ABSTRACT

In detached housing estates in the suburbs of Tokyo, increasing vacancies in inherited houses have become a problem. This study aimed to assess the risk of vacant house generation and identify risk factors through analyses focusing on parent–child discussions. A questionnaire survey of parents in Koma-Musashidai, Saitama Prefecture, and their children who lived apart regarding their future intentions of inheritance of the parents’ houses using cross and logistic regression analyses revealed that 66.5% of the parent–child pairs had had no discussion, 20.5% had different impressions of the results of the discussion, and 7.8% were at high risk of producing vacant houses. Furthermore, the analyses identified the factors associated with parents’ intention to bequeath their houses: discussions with their children, old age, high age of the house, lack of proactive measures, anxiety about renting, and stronger community attachment; and the factors associated with children’s intention to leave their parents’ houses: inadequate discussions with their parents, home ownership, and lack of relationships with neighbors. These results suggest that it could be beneficial to encourage parents and children to participate together in seminars and consult with experts before parents become older to reduce the risk of vacant houses.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Detached housing estates in Japan’s suburban areas face many challenges, among which a decreasing and aging population and an increasing number of vacant houses are serious (Koura Citation2017). In particular, many detached housing estates were developed in areas located approximately 50 km from central Tokyo in the 1960–1970s (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Citation2018). Detached housing estates in suburban areas have specific characteristics such as similar development periods, family structure, and housing specification (Watanabe et al. Citation2019), and the floor area of the houses is not too large for the middle class to purchase the houses (Suzuki, Ishiwata, and Okita Citation2008). In such monotonic detached housing estates, where the majority of residents are aged over 65 (e.g., Koma-Musashidai by Hino et al. Citation2018 and Kamigo Neopolis by; Watanabe et al. Citation2019), transfer of real estate properties might occur all at once, when residents enter long-term care facilities or pass away, and many houses may become vacant in the near future (Nozawa Citation2018). In fact, 49.0% of vacant houses in the suburbs of metropolitan areas were inherited by the owners’ children, and only 16.0% were looking for buyers or renters (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Citation2020).

In suburban areas with low housing demand, potential inheritors, usually children, do not always desire to inherit their parents’ houses because their market value is low and neither sale nor rent is possible (Suzuki and Asami Citation2019). Even when their market value is not low, children might not want to inherit them because they reside far from their houses or already have their own houses (Nishiyama Citation2018). When a parent gives his/her home to a child and the child leaves it without living or utilizing it, the house becomes vacant (Takada and Nozawa Citation2018).

This study hypothesizes that the lack of parent–child discussions enhances the risk of this vacant house generation. This risk is considered high when parents intend to bequeath their houses to their children but the children do not intend to utilize them. This study also analyzes the factors that cause parents and children to have such intentions and verifies the importance of parent–child discussions. The purpose of this study is to assess the risk of vacant house generation and identify risk factors through analyses focusing on parent–child discussions.

1.1. Literature review

The prevalence of housing vacancies has been observed worldwide (Accordino and Johnson Citation2000; Couch et al. Citation2005; Martinez-Fernandez et al. Citation2016), and several studies have attributed it to housing inheritance (Baba and Hino Citation2019; Gentili and Hoekstra Citation2019). For example, Nordvik and Gulbrandsen (Citation2009) examined the patterns of vacancies in Norway and argued that young people who inherited their parents’ homes left them vacant because of the low housing demand and their high emotional attachment to the property. A similar theoretical base applies to Mediterranean countries: Hoekstra and Vakili-Zad (Citation2011) illustrated the Spanish paradox, in which rising house prices go hand in hand with a high vacancy rate, caused by the familialism of the Mediterranean welfare; children inherit their parents’ houses and even when they are vacant, children hold them for their future needs. In China, difference in the timing of migration of residents and their gender have an impact on intergenerational transfers, accelerating the accumulation of wealth (Deng, Hoekstra, and Elsinga Citation2019, Citation2020). Such inequalities lead to an increase in housing vacancies through the discrepancy between housing prices and the income available for housing (Zhang, Jia, and Yang Citation2016).

In Japan, housing inheritance is considered to be associated with the generation of vacant houses (Nozawa Citation2018). Unlike in Western countries, where housing is regarded as a potential welfare resource, houses in Japan are not necessarily asset-based welfare but commodities that depreciate in several decades (Doling and Ronald Citation2010; Hirayama Citation2003; Izuhara Citation2016). The lifespan of residential buildings is approximately 25 years (Tanikawa and Hashimoto Citation2009), which is much shorter than that of other countries such as the United States, whose residential building lifespan is 61 years on average (Aktas and Bilec Citation2012). This short lifespan results in an increase in vacant properties due to the neglect of obsolescent housing stock (Wuyts et al. Citation2019). Moreover, Japanese do not fully recognize either the asset or use values that a house involves: parents often do not have any plan for inheritance and children sometimes do not have knowledge of asset utilization, resulting in an increase in vacant properties (Horioka Citation2014; Izuhara Citation2016).

Since inheritance is a major driver of housing vacancies, previous studies have focused on the characteristics of generation turnover in detached housing estates (Matsumura and Setoguchi Citation2014; Sakamoto, Iida, and Yokohari Citation2018). In particular, a number of studies have been conducted on parents’ attitudes toward housing inheritance. Iwata and Yukutake (Citation2020) confirmed the existence of informal financial markets in which parents may receive cash from their children for their living expenses under the condition that the children inherit the housing assets. Suzuki and Okita (Citation2005) indicate that parents do not always insist on inheritance by their children, because they respect the opinions of their children, who, in some cases, have already purchased a house.

Although parents seek to maximize the benefit to their own family, there is a certain gap between parents’ and children’s attitudes toward housing inheritance. Sonoda (Citation2010) conducted a questionnaire on housing inheritance for owners in a suburban area of Tokyo. While 75.5% of the owners wanted their children to inherit their house, only 33.7% of the children intended to reside in the house, and 35.1% did not have a clear intention. In a questionnaire conducted in a suburban residential area of Fukui City, Japan (Kikuchi and Nojima Citation2007), 37% of the parents answered that their children would not reside in the inherited house, despite housing inheritance. The above studies indicate differences in attitudes between parents and children toward housing inheritance. This study fills this research gap by tracking pairs of parents and children, and exploring the factors of such intergenerational discrepancies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Target area

The target area was the Koma-Musashidai Danchi (Koma) in Hidaka City, Saitama Prefecture (). It is a planned residential area located in the suburbs about 50 km from central Tokyo, and approximately 60 min by Seibu Ikebukuro Line from Ikebukuro Station, one of the major terminal stations in Tokyo. A private company (Tokyu Land Corporation) developed a hilly area and started selling it in 1977. According to the 2015 Census, 5,011 people and 2,097 households live there. It has a good natural environment but is less convenient: It is far from central Tokyo, and the only supermarket in the area closed in 2008 (Sekiguchi, Hino, and Ishii Citation2019).

As reported by the 1995 Census, there were two peaks in the population composition: the parent generation in their 40s and 50s and the child generation in their teens and 20s. After that, the child generation moved out of Koma, and only the parent generation in their 60s and 70s remained (Hino et al. Citation2018). According to the core members of the neighborhood association in Koma, there are currently more vacant houses whose owners have moved to their children’s houses or entered long-term care facilities than those whose owners have passed away; however, when their average age reaches the average life expectancy in a dozen years, the number of vacant houses will surely increase in proportion to the increase in inheritance due to the age similarity of the inhabitants.

The standard detached house in Koma is 40 years old, has a land area of 110 m2, and has a total floor area of 180 m2. The market price of used properties is about 8.5 million to 12 million yen, and there are about 20 transactions per year in the area.

2.2. Questionnaire survey

In September 2019, a questionnaire survey of parents residing in Koma and children who had moved out of the area was conducted. The distribution and collection procedures were as follows: (1) Envelopes containing two types of questionnaires for parents and children were distributed directly to all 2,213 Koma households. (2) The parent transferred the questionnaire for the child to the child who was most likely to inherit the parent’s home. (3) The parent responded to the form and mailed it back to us. (4) The child responded to the form and mailed it back to us. The parent and child were linked by the identification number printed in advance on the form that the parent answered and the form that was transferred to the child.

The main concern of this study is the disposition of parents’ houses in the future. The questionnaire asked parents, “What do you want to do if you can’t live in your house anymore?” The options were “give it to my child,” “sell it,” “rent it,” and “do nothing.” Children were asked, “What would you like to do if you took over your parents’ house in the future?” The options were “I will live in it,” “sell it,” “rent it,” “demolish it,” “let a sibling liv in its,” “use it as a storehouse,” “do nothing,” and “other.” This study hypothesized that a lack of parent–child discussions enhances the risk of vacant house generation. Therefore, the questionnaire asked parents (children) if they had discussed with their children (parents) what to do with their (parents’) houses in the future on a four-point scale, based on the idea that it is important for parents and children to share information about housing and their future intentions to increase the possibility of a smooth housing succession.

In addition to the above questions, parents were asked about their age, the age of the house, proactive measures, their anxiety about utilization of the house (seven items), community attachment, and their child’s address. Children were asked about their age, address, housing ownership, relationship with neighbors in Koma, years of living in Koma, and comparison with their current housing (five items).

2.3. Sample selection

Responses from 860 parents and 242 children were collected. The analysis included 406 parents, excluding those under the age of 50 or over the age of 89 (149), those without children (83), and those living with their children (222). The analysis included 192 children under the age of 30 years (22), excluding those living with their parents (28). One hundred and twenty-five pairs of parent–child responses were linked. The reasons for the exclusion by age were that parents under the age of 50 often support their children financially, children under the age of 30 are dependent on their parents, and parents over the age of 89 are often dependent on their children. The datasets of parent–child pairs were named, parents who did not live with a child, and children who did not live with a parent as PC, P, and C, respectively ().

2.4. Statistical analysis

First, this study examined the risk of a vacant house from a cross analysis of the intentions of parents and children about the inheritance of parents’ houses using Dataset PC. Another cross analysis was conducted on parent–child discussions, which form the focus of this study. Second, this study analyzed factors associated with parents’ intention to bequeath their houses to their children using a logistic regression analysis with stepwise variable selection (reference category “sell/rent”). Owing to the small size of the dataset PC, Dataset P was used. Third, the factors associated with neglecting the inherited parent’s house were identified using a polytomous logistic regression analysis with stepwise variable selection. The outcome variable has three categories: “Live,” “sell/rent/demolish,” and “neglect/storehouse,” in which “let a sibling lives” and “others” were not included. Owing to the small size of the dataset PC, Dataset C was used. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Descriptive statistics

shows the descriptive statistics of the parents’ answers. Many respondents were in their 70s (54.2%), had an attachment to the community (74.7%), and did not take proactive measures (89.2%). Most of their homes were over 30 years old (80.8%) and many felt anxious about “No buyer or renter” (58.1%) and “Cleaning up household goods” (54.7%) regarding the utilization of their house. Many of their children lived in the Tokyo metropolitan area (64.0%). Many had never discussed their homes with their children (50.2%), but had the intention to sell their homes (55.4%) or bequeath them (33.5%) in the future.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the parents’ answers.

shows the descriptive statistics of children’s answers. Many respondents were in their 40s (52.1%), lived in the Tokyo metropolitan area (50.0%), and had a dwelling (62.5%). Many respondents had lived in Koma for more than 10 years (75.5%), but almost half did not have neighborhood relationships (47.9%). Most respondents rated their parents’ homes as far less convenient for shopping (77.6%) and transportation (76.0%) than their own homes, while parents’ homes were rated higher in terms of “greenscape and landscape” and “safety and security.” Many had not discussed the homes with their parents (not at all: 27.6%, not much: 42.7%); however, the percentage of respondents who selected “somewhat/fairly (discussed)” was higher for children than for parents (28.7% and 16.1%, respectively). Regarding parents’ homes, many had the intention to sell them (41.1%) when they inherited them in the future.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the children’s answers.

Compared to Dataset P, there were fewer parents in their 60s and more in their 70s in Dataset PC. The number of respondents who have lived for 10 years or more is slightly higher in Dataset PC than in Dataset C.

3.2. Parent–child cross analyses (dataset PC)

shows the relationship between parent and child responses regarding their intentions about parents’ houses in Dataset PC. Intentions of parents and children tended to coincide: Many parents of children who had intention to live in their parents’ homes chose “inherit/leave,” and many parents of children who had intention to sell or rent chose “sell/rent.” On the other hand, pairs with a parent who had the intention of bequeathing (or leaving) the house and a child who chose “use as a storeroom/neglect” without the intention of utilizing the house accounted for 7.8% of the total. Regarding the specific answers of children grouped as “Others” of “I don’t know,” “undecided,” and “under consideration,” the risk of vacant houses might be higher, if these answers were included.

Table 3. Relationship between parent–child responses regarding their intentions about parent’s house (dataset PC).

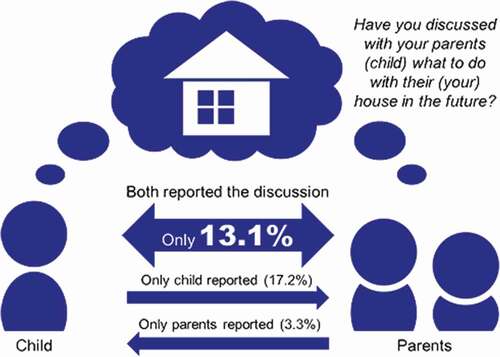

shows the relationship between parent and child responses regarding the discussions of the parents’ houses with the child or parent. Answers of parents and children tended to coincide: many parents of children who answered that they had fairly/somewhat discussed with parents chose “Somewhat/Fairly” and vice versa. Parent–child pairs, neither of whom answered that they had discussed the matter, accounted for about two-thirds (66.5%) of the total. On the other hand, in 17.2% of parent–child pairs, the child reported the discussion but the parent did not, and in 3.3% of pairs, the parent reported the discussion but the child did not. In other words, more than 20% of the pairs disagreed with their discussion.

Table 4. Relationship between parent–child responses regarding the discussions on parent’s house (dataset PC).

3.3. Logistic analysis of parents’ intention (dataset P)

shows the results of the logistic regression analysis that examined factors associated with parents’ intentions using dataset P. Parents who answered that they had discussed with their children were more likely to have the intention to bequeath their home to their children. However, as seen in dataset PC, not a few children whose parents had intention to inherit their houses also chose “neglect/storehouse.” If parent–child communication is insufficient, there is a risk that the parent’s house will become vacant. Parents in their 80s reported that they were likely to bequeath their homes, which corroborates earlier studies (Suzuki and Okita Citation2005). Owning relatively new homes (less than 30 years old) was associated with parents’ intention to bequeath them to their children. This may indicate that they built their houses with the prospect that their children would live in them in the future. Parents who took proactive measures reported that they were likely to sell or rent their houses themselves. Participation in seminars and consultations with experts may encourage the utilization of their houses. Otherwise, they might take proactive measures because they originally intended to sell or rent them.

Table 5. Result of logistic regression analysis for parents’ intention about their houses (0: sell/rent, 1: bequeath/leave).

Anxiety about responsibilities and obligations as a lessor was associated with the intention of not selling or renting the house, but, instead, of bequeathing it to their child, which may pass on responsibilities and obligations to the children. On the other hand, anxiety about the demand for their houses in the housing market was associated with the intention to sell or rent houses. This is probably because those who had such intentions conducted market research by themselves and became anxious about demand. Parents’ community attachment was positively associated with their intention to bequeath their children. The advantages of community attachment, such as encouraging participation in community activities, have been discussed in previous studies (Suzuki and Fujii Citation2008); however, regarding housing inheritance, community attachment can be a factor in parents’ imposing unwanted houses on their children. It might be beneficial to inform them that it is good for the community to consider the future of their home on their own without leaving it to the child, thereby reducing the risk of vacancy.

3.4. Polytomous logistic regression analysis of children’s intention (dataset C)

shows the results of the polytomous logistic regression analysis that examined factors associated with children’s intention using Dataset C. shows the coefficients of each category with “neglect” as the reference category. Children who had less discussion with their parents reported that they were likely to neglect their parents’ houses without renting or selling them. Parent–child discussions may reduce the risk of increasing housing vacancies. The younger age of the child was associated with his/her intention to sell or rent the parent’s home. It is hard for a child who is in the prime of life and busy with child rearing to think of moving to the suburbs, and it seems natural that he/she would sell or rent it for the income. Conversely, older age was associated with the intention to live in the parent’s house. Some children living in urban areas may want to spend the rest of their lives in the suburbs after retirement.

Table 6. Result of a polytomous logistic regression analysis for children’s intention about parents’ houses (ref: sell/rent).

Living outside the Tokyo Metropolitan area was associated with children’s intention to live in their parents’ houses and not to sell or rent them. In other words, children living in the metropolitan area reported that they were likely to rent and sell their parents’ houses because they did not need to own multiple houses. Home ownership was associated with the intention to neglect or sell or rent the parent’s home rather than to live in it. Children would not be attracted to living there to dispose of their own houses. Children who had a relationship with neighbors there or who had lived there for more than 10 years were more likely to have the intention to live in their parents’ houses, which seems to reflect their positive feelings toward the house and community where they spent their childhood. Children who felt that Koma was superior to their current living area in terms of “greenscape and landscape” and “safety and security” had a higher intention to sell or rent their parents’ houses. These living environmental factors are Koma’s strengths and seem to influence children’s decision making.

3.5. Discussion on the results of two logistic analyses

The results of the two logistic regression analyses indicated that parents who reported that they discussed the disposition of their house with their children had the intention of bequeathing their houses, and children who reported that they had not discussed it with their parents had the intention of neglecting the houses. In other words, for these parent–child pairs, the risk of a house becoming vacant after the parents leave is higher. That is, our hypothesis that the lack of parent–child discussions enhances the risk of vacant house generation was true from the children’s viewpoint on the discussion, but false from the parent’s viewpoint. This is consistent with another study (Sonoda Citation2010), which found that parents’ intention of their children inheriting their house was not fulfilled in the suburbs.

Regarding other variables, older parents intended to bequeath their houses to their children, which might be due to a stronger emotional attachment to their houses (Hoekstra and Dol Citation2021). Additionally, parents who took proactive measures and learned about the asset and value of the property were more inclined to sell or rent their houses by themselves, whereas parents who did not were more inclined to bequeath their houses to their children (Yoshikawa, Arita, and Fujii Citation2013). Therefore, it could be beneficial to encourage participation in seminars and consultation with specialists before parents become older. On the other hand, an important and feasible factor in preventing children from neglecting parents’ houses was discussions with their parents. Local governments could consider encouraging both parents and children to participate in seminars on housing utilization and to provide opportunities for them to discuss with experts.

This study contributes to the literature by tracking pairs of parents and children and exploring the factors of intergenerational discrepancy in attitudes toward housing inheritance; however, it has some limitations. Our questionnaire hypothetically asked both parents and children about their intentions regarding the house only to obtain hypothetical answers. It should be noted that this does not necessarily mean that parents and children will, in fact, behave as they answered when the situation arises. Although this study hypothesized that the lack of parent–child discussions increases the risk of this vacant house generation, there may be other risk-enhancing factors besides those measured in our survey. While it is difficult to conduct a questionnaire survey of many vacant house owners, qualitative research, such as interviews with both parts involved, is advisable. Due to the small dataset of parent–child pairs, the other datasets (i.e., parents and children) were used in the logistic regression analyses to identify factors that might enhance the risk of producing vacant houses. Future studies on the prospect of vacant houses should also use data on parent–child pairs, not just parents or children. We expect to confirm whether similar results can be obtained in other suburban areas and a more detailed analysis using a larger number of parent–child pair samples.

4. Conclusions

First, this study assessed the risk of vacant house generation by focusing on parent–child discussions using a dataset that linked parent–child answers. Up to 66.5% of the parent–child pairs had no discussion and 20.5% of pairs had different reports of having held such discussions. In addition, 7.8% of the pairs were at high risk of producing vacant houses, where parents intended to bequeath their houses, and children would neglect them. Second, this study identified the factors associated with parents’ intention to bequeath their houses: discussions with their children, old age, short age of the houses, lack of proactive measures, anxiety about renting, and stronger community attachment; and the factors associated with children’s intention to leave their parents’ houses: inadequate discussions with their parents, home ownership, and a lack of relationships with neighbors. These results suggest that it is preferable to encourage parents and children to participate together in seminars and consult with experts in order to reach a mutual understanding before the parents become older so as to reduce the risk of producing vacant houses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the residents of Koma-Musashidai for their generous support of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The questionnaire data are not publicly available due to a confidentiality agreement with survey respondents.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kimihiro Hino

Kimihiro Hino is an associate professor at the Department of Urban Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering of The University of Tokyo. Before joining the university in July 2014, he worked at the Building Research Institute. His research interests include crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED), healthy planning, and regeneration of housing estates.

Kyoya Mizutani

Kyoya Mizutani is a former graduate student at the Department of Urban Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering of The University of Tokyo.

Yasushi Asami

Yasushi Asami is a professor at the Department of Urban Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering of The University of Tokyo. His research interests include city planning, urban housing theory, and spatial information analysis.

Hiroki Baba

Hiroki Baba is a program-specific assistant professor at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies/Hakubi Center for Advanced Research, Kyoto University. He received his PhD from the University of Tokyo. His current research interests range from housing analysis to landscape and urban planning.

Norimitsu Ishii

Norimitsu Ishii is a head of Urban Development Division at the Urban Planning Department, National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management. He is also an associate professor at the Faculty of Engineering, Information and Systems, University of Tsukuba. His research interests include city planning and urban analysis.

References

- Accordino, J., and G. T. Johnson. 2000. “Addressing the Vacant and Abandoned Property Problem.” Journal of Urban Affairs 22 (3): 301–315. doi:10.1111/0735-2166.00058.

- Aktas, C. B., and M. M. Bilec. 2012. “Impact of Lifetime on US Residential Building LCA Results.” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 17 (3): 337–349. doi:10.1007/s11367-011-0363-x.

- Baba, H., and K. Hino. 2019. “Factors and Tendencies of Housing Abandonment: An Analysis of a Survey of Vacant Houses in Kawaguchi City, Saitama.” Japan Architectural Review 2 (3): 367–375. doi:10.1002/2475-8876.12088.

- Couch, C., J. Karecha, H. Nuissl, and D. Rink. 2005. “Decline and Sprawl: An Evolving Type of Urban Development–observed in Liverpool and Leipzig.” European Planning Studies 13 (1): 117–136. doi:10.1080/0965431042000312433.

- Deng, W. J., J. S. Hoekstra, and M. G. Elsinga. 2019. “Why Women Own Less Housing Assets in China? The Role of Intergenerational Transfers.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 34 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10901-018-9619-0.

- Deng, W. J., J. S. Hoekstra, and M. G. Elsinga. 2020. “The Urban-rural Discrepancy of Generational Housing Pathways: A New Source of Intergenerational Inequality in Urban China?” Habitat International 98: 102102. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102102.

- Doling, J., and R. Ronald. 2010. “Home Ownership and Asset-based Welfare.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 25 (2): 165–173. doi:10.1007/s10901-009-9177-6.

- Gentili, M., and J. Hoekstra. 2019. “Houses without People and People without Houses: A Cultural and Institutional Exploration of an Italian Paradox.” Housing Studies 34 (3): 425–447. doi:10.1080/02673037.2018.1447093.

- Hino, K., N. Ishii, T. Sekiguchi, and H. Baba. 2018. “Current Situation and Benefits of Living near Relatives in a Far Suburban Residential Area: Case Study in Koma-Musashidai District in Hidaka City, Saitama.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 83 (750): 1497–1504. doi:10.3130/aija.83.1497.

- Hirayama, Y. 2003. “Housing and Social Inequality in Japan.” In Comparing Social Policies: Exploring New Perspectives in Britain and Japan, edited by M. Izuhara, 151–171. Bristol: Polity Press.

- Hoekstra, J., and K. Dol. 2021. “Attitudes Towards Housing Equity Release Strategies among Older Home Owners: A European Comparison.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. doi:10.1007/s10901-021-09823-2.

- Hoekstra, J., and C. Vakili-Zad. 2011. “High Vacancy Rates and Rising House Prices: The Spanish Paradox.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie [Journal of Economic and Social Geography] 102 (1): 55–71. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2009.00582.x.

- Horioka, C. Y. 2014. “Are Americans and Indians More Altruistic than the Japanese and Chinese? Evidence from a New International Survey of Bequest Plans.” Review of Economics of the Household 12 (3): 411–437. doi:10.1007/s11150-014-9252-y.

- Iwata, S., and N. Yukutake. 2020. “Housing Wealth and Consumption among Elderly Japanese.” Housing Studies 35: 1–17. doi:10.1080/02673037.2020.1807470.

- Izuhara, M. 2016. “Reconsidering the Housing Asset-based Welfare Approach: Reflection from East Asian Experiences.” Social Policy and Society 15 (2): 177. doi:10.1017/S1474746415000093.

- Kikuchi, Y., and S. Nojima. 2007. “Resident’s Mind about Residence Selection in Suburban Housing Estates.” Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan 42 (3): 217–222.

- Koura, H. 2017. “Old “New Towns” in Kobe and Future Perspectives of Inhabitants in Shrinking Detached Housing Areas – Case of Takakuradai in Kobe City.” In Maturity and Regeneration of Residential Areas in Metropolitan Regions—Trends, Interpretations and Strategies in Japan and Germany: City & Region Vol. 2, edited by Y. Kadono, A. Beilein, J. Polívka, and C. Reicher, 130–145. Dortmund: Technische Universität Dortmund.

- Martinez-Fernandez, C., T. Weyman, S. Fol, I. Audirac, E. Cunningham-Sabot, T. Wiechmann, and H. Yahagi. 2016. “Shrinking Cities in Australia, Japan, Europe and the USA: From a Global Process to Local Policy Responses.” Progress in Planning 105: 1–48. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2014.10.001.

- Matsumura, H., and T. Setoguchi. 2014. “A Study on the Generation Change Depend on the Relocation of Detached Houses on the New Towns.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 79 (697): 711–719. doi:10.3130/aija.79.711.

- Ministry of Land. 2020. “Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.” Survey of Vacant House Owners. Accessed 18 April 2021. https://www.mlit.go.jp/report/press/content/001377049.pdf

- Ministry of Land. 2018. “Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. List of New Towns across Japan.” Accessed 9 January 2021. https://www.mlit.go.jp/totikensangyo/totikensangyo_tk2_000065.html

- Nishiyama, H. 2018. “Inhabitants’ Consciousness of Vacant Houses: A Case Study through A Comparison of Two Residential Areas in Utsunomiya City.” The Journal of Utsunomiya Kyowa University 19: 125–141.

- Nordvik, V., and L. Gulbrandsen. 2009. “Regional Patterns in Vacancies, Exits and Rental Housing.” European Urban and Regional Studies 16 (4): 397–408. doi:10.1177/0969776409102191.

- Nozawa, C. 2018. Oita Ie Otoroenu Machi [Ageing Houses and Declining Towns]. Tokyo: Kodansya.

- Sakamoto, K., A. Iida, and M. Yokohari. 2018. “Spatial Patterns of Population Turnover in a Japanese Regional City for Urban Regeneration against Population Decline: Is Compact City Policy Effective?” Cities 81: 230–241. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2018.04.012.

- Sekiguchi, T., K. Hino, and N. Ishii. 2019. “Shopping Environment Problems for Grocery Shoppers in a Far Suburban Residential Area and Possible Countermeasures: Analysis of Questionnaire Survey Data in Koma-Musashidai District in Hidaka City, Saitama Prefecture.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 84 (760): 1423–1432. doi:10.3130/aija.84.1423.

- Sonoda, M. 2010. “Solutions and Strategies to Manage and Re-invest Real Estate Owned by Elderly People at Suburb.” The Japanese Journal of Real Estate Sciences 23 (4): 46–53. doi:10.5736/jares.23.4_46.

- Suzuki, H., and S. Fujii. 2008. “Study on Effects of Place Attachment on Cooperative Behavior Local Area.” Infrastructure Planning Review 25 (2): 357–362. doi:10.2208/journalip.25.357.

- Suzuki, M., and Y. Asami. 2019. “Shrinking Metropolitan Area: Costly Homeownership and Slow Spatial Shrinkage.” Urban Studies 56 (6): 1113–1128. doi:10.1177/0042098017743709.

- Suzuki, S., M. Ishiwata, and F. Okita. 2008. “A Study on the Utilization of Suburban Detached Housing Stock through the Middle-aged and Elderly Dwellers’ Removal.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 73 (634): 2725–2732. doi:10.3130/aija.73.2725.

- Suzuki, S., and F. Okita. 2005. “A Study on Change in Residents and Succession of Dwelling in Suburban Detached Housing Areas: A Case Study of Ready-built Houses at Aoba Ward in Yokohama City.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 70 (597): 161–166. doi:10.3130/aija.70.161_4.

- Takada, K., and C. Nozawa. 2018. “Issues on Vacant Homes and Municipal Measures to Survey and Cope with Owner-unknown Homes.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 83 (751): 1747–1755. doi:10.3130/aija.83.1747.

- Tanikawa, H., and S. Hashimoto. 2009. “Urban Stock over Time: Spatial Material Stock Analysis Using 4d-GIS.” Building Research & Information 37 (5–6): 483–502. doi:10.1080/09613210903169394.

- Watanabe, R., R. Manabe, A. Murayama, and H. Koizumi. 2019. “Change of Land Use and Ownership and Traits of People Moving in In Detached Housing Areas in the Aging Tokyo Suburbs: Through the Exhaustive Survey in Kamigo Neopolis.” Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan 54 (3): 864–869.

- Wuyts, W., A. Miatto, R. Sedlitzky, and H. Tanikawa. 2019. “Extending or Ending the Life of Residential Buildings in Japan: A Social Circular Economy Approach to the Problem of Short-lived Constructions.” Journal of Cleaner Production 231: 660–670. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.258.

- Yoshikawa, S., T. Arita, and S. Fujii. 2013. “A Study on the Problems of Relocation by Elderly in Suburban Detached Housing Areas and the Possibility of Promotion Measures by the Private Sector.” Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan 48 (3): 963–968.

- Zhang, C., S. Jia, and R. Yang. 2016. “Housing Affordability and Housing Vacancy in China: The Role of Income Inequality.” Journal of Housing Economics 33: 4–14. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2016.05.005.