ABSTRACT

Researchers believe that the architecture of residential halls has a significant impact on various aspects of students’ lives, especially on the quality of their education. The purpose of this study was to extract and evaluate residential preferences affecting the architecture of dormitories for students in dormitories at University of Mohaghegh Ardabili in Iran. The seven extracted indicators formed the basis of the researcher-made questionnaire with 35 questions. Pre-tests were performed at University of Mohaghegh Ardabili and its Cronbach’s alpha was obtained with a coefficient of 0.930. The size of the study sample was 250 students from among students, which was confirmed by Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) method. The analysis of the exploratory factors was examined by two software 8.8 Lisrel and 26 SPSS and by the factor model test of the second order and the binomial test (ratio). We concluded that students’ residential preferences in the case study include indicators of dimensions, service and welfare, location, privacy, landscape, flexibility, and materials with a positive and direct impact. Statistical analysis showed that flexibility is the most important indicator and landscape is the least important indicator for students.

1. Introduction

Student dormitories in universities are of paramount importance after education. Dormitories replace the students’ home at certain times and are a reflection of the home environment for them. These residences must meet the needs of students and their parents and respond to the demands of their social lives (Hill Citation2007). The lives of university students in the residential environment, both inside and outside the university, have been of interest to many researchers for decades (Lundgren and Schwab Citation1979; High and Sundstrom Citation1977; Case Citation1981; Popelka Citation1994; Rinn Citation2004). Student accommodation has long been one of the basic facilities provided by higher education institutions to help students expand their intellectual abilities (Najib and Abidin Citation2011). For many students, entering college is the beginning of a new phase in life which includes the experience of living in dormitory. Research has shown that the living environment and the changes that take place in it affect people’s emotional state (Amole Citation2012). When students leave home to attend university, most of them have to keep their expenses to a minimum, and dormitories are very helpful in achieving this goal (Khozaei, Ramayah, and Hassan Citation2012). Also, due to the feeling of more security and the supervision of the dormitory officials, the students’ accommodation in the dormitory is more acceptable for their parents. Therefore, many students prefer to live in university dormitories. However, the issue of costs and economic savings has led to a minimalist view of the design of dormitories, which is why most dormitories do not qualitatively meet the housing and educational needs of students. Because of their importance, researchers have studied the effects of dormitories on students (Cross, Zimmerman, and O’Grady Citation2009; LaNasa, Olson, and Alleman Citation2007). A university dormitory is a special type of building that is expected to be both a haven for students and a comfortable and functional environment for learning and academic success (Hassanain Citation2007). In other words, dormitories have limited space to meet the needs of students, such as sleeping, eating, studying, and social activities. So, Students need to adapt to this new situation that is different from their homes (Khozaei, Hassan, and Abd Razak Citation2011). Today, university dormitories, often referred to as dormitories, are less likely to meet the needs of students. An overview reveals that the architecture of dormitory buildings in most universities is designed and implemented more to meet the basic needs of students and with less attention to the qualitative dimensions and aspects related to their mental conditions. When resources are limited and a minimalist approach is applied, customer preferences from among the available options help the designer prioritize design options. Because financial resources are limited for the design and architecture of student dormitories, designers and planners have to choose cost-effective options in areas, interior divisions, forms, building materials, furniture, and more. In the meantime, if architects are aware of students’ residential preferences, there will be more coordination between the preferences of designers and planners and the preferences of residents and dormitory users. This study seeks to fill part of this study gap.

Researchers support the idea that the dormitory environment has a profound effect on students (Cross, Zimmerman, and O’Grady Citation2009; Blimling Citation1989). Even some studies have shown that residential halls may affect students’ progress, behaviour, and academic performance (Foubert, Tepper, and Morrison Citation1998; de Araujo and Murray Citation2010). In fact, the significant impact of residential halls may explain the myriad studies of students’ lives, inside or outside the university, over the past decades (Cross, Zimmerman, and O’Grady Citation2009; Najib and Abidin Citation2011; Ge and Hokao Citation2006; Thomsen Citation2008, Citation2007; Paine Citation2007; Amole Citation2005). If students’ preferences and differences and similarities between people are ignored by the designer, dissatisfaction will arise and serious emotional and psychological complications will occur. Also, the academic level of students can be adversely affected by the dormitory environment. The results of Masoudi and Mohammadi’s research showed a significant difference between dormitory and non-dormitory students in terms of academic grade (Masoudi and Mohammadi Citation2007). Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention the students’ housing preferences and to investigate them in order to better understand their real demands and requirements (Khozaei, Hassan, and Abd Razak Citation2011). If architects and planners are aware of students’ residential preferences, they will be able to use architectural design methods to enhance the quality of living in student dormitories. Ignoring these priorities and differences can leave irreparable damage to the quality of education. Thus, accommodation can affect students’ growth, behavior, and even academic performance (Foubert, Tepper, and Morrison Citation1998; de Araujo and Murray Citation2010). Students who have difficulty adjusting to university conditions unfortunately deal with various complications viz. academic failure and low progress, dropout, anxiety, depression, isolation and drug abuse (Jiboye Citation2010).

The research hypothesis is that residential preferences affecting the architectural design of dormitories can be collected and prioritized from the perspective of students. In addition, simulating a dormitory with a student’s previous home is the researcher’s primary assumption of student preferences. The purpose of this study is to extract residential preferences that affect the architectural design of dormitories and measure their importance in terms of students living in the case study. This research is of descriptive-analytical type and statistical population of students living in dormitories of Ardabil State University in Iran. The number of dormitory residents is 1536 and the statistical sample are 250 students were selected from among students living in the dormitory, which will be selected by multi-stage cluster random sampling. The sample size will be evaluated and confirmed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) method.

2. Theoretical foundations

Residential preferences: Some researches consider the impact of demographic background on respondents to be the touchstone of their preferences. On a large scale, residential preferences include time, place, money, and social relationships (Heaton et al. Citation1979) Size of living space (Wang and Li Citation2006; Sirgy, Grzeskowiak, and Su Citation2005; Hempel and Tucker Citation1979; Hwang and Albrecht Citation1987), functional compatibility (Lindberg, Gärling, and Montgomery Citation1989), and neighborhood characteristics (Devlin Citation1994; Jim and Chen Citation2007). Housing preferences factors for accommodation include the quality of the outdoor environment (Thamaraiselvi and Rajalakshmi Citation2008), location (Wu Citation2010; Karsten Citation2007; Devlin Citation1994), neighborhood characteristics (Sirgy, Grzeskowiak, and Su Citation2005), surrounding landscape (Beals Citation2000), feeling of security and proximity to the city, public transport, closeness to the workplace, safety, medical and educational facilities (Ghani, Suleiman, and Malaysia Citation2016). Thomsen (Citation2007) in her qualitative study entitled “Home Experiences in Student Housing: About Institutional Personality and Temporary Houses” showed that aspects of student housing architecture and their resemblance to their homes affect their residential preferences. Thomsen’s study reveals that “the possibility of personalizing private rooms to create a sense of home” is highly desirable for students (Thomsen Citation2007).

Student Residence: Housing is the foundation of human-environmental interaction that can be the basis of a happy, productive and successful life (Yusuff Citation2011; Cagamas Citation2013; Masoudi and Mohammadi Citation2007). A student residence is a housing unit where students live during their student days (Khozaei et al. Citation2010). In other words, the student residence is the housing unit of the students who live there to study. Many young students leave home and their parents and live in dormitories where there is no longer any parental supervision and control. This is a new situation to experience a different lifestyle. This is a new situation for experiencing a different lifestyle in which the student must learn to be independent, to compromise with others, to develop citizenship and to use common space and facilities, and to go through this stage of transition to adulthood (Zaransky Citation2006; Ja’afar Citation2012; Ge and Hokao Citation2006; Rodger and Johnson Citation2005). Student housing also has a profound effect on students’ overall political and social lives, such as leadership development, behavior, academic performance, citizenship, and a sense of solidarity. As a learning environment, student accommodation integrates social and psychological functions to meet students’ needs, aspirations, and expectations (Khozaei et al. Citation2010). Most students are about eighteen years old, and many have never left home or experienced a previous dormitory. Thus, staying away from family for a long time is a lasting experience for young students because it is an opportunity to learn the ethics of life and how to live independently, how to deal with other students who are not relatives and everyone has to share a bathroom and toilet and a common space with others (Ciarrochi and Scott Citation2006). In addition, the type and layout of living in the dormitory, which can be called a shared bedroom, allows students to live and work together in a university community, in addition to their academic activities, and to fully embrace the academic ethics that lead to promoting citizenship and leadership (Ademiluyi and Raji Citation2008).

3. Literature review

However, much research on student housing covers a wide area (Hassanain Citation2008; Cross, Zimmerman, and O’Grady Citation2009; de Araujo and Murray Citation2010), But there is a paucity of research on students’ housing preferences and their real needs and requirements-especially in the samples available in Iran and in comparison, with different cultures and societies (Khozaei, Hassan, and Abd Razak Citation2011). The lack of scientific works in this field may be due to the lack of theoretical foundations, relevant research tools, as well as unknown basic factors. The following are some examples of research conducted related to students’ residential preferences and their findings are shown in :

Table 1. Research background of residential preferences of students living in dormitories

4. Methodology and case study

The initial assumption of the research was based on the similarity between the dormitory and the house, so that the residents of the dormitories prioritize factors in their preferences that give them a sense of home. In other words, students prefer to live in residential halls instead of places that have established characteristics. In order to conduct research, we extract from the articles, books and dissertations as well as face-to-face interviews with the students living in the dormitory the main indicators in conceptualizing the feeling of being at home in the dormitory. Hence, student housing preferences are primarily associated with these aspects. Afterwards, the literature correlated with the analyses and the results of the interview are examined in a case study to form the ultimate indicators from the perspective of the statistical society and a set of items under each index. For this purpose, the authors referred to the dormitories of Mohaghegh Ardabili University considering that one of the authors was the director of the dormitory department of Mohaghegh Ardabili University for 4 years and the other stayed in the dormitories of the university for 2 years. The authors “interviews with present residents based on these experiences helped refine the principal indicators and extract the final list, including seven indicators for students” residential preferences. These indicators were the main basis of the researcher-made questionnaire, which was divided into 35 questions in two sections. In the first part, students’ preferences were selected between the two options,Footnote1 and in the second part, the importance of each question was scored from 0 to 100. The next step is to verify the content validity of the questionnaire. Once the initial researcher-made questionnaire was prepared and the items were classified under each structure, it was sent to some experts who were involved in analogous researches at Mohaghegh Ardabili University and some other universities. Moreover, for pre-test, 30 undergraduate and graduate students living in Mohaghegh Ardabili University dormitories were asked to peruse and evaluate the questionnaire. That’s about 10 percent of the population. A statistician at Mohaghegh Ardabili University was also asked to evaluate the questions. The questionnaire also includes eight background questions about age, number of people in the room, length of stay, income, job, marital status, field of study and level of education of students. Exploratory factor analysis is performed with 8.8 Lisrel and 26 SPSS software. The process of the research is shown in .

The dormitories inside Mohaghegh Ardabili University campus were selected as a case study. The required sample size was obtained by (KMO) method. The questionnaire was distributed among 250 students living in the dormitory. The residence of one of the authors in these dormitories and therefore easy access to them, as well as the sense of cooperation between students and most importantly the physical similarity of the dormitory complex with the general characteristics of dormitory construction in most Iranian universities, are the reasons for choosing this dormitory. In , the study area has been determined.

5. Findings

Since the housing preference factor was a hidden variable and was directly measurable, from the confirmatory factor analysis of the second time and with Lisrel software the version 8.80, we analyzed the data. We first examined whether the factor analysis model was appropriate for this study. The adequacy of the sample size was confirmed based on the (KMO) index, and the appropriateness of factor analysis was assessed using the Bartlett test. SPSS software outputs have been reported to be appropriate for the use of factor analysis model in . According to these results, because the value of the KMO index is 0.853 and close to 1, therefore, the amount of sample size is optimal for performing factor analysis model.

Table 2. SPSS software results for the appropriate use of factor analysis model

Also, according to the results reported in , since the Cronbach’s alpha values for the two factors “location” and “vision” are 0.681, and 0.659 respectively, hence they are larger than 0.65, the reliability of the structure of this factor is satisfactory. This coefficient is greater than 0.7 for the rest of the factors, which indicates that the reliability of the structures of these factors is good enough and means that the questions related to the factors had a decent fit. Note that the first question of the location factor, which is related to the type of warehouse, was trimmed due to the increased reliability of the structure. In total, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the whole questionnaire is 0.930 (approximately). Therefore, the reliability of the structures of the whole questionnaire is also sensational.

Table 3. Reliability of the questionnaire used in the research

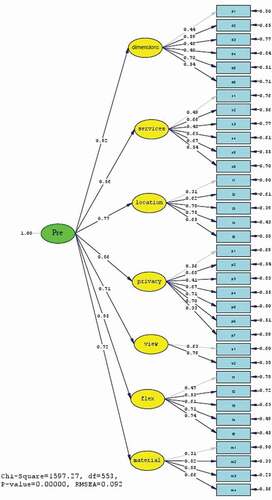

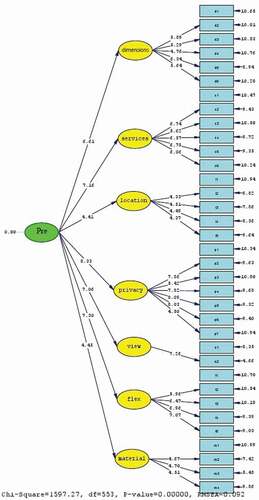

In the following, the data of this research are analyzed in Lisrel software and the second factor analysis is used for it. The results obtained for the studied model, which include all the hypotheses of this study, are presented in . shows the amount of factor loads (impact values) of each factor and is related to their T-statistics. If the T statistical values between the two factors or variables are less than 1.96, it indicates that there is no relation between those two factors or variables.

The output of the factor values and the T statistic is summarized in .

Table 4. Factor load value, T-statistic related to the consequence index

According to , among the sub-variables of the dimension factors, table dimensions are in the first priority of students. Therefore, it has had the greatest effect on students’ residential preferences in this factor. In the service and welfare factor, the type of building and its newness are more important for students and have the greatest impact on their residential preferences. In location factor, the location of sports spaces is the first priority of students and has the greatest impact on their residential preferences in this factor. In the privacy factor, the first priority is to have access to the dormitory building and it has the greatest impact on the students’ residential preferences in this factor. In the vision factor, the room lighting variable is more important and the first priority of students in this factor. In the flexibility factor, the flexibility of the library space is the first priority and has the greatest impact on students’ residential preferences. In terms of materials, room color is the first priority and has the greatest impact on students’ residential preferences. In accordance with the results of the 8.08 Lisrel software for the second-order factor analysis model, because all T-statistics for all factors in the overall factor of residential preferences have values greater than 1.96, all of the above factors, in addition to affecting the residential preferences of dormitory students, are also significantly affected by a more general factor called residential preferences. In other words, the effect of factors on residential preferences is twofold. That is, the preferences preferred by students regarding the main factors such as dimensions, location, privacy, etc. affect the residential preferences, the factor of residential preferences also affects the prioritization of students in the tested dimensions and increase or decrease the amount of all factors including dimensions, services and It affects well-being, location, privacy, visibility, flexibility and materials. This, as noted earlier, is due to the fact that the residential preference factor is a latent variable and can be measured directly. To clarify the issue, the factor of residential preferences in terms of concept is equivalent to the priorities that students give to research variables. In other words, we consider the set of 7 factors with their sub-variables to be the same set of student residential preferences that are broken down into smaller components that can be considered in architectural design.

According to , all 7 main factors in the set of residential preferences of students have a positive and significant effect. That is, if we consider the set of 7 factors with their subset variables as the set of students’ residential preferences, all factors play a positive and significant role in this set. Thus, all factors are effective in prioritizing and selecting and preferring students. However, the most important factor influencing this set is the flexibility factor, the operating load of which is 0.95 and then the dimensions and services and welfare are in the next ranks in terms of importance, respectively. The least important factor is the view and landscape on students’ residential preferences. In the following, we examine the preferences of dormitory students using a two-sentence test (ratio test). The authors are well aware that respondents are normally inclined to prefer more facilities, and it is predictable that they may choose statements with favorable residential conditions. So, the authors tried to avoid such questions as much as possible. Respondents had to choose from options that had both advantages and disadvantages so that it is not easy to distinguish between the two options and prefer one over the other. Comparing the options presented in for each question clarifies the issue.

Table 5. Route coefficients, T-statistic and Significance of general structural equation model

Table 6. The values of the factor load of the T-statistics related to the consequence index

Zero test assumption: Up to 50% of students prefer the first option in each question.

Assumption 1 of the test: more than 50% of students prefer the first option in each question.

The results of the two-sentence test for each question from the SPSS software are summarized in .

Given the level of significance of the answers in , we conclude that in most cases the tendency of students to one of the options is greater. It is noteworthy that in some variables, such as the way students are placed in buildings and the color of the furniture, they do not prefer any of the options over the other.

6. Discussion

In accordance with the purpose of the research, seven principal physical indicators affecting students’ residential preferences were educed based on existing principles and resources. According to the analysis of the data collected from Mohaghegh Ardabili University, the seven main indices are effective in residential preferences and the effectiveness of each factor has been obtained. In the following, by comparing similar researches, we compare and discuss their findings with our research findings.

Khozaei, Hassan, and Abd Razak (Citation2011) conducted a study on residential preferences in student dormitories and achieved 8 main indicators. The conceptual framework of this research lies in the similarity of the residence hall with the students’ own house. It was conceptualized that students’ residential preferences could be defined in terms of eight key factors: visual, installations, facilities, location, personalization, room lighting, social interaction, security, and privacy. The findings and physical indications of this study are consistent with our findings.

Oppewal et al. (Citation2017) in their research achieved certain criteria in students’ residential preferences. The results of a sample of undergraduate and graduate students at a university in the United Kingdom showed that students are sensitive to the distance between shower and toilet facilities from the university and sharing these facilities with other students. The size of the room (four to nine square meters) is the most influential feature, after which a mixture of gender and a combination of students of different levels can be seen on the living floor. Landscapes are less important than rooms. Landscapes are less important than rooms, although the importance of landscapes is still significant. The results of this study are consistent with our research on the high importance of dimensions and sizes and the relatively low importance of landscape.

Research conducted by Muizz and Hassanain (Citation2016) has shown that student housing facilities are directly related to the efficiency, health and well-being of the students who use them. The findings show that the most important issues include the operation and control of thermostats, the quality of building support services, the size of rooms, furniture and proximity to the cafeteria. The results of this study are consistent with our research, except for the control of thermostats, which was not relevant in our study due to the low energy cost in Iran.

Nijënstein et al. (Citation2015) found interesting results by examining the issue beyond demographic factors, and using different criteria for residential preferences and considering the orientation of human values as a predictor in students’ housing preferences. This suggests that changes should be considered when designing a new student housing. In particular, housing features such as kitchen, bathroom and price are usually heterogeneous. This suggests that student housing should be different in these characteristics. Instead, the outdoor and walking space features show a slight heterogeneity, which suggests that these are not important to students. As a result, these housing features may be secondary to the development of new student housing projects. We found out that both social demographics and human value orientation could explain at least part of the heterogeneity of choices. The findings of this study are consistent with those of our research. Also, due to the free accommodation of public universities, price and cost are not relevant in our case study.

Khozaei, Ramayah, and Hassan (Citation2012) in a re-examination on the subject of residential preferences and obtaining the relevant factors and summarizing their previous research were able to reduce the factors obtained in their previous research and re-examined other factors and concluded that A typical lounge rarely satisfies all kinds of students. Therefore, the characteristics of a living room that are adequate for students should be found in the students’ own responses. They reduced the number of factors to 6, namely, facilities (5 items), visual (7 items), room comfort (5 items), location (4 items), social contact (3 items) and security (4 items).All of these studies confirm the validity of the criteria obtained by the authors of this paper. These cases are consistent with the seven main indicators of our research.

7. Conclusion

Students’ accommodation preferences in the dormitory depend on a number of factors. Physical factors, among all the factors influencing the case study and 7 main indicators were obtained, according to the results of the research, all seven main indicators have a direct and positive effect on students’ residential preferences. Among them, the factor of flexibility with a factor loading of 0.95 and a statistic of T 7.30 were evaluated as the most important factor in students’ residential preferences. After flexibility, dimensional factor with factor loading of 0.92 and statistic of T 6.61, service factor and welfare with factor loading of 0.86 and statistical load of T 7.16, then privacy with factor loading of 0.86 and statistic of T 8.33 were more important than other factors, respectively. According to the students, the least important factor among the 7 main factors of this research is the perspective and landscape factor with a factor loading of 0.71 and a statistic of 7.06. In general, students prefer that the dormitory spaces be more flexible and that there is a multi-purpose use of the spaces as well as the possibility of a variety of activities in the limited dormitory spaces. Also, for students, the factor of dimensions after flexibility is more important than other factors. Considering that this research was conducted on current students living in dormitories, it can be said that the dimensions of the spaces were different from their desired dimensions and the students’ choice was another type of division and allocation of spaces to uses within the same general area.

In the following, the importance of each of the sub-variables of the main indicators is obtained. For example, among the sub-variables of the flexibility factor, the flexibility of the library space is the first priority and has the greatest impact on students’ residential preferences. These results, as well as the results of the final stage of the research on student preference among the two descriptive options with advantages and disadvantages, help the architect to present their suggestions with knowledge of students’ preferences and choices. Also, compared to other similar studies, most of the factors and findings of this study were consistent with others, but some factors such as air temperature regulation inside the dormitory and accommodation costs were not relevant due to cheap energy and free student accommodation in Iran.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mohammadreza Daliri Dizaj

Mohammadreza Daliri Dizaj Grauated Of Master Of Architecture In 2021 From University Of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. He Received his Bachelor Of Architecture In 2018 From Payam Noor of Kashan University, Kashan, Iran. His Main Research Experience Is about of Students’ Residential and University issues.

Tohid Hatami Khanghahi

Tohid Hatami Khanghahi Graduated of master of architecture in 2001 from Imam Khomeini international university, Qazvin, Iran. He was faculty member of the architecture department at university of mohaghegh ardabili from 2001 to 2010. He received his PhD in 2015 from Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran. Since 2015, he has been a faculty member and from 2016 until now, the supervisor of architecture department at university of mohaghegh ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

Notes

1 In designing the questionnaire and asking questions, we faced some problems. In asking some questions and expressing two situations, it was already obvious that the respondents would opt for the one that has better facilities and conditions. In this case, the nature of the question was challenged and it seemed altogether nonsensical. For such questions, we tried to present each question in a specific financial range in addition to providing a possibility and advantage in each situation so that the audience could choose one by juxtaposing the advantages and disadvantages of each option. These options are such that it is not possible to distinguish between the two options and choose one over the other for the architect design as a suggestion for others.

References

- Ademiluyi, I. A., and B. A. Raji. 2008. “Public and Private Developers as Agents in Urban Housing Delivery in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Situation in Lagos State.” Humanity & Social Sciences Journal 3 (2): 143–150.

- Amole, D. 2005. “Coping Strategies for Living in Student Residential Facilities in Nigeria.” Environment and Behavior 37 (2): 201–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916504267642.

- Amole, D. 2009. “Residential Satisfaction in Students’ Housing.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 29 (1): 76–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.05.006.

- Amole, D. 2012. “Gender Differences in User Responses to Students Housing.” Procedia-social and Behavioral Sciences 38: 89–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.328.

- Beals, B. L. 2000. “Life in a Box: The Psychological Effects of Dormitory Architecture and Layout on Residents.” Astudent’s Guide to First Year Composition 2001. 153-168.

- Berhad, C. H. 2013. Housing the Nation: Policies, Issues and Prospects. Kuala Lumpur: Cagamas Holdings Berhad.

- Blimling, G. S. 1989. “A Meta-analysis of the Influence of College Residence Halls on Academic Performance.” Journal of College Student Development. 30 (4): 298-308.

- Case, F. D. 1981. “Dormitory Architecture Influences: Patterns of Student Social-relations over Time.” Environment and Behavior 13 (1): 23–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916581131002.

- Ciarrochi, J., and G. Scott. 2006. “The Link between Emotional Competence and Well-being: A Longitudinal Study.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 34 (2): 231–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880600583287.

- Cross, J. E., D. Zimmerman, and M. A. O’Grady. 2009. “Residence Hall Room Type and Alcohol Use among College Students Living on Campus.” Environment and Behavior 41 (4): 583–603. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508328169.

- de Araujo, P., and J. Murray. 2010. Estimating the Effects of Dormitory Living on Student Performance. Available at SSRN 1555892.

- Devlin, A. S. 1994. “Children’s Housing Style Preferences: Regional, Socioeconomic, Sex, and Adult Comparisons.” Environment and Behavior 26 (4): 527–559. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659402600404.

- Foubert, J. D., R. Tepper, and D. R. Morrison. 1998. “Predictors of Student Satisfaction in University Residence Halls.” Journal of College and University Student Housing 27 (1): 41–46.

- Ge, J., and K. Hokao. 2006. “Research on Residential Lifestyles in Japanese Cities from the Viewpoints of Residential Preference, Residential Choice and Residential Satisfaction.” Landscape and Urban Planning 78 (3): 165–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.07.004.

- Ghani, Z. A., N. Suleiman, and H. O. Malaysia. 2016. Theoretical Underpinning for Understanding Student Housing. Jouranl of Enviroment and Earth Science6 (1): 163-176.

- Hassanain, M. A. 2007. “Post-occupancy Indoor Environmental Quality Evaluation of Student Housing Facilities.” Architectural Engineering and Design Management 3 (4): 249–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2007.9684646.

- Hassanain, M. A. 2008. “On the Performance Evaluation of Sustainable Student Housing Facilities.” Journal of Facilities Management 6 (3): 212–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/14725960810885989.

- Heaton, T., C. Fredrickson, G. V. Fuguitt, and J. J. Zuiches. 1979. “Residential Preferences, Community Satisfaction, and the Intention to Move.” Demography 16 (4): 565–573. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2060936.

- Heidari, A. A., and F. Nekooeimehr. 2013. “An Investigation of the Relationship between Sense of Place and Place Attachment among Dormitory Students.” Iran University of Science & Technology 23 (2): 121–131.

- Heidari, A. A., and Z. Abdipour. 2015. “Evaluation of the Role of Privacy in Promoting Attachment to Places in Students’ Dormitories.” Journal of Fine Arts-Architecture and Urban Development 20 (4): 86–73.

- Hempel, D. J., and L. R. Tucker Jr. 1979. “Citizen Preferences for Housing as Community Social Indicators.” Environment and Behavior 11 (3): 399–428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916579113005.

- High, T., and E. Sundstrom. 1977. “Room Flexibility and Space Use in a Dormitory.” Environment and Behavior 9 (1): 81–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001391657791005.

- Hill, C. 2007. “What’s Coming Next? Shaping the Future on Campus.” Collage Planning & Management. 1 (1): 27-43.

- Hwang, S. S., and D. E. Albrecht. 1987. “Constraints to the Fulfillment of Residential Preferences among Texas Homebuyers.” Demography 24 (1): 61–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2061508.

- Ja’afar, W. N. H. W. 2012. “Hostel Management System (HMS).” Unpublished Thesis for Bachelor of Computer Science (Software Engineering), Faculty of Computer Systems & Software Engineering, University Malaysia Pahang.

- Jiboye, A. D. 2010. “The Correlates of Public Housing Satisfaction in Lagos, Nigeria.” Journal of Geography and Regional Planning 3 (2): 017–028.

- Jim, C. Y., and W. Y. Chen. 2007. “Consumption Preferences and Environmental Externalities: A Hedonic Analysis of the Housing Market in Guangzhou.” Geoforum 38 (2): 414–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.10.002.

- Karsten, L. 2007. “Housing as a Way of Life: Towards an Understanding of Middle-class Families’ Preference for an Urban Residential Location.” Housing Studies 22 (1): 83–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030601024630.

- Khan, E. H. K., S. A. A. Yazdanfar, and A. Ekhlasi. 2018. “Important Elements of Private Dormitory Spaces.” Educational Review: International Journal 15 (2): 75-86.

- Khozaei, F., A. S. Hassan, and N. Abd Razak. 2011. “Development and Validation of the Student Accommodation Preferences Instrument (SAPI).” Journal of Building Appraisal 6 (3–4): 299–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/jba.2011.7.

- Khozaei, F., N. Ayub, A. S. Hassan, and Z. Khozaei. 2010. “The Factors Predicting Students’ Satisfaction with University Hostels, Case Study, Universiti Sains Malaysia.” Asian Culture and History 2 (2): 148. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/ach.v2n2p148.

- Khozaei, F., T. Ramayah, and A. S. Hassan. 2012. “A Shorter Version of Student Accommodation Preferences Index (SAPI).” American Transactions on Engineering & Applied Sciences 1 (3): 195–211.

- Kılıçaslan, H. 2013. “Design of Living Spaces in Dormitories.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 92: 445–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.699.

- LaNasa, S. M., E. Olson, and N. Alleman. 2007. “The Impact of On-campus Student Growth on First-year Student Engagement and Success.” Research in Higher Education 48 (8): 941–966. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-007-9056-5.

- Lindberg, E., T. Gärling, and H. Montgomery. 1989. “Belief-value Structures as Determinants of Consumer Behaviour: A Study of Housing Preferences and Choices.” Journal of Consumer Policy 12 (2): 119–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00412067.

- Lundgren, D. C., and M. R. Schwab. 1979. “The Impact of College on Students: Residential Context, Relations with Parents and Peers, and Self-esteem.” Youth & Society 10 (3): 227–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X7901000301.

- Masoudi, A., and M. Mohammadi. 2007. “Examining the Effects of Residence and Gender on College Student Perceptions and Academic Preference.” Journal of Social and Humanity of Shiraz University 25 (4): 185-200.

- Nadimi, H., M. F. H. Abadi, and M. N. Pour. 2013. “The Effect of Landscape and Design of Dormitory Environments on Students’ Satisfaction (Case Study: Dormitories of Hakim Sabzevari University of Sabzevar).” Environmental Journal 1: 94–86.

- Najib, N. U. M., and N. Z. Abidin. 2011. “Student Residential Satisfaction in Research Universities.” Journal of Facilities Management. 9 (3): 200-212.

- Nijënstein, S., A. Haans, A. D. Kemperman, and A. W. Borgers. 2015. “Beyond Demographics: Human Value Orientation as a Predictor of Heterogeneity in Student Housing Preferences.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 30 (2): 199–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-014-9402-9.

- Oladiran, O. J. 2013. “A Post Occupancy Evaluation OF Students’ Hostels Accommodation.” Journal of Building Performance 4 (1): 33-43.

- Oppewal, H., Y. Poria, N. Ravenscroft, and G. Speller. 2017. “Student Preferences for University Accommodation: An Application of the Stated Preference Approach.” Housing, Space and Quality of Life Chapter 9: 113–124

- Paine, D. E. 2007. An Exploration of Three Residence Hall Types and the Academic and Social Integration of First Year Students. University of South Florida.

- Popelka, D. M. 1994. Residence Hall Retention: Factors that Influence an Upperclassman’s Choice of Housing. Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. Lowa State University.

- Rinn, A. 2004. “Academic and Social Effects of Living in Honors Residence Halls.” Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council--Online Archive 5 (2): 67-80.

- Rodger, S. C., and A. W. Johnson. 2005. “The Impact of Residence Design on Freshman Outcomes: Dormitories versus Suite-Style Residences.” Canadian Journal of Higher Education 35 (3): 83–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v35i3.183515.

- Sanni-Anibire, M. O., and M. A. Hassanain. 2016. “Quality Assessment of Student Housing Facilities through Post-occupancy Evaluation.” Architectural Engineering and Design Management 12 (5): 367–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2016.1176553.

- Sirgy, M. J., S. Grzeskowiak, and C. Su. 2005. “Explaining Housing Preference and Choice: The Role of Self-congruity and Functional Congruity.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 20 (4): 329–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-005-9020-7.

- Thamaraiselvi, R., and S. Rajalakshmi. 2008. “Customer Behavior Towards High Rise Apartments: Preference Factors Associated with Selection Criteria.” ICFAI Journal of Consumer Behavior 3 (3): 15-30.

- Thomsen, J. 2007. “Home Experiences in Student Housing: About Institutional Character and Temporary Homes.” Journal of Youth Studies 10 (5): 577–596. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260701582062.

- Thomsen, J. 2008. Student Housing–Student Homes?: Aspects of Student Housing Satisfaction. Fakultet for arkitektur og billedkunst. Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- Thomsen, J, Eikemo, T. A. 2010. “Aspects of student housing satisfaction: a quantitative study.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. 25(3): 273–293.

- Wang, D., and S. M. Li. 2006. “Socio-economic Differentials and Stated Housing Preferences in Guangzhou, China.” Habitat International 30 (2): 305–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2004.02.009.

- Wu, F. 2010. “Housing Environment Preference of Young Consumers in Guangzhou, China.” Property Management 28 (3): 174–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02637471011051318.

- Yildirim, K., and O. Uzun. 2010. “The Effects of Space Quality of Dormitory Rooms on Functional and Perceptual Performance of Users: Zübeyde Hanım Sorority.” Gazi University Journal of Science 23 (4): 519–530.

- Yusuff, O. S. 2011. “Students Access to Housing: A Case of Lagos State University Students-Nigeria.” Journal of Sustainable Development 4 (2): 107. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v4n2p107.

- Zaransky, M. H. 2006. Profit by Investing in Student Housing: Cash in on the Campus Housing Shortage. Dearborn Trade Pub. Kaplan Business.