?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study investigates the impact of digitalization adoption on tax evasion and tests the moderation effect of corruption on this relationship. The World Bank’s digitalization adoption index is used to measure the level of digitalization adoption, and the shadow economy is chosen as a proxy for tax evasion. The research is conducted based on a comprehensive dataset including data from 133 countries. The results indicate a negative and significant relationship between tax evasion and digitalization adoption of businesses and people, which indicates that digitalization helps to reduce tax evasion. Additional results show that digitalization is highly effective in reducing tax evasion in low-corruption countries compared to high-corruption countries. Our findings are potentially useful for policymakers in identifying digitalization as an effective tool for deterring financial crimes. Investment in technology can help in increasing tax revenues and allow governments to be more efficient in allocating resources.

1. Introduction

Technological improvements and digitalization have influenced the tax collection processes worldwide by improving the speed, quality, and accuracy of the data and changing the ways of reporting, controlling, and auditing the taxes. Tax authorities, policymakers, regulators, accountants, and taxpayers have realized the opportunities of digitalization and started to get benefits from e-services, applications, websites, software, etc. Digitalization may reduce tax fraud by enhancing information collection, improving the control tools, and increasing efficiency while giving new opportunities for evading the tax.

This study first investigates the impact of digitalization adoption on tax evasion. Then we test the moderating effect of corruption in the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion. Additionally, we compare high-corrupt and low-corrupt environments regarding digitalization and tax evasion. In this research, digitalization adoption refers to the adoption of digital technologies such as the internet, mobile phones, and all other tools used by the economy and is measured by the Digital Adoption Index (DAI) developed by World Bank. This index is a composite one that represents the intensity of the digitalization of business, people, and government and covers the majority of the countries worldwide. Our paper is the first to use this index to test the impact of digitalization on tax evasion to the best of our knowledge. With regards to the other variables used for the study, the shadow economy index is used as a proxy for tax evasion (Medina et al., Citation2018), and the Control of Corruption (COC) index disclosed by the World Bank is used to test the corruption level in the countries.

Our findings suggest that digitalization is an effective tool to reduce tax evasion behavior. The results show a negative relationship between tax evasion and the digitalization adoption of businesses and people. Additional results highlighted that digitalization reduces tax evasion in high and low corrupt environments. However, it is more effective in countries characterized by low levels of corruption.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study testing the impact of different dimensions of digitalization adoption, including the digitalization of business, people, and government, on tax evasion. Another significant contribution to the literature is considering the effect of a corrupt environment on the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion.

Overall, our findings have important practical implications. The results could be helpful for policymakers in identifying digitalization as an effective tool to reduce tax evasion. However, the findings could also be considered a red flag to the regulators since we found that a high corrupt environment reduces the effectiveness of digitalization in deterring tax evasion. So, corruption is an obstacle for societies, and it would be better for governments to find solutions to reduce its levels to decrease tax evasion.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review and develops the hypothesis. Section 3 describes the research design. Section 4 presents the empirical results and discussion. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Tax evasion

In the literature, the definition of tax evasion is always given in contrast to tax avoidance. Evading tax is a deliberate action by which taxpayers use fraudulent means to escape paying taxes (Alm, Citation2012; Alm et al., Citation2016; Sandmo, Citation2005). Thus, the intention is to make a false representation of reality and make things completely different from what they are supposed to be. Conversely, avoiding the tax aims to reduce taxes using legal tools and means (Alm, Citation2012; Alm et al., Citation2016; Khlif & Achek, Citation2015). Therefore, individuals are allowed to shape and preplan events to decrease or underestimate their tax liabilities within the law conditions (Alm, Citation2012; Alm et al., Citation2016). According to Kemsley et al. (Citation2022), two fundamental conditions should be met to define a tax evasion act. First, there must be a willful action of paying fewer taxes, and second, there must be an underestimation of the tax base. Accordingly, tax evasion will not occur if one of these conditions is not verified.

Recently, a growing body of research focused on the determinants of tax evasion provided evidence that tax evasion is driven by economic and non-economic factors (Gabor, Citation2012; Riahi-Belkaoui, Citation2004; Richardson, Citation2006, Citation2008; Tsakumis et al., Citation2007). Building upon these studies, Khlif and Achek (Citation2015) and Khlif et al. (Citation2016) classified those determinants into four-factor groups: demographic factors (age, gender, education, urbanization, religion, and unemployment), cultural and behavioral factors (tax morale, culture, masculinity, individualism and uncertainty avoidance), legal and institutional factors (corruption, legal system, and bureaucracy), and economic factors (economic development, economic freedom, and inflation). Economic freedom is one of the most important economic factors influencing tax evasion behavior. Riahi-Belkaoui (Citation2004) and Tekin et al. (Citation2018) mentioned that the free economy offers more opportunities for people to be productive, which leads to low tax evasion. Savić et al. (Citation2015) found tax administration efficiency has a significant effect on tax evasion. Angour and Nmili (Citation2019) analyzed the other economic factors, such as openness rate, tax burden, urbanization, agricultural sector, and unemployment, affecting tax evasion.

Another stream of research in the corporate taxation field focused on the impact of tax evasion on the economy and its implications. Previous work provides evidence that evading taxes is extremely costly and has negative economic consequences worldwide (Abdixhiku et al., Citation2017; Gaspar & Hagan, Citation2016; Janeba & Peters, Citation1999; Mitchell & Sikka, Citation2011). Indeed, in modern economies, taxation is considered the most critical source of government revenue in most countries (Abdixhiku et al., Citation2017; Mitchell & Sikka, Citation2011; Ozili, Citation2020). Governments use tax revenues to provide a wide range of social programs and public investments to their citizens to improve the country’s social well-being and economic growth and development (Abdixhiku et al., Citation2017; Gaspar & Hagan, Citation2016; Riahi-Belkaoui, Citation2004). For this reason, tax evasion behavior is found to be a severe issue for societies. Evading taxes make governments struggle as it undercuts public funding (Mitchell & Sikka, Citation2011; Picur & Riahi‐Belkaoui, Citation2006), leading to a devastating impact on the economic development of the countries. Therefore, finding the best strategies to reduce the adverse effects of this phenomenon is a constant governmental concern. Governments are constantly seeking ways to deter tax evasion and strengthen tax compliance. They tried different policies to reduce all kinds of corruption, including tax evasion behavior. Some of these policies have goals to improve the services and develop informational infrastructure.

It is noteworthy that the main challenge faced by governments is how to track taxpayers’ activities and revenues and how to verify the accuracy of their reports. The reason behind this is that they couldn’t collect comprehensive and opportune information about the taxable income because, in the business environment, ‘transactions were in cash, so that there was no “paper trail” that could be used’ (Alm, Citation2021). Accordingly, digitalization would be a key solution enabling governments to collect correct and exhaustive information and track and analyze transactions to prevent fraud and tax evasion (Alm, Citation2021; Kitsios et al., Citation2022). Within this context, Uyar et al. (Citation2021) examined the effects of innovations in the public administration domain and confirmed that the adoption of e-government services improves government efficiency and contributes to reducing tax evasion. The authors argued that the digital transformation of public services makes public organizations more transparent and accountable.

2.2. Digitalization

Brenner and Hartl (Citation2021) discussed the definition of digitalization as a complex phenomenon. They mentioned a distinction between digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation, even though they are interrelated. While digitization is simply converting information into a digital format, digitalization ‘describes how the use of information and communications technology alters an organization’s business model, including creating new or improved ways of delivering services, communicating, and improving the quality of offerings’. Digital transformation is a more general term for using digital technologies to create entirely new business models. In this study, we use the term digitalization to explain the adoption of digital technologies such as the internet, mobile phones, and all other tools used by the economy.

There are different approaches to measuring the degree of digitalization in the literature. Kotarba (Citation2017) used five metrics to measure digitalization activities: Metrics for the digital economy, digital society, digital industry, digital enterprise, and digital clients. Digital Density Index (DDI), which was produced by Oxford Economics in partnership with Accenture Strategy, and Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), a composite index published annually by the European Commission, can be used to measure the digital economy. Bernhard et al. (Citation2018) constructed an index of four different indices: e-strategy, e-services, e-information/transparency, and e-interaction, to measure the degree of digitalization by using the national surveys.

Digitalization has inevitably changed the global economy and the finance sector as well. Digitalization in finance is adopting digital technologies and creating new business models for technology-enabled financial institutions. For example, financial institutions have started to use machine learning tools to detect and reduce fraud and money laundering and discover anomalies in transactions (Alam et al., Citation2019). Pakhnenko et al. (Citation2021) used Digital Financial Services Index, which has three components such as digital inclusion, financial inclusion, and digital financial services, to evaluate the degree of digitalization in the financial sector. The other index used to assess the degree of digitalization of the financial services is FinTech Adoption Index developed by EY and FinTech Index developed by the ING Bank. Khera et al. (Citation2021) offered a Digital Financial Inclusion in Emerging and Developing Economies covering 52 countries based on digital financial services’ access and usage.

The Digital Adoption Index (DAI), developed by the World Bank to determine the degree of digitalization, measures the digital adoption of the 180 countries worldwide based on three sub-indexes measuring the people, government, and business dimensions of the economy. The DAI has three subcategories: digitalization adoption by business (DAIB), digitalization adoption by people (DAIP), and digitalization adoption by the government (DAIG) (Digital Adoption Index, Citation2021). Researchers utilize DAI in their studies because it provides a more inclusive picture of digitalization adoption than other current sets of indices. It is more robust since it is based on World Bank’s internal databases than perception surveys (Al-Mulali et al., Citation2021). Ouedraogo and Sy (Citation2020) estimated the effect of digitalization on trust in tax officials and corruption and utilized the DAI to measure the extent of the spread of digital technologies worldwide.

2.3. Effects of digitalization on accounting and taxation

Digitalization has influenced accounting professionals with technological improvements since the traditional accounting practices transformed to information technology using accounting software. Knudsen (Citation2020) investigated the influence of digitalization on the accounting practice from different perspectives, such as digitalization’s impact on the boundaries of accounting, changing power relations, and effects of digitalization on the production of knowledge for decision making. Gulin et al. (Citation2019) analyzed the impact of digitalization on the development of the accounting profession. They mentioned that the digitalization of accounting and financial reporting improves accounting data speed, quality, and accuracy.

The governments realized the opportunities of digitalization and started to use information technologies and e-services to enhance efficiency and improve government services such as tax collection and auditing. Through software or integrated websites, the e-services of the public authorities provide reliable and quick processes, helping both accountants and customers access accounting information swiftly. With the advent of online e-government services being more widely used, online taxation services are now being utilized by integrating internet-based technologies. Following this, tax returns have begun being approved through online services. The governments may collect taxes swiftly, minimize tax evasion, and reduce the burden on the tax offices Kuzey et al. (Citation2019). The literature has discussed the adoption of e-government services related to tax accounting in different countries. Liang and Lu (Citation2013) investigated the adoption of e-government services in Taiwan and surveyed the taxpayers’ degree of acceptance of the online tax filing system. Kuzey et al. (Citation2019) examined the perception of the accountants on the e-government services in Turkey. Singh et al. (Citation2019) studied the e-government services for tax filing in India. Sijabat (Citation2020) investigated the perception of Indonesian taxpayers on the usefulness and the risk of e-government tax filing services. After discussing the changes in the public services caused by digitalization processes, Agostino et al. (Citation2022) mentioned that the technological developments are bringing new challenges for the users such as accountants, managers and policymakers.

2.4. Digitalization and tax evasion

The effects of digitalization on tax evasion are a current topic in the literature. Alm (Citation2021) investigated the effects of digitalization on tax evasion and argued that the changes in technology would increase the flow of information to governments; therefore, the governments’ ability to decrease tax evasion will be improved. But he also mentioned that some individuals or firms might find new ways to evade or avoid taxes with technological development. Empirical studies such as Hamilton and Stekelberg (Citation2017) found that information technology has a significant effect on corporate tax outcomes. They concluded that the firms with high-quality information technology could avoid more taxes while simultaneously incurring less tax risk than others. Kitsios et al. (Citation2022) found that digitalization reduces cross-border trade tax fraud by enhancing the information collection and processing by governments. Atayah and Alshater (Citation2021) stated that tax authorities could detect non-compliance cases and suspicious transaction by using the advanced technologies to mitigate tax evasion risk.

On the other hand, they also mentioned that digitalization might offer new tax evasion opportunities for individuals or firms by helping them to hide sensitive information. Strango (Citation2021) investigated the impact of digitalization of public services in European countries on tax evasion and found that tax evasion reduces with the increase of digitalization in public services, but only until a certain level. Beyond the mentioned level, tax evasion continues to increase.

With the technological developments, new techniques have been started to be used to detect tax evasion, such as data mining techniques (González & Velásquez, Citation2013; Wu et al., Citation2012), neural networks (Pérez López et al., Citation2019), social network analyses (Colladon & Remondi, Citation2017; Shaikh et al., Citation2021). Tax authorities employ emerging technologies such as big data, artificial intelligence, and blockchain (Atayah & Alshater, Citation2021).

This study contributes to the literature by empirically testing the impact of digitalization on tax evasion using the ‘Digital Adoption Index (DAI)’ developed by the World Bank. DAI is a comprehensive one, including the digitalization of business, people, and government and covering the majority of the countries worldwide.

Accordingly, we developed the following hypothesis to investigate whether digitalization is an effective tool to deter tax evasion or not.

H1: There is a negative relationship between digitalization and tax evasion.

H1a: There is a negative relationship between the digitalization of business and tax evasion.

H1b: There is a negative relationship between the digitalization of people and tax evasion.

H1c: There is a negative relationship between the digitalization of the government and tax evasion.

2.5. Corruption and tax evasion

Corruption is an act of criminal offense by an individual or an organization in a position of authority that offers or accepts an amount of money, services, or other valuables in exchange for an illicit act (Gaspar & Hagan, Citation2016). Nowadays, corruption has been recognized as one of the essential issues most countries face that should be addressed urgently. The reason behind that is highly corrupt societies; governments lose their capabilities to exercise their core functions, for instance, collecting funds from taxpayers. Indeed, this type of environment tolerates and encourages more tax evasion behavior (Gaspar & Hagan, Citation2016).

The corporate taxation literature agrees that corruption is a significant factor in tax evasion, and many international and country levels studies in this field provided evidence that widespread corruption drives higher levels of evasion (Ajaz & Ahmad, Citation2010; Alm & Liu, Citation2018; Amoh & Ali-Nakyea, Citation2019; Baum et al., Citation2017; Kurauone et al., Citation2020, Khyareh, Citation2019). Payne and Saunoris (Citation2020) supported the idea that the effect of corruption is more significant when tax evasion is more widespread. Alon and Hageman (Citation2013) stated that higher levels of corruption are always associated with lower levels of tax compliance. Additionally, Alm et al. (Citation2016) argued that tax evasion and corruption are intertwined and reinforcing. In more corrupt societies, the corrupt officials may search for bribery income which results in more tax evasion; conversely, if there is a higher level of tax evasion, there would be more opportunities for bribery which results in corruption. Therefore, control of corruption is considered an effective tool to control tax evasion (Picur & Riahi‐Belkaoui, Citation2006; Yamen et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). In fact, in a high corrupt environment, individuals are inclined to commit more financial crimes, implying a high level of tax non-compliance (Amara & Khlif, Citation2018; Khlif et al., Citation2016). In this regard, previous studies showed that informal institutions (which include the social influences and personal values) have the power to reduce tax evasion behavior by influencing taxpayers’ attitudes toward tax morality (DeBacker et al., Citation2015; Shafer & Wang, Citation2018; Torgler, Citation2005). However, when the level of corruption in a given country is high, the willingness and motivation of individuals to pay taxes decrease (Amara & Khlif, Citation2018; Amoh & Ali-Nakyea, Citation2019; Khlif et al., Citation2016). This is explained by the fact that when taxpayers believe that the government is untrusted, they will evade paying taxes (Richardson, Citation2008; Torgler, Citation2005; Torgler & Schneider, Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2009). Moreover, the traditional tools, such as audits, used to deter tax evasion are not effective in this type of environment because they mainly rely on people that can be themselves corrupted. When corruption is high, it would be better to minimize the interference of humans; therefore, digitalization would be an effective tool to reduce corruption and prevent tax evasion behaviors. In this regard, some studies highlighted that the use of technology by governments constitutes an anti-corruption tool for countries (Adam, Citation2020; Nam, Citation2018). Androniceanu et al. (Citation2022) analyzed the relationship between the level of e-government and control of corruption and government effectiveness. They suggested that digitizing the government is one of the most effective ways to reduce corruption. Uyar et al. (Citation2021) also argued that innovation in government services is an effective means to reduce corruption and, as a consequence, deter tax evasion behavior.

Based on the arguments mentioned above, our study investigates how the corruption level may moderate the relationship between tax evasion and digitalization. We expect the negative relationship to differ between high and low corrupted countries. Thus, our hypothesis is the following:

H2. The negative association between digitalization and tax evasion varies depending on the level of corruption.

3. Research design

3.1. Sample selection

The digitalization adoption index (DAI) is measured for 180 countries worldwide. The shadow economy is used as a proxy for tax evasion (TE) and is measured for 158 countries. All missed values have been removed, leading to a sample of 144 countries. After testing the outliers, 11 countries have also been removed (Azerbaijan, Bolivia, Cambodia, China, Gabon, Georgia, Iran, Nigeria, Peru, Thailand, and Uruguay). Accordingly, we included 133 countries in our sample. The sample consists of highly diversified countries regarding income level, geography, and cultural differences.

3.2. Research models and variables

We estimate a model that includes the digitalization adoption index as the main independent variable to test our hypotheses. Other variables that are used in the literature as determinants of tax evasion are also added to the model as control variables; inflation (INFLAT), unemployment (UNEMP), economic freedom (ECOFR), and urbanization (URBAN). presents all dependent and independent variables.

Table 1. Variable definition and sources.

We started our estimates by testing the relationship between the overall level of digitalization adoption and tax evasion (model 1). In the second stage, we performed a deep analysis to test the impact of all sub-variables of the digitalization adoption index separately (models 2 to 4). The main reason for using three different models for each sub-variable is the existence of multicollinearity between the digitalization of business (DAIB) and the digitalization of people (DAIP).

Our basic models are estimated as follows:

(model 1)

(model 1)

(model 2)

(model 2)

(model 3)

(model 3)

(model 4)

(model 4) Where:

TEi: Tax evasion for the country i;

DAIi: Digitalization adoption index for the country i;

DAIBi: Digitalization adoption index in business for the country i

DAIPi: Digitalization adoption index in people for the country i

DAIGi: Digitalization adoption index in government for the country i

CONTit: Control variables for the country i.

Coefficients of digitalization

Coefficients of control variables

3.3. Dependent variable

Following previous literature (Tsakumis et al., Citation2007; Yamen, Citation2021; Yamen et al., Citation2018, Citation2020), we used the shadow economy index as a proxy for tax evasion. Although the shadow economy can be measured directly and indirectly, we choose the indirect macroeconomic measure computed by Medina et al. (Citation2018). This measure is an updated version of the basic MIMIC approach. It replaces the GDP with the new light intensity method to capture the economic activities and avoid all previous criticism related to using the GDP as a cause and indicator, which can solve the endogeneity problem.

3.4. Independent and control variables

We used the Digital Adoption Index (DAI) developed by the World Bank to determine the degree of digitalization. This index covers 180 countries and is a composite of three sub-indexes measuring the people, government, and business dimensions of the economies. The first sub-index is the digitalization adoption by business (DAIB), which focuses on developing productivity and growth for businesses and measures the indicators related to business websites, secure servers, download speed, and network coverage. The second one is the digitalization adoption by people (DAIP) that uses indicators related the mobile access and internet access at home. The last one is the digitalization adoption by the government (DAIG), which focuses on the efficiency and accountability of the government services and measures factors related to core administrative systems, online public services, and digital identification (Digital Adoption Index, 2021).

In this study, we selected the DAI index, the most comprehensive index covering almost all countries in the world compared to other indexes that cover some groups of countries or are related to specific industries. In the literature, some recent studies in different fields used the DAI as the measure of the degree of digitalization (Al-Mulali et al., Citation2021; Ouedraogo & Sy, Citation2020; Pomaza-Ponomarenko et al., Citation2020; Skare & Soriano, Citation2021).

The definition of the control variables is given in .

3.5. Moderator

In this study, to test the moderation effect of corruption, we used the Control of Corruption (COC) Index disclosed by the World Bank, one of the six governance indicators produced by Kaufmann and Kraay (Citation2007). COC Index is preferred over the corruption perception index (CPI) because the COC index considers 13 additional datasets compared to CPI, which contains only nine datasets. The COC measures the perception of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption as well as capture the of the state by elites and private interest (Thomas, Citation2010, p. 33). 133 countries in our sample were divided into two categories: 66 ‘high-corruption countries’ and 67 ‘low- corruption’ countries after computing the median of the COC.

4. Empirical results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

This study uses cross-sectional analysis for data obtained from 133 countries (See appendix ). describes the descriptive statistics for dependent and independent variables. shows that the tax evasion (TE) average is 26.754 (SD = 10.566). A deep investigation of this average highlights that the average TE in high-corruption countries (33.802 (SD = 7.601)) is greater than the average mean of TE in low-corruption countries (19.812 (SD = 8.235)), which indicates that a corrupt environment increases the opportunity of committing financial crimes.

Table 2. Summary of descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables included in our model.

Regarding the adoption of digitalization, indicates that the overall average DAI is 0.544 (SD = 0.198) and that the average DAI in high-corruption countries (0.412 (SD = 0.15)) is lower than the average DAI in low-corruption countries (0.0.673 (SD = 0.149)).

Moreover, the descriptive statistics in show that low-corruption countries have a higher adoption rate of digitalization in all aspects compared to high-corruption countries.

4.2. Correlation matrix

displays the Pearson correlation matrix. Findings show a significant negative relationship between digitalization adoption and tax evasion. In addition, we found that all digitalization aspects, whether it is in business DAIB, people DAIP, or government DAIG, are negatively related to tax evasion and are highly significant. These results are considered preliminary support for our first hypothesis (H1, H1a, H1b, and H1c).

Table 3. Correlation matrix.

Further results show a significant negative (positive) relationship between tax evasion and economic freedom and urbanization (unemployment and inflation).

The correlation matrix indicates a correlation between the different types of digitalization, especially between DAIP and DAIB. Accordingly, we separated the sub-variables of digitalization while running our models. In addition, we addressed this issue through the variance inflation factor test (VIF) that will be expressed later.

4.3. Hypotheses testing and discussion

We developed four different models to test our hypotheses, as described in section 3.2. summarizes the four different regression results (columns 1 to 4) of the impact of digitalization adoption on tax evasion.

Table 4. Regression results of digitalization and tax evasion.

The Model 1 (M1) testing results for the overall digitalization index show a negative (coefficient: −23.29) and significant relationship at the 1% level between DAI and tax evasion. These findings corroborate our first hypothesis (H1) and confirm the importance of digitalization adoption in reducing tax evasion. Additional regression results related to the impact of the three sub-indexes of DAI on tax evasion testing for H1a, H1b, and H1c are given in (M2, M3, M4).

The results of Model 2 (M2) reveal a significant relationship at the 1% level with a negative coefficient (-22.25) between tax evasion and the digitalization adoption by business (DAIB). Finding related to Model 3 also shows a significant relationship at the 1% level with a negative coefficient (-22.98) between digitalization adoption by people (DAIP) and tax evasion. We noticed a slight difference between the coefficients of DAIB and DAIP, confirming that both tools are efficient in reducing tax evasion.

The results of Model 4 (M4) indicate that the digitalization adoption by the government (DAIG) does not have a significant impact on controlling tax evasion. We found that the relationship between DAIG and TE is insignificant.

Accordingly, the overall results highlight the importance of DAIB and DAIP in deterring tax evasion behavior and show that DAIG does not have a significant impact on reducing tax evasion based on our model. This implies that although digitalization is considered a crucial tool for preventing tax evasion behavior, governments should decide which tool they have to adopt that is more effective in ensuring tax compliance.

4.4. Testing the moderation effect of corruption

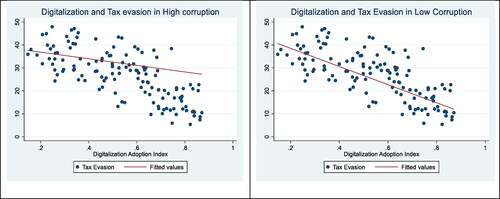

Corruption is expected to increase tax evasion behavior (Alm et al., Citation2016; Amoh & Ali-Nakyea, Citation2019; Cerqueti & Coppier, Citation2011; Khlif et al., Citation2016; Yamen, Citation2021). Accordingly, it was important to test the moderation effect of corruption on the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion. Thus, we divided the countries into high-corruption and low-corruption countries based on the median of the control of corruption index (-0.24). We started testing the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion in both high-corruption and low-corruption countries (). It was noticed that although the relationship was negative in both countries, the steepness of the curve in low-corruption countries is more remarkable than in high-corruption countries. This is considered as a primary result that digitalization is more efficient in reducing tax evasion behavior in low-corruption countries than in high-corruption countries.

Figure 1. The relationship between digitalization and tax evasion in low corruption and high corruption countries.

Source: Authors' Calculations.

summarizes the regression results. Model 5 (M5) tested the relationship between DAI and TE in high-corruption countries; the results showed a significant relationship at a 5% level with a negative coefficient (-26.3). Model 6 (M6) tested the same relationship for low-corruption countries; the results showed a highly significant relationship at a 1% level with a negative coefficient (-26.3). Comparing both results clarifies that digitalization in high-corruption corruption is less efficient than in low-corruption countries. Thus, corruption can mitigate the effect of digitalization on reducing tax evasion behavior. These results support the primary results and support our second hypothesis, H2.

Table 5. Regression results of digitalization and tax evasion in high-corruption and low-corruption countries.

Then, we tested the relationship between DAIB and TE in high-corruption countries in Model 7 (M7) and in low-corruption countries in Model 8 (M8). The results on M7 indicated a highly significant relationship at a 5% level with a negative coefficient (-16.34). The results of M8 reveal a significant relationship between DAIB and TE but at a 1% level with a negative coefficient (-30.41). Model 9 (M9) and Model 10 (M10) tested the relationship between DAIP and TE in both high-corruption and low-corruption countries. The results showed that the relationship between DAIB and TE is highly significant in low-corruption countries at a 1% level compared to high-corruption countries, which is only significant at a 10% level. Model 11 (M11) and Model 12 (M12) both models tested the relationship between DAIG and TE but at different corruption levels, and the results for both models were insignificant. This result is still consistent with our hypothesis, as digitalization adoption is more efficient in a low-corruption environment regardless of the types of digitalization adoption.

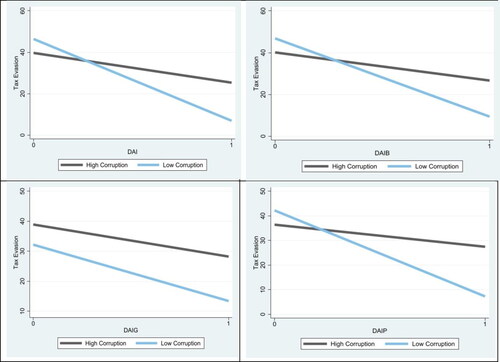

In addition, we analyzed the relationship between tax evasion and digitalization under high and low corruption for each of the sub-categories of digitalization (). The graphs support the statistical results as they illustrate that the slope of the relationship differs based on the corruption level, which indicates that corruption has a moderation effect on the relationship between tax evasion and DAI, DAIB, and DAIP. Also, the graph represents that there is no moderation effect of corruption on the relationship between tax evasion and DAIG. But it was clear that tax evasion is high in high-corruption countries compared to low-corruption countries.

Figure 2. The moderation effect of corruption on the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion (interaction plot).

Source: Authors' Calculations.

Then, for robustness purposes, we conducted further analysis by applying another approach rather than testing the relationship between tax evasion and DAI in both high corruption countries and low-corruption countries separately. We included corruption as a moderator in the full sample and tested the interaction effect. The results in revealed that corruption has a significant (-19.36**) moderation in effect in the relationship between tax evasion and DAI (Model 13), a significant (-17.31**) moderation effect on the relationship between tax evasion and DAIB (Model 14), and significant (-19.34***) moderation effect on the relationship between tax evasion and DAIP (Model 15). In addition, the results support earlier analysis that there is no moderation effect (-.5893) of corruption on the relationship between tax evasion and DAIG (Model 16). Again, this result is still consistent with our hypothesis, as digitalization adoption is more efficient in low-corruption countries and that the effect of corruption as a moderator differs based on the type of digitalization. The results imply that government should give more attention to the corruption level while preparing their budgets in order to clearly estimate the tax gap. Also, it is important that government should be careful in choosing the type of digitalization that will be used in deterring tax evasion and identify which type is more effective in reducing tax evasion.

Table 6. Testing the moderation effect of corruption on the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion.

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to examine the impact of digitalization on tax evasion. Additionally, we investigate the effect of corruption in moderating the relationship between tax evasion and digitalization in both high and low corrupt environments. To test our hypotheses, we used an international sample of 133 countries.

This research proves that the adoption of digitalization has a significant impact on deterring tax evasion behavior. Furthermore, there is evidence that the adoption of digitalization of people and businesses is much more effective in reducing tax evasion than the adoption of digitalization in government. Additional results confirm that corruption moderates the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion. Findings suggest that the adoption of digitalization is more effective in controlling tax evasion behavior in countries characterized by low corruption levels than those characterized by high levels of corruption. In this regard, the analysis displays that the steepness of the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion is higher in a low corrupt environment compared to a high-corrupt environment. This implies that corruption slows down the diminishing rate of tax evasion due to the digitalization adoption.

Our study makes the following contributions. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first to consider the impact of all digitalization aspects, including the digitalization of business, people, and government, on tax evasion. Also, this study is a pioneer in investigating the moderation effect of corruption on digitalization and tax evasion.

This research has implications for policymakers as it highlights the importance of digitalization in reducing tax evasion behavior. Especially in emerging countries, policymakers should work on speeding up the digitalization process to improve the efficiency of the tax collection and monitoring process. Although digitalization may bring additional setup costs for emerging economies, the benefits from investing in digitalization will exceed the costs. In addition, the study shows that governments should focus more on reducing corruption as it is found to be a barrier to reaching the optimal usage of digitalization in reducing and combating tax evasion.

The government should close the tax gap between the actual tax collections and tax estimations. Evaluating the level of corruption in the country is essential for the government to accurately estimate the tax revenues in the budget. Furthermore, the type of digitalization that government focuses on is also crucial to reducing tax evasion. As a result of this study, overall, the effect of digitalization adoption by people on tax evasion is more significant than the other categories. Therefore, each government should determine which type of digitalization is more effective in reducing tax evasion in that country.

Our study is subject to the limitation of estimates related to the use of shadow economy based on the MIMIC approach as a proxy for tax evasion. All estimation methods for tax evasion have their point of weakness and strengths (Schneider, Citation2019). Additionally, the use of the digitalization adoption index constitutes another limitation as we couldn’t test the time effect through a panel data analysis.

There is an opportunity for future research through testing the time effect of digitalization on tax evasion. In addition, the impact of institutional quality on moderating the relationship between digitalization and tax evasion can be investigated. Comparative studies can also be conducted to test the effects of digitalization on tax evasion in specific regions or periods.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abdixhiku, L., Krasniqi, B., Pugh, G., & Hashi, I. (2017). Firm-level determinants of tax evasion in transition economies. Economic Systems, 41(3), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2016.12.004

- Adam, I. O. (2020). Examining E-Government development effects on corruption in Africa: The mediating effects of ICT development and institutional quality. Technology in Society, 61, 101245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101245

- Agostino, D., Saliterer, I., & Steccolini, I. (2022). Digitalization, accounting and accountability: A literature review and reflections on future research in public services. Financial Accountability & Management, 38(2), 152–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12301

- Ajaz, T., & Ahmad, E. (2010). The effect of corruption and governance on tax revenues. The Pakistan Development Review, 49(4II), 405–417. https://doi.org/10.30541/v49i4IIpp.405-417

- Alam, N., Gupta, L., & Zameni, A. (2019). Digitalization and disruption in the financial sector. In Alam, N., Gupta, L., & Zameni, A. (Eds.) Fintech and Islamic Finance (pp. 1–9). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Alm, J. (2012). Measuring, explaining, and controlling tax evasion: Lessons from theory, experiments, and field studies. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-011-9171-2

- Alm, J. (2021). Tax evasion, technology, and inequality. Economics of Governance, 22(4), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-021-00247-w

- Alm, J., & Liu, Y. (2018). Corruption, taxation, and tax evasion. Tulane Economics Working Paper Series No: 1802. Tulane University. http://repec.tulane.edu/RePEc/pdf/tul1802.pdf

- Alm, J., Martinez-Vazquez, J., & McClellan, C. (2016). Corruption and firm tax evasion. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 124, 146–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.10.006

- Al-Mulali, U., Solarin, S. A., Andargoli, A. E., & Gholipour, H. F. (2021). Digital adoption and its impact on tourism arrivals and receipts. Anatolia, 32(2), 337–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1856692

- Alon, A., & Hageman, A. M. (2013). The impact of corruption on firm tax compliance in transition economies: Whom do you trust? Journal of Business Ethics, 116(3), 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1457-5

- Amara, I., & Khlif, H. (2018). Financial crime, corruption and tax evasion: A cross-country investigation. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 21(4), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-10-2017-0059

- Amoh, J. K., & Ali-Nakyea, A. (2019). Does corruption cause tax evasion? Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 22(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-01-2018-0001

- Androniceanu, A., Georgescu, I., & Kinnunen, J. (2022). Public administration digitalization and corruption in the EU member states. A comparative and correlative research analysis. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 18(65E), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.24193/tras.65E.1

- Angour, N., & Nmili, M. (2019). Estimating shadow economy and tax evasion: Evidence from Morocco. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 11(5), 7–7. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v11n5p7

- Atayah, O. F., & Alshater, M. M. (2021). Audit and tax in the context of emerging technologies: A retrospective analysis, current trends, and future opportunities. The International Journal of Digital Accounting Research, 21, 95–128. https://doi.org/10.4192/1577-8517-v21_4

- Baum, M. A., Gupta, M. S., Kimani, E., & Tapsoba, M. S. J. (2017). Corruption, taxes and compliance. International Monetary Fund.

- Bernhard, I., Norström, L., Snis, U. L., Gråsjö, U., & Gellerstedt, M. (2018). Degree of digitalization and citizen satisfaction: A study of the role of local e‑Government in Sweden. Electronic Journal of e-Government, 16(1), 59–‑71.

- Brenner, B., & Hartl, B. (2021). The perceived relationship between digitalization and ecological, economic, and social sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 315, 128128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128128

- Cerqueti, R., & Coppier, R. (2011). Economic growth, corruption and tax evasion. Economic Modelling, 28(1–2), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2010.07.006

- Colladon, A. F., & Remondi, E. (2017). Using social network analysis to prevent money laundering. Expert Systems with Applications, 67, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2016.09.029

- DeBacker, J., Heim, B. T., & Tran, A. (2015). Importing corruption culture from overseas: Evidence from corporate tax evasion in the United States. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 122–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.11.009

- Digital Adoption Index. (2021). World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2016/Digital-Adoption-Index

- Gabor, R. (2012). Relation between tax evasion and Hofstede’s model. European Journal of Management, 12(1), 61–72.

- Gaspar, V., & Hagan, S. (2016). Corruption: Costs and mitigating strategies. International Monetary Fund Staff Discussion Note, SDN 16/05. US: International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513594330.006

- González, P. C., & Velásquez, J. D. (2013). Characterization and detection of taxpayers with false invoices using data mining techniques. Expert Systems with Applications, 40(5), 1427–1436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.08.051

- Gulin, D., Hladika, M., & Valenta, I. (2019). Digitalization and the Challenges for the Accounting Profession. In Proceedings of the ENTRENOVA-ENTerprise REsearch InNOVAtion Conference (Online).

- Hamilton, R., & Stekelberg, J. (2017). The effect of high-quality information technology on corporate tax avoidance and tax risk. Journal of Information Systems, 31(2), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.2308/isys-51482

- Janeba, E., & Peters, W. (1999). Tax evasion, tax competition and the gains from nondiscrimination: The case of interest taxation in Europe. The Economic Journal, 109(452), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00393

- Kaufmann, D., & Kraay, A. (2007). Governance indicators: Where are we, where should we be going? The World Bank Research Observer, 23(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkm012

- Kemsley, D., Kemsley, S. A., & Morgan, F. T. (2022). Tax evasion and money laundering: A complete framework. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(2), 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-09-2020-0175

- Khera, P., Ng, S. Y., Ogawa, S., & Sahay, R. (2021). Digital financial inclusion in emerging and developing economies: A new index. International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513584669.001

- Khlif, H., & Achek, I. (2015). The determinants of tax evasion: A literature review. International Journal of Law and Management, 57(5), 486–497. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-03-2014-0027

- Khlif, H., Guidara, A., & Hussainey, K. (2016). Sustainability level, corruption and tax evasion: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Financial Crime, 23(2), 328–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-09-2014-0041

- Khyareh, M. M. (2019). A cointegration analysis of tax evasion, corruption and entrepreneurship in OECD countries. Economic Research/Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 3627–3646. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1674175

- Kitsios, E., Jalles, J. T., & Verdier, G. (2022). Tax evasion from cross-border fraud: Does digitalization make a difference? Applied Economics Letters, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2022.2056566

- Knudsen, D.-R. (2020). Elusive boundaries, power relations, and knowledge production: A systematic review of the literature on digitalization in accounting. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 36, 100441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accinf.2019.100441

- Kotarba, M. (2017). Measuring digitalization: Key metrics. Foundations of Management, 9(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1515/fman-2017-0010

- Kurauone, O., Kong, Y., Mago, S., Sun, H., Famba, T., & Muzamhindo, S. (2020). Tax evasion, political/public corruption and increased taxation: Evidence from Zimbabwe. Journal of Financial Crime, 28(1), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-07-2020-0133

- Kuzey, C., Dinc, M. S., Gungormus, A. H., & Incirkus, L. (2019). Quality in e-Government accounting services: A model of relationships between e-service quality dimensions and behaviors. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 12(23), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.17015/ejbe.2019.023.04

- Liang, S. w., & Lu, H. p (2013). Adoption of e‐government services: An empirical study of the online tax filing system in Taiwan. Online Information Review, 37(3), 424–442. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-01-2012-0004

- Medina, L., Schneider, F., & Fedelino, A. (2018). Shadow economies around the world: What did we learn over the last 20 years? International Monetary Fund.

- Mitchell, A., & Sikka, P. (2011). The pin-stripe mafia: How accountancy firms destroy societies. Association for Accountancy & Business Affairs.

- Nam, T. (2018). Examining the anti-corruption effect of e-government and the moderating effect of national culture: A cross-country study. Government Information Quarterly, 35(2), 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.01.005

- Ouedraogo, R., & Sy, M. A. N. (2020). Can digitalization help deter corruption in Africa? International Monetary Fund.

- Ozili, P. K. (2020). Tax evasion and financial instability. Journal of Financial Crime, 27(2), 531–539. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-04-2019-0051

- Pakhnenko, O., Rubanov, P., Hacar, D., Yatsenko, V., & Vida, I. (2021). Digitalization of financial services in European countries: Evaluation and comparative analysis. Journal of International Studies, 14(2), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2021/14-2/17

- Payne, J. E., & Saunoris, J. W. (2020). Corruption and firm tax evasion in transition economies: Results from censored quantile instrumental variables estimation. Atlantic Economic Journal, 48(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-020-09666-2

- Pérez López, C., Delgado Rodríguez, M. J., & de Lucas Santos, S. (2019). Tax fraud detection through neural networks: An application using a sample of personal income taxpayers. Future Internet, 11(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi11040086

- Picur, R. D., & Riahi-Belkaoui, A. (2006). The impact of bureaucracy, corruption and tax compliance. Review of Accounting and Finance, 5(2), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/14757700610668985

- Pomaza-Ponomarenko, A. L., Hren, L. M., Durman, O. L., & Bondarchuk, N. (2020). Management mechanisms in the context of digitization of all spheres of society. Revista San Gregorio, 2020(42), 1–9.

- Riahi-Belkaoui, A. (2004). Relationship between tax compliance internationally and selected determinants of tax morale. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 13(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2004.09.001

- Richardson, G. (2006). Determinants of tax evasion: A cross-country investigation. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 15(2), 150–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2006.08.005

- Richardson, G. (2008). The relationship between culture and tax evasion across countries: Additional evidence and extensions. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 17(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2008.07.002

- Sandmo, A. (2005). The theory of tax evasion: A retrospective view. National Tax Journal, 58(4), 643–663. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2005.4.02

- Savić, G., Dragojlović, A., Vujošević, M., Arsić, M., & Martić, M. (2015). Impact of the efficiency of the tax administration on tax evasion. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 28(1), 1138–1148. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2015.110083

- Schneider F. (2019). Size of the shadow economies of 28 European Union countries from 2003 to 2018. In V. Vlachos & A. Bitzenis (eds.), European Union. Post Crisis Challenges and Prospects for Growth (pp. 111–121). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shafer, W. E., & Wang, Z. (2018). Machiavellianism, social norms, and taxpayer compliance. Business Ethics: A European Review, 27(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12166

- Shaikh, A. K., Al-Shamli, M., & Nazir, A. (2021). Designing a relational model to identify relationships between suspicious customers in anti-money laundering (AML) using social network analysis (SNA). Journal of Big Data, 8(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00411-3

- Sijabat, R. (2020). Analysis of e-government services: A study of the adoption of electronic tax filing in Indonesia. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial Dan Ilmu Politik, 23(3), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.22146/jsp.52770

- Singh, H., Kar, A. K., & Ilavarasan, P. V. (2019). Adoption of e-Government services: A case study on e-Filing system of income tax department of India. In A. Tripathy, R. N. Subudhi, S. Patnaik, & J. Nayak (eds.), Operations Research in Development Sector. Asset Analytics. (pp. 109–123). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1954-9_8

- Skare, M., & Soriano, D. R. (2021). How globalization is changing digital technology adoption: An international perspective. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 6(4), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2021.04.001

- Strango, C. (2021). Does digitalisation in public services reduce tax evasion? MPRA Paper No. 106856. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/106856/

- Tekin, A., Güney, T., & Sağdiç, E. N. (2018). The effect of economic freedom on tax evasion and social welfare: An empirical evidence. Yönetim ve Ekonomi: Celal Bayar Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, 25(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.18657/yonveek.299237

- Thomas, M. A. (2010). What do the worldwide governance indicators measure? The European Journal of Development Research, 22(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2009.32

- Torgler, B. (2005). Tax morale in Latin America. Public Choice, 122(1–2), 133–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-005-5790-4

- Torgler, B., & Schneider, F. (2005). Attitudes towards paying taxes in Austria: An empirical analysis. Empirica, 32(2), 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-004-8328-y

- Torgler, B., & Schneider, F. (2007). What shapes attitudes toward paying taxes? Evidence from multicultural European countries. Social Science Quarterly, 88(2), 443–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00466.x

- Torgler, B., & Schneider, F. (2009). The impact of tax morale and institutional quality on the shadow economy. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2008.08.004

- Tsakumis, G. T., Curatola, A. P., & Porcano, T. M. (2007). The relation between national cultural dimensions and tax evasion. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 16(2), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2007.06.004

- Uyar, A., Nimer, K., Kuzey, C., Shahbaz, M., & Schneider, F. (2021). Can e-government initiatives alleviate tax evasion? The moderation effect of ICT. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, 120597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120597

- Wu, R.-S., Ou, C.-S., Lin, H-y., Chang, S.-I., & Yen, D. C. (2012). Using data mining technique to enhance tax evasion detection performance. Expert Systems with Applications, 39(10), 8769–8777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.01.204

- Yamen, A. E. (2021). Tax evasion, corruption and COVID-19 health risk exposure: A cross country analysis. Journal of Financial Crime, 28(4), 995–1007. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-10-2020-0220

- Yamen, A., Allam, A., Bani-Mustafa, A., & Uyar, A. (2018). Impact of institutional environment quality on tax evasion: A comparative investigation of old versus new EU members. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 32, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2018.07.001

- Yamen, A. E., Mersni, H., & Ramadan, A. (2020). Tax evasion and public governance before and after the European “big bang”: A red flag for policymakers. Journal of Financial Crime, https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-04-2020-0064

Appendix

Table A1. Data collected for the countries included in study sample.