ABSTRACT

Socio-cultural factors are amongst the most prominent forces that reshape the development of housing in Qatar when considering its vernacular architectural history. The research study uses space syntax analysis supported by other simulation and visualization techniques to examine the extent to which socio-cultural patterns influence the spatial form of traditional Qatari houses. The findings reveal that, despite changes in time and across eras, socio-cultural patterns, namely, (i) privacy, (ii) gender segregation, and (iii) hospitality, determine the spatial form of Qatari vernacular houses. Knowledge obtained from this research study contributes to the construction of architectural identity, auspicated to be referred to along the planned strategy for the urban regeneration of the built environment in Qatar (as envisioned through the goals of Qatar National Vision 2030).

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

In the context of the Middle East, North Africa region (MENA) and the Arabian Gulf region, the typical vernacular house is characterized by design parameters shaped by the socio-cultural structure (AL-Rostomani Citation1997; Lewcok and Freeth Citation1978; Majida, Shuichib, and Takagi Citation2012). Traditional houses are primarily organized on the basis of culture and belief. Social networks, based on Islamic principles, are used to govern most of the societies in the region, including the Qatari society, promoting the socio-cultural and behavioral patterns of (i) privacy, (ii) gender segregation, and (iii) hospitality as major determinants of the human-environment interaction (Campo Citation1991; Fathy Citation1986; Remali et al. Citation2016; Salama Citation2013; Sobh and Belk Citation2011).

Among the most common sustainable housing typologies or archetypes, the courtyard house, is known to be a responsive typology to “low rise high-density urban housing” and “is an appropriate form of housing within contemporary mixed use sustainable urban developments” (Edwards et al. Citation2006, xvii). The common formative scheme of the courtyard house includes a one-storey angle-shaped built block with a central open space contained within boundary walls or adjoining buildings ().

Figure 1. Traditional vs. Western sense of place in houses. Source (Pahl-Weber et al. Citation2013, 67).

The courtyard house is a wide spread domestic typology across different climates and cultures in the world from China to Morocco. Its form supports family and community life and proves its usefulness and popularity as a socially sustainable facet of architecture in traditional and historical settlements, namely in the Mediterranean and the Middle East regions (Petruccioli Citation2008; Ragette Citation2006; Salama Citation2006, Citation2003; Zhang Citation2016). On that account, “the courtyard house requires attention because it is the residential type which responds simultaneously to cosmic, cultural and climatic forces. As such, it is the main residential type in the Arab region, although it enjoyed a form of parallel evolution beyond the Middle East” (Petruccioli Citation2008, 874).

The traditional Qatari house represents a unit of analysis to investigate residential architecture within a transformative social framework. The analysis supports social sustainability in housing interpreted in terms of the social constraints limiting development, the social preconditions necessary to support environmental sustainability and the maintenance of the wellbeing of current and future people generations (Ahmed Citation2017; Chiu Citation2004). The social sustainability of architecture is presumably linked to socio-cultural nature of housing, which in turn references theories of urban design and regeneration. The aim of relinking social sustainability to housing and its architecture is to maintain a distinctive Qatari and Middle Eastern urban identity capable of providing future generations with sustainable dwelling options.

In domestic architecture, privacy is one of the most predominant factors in determining the internal configuration of houses. In fact, the development of the house is based on the idea of separating the public and private domains where privacy of the family or household is preserved by architectural interventions such as gates, walls, doors and windows.

Within the household, spaces are distributed based on functionality, hierarchy of activity, accessibility, level of privacy and, in some cases, the gender of occupants. Thus, the issue of gendered spaces in housing presents an interesting human behavior phenomenon considering the influence of socio-cultural factors in the built environment. This discussion leads to contemplation on the roles of males and females in domestic spaces, which is subject to the societal limits of relationships and segregation.

Within the private domain of the house, specific socio-cultural attributes are directed toward fulfilling the needs of the society as a unifying system. The rise of hospitality as a determinant pattern of the socio-cultural development of housing in Qatar and the entire MENA region signifies the important relationship between the individual and the community-the private and the public.

In addition to religious and socio-cultural norms, the region’s climate historically influenced the way rural communities used to interact with the built environment, leading to the creation of historical built solutions to foster the human-environment interaction (Fathy Citation1986; Weber and Yannas Citation2014). In theory, traditional houses reproduced exclusive architectural and design parameters following the requirements of the era.

The research is directed toward answering the following question that primarily targets socio-cultural factors reshaping residential architecture in Qatar: To which extent does the predefined socio-cultural factors, specifically privacy, gender segregation and hospitality, influenced the spatial form of the traditional Qatari house? In addition, how can the influence of socio-cultural factors, local spatial practices and values in reshaping the spatial configuration of houses, be tested and validated, utilizing the theoretical tool of space syntax?

Through analytical contemplation and graphical simulation of selected cases of traditional houses, the methodology of space syntax is utilized because of its ability to investigate the relationship between socio-cultural phenomena and the spatial layout of houses. Further analysis of socio-cultural patterns is supported by other analytical and visualization techniques.

2. Literature review

2.1. Socio-cultural patterns in the spatial form of the house

The review of the literature reveals a rarity of references that comparatively reconnect the spatial form of houses to specific socio-cultural patterns, namely, in the context of the State of Qatar. However, few studies have established a fair interdisciplinary approach considering the analysis of the built form and spatial organization of houses in other Islamic countries. Among them is a recent journal article entitled “Privacy, Modesty, Hospitality, and the Design of Muslim Homes: A Literature Review”, which is based on the theory of home environments. According to the authors, “the design of traditional Muslim homes is subject to guidelines from principles outlined in Islamic Sharia Law, which are derived from the Quran as well as hadiths and sunnahs” (Othman, Aird, and Buys Citation2015, 13). The authors outline three basic principles as criteria for evaluating the spatial design of Muslim homes: privacy, modesty, and hospitality.

Another study elaborates on the principle of privacy through the analysis of behavioral patterns in the spatial configuration of housing in the regional context (Alitajer and Nojoumi Citation2016; Aycam and Varshabi Citation2016). The study applies the methodology of comparative analysis between traditional and modern dwellings in the city of Hamedan in Iran through computer simulation, with the aim of investigating the effect of privacy over the course of time. The study concludes that the difference between traditional and modern houses revolves around the integration and equivalence of all spaces in a house, or the hierarchy of access to spaces.

Within the same regional context, a study titled ‘Process of Housing Transformation in Iran’ (Mirmoghtadaee Citation2009) provides a theoretical analysis of the transformation of housing form and lifestyles in developing countries. The study argues that Iranian houses have changed dramatically in recent decades due to social, economic and technological transformation. A very similar trend in the process of housing transformation can be seen in Qatar’s recent past. The economical and industrial evolution of the country in the 1950s is the source of the physical and morphological changes in housing. The demographic features, physical and functional characteristics of the house, and change in social setting and lifestyles demonstrate the parameters for analyzing the process of housing transformation in developing countries.

With reference to applying participatory design, such as the theories of Alexander (Alexander et al. Citation1987) and Gehl (Gehl Citation2011), a study of social participation in the design of residential architecture established the comparative base for analyzing socio-cultural patterns of residential units. In the local context of Poland, a researcher illustrated the direct positive effect of mutual social interactions in the process of housing participatory design. According to the study, “social participation in the design of residential architecture has a positive impact both on the architecture and on the relations between people who are involved in the creation of such architecture” (Kosk Citation2016, 1469).

The study refers to nine characteristics of space as evaluation criteria extracted from the literature review of participatory design theories; it then applies the criteria to the selection of three case studies. The selected case studies are examples of residential architectural projects created as a result of participatory design. This methodology is highly effective, considering the social sustainability of residential architecture.

In this research study, there are three definite patterns embedded within the socio-cultural profile of Qatari society that highly govern the spatial form of houses. These include (i) privacy that is investigated through space syntax methodology, (ii) gender segregation as an intermediate pattern of analysis between the public and the private, and (iii) hospitality as a social pattern that deals with the public realm.

Privacy is the main socio-cultural parameter that affects the spatial form of Qatari houses. In the literature, the notion of privacy has been widely discussed by Western scholars within specific socio-political contexts; meanwhile, the focused scope of analysis is placed on Qatar as a Muslim and Arab country in the MENA region (Hanson Citation2008; Margulis Citation1977; Michelle Citation1986; Newell Citation1994; Westin Citation1970). Thus, the concept of privacy is considered in its Islamic approach and defined as “the inviolable and scared character that Arab-Muslims attribute to their homes and precludes violation of this scared space as haram, or sinful” (Sobh and Belk Citation2011, 322). There is a proportional relationship between home and privacy, where the latter gives the unit of the house its sense of peaceful sanctuary beyond the physical form. Most of the houses in the MENA region and the GCC make a sharp distinction between the public and private spheres, where privacy covers various requirements including functional privacy, visual privacy, acoustical privacy, and olfactory privacy (Al-Thahab, Mushatat, and Abdelmonem Citation2014; El-Shorbagy Citation2010; Mortada Citation2003). Privacy is layered hierarchically from privacy from the neighbors’ dwellings to privacy between family members within the household (Othman, Aird, and Buys Citation2015). As a matter of fact, Islam appreciates the individual’s right to have a privatized space and supports the maintenance of personal privacy at home ().

Figure 2. Layers of privacy in traditional Muslim homes. Source (Bahammam Citation1987) cited by (Othman, Aird, and Buys Citation2015).

One outcome of privacy is gender segregation, which in itself is a highly influential pattern in the spatial form of Muslim houses (Farah and Klarqvist Citation2001). The level of gender segregation tends to vary between Muslim cities in the MENA region as it has been subject to different interpretation of religious norms, economic conditions, specific socio-cultural circumstances and identity guidelines. Such differences enriched the urban history of Muslim cities as seen through the variety of house models and design forms of domestic spaces, subjecting architecture to local imperatives (Campo Citation1991; Cooper Citation1995; Nageeb Citation2004; Spain Citation1992). In this respect, Qatar is a traditional Muslim country and is a gender-divided society. According to a study on the cultural life script of Qatar, Denmark-based authors note that the clear segregation of men and women in Qatar presents “an ideal opportunity for exploring gender differences and the effects of religion” (Ottsen and Berntsen Citation2013, 393). This could include an analysis of the spatial form of residential units, as this form is highly interrelated to the pattern of gender segregation.

Hospitality is another noticeably effective socio-cultural pattern that influences the spatial form of houses in Qatar, considering the social distinctions of family lineages and their deeply rooted lifestyle in the pure Arab culture. Hospitality is integral in pre-Islamic Arab culture, and its value has been approved by Islamic divine sources as it supports the creation of a tied, faithful community. Throughout urban history, “a place for the gathering of men and for reception of guests existed in most courtyard houses within Arab Muslim cities” (Almahmoud Citation2015, 44), which in turn was subject to regional differences in terms of naming the designated space, its internal arrangement, building methods and other architectural aspects. Meanwhile, such spaces are created based on similar needs and a clear function, specifically fulfilling the socio-cultural pattern of hospitality. In Qatar, the rise of Majlis spaces within pre-oil tent settlements, traditional courtyard houses and contemporary houses is a by-product of embraced cultural norms. In the contemporary context, however, “nobility, hospitality and generosity – for example, are seen as essential traits somehow ‘bred’ into the Bedouin that are weakening with miscegenation and materialism” (Nagy Citation2006, 131). This argument initiates the basis for the comparative analysis between vernacular and modern dwellings, with reference to transformation of socio-cultural patterns in Qatar.

2.2. What is traditional architecture?

Leon Krier’s book ‘The Architecture of Community’ provides a thorough explanation of his conceptual ideas on creating sustainable and liveable urban settlements and cities (Krier Citation2009). He presents the enduring debate on traditional and modern architecture, representing the former as a process that tends to produce objects of long-term use and the latter as a process that creates objects for short-term consumption. Although much of Krier’s contribution focuses on the Western context and the transformation from vernacular, traditional and classical architecture to modern architecture due to geo-political and economic realities, his analytical explanation of urban concepts creates a general framework that aligns with various global contexts.

When questioning the nature of architectural objects in region and style, Krier argues that “the idea of replacing the world’s rich panoply of traditional architectures by a single international style is dangerously insane” (Citation2009, 53). He further supports his argument by rethinking the reconstructive progress of traditional architecture, which ensures its sustainability as a cultural choice of a determining influence ().

Figure 3. The universal principles of traditional architecture. Source (Krier Citation2009).

2.3. Built forms in the state of Qatar

2.3.1. Characteristics of Qatari architecture and urban design

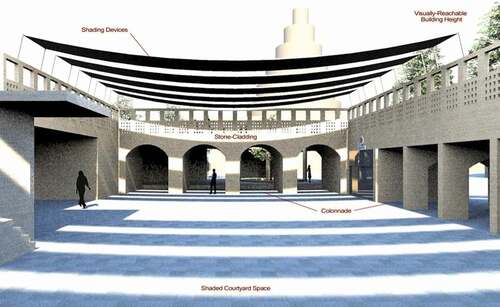

Qatar’s vernacular architecture is a manifestation of harmony between the needs of its inhabitants, the physical environment and the availability of building techniques and materials. The characteristics of a typical Qatari house in the past were limited to certain architectural elements that reflected this strong interaction. The traditional characteristics of Qatari urban design and architecture, illustrated in , could be defined by three conceptual themes: simplicity, solidity and passive low energy design (Beattie Citation2014). With the introduction of 21st-century technology, it is possible to achieve a timeless architecture that has direct relevance to Qatar’s past and sustains its characteristics into the future.

Figure 4. Traditional characteristics of Qatari architecture. Source (Beattie Citation2014).

Overall, the conceptual representation of the contemporary urban design language of Qatar is inspired by the past, which is highly relatable to the patterns of the Qatari society and people’s traditional means of life. Culture is an integral part of the concept that defines sustainability both as a spatial and social experience (Douglas Citation1971). Accordingly, the hope of contemporary urban design is to create a portion of the city with shaded, pedestrian-friendly spaces. Another important goal is to bring Qatari families back to use the city in an effective way, limiting sprawl and enhancing the compact-city growth model.

Through urban design elements like courtyards, communal gardens, secure private spaces, shaded rooftops, patterns of shade and shadow, choice of color or patina, shaded open spaces and walkability strategies, the outcome is a form associated with the urban identity of Qatar ( and ). Such influences on Qatari architecture and urban design are drawn from studying architectural heritage, craft traditions, archaeology, the natural environment and the local landscape, rather than simply transcribing from the past (Bullivant Citation2012; Excell and Rico Citation2013; Law and Underwood Citation2012; Makower Citation2014).

2.3.2. Housing in the state of Qatar: now and then

According to a study carried out in the late 1990s, “vernacular buildings in Qatar have employed some ingenious passive techniques in order to restore thermal comfort within the building, particularly during the hottest hour of the day” (Sayigh and Marafia Citation1998, 26). Such techniques relate to spatial form as well as physical layout.

In the past, houses within compact neighborhoods shared thick mud walls resulting in mutual shade and improved thermal comfort within the interior space (). The interior space, however, surrounds an open-air courtyard that resembles the core of the housing unit, physically and socially (Al-Kolaifi Citation2006; Alraouf Citation2014; Gharib Citation2014; Soflaei, Shokouhian, and Zhu Citation2017).

Figure 7. A typical vernacular Qatari neighborhood in the past. Source (QNDF Citation2014).

The courtyard house typology dates back to the Graeco-Roman period and was later developed by Arab nomads who were familiar with locating their tents around “an open central space to provide shelter and security” for their settlements (Almahmoud Citation2015, 44). Thus, the open space in the courtyard house was the result of a series of historical urban transformations responding to a set of common socio-cultural and environmental necessities (Dunham Citation1961; Edwards et al. Citation2006; Khalili Citation2012).

The contrast of solid and void between the thick exteriors and the open interiors responds to the socio-cultural parameters of vernacular Islamic architecture, as an introverted typology of a veiled nature. Therefore, “in Islam, attention is given to the external appearance of the house where homogeneity is the main aspect. However, the symbols of status and identity are expressed throughout the interior of the house” (Alkhalidi Citation2013, 291).

In The History of Qatari Architecture, the traditional Qatari house form is defined by four basic elements: the courtyard, the various spaces lining the courtyard, the ground floor rooms and the first floor rooms (Jaidah and Bourennane Citation2009). Most domestic activities take place within the protected core of the courtyard, and the rooms are reserved for private family use. In this respect, “courtyard houses, which are common in regions with hot and dry climates, demonstrate strict territoriality and attempts to create private space for introversion” (Bekleyen and Dalkil Citation2011, 908).

The transformation of housing in the modern era is traced through an evolving process starting in the early 1950s with the discovery of oil and the wealth generated by its production and infrastructural development (Abdulla Citation2010; Adham Citation2008). Hence, “the most important development during this period was the establishment of modern housing connected to modern infrastructure” (Remali et al. Citation2016, 6).

Factors that account for the transformation of spatial form of Qatari houses from traditional to modern models include the administrative development of the state, foreign investment, Western construction methods and standards, social welfare mechanisms and other transformative socio-economic factors (). The transformation of the traditional courtyard house into a multi-storey villa is the major shift in the spatial form of housing in Qatar, marking a break in the evolution of house form (Remali et al. Citation2016; Sayigh and Marafia Citation1998; Talib Citation1984).

Figure 8. Recent situation of an old courtyard house in Doha. Source (PEO Citation2015).

The contemporary villa is designed and built without regard to local contexts, providing a housing typology that is extroverted and box-like in structure and defined by an enclosed wall (). According to a typological study of housing in the Gulf cities including Doha:

In contrast to the traditional typology of courtyard houses, the internal spaces of a modern villa are oriented outward toward the surrounding yards or outdoor spaces (Remali et al. Citation2016, 10).

Figure 9. A typical alignment of modern neighborhoods in Doha, Bani Hajer District. Source (Elblaus Citation2017).

The socio-cultural pattern of privacy, however, is preserved spatially by local families, resulting in a certain spatial configuration of the interior spaces of the modern house. For example, the courtyard is replaced by a salon or a living room that “acts as a circulation space on the ground floor to which all other rooms have access” (Talib Citation1984, 127). Another example is the appearance of guest rooms or the Arabic Majlis as spaces for hospitality, secured and isolated from other functional spaces within the household and located next to entrance spaces to enable separation between the family and visitors – the private versus the public. Such patterns are contemplated within the limited choices of the market and other international design imperatives.

3. The research design

3.1. Space syntax

The built environment is both a product of society and an influence on society. Space syntax aims to investigate and understand this relationship. It has developed a set of techniques for the simple representation of architectural and urban space (Major Citation2017).

Space syntax is a research framework capable of generating a descriptive and qualitative analysis of the spatial formations and urban systems, ranging from the interior of a room to the city and its wider landscapes (Dursun Citation2007; Nourian, Rezvani, and Sariyildiz Citation2013). It is both a concept and a methodology used in urban morphology and architectural research to analyze spatial configuration within the active social system in addition to other economic and environmental phenomena. The literature review indicates a high application of space syntax methodology in recent publications and studies concerned with residential spaces and housing transformation (Jiang and Claramunt Citation2002; Ratti Citation2004; Xia Citation2013).

The theory of space syntax was originally developed by researchers at the University College London in the mid-1970s, and “has been employed by architects to examine the influence of the spatial layout of buildings and cities upon the economic, social, and environmental outcomes of human movement and social interaction” (Dawson Citation2002, 465). Its purpose is “understanding the influence of architectural design on the existing social problems in many housing estates that were being built in the United Kingdom” (Oliveira Citation2016, 101). Accordingly, publications that are focused on examining the transformation of domestic space in relation to family structure are dominant in the field of space syntax research, with an emphasis on space as a primary arena of sociocultural events.

3.1.1. Space syntax case studies

Space syntax provides effective approaches to understanding housing transformation in local contexts. In the article titled Uncomfortable Prototypes: Rethinking Socio-Cultural Factors for the Design of Public Housing in Billiri, North East Nigeria (Maina Citation2013), space syntax is used to analyze space use patterns in 45 randomly selected public compounds (). The compounds are government-funded and occupied by a local community, which has its own socio-cultural lifestyle. The study examines the transformation of the prototyped housing units by local communities to suit their changing needs, resulting in dysfunction and dissatisfaction with the units. Space syntax provides insights on the space use patterns and relates to the issues of kinship and security considerations of local communities. The study supports the creation of public housing schemes that respond to socio-cultural patterns of native communities.

Figure 10. Spatial analysis of government-provided prototype II in Billiri. Source (Maina Citation2013).

3.1.2. Connectivity in space syntax

Space syntax is used to analyze the two-dimensional spatial properties of architectural plans at different scales, from a single house to the analysis of the entire city (Hillier and Hanson Citation1984; UCL Citation2018). The relationship between spaces and their social properties is shown graphically in convex maps. In theory, convex maps are concerned with enclosure spaces with limited movement and perception, and their connectivity is represented as nodes and edges (Lee, Ostwald, and Lee Citation2017).

Quantitative arithmetical descriptions are developed based on the generated convex maps, including the index of connectivity, defined as the number of direct connections to other spaces or movement paths capable of describing mutual relationship between spaces. Connectivity is a syntactic measure and a local property; it represents the number of convex spaces that are directly connected with one certain element (Bus and Pedraza Citation2016; Hillier and Hanson Citation1984).

The index of connectivity provides basic information that relates to the user’s understanding of the entire building configuration. Appropriately, “the most significant aspect of the connectivity concept is the reflection of the form of the space based on the visual perception it has created in the mind of the person using the space” (Arslan and Köken Citation2016, 90).

3.2. Adopted method of analysis

Since the analysis concentrated on socio-cultural patterns in the spatial form of traditional Qatari houses, the interior spaces were the focus of the research. Accordingly, space syntax, which is defined as the representative technique to quantify spatial patterns in buildings, was used to analyze spatial configuration of spaces with socio-cultural significance in contemporary and historical contexts (Bellal Citation2004). It was translated into a series of computer-aided programs and applications to ease the process of analysis.

The computer program Depthmapx-0.5 assists with simulation and modeling techniques, and it can produce visibility analysis in terms of space connectivity, integration and depth under the theory and method of space syntax. Generally, Depthmap is a user-friendly platform that allows for importing two-dimensional (2D) layouts, then creating visibility graphs according to the user’s set of requirements (Knowles and Sweetman Citation2004; Smith and Bugni Citation2002; Turner, Citation2011; Yin Citation2003).

The focus of analysis in this research study was limited to the index of connectivity, defined as “the number of points at which a space is directly connected to other spaces” (Alitajer and Nojoumi Citation2016, 344). A graph of connectivity is two-dimensional and capable of representing “the relationships of accessibility between all axial spaces of a layout model” (Dettlaff Citation2014, 286). A color code system visualizes connectivity, ranging from warm red for high connectivity in a space to orange, yellow, green and finally dark blue for the least connective spaces.

3.2.1. Primary and secondary sources

Based on the objective of analyzing socio-cultural patterns in the spatial form of traditional and modern houses in Qatar, a literature review of traditional houses archived in books and references was used in this study to cover the historical analysis (Creswell Citation2003; Newman Citation2007; Zeisel Citation1975). It is important to note that the collection of old housing plans and detailed architectural drawings were provided by governmental authorities working in the conservation sector, such as Qatar Museums Authority (qm.org.qa Citation2016) and the Ministry of Culture and Sports (mcs.gov.qa Citation2016). More traditional housing plans are cited in The History of Qatari Architecture 1800–1950 (Jaidah and Bourennane Citation2009), which is one of the few references that archives the vernacular architecture of Qatar. In the book, a wide collection of domestic buildings is presented; however, this study limits the selection to four cases.

The analysis of the traditional houses covered the following areas: entrances; courtyard style and ratio, spatial forms and configuration of the interior spaces, room typologies and other aspects (Remali et al. Citation2016; Sayigh and Marafia Citation1998; Talib Citation1984). The exploration of the selected houses was cumulatively approached, where knowledge of traditional architecture in Qatar alongside the Gulf region was used to understand the spatial configuration of old houses and the effect of socio-cultural aspects on the process of transformation.

Records of the general historical knowledge included oral as well as visual references. Oral data were gathered by attending seminars and architectural talks on traditional architecture in Qatar, such as the seminars delivered by Eng. Ibrahim Mohammed Jaidah (CIRS Citation2016), the author of The History of Qatari Architecture 1800–1950, and Eng. Mohammed Ali Abdulla, the designer of Souq Waqif regeneration project – Private Engineering Office of the Emiri Diwan (). Other seminars included the 2010 Aga Khan Awards for Architecture in Doha. Such seminars and talks provided a first-hand approach to detailed information on the aspirations and challenges of the historical urban development of the city of Doha and glimpses of urbanism before the discovery of oil in 1950s. The Department of Architecture and Urban Planning in Qatar University organized most of these lectures, seminars and talks via a collaborative academic seminar series.

3.3. Description of the cases

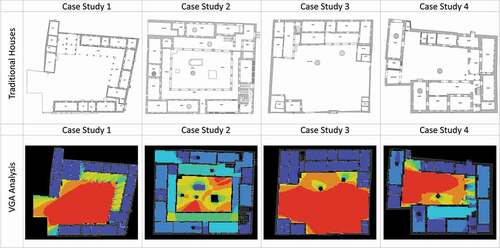

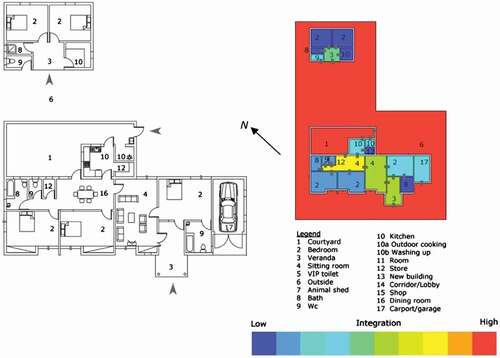

To test and validate the influence of socio-cultural factors, a sample of traditional houses in Qatar was examined in terms of spatial form and graphically analyzed in terms of connectivity using space syntax as simulative software. The methodology of space syntax was applied to a case study sample that was limited to four traditional housing units as shown in . The selection was based on several criteria including the availability of floor plans and architectural references, time of construction, location of the housing unit and other functional and dimensional criteria.

Most of the traditional houses were built during the 1930s and 1940s. The analysis was carried out on the architectural line drawings of the ground floor level. The following pages present the selected case studies of traditional houses with a brief discussion of the spatial form and interior configuration of the units along with architectural layout plans signifying important spaces of each house. Architectural drawings presented are not to scale.

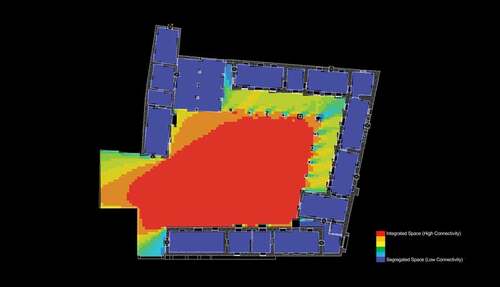

: Traditional House-Case Study 1

Noura Bint Saif House | Al Asmakh, Doha | Built 1930

The Noura Bint Saif House is a single-storey house with one of the largest courtyards in the remaining old houses in the city of Doha. It consists of two main blocks including the guest section, the western corner, and the main household section with seven rooms, reflecting the typical arrangement of courtyard traditional houses in Qatar. The owner of the house is a middle-income family; although currently, it is accommodated by Asian migrant laborers. Originally, the house was named for its female owner. The house is accessible from two entries: the main north gate and the northwest gate. The main gate centralizes the house and is located between the family section and the guest section where the Majlis is situated. It therefore maintains the family’s privacy whenever guests use the Majlis space.

The house has an L-shaped plan with the rooms surrounded by a three-meter-wide porch, arcaded and decorated in simple geometric Islamic patterns. The porch has a social and climatic function, creating a gathering space within the household while providing a shaded canopy from excessive sun, especially around the most utilized rooms. Blocks on the southeast corner were built in a later stage, since one of the spaces is dedicated for a car garage as a modern addition to the traditional house. The four linear rooms in the southwest were also built in the current era.

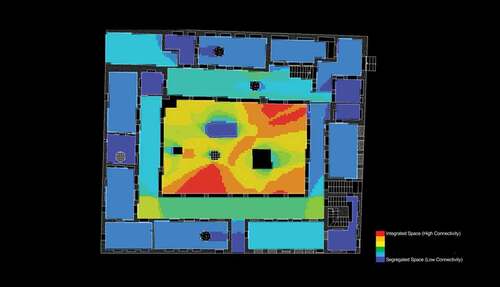

: Traditional House-Case Study 2

Faraj Al Ansari House | Msheireb, Doha | Built 1935

This two-storey house has four entrances to the lower courtyard, which is surrounded by a porch. The ground floor consists of 19 rooms. The space syntax analysis is limited to the ground floor only. The house belongs to members of the Al-Ansari family, who are known as merchants in Qatari society and were previously involved in trading and business activities. The house is located in close proximity to Souq Waqif, the central market of Doha.

The two levels were built at different times as indicated by their different architectural styles. The house is accessible from four entries: three from the east and one from the south. The main entrance is the largest eastern entrance, while the other two entrances from the south lead to staircases. A large courtyard centralizes the house, around which the 19 rooms are gathered and the courtyard itself is surrounded by a concrete porch. The architectural features of the house’s façade include the typical assortment of small windows and few air-catching rectangular openings known as badgiers, while the roof of the interior rooms is made of traditional beams known as danchal (Peo Citation2015).

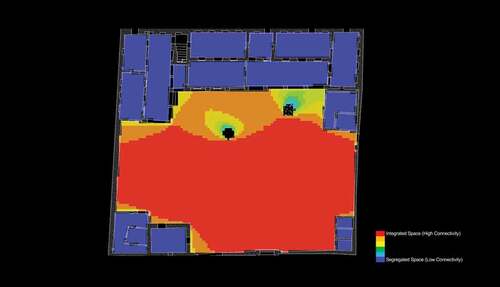

: Traditional House-Case Study 3

Al Jaber House | Al Asmakh, Doha | Built 1935

The house is located in one of the most valuable residential districts in old Doha, namely the Al Asmakh neighborhood. The significance of the area lies in its proximity to Doha’s old port and the active commercial centers so that access to the market and other public spaces was historically assured. The house has a typical architectural configuration with its walled courtyard and L-shaped room arrangement.

The house consists of eight rooms with a simple architectural style. It has two wells of salt water and an imposing entrance. The rooms open onto a raised porch. A high-fenced wall surrounds the house with its main door facing the street. The main entrance has a special door design, with a small door embedded into a larger door; this is called khokha, and it is a familiar door style in Islamic architecture. The khokha door is designed in a flexible way that regulates access to the household; family members and guests use the small door individually as it requires pending, while the large door is used for services, piles and other larger packs.

All rooms are located on the northern side of the house. The courtyard has a large seating area shaded by a big tree beside an old well. Another well is found in the southern corner, which was transformed into a toilet after it was initially built.

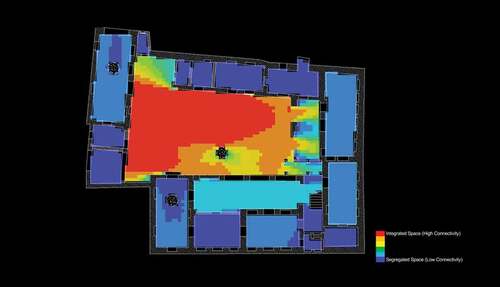

: Traditional House-Case Study 4

Ismail Mandani House | Al Asmakh, Doha | Built 1940

This two-storey house has an entrance gate at the south-western corner. The courtyard is a trapezoid measuring 16 by 7.5 m. Fifteen rooms occupy the ground floor, while only four rooms occupy the first floor. As a socio-economic trend, wealthy families in Qatari society usually construct their houses in two levels due to financial means to obtain more building material and technical construction skills. The main access to the house is through its south-western entrance. The house plot is divided into a family section occupying the northern, eastern and southern walls, while the Majlis block is on the western side.

The courtyard has two iwans, which are vaulted rectangular spaces walled on three sides and open on one side. The first iwan faces the main entry gate while the second is located in the southern block of the house. The first floor is accessible through a concrete staircase leading to four rooms. An arcaded porch surrounds some of the upper floor rooms. Roofs are part of the social life of the old Qatari family; they are mostly used as recreational spaces during the summertime since the night breeze is cooler in the elevated levels.

4. Findings

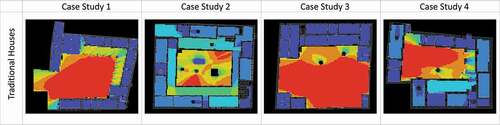

Through the space syntax simulation software Depthmap0.5x, the index of connectivity is presented in color-coded plans based on the number of points at which a space is directly connected to other spaces within the building envelope. Red corresponds to connected space, while blue indicates low connectivity. presents a collective summary of the analyzed houses in color-coded visualization (). Referring to the socio-cultural pattern of privacy, low connectivity can represent a private space, such as a bedroom or a separated room. On the other hand, high connectivity assumes a public space or a space where interaction is supported by built form. The space’s ratio, dimensions, location and entry points determine its connective performance. An analysis of the connectivity of the case studies is presented in the following pages.

: Analysis of Traditional House-Case Study 1

Noura Bint Saif House | Al Asmakh, Doha | Built 1930

High connectivity is observed in the spacious central courtyard. The pattern gradually reduces around the arcades and the porch area, with medium connectivity observed in the color-coded scheme. The main gate on the north wall exhibits a slightly higher connectivity than the rest of the household rooms, signifying its functionality as an access point. The linear passageway connecting the gate to the courtyard presents a gradual connectivity pattern, where connectivity is lower by the door and increases with the approach toward the courtyard. All the rooms within the L-shaped arrangement illustrate low connectivity, as each room is only connected to the central space of the courtyard. A related pattern to consider is the gradual yellow-green shades behind the columns of the porch, which indicate that behind the column, connectivity is reduced due to visual privacy.

: Analysis of Traditional House-Case Study 2

Faraj Al Ansari House | Msheireb, Doha | Built 1935

Connectivity gradually increases from the private rooms on the edges toward the core of the house, where the porch presents an intermediate connection to the highly connective central courtyard. The entry points on the east and south demonstrate low connectivity, responding to the socio-cultural pattern of privacy to avoid direct exposure of the household. Entry points gradually open into the porch, which in turn entirely opens into the main courtyard of the house. This sequence of spatial arrangement reflects the color-coded layout of connectivity. Within the courtyard itself, some areas are less connected than other areas, due to visual barriers and blocks such as small landscape features and palm trees.

: Analysis of Traditional House-Case Study 3

Al Jaber House | Al Asmakh, Doha | Built 1935

This house presents extreme connectivity, where intermediate spaces representing moderate connectivity do not exist. Generally, connectivity in the house is equally divided between the highly connective courtyard and the low connective rooms. This is related to the spacious area covered by the open-air courtyard and the minimal space occupied by rooms and other functional areas.

The main entrance to the south reveals a high connectivity to the rest of the household. Meanwhile, the khokha design of the door prevents direct exposure to the household. Moreover, rooms are located relatively far from the main entry point, reducing exposure and maintaining the family’s privacy.

: Analysis of Traditional House-Case Study 4

Ismail Mandani House | Al Asmakh, Doha | Built 1940

The courtyard exhibits a high connectivity pattern to the surrounding spaces. The rest of the spaces including the entrance in the southwest have low connectivity that might contradict the purpose of an entrance as a point of connection. Considering the socio-cultural pattern of privacy in the spatial form of Muslim homes, “Entrance doors in traditional Muslim homes are placed away from the main street and not directly facing the opposite neighbors” (Othman, Aird, and Buys Citation2015, 15). This architectural idiom is manifested in the Mandani house.

The intermediate spaces of the iwans present a medium-connectivity pattern, which proves their functionality as mediating spaces that utilize the internal configuration of the house to support privacy, rather than imposing temporary solutions such as furniture or screens. In the upper north-western corner, the wide room is used as a garage that opens to the outside and has a low connectivity to the rest of the spaces within the household. In fact, it has recently been transformed into a small trading shop accessible from the street.

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis based on connectivity

Based on the three socio-cultural patterns of privacy, gender segregation and hospitality, the following discussion provides a comprehensive analysis of traditional houses in Qatar based on the index of connectivity. The figure belowpresents the entire collection of house plans including plain and graphically analyzed layouts ().

5.1.1. Privacy

In the traditional house, the pattern of privacy is contemplated via a number of established scenarios of connectivity. The first is gradual connectivity in which the intensity of connective spaces ranges from the least connective private rooms to the most connective central courtyard. This pattern of connectivity directly relates to the socio-cultural pattern of privacy that is supported by the spatial form of the courtyard house and its nuclear arrangement. The location of the courtyard in a protected, privatized core of the household unit enhances its social purpose as an open-air space for gatherings, activities and domestic functions.

The main entrance in the traditional house exhibits a gradual connectivity pattern, as it tends to be less connective near the doorframe and increases in connectivity toward the core of the house or the courtyard through an intermediate narrow corridor. The pattern is clearly consistent with the Islamic and Arab principles of home design, which guarantee family privacy to be maintained from external visual approach by the main entrance through internal architectural configurations.

The second scenario is balanced connectivity, revealing an ideal situation of the traditional house. Most of the rooms surrounding the courtyard are small, narrow, private and arranged in a compact order. This formative configuration results in the possibility for each room to have direct integration with the central, spacious public courtyard. The courtyard as a whole balances the small rooms in terms of cumulative plot area, resulting in a well-balanced and compact housing form.

The third scenario is intermediate connectivity achieved through entrances, porches, corridors, arcades and other intermediate architectural forms. These ensure a fluid connectivity between the open-air courtyard and the surrounding narrow rooms.

The figure below summarizes the comparative assessment of traditional houses in Qatar based on the index of connectivity, highlighting the effect of privacy in relation to how connectivity is analyzed ().

5.1.2. Gender segregation

In the case of traditional houses, the analysis of gender segregation is restricted since the occupants’ gender information is unavailable. However, in some cases, the main courtyard is divided into separated courtyards to serve two families occupying the household. The families belong to the married sons of the house’s owner. This reflects the kinship social structure of the Qatari family, as “the cultural ideal is for a married son to bring his wife to live with and raise a family amongst his birth family” (Nagy Citation2004, 53).

While a woman is not expected to live with her family in her father’s household after marriage, she could maintain a room for occasional use. The son is expected to live with the extended family to maintain social ties and support his parents through aging and retirement. Finances form part of this social arrangement, since at an early stage of his life, the son requires assistance from his family to establish himself until stabilizing his income and gaining an independent financial source.

The second noticeable pattern of gender segregation refers to household entries, which present a low connectivity pattern in most cases. Main entries are designed to prevent exposure of the inner courtyard and the private spaces to the street. Thus, women tend to use a side entry rather than the main entrances, allowing for flexible accessibility while maintaining privacy. This is not specific to Qatari traditional houses, but rather is applicable to many Eastern Muslim societies. In Iraq, for example, “The space of the entrance has been articulated in a way that prevents any kind of direct visual intrusion from the outside toward the main social core of the house associated with the courtyard or the family room” (Al-Thahab, Mushatat, and Abdelmonem Citation2014, 242).

5.1.3. Hospitality

Hospitality is spatially defined by the existence of guest rooms, reception areas, and quarters designated for family friends and visitors who belong to the public realm. In traditional Qatari houses, the Majlis unit represents “masculinity and honor of a Muslim home” (Othman, Aird, and Buys Citation2015, 20). In some cases, the guest section occupies more than one-third of the entire plot area, which could be interpreted as the spatial cost for the preservation of a socio-cultural norm.

In the past, Majlis rooms were usually embedded within the household; however, they were separated and treated as secured spaces (Ferdinand Citation1993). Depending on the family’s wealth and the availability of space, the Majlis room might have been accompanied by a small kitchen in addition to a separated entrance that presents a low connectivity to the household. In the absence of guest rooms, the courtyard itself was the favored space for social gatherings as a result of its open nature and the climatically pleasant atmosphere created around its arcades and porches.

5.2. General discussion

The architectural sociology of housing in the State of Qatar requires further attention due to the challenges associated with the spatial form of housing in the era of globalization. In this respect, the fast process of urbanization introduced to Qatar since the 1940s-1950s contributed to a major shift in housing form and architecture, which resulted in a growing gap between global requirements and local imperatives. Until recently, problems of residential architecture have emerged as the disturbance of the built form, unresponsive foreign plans of residential architecture as well as local dissatisfaction with the poorly integrated contemporary villas that are continuously readapted to meet the socio-cultural needs of their inhabitants.

Socio-spatial relationships in the housing unit highly influence the development of Qatari residential architecture and construction. This is true in the contemporary era, where locally intensive practices are key to reviving the urban identity of cities and settlements. In order to maintain urban identity, both socially and architecturally, the following aspects of housing socio-spatial design should be considered:

The privacy of the housing unit must be maintained through architectural interventions that are designed using careful data collection and precedence analysis, avoiding reactive solutions that result in formative difficulties and inharmonious built form in addition to avoiding loss of architectural solidity and simplicity established in the traditional models of housing in Qatar.

Gender segregation has to be accepted as a cultural norm of Qatari society, despite recent global debates advocating for gender equality and rights in other social and urban contexts (Terlinden Citation2003). It is a social norm that has been long practiced in Qatar in a peaceful, thoughtful manner.

Hospitality is a social pattern that balances privatized living within the household and is a sign of social integrity and acceptance. Since developing from the portable tent, houses in Qatar have been a symbol of generosity and sincerity, where the individual family unit merges with the society through specific-designated spaces. Maintaining the essence of the Majlis unit as a dedicated space for hospitality is significant in maintaining the architectural and social identity of the Qatari society, which supports its sustainability in the future.

Today, trends in sustainable development are promising for a positive change that bears in mind the contextual parameters of urbanism. Residential architecture in Qatar reflects demand for the integration of local culture, heritage and indigenous lifestyles into built form. This is not limited to symbolic embedding of architectural elements; rather, integration requires consideration of local sensitivities early in the gradual process of architectural design. The aim is to regulate the administrative process of residential architecture and design by refining existing building laws to allow the concept of the courtyard house and design-by-privacy to fit into contemporary architecture schemes. In addition, the introduction of policies that enforce the application of socio-cultural patterns in the spatial form of houses would support the creation of an architectural identity in residential units. This would ensure that the built form of Qatar would be in harmony with the local context.

This task is surmountable through the effective coordination and collaboration of governmental agencies, ministries, the public and the private sectors, yet it might be more complicated than simply master planning based on Westernized theories of urbanism. The deliberation of socio-cultural values and local’s way of life shall be a leading key principle in the process of designing for residential architecture, especially when considering the housing dilemma in Doha. The sprawling city is invaded by (i) residential low-density compounds with minimal consideration of the vernacular urban fabric in addition to (ii) five-to-six stories apartment buildings with limited public space in between or surrounded by car parks, which present an inferior urban scheme to a highly responsive socio-cultural fabric.

The foreseen architectural identity represented by the unit of the courtyard house and the wider urban identity of the Qatari traditional neighborhood have been neglected or partially forgotten due to various interdependent factors. Such factors include (i) globalization interpreted as pure speculation/money making process; (ii) the involvement of western practices and practitioners insensitive to the existing urban fabric aided by failed ready-made styles and imported urban schemes as well as (iii) the lack of involvement of local planners, architects, and authorities in the design process. Meanwhile, the future is promising as local, budding Qatari architects and urban designers are now exposed to the general picture of urbanism in an evolving city, where their role is expected to preserve, consolidate, and strengthen architectural and urban identity.

6. Conclusions

The research study examines the socio-cultural aspects embedded in the built form of traditional houses in Qatar, which is a challenging topic of analysis as it has a strong connection to the cultural and social profiles of the society. The analysis supports the social sustainability of architecture in Qatar, marking the progress of housing as a phenomenon contributing to the country’s sustainable urban development.

Through the methodology of space syntax, the research study presents an assessment of traditional houses in Qatar, marking the effect of socio-cultural patterns in the spatial form of houses. The findings uncover the direct effect of the socio-cultural patterns in housing spatial form in the past.

An analysis of traditional houses indicates that the effects of privacy, gender segregation and hospitality have direct effect on the overall built form. Moreover, traditional houses are highly governed by Islamic and cultural norms and represent typical architectural trends.

Acknowledgments

This research study was developed under two grant schemes awarded by Qatar University (Grant ID: QUCG-CENG-1920-4) (Grant ID: QUST-2-CENG-2020-14)

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Qatari University for creating an environment that encourages academic research and unlocks the creative potential of budding researchers.

The research study contributes to knowledge within socio-cultural studies of housing environments in qatar and the middle east region, which faces a rarity of research interest and publication in addition to a lack of local interest and reaction. Most of the studies reviewed in the literature are limited to the typological analysis of residential housing in qatar rather than those that integrate interdisciplinary fields, such as sociology and human behavior studies. The sensitivity of such local-oriented studies requires an inclusive knowledge, unbiased and analytical in order to provide valid interpretation of the issues concerned. Thus, this research study merges the gap between architecture, specifically residential architecture and issues of socio-cultural relevance by providing the missing linkage in the context of qatar.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Asmaa Saleh Al-Mohannadi

Asmaa Saleh AL-Mohannadiis an architect based in Qatar. She holds B.S. Degree in Architecture (2014) and a Master Degree in Urban Planning and Design (2018) from Qatar University. She is undertaking PhD studies at Qatar University.

Raffaello Furlan

Raffaello Furlan is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning (DAUP) at Qatar University. Raffaello Furlan holds Bachelors and Masters Degrees from IUAV University in Venice (Italy), and a PhD in Architecture from Griffith University in Brisbane (Australia). He has held visiting and permanent positions in Australia (University of Queensland and Griffith University in Brisbane), UAE (Canadian University of Dubai) and Qatar (Qatar University). He has been teaching Art History, History of Architecture, Project Management, Urban Design, Architecture Design and Interior Design. His areas of interest include Vernacular Architecture, Architecture and Urban Sociology, Project management, Art History. Member of the Board of Architects in Italy and Australia, he has 20 years professional experience, split between design management, project management and supervision roles, with some highly respected companies, 6 years of which were in Italy, 10 years in Australia, and 4 years in Middle East.

References

- Abdulla, A. 2010. Contemporary Socio-political Issues of the Arab Gulf Moment. London: LSE-London School of Economics.

- Adham, K. 2008. “Rediscovering the Island: Doha’s Urbanity from Pearls to Spectacle.” In The Evolving Arab City: Tradition, Modernity and Urban Development, edited by Y. Elsheshtawy, 218–257. UK: Routledge.

- Ahmed, K. G. 2017. “Designing Sustainable Urban Social Housing in the United Arab Emirates.” Sustainability 9 (8): 1413. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081413.

- Alexander, C., H. Neis, A. Anninou, and I. King. 1987. A New Theory of Urban Design. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Alitajer, S., and G. M. Nojoumi. 2016. “Privacy at Home: Analysis of Behavioral Patterns in the Spatial Configuration of Traditional and Modern Houses in the City of Hamedan Based on the Notion of Space Syntax.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 5 (3): 341–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2016.02.003.

- Alkhalidi, A. 2013. “Sustainable Application of Interior Spaces in Traditional Houses of the United Arab Emirates.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 102: 288–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.743.

- Al-Kolaifi, M. J. 2006. The Traditional Architecture in Qatar. Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts & Heritage.

- Almahmoud, S. 2015. The Majlis Metamorphosis: Virtues of Local Traditional Environmental Design in a Contemporary Context. MFA, Virginia Commonwealth University.

- Alraouf, A. A. 2014. “A Tale of Two Souqs: The Paradox of Gulf Urban Diversity.” Open House International 37 (2): 72–81.

- AL-Rostomani, A. 1997. Dubai and It’s Architectural Heritage. Dubai: Dubai Municipality.

- Al-Thahab, A., S. Mushatat, and M. G. Abdelmonem. 2014. “Between Tradition and Modernity: Determining Spatial Systems of Privacy in the Domestic Architecture of Contemporary Iraq.” International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR 8 (3): 238–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v8i3.396.

- Arslan, H. D., and B. Köken. 2016. “Evaluation of the Space Syntax Analysis in Post-Strengthening Hospital Buildings.” Architecture Research 6 (4): 88–97.

- Aycam, I., and N. Varshabi. 2016. “The Analysis of Form, Settlement Pattern and Envelope Alternatives on Building Cooling Loads in Traditional Yazd Houses of Iran.” Gazi University Journal of Science 29 (3): 503–514.

- Bahammam, A. S. 1987. “Architectural Patterns of Privacy in Saudi Arabian Housing.” Masters, McGill University, Montreal.

- Beattie, A. 2014. “Portfolio: Msheireb.” Accessed 16 September 2018. .http://www.makowerarchitects.com/msheireb.html

- Bekleyen, A., and N. Dalkil. 2011. “The Influence of Climate and Privacy on Indigenous Courtyard Houses in Diyarbakır, Turkey.” Scientific Research and Essays 6 (4): 908–922. doi:https://doi.org/10.5897/SRE10.958.

- Bellal, T. 2004. “Understanding Home Cultures through Syntactic Analysis: The Case of Berber Housing.” Housing, Theory and Society 21 (2): 111–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090410000471.

- Bullivant, L. 2012. Masterplanning Futures. London: Routledge.

- Bus, P., and E. T. Pedraza. 2016. “Lecture 2: Digital Urban Simulation.” iA Chair of Information Architecture. Accessed 29 August 2018. http://www.ia.arch.ethz.ch/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/slides.pdf

- Campo, J. E. 1991. The Other Sides of Paradise: Explorations into the Religious Meanings of Domestic Space in Islam. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

- Chiu, R. L. H. 2004. “Socio‐cultural Sustainability of Housing: A Conceptual Exploration.” Housing, Theory and Society 21 (2): 65–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090410014999.

- CIRS. 2016. “Ibrahim Mohamed Jaidah on “Transitions in Qatar’s Architectural Identity”.” CIRS Newsletter 21: 1–7.

- Cooper, B. M. 1995. “Gender, Movement, and History: Social and Spatial Transformations in 20th Century Maradi, Niger.” Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space 15 (2): 195–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d150195.

- Creswell, J. W. 2003. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

- Dawson, P. C. 2002. “Space Syntax Analysis of Central Inuit Snow Houses.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 21 (4): 464–480. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0278-4165(02)00009-0.

- Dettlaff, W. 2014. “Space Syntax Analysis: Methodology of Understanding the Space.” PhD Interdisciplinary Journal,283–291.

- Douglas, M. 1971. Rules and Meanings: The Anthropology of Everyday Knowledge. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Dunham, D. 1961. “The Courtyard House as a Temperature Regulator.” Athens Center of Ekistics 11 (64): 181–186.

- Dursun, P. 2007. “Space Syntax in Architectural Design.” Paper Presented at the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium, Istanbul.

- Edwards, B., M. Sibly, M. Hakim, and P. Land. 2006. Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and Future. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

- Elblaus, M. 2017. “House of Sand.” Accessed 27 October 2017. http://house-of-sand.tumblr.com;https://www.elblaus.com

- El-Shorbagy, A.-M. 2010. “Traditional Islamic-Arab House: Vocabulary and Syntax.” IJCEE: International Journal of Civil & Environmental Engineering 10 (4): 15–20.

- Excell, K., and T. Rico. 2013. “‘There Is No Heritage in Qatar’: Orientalism, Colonialism and Other Problematic Histories.” World Archaeology 45 (4): 670–685. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2013.852069.

- Farah, E. A., and B. Klarqvist. 2001. “Gender Zones in the Arab Muslim House.” Paper Presented at the 3rd International Space Syntax Symposium, Atlanta, GA.

- Fathy, H. 1986. Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture Principles and Examples with Reference to Hot Arid Climate. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Ferdinand, K. 1993. Bedouins of Qatar. London Thames and Hudson .

- Gehl, J. 2011. Life Between Buildings. Using Public Space. J. Koch, Trans. USA: Island Press.

- Gharib, R. 2014. “Requalifying the Historic Centre of Doha: From Locality to Globalization.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 16 (2): 105–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/1350503314z.00000000076.

- Hanson, M. G. 2008. The Private Sphere: An Emotional Territory and Its Agent. New York: Springer.

- Hillier, B., and J. Hanson. 1984. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jaidah, I. M., and M. Bourennane. 2009. The History of Qatari Architecture from 1800 to 1950 (1 Ed. Milano: Skira Editore.

- Jiang, B., and C. Claramunt. 2002. “Integration of Space Syntax into GIS: New Perspectives for Urban Morphology.” Transactions in GIS 6 (3): 295–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9671.00112.

- Khalili, S. 2012. “The Courtyard House: Using Cultural References of the past as an Alternative to Ottawa’s Current Housing Typologies.” Master of Architecture, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario.

- Knowles, C., and P. Sweetman. 2004. Picturing the Social Landscape: Visual Methods and the Sociological Imagination. London: Routledge.

- Kosk, K. 2016. “Social Participation in Residential Architecture as an Instrument for Transforming Both the Architecture and the People Who Participate in It.” Procedia Engineering 161: 1468–1475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.612.

- Krier, L. 2009. The Architecture of Community. Washington: Island Press.

- Law, R., and K. Underwood. 2012. “Msheireb Heart of Doha: An Alternative Approach to Urbanism in the Gulf Region.” International Journal of Islamic Architec 1 (1): 131–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/ijia.1.1.131_1.

- Lee, J. H., M. J. Ostwald, and H. Lee. 2017. “Measuring the Spatial and Social Characteristics of the Architectural Plans of Aged Care Facilities.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 6 (4): 431–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2017.09.003.

- Lewcok, R., and Z. Freeth. 1978. Traditional Architecture in Kuwait and the Northern Gulf. Kuwait: AARP.

- Maina, J. J. 2013. “Uncomfortable Prototypes: Rethinking Socio-cultural Factors for the Design of Public Housing in Billiri, North East Nigeria.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 3 (3): 310–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2013.04.004.

- Majida, N. H. A., H. Shuichib, and N. Takagi. 2012. “Vernacular Wisdom: The Basis of Formulating Compatible Living Environment in Oman.” Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences 68: 637–648. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.255.

- Major, M. D. 2017. The Syntax of City Space: American Urban Grids. Taylor and Francis.

- Makower, T. 2014. Touching the City: Thoughts on Urban Scale. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons.

- Margulis, S. T. 1977. “Conceptions of Privacy: Current Status and Next Steps.” Journal of Social Issues 33 (3): 5–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1977.tb01879.x.

- mcs.gov.qa. 2016. Accessed 27 March 2017. http://www.mcs.gov.qa

- Michelle, G. 1986. Architecture of the Islamic World. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Mirmoghtadaee, M. 2009. “Process of Housing Transformation in Iran.” Journal of Construction in Developing Countries 14 (1): 69–80.

- Mortada, H. 2003. Traditional Islamic Principles of Built Environment. London: Routledge.

- Nageeb, S. A. 2004. New Spaces and Old Frontiers: Women, Social Space, and Islamization in Sudan. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Nagy, S. 2004. “Keeping Families Together: Housing Policy, Social Strategies and Family in Qatar.” The MIT Electronic Journal of Middle East Studies 4: 42–58.

- Nagy, S. 2006. “Making Room for Migrants, Making Sense of Difference: Spatial and Ideological Expressions of Social Diversity in Urban Qatar.” Urban Studies 43 (1): 119–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500409300.

- Newell, P. B. 1994. “A System Model of Privacy.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 14 (1): 65–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80199-9.

- Newman, L. 2007. Basics of Social Research. 2 ed. Boston: Pearson.

- Nourian, P., S. Rezvani, and S. Sariyildiz. 2013. “Designing with Space Syntax: A Configurative Approach to Architectural Layout, Proposing A Computational Methodology.” Spatial Performance and Space Syntax 1: 1–10.

- Oliveira, V. 2016. Urban Morphology. An Introduction to the Study of the Physical Form of Cities. Switzerland Springer International Publishing.

- Othman, Z., R. Aird, and L. Buys. 2015. “Privacy, Modesty, Hospitality, and the Design of Muslim Homes: A Literature Review.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 4 (1): 12–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2014.12.001.

- Ottsen, C. L., and D. Berntsen. 2013. “The Cultural Life Script of Qatar and across Cultures: Effects of Gender and Religion.” Memory 22 (4): 390–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2013.795598.

- Pahl-Weber, E., S. Seelig, H. Ohlenburg, and N. K. Bergmann. 2013. Urban Challenges and Urban Design. Approaches for Resource-Efficient and Climate-Sensitive Urban Design in the MENA Region. Berlin, Germany: Universitätsverlag der TU Berlin.

- PEO. 2015. Old Houses in Al-Asmakh Area (Report). البيوت القديمة في منطقة الأصمخ. Doha, Qatar: Private Engineering Office. Qatar: Doha.

- Petruccioli, A. 2008. “House and Fabric in the Islamic Mediterranean City.” In The City in the Islamic World, edited by S. K. Jayyusi, 851–875. Vol. 2. Boston: Brill, Hotei Publishing.

- qm.org.qa. 2016. Accessed 27 March 2017. http://www.qm.org.qa/en

- QNDF. 2014. Qatar National Development Framework 2032 (Report). Doha, Qatar: The Ministry of Municipality and Environment.

- Ragette, F. 2006. Traditional Domestic Architecture of the Arab Region. Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges.

- Ratti, C. 2004. “Space Syntax: Some Inconsistencies.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31 (4): 501–511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/b3019.

- Remali, A. M., A. M. Salama, F. Wiedmann, and H. G. Ibrahim. 2016. “A Chronological Exploration of the Evolution of Housing Typologies in Gulf Cities.” City, Territory and Architecture 3 (14): 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-016-0043-z.

- Salama, A. 2006. “A Typological Perspective: The Impact of Cultural Paradigmatic Shifts on the Evolution of Courtyard Houses in Cairo.” METU-JFA 23 (1): 41–58.

- Salama, A. M. 2003. “The Courtyard House: Memory of Places Past.” Architecture Plus 3: 140–143.

- Salama, A. M. 2013. Lecture 2: Socio--‐Cultural/Socio--‐Behavioral Phenomena. ARCT 420: Environment--Behavior Studies. Lecture Notes. Department of Architecture and Urban Planning. Qatar: Qatar University.

- Sayigh, A., and H. Marafia. 1998. “Chapter 2—Vernacular and Contemporary Buildings in Qatar.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2 (1–2): 25–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-0321(98)00010-0.

- Smith, R., and V. Bugni. 2002. “Architectural Sociology and Post-modern Architectural Forms.” Accessed October 2017. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/sociology_pubs/4

- Sobh, R., and R. W. Belk. 2011. “Privacy and Gendered Spaces in Arab Gulf Homes.” Home Cultures 8 (3): 317–340. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/175174211X13099693358870.

- Soflaei, F., M. Shokouhian, and W. Zhu. 2017. “Socio-environmental Sustainability in Traditional Courtyard Houses of Iran and China.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 69: 1147–1169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.130.

- Spain, D. 1992. Gendered Spaces. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Talib, K. 1984. Shelter In Saudi Arabia. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Terlinden, U. 2003. City and Gender: International Discourse on Gender, Urbanism and Architecture. Shanghai: Leske + Budrich, Opladen.

- Turner, A. (May 2011). “Depthmap: A Program to Perform Visibility Graph Analysis.” Paper Presented at the 3rd International Symposium on Space Syntax, Georgia Institute of Technology.

- UCL. 2018. “Space Syntax_Online Training Platform.” Accessed 21 September 2018. http://otp.spacesyntax.net

- Weber, W., and S. Yannas. 2014. Lessons from Vernacular Architecture. 1 ed. New York: Routledge.

- Westin, A. 1970. Privacy and Freedom. New York: Ballantine.

- Xia, X. 2013. A Comparison Study on A Set of Space Syntax Based Methods. Sweden: Masters in Geomatics and Land Management, University of Gavle.

- Yin, R. K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: Thousand Oaks.

- Zeisel, J. 1975. Social Science Frontiers.Sociology and Architectural Design. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Zhang, D. 2016. Courtyard Housing and Cultural Sustainability: Theory, Practice, and Product. NY: Routledge.