Abstract

In this article, the following three subjects are identified: (1) as the quantitative evidence shows in the first section of this article, democracy in the US has deteriorated since 2016; (2) there could be multiple possible causes for the deterioration of American democracy. In particular, conjunctural opportunities give populist leaders an opening to project authoritarian schemes in the US against the backdrop of political sectarianism and the rise of negative partisanship; (3) the presidency of Donald Trump could be regarded as a cause of degradation of American democracy. Many of Trump’s traits and actions as president of the United States were damaging to American democracy. However, because Trumpism has not thoroughly permeated the Republican party, a barrier exists against further deterioration or even a transition to authoritarianism.

Introduction

On November 3, 2020, the reelection bid of Donald Trump failed. After that, Dr. Samantha Power wrote as follows:

“Some Americans are confident that after four years of Trump, the relief in foreign capitals will be so immense that U.S. leadership on key issues will be readily welcomed … reeling from a deadly pandemic, alienated by the United States’ xenophobic turn, and hungering for a form of governance that is accountable to the people. They would also remind the world not of the nebulous “return of U.S. leadership” but of specific U.S. capabilities. These assets, squandered or neglected by Trump, remain core strengths that only the United States has the means to project (Power, Citation2021, 12, 24).”

Dr. Power thought Trump’s administration threatened American democracy, and the end of his administration calmed serious concerns raised regarding the democracy of the US. However, Trump supporters, such as U.S. Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), insisted the presidential election “was stolen,” and she saw “a lot of evidence of voter fraud.”Footnote1 She claimed the Democratic-run government was “tyrannically controlled” and denounced the impeachment trial of Donald Trump as a “circus.”Footnote2

After the defeat, in response to Trump’s “stop the steal” campaign, Trump supporters gathered to protest the election results in the streets of Tokyo, Japan, the country in which the author lives. Hours before the storming of the U.S. Capitol, a crowd of a few hundred people in Tokyo got together and chanted “Fight for Trump” for the embattled US president.Footnote3 On the other hand, Japanese media published numerous opinions and articles criticizing Trump’s demeanor which they asserted harmed the integrity of the US electoral system.Footnote4

Oddly, the pros and cons for Trump both claimed, “American democracy is under serious threat,” and they insisted on acting to “defend” American democracy from the collapse caused by the other side. However, as the author wrote in a different article, we need to “learn more before we make assertions (Nishikawa, Citation2020 pp.359-360).” Before we make unfounded arguments, we first need to understand the following questions: (1) is the democracy of the US deteriorating? If so, is there any quantitative evidence to support the claim? (2) What are the possible causes of this upset that took place in American democracy? (3) Can the presidency of Donald Trump be regarded as a cause of degradation of American democracy? If so, to what extent has Trump altered American democracy? In seeking the answers, the author refers to articles published in top-ranked international journals.

Is the quality of democracy in the United States deteriorating?

“After the Cold War ended, it looked like democracy was on the march. But that confident optimism was misplaced. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that it was naive to expect democracy to spread to all corners of the world. The authoritarian turn of recent years reflects the flaws and failings of democratic systems (Mounk, Citation2021, 163-173).”

So wrote political scientist Dr. Yascha Mounk: some scholars and pundits point out that democracy is eroding, and authoritarianism is resurging worldwide. According to Dr. Larry Diamond, a scholar in the field of democracy studies, the expansion of freedom and democracy has faced a protracted stagnation. Moreover, the average level of freedom in the world had deteriorated slowly since 2006. Dr. Diamond warned that “the decline of democratic efficacy, energy, and self-confidence in the West, including the United States,” was worrisome (Diamond, Citation2015, 142-144). Likewise, Dr. Roberto Foa and Dr. Mounk (2016, 7) argued that citizens in several supposedly consolidated democracies in North America and Western Europe had grown more critical of their political leaders. Furthermore, the citizens had also likely lost a positive attitude toward democracy, were less hopeful and more cynical about their own ability to influence public policy at all, and more willing to express support for authoritarian regimes and leaders.

These scholars and pundits warn that there is a fair reason for concern that “democratic recession,” “democratic backsliding,” or “deconsolidation of democracy” may be gradually advancing around the world. That is to say, in many countries around the world, the formal political institutions and informal political practices that people need to continue to make demands of their governments are diminishing (Frantz, Citation2018, n.p.; Haggard and Kaufman, Citation2021, n.p.).Footnote5 Experts suggest that at any moment it could deepen into and tip over to become something much worse (Diamond, Citation2015, 153; Foa and Mounk, Citation2016; Mounk and Foa, Citation2018).

Whether democracy around the world has been eroding is highly debatable. For instance, Dutch political scientist Dr. Erik Voeten insisted that millennials—much to the surprise among the millennials in the United States—were to some extent in favor of military rule and strong authoritarian leaders to govern their countries; however, he wrote in 2016 that we could not say for sure that overall support for democracy had been eroding (Voeten, Citation2016, 7). Although in 2018, Levitsky and Ziblatt (Citation2018, 205; Sunstein, Citation2018) stated that European democracies face many problems, there was little evidence in any of them of the kind of fundamental erosion in democratic norms is proceeding. In the United States, they claimed democratic norms such as “forbearance” and “mutual tolerance” that had been a seawall of American democracy had wavered for decades. Hence, serious concern about the survival of democracy was raised, even in the United States. Significantly, the 2016 election of Donald Trump challenged the widespread assumption that liberal democracies were robust and unassailable against broad and serious authoritarian challenges (Levitsky and Ziblatt, Citation2018, pp.97-117; Weyland, Citation2020, 389; Haggard and Kaufman, Citation2021, n.p.).

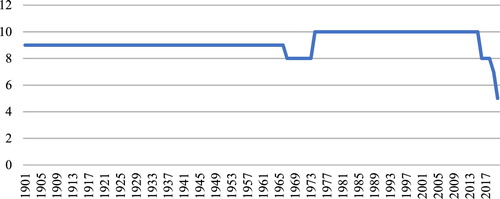

Has American democracy actually weakened? There is much quantitative evidence that should be of great concern. First, Carey et al. (Citation2019, 701) refers to the expert surveys and the public surveys conducted by Bright Line Watch. They show there are steady increases in the quality of US democracy during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although US democracy had scored high in the past several decades, the value had plummeted in the last few years, from 2017 to 2019 (Carey et al., Citation2019, 701). Likewise, as seen in , the Polity Score, which captures the regime authority spectrum on a 21-point scale ranging from -10 (hereditary monarchy) to +10 (consolidated democracy), scored US democracy as 8 in 2016, 2017, and 2018. The score declined to 7 in 2019 and finally to 5 in 2020. The Polity scores can also be converted into regime categories in a suggested three-part categorization of “autocracies” (-10 to -6), “anocracies” (-5 to +5), and “democracies” (+6 to +10).Footnote6 For the first time since 1800, the score of the US fell below 6: the US is now categorized as “anocracy.”

Figure 1 Polity Score of the United States, 1901-2020

Source: Center for Systematic Peace: The Polity Project Homepage.

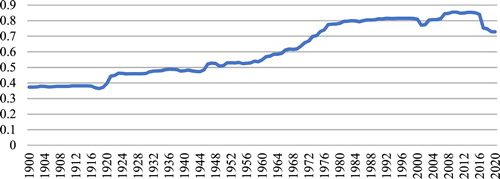

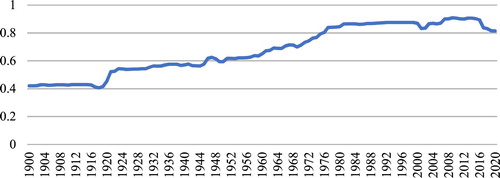

In , the “Liberal Democracy Index” is shown. The index is a measure to analyze the level to which a democracy places importance on protecting individual and minority rights against the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority. shows the “Electoral Democracy Index,” which is an index to see whether a country embodies the core value of making rulers responsive to citizens through electoral competition.Footnote7 We can recognize clear and sudden drops in the two indexes.

Figure 2 Liberal Democracy Index of the United States, 1900-2020

Source: V-Dem Dataset, Version 11.1.

Figure 3 Electoral Democracy Index of the United States, 1900-2020

Source: V-Dem Dataset, Version 11.1.

Furthermore, the watchdog organization Freedom House categorized the United States as “Free” in 2020. However, we find gradual declines in both civil liberties and political rights. Although the United States obtained 92 points in 2015, it was down to 86 points in 2020 (Frantz, Citation2018, n.p.).Footnote8

To put it simply, this quantitative evidence shows there is much concern over the severe decrease in the level of democracy in the United States—although not with a transition to authoritarianism (Frantz, Citation2018 n.p.). Although it is early to tell whether the long-term quality of democracy in the United States will suffer, if it declines even further, the United States’ political regime could move toward a hybrid regime such as “flawed democratic” or “defective democratic” system. As we see in the next section, signs of potential degradation are widespread (Frantz, Citation2018, n.p.; Carey et al. Citation2019, 699).

Causes of democratic deterioration in the United States

Dr. Erica Frantz, specializing in authoritarian politics with a focus on democratization, points out that democratic backsliding is often set in motion by a series of events across multiple domains, such that there is rarely a single event that signifies its occurrence. Instead, as Dr. Frantz points out, “degradations of democracy happen in a number of areas, primarily in terms of the competitiveness of elections, government accountability, and civil and political liberties” (Frantz, Citation2018, n.p.). Regarding this point, according to Dutch political scientist Dr. Cass Mudde, the rise of extremism, authoritarianism, radicalism, and, notably, the surge of populism erodes fundamental values of liberal democracy. Concerning the relationship between populism and democracy in particular, some scholars argue that populism can be hostile to “liberal” democracy. It may not be compatible with liberal institutions, minorities, and reason: it is accompanied by the danger of the “tyranny of the majority.” On the other hand, other scholars argue that populism is not inherently and not always a negative force, or even that populism can be a force of good (Mudde, Citation2018, 1-8; Laclau,Citation2005; Mouffe,Citation2018).

Dr. Kurt Weyland, specializing in democratization and authoritarian rule, shows two conditions necessary for populism to smother democracy: (1) institutional weakness when populists try to challenge democracy, and (2) conjunctural opportunities that help populist leaders to force through the authoritarian way (Weyland, Citation2020, 30). It seems unlikely that the US will ever fully transition to an authoritarian regime from an institutional perspective. That is because institutional factors such as federalism, bicameralism, and separate elections for national office prevent authoritarian leaders from easily and rapidly gaining support. However, an alarm is raised as there have been some events that could possibly become conjunctural opportunities for populist leaders: the gradual erosion of defining features of liberal democratic rule, the protection of political rights and civil liberties, and norms of compromise with opponents may be proceeding to create a conjunctural opportunity for populist leaders to pave the way for authoritarian rule (Kaufman and Haggard, 2018, n.p.; Lee, Citation2020, 371).

Furthermore, as Dr. Frances Lee points out, the two major political parties in the US today are both less resistant to populist attempts to challenge them from within than earlier points in history. Compared to the past, information transmission technology has developed in the US, and political elites and party leaders are unpopular (Lee, Citation2020, 371). Before President Trump was sworn into office, partisans had already become more intransigent than ever because of the extreme level of party polarization, and they have not hesitated to express animus toward their opponents (Iyengar, Citation2016, 219-224). As Levitsky and Ziblatt (Citation2018) claimed, norms that had been a seawall of American democracy had already wavered with the rise of political polarization.

Political polarization has some adverse effects. In a recent book, Dr. Stephan Haggard and Dr. Robert Kaufman (2021, n.p.) indicate that political polarization reduces support for moderate political leaders and organizations and increases the risk of moving toward extremes for existing political parties. In this way, authoritarian anti-system parties gain traction. Dr. Haggard and Dr. Kaufman also claim autocratic leaders and their parties tend to appeal to voters by adopting radical agendas, and they try to make most of the polarization to gain executive office and legislative majorities. Therefore, the autocrat’s electoral victory to form a majority in Congress constitutes an institutional foundation for democratic backsliding (Haggard and Kaufman, Citation2021, n.p.).

The American party system has undergone significant changes since the mid-1960s, racially, culturally, and ideologically. When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, conservative whites in the Southern states, who disliked the legislation, began to switch to support the Democratic Party. Additionally, in the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan successfully attracted politically awakened religious conservatives to the Republican Party by appealing to Christianity and traditional family values. As Dr. Alan Abramowitz and Dr. Jennifer McCoy illustrated in their article, it was in the 1970s and 1980s that these voters began to change. This change was the starting point for an even more ideologically cohesive American electorate in the 1990s and 2000s. The ideological divergence of voters was reflected in the major political parties through elections, with the Republican Party becoming more conservative and the Democratic Party becoming more liberal. The moderates disappeared from both parties, and the parties no longer compromised on policy and ideology (Abramowitz and McCoy, Citation2019, 138).

For many years, political scientists understood polarization as an increase in the distance between political parties over ideology. In recent years, however, polarization is understood as not exclusively over only ideology or policy (Finkel et al., Citation2020, 533). Finkel et al. named this non-ideological type of polarization “political sectarianism” and other scholars sometimes synonymously labeled it “political tribalism” or “affective polarization” (Chua, Citation2018; Abramowitz and McCoy, Citation2019). There are three important features of “political sectarianism:”

“othering—the tendency to view opposing partisans as essentially different or alien to oneself; aversion—the tendency to dislike and distrust opposing partisans; and moralization—the tendency to view opposing partisans as iniquitous (Finkel et al., Citation2020, 533).”

These three characteristics—“othering,” “aversion,” and “moralization”—are the key components of “negative partisanship.” People do not support their political parties because they value ideology or policy principles. They support their party based upon their social identity: their political sophistication is considered to be low. Likewise, there is no apparent reason for them to dislike the other party. They reject opponents whose identity is different from their own. Most troubling of all, it has been pointed out that as political sectarianism progresses, electoral candidates try to appeal to voters by using anti-democratic tactics (Finkel et al., Citation2020, 533, 535; Egan, Citation2020, 701-702).

When Barack Obama won the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, those concerned about rapid demographic change in the US society—whites, evangelicals, and conservatives—began to feel that they needed to take action. In the 2016 presidential election, Trump’s message is believed to have resonated with these people. Hence, those who supported Trump and the Republican Party were no longer motivated by ideology but by race, gender, and other identities (Sides et al., Citation2018). According to Dr. Abramowitz and Dr. McCoy, Trump's campaign rhetoric was polarizing and demonizing toward his adversaries; “dividing the country between ‘Us'-the ‘real' Americans who hungered for a return to an idealized past when industrial jobs provided for upward mobility and white males were in charge in the workplace and the family, and ‘Them'-the immigrants, minorities, and liberal elites who had wrought an ‘American carnage’” (Abramowitz and McCoy, Citation2019, 138-139).

The anger, anxiety, and opposition of the white working class, which felt threatened by Obama’s electoral victories, was exploited to advance Trump. In a sense, the ongoing ideological polarization and political sectarianism laid the groundwork for Trump’s populist message to resonate more easily with his supporters and activated a broader “identity crisis” especially among disadvantaged white voters (Abramowitz and McCoy, Citation2019, 139; Sides et al., Citation2018).

Now the Republican Party has become the party that embodies white, Christian, conservative, and heterosexual identities, while the Democratic Party has increasingly become the party that represents the identities of sexual, racial, and religious minorities. The two political parties are at odds over identity and refuse to make a compromise. Social sorting is evident at both mass and elite levels, paving the way for Americans to receive populist messages that appeal to their identity (Egan, Citation2020, 700). Furthermore, three components of “negative partisanship”—othering, aversion, and moralization—have been worsening. Democrats and Republicans both say the other party’s members are hypocritical, selfish, close-minded, and incompatible. They are unwilling to work, marry, date, conduct business with, and even to partner with opponents in a variety of activities (Iyengar et al., Citation2019, 130; Egan, Citation2020, 702). For instance, studies have shown that neither Republicans nor Democrats want to live near people who are politically different. Many voters live with virtually no exposure to voters from the other party in their residential environment: as Brown and Enos write in the article, geographic segregation does exist (Brown and Enos, Citation2021, 1-2). In 1960, only 4% to 5% were upset when their children married someone from the opposite party. However, now one-third of Democrats and one-half of Republicans feel uncomfortable if a family member marries someone of the other party (Iyengar et al, 2019, 132). Many Republicans and Democrats are convinced that the other party is making America miserable. Nowadays, Democrats and Republicans rarely switch their party support, and it has become also rare for them to vote for any candidate on the ballots other than those running for office from their party (Dost, et al., Citation2019, 1-2).

As confirmed in this section, two influential trends—political sectarianism and the rise of negative partisanship—affecting the American electorate contributed to give the populist leader (i.e., Donald Trump) overwhelming support for projects that deteriorated the quality of American democracy (Abramowitz and McCoy, Citation2019, 140). In short, political sectarianism and negative partisanship functioned as conjunctural opportunities. As Gary Jacobson indicates in his article, after Trump was sworn in as president, he continuously contributed to worsening negative partisanship as shown in the results of multiple surveys (Jacobson, Citation2020, 769). In the next section, how Trump made the most of conjunctural opportunities and disrupted democracy in the US is verified.

The Trump presidency and democracy in the United States

As McCoy and Somer point out, polarization serves either a constructive or destructive purpose for democracy. Polarization can clarify the ideological differences between the political parties and hence offer a clear choice to the voters. In a manner of speaking, parties with apparent ideological differences will seek to realize their policies as responsible parties after winning elections and try to keep their promises to their supporters. Therefore, polarization can serve as heuristics and can be expected to increase the democratic responsiveness of political parties (McCoy and Somer, Citation2019, 235). On the other hand, the worst consequence of polarization, especially political sectarianism, for American democracy is that the rise of negative partisanship will prevent political consensus and beneficial compromise from being formed. It can be a severe threat to American democracy (Somer and McCoy, Citation2019, 9). In short, as Dr. McCoy and Dr. Murat Somer point out “whether polarization serves a constructive or destructive purpose for democracy depends on the behavior of both incumbents and oppositions, new political actors and traditionally dominant groups (McCoy and Somer, Citation2019, 235).”

What about Donald Trump? Unfortunately, Trump’s presidency worsened the situation rather than fixing it, since the president exhibited many authoritarian-like traits. He stoked underlying ethnic divisions in supporting xenophobic immigration policies, misogyny, white supremacy, and demonization and delegitimization of his opponents as “Crooked Hillary,” “Lyin’ Ted,” “Little Marco,” “Pocahontas,” “low-energy Jeb,” for example. Trump labeled those who did not do his bidding and those who opposed him traitors. Among those were Rex Tillerson, Herbert McMaster, Adam Schiff, James Comey, Andrew McCabe, and Brad Raffensperger (Pfiffner, Citation2021, 97-98). Trump is also well-known for his relentless attacks on the media as “enemies of the people” and “fake media.” He seemed to weaken the protection of civil and political liberties and challenged the independence of the courts and the federal law enforcement organizations and intelligence apparatus. In addition, Trump openly questioned the validity of the electoral results and showed his disregard for scientific knowledge and reported facts (Lieberman et al., Citation2018, 470-479; Kaufman and Haggard, 2018, n.p.; Bermeo, Citation2019, 229-230).

Furthermore, Trump’s populist rhetoric extended to trade, security, and diplomacy, where bipartisan agreement had been maintained until recently. The administration was so nationalistic and protectionist (“America First”) that it renounced free trade and climate agreements and imposed tariffs on a broad array of imported goods (Boucher and Thies, Citation2019, 712). Although the Trump administration had been skeptical of its allies, it did not bother to hide its praise for authoritarian leaders such as Vladimir Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdog˘an, Xí Jìnpíng, and Kim Jong-un (Pfiffner, Citation2018, 154; Boucher and Thies, Citation2019, 712).

Dr. James Pfiffner, professor of public policy, pointed out that Trump’s lies differed significantly from those of previous presidents. Some of his lies were insignificant, trivial, and mere braggadocio. However, Dr. Pfiffner claimed some of his lies were consequential such as that Muslims in New Jersey celebrated the 911 attack, Obama created ISIS, or his baseless claims on COVID-19. Dr. Pffiner also wrote that Trump had degraded political discourse by piling on the lies and distorting the facts, which are common characteristics of many authoritarian leaders. According to Pffiner, Trump's assertion that there is not always one reality and that there can be “alternative facts” undermined democracy. Many people had no way of ascertaining whether his claims were true or false (Pffiner, 2021, 100-102).

A spike in hate crimes and online harassment targeting minorities followed Donald Trump’s election. Whether Trump’s actions caused the hate crimes and the harassment is still debatable. However, Dr. Marco Giani and Dr. Pierre-Guillaume Meon (2019, 1) suggest that the increase in hate crimes and harassment may reflect a change in social norms. In the United States, after the election of Obama, attitudinal trends in support of racial equality led to widespread optimism about the future of race relations and even the arrival of a post-racial society. However, Donald Trump’s victory might indicate that social norms shifted toward accepting public displays of racist attitudes.

Trump’s tweets lacked civility and moderation. Some hints are gained from an article by Dr. Allyson Benton and Dr. Andrew Phillips (2019). According to the article, Trump’s tweets on Mexico-related policy and the U.S. dollar-Mexican peso caused fluctuations in the exchange rate: investors used Trump’s tweets as “heuristics” when his actual policy stance was unknown. Tweets made by Trump mattered (Benton and Philips, Citation2019, 169-190). It is unclear whether this insight might apply to other controversial tweets, especially those related to racial and gender discrimination or white supremacy. However, before making a causal inference between his tweets and his supporters’ discrimination or white supremacy, above anything else, we can fairly say it is morally inappropriate for a US president to namecall and belittle opponents, or, even worse, to call on protesters via Twitter to march toward the Capitol.

Months after Joe Biden won the 2020 election, Trump still had not conceded loss. Even worse, with Trump’s repeated claims alleging voter fraud in the 2020 election and doubt of electoral meddling by Russia, Americans now face a severe crisis of faith in the electoral process. If voters' confidence in the fairness of elections in their own country is shaken, the stability of the democratic system will be severely undermined in the long run. Only when the people have unwavering faith in the electoral system can their trust in the entire democratic system of the country—including the judicial, the administrative, and the legislative branches—be solidified (Daniller and Mutz, Citation2019, 46).

Dr. Andrew Daniller and Dr. Diana Mutz point out that “Americans' degrees of concern about allegations of voter fraud are closely tied to the perceived effects of the alleged fraud on a preferred candidate's chances of winning” (Daniller and Mutz, Citation2019, 47). That is to say, the side that has lost the election is prone to conspiratorial thinking, such as that the winning side may have committed fraud or that the election results may be wrong. Researchers from a university consortium of Northwestern, Harvard, Northeastern, and Rutgers surveyed more than 24,000 individuals across the country between November 3 and November 30, 2020. They found that 38% of all Americans lacked confidence in the fairness of the 2020 presidential election. However, 64% of Republicans had doubts about the 2020 presidential election, and the number went up to 69% among Trump supporters. On the other hand, only 11% of Democrats and 8% of Biden supporters were skeptical about the result of the presidential election.Footnote9

Are Republicans more vulnerable to populist messages? Probably not. Dr. Ariel Malka et al. presented two key findings related to “green light” authoritarian actions within the consolidated Western democracies. First, it is pointed out that those with culturally conservative orientation are more likely to be open to authoritarian governance. Dr. Malka et al. illustrate those who value traditional gender roles and religion and those who dislike immigrants from abroad as examples. For conservatives, authoritarian governance may be perceived as an effective means of restoring traditional social order, maintaining religious values, and countering the trends of an increasingly diverse society. Second, it is suggested that those who support leftist economic policies are also more likely to support authoritarian regimes. Malka et al. concluded that the combination of right-wing cultural and left-wing economic attitudes correlates with the high degree of acceptance people show toward authoritarian regimes in English-speaking countries, including the United States (Malka et al., Citation2020, 2-15).

In the United States, the combination of right-wing cultural attitudes and support for left-wing economic policies remains rare. The majority of Republican supporters consist of pro-business “Core Conservatives” or anti-immigration and anti-global “County First Conservatives.”Footnote10 Republicans’ support for left-wing economic policies such as health care, increasing affordability of college education, and solutions to economic inequality is low. If anything, the majority of the Republicans are still the staunch supporters for smaller government, lower taxes, and deregulations.Footnote11 This twist of attitude and policy support among Republicans might prevent them from increasing support for authoritarian governance.

However, we should discuss carefully whether Trump and Trumpism have transformed Republican Party ideology and conservatism. If so, in what way did he help to redefine the party and conservatism? How far have the GOP supporters sympathized with the Trump presidency in embracing the new ways of thinking and acting? Trump continued to use traditional Republican rhetoric such as deregulation and tax cuts; however, in many ways, such as free trade, immigration, government spending (e.g., infrastructure spending), and even government intervention (e.g., entitlement spending reform), Trump’s rhetoric was different from traditional Republican ideology (Lewis, Citation2019, 1-2). If the Republican Party will discard the old rhetoric and embrace and use more new discourses and narratives posed by Trump, the combination of a right-wing cultural attitude and support for left-wing economic policies will prevail. If that happens, the GOP will likely be more vulnerable to leaders who send populist messages (Lewis, Citation2019, 1-2).

It is noteworthy that voters who voted for Trump in the 2016 election switched to support the Democratic Party in the 2018 midterm elections partly because of the increasing sexism and racism tendencies and appeals made by Trump and his supporters. The Republican Party has been given a penalty for engaging in sexism and racism in 2018 and perhaps in 2020 as well. Trump’s unconventional rhetoric might have changed the party’s brand. However, if the electoral penalty for adopting Trumpism continues, that will make the Republicans rethink the (dis)advantage of embracing Trumpism (Schaffner, Citation2020, 1-9).

Discussion and conclusion

The following three results are identified:

1: As the quantitative evidence shows in the first section of this article, democracy in the US has been deteriorating.

2: There could be some possible causes for the deteriorating of American democracy. In particular, conjunctural opportunities give populist leaders an opening to project authoritarian schemes in the US against the backdrop of political sectarianism and the rise of negative partisanship.

3: The presidency of Donald Trump could be regarded as a cause of degradation of American democracy. Many of his traits and actions were damaging to American democracy. However, because Trumpism has not thoroughly permeated the Republican party, a barrier exists against further deterioration or even a transition to authoritarianism. Finally, what should be done to prevent American democracy from further deterioration? As political polarization is the most significant cause of the democratic decline in the US, we should think about repairing interparty antagonism and reaching an agreement. As the author claimed in a previous article, both parties have to endeavor to create variety of opinion within each party and find ways to enhance interparty trust (Ishii et al., Citation2021, 1-9). The author will discuss this in detail in a future study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Alizada, N., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Cornell, A., Fish, M. S., Gastaldi, L., Gjerløw, H., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Hindle, G., Ilchenko, N., Krusell, J., Luhrmann, A., Maerz, S. F., Marquardt, K. L., McMann, K., Mechkova, V., Medzihorsky, J., Paxton, P., Pemstein, D., Pernes, J., von Römer, J., Seim, B., Sigman, R., Skaaning, S., Staton, J., Sundström, A., Tzelgov, E., Wang, Y., Wig, T., Wilson, S., and Ziblatt, D. 2021. “V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v11” Varieties of Democracy Project at https://doi.org/10.23696/vdems21. Another data that supports the findings of this study are openly available in Center for System Peace: INSCR Data Page at https://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nishikawa Masaru

Nishikawa Masaru is a professor in the Department of International and Cultural Studies at Tsuda University. His research focus is Computational Social Science, US-Japan relations, comparative politics, and American politics. He has published three books in Japanese. He also published several articles in Diplomatic History, Party Politics, PS: Political Science & Politics, and Frontiers in Physics. He has given various academic presentations at OAH, APSA, MPSA, SHAFR, and many others. He is also a frequent contributor to Japanese media, including Mainichi Shimbun and Nikkei Shimbun newspapers. He earned a Ph.D. from Keio University in 2007. Before joining Tsuda University, he was a Fulbright Scholar at Temple University and then a research fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, a private non-partisan think tank focused on foreign affairs and security issues.

Notes

1 Alex Woodward, “QAnon-linked congresswoman-elect Marjorie Taylor Greene joins effort to reject electoral college votes.” Independent. December 19, 2020. Accessed March 11, 2021. <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/marjorie-taylor-greene-electoral-college-b1776445.html>

2 “Marjorie Taylor Greene: U.S. House votes to strip Republican of key posts.” BBC. February 5, 2021. Accessed March 11, 2021. <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-55940542>

3 Adam Taylor, “Trump's ‘stop the steal’ message finds an international audience among conspiracy theorists and suspected cults.” The Washington Post. January 8, 2021. Accessed March 2, 2021. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/01/07/trump-qanon-stop-the-steal-japan/>

4 For example, “Trump-shi, Beikoku-no-Minshushugi-ni-Kizu. ‘Bouryoku Younin’ Miekakure.” Asahi Shimbun, January 14, 2021. Accessed March 21. <https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASP1G6VTJP1GUHBI01F.html>; “Trump-ha-no-Gikai-Rannyu Minshu-Taikoku-no-Rekishiteki-Oten da.” Mainichi Shimbun, January 8, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. <https://mainichi.jp/articles/20210108/ddm/005/070/098000c>; “Minshushugi-ha-Yomigaeruka Kienu-Trump-no-Zanzo.” Nihon Keizai Shimbun, January 21, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. <https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOGN19C0T0Z10C21A1000000/>; “Beigijidou-Senkyo Minshushugi-no-Sendouyaku-no-Na-ga-Naku.” Yomiuri Shimbun, January 9, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. <https://www.yomiuri.co.jp/editorial/20210108-OYT1T50240/>; “Be-gikai he-Rannyu Minshushugi-no-Ookina-Oten-da.” Sankei Shimbun, January 9, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. <https://www.sankei.com/column/news/210109/clm2101090001-n1.html>

5 The author referred to Frantz (Citation2018) and Haggard and Kaufman (Citation2021). However, in the Kindle format purchased by the author the page number was not indicated.

6 Three categorizations and data were downloaded and quoted from: Center for systematic Peace: The Polity Project Homepage. <https://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html>

7 The author downloaded data and quoted explanations on the variables from V-Dem. For more details on clarifications of the variables, please download and refer to V-Dem Codebook. Accessed March 13, 2021. <https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/data/v-dem-dataset-v11/>

8 The author checked the values for the U.S. by looking into Freedom House: Countries and Territories. Accessed February 25, 2021. <https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores>

9 Stephanie Kulke, “38% of Americans lack confidence in election fairness.” Northwestern Now. December 23, 2020. Accessed March 1, 2021. <https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2020/12/38-of-americans-lack-confidence-in-election-fairness/>

10 “Political Typology Reveals Deep Fissures on the Right and Left.” Pew Research Center. October 24, 2017. Accessed March 1, 2021. <https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/10/24/political-typology-reveals-deep-fissures-on-the-right-and-left/>

11 “In a Politically Polarized Era, Sharp Divides in Both Partisan Coalitions.” Pew Research Center. October 17, 2019. Accessed March 1, 2021. <https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/12/17/views-of-the-major-problems-facing-the-country/> There are small numbers of Republican supporters that be called “Market Skeptic Republicans.” See, “Political Typology Reveals Deep Fissures on the Right and Left.” Pew Research Center. October 24, 2017. Accessed March 1, 2021. <https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/10/24/political-typology-reveals-deep-fissures-on-the-right-and-left/>

References

- Abramowitz, A., and McCoy, J. (2019) United States: Racial Statement, Negative Partisanship, and Polarization in Trump’s America. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political Science and Social Science, 681 (1), 137-156. doi.org/10.1177/0002716218811309

- Benton, A. L., and Philips, A.Q. (2019) Does the @realDonaldTrump Really Matter to Financial Markets? American Journal of Political Science, 64 (1), 169-190. doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12491

- Bermeo, N. (2019) Reflections: Can American Democracy Still be Saved? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political Science and Social Science, 681 (1), 228-233. doi.org/10.1177/0002716218818083

- Boucher, J., and Thies, C.G. (2019) I Am a Tariff Man”: The Power of Populist Foreign Policy Rhetoric under President Trump. The Journal of Politics, 81 (2), 712-722. doi.org/10.1086/702229

- Brown, J. R., and Enos, R. D. (2021) The measurement of partisan sorting for 180 million voters. Nature Human Behavior, Online First. doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01066-z

- Carey, J. M., Helmke, G., Nyhan, B., Sanders, M., and Stokes, S. (2019) Searching for Bright Lines in the Trump Presidency. Perspectives on Politics, 17 (3), 699-718. doi.org/10.1017/S153759271900001X

- Chua, A. (2018) Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations, Penguin Books.

- Daniller, A. M., and Mutz, D.C. (2019) The Dynamics of Electoral Integrity: A Three-Election Panel Study. Public Opinion Quarterly, 83 (1), 46-67. doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz002

- Diamond, L. (2015) Facing Up to the Democratic Recession. Journal of Democracy, 26 (1), 141-155. DOI: 10.1353/jod.2015.0009

- Dost, M., Enos, R., and Hochschild, J. (2019) Loyalists and Switchers: Characterizing Voters’ Responses to Donald Trump’s Campaign and Presidency. Political Science Quarterly, 1-23. doi.org/10.1002/polq.13130

- Egan, P. J. (2020) Identity as Dependent Variable: How Americans Shift Their Identities to Align with Their Politics. American Journal of Political Science, 64 (3), 699-716. doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12496

- Finkel, E. J., Bail, C.A., Cikara, M., Ditto, P.H., Iyengar, S., Klar, S., Mason, L., McGrath, M. C., Nyhan, B., Rand, D. G., Skitka, L. J., Tucker, J. A., Van Bavel, J. J., Wang, C. S., and Druckman, J. N. (2020) Political Sectarianism in America. Science, 370 (6516), 533-536. DOI: 10.1126/science.abe1715

- Foa, R., and Mounk, Y. (2016) The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect. Journal of Democracy, 27 (3), 5-17. DOI: 10.1353/jod.2016.0049

- Frantz, E. (2018) Authoritarianism: What Everyone Needs to Know (Kindle Edition). Oxford University Press.

- Giani, M., and Meon, P. (2019) Global Racist Contagion Following Donald Trump’s Election. British Journal of Political Science, Online First, 1-8. doi:10.1017/S0007123419000449

- Haggard, S., and Kaufman, R. (2021) Backsliding (Kindle Edition). Cambridge University Press.

- Ishii, A., Okano, N., and Nishikawa, M. (2021) Social Simulation of Intergroup Conflicts Using a New Model of Opinion Dynamics. Frontiers in Physics, 9: 640925, 1-9. doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2021.640925

- Iyengar, S. (2016) E Pluribus Pluribus, or Divided We Stand. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80 (S1), 219–224. doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfv084

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood. S. J. (2019) The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22 (1), 129-146. doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

- Jacobson, G. C. (2020) Donald Trump and the Parties: Impeachment, Pandemic, Protest, and Electoral Politics in 2020. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 50 (4), 762-795. doi.org/10.1111/psq.12682

- Laclau, E. (2005) On Populist Reason, Verso.

- Lee, F. E. (2020) Populism and the American Party System: Opportunities and Constraints. Perspectives on Politics, 18 (2), 370–388. doi:10.1017/S1537592719002664

- Levitsky, S., and Ziblatt, D. (2018) How Democracies Die, Crown.

- Lewis, V. (2019) The problem of Donald Trump and the Static Spectrum Fallacy. Party Politics, Online First, 1-14. doi:10.1177/1354068819871673

- Lieberman, R. C., Mettler, S., Pepinsky, T. B., Roberts, K. M., and Valelly, R. (2018) The Trump Presidency and American Democracy: A Historical and Comparative Analysis. Perspectives on Politics, 17 (2), 470-479. doi:10.1017/S1537592718003286

- Malka, A., Lelkes, Y., Bakker, B. N., and Spivack, E. (2020) Who is Open to Authoritarian Governance within Western Democracies? Perspectives on Politics, Online First, 1-20. doi:10.1017/S1537592720002091

- McCoy J., and Somer, M. (2019) Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms Democracies: Comparative Evidence and Possible Remedies. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681 (1), 234-271. doi.org/10.1177%2F0002716218818782

- Mouffe, C. (2018) For a Left Populism, Verso.

- Mounk, Y., and Foa, R. S. (2018) The End of the Democratic Century: Autocracy’s Global Ascendance. Foreign Affairs, 97 (3), 29-36.

- Mounk, Y. (2021) Democracy on the Defense. Foreign Affairs, March/April 2021, 163-171.

- Mudde, C. (2018) The Far Right in America, Routledge.

- Nishikawa, M. (2020) LEARN MORE BEFORE WE MAKE ASSERTIONS: TEACHING AMERICAN POLITICS IN JAPAN. PS: Political Science & Politics, 53 (2), 359-360. doi:10.1017/S1049096519001987

- Pfiffner, J. P. (2018) The Contemporary Presidency: Organizing the Trump Presidency. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 48 (1), 153-167. doi.org/10.1111/psq.12446

- Pfiffner, J. P. (2021) Donald Trump and the Norms of the Presidency. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 51 (1), 96-124. doi.org/10.1111/psq.12698

- Power, S. (2021) The Can-Do Power: America’s Advantage and Biden’s Chance. Foreign Affairs, January/February 2021, 12-24.

- Sawhill, I. (2021) How Biden Can Rebuild a Divided and Distrustful Nation: Americans Must Get to Know One Another Again.” Foreign Affairs, Online Version (January 4, 2021). <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/how-biden-can-rebuild-divided-and-distrustful-nation>, accessed March 11, 2021.

- Schaffner, B. (2020) The Heightened Importance of Racism and Sexism in the 2018 US Midterm Elections. British Journal of Political Science, Online First, 1-9. doi:10.1017/S0007123420000319

- Sides, J., Tesler, M., and Vavreck, L. (2018) Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America, Princeton University Press.

- Somer, M., and McCoy, J. (2019) Transformations through Polarizations and Global Threats to Democracy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681 (1), 8-22. doi.org/10.1177%2F0002716218818058

- Sunstein, C. (2018) Can It Happen Here? Authoritarianism in America, Dey Street Books.

- Voeten, E. (2016) Are People Really Turning Away from Democracy? A Paper Available at SSRN. doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2882878

- Weyland, K. (2020) Populism’s Threat to Democracy: Comparative Lessons for the United States. Perspectives on Politics, 18 (2), 389-406. doi:10.1017/S1537592719003955