ABSTRACT

“Informal heritage” refers to spaces in cities that have certain heritage value but cannot be officially recognized as urban or architectural heritage sites. The author has observed the recognition and conservation of informal building heritage driven by architectural scholars (professionals) or communities in some Asian cities; this phenomenon provides a suitable perspective from which to observe the connection between Asian conservation, citizen participation, and urbanism. Western heritage research recently emphasizes the empowerment of communities to manage heritage conservation; however, what is the meaningful community participation in the old building’s conservation if adding the professional perspective, especially in the diversified Asian urban context, remains unclear. This study involved participatory observation, interviews, and the analysis of relevant literature for comparison of the recognition and conservation approaches of two typical “informal heritage” cases in Hong Kong (China) and Iwate Prefecture (Japan). This paper discusses the interaction modes among historians, related professionals, and communities and the “heritage process” in these two urban contexts. Additionally, an argument is made that these two cases are consistent with a Western heritage conservation theory, which encourages community empowerment; however, in the Asian urban context, a higher degree of community participation does not necessarily indicate more meaningful participation.

1. Introduction

For a building with historical value to be conserved, specific and strict recognition criteria must be met (such as the Law of the Peoples Republic of China on Protection of Cultural Relics in China and the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties in Japan). However, There are some spaces cannot be recognized as urban and architectural heritage sites by official authorities. Such spaces, as the sites of urban historical development, are closely linked to the transformation of local community life and have unique heritage value. American urban designers or urban history scholars Chase, Crawford, and Kalisk (Citation2008) called for special consideration of the abundant everyday life in cities as part of the place-making process. Japanese architectural scholar Hidenobu Jinnai (Citation1995) uncovered the meanings, structures, and layered histories behind the specific everyday spaces in the city of Tokyo after conducting a considerable number of anthropological field investigations. The aforementioned literature inspired us to adopt a dynamic perspective to consider how to approach old architecture that has not been incorporated into the official heritage recognition system. Our aim was to help cities display the anthropological characteristics of continuous development and transformation and then reduce the potential risk of the loss of urban historical traces. The phenomenon of the recognition and conservation of informal heritageFootnote1 has appeared in diverse Asian cities and in various urban contexts, and this phenomenon provides a favorable perspective from which to evaluate Asian urbanism.

The concept of “heritage” no longer simply refers to “a single monument” (Nikovic and Manić Citation2020, 107) but also to the conservation of specific areas with noteworthy historical significance (Steinberg Citation1996, 463). This concept is also widely linked to other topics such as sustainability and social transformation and especially the fields of urban renewal, design, and planning (Nikovic and Manić Citation2020, 108). Moreover, consistent with the general trend of the pursuit of cultural diversity after the Cold War (Xu Citation2019, 19), Nara 20 + (On heritage practices, cultural values, and the concept of authenticity) highlighted the role of community involvement in heritage conservation (Xu Citation2014). In the book Heritage, Conservation and Communities: Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building, heritage conservation is regarded from conservation of historical architecture to help preserve the places that are cherished by people and provide vital facilities to the community (for participating in the conservation process; Chitty Citation2017). Heritage conservation should be transformed from its current focus on technical matters into a social and political process (Mason and Avrami Citation2002, 25).

The job of accrediting and conserving heritage sites is highly professional. Thus, stakeholders must consider the complexity of community involvement and discuss how citizens can participate in the process in a meaningful manner with consideration of their professional shortcomings. Determining the ideal level of interaction between architectural professionals or scholarsFootnote2 and the local community for maximizing their professional advantages has been a core topic of heritage conservation research since 2000 (Chitty Citation2017, 2). Several Western scholars have advocated the community-centered mode of heritage conservation; however, in the Asian context, cities have recently shifted from the developmental to the post-developmental phase (Cho and Križnik Citation2017), and each city has a distinct social and urban context. Whether the experiences of Western countries in scholar–community interaction in heritage conservation is applicable in Asian contexts remains unclear; thus, theoretical support is urgently required. Few studies have considered the conservation of informal heritage from the perspective of community involvement in an East Asian context, and considerable uncertainty remains regarding the relations among the public, communities, relevant professionals, and heritage conservation in an East Asian urban context.

Several methods were used in this research: the author participated in a 3-day conservation activity of an abandoned school led by the Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo, and local architects in Iwate Prefecture (Japan) in 2018. The author conducted several interviews in Japan and Hong Kong (China) with scholars, professionals, project initiators, and managers of nongovernmental organization (NGOs) who were aware of or had participated in the cases, to investigate the urban background and the history of how informal heritage is integrated into urban discourse. This research also relied on the analysis of relevant literature because some research have referenced the Hong Kong case; however, few studies have linked these cases to the discussion of the unofficial recognition and conservation modes of informal architectural heritage. Through these methods, major urban topics were integrated into the discussion of two informal heritage recognition cases in Iwate Prefecture (Japan) and Hong Kong (China). These cases were compared using an integrated theoretical model combining a Western heritage scholar’s theory that assumes that intellectuals, the public, and interest groups in the heritage conservation area interact with each other (Poulios Citation2010), and Sherry Arnstein’s theory of the ladder of citizen participation (Citation1969). My research discovered that the two cases represent two modes of the relationship among heritage, scholars (or professionals), and the community. This paper argues that compared with lower levels of participation, a higher level of participation of local residents and the community does not necessarily indicate more meaningful participation in conservation in an Asian urban context and should face their own urban limitations. The potential roles of architectural professionals in the process are also discussed.

2. Literature review and case selection

2.1. Tendency toward urban heritage and living heritage

2.1.1. Heritage into the context of urban discourse

The Burra Charter (first adopted in 1979) in Australia marked several major advances in heritage conservation; for example, “place” was used rather than “building” and “monuments,” and cultural significance was valued in terms of the conservation and management of places (Truscott and Young Citation2000, 102). A considerable amount of research has recently discussed how the concept of heritage became linked with the environment of the site. Chakravarti (Citation2017, 984) traced the history of how the conservation of buildings has shifted to the protection of urban areas since the implementation in 1967 of the Civic Amenity Act in the United Kingdom, which states that urban areas “with unique historic value and architectural feature” should be conserved with their “collective value.” Steinberg (Citation1996, 466) argued that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Convention Concerning the Protection of the World’s Cultural and Natural Heritage (1977) was the first to introduce the concept of “cultural heritage,” which laid the foundation for the notion of conserving and rehabilitating areas. UNESCO (Citation2011, 3) also introduced urban areas into the historic landscape and extended the definition of historical sites to include the “broader urban context and its geographical settings.” Some researchers have called for the conservation of heritage sites to also consider the overall urban area instead of simply conserving a single building. Steinberg (Citation1996, 463) advocated “area rehabilitation and revitalization approaches” that could “maintain the typical urban tissue and essential qualities of the historic areas and of the life of the communities residing there” when conserving old inner city areas and historic monuments. Chakravarti (Citation2017, 986) discussed the relations between sustainability, conservation, and urban design to develop an integrated method related to urbanism; Chakravarti further argued that the community and the “comfort [of] its inhabitants” should be prioritized in the protection of cultural heritage. Nikovic and Manić (Citation2020, 107) discussed establishing a holistic platform for protection, planning, and the sustainable usage of cultural heritage sites with three main levels and called for “a wide range of participants” in the protection of such sites.

2.1.2. Living heritage and the scholar–community–heritage interaction model

Cultural heritage administration is undergoing some transformation; for example, (1) its focus has shifted from country interest to local interest, (2) its principal support has shifted from the upper middle class comprising a few elites to grassroot-level communities, and (3) the focus of stakeholders has shifted from the architectural and historical value of sites to their social and cultural value (Yung and Chan Citation2011, 458). The notion of heritage conservation is evolving from “historical conservation” based on “historical information authenticity” to the “cultural conservation” of regional multicultural sites conducted jointly by specific communities that consider tangible and intangible factors in the heritage site (Xu Citation2019, 12). Public participation has become an essential element of the heritage conservation process (Clark Citation2000).

The interactive relationship between heritage and community is closely connected to local society, politics, culture (Greer Citation2010), and geographical structure, all of which may exhibit considerable diversity (Watson and Waterton Citation2010, 2). Community participation, in the heritage conservation research field, includes the sharing of knowledge and familiarization with community life experienced through material culture (Apaydin Citation2018). Hou (Citation2008) introduced the social process and community design perspective into the definition of the heritage–community relationship, with an old house conservation program in Taiwan serving as an example; Hou attached more importance to the social process and mechanism of design and construction than on the design itself (79). He advocated for a participation-oriented and community-oriented process for spatial forms and physical structures. Chitty (Citation2017) further proposed the definition of heritage conservation for creative sustainable management and social integration practices (2). The aforementioned works introduced the social progressive perspective into the field of heritage conservation (Pendlebury, Townshend, and Gilroy Citation2004, 11).

Regarding the conservation of unique historic areas in cities and specific old buildings that cannot be recognized and conserved by the official heritage departments, the role of scholars/professionals and their relations with community remains unclear. Studies have examined the establishment of university–community teaching cooperation relationships (Wiewel and Lieber Citation1998; Dewar and Isaac Citation1998). Hou (Citation2007), by taking a community design teaching studio as an example, argued that the integration of the teaching process into the “community process” is the core concern of university–community teaching design in terms of the relationship between universities and communities. Similarly, the essence of the scholar–community–heritage relationship is the dynamic coordination process of the interactive relations of scholar participation, community processes, and heritage evolution.

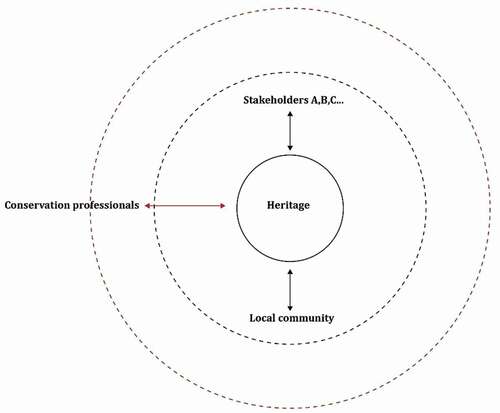

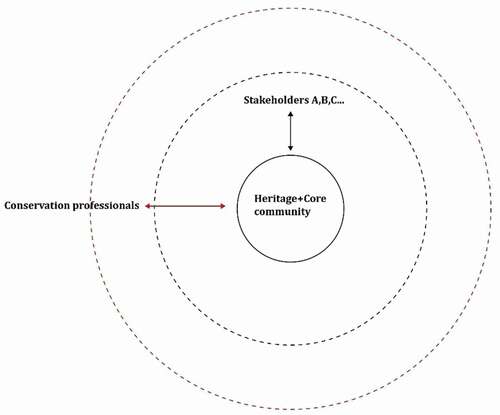

Although expert- and scholar-driven heritage conservation rather than community-driven conservation is the norm in the field (Chitty Citation2017, 3), Western scholars are calling for the incorporation of local opinions and voices into the management process of cultural heritage (Stenseke Citation2009) and for heritage conservation programs to focus on the management of creative continuity and socially cohesive heritage practices (Chitty Citation2017, 2). Ioannis Poulios, a Greek heritage scholar, reconsidered the authentic meaning of heritage because heritage discourse had long been dominated by scholars (Poulios Citation2010, 171). In a discussion of the sustainability of relations between scholars, the community, and heritage sites, Poulios proposed three modes for the interactive relations of experts, the public, and interest groups behind heritage conservation (Poulios Citation2014a, Citation2014b), namely material-based, value-based, and living heritage approaches (). The key differences between these three modes concern who dominates the heritage conservation, the extent of participation of the local community, and whether the conservation of heritage stresses tangible or intangible elements. For instance, the value-based method attaches importance to the equal communication of stakeholders’ values and views, but its coordination process still requires a powerful “managing authority,” and specialists and experts are preferred to assume the responsibility in the process (Poulios Citation2010, 173 and 174). The living heritage mode takes the local community as the heritage’s core responsible group, and heritage conservation is integrated into the community process. Poulios (Citation2010, 181) argued that this model should be adopted as the principal model to enhance the authenticity of heritage conservation. However, several research gaps remain. First, Poulios’s three analysis models aims at archeology; when heritage has been integrated with urban discourse, the community progresses beyond a territorial or local concept that sometimes forms during the heritage conservation process. Second, the relations between professionals (who can supply knowledge) and communities are always complex. Third, considering the diversity of community participation in old building’s management (Watson and Waterton Citation2010, 2), along with the unofficial redefinition modes of informal heritage in the Asian context, it is unclear whether the Western theory can still function and whether the local community (especially local residents and stakeholders) should be empowered to have total control. This paper further integrates the theoretical framework of the ladder of citizen participation (Arnstein Citation1969) and Poulios’s three analysis models as a lens through which to explore the expert community () interaction process underlying informal heritage cases in Hong Kong (China) and Japan. Some pertinent questions remain to be answered. (1) How is the urban community formed during the informal heritage recognition and conservation process? (2) Does a higher level of community participation lead to more effective informal heritage conservation? How can communities meaningfully participate in informal heritage conservation? (3) How do the interaction models of community and professionals work in the informal heritage conservation in Asian urbanism? (4) How do informal heritage recognition and official heritage recognition interact?

Figure 1. Diagram of the multilevel universal model of the interactive relationship underlying heritage conservation of the value-based approach (the inner circle denotes the territory of living, the middle circle indicates the territory of using, and the outside circle denotes the territory of protecting).

Figure 2. Diagram of the multilevel universal model of the interactive relationship underlying heritage conservation of the living heritage approach (the inner circle denotes the territory of living, the middle circle indicates the territory of using, and the outside circle denotes the territory of protecting).

Figure 3. Integrated model of expert–community interaction in heritage conservation (Poulios Citation2014a, Citation2014b) and the ladder of citizen participation theory (Arnstein Citation1969).

2.2. Asian heritage in diverse urban conditions and case selection

The urban context of heritage conservation is closely linked to social and economic development. Japan has established an official heritage recognition and conservation system, but the declining birthrate since 2006 and the shrinking city model have presented new challenges for the preservation of abandoned buildings and sites. Hong Kong’s postcolonial period started after its return to China in 1997, and the word “bou juk” (in Chinese:保育) was first used circa 2005 with reference to heritage in the city’s official documents (Hui Citation2019, 124). Community-driven informal heritage events were held in the same year, symbolizing the change in the city’s relationship between heritage conservation and community involvement. Since then, heritage has become a popular topic, especially in terms of how stakeholders view their history, and has received widespread attention in society. This process has led to a wealth of case studies on how citizens can participate in the sustainable urban renewal of a city. In the present study, one typical case was selected from Japan and Hong Kong (China) respectively to discuss the interaction modes underlying informal heritage conservation. Takkotai Elementary School (in Ichinoseki, Iwate Prefecture, Japan) is a typical professional- and scholar-driven heritage recognition project of an abandoned building (interview with a local architect). In Hong Kong, Wedding Card Street is the first influential informal heritage recognition project led by citizen groups (interview with a Hong Kong urban planner). The project in Hong Kong marks the start of bottom-up heritage conservation efforts, and it is an example of stakeholders meeting the challenges of rapid urban renewal.

3. Case study: Takkotai Elementary School in Iwate Prefecture and Wedding Card Street in Hong Kong

3.1. The case in Iwate Prefecture (Japan)

3.1.1. The heritage conservation recognition system of Japan and the recent decline in birthrate

Laurajane Smith, an Australian expert of heritage and museology, regarded heritage as a policy, legal framework, and value concept (Smith Citation2006) based on Western Authorized Heritage Discourse. This discourse is spread by international intergovernmental agencies such as UNESCO for managing and conserving heritage (or cultural resources), and it considers heritage from a Eurocentric perspective (Winter Citation2014, 132). Because of the considerable impact of Western culture in Japan after the Meiji restoration, Japan took the lead in modernization in Asia. In the 1870s, the concept of Western historical monuments reached Japan (Choay Citation2001). Japan promulgated the Edict for the Preservation of Cultural Relics in 1871 and the Law for the Preservation of Ancient Shrines and Temples in 1897; and revised the Act on Protection of Cultural Properties in 1975 (Zhou Citation2017, 13 and 14). In this manner, Japan pioneered the establishment of a comprehensive heritage conservation system in Asia.

In contrast to Hong Kong (China), with its rapid urban renewal and intense commercialization, in Japan, the birthrate began to decline and the country entered a particular urban development mode in 2006 (Okata and Murayama Citation2011). In times of population decline, the normal shrinking pattern of a compact city is shrinking beginning at the cities periphery and moving toward the center. However, the research results of Aiba (Citation2005, Citation2018) indicated that buildings and areas become idle and free and are scattered between the city and suburbs because the land is owned by individuals; this is referred to as the porous mode (of idle land) in times of population decline. Aiba (Citation2018, 34) highlighted the challenge of substantial and wide-ranging transformation in cities caused by a lack of consensus and argued that a central topic in Japanese urban and informal heritage conservation in this era is how to conserve/activate abandoned houses with small changes in the city and integrate community empowerment into the process. Moreover, since the great earthquake in 2011, Japanese architects have become more conscious of their social and public responsibility instead of simply serving the private interests of their clients (Arch+Aid Citation2016; Okabe Citation2018). However, the revitalization of small areas, reutilization of old buildings in communities, and role of professionals and scholars in this type of informal heritage outside the formal heritage conservation system pose new challenges to heritage conservation.

3.1.2. Value-based approach: “Nakanaka Heritage” (なかなか) recognition committee and Takkotai Elementary School

Similar to the citizen-driven discussion on the heritage of Hong Kong, cases of historical street conservation by social organizations in Japan were observed as early as the 1960s. Initially, a citizen organization called Machinami Conservation and Regeneration started to convene the Zenkoku Machinami Semi meeting starting in 1978 (held annually thereafter) with the aim of promoting participation in urban conservation across Japan (Kinoshita Citation2018, 1089). In these meetings, nonprofessional and unofficial nongovernmental organizations played critical roles. And, cases of heritage conservation led by architecture scholars in Japan have been noted since 2007; examples include the heritage conservation of the Nakagin Capsule Tower (Lin Citation2010), Miyakonojo Civic Center, and old traditional houses in the historical post town of Tokaido, Kambara in Shizuoka city (Kinoshita Citation2018). In this paper, explanations are provided with the Nakanaka Heritage Recognition Committee serving as an example. The committee is led by professors at the Institute of Industrial Science of The University of Tokyo, and it seeks to identify old buildings that are not recognized as national cultural sites or world heritage sites but have spirit-shared value; represent important historical events, memories, landscapes, natural environments, and social processes; or bring various benefits to people throughout the world (Non-profit Organization Nakanaka Heritage Committee Citation2020). Heritage site revitalization activities have also been conducted since the establishment of the committee.

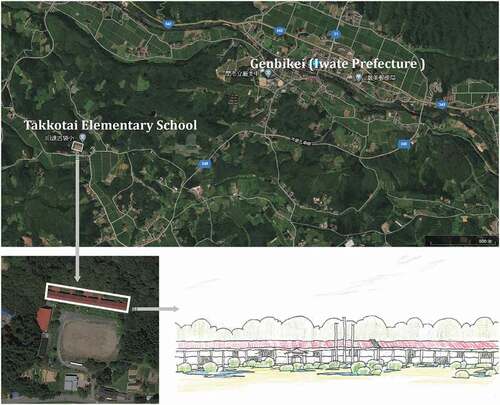

Takkotai Elementary School (in Ichinoseki, Iwate Prefecture), an abandoned elementary school (), is an example of a heritage site without official recognition. The one-story wooden building housing the school was constructed in 1951; however, because of the rapid growth of the local population, the building was designed to have an elongated shape and lengthened to 119 m. Therefore, the building is a powerful reflection of the local history at that time. However, in 2013, because of the declining birth rate, the school was abandoned. Responding to an invitation from local architects, professors at the Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo, visited the school to perform an earthquake assessment in 2010; these professors were intrigued by the building’s particular architectural forms. The situation of the site was rather complex because the land was owned by the local agricultural association, but the building was owned by the government. For any action to be taken, the government was first required to solicit and summarize the opinions of local citizens. However, the government and the public were not particularly active in such conservation projects (interview with a local architect), and the government’s budget was extremely limited. The government’s intention was to retain half of the building for renewal and demolish the other half to construct a public auditorium. If one half of the building was demolished, then the historical significance of the abandoned school would be lost (interview with a local architect). To address this problem, scholars at the University of Tokyo and local architects established a nonprofit organization (NPO) for conserving the building (一関のなかなか遺産を考える会 in Japanese). The NPO negotiated with the public and the government, and their final decision was to conserve the other half of the building temporarily. With the help of the agricultural association and by coordinating with the local government, the new NPO attracted people who were interested in the project (these people participated in relevant activities after receiving information or hearing about the project from friends; mainly people from Ichinoseki participated). The NPO used the unique elongated layout of the school building and regularly convened races that involved wiping the ground with a rag (). By promoting such activities that integrated traditional folkways and sports elements, the NPO attracted people of all ages (e.g., older, middle-aged, and young people, including undergraduates, teenagers, and children) to participate in the conservation activity (Interview with local architect, 2018; ). According to the observation of the current author, architectural professionals and those with relevant specialties within governmental departments were also attracted and participated in the conservation project and activities. In August 2014, the site of Takkotai Elementary School, because of its historical and landscape value, was officially recognized as the “No. 1 Heritage” site by Nakanaka Heritage International Recognition Committee.

Figure 6. Social dialogue mode behind the informal heritage approach for Takkotai Elementary School in Iwate Prefecture (Japan).

The movement to conserve Takkotai Elementary School is a typical example of architectural historians exploring the value of old architecture and recognizing architectural heritage along with the conservation community. More old architecture with specific heritage value that failed to be recognized in the official heritage system has since been identified. The Japanese government recently announced plans to demolish the Miyakonojo Civic Center, a building designed by Kiyonori Kikutake, who represented the “metabolist movement.” In response, Japanese building experts led and united the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), Docomomo International, Architectural Institute of Japan as well as external people and citizens against the demolition and launched relevant conservation campaigns. In contrast to the results obtained for Takkotai Elementary School, these efforts did not prevent the demolition of the Miyakonojo Civic Center. Nevertheless, these scholars did make a substantial contribution by mobilizing various relevant parties, especially local residents, to conserve a unique heritage site.

3.2. The case in Hong Kong (China)

3.2.1. Informal redefinition of heritage discourse in Hong Kong

3.2.1.1. History of the official heritage definition in Hong Kong before 2000: transplantation of Western Authorized Heritage Discourse to the Far East

Since World War II, cities in Asia have been built under various forces, such as colonization, decolonization, urbanization, modernization, industrialization, and deindustrialization; moreover, these cities have engaged in a dynamic dialogue with the Western Authorized Heritage Discourse, as argued in a speech made by a professor the National University of Singapore (Muramatsu Lab Citation2017, 17). Because of the difficulty of keeping pace with the specific transformation and complex conditions of these regions, the direct transplantation of heritage recognition standards under the international and universal discourse of international heritage organizations have to some extent caused a deintercalation from the local understanding. The re-understanding and re-definition of “heritage” under such circumstances has become a major topic in urban planning and urban renewal conservation.

Hong Kong is a commercial society that has a limited amount of developable land (Lung Citation2012, 132) and attaches great importance to the development of the economy. In 1976, the Hong Kong Administration promulgated the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (hereafter referred to as “the Ordinance”) to ensure the appropriate conservation and preservation of the most valuable cultural relics. Since then, cultural conservation has received considerable attention. Following the establishment of the Antiquities Advisory Board and the Antiquities and Monuments Office in the same year, the administrative system for antiques and historical sites (monuments) was formed. However, the Antiquities and Monuments Office did not have sufficient authority to conserve heritage sites with historical value (Lu Citation2009) at that time; heritage sites were recognized under the guidance of experts in archeology and museology, and the responsible employees were mainly those with an academic background in history, geography, or anthropology (Barber Citation2014, 1186). Moreover, the Ordinance was criticized for its monument- and memorial-oriented definition of heritage (Cody Citation2002). The focus of the Antiquities and Monuments Office was on preserving sites for education and tourism without reducing the redevelopment potential of land in the urban center. Its approach could be regarded as the “transplantation” of the British official machine and Western Authorized Heritage Discourse to Hong Kong (Barber Citation2014, 1186); the Antiquities and Monuments Office served the British Hong Kong Government in its local colonial rule.

3.2.1.2. Discourse shift to informal heritage: seeking urban identity and the redefinition of everyday urbanism in Hong Kong since 2000

After the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997, Hong Kong has begun attaching bigger importance to the living experiences of its urban history and physical buildings, as evidenced by a series of recent civic heritage conservation events; moreover, numerous communities and architectural scholars have participated in reflections on spatial heritage value (interview with a project initiator in a local NGO). These nongovernmental heritage definition events have started highlighting the shortcomings of official heritage recognition in terms of the local urban identity, previous experiences of everyday life, and the collective memory of Hong Kong in a time of rapid urban renewal. The official heritage recognition system was clearly inconsistent with the nongovernmental understanding of “old buildings” (Zhai and Chan Citation2015, 56). The heritage conservation recognition and governance system has been slow to adapt to the demands of contemporary society (Chan and Lee Citation2017). Thus, a gap formed between the official definition of “heritage” and the understanding of the public regarding architectural history. This process reflected the complexity of the meaning of “heritage” beyond its architectural professional aesthetics. The Hong Kong Antiquities Advisory Board established the criterion that buildings must have at least 50 years of history to be considered historical buildings and listed this as a consistent standard for evaluating cultural relics (Lung Citation2012, 134). Many buildings, including the case of Wedding Card Street discussed herein, have lost the opportunity to be recognized by the official heritage system.

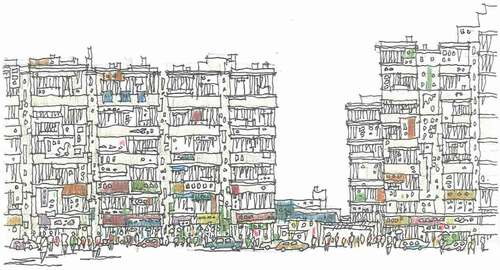

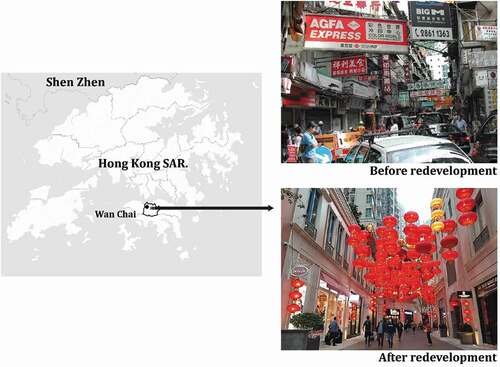

3.2.2. Living heritage approach: civic conservation case of Wanchai, Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s urban planning and real estate redevelopment tended to favor hegemonic economic re-developmentalism (Tang Citation2017) after the Asian financial crisis (Zhou and Zhu Citation2014). This approach arose from the intensive urban renewal speed, government intervention, and destruction and reconstruction of old architecture in the urban center. In redevelopment projects, the Urban Renewal Authority (URA) purchases “dilapidated buildings from the property owners” and pays the building occupants to vacate their properties, but these people struggle to buy a new apartment locally with the money that they are offered; moreover, after property developers construct new buildings, they sell them for profit (Lu Citation2016, 326). Since 2004, a series of old street conservation events in central Hong Kong, such as Wedding Card Street, the Blue House, and Wing Lee Street, have prompted local civil society to improve its conservation awareness and continually scrutinize the existing official heritage recognition system and conservation methods. The Wedding Card Street () community in Wanchai on Hong Kong Island is an example of local informal heritage conservation and was described as a pioneer case by numerous stakeholders who care about heritage and urban public space in the author’s interviews. Except for a few high-rise buildings, the remaining buildings here were the Tong Laus (in Chinese:唐楼) built in the 1950s to 1960s (). These buildings had interconnected rooftops, with the external half used for reception, sales, and exhibition and the internal half used as the factory for printing. The whole street formed a self-contained economic network, using the printing and the wedding card as the central theme, with strong community relations. The street was not recognized as an official heritage site, but it was strongly symbolic of the particular history of Hong Kong (Siu Citation2008, 60). The street was regarded by local people as the basis for “[a] close interpersonal relationship network” and “[a] mutually supportive neighborhood [that] developed from [a] low-capital economy” as well as the basis of “Wan Chai people’s identity” (Lu Citation2007, 136).

Figure 7. The location and photos of Wedding Card Street before and after the redevelopment.

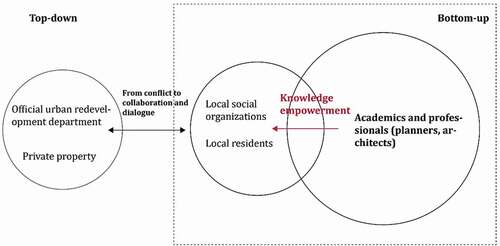

In October 2003, the URA released the H15 plan to redevelop the whole street. With the help of St. James’ Settlement, a local organization with a long history of serving the Wanchai neighborhood, and the Second Wanchai District Council, local residents (including the shop owners, residents, landlords, and tenants) established the H15 concern group and submitted the first nongovernmental urban planning scheme in Hong Kong (Siu Citation2008, 59), namely the “Dumbbell Scheme,” with the help of professionals. The citizen group consulted architects, planners, surveyors, and other professionals (Huang Citation2009, 13) as well as examining other rebuilding projects (Xia and Chan Citation2014), such as Singapore Woodlands Waterfront Park, Guangzhou Shangxiajiu Pedestrian Street, and Shanghai Suzhou River, and dedicated themselves to achieving professional excellence in all aspects of building and planning laws, and land policy through self-study. The “Dumbbell Scheme” balanced the new dwelling buildings with “the need[s] of [the] local community to return to their original district” to preserve the social network and the community (Lu Citation2016, 332). Anthropologist Xia (Citation2017) pointed out that local organizations and communities, in the process, became the leading driving force from top to bottom; professionals also participated in local empowerment initiatives by providing professional knowledge support to local citizen groups. illustrates the interaction mode led by the community behind the Wedding Card Street project. In November 2005, the URA forced the withdrawal of all property rights. In 2008, the Town Planning Board denied the “Dumbbell Scheme” because Wedding Card Street was an informal heritage site, and the application’s not being able to collect environmental impact assessment and traffic impact assessment as required (Huang Citation2009, 13), and all buildings were demolished. The original intention of the Wedding Card Street project was to fight for the right of free choice of resettlement and housing rights in the urban renewal process; however, the whole process also changed citizens’ conception of architectural heritage and their attitude toward urban renewal.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of informal heritage recognition criteria and their interactive relations with official recognition systems

Distinct recognition systems are employed in various cities according to the specific social context and social system (). Hong Kong (China) is a legal society, and its government is relatively responsive to the desires of its citizens. The case of Wedding Card Street illustrates how the interaction between citizens and the government shifted from conflict to collaborative dialogue (Xia and Chan Citation2014); a series of heritage events at the social level progressively boosted the integration of heritage and urban renewal discourse. The frequency of occurrence of such citizen events peaked circa 2008 and prompted the government to rethink the limitations of Western Authorized Heritage Discourse in their former official heritage definition guidelines. In 2008, the Hong Kong government launched the Urban Renewal Strategy Review (Development Bureau Citation2011), established the Commission for Heritage Office under the Development Bureau (Lung Citation2012, 124), started the Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme (Development Bureau Citation2008), and established the Urban Renewal Fund. The aforementioned initiatives symbolized that the Hong Kong government was willing to progressively incorporate the community into the recognition and conservation of spatial heritage. Local governmental departments were still criticized for their approach to urban renewal; however, they continued to seek balance between urban renewal and heritage conservation with their statutory bodies and civil society and adjust their modes of negotiation and collaboration.

Table 1. Comparison of unofficial heritage recognition criteria, the definition generation process, and their interactions with official recognition criteria in Hong Kong (China) and Japan

In the cases of the school in Ichinoseki (Iwate Prefecture) and Miyakonojo Civic Center, which were explored with the “butterfly model” (Muramatsu Citation2009), architectural scholars and the public had different understandings of the concept of heritage. In Hong Kong, top-down governmental institutional transformation was prompted through discussion. By contrast, the Nakanaka Heritage Recognition Committee, by establishing an NPO and by engaging in network-based cooperation with local architects, attached more importance to the conservation of a specific case; this NPO also prioritized the exploration of the architectural value of old buildings and the improvement of awareness of the local community regarding architectural history, especially for heritage sites.

4.2. Comparison of participation modes

In the informal heritage cases in both regions, the different modes and approaches correspond to the different levels (hierarchies) of public participation (; ). The heritage–community relationship in both cases formed during the conservation process, and the geographical territories of its participants exceeded the boundary of the local place (Waterton and Smith Citation2010, 9). However, the heritage sites in the two sites faced distinct urban renewal conditions and social atmospheres.

Figure 10. Using the integrated model to evaluate the scholar–community interaction relationship underlying the cases in Hong Kong (China) and Iwatw Prefecture (Japan).

Table 2. Comparison of Wedding Card Street in Wanchai, Hong Kong, China and the abandoned Takkotai Elementary School in Iwate Prefecture, Japan

In Japan, the “sponge” urban renewal mode prevents many old buildings from becoming part of large-scale urban renewal planning (Aiba Citation2005). In the Japanese context, the government’s emphasis on renewal under the entire social atmosphere is not as strong as that in commerce-led communities such as Hong Kong (China). In the Japanese case discussed, real estate developers were not involved (in contrast to the case in Hong Kong) and stakeholders had little resistance to conservation; these factors contributed to the successful conservation of many old buildings with the help of scholars, but the Miyakonojo Civic Center was still demolished.

In the value-based approach mode employed in the case of Iwate Prefecture, local architects and Tokyo-based architectural historians were actively involved in the government’s heritage decision in arousing the heritage awareness of citizens. In this manner, these architects and historians (especially those from the University of Tokyo) used their high status and influence in Japanese society. For example, initiated by architectural scholars, the Japan Docomomo Committee, and the Urban Heritage Department of the University of Tokyo established a comprehensive nongovernmental research and recognition network. The heritage list provided by Docomomo Japan Branch and led by a professor at Tokyo University of Science is highly respected by official heritage departments in Japan (Muramatsu Lab Citation2017), and it is one of the key parts of the important historical building directory of Japan. Japan also attaches great importance to university education and cultivates a top-class intellectual elite class (Zhang Citation2014), including architectural historians; therefore, the leadership of scholars and professionals results in positive responses from multiple parties. In the Japanese case, the professional scholars have both “top-down” and “bottom-up” characteristics: they do not represent the authorities and are unable to reverse the government’s decision to demolish a building, but their extensive influence can be used to promote or even completely lead the process of heritage conservation at the local community level.

Takkotai Elementary School (wooden building, with spatial style characteristics, that symbolizes local history and has landscape value) and the Miyakonojo Civic Center (emblematic of the metabolist architectural movement) were old buildings that had long been abandoned but that professionals perceived as having high architectural heritage value. Failure to incorporate the importance of architecture and heritage into the everyday lives of citizens may explain why local residents and citizens had limited enthusiasm for heritage conservation. Moreover, according to butterfly theory (Muramatsu Citation2009), an inconsistency exists in the understanding of heritage value among scholars and the public; citizens have their own understanding of the value of old buildings. The awareness of citizens regarding architectural heritage can be improved and the lack of architectural continuity between the past and present can be remedied through a series of creative activities involving everyday planting and cooking classroom programs driven by scholars and professionals; such programs also increase the intangible value of the old buildings. However, when the material-based approach evolves into the value-based approach, community participation is still under the management and supervision of professionals and scholars (Poulios Citation2010, 174). Because of the appearance of numerous scholar- or professional-driven cases of abandoned site conservation, two matters should be prioritized by scholars and professionals: (1) whether the community building method can be employed in these contexts and (2) how to more effectively link community demands and architectural value to enhance the authenticity of architectural value and integrate it into community processes.

In the Hong Kong informal heritage case, old buildings can be understood as the contradiction between localization and commercialization- and tourism-oriented invasion caused by globalization. The conservation process for these areas highlights the limitations of Western Authoritative Heritage Discourse in the localization process in Hong Kong in the context of a globalizing economy and tourism-oriented changes. The process also emphasizes the struggle between rapid “property-led renewal” (Ng Citation2002) and the increasing desire of Hong Kong’s civil society to preserve urban sites that embody local memories. Citizens’ spontaneous conservation of Wedding Card Street, the Blue House, and Wing Lee Street occurred within the large-scale urban renewal planning scheme of Hong Kong (Wanchai, Central), where heritage and community interests were linked to the personal demands of citizens (such as in terms of housing and cultural conservation).

The entire process was led by citizens; the community was concerned not only with the conservation of tangible buildings or the architectural values of the spaces (compared with the Japanese case) but also conservation of the intangible “close interpersonal relationship network” and “mutually supportive neighborhood [that] developed from [the] low-capital economy” as well as the search for the “Wan Chai people’s identity” (Lu Citation2007, 136). Old buildings are not merely monuments “in the past” but also an integral part of everyday life and can be passed on to later generations. The Hong Kong’s informal heritage conservation process is consistent with the living heritage approach (Poulios Citation2014a, 139). Residents endeavored to conserve spaces that were in use and inhabited by citizens but that also represented everyday life’s memory in the past, as well as the community life and low-capital economic networks. In the spontaneous heritage conservation projects for Wedding Card Street and the Blue House, citizens interacted with local officials, and learnt from and cooperated with architectural scholars and professionals who provided relevant urban and architectural knowledge on their first civic-driven urban planning scheme. During this process, professionals were also provided the opportunity to explore the definition of heritage in a real-life context and citizen participation mode in heritage conservation in the local neighborhood rather than through books influenced by Western Authoritative Heritage Discourse.

Wedding Card Street was demolished for urban renewal, but the principles established during that process were applied to the later conservation of the Blue House. These principles are as follows: (1) simultaneous conservation of tangible cultural heritage and intangible cultural heritage, (2) a bottom-up participatory local co-governance strategy, (3) fostering of local community identity, (4) community economic participation and empowerment, and (5) integration of conservation into local education (St James Settlements Citation2007, 5 and 6, interview with a project manager who participated in the Blue House project). The success of the Blue House was inseparable from the cooperation of architects and scholars.Footnote3 Through the implementation of these principals, a complete community conservation system, with architectural heritage at its core, was established; additionally, the community and heritage were integrated organically and sustainably, and architecture became an authentic and integral part of the place’s social continuation process instead of simply existing in the past (Poulios Citation2010, 176, Citation2014a). These projects increasingly blurred the boundary between official heritage and unofficial heritage, monumental-type heritage and everyday heritage, and colonial heritage and Hong Kong citizens’ identity heritage. A strategy that integrates informal heritage with the authenticity of heritage represents a different approach to urban renewal.

Because of the intertwined participation of government departments, community networks, and scholars and professionals, heritage conservation has also been extended to discussions on other subjects, such as urban-space creation, and an architect who had served in the Blue House project even create a research platform to explore how to include citizen participation in the creation of urban public spaces (interview with a project manager of a Hong Kong NGO). This has prompted the public to recognize the value of heritage, redefined heritage, boosted the capacity building of communities, and increased the genuine participation of communities (Chitty Citation2017, 3) in heritage conservation. Therefore, future research should consider how a similar living heritage approach can be employed in the conservation of other informal heritage sites and normalized through incorporation into the existing urban planning and design system.

As per the findings from the above discussion, the communities in Japanese and Hong Kong (China) cases are both formed during the recognition and conservation processes of the informal heritage. A reasonable assumption would be to say that the attitude of various stakeholders towards informal heritage is closely linked to their urban contexts. Moreover, the community-scholar/professional interactive modes in informal heritage conservation are influenced by their specific urban environment. Community participation is meeting various pros and cons on citizen awareness and professional degrees in different cities. The “living heritage” and local community-central mode advocated by Western heritage scholars may not be directly applied to the practice of the Asian informal heritage’s recognition and conservation. The degree of local community participation should not be blindly increased to recognize and manage their heritage sites. For the heritage practitioners and scholars/professionals in various urban environment, a detailed and comprehensive analysis could be conducted before their interactions with the local community mutually aiming at the recognition and conservation of informal heritage.

5. Conclusion

Community-driven conservation and local empowerment have gradually become the core topic of putting people in the center for debate in the global heritage field (ICOMOS Citation2014, 2). With this tendency, Western heritage scholars such as Poulios (Citation2010) have praised the living heritage approach because it effectively addresses the complex reality that heritage belongs to the past, but people live in the present. The elite cultural heritage of the mainstream in terms of cultural value or the heritage recognized by the government cannot represent all heritage; thus, every community should be encouraged to recognize its respective heritage (Huo Citation2016). In addition to actively participating in the heritage conservation program, architectural professionals should combine the advantages of their specialty with community demands at a deeper level; in this manner, abandoned old buildings in cities can be integrated into the process of social and community development, thereby enhancing conservation.

This paper deviates from the Western heritage perspective to focus on the recent informal heritage phenomenon in East Asian cities. In the informal heritage process, the relations between old buildings, the public, scholars, and communities help clarify the linkage between society, conservation, civil participation, and urbanism in Asia. This study considered two cases, one in Iwate Prefecture (Japan) and one in Hong Kong (China), which revealed major urban topics in the two regions. These two cases were discovered to correspond to Poulios’s modes of scholar–community interaction in informal heritage conservation (value-based and living heritage approach). The Hong Kong case illustrates an approach in which the organic conservation of old buildings is possible because of residents’ concerns for old residential buildings and street space. By contrast, the Iwate Prefecture case highlights that local residents and citizens did not have sufficient awareness of old buildings. In that context, the endeavors of Japanese professionals and scholars provided a strong guidance for citizens to participate in the recognition and conservation of informal heritage. This notion is consistent with that described by Chitty (Citation2017): “conservation in practice […] is about developing skills in groups and people management, generating honesty and trust in working together to create equity in new partnership” (9). Stakeholders encounter diverse urban contexts when attempting to recognize and conserve heritage sites. Thus, this paper reconsiders the definition of meaningful participation by the local community and professionals (or scholars) by employing the concept of the ladder of citizen participation and argues that Hong Kong’s living heritage mode is not necessarily superior to the value-based approach employed in Iwate Prefecture. Because of the distinct urban limitations that informal heritage cases face, each project must select an appropriate scholar–community interaction path according to the specific social context in the city where the building is located instead of directly misappropriating Poulios’s theory.

The current examination of sites in Hong Kong (China) and Japan also opens up new research directions. Informal heritage campaigns led by the public or scholars employ unique strategies that may further influence urbanism. Faced with rapid urban renewal, members of civil society (e.g., community organizations, professionals and scholars) in Hong Kong, in addition to striving for compensation, are gradually shifting their attention to the life network and life memory contained in the spatial heritage surrounding old buildings and a new urban commons (Sham Citation2017). In Japan, the Miyakonojo Civic Center was finally demolished. However, the campaign opened up the possibility of the “subsequent protection” of similar heritage spaces, promoted the future conservation of heritage sites, cultivated a desire to preserve architectural heritage among the public, and thereby minimized differences in the understanding of building heritage between professionals and the public (speech by a professor of the University of Tokyo in Hong Kong in October 2019). Further research may address the influence of informal heritage recognition and conservation on Asian urbanism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fei Chen

Fei Chen is a Ph.D. candidate at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He was a visiting associate research fellow at the Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo, and an academic visitor at the University of Oxford. He obtained his master’s degree in architectural design from the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL with a distinction certificate. He has also ever been a peer reviewer of the SSCI journal Landscape and Urban Planning.

Notes

1 The concept of “informal heritage” originated from the concern of the Nakanaka Heritage Committee, led by scholars of the Institute of Industrial Science of The University of Tokyo, that old buildings with heritage value were not regarded as official heritage buildings (Muramatsu and Koshihara Citation2013).

2 Architectural scholars of Japanese National Universities (e.g., The University of Tokyo) are paid by the state (Zhang Citation2014); however, their opinions do not represent those of official heritage conservation departments. In the heritage conservation research framework of Poulios (Citation2014b), experts and scholars are classified as top-down forces. In Japanese cases of informal heritage conservation, architectural historians have played a dual top-down and bottom-up role, which is described in this paper.

References

- Aiba, S. 2005. Toshi Wo Tatamu (Folding Up the City). Tokyo: Kadensha. in Japanese.

- Aiba, S. 2018. “Japanese Community Design in the Age of Population Decrease.” In Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the Pacific Rim Community Design Network, 31–38. Singapore: National University of Singapore.

- Apaydin, V. 2018. “Critical Community Engagement in Heritage Studies.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by C. Smith, 2791–2797. Cham: Springer.

- Arch+Aid. 2016. 『アーキエイド 5 年間の記録:東日本大震災と建築家のボランタリーな復興活動Arch+Aid Record Book 2011–2015 Architects’ Pro Bono Outreach Following 3.11』フリックスタジオ. アーキエイド, 一般社団法人.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 85 (1): 24–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2018.1559388.

- Barber, L. 2014. “(Re)making Heritage Policy in Hong Kong.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 51 (6): 1179–1195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013495576.

- Chakravarti, D. 2017. “New Hope to Urbanism: Congruence of Architectural Conservation, Urban Design and Sustainability.” International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) 6 (7): 983–986. https://www.ijsr.net/search_index_results_paperid.php?id=ART20175281

- Chan, Y., and V. Lee. 2017. “Postcolonial Cultural Governance: A Study of Heritage Management in Post-1997 Hong Kong.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (3): 275–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1269238.

- Chase, J., M. Crawford, and J. Kalisk. 2008. Everyday Urbanism. Expanded ed. New York: Monacelli Press.

- Chitty, G., ed. 2017. Heritage, Conservation and Communities: Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

- Cho, I., and B. Križnik. 2017. Community-Based Urban Development: Evolving Urban Paradigms in Singapore and Seoul. Singapore: Springe.

- Choay, F. 2001. The Invention of the Historic Monument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Clark, K. 2000. “From Regulation to Participation: Cultural Heritage, Sustainable Development and Citizenship.” In Forward Planning: The Functions of Cultural Heritage in a Changing Europe, edited by Council of Europe, 103-112.

- Cody, J. W. 2002. “Heritage as Hologram: Hong Kong after a Change in Sovereignty, 1997–2001.” In The Disappearing‘Asian’City: Protecting Asia’s Urban Heritage in a Globalizing World, edited by W. S. Logan, 186-207. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Development Bureau. 2008. “Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme.” https://www.heritage.gov.hk/en/rhbtp/about.htm

- Development Bureau. 2011. “The New Urban Renewal Strategy.” https://www.ursreview.gov.hk/eng/home.html

- Dewar, M. E., and C. B. Isaac. 1998. “Learning from Difference: The Potentially Transforming Experience of Community-University Collaboration.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 17 (4): 334–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9801700408.

- Greer, S. 2010. “Heritage and Empowerment: Community‐based Indigenous Cultural Heritage in Northern Australia.” International Journal of Heritage Studies: IJHS 16 (1–2): 45–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441754.

- Hou, J. 2007. “Community Processes: The Catalytic Agency of Service Learning Studio.” In Design Studio Pedagogy: Horizons for the Future, edited by A. Salama and N. Wilkinson, 285-294. Gateshead: Urban International Press.

- Hou, J. 2008. “Traditions, Transformation, and Community Design: The Making of Two Ta’u Houses.” In Expanding Architecture: Design as Activism, edited by B. Bryan and K. Wakeford, 74–83. New York: Metropolis Books.

- Huang, S. M. 2009. “A Sustainable City Renewed by “People”-Centered Approach? Resistance and Identity in Lee Tung Street Renewal Project in Hong Kong.” In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Graduate Student Conference, 1–28. Vancouver: UBC.

- Hui, C. M. 2019. “Ontological Politics: The Discursive Construction of Built Heritage Conservation in Hong Kong.” PhD Diss., Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Huo, X. 2016. “Understanding the Conservation of Cultural Conservation from the View of Community [从社区角度认识文化遗产的保护].” Design Community(住区) 3: 22–25.

- ICOMOS. 2014. “The Florence Declaration on Heritage and Landscape as Human Values regarding the Values of Cultural Heritage in Building a Peaceful and Democratic Society.” In ICOMOS General Assembly 2014, Florence.

- Jinnai, H. 1995. Tokyo, a Spatial Anthropology. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kinoshita, I. 2018. “The Spatial-Consciousness Dialectic for Heritage Conservation - From the Personal Experience Becoming the Owner of the 160 Years Old House.” In Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the Pacific Rim Community Design Network, edited by Pacific Rim Network. Singapore: National University of Singapore.

- Lin, Z. 2010. Kenzo Tange and the Metabolist Movement: Urban Utopias of Modern Japan. London: Routledge.

- Lu, T. L. 2007. “No Longer in the Pockets of Elites-the Inspiration of the Wedding Card Street Movement on the Concept of Cultural Conservation [不再在精英的口袋里——利东街运动对文物保育概念的启示].” In See Our Wedding Card Street [黃幡翻飛處: 看我們的利東街], edited by 周綺薇, 133-137. Hong Kong: V-artist.

- Lu, T. L. 2009. “Heritage Conservation in Post-colonial Hong Kong.” International Journal of Heritage Studies: Heritage and the Environment 15 (2–3): 258–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250902890969.

- Lu, T. L. 2016. “Empowerment, Transformation and the Construction of ‘Urban Heritage’ in Post-colonial Hong Kong.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (4): 325–335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1144635.

- Lung, P. Y. 2012. “Built Heritage in Transition: A Critique on Hong Kong’s Conservation Movement and the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance.” Hong Kong Law Journal, Spring Edition 42: 121–141.

- Mason, R., and E. Avrami. 2002. “Heritage Values and Challenges of Conservation Planning.” In Management Planning for Archaeological Sites: An International Workshop Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and Loyola Marymount University, May 2000, edited by J. M. Teutonico and G. Palumbo, 13–26. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Muramatsu, S. 2009. “Why and How We Should Inherit Urban Environmental Cultural Resources: Identifying, Listing, Evaluating, and Making Good Use of Urban Environmental Cultural Resources in Asia.” In Stock Management for Sustainable Urban Regeneration. cSUR-UT Series: Library for Sustainable Urban Regeneration. 4 vols., edited by Y. Fujino and T. Noguchi, 57-65. Tokyo: Springer.

- Muramatsu, S., and M. Koshihara. 2013. ““Naka-naka” Heritage Site Manifesto.” January 9. http://nakanakaisan.org/index_en.html

- Muramatsu Lab 2017. mASEANa Project 2017: Overcoming Some Issues of Modern Architectural Heritage Conservation in ASEAN. Tokyo: Institute of Industrial science, Tokyo University.

- Ng, M. K. 2002. “Property-led Urban Renewal in Hong Kong: Any Place for the Community?” Sustainable Development 10 (3): 140–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.189.

- Nikovic, A., and B. Manić. 2020. “Building a Common Platform: Integrative and Territorial Approach to Planning Cultural Heritage within the Framework of the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia 2021–2035.” In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Urban Planning, Regional Development and Information Society REAL CORP 2020: Shaping Urban Change. Livable City Regions for the 21st Century, Aachen. ( online).

- Non-profit Organization Nakanaka Heritage Committee. 2020. “NPO法人一関のなかなか遺産を考える会の概要.” https://www.ichinakanaka.com/blank-4

- Okabe, A. 2018. “A Critical View on Social Design in Japan.” In Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the Pacific Rim Community Design Network, edited by Pacific Rim Network. Singapore: National University of Singapore.

- Okata, J., and A. Murayama. 2011. “Tokyo’s Urban Growth, Urban Form and Sustainability.” In Mega Cities: Urban Form, Governance and Sustainability, edited by A. Sorensen and J. Okata, 15-41. Tokyo: Springer.

- Pendlebury, J., T. Townshend, and R. Gilroy. 2004. “The Conservation of English Cultural Built Heritage: A Force for Social Inclusion?” International Journal of Heritage Studies: IJHS 10 (1): 11–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1352725032000194222.

- Poulios, I. 2010. “Moving beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 12 (2): 170–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/175355210X12792909186539.

- Poulios, I. 2014a. “A Living Heritage Approach: The Main Principles.” In The past in the Present: A Living Heritage Approach, edited by I. Poulios, 129-133. Greece: Meteora.

- Poulios, I. 2014b. “Conclusion: The Contribution of a Living Heritage Approach to the Discipline of Conservation.” In The past in the Present: A Living Heritage Approach, edited by I. Poulios, 139-143. Greece: Meteora.

- Sham, H. 2017. “Imagining a New Urban Commons: Heritage Preservation As/and Community Movements in Hong Kong[J/OL].” ARI Working Paper, 2017, 260[2020-0613]. https://ari.nus.edu.sg/publications/wps-260-imagining-a-new-urban-commons-heritage-preservation-asand-community-movements-in-hong-kong/

- Siu, K.-C. 2008. “Street as Museum as Method: Some Thoughts on Museum Inclusivity.” International Journal of the Inclusive Museum 1 (3): 57–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.18848/1835-2014/CGP/v01i03/44528.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- St James Settlements. 2007. “Proposing Community Heritage Preservation Model through the Blue House Project.” In Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the Pacific Rim Community Design Network, edited by Pacific Rim Network. China: Quanzhou.

- Steinberg, F. 1996. “Conservation and Rehabilitation of Urban Heritage in Developing Countries.” Habitat International 20 (3): 463–475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(96)00012-4.

- Stenseke, M. 2009. “Local Participation in Cultural Landscape Maintenance: Lessons from Sweden.” Land Use Policy 26 (2): 214–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.01.005.

- Tang, W. 2017. “Beyond Gentrification: Hegemonic Redevelopment in Hong Kong.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (3): 487–499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12496.

- Truscott, M., and D. Young. 2000. “Revising the Burra Charter: Australia ICOMOS Updates Its Guidelines for Conservation Practice.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 4 (2): 101–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/135050300793138318.

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). 2011. “Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape.” https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul

- Waterton, E., and L. Smith. 2010. “The Recognition and Misrecognition of Community Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 4–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441671.

- Watson, S., and E. Waterton. 2010. “Heritage and Community Engagement.” International Journal of Heritage Studies: IJHS 16 (1–2): 1–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441655.

- Wiewel, W., and M. Lieber. 1998. “Goal Achievement, Relationship Building, and Incrementalism: The Challenges of University-Community Partnerships.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 17 (4): 291–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9801700404.

- Winter, T. 2014. “Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage Conservation and the Politics of Difference.” International Journal of Heritage Studies: IJHS 20 (2): 123–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2012.736403.

- Xia, X. 2017. The Generation of Power: An Ethnography of Urban Renewal in Hong Kong [权力的生成:香港市区重建的民族志]. Beijing: Social science academic press.

- Xia, X., and K. Chan. 2014. “On the Generation of Power of the Powerless: Taking Wedding Card Street Resident’s Movement in Hong Kong as a Case [论无权者之权力的生成以香港利东街居民运动为例].” Chinese Journal of Sociology (社会) 34 (1): 27-51.

- Xu, T. 2014. “NARA+20: Retrospective and Summary Assessment of Twenty Years Conservation Practice of Nara Document [《奈良真實性文件》20年的保護實踐回顧與總結——《奈良+20》聲明性文件譯介].” World Architecture (12): 106–107.

- Xu, T. 2019. Heritage: Cultural Conservation and Heritage [迈向文化性保护:遗产地的场所精神和社区角色]. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press.

- Yung, E., and E. Chan. 2011. “Problem Issues of Public Participation in Built-heritage Conservation: Two Controversial Cases in Hong Kong.” Habitat International 35 (3): 457–466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.12.004.

- Zhai, B., and P. C. Chan. 2015. “Community Participation and Community Evaluation of Heritage Revitalisation Projects in Hong Kong.” Open House International 40 (1): 54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-01-2015-B0009.

- Zhang, J. 2014. “Research and Reflections on Japanese University System and Salary and Reward System [日本高校体制及薪酬制度的研究与思考].” Journal of Beijing Union University (Humanities and Social Sciences) (北京联合大学学报(人文社会科学版)) 1: 106–116.

- Zhou, R., and J. Zhu. 2014. “Public Participation in Urban Renewal in Hong Kong [香港城市更新中的公民参与].” Greater Pearl River Delta Forum (大珠三角论坛) 2014 (1): 1–22.

- Zhou, X. 2017. “Development and Practices of Neighborhood Conservation-Based Community Building in Japan.” Landscape Architecture Frontiers 5 (5): 10. doi:https://doi.org/10.15302/J-LAF-20170502.