ABSTRACT

To alleviate the burden of high residential costs for the younger population, the Korean government has recently implemented a public rental housing program for those who are vulnerable in their residential conditions and endure low quality of life. This program is not yet fully effective in achieving its policy aim because of lengthy construction periods and consistent vacancies (despite high demand). To address this issue, policy guidelines are sought. This study comprehensively models supply and demand of public rental housing and analyzes the effects of diverse policies on the rental housing system behaviour. To represent the rental housing system, system dynamics is applied which consists of continuous simulation based on causal relationships among variables encompassing their time-lagged effects (and in which system variables are highly interdependent). By testing the effects of policy variables of public rental housing delivery strategies upon the system, the developed model provides an in-depth understanding of policy impacts towards achieving a desired policy objective (in this case to accommodate more public rental housing demands by minimizing vacancy rates). The results provide guidelines for developing detailed policies for more efficient public rental housing project delivery, which can contribute to alleviating the residential problems of the younger population.

1. Introduction

Low- and middle-income residents in many populated metropolitan areas worldwide have suffered from living in poor residential environments because of rapidly increasing housing and rental prices (Hwang et al. Citation2012; Yuan et al. Citation2017). This is certainly the case in Korea, particularly for the younger population (20–34 years old) which includes university students, early career professionals, and newlyweds. To minimize high residential costs, ~80 % of single person households among the younger population in Korea currently live in a narrow living space of just 8.8–10.8 square meters (MOLIT Citation2017). Many newlyweds also struggle under the burden of excessive loans for purchasing or renting houses.

In 2012, the Korean government announced a new housing program for developing low-priced public rental houses to alleviate the residential problems of the younger population. Specifically, this policy aimed to develop small-size public rental housing complexes to accommodate university students, early career professionals, and newlyweds, all of whom are vulnerable in their residential conditions and endure a low quality of life (MOLIT Citation2017). The first project in this public rental housing program was approved in 2013. By 2016, building sites for some 140,000 new public rental houses had been secured and 202 public rental housing construction projects (for 102,000 households) had been approved (MOLIT Citation2017).

Despite high expectations for the impact of the policy, this new public rental housing program has not yet proved adequate for solving the residential problems of the younger Korean population. This is primarily because of the lengthy period from construction project initiation to move-in date. Therefore, policy makers have considered diverse countermeasures to accelerate the supply of public rental houses to potential residents. Specifically, reducing the time to deliver completed houses is a critical concern for implementing countermeasures, which focus on the many factors that impact the time required to supply this new public rental housing. Supply-related factors include project approval, planning, and the construction process. On the demand side, the main controllable factor is the selection process of potential eligible residents. However, considering that such factors are highly interdependent, it is difficult to analyze the effectiveness of each policy for rapid rental house delivery, while maintaining the balance between supply and demand. In this paper, the supply and demand for public rental houses is comprehensively analyzed to provide a new policy direction for more efficient public rental housing development and delivery. System dynamics (SD) is used to model the supply and demand of the rental housing market in Korea. SD consists of a continuous simulation based on the causal loop diagram to understand a feedback process in a complex system and uses the stock-and-flow diagram to capture changes of variables over time (Sterman Citation2000; Hwang et al. Citation2012; Park et al. Citation2009). SD is also effective at representing time-lagged effects among variables on the system (eg, time-delayed policy impacts) (Sterman Citation2000). Hence, it is expected that the developed SD model will be able to capture how the countermeasures to reduce the time for developing public rental houses and to select potential residents affect the changes in the housing supply and demand over time. By applying several potential countermeasures to the developed model (eg, reducing the time for project approval, construction, and potential resident selection, and preventing frequent turnover of residents), important policy implications are derived for the effective development and timely delivery of the new type of small and low-priced public rental houses. Consequently, the research outcome will contribute to designing more effective public rental housing policies to alleviate the residential problems of the younger population.

2. Research background

2.1. New public rental housing program

The recent public rental housing program was designed to supply low-rent properties to low- and middle-income residents who are not currently homeowners. Eighty per cent of the rental houses will be provided to the younger population (20–34 years old). The remaining 20% will be provided to others in need, such as low-income pensioners. This program utilizes public lands located in central urban areas. Hence, rental rates can be significantly lower than market rate. More specifically, the monthly rental rate in Seoul is only 60–80% of the rental rate for a house of the same size in the surrounding area (MOLIT Citation2017). One of the 16 square meters of these new rental houses is almost 100USD with 3,000USD security deposit. To reduce rental payments for potential residents, the area of a single rental house is kept under 29 square meters for single households and under 45 square meters for newlyweds (a small-scale house). The rent-to-income ratio (ie, the proportion of salary spent on rent) of the Korean younger populations has continuously increased in recent years from 22.4% in 2008 to 27.8% in 2012 (MOLIT Citation2017). The new public rental housing program is expected to alleviate the high housing expenditure of the younger population, thereby stabilizing their lives. This program can help them to eventually become homeowners. In Korea, the average income of the younger population (20–34 years old) is ~30,000USD, while the average house price is 240,000USD. This situation means that residents in these new rental houses (particularly newlyweds) can continue to rent for up to 10 years.

It is questionable to what extent this new public rental housing program can alleviate the housing problems of the younger population because of a lack of understanding of how potential demands vary within the public rental housing supply process. More specifically, because of the strict qualification requirements (eg, only newlyweds who earn less than average earnings with under ~200,000USD of total assets are eligible) the demand from those eligible for these rental houses significantly changes over time (due to increases in their income level and the value their assets). Although the new public rental housing program (which aimed to supply 150,000 houses) was first announced in 2012, most of the projects in this program are still in the planning and construction stages. The lengthy rental house delivery process can result in changing demands when selected potential residents become disqualified due to delayed move-in dates. Consequently, comprehensive understanding of the changes in supply and demand for public rental houses is required to maximize the impact of the policy.

2.2. Research methodology: system dynamics (SD)

For the purpose of maintaining residential stability, considerable research efforts have been undertaken to propose policy guidelines for the continued supply of low-cost high-quality housing. Specifically, public rental housing delivery in high-density urban areas is one of the critical governmental efforts to solve citizens’ residential problems. Many studies have tried to provide policy implications towards the effective development of public and subsidized rental housing (Lee and Ronald Citation2012; Ahmed Citation2017; Peña and Ruiz-Castillo Citation1984; Grange Citation1998; DiPasquale Citation1999; Golland and Boelhouwer Citation2002). These studies focused on analyzing the impacts of public rental housing policies on the structure of the housing market, eg, rental housing demand and residential equity (Lee and Ronald Citation2012; Peña and Ruiz-Castillo Citation1984; Grange Citation1998; Golland and Boelhouwer Citation2002) and designing better public rental housing delivery strategies (Hwang et al. Citation2012; Ahmed Citation2017). Although housing supply and demand mechanisms interact with each other, these studies did not comprehensively analyze rental housing supply and demand.

Many studies on the housing and rental housing market have tried to simultaneously understand both supply and demand from a complex housing systems perspective (Hott and Monnin Citation2008; Hwang et al. Citation2012). SD is a causal loop diagram- and differential equation-based continuous simulation which is widely used in housing market studies. It provides comprehensive understanding and analytic solutions for complex systems (Richardson Citation1985; Sterman Citation2000; Williams Citation1994) such as housing systems (eg, interactions between housing supply, demand, and prices). SD was successfully applied to analysis of the housing market, leading to the development of effective policies for stabilizing the housing market (Hwang, Park, and Lee Citation2013; Ghaffarzadegan, Lyneis, and Richardson Citation2011; Shen et al. Citation2009). One particularly powerful ability of SD is that it can be used to analyze how policy factors affect key variables in the system under complex interactions among variables (Abdel-Hamid Citation1993). SD can help to provide an understanding of the effects of rental housing policies upon demand over time, and vice versa. By encompassing time-lagged relationships among variables, SD can be particularly effective at analyzing how time variables affect the public rental housing delivery processes and consequently alter the balance of the public rental house supply and demand over time, which is useful information for policy making.

Although econometric models have been used to make accurate predictions on future rental housing supply and demand, they can capture unexpected system behaviours caused by many dependent variables interacting with each other, which can make it unsuitable for the prediction of policy impacts. To understand system behaviour according to diverse policies, it is effective to analyze the housing system focusing on its fundamental structures (eg, causal relationships among variables). In this regard, a robust model is required that can depict the fundamental structure of the rental housing system and is simple enough to easily understand the underlying mechanisms of the system behaviours. Developing such a model is the main objective of this paper.

3. Model development

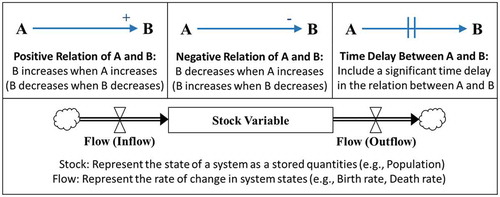

This section describes in detail the developed public rental housing supply and demand model. The SD model is developed based on the principles of the housing development, delivery process, and demand changes. shows the modelling elements of SD. Because the main principle of SD is the causal relationship among variables, such a relationship is represented by an arrow between two variables, which can be either positive or negative, and either of which can encompass a time-lagged relationship. Specifically, a plus notation on the arrow indicates that a dependent variable increases when a preceding variable increases, or vice versa (ie, a positive relationship). A minus notation on the arrow indicates that a dependent variable decreases when a preceding variable increases, or vice versa (ie, a negative relationship) (Sterman Citation2000). Additionally, double cross-lines on the middle of the arrow mean that there is a significant time delay in the relationship between the two variables (Sterman Citation2000).

A stock-and-flow diagram in the SD includes a stock variable that represents the state of a system (eg, demand, population, and price) and a flow variable that shows a rate of change in the stock variable (eg, inflow and outflow rates of demand, population, and price) (Sterman Citation2000). By using these two variables, SD can effectively represent how the amount of system variables change over time according to influence factors that affect the inflow and outflow rates of a stock. It is important to note that causal relationships of variables can form feedback loops, which aid the understanding of internal system behaviours. Using these model elements, a better understanding can be gained of how the supply and demand system behaves by itself over time. By including external policy variables, the policy impacts on system behaviours can also be captured. In the following sub-sections, the separate supply and demand models are described. The interaction between supply and demand is also explained.

3.1. Supply model

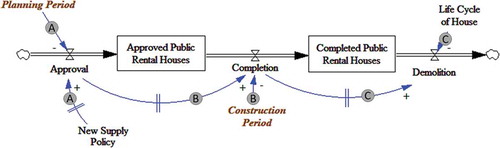

represents the overall process of public rental house development throughout its life cycle, including project approval, construction, and operations. This process is very similar to most public and private housing construction processes. Hence, the core mechanism of the housing supply model previously developed using SD is adopted (Hwang et al. Citation2012; Hwang, Park, and Lee Citation2013; Park et al. Citation2009).

It takes several years for rental housing projects to be approved. This is because of the lengthy period for land purchasing, licensing, and project planning (A in ). shows that a delay function that impedes the impact of variables provided by the SD modelling software (ie, the DELAY FIXED function) is used to represent a time-delayed process between the announcement of a new public rental housing supply policy and its approval (A in ). After project approval, construction periods lasting several years are required to complete these rental housing projects (B in ). The DELAY FIXED function is also used to show the time delay between project approval and completion, as shown in . In this model, the whole lifecycle of the public rental house is represented by involving a variable named “Demolition,” despite the very lengthy life of the house (eg, at least 30 years: C in ).

Table 1. Variables in the public rental house supply model.

In this model, there are two stock variables. Firstly, “Approved Public Rental Houses,” which is accumulated by an inflow of “Approval” and resolved by an outflow of “Completion.” Secondly, “Completed Public Rental Houses,” which is accumulated by an inflow of “Completion” and resolved by an outflow of “Demolition..” These two stock variables are used to capture the states of public rental housing supply over time.

3.2. Demand model

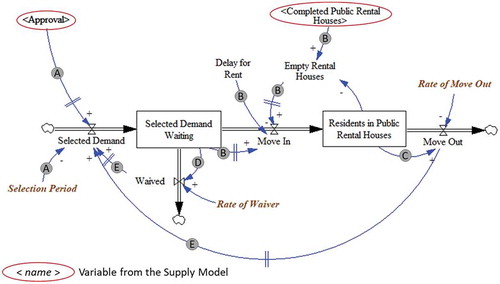

shows the changes of public rental housing demand over time accounting for supply (as shown in ). Demand is near limitless because of the attractiveness of the new public rental house with its downtown location and low rent. On average, only 8 % of applicants were selected for placement in 300 new public rental houses developed in March 2017 in Seoul (MSF Citation2017).

To select the most eligible households, the government sets strict qualification requirements which take into account the applicant’s age, monthly income, home ownership, and total assets (ie, real estate, car ownership, etc.) (MOLIT Citation2017). Based on these criteria, future residents of the approved houses are carefully determined via selection procedures that take several months at least (A in ). A variable named “Selected Demand” in the model is designed using a delay function (ie, DELAY FIXED function) that represents a time delay between “Approval” and “Selected Demand” by the “Selection Period,” as shown in .

Table 2. Variables in the public rental house demand model.

These “Selected Demand Waiting” need a significant amount of time to move into the rental house, because of lengthy construction periods (B in ). Public rental housing supply in the model (ie, the variable named “Completed Public Rental Houses”) is a critical factor for determining how rapidly demand is resolved. Also, it is likely to incur an additional moving-in delay for selected demands caused by personal reasons (eg, remaining contract with previous houses) (“Delay for Rent” in B of ).

It is important to note that a term to live in the new public rental houses for current residents is terminated when their qualifications (eg, age, monthly income, home ownership, and amount of assets) no longer satisfy requirements (C in ). For example, their monthly income may gradually increase over time, eventually exceeding the maximum income allowed. Consequently, they would be required to move out of the house. Although the selected demand subjects do not move into the house while waiting for completion of its construction, they no longer qualify for this house if their qualifications start to exceed the maximum requirements before the move-in date (eg, monthly income starts to exceed the maximum while waiting for the move-in date) (D in ). Subsequently, additional future residents for the houses, for which vacancies arise from the disqualified selected demands and previous residents who moved out, will be re-selected by repeating the lengthy selection procedures (E in ). describes the details of the variable equations.

4. Simulation cases

4.1. Base case simulation

Using the developed model, this study conducts realistic test case simulations to analyze the impacts of changes in new public rental house supply and demand. The test case simulations focus on the new public rental house projects developed in Ulsan, Korea. Ulsan has always had high demand for rental houses because of a large population of young workers staffing multiple industrial facilities. Recently, demand has significantly increased because many governmental institutions, public companies, and research institutes have moved to Ulsan. This has resulted in excessive potential demand for public rental houses which far exceeds the city’s amount of planned supply. The initial time for the test case simulation is January 2015. This was when the public rental house projects in Ulsan were first planned. Changes of model variables are simulated during the following 72 months (6 years).

describes the values of the input variables in the model. In 2015, 1,046 new rental houses were first approved and waiting to begin construction. A similar or greater number of houses were to be planned every year (MOLIT Citation2017). Therefore, initial values of two stock variables named “Approved Public Rental Houses” in and “Selected Demand Waiting” in are 1,046. No specific initial values of the other stock variables in and are assigned (ie, the default initial values of stock variables are zero). Although there were plans for developing 800 rental houses in Ulsan in 2016 (and a similar number or more after 2017), no specific amount of housing development after 2017 has yet been determined. Therefore, the amount of new public rental house supply is assigned to the variable named “New Supply Policy” in the model as a random number between 400 and 800 every six months (between 800 and 1,600 houses every year).

Table 3. Values of input variables.

According to the actual processes for planning and constructing the public rental houses, as well as selecting its potential residents in Ulsan (MOLIT Citation2017), values of the variables in the model of “Planning Period,” “Construction Period,” and “Selection Period” were set as 9, 18, and 6 months, respectively.

As mentioned previously, residents in the new public rental houses should move out from their house when they lose eligibility. Considering the statistics on these new public rental houses, it is found that under 5% of selected demand and current residents lose their qualifications every month. However, it is difficult to determine accurate variable values. To overcome the difficulty in setting exact variable values, values are calibrated based on the real statistics of supply and demand changes for public rental housing. There continuously exist vacancy rates of 10–30% in public rental housing over all of the sub-regions in Korea (MOLIT Citation2018; Yonhap News Citation2017). As shown in the base case simulation in Figure 4, consistent 10–30% vacancy rates (ie, 70–90% occupancy rates, shown as a thick line in ) of the rental houses are simulated when 4 % “Rate of Move Out” and 4 % “Rate of Waiver” values in the model are assigned. Therefore, 4 % “Rate of Move Out” and 4 % “Rate of Waiver” values are set for the base case simulation. Based on these variable values, sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the impact of detailed policies on the supply and demand of the new public rental houses by comparing each policy simulation result with a base case simulation result.

4.2. Sensitivity analysis

Clearly, increased supply of public rental houses can help to alleviate the residential problems of the younger population. However, the amount of new public rental houses that can be developed will have limits imposed by limited available land and governmental budget constraints. The base case simulation result in shows that if vacancy rates are minimized, existing public rental houses can accommodate more potential demand. This result indicates that governmental policies to solve the imbalance of public rental house supply and demand by reducing vacancy rates can help to provide more potential demand to benefit from the new public rental housing program.

One of the most effective policy directions for achieving balance between public rental house supply and demand (ie, low vacancy rate) is faster housing development. This is because more potential sources of demand (ie, residents-seeking housing) can rapidly move into the new house, thus avoiding vacancy. Accounting for the possible impact of different housing development periods on the balance, this study compares three scenarios: (1) a normal case that is the same as the base case; (2) a shortened case, where the public rental house planning and construction periods, as well as the resident selection period, are shorter than those in the normal case; and (3) a delayed case, where all periods are longer than those in a normal case. provides a detailed description of these cases.

Table 4. Scenario #1 of sensitivity analysis: different time for public rental house delivery.

– show sensitivity analysis results for: the amount of completed public rental houses over time (), the number of residents in the new public rental houses over time (Figure 6), and the amount of vacant houses () over time (according to different periods to (i) develop the public rental houses and (ii) select the potential residents). clearly shows that shortened project periods can lead to early supply of public rental houses (Case (2)). Despite the same amount of rental housing supply in the three cases (ie, normal, shortened, and delayed), the supply capacity to accommodate potential demands varies with the different cases, as shown in and . Delayed project planning and development causes delayed supply and increases vacant rental houses in the long-term, which aggravates the imbalance between the public rental house supply and demand. Therefore, potential demand for the rental houses cannot fully benefit from the new public rental housing program because of consistently low occupancy rates. Specifically, because the “Selected Demand Waiting” in need to wait for their move-in date until the construction is completed, they face a higher probability that they will lose their qualified status during the long construction period (ie, because of the potential rise in their income and assets). In this situation, it is necessary to rapidly replace the disqualified applicants. At the same time, current residents can also lose their eligibility. As soon as residents become more stable (higher income, savings) they are forced to find new accommodation at short notice. Because the additional selection process for replacement residents requires a minimum of several months, vacancy of the public rental house during this period is inevitable. More importantly, a longer selection process can lead to higher vacancy rates, as shown in Case (3) in . Therefore, it is important to reduce public rental house project planning and construction periods, as well as selection periods, to reduce vacancy rates. The policy implications of this issue will be discussed in the next section.

Changing the qualification loss rate of potential and actual residents, which represents the frequency of both potential residents’ change and actual residents’ moving-out, can also affect the balance between public rental housing supply and demand. As mentioned previously, both “Rate of Waiver” (a variable that affects to what extent the qualification of selected demand waiting is lost over time) and “Rate of Move Out” (a variable that affects to what extent the eligibility of current residents in the houses is lost over time) are set to 4 % in the base case simulation. These rates can vary according to many policies, such as mitigated or strengthened qualifications, and the grace periods for move-out when current residents become disqualified. This study compares three scenarios: (1) a normal case that is same as the base case; (2) a case of lower qualification loss rates, and (3) a case of higher qualification loss rates. provides a detailed description of these cases.

Table 5. Scenario #2 of sensitivity analysis: different rate in loss of eligibility of potential and actual rental house residents.

– show sensitivity analysis results for completed rental houses over time (), the number of residents in these houses over time (), and the number of vacant houses () over time, according to different qualification loss rates of potential and actual demand. These different rates cannot affect the total amount of public rental house supply (as shown in ), but only affect the in-flow and out-flow of potential and actual residents. However, as shown in and , the more frequently the eligibilities of potential and actual residents are lost with a higher eligibility loss rate, the less actual residents there will be over time, because of the increase in the number of vacant houses. This result implies that more frequent replacements for the disqualified potential and actual residents are needed through a lengthy additional selection process. Policy direction thus needs to lower the qualification loss rate of potential and actual residents, which will be discussed in detail in the next section.

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy implications

The simulation results from the developed model show critical policy implications for effective public rental housing planning and development. Specifically, as well as impeding public rental housing project completion, delay in the project planning and development process can cause significant imbalance between supply and demand by increasing the vacancy rates of rental houses (see –). A critical factor in causing delay in public rental housing supply is the lengthy project approval and construction periods, which can take two years or more. During this lengthy period, it is more likely for selected potential residents to lose their eligibility by requiring additional time to select substitutes for disqualified persons. This causes delays in the occupation of completed public houses and results in the houses becoming vacant while waiting for these substitutes. Therefore, policy makers need to focus on addressing many issues that affect the project approval process such as conflicts with the local governments and residents as well as private rental housing suppliers. By significantly reducing project approval and construction periods, negative effects of time-lagged supplies on demand changes and the consequently lengthy periods of vacancies can be minimized. This can adjust the balance between supply and demand.

Although a simplified resident selection process can reduce vacancy rates, limiting the time for reviewing all the qualifications of candidates may cause unreasonable and thoughtless selection of potential residents. Alternatively, a more systematic review of qualifications (eg, adoption of advanced information systems for qualification review and selection) can help to promote more reasonable selection and reduce selection periods.

More waivers of potential residents and more frequent move-outs of actual residents due to becoming disqualified can also negatively affect vacancy rates. This is caused by the time required for the selection of their substitutes and their subsequent moving-in process. As shown in the second sensitivity analysis (see –), it is necessary for public rental house residents not to move out of their house within a short period of time to guarantee their residential stability and avoid high vacancy rates. One possible policy is to grant a longer grace period to move out for disqualified public rental house residences. This grace period would last until their replacements are selected and ready to move into the house. Considering trends of selection periods for current public rental housing in Korea, at least six months of grace period needs to be guaranteed.

Recently, the Korean government has attempted to ease the qualification requirements for new public rental houses to prevent a prolonged vacant period. For example, the range of eligible ages will be extended from 20–34 to 19–39 years old soon. In addition, detailed qualifications (eg, income level) for vacant houses will no longer be required in 2018. This corresponds to policy implications derived from the simulation results in this study. More importantly, enhancing residents’ satisfaction with public rental houses is essential to reduce residents’ frequent moving-out. There exists a close relationship between residents’ satisfaction and their moving intention (Gan et al. Citation2016; Li, Wang, and Sun Citation2017). Rental house price is regarded as the most important factor for residential satisfaction with rental housing (Huang and Du Citation2015). Hence, low rental payments of public rental houses need to be maintained. All these policies can help continuously maintain the balance between supply and demand by minimizing the existence of vacant houses awaiting new renters.

5.2. Research contributions

The simulation model developed here can help policy makers understand the unexpected negative impact of time-delayed relationships between variables. In particular, the impact of time-delayed resident selection and public rental house delivery on the vacancy rates of the houses. The causal loop and stock-and-flow diagrams that represent the rental housing system structure through causal relationships among system variables (a particularly concise yet robust model in this study) is effective for understanding policy impact and capturing the cause of any such impact. This model provides limited accuracy in estimating the values of future demand and vacancy rates of public rental houses. This is because the model is based on causal relationships among variables, rather than data-oriented quantitative correlations. However, this model is more useful to test and understand how the changes of variables affect model behaviours by comparing behavioural changes of the system when applying diverse policy variables. Such an understanding is critical in the policy design stage to avoid unexpectedly negative side effects of policies. Additionally, by testing which variable changes result in the greatest impact on the desired model behaviour, the simulation results can serve as a guideline for developing detailed policies.

6. Conclusions

Changes in the supply and demand of a new type of public rental houses (provided by the Korean government with the aim of alleviating the younger populations’ residential problems) was analyzed to propose alternative policy directions to achieve effective development and timely delivery of public rental housing. Specifically, the SD policy model was developed with a focus on the fundamental mechanisms of supply and demand in the rental housing system. The model can provide in-depth understanding of policy implications to achieve desired policy objectives by enabling testing of the impact of policy variables regarding public rental house delivery strategies on the system. The test results are expected to provide guidelines for developing detailed policies for more efficient public rental housing project delivery. It was found that reducing the time for project approval, construction, and potential resident selection accelerates the project completion and resident move-in dates. It also reduces the vacancy rate of public rental housing in the long-term. Minimizing the frequency of residents moving-out is also critical to reduce the vacancy rate of public rental houses. This can be achieved by easing the public rental housing qualification (eg, a longer grace period to move out for disqualified residents) and by enhancing residential satisfaction to reduce moving intention. Reducing the vacancy rate of public rental houses is key to accommodating more demand under the limited number of public rental houses.

This study contributes to better housing policy design, particularly public rental housing, by developing a concise but robust model that can test diverse policies and help to better understand how rental housing system behaviour changes over time (subject to diverse policy variables). The developed model represents the core structure of supply and demand for rental housing. Other influence factors affecting public rental housing (eg, various socio-economic and environmental characteristics of rental houses) can be added to analyze the impact of detailed policies.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1D1A1A09083708).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

June-Seong Yi

June-Seong Yi is a professor of Ewha Womans University and he received his Ph.D. in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States. His current research interest centers at the intelligent construction informatics and information management technologies to improve construction productivity.

References

- Abdel-Hamid, T. 1993. “Thinking in Circles.” American Programmer 6 (5): 3–9.

- Ahmed, K. G. 2017. “Designing Sustainable Urban Social Housing in the United Arab Emirates.” Sustainability 9 (8): 1413. doi:10.3390/su9081413.

- DiPasquale, D. 1999. “Why Don’t We Know More about Housing Supply?” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 18 (1): 9–23. doi:10.1023/A:1007729227419.

- Gan, X., J. Zuo, K. Ye, D. Li, R. Chang, and G. Zillante. 2016. “Are Migrant Workers Satisfied with Public Rental Housing? A Study in Chongqing, China.” Habitat International 56: 96–102. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.05.003.

- Ghaffarzadegan, N., J. Lyneis, and G. P. Richardson. 2011. “How Small System Dynamics Models Can Help the Public Policy Process.” System Dynamics Review 27 (1): 22–44.

- Golland, A., and P. Boelhouwer. 2002. “Speculative Housing Supply Land and Housing, Markets: A Comparison.” Journal of Property Research 19 (3): 231–251. doi:10.1080/09599910210151332.

- Grange, A. L. 1998. “Privatising Public Housing in Hong Kong: Its Impact on Equity.” Housing Studies 13 (4): 507–525. doi:10.1080/02673039883245.

- Hott, C., and P. Monnin. 2008. “Fundamental Real Estate Prices: An Empirical Estimation with International Data.” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 36 (4): 427–450. doi:10.1007/s11146-007-9097-8.

- Huang, Z., and X. Du. 2015. “Assessment and Determinants of Residential Satisfaction with Public Housing in Hangzhou, China.” Habitat International 47: 218–230. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.01.025.

- Hwang, S., M. Park, and H. Lee. 2013. “Dynamic Analysis of the Effects of Mortgage-Lending Policies in a Real Estate Market.” Mathematical and Computer Modelling 57 (9): 2106–2120. doi:10.1016/j.mcm.2011.06.023.

- Hwang, S., M. Park, H. Lee, S. Lee, and H. Kim. 2012. “Dynamic Feasibility Analysis of the Housing Supply Strategies in a Recession: Korean Housing Market.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 139 (2): 148–160. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000577.

- Lee, H., and R. Ronald. 2012. “Expansion, Diversification, and Hybridization in Korean Public Housing.” Housing Studies 27 (4): 495–513. doi:10.1080/02673037.2012.677018.

- Li, J., C. C. Wang, and J. Sun. 2017. “Empirical Analysis of Tenants’ Intention to Exit Public Rental Housing Units Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior–The Case of Wuhan, China.” Habitat International 69: 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.08.006.

- MOLIT. 2017. “MOLIT: HappyHousing.” Accessed 15 November 2017. http://www.molit.go.kr/happyhouse/info.jsp

- MOLIT. 2018. “Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) Statistics System.” Accessed 1 January 2018. http://stat.molit.go.kr/portal/cate/engStatListPopup.do

- MSF. 2017. “Ministry of Strategy and Finance of the Korean Government.” Accessed 2 January 2018. http://www.korea.kr/briefing/pressReleaseView.do?newsId=156235835

- Park, M., M. Lee, H. Lee, and S. Hwang. 2009. “Boost, Control, or Both of Korean Housing Market: 831 Countermeasures.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 136 (6): 693–701. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000159.

- Peña, D., and J. Ruiz-Castillo. 1984. “Distributional Aspects of Public Rental Housing and Rent Control Policies in Spain.” Journal of Urban Economics 15 (3): 350–370. doi:10.1016/0094-1190(84)90008-1.

- Richardson, G. P. 1985. “Introduction to the System Dynamics Review.” System Dynamics Review 1 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1727.

- Shen, Q., Q. Chen, B. Tang, S. Yeung, Y. Hu, and G. Cheung. 2009. “A System Dynamics Model for the Sustainable Land Use Planning and Development.” Habitat International 33 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2008.02.004.

- Sterman, J. D. 2000. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. New Yourk, NY: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

- Williams, T. P. 1994. “Predicting Changes in Construction Cost Indexes Using Neural Networks.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 120 (2): 306–320. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(1994)120:2(306).

- Yonhap News. 2017. Accessed 1 January 2018. http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2017/10/09/0200000000AKR20171009071951003.HTML?input=1195m

- Yuan, J., X. Zheng, J. You, and M. J. Skibniewski. 2017. “Identifying Critical Factors Influencing the Rents of Public Rental Housing Delivery by PPPs: The case of Nanjing.” Sustainability 9 (3): 345. doi:10.3390/su9030345.