Abstract

Business leaders play a key role in the implementation of actions leading to the achievement of the 17 SDGs. Likewise, higher education is emerging as the principal factor in developing a sense of moral responsibility amongst university business students, who will eventually become company managers and decision makers. The aim of this research is, thus, twofold. First, to analyse university business students’ perceptions of the role of business in achieving the SDGs; and second, to examine university business students’ perceptions of the relationship between greater commitment to achieving the SDGs and business benefits. The analysis was performed with a sample of 178 business-related university students. Amongst the potential contributions made by this study we can highlight the possibility of understanding future managers’ perceptions of the role of business in achieving the SDGs, as well as the benefits that companies could derive from greater commitment to achieving these SDGs and identifying areas for improvement in university education regarding sustainable development.

1. Introduction

From the beginning of the 20th century to the present day, there has been a period of economic growth unprecedented in history. However, these high levels of economic growth have been achieved, to a large extent, to the detriment of the environment and certain groups in society. In fact, to support the current levels of resource consumption, energy use and waste production, around 2.3 planets Earth would be required (Bell, Citation2016). The social inequalities generated worldwide, the excessive consumption of natural resources, and the use of fossil fuels and other chemical substances that are harmful to the environment, among other negative externalities, have to some extent tarnished the achievements made in economic, social and technological terms.

In this context, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was developed and approved in 2015 by the United Nations as an action plan to be developed over the next 15 years in favour of the achievement of three basic pillars: social well-being, environmental sustainability, and prosperity (United Nations, Citation2015). The measures take the form of 17 general goals and 169 specific goals, created on the basis of the millennium goals established in the year 2000 (United Nations, Citation2015). The 17th Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are grouped into five action areas: people (SDGs 1-5); planet (SDGs 6, 12, 13, 14, 15); prosperity (SDGs 7-11); peace (SDG 16); and partnerships (SDG 17). This agenda represents a guide for action for all social actors, from government to the private sector and civil society, to make joint efforts to effectively achieve the SDGs (D'Amato et al., Citation2019; Hajer et al., Citation2015).

While the Millennium Development Goals included education as a core element –and the SDGs continue doing so–, one of the new features of the 2030 Agenda is the involvement of business in the achievement of the SDGs (Szennay et al., Citation2019). In this sense, its wording seeks to encourage both corporate actions in favour of the fulfillment the SDGs and their dissemination. Both the academic and professional communities have acknowledged that the private sector plays a key role in achieving the SDGs (García et al., Citation2020; Mio et al., Citation2020; Sullivan et al., Citation2018; United Nations, Citation2015; Van Zanten & Van Tulder, Citation2018). This paper analyses the role of companies and higher education as fundamental and interconnected elements in the achievement of the SDGs.

The importance (and urgency) of achieving the UN SDGs has led an increasing number of scholars to investigate these issues, both from a business (e.g., Heras‐Saizarbitoria et al., Citation2022; Mio et al., Citation2020; Scheyvens et al., Citation2016) and from a higher education perspective (e.g., Bebbington & Unerman, Citation2018; Lozano et al., Citation2015; Owens, Citation2017; Westerman et al., Citation2021; Weybrecht, Citation2021). However, according to some authors (Witte & Dilyard, Citation2017; Heras‐Saizarbitoria et al., Citation2022), the empirical literature specifically analysing the role of the private sector in achieving the SDGs is scarce and there is a need for research to understand the strategic role of business as an agent of sustainable development (Haffar & Searcy, Citation2018; Mio et al., Citation2020).

Beyond ethical and moral considerations and the increasingly evident imperative need for action by society, one aspect to consider is the incentives for companies to commit to achieving the SDGs. Thus, authors such as Scheyvens et al. (Citation2016) have encouraged reflection on what can and should be expected from companies in relation to the SDGs. For example, previous research (e.g., Heras‐Saizarbitoria et al., Citation2022) found that the vast majority of organisations have a superficial commitment to the SDGs.

Given that business is, in essence, an economic agent and therefore has profitability as its basic objective, certain interesting questions arise: how committed are companies in achieving the SDGs? To what extent can the awareness and involvement of companies in the SDGs provide them with certain benefits? Knowing the answers to these questions is essential if we want to achieve the involvement of society as a whole and, particularly, of companies, in the achievement of the SDGs.

According to Owens (Citation2017) higher education has an important role to play in meeting the sustainable development challenges. In this same vein, higher education institutions are key agents in the education of future leaders who will contribute to the successful implementation of the SDGs (Žalėnienė & Pereira, Citation2021). Some studies have analysed university students’ knowledge and perception of the SDGs (Aleixo et al., Citation2021; Ho et al., Citation2022; Zhou et al., Citation2022), however, very few studies have analysed the perception of business students, with some exceptions (e.g., Westerman et al., Citation2021), even though they are the ones who are called to be our future business leaders.

Business academics have much to offer in achieving the SDGs, especially in the area of responsible management education (Bebbington & Unerman, Citation2018). Business academics can encourage companies to incorporate SDG thinking into their practices, and their involvement can enable a move from the normative to the pragmatic and ultimately to substantive change, which is necessary to achieve the SDGs (Christ & Burritt, Citation2019). For this reason, in this paper higher education is considered as a key factor in the development of a sense of moral responsibility among business students, who will eventually become business managers and decision makers.

Therefore, in order to deepen the understanding of the SDGs among university business students, we set a double objective: (1) to analyse university business students’ perceptions of the role of business in achieving the SDGs; and (2) to examine university business students’ perceptions of the relationship between increased commitment to achieving the SDGs and business benefits. To achieve these aims a survey has been carried out aimed at business students, considered as future managers (Alonso‐Almeida et al., Citation2015), which allowed us to know their perception about the research subject.

The paper is structured as follows. After an initial literature review (Section 2), the research methodology used in the paper, based on Partial Least Squares (PLS), is described (Section 3). The presentation of the results obtained in the analysis of future business managers’ perceptions of the SDGs and their benefits for companies follows (Section 4). The paper closes with a summary of the most relevant conclusions drawn from the study, the main limitations, and future lines of research (Section 5).

2. Literature review

Achieving sustainable development is a shared responsibility, in which all agents of society must be involved: citizens, businesses, governments and organisations of all kinds, both public and private. However, the role played by business and education –at different levels– seems to be key in the achievement of the SDGs. On the one hand, many of the SDGs are directly or indirectly linked to business activities. On the other hand, the relevance of education is determined by the firm conviction that education is one of the most powerful and proven vehicles for sustainable development (United Nations, Citation2022).

Education makes it possible to ensure, to a certain extent, that students who will occupy positions at different levels and in different areas of society will develop a social and environmental awareness in accordance with the needs of the environment, and that their actions will be consistent with these needs. In this vein, Amaral et al. (Citation2015) determine that universities play an essential role in the struggle to achieve sustainable development, mainly through their educational work, through which they can make future leaders aware of the importance of sustainability for the survival and well-being of society.

2.1. Business commitment and achieving the SDGs

Criticism of industry’s global performance in relation to its negative impact on the environment and society has increased significantly in recent decades (Andalib Ardakani & Soltanmohammadi, Citation2019; Kopnina, Citation2016). Because of this, and according to Scott and McGill (Citation2018), the involvement of business in achieving the SDGs should be seen as an essential requirement, and not just a voluntary and unilateral decision to be taken by companies. In this sense, Spangenberg (Citation2017) argues that business as usual is no option any longer, that changing the development trajectory is necessary, while Scheyvens et al. (Citation2016) claim that this requires transforming the fundamental neoliberal agenda that shapes the functioning of business and society. The only way for companies to ensure sustainable, long-term success is by the consideration of both their economic and their non-economic environment and striving to meet the expectations of a wide variety of stakeholders (Claver‐Cortés et al., Citation2020).

Business possesses a wealth of valuable and specialised resources that are necessary to achieve the SDGs, such as technology, knowledge, expertise, financial resources and labour, among others (Buhmann et al., Citation2019; Marx, Citation2019). In addition, organisations have the tools to reduce social inequalities by implementing sustainable and inclusive business models (Van Zanten & Van Tulder, Citation2018). However, a widespread transition towards new sustainable business models is crucial for the achievement of the SDGs (Scheyvens et al., Citation2016). In this respect, companies have great potential to create value, not only for their own benefit, but for a wide range of stakeholders (Chomvilailuk & Butcher, Citation2018; Porter & Kramer, Citation2011).

However, despite the broad consensus on the role of business in achieving the SDGs, the results of a recent study (Heras‐Saizarbitoria et al., Citation2022), which examines the SDG engagement characteristics of 1,370 organisations in 97 countries, found that the vast majority of organisations have a superficial commitment to the SDGs, suggesting a process of ‘SDG-washing’. But what about future managers? Does higher education train them on sustainable values and especially on the role of business in achieving the SDGs? Although more and more initiatives are emerging from universities and business schools for the development of sustainable skills, as well as fostering greater awareness of the SDGs among students (e.g., Killian et al., Citation2019), their application in higher education still seems to be limited. A recent study (Weybrecht, Citation2021) shows that most business schools are not engaging their students in the SDGs and those that do, most offer little evidence that it is integrated into the core of what students learn or that it is addressed in an interdisciplinary way. As a result, business graduates are not exposed to the SDGs in a way that connects them to ‘business as usual’. According to research conducted by Weybrecht (Citation2022), based on more than 1034 Sharing Information on Progress (SIP) reports submitted by business schools that are signatories to the United Nations backed Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), business schools have been slow to engage in the SDGs and many of the reported connections with the SDGs are weak and superficial. However, according to some authors (Lozano et al., Citation2015), this depends on strong linkages between the institution’s commitment to sustainability, the implementation, and the signature of a declaration, charter, or initiative.

All the previous arguments justify why the SDGs have become an important issue for college students, especially would-be directors. Previous research shows the impact of training on students’ perceptions of sustainability. For instance, the AMBA/Durham Business School Report published in 2010 –and based on a survey of 100 business schools with 544 students from 57 countries– showed that CSR increased its importance score from 1.95 in the 1970s to 3.49 in 2008–2009, using a 1-to-5 scale where 1 means ‘very unimportant’ and 5 ‘very important’ (Wright & Bennett, Citation2011). There is no doubt that training in SDGs will result in a greater commitment of future business leaders and, consequently, of the companies they lead to the achievement of the SDGs. Considering that most of these future managers are currently university business students, we propose the following hypotheses:

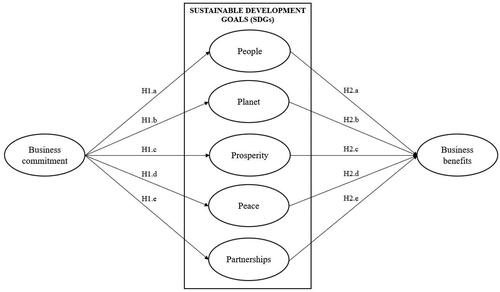

H1. University business students see business commitment to the SDGs as a key element in their achievement.

Given that the 17 SDGs are grouped around five action areas and that business commitment might differ for each of them, the general hypothesis above is broken down into the following sub-hypotheses for each of these areas: people (SDGs 1-5); planet (SDGs 6, 12, 13, 14, 15); prosperity (SDGs 7-11); peace (SDG 16); and partnerships (SDG 17).

H1.a University business students see business commitment with the SDGs as a key element in achieving the people-related SDGs.

H1.b University business students see business commitment with the SDGs as a key element in achieving the planet-related SDGs.

H1.c University business students see business commitment with the SDGs as a key element in achieving the prosperity-related SDGs.

H1.d University business students see business commitment with the SDGs as a key element in achieving the peace-related SDGs.

H1.e University business students see business commitment with the SDGs as a key element in achieving the partnerships-related SDGs.

2.2. Companies’ commitment to achieving the SDGs and business benefits

As economic actors, the basic objective of companies is to maximise their value in the market. However, society cannot afford to allow companies to try to achieve this goal at any cost. The end does not justify the means, and the need to limit the negative externalities that companies generate for the environment and society at large has been evident for decades. Consequently, the following question arises: How can the negative externalities generated by companies be reduced without limiting their development potential?

The different theoretical postulates that have emerged offer alternative perspectives on this question. Neoclassical business theory postulates that to expect organisations to carry out disinterested actions in favour of sustainable development would be to act against the very nature of business. Under this approach, for companies to act altruistically seems to be a chimera, and any effort directed in this direction would be swimming against the tide, with the consequent waste of effort and resources in favour of uncertain results. Finance theory, on the other hand, postulates that it is in the nature of business to maximise market value, which in turn enables the maximisation of shareholder value. Under this approach, the pursuit of this objective should prevent corporate behaviour aimed at short-term profit, if this seriously undermines long-term profitability. Finally, stakeholder theory broadens this perspective and establishes that, by favouring the achievement of the objectives of the company’s different stakeholders, the organisation’s own value creation is boosted. Along these lines, Porter and Kramer (Citation2011) developed the term ‘shared value creation’. This term refers to the efforts made by various socio-economic actors aimed at connecting social progress and business success, by identifying common needs of business and society, and undertaking joint actions aimed at solving the social problems that cause market failures and, consequently, limit the potential development of companies (Kramer & Pfitzer, Citation2016; Porter & Kramer, Citation2019). In this regard, different stakeholders are calling for greater incentives for companies to take action to achieve the SDGs (Sachs, Citation2012).

Many authors have claimed that the advantages obtained by firms which assume a certain degree of CSR directly correlate with business benefits (e.g., Alafi & Hasoneh, Citation2012; Cabral, Citation2012; Claver‐Cortés et al., Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2020). Taking actions in favour of sustainable development, and communicating them appropriately to key stakeholders, can help consolidate and even improve the competitive position of companies, mainly through their impact on legitimacy, corporate reputation, organisational commitment and customer satisfaction (Awan et al., Citation2017; Cantele & Zardini, Citation2018; Donoher, Citation2017; Milne & Gray, Citation2013; Nunes & Park, Citation2017). Consequently, the participation of companies in the achievement of the SDGs could positively affect their relationship with different stakeholders, their access to new business opportunities and their performance (Awan et al., Citation2017; Milne & Gray, Citation2013; Remacha, Citation2017). Based on the above, the inclusion of the SDGs in companies’ strategies and action plans should be perceived as an investment rather than an expense.

Nevertheless, there are several factors that affect the willingness and ability of companies to undertake such actions and understand the potential benefits they could derive from it, such as their size, sector of activity, stakeholder policy, profitability, or the age of their managers (Rosati & Faria, Citation2019; Pizzi et al., Citation2021; Szennay et al., Citation2019). The analysis of these factors is relevant, given the need for all companies –regardless of their characteristics– to understand the importance of contributing to the achievement of the SDGs, and the opportunities that this represents for the company itself. This would allow them to gradually modify their strategies and action plans to incorporate initiatives that contribute to the achievement of the SDGs (Pedersen, Citation2018; Saner et al., Citation2019; Scheyvens et al., Citation2016).

Changing the traditional corporate attitude towards sustainable development in favour of greater sensitivity and proactivity in this regard is one of the main challenges facing the Sustainable Development Agenda established by the United Nations (Sachs, Citation2012). In this regard, according to Rosati and Faria (Citation2019), the new generations of managers seem to be more willing to take action in favour of achieving the SDGs. As a new generation enters the workforce, it is important to understand the ethical concerns of these emerging professionals and future leaders (Franczak & Shanahan, Citation2022). However, the paradigm shift led by younger managers will be determined by their perception of the potential benefits for companies of engaging in the SDGs. Considering that most of these future managers are current university business students, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2. University business students believe that business commitment in achieving the SDGs could bring business benefits.

H2.a University business students believe that business commitment in achieving the people-related SDGs could bring them business benefits.

H2.b University business students believe that business commitment in achieving the planet-related SDGs could bring them business benefits.

H2.c University business students believe that business commitment in achieving the prosperity-related SDGs could bring them business benefits.

H2.d University business students believe that business commitment in achieving the peace-related SDGs could bring them business benefits.

H2.e University business students believe that business commitment in achieving the SDGs linked to partnerships could bring them business benefits.

summarises graphically the hypotheses of this work. The figure has been divided into two parts, a first part with only the hypotheses and a second part with the sub-hypotheses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and data collection

The target population consists of university students in business and international relations programs. These students, who will become company managers in the near future, will make corporate decisions, and will be responsible for being involved or not in the achievement of the SDGs. The sample is composed of 178 students enrolled in different degrees and educational levels at the University of Alicante (Spain). Specifically, students from the Bachelor’s Degree in Business Administration and Management –as well as from the double degrees in Law + Business, Tourism + Business and Computer Engineering + Business–, students from the Bachelor’s Degree in International Relations and the Master’s Degree in Business Administration and Management also participated (see ). The data were obtained through a survey (structured questionnaire) carried out among students between October and December 2020. However, prior to the administration of the questionnaire, a pre-test was carried out with 15 students.

Table 1. Sample description.

3.2. Variable measurement

This section describes how we measured the variables used in the empirical analysis.

3.2.1. Business commitment

This variable was regarded in the model as a first-order reflective construct. The measurement of this variable was carried out through two questions related to the perception of the impact of companies’ commitment to the achievement of the SDGs. The measurement of this construct was possible through an adaptation of the PRESOR scale (Perceived Role of Ethics and Social Responsibility), which is based on the Organizational Effectiveness Menu created by Kraft and Jauch (Citation1992). This scale, developed by Singhapakdi et al. (Citation1996), has been widely used in relation to various populations (managers, students…) (Claver‐Cortés et al., Citation2020; Giacalone et al., Citation2008; Huang & Kung, Citation2011).

3.2.2. SDGS

The proposed model features this variable as a second-order construct consisting of five first-order reflective constructs. These constructs were measured through questions directly related to each of the 17 SDGs, grouped according to the classification proposed by the United Nations: people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnerships (United Nations, Citation2015).

3.2.3. Business benefits

This variable appears as a first-order reflective construct. The measurement of this variable followed a twofold approach which combined questions related to: (a) the perception of the SDGs’ impact on firm profitability; and (b) its influence on competitive advantage generation and maintenance. These indicators have focused on measuring organisational survival, growth, and improvement of the image of customers, employees, suppliers and investors. This scale has been adapted from previous research (Brown & Laverick, Citation1994; Claver‐Cortés et al., Citation2020; Suriyankietkaew & Avery, Citation2016).

3.3. Analysis technique

Partial Least Squares (PLS) was the data analysis method used in this paper. This structural equation modelling approach is used to explain the variance in the dependent variables. Much of the increased PLS uptake may be credited to this method’s ability to manage problematic modelling issues which usually occur in social sciences (e.g., Hair et al., Citation2017). As an illustration, PLS proves to be efficient when used to estimate path models comprising many constructs, several structural path relationships, and/or many indicators per construct. We consequently considered it appropriate to use this structural equation modelling (Sosik et al., Citation2009) in our research because: (a) this study takes subjective assessments of the constructs as its starting point; and (b) the theoretical model considers many constructs. The model was assessed on the basis of the stages proposed by Hair et al. (Citation2017): measurement model evaluation; and structural model analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement model assessment

For reflective constructs in the PLS context, this first stage was evaluated by analysing not only the individual reliability of indicators but also the reliability and validity of the scale. We assessed the individual reliability of indicators through the value of their loadings (λ) and all loads exceeded the value of 0.7 as recommended in the literature. This first phase should also include scale evaluation by means of Cronbach’s α index and the composite reliability index, together with Dijktra-Hernseler’s (rho_A) indicator. The examination of extracted mean variance (AVE) also served to verify the existence of convergent validity. As shown in , both the alpha value and composite reliability, as well as rho_A, exceeded the critical value of 0.7 in every variable; and the AVE value was situated above 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 2. Construct reliability and convergent validity (AVE).

Finally, measurement model analysis requires verifying the existence of discriminant validity. The most widely accepted method in PLS is to verify the AVE value of each construct with the square of the correlation of that same construct with each of the variables. Thus, a greater AVE than the squared correlation means that each construct is more strongly related to its own measures than to other variables (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Furthermore, the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) criterion has a threshold of 0.85 (Kline, Citation2011). shows the results obtained and how they confirm discriminant validity.

Table 3. Discriminant validity.

4.2 Structural model assessment: Analysis of direct effects

The first step to assess the structural model consisted in evaluating possible collinearity problems. According to Hair et al. (Citation2017), there will be signs of collinearity when the variance inflation factor (VIF)>5. VIF values never exceeded the maximum value in this study.

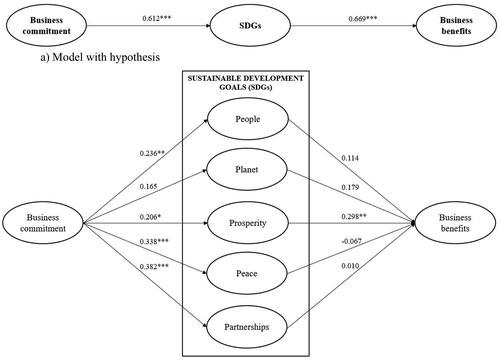

A second analysis focused on the algebraic sign, magnitude, and significance of the path coefficients which show structural model relationship estimates, that is, the hypothesised relationships between constructs. To assess the significance of these coefficients, the nonparametric bootstrapping technique of 5,000 samples was used to obtain both t statistics and confidence intervals (see ). The two main relations (H1 and H2) described in were significant because they exceeded the minimum level of a Student’s t distribution with a tail and n–1 (n = number of resamples) degrees of freedom. The same result appeared in 95% confidence intervals.

Table 4. Effects on endogenous variables.

The variable Business commitment positively influences SDGs (β = 0.612, p < .001) and the variable SDGs positively influences benefits (β = 0.669, p < .001). Therefore, hypotheses H1 and H2 are confirmed (see ). These results suggest that university students, who will hold positions of business responsibility in the future, consider business commitment to the SDGs as a key achievement target. Furthermore, university business students consider that business commitment to the SDGs could bring business benefits.

Regarding the sub-hypotheses, five out of ten direct effects described in were significant. Thus, the results show the following: On the one hand, the variable Business commitment positively influences people (β = 0.236, p < .01), planet (β = 0.165, p > .05), prosperity (β = 0.206, p < .05), peace (β = 0.338, p < .001) and partnership (β = 0.382, p < .001). Therefore, sub-hypotheses H1.a, H1.b, H1.c, H1.d and H1.e are confirmed. These results indicate that university students, who will occupy positions of business responsibility in the future, consider business commitment to the SDGs as a key achievement target in each of the areas, except for the objectives linked to the planet.

On the other hand, the variable Benefits is only positively influenced by prosperity (β = 0.298, p < .01), while the remaining relationships are not significant; people (β = 0.114, p > .05), planet (β = 0.179, p > .05), peace (β = 0.067, p > .05) and partnership (β = 0.010, p > .05). Therefore, sub-hypothesis H2.c is confirmed, whereas sub-hypotheses H2.a, H2.b, H2.d and H2.e are not confirmed (see ). These findings show that current business students believe that business commitment to achieving the SDGs could bring benefits to companies only when it comes to development goals linked to prosperity.

We assessed the value of R2 –0.371 for SDGs, 0.447 for benefits. We also assessed the value of R2 –0.055 for people, 0.028 for planet, 0.043 for prosperity, 0.113 for peace, 0.146 for partnerships and 0.236 for benefits– (see ). The structural model was also evaluated using the Stone-Geisser test (Q2) and following a blindfolding procedure (Chin, Citation1998). A Q2 greater than zero implies that the model has predictive relevance. The findings shown in confirm that the suggested model has a satisfactory predictive relevance for every dependent variable. summarises the results of the model graphically.

Among the results obtained, we can also highlight the presence of a greater number of students who claim to have a proactive or enthusiastic vision regarding the achievement of the SDGs, as opposed to those who consider themselves sceptical, who barely represent 10% of the total sample. Likewise, 88% of the students surveyed consider that the company is a key player and, therefore, should assume a certain degree of responsibility in the achievement of the SDGs.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The importance of the SDGs and the need for companies to participate in their achievement, given that this is not a short-term aim, but a permanent interest, means that it is very important to be aware of both, current managers’ opinion towards SDGs, and also future managers’ position on this target, i.e., university students. Thus, our research contributes to the literature in two significant ways: (1) understanding future managers’ perceptions of the role of business in achieving the SDGs, as well as the benefits that companies could take advantage of from their greater commitment to achieving these SDGs; and (2) identifying needs for the improvement of university education regarding sustainable development.

Based on our results, some relevant aspects of the research can be highlighted. University business students consider business commitment to the SDGs as a key element for the achievement of the SDGs. However, taking into consideration the area, they consider that business commitment can be relevant for the achievement of the goals linked to people, prosperity, peace, and partnerships, while they do not have the same perception about the goals linked to the planet. These results are in line with those found in previous work (Heras‐Saizarbitoria et al., Citation2022), which indicate that US business students are more oriented towards the prosperity and people-related SDGs than towards the planet.

In recent decades, the accelerated pace of socio-economic development has increased the quality of life of the population, especially in developed countries. However, this socio-economic development has brought with it a number of negative externalities, especially in the environmental field, linked to economic and business activity. In recent years, therefore, there has been a marked increase in society’s concern about the negative effects of human action on nature and about the actions of economic agents. At the same time, there has been an increase in media attention on this issue, which has raised social awareness.

In relation to the above, one possible interpretation of these results is that the new generations who have lived through this information boom in which the media have exposed the environmental damage caused by economic activity have internalised the idea that companies necessarily generate a negative impact on the natural environment because of their activity. Consequently, they may perceive as insufficient any effort made by companies on an individual and voluntary basis. They therefore consider the efforts made by companies on an individual and voluntary basis to be insufficient. In this sense, a tightening of regulatory levels in this area could be necessary, as well as global cooperation and coordination of different actors for the benefit of the planet. SDG 17 (Revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development) has a lot to say in this respect, as it refers to transnational collaboration to achieve the set of objectives. Thus, progress on this goal has implications not only for its own achievement, but also as an enabler of the rest. However, it seems that possible solutions do not lie in national governments, but require a global approach, where global institutions –or at least international organisations such as the European Union– are able to articulate coordinated actions within their sphere of influence.

On the other hand, university business students believe that business commitment to the SDGs could bring benefits to companies only when it comes to development goals linked to prosperity. In turn, SDGs related to people, planet, peace, and partnerships are not perceived as potential opportunity generators for companies. The results of the research suggest that there is still a high lack of awareness among students of the potential benefits for companies of operating in environments in which there are adequate conditions in each of these areas. Addressing these issues in higher education institutions would enable students to understand the importance of each of these areas for business performance. Indeed, their inclusion could not only raise students’ awareness of the potential benefits of the SDGs at the business level but could also generate new movements for the achievement of the SDGs in various areas of society. For example, there are currently several student groups at the global level, such as the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) Youth, which aims to raise awareness among students of the importance of taking action to achieve the 17 SDGs set out by the United Nations.

Our results should also make us reflect on the role of higher education in the framework of sustainable development. Strong higher education systems support achieving other goals (not only Goal 4 on education: inclusive, equitable and quality education for all), such as ending poverty, increasing health and well-being, helping people understand how to be responsible consumers, take positive action on climate, or build peaceful societies (UNESCO, Citation2016a). However, in our case, it is clear that future managers have a biased view of the potential benefits of business commitment to the SDGs for companies.

In that sense, one practical implication that emerges from our research is the urgent need to include the SDGs in the curricula of business subjects. This would make it possible to address, from an educational perspective, the consideration of business commitment to the SDGs as a key goal for their achievement, not only in areas closer to strictly economic aspects (prosperity), but also in areas related to sustainability in general (people, planet, and peace). Case methodology is a particularly intriguing option, and it may also be effective in building empathy in business students (Westerman et al., Citation2021), which could be applied to the SDGs, as well as embedding this tool within training and development processes with current leaders and employees in organizations (Cartabuke et al., Citation2019). This training in SDGs would help students in these programs acquire a vision more inclined towards the implementation of the SDGs in companies and, consequently, to face the future challenges facing today’s society.

Finally, as far as future research is concerned, as we have pointed out in the literature review, previous research shows the impact of higher education on students’ perception of corporate social responsibility in different countries. For this reason, a relevant avenue for future inquiry could be, for example, to research whether in those universities/business schools where training courses on the SDGs have been implemented their students have a different perception compared to those universities where they have not been implemented. This would provide new knowledge about how training can influence future leaders’ perceptions of the SDGs and, consequently, validate (or not) the role of universities as drivers of sustainability.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alafi, K., & Hasoneh, A. B. (2012). Corporate social responsibility associated with customer satisfaction and financial performance a case study with housing banks in Jordan. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(15), 102–115.

- Aleixo, A. M., Leal, S., & Azeiteiro, U. M. (2021). Higher education students’ perceptions of sustainable development in Portugal. Journal of Cleaner Production, 327, 129429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129429

- Alonso‐Almeida, M. D. M., Fernández de Navarrete, F. C., & Rodriguez‐Pomeda, J. (2015). Corporate social responsibility perception in business students as future managers: A multifactorial analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review, 24(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12060

- Amaral, L. P., Martins, N., & Gouveia, J. B. (2015). Quest for a sustainable university: a review. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 16(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2013-0017

- Andalib Ardakani, D., & Soltanmohammadi, A. (2019). Investigating and analysing the factors affecting the development of sustainable supply chain model in the industrial sectors. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(1), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1671

- Awan, U., Kraslawski, A., & Huiskonen, J. (2017). Understanding the relationship between stakeholder pressure and sustainability performance in manufacturing firms in Pakistan. Procedia Manufacturing, 11, 768–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2017.07.178

- Bebbington, J., & Unerman, J. (2018). Achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-05-2017-2929

- Bell, D. V. (2016). Twenty first century education: Transformative education for sustainability and responsible citizenship. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 18(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2016-0004

- Brown, D. M., & Laverick, S. (1994). Measuring corporate performance. Long Range Planning, 27(4), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(94)90059-0

- Buhmann, K., Jonsson, J., & Fisker, M. (2019). Do no harm and do more good too: Connecting the SDGs with business and human rights and political CSR theory. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 19(3), 389–403. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-01-2018-0030

- Cabral, L. (2012). Living up to expectations: Corporate reputation and sustainable competitive advantage (NYU Working Paper No. 2451/31643). SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2172651

- Cantele, S., & Zardini, A. (2018). Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability–financial performance relationship. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.016

- Cartabuke, M., Westerman, J. W., Bergman, J. Z., Whitaker, B. G., Westerman, J., & Beekun, R. I. (2019). Empathy as an antecedent of social justice attitudes and perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(3), 605–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3677-1

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Chomvilailuk, R., & Butcher, K. (2018). The impact of strategic CSR marketing communications on customer engagement. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 36(7), 764–777. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-10-2017-0248

- Christ, K. L., & Burritt, R. L. (2019). Implementation of sustainable development goals: The role for business academics. Australian Journal of Management, 44(4), 571–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219870575

- Claver‐Cortés, E., Marco‐Lajara, B., Úbeda‐García, M., García‐Lillo, F., Rienda‐García, L., Zaragoza‐Sáez, P. C., Andreu‐Guerrero, R., Manresa‐Marhuenda, E., Seva‐Larrosa, P., Ruiz‐Fernández, L., Sánchez‐García, E., & Poveda‐Pareja, E. (2020). Students’ perception of CSR and its influence on business performance. A multiple mediation analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review, 29(4), 722–736. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12286

- D'Amato, D., Korhonen, J., & Toppinen, A. (2019). Circular, green, and bio economy: How do companies in land-use intensive sectors align with sustainability concepts? Ecological Economics, 158, 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.026

- Donoher, W. J. (2017). The multinational and the legitimation of sustainable development. Transnational Corporations, 24(3), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.18356/5dbad6d9-en

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Franczak, J., & Shanahan, D. E. (2022). Shifting foci of ethical concerns: A new generation enters the corporate world. Ethics & Behavior, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2022.2124160

- García, S. I. M., Rodríguez, A. L., Aibar, G. B., & Aibar, G. C. (2020). Do institutional investors drive corporate transparency regarding business contribution to the sustainable development goals? Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(5), 2019–2036.

- Giacalone, R. A., Jurkiewicz, C. L., & Deckop, J. R. (2008). On ethics and social responsibility: The impact of materialism, postmaterialism, and hope. Human Relations, 61(4), 483–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708091019

- Haffar, M., & Searcy, C. (2018). Target‐setting for ecological resilience: Are companies setting environmental sustainability targets in line with planetary thresholds? Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(7), 1079–1092. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2053

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. SAGE Publications.

- Hajer, M., Nilsson, M., Raworth, K., Bakker, P., Berkhout, F., de Boer, Y., Rockström, J., Ludwig, K., & Kok, M. (2015). Beyond cockpit-ism: Four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 7(2), 1651–1660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7021651

- Heras‐Saizarbitoria, I., Urbieta, L., & Boiral, O. (2022). Organizations’ engagement with sustainable development goals: From cherry‐picking to SDG‐washing? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(2), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2202

- Ho, S. S. H., Lin, H. C., Hsieh, C. C., & Chen, R. J. C. (2022). Importance and performance of SDGs perception among college students in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Education Review, 23, 683–693.

- Huang, C. L., & Kung, F. H. (2011). Environmental consciousness and intellectual capital management: Evidence from Taiwan’s manufacturing industry. Management Decision, 49(9), 1405–1425. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741111173916

- Killian, S., Lannon, J., Murray, L., Avram, G., Giralt, M., & O'Riordan, S. (2019). Social media for social good: Student engagement for the SDGs. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(3), 100307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100307

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Kopnina, H. (2016). The victims of unsustainability: A challenge to sustainable development goals. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 23(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2015.1111269

- Kraft, K. L., & Jauch, L. R. (1992). The organizational effectiveness menu: A device for stakeholder assessment. MidAmerican Journal of Business, 7(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/19355181199200003

- Kramer, M. R., & Pfitzer, M. W. (2016). The ecosystem of shared value. Harvard Business Review, 94(10), 80–89.

- Lozano, R., Ceulemans, K., Alonso-Almeida, M., Huisingh, D., Lozano, F. J., Waas, T., Lambrechts, W., Lukman, R., & Hugé, J. (2015). A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.048

- Marx, A. (2019). Public-private partnerships for sustainable development: Exploring their design and its impact on effectiveness. Sustainability, 11(4), 1087–1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041087

- Milne, M. J., & Gray, R. (2013). W (h) ither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1543-8

- Mio, C., Panfilo, S., & Blundo, B. (2020). Sustainable development goals and the strategic role of business: A systematic literature review. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(8), 3220–3245. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2568

- Nunes, M. F., & Park, C. L. (2017). Self-claimed sustainability: Building social and environmental reputations with words. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 11, 46–57.

- Owens, T. L. (2017). Higher education in the sustainable development goals framework. European Journal of Education, 52(4), 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12237

- Pedersen, C. S. (2018). The UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) are a great gift to business!. Procedia CIRP, 69, 21–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.01.003

- Pizzi, S., Rosati, F., & Venturelli, A. (2021). The determinants of business contribution to the 2030 Agenda: Introducing the SDG Reporting Score. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(1), 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2628

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 11, 1–30.

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2019). Creating shared value. In G. Lenssen & C. N. Smith (Eds.), Managing sustainable business (pp. 323–346). Springer.

- Remacha, M. (2017). Empresa y objetivos de desarrollo sostenible. Cuadernos de la Cátedra CaixaBank de Responsabilidad Social Corporativa, 34, 1–28.

- Rosati, F., & Faria, L. G. D. (2019). Business contribution to the sustainable development agenda: Organizational factors related to early adoption of SDG reporting. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(3), 588–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1705

- Sachs, J. D. (2012). From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. The Lancet, 379(9832), 2206–2211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60685-0

- Saner, R., Yiu, L., & Kingombe, C. (2019). The 2030 Agenda compared with six related international agreements: valuable resources for SDG implementation. Sustainability Science, 14(6), 1685–1716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00655-2

- Scheyvens, R., Banks, G., & Hughes, E. (2016). The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual. Sustainable Development, 24(6), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1623

- Scott, L., & McGill, A. (2018). From promise to reality: Does business really care about the SDGs?. SDG Reporting Challenge 2018. PriceWaterhouseCoopers. https://n9.cl/2jsb3

- Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., Rallapalli, K. C., & Kraft, K. L. (1996). The perceived role of ethics and social responsibility: A scale development. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(11), 1131–1140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00412812

- Sosik, J., Kahai, S., & Piovoso, M. (2009). Silver bullet or voodoo statistics? A Primer for using the partial least squares data analytic technique in group and organization research. Group & Organization Management, 34(1), 5–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601108329198

- Spangenberg, J. H. (2017). Hot air or comprehensive progress? A critical assessment of the SDGs. Sustainable Development, 25(4), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1657

- Sullivan, K., Thomas, S., & Rosano, M. (2018). Using industrial ecology and strategic management concepts to pursue the Sustainable Development Goals. Journal of Cleaner Production, 174, 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.201

- Suriyankietkaew, S., & Avery, G. (2016). Sustainable leadership practices driving financial performance: Empirical evidence from Thai SMEs. Sustainability, 8(4), 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8040327

- Szennay, Á., Szigeti, C., Kovács, N., & Szabó, D. R. (2019). Through the blurry looking glass—SDGs in the GRI reports. Resources, 8(2), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8020101

- UNESCO .(2016). Education for people and planet: Creating sustainable futures for all (Global Education Monitoring Report 2016). UNESCO.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. General Assembly of the United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf

- United Nations. (2022). https://jointsdgfund.org/sustainable-development-goals/goal-4-quality-education. Consulted on 20 October 2022.

- Van Zanten, J. A., & Van Tulder, R. (2018). Multinational enterprises and the sustainable development goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. Journal of International Business Policy, 1(3-4), 208–233. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-0008-x

- Westerman, J. W., Nafees, L., & Westerman, J. (2021). Cultivating support for the sustainable development goals, green strategy and human resource management practices in future business leaders: The role of individual differences and academic training. Sustainability, 13(12), 6569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126569

- Weybrecht, G. (2021). How management education is engaging students in the sustainable development goals. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 22(6), 1302–1315. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-10-2020-0419

- Weybrecht, G. (2022). Business schools are embracing the SDGs–But is it enough?–How business schools are reporting on their engagement in the SDGs. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(1), 100589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100589

- Witte, C., & Dilyard, J. (2017). Guest editors’ introduction to the special issue: The contribution of multinational enterprises to the Sustainable Development Goals. Transnational Corporations, 24(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.18356/799ae8b0-en

- Wright, N. S., & Bennett, H. (2011). Business ethics, CSR, sustainability and the MBA. Journal of Management & Organization, 17(5), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1833367200001309

- Žalėnienė, I., & Pereira, P. (2021). Higher education for sustainability: A global perspective. Geography and Sustainability, 2(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2021.05.001

- Zhang, Q., Cao, M., Zhang, F., Liu, J., & Li, X. (2020). Effects of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction and organizational attractiveness: A signaling perspective. Business Ethics: A European Review, 29(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12243

- Zhou, R., Abedin, N. F. Z., & Sheela, P. (2022). Sustainable development goals knowledge and sustainability behaviour: A study of british and Malaysian tertiary students. Asian Journal of University Education, 18(2), 430–440.