Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, which marked the whole of 2020, caused numerous difficulties in the economies and the health systems of all countries and led to a global economic and health crisis. This paper explores citizens’ attitudes towards tourism on Croatian islands during the COVID-19 pandemic using survey data from over 200 islanders. The results reveal that almost one-third of the citizens considered the islands overcrowded with tourists in the pre-pandemic period. The survey results indicate a link between the expected impact of the development of tourism, citizens’ attitudes towards tourism, and their willingness to take a larger health risk due to the pandemic. The results also show that islanders’ attitudes toward economic measures taken during the COVID-19 pandemic were not homogenous and were significantly different depending on the size of the island.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, which marked the whole of 2020, caused numerous problems in the economies and health systems of all countries and led to a global economic and health crisis. In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 virus a public health threat of international concern, and in March of that year, a pandemic was declared, followed shortly thereafter by a quarantine declared by countries worldwide. Among the most widespread measures implemented to combat the spread of COVID-19 were full or partial travel restrictions, resulting in a significant decline in tourist activity.

The uncertainty of this time and the inability to predict the pandemic’s duration had consequences for human behaviour. The literature dealing with the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 shows that a pandemic can cause significant and widespread health problems, manifested through, for example, stress, anxiety, depression, fear, and anger (Torales et al., Citation2020; Di Crosta et al., Citation2020). Farzanegan et al. (Citation2021) use cross-country regression analysis for more than 90 countries and show a positive link between international tourism and the confirmed cases of and deaths resulting from COVID-19. The consequences for tourist supply and demand have been immense.

On the one hand, private and business trips have been cancelled, and travel restrictions have been introduced by many nations, all of which have affected the demand for tourist services. On the other hand, many countries have limited accommodation capacity, and tourism service providers are treating tourists with great caution and concern. Losses in countries highly dependent on tourism are already substantial. According to the World Tourist Organization (UNWTO), there were over 500 million fewer interactive tourists in Europe recorded in 2020 compared to 2019, and the losses are already much higher than during the global economic crisis of 2008–2009 (UNWTO, Citation2021).

This paper makes two contributions to the scientific literature. First, the paper contributes to the literature dealing with the determinants of resilience for the tourism industry. There is a growing body of literature addressing the risk tourists are prepared to take in situations of uncertainty caused by natural disasters, viruses, terrorist attacks, or their immediate aftermath (Kozak et al., Citation2007; Williams & Baláž, Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2019; Fischhoff et al., Citation2004).

Having in mind the connection between human behaviour and the perceived health risks from tourism, the main purpose of this paper is to explore the subjective attitudes of Croatian islanders to tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. We focus on islanders as a group for whom the economic effects on tourism of the COVID-19 pandemic are of great value in the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic; islands have a higher tourism vulnerability to the consequences of COVID-19 than interior areas (Duro et al., Citation2021), which is why it is important to investigate them separately.

Islands are regions that are very challenging to investigate, and there is no agreement on the benefit of a tourism specialisation. The recent literature shows that tourism specialisation on small islands is not sustainable in the medium and long run (Hoarau, Citation2022), and economic diversification should be encouraged. By contrast, Brau et al. (Citation2011) argue that, under some conditions, a tourism specialisation boosts the economy, growing faster than some other kinds of specialisation.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Following this introductory section, the literature concerning the impact of COVID-19 on tourism is reviewed in Section 2. Section 3 provides an overview of the methodology and data. Section 4 sets out the results of a survey of islanders’ attitudes towards tourism on their islands during the COVID-19 virus pandemic. Section 5 presents some implications of this study and our concluding remarks.

2. Literature review

2.1. Lessons learned

With the intensive development of tourism since the 1970s, there have been intensive academic investigations of residents’ attitudes and perceptions (Peters et al., Citation2018; Rua, Citation2020). There are at least three relevant theories emphasising the importance of personal attitudes and interactions between residents and tourists for the development of tourism. These are the social exchange theory (SET), the social amplification of risk framework (SARF), and the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) theory.

SARF is primarily focused on the relationship between information communication and risk perceptions, while KAP explains how individuals’ knowledge can influence their behaviour (Shen & Yang, Citation2022). Based on the SARF and KAP theories, Shen and Yang (Citation2022) construct a theoretical model to elaborate on residents’ support for tourism. These results indicate that residents’ social media use, knowledge of COVID-19, and attitudes to tourism and tourists are all positively related to their support for tourism. Tourism is affected by personal and physical perceptions of security (Novelli et al., Citation2018), and residents’ support for tourism is negatively related to the level of risk perceived (Shen & Yang, Citation2022).

SET is one of the oldest theories of social behaviour and has had a profound impact on the theories underlying investigations of resident perceptions of tourism (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016). SET provides a theoretical basis for understanding differences in the positive or negative attitudes of residents to the impacts of tourism (Ap, Citation1992). According to SET, individual attitudes depend on subjective perception and evaluation of outcomes (Andereck et al., Citation2005). Where the perceived benefits are greater than the perceived costs or risks, there will be positive attitudes toward tourism (Brunt & Courtney, Citation1999; Haralambopoulos & Pizam, Citation1996; Jurowski et al., Citation1997; Lankford & Howard, Citation1994; McGehee & Andereck, Citation2004; Sirakaya et al., Citation2002).

There are a few studies dealing with residents’ perceptions of tourism (Bimonte & Faralla, Citation2016), but on the topic of residents’ attitudes and reactions to perceived health-related risks, the literature is lacking (Joo et al., Citation2021). Taking the above into account, we test the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1. More positive islander attitudes toward tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with a more positive perception of the impact of tourism on local development and with the willingness to take a bigger health risk.

Health-related concerns are one of the four major risk factors for tourism (Lepp & Gibson, Citation2003). In times of increased health-related challenges and crises (e.g., SARS, Ebola, COVID-19), there is a sudden decline in tourist activity (Hoarau, Citation2022; Novelli et al., Citation2018) as tourists and residents respond to the new situation. The crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic requires policy actions to mitigate the impact and support recovery.

Recent literature shows a positive relationship between the size of the tourism industry and the economic measures adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Khalid et al., Citation2021; Elgin et al., Citation2020). However, there is a gap regarding the acceptability and suitability of these economic measures from the perspective of residents. This paper attempts to fill this gap by investigating the factors influencing islanders’ attitudes toward economic measures. We test two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2. More positive islander attitudes about COVID-19-related economic measures are associated with the size of the island.

Hypothesis 3. Negative islander attitudes about support for the designation Croatian Island Product (CIP) are related to low levels of knowledge about government economic measures.

Brida et al. (Citation2014) and Wang and Xu (Citation2015) note that, generally, in assessing the effects of tourism on a place, citizens are much more demanding if it is the place of their birth. In the situation of a viral pandemic, increasing the number of tourists increases risk; it can be expected that the negative effects of tourism will be most pronounced among citizens. Many researchers investigate tourism from the tourist perspective (e.g., Neal et al., Citation2007, Sirgy et al., Citation2011, Couto et al., Citation2020) and show that the personal benefits of tourism depend on the interaction between tourists and residents (Rua, Citation2020). The support of residents is fundamental to creating a successful tourist destination (Bimonte & Faralla, Citation2016; Lepp, Citation2007). The literature on residents’ attitudes toward tourism development shows that their views are not homogenous and depend on many things, including socio-demographic factors (Snaith & Haley, Citation1999), whether it is the tourist season (Bimonte & Faralla, Citation2016), the perceived value of tourism in life satisfaction (Woo et al., Citation2015) and the perceived economic and environmental impacts of tourism (Brida et al., Citation2014). Lepp and Gibson (Citation2003) notice that the perception of health-related risks associated with tourism is higher among mass tourists and women. The COVID-19 pandemic increased fear among residents, raised the question of tourism sector vulnerability, and required additional actions to revive tourism and enhance the sustainability of the tourism sector (Abbas et al., Citation2021; Gössling et al., Citation2021).

2.2. Islands, tourism and the COVID-19 pandemic

The growth of tourism involves profound changes for regions, especially for islands. According to Ioannides et al. (Citation2001), tourism has a greater impact on islands than on mainland regions. In addition, simple and sensitive insular economies usually become overdependent on tourism, making them more vulnerable (Briguglio, Citation1995; McElroy and de Albuquerque, 1992). Therefore, the participation of locals in relevant decision-making processes and destination management could be important (Sharpley, Citation2014; Braun et al., Citation2013; Monterrubio Cordero, Citation2008; Andereck et al., Citation2005; Andereck & Vogt, Citation2000; Starc & Stubbs, Citation2014; Starc, Citation2000). In addition to economic effects, large-scale tourism, if not well planned, can cause several other changes, including environmental changes, loss of local culture and identity, and changes in the socio-cultural characteristics of residents (Andereck et al., Citation2005).

Tourism has been an important driver of the economic development of Croatia since the 1960s, contributing significantly to the country’s gross domestic product and with crucial economic importance for the development of the islands (Šulc, Citation2020; Kordej-De Villa & Starc, Citation2020; Faričić et al., Citation2010; Vidučić, Citation2007; Gorgona, Citation2002; Kušen, Citation2001). Tourism is also a significant export activity in Croatia and has been steadily growing since 2002 (The Institute of Economics & Zagreb, Citation2018). In 2016, the contribution of tourism to total GDP was 11.4% (CBS, Citation2019). The main sectoral data on tourism in the 2013–2020 period are presented in .

Table 1. Sectoral data in the 2013–2020 period.

In 2019 Croatia recorded 19.6 million arrivals and 91.2 million overnight stays. In comparison to 2018, this represents a 4.8% growth in arrivals and a 1.7% growth in overnight stays. The strong growth of tourism in Croatia in 2019 is seen in the fact that there were 2.3 times more overnight stays than in 2000. From 2013 to 2017, the year-on-year increase in arrivals and overnight stays was stronger for foreign guests, whereas in 2018 and 2019, this increase was greater for domestic guests.

Domestic-guest arrivals increased by 9.4% in 2019, and their overnight stays increased by 9.5% from 2018, while foreign-guest arrivals grew by 4.3% year-on-year, and their overnight stays grew by 1.2%. Foreign tourists accounted for a 92% share of the total overnight stays by all tourists. In 2019 the average tourist stay was 4.7 nights, part of a trend of a shortening of the average stay evident since 2000 (when it was 5.8 nights). Foreign tourists stay an average of 4.8 nights per arrival, and domestic tourists stay an average of 3.2 nights per arrival (CBS, Citation2020).

One of the important characteristics of Croatian tourism is its distinct seasonality. This is also revealed by the time distribution of the number of tourists staying per month. In 2019, almost 73% of the total annual number of overnight stays was performed between June and September, with August accounting for 31% of the total annual nights. Adriatic Croatia is the most important Croatian tourism region in terms of tourist arrivals and stays. In the area of the seven coastal counties in 2019, 95% of all stays and 87% of all arrivals in Croatia were recorded.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and related travel restrictions, most countries, including Croatia, have seen a significant decline in tourist activity. According to data from the Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Croatia recorded 7 million tourist arrivals in 2020, amounting to 41 million overnight stays. Compared to 2019, the number of tourist arrivals decreased by 64% and the number of overnight stays by 55%. As expected, a stronger drop in arrivals and overnight stays was seen for foreign tourists, which is in accordance with findings in other popular tourist destinations around the world (Arbulú et al., Citation2021a; Joo et al., Citation2021). While domestic tourists achieved a year-on-year decline of almost 34% and overnight stays of 24%, arrivals of foreign tourists decreased by 68% year-on-year and overnight stays by 58%. Out of total arrivals in 2020, foreign tourists accounted for 79% and 87% of total overnight stays.

Tourist season in 2020 was also specific because guests stayed longer in one destination than in past periods, while rooms, apartments, holiday homes, and campsites were the most desirable type of accommodation. For example, while in 2019, foreign tourists spent an average of 4.8 nights in Croatian tourist destinations and domestic tourists stayed for 3.2 nights, in 2020, foreign tourists stayed an average of 6.4 nights and domestic tourists and an average of 3.7 nights.

Viewed by county, the highest number of overnight stays and tourist arrivals in 2020 was seen in coastal counties, with a total of 39 million overnight stays and 6 million arrivals, accounting for almost 97% of total overnight stays and 90% of total tourist arrivals in Croatia during the observed period.

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted many different economic sectors, including tourism (Gössling et al., Citation2021; Hall et al., Citation2020). Although various measures have been adopted since June 2020 to support tourism, it remains one of the hardest-hit sectors, according to the UNWTO (Citation2020a). As crises (including human-made and natural disasters) are familiar to the sector, it has developed different strategies for resilience. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has been different to previous crises. First, the decline in the tourism industry has been worldwide (UNWTO, Citation2020b). Second, there has been a severe loss of economic activity in the sector. Third, the crisis has the potential to modify many tourism segments (Dolnicar & Zare, Citation2020), and fourth, it has produced a high level of uncertainty.

The review of studies on COVID-19 and tourism reveals three prevailing themes: government crisis management, tourist perceptions, and decision-making by tourism service providers (Persson-Fischer & Liu, Citation2021). In 2021 there was an expected shift in research and an explosion in publications of empirical analyses of the impact of COVID-19 on the tourism industry (Yang et al., Citation2020; Qiu et al., Citation2020; Gössling et al., Citation2021; Škare et al., Citation2021; Payne et al., Citation2022; Sharma et al., Citation2021; Šulc & Fuerst-Bjeliš, Citation2021; Cheng et al., Citation2022). However, research on the impacts of COVID-19 on island tourism remains limited (e.g., Arbulú et al., Citation2021a; Arbulú et al., Citation2021b; Miternique, Citation2021; Guerra-Marrero et al., Citation2021).

The Croatian islands are a very attractive and receptive region for tourists. Since the 1970s, tourism has been the most important economic activity on the Croatian islands (Weber et al., Citation2001; Kordej-De Villa & Starc, Citation2020). The Croatian archipelago is the second-largest archipelago in the Mediterranean and comprises 1,244 islands (47 of which are permanently inhabited) covering a total area of 3,300 km2 (about 6% of Croatian mainland territory). Administratively, the islands belong to seven coastal counties and 51 island towns or municipalities. In the period 2009–2017, tourist arrivals on the islands increased by 22%, and overnight stays by 27%. In 2017, 3.2 million tourists visited the islands and were responsible for 20.7 million overnight stays. The islands are responsible for 18.4% of all tourist arrivals in Croatia, and their share in total overnight stays is 24% (Faričić & Čuka, Citation2020). The seasonality of Croatian tourism is even more profound on the islands, where most tourists arrive between June and August and pose significant pressure on island infrastructure. Furthermore, almost 50% of all tourist arrivals and overnight stays are located on five bridged islands (Krk, Pag, Vir, Murter, Čiovo).

According to the Croatian Constitution, islands are a region given special protection and of unique value. During the COVID-19 pandemic, island development policy became even more challenging and complex. This is especially true for the island health system, which is overloaded during the summer tourist season; COVID-19 had different impacts on the island than on the mainland.

3. Research methodology

This quantitative study is based on a survey conducted in Croatia during the COVID-19 lockdown period in the second quarter of 2020. Data were gathered from a sample of respondents living on Croatian islands. About 1,000 e-mail addresses of individuals living on the islands, particularly owners of family farms and people who rented their apartments and of island companies, were collected via the Internet, after which chain sampling was used. This non-probability technique involves the researcher selecting a random set of individuals from a given finite population who meet certain research criteria. In the second step, the selected respondents are asked to forward the surveys to other people who meet the criteria, resulting in a sufficiently large database to conduct the analysis. In this method of sampling, researchers work from the initial pool of contacts from which the sampling momentum develops and capture the increasing chain of participants (Parker et al., Citation2019). It is a sampling mechanism commonly used in situations where the standard sampling procedure is either impossible or expensive (Handcock & Gile, Citation2011).

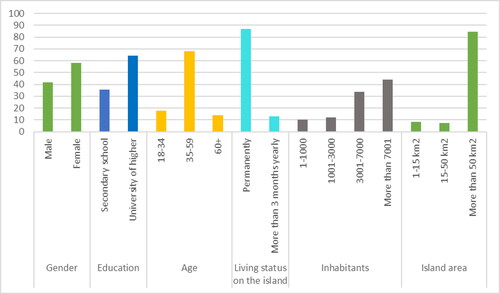

By applying this methodology, a total of 205 survey questionnaires were collected from citizens older than 18 years and who have different socio-demographic characteristics (). Croatian islands do not function as a homogenous region (Turner, Citation2020), and respondents were from islands of different sizes in different counties, with different population densities, proximity and connections to the mainland. The characteristics of the islands represented in the research are shown in .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of islands.

shows the characteristics of the sampled respondents. Most of the respondents are highly educated, with 64% having attained a university degree or completed higher education, while 36% had a secondary school diploma; 42% of respondents were men, and 58% were women. The average age of respondents was 47 years, with 87% permanent inhabitants and 13% living on the island for more than three months yearly. The distribution of respondents by islands indicates the following islands were represented: Cres (12.2% of respondents), Dugi Otok (2.4%), Ilovik (0.5%), Iž (0.5%), Krk (6.3%), Lošinj (8.8%), Olib (0.5%), Pag (2.9%), Pašman (2.0%), Rab (6.3%), Silba (0.5%), Susak (0.5%), Ugljan (3.9%), Vir (2.4%) and Zlarin (2.4%). For the remaining respondents, there is no information on the name of their island of residence, or they stated that they were residents of two islands. This data shows that the analysis covers small, medium and large islands in terms of inhabitants and island area.

The survey contained 16 questions about tourism, the arrival of domestic and foreign tourists, measures implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and measures targeted to help the economy during the pandemic. The list of variables or questions used in the analysis appears in the Annexure as . Respondents were asked to evaluate each claim on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Table A1. Data sources.

The survey data were analysed using quantitative methods, more specifically, descriptive and inferential statistics. We used the chi-squared test and t-test statistics to investigate the differences in attitudes to tourism on the islands at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. The t-test is used to determine if there is a significant difference between the means of two groups, while the chi-square test is a non-parametric method used to analyse differences between more groups (see Pearson, Citation1900; Plackett, Citation1983; McHugh, Citation2013). The survey data were analysed using SPSS statistical software.

4. Results and discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic produced a profound crisis for tourism (Benjamin et al., Citation2020). During the pandemic, many trips were cancelled and travel restricted, and many countries were in lockdown, with people less inclined to travel and facing considerable uncertainty. The changes were also noticeable in tourism offerings. Individuals and the government had to change their assessments, behaviour and usual way of conducting business (Galvani et al., Citation2020). In the first step of the analysis, the islanders’ attitudes to tourism during the COVID-19 virus pandemic were investigated. The survey was conducted during the first lockdown in Croatia, just before the start of the 2020 tourist season.

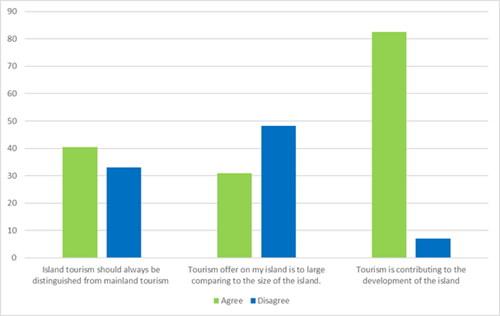

The first part of the analysis explores the islanders’ attitudes to tourism on the island with the intention of gathering general insights on the importance of tourism for the development of the island. The results (depicted in ) show that 83% of the respondents saw tourism as contributing positively to the development of their island. However, 41% thought that there should be a policy for sustainable tourism policy for islands that is distinct from that for mainland tourism, which is consistent with Figueroa and Rotarou (Citation2021) and Constantoglou and Klothaki (Citation2021).

Figure 2. General islanders' attitudes toward tourism, % of respondents.

Source: authors' analysis based on survey data.

Almost one-third of the islanders considered the level of tourism on their island too high for its size, indicating many islanders feel that their island is overcrowded with tourists during the summer season. As shown by Ma et al. (Citation2020), islands have a higher ecological vulnerability to tourism and tourism-induced activities than the mainland, and it is expected that islanders will evaluate the effects of tourism differently than other residents. The attitude of islanders that the islands are overcrowded with tourists may lead to the islanders’ increased intention to reduce overcrowding during a pandemic; people may be more prone to avoiding others to reduce the risk of getting infected.

Negative attitudes of the islanders towards tourists affect the tourist offerings and thus the contribution of tourism to the local and national economy. Therefore, the next step of the analysis aimed to investigate the perception of islanders about tourism with special emphasis on investigating the impacts of the COVID-19 virus pandemic on the islanders’ attitudes. Literature shows that there is a positive relationship between citizens’ support for tourism and their perceived benefits (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016; Rua, Citation2020; Brida et al., Citation2014, Ramkissoon, Citation2020). However, residents are more inclined to adopt protective behaviour when they perceive a higher level of risk (Shen & Yang, Citation2022); therefore, in the context of a health crisis, the desire to preserve health can outweigh the previously expected gains of tourism.

The results of the survey indicate that the pandemic reinforces the views of respondents who believe that the state should distinguish island tourism from that on the mainland. Also, as shown in , the results suggest that many islanders believe accommodation capacities for tourists should be limited. Such an attitude partly stems from their views that the tourism offered on the islands is too large concerning the size of the island. Every fifth respondent thinks that the tourism offer on the islands should be smaller. At the same time, this attitude is somewhat more prevalent on medium-sized islands, i.e., on islands with an area between 15 and 50 m.2

Table 3. Attitudes towards tourism in the context of the COVID-19 virus pandemic.

The results of the survey also indicate that islanders recognise the importance of tourism for local economic development, which is in accordance with the findings in the growing body of literature on the role of tourism in island development, as well as the importance of different forms of tourism (Müller, Citation2019; Kivela & Klarić, Citation2017; Jakl et al., Citation2013; Krajnović et al., Citation2021; Šulc, Citation2017). Of the respondents surveyed, 58% thought tourism contributed to the development of the island, while only 7% disagreed. The assessment of the impact of tourism on development as weak was mainly made for smaller islands.

One of the major problems for tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic stemmed from the low level of confidence in the island health system. Almost half of the respondents believed that the organisation of the health system could not handle the larger number of patients that could result from tourism. This is an unsurprising result, given that the healthcare system is one of the major problems of life on the islands (Starc, Citation2017).

According to the respondents, the uncertain protocols for receiving tourists presented an additional problem. Lack of confidence in the quality of the healthcare system influenced the respondents’ views on the quantity and structure of tourism on the islands during the pandemic. Around 40% of respondents thought the arrival of people on the islands should be strictly controlled, and almost one-third thought homeowners who did not live on the island should be prohibited from renting these out as holiday homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Following the SET theory, it is clear that the pandemic affected the residents’ perception of tourism and, from their points of view, the expected costs and risks of tourism on the islands became larger than the expected benefits.

The survey results indicate a link between citizens’ attitudes towards the contribution of tourism to the development of the island and their willingness to take on the resulting higher risk in the pandemic (χ2 = 0.030). Most who did not see the benefit of tourism to the islands’ development were against tourist activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, almost half of the respondents who believed tourism does not contribute to the development of the island also believed that accommodation capacities should be limited during the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 44% of those who did not see tourism making a positive contribution to the island development and 83% with a neutral view on the role of tourism thought the islands should be specially protected from tourist arrivals during the pandemic (χ2 = 0.126).

These findings confirm hypothesis 1; more positive resident attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with their perception of the importance of tourism for local development. This implies that islanders who saw the positive development effects of tourism and some other economic gains are more prone to take the risk. These results are in line with Devine et al. (Citation2009) and Alrwajfah et al. (Citation2019), who confirm the relationship between residents’ attitudes and their perceptions of the benefits of tourism. We do not have data from the survey to separately assess the opinions of residents born on the islands. However, relying on the results from Brida et al. (Citation2014) that show native-born residents perceive the impact of tourism more negatively, it could be assumed that differences in the respondents’ attitudes about tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic could also depend on how long they had been permanent island residents.

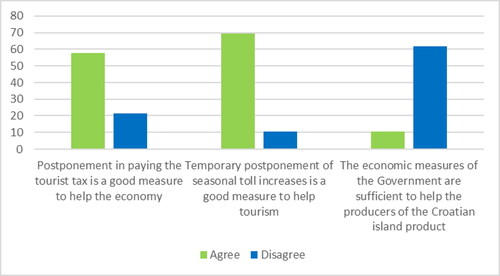

Khalid et al. (Citation2021) show a positive link between the size of the tourism sector and the range and economic importance of measures introduced by the government in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We thus investigated attitudes towards the three measures introduced by the Croatian government to lessen the negative impact of COVID-19 on tourism. These measures were active at the time of the survey (; ).

The largest percentage of respondents considered the temporary postponement of seasonal toll increases a useful measure to help tourism. The results of the survey are shown in , which shows that 69% of the respondents saw this measure as having a positive effect on the arrival of tourists in the country. In addition, 58% of respondents thought that the postponement of the payment of the tourist tax was a good measure to help tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a positive relationship between the respondents’ attitudes toward this measure and the size of the island; this is shown in . Therefore, this finding confirms our second hypothesis.

Table 4. Differences in attitudes towards economic measures – postponement in paying the tourist tax (m_1).

Table 5. Differences in attitudes towards economic measures –temporary postponement of seasonal toll increase (m_2).

The results related to the economic measures for the production of CIP, shown in , are surprising, revealing that only 11% of islanders thought that the measures to help CIP producers were sufficient. Quite the opposite was true; 62% of respondents considered the measures insufficient for the development of the CIP. This attitude was prevalent on all islands, regardless of their size (in terms of area and population) and regardless of the county in which they are located. However, despite the predominantly negative attitude towards these measures’ potential success, this view also depended on the general knowledge of the population about economic measures. Residents who had less knowledge about economic measures were generally also the biggest opponents of this particular measure, confirming our third hypothesis.

Table 6. Differences in attitudes towards economic measures – support for Croatian island product (m_3).

The pandemic appeared suddenly and did not allow time for island citizens to adjust their tourist offerings or start new businesses. Research points to the importance of developing strategies that allow the consequences of crises to be offset and accelerate recovery in tourism-dependent areas. Given the importance of tourism for the Croatian economy, it is important to strengthen its resilience by distinguishing measures for small and large islands; the survey results indicate that there are differences in the residents’ perceptions of tourism depending on the size of the island they inhabit.

The crisis resilience of the islands could be enhanced by pandemic preparedness in terms of risk anticipation capacities, tourism-sector preparedness and pandemic management protocols. In addition, crisis management plans should be in place that covers crisis communication and integral governance support. All these policies should acknowledge the islands’ features and uniqueness.

5. Conclusions and implications

Residents are always influenced by the economic, environmental, and socio-cultural impacts of tourism development. Given that the costs and benefits of tourism are not uniformly distributed across space, insights into residents’ perceptions of tourism are needed to formulate sound economic policies. The link between local perceptions and attitudes toward tourism development is still insufficiently understood. Therefore, further empirical research on the role of personal attitudes in tourism development is essential.

Changes in tourism because of COVID-19 are imbalanced, both in space and time. Some destinations will re-examine the nature of their tourism and the role of domestic tourists, but many of them will proceed with the same policy as before the COVID-19 crisis (Gu et al., Citation2022). One of the reasons for such behaviour is the lack of stakeholders in tourism that question the adequacy of success which is measured merely by the number of arrivals and overnight stays.

This paper questions the sustainability of tourism on the islands in the context of the COVID-19 virus pandemic. The results of the analysis show that the level of additional health risks due to the arrival of tourists that is considered acceptable depends on the expected benefits from tourism. The findings indicate that a relatively large number of islanders do not see the positive effects of tourism on the local development of their island, although they are aware of the benefits of tourism for economic development in general. However, the lack of expected benefits from tourism affects the population’s tendency towards tourism in the conditions of the COVID-19 virus pandemic.

Results also reveal that islanders’ attitude toward economic measures at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic is not homogenous and is found to be significantly different depending on the size of the island. Residents of the smaller islands, in terms of population and size, are more critical of economic measures. They expect more effective and efficient economic measures to account for their more limited resources. In addition, the results suggest the importance of clear and widespread communication about the expected effects of economic measures. This is particularly important given recent research that suggests the tourism sector may take longer to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic than previously expected (e.g., Škare et al., Citation2021).

Local communities comprise people with different attitudes, fears, and expectations. Tourism is extremely sensitive to natural disasters, health-related risks, and crises. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly serious as it has included widespread measures forbidding travel and the imposition of lockdowns and social distancing with economic and social costs (Qiu et al., Citation2020). Residents were not immune to the health threat and faced the dilemma of whether to accept the higher health risk and gain economic benefits or avoid tourists. As a result, islanders often had to compromise their financial stability and business continuity. The results of this research indicate that the willingness of residents to take higher risks is related to the expected benefits for the local community. Many inhabitants considered the tourism on many islands as already being too extensive. The seasonality of Croatian tourism exacerbates the pressure on island infrastructure, and the low level of confidence in the healthcare system is even more pronounced during a pandemic.

The study has some theoretical and practical implications. First, according to our best knowledge, this is one of the first attempts to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on Croatian island tourism from the perspective of residents. The residents’ perspective is particularly important because it affects their support for local tourism development. Second, the presented findings offer useful insights for policymakers, who can enforce policies that will enhance positive attitudes to tourism. In addition, residents can participate in the decision process related to local tourism development. The limitation of the research is that the survey did not cover all inhabited islands, and the policy implications of this research should be treated carefully. Given the economic importance of tourism for other parts of the country, it would be important to research the entire territory of the Republic of Croatia.

According to the survey results and given the vulnerability of Croatian islands, it is preferable to focus on more sustainable forms of tourism. This is in line with the notion that the tourism growth model should be questioned and the economy should be oriented toward a more sustainable approach (Hanafiah et al., Citation2013; Gössling et al., Citation2021; Niewiadomski, Citation2020; Sigala, Citation2020; Prideaux et al., Citation2020; Wu, Citation2021). In a pandemic situation with high financial costs, it is challenging to make changes for tourism to revive more sustainably. Thus, the main goal is to minimise tourism’s negative impacts on the region and to estimate the capacity of island destinations accurately. Addressing the challenges and complexity of the tourism sector requires inclusive governance, including tourism planning and management. Coordination between island development policy and national policy requires the participation of local actors in addition to national policymakers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abbas, J., Mubeen, R., Iorember, P. T., Raza, S., & Mamirkulova, G. (2021). Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: Transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 2, 100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100033

- Alrwajfah, M. M., Almeida-Garcia, F., & Cortés-Macías, R. (2019). Residents’ perceptions and satisfaction toward tourism development: A case study of Petra Region, Jordan. Sustainability, 11(7), 1907. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/7/1907/pdf.

- Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K., Knopf, R., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perception of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1056–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

- Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900104

- Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perception on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90060-3

- Arbulú, I., Razumova, M., Rey-Maquieira, J., & Sastre, F. (2021a). Can domestic tourism relieve the COVID-19 tourist industry crisis? The case of Spain. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100568

- Arbulú, I., Razumova, M., Rey-Maquieira, J., & Sastre, F. (2021b). Measuring risks and vulnerability of tourism to the COVID-19 crisis in the context of extreme uncertainty: The case of the Balearic Islands. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39, 100857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100857.

- Benjamin, S., Dillette, A. K., & Alderman, D. H. (2020). We can’t return to normal: Committing to tourism equity in the post-pandemic age. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759130

- Bimonte, S., & Faralla, V. (2016). Does residents’ perceived life satisfaction vary with tourist season? A two-step survey in a Mediterranean destination. Tourism Management, 55, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.011

- Brau, R., Di Liberto, A., & Pigliaru, F. (2011). Tourism and development: A recent phenomenon built on old (institutional) roots? The World Economy, 34(3), 444–472. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1566775

- Braun, E., Kavaratzis, M., & Zenker, S. (2013). My city-my brand: The different roles of residents in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331311306087

- Brida, J. G., Disegna, M., & Osti, L. (2014). Residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and attitudes towards tourism policies. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism, 9(1):37–71.

- Briguglio, L. (1995). Small island developing states and their economic vulnerabilities. World Development, 23(9), 1615–1632. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00065-K

- Brunt, P., & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(3), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00003-1

- CBS. (2019). Satelitski račun Turizma za Republiku Hrvatsku u 2016. Priopćenje 12.4.1. 15.1.2019.

- CBS. (2020). Statistička izvješća: Turizam u 2019. 1661. https://www.dzs.hr/Hrv_Eng/publication/2020/SI-1661.pdf.

- Cheng, J., Gao, X., Saliba, C., & Dördüncü, H. (2022). Examine the nexus between covid-19 and tourism: Evidence from Beijing. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 35(1), 2365–2385. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2021.1942119

- Constantoglou, M., & Klothaki, T. (2021). How much tourism is too much? Stakeholder’s perceptions on overtourism, sustainable destination management during the pandemic of COVID-19 era in Santorini Island Greece. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 9, 288–313. https://doi.org/10.17265/2328-2169/2021.05.004

- Couto, G., Castanho, R. A., Pimentel, P., Carvalho, C., Sousa, Á., & Santos, C. (2020). The impacts of COVID-19 crisis over the tourism expectations of the Azores archipelago residents. Sustainability, 12(18), 7612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187612

- Devine, J., Gabe, T., & Bell, K. P. (2009). Community scale and resident attitudes towards tourism. The Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 39(1), 11–22.

- Di Crosta, A., Palumbo, R., Marchetti, D., Ceccato, I., La Malva, P., MaieLla, R., Cipi, M., Roma, P., Mammarella, N., Verrocchio, M. C., & Di DomeNico, A. (2020). Individual differences, economic stability, and fear of contagion as risk factors for PTSD symptoms in the COVID-19 emergency. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567367

- Dolnicar, S., & Zare, S. (2020). COVID19 and Airbnb: Disrupting the disruptor. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102961

- Duro, J. A., Perez-Laborda, A., Turrion-Prats, J., & Fernandez-Fernandez, M. (2021). Covid-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100819

- Elgin, C., Basbug, G., & Yalaman, A. (2020). Economic policy responses to a pandemic: Developing the COVID-19 economic stimulus index. Covid Economics, 1(3), 40–53.

- Faričić, J., & Čuka, A. (2020). The Croatian islands: An introduction. In N. Starc (Ed.), The notion of near islands - the Croatian Archipelago (pp. 55–88). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Faričić, J., Graovac, V., & Čuka, A. (2010). Mali hrvatski otoci – radno-rezidencijalni prostor i/ili prostor odmora i rekreacije. Geoadria, 15(1), 145–185. https://doi.org/10.15291/geoadria.548

- Farzanegan, M. R., Gholipour, H. F., Feizi, M., Nunkoo, R., & Andargoli, A. E. (2021). International tourism and outbreak of Coronavirus (COVID-19): A cross-country analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 60(3), 687–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520931593

- Figueroa, B., & Rotarou, E. S. (2021). Island tourism-based sustainable development at a crossroads: Facing the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(18), 10081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810081

- Fischhoff, B., De Bruin, W., Perrin, W., & Downs, J. (2004). Travel risks in a time of terror: Judgments and choices. Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 24(5), 1301–1309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00527.x.

- Galvani, A., Lew, A. A., & Perez, M. S. (2020). COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760924

- Gorgona, J. (2002). Turizam u funkciji gospodarskog razvitka hrvatskih otoka. Ekonomski Pregled, 53(7-8), 738–749.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism, and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gu, Y., Onggo, B. S., Kunc, M. H., & Bayer, S. (2022). Small Island Developing States (SIDS) COVID-19 post-pandemic tourism recovery: A system dynamics approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(9), 1481–1508. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1924636

- Guerra-Marrero, A., Couce-Montero, L., Jiménez-Alvarado, D., Espino-Ruano, A., Núñez-González, R., Sarmiento-Lezcano, A., Santana del Pino, A., & Castro, J. J. (2021). Preliminary assessment of the impact of Covid-19 pandemic in the small-scale and recreational fisheries of the Canary Islands. Marine Policy, 133, 104712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104712

- Hall, C. M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2020). Pandemics, transformations, and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 577–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759

- Hanafiah, M., Jamaluddin, M., & Zulkifly, M. (2013). Local community attitude and support towards tourism development in Tioman Island, Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 105, 792–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.082

- Handcock, M. S., & Gile, K. J. (2011). On the concept of snowball sampling. Sociological Methodology, 41(1), 367–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9531.2011.01243.x

- Haralambopoulos, N., & Pizam, A. (1996). Perceived impacts of tourism: The case of Samos. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(3), 503–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00075-5

- Hoarau, J.-F. (2022). Is international tourism responsible for the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic? A cross-country analysis with a special focus on small islands. Review of World Economics, 158(2), 493–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-021-00438-x

- Ioannides, D., Apostolopoulos, Y., & Sonmez, S. (2001). Mediterranean islands and sustainable tourism development. Practices management and policies. Continuum.

- Jakl, Z., Bitunjac, I., Medunić-Orlić, G., & Logar, I. (2013). Nautical tourism development in the Lastovo islands nature park. In H. Healy, J. Martinez-Alier, L. Temper, M. Walter, J-F. Gerber (Eds.), Ecological economics from the ground up (pp. 335–336). Routledge.

- Joo, D., Xu, W., Lee, J., Le, C.-K., & Woosnam, K. M. (2021). Residents’ perceived risk, emotional solidarity, and support for tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100553

- Jurowski, C., Uysal, M., & Williams, D. (1997). A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 36(2), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759703600202

- Khalid, U., Okafor, L. E., & Burzynska, K. (2021). Does the size of the tourism sector influence the economic policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Current Issues in Tourism, 24(19), 2801–2820. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1874311

- Kivela, J., & Klarić, Z. (2017). Longitudinal assessment of the carrying capacity of a typical tourist island: Twenty years on. In L. Dwyer, R. Tomljenović & S. Čorak (Eds.), Evolution of destination planning and strategy. The rise of tourism in Croatia (pp. 265–278). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kordej-De Villa, Ž., & Starc, N. (2020). On the Rim of Croatia and Croatian development policies. In N. Starc (Ed.), The notion of near islands - the Croatian Archipelago (pp. 215–248). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Kozak, M., Crotts, J. C., & Law, R. (2007). The impact of the perception of risk on international travellers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(4), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.607

- Krajnović, A., Zdrilić, I., & Miletić, N. (2021). Sustainable development of an island tourist destination: Example of the island of Pag. Academica Turistica, 14(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.26493/2335-4194.14.23-37

- Kušen, E. (2001). Hrvatski otoci u deset slika. Prilog procjeni utjecaja turizma na razvoj hrvatskih otoka. Sociologija Sela, 39(1–4), 109–150.

- Lankford, S., & Howard, D. (1994). Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90008-6

- Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00024-0

- Lepp, A. (2007). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi Village. Uganda. Tourism Management, 28(3), 876–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.004

- Ma, X., de Jong, M., Sun, B., & Bao, X. (2020). Nouveauté or Cliché? Assessment on island ecological vulnerability to Tourism: Application to Zhoushan, China. Ecological Indicators, 113, 106247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106247

- McElroy, J. L., & de Albuquerque, K. (1998). Tourism penetration index in small Caribbean islands. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 145–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00068-6

- McGehee, N., & Andereck, K. (2004). Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268234

- McHugh, M. (2013). The Chi-square of independence. Biochemia Medica, 23(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2013.018.

- Miternique, H. C. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 effects on tourism. The recovery of regional complexity: When less means more: The case of Balearic Islands. Research in Globalization, 3, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100051

- Monterrubio Cordero, J. C. (2008). Residents perception of tourism: A critical theoretical and methodological review. Ciencia Ergo Sum, 15, 35–44.

- Müller, M. (2019). The Impact of Technology on the Development of Tourism and the Prevention of Emigration of the Young Generation - Example of Okrug Gornji on the Island of Čiovo. In K. Jurčević, K. Lipovčan, O. Ramljak & R. Medić (Eds.), Reflections on the Mediterranean - book 2 (pp. 397–407). Institut društvenih znanosti Ivo Pilar.

- Neal, J. D., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2007). The effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507303977

- Niewiadomski, P. (2020). COVID-19: From temporary de-globalization to a re-discovery of tourism? Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757749

- Novelli, M., Gussing Burgess, L., Jones, A., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). No Ebola … still doomed: The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.03.006.

- Nunkoo, R., & So, K. K. F. (2016). Residents’ support for tourism: Testing alternative structural models. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 847–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515592972

- Official Gazette 34/1999. The Islands Act. Available online https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/1999_04_34_706.html.

- Official Gazette 116/2018. The Islands Act. Available online https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2018_12_116_2287.html.

- Parker, C., Scott, S., & Geddes, A. (2019). Snowball sampling. In P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug & Richard A. Williams (Eds.), Research design for qualitative research. SAGE. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036831710

- Payne, J. E., Gil-Alana, L. A., & Mervar, A. (2022). Persistence in Croatian tourism: The impact of covid-19. Tourism Economics, 28(6), 1676–1682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816621999969

- Pearson, K. (1900). On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. The Philosophical Magazine: A Journal of Theoretical Experimental and Applied Physics, 50(302), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440009463897

- Persson-Fischer, U., & Liu, S. (2021). The impact of a gloabal crisis on areas and topics of tourism research. Sustainability, 13(2), 906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020906

- Peters, M., Chan, C.-S., & Legerer, A. (2018). Local perception of impact-attitudes-actions towards tourism development in the Urlaubsregion Murtal in Austria. Sustainability, 10(7), 2360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072360

- Plackett, R. L. (1983). Karl Pearson and the Chi-squared Test. International Statistical Review / Revue Internationale de Statistique, 51(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/1402731

- Prideaux, B., Thompson, M., & Pabel, A. (2020). Lessons from COVID-19 can prepare global tourism for the economic transformation needed to combat climate change. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762117

- Qiu, R. T. R., Park, J., Li, S., & Song, H. (2020). Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102994.

- Ramkissoon, H. (2020). Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1858091

- Rua, V. S. (2020). Perceptions of tourism: A study of residents’ attitudes towards tourism in the city of Girona. Journal of Tourism Analysis: Revista de Análisis Turístico, 17(2), 165–184.

- Sharma, G. D., Thomas, A., & Paul, J. (2021). Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100786

- Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

- Shen, K., & Yang, J. (2022). Residents’ support for tourism amidst the COVID-19 era: An application of social amplification of risk framework and knowledge, attitudes, and practices theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063736

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- Sirakaya, E., Teye, V., & Sönmez, S. (2002). Understanding residents’ support for tourism development in the Central Region of Ghana. Journal of Travel Research, 41(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750204100109

- Sirgy, M. J., Kruger, P. S., Lee, D. J., & Yu, G. B. (2011). How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? Journal of Travel Research, 50(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362784

- Snaith, T., & Haley, A. (1999). Residents’ opinions of tourism development in the historical city of York. Tourism Management, 20(5), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00030-8

- Starc, N. (Ed.). (2017). Analitička podloga za izradu novog Zakona o otocima. Ekonomski institut, Zagreb.

- Starc, N. (2000). Managing sustainable development on the Croatian islands-documents, problems and perspectives. Periodicum Biologorum, 102(1), 199–209.

- Starc, N., & Stubbs, P. (2014). No island is an island: Participatory development planning on the Croatian islands. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 9(2), 158–176. https://doi.org/10.2495/SDP-V9-N2-158-176

- Škare, M., Soriano, D. R., & Porada-Rochoń, M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 163, 120469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120469.

- Šulc, I., & Fuerst-Bjeliš, B. (2021). Changes of tourism trajectories in (post)covidian world: Croatian perspectives. Research in Globalization, 3, 100052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100052

- Šulc, I. (2020). Tourism in protected areas and the transformation of Mljet island. In M. Koderman & V.T. Opačić (Eds.), Challenges of tourism development in protected areas of Croatia and Slovenia (pp. 75–102). Založba Univerze na Primorskem and Hrvatsko geografsko društvo.

- Šulc, I. (2017). Modificirani razvojni ciklus post-socijalističkih jadranskih otoka: Primjer otoka Mljeta. Acta Turistica, 29(1), 33–73. https://doi.org/10.22598/at/2017.29.1.33

- The Institute of Economics, Zagreb (2018). Sektorske analize – Turizam. https://www.eizg.hr/userdocsimages/publikacije/serijske-publikacije/sektorske-analize/SA_turizam_studeni_2018.pdf.

- Torales, J., O'Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020915212.

- Turner, S. (2020). Near Islands of Europe. In N. Starc (Ed.) The Notion of Near Islands - The Croatian Archipelago (pp. 29–53). Rowman&Littlefield.

- UNWTO. (2020a). Impact assessment of the COVID-19 outbreak on international tourism, https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-oninternational-tourism.

- UNWTO. (2020b). https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-arrivals-could-fall-in-2020.

- UNWTO. (2021). 2020: Worst year in Tourism history with 1 billion fewer international arrivals, https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2021-01/210128-barometer-en.pdf?GaI1QTYG.Ky9LDZ2tlDKc.iRZkinJeuH

- Vidučić, V. (2007). Održivi razvoj otočnog turizma Republike Hrvatske. Naše More, 54(1–2), 42–48.

- Wang, J., Liu-Lastres, B., Ritchie, B. W., & Mills, D. J. (2019). Travellers’ self-protections against health risks: An application of the full Protection Motivation Theory. Annals of Tourism Research, 78, 102743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102743

- Wang, S., & Xu, H. (2015). Influence of place-based senses of distinctiveness, continuity, self-esteem and self-efficacy on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Tourism Management, 47, 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.007

- Weber, S., Horak, S., & Mikačić, V. (2001). Tourism development in the Croatian Adriatic islands. In D. Ioannides, Y. Apostolopoulos & S. Sevil (Ed.). Mediterranean islands and sustainable tourism development. Practices, management and policies (pp. 171–192). Continuum.

- Williams, A. M., & Baláž, V. (2013). Tourism, risk tolerance and competences: Travel organization and tourism hazards. Tourism Management, 35, 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.07.006

- Woo, E., Kim, H., & Uysal, M. (2015). Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 50(C), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.11.001

- Wu, C.-H. (2021). A study on the current impact on island tourism development under COVID-19 epidemic environment and infection risk: A case study of Penghu. Sustainability, 13(19), 10711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910711

- Yang, Y., Zhang, H., & Chen, X. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102913