?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Many studies revealed that vegetation in parks evokes fear of crime for women in a certain environmental context, and it significantly inhibits the restorative qualities of urban green spaces. A quasi-experimental on-site study was conducted at two privately owned public spaces in a central business district of Seoul, to investigate what aspects of sites trigger women’s fear of crime and why. Female participants visited two contrasting sites (N = 30) – one with dense trees and one with an open lawn – at both day and night and indicated perceived fear intensity on interactive maps with four levels (0–3). In total, 540 overlaid grid cells were encoded using the presence of physical attributes, such as vegetation, street furniture, lighting, security camera, artwork, borders of buildings, and roads. A generalized linear model estimated the effects of the physical attributes to determine whether they were positively or negatively associated with assessed fear intensity. Insufficient lighting and absence of people after working hours at the wooded site induced a large increase in perceived fear intensity from daytime. In geographically mapping fear of crime, participants showed the highest level of fear for violence and sex crimes in the alley enclosed with woods.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Public spaces in dense urban centers are valuable sources of restorative green spaces, even on a small scale (Nordh et al. Citation2009; Haaland and van Den Bosch Citation2015; Tabrizian et al. Citation2018). Their spatial planning and maintenance are crucial in business districts, since many of them exist in private spaces (e.g., privately owned public spaces, known as POPS) that are meant to serve few public goals and are often fragmented spaces in between tall buildings without consideration for environmental contexts. Due to the lack of care for the setting, these spaces can create crime hotspots and fear, especially for women. Perceived safety in green spaces matters because a low level of perceived safety inhibits the restorative qualities of a public space (Tabrizian et al. Citation2018). Previous studies have revealed that physical features are closely related to potential crime opportunities and perceived safety (Fisher and Nasar Citation1992; Nasar and Fisher Citation1993; Nasar, Fisher, and Grannis Citation1993; Herzog and Miller Citation1998; Herzog and Flynn-Smith Citation2001; Blöbaum and Hunecke Citation2005). Many environmental features were identified as simultaneously positive factors of preference in natural settings and positive factors of fear of crime in urban settings (Fisher and Nasar Citation1992; Loewen, Steel, and Suedfeld Citation1993; Nasar and Fisher Citation1993; Herzog and Rector Citation2009). Surrounded by natural elements, enclosed settings provide visitors with sensory separation from artificial and hectic cityscapes, creating feelings of protection and restoration (Grahn and Stigsdotter Citation2010). However, visitors may also experience feelings of insecurity and danger in enclosed settings, which can inhibit restorative feelings (Herzog and Rector Citation2009; Jansson et al. Citation2013). Density and spatial arrangement of vegetation can interactively affect impressions of safety (Jorgensen, Hitchmough, and Calvert Citation2002; Jansson et al. Citation2013; Tabrizian et al. Citation2018). Due to the duality of perceived safety in relation to vegetation in parks, it is crucial to investigate the relationship between perceived safety and spatial features in urban parks to maximize their restorative potential.

This dual environmental perception seems to be rooted in Appleton’s (Citation1975) prospect and refuge theory, which is founded on the idea that people prefer places that offer enclosure and visibility simultaneously. Prospect is a measure of how well people can look ahead to anticipate whom or what they are likely to encounter, while refuge is the opportunity to flee at various points along the path or in a location (Fotios, Unwin, and Farrall Citation2015). In other words, visibility of others (“how much can I see?”) and visibility by others (“how much am I seen?”) are crucial features in determining the availability of protective spaces or flight routes in unknown spaces. Environmental features in parks that are used to create natural settings and provide concealment, such as shrubs and bushes, are major contributors to fearful reactions, especially in women (Nasar and Jones Citation1997). However, contrasting results have demonstrated that nature in urban settings is beneficial to people, demonstrating a link between high tree density and increased preference, sense of safety, and cognitive functioning (Kuo, Bacaicoa, and Sullivan Citation1998; Wells Citation2000). These contrasting views can be merged thus: whether environmental features promote relaxed or fearful reactions depends on the context in which they appear (Herzog and Flynn-Smith Citation2001). This context includes physical arrangement of features, cues to setting care (“broken windows” theory), prior knowledge about the place, and biases attributable to cultural, ethnic, or personality factors (Nasar and Jones Citation1997; Herzog and Miller Citation1998; Kuo, Bacaicoa, and Sullivan Citation1998). In addition, it is widely acknowledged that higher light levels increase pedestrians’ perceived safety, since it affects visibility at night (Vrij and Winkel Citation1991; Blöbaum and Hunecke Citation2005; Boomsma and Steg Citation2014). Hino, Ishii, and Fujii (Citation2014) investigated nine environmental factors on a pedestrian street’s perceived safety using a path analysis. The site’s brightness was the most influential factor on perceived safety, both directly and indirectly, and the vertical illuminance was found to be more significant than the horizontal illuminance. An indication of presence was also found to be influential on perceived safety, both directly and indirectly. They also demonstrated that vegetation management and maintenance positively affect perceived safety; however, it should be carefully observed because as vegetation grows, it changes the structure of visibility and openness and eventually mediates perceived safety. Surveillance and strict use regulations may increase perceived safety; however, these measures may also accentuate fear by increasing distrust among users (Ellin Citation1997).

Perceived danger in urban public spaces seems to be related more to the immediate fear of danger at a particular site, impacted by physical and social cues (Blöbaum and Hunecke Citation2005). Past studies used terms relating to both perceived danger/safety and fear of crime. Both reinforced “perceived safety” and reduced “fear of crime” can be interpreted as pedestrians’ reassurance that they can walk unaccompanied with confidence after dark without worrying about being attacked (Fotios, Unwin, and Farrall Citation2015). Even though fear of crime at a specific site does not necessarily correspond with actual crime incidence or empirical evidence, physical settings evoking fear can be hazardous in urban public spaces. In Ryder et al. (Citation2016)’s study, women reported lower perceived safety, higher levels of fear, more feelings of vulnerability, and more serious consequences of crime in crime hotspots (e.g., alleys and backstreets) compared to safe spots (e.g., open areas and shopping areas). Additionally, there was a significant interaction of location and the perceived risk of various crime types in this study.

The context of fear of crime in business districts is different from that in residential areas with familiar neighborhoods and relatively exclusive territories and communities of residents. Most previous studies focused on the fear of crime at large or mid-sized parks in residential districts. In this study, we investigated women’s fear of crime within two POPS, unique small urban public spaces, located in central business district of Seoul. Although POPS can be used as valuable restorative areas in urban public spaces, they have received little attention in the academic fields of urban planning and landscape design (Kayden Citation2000). Thus, the spatial arrangement and physical features of POPS should be reevaluated so that they can better serve as restorative resources for diverse users and as valuable assets in urban business districts. Unlike large urban parks existing independently from their surrounding built environments, the physical characteristics of POPS are interweaved into the urban fabric and interact with their surroundings and pedestrians. Thus, understanding the effects of physical features as well as their environmental contexts are equally important. It is a widely accepted notion that women feel a higher intensity of perceived danger than men in urban environments, especially after nightfall (Warr Citation1990; Boomsma and Steg Citation2014). Women’s fear of crime in urban public spaces restricts their mobility and physical activities. Recently, there have been growing concerns and movements towards rethinking and regenerating marginalized urban public spaces in terms of gender equality (Franck and Paxson Citation1989; Koskela Citation1997; Beebeejaun Citation2017). It is important for city governments to make cities and environments safer and more inviting for women even as they work to maximize the well-being and quality of life of inhabitants (Trench Citation1992; Jiang et al. Citation2017).

The present study aimed to investigate young women’s site-specific fear of crime in POPS in a central business district in relation to environmental features. The main goal was to examine the physical features associated with fear of crime in urban public spaces in different environmental contexts. The questions to be answered in this study are: (1) How do surrounding facilities affect perceived fear of crime (e.g., retail facilities versus pure offices)?; (2) How do site-specific physical factors affect fear of crime in different environmental contexts (open versus enclosed)? What features within public spaces were associated with fear positively or negatively? Do these responses differ depending on time of day?; and (3) What kind of crimes are women afraid of in relation to environmental features and why? Answering these questions would be beneficial to plan valuable urban public spaces and to maximize their restorative qualities.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Research design

To investigate fear-evoking factors in different environmental contexts, two POPS were selected: one with a wooded enclosure surrounded exclusively by office buildings and the other with open lawn near street retail facilities (see for site comparison). Physical attributes (i.e., building envelope, vehicular road, pedestrian path, street furniture, lighting, surveillance camera, trees, and shrub/lawn) were evaluated for whether they were fear-evoking or fear-reducing factors for women. In addition, the specific crimes that women were fearful of and why, were investigated. The present study implemented a quasi-experimental on-site study to maximize ecological validity. The questionnaire on a tablet screen included interactive fear mapping, which permitted participants to map their fear intensity at two POPS in the central business district of Seoul. The same participants visited both sites twice – once during the day and once at night (within-subjects design).

Table 1. Site comparison

2.2. Participants

This research involved human participants, and the methods were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board. We launched online advertisements on the portal website seeking female volunteers aged 20–39, who are not familiar with two sites. Two visits, during the day and at night, at each of the two sites were mandatory for all participants. A total of 30 Korean women were randomly selected out of 60 volunteers (mean age = 25.73, SD = 2.53). The participants’ demographic information is presented in .

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 30)

2.3. Study sites

Similar to many other major cities, Seoul has also implemented POPS policy to secure and increase valuable public space (Ministry of Land, Citation2017). Among 25 autonomous districts in Seoul, the district of Jung-gu was selected as it met three criteria: 1) it is a central commercial/business district; 2) it has high crime incidence rates for theft, sexual assault, and assault (Korean National Police Agency Citation2019); and 3) it has high dissatisfaction in street walkability during both day and night (The Seoul Institute Citation2018). Two similarly sized POPS (400–600 m2) in Jung-gu – the old city center business district and Seoul’s largest central commercial area – were selected as the study sites. Both sites are near the Seoul City Hall and are within 100 m of a metro station that serves over 102,000 daily passengers. The distance between Sites A and B is 450 m. shows the different physical settings, and environmental contexts of the two sites. The scale and composition of the two public spaces are similar; however, they have contrasting contexts (see Supplementary material 1, S1 for satellite map and surrounding street views).

Site A belongs to an office building tower without retail facilities (). The sidewalk of the building front faces a six-lane road. There is an entrance to a park to the right of the building entrance, followed by two parallel wood decks with six benches each, and the decks are connected in the middle. At the end of the deck, there is a secluded smoking area. There is a sign at the entrance indicating that the site is a POPS and is open to the public; however, most visitors were employees working at this office building. Site A is densely surrounded by tall pine trees and bushes. The two entrances and the smoking area are connected by a pebble road to appear more natural. Lighting fixtures are installed mostly at ground level (see Supplementary material 1, S2). Trees are lit from the ground; however, the light intensity and distribution are not sufficient to illuminate foliage. Thus, only the underside of the tree trunk is illuminated. Footlights along the path are recessed under the seating. In this space, it is typically difficult to recognize a person’s face. At night, there are few visitors, and it is very tranquil. A surveillance camera is installed at the entrance of the site. As Site A was managed by an office building without commercial facilities and relatively fewer pedestrians from outside, the site was well-maintained and clean.

Site B is also located to the right of a main building entrance (). The building is mixed-use with retail shops on the lower floors and offices on the higher floors. At the ground floor, there are street retail spaces consisting of a pub, restaurants, and a convenience store with outdoor seating. Site B is located at the back of the main boulevard. Across the road, there are relatively old, poorly managed two-story buildings, contrasting with this newly built, mixed-use tower. With these surroundings and extraneous pedestrians to visit commercial facilities, Site B is relatively untidier and more disordered than Site A. There are tall trees at the edges of the sidewalk, and two open lawns separated by an access to the building entrance in the middle. Two benches face the windows of a convenience store and a restaurant, and three more benches are located in the middle, facing the sidewalk and across the street. There is an 8 m-high cylindrical metal sculpture (see Supplementary material 1, S3). Compared to Site A, this site has more abundant artificial lighting mixed with streetlight poles and bollards at night. Moreover, because Site B is relatively open without any obstacles to prevent light distribution and there is a secondary light source – the windows of the stores – the site is evenly lit. Both corners of this side of the building have surveillance cameras installed.

2.4. Procedure and measurement

The survey was conducted between May 11 and 22 May 2019. The average temperature of the period was 26°C during the day and 20°C at night. The weather was sunny throughout the survey period. The participants visited the two nearby sites – once during the day and once at night. Randomly divided by two groups with SPSS random case selection, one group visited Site A first and Site B consequently, and the other group did vice versa. On the first visit during the day, researchers explained the procedure, and participants signed the consent form. Next, participants strolled freely around the park and completed the questionnaire on 10-inch iPads. They then walked the five-minute route to the next site and followed the same procedure. The total time spent at the two sites was approximately 30 minutes. The following week, nighttime visits were scheduled and followed the same survey procedure as during the daytime visits. After completing all the questionnaires for all visits, general demographic information (age and job) was collected, and each participant was provided 30,000 KRW as compensation.

The questionnaire involved interactive fear mapping of the site (see Supplementary material 1, S4 for the interactive screen). Participants were asked to designate fearful spots on each illustrated map by touching the overlaid grid cells with their fingertips. Participants could intuitively demonstrate their fear intensity based on the number of times they touched the grid cells. One touch indicated intensity of level 1, which turned the cell yellow; two touches (level 2) turned the cell orange; three touches (level 3, the highest fear intensity) turned the cell red; and leaving the cell untouched indicated no fear (level 0). With the tablet survey, the interactivity and validity could be maximized, measuring fear intensity in relation to the physical features of sites.

Floor plans of sites indicating major physical features were illustrated with color. Physical features included borders of the building area, pedestrian and vehicular roads, vegetation, points of lighting, Closed-circuit Television (CCTV), and sculpture. The scale of the overlaid grids was 2 m × 2 m each, which was considered an appropriate size to draw on maps fitted in a 10-inch screen with fingertips. To cover the entire sites on the tablet screen, an area of 40 × 54 m with 540 grid cells (horizontal 20 × vertical 27) was included. The indoor building area was not included in the statistical analysis. After drawing their fear intensity map, participants were asked what kind of crime they were fearful of and why (multiple choice).

3. Results

3.1. Mean fear intensity

Collected data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 and visualized with Microsoft Excel 2010. Each cell contained encoded data with physical features and fear intensity at four levels (0–3) rated by all participants. EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) describes

, the sum of rated fear intensities by 30 participants about the specific cell q (

is the rated fear intensity by each participant). Next in EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) , the Mean fear intensity (MF) was calculated by averaging based on the number of analyzed cells (excluding indoor areas, data for 414 cells for Site A and 450 cells for Site B were analyzed).

For Site A, MF was 4.44 during the day, which increased steeply to 9.07 at night (). On the other hand, for Site B, MF was the same during the day and at night (M = 5.62). To compare the mean fear intensity of the two sites, a t-test was conducted.

Table 3. Mean fear intensity of grid cells at the two sites

During the day, the difference between the MF at Site A and Site B was statistically significant, t (785) = -3.03, p < 0.01. At night, MF at Site A was significantly higher than that at Site B (t (558) = 5.32, p < 0.001). When fear intensity of day and night was averaged, MF at Site A was higher than at Site B (p < 0.05).

3.2. Mapping the site-specific fear of crime

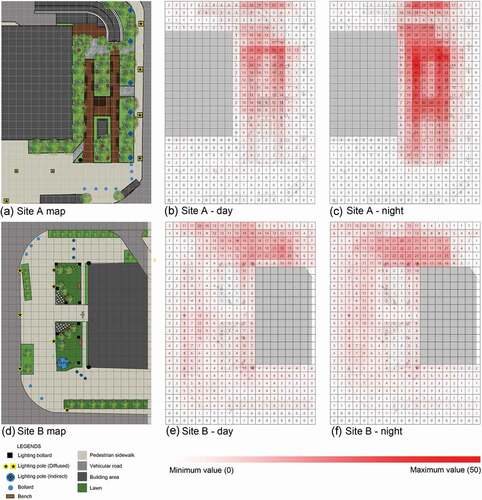

In , the total fear intensity of each cell is indicated geographically for the two sites at both day and night. With an overlaid map, we can see that the forested setting enclosed with vegetation at Site A evoked very high fear intensity. The hotspots were located at the end of the wooded setting where there is an obstructed alley leading to an independent smoking zone. Fear of crime intensified as participants went deeper into the area enclosed by high-density bushes and trees. The total fear intensity at this spot ranged from 20 to 36 during the day and from 30 to 50 at night. The sidewalk facing the vehicular road was perceived to be safe (range 0–3). Another spot that evoked fear of crime was the northeast corner of the building, where an entrance to an underground parking garage is located.

Figure 3. Hotspots of fear intensity: (a) Site A map; (b) Site A – day; (c) Site A – night; (d) Site B map; (e) Site B – day; (f) Site B – night.

For Site B, the peak fear intensity was lower than at Site A (maximum 28 versus 36 in the day, 25 versus 50 at night). However, the mean fear intensity of Site B was higher than that of Site A during the day. Participants perceived the north side of the building to be the most dangerous hotspot both during the day (range 10–28) and at night (range 14–23). This spot also contains an entrance to underground parking. Other spots evoking moderate fear intensity (range 5–12) contained tall trees along the edge of sidewalks, which work as a barrier between Site B and old, poorly managed commercial buildings.

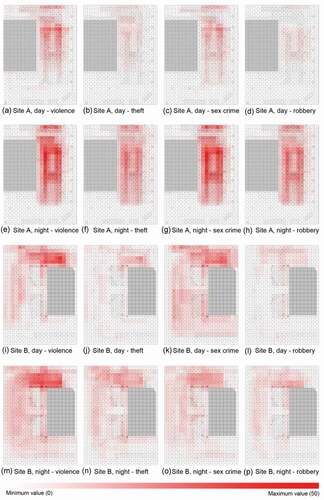

displays fear hotspots associated with different types of crime. As shown, the “forest alley zone” is the most fear-evoking hotspot at night, especially for violence and sex crimes. Based on participants’ responses regarding the type of crime feared (), the most concerning type – both during the day and at night – was “violence” for both Site A (83.3% in the day, 90.0% at night) and Site B (73.3% in the day, 76.7% at night). At Site A, the second most concerning crime type was “sex crimes” (50.0% in the day, 76.7% at night). At Site B, “sex crime” was also the second most concerning during the day (50.0%), while “theft” was more of a concern at night (53.3%) than “sex crimes” (36.7%). This seems to be due to the presence of commercial facilities at Site B, while Site A has no commercial facilities around the site.

Table 4. Type of crime feared at the two sites

Figure 4. Hotspots of fear intensity by crime type: (a–d) Site A – day: (a) Violence; (b) Theft; (c) Sex crime; (d) Robbery; (e–h) Site A – night: (e) Violence; (f) Theft; (g) Sex crime; (h) Robbery; (i–l) Site B – day: (i) Violence; (j) Theft; (k) Sex crime; (l) Robbery; (m–p) Site B – night: (m) Violence; (n) Theft; (o) Sex crime; (p) Robbery.

3.3. Why fear of crime was evoked

For fear-evoking reasons at Site A (), 76.7% of participants checked “darkness and obscure spots” even during the day, and all participants checked this reason at night. The second greatest cause for fear was the “absence of security facilities” (50.0%) in the day and “absence of people” at night (86.7%). During the day at Site B, 63.3% checked “poor management,” and 50.0% checked “absence of people.” At night, “darkness and obscure spots” was picked by 53.3%, and a presence of “suspicious visitors and acts” by 50%.

Table 5. Reasons for fear

3.4. Positive versus negative predictors associated with fear of crime

A generalized linear model was employed to determine the effects of physical attributes on fear of crime. shows the effects of predictors during both day and night. During the day, significant negative predictors of fear at Site A were lighting poles (B = -3.90, p < 0.001) and CCTV (B = -3.56, p < 0.01), while benches (B = 6.88, p < 0.001) and low lighting (B = 6.80, p < 0.001) significantly increased fear levels. At night, these effects were even more intensified, as benches (B = 20.12, p < 0.001) and low lighting (B = 10.60, p < 0.001) were significant positive factors of fear and the effect size was greater. Shrubs or lawn significantly increased fear at night (B = 4.04, p < 0.01). Meanwhile, lighting poles (B = -6.74, p < 0.001) and CCTV (B = -4.50, p < 0.001) were predicted as negative factors of fear intensity at night.

Table 6. Predictors of fear of crime

For Site B, the estimated effects of predictors differed from Site A. With different environmental contexts, some fear-evoking predictors at Site A appeared to be fear-reducing predictors at a different time, or vice versa. For example, the adjacent building area indicated significantly higher fear at night (B = 1.33, p < 0.05), as did surveillance cameras during the day (B = 4.76, p < 0.001) and at night (B = 4.38, p < 0.001). Pedestrian sidewalks were also a positive factor of fear intensity during the day (B = 2.21, p < 0.001) and night (B = 3.27, p < 0.001). However, shrubs or lawns were negative factors of fear at night (B = -1.67, p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. The effects of environmental contexts and physical features

The present study investigated how women perceive danger in relation to physical features of public open spaces in a central business district. In comparing mean fear intensity for the two sites, the open one with street retail facilities (Site B) induced less fear of crime than the enclosed one surrounded exclusively by office buildings (Site A). This result corresponds with Ryder et al. (Citation2016)’s study, which compared women’s perceived vulnerability, safety, risk of crime, and victimization seriousness at alleys versus open shopping areas. However, the transition from day to nightfall at both sites was observed with mediated effects of their user demographics. There were more people taking a break in the POPS exclusively surrounded by office buildings during the day, and the fear of crime was significantly lower than at the POPS with retail facilities. Meanwhile, the retail facilities became more active at night and had more pedestrians, and participants were more worried about suspicious people and theft than the physical aspects of the site. After nightfall, the office buildings became vacant, and the absence of people along with the darkness of the enclosed wooded setting intensified users’ fear of crime. At both day and night, fear intensity reached its peak in the densest vegetation area and obscure spots near the underground parking structure; these findings align with those of existing studies (Nasar and Fisher Citation1993; Tabrizian et al. Citation2018).

A previous study demonstrated a significant interaction of location and perceived risks by crime type (Ryder et al. Citation2016). In crime hotspots like alleys, there was no significant difference between women’s perceived risks for different crime types (robbery, rape, and physical assault). However, in open areas, the perceived risk of robbery was significantly higher than the risk of physical assault and rape. Robbery was the most worrying crime type, and rape was the least worrying crime type in their study (physical assault was in the middle). However, in this study, perceiving risks of violence (physical assault) was the most worrying crime type of the two sites, and the next was sex-related crimes. This incongruence might be induced by the heterogeneous participants’ ethnicity and culture or the sites’ different environmental contexts. With the combination of darkness and absence of people in the woody alley, women perceived a higher risk of sex crimes and robbery (which cause serious consequences) next to violence more at night than in an open setting. Although the participants felt the open retail setting was relatively poorly managed and invited more suspicious visitors than the woody enclosed setting, sufficient brightness and presence of people at night mitigated the general fear intensity. However, the circumstances created more concerns about theft (which creates relatively light injuries but a loss of property).

With the results from previous studies and measuring women’s general fear intensities from two sites, the present study attempted to predict the positive/negative effects of the physical features on fear of crime for further examination. In examining fear-evoking and fear-reducing factors, significant factors differed according to environmental contexts. As the literature revealed, vegetation appeared to be both a restorative and fear-inducing element depending on the environmental context. We divided vegetation predictors into “tree” and “shrub/lawn.” “Shrub/lawn” appeared to be a significant fear-evoking factor in the enclosed setting only at night; however, it also appeared to be a significant fear-reducing factor in the open setting. This seemed to be due to the interaction effect with artificial lighting at night. Although the effect of “tree” was not significant, higher fear intensity was noted in grid cells corresponding with trees, meaning that trees obstructed visibility and provided concealment for criminal potentials. The adjacency of building walls only worked as a significant fear-evoking factor in the open setting at night. Vehicular roads did not influence the fear of crime significantly. Instead, the pedestrian sidewalk in the open setting and seating in the wooded setting significantly increased fear intensity. Especially in the enclosed setting, a dense vegetation enclosure creating obscure spots inside the park and the existence of greenery and benches significantly increased fear intensity. Only lighting poles, which provide wide and even light distribution, significantly decreased fear intensity. However, the presence of lighting did not have a significant effect on perceived safety in the relatively bright open space. These results align with those of previous studies, indicating that in the presence of adequate brightness level (above 30 lux), perceived safety does not increase as the light level increases (Boyce Citation2014; Fotios and Castleton Citation2016). The presence of public art (in this study, sculpture) did not induce significant difference in fear intensity, revealing inconsistent results with previous study testing positive fear-mitigating effects of art murals (Sakip, Bahaluddin, and Hassan Citation2016). Additionally, the presence of a surveillance camera (CCTV) induced inconsistent results between the two sites. We posit, however, that surveillance as a fear-evoking factor may be due to the failure of realizing the presence of cameras, and that the spots were actually hotspots of fear of crime. The ability to realize the presence of security cameras could depend largely on the installation method, color contrast with the background, and placement – whether they are installed on a stand-alone pole or attached on the building.

From our observation, the atmosphere of the two sites was largely influenced by the surrounding environment and visitor demographics with the transition of day to night. As POPS, the degree of open “publicness” and closed “privateness” of the sites affected user demographics and perceived safety of visitors. The site with dense greenery provided isolation from its surroundings (Site A), and users were mostly restricted to employees at the office building. Thus, because the visitors were not diverse users of the public space, this site appeared more like the office tower’s private property. During the day, a time in which the place is filled with internal daily users, participants felt a strong territoriality and sense of security. However, when most internal users leave for the night, empty, dark, and obscure spots are revealed at the space. This atmosphere evoked a higher fear of crime in relation to physical features at night. The business district’s changing demographics created significant differences between day and night regarding environmental perception in this POPS. In contrast, little change was observed in fear intensity at Site B, which has a more open setting, between day and night. The combination of the mixed-use building with retail shops and the open environmental setting made the space less exclusive and secluded. This POPS attracted diverse users, and unpredictable penetration by pedestrian sidewalks became a greater fear-evoking factor rather than the physical features.

4.2. Significance and limitations

The present study contributes to our understanding of women’s fear in urban public spaces – particularly, its association with physical features. Regardless of actual crime, the spatial arrangement, vegetation, and the interaction effect with lighting after nightfall can evoke or mitigate fear of crime in women – a group that experiences persistent anxiety regarding possible violence and sex crimes. A noteworthy limitation of this study is the intrinsic weakness of a quasi-experimental study in controlling extraneous variables and small sample size due to the two mandatory on-site visits for each site within limited time schedule to minimize unexpected variables. However, we believe that the unique characteristics of POPS could be observed qualitatively with demographics from the surrounding urban environment with ecological validity on sites using the quasi-experimental method.

Second, order effects were not considered in this study. If participants visited the site at night first, the fear might have been higher without having prior daytime experience at the sites. Our intention was to compare the nighttime environment after understanding the sites and surrounding built environment. Another limitation is that seasonal difference was not considered a crucial factor. Nevertheless, in winter, the perception of fear could differ with colder temperatures, changes in scenery without foliage, and with fewer people present.

5. Conclusions

Though intended as lively, restorative public spaces in a business district, POPS carry a unique duality of private and public property characteristics. Given the inherent incorporation of these spaces into their surrounding environments and socio-demographic variables, we can suggest following implications to designers and planners.

To maximize restorative qualities of POPS, the balance between “enclosure” and “openness” is crucial in trading off perceived restorative value and safety. It is strongly suggested to avoid dark and obscure alleys surrounded by trees or tall shrubs. In Tabrizian et al. (Citation2018), a four-sided tree arrangement precipitously dropped perceived safety in park settings. Thus, it is recommended to keep at least one side open, and to eliminate branches of tall trees at or below the sight line to secure visibility (Mak and Jim Citation2018). In addition, considering the interaction of lighting, sophisticated lighting distribution should be reexamined with landscape design (e.g., fully grown heights and trimmed shapes of trees and shrubs). Even if lighting with low height provides coziness and a restorative atmosphere within a landscape, it should be provided with proper photometry of light balanced with general ambience to provide vertical illumination on peoples’ faces to reassure park users. Accentuating security facilities with color contrast against background could be helpful for users to realize their presence.

This study investigated two public spaces in different environmental contexts with ecological validity and generated a detailed geographical association of women’s fear in relation to physical features of public spaces. As valuable urban assets in central business districts, the perceived safety at POPS or pocket parks should be further studied in various environmental contexts to maximize restorative qualities and achieve the intended public functions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.2 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Appleton, J. 1975. The Experience of Landscape. London: Wiley.

- Beebeejaun, Y. 2017. “Gender, Urban Space, and the Right to Everyday Life.” Journal of Urban Affairs 39: 323–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2016.1255526.

- Blöbaum, A., and M. Hunecke. 2005. “Perceived Danger in Urban Public Space: The Impacts of Physical Features and Personal Factors.” Environment and Behavior 37: 465–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916504269643.

- Boomsma, C., and L. Steg. 2014. “Feeling Safe in the Dark: Examining the Effect of Entrapment, Lighting Levels, and Gender on Feelings of Safety and Lighting Policy Acceptability.” Environment and Behavior 46: 193–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512453838.

- Boyce, P. R. 2014. Human Factors in Lighting. NW: CRC Press.

- Building Act of 2017, Republic of Korea Law, Securing open spaces for public purposes. Act no. 14792, Chapter 4, Article 43. (2017). Accessed 08 June 2021. https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=193412&chrClsCd=010203&urlMode=engLsInfoR&viewCls=engLsInfoR#0000

- Ellin, N. 1997. Architecture of Fear. New Jersey: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Fisher, B. S., and J. L. Nasar. 1992. “Fear of Crime in Relation to Three Exterior Site Features: Prospect, Refuge, and Escape.” Environment and Behavior 24: 35–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916592241002.

- Fotios, S., and H. Castleton. 2016. “Specifying Enough Light to Feel Reassured on Pedestrian Footpaths.” Leukos 12: 235–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15502724.2016.1169931.

- Fotios, S., J. Unwin, and S. Farrall. 2015. “Road Lighting and Pedestrian Reassurance after Dark: A Review.” Lighting Research & Technology 47: 449–469. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1477153514524587.

- Franck, K. A., and L. Paxson. 1989. “Women and Urban Public Space.” In Public Places and Spaces, edited by I. Altman and E. Zube. Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Grahn, P., and U. K. Stigsdotter. 2010. “The Relation between Perceived Sensory Dimensions of Urban Green Space and Stress Restoration.” Landscape and Urban Planning 94: 264–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.10.012.

- Haaland, C., and C. K. van Den Bosch. 2015. “Challenges and Strategies for Urban Green-space Planning in Cities Undergoing Densification: A Review.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 14: 760–771. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.009.

- Herzog, T. R., and J. A. Flynn-Smith. 2001. “Preference and Perceived Danger as a Function of the Perceived Curvature, Length, and Width of Urban Alleys.” Environment and Behavior 33: 653–666. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973179.

- Herzog, T. R., and E. J. Miller. 1998. “The Role of Mystery in Perceived Danger and Environmental Preference.” Environment and Behavior 30: 429–449.

- Herzog, T. R., and A. E. Rector. 2009. “Perceived Danger and Judged Likelihood of Restoration.” Environment and Behavior 41: 387–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508315351.

- Hino, K., N. Ishii, and S. Fujii. 2014. “Environmental Effects on and Structure of Fear of Crime in the Nighttime - Case Study on Pedestrian Street in Tsukuba Science City.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 79 (696): 445–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.79.445.

- Jansson, M., H. Fors, T. Lindgren, and B. Wiström. 2013. “Perceived Personal Safety in Relation to Urban Woodland vegetation–A Review.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 12: 127–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2013.01.005.

- Jiang, B., C. N. S. Mak, L. Larsen, and H. Zhong. 2017. “Minimizing the Gender Difference in Perceived Safety: Comparing the Effects of Urban Back Alley Interventions.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 51: 117–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.012.

- Jorgensen, A., J. Hitchmough, and T. Calvert. 2002. “Woodland Spaces and Edges: Their Impact on Perception of Safety and Preference.” Landscape and Urban Planning 60: 135–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00052-X.

- Kayden, J. S. 2000. Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Korean National Police Agency. 2019. “Statistics for Crime Inicidence.” [ Online]. Accessed 25 November 2019. https://www.police.go.kr/www/open/publice/publice03_2018.jsp

- Koskela, H. 1997. “Bold Walk and Breakings: Women’s Spatial Confidence versus Fear of Violence.” Gender, Place & Culture 4: 301–320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09663699725369.

- Kuo, F. E., M. Bacaicoa, and W. C. Sullivan. 1998. “Transforming Inner-city Landscapes: Trees, Sense of Safety, and Preference.” Environment and Behavior 30: 28–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916598301002.

- Loewen, L. J., G. D. Steel, and P. Suedfeld. 1993. “Perceived Safety from Crime in the Urban Environment.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 13: 323–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80254-3.

- Mak, B. K. L., and C. Y. Jim. 2018. “Examining Fear-evoking Factors in Urban Parks in Hong Kong.” Landscape and Urban Planning 171: 42–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.11.012.

- Nasar, J. L., and B. Fisher. 1993. “‘Hot Spots’ of Fear and Crime: A Multi-method Investigation.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 13: 187–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80173-2.

- Nasar, J. L., B. Fisher, and M. Grannis. 1993. “Proximate Physical Cues to Fear of Crime.” Landscape and Urban Planning 26: 161–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(93)90014-5.

- Nasar, J. L., and K. M. Jones. 1997. “Landscapes of Fear and Stress.” Environment and Behavior 29: 291–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659702900301.

- Nordh, H., T. Hartig, C. Hagerhall, and G. Fry. 2009. “Components of Small Urban Parks that Predict the Possibility for Restoration.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 8: 225–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2009.06.003.

- Ryder, H., J. Maltby, L. Rai, P. Jones, and H. D. Flowe. 2016. “Women’s Fear of Crime and Preference for Formidable Mates: How Specific are the Underlying Psychological Mechanisms?” Evolution and Human Behavior 37 (4): 293–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.01.005.

- Sakip, S. R. M., A. Bahaluddin, and K. Hassan. 2016. “The Effect of Mural on Personal Crime and Fear of Crime.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 234: 407–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.258.

- The Seoul Institute. 2018. “The Seoul Research Data Base.” [ Online]. Seoul, Korea. Accessed 25 November 2019. http://data.si.re.kr/node/523

- Tabrizian, P., P. K. Baran, W. R. Smith, and R. K. Meentemeyer. 2018. “Exploring Perceived Restoration Potential of Urban Green Enclosure through Immersive Virtual Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 55: 99–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.01.001.

- Trench, S. 1992. “Safer Cities for Women: Perceived Risks and Planning Measures.” Town Planning Review 63: 279. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.63.3.r16862416261h337.

- Vrij, A., and F. W. Winkel. 1991. “Characteristics of the Built Environment and Fear of Crime: A Research Note on Interventions in Unsafe Locations.” Deviant Behavior 12: 203–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.1991.9967873.

- Warr, M. 1990. “Dangerous Situations: Social Context and Fear of Victimization.” Social Forces 68: 891–907. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2579359.

- Wells, N. M. 2000. “At Home with Nature: Effects of “Greenness” on Children’s Cognitive Functioning.” Environment and Behavior 32: 775–795. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160021972793.