?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study used the global database of events, language, and tone of international public opinion big data to measure organizational stigmatization against China. It then used an econometric model to investigate the impact of organizational stigmatization on the operational risk and performance of overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises. The results show that: (1) organizational stigmatization increases overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and reduces their operational performance, which is more evident in overseas subsidiaries of state-owned enterprises; (2) the host country’s political stability weakens the organizational stigmatization’s positive impact on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. The geographical distance between the home and host countries strengthens organizational stigmatization’s positive impact on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk; (3) the host country’s political stability and the geographical distance between the home and host countries have no moderating effect on organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance; and (4) organizational stigmatization by the host country reduces overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance via the channel of operational risk. This study innovates the measurement method of organizational stigmatization and lays the foundation for investigating the microeconomic impact of organizational stigmatization from the perspective of overseas subsidiaries.

1. Introduction

With improvements in China’s comprehensive national strength and enterprises’ continuous development and growth, ‘going global’ has become the norm. Outward foreign investment by enterprises is conducive to the layout of a global development strategy, the mobilization and allocation of factors of production and resources, the implementation of international competition and cooperation, and the improvement of profitability and international competitiveness. According to the Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI), China’s 28,000 domestic investments established 45,000 foreign direct investments in 189 countries (regions) worldwide as of 2020. Chinese enterprises invested in more than 80% of the world’s countries (regions). The influence of Chinese foreign direct investment on global foreign direct investment is increasing.

However, Chinese enterprises are often stigmatized and suppressed in ‘going global’. In April 2018, the United States claimed that Zhong Xing Telecom Equipment (ZTE) had violated the export ban imposed by the United States on Iran and blocked ZTE. In May 2019, the United States listed Huawei as an entity on national security grounds. In December 2019, the U.S. used false charges to threaten TikTok. In recent years, the U.S. has successively put the hat of threatened national security on Chinese enterprises and implemented a joint ‘encirclement and suppression’ against these enterprises with allies such as Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, India, Singapore, and Canada.

Stigmatization and suppression aimed at Chinese enterprises by Western countries, led by the United States, is an organized and long-term behavior, a typical phenomenon of organizational stigmatization (Organizational stigmatization is defined as a deep questioning of the organization’s attributes by the public and a negative evaluation of the organization based on this questioning.) This is because the rapid development and growing market share of ZTE, Huawei, TikTok, and other Chinese enterprises threaten some countries. Hence, they have attempted to suppress and stigmatize Chinese enterprises through hegemony. Organizational stigmatization causes Chinese multinational enterprises to be labeled ‘with a political purpose’, ‘supported by the government’, ‘plundering resources’ and ‘plagiarizing intellectual property rights’ (Zhang & Du, Citation2020), resulting in enterprises facing great risk overseas which is not conducive for developing business.

Organizational stigmatization has a more severe impact on the overseas subsidiaries of multinational enterprises. Specifically, organizational stigmatization causes the host government to formulate more restrictive policies. This raises the access and legitimacy threshold for overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises to participate in host countries’ economic activities and increases enterprises’ operational costs. The host country’s media reports bias local enterprises against Chinese multinational enterprises. These may reduce business exchanges with Chinese affiliated enterprises and encourage cooperation with other enterprises. Additionally, host-country consumers have a mentality of excluding Chinese multinational enterprises and may reduce or refuse to buy relevant products. The comprehensive effect of multiple factors increases the operational difficulty and risk of the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises.

It is important to reveal the organizational stigmatization phenomenon experienced by Chinese enterprises and to investigate their impact on overseas subsidiaries. Therefore, this study established a research framework between organizational stigmatization and the operational risk and performance of overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises. Empirically, it analyzed the impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance. It then introduced factors to investigate whether they moderated the impact. Finally, we explored how organizational stigmatization affected overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance through an operational risk channel.

2. Literature review

Stigmatization is a dynamic process in which contaminated objects are derogated by stigmatized subjects and are constructed by stigmatized discourses (Jin & Qin, Citation2020). Pioneering research on stigmatization can be traced back to 1963 when sociologist Goffman (Citation1963) proposed the concept of stigma and conducted numerous researches. However, relevant research at the time remained at the individual level. In 1987, Sutton and Callahan (Citation1987) extended the concept of stigma to the organizational level and defined organizational stigmatization as a deep questioning of the public on the organization’s attributes and negatively evaluating the organization based on this question. Since then, organizational stigmatization has officially entered vision research.

Some scholars have employed research methods for measuring organizational stigmatization. Hudson and Okhuysen (Citation2009), Helms and Patterson (Citation2014), Roulet (Citation2015) and Tracey and Phillips (Citation2016) used qualitative methods to measure organizational stigmatization using archives and interview data. Other scholars have focused on the effects of organizational stigmatization. Gourley (Citation2019) used a shooting case from 1999 as an example to confirm stigmatization in society and quantified the impact of stigmatization on asset value. The study found that house prices in Colorado fell by 5.7%, and real estate sales lost $13 million after one year. Durand and Vergne (Citation2015) found that media attacks increased the possibility of divestment of core enterprises in stigmatized industries. Grougiou et al. (Citation2016) investigated the impact of organizational stigmatization on corporate social responsibility reports. The study found that enterprises affected by organizational stigmatization were more inclined to issue independent corporate social responsibility reports to distract the public from their business activities and reduce the negative impact of organizational stigmatization. Novak and Bilinski (Citation2018) investigated the impact of stigmatization on executive compensation. They found that executives in negative cognitive industries, such as tobacco and gambling, receive a salary premium to compensate for the additional costs of stigmatization.

Some studies extended the research on the impact of organizational stigmatization on international relations and demonstrated it from the perspective of multinational enterprises. Qi and Du (Citation2018) believed that owing to the organizational stigmatization of politically affiliated enterprises in internationalization, it is difficult to be accepted and recognized by the host country, reducing the performance of international M&A. Du and Zhang (Citation2019) found that the more serious the organization stigmatized multinational enterprises in foreign direct investment were, the lower their internationalization performance. They also found that the organizational stigmatization phenomenon against China caused Chinese enterprises to face a high threshold of legitimacy in the host country. Thus, enterprises prefer to use the joint venture model to enter the host country’s market (Zhang & Du, Citation2020). Yang (Citation2019) believed that Huawei and ZTE suffered significant discrimination owing to the stigmatization of organizational identity and that it was difficult to enter the U.S. market.

In summary, academic research on organizational stigmatization has achieved fruitful results but is still deficient. However, the measurement methods of organizational stigmatization at this stage start with typical events, industry attributes, anti-dumping activities, lack of large data support, and measurement accuracy need to be improved. In addition, research on the microeconomic impact of organizational stigmatization from the perspective of overseas subsidiaries is insufficient, especially on the mechanism by which organizational stigmatization affects overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance.

This study accurately used the big data of international public opinion to measure organizational stigmatization aimed at China. It then investigated the impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance based on the econometric model and enterprise data. Furthermore, host country factors were introduced to analyze the moderating effect of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance. Finally, from the perspective of overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk, this study explored the impact mechanism of organizational stigmatization on enterprises’ operating performance. This study provides new ideas for measuring organizational stigmatization. It provides a practical basis for an in-depth understanding of the impact of organizational stigmatization on the overseas subsidiaries of multinational enterprises.

3. Theory and hypotheses

The fundamental purpose of the host country’s stigmatization of China is to hinder its economic development. In the field of overseas investment, organizational stigmatization primarily affects overseas subsidiaries through cognition and policy. On the one hand, because of the host country’s stigmatized reports, local enterprises are biased against Chinese multinational enterprises (You & Wu, Citation2012). They may reduce business dealings with overseas Chinese subsidiaries and cooperate with other enterprises. In addition, the cognition, emotion, and decision-making behavior of host-country consumers are also affected by the media (Ramirez & Rong, Citation2012). Consumers are resistant to overseas subsidiaries and the related goods of Chinese multinational enterprises. Various factors increase the operational difficulties and risks of overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises and adversely affect their performance (Liu et al., Citation2016).

On the other hand, organizational stigmatization drives serious investment protectionism, which mainly manifests as an increase in restrictive measures taken by the host country against overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises, such as capital controls and discriminatory taxation. Capital controls restrict foreign investors’ investment opportunities (Henry, Citation2007) and reduce the efficiency of foreign capital (Jongwanich, Citation2019). Discriminatory taxation leads to an increase in market interest rates, which increases outward foreign direct investment enterprises’ financing difficulties and affects their operating costs and investment decisions (Alfaro et al., Citation2017). This increases the legitimacy and access threshold to participate in the host country’s economic activities, raises business risks, and affects the performance of multinational enterprises’ overseas subsidiaries (Li & Sun, Citation2017).

H1a: Organizational stigmatization increases operational risk and reduces the operational performance of the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises.

H1b: Organizational stigmatization reduces business performance by increasing the operational risk of the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises.

Chinese multinational enterprises are often mistaken by the host country based on ‘political purposes’. Because of their close relationship with the government, state-owned enterprises are more likely to be controlled by the Chinese government (Qu et al., Citation2022), receive more support from their home countries, and constitute unfair competition against the host country’s enterprises (Gotz & Jankowska, Citation2018). For political and security reasons, the host country focuses on reviewing state-owned enterprises (Yu et al., Citation2021). Hence, state-owned enterprises are vulnerable to unfair treatments, stricter tariff reviews, and higher entry barriers. Moreover, some scholars have found that large-scale projects are more likely to be hindered (Wang & Xiao, Citation2017). Most state-owned enterprises’ transnational investment projects are large-scale and involve key industries, which are the focus of investment restrictions in various countries. Therefore, the production and operational activities of overseas subsidiaries of Chinese state-owned multinational enterprises in the host country are often hindered.

H2: Compared with non-state-owned enterprises, organizational stigmatization has a greater adverse impact on the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese state-owned multinational enterprises.

Political stability measures the degree of social unrest and the probability of internal military conflict and terrorism in an economy. It determines the host country’s business operating environment and directly affects the operational risk and performance of overseas subsidiaries. The higher the host country’s political stability, the stronger the ability to maintain political order and continuity, and the less likely it is to be threatened by security. This means that overseas subsidiaries’ operating environments have greater stability (Wang, Citation2019) and less uncertainty. The degree of uncertainty is closely related to business operators’ confidence (Ilut & Schneider, Citation2014), financing costs (Arellano et al., Citation2019), and investment decisions (Gulen & Ion, Citation2016; Stokey, Citation2016) and is an important factor affecting business risks and performance. Therefore, a stable political environment in the host country can weaken the adverse impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries.

H3: The better the political stability of the host country, the smaller the adverse impact of organizational stigmatization on the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises.

The geographical distance between the home and host countries is closely related to the degree of information asymmetry between multinational and local enterprises (Li et al., Citation2022; Ragozzino, Citation2009). The farther the distance between the two countries, the greater the possibility of lacking relevant information by multinational enterprises, and the higher the information search cost and cognitive cost of the host country’s local enterprises. In this case, the impression of multinational enterprises depends primarily on the source country’s image and media reports in the host country (Andéhn et al., Citation2016). Influenced by stigmatized reports from the host country, local enterprises are prejudiced against Chinese multinational enterprises, which results in greater difficulties and challenges for overseas subsidiaries. The closer the geographical distance between the two countries, the lower the cognitive cost of host country stakeholders. In addition, there are more opportunities and channels to understand multinational enterprises, owing to the close economic and trade exchanges between both countries. The objective evaluation and judgment of multinational enterprises (Suh et al., Citation2016) can weaken the adverse impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries.

H4: The greater the geographic distance between the home country and the host country, the greater the adverse impact of organizational stigmatization on the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises.

4. Data and empirical model

4.1. Data source and processing

Data on organizational stigmatization were obtained from the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tones (GDELT). GDELT includes several sub-databases such as the event database (Event), global knowledge graph (GKG), global geographic graph (GGG), and global relationship graph (GRG). GDELT collects news data from the media in more than 100 languages, constantly captures media dynamics worldwide, and updates the data every 15 min. The three important information sources of the GDELT are the Agence France-Presse, the Associated Press, and the Xinhua News Agency.

This study used the GGG sub-database to query news reports related to organizational stigmatization. GGG provides the time, source, title, emotion, specific content, and other information on news reports used to depict stigmatizing reports against China. This study searched for reports related to organizational stigmatization of China through keyword queries, which are ‘China, national security threat’, ‘China is a threat’ and ‘threat from China’. The query period was from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019, and the query language was English.

Data on multinational enterprises and their overseas subsidiaries came from the overseas direct investment database of the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR). The samples registered in ‘tax haven’ and missing statistical data are excluded. The host country’s political stability data were obtained from the World Governance Indicators (WGI) database. The geographical distance between home and host countries was derived from the CEPII database. The GDP and population data for the host country were derived from the World Bank database.

By matching the data from the above multiple sources, we obtained relevant data on Chinese multinational enterprises’ overseas subsidiaries and the organizational stigmatization reports of the host country of overseas subsidiaries. Since stigmatization reports on China began to appear in the GDELT database after 2017, the research cycle began from 2017 to the end of 2019. Finally, the unbalanced panel data comprised 552 enterprise-year observations of 311 overseas subsidiaries of 240 Chinese multinational enterprises.

4.2. Models and variables

Based on the following equations and models, this study examined the impact and mechanism of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risks and the performance of Chinese multinational enterprises. EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) measures the degree of organizational stigmatization in each host country.

(1)

(1)

EquationEquations (2)(2)

(2) and Equation(3)

(3)

(3) were used to investigate the impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance.

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

EquationEquations (4)(4)

(4) and Equation(5)

(5)

(5) were used to investigate the moderating effect of the moderating factors on the relationship between organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance.

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) is used to investigate whether organizational stigmatization affects overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance through the operational risk channel.

(6)

(6)

where

is the organizational stigmatization index of host country j of overseas subsidiary i in year t and is composed of the product of the number and tone value of reports related to organizational stigmatization (Li & Meng, Citation2019). Since the tone values of relevant reports are negative, the product of

and

is forward-processed, and the logarithm is taken to facilitate calculation. Hence, the larger the

value, the higher the degree of organizational stigmatization and vice versa.

is the operational risk of overseas subsidiary i in year t, expressed as the fluctuation degree of enterprise profit margin (i.e., the standard deviation of the enterprise profit margin).

is the operational performance of an overseas subsidiary i in year t, expressed as the logarithm of enterprise business income.

and

represent year and industry dummy variables, respectively.

represents a random disturbance term that includes all other unobservable factors.

indicates the moderating variables, including the political stability (ps) of host country j of overseas subsidiary i in year t and geographical distance (distance) with China. The value of ps is between −2.5 and 2.5, with a larger value reflecting a country’s political stability. Distance is the logarithmic distance between the host country’s capital and that of China. X represents a series of control variables, including (1) the ratio of total liabilities to total assets of overseas subsidiaries (debt) (Ma et al., Citation2021); (2) the number of directors with overseas working experience of the parent company (director); (3) the age of the parent company (firmage); (4) return on net assets of the parent company (rona), the percentage of net profit to average shareholders’ equity; (5) the logarithm of the ratio of GDP to the population of the host country (pcgdp); and (6) overseas subsidiary size (size), the logarithm of total assets (Miah et al., Citation2021; Yun et al., Citation2021).

Based on the above data, models, and variables, this study employs EXCEL to reveal the statistical characteristics of organizational stigmatization, operational risk, and performance of overseas subsidiaries and then applies the program regress in STATA 15.0 to investigate the relationship among the three, heterogeneity, and moderating effects.

5. Statistical analysis

5.1. Statistics of the report number

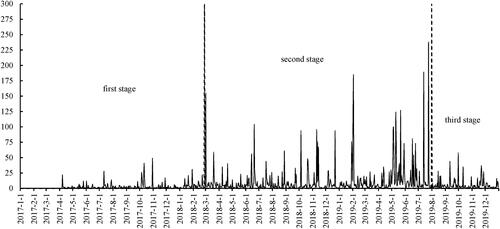

First, we plotted the changing trend in the number of organizational stigmatization reports aimed at China. As shown in , organizational stigmatization reports against China began to appear from April 2017 to the end of the investigation period. The changing trend in the number of reports shows considerable volatility. In the first stage, before March 2018, there were relatively few organizational stigmatization reports. In the second stage, from March 2018 to July 2019, the number of organizational stigmatization reports increased significantly, with multiple peaks. This stage corresponds to the Sino-US economic and trade friction. The United States believes that some goods imported from China will damage their domestic industry and threaten national security. Based on this, the United States launched multiple rounds of trade wars against China, which aroused great concern as evidenced in international public opinion. Therefore, the number of organizational stigmatization reports increased significantly during this period. In the third stage, after August 2019, when the Sino-US trade war entered a protracted tug, public opinion decreased, and the number of organizational stigmatization reports entered a stable period.

5.2. Statistics of organizational stigmatization of host countries

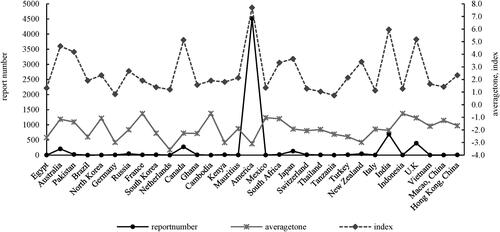

Next, we drew the organizational stigmatization reports of host countries. As shown in , 31 countries have reported organizational stigmatization in China. First, we examined the distribution characteristics of reported numbers. The number of organizational stigmatization reports in the United States is 4516, more than twice the total number of reports in all other countries. This is followed by India, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Japan, with 689, 394, 275, 206, and 132 organizational stigmatization reports, respectively. The organizational stigmatization reports of other countries were less than 100, and the countries with the lowest number of reports were Brazil, the Netherlands, Cambodia, and Tanzania.

Figure 2. The characteristics of relevant indicators of organizational stigmatization.

Source: Authors formation.

Second, we analyzed the average tone value of organizational stigmatization reports. As shown in , the tone values of all reports are negative, indicating that investment host countries use intense language in relevant reports and have negative attitudes. The most negative tone was in the Netherlands, which reached −3.58, followed by the United States, Kenya, Germany, and New Zealand, with average tone values of approximately −3. The average tone values for Egypt, Brazil, Turkey, Tanzania, Ghana, Switzerland, South Korea, Canada, and India ranged from −2 to −3. In contrast, other countries’ reported tones were relatively calm, with the least negative tones in France, Indonesia, and Cambodia.

We described the features of the organizational stigmatization index, which comprises the product of report number and tone value and is close to the distribution characteristics of the reported number. The United States has the greatest organizational stigmatization against China, with an index of 7.7. This is followed by India, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Pakistan, Japan, New Zealand, and South Africa, whose organizational stigmatization indices are between 3 and 6. The countries with the lowest stigmatization index are Tanzania, Germany, Thailand, Italy, and the Netherlands. This shows that these countries have low organizational stigmatization against China.

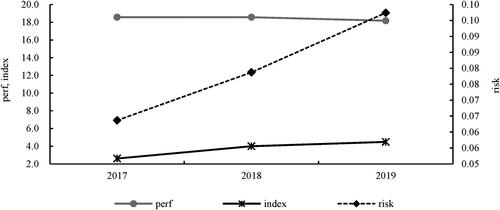

5.3. Trend of main indicators

We plotted the temporal trends of the main indicators. From , the index shows an upward trend, rising from 2.618 in 2017 to 4.492 in 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 30.98%, which shows that organizational stigmatization against China by investment host countries is increasing at a fast growth rate. Risk showed an obvious upward trend, rising from 0.064 in 2017 to 0.097 in 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 23.67%, indicating that overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises face greater and expanding operational risks. In contrast, perf did not rise but fell from 18.571 in 2017 to 18.175 in 2019, with an average annual growth rate of −1.07%, indicating that overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance in Chinese multinational enterprises is not ideal.

6. Empirical analysis

In this section, we first tested the impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance. Second, we conducted heterogeneous tests on the ownership subsamples. Third, the moderating effects of moderating factors on the relationship between organizational stigmatization, operational risk, and the performance of overseas subsidiaries were examined. Finally, the impact mechanism of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance was explored.

6.1. Benchmark regression

Based on EquationEquations (2)(2)

(2) and Equation(3)

(3)

(3) , we conducted a regression analysis on the impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance. The results are presented in the first and last three columns of . Columns (1) to (3) gradually added the control variables and fixed effects. The regression coefficient of the index in Column (3) is significantly positive. This indicates a positive correlation between organizational stigmatization and enterprises’ operational risk. This suggests that the host country’s organizational stigmatization behavior increases the operational risk of overseas subsidiaries. Therefore, it can be stated that the result supports the hypothesis H1a.

Table 1. The impact of organizational stigmatization on operational risk and performance.

For the control variables, the regression coefficients of size and director are not significant, indicating that subsidiaries’ size and number of directors with overseas work experience of the parent companies are not determinants of overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. The regression coefficient of debt is significantly positive, indicating that the higher the overseas subsidiaries’ asset-liability ratio, the greater is the operational risk. The regression coefficient of firmage is significantly negative, indicating that the longer the parent companies are established, the smaller the overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk.

Control variables and fixed effects were gradually added from columns (4) to (6) for operational performance. The regression coefficient of the index in Column (6) is significantly negative. This indicates a negative correlation between organizational stigmatization and operational performance. This illustrates that the host country’s organizational stigmatization behavior reduces the operational performance of overseas subsidiaries. Therefore, it can be stated that the result supports the hypothesis H1a.

Regarding the control variables, the regression coefficient of director is significantly positive, indicating that the more directors with overseas work experience in the parent companies, the higher the overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance. The regression coefficient of debt is significantly negative, indicating that the higher the asset-liability ratio of overseas subsidiaries, the lower the operational performance. The regression coefficient of rona is significantly positive, indicating that the higher the parent companies’ total asset net profit margin, the higher the overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance. The regression coefficient of firmage is significantly positive, indicating that the longer the parent companies are established, the higher the overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance. The regression coefficient of pcgdp is significantly positive, indicating that the higher the host country’s level of economic development, the better the overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance.

6.2. Heterogeneity tests

The benchmark regression results reflect the average impact of organizational stigmatization on all overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance. However, whether this impact differs due to the different ownership types of enterprises is not reflected. We divided all samples into two categories, state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises, according to the ownership type of the parent companies. presents the regression results.

Table 2. The heterogeneous impact based on the enterprises’ ownership.

The four regression coefficients of the index in show that compared with non-state-owned enterprises, organizational stigmatization increases overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk of state-owned enterprises and reduces their operational performance to a greater extent. In other words, the host country’s organizational stigmatization has a more serious adverse effect on the overseas subsidiaries. This may be because Chinese multinational enterprises are considered to have political purposes and are supported by the government when carrying out foreign investment; thus, they are stigmatized by the host country. State-owned enterprises are generally considered to have strong political connections and close relationships with governments. Therefore, state-owned enterprises present higher operational risks and lower operational performance because they may be more seriously stigmatized and suppressed by the host country. Therefore, it can be stated that the results support the hypothesis H2.

6.3. Moderating effect tests

We provided strong evidence that a host country’s organizational stigmatization increases operational risk and reduces the operational performance of overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises; given the importance of the host country’s political stability and geographical distance between the home and host countries, this section investigated whether these two factors moderate the relationship between organizational stigmatization, operational risk, and operational performance. shows the regression results.

Table 3. The moderating effect of political stability and geographical distance.

For political stability, the regression coefficient of the interaction term in Column (1) is significantly negative. This indicates that the host country’s political stability negatively moderates the positive correlation between organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. This means that the better the host country’s political stability, the lower is the adverse impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. The regression coefficient of the interaction term in Column (2) is not significant. This indicates that the host country’s political stability does not moderate the relationship between organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance. Therefore, it can be stated that the results support the hypothesis H3 partly. Additionally, the regression results of the control variables are consistent with the benchmark regression, indicating that the research results are robust.

As for geographical distance, the regression coefficient of the interaction item in Column (3) is significantly positive. This shows that geographical distance positively moderates the correlation between organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. This means that the greater the distance between the home and host countries, the greater the adverse impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. The regression coefficient of the interaction term in Column (4) is not significant. This indicates that the distance between the two countries does not moderate the relationship between organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance. Therefore, it can be stated that the results support the hypothesis H4 partly. Additionally, the regression results of the control variables are consistent with the benchmark regression, indicating that the research results are robust.

6.4. Mechanism test

In the benchmark regression, we found that organizational stigmatization increases operational risk and reduces the operational performance of overseas subsidiaries of Chinese multinational enterprises. Therefore, we wondered whether operational risk is the transmission channel of organizational stigmatization reducing the operational performance. Next, we explored the above conjecture.

According to EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) , the marginal effect of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance is

coefficient

is the focus of this study. If it is significantly positive, organizational stigmatization negatively impacts operational performance by increasing overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. We then verified this using data on organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries. As shown in Column (4) of after adding control variables and controlling for the fixed effects of year and industry, the coefficient of the interaction term is positive and passes the significance test at the 5% level. This shows that the host country’s organizational stigmatization reduces the overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance of Chinese multinational enterprises via the operational risk channel. Therefore, it can be stated that the result supports the hypothesis H1b.

Table 4. The mechanism of organizational stigmatization on operational performance.

7. Conclusion, limitations and future research directions

This study used GDELT international public opinion big data to measure the degree of organizational stigmatization of investment host countries against China by constructing an organizational stigmatization index. We then empirically tested the impact of organizational stigmatization on the operational risk and performance of Chinese multinational enterprises’ overseas subsidiaries based on CSMAR overseas direct investment data and an econometric model. Furthermore, we examined the moderating effects of the host country’s political stability and the geographical distance between the home and host countries on the above impact. Finally, we explored operational risk as the transmission channel of organizational stigmatization affecting overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance.

We obtained evidence on the impact of organizational stigmatization on Chinese overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk and performance. Organizational stigmatization increases the operational risk of Chinese multinational enterprises’ overseas subsidiaries; it is not conducive to improving their operational performance, which is more obvious in the overseas subsidiaries of state-owned enterprises. The host country’s political stability negatively moderates the positive impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. However, it did not significantly moderate the relationship between organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance. The geographical distance between home and host countries positively moderates the positive impact of organizational stigmatization on overseas subsidiaries’ operational risk. However, it did not significantly moderate the relationship between organizational stigmatization and overseas subsidiaries’ operational performance. The mechanism test shows that organizational stigmatization reduces enterprises’ operational performance by increasing the operational risk of overseas subsidiaries.

This study innovates a measurement method for organizational stigmatization. This lays a foundation for investigating the microeconomic impact of organizational stigmatization in the host country from the perspective of overseas subsidiaries of multinational enterprises. However, there are limitations and rooms for further improvement.

First, the GDELT database started to comprehensively capture news related to stigmatization in 2017, so the research cycle of this study is short. It is impossible to observe the long-term impact of organizational stigmatization on the operational risk and performance of Chinese multinationals’ overseas subsidiaries. We will continue to track this research topic and observe the differential impacts of the different economic development stages.

Second, this study’s research sample includes only overseas subsidiaries of Chinese listed companies. With the gradual improvement of research data in the future, it will be necessary to expand the research scope to all multinational enterprises. In particular, manufacturing has high scientific and technological content, which is not only the key industry of China’s overseas investment but also the most likely to be stigmatized. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on the manufacturing overseas subsidiaries.

Third, this study is aimed only at Chinese multinational enterprises. We will conduct more detailed research on multinational enterprises in different countries, find the best transnational investment model to combat the adverse effects of organizational stigmatization, and provide a reference for other multinational enterprises. In addition, the change in the economic gap between the home and host countries may affect the degree of the host country’s stigmatization and then affect the operational risk and performance of overseas subsidiaries, which is also a focus of attention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alfaro, L., Chari, A., & Kanczuk, F. (2017). The real effects of capital controls: Firm-level evidence from a policy experiment. Journal of International Economics, 108, 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.06.004

- Andéhn, M., Nordin, F., & Nilsson, M. E. (2016). Facets of country image and brand equity: Revisiting the role of product categories in country-of-origin effect research. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15(3), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1550

- Arellano, C., Bai, Y., & Kehoe, P. J. (2019). Financial frictions and fluctuations in volatility. Journal of Political Economy, 127(5), 2049–2103. https://doi.org/10.1086/701792

- Du, X. J., & Zhang, N. N. (2019). The effect of organizational stigma on the internationalization performance of enterprises. Foreign Economics & Management, 41(7), 112–124.

- Durand, R., & Vergne, J. P. (2015). Asset divestment as a response to media attacks in stigmatized industries. Strategic Management Journal, 36(8), 1205–1223. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2280

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice Hall.

- Gotz, M., & Jankowska, B. (2018). Outward foreign direct investment by polish state-owned multinational enterprises: Is “stateness” an asset or a burden? Post-Communist Economies, 30(2), 216–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2017.1361695

- Gourley, P. (2019). Social stigma and asset value. Southern Economic Journal, 85(3), 919–938.

- Grougiou, V., Dedoulis, E., & Leventis, S. (2016). Corporate social responsibility reporting and organizational stigma, the case of “sin” industries. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 905–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.06.041

- Gulen, H., & Ion, M. (2016). Policy uncertainty and corporate investment. Review of Financial Studies, 29(3), 523–564.

- Helms, W. S., & Patterson, K. D. W. (2014). Eliciting acceptance for “illicit” organizations, the positive implications of stigma for MMA organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1453–1484. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0088

- Henry, P. B. (2007). Capital account liberalization: Theory, evidence, and speculation. Journal of Economic Literature, 45(4), 887–935. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.45.4.887

- Hudson, B. A., & Okhuysen, G. A. (2009). Not with a ten-foot pole, core stigma, stigma transfer, and improbable persistence of men’s bathhouses. Organization Science, 20(1), 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0368

- Ilut, C. L., & Schneider, M. (2014). Ambiguous business cycles. American Economic Review, 104(8), 2368–2399. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.8.2368

- Jin, S. Y., & Qin, Z. D. (2020). “Stigmatization” and “de-stigmatization”, the discourse attack from western countries and our responsive action. Studies in Ideological Education, 9, 80–84.

- Jongwanich, J. (2019). Capital controls in emerging East Asia: How do they affect investment flows? Journal of Asian Economics, 62, 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2019.04.001

- Li, G., & Meng, L. J. (2019). Public opinion and international trade, an example of U.S. import. The Journal of World Economy, 42(8), 146–169.

- Li, X. R., Meng, M. M., & Lei, J. S. (2022). The research on the impact of geographical distance on corporate social responsibility. Chinese Journal of Management, 19(02), 254–262.

- Li, X. Y., & Sun, L. X. (2017). How do sub-national institutional constraints impact foreign firm performance? International Business Review, 26(3), 555–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.11.004

- Liu, X., Gao, L., Lu, J., & Eleni, L. (2016). Environmental risks, localization and the overseas subsidiary performance of MNEs from an emerging economy. Journal of World Business, 51(3), 356–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.05.002

- Ma, Y., Tikuye, G. A., & He, S. (2021). Impacts of firm performance on corporate social responsibility practices: The mediation role of corporate governance in Ethiopia corporate business. Sustainability, 13(17), 9717.

- Miah, M. D., Hasan, R., & Usman, M. (2021). Carbon emissions and firm performance: Evidence from financial and non-financial firms from selected emerging economies. Sustainability, 13(23), 13281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313281

- Novak, J., & Bilinski, P. (2018). Social stigma and executive compensation. Journal of Banking & Finance, 96, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2018.09.003

- Qi, C. S., & Du, X. J. (2018). A study of the impact of political connections on the international M&A performance of Chinese enterprises. Contemporary Finance & Economics, 1, 68–77.

- Qu, X., Li, R., & Li, W. X. (2022). A study on the impact of host country legal system on Chinese enterprises’ OFDI at the stage of entrance-an empirical analysis based on micro data of Chinese listed companies. Macroeconomics, 02, 27–41+136.

- Ragozzino, A. R. (2009). The effects of geographic distance on the foreign acquisition activity of U.S. firms. Management International Review, 49(4), 509–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-009-0006-7

- Ramirez, C. D., & Rong, R. (2012). China bashing: Does trade drive the “bad” news about China in the USA? Review of International Economics, 20(2), 350–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2012.01026.x

- Roulet, T. (2015). “What Good is Wall Street?” Institutional contradiction and the diffusion of the stigma over the finance industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(2), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2237-1

- Stokey, N. L. (2016). Wait-and-see: Investment options under policy uncertainty. Review of Economic Dynamics, 21, 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2015.06.001

- Suh, Y., Hur, J., & Davies, G. (2016). Cultural appropriation and the country of origin effect. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2721–2730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.11.007

- Sutton, R. I., & Callahan, A. L. (1987). The stigma of bankruptcy: Spoiled organizational image and its management. Academy of Management Journal, 30(3), 405–436. https://doi.org/10.2307/256007

- Tracey, P., & Phillips, N. (2016). Managing the consequences of organizational stigmatization, identity work in a social enterprise. Academy of Management Journal, 59(3), 740–765. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0483

- Wang, B. J., & Xiao, H. (2017). Which Chinese ODI is more likely to be blocked by political resistance in the host country? World Economics and Politics, 04, 106–128+159.

- Wang, J. B. (2019). Bilateral political relations, quality of host country institutions and location choice for China’s outward foreign direct investment: A quantitative analysis of Chinese OFDI from 2005-2017. Journal of Contemporary Asia-Pacific Studies, 03, 4–28+157.

- Yang, B. (2019). The dual disadvantages of multinational enterprises from emerging markets. Business and Management Journal, 41(1), 56–70.

- You, J. X., & Wu, J. (2012). Spiral of silence: Media sentiment and the asset mispricing. Economic Research Journal, 47(07), 141–152.

- Yu, G. S., Wu, Q. Q., & Dong, Z. R. (2021). The impact of international investment protection on China’s enterprises’ foreign direct investment: An empirical study from the perspective of overseas subsidiaries. South China Journal of Economics, 06, 68–86.

- Yun, J., Ahmad, H., Jebran, K., & Muhammad, S. (2021). Cash holdings and firm performance relationship: Do firm-specific factors matter? Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 34(1), 1283–1305. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1823241

- Zhang, N. N., & Du, X. J. (2020). Research on organizational stigma and choice of entry modes of Chinese enterprises in overseas markets, an empirical analysis based on listed companies. Contemporary Finance & Economics, 1, 77–88.