment rate) – differs considerably among local governments, confirming the problem of unequal regional development (Klarić, Citation2017), spatial differences and the usual fragmentation of socioeconomic dimensions in Croatian regions (Nejašmić & Njegač, Citation2001). In regard to the political spectrum of local executives in the last two election cycles, there are significantly fewer local incumbents from the left spectrum (27%) than from the right wing (73%).

4.2. Panel data regression analysis

To examine the suitability of the fixed-effects or random-effects model, we first conduct the Hausman test. The results (χ26 = 65.54, p = 0.000) indicate that in our case, the fixed-effects panel model is the most appropriate. However, by decomposing the standard deviation into between- and within-components, the data characteristics point to a random-effects model since the data show larger between- than within-effects among the independent variables. Accordingly, in , we present both fixed- and random-effects results. According to Baltagi (Citation2005), cross-sectional dependence and serial correlation are not an issue in micro panels (with only a few years of observation and a large number of cross-sectional subjects), but they become a problem in macro panels with a time dimension of over 20–30 years. We also perform a correlation matrix of the explanatory variables, which indicates a multicollinearity problem between the income pc and unemployment rate variables. We consider this issue when setting up the model.

Table 2. Determinants of local government budget transparency – panel data Poisson regression.

presents the results of panel Poisson regression for both fixed and random effects using two different model specifications in accordance with the presence of multicollinearity issues (income pc and unemployment rate). In all these cases, the results show that the percentage of female councillors is significant at 1% (5% in the first specification) and positively related to our dependent variable of LBT ( = 0.007, p = 0.000). Given the theoretic foundation of Poisson regression (eβ1 = e0.007 = 1.007), this can be interpreted as: a 1% rise of female councillors representation is associated with an increase in the OLBT by a factor of 1.007, or alternatively, a 1% rise of female councillors representation is associated with an increase in the OLBT by 0.7% (1.007–1 = 0.007*100 = 0.7%). We do not find a significant relationship between female mayors and OLBT. It should be noted that the representation of female mayors in the Croatian local executive is extremely low, less than 8%. As Derks et al. (Citation2016) suggest, in a low gender balance environment, some female leaders may take on male leadership characteristics to cope with social identity threats (the queen bee phenomenon).

Our hypothesis about the positive relationship between women's political representation and OLBT is confirmed at the level of the local representative body. A high share of female councillors has a positive effect on the level of OLBT. This is consistent with the above-presented social role and expectation states theories, pointing out that women bring new perspectives and attitudes towards budgetary processes and information disclosure (Beck, Citation2001; Fox & Schuhmann, Citation1999). As argued by Rosenthal (Citation2000), female politicians find it easier to address information asymmetry, as they have a more transparent and inclusive approach towards their electorate. Since transparency and accountability are common combinations of good governance, by proactively disclosing information, women may enhance the legitimacy of their actions and allow them to be monitored (Rosenthal, Citation2000). Our results are in line with previous empirical findings on the impact of women's political representation on local government transparency (De Araujo & Tejedo-Romero, Citation2016, Citation2018).

We also calculate the effect of female councillors’ representation on mandatory and voluntary disclosure separately. Using the same variables as in the main model, we transform the dependent variable OLBT – so we have a dummy if the local government publishes all voluntary documents, and a dummy if it publishes all mandatory documents. The panel logistic regression results confirm the Poisson results, with a slightly stronger parameter coefficient regarding the voluntary disclosure. This confirms the previous theoretical assumption that women are more proactive in disclosing information, as found both in mandatory and voluntary segments of BT. These results are available upon request.

Regarding the control variables, income pc and the unemployment rate show the strongest and most consistent results in both the fixed- and random-effects models. The results indicate that high residents' income pc, as a proxy for citizens' wealth, contributes to high BT levels. Namely, it is argued that local governments with high pc incomes face a greater demand for accountability and political monitoring (Ingram, Citation1984), which is why they prove their legitimacy through transparency channels. The unemployment rate variable, as a proxy for local economic conditions, shows that high unemployment also has an adverse effect on transparency. This is backed up by previous findings (e.g., Caamaño-Alegre et al., Citation2013; De Araujo & Tejedo-Romero, Citation2016).

Regarding the participation in local elections, as measured by voter turnout, we can conclude that low turnout leads to high levels of BT ( = −0.011, p = 0.000, in the RE model). In fact, it is argued that a low electoral turnout often indicates voter apathy, and opportunistic incumbents increase transparency to stimulate the electorate and increase the likelihood of their re-election by obtaining a larger pool of possible votes (De Araujo & Tejedo-Romero, Citation2016). By publishing more information and reducing information asymmetry, local executives promote government legitimacy and indirectly influence the increase in citizens’ trust in government, which in turn leads more citizens to vote (Pina et al., Citation2010).

The results for women_councillors variable are robust to a variety of different specifications and control variables. By replacing existing control variables with some others - estimated population, age and education of local incumbent - the coefficient of the women_councillors variable remains positive and significant. The results also hold for alternative codings and data sets, e.g., looking at municipalities and cities separately. The female_mayor variable remains non-significant.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The progress in fiscal transparency worldwide can be attributed not only to the ongoing activities of global transparency initiatives but also to national and subnational efforts and readiness to disclose fiscal/budget data digitally.

As part of the approach to measuring actual BT, this paper looks at the availability of five key budget documents on the websites of all Croatian local governments. The OLBT in Croatia is improving from year to year, positively contributing to improving governance.

Over the period during which OLBT was measured, two local elections were held in Croatia, in 2013 and 2017, offering an often-neglected output – the underrepresentation of women in the local executive and representative bodies. Despite small improvements, there is still a large gender imbalance in Croatian local governments. In 2017, women represented only one-quarter of local representatives and less than 10% of local executives. Since females, in accordance with the presented social role and expectation states theories, are perceived in political spheres and decision-making to be more inclusive, more accessible, more willing to have their actions monitored, more proactive and more transparent, as a logical sequence, in this paper, we examined the impact of the local political representation of women on the level of BT.

The main results showed that a high share of women in the local representative body positively affects the level of local government BT. We also find that women are more transparent when it comes to both mandatory and voluntary elements of OLBT. We find a slightly stronger parameter coefficient in regard to voluntary disclosure, indicating that women are more sensitive and responsive to proactive disclosure than men. This is in line with the gender stereotypes literature (social role and expectation states theories), pointing out that female politicians bring new 'modus operandi' and attitudes towards budgetary processes and information disclosure (Beck, Citation2001; Fox & Schuhmann, Citation1999). As argued by Rosenthal (Citation2000), female politicians find it easier to address information asymmetry, as they have a more transparent and inclusive approach towards their electorate. These results reinforce gender stereotypes theories suggesting that women do seem to adjust their attitudes and behaviours according to gender role requirements. Furthermore, we found that other factors affect the level of OLBT: the economic situation in the municipality (unemployment rate), the wealth of citizens (income per capita) and the political engagement of voters (electoral turnout).

This study contributes to the literature by exploring the impact of newly-established OLBT measure on the women political representation at the local government level. To our knowledge, apart from the above-mentioned two studies in Spain, this is the first such study in the rest of Europe, particularly important as Croatia is a relatively new democracy and new EU member. The importance of the contribution also stems from the factuality that our empirical findings are in line with the presented social role and expectation states theories, which recognize the differences between women and men, based on their social (gender) stereotypes.

We can point out several implications of this study. Apart from the gender quotas on candidate lists in local elections, the central government should consider other channels to correct the gender imbalances in political life, like better assigning women’s hierarchical positions on the candidate electoral list and continuously promoting activities that encourage gender-balanced representation. All levels of government and especially political parties, should adhere to gender-balanced representation when compiling candidate lists for elections, if they wish to influence openness across the budget and fiscal cycle. Women themselves need to take responsibility and become motivated to enter political life, such as getting involved politically and being open to running in local elections.

Our findings show the value of examining the influence of women's political representation on OLBT as an important part of local decision-making. The main limitation of the study may be the quantitative nature of the OLBT which measures only the availability of the documents. Further research might incorporate the quality of these documents and/or focuse on the regional or national levels of government, or use some other transparency measure. Future similar studies, especially in the CEE countries, may build on this pioneer paper and examine the possibility of applying OLBT in their own country.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the comments of the commission for the defense of the author's doctoral dissertation on the basis of which the basic concept of this paper was developed.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The dataset used in this paper falls under specifically granted permission, as it contains the sensitive data we have requested from public institutions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Zagreb, the capital, has dual status, both as the city and as the county, but in this research it is treated as a city.

References

- Alesina, A., & Perotti, R. (1996). Income distribution, political instability, and investment. European Economic Review, 40(6), 1203–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(95)00030-5

- Alt, J. E., & Lassen, D. D. (2006). Transparency, political polarization, and political budget cycles in OECD countries. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 530–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00200.x

- Baltagi, B. H. (2005). Econometric analysis of panel data. (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Beck, S. A. (2001). Acting as women: The effects and limitations of gender in local governance. In S. J. Carroll (Ed.), The impact of women in public office. (pp. 49–67). Indiana University Press.

- Berger, J., Cohen, B. P., & Zelditch, M. J. (1966). Status characteristics and expectation states. Stanford Sociology Technical Reports and Working Papers, 1961–1993. Stanford University.

- Bodiroga-Vukobrat, N., & Martinović, A. (2017). Gender equality policies in Croatia - update. European Parliament’s Committee on Women’s rights and Gender Equality (FEMM). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=IPOL_STU(2017)596803.

- Caamaño-Alegre, J., Lago-Peñas, S., Reyes-Santias, F., & Santiago-Boubeta, A. (2013). Budget transparency in local governments: An empirical analysis. Local Government Studies, 39(2), 182–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.693075

- Cameron, C. A., & Trivedi, P. K. (2013). Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge University Press.

- Christiaens, J. (1999). Financial accounting reform in flemish municipalities: An empirical investigation. Financial Accountability and Management, 15(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0408.00072

- Correll, S. J., & Ridgeway, C. L. (2006). Expectation states theory. In J. Delamater (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology. (pp. 29–51) Springer.

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B. (2014). The impact of functional decentralization and externalization on local government transparency. Government Information Quarterly, 31(2), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.10.012

- De Araujo, J. F. F. E., & Tejedo-Romero, F. (2016). Women’s political representation and transparency in local governance. Local Government Studies, 42(6), 885–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1194266

- De Araujo, J. F. F. E., & Tejedo-Romero, F. (2018). Does gender equality affect municipal transparency: The case of Spain. Public Performance & Management Review, 41(1), 69–99.

- Deegan, C. (2002). Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures–A theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(3), 282–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570210435852

- De Simone, E. (2009). The concept of budget transparency: Between democracy and fiscal ilussion. Pavia. http://www.siepweb.it/siep/oldDoc/2009/200931.pdf

- Del Sol, D. A. (2013). The institutional, economic and social determinants of local government transparency. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 16(1), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2012.759422

- Derks, B., Van Laar, C., & Ellemers, N. (2016). The queen bee phenomenon: Why women leaders distance themselves from junior women. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 456–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.12.007

- Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. The Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122–136. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1388226 https://doi.org/10.2307/1388226

- Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Eagly, A. H., & Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C. (2001). The leadership styles of women and men. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 781–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00241

- Eagly, A. H., Karau, S. J., & Makhijani, M. G. (1995). Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 125–145.

- Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Diekman, A. B. (2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In T. Eckes & H. M. Trautner (Eds.), The developmental social psychology of gender. (pp. 123–174). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Esteller-Moré, A., & Polo Otero, J. (2012). Fiscal transparency: (Why) does your local government respond? Public Management Review, 14(8), 1153–1173. https://ec.europa.eu/croatia/sites/default/files/docs/eb90_nat_hr_hr_0.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.657839

- Ferejohn, J. (1999). Accountability and authority: Toward a theory of political accountability. In A. Przeworski, S. C. Stokes, & B. Manin (Eds.), Democracy, accountability, and representation. (pp. 131–153). Cambridge University Press.

- Fox, R. L., & Schuhmann, R. A. (1999). Gender and local government: A comparison of women and men city managers. Public Administration Review, 59(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.2307/3109951

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

- Giroux, G., & McLelland, A. J. (2003). Governance structures and accounting at large municipalities. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22(3), 203–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4254(03)00020-6

- Greene, W. H. (2002). Econometric analysis. Pearson Education LTD.

- Greve, H. R., & Argote, L. (2015). Behavioral theories of organization. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. (pp. 481–486). Elsevier Science and Technology.

- Guillamón, M. D., Bastida, F., & Benito, B. (2011). The determinants of local government's financial transparency. Local Government Studies, 37(4), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2011.588704

- Hamidullah, M. F., Riccucci, N. M., & Pandey, S. K. (2015). Women in city hall: Gender dimensions of managerial values. The American Review of Public Administration, 45(3), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074013498464

- Hausman, J., Hall, B. H., & Griliches, Z. (1984). Econometric models for count data with an application to the patents-R & D relationship. Econometrica, 52(4), 909–938. https://doi.org/10.2307/1911191

- Heald, D. (2003). Fiscal transparency: Concepts, measurement and UK practice. Public Administration, 81(4), 723–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2003.00369.x

- Ho, A. T. K. (2002). Reinventing local governments and the e-government initiative. Public Administration Review, 62(4), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00197

- Hollyer, J. R., Rosendorff, B. P., & Vreeland, J. R. (2011). Democracy and transparency. The Journal of Politics, 73(4), 1191–1205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381611000880

- Holmström, B. (1979). Moral hazard and observability. The Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 74–91. https://personal.utdallas.edu/∼nina.baranchuk/Fin7310/papers/Holmstrom1979.pdf https://doi.org/10.2307/3003320

- Ingram, R. W. (1984). Economic incentives and the choice of state government accounting practices. Journal of Accounting Research, 22(1), 126–144. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490704

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Kaufmann, D., & Bellver, A. (2005). Transparenting transparency: Initial empirics and policy applications. Draft discussion paper presented at the IMF conference on transparency and integrity 6–7 July 2005. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.808664

- Kersting, N. (2015). Local political participation in Europe: Elections and referendums. Hrvatska i Komparativna Javna Uprava: Časopis za Teoriju i Praksu Javne Uprave, 15(2), 319–334.

- Klarić, M. (2017). Problems and developments in the croatian local self-government. Zbornik Radova Pravnog Fakulteta u Splitu, 54(4), 807–823. https://doi.org/10.31141/zrpfs.2017.54.126.807

- Kopits, G., & Craig, J. (1998). Transparency in government operations (IMF Occasional Papers No. 158). IMF Occasional Papers. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781557756978.084

- Lane, J.-E. (2013). The principal-agent approach to politics: Policy implementation and public policy-making. Open Journal of Political Science, 3(2), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2013.32012

- Laswad, F., Fisher, R., & Oyelere, P. (2005). Determinants of voluntary Internet financial reporting by local government authorities. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(2), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2004.12.006

- Lowatcharin, G., & Menifield, C. E. (2015). Determinants of Internet-enabled transparency at the local level: A study of Midwestern county web sites. State and Local Government Review, 47(2), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X15593384

- Medina, B., & Antonio, J. (2015). Public administrations as gendered organizations. The case of spanish municipalities. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 149, 3–30.

- Merchant, K. (2012). How men and women differ: Gender differences in communication styles, influence tactics, and leadership styles. [CMC senior theses]. Claremont McKenna College.

- Nejašmić, I., & Njegač, D. (2001). Spatial (regional) differences of demographic development of the republic of Croatia [Paper presentation]. 41st Congress of the European Regional Science Association: ‘European Regional Development Issues in the New Millennium and Their Impact on Economic Policy, In, 29 August–1 September 2001 (pp. 1–21). European Regional Science Association (ERSA).

- OECD. (2002). OECD best practices for budget transparency. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 1(3), 7–14.

- Ott, K., Bronić, M., Petrušić, M., Stanić, B., & Prijaković, S. (2020). Budget transparency in Croatian counties, cities and municipalities: 2019–April 2020. Newsletter - An Occasional Publication of the Institute of Public Finance, 20(17), 1–15.

- Piotrowski, S. J., & Van Ryzin, G. G. (2007). Citizen attitudes toward transparency in local government. The American Review of Public Administration, 37(3), 306–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074006296777

- Pina, V., Torres, L., & Royo, S. (2010). Is e-government leading to more accountable and transparent local governments? An overall view. Financial Accountability & Management, 26(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0408.2009.00488.x

- Ramkumar, V., & Shapiro, I. (2010). Guide to Transparency in Government Budget Reports: Why are Budget Reports Important, and What Should They Include? International Budget Partnership.

- Rosenthal, C. S. (2000). Gender styles in state legislative committees. Women & Politics, 21(2), 21–45. https://doi.org/10.1300/J014v21n02_02

- Sandoval-Almazan, R., & Gil-Garcia, J. R. (2012). Are government internet portals evolving towards more interaction, participation, and collaboration? Revisiting the rhetoric of e-government among municipalities. Government Information Quarterly, 29, S72–S81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2011.09.004

- Shreeves, R., & Prpic, M. (2019). Women in politics in the EU: State of play, European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2019)635548.

- Styles, A., & Tennyson, M. (2007). The accessibility of financial reporting of U.S. municipalities on the Internet. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 19(1), 56–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-19-01-2007-B003

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

- Tavares, A. F., & da Cruz, N. F. (2020). Explaining the transparency of local government websites through a political market framework. Government Information Quarterly, 37(3), 101249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.08.005

- Vermeir, I., & Van Kenhove, P. (2008). Gender differences in double standards. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(2), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9494-1

- Webster, M., & Driskell, J. E. (1978). Status generalization: A review and some new data. American Sociological Review, 43(2), 220–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094700

- Wehner, J., & de Renzio, P. (2013). Citizens, legislators, and executive disclosure: The political determinants of fiscal transparency. World Development, 41(1), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.06.005

- World Bank. (2013). Global stock-take of social accountability initiatives for budget transparency and monitoring: Key challenges and lessons learned. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/457241468340847491/pdf/815430REVISED00ocktake0Report0Final.pdf