ABSTRACT

In China, the remains of early Buddhist temples from five ruins have been confirmed to be from the 5th to 6th century of Southern and Northern Dynasties period, while in Korea, four Goguryeo ruins have been found. During this period, the pagoda was the most central structure in a temple, and main rituals were performed by circling around the pagoda; circumambulation. The aim of this paper was to show how the circumambulation corridor was confirmed as well as how the space was structured and planned by comparing data from the excavated ruins in ancient Korea and China. At the Chinese pagoda sites, there is evidence of a circumambulation corridor with a width of around 3 m and a floor paved with bricks materials. The wooden structure of the corridor was installed separately to the central structure of the pagoda. In addition, at the Goguryeo sites, the fact that this outer foundation layer is only found in pagodas supports such a hypothesis. It is postulated that the upper area of the corridor was covered with a sunshade and that the floor would have been paved for circumambulation rituals. As a result, the circumambulation corridor was planned separately from the pagoda as the ritual space.

1. Introduction

The Northern and Southern Dynasties period (AD420 – 589) was when Buddhism expanded and proliferated in China. To date, around five temple sites from the 5th to 6th century are known to be examples of ancient Chinese temples, with their layouts confirmed through excavation. The Northern and Southern Dynasties period of China corresponds to the Three Kingdoms period of Korea (Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla). Goguryeo was the first dynasty that adopted Buddhism from northern China and built temples. However, the Goguryeo temple sites can only be studied through excavation data from the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945) or from partial data originating from North Korea. Currently, there have only been four investigative reports on the Goguryeo temple sites, even though there were more than 29 temples recorded at that time. Buddhism and Buddhist architecture of the Goguryeo period of Korea developed due to an influential relationship with China, so it is necessary to study ancient Buddhist architecture in Korea together with Chinese examples. (Kim 1985; McBride Citation2002).

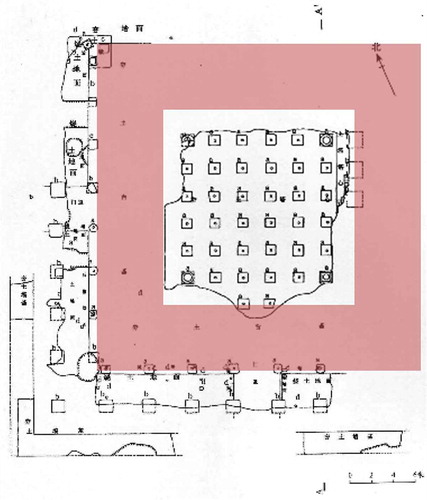

Figure 2. Wooden pagoda site of Si Yan Pagoda (Source: LSWKY Citation2007 and author edited).

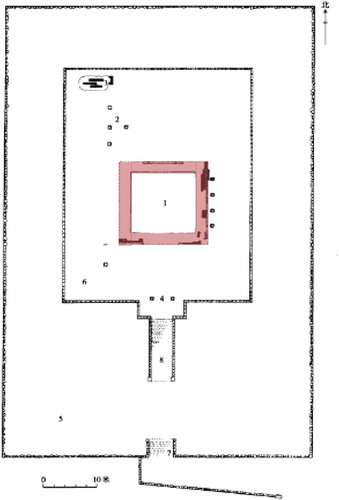

Figure 3. Layout of the Yongning Temple(Source: IACASS Citation1996).

Figure 4. Wooden pagoda site of the Yongning Temple (Source: IACASS Citation1996 and Author edited).

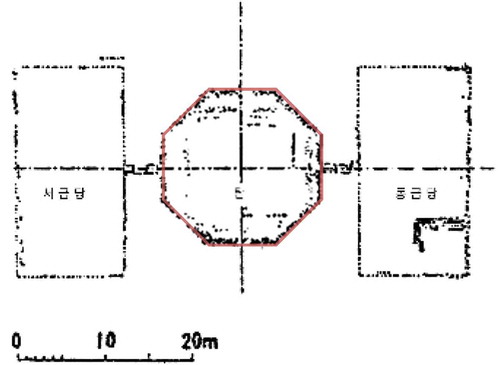

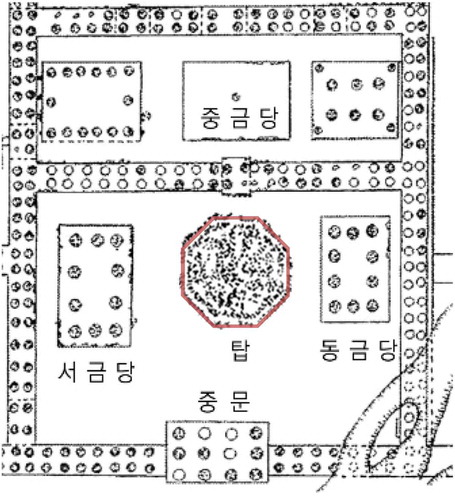

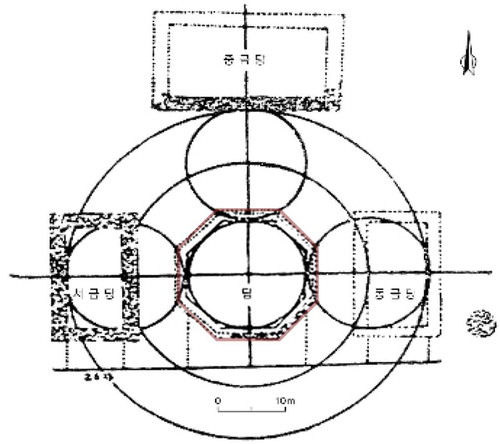

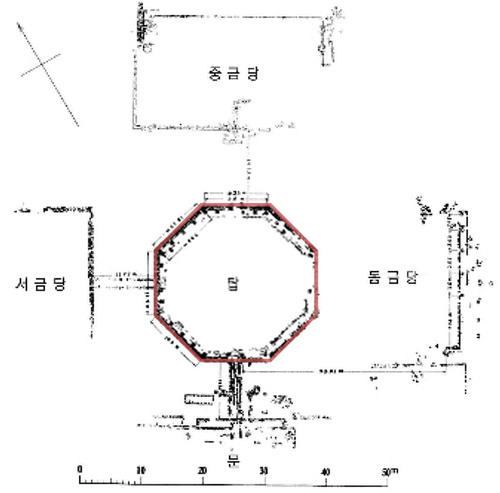

Figure 6. Sango-ri temple site (Source: BNRICH Citation2009 and author edited).

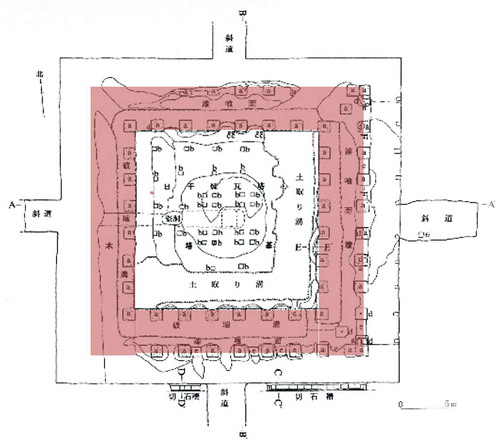

Figure 7. Juong reung temple site (Source: BNRICH Citation2009 and author edited).

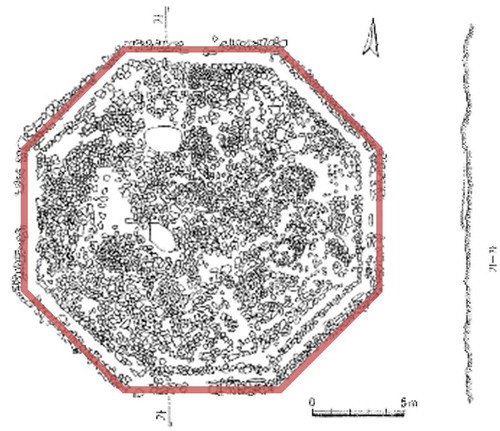

Figure 10. The pagoda at the Juong reung temple site (Source: BNRICH Citation2009 and author edited).

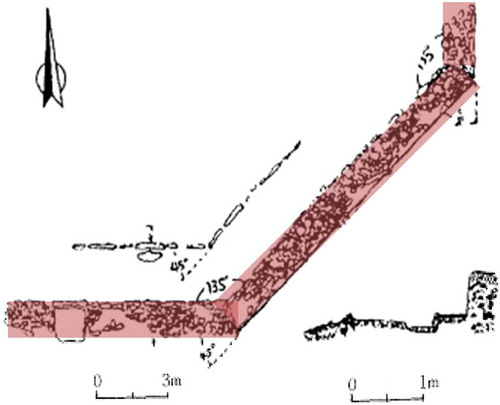

Figure 11. Detailed foundation layer of the pagoda at the Tosung-ri temple site. (Source: BNRICH Citation2009 and author edited)

In Buddhist architecture from the 5th to 6th century in East Asia, there was a pagoda temple style in which a multi-storied wooden pagoda was the central structure with square surrounding corridors or walls.(Kim and Kim Citation1985; Wang Citation1997)

This style was mainstream in Chinese Temples from the 3rd–4th century, until the 5th century, when the main hall started to be placed north of the pagoda and the outer boundary changed from a square shape to a rectangular shape.Footnote1 East-Asian temples from the 3rd to 5th centuries had a pagoda-centered layout, and this tendency was largely unchanged, although the main hall was included in the main area. When the pagoda was the central structure, the typical worship ritual was in the form of circumambulation, where prayer or worship is performed while circling the pagoda. (Jurgen Citation2012; Prakash, Gommans, and Kolff Citation2003) This habit of circumambulation naturally influenced the construction of the pagoda. (An and Kim Citation2014)

After the 5th century, the pagoda temple style developed into a style in which the main hall and pagoda were placed inside corridors or walls, but the ritual of circumambulation continued, and thus sufficient space for this had to be provided.Footnote2 Even in temple construction in the 5th–6th century, circumambulation rituals played an important role, and evidence of this can be found at ancient temple sites. (Lee Citation2005; Abe Citation1990) However, there is still a lack of research regarding circumambulation and the corresponding space in China and Korea during this period.(Han Citation2014; Liu Citation1995) The aim of this study was to concretize the circumambulation corridor as much as possible through excavation of ruins and historical investigation. This is due to the reduced amounts of excavation records remaining and the fact that the parts corresponding to circumambulation corridors in excavation sites have often been interpreted as rainwater drainage systems. Thus, this study aimed to ensure that the circumambulation corridor was constructed as a ritual space itself in Korea and China during the 5th–6th Century.

The time scope for this research is the 5th–6th century; with respect to China, this is the latter part of the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, while for Korea, it is the latter part of Goguryeo of the Three Kingdoms period. In China, there are three temple sites with remains of a circumambulation corridor found in the vicinity of ancient capital cities near the Yellow River of the Northern Wei Dynasties. From the Goguryeo temple sites, four sites were found in Pyongyang and the surrounding area. These are examples that are believed to be remains of a circumambulation corridor. Seven excavation sites are regarded as having been influenced by northern Buddhism, which are sites located in areas consistent with the route of propagation of northern Buddhism. In particular, as Goguryeo was located adjacent to northern China and adopted northern Buddhism first among the three kingdoms in Korean peninsula, it was taken as the subject of this study by taking the architectural relevance in temples with those of China into account. The circumambulation corridors around pagodas in temples were thus assumed to have been originated thereby. Further, it was also thought that it had been propagated to Baekje and Shilla, and even to Japan as time progressed. This study intended to examine the sites of excavation of Northern Wei of China and Goguryeo which have been regarded as where the propagation of northern Buddhism began.

The analysis method was to use the excavation data as primary data, while studying other research papers and conducting a literature review to supplement the primary data. From the excavation data in particular, the floor plan is the most important data. Additional historical investigation was performed based on the excavation plans.

In order to examine the characteristics and considerations for restoring circumambulation corridors, architectural design content such as the layout of the wooden pagoda, arrangement and ratio of bay,Footnote3 and size and composition of the circumambulation corridor area was considered so that it could be broadly estimated how circumambulation corridors were constructed. By doing so, the possibility to interpret old relics, which have previously been interpreted as rainwater drainage systems or two storied base, as circumambulation corridors, will be presented.

2. Background investigation

2.1. Review of precedent studies

In the literature on Buddhist architecture in the 5th–6th century in China, there was a paper published by Su Bai reporting on the changes regarding the centrality of pagodas (SuBai (宿白) Citation2006), a paper by He discussing the changing process of temple layout(He Citation2010), and a study on the history of Chinese ancient architecture and the scale of foundation of ancient architecture. (Wang Citation2008; Wang Citation2016) However, none of these papers included a full discussion on circumambulation corridors. Only the excavation reports of Si Yan Pagoda and the pagoda at Yongning Temple (IACASS Citation1996) briefly mentioned these corridors.

In studying Goguryeo wooden pagodas, a paper by Lee, Gang-geun attempted a comprehensive study of the research in South and North Korea on the octagonal buildings of the Goguryeo period (Lee Citation2005). A paper by Kim, Jeong-gi included a detailed discussion on the excavation of the Juong Reung temple and others, but circumambulation was not mentioned in that paper. (Kim Citation1991) In Korea, some studies have shown that circumambulation was prevalent in the ancient period (Park Citation2011; Oh Citation2014; Youm Citation2014, Citation2017). Only An Dai Whan raised the possibility of circumambulation facilities in Goguryeo wooden pagodas. (An and Kim Citation2014)

2.2. Periodical back ground

Buddhist architecture in the 3rd–4th century is thought to have mostly consisted of pagoda temples constructed with the pagoda at the center. In some of these pagoda temples, the Buddha statue was enshrined in the pagoda such that the pagoda played the role of the main hall as well. It is believed that at the beginning, the pagoda had a simple layout in which a multi-storied wooden pagoda is constructed at the center with walls or corridors surrounding its square shape(Wei Citation1974).

In the 5th–6th century, a main hall began to be built in the space surrounded by walls or corridors along with the pagoda. In other words, the single pagoda-main hall style became common, in which the pagoda and main hall are constructed together in the center and surrounded by walls or corridors. The circumambulation corridor was confirmed in ruins of temple sites from the 5th–6th century in China, indicating that the circumambulation rituals continued from the 3rd–4th century to the 5th–6th century regardless of changes to the temple layout.

In Goguryeo, Buddhism was introduced by a monk from Former Qin of the Northern Wei, so it is thought that there was a close association with the 16 Kingdoms. However, in contrast to China, Goguryeo temples centered on octagonal wooden pagodas from the 5th century and used a single pagoda-three main halls style, where the main halls were constructed on three sides: the east, west, and north sides of the pagoda. However, based on the examples in China, it is not difficult to postulate that circumambulation rituals were also performed in Goguryeo.

2.3. Circumambulation rituals

Circumambulation as a Buddhist ritual in Buddhist temples started in ancient India as an important means of worship in both Hindu and Buddhist religious practice. In early Buddhism, circumambulation developed as a worship ritual for the stupa, where Buddhist relics are stored. The circumambulation corridor was formed for worship rituals circling around the stupa based on the faith in the relics of Buddha. Sanchi stupa in India, for example (around BC 200), built a double circumambulation corridor around a circular stupa.Footnote4

In the pagoda temples of China, rituals were performed while encircling a square wooden pagoda.Footnote5 In the wooden pagodas of China, there was a tradition of enshrining the statue of Buddha together with Buddhist relics. Therefore, there is a tendency to include both faith in Buddhist relics and faith in the statue of Buddha within the circumambulation ritual. Even after the main hall became a separate building following the 5th century, the tradition to enshrine a statue of Buddha in the pagoda continued.

The main hall also had a Buddha statue located at the center, and the space around it was left empty so as to allow for rituals circling the statue. This tradition continued in later generations as confirmed by the main hall of the Nanchan temple from the Tang Dynasty, the earliest extant Buddhist architecture in China, so the behavior of circumambulation is considered to have been continually maintained in ancient Buddhism in East Asia.(Prakash, Gommans, and Kolff Citation2003)

There are no records of circumambulation in Goguryeo, but according to Samgukyusa, there are records that circumambulation was performed in the Heungruyn Temple of Silla. This record is one piece of evidence that circumambulation was prevalent in the Three Kingdoms period.Footnote6 Rituals of circumambulation continued until present-day Korea, so it remains a time-honored tradition. (Han Citation2014; Oh Citation2014; Youm Citation2017, Citation2014)

3. Circumambulation corridor in ancient Chinese pagodas

3.1. Siyuan temple (思遠佛寺)

The Siyuan Temple (see ) is located in Feng’s cemetery on the top of Xisi Liangshan located in Datong city in the Shanxi province.Footnote7 The temple was constructed in this cemetery by Queen Mother Feng (441 ~ 490), who was the principal wife of Wen Cheng Di(reigned:441–490) of Northern Wei. (Datong Museum Citation2007)

The pagoda site is located slightly south in an area surrounded by a rectangular wall longer north to south. To the north of the pagoda, there is a main hall site, and there is an entrance gate to the south of the pagoda site.

A characteristic of the pagoda site layout is that the pagoda is slightly south of the site and the main hall is located north of the pagoda, in order to install both the main hall and the pagoda. This is understood as a case in which a rectangular outer boundary is made to maintain the centrality of the pagoda while leaving enough space for the main hall to the north.

The total size of the wooden pagoda is 18.2 m × 18.2 m. The arrangement of bay in the pagoda is 5 × 5 bay, where the length of the central bay is 5 m and the rest are 3.3 m. The pagoda can be divided into two parts: a central earthen structureFootnote8 in the center of the pagoda and the circumambulation corridor made by wood outside of the central earthen structure.

The central structure of the pagoda is a 12.2 m × 12.2 m2. To the north of the central structure, there are stairs with a width of around 2 m. This suggests that people were able to climb up into the upper structure of the pagoda. The bay is 3.3 m, so compared to the 2 m-wide stairs, the north side provides space to climb the stairs.

The circumambulation corridor consists of 1 bay, and the spacing between the bay of the circumambulation corridor is 3.3 m. This provides enough space for 2–3 people to walk together. It is constructed to circle the central structure, and there is evidence of brick-pavement on the ground. This means that the environment was formed to allow for circumambulation.

The pagoda is smaller in the Siyuan Temple than in other examples, but it is the earliest example, so it can be postulated that the circumambulation corridor was a typical style at the time.

3.2. Si Yan pagoda

The Si Yan Pagoda (see ) is part of the ruins of the Chaoyang North Pagoda in the Chaoyang County of the Liaoning province. In the ruins of the Chaoyang North Pagoda, there were architectural remains from the early 16 Kingdoms period until the Liao Dynasty (916–1125), as well as the remains of Si Yan Pagoda from the Northern and Southern Dynasty period. (Kim Citation2010) Queen Mother Feng, who constructed the Siyuan Temple, also constructed the Si Yan Pagoda at the palace site of the ancient state of Longcheng in her homeland of Northern Yan. (LSWKY Citation2007; Kim Citation2010)

The pagoda site is at the center of a square space surrounded by walls, and to the north, there are earthen remains which seem like the remains of a main hall, so it is a temple with the single pagoda-main hall style. The size of the area surrounded by walls is around 148.6 m × 148.6 m.Footnote9 Having the pagoda at the center of the square site, even when there is a main hall within the site, suggests that the pagoda was more emphasized than the main hall.

The floor area of the pagoda is 48.6 m × 48.6 m, with a bay arrangement of 13 × 13 bay. The length of the bay in the central structure and circumambulation corridor was diversely constructed, indicating that it was an attempt to solve the complex building structure of pagodas. When the overall composition is examined, it consists of a total of 13 bay: 7 bay for the central structure, 1 bay for the circumambulation corridor, and 2 bay for the hall.Footnote10

The inner bay of the central structure is 2.76 m; the bay of the foundation stone layer surrounding the outside of the central structure is 2.55 m, so the entire length of the central structure is 18.9 m.Footnote11 The inner foundation stone layer of the circumambulation corridor surrounding the central structure was constructed so that it could be seen from the circumambulation corridor. The bays of the foundation stones of the insides of the central structures and circumambulation corridor are different, so it has an inappropriate structure for directly connecting the wooden members between the inner and outer column of the central structure. In other words, the earthen structure of the central structure and wooden structure of circumambulation corridor are made up of different compositions.

The circumambulation corridor is the exterior of the central structure and consists of 1 bay. In contrast to the central structure, the space between the foundation stones of the circumambulation corridor is 4 –4.4 m. Therefore, it is difficult to install a wooden frame which directly crosses between the column at the side of the central structure and the column outside of the circumambulation corridor. The width of the circumambulation corridor reaches 6.6 m, so there would have been difficulty obtaining wooden members which could cross over the width of the circumambulation corridor and bear the weight of the upper structure of pagoda. It is thus believed that another bay of the column may have existed. In the report, the worship passageway of the circumambulation corridor was shown to be 3 m, indicating that the worship passageway was differentiated on the floor of the circumambulation corridor.

Three foundation stones are gathered on the corner of the circumambulation corridor, in other words, in the corner of the pagoda. These are the foundation stones for the supplementary columns to bear the heavy weight conveyed to the corner column. Therefore, it has structural characteristics meant to endure the heavy weight conveyed to the corner area.

On the exterior of the circumambulation corridor, a hall of 2 bays had been installed. The floor of the hall is installed slightly lower than the floor of the circumambulation corridor. On the outside, there are the remains of a wall.Footnote12 There is also an entrance on the center bay of the pagoda. In addition, there are walls installed on both sides of the entrance in order to differentiate from the hall.

If the circumambulation corridor is a space for circling rituals, the hall is believed to be a space for bowing rituals or stationary rituals. Such inferences can be found from the excavation report (LSWKY Citation2007) of Si Yan Pagoda wherein the term, “Yebaedo (礼拜道; the road of worship),” is found, which was mentioned to be similar to the case of the pagoda of Yongning Temple.Footnote13 However, the distance of the bay for the circumambulation corridor is 1 bay and the width is 6.6m, while the hall is 2 bay and the total width is 5.8 m.

Compared to the Siyuan Temple, the Si Yan Pagoda is far larger in overall size as well as in the number of bays. However, the width of the circumambulation corridor in the Siyuan Temple is 3.3 m while the width of the worship passageway in the Si Yan Pagoda is 3 m, so the spatial size of the circumambulation corridor is roughly similar.

3.3. Yongning temple

Yongning Temple (see ) is located in the ancient city of Laoyang from the Northern Wei period, which is 30 km east of the current city of Laoyang.

The Yongning Temple was constructed in AD516 by Lingtaihou(?–528), who was the regent of Northern Wei for Xiao Mingdi (reigned: 515 –528). Then, in AD534, the wooden pagoda of Yongning Temple burned down in a fire. This led to the ruin of the temple.

The pagoda site (see ) is located slightly south in an area surrounded by a rectangular wall longer from the north to the south (212 m × 301m). To the north of the pagoda site is the main hall site (54 m × 25 m). There are also gates on the east, west, and south sides. (IACASS Citation1996)

The arrangement of the bay in the pagoda is 9 × 9; the length of one side of the pagoda is 30 m and the length of the pagoda base is 38.3 m.

The central structure of the pagoda is 7 bay 19.8 m. The outside of the central structure touches the inside of the foundation stone, so the foundation stones are constructed so that they can be seen from the circumambulation corridor. Considering that the space between the bay is always different in the foundation stones layer inside the central structure, it is postulated that there was no need for wooden members to directly connect between the internal column of the central structure and the column in the circumambulation corridor. A Buddhist Niche is installed on the side of the central structure, and to the north, there are foundation stones which look like stairs.

The circumambulation corridor consists of 1 bay with a width of 4.1–4.2 m. The internal foundation stone layer is exposed towards the corridor, and there are traces of a wall on the external foundation stone layer. The width of the circumambulation corridor was actually only around 3 m when considering only the inside of the foundation stones. Therefore, it is similar to the width of the circumambulation corridor of the Siyuan Temple (3.3 m). Considering that there is a foundation stone in the passage area of the corner of the circumambulation corridor, a column would have been installed to that foundation stone, so the width of the passageway in the corner area is reduced to 1.3 m. These supplementary foundation stones installed in the four corners are thought to be a method for dispersing the weight of the upper stories of pagoda concentrated on the corners, as discussed previously.

The circumambulation corridors are built for rituals of circumambulation; however, there would also have been a worship function regarding the statue of Buddha enshrined in the central structure (Yang Citation2007).Footnote14 The location of the stair at the north for going up to the upper level is similar to that in the Siyuan Temple.

4. Circumambulation corridors at the Goguryeo pagoda sites

According to Samgukyusa, after Buddhism was officially introduced to Goguryeo in the late 4th century, Chomun Temple and Leebulan Temple were constructed first, and then, nine temples were built in Pyongyang in AD392. The four temples sites found to date are all near Pyongyang and are known to be ruins from the 5th century.

The Goguryeo temple sites have a single pagoda and three main halls ().Footnote15Footnote16 The main halls were installed either on each side or on the three sides of the east, west, and north with the octagonal pagoda in the center. This style has not yet been found anywhere in China. In addition, the reason for such layout and style is still unknown.

The octagonal shape of the pagoda would have been constructed in an attempt to make a polygonal pagoda closer to a circle like the stupa of India than a square shape. There is no doubt that circumambulation rituals would have been performed in the octagonal wooden pagoda.

There are no clear remains of the foundation stones at the pagoda sites of Goguryeo, so the internal structure cannot be accurately known. In addition, the sizes and styles of the pagoda sites of all of the temple sites are very similar to each other. Therefore, rather than an individual investigation of each pagoda site, it is possible to conduct an overall examination of the four wooden pagoda sites of Goguryeo.

When the sizes of the four pagoda sites are examined, the length of one side is around 7–9 m, and no significant difference was observed. This is seen as a characteristic resulting from having been constructed in a similar region during a similar period. The sizes of the Goguryeo pagodas are close to that of the pagoda at the Siyuan Temple, where the length of one side is 18.2 m ().

Table 1. Wooden pagoda sites of Goguryeo temple.

Table 2. The sizes of the pagodas in Goguryeo (BNRICH Citation2009).

Table 3. Foundation layer detached from the bases in the wooden pagodas in GoguryeoFootnote21

In the pagodas, only the foundation-stone were found, and no members that could be clearly classified as footstone or pillar base stone (礎石) were found. There were also no traces of the central structure of the pagodas, like the cases in China, so it is believed to be built purely of wood.

An important characteristic of the Goguryeo pagoda sites is that around 70 cm~1.15 m is spaced from the basic outskirt of the base, and another foundation layer (基礎列)Footnote17 of 60 ~ 80 cm appears. One document, which believed this outer foundation layer(基礎列) to be a waterspout facility (a rain water drainage facility), is a paper published by Han In-ho in North Korea,Footnote18 and there are other documents(Yoon Citation2002; AIK Citation2003; Tahk Citation2009) in South Korea mentioning waterspout facilities as well. In addition, in BNRICH’s book, the type of rain water drainage for each period is discussed, including the rain water drainage in the Goguryeo wooden pagodas, and it is mentioned that rain water drainage systems even existed in Japan (BNRICH Citation2009).Footnote19

Figure 5. Tosung-ri temple site (Source: BNRICH Citation2009 and author edited).

Figure 8. Cheong-am-ri temple site (Source: BNRICH Citation2009 and author edited).

However, a paper by Kim Jeong-gi refutes this argument. Pointing out the fact that it is not seen in buildings other than pagodas and even in Japan where there is a large amount of rain-water, he argued that it is less likely to be a rain water drainage system but rather the remains of a two storied base(二重基壇) (Kim Citation1991).Footnote20 On the other hand, Kim Dong-hyun thought that it was a sunshade bay (遮陽間) (Kim Citation1998).

The first reason to consider this foundation layer as a circumambulation corridor is that the foundation layer appears only in the wooden pagoda. It would be reasonable to think that an identical foundation layer would appear from other large-sized buildings as well as wooden pagodas of relatively narrower area of the roof, if the rain water has to be flowing over the rainwater drainage. However, such a foundation layer is not found in other buildings, and is only found in wooden pagodas. Therefore, the foundation layer is counted as the foundation layer showing unique characteristics of the wooden pagoda.

Second, no foundation layer for the water channel, ditch, or drainage way was found if the foundation layer was rainwater drainage, which is installed independently around the wooden pagoda.

The third reason is based on the rainwater drainage facilities to be installed longer than the length of eaves from the surface of base. A case corresponding to this can be found from the wooden pagoda of the temple of Horyuji, Japan (). However, the foundation layer of wooden pagoda of Goguryeo is installed separately from the surface of base. Thus, the space between the base and foundation layer is exposed to rainwater.

The above three reasons support the possibility that the foundation layer could be referred to as something other than rainwater drainage. Thus, the foundation layer is inferred as an architectural device to perform rituals of circumambulation.

Considering the importance of the circumambulation ritual, it does not seem reasonable to interpret this outer layer of foundation with no connection to the possibility of the circumambulation.

At all of the four temple sites, this outer foundation layer is not seen in the remains of the buildings other than the pagoda site. In addition, judging from the stone installation method, it is believed that there is a relatively small possibility of it being used as rain water drainage. If this outer foundation layer is not a rain water drainage system, there seems to be no other possibility than it being a circumambulation corridor. Particularly in the Cheongam-ri temple site (淸岩里寺址), this foundation layer of the entrance passage and the outer foundation layer of the circumambulation corridor are connected(). This shows the connection of movement for the circumambulation rituals. One can guess that there could have been a circumambulation corridor inside the wooden pagoda, but details of the interior cannot be known, and it may have been difficult to form a space for the circumambulation corridor due to the internal structure of the octagonal wooden pagoda.

Figure 12. The wooden pagoda at the Cheongam-ri temple site (Source: BNRICH Citation2009 and author edited).

It is not difficult to presume that there were eaves on the first story or additional sunshade to cover this outer area, and that the floors were treated for people to be able to walk around. The width of the circumambulation corridor in the Goguryeo pagoda is narrower than those that have been found in China, but there is sufficient space for at least one person to move. In the case of the Cheongam-ri temple site, the fact that the pillar base(big stone:大石) that supports the sunshade eaves are found inside this outer foundation layer strengthens the presumption that this area is a circumambulation corridor ().

5. Restorative study of the circumambulation corridor

5.1. Circumambulation corridor in Chinese pagodas

The circumambulation corridor in China is installed inside the wooden pagoda, and the floor was paved by brick. For example, in the Siyuan Temple, small amounts of bricks were discovered. In the case of China, the circumambulation corridor consists of the outermost 1 bay of the pagoda, and it is confirmed that the width is 3m or more. The central structure of the pagoda is installed inside the circumambulation corridor. Considering that the main row of the foundation stone layout of the central structure and circumambulation corridor do not correspond to each other, it can be observed that the wooden structure of the central structure and circumambulation corridor existed as separate structures. Internal foundation stones for the circumambulation corridor were attached to the side of the central structure, and foundation stones were also installed outside the circumambulation corridor with the same interval between bay so as to allow for the installation of a crossbeam in the upper area of the circumambulation corridor. Stairs going up to the upper story were located at the north of the interior of the circumambulation corridor. Therefore, it would have been difficult to install a shrine or niche at the north side of the circumambulation corridor. Being able to go up to the upper story from the circumambulation corridor also shows the possibility of a circumambulation corridor at the upper stories. It may have been difficult to reduce the width of the circumambulation corridor of the upper stories, so the method of reducing the size of the central structure of the pagoda would have been used. In addition, it would have been designed for the column and wooden structure of the circumambulation corridor to structurally bear most of the weight from the upper stories. The central structure of the pagoda is seen as playing the role of solidly fixing the framework members and supporting partial weight.Footnote21

5.2. Circumambulation corridor Goguryeo wooden pagodas

Information about the circumambulation corridors of the Goguryeo wooden pagodas can only be speculated upon, because there is insufficient reference material. It is highly possible that the floors of circumambulation corridors in Goguryeo pagodas had exposed foundation layers or had been covered with stones or other materials. The upper areas of the corridors may have been composed of a sunshade to protect them from rain or snow.

The width of the circumambulation corridor is 80 cm in the case of the Sango-ri temple site (上五里寺址), and the Tosung-ri temple site (土城里寺址) and Cheongam-ri temple site (淸岩里寺址) have a width of 70 cm, while Juong reung temple (定陵寺址) site has a width of 60 cm.

The foundation of the pagoda site is evenly distributed. The fact that there is uncovered space between the pagoda base and outer layer of foundation supports the fact that the outer layer of foundation could not be a two-storied pagoda base. If the outer layer were the lower base of the two-storied base, there would not be such space not covered by stones.

The pillar base found at Cheongam-ri temple site, as explained earlier (), is not a regular pillar base of the wooden pagoda, but seems to be a base for an additional roof. There is the possibility that the circumambulation corridor was constructed as an additional passageway. The width of a passageway is 60 ~ 80 cm, and it had the function for people to form rows and perform circumambulation rituals.

Figure 13. Photo of wooden pagoda remains in the Cheongam-ri temple site; (a) Foundation layer (b) Foundation layer and big stone (大石) (Source: BNRICH Citation2009 and author edited).

6. Conclusion

This study presented the concept of the circumambulation corridor in Chinese wooden pagodas and Goguryeo wooden pagodas of the 5th~6th century, and investigated their characteristics as well as the possibility of restoration.

The circumambulation ritual is an old traditional ritual which appears in the stupas of India. Its influence reached China and Goguryeo, and it has been revealed that there was space in pagodas to allow for the circumambulation corridor.

From the pagodas constructed in the 5th~6th century, it was confirmed that circumambulation corridors were installed in the Siyuan Temple, Si Yan Pagoda, and the pagoda of Yongning Temple allowing for circumambulation rituals around the edge of the central structure of the pagoda. The width of the circumambulation corridor was around 3 m, and the floor was paved with bricks or other materials. The wooden structure of the circumambulation corridor was installed separately to the central structure, and a construction method that could bear the weight from the upper stories was employed.

It is difficult to see the outer foundation layer found in the Goguryeo wooden pagodas as a rain water drainage system. If it is not a rain water drainage system, there is no other explanation other than the possibility of it being for a circumambulation corridor. The fact that this outer foundation layer is only found in pagodas supports such a hypothesis. It is postulated that the upper area of the circumambulation corridor would have been covered with a sunshade or roof, and that the floor would have been appropriately paved for circumambulation rituals. The circumambulation corridors in Goguryeo differed from those in China in that they were at the exterior of the building. It is thought that perhaps they were installed outside due to the wooden structure of the octagonal pagoda.

The circumambulation corridors found in Chinese and Korean pagoda sites from the 5th~6th century reflect a background where architectural solutions were needed because circumambulation rituals were important religious events during this period. Thus, it was intended to ensure that the circumambulation corridor was constructed as a ritual space itself in Korea and China during the 5th~6th Century. The results of this study relied on insufficient excavation documents, so further additional studies are needed in the future.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dai Whan An

Dai Whan An earned his Ph.D. in history Korean architecture from the Yonsei University, Korea. He had worked for preservation and surveying work of Korean architectural heritage in Architect’s office from 1997 until 2013. After that, he works in department of architecture, Chungbuk National University. Dr. An’s research focuses on research the preservation of the Korean architectural heritage, production of survey report of architectural heritage, design of Korean traditional buildings. Nowadays, he studies on the relationship with 3D scan data and survey report of buildings, and the restoration of buildings in the excavation site.

Notes

1 Si Yan Pagoda surrounded by a square wall can be seen as the closest form to the pagoda temple style. (Datong Museum (大同市博物馆) Citation2007).

2 This study called the space made inside or outside the pagoda for the performance of circumambulation as “a circumambulation corridor” for convenience. Other studies or documents used various other terms such as 环塔心殿堂式回廊, 殿堂式回廊, 回廊式殿堂 (An and Kim Citation2014).

3 “bay” means “kan” in Korea and “jian” in China, and the Chinese character is ’間’.

4 The Interpretation of the Indian Stupa as Origin of Korea Pagoda, Journal of Architectural History V18 No6, Korean Association of Architectural History, the stupa is mentioned as the “entrance door of railing” is twisted to the turning direction, and it is well known as a mandala expression which signifies circumambulation’ (Lee Citation2009).

5 道世, 法苑珠林, 卷 第 37, 旋繞部 第五 “ 右繞者 經律之中制令右繞” “又三千威儀云 繞塔有五事 一低頭視地 二不得蹈虫 … .” (Dai Shi 668) 玄奘, 大唐西域記 卷 2, 健駄邏國, “ 隨所宗事多有旋繞 或唯一周 或復三匝 宿心別請數則從欲 ” (Xuan Zang, 646)

僧祐 (445 ~ 518) 『弘明集』「理惑論」, “時於洛陽城西甕城外起佛寺, 於其壁畵千乘萬騎繞塔三匝.”

6 Reports that there is content that circumambulation was performed in the Heungruyn Temple in ‘金現感虎’條 of 『三國遺事』(Park 2011)『三國遺事』‘金現感虎’條 ‘新羅俗每當仲春初八至十五日都人士女競遶興輪寺之殿塔爲福㑹 元聖王 代有郎君 金現 者夜深獨遶不息有一䖏女念佛随遶 …

『三國遺事』 “義湘傳敎” 條 “湘 住皇福寺時與徒衆繞塔每歩虚而工 不以階升故其塔不設梯磴其徒離階三尺履空而旋”

『三國遺事』‘賢瑜珈海華嚴’條 茸長寺寺有慈氏石丈六 賢 常旋繞像亦隨 賢 轉靣 賢‘.

7 Siyuan Temple was first investigated by a Japanese scholar in 1931, and was investigated by 大同市博物館 in 1981. (Datong Museum(大同市博物馆) Citation2007).

8 Chinese documents record it as 塔心实体. It is the structure piled up with dirt at the center of the pagoda.

9 Reference: (LSWKY Citation2007 133).

10 Excavation reports calculate the total length of the pagoda as 48.6 m and explain that it consists of 11bay. However, in the excavation plans in the report, the bay inside the walls – i.e. the space between the wall and column – is not calculated as bay. However, when the total length of the pagoda is calculated through the length of each bay or reduced scale length on the plan, the length from the exterior wall to the opposite wall appears to be 48.6 m. It is an area where clear explanation regarding the size is insufficient.

11 Reference: (LSWKY Citation2007 26–28).

12 The length between the column and internal side of the wall (1.95 m) and the breadth of wall (2 m) were deduced from the length on the plan as well as by calculating the length of the internal bay recorded as a total length of 48.6 m on record.

13 Reference: BNRIC Heritage 2009, p90 p.107 “按中国传统古建筑结构特点推测而应存在的第5圈廊柱至第二层台殿堂后檐墻之间, 尚有3米多宽, 应是环塔四周的礼拜道, 供人们绕塔礼佛之用。由礼拜道经正对塔中心的四面漫道拾级而下, 便到了第二层台基上的殿堂。”

p128 ‘思燕佛图塔身及刹顶饰件, 亦应如 ≪洛阳伽蓝记 ≫ 等史籍对洛阳永宁寺塔所描述的, 四面有户有窗, 檐角垂金铎, 上有金刹, 安置宝瓶等。塔身上还设有佛龛, 龛內外布置泥塑佛、菩萨、飞天、力士等造像, 以及莲花、飞禽、异兽等 佛敎装饰题材。其建筑结构、装饰风格等, 可参阅洛阳永宁寺塔的复原, 在此不细述。

思燕佛图与四周殿堂之间有 3 米多宽礼拜道, 供人绕塔礼佛。殿堂建在第 2 层台上, 进深 2 间, 每面正对塔中央的一间作慢道, 两侧筑有土墙,其他各间则不设隔断墙。殿堂是僧侶坐禅、诵经之所。这种平面布局形式与北魏大同云冈二期中心塔柱窟和辽宁义县万佛堂西冈1号中心柱式石窟很相似, 而洛阳永宁寺塔却未发现殿堂式建筑。’.

14 Reference; (Yang Citation2007), “There is the possibility that worshippers put emphasis on rituals performed regarding the statue enshrined inside the wooden pagoda rather than the exterior of the pagoda .”

15 Reference (BNRICH Citation2009, 22), it is written that Temple in Tosong-ri built late 4th century following the assertion of Il Ryong, Nam (Nam Citation1987). However Kim, Jeong gi said that it is difficult to select the assertion of Il-ryong, Nam which saw the establishment of the Tosung-ri temple site in AD394 (Kim Citation1991).

16 Only the east and west main halls were excavated, and the building site to the north was not investigated. There is a high possibility that the main hall existed to the north.

17 It is described as a outer foundation layer following the reference (BNRICH Citation2009; Kim Citation1991) so “outer foundation layer” is used for convenience. As can be seen in –, it indicates the area where layers were made by closely stacking stones.

18 The study of Lee, Gang Keun (Lee Citation2005, 17) quoted the study of Han, Inho, “Han said that there were four similarities of “two storied base,” “rain water drainage,” “digging a deep stone foundation of whole base style,” and “no foundation stones for central structure.” (Lee Citation2005; Han Citation1988).

19 Reference: (BNRICH Citation2009, 224–226).

20 Reference (Kim Citation1991, 21–22) was certain that it was not rain water drainage, as it was not found in other building structures nor in Japan, where there is a large volume of rain water.

21 Reference: (BNRICH Citation2009).

References

- Abe, S. 1990. “Art and Practice in a Fifth-Century Chinese Buddhist Cave Temple.” Ars Orientalis 20: 1–31. Freer Gallery of Art. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4629399.

- AIK (Architectural Institute of Korea). 2003. History of Korean Architecture. Seoul: Kimindang.

- An, D. W., and S. W. Kim. 2014. “Possibility of Circumambulation Facility of the Octagonal Pagoda of Goguryeo Buddhist Temple Site in the 5th Century.” Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea V30 (N6). The architectural Institute of Korea. http://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/ArticleDetail/NODE02428170.

- BNRICH (Buyeo National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage:夫餘國立文化財硏究所). 2009. The Comparative Study of Wooden Pagoda in Fareast Asia(韓中日 古代 寺址比較硏究 木塔篇). Buyeo: Buyeo National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage.

- Daishi (道世), 668. Fayuan Zhulin V37, (法苑珠林), 卷 第 37, 旋繞部 第五.

- Datong Museum (大同市博物馆). 2007. Datong Northern Wei Fangshan Siyuan Buddhist Temple Site Excavation Report (大同北魏方山思远佛寺遗址发掘报告),文物2007年4期, Datong.

- Han, I. 1988. “Several Questions about Pagoda Sites of Goguryeo(고구려 탑터에 관련한 몇가지 문제).” History of Science (력사과학), North Korea, (88–2).

- Han, S.-G. 2014. “A History and Status of Circumambulating a Pagoda in Korea.” 淨土學硏究 (21). 淨土學會. http://www.earticle.net/Article.aspx?sn=229686

- He, L. (何利群). 2010 11. Research of Cave Temples; Archaeological Study of Buddhist Temples from the Northern Dynasties to the Sui and Tang Dynasties(石窟寺研究 北朝至隋唐时期佛教寺院的考古学研究). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe (文物出版社).

- IACASS (Institute of Archaeology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences:中国社会科学院考古研究所). 1996. Northern Wei LuoyangYongning Temple-1979-1994 Architectural Excavation Report (北魏洛阳永宁寺-1979~1994年考古发掘报告). Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House (中国大百科全书出版社).

- Jurgen, N. 2012. Narmadaparikrama–Circumambulation of the Narmada River; on the Tradition of a Unique Hindu Pilgrimage. Leiden: Brill Academic Pub.

- Kim, D. H. 1998. 法住寺捌相殿修理報告書, 102. Seoul: National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage of Korea.

- Kim, J. G. 1991. “Outline of the Excavation Report on the Temple Sites of Juong Reungsa and Tosongri of Goguryeo.” Journal of Art of Buddhism. (10). Museum of Dongkuk University.

- Kim, S., and W. Kim. 1985. “History of Design of the Early Buddhist Architecture in Korea.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Michigan

- Kim, Y.-M. 2010. “Eternal Ritual in an Infinite Cosmos: The Chaoyang North Pagoda (1043-1044).” Doctoral Dissertation, Harvard University. ISBN: 9781124081373; https://hollis.harvard.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_proquest613689957&context=PC&vid=HVD2&lang=en_US&search_scope=everything&adaptor=primo_central_multiple_fe&tab=everything&query=any,contains,Eternal%20Ritual%20in%20an%20Infinite%20Cosmos:%20The%20Chaoyang%20North%20Pagoda%20(1043-1044)

- Kim, Y.-M. 2017. “Virtual Pilgrimage and Virtual Geography: Power of Liao Miniature Pagoda(907-1125).” Religions 8. doi:10.3390/rel8100206.

- Lee, B. G. 2005. “A Study on the Excavation Sites with Octagonal Shape of Building in Goguryo.” Prehistory and Ancient History. (23). Institute of Prehistory in Korea(韓國古代學會).

- Lee, H. B. 2009 12. “The Interpretation of the Indian Stupa as Origin of Korea Pagoda.” Journal of Architectural History 18 (6). Korean Association of Architectural History.

- LSWKY(Liaoning-Sheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo:辽宁省文物考古研究所) and Chaouang-shi Beit Bowuguan, (朝阳市北塔博物馆). 2007. Chaoyang Beita; Kaogu Fajue Yu Weixiu Gongcheng Baogao (朝阳北塔-考古发掘与维 修工程报告). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe(文物出版社).

- McBride, R. D. 2002. “Buddhist Cults in Silla Korea in Their Northeast Asian Context.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles

- Nam, I. R. 1987. “About the Site of Goguryo Temple in Tosong-Ri Bongsangun Hwanghaebukdo.” Archaeological Study of Chosun (4): 8~13, North Korea.

- Oh, K. 2014. “Woljeongsa’s Eight-Angle Nine-Story Stone Tower and Korea’s Tower-Turning.” Journal of Seon Studies(韓國禪學) 37: 149. The Korean society for Seon studies(韓國禪學會). http://www.dbpia.co.kr/Article/NODE02457919.

- Park, E.-A. 2011. “Aspects and Characteristics of Turning the Tower of Fortune in Gamtong Kim-Huyngamho of Samgukyusa (『三國遺事』感通‘金現感虎’條).” The Culture of Sulla. (32). Dongguk University Silla institute.

- Prakash, O., J. J. L. Gommans, and D. H. A. Kolff. 2003. Circumambulations in South Asian History: Essays in Honour of Dirk H.A. Kolff. Boston: Leiden.

- Liu, S. 1995. “Art, Ritual, and Society: Buddhist Practice in Rural China during the Northern Dynasties.” Asia Major Third Series 8 (1): 19–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41645512.

- SuBai(宿白). 2006 06. 梵宫- 梵宮-中國佛教建築藝術 漢地佛寺布局. 上海辞书出版社. 2006. 06.

- Tahk, K. B. 2009. “Rain Drainage of Ancient Wooden Pagoda in Korea.” MunHwaJae 42 (2): 04–39.

- Wang, E. Y. 1997. “Pagoda and Transformation; the Making of Medieval Chinese Visuality.” Doctoral Dissertation, Harvard University. ISBN: 9780591303902; https://hollis.harvard.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_proquest304345530&context=PC&vid=HVD2&lang=en_US&search_scope=everything&adaptor=primo_central_multiple_fe&tab=everything&query=any,contains,Pagoda%20and%20transformation;%20the%20making%20of%20medival%20Chinese%20visuality&sortby=rank&offset=0

- Wang, G. X. 2008. 中国古代建筑基址规模研究. 中国建筑工业出版社.

- Wang, G. X. 2016. The History of Buddhist Architecture in China(中国汉传佛教建筑史). Tsinghua University Press.

- Wei, S. (魏收). 1974. Wei Shi Volume 114(魏书 114卷), and Shi Lao Zhi Volume 5(释老志 5卷), 3029. Zhonghua Bookstore(中华书局).

- XuanZang, 646(玄奘). Datang Xiyuji Volume 2, Jianhuoluguo(大唐西域記 卷2, 健駄邏國).

- Yang, E. G. 2007. “A Study of Clay Figures from the Northern Tower in Chaoyang, Liaoning Province.” Korean Journal of Art History. (256). Art History Association of Korea.

- Yoon, J. S. 2002. New Edition Korean Architecture. Seoul: Seoul National University Press.

- Youm, J.-S. 2014. “A Consideration on Structure of Buddhist Tower(Pagoda) and Tabdori(Go-round Pagoda) - Focusing on Formation Background of Buddhist Tabdori and East-Asian Change.” Journal of Seon Studies(韓國禪學) 37: 121. The Korean society for Seon studies(韓國 禪學會). http://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/ArticleDetail/NODE02457918.

- Youm, J.-S. 2017. “A Study on Origin of Buddhist Tabdori and Its Korean Development.” Won-Buddhist Thought& Religious Culture (73): 151–184. http://www.dbpia.co.kr/Article/NODE07250072