Abstract

The popularity of local foods is increasing among the masses, especially tourists, and this has led to the inception of ‘locavorism’ where the consumers – termed locavores – look for sustainable local foods. We gauge tourists’ ideology of locavorism through the lens of agritourism in India as we found it crucial to highlight and enhance local foods as an addition to the tourists’ palate. A pre- and post-survey was conducted using repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to empirically assess 8 Agritourism farms’ tourists’ behaviour towards locavorism. Data was collected among tourists by using a self-report questionnaire during two phases (check-in and check-out; n = 344). Findings underscore that tourists’ intention to buy local food increases considerably after experiencing Agritourism. This study is the first of its kind to understand the perception of tourists towards India’s ethnic cuisine, its role in augmenting tourist experience, and in figuring out better ways to sustain local foods. The impact that Agritourism has on tourists’ behaviour towards locavorism and its continuing effects on the local economy needs to be studied by researchers. Future research can extend the concept of locavorism to service providers by understanding their perception of producing and marketing sustainable local foods.

1. Introduction

Modern India is one of the most diverse nations as a subcontinent that houses over one hundred dialects, more than seven hundred tribes, and heterogeneous geographies consisting of large cities, aesthetically pleasing towns, and culturally rich villages. The country carries tremendous potential to become one of the biggest tourism giants given its richness in resources, diversity, culture, traditions, and ethnicity. Tourists now look to unwind and enjoy an unworldly experience through escapades designed by the tourism industry. Such experiences are ethereal in nature and benefit the tourists—physically and mentally. Parallel to this phenomenon, agritourism has been the topic of strategic discussions among governments, policymakers, and researchers as a program for sustainable development (Jack et al., Citation2020). Agritourism can create a win-win scenario for tourists as well as service providers i.e. farmers, where the former quenches the thirst to enjoy the natural environment and the perks of an ethereal experience while the latter benefits through income earned beyond farming. Along with this, comes the variety offered in terms of cuisine and picturesque destinations. In the spectrum of cuisine through tourism, local foods, or Local Food Systems (LFS) is currently grabbing the limelight as consumers are looking for more than just satiating their hunger. Tourists are gradually showing interest in local foods because they are concerned about its origin and their belief oriented towards the value of local food (Birch et al., Citation2018), holistic benefits (Lillywhite & Simonsen, Citation2014), and individual socio-political ideologies about local foods (Huddart Kennedy et al., Citation2018). The most recent consumer ideology emerging into the world of academics and research associated with local food is a concept called ‘locavorism’ and people who believe in this concept i.e. prefer local food for consumption, are termed as ‘locavores’ (Kim & Huang, Citation2021; Reich et al., Citation2018).

The engagement of tourists in consuming and promoting local foods has been primarily studied in the context of cities and urban areas (Reich et al., Citation2018; Sadler et al., Citation2015) and the findings have highlighted that a tourist has great influence on promoting LFS that creates a favourable destination image (Dimitrovski & Crespi Vallbona, Citation2018) thus offering a surreal and ethereal experience to the tourists. Many authors have identified great potential in bringing together tourism and food production, especially local food production to enhance the destination image (Scheyvens & Laeis, Citation2021). In this context, agritourism—a flourishing vertical of the tourism sector—is the bridge that connects the two. Promoting LFS through agritourism opens a new window of opportunity for farm owners to venture into novel economic opportunities and promote local food among tourists that is rich in nutrition. For this to accelerate, there is a dire need for stakeholders to be rigorously educated about the benefits of LFS (Sakuta, Citation2020) through national and international bodies. In support of this, the tourism industry is encouraged to align with the ‘United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals’ corroborated in 2015, while considerable focus is concentrated on food systems.

In India, the concept of enjoying local food through tourism is becoming increasingly popular among not just international tourists but also domestic tourists (Shah, Citation2022) that gives the locals an opportunity to capitalize on the country’s copious culinary traditions (Kim et al., Citation2019). This encourages the tourists to add a personalized and warm ethereal experience to their itinerary that offers them an elaborate peek into what cooks in the Indian kitchens. The country is working towards developing agritourism as one of the core tourism verticals to encourage tourists to get acquainted not just with agricultural activities but also immerse themselves in various aspects of rural life such as local food, culture, traditions, arts, and sports (Shah, Citation2022). Consequently, offering such unique agritourism services enhances the destination image, affects tourists’ behaviour towards local food consumption (Alderighi et al., Citation2016; Choe & Kim, Citation2018), and connects the tourist to the authenticity of the local region that further enhances one’s experience (Sims, Citation2009; Zhang et al., Citation2019).

Local foods have been studied from the perspective of service-providing enterprises like restaurants and multinational food chains (Kim & Huang, Citation2021), but limited studies have focused on consumers. To the best of our knowledge, despite its potential, tourists’ perception of locavorism has not been probed in the context of Agritourism across India. In subsistence to this, tourism literature has identified the necessity to empirically measure the way consumer behaviour is shaped through tourism experience via local foods (Mair & Sumner, Citation2017). Therefore, this study aims towards understanding the perception of tourists towards India’s ethnic cuisine, its role in augmenting their experience, and in figuring out better ways to sustain local foods through enhanced culinary which can contribute towards the economic development of the local community.

2. Review of literature

2.1. Theoretical background

Ajzen’s (Citation1991) Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), derived from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) developed by Fishbein and Ajzen in 1975, has proven over and again to be one of the most influential theories to study tourist behaviour (Chen & Tung, Citation2014; Joo et al., Citation2020; Shin et al., Citation2018; Soliman, Citation2021). TPB is primarily based on three determinants that lead towards consumer’s behavioural intention—‘attitudes’, ‘perceived behavioural control’, and ‘subjective norms’. Attitudes are defined as ‘a summary evaluation of the behaviour captured in attribute dimensions as positive or negative’ (Ajzen, Citation2001). In the context of consumption of local food, a tourist’s attitude about buying or consuming local food could be negative or positive. Perceived Behavioural Control is defined as the ‘people’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour of interest’ (Ajzen, Citation1991). In the context of this study, it is related to a tourist’s knowledge on how easy or difficult it is, to purchase or find local food. Subjective norm is known as a ‘measure of a person’s beliefs about whether others who are significant in his or her life thinks if he or she should perform the behaviour or not’ (Conner & Armitage, Citation1998) otherwise known as ‘social pressure’ to perform or to not perform a given action or behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). For instance, a tourist or consumer might perceive that his or her social circle would be happy and approving of the individual’s behaviour towards buying local foods. Additionally, many authors have proposed and included ‘personal norms’ which is defined as, ‘self-construed expectations about carrying out an action in particular situations’ (Schwartz, Citation1977). Onel (Citation2017) substantiated the practicality of including personal norms in the TPB while determining consumers’ behavioural intention towards purchasing pro-environmental products. Therefore, we use the extended Theory of Planned Behaviour as our theoretical framework for our study.

2.2. Defining agritourism

Several studies have assessed the different aspects of agritourists and agritourism that show consistent growth in the academic interest to study the areas in and around it (Kim et al., Citation2019). Agritourism—a prudent blend of agriculture and tourism—has a powerful ability to improve the economic condition of the farmers, promote local food, maximize the utilization of existing resources, minimize investments, and decrease the impact of related activities on heritage and environment (Barbieri, Citation2013; McGehee, Citation2007; Musa & Chin, Citation2021). A comprehension of past literature reveals varied definitions and terms for agritourism. Terms like farm-based tourism, agrotourism, rural tourism, and farm tourism have not just been used as synonyms for agritourism (Barbieri et al., Citation2019; Barbieri & Mshenga, Citation2008; Phillip et al., Citation2010) but also to indicate similarly distinct ideas (Karampela et al., Citation2021; Rauniyar et al., Citation2021) resulting in a complex and unclear picture. Therefore, to offer a sense of consistency and clarity, the term used in this paper is agritourism and is defined as, ‘a rural establishment that combines agriculture with tourism and is a subset of a broader concept called Rural Tourism where the hosting house must be integrated into an agricultural estate, inhabited by the proprietor, allowing visitors to take part in agricultural or complementary activities on the property’.

2.3. Promoting sustainability through locavorism

Given that our study focuses on understanding tourist behaviour towards ‘local foods’, we found it necessary to define the same. A sustainable food system is defined as, ‘a collaborative effort to build more locally based, self-reliant food economies—one in which food production, processing, distribution, and consumption is integrated to enhance the economic, environmental, and social health of a particular place’ (Feenstra, Citation2002). This definition is suitable for our study since it is collaborative, participative, and place sensitive in nature with importance given to providers and consumers. In relation to the concept of ‘local foods’, ‘locavorism’ is a term currently used across various domains. Consumers whose ideologies emanate that consuming local food improves the local economy, supports local farmers, and safeguards the environment while also viewing local food as tastier and healthier (Kim & Huang, Citation2021) are termed as ‘locavores’. From the perspective of tourism, locavores play a pivotal role in shaping a major part of the local food system as they do not trust non-local food, believe that local food is superior in taste, and look forward to supporting the local economy through their choices during their tourism experience (Reich et al., Citation2018). Consuming food by not just eating it but also engaging in related aspects, encourages tourists to learn and understand the destination’s history and life that is deeply embedded in its culture. It has been concurred that food goes a long way in designing and attaining an ethereal experience to tourists as it is presented to stage an authentic experience of the destination (Horng & Tsai, Citation2012).

On the other hand, there has been growing apprehension that local traditions and food will be overshadowed and eventually buried by multinational and transnational corporations that are strengthening their foothold in the food and beverages industry. To conquer this, governments and a few organizations are trying to promote local food and heritage through one of the global service verticals i.e. tourism (Bisht et al., Citation2018). From the academic point of view, several strategies have been offered by researchers that facilitate the promotion of tourist engagement to support LFS. There have been calls to encourage spaces and dialogues among consumers that can bring about a visible change in their behaviour to extend a warm support towards the consumption of sustainable local food (Selfa & Qazi, Citation2005). Therefore, this study highlights the role of agritourism as a pillar that supports the promotion of locavorism among tourists in India.

2.4. Identifying research gaps

Evidence from past literature posits that agritourism has the potential to offer a platform for tourists to engage in sustainable LFS (Piramanayagam et al., Citation2020). First, the creation of a holistic image that includes tourists and their relation orientation towards local food has proved to have significantly contributed towards the plethora of knowledge associated with tourism and the LFS. Second, future behaviour influenced by past behaviour has been studied and is considered as a well-established relationship around tourist behaviour and food consumption (Brune et al., Citation2021; Choo & Petrick, Citation2014; Kline et al., Citation2016; Rahman et al., Citation2018). And third, there is an increase in the evidence that local food consumption plays a significant role in shaping an ethereal tourism experience (Hasselbach & Roosen, Citation2015). It has been found that tourists are often motivated to take part in activities related to agritourism to learn about local foods and agriculture. Therefore, it is a fair assumption that consumers’ willingness and awareness about locavorism and agricultural products is likely to increase during or after a farm visit. As this claim is not supported, we identify the first research gap. Subsequently, agritourism attributes like experience, providing opportunities to purchase goods on-,site, and teaching moments are believed to be effective at encouraging tourists to consume local food (Tew & Barbieri, Citation2012). Abundant literature proof shows that local food, especially legendarily delicious food and drinks, is one of the strongest components that shape tourism experience in an ethereal manner (Cafiero et al., Citation2020; Sosa et al., Citation2021). Albeit that, there is little knowledge that shows the effect of agritourism on tourist behaviours and attitude towards local food. Addressing these two gaps can go a long way in designing robust strategies to strengthen and support the LFS in the Indian Agritourism Industry.

Keeping the literature in view, we tested the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Experiencing Agritourism has a positive effect on,

1-A: attitudes associated with purchasing and consuming local food.

1-B: subjective norms associated with purchasing and consuming local food.

1-C: perceived behavioural control associated with purchasing and consuming local food.

1-D: personal norms associated with purchasing and consuming local food.

Hypothesis 2: Experiencing agritourism has a positive effect on behavioural intention associated with purchasing and consuming local food.

3. Materials and methods

We follow a deductive approach to examine the influence of agritourism experiences on tourist intention towards buying local food. This examination is an attempt to expand the existing knowledge of agritourism and offer prospective strategies to increase local food consumption among tourists in India. Agritourism across India is diverse in terms of its offerings that include varied cuisines and services. But the purpose of the study can be achieved given the presence of shared similarities between the agritourism establishments spread across the country.

The rationale behind choosing the sample:

Local food is served at the agritourism centre.

Educational activities like guided tours or self-tours accompanied by signages are conducted on the farm.

Any one kind of hands-on rural or agricultural experience like pick-your-own, petting animals, assisting in cooking, participation in agricultural activities, etc., is offered to the tourists.

Recreational space for children like a small park, playground, games arena, etc.

Easy access to stores and restaurants selling local merchandise and locally made food products/items respectively.

From the list retrieved from state Tourism Departments, we called up 24 registered agritourism establishments located in 8 Indian States viz., Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra, Punjab, Gujarat, Uttarakhand, Arunachal Pradesh, and Meghalaya to identify the farms that met the above-mentioned criteria. Farm owners were asked if they were willing to be part of the study. Upon affirmation, we assessed the area in acres, type of crops and/or animals grown/bred, past generations involved in farming, total experience in agritourism, duration of functionality, type of agritourism activities offered to tourists, and inclusion of locally manufactured or produced food provided to tourists. Based on this general assessment, a total of one agritourism establishment each, from every state were selected and were further contacted to encourage the visiting tourists to provide required data as study participants.

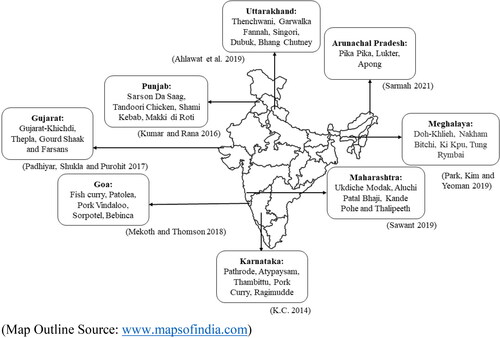

With reference to the tourism industry, food most certainly plays a significant role in enhancing tourist experience and making it ethereal, and in a country as richly diverse as India, not just in terms of its cultures, traditions, and destinations but also food, it is important to highlight and enhance local foods as an addition to the tourists’ palate. represents the local foods associated with the 8 states chosen for the study.

Figure 1. Representation of local foods in states chosen for the study.

(Map Outline Source: www.mapsofindia.com)

represents the main attributes of the farm sites. Survey Questionnaires were provided before and after the tourists had a holistic experience at the agritourism establishment. The first set of questionnaires (pre) were given to the tourists as they checked in to the farm that they were staying in, and the second set of questionnaires (post) were handed over at check-out. Only 1 set of questionnaires was given to one visiting party to be filled by any one individual representing the group/couple/family.

Table 1. Main attributes of the farm sites.

3.1. Items and measures

With the Theory of Planned Behaviour as the foundation, a survey instrument comprising of a series of 5-point Likert scale was framed to understand tourists’ behavioural intention towards buying and/or consumption of local food. Based on enduring literature (Denver & Jensen, Citation2014; Hempel & Hamm, Citation2016; Shin et al., Citation2018), the survey consisted of 23 items that are tailored to suit our study. shows the questionnaire design in detail.

Table 2. Questionnaire design.

represents the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample population. Following this, an individual code was assigned to every respondent in a dedicated section of the form so as to pair the pre and post-test surveys methodically. Adhering to a pre-post framework, the surveys were taken before and after the tourists experienced agritourism and associated activities. As the primary aim was to assess the influence of experiencing agritourism on tourists during a single visit or stay, administering the questionnaire during check-in and check-out i.e. before and after the experience allowed us to aptly measure the changes in many instances irrespective of the tourists’ prior experiences in agritourism or similar facilities. Both the instruments i.e. pre and post contained the same variables with regards to ‘attitudes’, ‘perceived behavioural control’, ‘subjective norms’ and ‘personal norms’.

Table 3. Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents.

Data collected from the pre, and post-test surveys were downloaded and paired manually using birthdates and initials so as to make a merged document with pre and post responses in the same file. The merged file was later exported to SPPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) for the purpose of descriptive (mean) and multivariate analysis (MANOVA). A total of 344 tourists responded to both pre and post-test surveys that left no room for deletion thus giving a 100% completion rate. In the SPSS software, the data went through multiple stages of systematic analysis such as descriptive statistics (to examine the means of items linked to individual constructs), reliability tests (to compute Cronbach’s alpha for testing the reliability and internal consistency of scales) and concluded with repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance (Rep-MANOVA conducted to test the change in individual constructs). With reference to reliability tests, values >0.6 indicated that all the items were deemed to be internally consistent scales. Ultimately, Rep-MANOVA was conducted to test the hypothesis i.e. the changes that occurred in attitudes, perceived behavior control, subjective norms, personal norms (H1), and intended behavior (H2) towards local food before and after experiencing agritourism (p < 0.05).

4. Results

Deriving the data from , it is comprehended that 50.6% of the study participants were women while a predominant percentage of participants i.e. 89.5% belonged to the age group of below 25 years. 45.9% of the tourists were post-graduates while the annual household income was reported as less than five lacs with 66.9% of the tourists under this income bracket.

4.1. Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control before and after experiencing agritourism

illustrates the various parameters associated with our study. The Cronbach’s alphas indicate that there is strong internal reliability with reference to all the scales of the Theory of Planned Behaviour that includes ‘attitudes towards buying local food’ (α = 0.76), ‘attitudes toward local food’ (α = 0.713), ‘subjective norms’ (α = 0.806), ‘perceived behavioral control’ (α = 0.717) and ‘personal norms’ (α = 0.739). Holistically, from the pre-test survey, tourists reflected positive attitudes towards buying local food and also local food (M = 4.09 and M = 4.27 respectively) with the average scores above 4 except for ‘positive environmental impact’ (M = 3.84) and ‘safeguard agricultural landscape’ (M = 3.78). On the other hand, subjective norms (M = 3.92) and perceived behavioural control (M = 3.82) presented scores below 4 for most of the items that fall under its purview except for ‘approval to buy local food’ (M = 4.12), ‘often purchase local food’ (M = 4.06) and ‘affordable’ (M = 4.08). Personal norms presented mean below 4 (M = 3.91) but the items under the construct reflected scores above 4 except ‘connect with local producers and farmers’ (M = 3.42) which is also the lowest score among all the items.

Table 4. Changes in attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control and personal norms pre and post experiencing agritourism (Rep-MANOVA).

Rep-MANOVA showed visible changes in tourists’ attitudes toward buying local food before and after experiencing agritourism as Wilks’s Lambda = 0.961, F = 13.735 and p < 0.001). Under this construct, results from the post hoc univariate tests indicate significant changes only in items ‘positive environmental impact’ (Mpre = 3.840; Mpos = 4.270; p < 0.001) and ‘safeguard agricultural landscape’ (Mpre = 3.720; Mpost = 4.070; p < 0.001). The second construct i.e. attitude towards local food showed lesser change before and after experiencing agritourism where Wilks’s Lambda = 1.000; F = 0.880; p = 0.767 and the univariate tests showed individual items also do not show significant changes with ‘easy availability of local food’ (Mpre = 4.120; Mpost = 4.130; p = 0.810) as the least significant item with minimal change occurring in the attitude of tourists towards local food. With reference to subjective norms, the analysis demonstrated significant change where Wilks’s Lambda = 0.981, F = 6.653 and p = 0.010 and only two of the four individual items showed significant changes: ‘thinks you should buy local food’ (Mpre = 3.84; Mpost = 4.02; p = 0.008) and ‘prefers you to buy local food’ (Mpre = 3.67; Mpost = 3.94; p < 0.001). Perceived Behavioural Control reflected significant changes in the pre and post-test survey where Wilks’s Lambda = 0.976, F = 8.337 and p = 0.004. In the univariate tests conducted, results showed significantly positive change in two out of the four items: ‘knowledge on where to buy it’ (Mpre = 3.630; Mpost = 3.840; p = 0.010) and ‘time availability to try local food’ (Mpre = 3.840; Mpost = 4.020; p = 0.008). Finally, personal norms showed a major change in behaviour before and after agritourism experience where Wilks’s Lambda = 0.941, F = 21.439 and p < 0.001 in which two of the three items showed significant change in the univariate tests: ‘connect with producers and locals’ (Mpre = 3.420; Mpost = 3.940; p < 0.001) and ‘support local food’ (Mpre = 4.160; Mpost = 4.340; p = 0.005).

Cronbach alpha (α = 0.784) related to ‘intended consumer behaviour towards local food’ indicate the scales to be reliable (). Rep-MANOVA represents significant change in the intended consumer behaviour among tourists towards local food before and after experiencing agritourism where Wilks’s Lambda = 0.240, F = 1088.00 and p < 0.001. Univariate tests showed that all the items under intended consumer behaviour reflected significant change that proves a positive influence of agritourism on tourists’ attitude towards purchase and consumption of local food: ‘likelihood to increase budget’ (Mpre = 2.590; Mpost = 4.180; p < 0.001); ‘buy local food’ (Mpre =2.520; Mpost = 4.180; p < 0.001); ‘shop at local markets’ (Mpre = 2.550; Mpost = 3.840; p < 0.001); ‘check labels for source’ (Mpre = 2.520; Mpost = 3.850; p < 0.001) and ‘eat at local restaurants’ (Mpre = 2.500; Mpost = 4.020; p < 0.001).

Table 5. Consumer behavior toward local food before and after experiencing agritourism (Rep-MANOVA).

Therefore, results indicate that experiencing agritourism has a positive effect on, attitudes associated with purchasing and consuming local food (hypothesis 1-A), perceived behavioral control associated with purchasing and consuming local food (hypothesis 1-C), and personal norms associated with purchasing (hypothesis 1-D) and consuming local food but has no significant effect on subjective norms associated with purchasing and consuming local food (hypothesis 1-B). Furthermore, experiencing agritourism has a positive effect on behavioral intention associated with purchasing and consuming local food (hypothesis 2).

5. Discussion

Tourists arrive at a destination from various places with varying ideas and thoughts. While some visit a destination for leisure, some visit to learn about the place’s culture, roots, and traditions. Local cuisine often poses as the centre of attraction at tourism destinations (Lu & Chi, Citation2018) because as tourists, people are inclined towards learning about local culture and tradition through consumption of local cuisine (Kim & Eves, Citation2016), because it is fresh and tasty (Lu & Chi, Citation2018) and because it supports the local economy while contributing towards environmental sustainability (Shin et al., Citation2017). As an analogy to this, findings of the study show that agritourism materializes these desires into actions via experiences as tourists ended up having strong and positive attitudes towards consuming local food. This also creates a strong foundation to encourage tourists’ future buying behaviour associated with local foods. Our study considered the impact of just one visit to agritourism establishment on tourists’ intentions as well as attitudes which shows how as little as a single stay at such a place can go a long way in promoting positively desirable behaviours of tourists toward locavorism.

Tourists are also switching to becoming responsible tourists who look for eco-friendly, sustainable practices at the destinations with a craving for ethnicity in terms of experiences and cuisine. Holistically, the statistical change observed in attitudes although noticeable was minimal and this gives the notion that tourists were already drawn towards local food even before experiencing agritourism. This stands true especially in the fact that significant changes in attitudes occurred in items that reflected the lowest scores. Therefore, results show that tourists who experience agritourism but are not strongly connected to local foods have the tendency to develop a positive attitude towards locavorism (example: ‘Positive environmental impact’ and ‘Safeguard agricultural landscape’).

Vacations are often taken with friends and/or family who are often involved in the decision-making process about the choice of destination, food, leisurely activities, and other aspects related to the trip. Therefore, these individuals play a strong role in influencing subjective norms during the process of experiencing agritourism. Tourists tend to explore local food when being advised to do so or pushed to do so. Further on, agritourism encourages interaction between tourists and locals which can stand as proof for why results showed higher perceived behavioural control post-experience. Evidence also shows that issues as such proximity and price factors associated with local food can often be a barrier between local food and tourists (Shi & Hodges, Citation2016). In retrospect, this study found that irrespective of these factors, tourists increased their ‘perceived behavioural control’ which proves that experiencing agritourism has the potential to bring down negative perceptions regarding locavorism. There was a visible increase in perceived responsibility on a personal level to get acquainted with farmers at a better level and support local food which further validates the ability of agritourism to bring together tourists and producers.

The results of our study shed light on the fact that agritourism experiences, especially direct contact with locally grown and produced food had considerable influence on tourists’ likelihood to hike their budget following which they were more likely to practice locavorism. Albeit the fact that price is one among the biggest barriers between local food and tourists, results reveal that tourists were more than willing to increase their tour budget to consume local food, and this is crucial for the sustainability of local foods. Tourists, after experiencing agritourism showed interest in consuming local food, shop at local markets, eat at local restaurants, and check labels on local products for the purpose of authenticity.

Therefore, this study paves the way to opening novel windows in the Indian agritourism sector to promote spaces and dialogues to encourage tourists to bolster sustainable local food systems (Bos & Owen, Citation2016) by means of bringing together tourists and agritourism service providers in an inclusive and sustainable environment that offers the tourists’ an authentic and ethereal experience while providing socio-economic benefits to the local economy. These results call for future research to look for more attributes involved in the agritourism experience that can motivate tourists to be more inclined towards locavorism.

From this, we suggest policy and practical implications by drawing the following strategies to promote local food through agritourism:

Market and process local food through agritourism practices that will create a direct link between consumers and farmers. Robust policies need to be put in place by governments and local authorities to encourage the monitor activities that link farmers with consumers.

Offer better access for consumers to tasty and nutritious local food while on leisure by setting up regulated market spaces and stalls for sale of local foods and creation of distribution networks through which farmers can supply raw materials to local restaurants. Agritourism farms must be encouraged to prepare more local cuisines for the tourists and offer them an experience beyond their expectations.

Promotion of LFS through agritourism helps in the creation of jobs and stable income opportunities from a sustainable combination of agriculture and tourism.

The strategic blend of agriculture, tourism and local foods carry the potential to strengthen financial capital and improve living conditions through the production, promotion, and consumption of local food systems by farmers and consumers through agritourism.

As it is evident that consumers look for taste, freshness, and related attributes in local food, it is strategic to advertise and promote local food in an appealing manner by creating an environment of learning for tourists to know more about local food, its origin, its impact on the community, etc to increase consumers’ involvement in local food consumption and develop ‘locavorism’ as a natural instinct.

6. Limitations

The major limitation of this study is that intentions, and not behaviour, have been measured. Intentions are antecedents of behaviour (Conner & Armitage, Citation1998) and are the next best alternative while measuring behaviour proves difficult. Albeit that, studies in the future should conduct follow-up surveys to assess tourists’ future local food consumption behaviour. Even though this study furnished proof showing the impact of agritourism on tourists, little thought offered in different agritourism settings such as aquaculture farms, wineries, guest cottages, trekking experiences, etc. Given that India is a country with a diverse population, future studies may incorporate a longitudinal method of data collection to deepen the scope of the study that includes the long-term effect of agritourism experience on tourists’ actual behaviour towards locavorism.

7. Conclusion

From academicians to local governments and farm owners to consumers, the practice of agritourism and locavorism has been grabbing considerable attention over the last few years. This study highlights that agritourism goes above and beyond the limits of ‘experience’ as it encourages tourists to practice locavorism throughout the tour by providing a conscious and ethereal experience to further strengthen the LFS. The empirical evidence reflects that experiencing agritourism has a significant impact on the tourists’ food purchase and consumption patterns. As a contribution towards academic thirst, our study is the first of its kind to empirically examine the pre- and post-behaviour of tourists towards local foods who experience agritourism in India. From the strategic point of view, our study output generates practical strategies to promote agritourism and associated activities among tourists. Based on the results, findings, and strategies, agritourism enterprise owners can consider agritourism as not just a tool to generate profit but also a channel to market agriproducts, especially local food. Even with an increase in interest among consumers to view local food as an option for a better lifestyle and a platform to offer support to the society, full-fledged studies on locavorism in an agritourism context has not received much attention. Future studies can offer a more comprehensive structure of the dynamics that go into a consumer’s decision-making process oriented towards consumption of local food that will portray the way transition occurs from beliefs to action.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 27–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27

- Alderighi, M., Bianchi, C., & Lorenzini, E. (2016). The impact of local food specialities on the decision to (re)visit a tourist destination: Market-expanding or business-stealing? Tourism Management, 57, 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.016

- Barbieri, C. (2013). Assessing the sustainability of agritourism in the US: A comparison between agritourism and other farm entrepreneurial ventures. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(2), 252–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.685174

- Barbieri, C., & Mshenga, P. M. (2008). The role of the firm and owner characteristics on the performance of agritourism farms. Sociologia Ruralis, 48(2), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2008.00450.x

- Barbieri, C., Stevenson, K. T., & Knollenberg, W. (2019). Broadening the utilitarian epistemology of agritourism research through children and families. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(19), 2333–2336. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1497011

- Birch, D., Memery, J., & Kanakaratne, M. D. S. (2018). The mindful consumer: Balancing egoistic and altruistic motivations to purchase local food. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40, 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.10.013

- Bisht, I. S., Mehta, P. S., Negi, K. S., Verma, S. K., Tyagi, R. K., & Garkoti, S. C. (2018). Farmers’ rights, local food systems, and sustainable household dietary diversification: A case of Uttarakhand Himalaya in north-western India. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 42(1), 77–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1363118

- Bos, E., & Owen, L. (2016). Virtual reconnection: The online spaces of alternative food networks in England. Journal of Rural Studies, 45, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.02.016

- Brune, S., Knollenberg, W., Stevenson, K. T., Barbieri, C., & Schroeder-Moreno, M. (2021). The influence of agritourism experiences on consumer behavior toward local food. Journal of Travel Research, 60(6), 1318–1332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520938869

- Cafiero, C., Palladino, M., Marcianò, C., & Romeo, G. (2020). Traditional agri-food products as a leverage to motivate tourists. Journal of Place Management and Development, 13(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-05-2019-0032

- Chen, M.-F., & Tung, P.-J. (2014). Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.09.006

- Choe, J. Y., & Kim, S. (2018). Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 71, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.11.007

- Choo, H., & Petrick, J. F. (2014). Social interactions and intentions to revisit for agritourism service encounters. Tourism Management, 40, 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.011

- Conner, M., & Armitage, C. J. (1998). Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1429–1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01685.x

- Denver, S., & Jensen, J. D. (2014). Consumer preferences for organically and locally produced apples. Food Quality and Preference, 31, 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.08.014

- Dimitrovski, D., & Crespi Vallbona, M. (2018). Urban food markets in the context of a tourist attraction – La Boqueria market in Barcelona, Spain. Tourism Geographies, 20(3), 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1399438

- Feenstra, G. (2002). Creating space for sustainable food systems: Lessons from the field. Agriculture and Human Values, 19(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016095421310

- Hasselbach, J. L., & Roosen, J. (2015). Consumer heterogeneity in the willingness to pay for local and organic food. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 21(6), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2014.885866

- Hempel, C., & Hamm, U. (2016). How important is local food to organic-minded consumers? Appetite, 96, 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.036

- Horng, J.-S., & Tsai, C.-T S. (2012). Culinary tourism strategic development: An Asia-Pacific perspective. International Journal of Tourism Research, 14(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.834

- Huddart Kennedy, E., Parkins, J. R., & Johnston, J. (2018). Food activists, consumer strategies, and the democratic imagination: Insights from eat-local movements. Journal of Consumer Culture, 18(1), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540516659125

- Jack, C., Ashfield, A., Adenuga, A. H., & Mullan, C. (2020). Farm diversification: drivers, barriers and future growth potential. EuroChoices, 20(2), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692x.12295

- Joo, Y., Seok, H., & Nam, Y. (2020). The moderating effect of social media use on sustainable rural tourism: A theory of planned behavior model. Sustainability, 12(10), 4095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104095

- Karampela, S., Andreopoulos, A., & Koutsouris, A. (2021). “Agro”, “agri”, or “rural”: The different viewpoints of tourism research combined with sustainability and sustainable development. Sustainability, 13(17), 9550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179550

- Kim, Y. G., & Eves, A. (2016). Measurement equivalence of an instrument measuring motivation to consume local food. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(5), 634–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013515922

- Kim, S.-H., & Huang, R. (2021). Understanding local food consumption from an ideological perspective: Locavorism, authenticity, pride, and willingness to visit. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102330

- Kim, S., Lee, S. K., Lee, D., Jeong, J., & Moon, J. (2019). The effect of agritourism experience on consumers’ future food purchase patterns. Tourism Management, 70, 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.08.003

- Kline, C., Barbieri, C., & LaPan, C. (2016). The influence of agritourism on niche meats loyalty and purchasing. Journal of Travel Research, 55(5), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514563336

- Lillywhite, J. M., & Simonsen, J. E. (2014). Consumer preferences for locally produced food ingredient sourcing in restaurants. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 20(3), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2013.807412

- Lu, L., & Chi, C. G.-Q. (2018). Examining diners’ decision-making of local food purchase: The role of menu stimuli and involvement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 69, 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.012

- Mair, H., & Sumner, J. (2017). Critical tourism pedagogies: Exploring the potential through food. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 21, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2017.06.001

- McGehee, N. G. (2007). An agritourism systems model: A Weberian perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost634.0

- Onel, N. (2017). Pro-environmental purchasing behavior of consumers. Social Marketing Quarterly, 23(2), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524500416672440

- Musa, S. F. P. D., & Chin, W. L. (2021). The role of farm-to-table activities in agritourism towards sustainable development. Tourism Review, 77(2), 659–671. https://doi.org/10.1108/tr-02-2021-0101

- Phillip, S., Hunter, C., & Blackstock, K. (2010). A typology for defining agritourism. Tourism Management, 31(6), 754–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.001

- Piramanayagam, S., Sud, S., & Seal, P. P. (2020). Relationship between tourists’ local food experiencescape, satisfaction and behavioural intention. Anatolia, 31(2), 316–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1747232

- Rahman, M. S., Zaman, M. H., Hassan, H., & Wei, C. C. (2018). Tourist’s preferences in selection of local food: Perception and behavior embedded model. Tourism Review, 73(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2017-0079

- Rauniyar, S., Awasthi, M. K., Kapoor, S., & Mishra, A. K. (2021). Agritourism: Structured literature review and bibliometric analysis. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(1), 52–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1753913

- Reich, B. J., Beck, J. T., & Price, J. (2018). Food as ideology: Measurement and validation of locavorism. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(4), 849–868. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy027

- Sadler, R. C., Arku, G., & Gilliland, J. A. (2015). Local food networks as catalysts for food policy change to improve health and build the economy. Local Environment, 20(9), 1103–1121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.894965

- Sakuta, R. (2020). Sustainable development goals (SDGs) and local food systems. Journal of Food System Research, 26(4), 234–238. https://doi.org/10.5874/jfsr.26.4_234

- Scheyvens, R., & Laeis, G. (2021). Linkages between tourist resorts, local food production and the sustainable development goals. Tourism Geographies, 23(4), 787–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1674369

- Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences on altruism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 221–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60358-5

- Selfa, T., & Qazi, J. (2005). Place, taste, or face-to-face? Understanding producer–consumer networks in “local” food systems in Washington State. Agriculture and Human Values, 22(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-005-3401-0

- Shah, G. (2022). The Allied Farming-Agro tourism is the tool of revenue generation for rural economic and social development analyzed with the help of a case study in the region of Maharashtra. Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, 11(1).

- Shi, R., & Hodges, A. W. (2016). Shopping at farmers’ markets: Does ease of access really matter? Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 31(5), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170515000368

- Shin, Y. H., Im, J., Jung, S. E., & Severt, K. (2017). Consumers’ willingness to patronize locally sourced restaurants: The impact of environmental concern, environmental knowledge, and ecological behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 26(6), 644–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2017.1263821

- Shin, Y. H., Im, J., Jung, S. E., & Severt, K. (2018). The theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model approach to consumer behavior regarding organic menus. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 69, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.011

- Sims, R. (2009). Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802359293

- Soliman, M. (2021). Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourism destination revisit intention. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 22(5), 524–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2019.1692755

- Sosa, M., Aulet, S., & Mundet, L. (2021). Community-based tourism through food: A proposal of sustainable tourism indicators for isolated and rural destinations in Mexico. Sustainability, 13(12), 6693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126693

- Tew, C., & Barbieri, C. (2012). The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tourism Management, 33(1), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.005

- Zhang, T., Chen, J., & Hu, B. (2019). Authenticity, quality, and loyalty: Local food and sustainable tourism experience. Sustainability, 11(12), 3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123437