Abstract

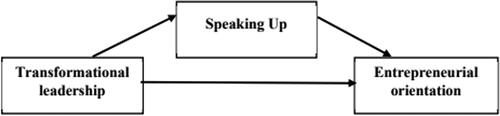

The creation of an entrepreneurship university involves the promotion and institutionalisation of the orientation towards entrepreneurship of all parts of the university, especially the scientific departments, which is affected by several factors. Therefore, our research investigates the effect of transformational leadership style of academic departments’ heads on entrepreneurial orientation of these departments mediated by speaking up behaviour of faculty members. Data were collected from 217 faculty members of 50 academic departments in universities of Qom city and provided support for the model. The findings demonstrated a positive and significant relationship between transformational leadership and speaking up, between speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation, and between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation. Furthermore, speaking up mediates the relation between transformation leadership style and entrepreneurial orientation. These findings highlight the catalyst role of speaking up, leveraging transformational leadership as antecedents of entrepreneurial orientation in academic departments. These findings are valuable inputs for managers in university, and policy makers in a higher education sector. Eventually, the theoretical and practical inferences of this research are discussed.

1. Introduction

With emerging innovation economics, universities in most countries, including Iran’s universities, have been required to create direct engagement with industry to maximise commercialisation and capitalisation of knowledge through patenting and licencing technology innovation, direct cooperation with enterprises through R&D collaboration, and setting up spin-offs (Cai & Liu, Citation2014). In fact, the university has faced with new challenges, including industry’s need to a creative, innovative, and entrepreneurial workforce and highly skilled and employable graduates, the threats of competition for students and funding sources from industry and government to strengthen the performance of research and create technology, and also the requirement to be responsive to global trends of higher education massification versus world-class aspirations (Tierney & Lanford, Citation2016). These challenges have influenced most universities of world to become more entrepreneurially oriented and to adapt to market demands, to commercialise their research and make profit through research, patents, and establishing spin-off companies (Kirby, Citation2006). Moreover, the prominence of knowledge as a valuable resource for economic advancements of nations demands that educational institutions such as universities to become ‘entrepreneurial’ via their culture, governance, and administration (Rip, Citation2002), i.e., ‘entrepreneurial universities’ (Ozdemir Güngör et al., Citation2019). Entrepreneurship universities can underpin entrepreneurship businesses (Khorshid & Mehdiabadi, Citation2021) and develop entrepreneurship societies.

Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) as an entrepreneurial strategy makes processes that key leaders use to establish their organisational goals, support their vision, and create competitive advantage (Sabahi & Parast, Citation2020). The literature on entrepreneurial orientation clearly establishes that large organisations can benefit from doing activities in an entrepreneurial manner. Despite expanding research on commercialisation activities and entrepreneurship, and also limited studies about entrepreneurial orientation in university setting (e.g., Latif et al., Citation2016; Sisilia & Sabiq, Citation2018; Ball, Citation2019; Yang, Citation2021; Tatarski et al., Citation2020; Abidi et al., Citation2022; Nikitina et al., Citation2022; Elshaer & Sobaih, Citation2022), little is known about the entrepreneurial orientation in university, especially its academic departments, and what factors might develop and promote entrepreneurial orientation in them. For instance, some researchers measure individual entrepreneurial orientation among students (Nikitina et al., Citation2022; Yang, Citation2021), employees (Tatarski et al., Citation2020), and Graduates (Elshaer & Sobaih, Citation2022). Other researchers study entrepreneurial orientation and its relationship with faculty characteristics (Abidi et al., Citation2022), commercialisation research products (Latif et al., Citation2016), school business performance (Ball, Citation2019), teacher performance (Hayat & Riaz , Citation2011) self-esteem towards entrepreneurial intention of students (Sisilia & Sabiq, Citation2018), entrepreneurial intentions of students (Jegede et al., Citation2021) and entrepreneurship education (Amran & Parinduri, Citation2021). Therefore, it is indispensableto study factors influencing on entrepreneurial orientation in academic departments.

In entrepreneurship and leadership literature, it has indicated that leadership styles influence on entrepreneurial orientation (e.g., Ekiyor & Dapper, Citation2019; Obeidat et al., Citation2018). Prior studies explain leadership as basic for identifying and successful implementing of strategies and long-term goals of the organisation. In fact, leaders can have a powerful effect on personnel’s behaviour (Ekiyor & Dapper, Citation2019). Furthermore, today’s ever-changing higher education environment has created a need for new leadership styles that foster positive changes, innovation and improvements. Researchers argued that higher education sector requires transformational leadership as a prerequisite for meeting the ever evolving external and internal environment (Nurtjahjani et al., Citation2019). Previous studies have shown that transformational leadership has a favourable impact on organisational climate, subordinates, students, and faculty members in universities (Cortés, Citation2012). Similarly, some researchers indicated that transformational leadership support and enhance organisation’s capacity and tendency for entrepreneurial orientation (e.g., Ekiyor & Dapper, Citation2019; Obeidat et al., Citation2018; Rose & Mamaboli, Citation2019) and encourages individuals to alter their behaviours and principles in support of entrepreneurial activities (Muchran & Muchran, Citation2017). So many studies conducted did find some relationships between entrepreneurial orientation and transformational leadership in other organisational setting (e.g., Harsanto & Roelfsema, Citation2015), but no studies conducted in higher education to find some relationship between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation. Therefore, the study of linkage between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation in higher education sector, universities and academicians is of high value that unquestionably requires attention.

Voice behaviour of employees is generally believed to play a critical role in maintaining continuous growth and sustainable development of organisations because organisations rely more and more on innovation and entrepreneurship (Liu et al., Citation2010). The transformational aspects of voice behaviour also involve risk because of uncertainty associated with the suggested changes (Liu & Liu, Citation2017). The success of the ideas and suggestions (even a highly constructive idea) depend on overcoming multiple challenges such as resistance from others inside the organisation, status-quo, and uncertain forces outside the control of an individual or organisation (Aryee et al., Citation2017). As well, literature has stressed the importance of leaders in motivating employees to voice their opinions, thoughts and ideas (e.g., Detert & Burris, Citation2007; Liu et al., Citation2010). Transformational leadership stimulates employees to take part in decision-making process and take hold of improvisations to fulfil creative thoughts and rectify problems that prevent organisations from entrepreneurial activities. As respects, notwithstanding the definitive role of employee voice behaviour in entrepreneurship activities for all kinds of organisations, the concept stays under-studied in scientific departments. Therefore, with marking this gap, we argue that employee voice is a potential means through which transformational leadership can develop and promote entrepreneurial orientation as strategic posture, and consequently encourage entrepreneurship activities in organisation.

Although these streams of research have illuminated our understanding of these complex issues, there remains a lacuna surrounding the potential mediating roles of speaking up on the potential association between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation. Despite the importance of the three phenomena for the universities generally, the subject of their interrelationship has so far attracted no interest in academic study, prompting us to address this topic in our research. Against this background, thus, the objective of this study is to examine the effect of transformational leadership on entrepreneurial orientation mediated by speaking up in the higher education context. Exploring the relationship between the speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation in university setting is particularly important given that it can provide insights into how universities can encourage their faculty as speakers up for engaging their academics departments in entrepreneurial activities.

This study offers a number of important contributions. First, building on social exchange theory (Yang & Blau, Citation1964). We demonstrate how transformation leadership can affect the speaking up and the subsequent impact on entrepreneurial orientation. Interestingly, the address a current gap in current literature were very few studies have attempted to examine the impact of the transformation leadership on the speaking up of faculty and entrepreneurial orientation of academic departments. Moreover, we also demonstrate how the speaking up behaviour of faculty and as a result, entrepreneurial orientation in Iran’s universities could be enhanced by investing in processes that strengthen the transformation leadership style among academic departments’ heads. Second, a review of the literature on entrepreneurial orientation in university setting indicates that limited studies on the entrepreneurial orientation in university (Taatila & Down, Citation2012; Tatarski et al., Citation2020; Todorovic et al., Citation2011). Thus, this study extends our empirical knowledge regarding the entrepreneurial orientation in academic departments. Furthermore, a comprehensive understanding of the effect of the speaking up behaviour as a type of voice behaviour on the entrepreneurial orientation in academic departments would be valuable. It is expected to have both theoretical and managerial implications for universities. Therefore, voice practices of academic departments’ heads could be used to develop and enhance the faculty members’ speaking up behaviour, when its impact on the entrepreneurial orientation is known.

2. Contextual setting

The current trend of the economy shows the place and importance of entrepreneurship in the preservation and survival of organisations. A factor that, according to many thinkers, is the most appropriate option to reduce the gap between developed and less developed countries or leading and following organisations. The realisation of organisational entrepreneurship has made it necessary to pay more attention to the style of organisational management and leadership. The reason for the existence and basic responsibility of managers is to play leadership roles in organisations in order to achieve more effective and better productivity from material, financial and especially human resources. On the one hand, transformational leaders provide the necessary basis for strengthening the performance of employees through supportive-guidance communication and establishing a relationship between employees’ abilities and future-oriented goals; On the other hand, one of the important roles of today’s organisations is their entrepreneurial role; And one of the main indicators of entrepreneurship is entrepreneurship in the organisation, which undoubtedly plays a significant role in the success, excellence and improvement of the performance of organisations. Here, the role of managers and leaders of the organisation is very important, because managers Organisations can foster and encourage entrepreneurial activities in the organisation by emphasising innovation and creativity in existing trends. Therefore, universities, as the main centres of science production with the aim of entrepreneurship in the society, and through their faculty members, can be the cornerstone of the basic change and transformation in the society. This importance can be explained and implemented through explaining the relationship of transformational leaders.

In a rapidly changing world, organizations need to continuous and constant recognize new opportunities over existing eligibilities if they are to survive. Moreover, the current trend of the economy shows the importance of entrepreneurship in the survival, prosperity and excellence of organizations. Entrepreneurship unveils itself in practices and functions leading to coordination of the organization’s resources and behaviors of its members, whose significant and main stimulus is to seek gains. This directly effects not only the current activities of the organization, but all the probability of its subsequent growth and progression (Gajda, Citation2015). As stated by Baron (Citation2012), entrepreneurship requires the use of people creativity, knowledge, and vigor to create new, useful, and better things than what heretofore exists and which begets some form of social and economic values. On the foundation of these few viewpoints relating to the definition of entrepreneurship, it can be argued that entrepreneurship is related with methods and processes targeted at getting achievement. In addition, entrepreneurship means the transition from pre-existing status quo to something new and unprecedented in its perspective, and its outcomes and effects should be requested in the creative use of opportunities through the innovative use of financial and material resources and effectiveness leadership of people (Gajda, Citation2015). One kind of entrepreneurship is organizational entrepreneurship or internal entrepreneurship. Sharma and Chrisman (Citation1999) describe organizational entrepreneurship as the process by which a person or a group of individuals, linked with a present organization, engender a new organization or stimulate renewal or innovation within that organization. The dynamic environment of business and fast technological improvements has enhanced the importance of organizational entrepreneurship with respect to obtaining a competitive advantage and reaching organizational sustainability.

There are several factors that play an important role in the development of attitude, intention, and entrepreneurial activities in an organization. Management and organization scholars and thinkers believe that the leadership style of managers and human resources of an organization are the most important factors for developing and institutionalizing entrepreneurial activities in all levels and components of an organization. To build on entrepreneurial behaviors in the organization, managers of organizations need to centralize on bringing up and boosting their competencies and capabilities through the style of transformational leadership as leaders are responsible in attaining strategic organization’s goals and for generating the best outcomes with effective resource exploitation (Hashim et al, Citation2018; Obeidat et al., Citation2018). The transformational leadership style is appropriate for organizations that accept an entrepreneurial orientation strategy because it energetically cultivates innovation and information transfer through the leader’s charismatic behavior (Dzomonda et al., Citation2017). Managers with high levels of transformational leadership can be affiliated with extending high levels of innovation at work, more remarkable endeavor, and the creating and expanding of given organizational behaviors among employees (Razavi & Ab Aziz, Citation2017; Leite, & Rua, Citation2022), including creative, innovative, and entrepreneurial behaviors. Therefore, universities, as the main centers of creating a rare quality and talent workforce, carrying out research, promoting technologies, supporting business and industry, and engaging in the community and solving its problems, with the aim of promoting entrepreneurship in the society, and as a result, creating entrepreneurial communities, and through their faculty members, can be the cornerstone of the basic change and transformation in the society. This importance can be studies and performs through explaining the relationship of transformational leadership of academic departments' heads and speaking up behavior of faculty members with entrepreneurial orientation of academic departments.

3. Theoretical background and hypothesis development

3.1. Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO)

The construct of EO was coined by Covin and Slevin (Citation1990), in line with Schumpeter’s (Citation1912) conception of what entrepreneurial individuals (Khedhaouria et al., Citation2015), groups and organisations do (Keh et al., Citation2007): creating, diffusing and exploiting production knowledge (Mthanti & Ojah, Citation2017). The term ‘EO’ describes the entrepreneurial capabilities (Covin et al., Citation2006), including an organisation ability to innovate, take risks, and pro-actively pursue market opportunities (Rauch et al., Citation2009) that differentiates an organisation over its rivals and explains variation in firm performance and superior growth (Al-Swidi & Mahmood, Citation2012). As well, ‘EO’ as an organisation strategic posture (Todorovic et al., Citation2011; Anderson et al., Citation2015; Mthanti & Ojah, Citation2017) is defined as processes, practices, decision-making and strategy making styles, activities and processes (Ketchen & Short, Citation2012; Al-Swidi & Mahmood, Citation2012; Al-Awlaqi et al., Citation2021) of an organisation that engages in entrepreneurial activities (Lumpkin & Dess, Citation2001) and acts entrepreneurially (Okangi, Citation2019).

With emerging innovation economics, universities have been required to create direct engagement with industry to maximise commercialisation and capitalisation of knowledge through patenting and licencing technology innovation, direct cooperation with enterprises through R&D collaboration, and setting up spin-offs (Cai & Liu, Citation2014) to fulfil their ‘third mission’. The third mission of universities is creating changes in and around university from knowledge production to knowledge and technology transfer and implement by industry, from mono-disciplinary university model to trans-disciplinary entrepreneurial university, from entrepreneurship education targeted to university members in order to create entrepreneurial attitudes in society generally (Mets, Citation2009). It is then important for universities to position themselves as hubs of entrepreneurship by nurturing an entrepreneurial environment and providing substantial contributions to the economy and society with providing educational support, concept development support, and business development support (Al-Awlaqi et al., Citation2021). Universities that simultaneously fulfil three different activities of teaching, research, and entrepreneurship while providing an adequate atmosphere in which students, academics, faculties, staff, and others can explore and exploit ideas, is known as entrepreneurial university (Ozdemir Güngör et al., Citation2019; Fernández-Nogueira et al., Citation2018). This type of university shapes institutional and cultural aspects, processes, and architecture that support the entire university community in pursuing third mission activities (Nelles & Vorley, Citation2011). An entrepreneurship university can provide leadership for creating entrepreneurial thinking, actions, institutions, and entrepreneurship capital (Audretsch & Keilbach, Citation2008), in line with Audretsch’s (Citation2014) call to move from the concept of entrepreneurial university to a university for entrepreneurial community (Pugh et al., Citation2018). Such transformative change can bring direct benefits to the university by increasing the levels of academic entrepreneurial activities within their institution and can also have regional spill-over effects on the economic, technological and societal exploitation of knowledge (Urbano & Guerrero, Citation2013; Fernández-Nogueira et al., Citation2018).

Although the terms of university entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial university have been defined by many researchers, there is no clear definition of the term entrepreneurial orientation in the university. In addition, the research conducted on entrepreneurial orientation in universities, with the exception of two cases (Todorovic et al., Citation2011; Tatarski et al., Citation2020), have used entrepreneurial orientation’s measurement applied in other organisational settings (e.g., Taatila & Down, Citation2012; Latif et al., Citation2016; Abidi et al., Citation2022) that often measure innovation, risk-taking, pro-Activeness, and autonomy as components of entrepreneurial orientation. Todorovic et al. (Citation2011) conceptualised operationally entrepreneurial orientation in university in terms of the following four follow dimensions: (A) Research mobilisation, (B) Unconventionality, (C) Industry collaboration, and (D) Perception of university policies. Then they developed a measurement in term of these four dimensions, and test its validity and reliability. As well, Tatarski et al. (Citation2020) used this measurement for measure entrepreneurial orientation of university employees. In this research, with inspiring from the definitions of entrepreneurial orientation, it is defined as an academic departments’ strategic position to establish environment in line of university’s third mission (i.e., entrepreneurship and to be engage in community) that promote entrepreneurship spirit, thinking, and attitude in its members, leading to a significant rise in entrepreneurship and innovativeness activity coming from academia, and commercialising knowledge.

3.2. Transformational Leadership (TL)

Basing on the leadership theory of Bass (Citation1985), Men (Citation2014) defines transformational leadership as a leadership style inspiring his subordinates to adopt the organisational vision as if they are their own and focus their energy on the achievement of common goals. leadership theory is based on listening, openness, feedback, participation, communication, and relationship (Men, Citation2014). Transformational leaders allow subordinates to participate in decision-making. They also attempt to understand followers’ needs, stimulate followers to achieve goals and are flexible in working towards the desired outcomes (Boukamcha, Citation2019). Furthermore, leadership theory is considered as a model of integrity, where it establishes clear goals and objectives, generates high expectations, motivates the team, offers support and recognition to the people, stirs people’s emotions, makes followers look beyond their self-interest (De Juan Jordan et al., Citation2018).

Transformational leadership is conceptualised as a multi-dimension construct (De Juan Jordan et al., Citation2018). In their empirical study, Rafferty and Griffin (Citation2004) proposed five more focussed sub-dimensions of TL including vision, inspirational communication, intellectual stimulation, supportive leadership, and personal recognition. Vision refers to the expression of an idealised picture of the future based around organisational values. Inspirational communication is defined as the expression of positive and encouraging messages about the organisation, and statements that build motivation and confidence. Intellectual stimulation refers to enhancing employees’ interest in, and awareness of problems, and increasing their ability to think about problems in new ways. Supportive leadership is defined as displaying concern for followers’ welfare, taking account of their individual needs, and creating a friendly and psychologically supportive work environment. Personal recognition refers to the provision of contingent rewards for achievement of specified goals.

3.3. Transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation

Entrepreneurship and leadership are related (Felix et al., Citation2019). They have many similarities, like concepts of vision, influence, innovation, and planning (Yan et al., Citation2014). Bass and Bass (Citation2008) suggested that leadership beseem to have a fundamental impact on some organisational consequences, such as innovation (Jia et al., Citation2018), innovation processes (Norbom & Lopez, Citation2016), entrepreneurship (Leitch & Volery, Citation2017), community entrepreneurs (Lyons et al., Citation2012), opportunity entrepreneurship (Felix et al., Citation2019), innovative entrepreneurship (Van Hemmen et al., Citation2015; Franco & Haase, Citation2017), collaborative entrepreneurship (Franco & Haase, Citation2017) and corporate entrepreneurship (Chen & Nadkarni, Citation2017). Leaders are also an important source for acquiring resources, changing strategies based on knowledge of the changing environment (Covin et al., Citation2019) and motivating employees to do entrepreneurial activities through incentives and creating an entrepreneurial culture (Demircioglu & Chowdhury, Citation2020).

Prior research has shown that TL style (Chen et al., Citation2014; Stephan & Pathak, Citation2016) through inspiration, vision and deeper meaning has a very important role in engendering the suitable climate for entrepreneurship and innovation in an organisation (Van Hemmen et al., Citation2015; Franco & Haase, Citation2017; Demircioglu & Chowdhury, Citation2020), and has a significant effect on innovations (Kraft & Bausch, Citation2016), organisational innovation, innovative organisational climate and creative behaviour (Jung et al., Citation2003), entrepreneurial behaviour (Stephan & Pathak, Citation2016), product innovation and corporate entrepreneurship (Chen et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the charismatic characteristic of transformational leadership creates an environment that inbreeds entrepreneurship motivated by innovation, creativity and the perception of entrepreneurial opportunities (Bass & Bass, Citation2008). While, transformational leaders explore new ways of working, seek opportunities in the face of risk, prefer effective answers and are less likely to support the status quo (Zaech & Baldegger, Citation2017), they encourage followers to adopt exploratory thinking processes, stimulate them to raise and improve their capabilities (Felix et al., Citation2019) and develop their innovative capabilities (Verma & Verma, Citation2019) for organisational success. Transformational leaders eventually prepare the organisation for changes, help it to cope with such changes (Yan et al., Citation2014), and develop corporate entrepreneurship (Verma & Verma, Citation2019). Previous research indicate that transformational leaders may help in building corporate entrepreneurship (Dvir et al., Citation2002) through providing organisational team members with greater motivation and sense of responsibility, empowering team members by giving higher autonomy to them (De Juan Jordan et al., Citation2018) and enhancing their risk-taking capabilities (Verma & Verma, Citation2019). Transformational leaders would impress entrepreneurial orientation and employee’s behaviours through persuading in-profound intellectual processing, questioning norms, concepts, practices and processes (Muchiri & McMurray, Citation2015). They would encourage employees through inspirational stimulation to take risks, be creative and innovative, which are decisive components in entrepreneurial orientation. Therefore, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 1: Transformation al leadership positively influences entrepreneurial orientation.

3.4. The mediating speaking up behaviour

Voice behaviour is defined as suggestion of creative and innovative ideas, views, and thoughts through proactively challenging the status quo conditions that threaten or criticise management or its processes and procedures, making change or doing modification in standard procedures in spite of disagreeing others, and afterwards persuading people in organisation to accept and implement them (e.g., Chan, Citation2014; Ilkhanizadeh & Karatepe, Citation2017; Afsar et al.,Citation2019). Furthermore, voice behaviour is viewed as one type of contextual, discretionary, extra-role behaviour (Liu et al., Chan, Citation2014), and in essence, promotive (i.e., supportive and constructive) (Maynes & Podsakoff, Citation2014), that contributes to success indirectly by maintaining or improving the organisational, social, or psychological environment that enhances the effective functioning of an organisation (Wharton, Citation2016). Voice behaviour as a contextual, discretionary, extra-role behaviour potentially challenges the status quo and seeks to make constructive changes (Chan, Citation2014) intended to improve rather than to merely criticise (Maynes & Podsakoff, Citation2014). Meantime, voice behaviour as a promotive behaviour provides support for organisational procedures, advocates organisational policies that other employees criticise, suggests improvements to standard operating procedures, and suggests ideas for new or more effective work methods (Maynes & Podsakoff, Citation2014). In terms of voice’s target (Milliken et al., Citation2003), there are two kinds of voice behaviour in organisation: the voice is oriented towards colleagues and peers (known as speaking out), and the voice is oriented towards the supervisor (called as speaking up). This research study centres on voice behaviour towards the supervisor. Liu et al. (Citation2010) describes speaking up as an upward influence process. Garon (Citation2012) defines speaking up as sharing one’s ideas with someone with the perceived power to devote organisational attention or resources to the issue raised, and as improvement-oriented communication that is directed towards a specific target holding power inside the organisation.

Various studies are widely explored the positive influence of some leadership styles, relationships and behaviours (e.g., Morrison, Citation2011; Tangirala & Ramanujam, Citation2012; Liu et al., Citation2010; Chan, Citation2014) on employees’ voice behaviour, and has emphasised on the importance role of leaders in motivating employees to voice behaviours, especially speaking up (e.g., Detert & Burris, Citation2007; Liu et al., Citation2010). In among different leadership styles, much attention has been given to transformational leadership style and its linkage to employee’s voice behaviour (e.g., Wharton, Citation2016; Carioti, Citation2011; Kwak, Citation2012; Liu et al., Citation2010; Morrison, Citation2011; Cheng et al., Citation2013; Kwon et al., Citation2016; Afsar et al., Citation2019). Carioti (Citation2011) found subordinates with transformational leadership who spoke up in the workplace when (a) they felt safe committing their ideas, (b) leaders of the organisation related individually to each subordinate by promoting and encouraging individual growth, and (c) leaders motivated employees to compete at their highest levels. In their work on the influence of transformational leadership on employees’ voice behaviour, Liu et al. (Citation2010) concluded that transformational leadership promotes upward voice behaviour because of the employee’s personal identification with the leader as a role model. They drew on social exchange theory (SET) as the basis for the argument that relationships with others influence voice behaviour (Liu et al., Citation2010) and social penetration theory. SET proposes that if the two entities such as the organisation and employees attach to exchange certain rules (i.e., reciprocity), they create relationships based on trusting, loyal, and mutual commitments over time (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005; Saks, Citation2006). When employees build social exchange relationships with the organisation (i.e., employer or supervisor), which ‘…tend to involve the exchange of socioemotional benefits’ and are associated with ‘…close personal attachments and open-ended obligations’ (Cropanzano et al., Citation2003), they are likely to show affective and behavioural outcomes (Ilkhanizadeh & Karatepe, Citation2017) such as extra-role behaviours, including promotive (i.e., supportive and constructive) voice behaviours for enhancing organisation performance. TL characteristics and behaviours empower followers to achieve the leader’s vision and affect and cultivate followers’ voice intention and behaviour (e.g., Parker & Wu, Citation2014; Carioti, Citation2011; Kwak, Citation2012). Transformational leaders can stimulate their employees to speak up their ideas and thoughts in order to achieve their goals in the organisation through demonstrating important behaviours of idealised influence or charisma where the leader acts a role model concerned with the common interest and improvement, intellectual stimulation where the leader encourages individuals to solve problem, inspirational motivation where the leader listens to employee ideas and acts on them, individual consideration where the leader encourages individual engagement (Carioti, Citation2011). In short, based on SET theory, the current study suggests that FMs with favourable perceptions of transformational leader behaviours and their relationships with academic department’s head have higher career satisfaction, and show voice behaviour by proposing ways to make improvements in individual and organisational functioning of their academic department. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2a: Transformational leadership positively influences faculty speaking up behaviour.

As Schumpeter (Citation1942) and Audretsch et al. (Citation2005) have theoretically clarified how entrepreneurial organisations foster growth and development by creating, diffusing and exploiting knowledge (Mthanti & Ojah, Citation2018), the basis of the strength of an established organisation is the capacity of generating novel, creative and brilliant ideas of their personnel, performing entrepreneurial activities, making constant innovations, transforming these innovations into concrete product (Doğan, Citation2016). The best ideas for an entrepreneurial activity are likely to come from activities and people who work in the organisation. Carter et al. (Citation1994), and Nucci (Citation1999) wrote that business survival and success is related to human resources. Human resources are recognised as an invaluable source of ideas, expertise and knowledge for improving management decision-making and the work environment (Farndale et al., Citation2011). They offer innovative ideas, suggest ideas for organisational policies and procedures, alert management to problems inside and outside the workplace, and identify innovative solutions that result in competitive advantages for the organisation (Detert & Burris, Citation2007; Wilkinson & Fay, Citation2011). As Senge (Citation1990) suggested, ‘Leaders need help from their subordinates to improve organisational functioning, it is not possible any longer to figure it out from the top’. Employees speak up with ideas and suggestions that improve policies and procedures, alert managers to problems inside and outside the workplace, identify innovative solutions that result in competitive advantages for the organisation, and contribute to management decision-making (Detert & Burris, Citation2007; Wilkinson & Fay, Citation2011). Creative ideas can address organisational procedures and come from anyone, especially line workers, in the workplace (Wharton, Citation2016). Therefore, people who have high satisfaction of their organisation and are loyal to the organisation, they use their brains for the success and prosperity of the organisation and help the organisation or work unit perform more effectively or to make a positive difference for the collective (Ashford et al., Citation2009; Morrison, Citation2011) through voicing their ideas and suggestions, recommendations, and issues. Loyal employees are willing to tolerate a higher level of disagreement with organisational activities and actively contribute to changing the situation by speaking up. Loyal employees will try all alternatives before they painfully decide to withdraw from the organisation. That is, as long as loyal people believe in the possibility of improvement, they will stay (Ruiner et al., Citation2020).

We contend that speaking up of faculty as a way of changing in strategic orientation of academic departments towards entrepreneurship. In fact, entrepreneurial orientation of academic departments requires highly engaged all of their faculty, which can be achieved by encouraging them to engage in speaking up behaviour related to entrepreneurship activities, cooperation with industry and engagement in community. Therefore, speaking up behaviour of faculty is crucially important for effective organisational functioning of academic departments in an ever-changing and dynamic business environment as it tends to challenge the status quo. Indeed, voice is a mechanism through which organisation’s members can help their organisation adjust to the current business environment and remain innovative (Rubbab & Naqvi, Citation2020). As such, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 2b: Faculty speaking up behaviour positively influences entrepreneurial orientation of academic departments.

Taken together, given that transformational leadership behaviours predict speaking up behaviours of employees (e.g., Wharton, Citation2016; Carioti, Citation2011; Kwak, Citation2012; Liu et al., Citation2010; Ilkhanizadeh & Karatepe, Citation2017; Morrison, Citation2011; Cheng et al., Citation2013; Kwon et al., Citation2016; Afsar et al., Citation2019) and consequences, including promote and create entrepreneurial climate (e.g., Van Hemmen et al., Citation2015; Franco & Haase, Citation2017; Demircioglu & Chowdhury, Citation2020), entrepreneurship (Felix et al., Citation2019; Verma & Verma, Citation2019), entrepreneurial behaviour (Stephan & Pathak, Citation2016), corporate entrepreneurship (Chen et al., Citation2014), organisational innovation and innovation-supporting organisational climate (Jung et al.,Citation2003), and also voice behaviours predicts these consequences, then in this study, we propose that transformational leaders can develop entrepreneurial orientation and encourage entrepreneurship activities in academic departments of university by creating an environment in order to encourage voice (speaking up) behaviour among faculty. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2c. Faculty’s speaking up mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation in academic departments.

4. Method

4.1. Procedure and participants

The present study was conducted with a descriptive-correlational (structural equation modelling) design. Participants comprised 217 faculties of 50 academic departments of Basic, Engineering, Health, and Humanities and Social sciences from universities of Qom city (University of Qom, Payam Noor University of Qom, Qom Islamic Azad University, Qom Medical university of sciences). The sampling method appropriate for this study was a random multistage sampling. Considering the non-return rate of the questionnaires, 300 questionnaires are distributed among the faculty. By following up, 225 questionnaires are collected. By screening the questionnaires and removing incomplete and confusing questionnaires, 217 questionnaires became the basis for data analysis. The response rate was equivalent to 72.3%. A total sample of the faculty of: Basic Sciences (16.6%), Engineering Sciences (25.3%), Humanities and Social Sciences (34.6%), and Health Sciences (23.6%). 61.8% of respondents were male and 38.2% were female. In terms of academic rank, 36.9% of respondents were instructors, 57.6% of them were an Assistant Professor, 3.2% of them were an Associate Professor, and 2.3% of them were a Full Professor.

Since all of the scales in this survey were originally in English, the questionnaire was translated and back-translated by author and a bilingual expert (fluent in English-Persian) separately to ensure the reliability and validity of the scales (Brislin, Citation1970) to maintain conceptual equivalence between the original instruments (in English) and the Persian versions. Researchers agree that back-translation of an instrument is essential for its validation and use in a cross-cultural study (John et al., Citation2006). As well, following Biemer and Lyberg (Citation2003) recommendations, and testing the content validity, we invited 19 faculties in organisational behaviour management and entrepreneurship fields in Tehran and Qom universities. They assess all items of three constructs of transformational leadership, speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation of university in term of their relevance, simplicity, and clarity. After collecting data, the content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI: I-CVI and S-CVI) are calculated.

By combining these measurements, a questionnaire consisting of 47 items was prepared. All items in this questionnaire are quantified using the Likert five-choice scale, from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). Internal consistency (Cronbach Alpha) and combined reliability, and the convergence, and divergence validity of all measurement instruments of variables of this research are measured. Moreover, academic department’s size is selected as control variable. Entrepreneurship literature suggests that the size has a direct impact on entrepreneurial activity in a firm (Kearney et al., Citation2008).

Hypotheses are tested through three sets of analyses. First, a series of CFA models is conducted using LISREL 8.3 to establish the measurement properties of the items assessed in this study. Next, we examined the construct, discriminant and convergence validity, and reliability of measurement instruments of transformational leadership, speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation. Finally, we estimated a structural model linking the transformational leadership to the speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation.

4.2. Measurements

We use validated measures from priori research to test the conceptual model and hypotheses. Bass (Citation1985) conceptualised the construct of transformational leadership and developed a theoretical model. This model consists of five behavioural components following as: vision, inspirational communication, intellectual stimulation, supportive leadership, personal recognition. Rafferty and Griffin (Citation2004) re-examine this theoretical model to identify five sub-dimensions of transformational leadership that will demonstrate discriminant validity with each other. As well, Rafferty and Griffin (Citation2004) adapted leadership items from measures produced by House (Citation1998) and Podsakoff et al. (Citation1990). This measurement is consisting of 15 items for measuring five behavioural components of transformational leadership: vision, inspirational communication, intellectual stimulation, supportive leadership, personal recognition. There were three items for each component. Confirmatory factor analyses are performed by Rafferty and Griffin (Citation2004) provided support for the hypothesised factor structure of the measures selected to assess these sub-dimensions, and also provided support for the discriminant validity of the sub-dimensions with each other. In current study, faculty are asked to respond to the transformational leadership items keeping in mind the leader or manager of their work department.

We adopted Liu et al. (Citation2010) nine-item voice scale to capture the challenge behaviour towards the supervisors or managers. This measurement is consisting of 9 items. In past studies, the Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was 0.94 (Liu et al., Citation2010). In this study, a self-reported instrument is used for measuring the speaking upbehavior of faculty members. Therefore, the term “this person” in the original items replaced with ‘I” to specify the target of behaviors.

Entrepreneurial orientation is measured with Todorovic et al. (Citation2011) ENTRE-U items. This measurement is an instrument that measures the entrepreneurial orientation of universities. As stated by Todorovic et al. (Citation2011), this scale can successfully predict the number of licences, patents, and spin-offs. This scale consists of 23 items and measures university entrepreneurial orientation in terms of four factors of research mobilisation, unconventionality, industry collaboration and university policies. For this study, the items of this scale rewrite for measuring in entrepreneurial orientation in the academic department level.

5. Data analysis and results

5.1. Measurement model

The content validity index (CVI) is calculated for all individual items (I-CVIFootnote1) and the overall scale (S-CVIFootnote2). The results showed that values of I-CVI for each item range from 0.84 to 1. With five or fewer judges, the value of I-CVI should be 1, and with six or more judges, one should not be less than 0.78 (Shrotryia & Dhanda, Citation2019). The value of S-CVI is for transformation leadership, speaking up, and entrepreneurial orientation are0.88, 0.94, and 0.94, respectively. A minimum S-CVI should be 0.8 for reflecting content validity. The value of S-CVI represents the average values in proportion to the content validity of a measurement instrument in all the items with the minimum CVR of 0.79. In sum, an CVI of 0.78 or higher is considered excellent (Rodrigues et al., Citation2017). This supports the conclusion that individual items are important and relevant to measuring of the constructs of transformation leadership, speaking up, and entrepreneurial orientation in university. As well, the value of CVR for each item of constructs of transformation leadership, speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation in university ranges from 0.68 to 1. It is noted that the threshold value of CVR is dependent to the number of experts participated in assessing a measure. The acceptable threshold value of CVR in the spectrum is 0.29 for 40 experts and 0.99 for 5–7 experts.

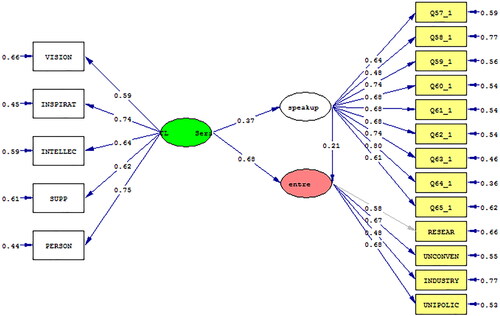

Confirmatory factor analysis is used to test the factorial validity and reliability of constructs of transformation leadership, speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation. reports the factorial loadings for the individual items. The factorial loadings should also be greater than 0.5 and statistically significant (t-value > 1.96 in α = 0.05). The values of factorial loadings of three items of transformation leadership measurement and six items of entrepreneurial orientation measurement are small and less than 0.5. presents the overall fit of the three measurement models is acceptable. Therefore, these items are removed from transformation and entrepreneurial orientation’s sub-constructs lead in a substantial in CR, Cronbach’s alpha (α) and AVE.

Table 1. CFA reliability analysis (removing items with factorial loading less than 0.5).

Table 2. The overall fit of the three measurement models of research variables and their fit indices.

On , statistics of reliability, including composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha (α), and the average variance extracted (AVE) of the transformation leadership, entrepreneurial orientation, and speaking up are presented. The value of recommended threshold for both CR and α is 0.7, and 0.50 for AVE (Hair et al., Citation2006). All measures of the internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of the constructs lie well above the cut-off point of 0.7 (Nunnally, Citation1978), ranging between 0.71 and 0.88. All constructs have CR greater than 0.7, which confirms the reliability of the measurement instruments. The average variance extracted (AVE) of all constructs is greater than 0.5, which means that the measurement models demonstrate convergent validity. As well, we examined the discriminant validity of the constructs using Fornell and Larcker, (Citation1981) criteria. The Fornell–Larcker criterion requires the square root of the AVE to be larger than the correlations between constructs. In , the diagonal element, namely, the square root of AVE, is larger than the correlations between constructs. Therefore, all the measures satisfy the discriminant validity of the constructs. The assessment of the construct reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and indicator reliability produces satisfactory results, showing that the constructs can be used to test the conceptual model.

Table 3. Correlation matrix, mean, SD, and validity and reliability indexes of research constructs measurement instruments.

5.2. Common Method Variance (CMV)

Next, as the source of all the independent, mediator and dependent variables existed in one instrument, the possibility of bias could not be excluded (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). First, a measurement model is estimated in which indicators were allowed to load on their theoretical construct and a common factor. The fit of this model was very good (χ2 = 1017.10 (df = 630) = 1.614, CFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.95 and RMSEA = 0.053). Next, the method of marker variables is used, which is theoretically unrelated to the principal constructs in the research (Lindell & Whitney, Citation2001). The academic rank of faculty is used as the marker variable. The results indicate that the academic rank of faculty was not significant for the measures used in this study. Low correlations between the academic rank of faculty and the three principal constructs in the study (where the highest was r = 0.18 with α = 0.01).

5.3. Structural model assessing

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the key variables are presented in the descriptive statistical analysis (see ). Transformation leadership, speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation were significantly and positively correlated.

Individual responses are aggregated to the unit level since the criterion variable is a department level construct. Prior to conducting the structural equation modelling, the intra-class correlations are calculated (Bliese, Citation2000) for transformation leadership (ICCFootnote31 = 0.36, ICC2 = 0.38), speaking up (ICC1 = 0.42, ICC2 = 0.43) and entrepreneurial orientation (ICC1 = 0.18, ICC2 = 0.20). Furthermore, we computed within-group agreement index (rwg) for transformation leadership (rwg = 0.90), speaking up (rwg =0.91) and EO (rwg =0.93). According literature, rwg ≥ .70 represents acceptable agreement (Zohar, Citation2000). Transformation leadership, speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation were significantly and positively correlated. As well, the test of partial correlation indicates that with considering and without considering control variable of academic departments’ size, correlation coefficients between entrepreneurial orientation and transformational leadership, between entrepreneurial orientation and speaking up, and between transformational leadership and speaking up remained constant.

Structural model was computed to test hypotheses. The mediation relationship was tested using the methodology proposed by Mathieu and Taylor (Citation2006). First, a model containing a direct path from transformational leadership to entrepreneurial orientation, without the presence of the speaking up is tested. This model fit the data well (). Transformational leadership was positively related to entrepreneurial orientation (β = 0.76, t = 6.52; p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. Then, the effect of transformational leadership on speaking up (hypothesis 2a), the effect of speaking up on entrepreneurial orientation (hypothesis 2 b), and the mediating role of speaking up in the transformational leadership - entrepreneurial orientation relationship (Hypothesis 2c) are examined. The full mediation model with the partial mediation model is compared. Fit statistics (see ) demonstrated that the partial mediation model was the better model (p < 0.001). The values of χ2/df = 1.50 and RMSEA = 0.048 met the cut-off and was smaller for the partial mediation model than for the full mediation model. The NFI, NNFI, CFI, IFI, and RFI values for the partial mediation model were above the threshold of 0.90 and was greater than that for the full mediation model.

Table 4. Fit indexes for structural models.

5.4. Testing hypotheses

The SEM results ( and ) demonstrated that transformational leadership significantly and directly predicted speaking up (β = 0.37, t = 4.51, p < 0.0001)) and entrepreneurial orientation (β = 0.68, t = 6.40, p < 0.0001) supporting hypotheses 1 and 2a. Speaking up positively predicted entrepreneurial orientation (β = 0.21, t = 2.80, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2b. The SEM results verified that this mediation is a partial rather than a full mediation, with the coefficient for the direct path from transformational leadership to entrepreneurial orientation still being statistically significant (β = 0.76, t = 6.52, p < 0.001). As well, the results of Sobel’s test confirmed that speaking up significantly mediates the relationship between transformational leadership on entrepreneurial orientation (β = 0.08, t = 2.38, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 2c was supported. represents the results of hypotheses testing, and presents the overall structural model with standardised path coefficients.

Figure 2. Structural equation modelling results: The standardised values.

Source: computed in this study.

Table 5. Direct hypotheses and mediating hypothesis test.

6. Conclusions and discussion

The realisation of the third mission of the university, namely the promotion and development of university entrepreneurship and as a result the development of an entrepreneurial university, requires that the university adopt a strategic orientation towards entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) as a strategy entails enacting processes that key leaders can use to establish organisational goals, support their vision, and create competitive advantage (Sabahi & Parast, Citation2020). In this line, the present study examined the effect of transformational leadership style on entrepreneurial orientation, mediated by speaking up of faculty in academic departments. Findings of this study create an important understanding and insight about promote and develop entrepreneurial orientation in science departments through accentuating the mediating role of faculties’ speaking up.

The first of our research finding indicated that academic department heads’ transformational leadership style has a direct, positive influence on speaking up of faculties. This finding is generally supported by previous studies about the relationship between leadership and entrepreneurship (Felix et al., Citation2019; Yan et al.,Citation2014; Leitch & Volery, Citation2017; Van Hemmen et al., Citation2015; Franco & Haase, Citation2017; Chen & Nadkarni, Citation2017; Leite & Rua, Citation2022). Similarly, this result is confirmed by Chen et al., Citation2014; Stephan & Pathak, Citation2016; Van Hemmen et al., Citation2015; Franco & Haase, Citation2017; and Demircioglu & Chowdhury, Citation2020. Entrepreneurial orientation opens new ways for universities to search for issues and opportunities in their activity environment. Therefore, the successful implementation of an entrepreneurial orientation needs an effective leadership style, such as a transformational leadership style from the senior management team, and other levels of university management. Previous studies indicated that organisations with a potent entrepreneurial orientation direct their strategic and feasible decisions to capture new opportunities. Bass and Bass (Citation2008) state transformational leadership creates an environment and climate that links entrepreneurship with the motivation of innovation, creativity, recognising and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities. Transformational leaders encourage followers to explore new ways for solving problems, to enhance their creativeness and innovation capabilities and competencies Prosperity and excellence of the organisation. As well, Panagopoulos and Avlonitis (Citation2010) stated that leadership practices align and complement mechanisms for accomplishing successful strategies. The linkage entrepreneurial orientation with leadership, principally transformational leadership is irrefutable. The transformational leaders identify, backing and enlarge followers’ talent, skills, and creativity and innovation abilities. They perform this by accepting inimitable and innovative processes, fulfilling insolent measurements, and an attitude of competitive offensiveness towards the market (Ekiyor & Dapper, Citation2019). Transformational leadership assists put into practice new strategies, begetting an environment where followers feel confidence and respectability for the leader and are stimulated to work more than envisaged (Leite & Rua, Citation2022). By the same token, Obeidat et al. (Citation2018) presumed entrepreneurial orientation’s prosperity is linked with transformational leadership. This type of leadership cheers people to speculate creatively, breeds new ideas about existing functions, activities, processes or products, and qualifies them to transform. As a consequence, their entrepreneurial attitudes and the organisation’s behaviours are amplified. As the size of academic departments does not have any statistical and meaningful effect on their entrepreneurial orientation, the findings suggest that regardless of size, the main determinant of entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurship activities in academy departments of universities is leadership behaviour. Overall, the findings of this study imply that typically and in comparison, with organisations (non-research and non-educational organisations in public and private section), size of academy departments do not have significant effects on entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurship activities as budgets are stable, resources are secured, and academy departments do not compete with each other. Therefore, leadership, particularly transformational leadership behaviours, is important for entrepreneurship in universities and academy departments.

The second of our research finding demonstrated that transformational leadership positively predicted voice behaviour of speaking up. This finding is consistent with prior research displaying that transformational leadership contributes to employees’ positive outcomes such as organisational citizenship behaviours (e.g., Sumarmi et al., Citation2022) and employees voice behaviour (e.g., Liu et al., Citation2010; Wharton, Citation2016; Kwon et al., Citation2016; Chen et al., Citation2018; Afsar et al., Citation2019). For instance, Liu et al. (Citation2010) reported that transformational leadership facilitates speaking up. Chen et al. (Citation2018) confirmed positive relationship between transformational leadership positively predicted promotive voice behaviour. Employees’ voice behaviours are behaviours reverberated employees’ discretionary contribution through declaring creative and innovative ideas and suggestions on how to correct and better organisational and work practices and processes (Liang et al., Citation2017). As well, transformational leaders signal and encourage voice behaviour by stimulating followers to behold old problems from new standpoints, to look at things differently, imputing them more delimiters in interplaying and challenging the current situation, so they potentially augment the deal of ideas produced by employees. Transformational leaders signalise and cheer employees’ voice behaviour by being a capable and active listener and in person interacting with employees for doing effectively works and enhancing organisational achievements. the transformational leaders excite and enable employees to work for achieving organisation vision and goals, and strategic orientations (e.g., entrepreneurial orientation), and can augment employees’ stimulation to exhibit themselves to attain these goals (Liu et al., Citation2010).

The third of our research result showed that voice behaviour of speak up directly influence entrepreneurial orientation. Finally, the mediating effect of voice behaviour of speaking up between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation was confirmed. These findings are indirectly supported by Shih and Setiadi Wijaya (Citation2017), Rasheed et al. (2017), Soomro et al. (Citation2021), Azevedo et al. (Citation2021), Getachew Kassa and Teklu Tsigu (2022). For instance, Shih and Setiadi Wijaya (Citation2017) found a positive effect of voice behaviour on creative work involvement. They noted that creative work involvement and voice behaviour are both related with beneficial ideas; but both have different focuses. Creative work involvement underscores more on employees’ actual practices in regard to creative activities, whereas voice behaviour refers to the comment of ideas and opinions. Rasheed et al. (Citation2021) reported that employee voice is a significant predictor for both organisational innovation, and product and process innovation in SMEs. Soomro et al. (Citation2021) revealed a positive and significant linkage between employee voice and creativity. Getachew Kassa and Teklu Tsigu (2022) argued that corporate entrepreneurship services as the capability to product innovation as a competence. Entrepreneurial orientation requires being unconventional, finding new ways to solve problems, exploring and exploiting new opportunities. At the same time, entrepreneurial orientation involves innovation and creativity, and also the development and implementation of innovation strategies requiring the engagement and ultimately the capitalisation of the ideas of the organisation’s key human resources—its employees, remarked through their voice behaviour (Azevedo et al., Citation2021). The more impressive people perceive the voice practices of managers to be, the more likely they are to encourage and further their notions, thoughts, and viewpoints or worries about functions, activities and processes in workplace (Shih & Setiadi Wijaya, Citation2017). In line with this argument, Botha and Steyn (Citation2022) found that supportive and constructive voice behaviour positively correlated with innovative work behaviour.

As a result, the leadership, as a fundamental contextual factor, affect employees inclined to declare their viewpoints and notions. Last studies have demonstrated that perceived transformational leadership behaviour, as a change-oriented behaviour, has a significant impact on both employee’s voice and supporting behaviours to improve organisational functioning and achieve strategic posture of an organisation, i.e., entrepreneurial orientation (Todorovic et al., Citation2011; Anderson et al., Citation2015; Mthanti & Ojah, Citation2017). Furthermore, transformational leaders empower and motivate people to display higher learning, self-initiatives, knowledge sharing and ideas development, which leads to innovation (Molodchik et al., Citation2021; Rasheed et al., Citation2021) and entrepreneurial orientation (Felix et al., Citation2019; Yan et al., Citation2014; Leitch & Volery, Citation2017; Van Hemmen et al., Citation2015; Franco & Haase, Citation2017; Chen & Nadkarni, Citation2017; Leite & Rua, Citation2022). Entrepreneurial orientation can be seen as an entrepreneurial strategy, making processes that key leaders use to establish their organisational goals, support their vision, and create competitive advantage (Sabahi & Parast, Citation2020).

7. Theoretical implications

This study has several theoretical implications for research on entrepreneurial orientation of academic apartments in university setting: First, this study provides a deeper exploration and analysis of the effects of transformational leadership on speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation. Although the effect of transformational leadership on speaking up and entrepreneurial orientation are usually considered in other organisational setting, but our research findings put forward several academic contributions.

First, our findings make a significant contribution to the leadership, voice behaviours and entrepreneurship in higher education literatures. Previous studies suggest that humanistic leadership styles, including transformational leadership is beneficial for promoting and encouraging speaking up, and as a result, entrepreneurial orientation. As well, we have found a supplementary advantage of speaking up: it is a trigger to ribbon the transformational leadership of the organisation into its idea-making and entrepreneurial climate, the final outcome being the promotion and institution of entrepreneurial orientation. This relationship emphasises on the role, commitment and comprehensive support of managers in the development of entrepreneurial thinking, spirit, attitude, orientation, and activities of in all components and members of the organisation through the development of entrepreneurial vision. In fact, transformational leaders excite followers with organisation vision and incite them with cognition, self-rule and backing to think for the greater concerns of the organisation and do over prospects (Sameer & Özbilgin, Citation2014). Transformational leaders allow the organisation and its personnel in critical and out-of-box thinking and participate and help in making positive changes and fulfilling entrepreneurial activities in organisation. Transformational leadership has been known as an affective organisational mechanism for cultivating employee extra-role behaviours (Rasheed et al., Citation2021) and organisation entrepreneurship (Felix et al., Citation2019; Yan et al., Citation2014; Leitch & Volery, Citation2017; Van Hemmen et al., Citation2015; Franco & Haase, Citation2017; Chen & Nadkarni, Citation2017; Leite & Rua, Citation2022).

Second, in examining the transformational leadership style and entrepreneurship orientation linkage, we have looked at the mediating role played by speaking up. Our findings propose that transformational leadership promotes and encourages entrepreneurial orientation both directly and indirectly through the mediation of voice behaviour of speaking up. In this indirect path, we have found that transformational leadership raises voice behaviour of speaking up, which, in turn, enhances further entrepreneurial orientation. Hence, voice behaviour of speaking up of employees works as a significant partial mediator between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation.

Third, moreover still, our findings shed light to the transformational leadership- entrepreneurial orientation research stream looking at the intervening steps between these two variables. We have found that transformational leadership is a determinant of entrepreneurial orientation relationship, Rauch et al. (Citation2009) highlighted that there is an essential amount of variability in such linkage. We propose that this variability might be because of some extent to the interceding role of voice behaviour of speaking up, especially in the case of entrepreneurial orientation. Our findings put forward a likely explanation on why some scientific departments into universities might have a poor entrepreneurial orientation even though their university emphasises on entrepreneurship activities: the voice behaviour of speaking up link may be missing. This is a contribution to the leadership and voice behaviours literatures.

Finally, our findings represent an important input for the social exchange theory and social penetration theory. An adequate link between the organisation’s transformation leadership style and voice behaviour of speaking up is able to boost organization orientation and strategic posture on entrepreneurship, and thereby organisation’s performance. As a result, the connection between transformation leadership style and voice behaviour is a significant factor in clarifying why some organisations have better performance (Arif & Akram, Citation2018). The social exchange theory put forward a theoretical base for comprehending the interaction relationship between leaders and members in an organisation. According to this theory, a satisfactory social relation is reciprocally advantageous (Emerson, Emerson, Emerson, Citation1976). In a social interaction, individuals need to give back the acquired value and gains to keep the exchange relationships (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). In organizations, leader–member exchange is remarked as the kernel of the social exchange connections. Buil et al. (Citation2019) distinguished that transformational leadership can cultivate a high-quality exchange relationship with people by directly declaring consideration, confidence, and support. Out of reciprocity, people will augment their regard and constancy to the organisation and thus applicant to fulfil positive behaviours out of their obligations. In our study, social exchange theory describes how transformational leadership may contribute to speaking up behaviour and, in tern of promoting entrepreneurship as a strategic orientation of scientific departments.

8. Implications for practitioners

The results of our study produce some useful commendations. This study underscore speaking up as a main channel through which transformational leadership effects on developing and promoting entrepreneurial as a strategic position. If the academic departments’ heads fail to defining and performing voice procedures and practices, and as a result, creating voice climate, the positive influence of transformational leadership on entrepreneurial orientation would be partially lost. Practitioners fulfilling and supporting transformational leadership style require a conception of how to accomplish this task. Managers of university, specially, scientific departments’ heads actively asking for ideas, opinions and comments from their personnel are more likely to receive them by providing individuals numerous opportunities for fulfilling their viewpoints and ideas. Managers must also ensure organisational members that they candidly want to hear about problems or issues as employees have experience of them.

9. Limitations and recommendations

The limitations of this study must be borne in mind: The data of this research come from faculty of Iran’s universities. The habits, customs, beliefs, values, and national culture of Iran leave their impression, which also has implications for the generalisability of our findings. An interesting way for future studies would be to explore the potential impact that the different cultural and national contexts have on challenging voice behaviours and entrepreneurial orientation into universities in other countries, expressing and testing the effects of cultural differences in the relationships between the entrepreneurial orientation and its antecedents. Second, cross-sectional design does not allow deductions on the relationship causality among variables. Then, future research bringing forth on longitudinal plans is encouraged. The longitudinal research can assess, for instance, if exogenous events such as a change in organisational policies, regulations, and also organisation’s finances drive organisational members to change in their behaviours and actions towards organisation, and as a result, to engage in voice behaviours. Third, future research could have expanded the proposed conceptual model of our research, that can include other constructs such as voice climate (Frazier & Bowler, Citation2015) as a moderator of relationship between transformational leadership and employees voice behaviours, and psychological safety (Dörner,Citation2021) as a moderator of relationship between employee’s voice behaviours and entrepreneurial orientation. Forth, our study respondents are faculties. Nevertheless, future research could centralise on exploring voice and entrepreneurial intents of students as one of the main players in the beneficiaries of university. Such experiment will help to achieve entrepreneurial orientation in university.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Notes

1 item-level content validity index

2 scale-level content validity index based on the average method

3 INTRACLASS CORRELATION COEFFICIENT

References

- Abidi, O., Nimer, K., Bani‑Mustafa, A., & Toglaw, S. (2022). Relationship between faculty characteristics and their entrepreneurial orientation in higher education institutions in Kuwait. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00206-7

- Afsar, B., Shahjehan, S., Shah, S. I., & Wajid, A. (2019). The mediating role of transformational leadership in the relationship between cultural intelligence and employee voice behavior: A case of hotel employees. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 69(1), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.01.001

- Al-Awlaqi, M. A., Aamer, A. M., & Habtoor, N. (2021). The effect of entrepreneurship training onentrepreneurial orientation: Evidence from a regression discontinuity design on micro-sizedbusinesses. International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100267.

- Al-Swidi, A. K., & Mahmood, R. (2012). Total quality management, entrepreneurial orientation and organizational performance: The role of organizational culture. African Journal of BusinessManagement, 6(13), 4717–4727.

- Amran, E., & Parinduri, A. Z. (2021). Antecedent and Consequent Analysis of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Students of Faculty of Economics and Business Trisakti University [Paper presentation]. LePALISSHE, Malang, Indonesia. https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.3-8-2021.2315130

- Anderson, B. S., Kreiser, P. M., Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Eshima, Y. (2015). Re-conceptualizing entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 36(10), 1579–1596. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2298

- Arif, S., & Akram, A. (2018). Transformational leadership and organizational performance: The mediating role of organizational innovation. SEISENSE Journal of Management, 1(3), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.33215/sjom.v1i3.28

- Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Mondejar, R., & Chu, C. W. (2017). Core self-evaluations and employee voice behavior: Test of a dual-motivational pathway. Journal of Management, 43(3), 946–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314546192

- Ashford, S. J., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Christianson, M. K. (2009). Speaking up and speaking out: Theleadership dynamics of voice in organizations. In J. Greenberg & M. Edwards (Eds.), Voice and silence in organizations (pp. 175–202). Emerald.

- Audretsch, D. B., Keilbach, M., & Lehmann, E. (2005). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship and technological diffusion. In Libecap, G.D. (Ed.), University entrepreneurship and technology transfer (advances in the study of entrepreneurship, innovation and economic growth (Vol. 16, 69–91). Emerald.

- Audretsch, D., & Keilbach, M. (2008). Resolving the knowledge paradox: Knowledge-spillover entrepreneurship and economic growth. Research Policy, 37(10), 1697–1705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.08.008

- Audretsch, D. (2014). From the entrepreneurial university to the university for the entrepreneurial society. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9288-1

- Azevedo, M. C. d., Schlosser, F., & McPhee, D. (2021). Building organizational Innovation through HRM, employee voice and engagement. Personnel Review, 50(2), 751–769.

- Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

- Bass, B. M., & Bass, R. (2008). The bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerialapplications. The Free Press.

- Ball, M. J. (2019). The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and school business performance through the lens of rural K-12 public chief school business officials education [Doctoral thesis]. Paper 424

- Baron, R. A. (2012). Entrepreneurship. An evidence-based guide. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Biemer, P. P., & Lyberg, L. E. (2003). The measurement process and its implications for questionnaire design. Introduction to survey quality. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471458740.ch4

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein and S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

- Botha, L., & Steyn, R. (2022). Employee voice and innovative work behavior: Empirical evidence from South Africa. Cogent Psychology, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2022.2080323

- Boukamcha, F. (2019). The effect of transformational leadership on corporate entrepreneurship in Tunisian SMEs. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(3), 286–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2018-0262

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

- Buil, I., Martínez, E., & Matute, J. (2019). Transformational leadership and employee performance: The role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77(7), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.014

- Cai, Y., & Liu, C. (2014). The roles of universities in fostering knowledge-intensive clusters in Chinese regional innovation systems. Science and Public Policy, 42(1), 1–15.

- Carioti, F. V. (2011). A windfall of new ideas: A correlational study of transformational leadership and employee voice, Capella University [thesis]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 3473155.

- Carter, N. M., Stearns, T. M., Reynolds, P. D., & Miller, B. A. (1994). New venture strategies: Theory development with an empirical base. Strategic Management Journal, 15(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150103

- Chan, S. C. H. (2014). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice: Does information sharing matter? Human Relations, 67(6), 667–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713503022

- Chen, Y., Guiyao, T., Jin, J., Xie, Q., & Li, J. (2014). CEOs’ transformational leadership and product innovation performance: The roles of corporate entrepreneurship and technology orientation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12188

- Chen, J., & Nadkarni, S. (2017). It’s about time! CEOs’ temporal dispositions, temporal leadership, and corporate entrepreneurship. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(1), 31–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216663504