ABSTRACT

Spatial research on the eupchi is an important area of traditional Korean urban research. Previous studies generally focused on the spatial arrangement of the chiso in the eupchi. However, to understand the eupchi, we need to study different types of spaces in the eupchi and their functions. Thus, this study focuses on housing spaces rather than chiso. The purpose of this study is to investigate the residential characteristics of indigenous families who comprised the top local officials. In analyzing the spatial distribution of housing lots according to their attribution, the result derived as follows. First, less than two percent of the social class to which the aristocrats called yangban belonged lived in the eupchi at the end of the Joseon era. This two percent consisted of only representative indigenous families. Second, unlike other families, they also clustered on one side of the chiso and had the largest space for a community and the greatest housing density in the eupchi. This likely reflects the power of indigenous families in the local towns in a physical form. The primary merit of this study is that it sheds light on the socio-spatial characteristics of indigenous families in the eupchi in the late Joseon era.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and objective

Eup refers to town and eupchi to the downtown where the chiso (administrative office complex) of each town is located. The minimum administrative unit of the “eup” is the gun and hyun, which has a chiso. During Japanese occupation, three or four towns were combined into a city or county. Therefore, the study of the eupchi is very important to the study of Korean traditional towns; however, the study of Korean urban history is proceeding very slowly due to the limitations of historical data. Research on eupchi has yielded progress on topics such as the type and arrangement of chiso facilities (Kim Citation2004; Baek and Kikuchi Citation2017), the spatial structure of the eupchi with a focus on the chiso (Kim and Han Citation2000; Kim and Lee Citation2003; Kim Citation2017), and feng-shui landscape characteristics (Choi Citation2003, Citation2007, Citation2008). However, research on the characterization of eupchies’ residential areas and villagers designed to improve our understanding of the nature of the eupchi remains lacking. Research on villagers usually focuses on yangbanFootnote1 (Kwon Citation1998), petty officials (Lee Citation1995), and even slaves (Kwon Citation2005). However, researchers generally use householder registers for analysis, which do not cover residential areas. Only recently has a study (Baek Citation2019) examined the characteristics of residents through an analysis of residential areas in the eupchi. This shows that spatial research on eupchi is expanding from the chiso to residential areas, leading to studies on villagers. Accordingly, the field needs comparative research of various cases to derive more general findings.

The present study investigates the residential areas and villagers of the eupchi using maps. The study focuses on the indigenous families who have been primarily in charge of governing the respective eups since the Goryeo Dynasty era. The study also involved mapping residential areas of the eupchies in the late nineteenth century by crosschecking the original cadastral map (early 1910s) with the information on yanganFootnote2 (early 1900s), a land register from a survey in the late 1890s. This study is distinct from other studies because it studies the spatial distribution of indigenous families’ houses using constructed maps.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to shed light on the residential characteristics of the indigenous family in the respective eupchi, those who represented eupchi villagers. The study examines the social characteristics of the indigenous family and analyzes the spatial distribution and physical characteristics of their housing in the late nineteenth century. The study discusses how the social characteristics of the indigenous family, the ruling class of the local eup, manifested in the physical spaces of the eupchi.

The study was conducted via the following steps and associated methods: (1) a literature review on indigenous families of the study cases, (2) classification of housing lots in the eupchies based on Geopjo-Gajji,Footnote3 and classification of indigenous families’ housing lots by (using information on housing lots from the yangan), (3) analysis of the spatial distribution and physical characteristics of the classified housing lots (using the GIS estimation map), and (4) an investigation of the characteristics of the residential areas of the indigenous families in the two study cases().

This study expands on Baek’s (Citation2019) research by clarifying indigenous families and adding a study case. We looked at the similarities in the residential characteristics of indigenous families by comparing the two cases. In addition, the kernel density analysis was used to determine the residential area’s centrality. Finally, we looked at the housings of indigenous families in relation to Chiso’s location and Eupchi’s high-density housing area.

2. Literature review

2.1. Defining chiso and eupchi

The chiso is an administrative office complex to govern the eup in the Joseon Dynasty era. In the early Joseon Dynasty era, the government reorganized Joseon into approximately 330 eups in the process of centralizing governance of the country.Footnote4 The chiso was set up at the geographical center of each eup,Footnote5 where sooryeong, the chief administrator of the chiso, was sent from the central government.Footnote6 The area where chiso was located in was called eupchi.

The chiso had a dongheon as the central facility, where sooryeong held office, and auxiliary facilities of six departments.Footnote7 Among them, hyangcheong was where indigenous families, who were more knowledgeable about local affairs than sooryeong was, worked while they assisted sooryeong. The chiso facilities of each eupchi are identifiable on the old map from 1872 and the chronicle of the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, as well as in the yangan, which suggest that the main facilities have not changed much. During the Japanese occupation, the status of the eup weakened due to the consolidation of administrative districts and the use of chiso changed during modernization (Baek Citation2017).

2.2. Indigenous families and Aristocratic class in the eupchi

Sejongsillok-Jiriji (1432)Footnote8 includes records of indigenous family names for each eup. Indigenous families formed clans during the Goryeo era and took charge of ruling in each eup until the centralized rule of the Joseon Dynasty (Lee Citation2011). Under the Joseon Dynasty, sooryeong was sent from the central government and the indigenous families’ administrative authority weakened; however, those families continued to inherit the main offices of prefecture towns (Kawashima Citation1980). Families who did not hold local office but held an office with the central government, such as sooryeong, were classified as “yangban”. The indigenous families who maintained the status yangban increasingly refrained from holding local office and gradually left eupchies and formed “clan villages” near eupchies during the late Joseon era (Kim Citation2002).

The Settlement of Joseon (Citation1933) notes that the Joseon era did not have many large towns compared to Japan at the time because the relocation of the yangbans to outside the eupchi slowed urban growth (Zenshō Citation1933, 940).

2.3. A Hierarchical classification of the Geopjo-Gajji

The content of Geopjo-Gajji did not change even when the Daejeon-Hoetong (1865), the last revision of the Gyeongguk-Daejeon (1485), the Grand Rule of Law, was published. The Geopjo-Gajji outlined the restrictions on housing lot and house sizes within the city walls of Hanyang, the capital of Joseon, based on the status of officers. Although there were no specific regulations for local towns, the results of a housing lot size analysis (Baek Citation2019) suggest that the law was also applied to local cities.Footnote9 In other words, we can infer a villager’s class based on the size of their housing lot because the government allotted housing lots, whereas the size of the house depended on the individual’s economic wherewithal.Footnote10

The following table shows the housing lots and housing size regulations of the Geopjo-Gajji prescribed (). “pum(品)” indicates an office with the central government and sooryeong was at the six pum or higher level.Footnote11 The actual area of a housing lot was measured in “chuk (尺)” and rated between one and six. “bu(負)” is the area of chuk which is converted according to the land grade. When the government provided housing lots, it used the bu area of the third-grade housing lot as the standard. One bu of the first-grade land was 100chuk, while the third-grade of it was 70chuk. 100chuk is almost 100 square meters in present area units. In yangan, the lots of chiso were the first-grade land, while housing lots were often second-grade and farmlands were often third to fifth-grades.

Table 1. Research process.

Table 2. A hierarchical classification of the Geopjo-Gajji.

2.4. Previous studies

Since Kim (Citation1980), research on villagers during the Joseon Dynasty era has been extensively conducted. The studies used household registers as their primary sources, which have the advantage of containing information on the statuses and occupations of householders. However, householder registers are also limited because these registers only include the names of the administrative districts of the householders, not their locations. Kwon’s (Citation1998) study on Danseong is a representative study of villagers of the local eupchi. Danseong has been extensively studied because it is the prefecture with the most householder registers (the years 1678 through 1864). However, there is no yangan for the prefecture, making it impossible to obtain the spatial distribution of residential areas. In Danseong, the chiso was moved twice, but Kwon (Citation1998) found that about one percent of the villagers living in the administrative district where the chiso was located were yangban.

A recent study (Baek Citation2019) investigates the distribution of housing lots and associated characteristics in Yeonsan using a yangan. The study found that two percent of the housing lots were the correct sizes for the yangban, consistent with the findings from Danseong case.

Determining the householder’s class is likely to be far more accurate based on householder registers rather than based on the area of a housing lot listed in a yangan. However, it is rare for both a householder register and a yangan to exist for a prefecture and for the name of the householder in both to match because the two would have been compiled in different periods. Although we will need to analyze more cases, villager research using housing lot size likely has a strong potential for accuracy if there is enough data source for the area studied.

The present study builds on Baek’s (Citation2019) finding that two percent of housing lots were associated with indigenous families. Accordingly, we focused on indigenous families and compared the case of Yeonsan eupchi with that of Hansan eupchi.

3. Study setting and methodology

3.1. Case outlines and indigenous family

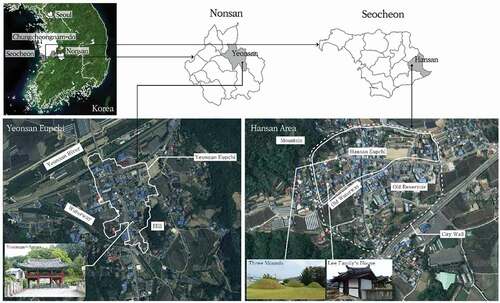

Study cases are the Yeonsan eupchi, which has no city wall, and the Hansan eupchi, which has a city wall. They both have yangans, land registers, and retain the shape of the town as represented on the original cadastral map due to a lack of urban development.

3.1.1. Yeonsan eupchi and the indigenous “Song” family

The Yeonsan eupchi of Yeonsan Prefecture is a non-walled city. “Yeonsan-Amun” is the chiso’s main gate and has been designated as cultural heritage. Yeonsan-Amun serves as a reference point in spatial estimations of the eupchi and the spatial arrangements of chiso.

The Yeonsan eupchi has rivers and waterways to the north and southwest and hills to the east. The natural terrain establishes areas’ borders instead of walls. The chiso was located westward with its back to the hills in the east. In front of the chiso, there used to be a road that goes from north to south. Housing lots were concentrated around this road and the chiso ().

The Sejongsillok-Jiriji (1432) lists Song, Seo, Son, and Ko as indigenous family names from the Yeonsan. Among them, the Seos’ place of origin is Yeonsan; however, the Seo family’s historic remains and clan are in another prefecture. Historical data sources for the Son and Ko families related to the Yeonsan are also absent.

The Song family’s place of origin is Yeosan, not far from Yeonsan. The family (Yeosan Song) held main offices in the Yeonsan in the early Joseon Dynasty period; however, the family’s power (in Yeonsan Prefecture) weakened after the middle of the Joseon Dynasty era because they held offices in the central government (Kwon Citation2016). Their clan village remains in the north of the Yeonsan eupchi.

The Yeonsan chronicle makes multiple mentions of the EunjinFootnote12 Song family, a related family of the Song family. The Eunjin Song family formed connections with yangban families of Yeonsan based on their academic thoughts and expanded their residential area to Yeonsan (Lee Citation1996). A descendant of the Eunjin Song family is currently running a large rice mill in the Yeonsan eupchi.Footnote13 In this study, we treated the Yeosan and Eunjin Song families as one family because they both derived from a single family.Footnote14

3.1.2. Hansan eupchi and the indigenous “Lee” family

The Hansan eupchi of Hansan Prefecture is a walled city. Partial fixed earth and rock wall remains have been designated a cultural heritage site.The city wall had four gates in each of the four directions: east, west, north, and south, with a road in each direction. To the south of the east to west road, there used to be a river that ran east to west (the area is currently all road). South of the river was mostly farmlands and in the north chiso and housing lots. The chiso was located in the north of the area within the city’s wall and against the mountain on the northwest side. The northern part of the city wall uses a mountain as part of the wall. The housing lots clustered around the chiso were surrounded by natural terrain as in the Yeonsan eupchi ().

Sejongsillok-Jiriji (1432) lists Lee and Kim as indigenous family names from the Hansan. The Lee family’s place of origin is the Hansan and there are still family tombs and buildings in the Hansan eupchi. The Hansan Lee family cemetery is a propitious site for a grave according to feng-shui and legend goes that the Hansan Lee family became more prosperous after setting up their cemetery in that location.Footnote15 In front of tombs, there are three established mounds that symbolize eggs in feng-shui (). In the 1930s, there were four Lee’s clan villages (200 households in total) in Hansan, the highest number of Lee’s clan villages in one prefecture in Korea at the time (Zenshō Citation1934).

In contrast, there is no influential branch of the Kim family with a historical data source in the Hansan.

3.2. Study range and method

3.2.1. Spatial range of eupchies

There is no clear definition of the spatial scope of the eupchi in the literature. Many researchers, including Lee (Citation2004), have set the spatial boundary of the eupchi as a space recognizable by the surrounding natural terrain. In the present study, we define the eupchi as a concentration of housing lots around the chiso. This group of housing lots is spatially separated from the rest of the town because it is surrounded by hills and waterways. In the case of Hansan, the boundary is clear due to its city wall. However, the space within the wall can be divided into two areas: a concentrated area of housing lots and the chiso as in the Yeonsan eupchi and an area separated from it by farmland and waterways. Accordingly, we defined the areas with clustered housing lots and the chiso within the city wall as the minimum expanse of the eupchi. The city wall of Hansan was a hill-like wall of earth, and, as a result, villagers can freely go outside the wall and the communities within and outside the city wall were connected. Therefore, we included the housing lots near the city wall as the maximum scope of the eupchi. We then conducted a comparative analysis by separating the minimum spatial scope of the Hansan eupchi and the maximum spatial scope of the area within and around the Hansan city wall.

3.2.2. Data and method

For analysis, we chose the late Joseon era (end of the nineteenth century to the early twentieth century), which was before the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1910, a corresponding period for the yangan survey period (1898–1904).

The primary data sources for the study were the Chungcheongnam-do Yeonsan-gun Yangan (1901), the Chungcheongnam-do Hansan-gun Yangan (1903), and the original cadastral map (1914) ().

Yangan is the complete land record that the Gwangmu Land Survey Project, which started in 1898, published between 1901 and 1904. The records for each lot include the name of the landowner, land use, actual land area (in chuk), land grade, converted land area based on their own grade (bu), house size (number of kan), and the type of roof. We can link individual lots together through the owners’ names because the names of the owners of the houses adjacent in four directions to a lot are also listed. The records of lots begin with those in the chiso, followed by housing lots adjacent to the chiso in order of proximity. The yangan also includes the names of villages, which allows us to infer their locations based on the present names of the villages.

The original cadastral map was the first cadastral map that the 1910–1918 survey team created after the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1910. Unlike the yangan, the original cadastral map shows into which area the chiso’s facilities are partially integrated and marked as government-owned lands as well as newly constructed roads and railways. Dongheons have mostly been converted to township offices to date and is still in use. The Dongheons that retained the Joseon era buildings have designated them as cultural heritage. Therefore, using Dongheon as a reference point in space, we can estimate the locations of the lots by comparing them with those in the yangan.

Hence, we analyze the distribution of housing lots based on the information of the area (bu), size of buildings (kan), and owners’ family name from the yangan. We also conducted an spatial analysis by ArcMap program using the constructed map created by visualizing the records in the yangans based on the original cadastral maps.

4. The dwellings of indigenous families in the eupchi

4.1. Spatial distribution of housing lots size

The length of one chuk, which was used for the yangan survey at the end of the nineteenth century, is estimated at approximately 98 centimeters.Footnote16 In terms of the area of a housing lot based on the length of one chuck, a two bu housing lot provided to common people was approximately 166 square meters(2.4bu).

In the following (), we describe the results of a conversion of actual area (chuck) listed in a yangan to a bu area of land grade three. The Yeonsan eupchi had a total of 87 housing lots with an average area of 2.9 bu. Among them, 48 percent were two bu or smaller housing lots: the size range for common people; approximately two percent were eight bu housing lots: the size range for the yangban class. The Hansan eupchi had 46 housing lots while the area in and around the city wall had 105 housing lots. As in the case of Yeonsan, one to two percent were eight bu housing lots and no housing lots were bigger than eight bu.

Table 3. Data source.

Table 4. Building lots size converted in bu of land grade.

The distribution on the map is as follows (): in the Yeonsan eupchi, five to eight bu housing lots, the size of upper-class lots, were mostly located in the north of chiso (dongheon). In front of Dongheon, there are mainly three to four bu housing lots, sized for the middle class.

In Hansan, there were 15 five to eight bu housing lots; only two of them were outside the wall and the rest were within the city wall. Within the city wall, all of them were located in the Hansan eupchi, which was to the north of the river. Unlike in the Yeonsan eupchi, three to four bu housing lots in Hansan were not clustered in front of dongheon ().

This study’s two cases have the following in common: (1) a concentration of five to eight bu housing lots in an area near dongheon, (2) the similar percentage of five to eight bu housing lots, (3) eight bu housing lots make up less than two percent of housing lots, and (4) no housing lots are bigger than eight bu. In other words, less than two percent of lots were of the upper class, including the yangban class, resided in the eupchi.

However, in terms of the actual area (chuck), over 10 percent of housing lots were at least 750 chuck (eight bu)Footnote17 (). The interpretation is that the size of the bu reflects the social class in contrast to the actual area. Moreover, in Hansan, the average area of housing lots was different between those in the eupchi and those around the city wall. Housing lots were larger in the eupchi, which suggests that many officials rather than common people lived near the chiso.

Table 5. Actual building lots size by chuck.

4.2. Spatial distriution of indigenous families

4.2.1. The “Song” family case in Yeonsan eupchi

In the Yeonsan eupchi in 1901, the Song family lived on 12 sites and the Seo family on two sites, while other indigenous families like the Son and Ko families did not reside in the Yeonsan eupchi ().

Table 6. Distribution of indigenous families housing lots.

The distribution of the Song family’s housing lots suggests that they primarily lived in the north of dongheon (). This is similar to the distribution of the five to eight bu housing lots in this area, which were for the upper class. The most common family name other than those of the indigenous families was Kim; however, there was no cluster of Kim family members in the eupchi. None of the distributions of other family names showed clusters characteristic of the Song family. In other words, the indigenous Song family was mostly clustered in the eupchi among all the families and largely resided in the northern part of the eupchi, which had a large settlement area.

4.2.2. The “Lee” family case in Hansan eupchi

The indigenous families of the Hansan were the Lee and Kim families, who mainly lived within the city walls (). However, the Lee family, unlike the Kim family, did not live south of the river (outside of eupchi).Footnote18 As there were no sources that suggest that any branch of the Kim family lived in Hansan as discussed in Section 3.1 (2), we focused on the Lee family in this study. The Lee family’s housing lots were primarily located in the village below the mountain near dongheon (). This is where the Lee family cemetery and buildings were located. The village also had a relatively large number of large housing lots of five to eight bu, as in the Yeonsan eupchi.

A note about Hansan: certain family names such as Na were found only within city walls (in the eupchi in particular) while others such as Park were only found outside city walls (outside the eupchi in particular). The names of the families living inside and outside the city walls were different. The Lee family occupied the class that primarily resided within the city walls. This can suggest the importance of class qualifications for residing within city walls as in the case of Hanyang, the capitalFootnote19; however, we do not discuss the issue in this study.

4.2.3. Sub-conclusion

Indigenous families who still have residences in the two regions to date are the Song and Lee families. These two families resided in specific areas even in the eupchies in 1901, primarily areas with large housing lots and a large space for settlements. However, the areas were located on the side, not the front, of dongheon, the headquarters of the local administration. This contrasts with the petty officials who lived in a cluster in front of the gate of the chiso, which is on the front side of dongheon.Footnote20 We can infer that the indigenous families were involved in local administration in such a way that is comparable to that of sooryeong, and their power manifested in the form of spatial occupancy.

4.3. Housing lots sizes of indigenous families

The average housing lot area of the indigenous families – the Songs and Lees – was larger than the overall average for the respective areas, as well as the housing lot areas of other families (). In particular, the Song and Lee families were the only owners of eight bu housing lots. This likely reflects the social status of the indigenous families in the respective eupchies.

Table 7. The average housing lot area according to owner’s surname.

A note about the Hansan eupchi: the Na family housing lots were as large as those of the Lee family and near dongheon like the Lee family’s. However, unlike the Lee family, whose housing lots were also found outside city walls, the Na family resided only in the eupchi (). This suggests that the Na family likely had a status comparable to the Lee family at the end of the Joseon era, despite not being indigenous.Footnote21

4.4. Housing sizes of indigenous families

4.4.1. The housing sizes of indigenous families

Housing size is related to the owner’s economic resources, whereas the government provided housing lots based on administrative class. In general, the common people during the Joseon era were estimated to have houses of around three kans.Footnote22 This was much smaller than the legal maximum of ten kans. The average housing size in the Yeonsan eupchi was 3.8 kans, while the average in the Hansan eupchi was 3.5 kans, and the average for the area around the Hansan city wall was 3.1 kans, all of which were lower than the legal maximum ().

Table 8. Housing sizes.

The Yeonsan and Hansan eupchies had a similar distribution of housing sizes. However, in the Expanded Area of , 72 percent of houses were smaller than three kans. This suggests that the common people lived more often outside of the eupchi. Moreover, houses larger than six kan existed only in the eupchi. In conclusion, those living in the eupchi had larger houses. Based on this, we can speculate that those living in the eupchi had a higher economic status than those who did not.

The housing sizes of indigenous families are shown in . Undoubtedly, the houses of the indigenous Song and Lee families were more than one kan larger, on average, than those of other families.

Table 9. The average building size according to owner’s surname.

The largest house in both Yeonsan and Hansan was twelve kans in size. Yeonsan had three twelve kans-size houses, two of which belonged to the Song family. Hansan had one twelve kans-size house, which was owned by the Lee family. This suggests that the indigenous families’ social status as represented by housing lots is also represented their economic resources.

4.4.2. The spatial distribution of lots according to housing size

Large housing lots did not necessarily mean large houses; however, the distribution of large houses was similar to that of large housing lots (). In both cases, larger houses were in areas where the respective indigenous families were predominant, which were also the areas with large housing lots.

Indigenous families lived in clusters and owned large houses. The kernel density of the number of kan of the houses demonstrates a high density in the areas where the Song and Lee families lived (). This indicates that these are the areas with more buildings in addition to the respective chiso. It also suggests that the area which was indigenous families lived in had many habitants than other areas in the eupchi.

5. Conclusion

This study aimed to shed light on the residential characteristics of indigenous families in eupchies in the late Joseon era. Indigenous families were the local aristocracy of the Goryeo Dynasty era and mainly were involved in local politics. However, with the start of centralized government under the Joseon Dynasty, their social status began to change. As a result, their pattern of residence in eupchies changed. The indigenous families who became yangban and continued to elevate their status tended to move outside of the eupchi towards the end of the Joseon era. Other indigenous families remained in the eupchi and took over local administration, helping sooryeong.

This study focused on the indigenous families who still had traces in the eupchi. We analyzed and compared the sizes of the housing lots and houses of the indigenous families recorded in yangans.

The two cases demonstrated similar proportions of classes (based on housing lot size) and the yangban (based on eight bu housing lots), which was around two percent. This result has a similarity to Kwon’s (Citation1998) and Baek’s (Citation2019) results. In addition, unlike the actual area (), the ratio of the area assigned according to the social class () shows the similarity in which the ratio increases toward lower classes. In other words, this suggests that the information of yangan reflects the social situation of the time, analyzing information of yangan has the potential in the socio-spatial study of historic cities.

The indigenous Song and Lee families, who resided in eupchies in the nineteenth century, lived in larger housing lots and houses than other families. Not all of them owned large housing lots and houses; however, indigenous families owned the largest housing lots and houses in a eupchi and lived in areas where the largest housing lots were located. Their communities were located on the side of dongheon, a large area for settlement, and had a high housing density.

Judging from the physical characteristics, indigenous families were likely to be socially and economically superior to other families in the eupchi even during the end of the Joseon era. Moreover, indigenous families lived in clusters in specific areas, which are likely central villages in the eupchi. They likely first settled in the eupchi with large spaces, which made it easy to gather in the same community. Also, their wealth, which had been accumulated for a long period around eupchi, would have sustained their dwellings in eupchi to this day.

This study clearly demonstrated that one of the groups in a superior position to other villagers in a eupchi was indigenous families. In particular, the distribution of their residential areas shows that settlements were established around indigenous families, despite their small numbers, in a eupchi.

In this study, we developed a visual representation of historical records as spatial data and delineated the spatial scope of a eupchi to complement the limitations of philological sources. The study also clarified the morphological residential characteristics of indigenous families, who continued to reside in a eupchi even during the late Joseon era, which is the primary contribution of this study.

This study has implications for historical cities where physical relics do not remain, so they cannot be preserved and their physical forms disappear. In particular, not only large-scale block-type development behaviors but also excavations to restore the history drives out residents from the city who still have roots in the place. We should be concerned about the organicity of people and places that are formed according to the time that accumulates in the place.

Indigenous families had been in charge of the administration of cities for centuries, maintaining an organic relationship with the locals. Although they have not sustained an administrative role in the present, unlike other resident groups, they still dwell in eupchi, and as natives, they best understand the culture of the local community and play a role as an anchor of that community. These are the assets of traditional cities that are of unknown quality. Therefore, it is necessary to give sufficient consideration to the clusters of native communities when planning and managing the city.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hyojin Baek

Shigetomo Kikuchi is an Emeritus Professor of the Faculty of Human-Environment Studies at Kyushu University, Japan. He received a Ph.D. from Tokyo University in 1987. His research interests include life history, occupation, and housing in traditional settlements.

Shigetomo Kikuchi

Hyojin Baek is a Research Professor of the Department of Urban Engineering at Hanbat National University, Japan. She received a Ph.D. from Kyushu University in 2017 and served as an Academic Cooperative Researcher of the Faculty of Human-Environment Studies until 2021. Her research interests include the local cities of Joseon, smart cities, and future cities.

Notes

1 An aristocratic class of Joseon. To keep their social position, males had to pass the national examination.

2 A parcel-level land register data.

3 A hierarchical classification system regulated in the Gyeongguk-Daejeon(經國大典), the grand rule of laws.

4 There are around 330 eups in Gyeongguk-Daejeon(1485) and 343 eups in Jeungbo Munheon Bigo(增補文獻備考), revised and enlarged edition of the reference compilation of documents on Korea (1903–1908).

5 The location of chiso was considered with feng-shui, defense, geographical center, and the central village location at that time (Kwon Citation1998; Baek and Kikuchi Citation2016).

6 Sooryeong’s term of office was 1800 days (Leejeon (humam resource affair part) of Gyeongguk-Daejeon, 1485).

7 Leejo (吏曹) – the Ministry of human resource, Hojo (戶曹) – the Ministry of Population and Housing, Yeajo (曹曹) – the Ministry of Culture and Education, Byeongjo (兵曹) – the Ministry of War, Hyeongjo (刑曹) – the Ministry of Justice, Gongjo (工曹) – the Ministry of Construction.

8 Geographical Appendix to the Veritable Records of King Sejong, 1432.

9 The study gives the following reasons. 1) The size of the housing lot of yeonsan sooryeong who had six pum, was matched to the size of the six pum grade housing lots, 2) Not only yeonsan hadn’t any officer higher than six pum (cronicles in 1896) but also there was no housing lot area larger than eight bu as offered to six pum officer, 3) Hanyang was used as a model when establishing local towns.

10 In fact, considering the size of the house in yangan, it is much smaller than the regulations of Geopjo-Gajji. After the the Japanese Invasion of Korea (in 1592), economic deterioration prevented the restoration of traditional architectural styles, and overall housing was downsized (Shin Citation1975, 114–115).

11 Also 6 pum or higher level were called yangban.

12 Eunjin is a prefecture adjacent to Yeonsan.

13 Ie-o rice mill, interview. 2016.10.9.

14 Because Song’s three siblings settled in different prefectures, there are three origin surnames in the Song family. But they are still relatives and do not marry each other.

15 The Digital Local Culture Encyclopedia of Korea, The Academy of Korean Studies, grandculture.net/en/, 2020.01.14.

16 The length of one chuk of the main scale is estimated at 20.48 centimeters (Park Citation1967). And Tackjijyunjeol (度支準折), published in the late Joseon era, refers that the length of one chuk for yangan is 4.775 times as long as main scale chuck. As a result it can be estimated 98 centimeters.

17 The bu was calculated by rounding off ten units of chuk in yangan. As a result, eight bu ranges 750–849 chuk.

18 In the case of Kim, it can be seen that it is concentrated in front of the main gate of chiso, the southeast side of the dongheon lot. The space in front of Chiso was occupied by the petty officials (from the named origin) and Kim’s housing lot sizes smaller than other families. This suggests that Kim’s social status was lower than Lee’s.

19 Son (Citation1976) suggests that the people who could be reside in the city wall was yangban and officials as a general rule. But his argument is still under discussion because there are some studies (Chung Citation2015) to claim that other commoners who help work for yangban and officials lived in their own housing lots of the city wall.

20 The name ajeon(衙前) calling petty officials was oriented from that their workplace was in front of dongheon (Encyclopedia of Korean Culture). 衙 means the center of the administration or dynasty and 前 means front. They also were called ajeon because they usually lived in front of chiso in Korea (The Society of Korean Historical Manuscripts Citation1996, 217).

21 There are only two records of Na family in Hansan. One is the sooryeong of Hansan in 1592 and one is who passed the national exam in 1597 from Hansan. (The Academy of Korean Studies, people.aks.ac.kr, 2020.1.20.).

22 It consisted of two rooms and one kitchen. The size of kans are all different. The size of edge kan is 2.2 × 2.5 m, center kan is 2.2 × 3.05 m of Yeonsan-Amun (actual measurement).

References

- Baek, H. 2017. “A Spatial Composition and Inhabitants’ Specificity of Yeonsan Eupchi in the Late 19th Century.” Ph. D. Dissertation, Kyushu University, Japan.

- Baek, H. 2019. “Analysis of the Spatial Distribution of Villagers by Class in the Yeonsan-hyun Eup-chi Using the 「Chungcheongnamdo Ryang-an」 of 1901, an Official Land Register of the Joseon Dynasty.” Urban Design 20 (1): 111–124. Urban Design Institute of Korea.

- Baek, H., and S. Kikuchi. 2016. “The Common Principle of Facilities Arrangement on the Eupchi of the Joseon Dynasty Period; by Comparative Analysis with Documents and Illustrated Maps.” Journal of Architecture and Urban Design 29: 1–8. Japan: Kyushu University.

- Baek, H., and S. Kikuchi. 2017. “A Restoration Study on the Spatial Composition of Chiso on Yeonsan-hyun Eup-chi in Joseon Dynasty Period; through Constructing A Map from Ryang-an, A Record of Land.” The Journal of AIJ, Planning 82 (733): 657–666. Architectural Institute of Japan.

- Choi, W. 2003. “A Study on Jinsan(鎭山) of Traditional Eup(邑) Towns in Gyeongsang Province.” Journal of Cultural and Historical Geography 15 (3): 119–136. The Association of Korean Cultural and Historical Geographers.

- Choi, W. 2007. “Locational Analysis and Classification of the Eup-Settlements in the Joseon Dynasty Period from Feng-Shui’s Point of View.” The Journal of KGS 42 (4): 540–559. The Korean Giographical Society.

- Choi, W. 2008. “The Historical Restoration of the Traditional Eup Towns in Namhae-eup.” A Journal of Gyeongnam Cultural 29: 271–306. Gyeongnam Cultural Research Institute. Korea.

- Chung, J. 2015. “Unchanged Residential Area System in Bukchon(北村), Seoul since the 18th century.” The Journal of Seoul Studies 61: 113–156. The Institute of Seoul Studies. doi:10.17647/jss.2015.11.61.113.

- Kawashima, F. 1980. “The Local Gentry Association in Mid-Yi Dynasty Korea: A Preliminary Study of the Changyong Hyangan 1600–1838.” Journal of Korean Studies 2: 113–137. Center for Korea Studies, University of Washington. doi:10.1353/jks.1980.0003.

- Kim, H., and S. Han. 2000. “Transformation Process of the Spatial Structure of Ulsan Eup-Sung in the Period of Japanese Occupation; Focusing the Analysis of Land Records.” The Journal of AIK, Planning & Design 16 (7): 71–78. The Architectural Institute of Korea.

- Kim, K. 2002. “Layout System of Government Office Building on ChungCheong-Do in the Late Chosun Dynasty.” Ph. D. Dissertation, Heongju University, Korea.

- Kim, K. 2004. “A Study on the Standard in Building the Provincial Eupchi in the Chosun Dynasty; Focused on ChungChong-Do in the Literature of the Late Chosun Dynasty.” The Journal of AIK, Planning & Design 20 (5): 108–204. The Architectural Institute of Korea.

- Kim, K., and J. Lee. 2003. “A Study on the Spatial Structure of ChungChong-Do Province Eupchi in the Late Chosun Dynasty.” Journal of Architectural History 12 (1): 43–58. Korea Association for Architectural History.

- Kim, T. 2017. “The Remains of the Old Urban Structure after the Destruction of Cheongju Castle, Korea.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 16 (2): 287–294. Architectural institute of Japan, China, and Korea. doi:10.3130/jaabe.16.287.

- Kim, Y. 1980. “The Social Status of Residents of Hansung and Their Moving in Late Joseon.” The Journal of Sungkok 11: 33–84. Sungkok Journalism Foundation.

- Kwon, K. J. 2005. “The Characteristic of the Government Slaves in the Danseong District.” The Journal of AKHS131: 285–306. The Association for Korean Historical Studies.

- Kwon, K. S. 2016. “The Pluralistic Kinship Consciousness and the Social Network of Yŏsan Songssi Sibi Segye, Twelve Family Lines of Yŏsan Song Lineage.” Kyujanggak 48: 95–145. Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, Seoul National University.

- Kwon, N. 1998. “A Study on the Structure and Constituent of County Sear(邑治) in the Late Joseon Dynasty.” A Journal of Korean History 4: 345–365. The Society for Studies of Korean History.

- Lee, C. 1996. “Background and Characteristics of Their Activities of Yeonsan Native Gentry in the Late Joseon.” Master’s thesis, Gongju National University, Korea.

- Lee, D. 2004. Ecological Implications of Landscape Elements in Traditional Korea Villages. Korea: SNUPRESS.

- Lee, H. 1995. “A Study on the Structure and Ritual of County Seat in Late Chosŏn Dynasty.” The Journal of KHA 147: 47–94. The Korean Historical Association.

- Lee, S. 2011. Korean Indigenous Families and Genealogy. Korea: SNUPRESS.

- Park, H. 1967. “On the Standard Scale of Length in the Lee Dynasty of Korea.” Journal of Eastern Studies 4: 199–274. Korea: Daedong Institute for Korean Studies, Sungkyunkwan University.

- Shin, Y. 1975. Hanok and Its History, an Outline of Korea Architect History 1. Korea: Dongii Culture Press.

- Son, J. 1976. “A Study on Cities in the Joseon Dynasty_Institutional and Functional Aspects.” PhD diss., Dankook University of Korea.

- The Society of Korean Historical Manuscripts. 1996. Joseon Dynasty Life History. Critical Review of History Press.

- Zenshō, E. 1933. The Settlements of Joseon, The Japanese Government-General of Korea.

- Zenshō, E. 1934. The Surnames of Joseon, The Japanese Government-General of Korea.