ABSTRACT

This research aimed at developing strategies for the renovation of old shophouses in Bangkok ready for mass adoption and application. Shophouses were built with typical designs in a massive number in Bangkok during the 1960s and 1970s. They are now deteriorating, but still occupy a great proportion of the land near the city center.

To make shophouse renovation easy for mass adoption and application will allow Bangkok’s population to have more choices of housing that suit their lifestyle and support their wellbeing. It challenges the mainstream perception of seeing only the choices of living in a condominium near the center or in a suburban house.

By observation and literature review, the research categorized typical features and problems of old shophouses into four groups; (i) space and form, (ii) climate, (iii) wellbeing, and (iv) construction. After case studies, designing, and constructing a prototype renovation design, the research concluded with design strategies to increase the space flexibility, climatic responsiveness, safety, aesthetics, and hygiene. Taking procedural and legal limitations, and the minimal involvement of professionals and the authority into account, maintaining particular features of existing buildings as much as possible and adding new features as little as possible were also suggested.

These strategies would promote mass renovation of shophouses. By reducing demolition and supporting urban redevelopment, they would potentially help reviving urban heritage and reducing carbon footprint.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The shophouse is a modern and living heritage of Southeast Asia. Like many countries in the region, shophouses in Thailand are testimonies of the country’s everyday modernity and ordinary people’s, mostly Chinese descendants, ambition for a better life and expression of identity through various historical periods (see, e.g., Fusinpaiboon Citation2020; Li Citation2007; Lim Citation1993). To maintain, renovate, and incorporate old shophouses in urban redevelopment projects potentially contribute to a good balance between the preservation of lived experience in the place-making process and the recreation of sustainable and liveable city (Mosler Citation2019).

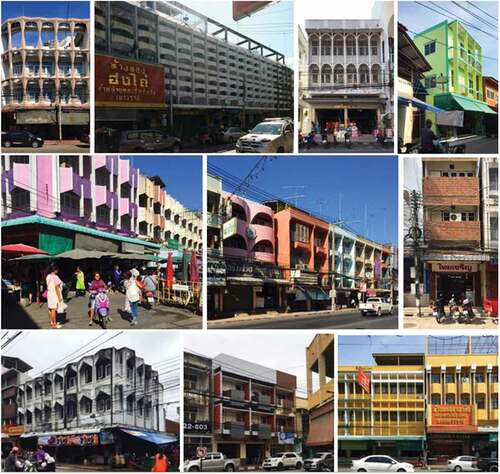

The main character of shophouses is that they are multiple-unit buildings built in rows. The original uses were a commercial ground floor and residential upper floors. Even though shophouses were built in Thailand, especially in Bangkok, as early as the second half of the 19th century in similar designs and styles to those in many Southeast Asian cities, such as Singapore, Penang, Jakarta, and Phnom Penh (Chulasai Citation2007), they became a major part of the morphology of Thailand’s urban area during the post-war-economic-boom years of the 1960s and 1970s (Tiptus and Bongsadadt Citation1982, 365–366), in which the National Economic Plans pushed the average economic growth to almost 7% per year (Wiboonchutikula Citation1984, 326). More than 50% of all building construction in Thai cities in the 1960s was shophouses (Sternstein and Daniell Citation1976, 111–115). By the mid-1970s, approximately 70% of the ~2.8 million population of Bangkok Metropolitan area lived in shophouses, giving an estimated ~400,000 shophouse units (Bongsadadt Citation1981, 33). In terms of architectural characters, shophouses built in Thailand during the 1960s and 1970s were mainly what could then be called a modern style ().

1.2. Problems and future of shophouses

Focusing in Bangkok, shophouses from the 1960s and 1970s still occupy a major part of the city centre and urban fringes nowadays even though their popularity has dropped dramatically since the 1980s.

In the 1980s, the shophouse was blamed for traffic jams, pollution, and disorderliness of the city (Problems of Shophouses Citation1981). Air-conditioned shopping centres started to replace the vibrant street life previously made possible by shophouses. Extensions of the road network, the construction of expressways, and higher ownership of cars promoted suburban developments that attracted many of the original owners, offspring, and residents of shophouses to leave them for suburban housings (Tunphibulwongs Citation1977, 68–69).

Nowadays, a large number of shophouses are running down. Many are abandoned or inefficiently used. Most have gone through uncontrolled alterations, sometimes creating an unhygienic environment and structural risk. Many shophouses have been demolished en-bloc to make way for new high-rise condominiums. However, not all locations occupied by shophouses in the city are suitable or possible to be redeveloped into high-rise condominiums. Therefore, the massive number of existing shophouses and the above situation have assured their persistence in Bangkok and these are unlikely to be changed dramatically soon ().

Figure 2. Rows of shophouses juxtaposed with a high-rise residential condominium in Bangkok

Accordingly, there is a future for shophouses and those who want to live and/or do business in them. This is because the original advantages of shophouses, namely good locations and flexible space, have recently returned to be relevant.

However, most of the existing shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s need to be renovated before a new use. Creative designs of shophouse renovation have been developed and published recently, but they are still minor in number compared with the number of existing shophouses in Bangkok. The greater the number of renovated shophouses, the more impact they could contribute to the wellbeing of Bangkok residents. And as far as sustainability is concerned, a mass renovation of shophouses would join a worldwide awareness in renovating old buildings in old cities, instead of replacing them with new-builds or endlessly expanding the city, to reduce carbon emission from demolition, construction and transportation (Merlino Citation2018).

1.3. Scope of research

Given the massive number of old shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok and the fact that a great number of them need renovation, this research aimed to explore strategies for shophouse renovation that could be easily adopted and adapted by the masses. Research questions were: what are the typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok?; what are the design solutions for the renovation that respond to the typical features, limitations, and problems?; what design solutions can be easily adopted and adapted by the masses? This research does not fall into a conservation field, but rather it is positioned within the field of studies engaged in the development of shophouses, and the design and renovation of them for the sustainable future of Asian cities, as seen in a number of publications in the past decade (see, e.g. Al-Obaidi et al. Citation2017; Aranha Citation2013; Kubota, Toe, and Ossen Citation2014; Tan and Fujita Citation2014; Tohiguchi and Chong Citation2018; Wakita and Shiraishi Citation2010).

1.4. Research objectives

The three main objectives of this research were as follows

(i) Study the current designs of renovation that responded to the typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok and evaluate them in terms of possibilities for mass adoption and application.

(ii) Design a prototype shophouse renovation that can be easily adopted and adapted by the masses.

(iii) Establish a set of strategies for mass adoptions and adaptations of shophouse renovation.

2. Materials and methods

The methodology of this research had a threefold approach. Firstly, to define the typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok. Secondly, to set the criteria for the design strategies of renovation that can be easily adopted and adapted by the masses. Thirdly, to explore, evaluated, and create a guideline of design solutions for the renovation.

The typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok were identified from the literature on the development of shophouses in Thailand. This literature consisted of primary sources (a catalogue of shophouse designs published in Citation1979) () and secondary sources, such as academic papers and graduate research studies, whose topics focussed on shophouses in Thailand.

Figure 3. Examples of shophouse designs and bills of quantities, published in 1979 in a catalogue

After defining the typical features, limitations, and problems of old shophouses, criteria for the design strategies of renovation were set. A set of design criteria categorized by topics relevant to building renovation comprises (i) space and form, (ii) climate, (iii) wellbeing, and (iv) construction. This set of criteria is informed by Žegarac Leskovar and Premrov (Citation2019)’s Integrative Approach to Comprehensive Building Renovations. In doing so, all issues related to the typical features, limitations, and problems of old shophouses were first categorized. Then, the design directions responding to all the issues were set. The directions not only responded to the typical features, limitations, and problems of old shophouses, but also targeted mass adoption and adaptation.

Accordingly, the procedures ranged from project initiation, design, application for building permission, the production of construction drawings, and construction. These were reviewed and integrated into the criteria. Detailed analysis of the law and regulations on building and construction, especially those related to shophouse renovation, was also included. All these set the criteria for the design exploration in the following stage.

Once the design criteria and directions were set, design ideas responding to them were explored, tested, and evaluated. It started with case studies of shophouse renovation. The selected cases were the economical and creative renovation of typical shophouses. Then, another case of the renovation of another building type was studied. This was not a shophouse but was more directly relevant to the research objective aiming to make renovation easy for mass adoption and application. Then, a prototype was designed and constructed to test design ideas gained from the case studies in a real situation. Lastly, a guideline for shophouse renovation for mass adoption and application was created.

Figure 4. A views on the second floor of thingsmatter’s aTypical Shophouse showing the use of operable partitions at the mid-bay to create a bedroom at night and to make the living room larger during daytime. It also shows the separation of corridors and staircases (at their original locations) from the main space to increase privacy. A double wall is seen on the left, increasing acoustic and insulating qualities of the existing party wall. A door to enter the toilet at the rear-bay is full-height and translucent, allowing natural light to pass transparent enclosure and the door to interior space. The location of the toilet itself at the periphery ensures good ventilation, hygiene, and new plumbing system easy to be maintained

2.1. Literature review and observation: typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses

The typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok were identified. There were two main parts. Firstly, both the primary and secondary sources showed typical features of shophouses built in this period in terms of their physical and characteristic developments. Secondly, published and unpublished research studies illustrated the typical limitations and problems of shophouses from this period. Visual surveys of existing shophouses in Bangkok confirmed what the literature recorded and were incorporated.

2.1.1. Typical features of shophouses built in Bangkok during the 1960s and 1970s

During this period, shophouses in Thailand were mainly built in what could then be called a modern style, usually characterised by compositions of simple forms and spaces. Scholars in the early 1980s observed that the simple design and construction of most shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s was aimed at reducing the cost but resulted in a repetitive and non-creative design, unlike those built in the 1980s onwards that started to have a greater level of variety (Tiptus and Bongsadadt, 366; Hinchiranan Citation1981, 21).

A row of shophouses from this period is normally comprised of a repetition of a 3.5–4 m wide unit with a depth of 12–16 m and a height of 2–5 stories (Chantavilasvong Citation1978). The height of the ground floor is usually about 3.5 m and the other floors are about 3 m. Eaves, of about 1 m long, normally cantilever from the front façade, especially on the ground floor. Shophouses are built with reinforced concrete columns and beams, the floor structure is either reinforced concrete or wood, and the walls are non-load-bearing brick masonry.

Being simple, standardised, and practical in their original plans and construction, many shophouses, however, have attractive sun-shading elements, either cast in concrete or assembled with concrete blocks, on their facades. They increase the level of privacy and shade interior spaces from the tropical sun and rain. Elaborate iron grills are always added for security. All these features are not only pragmatic, but also serve as decorative and symbolic purposes (Suwatcharapinun Citation2007, Citation2015), not unlike aggregate wash or mosaic finishes on some of the shophouses’ surfaces. These are elements that add beauty, unique characters, and creativity in the otherwise repetitive and non-creative designs. However, like other typical features, some of them entail limitations and problems to renovation of the shophouse too.

2.1.2. Typical limitations and problems of old shophouses

There are three types of typical limitations and problems of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s. The first type is those created by their original features. Some features were not problematic when the shophouses were first built, but became issues once the use of them or their surroundings changed through time. The second is those usually found in existing shophouses that have undergone alterations over time, while the third are those likely to be found during a plan or a process of renovation of existing shophouses.

Accordingly, this study summarized and categorized the typical limitations and problems into the four main issues covering the (i) space and form, (ii) climate, (iii) wellbeing, and (iv) construction.

2.2. Criteria for renovation design strategies

Responding to the four defined main issues (space and form, climate, wellbeing, and construction), a set of criteria for the design strategies was determined. The criteria were then developed for exploring and evaluating precedent designs and to design a new common prototype.

The criteria were categorized into three parts. First, the design criteria dealt with issues directly related to both the existing and proposed features of the shophouses to be renovated. Second, the procedural criteria dealt with the processes of renovation, ranging from project initiation to construction. This is necessary because the research aimed to find design ideas that could potentially be easily adopted and applied by the masses. Third, to ensure that both the design and procedure engaged with current laws and regulations, legal criteria were set out.

2.2.1. Design criteria

2.2.1.1. Space and form

In terms of space, there are five main points. The first is more usable space should be created. More usable space does not always need to be floor area, but can be a way to use the space more effectively and/or flexibly. Second is that the possibility of creating separate, and in some cases, private, spaces should be considered. Like the need for more usable space, they could be created as temporary spaces too. Third, a parking space should be provided. The fourth and fifth points are about the location and character of the architectural elements. For the interior, the relocation of stairs typically at the rear-bay of each unit of the shophouse should be reconsidered to increase the possibilities of new space organizations. For the exterior, a unique yet united character in the design of a whole row of shophouses should be created. This responds to the criticisms of their non-creative character. At the same time, it responds to the current situation of uncontrolled alterations of old shophouses, making them lacking unity and becoming eyesores.

2.2.1.2. Climate

Criteria about the climate deal with the four points of daylight, rain, air, and heat. First, adequate daylight should be provided in the interior space. Second, the different levels between the street and the ground floor should be assessed to prevent flood. Rainwater from the roof and eaves of shophouses should not be drained onto the footpath or street in front of the building. Surfaces of the rooftop should be treated to prevent leakage. Third, cool air leakage from interior spaces (especially from air-conditioning system) should be minimized and natural ventilation should be maximized. Fourth, heat gain from the rooftop and façade should be minimized.

2.2.1.3. Wellbeing

Criteria about wellbeing were categorized into the two parts of pre-occupancy and post-occupancy. For the pre-occupancy parts, which is the design and construction stages, any modification of all building systems should take the age, the typical features and limitations, and the deterioration of the existing structure(s) into account.

For post-occupancy parts, prevention of pests and pollution, such as noise, vibration, odor, and water, including the possibility from other units and the surrounding, should be considered. Outdoor and green space should be provided, whilst garbage management should be considered. Designs that entail excessive consumption of energy should be avoided. Fire exits and stairs should be provided and burglary should be also prevented by design.

2.2.1.4. Structure and construction

As far as renovation is concerned, the criteria about the structure and construction were two-fold. Firstly, the deterioration of existing structure(s) should be inspected. Illegal and risky modifications of the existing building should be examined in the renovation plan. Secondly, new elements should not add load onto the existing structure more than what it should be. The current laws and regulations provide a guidance for what the load should be.

2.2.2. Procedural criteria

Apart from the design criteria, the criteria regarding the renovation procedure were also set up. Like other architectural and construction projects, the conventional procedure of building renovation consists of the four main stages of pre-design, design, pre-construction, and construction (The Architect’s Manual Citation2004, 93–96).

Analysis of the renovation procedure showed that the cost and time entailed by the involvement of architectural and engineering professions, application for building permission, and using a building contractor for the construction constituted a certain proportion of the budget and total time to be spent for the renovation (Thai Appraisal & Estate Agents Foundation Citation2019; Ministerial Regulation Fees for Design and Construction Supervisions Citation2018; Building Control Act BE Citation2522 1979, Section 25 and 27). Even though all these involvements ensure convenience, aesthetic and functional qualities, and the public safety and orderliness of the city, they may not fit the thoughts and conditions of all the people who may be interested in renovating a shophouse.

In terms of cost, the fact that 10–20% of the total budget is to be paid for design and contractor’s fees may exceed some project owners’ expectation, the criteria for design strategies to make the renovation easier to be adopted and adapted by the masses must consider the minimum involvement of architects, engineers, and contractors.

In case of the potential exclusion of architects and engineers, there is a legal limitation. Shophouses that can be legally renovated without the involvement of an architect are those that have been used and are still to be used for only residential purposes with a maximum floor area of 150 m2. Regarding typical uses and features of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s, the former point can be possible in many shophouses, where they are used only as houses, while the latter is an issue because the total floor area of a two-to-three-story shophouses may exceed 150 m2 (see “Ministerial Regulation Defining the Controlled Architectural Profession BE Citation2549” 2006 for the limits of use and the maximum area of 150 sq.m.; “Ministerial Regulations Defining the Controlled Engineering Professions BE Citation2550” 2007 for the limit of floors and the dimensions of structure). This needs to be considered in terms of the legal counting of “floors”. Possible questions include whether the mezzanine and the rooftop is a floor. According to the legal definition of a mezzanine, it is not counted as a “floor” as long as its area is not more than 40% of the room in which it is (see “Ministerial Regulations Issue 55 BE Citation2543(Following Building Control Act BE 2522)” 2000; “Bangkok Ordinance in Building Control BE Citation2544” 2001).

Shophouses that can be legally renovated without the involvement of an engineer are those with no structure of any floor higher than 4 m., no beam of any bay spanning longer than 5 m., and the shophouse should not be higher than two floors. This means that only two-story shophouses without a rooftop are counted. Shophouses of this size were rarely built during the 1960s and 1970s.

In summary, the renovation of most shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s legally needs architects and engineers to design. However, this is only applied if the renovation is legally classified as “building alteration”. If it is only “fixing”, then architects and engineers are not required by law to be involved. This issue will be elaborated in the discussion on legal criteria.

2.2.3. Legal criteria

If designs for renovation are classified by law as “fixing”, the pre-construction procedure is easier and shorter. This is because a certain level of renovation beyond “fixing” is classified as “alteration”, for which permission by the authority, to whom a set of construction drawings are submitted, is needed before the construction.

Accordingly, any renovation that is classified as fixing responds to the expectations and limitations of a great number of people who want to renovate their shophouses by avoiding possible complications, delays, and extra cost in dealing with the otherwise required drawing submission and building permission processes. For “fixing”, an application for permission is also needed but no drawings are required. In any case, the design must follow other regulations to ensure the safety of the inhabitants and the public.

Therefore, the legal evaluation of both the case studies and the designed prototype in the design exploration were based on two main legal criteria. The first is whether the designs for renovation of the shophouses fell within the allowance of the authority for not being obligated to apply for building permission. The second is whether the designs of the cases complied with the building codes for ensuring public safety. For the prototype, it was also developed according to these legal criteria.

Most law and regulations are clear and definite except the one indicating actions that are not defined as building alteration or demolition, for which application for building permission is not required (The Ministerial Regulations Issue 11 BE Citation2528 (following Building Control Act BE 2522), edited with the Ministerial regulations Issue 65 (BE 2558) 2015). An unclear part is where the regulations deal differently with “structural” and “non-structural” parts of the building. Replacement of the existing non-structural parts of the building with ones of the same material or another material, but not increasing the load on any member of the structure by more than 10% is not considered alteration. However, there is no exact definition of “structure” but only the definition of “main structure (โครงสร้างหลัก)” (in the Bangkok Ordinance in Building Control BE Citation2544 2001, Section 1 (vocabulary), the main structure means “building components, which are columns, beams, joists, floor, or steel frames spanning more than 15 m, that are important for the stability of the building”). This mean interpretation of the law may be needed and it could create a complication.

By law, it is finally up to the authority how to interpret. The parts that are likely to be complicated are walls. Typical shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s have a reinforced concrete skeleton structure. This means that columns and beams bear and transfer main loads, and so they are main structures. On the other hand, walls, typically half-brick masonry, are definitely not a “main structure” since they are not load bearing. However, there is no clear definition whether they are a structure or not.

If walls are non-structural, they can be replaced with ones of the same material or another material, as long as they do not increase the load on the beam on which it stands by more than 10%. If they are considered structural, they can only be replaced with the same amount and type of material, and they cannot be replaced by other materials or just demolished.

In the evaluation of case studies and the prototype of this research, walls were considered as non-structural parts, to ensure all possibilities in the exploration of design strategies in response to typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses. In the discussion for establishing strategies and a renovation prototype, this research, however, took these complicated scenarios into account.

In conclusion, the renovation should be done within the level not considered alteration. Wherever law and regulations are not clear, the renovation should adhere to the essential purposes of design and law that ensured a certain level of functional and aesthetic standard, and public safety, while minimizing or avoiding the involvement of architects, engineers, contractor, and the local authority.

2.3. Design explorations

In this stage, design responses to the issues were explored and evaluated based on the criteria in the three aspects of design, procedure, and law. The explored designs were divided into three categories. The first was comprised of the design suggestions from research studies focusing on the issues of old shophouses. The second was comprised of real cases, including built-projects of shophouse renovation and a platform facilitating the public to renovate wooden apartment buildings in Japan. The last was the design and construction of a prototype. All case studies were analyzed in a structured observation in relation to the already set criteria. The explorations and evaluations of all three categories provided materials for the discussion and the creation of a guideline.

2.3.1. Design ideas from the literature

By examining the issues and problems of old shophouses, many recent studies (Oamthaveepoonsaup Citation1998; Payuckchart Citation2002; Boonyachut and Tirapas Citation2011; Lay Citation2013; Songbundit Citation2015) have suggested their improvements through renovation. Most of these studies have been focused on issues based on the authors’ research interests, but each of them did not necessarily cover all the four groups of issues categorised in this research; namely (i) space and form, (ii) climate, (iii) wellbeing, and (iv) construction and structure, although altogether they did. This research categorised their suggestions into the two main groups of (i) the improvements of features on the enclosures and the spaces adjacent to them (Oamthaveepoonsaup Citation1998; Payuckchart Citation2002) and (ii) both the enclosure and interior space and planning (Boonyachut and Tirapas Citation2011; Lay Citation2013; Songbundit Citation2015).

Some of the previous suggestions, such as adding fire escape stairs, unifying the designs of front façades, and adding security grills, could be adopted and adapted in most shophouse renovations. However, many of the previous ideas, such as changing the positions of stairs and creating wind tunnels by demolition of some floor plates could not be done without application for building permission. Some additions of shading features or alterations of openings and non-structural walls on both facades might be done without building permission, depending on whether the local officials defined the specific walls as a structure.

In any case, the choices of their materials and construction methods needed to be carefully selected so as to ensure minimum effects to the structure of adjacent units and disturbances to neighbours. All these ideas were explored in more detail in the case studies of real projects.

2.3.2. Design case studies

Unlike cases from research studies with particular focuses, the use of real cases of built projects allowed this research to explore and evaluate their design responses in detail regarding all the issues. They were also evaluated according to procedural and legal criteria. This added more materials to what which had been gathered from previous cases in research studies for the design and construction of the prototype. Two cases of shophouse renovation were aTypical Shophouse by thingsmatter, and The Headquarters by all(zone).

Another case study was not a shophouse renovation, but was selected with a focus on the procedural aspect so as to achieve the mass adoption and application of renovation. It explored the work of the social enterprise MOKU-CHIN KIKAKU that promoted the renovation of wooden apartments in Japan by creating a platform to facilitate the general public to easily renovate their buildings through an open-source design tool. However, some design ideas for the renovation of wooden apartments could also be applied to those responding to shophouses’ typical features, limitations, and problems.

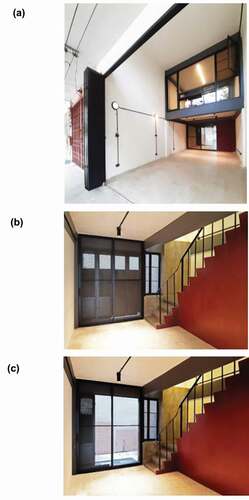

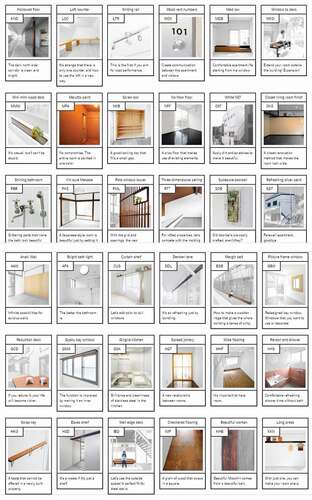

Images showing key features and spaces of “aTypical Shophouse” by thingsmatter and Allzone’s headquarters are shown in respectively. A sample of MOKU-CHIN KIKAKU’s catalogue is shown in .

Figure 5. A view showing the main feature on the front façade of all(zone)’s The Headquarters. It is a double-layered façade comprising a full-height transparent folding doors on the internal layer and steel-framed concrete blocks on the external layer. This outstanding feature ensures visual transparency, intrusion of natural light and ventilation, while filtering strong sun and preventing burglary

Figure 6. Sample of MOKU-CHIN RECIPE. Features in this open-source catalogue aim at improving Japan’s old wooden apartments’ spatial utility, aesthetics, comfort, and hygiene

A summary of and comments on all design ideas responding to typical limitations and problems of old shophouses derived from all three case studies is categorized according to criteria as follows:

Space and form

In terms of use, cases responded to issues of privacy and inefficient floor planning because of the original locations of stairs by keeping most existing stairs but separating them and corridors from main spaces. An addition of stairs from the ground floor to the mezzanine, and the demolition of some concrete stairs appeared in some cases but these have legal limitations as they required building permission.

The issue of privacy also lead to the need for separate rooms. The cases applied large doors, sliding doors, or even curtains, as partitions to create private spaces that were still flexible. Light walls were used for some partitions not needing flexibility in daily use but still more flexible than masonry walls to be altered or demolished in the future.

Privacy from surroundings were increased by an additional layer of features, such as concrete blocks and timber slats, on the periphery. These also needed to be considered in terms of added load allowed by law.

In terms of aesthetic and atmosphere, all cases promoted simplicity in their overall designs. They, however, applied both similar and different designs to achieve simplicity. Taking the designs of party walls shared with adjacent houses for example. Most cases chose to carefully line electrical conduit pipes on them without hiding them in the walls because cutting existing wall to line the conduit pipes might affect the wall surfaces of the adjacent house. Double partitions were, however, applied at some party walls in some cases to hide electrical pipes to ensure more neatness and simplicity of plain walls.

However, when it came to the issue of orderliness of a row of shophouses, cases did not take this into account. They demolished existing balconies to enlarge openings. An additional layer of the façade described earlier to offer better use for interior space also made the case outstanding from the rest of the houses in the row. This did not promote unity and orderliness of the whole row of shophouses.

Climate

For visual comfort and thermal comfort, cases tried to deal with them by increasing open space and adjusting façades. Increasing open space was done by demolishing the existing-but-illegal extension of building on the designated open space at the back of the building, and demolishing parts of the existing addition of interior space on the roof top.

Adjusted façades of the cases tried to balance efficient intrusion of natural light and ventilation through new full-height openings and sufficient filtering of strong sun by concrete block screens. These features needed to be considered in relation to law and regulations about whether existing walls could be demolished, and new features could be added on the façade without building permission.

Wellbeing

Most design features discussed in the first two categories also enhanced wellbeing. Additional findings in the cases were appropriate zoning of spaces according to their functions and surroundings. And additional fire exits and stairs were added.

Construction and structure

Considering minimum alteration of old structure (as long as it was safe and sound), locations of toilets and shower rooms in the cases were at the rear-bay, so they sent out and lined new plumbing system on the rear-façade directly, avoiding the need to cut existing concrete floors. The maintenance of them in the future was also easier than hiding them in walls or above ceilings. Types of structural and finishing materials in the cases were kept minimum or readily provided in catalogues to ensure simplicity and reduce customization. This could be considered and developed further in relation to procedural criteria to find possibility to minimize the roles of architects and maximize accessibility and affordability of shophouse renovation.

Similar and different design ideas from different cases responding to categorized issues were analyzed. These were selected and developed more in the design and construction processes of the prototype. Furthermore, the prototype design also addressed some issues not clearly evaluated in any previous case, such as the location of kitchen, and the boxy space of typical shophouses. Many issues from procedural and legal criteria, such as the definition of walls and the roles of the architect and engineer, not clearly responded by the cases were explored more in the prototype.

2.3.3. Prototype design

After setting the criteria and exploring and evaluating the case studies, a prototype shophouse renovation aiming to be easily adopted and adapted by the public was designed and constructed in order to test selected design ideas. The old shophouse selected to be renovated had typical features found in typical shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok (). Therefore, there were almost all of the typical problems and issues that needed to be responded to.

Figure 8. Photos of the existing condition of the building selected for the prototype renovation

There were also extra issues observed in the existing building that had not been raised by previous research studies and selected cases before. The typically long-and-narrow spaces of shophouses, created by the fact that most shophouses’ floor plans have parallel opaque walls with an opening only at both ends, not only limited the ventilation and the penetration of natural light, as critiqued by most research and design cases, but also limited the spatial perception of the inhabitants as if they lived in a box. This type of space was what Bruno Zevi criticized in the designs of what he called “pseudo-modernist” buildings. Instead of trapping users in a box, Zevi argued for the opening of the box by eliminating frames and perpendicularity, liberating the perception of users. He wanted the space to be lighter and to look airier and more spacious ().

The design process started with the selection of design ideas from the case studies and applying them to fit the existing conditions of the selected building and to be tested. The selected design ideas met the procedural and legal criteria to ensure the possibility to be easily adopted and applied by the public. Accordingly, design ideas within the legal limit of renovation without the need to apply for building permission were prioritized, or, if building permission was needed, the designs should follow the relevant local laws and regulations.

Other design ideas were also proposed, responding to the extra issues observed in the real building. Accordingly, the design directions were set according to the category of issues and were discussed as follows:

Space and form

Opening up spaces both physically and perceptually to break the typically boxy spaces of shophouses by applying open plan, transparent sliding doors as partitions, and painting columns, beams, walls and ceiling as a loose composition of separate lines and planes

Separating corridors and staircases from main spaces

Keep the existing staircase

Using light walls instead of masonry walls in appropriate places

Promoting the unity of street facades by maintaining the original concrete shading elements

Demolishing the illegal extension of a roof onto the open space at the back of the house, creating instead a kind of courtyard

Climate

Applying open plan and full-height transparent sliding doors also helped increasing comfort by allowing more ventilation while creating a double façade by maintaining original concrete shading elements protecting interior space from excessive sunlight and heat

Wellbeing

Applying open plan and transparent sliding doors that helped increasing ventilation and reasonably amount of natural light also helped increasing the hygiene

Opening up spaces towards green space (a nice garden of a neighbor on the opposite side) and bringing it in (recessing the location of the transparent sliding doors on the front façade to create a balcony able to locate plant pots, while being aware of pollution, such as noise and dust (trees in plant pots helped minimizing these).

Relocating and redesigning toilets and shower rooms at the rear-bay to be brighter and better-ventilated

Ensuring the presence of fire escapes at the front façade

Construction and structure

Locating toilets and shower rooms at the rear-bay also sent out and lined new plumbing system on the rear-façade directly, avoiding the need to cut existing concrete floors.

Simplifying the alterations and/or additions of structure and building systems, such as plumbing and electricity, to avoid both structural and maintenance problems, and to minimize the cost.

Limiting the types of materials and construction methods and suppliers to be as low as possible to shorten the time for cooperation between the contractors and suppliers, or to allow the architect or owner to deal with builders and suppliers themselves without a contractor.

Preliminary designs and schematic designs were first developed. Then, the design development stage finalized construction drawings and specifications. For the pre-construction stage, bidding was arranged. The main challenge for the renovation of a shophouse with a limited budget in Bangkok is that contractors who were willing to bid for the job were petty contractors, because this level of budget hardly attracts professional contractors with a systematic protocol of work and established background. In the case of this prototype, a professional contractor turned down the invitation for bidding. Instead, they recommended a petty builder who had had prior experience of renovating a shophouse. The design was finally edited a bit more to reduce the cost. The main space of the ground floor became a garage, and the entrance hall was at the last bay of the floor.

In addition, the plan of the third floor was changed to be the same as the second floor, and so the bathroom on the top floor was moved to be a smaller shower room on the third floor making the room on the top floor became a multipurpose room. The builder was finally contracted for the main work, including the electrical work, but excluding the aluminum frame openings and security grill work.

The aluminum frame openings and security grill work were excluded because the researcher saw these as dry work, which was normally subcontracted by contractors to specialists. Accordingly, the researcher separated them to minimize the contractor’s overhead charge and saw if it was convenient enough to be arranged by the project owner. The final edited plans are shown in .

2.3.4. Prototype construction

The next stage was the construction. Overall, the construction went well without critical problems, including no nuisance or damages to neighbors and adjacent buildings and no visit from a district officer. During the construction, many design strategies were realized and tested. Most design features perfectly met expectations. Some, however, did not fulfill expected outcomes and, therefore, lead to to some revisions.

After dismantling the existing windows on the front façade and maintaining the walls under them, the researcher observed that the penetration of natural light was still not satisfactory. Furthermore, the good view of the green garden of the opposite house deserved to be seen more. Therefore, it was decided to demolish the walls and so the security grills became a full-height sliding doors. The concrete arch screens were, however, maintained, as originally planned.

A disadvantage of separating the security grill work and that the design finally went for a full-height security grills in the form of sliding doors with extended metal sheet panels was that security grill builder created scratches on the finishing of the floor constructed by the main contractor. This affected the schedule and scope of work of the main contractor because they had to fix the scratches.

A major problem really happened when the electrical work was commenced. The contractor subcontracted the work to an electrician. The subcontracted electrician did not seem to be capable of lining conduit pipes delicately and orderly. The work went slowly and was delayed. The electrician ran away. The builder could not find a substitute. The contractor finally went missing.

The researcher found a new electrician to complete the work. At the same time, the aluminum frame builder commenced the work. Both works were finally finished. The last but major problem was that there were no builders to fix all defects because this was normally the job of the main contractor. The researcher finally hired another set of builders to finish the work.

The lessons learned from the implementation and realization of design strategies in the prototype proofed that procedural and legal aspects were as important as the design one. While most of design features met expected outcomes, the size of openings at the front façade was adjusted for a better response to real lighting conditions and views. This happened to involve the unclear definition of whether walls were structure or not, because the original walls on the front façade needed to be demolished. There would be no problem if the district officer interpreted wall as non-structure. It would be more complicated if he or she interpreted otherwise. This would in turn return to the question of how the front façade may be designed in the first place to avoid possible complication due to building permission.

The real construction of the prototype also revealed the challenge for construction without a contractor. No matter how ordered and careful the different types of work by different kinds of builders were arranged, it was unlikely to be able to avoid defect or damages of some works caused by others. The problem of who would clear these defects emphasized the convenience of having a contractor. Alternatively, builders to clear all the defects should be hired separately at the last stage, similar to what eventually happened in this prototype project. In this case, the total cost should be compared to that which would have to be paid to one main contractor. Following photos of complete work in show how design strategies were realized and how design features improved the existing shophouse and fulfilled requirements, as categorically set in chapter 2.3.3.

3. Design strategies for the renovation of old shophouses, built in Bangkok during the 1960s and 1970s, suitable for mass adoption and adaptation

Lessons from the case studies and the design and construction of the prototype were distilled to create a set of general design strategies for the renovation of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s. In reality, applications of these strategies are not limited to shophouses only built during the 1960s and 1970s. The fact that many shophouses only built slightly earlier or later than this period also share typical features allows these design strategies to be used for a wider range of shophouses.

This is why the first thing to do is to check the features of the shophouse to be renovated. If its overall features are the same as typical features of old shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok, as discussed in this research, these designs should be able to be applied. The strategies are organized as follows:

3.1. Lay out

The land plot on which a shophouse is originally located had open spaces at the back and, in many cases, in front of the house. This is because of the set-back law, requiring a 2–3 metre-wide open space at the back of a shophouse. In most cases, a later extension of the building occupies this space, but this is an illegal extension. If building permission is to be applied before renovation, the design should include demolition of this part.

However, to avoid possible complication in the application of building permission, it is better to renovate it within the limit of law not requiring building permission. In general, this means that it is better to leave the extension part as it is, because the demolition of it needs an application for building permission. The roof structure can, however, be changed if it is a wooden structure. It should be changed to new members of the same size and made from wood. However, if it is constructed from reinforced concrete or steel, it cannot be changed without building permission. Only the fixing of the deteriorated part is allowed.

The roofing material can be changed as long as the new one does not increase the load onto the structure by more than 10% compared to the old one. This can be checked from the load/m2 values of roofing materials. However, the type, size, and interval between purlins also needs to be considered. The new material needs to be installed on the existing type and size of purlins with the existing intervals. Basically, there should be no problem if the roofing material is the same type as the old one.

A lighter roofing material that fits the existing structure is also an alternative. Typically, the existing roofing material of the extension part is fiber-cement tiles. Therefore, new fiber-cement tiles can be used for the replacement. In many cases, they are better changed to new ones as existing ones, produced decades earlier may contain asbestos, which is harmful to health. Alternatively, metal sheets can typically be installed on existing roof structures previously roofed with fiber-cement tiles. The ceiling and finishing of the floor and walls of this part can be redone. Their designs depend on the project owner and how the space will be used.

3.2. Plans

Within the scope of this research, strategies for planning are based on three scenarios of programing. First, the whole shophouse is used for residential purposes. Second, the whole shophouse is used for commercial purposes. Third, the shophouse is of a mixed-use between residential and commercial purposes.

For the first scenario, the ground floor is recommended to be a garage and entrance hall. Residential units are on upper floors. For the second scenario, commercial programs that typically require a street front, such as shops and café, can be located on the ground floor. Upper floors are suitable to be office spaces. In the case where only upper floors are to be used for office space, the ground floor can be a garage and entrance hall. For the third scenario of mixed-use, there are many possibilities. Therefore, this research suggests a flexible planning principle to be adopted and applied to suit any programing in all three scenarios. Examples of possible plans from the guideline are shown in .

3.3. Structure

The main structures, which are reinforced concrete columns, beams, floors, and all underground structures, should only be evaluated and fixed, if needed, but not altered. A roof structure made from concrete or steel should be treated the same way. These are to avoid both possible damages to the existing structure and adjacent buildings, and possible complications in obtaining building permission. By not altering any structures, building permission is not required.

Figure 14. Possible street elevation of a row of shophouses in Bangkok once the owners have adopted and applied a design guideline for the improvement of modern shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s according to their own needs while conforming to regulations and achieving a certain level of unity in design, thanks to the maintenance of the original concrete screens

3.4. Enclosures

There are five sides of enclosures. Two sides are party walls and these should be maintained. Light walls may be added onto them for better insulation and acoustics. Exterior enclosures are the roof and facades on both sides. Roofing materials can be changed with the same type of the original materials or a new type that increases the load onto the structure by no more than 10%.

For the front and rear facades, this research takes account of how the laws define structures. As it is not clearly defined if a brick wall, which is a typical feature of the front and back facades of shophouses, is a structure, complications can occur according to different interpretations by different officials from different districts.

In order to avoid any complication, it is recommended to maintain brick walls on the front façade. Windows and doors can be either changed to new types or taken away because they are definitely not a structure. In the case of taking away existing doors and windows on the front façade, a new set of full-height-and-full-span sliding doors can be installed with about a meter offset from the brick wall. This creates a balcony where tree pots can be placed to create a green space at the periphery of the interior space, and to open up the boxy space.

A similar principle can be applied to the rear-façade. The choice to create a balcony with new sliding doors offset from the original wall can be done at one half of the back façade where the supporting space, such as toilet and shower room, is located. It cannot be done on the stairs side. Alternatively, all existing walls and windows may be completely demolished and redesigned in a way promoting better ventilation and natural light. Possible complications regarding interpretation of district officers may not happen as long as the construction of this part is properly done and creates no damage and nuisance to neighbors.

3.5. Materials and construction

The choice of materials should be as limited as possible, and acquiring, transporting, and construction or installation of them should be as simple and quick as possible.

The use of materials requiring wet construction for floor and walls finishing, such as tiles should be minimized. If the existing floor finishings are still in good condition and desirable, they can be cleaned and used. For example, many old shophouses have old style but attractive terrazzo floors. However, where a new floor finishing is needed, resurfacing of the existing floor after dismantling the old finishing is likely to be required. Light materials requiring quick installation, such as vinyl tiles and laminated floor planks, are desirable. Tile flooring may be used in toilets and shower rooms. Instead of suppressing the floor, a curb can be created at the door entering a toilet or shower room to prevent water flowing out into an adjacent space. This does not affect the old structure.

Brick walls can be minimized to only external walls and walls of toilets and shower rooms to be durable and water resistant. Light walls constructed with wood or galvanised steel frames can be used in dry areas. They can also be installed with insulation infills on some parts of existing party walls to minimize heat transfer and enhance acoustic qualities. Most partitions should use aluminum or PVC frames with various kinds of openings, such as doors, sliding doors, folding doors, and louvres, and transparent or translucent panels to promote a visual flow of space, natural light, and ventilation. New openings on facades can also be constructed with the same materials as the interior partitions.

3.6. Building systems

All new building systems are normally required in the renovation, mainly according to the changes in planning. The simple planning suggested above simplifies the installation of building systems.

For electricity, orderly lining of exposed conduit pipes on walls and on the surfaces of floors overhead is suitable for most spaces because they do not have ceilings. Some pipes can be hidden behind light walls when plain walls are needed. The main conduit pipe from the front of the house can be lined along the wall of the ground floor on the opposite side of the stairs. Separate meters for each unit can be installed at the entrance hall at the rear-bay. A vertical shaft should be created to lead conduit pipes to upper floors.

For the sanitary system, all pipes should be lined on the exterior wall of the rear-façade at the position of the stairs landing. The water tank, booster pump, and septic tank should be at that position. Pipes are vertically lined up along all floors. On each floor, they are horizontally lined on the wall to the location of toilet and shower rooms on the other side.

On each floor, a cool water pipe is lined on the party wall supplying water to all sanitary wares and continues along the wall to supply water for the wash basin in the adjacent kitchen. Also on each floor, waste water from the wash basin in the kitchen and the toilet run along the same wall and go out to the façade, continue running horizontally with a sufficient slope to join with the vertical ones. Wastewater from the shower box goes out at a scupper drain on the wall, instead of using a normal floor drain that requires a cut through the existing concrete floor. Similarly, the soil pipe from the toilet on each floor goes out directly to the outside to avoid cutting the existing floor. The toilet to be used must be of this type. All wastewater and soil pipes must go through a p-trap right after going outside.

3.7. Security and fire safety

If a cctv or sensor system is not installed, security grills typically used in old shophouses can be applied on the outer edge of the façade, i. e. void on shading screens, if any. The important point is that a fire escape door or window of a legal size should be included in the grills on each floor. Fire escape stairs in a form of ladders can be designed as an integral part of the security grills.

4. Conclusion

In the big picture, the origin of this research started from questions about how we want to live and work in a city. What kinds of housing are available for us to choose from? Where are they? How many kinds of relationship between life and work were there? Were there only choices between living in a small apartment in the city center to reduce commuting time to work and living in a larger house outside the city but spending more time in commuting? With all these questions, the research focused on the shophouse, a building type in Bangkok, as a case study.

This research hypothesized that most of the existing shophouses could be adaptively used to suit the contemporary requirements and conditions of Bangkok residents. They need to be renovated before their new use. Creative designs of shophouse renovation have been performed and published recently, but they are still minor in number compared with existing shophouses in Bangkok. The greater the number of renovated shophouses, the more impact they could contribute to the wellbeing of Bangkok residents and potentially exemplify how building renovation could contribute to sustainability.

Accordingly, this research explored and established a set of design guides for shophouse renovation that could easily be adopted and applied by the public. It suggested that shophouse renovation should mainly solve the issues about space, climate, wellbeing, and construction in a simple way. It proposed that space organization should be simple and flexible. It argued for a limitation of the types of materials and simplification of the arrangements of building systems. Most importantly, it suggested that all of these should be designed in a way that application for building permission is not needed. However, case studies showed that some parts of the renovation design could not help involving with the unclarity of the law and the possibility of facing a too-rigid-interpretation of an official. This situation raised the question whether certain laws need to be reconsidered and revised.

One more important aspect of the design guideline was that the renovation should minimize the roles of architects and engineers to make renovation more affordable. Accordingly, the guideline proposed a reasonably good design options that met safety standards and promote wellbeing. By doing so, this research did not undermine the intellectual and creative positions of the professionals. However, the research revealed that the number of design options of shophouse renovation of a certain architectural quality within the scope of construction unclassified as building alteration were limited. Despite variety, options of space organization would not much exceed what have been provided in the above guideline.

If a project owner could access the guideline provided in this paper, he/she would have a certain ability to deal with petty contractor, or builders, and construction material suppliers to realize it. However, according to the lessons learned from executing the prototype, the architect and engineer’s involvement could be minimal, but could be crucial in dealing with issues on site unexpected in the design. It should be most beneficial for the mass shophouse renovation and everyone if the professionals could come up with a type of profession services that fit this situation. For example, an architect and an engineer involve mainly during the construction stage, or contractors, builders, and suppliers have an architect and/or an engineer in their teams.

The lessons learned about unclear regulations and possibly minimal involvement of the professionals implied that shophouse renovation could be more widespread if the authority sees its benefit for the society and willing to support it by revising regulations rather than only control it, and if the professionals have visions about how to contribute to it beyond conventional professional services.

Architects and engineers, however, still have chances to design shophouse renovation with special design intentions or unique characters within the conventional scope of their services. There are also a lot more topics related to shophouse renovation for architects and researchers to explore. Examples of them are prefabricated and green renovation of old shophouses, renovation of old shophouses for the aging society, social housing, and urban regeneration, and mobile application for the renovation of old shophouses, etc.

By exploring more topics and issues related to shophouse renovation, existing shophouses will play crucial roles in the sustainable urban (re)development in the future. What have been learned from this research should be able to apply to a variety of building types with their repetitive designs and abundant numbers in Asian and global contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chomchon Fusinpaiboon

Chomchon Fusinpaiboon, Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Architecture, Chulalongkorn University, and a practicing architect. His research interests cover modern and contemporary architecture in Asia. His doctoral dissertation examines how a modern architectural culture was established in Thailand, and how it transformed traditional ideas of architecture and vice versa. His ongoing design research focuses on the shophouse, a non-pedigree modern architecture that played a major role in the urbanisation of Thailand during the 1960s and 1970s, questioning its legacy and its future in relation to contemporary architectural practice and urban issues. His published works include studies on unconventional works of Thai architect Prince Vodhyakara Varavarn, who reinterpreted English Arts and Crafts philosophy to adapt to modern Thai architecture of both prewar and postwar periods, and the establishment of Thailand’s first architecture school that involved nationalism, a Belgian architect and Chinese migrants.

References

- all(zone). 2009. “The Headquarters.” Accessed 31 July 2021. http://www.allzonedesignall.com/project/architecture/the-headquaters/

- Al-Obaidi, K. M., S. L. Wei, M. A. Ismail, and K. J. Kam. 2017. “Sustainable Building Assessment of Colonial Shophouses after Adaptive Reuse in Kuala Lumpur.” Buildings 7 (4): 87. doi:10.3390/buildings7040087.

- Aranha, J. 2013. “The Southeast Asian Shophouse as a Model for Sustainable Urban Environments.” International Journal of Design and Nature and Ecodynamics 8 (4): 325–335. doi:10.2495/DNE-V8-N4-325-335.

- Architect’s Manual (คู่มือสถาปนิก 2547). 2004. Bangkok: Association of Siamese Architects under the Royal Patronage.

- “Bangkok Ordinance in Building Control BE 2544 (ข้อบัญญัติกรุงเทพมหานคร เรื่อง ควบคุมอาคาร พ.ศ. 2544).” 2001.

- Bongsadadt, M. 1981. “Advantages of Shophouses (ข้อได้เปรียบของตึกแถว).” In Problems of Shophouses (ปัญหาตึกแถว), 33–37. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

- Boonyachut, S., and C. Tirapas. 2011. “Shophouse: Quality of Living and Improvement.” Journal of the National Research Council of Thailand 43 (2): 13–32.

- “Building Control Act BE 2522 (พระราชบัญญัติควบคุมอาคาร พ.ศ.2522).” 1979.

- Chantavilasvong, S. 1978. “A Study of Some Aspects of Shop-House Architecture (ความเข้าใจบางประการจาก การศึกษาสถาปัตยกรรม “ห้องแถว”).” MArch diss., Chulalongkorn University.

- Chulasai, B. 2007. “Shophouses: The Living Testimony of Urban Transformation in Thailand.” Paper presented at the International Conference on the Evolution and Rehabilitation of the Asian Shophouse, Hong Kong, May 10- 12.

- Fusinpaiboon, C. 2020. “Thailand’s Shophouses: A People’s History and Their Future.” In The Impossibility of Mapping (Urban Asia), edited by Bauer, Ute Meta, Puay Khim Ong, and Roger Nelson 120–137. Singapore: NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore and World Scientific Publishing.

- Hinchiranan, N. 1981. “Shophouses at the Present (ตึกแถวในปัจจุบัน).” In Problems of Shophouses (ปัญหาตึกแถว, 21–23. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

- Kubota, T., D. H. C. Toe, and D. R. Ossen. 2014. “Field Investigation of Indoor Thermal Environments in Traditional Chinese Shophouses with Courtyards in Malacca.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 13 (1): 247–254. doi:10.3130/jaabe.13.247.

- Lay, N. 2013. “The Use of Wind-Catcher Technique to Improve Natural Air Movement in Row-Houses (การใช้เทคนิคท่อดักลมเพื่อเพิ่มการเคลื่อนไหวของอากาศในตึกแถว).” MArch diss., Chulalongkorn University.

- Li, T. L. 2007. “A Study of Ethnic Influence on the Facades of Colonial Shophouses in Singapore: A Case Study of Telok Ayer in Chinatown.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 6 (1): 41–48. doi:10.3130/jaabe.6.41.

- Lim, J. S. H. 1993. “The ‘Shophouse Rafflesia’: An Outline of Its Malaysian Pedigree and Its Subsequent Diffusion in Asia.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 66 (1 (264)): 47–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41486189

- “Ministerial Regulations Issue 55 BE 2543 (following Building Control Act BE 2522) [กฎกระทรวง ฉบับที 55 พ.ศ.2543 (ออกตามความในพระราชบัญญัติควบคุมอาคาร พ.ศ.2522)].” 2000.

- “Ministerial Regulation Defining the Controlled Architectural Profession BE 2549 (กฎกระทรวง กำหนดวิชาชีพ สถาปัตยกรรมควบคุม พ.ศ.2549).” 2006.

- “Ministerial Regulations Defining the Controlled Engineering Professions BE 2550 (กฎกระทรวงกำหนดวิชาชีพ วิศวกรรมควบคุม พ.ศ.2550).” 2007.

- “Ministerial Regulations Issue 11 BE 2528 (following Building Control Act BE 2522), edited with the Ministerial regulations Issue 65 (BE 2558) [กฎกระทรวง ฉบับที 11 พ.ศ.2528 (ออกตามความในพระราชบัญญัติควบคุมอาคาร พ.ศ.2522) แก้ไขด้วยกฎกระทรวง ฉบับที่ 65 พ.ศ. 2558].” 2015.

- “Ministerial Regulation Fees for Design and Construction Supervisions (กฎกระทรวง กำหนดอัตราค่าจ้างผู้ ให้บริการงานจ้างออกแบบหรือควบคุมงานก่อสร้าง).” 2018.

- Merlino, K. R. 2018. “Building Reuse : Sustainability, Preservation, and the Value of Design.” University of Washington Press. [Electronic Resource]. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1824320&site=eds-live

- MOKU-CHIN-KIKAKU. n.d. Accessed 31 July 2021. http://www.mokuchin.jp/

- Mosler, S. 2019. “Everyday Heritage Concept as an Approach to Place-Making Process in the Urban Landscape.” Journal of Urban Design 24 (5): 778–793. doi:10.1080/13574809.2019.1568187.

- Oamthaveepoonsaup, T. 1998. “Potential Improvement of Crown Property Bureau’s Rowhouses in Pomprabsatruphai District (แนวทางการปรับปรุงตึกแถวของสำนักงานทรัพย์สินส่วนพระมหากษัตริย์ในเขตป้อม ปราบศัตรูพ่าย).” MArch diss., Chulalongkorn University.

- Payuckchart, T. 2002. “A Concept of Shophouse Development at Silom Road (แนวทางการปรับปรุง ตึกแถวบริเวณถนนสีลม).” Master Degree diss., King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang.

- Problems of Shophouses (ปัญหาตึกแถว). 1981. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

- Songbundit, J. 2015. “Patterns of Building Modification and Cost in Function Changing of Shophouses in Si Racha, Chonburi (รูปแบบการดัดแปลงอาคารและค่าใช้จ่ายของการเปลี่ยนแปลงการใช้งานตึกแถวในเขตเทศบาลเมืองศรีราชา จังหวัดชลบุรี).” Master Degree diss., Chulalongkorn University.

- Sternstein, L., and P. Daniell. 1976. Thailand: The Environment of Modernisation. Auckland: McGraw-Hill.

- Suthep, T., and N. Liwthanamongkhon. 1979. Shophouse Manual (คู่มือตึกแถว). Bangkok: OpenCorporates.

- Suthep, T., and N. Liwthanamongkhon. 1979. Shophouse Manual (คู่มือตึกแถว). Bangkok: OpenCorporates.

- Suwatcharapinun, S. 2007. Studies in Retrospect of the Roles of Iron Grills: The Production of the Culture of Fear in Shophouses and Detached Houses in the Urban Areas of Chiang Mai (เหล็กดัด: ผลผลิตวัฒนธรรมความ กลัวที่พบในบ้านพักอาศัยในพื้นที่เมืองเชียงใหม่). Bangkok: National Research Council of Thailand.

- Suwatcharapinun, S. 2015. “Reflection of Modernity: Re-Exploring the Role of Modern Architecture in Chiang Mai (1884-1975).” Journal of Architectural/Planning Research and Studies 12 (1): 79–102

- Tan, C. S., and K. Fujita. 2014. “Building Construction of Pre-War Shophouses in George Town Observed through a Renovation Case Study.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 13 (1): 195–202. doi:10.3130/jaabe.13.195.

- Thai Appraisal & Estate Agents Foundation. 2019. “Estimation Cost of Building Construction 2019 (ราคาประเมินค่าก่อสร้างอาคาร พ.ศ. 2562).” Accessed 31 July 2019. http://www.thaiappraisal.org/thai/value/value.php

- thingsmatter. n.d. “aTypical Shophouse.” Accessed 31 July 2021. https://thingsmatter.com

- Tiptus, P., and M. Bongsadadt. 1982. Houses in Bangkok: Characters and Changes during the Last 200 Years (1782 A.D.-1982A.D.) (บ้านในกรุงเทพฯ: รูปแบบและการเปลี่ยนแปลงในรอบ 200 ปี (พ.ศ. 2325-2525). Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

- Tohiguchi, M., and H. S. Chong. 2018. “Shophouse: Asian Urban Composite Housing.” In Planning for a Better Urban Living Environment in Asia, edited by A. G.-O. Yeh and M. K. Ng, 212–230. London: Routledge.

- Tunphibulwongs, S. 1977. “Shophouses in Bangkok’s Chinatown: Socio-Economic Analysis and Strategies for Improvements.” MSc diss., Asian Institute of Technology.

- Wakita, Y., and H. Shiraishi. 2010. “Spatial Recomposition of Shophouses in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 9 (1): 207–214. doi:10.3130/jaabe.9.207.

- Wiboonchutikula, P. 1984. “The Growth of Thailand in a Changing World Economy: Past Performance and Current Outlook.” Southeast Asian Affairs 1984 (1): 326–339. doi:10.1355/SEAA84S.

- Žegarac Leskovar, V., and M. Premrov. 2019. “Integrative Approach to Comprehensive Building Renovations.” [Electronic Resource]. Springer International Publishing. EBSCOhost,search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat05085a&AN=chu.b2254021&site=eds-live

- Zevi, B. 1978. The Modern Language of Architecture. Canberra: Australian National University Press.