ABSTRACT

In order to understand the land use characteristics of the rail transit station sites in new towns of high-density Asian city, this study selected six rail transit stations in Singapore as the research objects. Through the GIS spatial analysis, the study analyzes the rail transit sites in the new town centers and private residential areas, as well as the similarities and differences between Urban TODs and Neighborhood TODs, with consideration to two spatial structure forms of Singapore’s new towns. The study finds out that the rail transit station sites in Singapore’s new town centers have gradually formed a specific TOD land use model for Asian transit village. The urban center hierarchy and the new town development concept have led to the difference in land use characteristics of the TOD stations. It is suggested that the mixed-use development of the TOD station area should be tailored to local conditions and a certain proportion of public service facilities, parks and open spaces should be guaranteed, to achieve sustainable development of land economy, environment and society.

1. Introduction

1.1 Literature review

In 1990s, the automobile-oriented urban development resulted in urban sprawl, traffic congestion, decline of inner city, and other urban problems in the US New Urbanism, which advocates compact, diversified, and mixed-use development of land, arose. Peter Calthorpe, a representative New Urbanist, proposed transit-oriented development as early as 1993, a planning concept entirely different from the conventional sprawl development. In The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, community, and the American dream, he laid down detailed and specific planning criteria for TOD and divided TOD into neighborhood TOD and urban TOD (Calthorpe Citation1993).

TOD concept has been widely promoted and practiced from 1990s. Its definitions vary, however, as urban planners and transportation planners have different understanding of TOD. Bernick and Cervero (Citation1997) define TOD as a compact and mixed-use neighborhood arranged around a transit station site, which, together with the surrounding public space, is the center of the neighborhood. The transit station site serves as a transportation hub connecting the neighborhood with other areas, while the public space is an important activity and meeting place of the area. Still (Citation2002) believes that TOD represents a mixed-purpose neighborhood which encourages people to live near transit services to cut automobile dependence. Maryland Transit Administration defines TOD as the design principle of denser neighborhood that includes a mix of residence, employment, commercial, and public services, with a large bus or rail transit station within a walkable range. Walking and biking are preferred and the neighborhood is accessible by automobiles (Maryland Department of Transportation Citation2000; Ma Citation2003). Though the said definitions diverse in perspectives, they all stress on mixed-use land development, proximity of transit services, and favor of transit development (Cervero, Ferrell, and Murphy Citation2002).

Studies on TOD theory are concentrated on the following aspects. At the macro level, some scholars view TOD as a concept of urban development and structure layout around the transport corridor. They advocate healthy and sustainable development of urban spatial structure through synergy of transport planning and land use. Renne (Citation2009) analyzed the region-scale TOD planning in Perth, Australia. This “Network City” regional planning integrates three spatial elements, transport corridor, activity corridor, and activity center. Researchers analyzed the experience in synergy of public transit and land development and how to reshape urban landscape through transit development, including possible challenges in the course and countermeasures (Suzuki, Cervero, and Iuchi Citation2013). At the meso level, TOD specifically refers to the development oriented to public transit services. It is a general description of a pattern of land development and construction around a transit station site as well as the form of neighborhood developed under this pattern. Calthorpe has given recommendations for land use proportion of Urban and Neighborhood TOD sites (). Although both types of TODs recommend the development of mixed land use, they have different use emphases. Urban TODs are encouraged for development of larger commercial core areas and office space, while Neighborhood TODs emphasize a higher proportion of residential development based on the necessary commercial core areas (Calthorpe and Associates Citation1990).

Figure 1. Recommendations for land use proportion of urban and neighborhood TOD sites by Calthorpe

(source: Calthorpe Citation1990 “Transit oriented development design guidelines.” Calthorpe association).

On this basis, different regions have carried out localized transit-oriented development strategy based on their own development characteristics, including the proposed classification of TODs, the definition of different types of TOD, and the recommendations for development density. Most of these studies are conducted in cities in the United States according to the development situation and social background of each city (Community Design + Architecture Citation2001).Take Florida, US for example. Its TOD station sites are divided into three levels. Each has its own planning and design guide (Florida Department of Transportation Citation2012). Jacobson and Forsyth (Citation2008) analyzed seven TOD projects in the US from the angle of urban design. They proposed 12 principles for a successful TOD design from the perspectives of development process, location, and facilities. However, related research on high-density cities in Asia is still relatively lacking. Due to the difference between urban development background and urban density with the cities in United States, the research on TOD in Asian cities, especially those related to land use characteristics, demand more empirical studies to enrichment.

Studies on the built environment of TOD are research hotspot in recent years, focusing on the relationship between the characteristics of built environment and public transit travel and non-motorized travel behaviors of the residents. A number of studies have proved that the built environment have influence on the residents’ travel choice (Kockelman Citation1997; Zhang Citation2004). A case study of Vancouver showed that residents living in the top 25% most walkable neighborhoods walk or take public transit two to three times more than those living in the least walkable neighborhoods, cutting the use of private automobiles by 58% (Frank Citation2010). Ewing and Cervero (Citation2010) updated earlier researches, they analyzed over 200 studies on built environment over the decade, using meta-analysis to summarize empirical results on associations between the built environment and travel.

In short, the majority of the literature on TOD studies has focused on transport planning, geological economy, and macro policies. Most of these empirical studies are conducted in the developed world and particularly the United States. Empirical research on TOD in Asian cities is scarce. In recent years, several studies begin to focus on TOD in combination with urban design approach but not adequate. There is relatively insufficient research on the comparison of sites with different TOD types from the aspect of land use. For these reasons, with rail transit station sites in Singapore’s new towns as the study object, this paper empirically analyzes the land use characteristics of different station areas, in an attempt to fill a gap in the study on TOD in Asian cities.

1.2 History of integrated land use and transport in Singapore

Singapore stands out in sustainable transport planning and ecological city construction among Asian cities. Cervero (Citation1998) listed Singapore one of the representative Asian transit metropolises and referred to it as a “Sustainable Transit Metropolis” in The Transit Metropolis: A global inquiry. In addition, the sustainable transport policy and planning concept of Singapore are recognized by Newman and Kenworthy (Citation1999), Schwaab and Thielmann (Citation2002), and many other scholars.

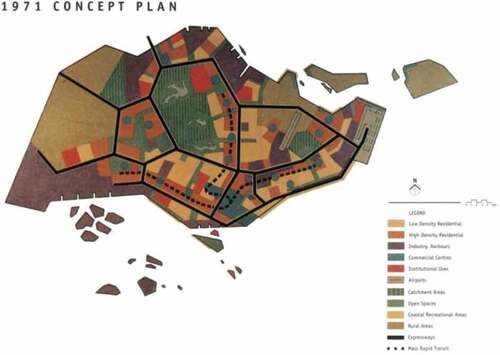

The compact and ecological urban environment of Singapore nowadays is inseparable from its integrated land use and transport planning. In a review of urban construction of Singapore, with its economic boom in 1960s and 1970s, vehicle population doubled. In early 1970s, a half of Singapore population travelled by car, seriously congesting the traffic. The living environment was less favorable as large parking space provided for one-third of public housing developments occupied a large area of public space (Yang and Lew Citation2009). In 1971, Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) proposed the first Concept Plan, laying foundation for the entire spatial structure of the city today (). According to the Plan, a belt-shaped urban morphology with the downtown and natural reserves in the center is formed, defining a pattern of connecting new towns with Mass Rapid Transit (MRT). In the meantime, Housing and Development Board (HDB), dedicated to the goal of “home ownership for every people”, vigorously developed low-price public housing to guide and improve living environment of the city. HDB planned and built flats in new towns, a derivative of satellite city. They were also furnished with complete living service facilities, including shopping centers, schools, and parks (Barter Citation2008).

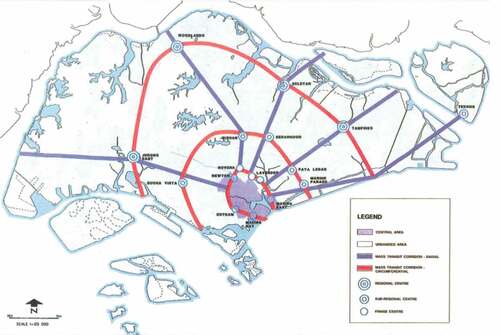

The construction (starting in 1983) of the East-West and North-South MRT lines after a vigorous debate among policy-makers on whether it was justified over an upgraded bus system was a significant transport development (Barter and Dotson Citation2013). In 1991, the URA released the revised Concept Plan which was the continuation of the Concept Plan 1971. On the basis of the “ring” form, five radial “corridors” are added to strengthen shaping the urban form of constellation (Constellation Plan) (). The commercial centers are classified into town center, fringe center, sub-regional center, and regional center (URA Citation1991). They are distributed along rail transit to achieve a balance of occupation and residence. The aim is to further evacuate the population to reduce congestion in the city center. Today, the Tampines Regional Centre is a successful example of the implementation of the 1991 Concept Plan and has become a central location for shopping and leisure activities in the Eastern region. Afterwards, new towns are developed and constructed in order under the leadership of government along the MRT corridor, exhibiting the typical characteristics of TOD pattern, where residential buildings adjacent to the town center mainly are HDB flats. In other word, compact transit villages are built in new towns, which are interconnected by mass rapid transit. The new town development pattern of Singapore is quite similar to the transit metropolis model proposed by Cervero (Citation1998). Unlike the U.S. where TOD develops from theory to practice, TOD theory is developed through practice in Singapore. TOD model is practiced in Singapore earlier than the rise of TOD theory in the west. It is an option for high-density Asian cities to tackle urban problems under the condition of limited land resource in the process of urbanization.

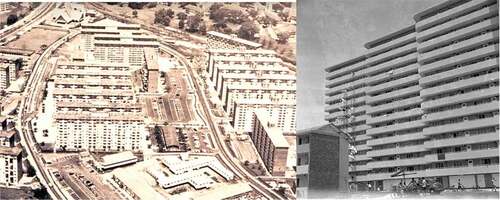

Queenstown is a first-generation new town built from 1952 to 1968 at the edge of city center. It was built in order to improve living conditions, but was not combined with public transit station. Comfortableness and walkability of the living environment were not considered in its layout. As a result, its spatial form was similar to Le Corbusier’s Marseille apartment, a modernist collective residence characterized by “living machine”. This slab-type apartment represents an “automobile priority” planning form as most of its public space was used as ground parking space and it lacked systematic planning of pedestrian environment and landscaping ().

Figure 4. Layout and public housing form of queenstown in 1960s

(Source: national archives of Singapore).

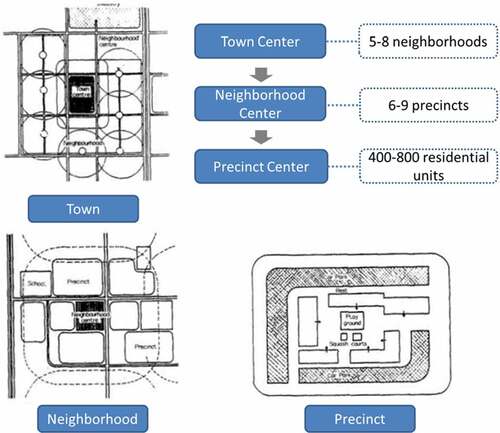

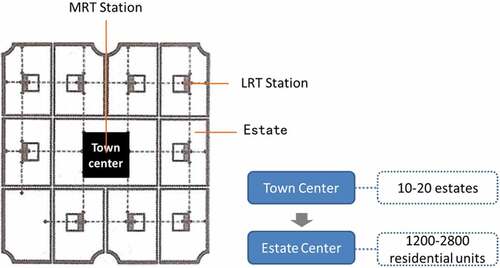

After Queenstown, Singapore intentionally integrated rail transit development into new town planning and design from the beginning. The land use form and transport system matched up and supported each other. Their spatial structure evolved with the time. Toa Payoh is the first new town which intentionally integrates the public transit infrastructure with commercial facilities and has a hierarchical neighborhood spatial structure. Tampines features a clear three-level structure of “Town-Neighborhood-Precinct”. Laying more emphasis on public space and green open space, it becomes a model for future new towns development. Punggol, as a new town of the latest generation, inherits the idea of green urbanism and is more oriented to sustainability and ecology. The two-level structure of “Town-Estate” is formed as Mass Rail Transit (MRT) and Light Rail Transit (LRT) systems are combined, realizing a more compact layout.

2. Purpose and object of study

The author selects several rail transit station areas in Singapore for the empirical study on the land use characteristics and development pattern of TOD station area in new towns of Singapore at the meso level. The following two questions are explored for the study: what are the differences between TOD station sites and non-TOD station sites in land use characteristics? How to interpret the land use characteristics of the TOD station sites located in different new towns? The scope of research will focus on the MRT stations area within a 500-meter radius from the center, which is a suitable distance according to previous researches (Cervero and Murakami Citation2009; Li, Lin, and Hsieh Citation2016).

The author selects seven typical station areas from 23 HDB towns and three estates in Singapore as the study objects. Five of them are seated in the center of towns built in different years (). They are representative TOD station sites; and the rest two, located in Bukit Timah, are non-TOD station sites. The five TOD station sites are classified into urban TOD station sites and neighborhood TOD station sites by the mode proposed by Calthorpe (Citation1990, 6–7). Toa Payoh Station and Tampines Station not only serve new towns but also as the CBD peripheral centers. As they are high in urban center hierarchy, they are classified as the urban TOD station sites. Clementi Station, Pasir Ris Station, and Punggol Station are neighborhood TOD station sites serving new towns. With little government-funded public housing developments in the area, Bukit Timah has one of the highest densities of private housing out of any other planning areas in Singapore. Compared with the other two estates areas, it has a well-developed mass rapid transit system (Marine Parade Estate has not been served by the Mass Rapid Transit network) and a representative urban residential environment (Central Area Estate is dominated by commercial and business functions). Sixth Avenue Station and Farrer Road MRT Station, which are located among high-end condominiums and private houses, are chosen as typical case of Non-TOD station from six MRT stations in Bukit Timah ().

Table 1. Basics of seven rail transit stations.

Table 2. Basics of new towns where the seven stations locate.

3. Comparison and analysis of the station areas based on their land use characteristics

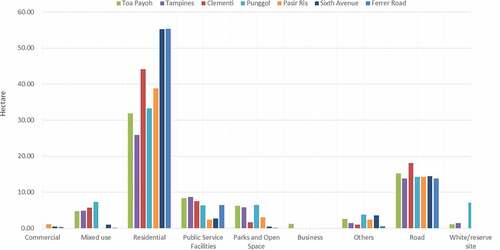

In this study, GIS approach is applied for spatial statistics and analysis of the area within 500 m of the rail transit station sites. The charts below show a comparison of the seven rail transit station areas in terms of land use analysis and aerial view (, and ). The following rules and conclusions can be made from the comparison.

Table 3. Land use analysis of the area within 500m of the seven rail transit station sites.

Table 4. Aerial view of the areas within 500m of the seven rail transit station sites (Source: google map).

3.1 Comparison of TOD station sites and non-TOD station sites in land use characteristics

In comparison to non-TOD station site, a TOD station site has higher entropy index of mixed land use and value of Commercial Compactness. In the station area of the five TOD stations, the entropy index of land use mix averages at 0.76, and the proportion of residential land 44.27% (, ). In the rail transit station area of the private estate, the average entropy index of land use mix is merely 0.36, but the proportion of residential land is over 70%. The value of Commercial Compactness of every site area shows evident difference. In general, the Compactness values of non-TOD sites are far less than that of TOD sites. For the Farrer Road MRT station, the value is only 0.56 which means it has no extra commercial gravity compared to other spot in this region. In addition, the proportion of park and open space of non-TOD sites is significantly insufficient compared to that of TOD sites. These data show that, in the TOD station area, a rail transit station is integrated with commercial and public facilities, becoming a public activity center of the city. The transport system and spatial structure of the city promote each other, exhibiting a strong spatial interaction. In the non-TOD station site in the private estate, however, no notable synergy of commercial and public facilities with transport facilities is seen. Though the proportion of residential land is high, land use is less mixed. The aerial views () further show the spatial difference between the two types of station areas. The exits of the Farrer Road MRT station and the Sixth Avenue MRT station are located along the road, which are not integrated with large commercial buildings or public facilities. Their surrounding urban space has the characteristics of small scale and self-generation. The station sites do not have a strong central catalyst capacity. For the TOD sites, except that Pasir Ris MRT Station and Punggol MRT Station hold some reserved land kept undeveloped. The other three sites witnessed a high-intensity development where integrated building complex and bus interchange are connected together in station core areas. The spatial structures are characterized by compactness and centripetal development.

Table 5. Comparison of seven rail transit station areas in land use characteristics.

In new towns of Singapore, a land use pattern oriented to transit villages is gradually developed in TOD station areas. This pattern realizes a balanced land use of residence, retail, catering, public services, and parks and green space to a certain extent. In terms of land use composition of the five TOD station areas, residential land occupies the most area, ranging from 30% to 60%. Commercial and mixed-use land is mainly used for retailing and catering, so as to ensure daily living consumption of the residents in the town. The proportion of such land ranges from 7% to 30% according to the different locations and positioning of the stations. In addition, proportions of the land for public service facilities, parks and green space, and roads are roughly the same, ranging from 7% to 11%, 2% to 8%, and 17% to 24%, respectively. These data reveal that, new towns coordinate urban land use and transport planning in their development. Both node attributes and place attributes of the transit station area are considered and unified.Footnote3Footnote4Footnote5Footnote6

3.2 Analysis of the difference in land use of TOD station sites: site hierarchy and development concept

Five TOD station sites vary in land use, especially for proportion of white site, land use mix degree, proportion of commercial land, and proportion of residential land. The author believes that such difference represents their difference in hierarchy of the TOD station site and the development concept of the new town.

Study finds that the stations vary in the proportion of white site and reserve land, which can be explained by the fact that the difference in their locations and development degrees results in their varied demands for land reserve and mixed use development in the future. In the region with superior location and huge development potential, the flexibility given to the white site allows developers to strategize their development activities to the best of their interests in responding to the changing market conditions. Under the URA’s white site guidelines, developers are free to decide on the mix of uses and the respective quantum of floor space of each use for the site as long as the total permissible gross floor area (GFA) for the whole development is not exceeded (Tien Foo, Shi Ming, and Seow Eng Citation2002). Pasir Ris Station, as a terminal station of the East-West Line of Singapore, is not fully developed. It has the highest proportion of White site, as high as 20%. The purpose is to make the most valuable land developed in a more flexible way, which helps developers to adjust the proportion of land use according to the market demand. Clementi Station, as a well-developed station in the core area of the new town, has no vacant land. It can be learned from this fact that, the station area shall not overdraw its future appreciation and development for immediate interests. Instead, long-term and short-term planning shall be coordinated for their holistic development. Different land reserve and development strategies shall be adopted for different types of station areas, to achieve sustainable development of rail transit and urban land use (Ren, Yun, and Quan Citation2016).

Study shows that, in comparison to neighborhood TOD station areas, urban TOD station areas have higher proportion of commercial land, lower proportion of residential land, and higher land use mix degree. These land use characteristics reflect different positions of the station site in the hierarchy of urban public centers. Of the two urban TOD station sites, Tampines, as one of the four regional centers in Singapore, has the highest proportion of commercial land and entropy index of land use mix, but the lowest proportion of residential land. Toa Payoh is the nearest station to the downtown. As a CBD peripheral center, its proportion of commercial land is second only to Tampines. Among the neighborhood TOD station sites, Clementi station area has the lowest proportion of commercial land but the highest proportion of residential land. This is because Clementi is the smallest new town in Singapore in terms of area. This means a small demand of commercial facilities for area. In addition, it is only one stop away from Jurong East, the regional center of Western Singapore. Pasir Ris is in Eastern Singapore, the remotest from downtown. As it is not fully developed, it has the lowest proportion of commercial land and mixed-use land but the highest proportion of white site, which is as high as 20%, creating conditions for future development. It empirically reveals that development and positioning of a TOD station area shall suit local conditions and be hierarchical, in order to form a chain layout along the rail transit corridor.

Study finds development years and concepts of the new towns also result in their difference in land use characteristics of station areas. Both Punggol Station and Clementi Station are neighborhood TOD station sites, but they differ in land use characteristics. Punggol Station has higher entropy index of land use mix and more compact commercial facilities than Clementi Station. Though the land for public service facilities is similar in area, the proportion of park and green space is 8% in Punggol station area but only around 2% in Clementi station area. This difference reflects their difference in new town planning and development concept as well as the distinct land use characteristics of rail transit station areas under different spatial structures of new towns.

Clementi, seated in Southwestern Singapore, is the eighth new town planned and development by Housing & Development Board. Its development commenced in 1975. Clementi represents a mature three level structure of “Town-Neighborhood-Precinct”. On the one hand, the center of the town, closely combined with rail transit station and bus station, is a typical TOD station area. It serves both as the transport hub and spatial node of commercial and public service. On the other hand, the public transit system synergizes with the spatial structure of the new town. Mass rail transit connects the new town to the downtown Singapore; bus system links multiple neighborhoods with the center of the town; and a perfect walkway network satisfies people’s need for the daily travel in the precincts. Rail transit, bus, and walkway constitute a hierarchical transport system that suits the spatial form of the town ().

Punggol, seated in Northeastern Singapore, is a waterfront new town developed on the basis of green concept from 1998. In 2010, Housing and Development Board of Singapore unveiled plans for Punggol to be Singapore’s first Eco-town. A holistic sustainable development framework covering environmental, social and economic dimensions was drawn up to support it (Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, Ministry of National Development Citation2014). In comparison with the traditional three-level spatial structure of former new towns, Punggol, with a two-level spatial structure of “Town-Estate”, represents the new-generation town development concept of Singapore. Estate is a variant from neighborhood and precinct. Estates are mainly connected by light rail transit whose stations are densely arranged. Short interval of 300 to 350m ensures accessibility of the LRT stations within a walkable distance (Dai and Yao Citation2013). Point-type flat tower buildings provide a more open public space. LRT stations are integrated with sheltered walkway, jointly shaping the spatial form of the area. From a three-level structure to a “chessboard” two-level structure, the evolution of spatial form is grounded on a high-mobility travel pattern and the gradually networked urban environment. New social organization forms and new economic behaviors erase the lines between different hierarchies. Innovations of transport technology, such as LRT, supersede traditional bus and draw the residential units closer to town center, counteracting the value of former “neighborhood center” ().

It can be seen from the comparison of Punggol and Clementi that, development of new-generation town is more focused on the fusion of residential space with commercial facilities and open space, which further promote sustainable development of station areas. This new land use pattern in TOD neighborhood realizes a higher plot ratio. Vertical stacking of commercial facilities and residential space represents the “higher development density” advocated by the green TOD concept (Cervero and Sullivan Citation2010). In the mean time, the urban space within 500m of the station site has more compact commercial facilities and higher land use mix degree. It is also equipped with more open space, bicycling trail, and walkway network. Besides town spatial structure, from the perspective of place making, Punggol MRT Station has closely integrated transportation facilities with shopping centers, waterfront recreation spaces, walking and cycling systems to enhance the connectivity of rail transit stations (). The diverse needs of the residents have been fully considered. This planning and development pattern provides a useful lesson for the environmental-friendly and sustainable development of TOD station area. The TOD concept not only aims to improve the public transport rate, but also to guide a sustainable urban lifestyle. Through the well-connected transportation system, reasonable space layout, place-making strategies of the site area, ecology and health concept will be integrated into the daily life of residents.

4. Conclusion

The concept of transit-oriented development is practiced in Singapore earlier than the rise of TOD theory in the west. Singapore, like most Asian cities, gives expression to a choice for high-density cities to cope with urbanization. Through decentralization and integration of transport and land use, the urban spatial structure is optimized. This study selects the seven rail transit station sites in Singapore as the study objects for comparison and analysis of their land use characteristics. The study finds that, a TOD land use pattern oriented to transit villages is gradually developed in new town’s station areas in Singapore. This pattern realizes relatively stable proportions of residential land, commercial land, land for public service facilities, parks and green space, and roads. In terms of land use characteristics, TOD station areas have significantly higher entropy index of land use mix, more compact commercial facilities, and higher proportion of park and open space than non-TOD station areas. Such characteristics further show that, under the concept of transport and land use integration, rail transit station area becomes the transport and commercial center of the new town. The transport system and urban spatial structure promote each other. In the mean time, urban TOD station sites have higher proportion of commercial land and land use mix degree in comparison to neighborhood TOD station sites. This means that integration of transport infrastructure with land use shall suit local conditions. The position of station sites in the hierarchy of urban public centers shall be considered for coordinated planning.

This study further reveals that, in additional to emphasis on commercial development of the core area, sufficient public service facilities, a certain proportion of park and open space, and white site shall be ensured for sustainable TOD development. Small-size life circle within a walkable range and sufficient green open space help create of an environmental-friendly and ecological transit village and realize overall balance among the sustainable development of land economy, economy, and society.

Two spatial structures of new towns in Singapore can be deemed as the two spatial organization forms of TOD transit villages in high-density Asian cities. No organization form is definitely better than the other. A suitable form will be adopted after comprehensive consideration of the economic and social development of the station location and maturity of its transport system. The two-level spatial structure of “Town-Estate” requires higher development intensity and more public space, which inevitably rely on a well-developed public transport system. In comparison to the three-level structure, in a town of two-level structure, the neighborhood center connecting precincts with towns no longer exist and residential units tend to be homogeneous and decentralized. Some place-making and environment design means are needed to enhance socializing activities and neighborhood identification of the residents. In short, the planning and design toward a green TOD model not only need to have a suitable land structure, mixed and balanced land use pattern, but also need to integrate the ecology and health concept to achieve higher efficiency, higher proximity, and greater synergy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for its support to the research work at the National University of Singapore; and Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), Land Transport Authority (LTA), Housing and Development Board (HDB) for their information to support this study. The author also acknowledges the support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Contract No.51778529) and the Basic Research Founds of Central Universities of China (Contract No.skqy201509).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Data comes from Department of Statistics (Citation2017), Population Trends 2017, Singapore.

2 The distance to the city downtown shall be the linear distance from the state site under study to Raffles Place Station in the downtown.

3 Entropy index of land use mix is calculated by EI = {-Σk [(pi) (ln pi)]}/(ln k), where 0≤ EI≤1. The bigger and more closer to 1 EI is, land use is more diversified. In the equation, k stands for the number of land use types, pi for the proportion of the area of land use type i in total area, and i for the land use type (residential, commercial, etc.).

4 Calculated by the ratio of the commercial land density in the area within 500m of the station site to the commercial land density in the entire new town area.

5 Public service facilities include libraries, gyms, schools, and neighborhood service facilities.

6 The concept of white site was first introduced in 1995 in the URA land sale program to provide greater flexibility in zoning.

References

- Barter, P., and E. Dotson. 2013. “Urban Transport Institutions and Governance and Integrated Land Use and Transport, Singapore.” Accessed 10 August 2018. http://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/GRHS.2013.Case_.Study_.Singapore.pdf

- Barter, P. A. 2008. “Singapore’s Urban Transport: Sustainability by Design or Necessity?” Spatial Planning for a Sustainable Singapore 2008: 95–112.

- Bernick, M., and R. Cervero. 1997. Transit Villages in the 21st Century. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Calthorpe, P., and Associates. 1990. Design Guidelines/Final Public Review Draft for Sacramento County Planning Community Development Department.

- Calthorpe, P. 1993. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Cervero, R. 1998. The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry. Washington, DC: Island press.

- Cervero, R., C. Ferrell, and S. Murphy. 2002. Transit-Oriented Development and Joint Development in the United States: A Literature Review. TCRP Research Results Digest 52. Washington, DC: National Research Council.

- Cervero, R., and J. Murakami. 2009. “Rail and Property Development in Hong Kong: Experiences and Extensions.” Urban Studies 46 (10): 2019–2043. doi:10.1177/0042098009339431.

- Cervero, R., and C. Sullivan. 2010. Toward Green TODs. Berkeley: Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California.

- Community Design + Architecture. 2001. Model Transit-Oriented District Overlay Zoning Ordinance. Oakland, CA: Valley Connections.

- Dai, D., and D. Yao. 2013. “The Research on the Hierarchy of Spatial Structure’s Change and Adaptability of Singapore.” Planners S2: 70–73.

- Department of Statistics. 2017. Population Trends 2017. Singapore: Department of Statistics.

- Ewing, R., and R. Cervero. 2010. “Travel and the Built Environment: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (3): 265–294. doi:10.1080/01944361003766766.

- Florida Department of Transportation. 2012. Florida TOD Guidebook. Accessed 13 April 2017. http://www.fltod.com/Florida%20TOD%20Guidebook-sm.pdf

- Frank, L. D. 2010. Neighbourhood Design, Travel, and Health in Metro Vancouver: Using a Walkability Index; Executive Summary. Vancouver: UBC Active Transportation Collaboratory.

- Jacobson, J., and A. Forsyth. 2008. “Seven American TODs: Good Practices for Urban Design in Transit-Oriented Development Projects.” Journal of Transport and Land Use 1 (2): 51–88. doi:10.5198/jtlu.v1i2.

- Kockelman, K. M. 1997. “Travel Behavior as a Function of Accessibility, Land Use Mixing, and Land Use Balance: Evidence from the San Francisco Bay Area.” Transportation Research Record 1607: 116–125. doi:10.3141/1607-16.

- Li, C.-N., C. Lin, and T.-K. Hsieh. 2016. “TOD District Planning Based on Residents’ Perspectives.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 5 (4): 52. doi:10.3390/ijgi5040052.

- Ma, Q. 2003. “Latest Studies on TOD in the United States.” Urban Planning Overseas, (05): 45–50.

- Maryland Department of Transportation, 2000. Report to Governor Parris N. Glendening. From the Transit-Oriented Development Task Force.

- Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, Ministry of National Development. 2014. Sustainable Singapore Blueprint 2015. Singapore: Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, Ministry of National Development

- Newman, P., and J. Kenworthy. 1999. Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence. Washington, DC: Island press.

- Ren, L., Y. Yun, and H. Quan. 2016. “Study on Classification and Characteristics of Urban Rail Transit Station Based on Node-Place Model: Empirical Analysis and Experience Enlightenment of Singapore.” Urban Planning International 01: 109–116.

- Renne, J. L. 2009. “Evaluating Transit-Oriented Development Using a Sustainability Framework: Lessons from Perth’s Network City.” In Planning Sustainable Communities: Diversity of Approaches and Implementation Challenges, edited by S. Tsenkova, 115–148 Calgary, Canada: University of Calgary.

- Schwaab, J., and S. Thielmann. 2002. “Policy guidelines for road transport pricing: A practical step-by-step approach.” United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific & Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ). 12 (6): 525–36. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2002/er01).

- Still, T. 2002. "Transit-Oriented Development: Reshaping America’s Metropolitan Landscape."In On Common Ground: REALTORS & Smart Growth, 44–47. Washington, DC: National Association of Realtors.

- Suzuki, H., R. Cervero, and K. Iuchi. 2013. Transforming Cities with Transit: Transit and Land-Use Integration for Sustainable Urban Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Tien Foo, S., Y. Shi Ming, and O. Seow Eng. 2002. ““White” Site Valuation: A Real Option Approach Care.” Pacific Rim Property Research Journal 8.2 (2002): 140–157. doi:10.1080/14445921.2002.11104120.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). 1971. Singapore 1971 Concept Plan. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority.

- Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). 1991. Singapore 1991 Concept Plan. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority.

- Yang, P. J., and S. H. Lew. 2009. “An Asian Model of TOD – The Planning Integration and Institutional Tools in Singapore.” In Transit-Oriented Development: Making It Happen, edited by C. Curtis, J. L. Renne, and L. Bertolini. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Zhang, M. 2004. “The Role of Land Use in Travel Mode Choice: Evidence from Boston and Hong Kong.” Journal of the American Planning Association 70 (3): 344–361. doi:10.1080/01944360408976383.