Abstract

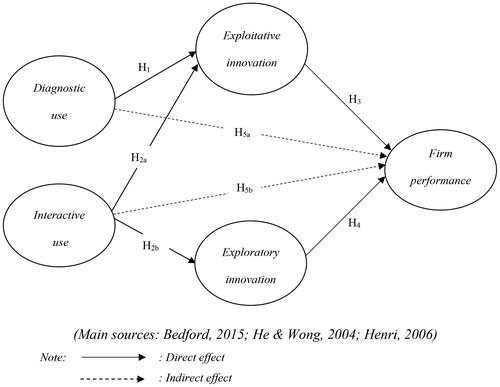

Drawing on prominent theories of innovation, this study investigates the inter-relationships between the use of management control systems (MCS), exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and firm performance in Vietnam, an emerging market. The research hypotheses were empirically tested using a partial least squares-structural equation model. Data were collected by survey questionnaires from a sample of 238 top-level and middle-level managers in Vietnamese firms. The results confirm that the diagnostic use of MCS has a significant positive effect on exploitative innovation and the interactive use of MCS has a significant positive effect on both exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation. The results also reveal that exploitative innovation and exploratory innovation partially mediate the relationship between the interactive use of MCS and firm performance. Understanding these relationships can assist Vietnamese firms to invest appropriately in MCS that is able to promote innovation actions, thereby achieving outstanding performance.

1. Introduction

In order to adapt to intense competition in a dynamic business environment, firms must seek to explore new ideas or processes and design new products and services for emerging markets. At the same time, they require stability so as to be able to utilize current competencies and exploit existing products and services (Danneels, Citation2002). To achieve such outcomes previous researchers have argued that firms need to be ‘ambidextrous’ (Cho et al., Citation2020; He & Wong, Citation2004; Venugopal et al., Citation2020), and develop simultaneous exploration and exploitation (Tushman & O'Reilly, Citation1996) to gain a sustainable competitive advantage, thereby improving firm performance.

Previous studies have highlighted the benefits of balancing exploration and exploitation (Cao et al., Citation2009; Dhir & Dhir, Citation2018; Hassan et al., Citation2022; He & Wong, Citation2004; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006). The question remains as to how the firms might promote both exploration and exploitation. The prior researchers have documented the required environmental, structural and behavioral antecedents (Jansen et al., Citation2006; Pertusa-Ortega & Molina-Azorín, Citation2018; Simsek et al., Citation2009), such as organizational context characteristics (Wei et al., Citation2014), formal and informal coordination mechanisms (Jansen et al., Citation2006), structural differentiation (Jansen et al., Citation2009; Pertusa-Ortega & Molina-Azorín, Citation2018), top management team diversity and decision-making processes (C.-R. Li et al., Citation2016). In addition, behavioral integration of the top management team (Ramachandran et al., Citation2019; Umans et al., Citation2020; Venugopal et al., Citation2020; Wu & Chen, Citation2020), top management team shared leadership (Umans et al., Citation2020), perceived organizational support and empowering leadership (Siachou & Gkorezis, Citation2018), and technology and market-sensing capabilities (L. V. Ngo et al., Citation2019), environmental dynamism (Haarhaus & Liening, Citation2020), have all received attention.

While many studies have recognized the role of management, little is known about the role of using MCS in promoting both exploration and exploitation (Gschwantner & Hiebl, Citation2016). Pursuing both contradictory activities simultaneously is often complicated and difficult (Benner & Tushman, Citation2003). Dekker et al. (Citation2013) has shown that firms with mixed strategies have a more complex performance management system (PMS), with various measures required to capture management needs so as to balance a trade-off between competing objectives. Bedford (Citation2015) has tested the role of promoting the performance of levers of control in the context of ambidextrous organizations. Severgnini et al. (Citation2018) have revealed the three dimensions of the PMS (attention to focus, strategic decision-making, legitimization of the firm’s choices) that increase organizational ambidexterity (which is to say, exploratory and exploitative innovations) and which consequently influence organizational performance. More recently, Mura et al. (Citation2021) have shown that the dynamic tension created by joint diagnostic and interactive use of PMS has the strongest association with organizational ambidexterity.

The MCS has long been recognized as having an important role in providing information for managers to perform their functions of planning, control, and decision-making (Bedford, Citation2015; Henri, Citation2006). Moreover, MCS is also leverage for innovation (Müller-Stewens et al., Citation2020) and is considered an important resource for competitive advantage (Barney, Citation1991). Therefore, it can be argued that MCS can contribute to the emergence of a firm’s innovation behavior, thereby improving firm performance. However, a review of prior studies reveals that existing research has focused only on the PMS as well as being restricted to developed countries (e.g., Bedford, Citation2015; Bedford et al., Citation2022; Dekker et al., Citation2013; Mura et al., Citation2021; Severgnini et al., Citation2018). There is a lack of consensus systematically on the relationship between the use of MCS, exploration, exploitation, and firm performance in the context of an emerging and dynamic market (like Vietnam). Legally, management accounting was officially recognized in Vietnamese Accounting Law, which was updated on June 17, 2003. In fact, the role of management accounting is not essential as management accounting used in companies is very simplistic (H. Q. Nguyen & Le, Citation2020). Recently, the study of Pham et al. (Citation2020) revealed that traditional management accounting practices (such as budgeting, standard costing, CVP analysis, responsibility accounting, and cost variance analysis) are dominated in Vietnamese firms. However, positive points can be recognized when 16 contemporary techniques (such as strategic costing, target costing, product profitability analysis, life-cycle costing, value chain analysis and so on) are selected by studied firms. Managers in Vietnamese firms are still weighing the costs and benefits of investing in MCS (T. T. Nguyen et al., Citation2017). In addition, as an emerging economy (V. D. Ngo et al., Citation2016; Q. A. Nguyen et al., Citation2015), Vietnam is recognized as a rapidly growing economy in the Asia-Pacific region (L. V. Ngo et al., Citation2019). Over the years, Vietnam has consistently been ranked as one of Asia’s best investment locations (L. V. Ngo et al., Citation2019). Like many emerging economies in Asia, Vietnam has undergone major economic shifts and has achieved a high rate of economic growth (V. D. Ngo et al., Citation2016). Firms operating in such an emerging economy must respond quickly to continuing changes in the business market (Luu, Citation2017). In addition, they must develop fast complementary capabilities that enable continuous innovation, so that they can be adaptive and responsive to new market conditions (L. V. Ngo et al., Citation2019). For such reasons, Vietnam is an ideal setting for empirically testing our model of the use of MCS, innovation and performance.

This study contributes to the literature by providing evidence for the important role of MCS as a tool to promote the innovation behaviors and outcomes necessary for firms in an emerging and dynamic economy (such as Vietnam). In addition to revealing how managers might successfully use MCS to pursue exploratory and exploitative innovations, the study seeks to illuminate how exploitative innovation and exploratory innovation mediate the relationship between the use of management accounting information and firm performance. By doing so, this study contributes to the literature on innovation and ambidexterity more specifically as well as the management accounting literature more generally.

2. Theory and hypotheses

2.1. Exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation

Drawing upon the conceptualization of March (Citation1991), exploration implies firm behaviors characterized by such as ‘search, variation, risk-taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery, and innovation’ (March, Citation1991, p. 71). In addition, exploration requires new knowledge or departure from existing knowledge (Benner & Tushman, Citation2003, Citation2015; O'Reilly & Tushman, Citation2013) for firms to make radical innovations activities, thereby meeting the needs of emerging customers or markets (Cao et al., Citation2009; Danneels, Citation2002; Jansen et al., Citation2006). Such approaches are expected to lead to new products/services designs, as well as opening up new markets (Bedford et al., Citation2019; Cho et al., Citation2020; Mura et al., Citation2021).

Exploitation implies ‘refinement, choice, production, efficiency, selection, implementation, and execution’ (March, Citation1991, p. 71). Exploitative innovations are incremental innovations and are designed to meet the needs of existing customers or markets (Benner & Tushman, Citation2015; Cao et al., Citation2009; Jansen et al., Citation2006). To achieve such outcomes, firms need to modify and/or improve the quality of existing products and services and increase effectively the firm’s production (Bedford et al., Citation2019; Cho et al., Citation2020; Mura et al., Citation2021). Hence, exploitation builds on existing knowledge so as to reinforce existing skills, processes, and structures (Benner & Tushman, Citation2003, Citation2015; O'Reilly & Tushman, Citation2013).

2.2. The diagnostic and interactive use of MCS

MCS is defined as formalised procedures and systems that use the information to maintain organisational activities. This includes the planning, budgeting, measuring, and communication systems that managers use for decision-making and evaluation (Bedford, Citation2015; Henri, Citation2006). ‘MCS is a broader term that encompasses management accounting system and also includes other controls such as personal or clan controls’ (Chenhall, Citation2006, p. 164). This study adopts the framework of control levers of Simons (Citation1995) including the approaches to using controls that have been widely used in recent MCS studies (Lopez-Valeiras et al., Citation2016; Matsuo et al., Citation2021; Müller-Stewens et al., Citation2020; Osma et al., Citation2022; Su et al., Citation2015).

The diagnostic use of MCS represents the traditional role of MCS which provides information to monitor, compare and evaluate actual performance from preset performance targets (Bedford, Citation2015; Henri, Citation2006). Information is produced by the MCS which alerts senior managers when actions or results do not match with preordained plans (Abernethy & Brownell, Citation1999; Bedford, Citation2015; Müller-Stewens et al., Citation2020). To achieve this, the management accounting department plays an important role in preparing and interpreting the information created by MCS. Data are reported through the formal reporting process, with senior managers only rarely involved in the process (Abernethy & Brownell, Citation1999; Bedford, Citation2015; Simons, Citation1995).

An interactive use of MCS is designed to stimulate the search for opportunities and encourage the emergence of new initiatives (Bedford, Citation2015; Henri, Citation2006; Simons, Citation1995). Because it includes dialogue and communication among senior managers as well as between top-level managers and subordinates (Bedford et al., Citation2019; Widener, Citation2007) and Henri (Citation2006, p. 533) have argued that when the MCS is used interactively ‘data are discussed and interpreted among organizational members of different hierarchical levels’. The significance of an interactive use of MCS is that it contributes to the breaking down of functional barriers and the hierarchical systems of capital constraining the flow of information within organizations (Abernethy & Brownell, Citation1999). Thus, this use of MCS can be expected to encourage and facilitate strategic change and product innovation (Bisbe & Otley, Citation2004; Lopez-Valeiras et al., Citation2016; Müller-Stewens et al., Citation2020; Su et al., Citation2015).

2.3. Hypotheses

The prior studies that build from the resource-based view of operations suggest that a diagnostic use of MCS constrains organizational capabilities. For example, Henri (Citation2006) concludes that a diagnostic use of PMS negatively affects a range of organizational capabilities, including market orientation, entrepreneurship, and organizational learning, and innovativeness. Because the diagnostic use focuses on mistakes and negative variances, some researchers (e.g., Henri, Citation2006; Simons, Citation1995) argue that this approach often stifles innovation, creativity and new opportunities for the organization. Nevertheless, Adler and Chen (Citation2011) argue that the diagnostic use of MCS may provide sufficient space and flexibility for subordinates to adjust their activities. In addition, such an approach may encourage single-loop learning through exploiting existing knowledge rather than expanding new knowledge (Bedford, Citation2015; Haas & Kleingeld, Citation1999; Widener, Citation2007), which in turn provides for exploitative innovation activities (Bedford, Citation2015; He & Wong, Citation2004; Mura et al., Citation2021). Therefore, our first hypothesis becomes:

H1: The diagnostic use of MCS has a positive effect on exploitative innovation.

Bisbe and Otley (Citation2004, p. 729) have hypothesized and concluded that the use of interactive MCS supports innovation ‘through the provision of guidance for search, triggering and stimulus of initiatives’. Henri (Citation2006) studied how the use of PMS affects organizational capabilities and finds that there are positive relationships between interactive use and organizational capabilities (innovativeness, market orientation, entrepreneurship, and organizational learning). Moreover, the exchange of information among managers increases the ability to access knowledge within the organization. Such exchange of information assists managers to combine existing knowledge and develop new knowledge based on exploration (Bedford, Citation2015; Bedford et al., Citation2019, Citation2022; Müller-Stewens et al., Citation2020). Therefore, we propose second hypothesis as follows:

H2a: The interactive use of MCS has a positive effect on exploitative innovation.

H2b: The interactive use of MCS has a positive effect on exploratory innovation.

H3: Exploitative innovation has a positive effect on firm performance.

H4: Exploratory innovation has a positive effect on firm performance.

H5a: The exploitative innovation and exploratory innovation mediate the relationship between the diagnostic use of MCS and firm performance.

H5b: The exploitative innovation and exploratory innovation mediate the relationship between the interactive use of MCS and firm performance.

3. Research method

3.1. Data collection

The sample comprised 4.277 firms that were selected from the Vietnam Trade Directory, General Statistics Office of Vietnam and CEO Club. The top-level managers or/and mid-level managers such as CEO, CFO, manufacturing managers, marketing managers, sales managers, research and development managers, were the target informants. They are able to provide reliable information and have a thorough understanding of their firm’s innovation and performance (Luu, Citation2017; Vorhies & Morgan, Citation2003). We selected the sample by a convenience method combined with use snowball sampling. This means we will ask all potential participants based on our accessibility of their contact details and a match with our research criteria. Salganik and Heckathorn (Citation2004) suggest that snowball sampling leads to methodically unbiased samples, allowing good sampling and even better than random sampling methods. Our survey was conducted from June to September 2020. The questionnaire was sent to the email address of targeted informants. A reminder email was relayed to the non-respondents after ten days. After three follow-ups, we received 237 responses, yielding a response rate of 5.54%. This participation rate is similar to the email-survey study of Schamberger et al. (Citation2013). Following Luu (Citation2017), we removed 61 small companies to ensure that organizational variables (i.e., the use of MCS, innovations and firm performance) could be applied and to ensure that a formal MCS is primed (T. T. Nguyen et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, medium and large firms are expected to have sufficient resources to pursue exploration and exploitation (Jansen et al., Citation2006; Vietnam Report, Citation2019). In order to have enough data for the study, we continued to seek the help of tax departments, customs departments and associations. As a result, we received 62 qualified responses to hard files. Thus, the usable responses were 238.

3.2. Variable measurement

First, the diagnostic use was applied to measure through a reflective measurement model. Four items were adopted following Henri (Citation2006) and as subsequently used in other studies (e.g., Su et al., Citation2015; Widener, Citation2007). Besides, the interactive use was based on the scale defined by Bisbe et al. (Citation2007) and was subsequently used in other studies (e.g., Bedford, Citation2015; Sakka et al., Citation2013). For each statement, respondents were asked to indicate their use of MCS on a five-point Likert ranging from (1) not at all to (5) very great extent.

Second, He and Wong (Citation2004) developed eight items to measure exploration and exploitation. Subsequently, this scale was adopted in many studies which were conducted in different settings (e.g., Cao et al., Citation2009; C.-R. Li et al., Citation2016; Lubatkin et al., Citation2006; Peng & Lin, Citation2021; Severgnini et al., Citation2018). In these studies, this scale was confirmed to have high reliability. The eight items were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 represents ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 represents ‘strongly agree’.

Last, most studies on MCS used managers’ subjective perceptions of performance (Otley, Citation2016). The subjective perceptions scales are a good substitute in the absence of objective data (Dess & Robinson, Citation1984). Therefore, we adopted the scale developed by Govindarajan (Citation1984), which has been subsequently adopted by other studies (Baines & Langfield-Smith, Citation2003; Hoque, Citation2011) to measure firm performance. The respondents were asked to indicate the performance of their firms relative to that of their competitors over the last three years in each of the ten items on a scale ranging from 1 (very unsatisfactory) to 5 (outstanding).

4. Research results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

The demographics information of the participating firms and respondents are shown in . Of the responding firms, 54.62% were from industry and construction industries, 36.56% from trade and services industries, and 8.82% from agriculture, forestry, and fisheries industries. In total, 95.38% of sampled firms have more than 100 full-time equivalent employees. In addition, 6.72% were state-owned firms, 65.13% were not state-owned firms, and 28.15% were foreign-invested firms. Of the informants, 82.35% were from mid-level managers, and 17.65% were top-level managers. The managers worked in many different departments such as marketing (10.92%), research and development (7.14%), manufacturing (12.18%), sales (16.39%), finance/accounting (39.50%), and others (13.87%). The informants had a mean industry experience of 9.17 years. The independent t-test between the earliest (25%) and latest (25%) responses reveals that there is no significant divergence, which reduces concerns that the data suffer from non-response bias (Armstrong & Overton, Citation1977).

Table 1. Demographics of informants.

4.2. Evaluation of measurement models

For measurement models, shows that the composite reliabilities (CR) of all reflective constructs were higher than 0.7 (ranging from 0.897 to 0.921), and Cronbach’s alpha was greater than 0.7 (ranging from 0.847 to 0.885) (Hair et al., Citation2017). Besides, the outer loadings of all observed variables ranged from 0.710 to 0.884, which is higher than the cut-off value of 0.50 (Hulland, Citation1999). The t-values of all items were well above 1.96 to be statistically significant (ranging from 12.908 to 51.183). The average variance extracted (AVE) values of all latent variables can be accepted because they are higher than 0.50 (ranging from 0.643 to 0.744) (Hair et al., Citation2017). These imply that the scales used in this study are highly reliable.

Table 2. Scale items and latent variable evaluation.

shows the discriminant validity of the scales. Item INTE5 is removed because cross-loading is less than 0.2 (Müller-Stewens et al., Citation2020) and the ratio of the larger variance to the smaller variance is less than 2 (Hair et al., Citation2019). After removing this item, the results show that the square roots of average variance extracted (AVE) of all reflective constructs ranging from 0.802 to 0.863 which were well above the corresponding correlations between these constructs (from 0.118 to 0.603). Moreover, the correlation coefficients of constructs (numbers below the diagonal) are smaller than the composite reliability (CR) (shown in with values from 0.897 to 0.921) demonstrating that the scales for constructs in the model ensure discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Moreover, the correlation coefficients among the variables are lower than the cut-off value of 0.7, thereby indicating satisfactory discriminant validity (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2012). Lastly, we employed the Heterotrait-Montrait (HTMT) test to evaluate the discriminant validity of constructs (Henseler et al., Citation2015). shows that the HTMT values, which were computed based on the bootstrapping routine, ranging between 0.142 and 0.665 (significantly below 0.90), provide clear evidence for discriminant validity.

Table 3. Construct means, standard deviations, and correlations.

4.3. Hypothesis testing

The results in reveals that the diagnostic use of MCS significantly positively affects exploitative innovation (β = 0.145, p < 0.05, t = 2.517), in support of hypothesis H1. In addition, reveals that interactive use significantly positively affects exploitative innovation (β = 0.563, p < 0.01, t = 8.374) as well as exploratory innovation (β = 0.557, p < 0.01, t = 9.745), thereby supporting hypotheses H2a and H2b. Hypotheses H3 and H4 are also supported as confirmed by which reveals that exploitative innovation (β = 0.162, p < 0.05, t = 2.147) and exploratory innovation (β = 0.306, p < 0.01, t = 4.314) have a significant positive effect on firm performance.

Table 4. Partial least squares result for theoretical model.

Regarding indirect hypotheses, we find that exploitative innovation and exploratory innovation fail to mediate the relationship between diagnostic use and firm performance (β = 0.023, p > 0.05, t = 1.410). Thus, hypothesis H5a is not supported. Conversely, reveals that the effect of interactive use on firm performance via exploitative innovation and exploratory innovation is significant (β = 0.262, p < 0.01, t = 4.278), thereby supporting hypothesis H5b. Regarding the mediating types, reveals that use of interactions directly affects firm performance (Model 2, β = 0.238, p < 0.01, t = 3.424). Moreover, the indirect effect and the direct effect are both significant and point in the same direction, implying that exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation are complementary mediations for the relationship between interactive use and firm performance (Hair et al., Citation2017).

4.4. Model fit and common method bias

The diagnostic test of multicollinearity is based on the variance inflation factors (VIF) for the regression coefficients and reveals that the largest VIF in the model is 2.146, substantially less than the critical threshold of 5 (Hair et al., Citation2017). Therefore, multicollinearity is not a concern for the conclusions derived from the parameter estimates. Next, the adjusted R2 for dependent variables (exploratory innovation = 0.307, explorative innovation = 0.377, and firm performance = 0.332) were greater than the recommended level of 0.10 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Finally, the result of running Blindfolding shows that all Q2 values are positive (exploratory innovation = 0.225, explorative innovation = 0.249, and firm performance = 0.164), implying that models have medium predictive relevance (Hair et al., Citation2017).

To check for the common method bias, we apply two methods of Harman’s single-factor analysis and the marker variable technique that are commonly applied in cross-sectional research studies (e.g., Lopez-Valeiras et al., Citation2016; Müller-Stewens et al., Citation2020; L. V. Ngo et al., Citation2019). Firstly, Harman’s single-factor test is conducted to assess common method bias. The first factor accounted for only 32.914% of the total variance, implying that single-source bias is not a significant concern (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Secondly, we applied the marker variable technique (Lindell & Whitney, Citation2001) using the marker variable: ‘Are you satisfied with your phone service?’ to control for common method bias. Analysis results show that there is no significant correlation between the marker variable and the dependent variables. The mean change in the correlations of the key constructs (ru—ra) accounting for the effect of rm was 0.003, providing evidence of no common method bias in this study.

5. Discussions

This study examines the roles of using MCS to promote the simultaneous achievement of exploitation and exploration and, ultimately, in enhancing firm performance. In this research, we focused on two different types of uses of MCS—diagnostic and interactive. Interestingly, our study supports hypothesis H1 that diagnostic use contributes to the achievement of exploitative innovation. Although prior studies have suggested that diagnostic use reduces organizational capabilities (Henri, Citation2006) and firm performance (Yuliansyah et al., Citation2019), our study shows that diagnostic contributes to promoting exploitative initiatives and efforts by the firm. This is in line with studies that considered it as a means to stimulate problem-solving and increase managers’ focus on the achievement of operational and strategic goals (Bedford, Citation2015; Grafton et al., Citation2010). With the results accepting hypothesis H2a-b, we have highlighted the potential of an interactive use to significantly affect both exploration and exploitation. The noted effects are the outcome of the encouragement to managerial members to openly discuss and debate conflicting exploratory and exploitative demands and goals within their firm. Thereby, strategic contradictions and conflicts as arising from integrating and implementing spatially dispersed exploratory and exploitative activities are more satisfactorily resolved (Jansen et al., Citation2009).

To test the developed hypotheses H3 and H4, this paper applies exploration versus exploitation constructs to capture the different logics of technological innovation activities (Cao et al., Citation2009; He & Wong, Citation2004; Liu & Chen, Citation2015). As predicted, our empirical results support the hypotheses that both exploration and exploitation enhance firm performance. First of all, firms that pursue exploration have significantly increased firm performance. This suggests that a key to gaining performance in competitive and emerging economies (such as Vietnam) can be the development of new radical products and services for emerging markets and customers (Jansen et al., Citation2009; Jansen et al., Citation2006). Thus, although the pursuit of exploration involves risk, it nevertheless offers a way to establishment of new markets for long-term competitive advantage. In addition, our findings also show that business firms that pursue exploitation can improve their performance. Thereby, besides exploring new products and markets, firms can expand current products and services and defend existing markets for increasing customer loyalty, in effect, being able to successfully operate in more dynamic and competitive conditions.

Regarding the mediating role of exploration and exploitation (H5a and H5b), our findings reveal that both innovations mediate the effects of the interactive use of MCS on firm performance. Specifically, the two innovation types are complementary mediation for the relationship between interactive use and performance. Our findings confirm that their combination provides a foundational resource for competitive advantages, thereby achieving superior performance. A reasonable explanation is that simultaneously pursuing both explorative (radical) and exploitative (incremental) innovation allows the firm to identify both its ability and capabilities (Tushman & O'Reilly III, 1996). Moreover, such a valuable identification is both rare and costly to imitate (Simsek et al., Citation2009), so it becomes a competitive advantage source (Barney, Citation1991).

6. Conclusions

This study’s purpose is to test the relationship between the use of MCS, exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and firm performance. The results support all hypotheses that are proposed, except for hypothesis H5a. Thereby, the results confirm that the diagnostic use of MCS has a significant positive effect on exploitative innovation and the interactive use of MCS has a significant positive effect on both exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation. Especially, this study also shows that exploitative innovation and exploratory innovation partially mediate the relationship between the interactive use of MCS and firm performance.

6.1. Implications for theory

Firstly, the research on exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation has expanded rapidly. Nevertheless, our understanding of the antecedents of both activities remains rather incomplete (Chakma et al., Citation2021; O'Reilly & Tushman, Citation2013). First, Our study has highlighted fresh insights regarding the potential for the role of MCS as leverage for increasing the level of exploration and exploitation with a consequent improvement of firm performance. The results of our study reveal that diagnostic use has a positive effect on exploitation while interactive use positively affects both exploitation and exploration. These findings suggest that exploration is best achieved through interactive use only. Because the interactive use is said to foster capabilities that enhance exploration by focusing managers’ attention on strategic priorities and by stimulating dialogue across the organization (Bedford, Citation2015; Henri & Wouters, Citation2020). Conversely, the diagnostic use as a means to create constraints and to ensure compliance with orders, and therefore as a barrier to introducing new processes, technologies and offerings (Bititci et al., Citation2018; Henri, Citation2006).

Secondly, because both exploitative and exploration positively affect performance, firms may seek to combine the magnitude of the two, consistent with exploration and exploitation being orthogonal activities (Gupta et al., Citation2006). The ability of firms to pursue both exploitation and exploration simultaneously provides an ongoing debate in the literature, to which this study has contributed. Thus, for example, Porter (Citation1998) argues that firms have to trade-off between exploration and exploitation because the pursuit of these two innovative activities incompatible required skills, processes and performance appraisals. However, a more recent and growing literature argues that exploration and exploitation processes are not necessarily in fundamental opposition and may actually be mutually enhancing (Gupta et al., Citation2006) and this perspective is supported by empirical evidence relating to technological innovation (e.g., Cao et al., Citation2009; He & Wong, Citation2004) and organizational learning (Gupta et al., Citation2006; Suzuki, Citation2019).

6.2. Implications for practice

The study has contributed to managerial implications for top-level and middle-level management. Prior research has left it unclear whether the concern should be with trade-offs between such as exploration and exploitation or with the attempt to achieve high levels of both simultaneously. In the context of the emerging market that is Vietnam, our findings indicate that the simultaneous pursuit of exploration and exploitation is both possible and desirable. In order to compete effectively in the short term and survive in the long term, we recommend that managers need to manage the tension between exploration and exploitation continuously through the development of organizational capabilities to create competitive advantage (Henri, Citation2006; Tian et al., Citation2021), more especially, an ambidextrous capacity that is increasingly important for the sustained competitive advantage of firms (Junni et al., Citation2013). In particular, the study recommends that Vietnamese firms need to avail of MCS in both diagnostic and interactive manners, with a special emphasis on interactive manner. The implication is that, in the face of complex innovative decisions - such as whether or not to innovate radically, and how much resources should be devoted to exploitation and to exploration - managers need to debate thoroughly and discuss extensively in the lights of their MCS (Bedford et al., Citation2019).

6.3. Limitations and future research directions

First, our data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the next studies may collect data during the normal period to provide more robust evidence of these relationships. Second, to control the common method bias from the study design stage, subsequent studies should divide the questionnaire into two parts and send it to two managers, who represent a company, to answer two questionnaires (Cao et al., Citation2009; Jansen et al., Citation2006). Alternatively, future research may consider a longitudinal research design to provide evidence of causal linkages among constructs over time (Jansen et al., Citation2009; Jansen et al., Citation2006; Luu, Citation2017). Finally, although we recognize that MCS should be used in interactive and diagnostic manners simultaneously, we have not considered the effect of their interaction on innovation types and performance (Henri, Citation2006). Future studies might usefully seek to fill this research gap in the literature on MCS research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abernethy, M. A., & Brownell, P. (1999). The role of budgets in organizations facing strategic change: An exploratory study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24(3), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(98)00059-2

- Adler, P. S., & Chen, C. X. (2011). Combining creativity and control: Understanding individual motivation in large-scale collaborative creativity. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 36(2), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2011.02.002

- Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400320

- Baines, A., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2003). Antecedents to management accounting change: A structural equation approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(7-8), 675–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(02)00102-2

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Bedford, D. S. (2015). Management control systems across different modes of innovation: Implications for firm performance. Management Accounting Research, 28, 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2015.04.003

- Bedford, D. S., Bisbe, J., & Sweeney, B. (2019). Performance measurement systems as generators of cognitive conflict in ambidextrous firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 72, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.05.010

- Bedford, D. S., Bisbe, J., & Sweeney, B. (2022). The joint effects of performance measurement system design and TMT cognitive conflict on innovation ambidexterity. Management Accounting Research, 57, 100805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2022.100805

- Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2003). Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. The Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.9416096

- Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2015). Reflections on the 2013 decade award—“Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited” ten years later. Academy of Management Review, 40(4), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2015.0042

- Bisbe, J., Batista-Foguet, J.-M., & Chenhall, R. (2007). Defining management accounting constructs: A methodological note on the risks of conceptual misspecification. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7-8), 789–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.010

- Bisbe, J., & Otley, D. (2004). The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on product innovation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(8), 709–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2003.10.010

- Bititci, U. S., Bourne, M., Cross, J. A. F., Nudurupati, S. S., & Sang, K. (2018). Towards a theoretical foundation for performance measurement and management. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(3), 653–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12185

- Bresciani, S., Rehman, S. U., Alam, G. M., Ashfaq, K., & Usman, M. (2023). Environmental MCS package, perceived environmental uncertainty and green performance: In green dynamic capabilities and investment in environmental management perspectives. Review of International Business and Strategy, 33(1), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-01-2022-0005

- Cao, Q., Gedajlovic, E., & Zhang, H. (2009). Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organization Science, 20(4), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0426

- Chakma, R., Paul, J., & Dhir, S. (2021). Organizational ambidexterity: A review and research agenda. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2021.3114609

- Chenhall, R. H. (2006). Theorizing contingencies in management control systems research. Handbooks of Management Accounting Research., 1, 163–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1751-3243(06)01006-6

- Cho, M., Bonn, M. A., & Han, S. J. (2020). Innovation ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for startup and established restaurants and impacts upon performance. Industry and Innovation, 27(4), 340–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2019.1633280

- D'Aveni, R. A. (1994). Hypercompetition: Managing the dynamics of strategic maneuvering. Free Press.

- Danneels, E. (2002). The dynamics of product innovation and firm competences. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1095–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.275

- Dekker, H. C., Groot, T., & Schoute, M. (2013). A balancing act? The implications of mixed strategies for performance measurement system design. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 25(1), 71–98. https://doi.org/10.2308/jmar-50356

- DeSarbo, W. S., Anthony Di Benedetto, C., Song, M., & Sinha, I. (2005). Revisiting the Miles and Snow strategic framework: Uncovering interrelationships between strategic types, capabilities, environmental uncertainty, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 26(1), 47–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.431

- Dess, G. G., & Robinson, R. B. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately‐held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic Management Journal, 5(3), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050306

- Dhir, S., & Dhir, S. (2018). Role of ambidexterity and learning capability in firm performance: A study of e-commerce industry in India. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 48(4), 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-10-2017-0073

- Lavie, D. (2006). Capability reconfiguration: An analysis of incumbent responses to technological change. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379629

- Ferreira, J., Cardim, S., & Coelho, A. (2021). Dynamic capabilities and mediating effects of innovation on the competitive advantage and firm’s performance: The moderating role of organizational learning capability. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 12(2), 620–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-020-00655-z

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Govindarajan, V. (1984). Appropriateness of accounting data in performance evaluation: An empirical examination of environmental uncertainty as an intervening variable. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 9(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(84)90002-3

- Grafton, J., Lillis, A. M., & Widener, S. K. (2010). The role of performance measurement and evaluation in building organizational capabilities and performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(7), 689–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2010.07.004

- Gschwantner, S., & Hiebl, M. R. (2016). Management control systems and organizational ambidexterity. Journal of Management Control, 27(4), 371–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-016-0236-3

- Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Shalley, C. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22083026

- Haarhaus, T., & Liening, A. (2020). Building dynamic capabilities to cope with environmental uncertainty: The role of strategic foresight. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 155, 120033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120033

- Haas, M., & Kleingeld, A. (1999). Multilevel design of performance measurement systems: Enhancing strategic dialogue throughout the organization. Management Accounting Research, 10(3), 233–261. https://doi.org/10.1006/mare.1998.0098

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis. Cengage Learning.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hassan, S. M., Rahman, Z., & Paul, J. (2022). Consumer ethics: A review and research agenda. Psychology & Marketing, 39(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21580

- He, Z.-L., & Wong, P.-K. (2004). Exploration vs. exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organization Science, 15(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0078

- Henri, J.-F. (2006). Management control systems and strategy: A resource-based perspective. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(6), 529–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2005.07.001

- Henri, J.-F., & Wouters, M. (2020). Interdependence of management control practices for product innovation: The influence of environmental unpredictability. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 86, 101073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2019.101073

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hidalgo-Peñate, A., Padrón-Robaina, V., & Nieves, J. (2019). Knowledge as a driver of dynamic capabilities and learning outcomes. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 24, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.02.004

- Hoque, Z. (2011). The relations among competition, delegation, management accounting systems change and performance: A path model. Advances in Accounting, 27(2), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2011.05.006

- Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2

- Jansen, J. J., Tempelaar, M. P., Van den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2009). Structural differentiation and ambidexterity: The mediating role of integration mechanisms. Organization Science, 20(4), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0415

- Jansen, J. J., Van Den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2006). Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science, 52(11), 1661–1674. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0576

- Jiang, X., & Li, Y. (2009). An empirical investigation of knowledge management and innovative performance: The case of alliances. Research Policy, 38(2), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.11.002

- Junni, P., Sarala, R. M., Taras, V., & Tarba, S. Y. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity and performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0015

- Leonard‐Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 13(S1), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250131009

- Li, D-y., & Liu, J. (2014). Dynamic capabilities, environmental dynamism, and competitive advantage: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Research, 67(1), 2793–2799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.007

- Li, C.-R., Liu, Y.-Y., Lin, C.-J., & Ma, H.-J. (2016). Top management team diversity, ambidextrous innovation and the mediating effect of top team decision-making processes. Industry and Innovation, 23(3), 260–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2016.1144503

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114

- Liu, T.-C., & Chen, Y.-J. (2015). Strategy orientation, product innovativeness, and new product performance. Journal of Management & Organization, 21(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2014.63

- Lopez-Valeiras, E., Gonzalez-Sanchez, M. B., & Gomez-Conde, J. (2016). The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on process and organizational innovation. Review of Managerial Science, 10(3), 487–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-015-0165-9

- Lubatkin, M. H., Simsek, Z., Ling, Y., & Veiga, J. F. (2006). Ambidexterity and performance in small-to medium-sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. Journal of Management, 32(5), 646–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306290712

- Luu, T. T. (2017). Ambidextrous leadership, entrepreneurial orientation, and operational performance: Organizational social capital as a moderator. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(2), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-09-2015-0191

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

- Matsuo, M., Matsuo, T., & Arai, K. (2021). The influence of an interactive use of management control on individual performance: Mediating roles of psychological empowerment and proactive behavior. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 17(2), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-06-2020-0079

- Müller-Stewens, B., Widener, S. K., Möller, K., & Steinmann, J.-C. (2020). The role of diagnostic and interactive control uses in innovation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 80, 101078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2019.101078

- Mura, M., Micheli, P., & Longo, M. (2021). The effects of performance measurement system uses on organizational ambidexterity and firm performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 41(13), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-02-2021-0101

- Ngo, L. V., Bucic, T., Sinha, A., & Lu, V. N. (2019). Effective sense-and-respond strategies: Mediating roles of exploratory and exploitative innovation. Journal of Business Research, 94, 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.050

- Ngo, V. D., Janssen, F., Leonidou, L. C., & Christodoulides, P. (2016). Domestic institutional attributes as drivers of export performance in an emerging and transition economy. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2911–2922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.060

- Nguyen, H. Q., & Le, O. T. T. (2020). Factors affecting the intention to apply management accounting in enterprises in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(6), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no6.095

- Nguyen, Q. A., Sullivan Mort, G., & D'Souza, C. (2015). Vietnam in transition: SMEs and the necessitating environment for entrepreneurship development. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 27(3-4), 154–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2015.1015457

- Nguyen, T. T., Mia, L., Winata, L., & Chong, V. K. (2017). Effect of transformational-leadership style and management control system on managerial performance. Journal of Business Research, 70, 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.018

- O'Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present and future. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 324–338. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0025

- Osma, B. G., Gomez-Conde, J., & Lopez-Valeiras, E. (2022). Management control systems and real earnings management: Effects on firm performance. Management Accounting Research, 55, 100781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2021.100781

- Otley, D. (2016). The contingency theory of management accounting and control: 1980–2014. Management Accounting Research, 31, 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2016.02.001

- Peng, M. Y.-P., & Lin, K.-H. (2021). Disentangling the antecedents of the relationship between organisational performance and tensions: Exploration and exploitation. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 32(5-6), 574–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2019.1604130

- Pertusa-Ortega, E. M., & Molina-Azorín, J. F. (2018). A joint analysis of determinants and performance consequences of ambidexterity. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 21(2), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2018.03.001

- Pham, D. H., Dao, T. H., & Bui, T. D. (2020). The impact of contingency factors on management accounting practices in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(8), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no8.077

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Porter, M. E. (1998). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. Free Press.

- Ramachandran, I., Lengnick-Hall, C. A., & Badrinarayanan, V. (2019). Enabling and leveraging ambidexterity: Influence of strategic orientations and knowledge stock. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(6), 1136–1156. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2018-0688

- Rehman, S-u., Mohamed, R., & Ayoup, H. (2019). The mediating role of organizational capabilities between organizational performance and its determinants. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0155-5

- Sakka, O., Barki, H., & Côté, L. (2013). Interactive and diagnostic uses of management control systems in IS projects: Antecedents and their impact on performance. Information & Management, 50(6), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.02.008

- Salganik, M. J., & Heckathorn, D. D. (2004). Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent‐driven sampling. Sociological Methodology, 34(1), 193–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x

- Schamberger, D. K., Cleven, N. J., & Brettel, M. (2013). Performance effects of exploratory and exploitative innovation strategies and the moderating role of external innovation partners. Industry & Innovation, 20(4), 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2013.805928

- Severgnini, E., Vieira, V. A., & Cardoza Galdamez, E. V. (2018). The indirect effects of performance measurement system and organizational ambidexterity on performance. Business Process Management Journal, 24(5), 1176–1199. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-06-2017-0159

- Siachou, E., & Gkorezis, P. (2018). Empowering leadership and organizational ambidexterity: A moderated mediation model. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 6(1), 94–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-02-2017-0010

- Simons, R. (1995). Levers of control - how managers use innovative control systems to drive strategic renewal. Harvard Business School Press.

- Simsek, Z., Heavey, C., Veiga, J. F., & Souder, D. (2009). A typology for aligning organizational ambidexterity’s conceptualizations, antecedents, and outcomes. Journal of Management Studies, 46(5), 864–894. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00841.x

- Slater, S. F., & Narver, J. C. (1995). Market orientation and the learning organization. Journal of Marketing, 59(3), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299505900306

- Su, S., Baird, K., & Schoch, H. (2015). The moderating effect of organisational life cycle stages on the association between the interactive and diagnostic approaches to using controls with organisational performance. Management Accounting Research, 26, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2014.09.001

- Suzuki, O. (2019). Uncovering moderators of organisational ambidexterity: Evidence from the pharmaceutical industry. Industry and Innovation, 26(4), 391–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2018.1431525

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson.

- Tian, X., Lo, V. I., & Zhai, X. (2021). Combining efficiency and innovation to enhance performance: Evidence from firms in emerging economies. Journal of Management & Organization, 27(2), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2018.75

- Tushman, M. L., & O'Reilly, C. A. III, (1996). Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. California Management Review, 38(4), 8–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165852

- Umans, T., Smith, E., Andersson, W., & Planken, W. (2020). Top management teams’ shared leadership and ambidexterity: The role of management control systems. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 86(3), 444–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318783539

- Venugopal, A., Krishnan, T., Upadhyayula, R. S., & Kumar, M. (2020). Finding the microfoundations of organizational ambidexterity-Demystifying the role of top management behavioural integration. Journal of Business Research, 106, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.08.049

- Vietnam Report. (2019). Report Vietnam CEO Insight 2019: Digital Transformation and opportunity of Vietnamese Businesses.

- Vorhies, D. W., & Morgan, N. A. (2003). A configuration theory assessment of marketing organization fit with business strategy and its relationship with marketing performance. Journal of Marketing, 67(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.1.100.18588

- Wei, Z., Yi, Y., & Guo, H. (2014). Organizational learning ambidexterity, strategic flexibility, and new product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(4), 832–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12126

- Widener, S. K. (2007). An empirical analysis of the levers of control framework. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7-8), 757–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.01.001

- Wu, H., & Chen, J. (2020). International ambidexterity in firms’ innovation of multinational enterprises from emerging economies: An investigation of TMT attributes. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(3), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-07-2019-0267

- Yuliansyah, Y., Khan, A. A., & Fadhilah, A. (2019). Strategic performance measurement system, firm capabilities andcustomer-focused strategy. Pacific Accounting Review, 31(2), 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-09-2018-0068