ABSTRACT

Courtyard” is one of the ancient domestic identity patterns of Iranian architecture in most of the traditional houses in hot and dry climate. The aim of this study is to identify the geometric and natural characteristics of courtyards in historical houses of Isfahan city in hot-arid climate. In this research, thirty historical courtyard houses were selected and analyzed as the case studies. The results show that the average ratios of length/width, height/length and height/width of the courtyards are 1.3, 0.3 and 0.4, respectively. The courtyard area averagely covers 31% of total area of houses and about 29% of the courtyard area is allocated to natural elements: 7% to water surface and 22% to plant coverage. The average ratio of the total area of openings to courtyard walls is 35%. As final results, the linear equations and correlation coefficients between the geometric and natural properties of courtyard houses are presented. The results of this research could be used as design guides for contemporary courtyards in hot-arid climate especially in Isfahan city.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Courtyards are traditional domestic patterns in many countries of North Africa, South America, Europe and Asia. The traditional courtyard pattern in Iran (as one of the oldest civilizations in the world) dates back to 3000 BC (Edwards et al. Citation2005) and has been used as a design pattern for various life functions. Courtyard as one of the most successful elements of climate-compatible architecture is abundantly seen in traditional architecture of Iran’s four climates (cold, hot and dry, hot and humid and temperate), especially in cities with hot and dry climates, such as Isfahan. Optimal use of solar radiation in hot and cold seasons of the year, providing thermal comfort in internal and external spaces and protecting against adverse winds are among the climatic factors that have led to the formation of courtyards.

Many research studies have been conducted on the typology of historical houses in different cities of Iran in terms of the spatial-functional structure, architectural stylistics, chronology and the physical-historical changes, but a few studies have been done on physical and especially the role of natural features in courtyards of historic houses. Soltanzade (Citation2011), introduced the social and cultural aspects as the main factors of shaping this pattern in traditional houses, the role of geographic and environmental phenomena in open spaces and courtyards’ formation is almost obvious. In this regard, in order to identify the varieties of open spaces or courtyards in traditional Iranian architecture, he has classified the varieties of open spaces of traditional houses (in Iran) into ten types including; 1) Atrium, 2) Pit-parterre, 3) Orangery, 4) Backyard, 5) Small garden, 6) Terrace, 7) Stable’s courtyard, 8) Ward, 9) Enclosure, 10) Surrounded flat roof. Ghasemi Sichani and Memarian (Citation2010), in a research entitled “Typology of Ghajar era house in Isfahan”, have found that in Isfahan with semi-hot and dry climate, architectural features are mainly introspective and built based on the characteristics of architectural space, structure and decoration, and they can be divided into three different types: Safavi, second and third (Kordi) of Qajar. Furthermore, in “Analysis of the structure of the plan of the Pahlavi’s House of Artists (Mohtashmi) of Isfahan based on the Gestalt rules”, the results show that the principles of Gestalt theory have influenced spatial arrangement, shapes and proportions, mass-to-space ratio and their compositions (Shahzamani Sichani and Ghasemi Sichani Citation2017). In a typology study of the physical-functional structure of residential architecture in Golestan province(Iran), the results show that vernacular architecture of this province can be recognized in three types: Vernacular architecture of the plain and flatlands, Residential units of hillside and Housing units on steep mountainous slopes (Soltanzadeh and Ghaseminia Citation2012). Hedayat and Tabaian. (Citation2016) in a research study entitled: “The survey of elements forming houses and their reasons in the historical fabric of Bushehr(Iran)”, with the aim of presenting contemporary design solutions, analyzed the physical, functional and semantic characteristics of different spatial types of historic houses in Bushehr. Farahbakhsh, Hanachi, and Ghanaei (Citation2018), in a research on typology of historical houses in the old city fabric of Mashhad(Iran), from the early Qajar to the late Pahlavi І era, classified the types of historic houses based on shape and form of physical elements. The results of this study enable the distinction and categorization of historical houses based on their formal features, for example, the form of the entrance portal, vestibule, hallway, courtyard, and ivan, or the mode of interior and exterior facades’ decorations. The three residential types include two Qajar-era types with an introvert architecture, and the third type from the Pahlavi I era with an extrovert architecture. Khakpour, Ansari, and Tahernian (Citation2010), in typology of houses in old urban area of Rasht(Iran), analyzed and compared the historical houses of Rasht city with a general overview on plans, orientation, physical elements and their components. Soheili-fard et al. (Citation2013), in a research entitled “Examine the interaction of traditional Iranian architecture principles in terms of form, orientation and symmetry to the solar energy, case study: Abbasiyan house in Kashan”, demonstrated that the thermal system of the Iranian houses is derived from the principles that have created not only a coherent structure in traditional Iranian architecture, but also a harmony between the building and its environment for human comfort. In analyzing the hidden spatial system of residential vernacular architecture of Mashhad(Iran)-based on the theory of space syntax- the results showed that the courtyard is an element that is located as the communication node in central part of the plan. Furthermore, ground floor rooms have multiple functionalities based on individual activities in-house, and the terrace (Baharkhab) and balcony (Ivan) as the open spaces are complementary of closed spaces (Rokni and Ahmadi Citation2017). Moradi, Matin, and Dehbashi Sharif (Citation2018), in studying the physical structure, patterns and variations of the central courtyard in traditional housing units of Tabriz, showed that courtyards are closer to a square shape. The maximum frequency ratios for the length/width, length/height and width/height are 0.8, 2.5 and 2, respectively. Mahdavinejad, Mansorpoor, and Hadianpoor (Citation2014), in a research entitled “Courtyard phenomena in contemporary architecture of Iran, case studies: Qajar and Pahlavi era”, demonstrated that courtyard is a kind of multifunctional (social-cultural, environmental-climate and physical) spaces which make such complicated plans accessible and functionally efficient. Soflaei, Shokouhian, and Shemirani (Citation2016), in a study entitled “Traditional Iranian courtyards as microclimate modifiers by considering orientation, dimensions and proportions”, conclude that most of the studied Iranian courtyards are particularly designed to enable orientation, dimension and proportion to act as microclimate modifiers. Furthermore, they develop a physical–environmental design model for central courtyards as a useful passive strategy which can be generalized for the wider use of environmentally sustainable design principles in future practice concerning courtyards for buildings in hot-arid climate (Soflaei, Shokouhian, and Shemirani Citation2015).

According to a review on previous studies, the historical houses of Isfahan have been mostly studied according to these aspects: spatial-functional relations, socio-cultural characteristics, architectural stylistics and physical-historical changes (). Previous research studies did not emphasize the geometric and natural properties of the courtyards as the main elements of the houses; because of the mentioned research gap, this study is conducted with the main purpose of recognizing geometric and natural properties of the courtyards in historical houses of Isfahan. The question in this research is: “what are the geometric and natural characteristics of the courtyards in historical houses of Isfahan?” In order to answer this question, classify and analyze the geometric and natural aspects of the traditional courtyards in the hot and dry climate of Isfahan, a number of historic houses in Isfahan were selected and their courtyards were categorized, compared and analyzed in terms of the geometric characteristics and the role of natural elements.

Table 1. Review of research on central courtyards in Iran

2. Study area

This research has been performed in Isfahan city. Its longitude and latitude are 51°39ˊ North and 32°38ˊEast, respectively, with the elevation of 1550 meters above sea level. It is bounded by the desert plain from North and East and by Zagros Mountains from West and South. According to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, Isfahan has a hot and dry desert climate (BWk), cold winters and hot summers (Peel, Finlayson, and McMahon Citation2007). shows the geographic location of Isfahan city in Iran.

Isfahan is one of the metropolises located in hot and dry climate of Iran, where the extent of historical areas and multiplicity of historic buildings are considerable compared to other cities in Iran; during the last two decades, some parts of the historical areas and buildings in this city have been exposed to destruction and land use change. In order to recognize and preserve the architectural patterns of historic houses in the hot and dry climate, this city has been chosen.

3. Materials and methods

The method used in this research is descriptive-analytical. There are more than one hundred valuable historical houses in Isfahan, which are registered as national heritage by Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts of Iran; Among these historical houses, thirty courtyard houses were selected as the case studies. The reasons that limited our choices to select the case studies through existing courtyards are as follows:

a) The land use of some of the registered courtyard houses was changed to other activities (under supervision of Isfahan Cultural Heritage Organization) and they have been converted into other land uses, such as restaurants, hotels, offices, educational and museums; b) Some of the registered courtyard houses were being under restoration process; c) Some of the private owners of registered courtyard houses were reluctant to let other people enter in their houses.

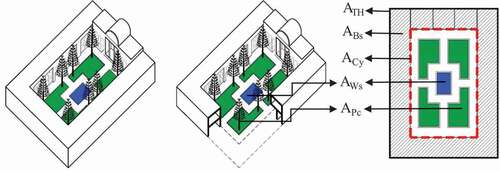

The location of the case studies and their deviation angle from the North were calculated using Google Maps. Based on field measurement of geometrical and natural parameters and existing documents, the courtyard houses were modeled in Autocad 2016 software. Statistical analyses were conducted to determine the size and ratio of geometrical and natural parameters and aspect ratios of the courtyards. Furthermore, linear equations and correlation coefficients are used to determine the relationship between the geometric and natural properties of courtyard houses. The studied geometric and natural parameters and their symbols are presented in .

Table 2. Geometric and natural parameters and symbols in studying the courtyards

4. Results

The geometric characteristics of the courtyards in the studied historical houses are surveyed in terms of orientation, dimensions and proportions of courtyard and walls, openings area and the ratio of natural elements in those houses. shows the geometric characteristics of the studied courtyard houses.

Table 3. Geometric characteristics of the studied courtyards (Source: Authors)

4.1. Orientation, dimensions and proportions

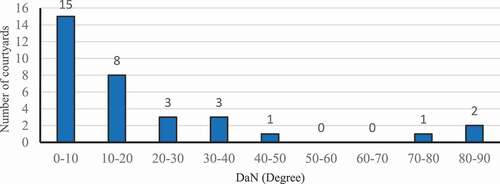

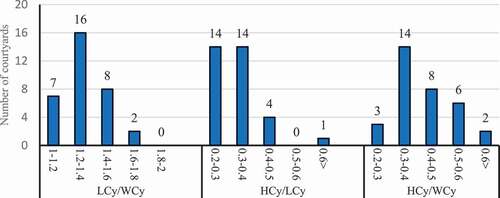

According to , the houses are located in SW-NE and SE-NW orientations. shows the deviation angles from the North in the studied courtyards. The deviation angle of about 45% of the courtyards are below 10° and about 25% are between 10°-20°. shows the length-to-width ratio of courtyards, which is between 1 and 1.8. The ratio between 1.2 and 1.4 has the maximum absolute frequency (49%) and the minimum frequency (6%) belongs to the range of 1.6–1.8. Also, the maximum frequencies of height to length and height to width ratios belong to 0.2–0.4 (84%) and 0.3–0.4 (42%), respectively.

Figure 3. The ratios of length/width, height/length and height/width in studied courtyards (Source: Authors)

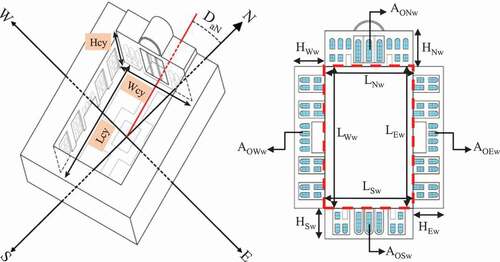

is a visual guide of the courtyard’s dimension, deviation angle, walls’ dimension and opening area. shows the dimensions and proportions of the courtyards’ walls in the studied houses.

Figure 4. Visual guide of: the courtyard’s dimension and deviation angle(Left), the walls’ dimension and opening area(Right)

Table 4. Dimensions and proportions of the courtyards’ walls (Source: Authors)

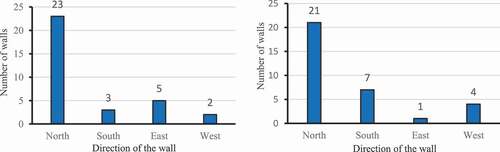

According to , the highest walls facing the courtyards are the North walls with a mean height of 6.296 m (57% frequency), and the shortest walls are the East walls with an average height of 4.98 m (15% frequency). According to and (Right), the highest ratio of height to length of the walls, respectively, belongs to the North walls with 64% frequency and 0.457 average ratio, the South walls with 21% frequency and the average ratio of 0.402, the East walls with a frequency of 3% and an average ratio of 0.315 and the West walls with 12% frequency and the average ratio of 0.325. According to and (Left), the maximum ratio of opening area to wall area, respectively, belongs to the North walls with a frequency of 70% and the average ratio of 45.4%, the East walls with a frequency of 15% and an average ratio of 35.9%, the South walls with a frequency of 9% and the average ratio of 26.5% and the West walls with a frequency of 6% and an average ratio of 31.4%.

Figure 5. Highest ratios of height to length among courtyards’ walls (Right), Highest ratios of opening area to wall area among courtyards’ walls (Left)

Table 5. Proportions of the opening area to the wall area in the studied courtyards (Source: Authors)

4.2. Courtyard and built spaces

The courtyard, as an open space, has proportionality with surrounding built spaces. shows the ratios of courtyard area to built space area and the total area of houses.

Table 6. Ratios of courtyard area to built space area in studied courtyards (Source: Authors)

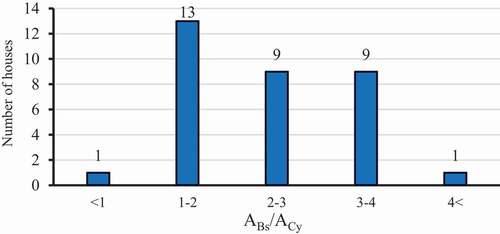

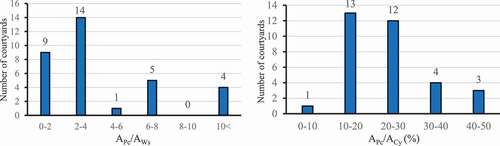

Based on the results of , it can be seen that the ratio of courtyard area (open space) to the total area in case studies is relatively between 20% and 50% and the ratio of built space area to the total area is between 80% and 50%. shows the proportion of built space area to courtyard area (ABs/ACy) in case studies.

According to , the ratio of built space to courtyard area (ABs/ACy) in courtyard houses is approximately between 1 and 4. In 40% of the cases, the ratio of ABs/ACy is 1–2, in 27%, is 2–3 and in 27% of the houses, the ratio is 3–4.

4.3. Water surface and plant coverage in courtyards

The proportion of natural elements such as water and plants (trees and green space) to the other components of spatial structure in courtyards of historical houses are demonstrated in . shows a visual guide of the areas of natural elements and built space.

Table 7. Ratios of water surface area and plant coverage area in studied courtyards (Source: Authors)

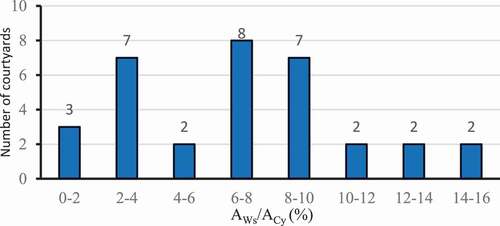

Based on and , the area allocated to water generally covers between 0% and 16% of the courtyard area in studied houses. In 70% of the case studies, water surface covers about 2%–10% of the courtyard area. The average ratio of the water surface area to the courtyard area (AWs/ACy) is about 7% in case studies.

According to (Right), the plant coverage area is about 1%–50% of the courtyard area. Among 76% of the houses, between 10%-30% of the courtyard area is occupied by plant coverage. The average of plant coverage area to courtyard area ratio (APc/ACy) is 22.1%. According to (Left), in 70% of the studied houses, the plant coverage area is about 1 to 4 times that of the area, which is covered by water. However, in houses with two courtyards, there may not be any water ponds or plants.

5. Discussion

In this study, the geometric and natural properties of 30 historical courtyard houses of Isfahan city in hot-arid climate were studied. The average results of the study are compared to other similar studies in cities with the same climate conditions.

This study demonstrated that the average of length/width ratio of the courtyards is 1.3. This finding is in line with the findings of Soflaei, Shokouhian, and Shemirani (Citation2016) in Isfahan, which reported that length/width ratio of the courtyards was 1.33, but it is different from the findings of Soflaei, Shokouhian, and Shemirani (Citation2016) in Kerman, Tehran and Mashhad cities with the ratios of 1.38, 1.16 and 1.09, respectively, and the findings of Zeinalian and Okhovat (Citation2018), in Yazd with the ratio of 1.45.

In this research, the average proportion of courtyard area to the total area of the house (ACy/ATH) is 31%. It differs from the results of Soflaei, Shokouhian, and Shemirani (Citation2016) in Isfahan, Kerman, Tehran and Mashhad cities, which determined that ACy/ATH ratios are 28%, 22%, 25% and 44%, respectively. Furthermore, it is dissimilar to the results of Zeinalian and Okhovat (Citation2018) in Yazd city, which reported that ACy/ATH ratio is 29%.

The average proportion of water surface area to courtyard area (Aws/ACy) in this research is 7% and the average proportion of plant coverage area to courtyard area (APC/ACy) is 22%. These results are different from the findings of Soflaei, Shokouhian, and Shemirani (Citation2016) in Isfahan, Kerman, Tehran and Mashhad cities, which reported that Aws/ACy ratios are 11%, 8%, 18% and 3% and the ratios of APC/ACy are 21%, 7%, 15% and 7%, respectively.

The average proportion of total openings’ area to total walls’ area of courtyards (ATOw/ATW) is 35%. This result differs from the findings of Soflaei, Shokouhian, and Shemirani (Citation2016) in Isfahan, Kerman, Tehran and Mashhad cities, which reported that the amount of ATOw/ATW ratios are 30%, 25%, 20% and 24%, respectively.

Comparing the mentioned previous research studies with this research, we come to the conclusion that the differences in the results (despite the same climate) are related to the following reasons:

a) The number of samples (each of previous studies had 3–5 cases); b) Different microclimates; c) The effect of other cultural and social features of different cities in the design of courtyard houses.

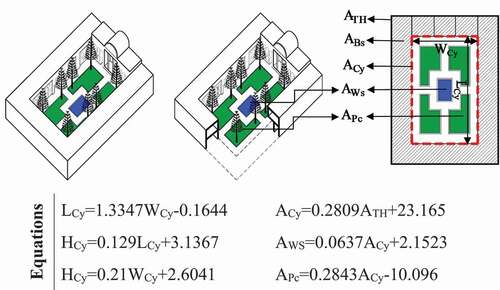

5.1. Relationships between geometric and natural properties of courtyards

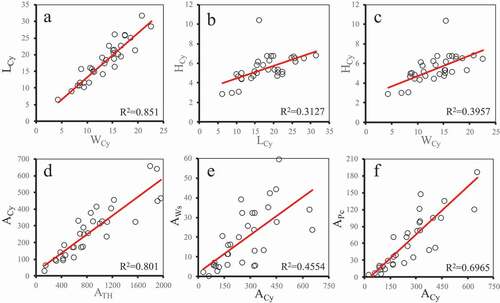

As final results, linear equations are presented for expressing the relationship between geometric and natural properties of courtyard houses in Isfahan city. The proportions of length, width, height, courtyard area, water surface and plant coverage could be used in designing contemporary courtyard buildings. and show estimated linear equations based on geometric and natural proportions of courtyards in Isfahan city.

Figure 10. Linear equations and R-squared value between geometric parameters of the courtyards, (a) length versus width, (b) height versus length, (c) height versus width, (d) courtyard area versus total area of house, (e) water surface area versus courtyard area, (f) plant coverage area versus courtyard area (Source: Authors)

Table 8. Estimated equations and relationships between parameters of the courtyards (Source: Authors)

Analyzing the correlation between geometrical and natural parameters of the courtyards resulted in some equations and the ratios of length/width, height/length and height/width that could be used as design guides for contemporary courtyards in hot-arid climate especially in Isfahan city. The ratios of length/width, height/length and height/width of the courtyards are 1.3, 0.3 and 0.4, respectively. The courtyard area covers about 31% of total area of the house and about 29% of courtyard is allocated to natural elements, 7% to water surface and 22% to plant coverage. The ratio of the opening area to the total area of the walls in North, South, East and West walls are 45%, 26%, 36% and 31%, respectively.

6. Conclusion

In this research, 30 historical courtyard houses of Isfahan city in hot-arid climate were selected as the case studies. Afterwards, geometric and natural characteristics of courtyards were surveyed and analyzed including orientation, dimensions and proportions of courtyard walls, opening area and natural elements (water surface and plant coverage). The findings of this study bring to light some linear equations between geometric and natural parameters of the historical courtyards in Isfahan city. As the first study of its kind, the findings of this study are presented in the form of some equations and ratios between length, width, height, courtyard area, water surface and plant coverage area of the courtyards; these findings can be considered as design guides by the architects in contemporary courtyard designs in hot-arid climate.

For the future studies, it is suggested that the relationship between the geometric characteristics of the courtyards and its microclimate behavior could be investigated. Furthermore, the exploration of geometric properties of the courtyards in other climates, along with recognition of their microclimate function, can help to prepare a climate-compatible architectural pattern for buildings in each climate.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hassan Akbari

Hassan Akbari graduated with a master's degree in 2002 and with a doctorate in 2012, both in Architecture and from the “Iran University of Science and Technology” (Tehran, Iran). He has been an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, since 2013. His research interests are in the field of building physics and the assessment and modeling of the environmental comfort of architectural and urban spaces.

Nazanin Niazi Motlagh Joonaghani

Nazanin Niazi Motlagh Joonaghani graduated from the “University of Mohaghegh Ardabili” (Ardebil, Iran) in 2018 in Architecture with a master's degree. Her research experience is within the field of optimizing energy efficiency in buildings.

References

- Ahmadi, Z. 2012. “Recognize the Missing Role of Central Courtyard to Achieve Sustainable Architecture.” Journal of Architecture in Hot and Dry Climate 2 (2): 25–40.

- Edwards, B., M. Sibley, P. Land, and M. Hakmi. 2005. Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and Future, New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Farahbakhsh, M., P. Hanachi, and M. Ghanaei. 2018. “Typology of Historical Houses in the Old City Fabric of Mashhad, from the Early Qajar to the Late Pahlavi I Era.” Journal of Iranian Architecture Studies 6 (12): 97–116.

- Hedayat, A., and S. M. Tabaian. 2016. “The Survey of Elements Forming Houses and Their Reasons in the Historical Fabric of Bushehr.” Journal of Architecture in Hot and Dry Climate 3 (3): 35–52.

- Khakpour, M., M. Ansari, and A. Tahernian. 2010. “The Typology of Houses in Old Urban Tissues of Rasht.” HOnar- Ha- Ye- Ziba Memari- Va- Shahrsazi 2 (41): 29–42.

- Mahdavinejad, M., M. Mansorpoor, and M. Hadianpoor. 2014. “Courtyard Phenomena in Contemporary Architecture of Iran; Case Studies: Qajar and Pahlavi Era.” Journal of Studies on Iranian- Islamic City 4 (15): 35–46.

- Moradi, S., M. Matin, and M. Dehbashi Sharif. 2018. “Typology of Tabriz Traditional Courtyard Houses Based on Physical Criteria Related to the Climatic Performance of the Central Courtyard.” Urban Management 17 (51): 87–106.

- Peel, M. C., B. L. Finlayson, and T. A. McMahon. 2007. “Updated World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007.

- Ghasemi Sichani, M., and G. Memarian. 2010. “Typology of Ghajar Era House in Isfahan.” Hoviatshahr 4 (7): 87–94.

- Rokni, N., and V. Ahmadi. 2017. “Analyze of the Hidden Spatial System of Residential Vernacular Architecture of Mashhad, Based on the Theory of Space Syntax.” Journal of Greate Khorasan 7 (26): 39–58.

- Shahzamani Sichani, L., and M. Ghasemi Sichani. 2017. “Analysis of the Structure of the Plan of the Pahlavi’s House of Artists (Mohtashmi) of Isfahan Based on the Gestalt Rules.” Urban Management 16 (48): 461–470.

- Soflaei, F., M. Shokouhian, and S. M. M. Shemirani. 2015. “Investigation of Iranian Traditional Courtyard as Passive Cooling Strategy (A Field Study on BS Climate).” International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 5 (1): 99–113. doi:10.1016/j.ijsbe.2015.12.001.

- Soflaei, F., M. Shokouhian, and S. M. M. Shemirani. 2016. “Traditional Iranian Courtyards as Microclimate Modifiers by considering Orientation, Dimensions, and Proportions.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 5 (2): 225–238. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2016.02.002.

- Soheili-fard, M., H. Akhtarkavan, S. Fallahi, M. Akhtarkavan, and A. Mohammad-moradi. 2013. “Examine the Interaction of Traditional Iranian Architecture Principles in Terms of Form, Orientation and Symmetry to the Solar Energy, Case Study: Abbasiyan House in Kashan.” Armanshahr Architecture & Urban Development 6 (11): 75–90.

- Soltanzadeh, H. 2011. “The Role of Geography on Formation Courtyards in Traditional Houses in Iran.” Human Geography Research 43 (75): 69–86.

- Soltanzadeh, H., and M. Ghaseminia. 2012. “Typology Study of the Physical-functional Structure of Residential Architecture in Golestan Province.” Armanshahr Architecture & Urban Development 4 (7): 1–15.

- Zeinalian, N., and H. Okhovat. 2018. “Morphology of Courtyard in Qajari Houses in Hot-dry and Hot-humid Climates, with a Focus on the Species of “Courtyard in the Middle”; Case Study: Yazd and Dezful Houses.” Journal of Studies on Iranian- Islamic City 8 (30): 15–29.