ABSTRACT

This study considered how to secure authenticity and integrity in the restoration of wooden architectural heritage and establish the principles for restoration, by tracing the process to determine the restoration period of Korean Buddhist temples using the source materials. It analyzed the features by type of source materials and the data utilized in restoration via the case of restoration of Naksansa Wontongbojeon Hall and looked into the relation between the process that the time point of restoration is determined and the source materials. As the restoration period was determined as early Joseon, buildings established from late Goryeo to early Joseon which have been existing so far were used as the useful source materials in determining building ways to preserve a style of Wontongbojeon Hall. Among the wide range of source materials, the discovered data and pictures as well as current situation were the most influential factors in determining the restoration period as early Joseon. In addition, it was inevitable that current requirements different from the past, including function and purpose of restored buildings, the physical status of surroundings, etc., had to be utilized as the source materials for this study. Therefore, correlation between the restoration period and source materials could be determined because the source materials played an important role in determining the restoration period which also determined the use of source materials. Such a process of restoration implies continuity of the value of lives in the past to the future while securing the principles of restoration, authenticity and integrity.

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of study

In terms of restoring Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall as the building in previous period, which has been through a number of destroy and rebuilding, and lastly restored in 1953 and burned out in 2005, this study was to look into the process of determining the restoration period and building styles based on the various source materials and seek for meaning of the process as one of the restoration methods. At this point, restoring as the building in the previous period means restoring as the building of which complete shape is unknown in present. Restoration refers to the process to infer the shape and style of building as well as the creation based on history. Therefore, the restoration process is significant in terms of methodology. The primary objective of restoration process is to secure authenticity. Jukka (Citation2006) Before the fire (2005), this building had been restored in 1953 and has remained in memory of people so far. After the process of restoration, Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall was restored as the central hall of Buddhist temple in early Joseon. It was not restored as the building from 1953 to 2005. That is to say, not considering the “age-value[alterswert]”. (Riegl Citation1903), the building was renewed as the representative in the early Joseon. So given that the central halls of Buddhist temples in early Joseon were been few found in present, it was necessary to secure the authenticity of the buildings in that period by finding out the representative prototype in the early Joseon. The second objective of restoration was to secure historic integrity. In The Principles for the Preservation of Historic Timber Structures (Citation1999) it is said that “the aim of restoration is to conserve the historic structure and its loadbearing function and to reveal its cultural values by improving the legibility if its historical integrity, its earlier state and design within the limits of exiting historic material evidence, as indicated in articles 9–13 of the Venice Charter”. In other words, restoration was to secure integrity of the central halls of historic Buddhist Temples in terms of historic and cultural value in the present time point. Likewise, the restoring process of Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall was considered as one of the restoration methods, in order to secure authenticity as well as integrity of cultural heritage.

Naksansa built by the Buddhist monk Uisang in 671, is one of the 4 representative shrines of Guanyin(觀音) in Korea. Since its establishment, it has been known as the historic and cultural value where a number of believers in Buddhism and tourists visit as it is located in one of the eight famous spots in Eastern Area of Korea(關東八景) and has a number of historic events and stories. Therefore, restoration of the central hall as the most important structure in the Buddhist temple has its significance in terms of history, culture, architecture and tourism.

Given that Korean traditional architectures put stress on relationship with surrounding sites and buildings, not on the existence of single building, it was the restoration of relationship between Naksansa and its entire surroundings. Furthermore, in many cases in Korea, after wooden structures were greatly damaged to the point of restoration or destruction, they were rebuilt in the same or a nearby location, in processes variously called “renovation,” “rebuilding,” etc. In such cases, the resulting building differs in form from the original, whether it differs in size or form in accordance with the situation at the time of the construction.

For the restoration of wooden architectural cultural properties in the Eastern society, there have been frequent reconstructions and repairs of timbers in its history, making difference from restoration of stone buildings in the Western society in judgment of authenticity. Although value of timbers over time is not deniable, it is noted that the shapes and styles preserved and restored in the Eastern society value certain functions and continuity of meaning more than others. It is because of continuing culture from the past such as Buddhist, scenery and local cultures.

1.2. Research target and methodology

The central halls of Buddhist temples that have been in existence so far were established in late Joseon. Meanwhile, the reason for selecting the restoration of main Buddhist buildings in early Joseon Buddhist temples as the target of this study was because the characteristics of this category of building differ from pre-early Joseon and late Joseon restorations. Despite the small number of existing buildings, the early Joseon period potentially includes various types of source material, including excavation material.

The sources in which the restoration process was recorded include Jun-Hyung Bae’s doctoral thesis (Bae Citation2016); Seung-Nam Lim (Hyungo)’s study (Lim Citation2012)Footnote1; and the Office of Yangyang-gun’s report (Yangyang, Citation2007). There are also records of the source material used for the restoration, including the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage’s excavation report of Naksansa and studies by Sang-Kyun Lee (Citation2009) and Yong-Un Han’ book (Han, Citation1928), respectively. The source materials listed above include information about the lives of present people who are alive today while using the Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall, which influences determination of the restoration period.

As the first step for conduct of study, we examined the types and characteristics of source material used during the process of restoration planning for a common excavation site. Second, we then examined the characteristics of the early Joseon restoration period. Third, we expected that the methodology of utilizing source material for the main Buddhist building could be expanded to propose a methodology for establishing source material for excavation sites more generally.

Such a restoration process of architectural heritage has been used frequently and known to us. However, in general, a comprehensive discussion on how to select the restoration period of architectural heritage to secure its integrity and authenticity and to keep its continuity, and on how to utilize source material, is not yet to be realized clearly. Because, the restoration period would be determined by several source material which are connected to each other via several contexts in the discussion thus a single material cannot be employed for the determination of the restoration period.

This study intended to secure integrity, authenticity, and continuity of an architectural heritage by comprehensive and specific examination on the determination of restoration period and utilization of source material to solve interlinked issues therein in the actual process of restoration of Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall.

2. Determining the restoration period and material utilization for the restoration of a main buddhist building

2.1. The process of selecting the restoration period and source material during the excavation site restoration process

As mentioned above, restoring a structure means building a new structure that is as similar as possible to the structure that has been lost. Therefore, the more information that is available regarding the original form of the structure, the more accurate the restoration can be. However, due to the inevitable lack of information in this regard, various source materials are found in relation to both similar structures and to the structure in question. Restoration is then undertaken based on the information gleaned from these various materials.

The second unique process that must take place in the restoration process is the selection of the restoration period. Particularly in the case of main Buddhist buildings in Korean Buddhist temples, this task is even more vital as such buildings tend to have been built and rebuilt over many periods in the same or a similar location, and in many cases, each period’s structure differs in form and size from what has gone before.

In terms of the order of the restoration process, the restoration period is decided after the source material on the structure to be restored has been collected and analyzed. A period should be selected for which there is a large volume of varied and accurate source material to ensure an accurate restoration. It is because the integrity and authenticity of restoration also increase accordingly.

Once the restoration period has been decided on, the source material is recategorized according to the period selected, so that more emphasis can be placed on the material from the period of restoration. As the material moves farther away from the period of restoration, its usefulness decreases. Source material is also categorized based on the amount of repetition and accuracy, since, in attempting to use more accurate material, those materials that are repeated tend to be selected.

During this process, however, there is an inevitable lack of information regarding some aspects of the restoration. In such cases, material is collected from similar structures to supplement this lack. Various types of similarity, such as in restoration period, structural function, size, form, etc., can be selected and these types of similarity and the range of material are adjusted during the restoration process.

In conclusion, in order to undertake restoration, it is necessary to collect source material. Moreover, the selection of source material and the restoration period impact each other and cannot help but be important standards for selection. This standard for selection is intended to secure the authenticity of wooden architectural cultural properties by using the almost perfect data.

2.2. Types and characteristics of the source material

2.2.1. Excavation material

Excavation material is based on the ruins and relics from the excavation site, and is perhaps the most important source material for the restoration plan. The composition of buildings and the floor plan of the structure can be identified by interpreting the location of stone relics such as cornerstones, foundation remains, foundation stones, etc. If there is material at the excavation site from the restoration period, it may be the only evidence of the physical characteristics of the given structure. More specifically, the type, cut, size, and form of the stone may be observed, while the circumstances that pertained at the time of the structure can be inferred from the excavated relics.

2.2.2. Picture material

Picture material is the only source that visually shows the upper portion of the structure such as its elevation, roof, etc. In particular, when this picture material comprises an accurate and professional contemporaneous depiction of the original structure, it can be used as an important material for restoration.

However, picture materials are not without their flaws: based on the artist or the period in which it was drawn, some parts of the structure may have been omitted or altered. Additionally, when the picture was not drawn on location during the restoration period, or in cases where the period depicted cannot be determined, misunderstandings in interpretation may occur.

Therefore, only by understanding the forms and content of similar pictures by the same artist can drawings be used as source material for restoration. In addition, the contents need to be understood more accurately by connecting them with other source material, while an additional disadvantage is that, even in cases where there are many different pictures of the same subject, they must go through a selection process.

2.2.3. Literature material

As literature material from the restoration period records the circumstances of the time, it has an important value. In particular, descriptions of dates or relationships with other structures, numerical expressions, or descriptions of color are advantages that pertain solely to literature material. However, as this material is not visual, it is often difficult to realize its descriptions through restoration. In addition, similar to picture material, it has the disadvantage that in some cases it is difficult to gauge its accuracy.

2.2.4. Photographic material

The advantage of photographic material is that it much more accurately expresses the form and color of the structure than other source material. Therefore, in many cases, it is the most important material for the restoration of a structure. However, as photography was only invented approximately 100 years ago, it does not apply to restorations that pre-date that time.

2.2.5. Material on existing structures of the same time period, or on similar structures

Material on existing structures of the same period or on similar structures does not relate directly to the structure to be restored, but to structures that are considered similar in some way and, as such, are used as targets for comparison based on their temporal and functional similarities.

However, since this is the only material that directly or visually shows all the parts required for a structure, we can say that it is of high value in supplementing those aspects of the restoration that other source materials cannot fill. However, as the restoration plan can be changed based on choices regarding the range of cases to be referred to or regarding which material to use for the restoration, sufficient deliberation is required.

2.2.6. Current status material for restoration

Restoration of wooden architectural cultural properties is not the replica of the past. Current status (physical situation) of excavation site surroundings is different from the past. Restoration is not the matter of single building but of the relation between the changed current status of surrounding sites and the restored building. These aspects should be based on the current status material in existence.

In addition, the meaning and function required for the restored building are inevitably changed from the past. As mentioned earlier, significant historic and cultural value pursued by a number of believers in Buddhism and tourists should be included, differing from the meaning given by the administrator. The restored buildings also need data for historic, social and cultural current status.

People in charge of restoration based on the data make a value judgment on the current status material. The buildings that have been restored based on the current status data including surrounding sites, function and purpose of the building to be restored and requests by the user become to have continuity to make a new correlation with present people and maintain the lives of those people.

3. Source material for the restoration of the naksansa wontongbojeon

3.1. Summary of the naksansa wontongbojeon (洛山寺 圓通寶殿)

3.1.1. The history of naksansa

Naksansa was founded in 671 by Great Buddhist Priest Uisang (義湘大師). After undergoing numerous events of damage and rebuilding, in 1467, during the Joseon period, the Buddhist temple was reconstructed, and in 1592 most of its structures were destroyed by fire during the Japanese invasion of Korea (壬辰倭亂). It was reconstructed once more in 1631, but in 1777, all the temple halls, excluding the Wontongbojeon, burnt down once more and it was during this period that the title Wontongbojeon was first used. In 1854, the Wontongbojeon was repaired, but the entire Buddhist temple burnt down in 1950 during the Korean war and was reconstructed in 1953. Finally, in 2005, many of its structures, including the Wontongbojeon, were lost to fire. Material was then gathered through excavation and the Wontongbojeon was restored once more in the form of the early Joseon period.

3.1.2. Location of naksansa wontongbojeon

Naksansa includes Obongsan Mountain (五峰山), which touches its eastern coast and the area below it adjoining the sea. Unusually, it is surrounded by the Obongsan Mountain fortress so that the earthen ramparts and gate overlap with the territory of Naksansa.

Naksansa is located on a large plot that is divided into numerous areas – the Wontonbojeon area (圓通寶殿 地域), the Haesu Gwaneum statue area (海水觀音像地域), the Bota-jeon area (寶陀殿地域), the Uisang memorial hall area (義湘記念館地域), the Hongnyeonam Hermitage area (紅蓮庵地域), etc. –, while Naksan Beach Hotel and Naksan Youth Hostel lie on the outskirts of the Buddhist temple (See ) (Lim Citation2012).

The area in which the Wontongbojeon is located served as the main Buddhist building from early times. Due to its location on a ridge, it has characteristics that differ from other Buddhist temples, which are generally located on flat land or in valleys. The Wontongbojeon is particularly unique in that it is surrounded by a wall called the Naksansa Wonjang (垣墻)Footnote2

As can be seen in , before the fire, structures such as the Beomjonggak, Gohyangshil, Museoljeon, Geunhaengdang, Chwisukeon, Muidang, etc., were placed around the Wontongbojeon. This placement was established during the restoration of Naksansa in 1953. As shown in , the placement of structures surrounding the post-fire Wontongbojeon restoration differs entirely from the placement of structures of Binillu, Eunghyanggak, Jeongchwijeon, and Seolseondang. This is because, during the post-fire restoration, it was decided to place the structures in accordance with the early or late Joseon period (Cityhall of YangYang County Citation2007).Footnote3

After the fire, various discussions took place regarding whether to restore the Naksansa Wontongbojeon to its placement before the fire, as shown in , or in a new placement. It was ultimately decided to excavate in areas that had already been lost. During the excavation, various materials were gathered for the restoration and the restoration period was decided.

3.2. Source material for the restoration of naksansa

3.2.1. Excavation material

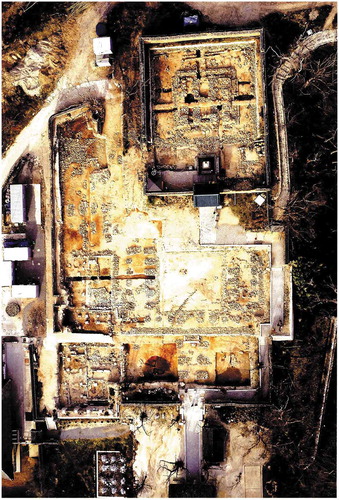

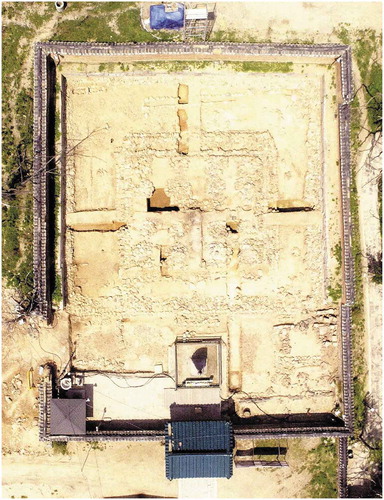

After its destruction by fire in April 2005, two excavations took place in Naksansa from June 2005 to December 2006. During the first excavation, the Wontonbojeon area was thoroughly examined while other areas were merely checked for the existence of relics. During the second excavation, areas around the Wontongbojeon were excavated for restoration and an excavation investigation report was then composed ( and ) (National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage Citation2008).Footnote4

The excavation layers of the Wontongbojeon were divided into five stages (). The oldest layer (stage 5) had relics from the late Goryeo period; the size of the stylobate was 14x10 m and the structure size (i.e., the distance between the foundation remains) was 3 × 2 bays with 10 m to the front and 6.5 m to the side. Compared to the structure locations in later periods, it was weighted toward the north.

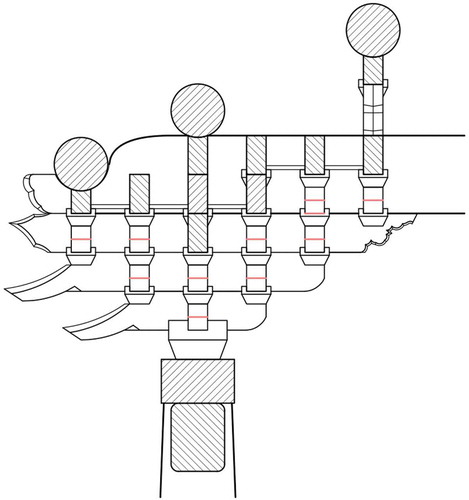

Stage 4 comprised relics from the early Joseon period (). The size of the stylobate was 14x14m, while the size of the bays increased to 3 × 3 with 10 m to the front and 10 m to the side. There were also four internal pillars. Compared to Stage 5, it had expanded south, and changed in form from a rectangle to a square. The main bays are shown in and .

Table 1. Chronological table of the excavation site.

Table 2. Comparison of stage 4 excavation site and planned floor plan structure size (3x3 bay).

Stage 3 comprised relics from the latter Joseon period. While the stylobate was 15.1 × 11.5 m and changed to a long rectangle from east to west, the excavation suggested that it was highly likely that the existing foundation remains had been reused, meaning its floor size was likely to be the same as in the previous period. There were four internal pillars.

Stage 2 comprised relics from the late Joseon period. The stylobate was reduced to 13x11m in size, while the structure size changed to a rectangle of 10.2 × 7.8 m. There were four internal pillars.

Stage 1 comprised the remains of the structure that had existed from 1953 to 2005. The stylobate was 13 × 11.2 m and was estimated to comprise the same stylobate as that used in stage 2, which was almost the same as the size being reused. The size of the structure was the same as stage 2 at 10.2 × 7.8 m. However, unlike the four internal pillars at stage 2, there were only two pillars behind the Buddhist altar, meaning that two pillars were omitted from in front of the altar to make better use of the space.

3.2.2. Picture material

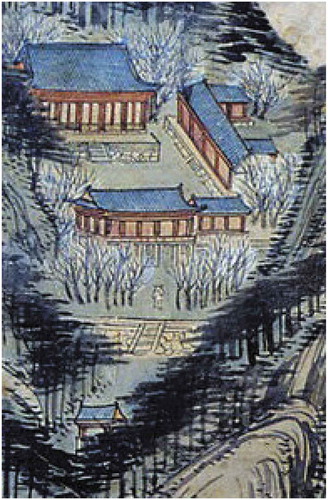

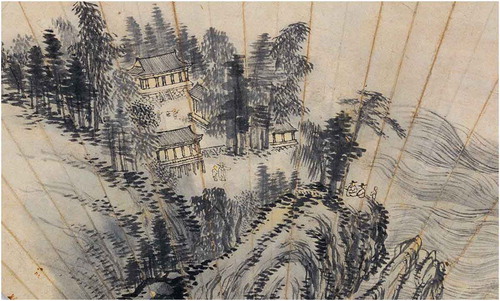

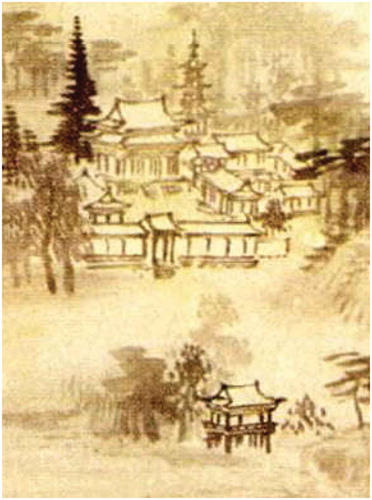

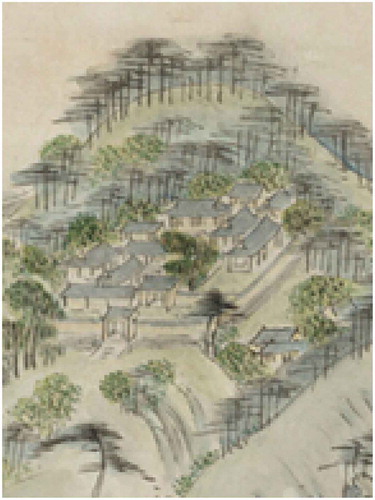

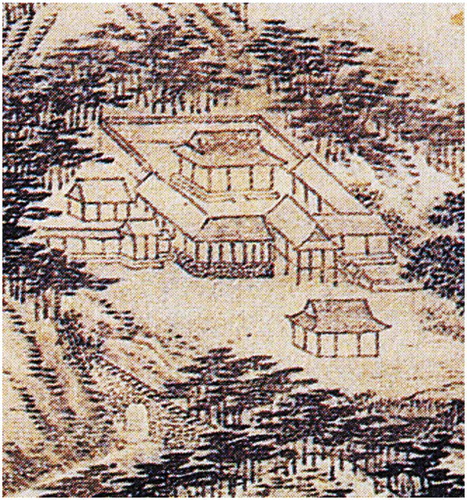

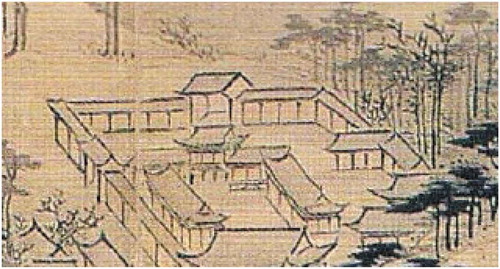

There are many pictures from the Joseon period that feature Nakasansa as the background. Of these, approximately 10 are by famous artists. The Naksansado () by Gyeomjae Jeong Seon (謙齋 鄭敾) is estimated to date from 1753 and comprises an aerial view of Naksansa from the south. Jeong Seon also painted another picture of Nakasansa ().

The picture by Yoo Seong Kim () is estimated to date from 1764 and depicts a scene of Naksansa from a low altitude from the southeast. What is characteristic about this picture is that it was painted in Japan. While the exact period of the Naksansado () painted by Yun Gyeum Kim (1711–1775) is unknown, this is the picture that depicts the most structures. The Naksansado of Hong Do Kim (), a part of the Geumgangsaguncheop (金剛四郡帖), was created in 1788 and, similar to that by Jeong Seon, is characterized by its aerial view from the south. The Naksansado of Ha Jong Kim (), a part of Haesandocheop (海山圖帖), dates from 1815. Unusually, it depicts Naksansa from the north looking south. In addition to these, there are also pictures by Heopil (許佖) ()and Geoyeondang (居然堂).

Examining these pictures, one can see that although they all depict the Naksansa, the depictions differ in terms of the number, placement, and form of the structures. Thus, controversy regarding which picture depicts Naksansa most accurately is inevitable.

3.2.3. Literature material

Although numerous literary sources related to Naksansa exist, material that describes the Wontongbojeon from an architectural perspective is almost nonexistent. The material that most closely approaches architectural expression is the Geonbongsageup Geonbongsa Malsa Sajeok (乾鳳寺及 乾鳳寺 末寺史蹟), which was written in 1928, and in which it is recorded that there were “9 rooms in Wontongjeon (圓通殿), 6 rooms in Yeongsanjeon (靈山殿), 6 rooms in Yongseonjeon (龍船殿), 3 rooms in Daeseongmun (大聖門), 12 rooms in Eunghyanggak (凝香閣), 49 rooms in Seolseondang (說禪堂), 8 rooms in Binillu (賓日樓), 3 rooms in Jogyemun (曹溪門), 6 rooms in Cheonwangmun (天王門), 1 room in Beomjonggak (梵鐘閣), 4 rooms for Byeonso, 1 room for Uisangdae (義湘臺), for a total of 108 rooms.” Therefore, from this literature material, it can be determined that the Wontongjeon consisted of nine rooms.

3.2.4. Joseongojeokdobo (朝鮮古跡圖譜)

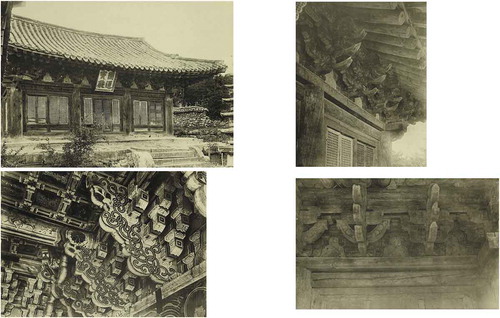

The Joseongojeokdobo comprises a series of 15 books published between 1915–35, and contains photographs of most of the ancient sites investigated at that time, including Naksansa Wontongbojeon. These are the oldest photographs of the site, and are particularly valuable as they comprise photographs from an architectural investigation. They depict structures corresponding to the stage 2 excavation material, and the architectural form of the Wontongbojeon that appears in these pictures is from the late Joseon period ().

3.2.5. Material on wontongdojeon before the fire

Many materials on Wontongbojeon can be found from the period 1953–2005, including floorplans, pictures, and excavation material. The excavation material corresponds to stage 1, which is the most recent structure.

3.2.6. Similar existing structures

The material from similar existing structures is not directly connected with Naksansa Wontongbojeon. Therefore, we can say that the range of existing structures with similarities to Naksansa Wontongbojeon vary according to the time period, function, size, form, etc.

From the perspective of time period, there are almost no similar structures from the same time period as the Naksansa Wontongbojeon. Buildings with a similar function as the main Buddhist building include the Sudeoksa Daeungjeon (修德寺大雄殿), Bongjeongsa Geungnakjeon (鳳停寺 極樂殿), etc. However, if the time criterion is expanded to the late Joseon period, many structures with similar functions and floorplans, such as the Beopjusa Wontongjeon (法住寺 圓通寶殿), can be found. Thus, ultimately, the number of similar existing structures that can be used as source material changes based on how one defines the range of similar existing structures. This means that the source material of similar existing structures must be reinvestigated once the restoration period has been selected to determine an appropriate range.

4. Restoration period and usage of source material in the restoration of the naksansa wontongbojeon

4.1. Decision on the restoration period

As mentioned above, restoring a structure means rebuilding it in the form in which it existed in a previous period. However, the Naksansa Wontongbojeon existed over five periods, and the excavation material showed that the structures differed in size during each period.

The decision regarding the restoration period had to take first priority, in accordance with guidelines that the restoration should be conducted in a manner appropriate to the purpose and meaning of its restoration.

These guidelines appeared in the “Report of Repair and Restoration of Naksansa Wontongbojeon” as follows:

“2. Repair Guidelines

A. The Buddhist main building is to be restored based on the preliminary excavation material from the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. 나. Planning must be made with reference to old books such as Joseongojeokdobo, and must reflect the views of the Naksansa chief priest who is the manager of the Wontongbojeon.

C. Restoration must be made in consultation with the restoration advisory committee and the related member of the Cultural Heritage Committee” (Lee Citation2009).Footnote5

Decisions on which source material were to be used and in what way were determined following these guidelines. In order to make a selection, work first had to be conducted to determine what material existed.

Examining the guideline, the principle office determining the restoration period was the Naksansa Building Restoration Advisory Committee, who were granted this authority by the Cultural Heritage Committee and related cultural heritage committee members. They not only participated in the selection of the restoration period, but also discussed and consulted on the overall restoration process, including the form of the restoration structure. That is, in the analysis of source materials and selection of restoration period, this committee played the biggest role from the academic perspective, as well as from the perspectives of historical, cultural, and technical value.

The second main principle was the chief priest of Naksansa. He participated in the decision on the restoration period as the agent who actually managed and operated Naksansa. His role was thus related to the management and future development value of Naksansa as its actual user. Administrators including the chief Buddhist monk requested for the oldest style enabling the function of a contemporary Buddhist temple. It was a measure to accord historicality in addition to the functional request to use the restored Buddhist temple. The opinion of the administrator of Naksansa was believed to be about the choice of current status material, which plays a role in ensuring continuity of lives of present people.

Examining the material for restoration, excavation materials and books such as the Joseongojeokdobo were discussed. While these materials had to be used in the overall process of restoration, as mentioned earlier the excavation material was prioritized and old literature and pictures were then used to supplement gaps in this material.

Through these many processes, the decision was made to restore the building to an early Joseon structure. The most important factor in this decision was the excavation material from stage 4 (early Joseon period).

As early Joseon was selected as the restoration period, the range of material on similar existing buildings had to be set and supplemented through reinvestigation. As only some of the similar existing structures were required as restoration material, only those needed to be reviewed.

4.2. Usage of direct source material of wontongbojeon

Once the restoration period had been decided, the issue of which material from amongst that gathered would be used and in what way had to be resolved. In this section, we cover the usage of source material directly related to the Naksansa Wontongbojeon.

4.2.1. Usage of excavation material

The excavation site of the Wontongbojeon, like the excavation sites of most main Buddhist buildings, comprises many layers in the same location. That is, during the five-time periods from the Goryeo period to modern times, Wontongbojeons of different sizes have been constructed. Of those excavation materials, stage 4 material from the early Joseon period, which was the excavation time, was selected for use. Thus, the restoration differed in form from the form of the Wontongbojeon immediately preceding the fire. Besides, the period of stage 4 was also estimated to be the most thriving period of Naksansa (). (City hall of YangYang Citation2007)

If we examine this in more detail, from the stage 5 relics, which are the oldest from the Goryeo period, a structure was discovered with three bays in the front and two bays in the side.() This structure was very small and, from a structural perspective, unbalanced and therefore not suitable for use as source material for restoration (Si Citation2004).Footnote6 Therefore, we can infer that the restoration was made using the relics found in the next period (stage 4), corresponding to early Joseon, because the stage 4 relics were the earliest period that had a high level of architectural completion. Furthermore, the relics from stage 3 (latter Joseon) had the same floor size as for stage 4, the only difference being in the size of the stylobate. This further increased the validity of selecting the earlier period of stage 4.

Table 3. Stage 5 excavation site (3x2 bay).

A comparison of excavation material and the planned floorplan is shown in , showing that the floor size was planned to be almost identical to the excavation material.

The floorplan raises some questions. The first question is the official report of excavation published right after restoration plans of Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall on completion of the report of the summary of excavation. So, the restoration plan developed too fast accompanies the doubts on implementing correct restoration. And, the restoration plan lacks the validity of restoration based on an agreement of contemporary people expecting the distribution of official report of excavation.

The second question is the difference in length of each bay between plans of excavation and planned floorplan of restoration. The cause of difference and how they were determined are not recorded despite those are important issues to be recorded in the report of repair and restoration of Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall. The report of repair and restoration of Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall says, “Scale (用尺): 1cheok (尺): 300mm”, however, these comments disagree with planned floorplan. These are not mentioned in “Lim, S.-N. 2012. A study on the restoration process and outcome in ‘Nak-San Temple’ of Kwan-yin (Avalokitesvara) holy place” published thereafter thus there are no ways to identify them. This was just the case of basic materials unable to identify their sources and unable to identify how they were included in the restoration plan.

The above two issues become part of raising questions on the integrity and authenticity of restored architectural heritage. And these also raise an issue that they must be recorded in plans for restoration work. These should be included in the “Report of Repair”, etc.. Besides, while the excavation material for the stylobate was a square-shaped 14x14m, in the planned floorplan the stylobate was 15.39 × 15.39 m and thus 1.39 m bigger than the excavation material. The difference in size of the stylobate relates to the portion of the foundation stone viewed as the end of the stylobate. In the excavation material, the middle portions of the foundation stones were selected as the end, while in the planned floorplan the outsides of the foundation stones were viewed as the end.

Therefore, we can see that while the floorplan was mostly created following the excavation material found in stage 4, this material was not followed exactly and new interpretations were made.

4.2.2. Usage of picture material

Regarding picture material, the period in which the picture was created, judgments on whether it was painted in situ or at another location, and whether the scenery depicted in the artist’s previous works matched reality were considered. These considerations were made in the “Excavation Report of Naksansa” and “A Study of historical material value of travel panoramic sketch of Kwandong Province,”Footnote7 where it was determined that the Naksansado of Hongdo Kim was closest to the actual structures. Therefore, this became the basic form for the placement of structures in the restoration.Footnote8

However, as Hongdo Kim’s picture was from the late Joseon, it is difficult to say that it depicts the exact form of early Joseon, which was the restoration period for the Naksansa Wontongbojeon. However, if one looks only at the Wontongbojeon, most pictures show the same gambrel roof form and central stairs, so that it can be inferred that previous periods probably had a similar form. For this reason, the gambrel roof and central stairway in the stylobate were retained.

4.2.3. Usage of other material

The photograph material of Joseongojeokdobo and the literature material of Geonbongsageup Geonbongsa Malsagi were both created during the Japanese occupation of Korea. There is a large difference between the restoration period, particularly in the late Joseon form, of the structure shown in the Joseongojeokdobo and the early Joseon form. Thus, it was difficult to use these two materials during the restoration process.

4.3. Usage of existing structures – an indirect source material

As mentioned earlier, the range of material related to existing structures that are similar to Wontongbojeon was decided on after the restoration period had been selected and after the characteristics of the restoration period had been analyzed.

When viewing the construction period of existing wooden structures in Korea, the oldest are from the Goryeo period, few structures from the early Joseon remain, and most were constructed in late Joseon. Therefore, as there are no similar structures from the Goryeo period or earlier in Korea, there was no target for comparison. For late Joseon, however, many materials exist so that selecting existing structures is much easier.

However, in rare cases, similar structures exist from the late Goryeo–early Joseon period. In addition, the size, form, function, etc., of these structures vary, and as the number of cases is too small, structures with different forms could not be excluded from use as restoration cases.

Therefore, similar existing structure material had to be included.

In the restoration report, the direction of the restoration was set as an early Joseon multi-layered structure.Footnote9 As examples of existing structures, the forms of the four structures referred to were Simwonsa Bogwangjeon (late Goryeo: 心源寺普光殿), Bongjeongsa Daeungjeon (early Joseon: 鳳停寺 大雄殿), Sungnyemun (early Joseon: 崇禮門), and Gaesimsa Daeungjeon (mid Joseon: 開心寺 大雄殿). While it was similar to the Beopjusa Wontongbojeon (法住寺 圓通寶殿) from a floorplan perspective, this was not reflected as there was a difference in the construction period.Footnote10

Examining these points, we can see that consideration of existing similar structures was limited to structures with a construction period from late Goryeo to early Joseon, and therefore from the same time period as the restoration period. While three of the structures were main Buddhist buildings, the selection of Sungnyemun as a source material shows that they expanded the range of existing structures to include those with a similar function. However, the exclusion of Beopjusa Wontongbojeon as a source material shows that they considered the construction period of existing structures to be the most important factor.

We can infer that there were many opinions regarding how to set the range of source material for existing structures. One cultural assets member recommended that Gaesimsa Daeungjeon, Heungguksa Daeungjeon (興國寺大雄殿), and Hwanseongsa Daeungjeon (環城寺大雄殿) be referred to for the form of the bracket and beam heads.Footnote11

In addition, the fact that for the curlicue ornamentation of the pillar top, a similar form to that in Bongjungsa Daeungjeon was plannedFootnote12 shows that Daeungjeon was used as the source material for the form of the bracket. In Seung-Nam Lim’s (Hyeongo) thesis, the Wontonbojeon that was constructed is closer in the form to the later middle Joseon period than early Joseon, although it generally follows the rules.Footnote13 Therefore, we can see that the form and angles of Bongjeongsa Daeungjeon ()were followed in general.

Ultimately, we can see that, due to the fact that source material on detailed aspects of form, such as the form of the bracket, did not exist, these details could only be recreated by investigating indirect source material in the form of existing structures.

5. The value and usage of source material during the restoration of the naksansa wontongbojeon

5.1. Relationship between restoration period, source material, and usage methodology: securing authenticity

Determination of the restoration period based on the source materials about wooden architectural cultural properties means that the authenticity of the restoration period is secured. In the case of the Naksansa Wontongbojeon (), the excavation material included relics from five layers, from the Goryeo period to modern times. Therefore, relics from stage 4 (early Joseon), i.e. the earliest time period with high architectural completeness, were examined before early Joseon was selected as the restoration period. In addition to the excavation material, the picture material from Hongdo Kim, which matched the excavation material, also played an important role in establishing credibility. Thus, it can be seen that excavation played an important role in the decision on the restoration period.

Once the restoration period had been selected in this way, the material on existing structures was collected and categorized. However, as the number of existing structures from early Joseon was very limited and the function, size, form, etc., of these structures varied, all were originally selected but just four were subsequently used as source material for restoration. Of these, Bongjeongsa Daeungjeon was deemed important, while the picture material from Joseongojeokdobo that showed a much later period of the form (late Joseon) and the material on Wontongbojeon from 1950–2005 were not used for restoration.

Ultimately, as shown in the restoration of Naksansa Wontondbojeon, the selection of the restoration period, the range of source material for use in restoration, and the decision regarding which material to use were all mutually influential.

5.2. The relationship between source materials and usage methodology: securing integrity

As mentioned above, source material can be divided into material for use and material that is ultimately discarded. More specifically, excavation material was a useful source for floorplans, but rather than matching exact numerical sizes, the material was reinterpreted to slightly change the size for restoration. We can also see that the upper roof form of gambrel roof was selected using the picture material of Hongdo Kim’s Naksansado. This can be determined since the selection of the restoration period, the photograph material from Joseongojeokdobo, and material from the immediate pre-fire period were not used.

As such, the range of similarity in the search for similar existing structures was wide, with minor limitations in function and size, from structures from a similar time period. From the similar existing material, the bracket form from Bongjeongsa Daeungjeon was selected, but not an exact copy thereof; instead, its style was expressed in a similar but independent manner.

For Naksansa Wontongbojeon, the contents of source materials was newly interpreted according to the meaning and situation of restoration for integral restoration, rather than used as is. It can be also referred to be comprehensive thought. As the restoration of central hall in Buddhist temple with repeated reconstruction and rebuilding in its history, it is the restoration and continuity of Buddhism and community culture that have been in existence so far. Restoration of Wontongbojeon, the historic temple representative of shrines of Guanyin in Korea and where a number of people visit in the present, reveals the society it belongs to as well as its functional integrity.

6. Conclusion

This study has focused on the collection of source material and the selection of the restoration period during the restoration process of a main Buddhist building in an early Joseon Buddhist temple. It is a necessary part of the early stages of a restoration, and entails making the most important decisions regarding the restoration plan. In the process, there are several different kinds of source material corresponding to each restoration case which are to be restored according to respective restoration processes. However, the comprehensive and distinguishing examination on all processes which are determining the restoration period and source material will secure integrity, authenticity, and continuity of restored architectural heritage.

Source material for restoration can be divided into excavation material, picture material, literature material, material on existing structures from the same period or similar structures, and photograph material. Each type of material has different characteristics, making it meaningful to collect and utilize all types as material for restoration. These source materials are important factors in deciding on the restoration period, the selection of which is interrelated with the selection of source material for use.

In the case of Naksansa Wontongbojeon, excavation material played an important role in determining the restoration period, while existing similar material played an important role in determining the aesthetic aspects of the restoration. In addition, opinion of the Naksansa administrator also played an important role in determining the restoration period. And the issues lacking source material for floorplan and pertinent records of Naksansa Wontongbojeon hall were mentioned in the perspective of securing integrity and authenticity thereby the issue of inclusion of records of basic materials had to be raised.

Restoration of wooden architectural cultural properties found its significance in historic authenticity via analysis of source materials and selection of restoration period and secured integrity from the assessment of various materials as well as function and meaning of current buildings. In this judgment, wooden architectural cultural properties have continuity to include value of time and human life in present in the concept of restoration.

This study scrutinized the process to restore the central hall in Buddhist temple with specific cases. As a result, the role of source materials in restoration and correlation between the source materials and the restoration period determined were understood. Furthermore, this study determined the concept of restoration that should consider continuity of human life, by securing authenticity and integrity while tracing the process of restoration.

Acknowledgments

The early draft of this paper presented at the “International Conference on East Asian Architectural Culture 2017”.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jae-Young Lee

Jae-Young Lee studied architecture and city planning at the University of Yonsei (BA, MA) in Korea, at the School of Architecture in Versailles (MA) and at the School of Architecture of Marne-là-vallée (PostMaster). He was awarded his PhD in Urban studies at the EHESS (The School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences) in 2014 in France, and works as visiting researcher at the Institute of Engineering Research of Yonsei University. His research focuses on history and theory of architecture, especially on the relations between architecture and nature.

Dai Whan An

Dai Whan An earned his Ph.D. in history of Korean architecture from the Yonsei University, Korea, 2011. He had worked for preservation design and surveying work of Korean architectural heritage in Architect’s office from 1997 until 2013. He works in department of history and cultural contents, Sunmun University from 2013 until 2015. Nowadays, he studies on the relationship with 3D scan data and survey report of buildings, and the restoration of buildings in the excavation site.

Notes

1 Priest Hyeongo participated directly as the chief manager of the restoration of Naksansa. In addition, Priest Mumun, as a priest of Naksansa at the time, played a certain role in the restoration and later acted as the chief priest of Naksansa. Ultimately, as the authors participated or directly experienced the restoration of Naksansa, their material on its restoration should be considered accurate.

2 Naksansa Wonjang (洛山寺垣墻) is a kind of wall around the Wontongbojeon. It was said to have first been built when Sejo of Joseon repaired Naksansa, and mostly remained as ruins until it was recently connected and repaired. Therefore, the range of excavation and restoration of the Wontongbojeon may be limited due to the wall..

3 Ultimately, in the restoration of Naksansa, the Wontongbojeon was restored in the form of early Joseon, while the other buildings were restored as late Joseon.

4 Although the “Yangyang County?National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Excavation Report of Naksansa, 2008” was not published until 2008, it was used in the restoration planning before publication.

5 Cityhall of YangYang County (Citation2007).

6 National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (Citation2008).

7 Sang-Kyun Lee (Citation2009). At pages 99–120, they each identified the authenticity of each Naksansado and identified that the Naksansado by Hongdo Kim had the most realistic value.

8 On the other hand, in Seung-Nam Lim (Citation2012), it was discussed that the placement of structures in the Naksansado by Hongdo Kim may not be accurate.

9 In Cityhall of YangYang County (Citation2007, 87), they recorded the building commemoration verse and made it official. “Appointed the structure restoration advisory committee to gather and verify historical material to restore as a multi-layered early Joseon building.” On p. 64, it also states: “3-1 Restoration direction A. Plan: Planned as a multi-layered early Joseon building {Scale (用尺): 1cheok (尺): 300mm.” This shows that the direction for the restoration was for an early Joseon building.

10 Cityhall of YangYang County (Citation2007, 64): “B. Aim: While the construction dates of the 4 structures – Simwonsa Bogwangjeon (late Goryeo), Bongjeongsa Daeungjeon (early Joseon), Sungnyemun (early Joseon), Gaesimsa Daeungjeon (mid Joseon) – are different, their structural interrelationship made them a reference for the form that appears in early Joseon structures. Naksansa Wontongbojeon has a similar floorplan to Beopjusa Wontongbojeon. However, one recorded difference is that Naksansa Wontongbojeon is forward facing and, due not only to the difference in a time period but also structural weaknesses, this was not reflected.”

11 Cityhall of YangYang County (Citation2007, 94): In the consultation by the Restoration Advisory Committee, the opinion is recorded that “The form of the brackets and beamheads at Gaesimsa Daeungjeon, Heungguksa Daeungjeon, Hwanseongsa Daeungjeon should be referred to for the construction on site.”

12 Cityhall of YangYang County (Citation2007, 105): It is recorded that “the curlicue ornamentation of the pillar top is similar in form to that in Bongjeongsa Daeungjeon in the form when the ornamental cow’s tongue spread down in a simple and powerful form,” with a plan of the ornamental cow’s tongue of Bongjeongsa Daeungjeon. In addition, in the thesis by Seung-Nam Lim above, it states that the bracket form from Bongjeongsa Daeungjeon was followed (p. 73).

13 Seung-Nam Lim (Citation2012, 73) stated that, compared to the bracket of Bongjeongsa Geungnakjeon, that of Wontongbojeon is closer to the form of early mid Joseon but it generally follows the rules.

References

- An, D.-H. 2016. “Characteristics and Utility of 3D Scandata for the Development of Survey Drawings in Wooden Architectural Heritage: A Comparison of the Raw Survey Data Used in Survey Drawings.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 15 (2): 161–167. doi:10.3130/jaabe.15.161.

- Bae, J.-H. 2016. “The Study of the Restoration Project of Naksansa Temple: Focusing on the restoration Work from 2005 to 2013.” Thesis. DongKuk University.

- Cityhall of YangYang County. 2007. “Report of Repair and Restoration of Naksansa Wontongbojeon.”.

- Han, Y. U. 1928. "Geonbongsageup Geonbongsa Malsa Sajeok, Gosunggun".

- Jukka, J. 2006. “Considerations on Authenticity and Integrity in World Heritage Context, City&time, V2N1.”

- Kim, H.-C., and D.-W. An. 2016. “An Study on the Construction of Basic Data System for Restoration of 3 × 3 Kan Central Hall Remains of Buddhist Temple in Joseon Dynasty.” Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 7 (9): 163–177.

- Lee, S.-K. 2009. “A Study of the Historical Material Value of A Travel Panoramic Sketch of Kwandong Province (關東地域 紀行寫景圖).” Journal of Cultural History on Kangwon Province 14: 99–120.

- Lim, S.-N. 2012. “A Study on the Restoration Process and Outcome in “Nak-san Temple” of Kwan-yin (Avalokitesvara) Holy Place.” Journal of Pure Land Buddhism, the Korean Society of Pure land Buddhism 17: 65–114.

- National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. 2008. “Excavation report of Naksansa.”

- Principles for the Preservation of Historic Timber Structures. October, 1999. Adopted by ICOMOS at the 12th General Assembly in Mexico. Mexico: ICOMOS.

- Riegl, A. 1903. Moderne Denkmalkultus: Sein Wesen Und Seine Entstehung. Edited by W. Braumüller. Charleston, SC, USA: BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781359865304.

- Si, A. 2004. “Repair Report of Bongjungsa Daewongjeon.” 鳳停寺 大雄殿.

- The Venice Charter. “International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites.” Adopted by ICOMOS in 1965.