ABSTRACT

This research examines the origins of Korean modern architecture within the context of cultural encounters between the East and West in terms of modernity, and in comparison with the origins of modern Western architecture. This research examines the works of two pioneering and representative Korean modern architects: Gilryong Park (朴吉龍, 1898–1943) and Dongjin Park (朴東鎭, 1899–1981), who actively designed architecture during the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945). When these two representative Korean modern architects led the movements toward modernity, adapting traditional architecture was a key factor in their philosophy of modern architecture. However, they had different approaches to inheriting tradition and interpreting modernity. Considering these two architects as case studies, this research demonstrates that early modernism in Korean architecture was entangled with and struggled between Western modernism, Japanized modernism, and traditional Korean architecture. This research provides a significant and unique case study of the cultural encounters between Korean, Japanese, and Western architecture in the early 20th century. This research enables the discovery of the identity of early Korean modern architecture through its evolution from tradition to modernism by considering the social and cultural contexts and comparing it with modern Western architecture.

1. Introduction

East Asian architecture experienced intense conflicts and continuities between tradition and modernity from the mid-19th century, when Western powers established colonies in East Asian port cities. Korean modernism evolved within the context of Japanese colonization during the first half of the 20th century. After Japan annexed Korea by means of the Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty (韓日倂合條約 or Japan’s Annexation of Korea) in August 1910, modernism in Korean architecture developed along a different track from that of China and Japan. Although the principles of Korean modern architecture seemed to be based on international modernism, its development was differentiated due to influence of Japanese modernism on Korean modernism. Korean modernism also strongly interacted with Korean tradition. Korean modernism not only emerged from the conflicts between tradition and modernity, as was the case in other East Asian countries, but it was also influenced by both Japanized and Western modernism.

The objective of this research is to investigate the characteristics of Korean modern architecture in the early 20th century through comparing modern architects and architecture and examining the cultural encounters between the East and West in terms of modernity. The discovery of the influences that are mutual between tradition and modernism and between East and West will help us embrace other cultures in architecture and enhance the value of modernism in Korean and Western architecture. Modern architecture can create a synergistic effect through the influx of other cultures, and this research will shed light on the modern history of Western and Eastern architectural encounters.

To discover the nature of modernism in Korean architecture, this research focuses on the following aspects. First, this research investigates the relationships between tradition and modernity in the early modern times in Korea. This study explores not only Korean modern architecture but also the culture, science, technology, and more to clearly articulate the context of Korean modernity in the early modern times. Second, tradition and modernism of Korean architecture in the early 20th century is compared in this study through examining the work of two pioneering and representative modern Korean architects: Gilryong Park (朴吉龍, 1898–1943) and Dongjin Park (朴東鎭, 1899–1981), who practiced architecture in the early 20th century. This research enables the exploration of conflicts and continuities from tradition to modernity in early Korean modern architecture by considering the social and cultural contexts and comparing early Korean modern architecture with Western architectural culture.Footnote1

This research employed the methodology of comparative research wherein the works of the two representative modern architects in Korea, Gilryong Park and Dongjin Park, are compared to accomplish the research objective. Comparative research is useful to practically understand and interpret the cultural interactions between the East and West (Zou Citation2012, 273–276). The two aforementioned architects had different perspectives toward the notions of tradition and modernity. The uniqueness and value of the works of every architect becomes more salient in the presence of the works of other architects. Naturally, the problems arising from the introduction of such juxtaposition while conducting this comparative research should be taken into account. Additionally, comparing the abovementioned two architects that seemingly contradict each other might pose the possibility of the comparison’s deviation from reality. However, according to Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), such contradictory characteristics of the subjects might facilitate the process of elucidating the subjects’ true essence (Heidegger Citation1977, 111–138). When it comes to reconciling tradition and modernity, these two architects have seemingly contradictory attitudes at times. As Heidegger addressed the meaning of paradoxa, which is the Greek concept, in his essay “On the Essence of Truth,” the essence of truth can be reached through the paradoxical phenomenon (Heidegger Citation1977, 131). Although paradoxa is abnormal and contradictory to our everyday life, it can help us discover the essence of true life because paradoxa has a potential to open up the essence of truth, allowing us to reach and maintain the deep complexity of a poetical life. Thus, comparing the abovementioned two architects will clarify the uniqueness and characteristics of each architect.

2. Discourses about modernity in architecture

The meaning of the term “modern” is ambiguous. It refers to the present or to a recent time and is also used as a label for contemporary styles. In humanities research, it is related to the period in history from the end of the Middle Ages until the present. The concept of “modernity” appeared first in the 18th century in Western Europe through major events such as the French revolution (1789–1794), the industrial revolution in England (mid-18th century), and the Age of Enlightenment (Swingewood Citation1970, 164–180). The idea of modernity subsequently spread to other parts of the world and is understood in different ways by various writers and critics. Our contemporary notions of modernity are often related to “the Enlightenment, rationalism, citizenship, individualism, legal-rational legitimacy, industrialism, nationalism, the nation-state, the capitalist world-system, and so on” (Shin and Robinson Citation1999, 9).

In architecture, the terms “modern” and “modernity” are used to signify various movements that occurred in the 20th century. These terms indicate functionalism, which includes a combination of aesthetic ideas that evolved from historical precepts and styles. The phrase “modern architecture” is ambiguous as well. A controversy still exists over the delineation of the beginning of the period of modern architecture. Alan Colquhoun, a modern architectural historian, stated that “it [modern architecture] can be understood to refer to all buildings of the modern period regardless of their ideological basis, or it can be understood more specifically as an architecture conscious of its own modernity and striving for change” (Colquhoun Citation2002, 9). Colquhoun has a broader understanding and definition of modern architecture that is not limited to specific movements that demonstrated radical changes. The architectural historian Peter Collins expanded the definition of modernism in his following statement: “Yet influential as these economic factors eventually proved to be, the immediate source of the changes in architectural ideas was philosophical, and stemmed primarily form a new kind of awareness which we may call the awareness of history” (Collins Citation1965, 30). Thus, he relates the inception of modern architecture to the radical alteration in Western society in the late 18th century, a phenomenon also associated with the emergence of the social sciences. Collins’s definition of modernism was thus understood in terms of cultural and philosophical changes rather than in terms of material and technical innovations. Kenneth Frampton stated that if the revelation of modernity was the origin of modern architecture, the origin of the concept of “modernity” can be traced back to the mid-17th century when architects questioned the classical principles of architecture outlined by Vitruvius (Frampton Citation1992, 8). In particular, the architectural theorist Hilde Heynen argued that modern society has been visualized at various levels and that modernization, modernity, and modernism must be distinguished in this respect (Heynen Citation1999, 10). Modernization is used to describe the major characteristics of the process of social and cultural development, such as technological advancement, industrialization, urbanization, population growth, introduction of bureaucracy, the rise of a strong single-race nation, enormous expansion of mass media system, democratization, and expansion of capitalism in global market. In the 20th century, the entire social process that enables such a change and maintains this state continuously was designated as “modernity” (Berman Citation1988, 16). Modernity represents the continuous process of development and change; in other words, it is the attitude of life towards the future that would be different from the past or present.

At some point during the first half of the nineteenth century an irreversible split occurred between modernity as a stage in the history of Western civilization-a product of scientific and technological progress, of the industrial revolution, of the sweeping economic and social changes brought about by capitalism- and modernity as an aesthetic concept (Călinescu Citation1987, 41; emphasis added).

Thus, modernity is the word that refers to new features and phenomena that appear different compared to pre-modern times. The values that did not exist before or were not important have begun to penetrate into the modern life. The concepts we are familiar with today, such as hygiene, efficiency, and science, are all phenomena that have emerged in modern times (Frederick Citation1913, 3–13, Citation1920, 8). These values affected the modern lifestyles and residential spaces, and they still do. In this respect, this paper examines how these modern ideas emerge in the architecture of Gilryong Park and Dongjin Park, given the framework of modernity.

3. Two Korean modern architects: Gilryong Park and Dongjin Park

Gilryong Park (1898–1943) and Dongjin Park (1899–1981) are two representative Korean modern architects who tried to integrate the influences and characteristics of Western modernism into Korean traditional architecture (). During the Japanese colonial period, most of the modern buildings in Korea were designed by Japanese architects and Western architects. Gilryong Park and Dongjin Park were the first generation of Koreans who received a modern architectural education in Korea, and they actively practiced buildings embodying Korean modern architecture influenced by Western modernism in the early 20th century. These two architects were the representative architects who experienced the conflicts between modernism and tradition in modern Korean society and who contributed extensively to the development of modern Korean architecture.

3.1. Historical background of Gilryong Park

Gilryong Park graduated from Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School in 1919, which was founded in 1916. It was later renamed Gyeongseong High Industrial School in 1922.Footnote2 Park was the second graduate of this school and the first graduate of its architectural department. The purpose of offering architectural education in this institution was to increase Japan’s national power (國力) in competitive engineering education. In the 1910s, Japan aggressively expanded its national power and needed individuals with technical skills to support its growing power. Thus, institutions offering technical training were constructed in Korea to strengthen Japan’s hold over Korea. Many Japanese architects and engineers were educated in Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School. Even though this was the only architecture school in Korea at that time, most of its students and faculty were Japanese.

Korean students were restricted from obtaining education from Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School and Gyeongseong High Industrial School. These schools were only allowed to accept a small number of Korean students, and very few of these students became professional architects. For instance, statistics revealed that for the students who enrolled in Gyeongseong High Industrial School from 1919 to 1935, each year only zero to two Korean students (three in 1926) were admitted to the school (Ahn Citation1997, 14).Footnote3 Considering the ratio of Korean to Japanese individuals who lived on the Korean peninsula at that time, this small ratio reflects the challenges faced by Korean students to acquire education. Even though few Koreans enrolled in this school, only a small percentage of these students completed their education. For example, in 1929, there were 41 students in the architecture department. Among these students, only three students were Korean (Kim Citation1982, 64). This institute was mainly designed for Japanese citizens who lived in Korea. In the 29 years the institute remained operational, only 60 Korean students graduated from the school. Gilryong Park and Giin Lee were the first Koreans who graduated from this school in 1919. Lee was interested in the engineering aspects relating to architecture, such as structural design, and did not practice as actively as Park. After graduating in January 1919, Park worked for the Japanese Government-General of Korea (朝鮮總督府) as an engineer from January 1921 to July 1932. In 1932, he opened his architectural design firm, Park Gilryong Architectural Design, in Jong-ro (the central area of Seoul), and this was the first Korean architectural firm managed by a native Korean ().

Figure 3. An exterior view of Gilryong Park’s architectural design office in the 1940s.

Moreover, Gilryong Park played an important role in the architecture of Joseon during the Japanese colonial era.Footnote4 While he practiced in Gyeongseong (the former name of Seoul from 1910 to 1945), he actively participated in various organizations not only in the architectural field but also in fields of arts and sciences. In particular, Park was deeply interested in the Science Promotion Movement. He proactively participated in activities led by various scientific organizations during the Japanese colonial period, including the Society of Inventions (established in 1924), the Society For the Diffusion of Scientific Civilization (founded in 1924), the Korea Inventions Association (founded in 1928), the Society of Joseon Engineering (founded in 1929), and the Society of Diffusion of Scientific Knowledge (established in 1934) (Woo Citation2001, 81–88). He became the chairman of the Society of Inventions among the board of directors, which played a significant role in introducing the concept of “science” to Korean citizens through the magazine Science Joseon (科學朝鮮) published from 10 June 1933 (Hyeon Citation1977, 270). The Society of Inventions was the first organization that promoted scientific education and development. It was founded in 1924, and it soon dissolved despite the efforts of Yongkwan Kim (1897–1967). In 1932, the organization resumed its activities, and Park was elected as the chairman of the organization (Lee Citation2019, 74). Park’s participation in diverse scientific movements greatly impacted his architectural philosophy.

Park’s works were praised by his fellow architects, including Japanese architects. In 1940, the magazine Green Flag (綠旗) published a laudatory article regarding Park’s architectural designs, commenting that “His [Gilryong Park’s] architectural practice bloomed, as we can see that he designed houses one after another every three days” (Green Flag Federation Citation1940, 87). After Park’s death, the magazine Joseon and Architecture (朝鮮と建築)Footnote5 published a special issue in May 1943 to honor his memory; this issue was titled “Park Gilryong Memorial (故朴吉龍君追悼記)” (Association of Joseon Architecture Citation1943, 13–22). In this issue, many of Park’s Japanese colleagues, such as Keiichi Sasa, Shigeo Kasai, Jukura Imazu, Toshio Kanaoka, Takeo Osumi, Yoshiyuki Kanaya, and others wrote articles detailing Park’s achievements. It was very rare for a magazine in that period to publish a special issue dedicated to a Korean architect. In particular, the Japanese architect Keiichi Sasa, who was an architect in the architectural department at the Japanese Government-General of Korea and who also actively practiced in Joseon, commented the following:

After Park opened his architectural design firm[in 1932], he produced excellent architectural designs and became a role model for other [architects] because of his design capability, working attitude, knowledge, intelligence, credibility, companionship, effective management, etc. He executed various projects including department stores, schools, offices, stores, houses, and significant buildings in Seoul. In particular, he designed many retail stores. Thus, he had a high credibility among businessmen. Park was also interested in some special fields in Korean architecture. He had a deep understanding regarding the improvement of the ondol system [the Korean underfloor heating system] and housing reform in Joseon in the modern age (Association of Joseon Architecture Citation1943, 15; emphasis added).Footnote6

Jukura Imazu, a Japanese architect who practiced in Korea in the early 20th century, also commented, “He [Gilryong Park] is the top and very unique Korean architect who practices actively in Korea as a native Korean during the Japanese colonial period” (Association of Joseon Architecture Citation1943, 16).Footnote7 These comments show that Park was considered to be a highly influential architect by Japanese architects and that Korean and Japanese architecture magazines appreciated his deep knowledge regarding traditional Korean architecture and his endeavors of integrating the ondol system (Korean traditional underfloor heating system) into the modern Korean house design.

Park designed different types of buildings in Gyeongseong.Footnote8 He exemplified modern architectural ideas using modern materials such as reinforced concrete and bricks, and introduced modular systems into the design of Korean houses, which were not typical in traditional Korean houses. In particular, he was deeply interested in the Housing Improvement Movement. After he established his “Park Gilryong Architecture Firm,” he established “The Research Association for Traditional Houses of Joseon” with his alumni from Gyeongseong High Industrial School (Lee Citation2019, 78). This association intended to propose house improvement plans relating to the different aspects of the lives of Korean people and to actively provide consulting services and publish articles.Footnote9 In addition to publishing articles in diverse media channels including newspapers and magazines, and writing books, he was involved in various activities, such as participating in radio programs and making speeches to share his ideas on architecture with the public. In particular, Park published the following two books: On Dwelling Reform of Traditional Housing, no.1 (在來式 住家改善에 對하야: 第一編, self-published, G. Park Citation1933) and On Dwelling Reform of Traditional Housing, no.2 (在來式 住家改善에 對하야: 第二編, Yimundang, G. Park Citation1937). In these books, Park compiled his ideas relating to the improvements of traditional Korean housing. In the first half of the first volume, by means of 12 different topics, he organized his overall thoughts on traditional Korean housing improvements (G. Park Citation1933, 1–28).Footnote10 The latter half is comprised of multiple floor plans, sectional plans, and three-dimensional illustrations. The second volume focuses on enhancing the ondol system. This volume comprised of improvements regarding each part of the ondol system by using floor plans, elevation plans, three-dimensional illustrations, etc (G. Park Citation1937).Footnote11

3.2. Historical background of Dongjin Park

Along with Gilryong Park, Dongjin Park is considered as a representative of the first generation of Korean architects in the early 20th century (Lee Citation1990, 149–157; Yoon Citation1996, 80–84; AhnCitation1997; SeoCitation2017, 263–270; Kim Citation2018, 214–233). Dongjin Park majored in architecture in Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School and Gyeongseong High Industrial School between 1917 and 1926.Footnote12 After he took part in the March 1st Movement during the Japanese colonial period, he was imprisoned for 6 months for getting involved in the movement and was expelled from Gyeongseong High Industrial School. Later, he reenrolled in Gyeongseong High Industrial School in 1924 and graduated in 1926. Similar to Gilryong Park, Dongjin Park also worked for the Japanese Government-General of Korea as an architect technician after his graduation.Footnote13

An investigation of Dongjin Park’s architectural education can deepen one’s understanding of his architectural philosophy. In Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School, during 1917 and 1918, he studied Western architecture, lectured by a group of professors who had studied architecture as fine arts (Ryu Citation1992).Footnote14 At this school, Japanese faculty members taught the following courses: History of Architecture, Building Material, Architectural Structure, Military Drill, Architectural Design, Stereotomy, Moral Cultivation, Act and Conduct Rules, Applied Mechanics, Construction of Houses, and Construction Design (Ahn Citation1997, 28–30).Footnote15 In the course of Architectural History (建築史), the printed materials offered to students were similar to those used in Imperial University in Tokyo. This was because some of the abovementioned Japanese faculty members graduated from Imperial University and moved to Gyeongseong in the early 20th century. At Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School, some courses were strongly related to Japanese culture. Some of these courses were Moral Cultivation and Act and Conduct Rules. These courses were included in the curriculum even though they were not directly related to architectural education as Japan wanted to enforce its imperialistic philosophies and ideas on Korean students. Due the contents of these courses, the Korean students were inevitably influenced by Japanese ideologies and Japanese methods and concepts of architecture directly and indirectly.

When Dongjin Park reenrolled in Gyeongseong High Industrial School in 1924, the education he received revolved primarily around engineering aspects of architecture. This was because Gyeongseong High Industrial School was more influenced by the Japanese education system which prioritized engineering over aesthetics when it came to architecture. At that time, Japan strived to develop into an imperialistic modern country, and there was a strong need to foster architects with a thorough knowledge of the engineering aspects of architecture who could actualize these imperialistic objectives. Thus, Park gained knowledge related to architecture by taking engineering-focused courses.Footnote16 Moreover, after graduation, he acquired practical knowledge and experience by working for the Japanese Government-General of Korea. On 30 October 1940, he resigned from his position at the Japanese Government-General of Korea. However, he had already commenced working on his own projects. From the mid-1930s, he started designing buildings that were based upon Western modernism.Footnote17 He also designed buildings of diverse styles that extensively adopted elements of both modern and traditional architectural styles including gothic architectural style (Seo Citation2017, 264).Footnote18

Until the 1920s, modern architects including Dongjin Park acquired architectural knowledge related to Western modernism by means of a magazine called Joseon and Architecture, books written by Western authors, and through conferences or lectures, rather than via direct education received from schools such as Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School (1916–1922) and Gyeongseong High Industrial School (1922–1945) (Kim Citation2018, 216–218). After 1934, there was an increase in the number of educational materials on modern Western architecture available in these institutions. From the book series the Advanced Study of Architecture (高等建築學), the volume of architectural history was used as a reference in Gyeongseong High Industrial School.Footnote19 Thus, any student could easily access the book for reference in Gyeongseong High Industrial School, and students began to have more opportunities to explore Western architecture. For instance, the second volume of this book series, Eastern and Western Architectural Styles (西洋東洋建築樣式, Oka Citation1935), introduced Le Corbusier in the chapter on modern architecture (Oka Citation1935, 335–337; Kim Citation2018, 218). Thus, although the content in these books was not detailed in nature, the architects who were leading the modern Western architecture at the time were directly and indirectly being introduced to Korean students.

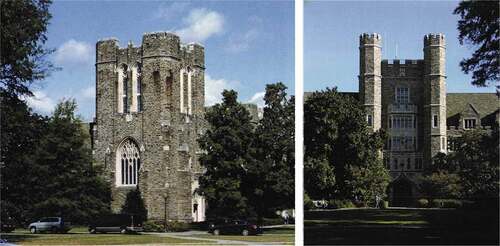

From among the many buildings designed by Dongjin Park in the 1930s, the Bosung College Main Building (1934) and Bosung College Library (1937) are the representative architectures to understand his architectural styles and ideas ().Footnote20 These buildings have historic implications as they were built by a Korean architect during the Japanese colonial period, and as they were the most critical buildings of Bosung College (later Korea University), which aspired national historical science, and the buildings had granite gothic motives with sophisticated decoration details (Kim Citation2012, 47). The Bosung College Main Building and Bosung College Library were influenced by the design of an American college campus. Especially, when Park was designing the Bosung College Library, he seemed to see a brochure of Duke University in the US which a professor at Bosung College, Chun-suk Auh (1901–1987) possibly had (Kim Citation2012, 55). Therefore, Park probably used this brochure as reference material while designing the campus of Bosung College. Specifically, the Bosung College Library was modeled after several buildings in Duke University, including the library building, which is now called Perkins Library, the medical school building, which is now called Davidson Building, and The Union building ().Footnote21 Furthermore, the façades of the Bosung College Main Building (1934) and the Bosung College Library (1937) were of granite, and the use of granite added an aura of dignity and stability to the buildings.

Figure 4. Three-dimensional drawing of the new Bosung college Main Building to be built.

Figure 5. Photos of Perkins library (Left) and Davidson building (Right) of Duke University by Horace Trumbauer, 1930s.

The most crucial literature to understand Dongjin Park’s architectural philosophy is his work About Our Houses (우리 住宅에 對하야), containing 16 essays, which he published from 14 March 1931 to 5 April 1931.Footnote22 In these essays, he introduced architectural movements, architects, and significant modern buildings in Europe, sharing his insights on the trends of modern architecture. Additionally, he proposed concrete ideas to enhance traditional Korean houses. Although the depth was somewhat lacking by the current standards, Dongjin Park attempted Western modernism architecture since the 1930s. Furthermore, he believed that traditional Korean housing should adopt elements of modern Western architecture for an enhanced quality of life of Korean citizens.

4. Gilryong Park’s interpretation of tradition in building modernityFootnote23

Gilryong Park was the architect who received a modern education and one of the first generation of Korean who established an architectural design firm in Gyeongseong, Korea. He designed various types of buildings, and his Western style houses especially expressed his modern ideas. He integrated modern Western architectural doctrines such as “rationality” and “functionality” with the Korean traditional housing system known as hanok, and attempted to renovate traditional dwellings by integrating Western features for enhance the comfort and lifestyle of the residents. In order to actualize his ideas, he promoted the Housing Improvement Movement and intended to build Korean modernity through this movement (Seo Citation2014, 403).

Although the overall elements of Park’s architectural designs such as structure and materials were derived from modern Western architecture, the specific characteristics of hanok and the general ambience of modern houses designed by him initiated from traditional Korean housing. His fundamental philosophy and thoughts about the housing trends in Joseon of that period were clearly discerned in his 1941 article “Thoughts on Joseon Housing (朝鮮住宅雜感)” in Joseon and Architecture:

When it comes to talking systematically about the recent housing trend in Joseon, there are two types of architectural styles in Joseon. First, traditional Joseon architecture adopts elements of Japanese or Western style architecture. Second, Western or Japanese architectural style combined with the traditional Joseon architectural style results into an eclectic architectural style. The former structure and style of Joseon architecture is traditionally Korean, and the plan discarded the “L” shape Courtyard Housing Plan [traditional design]. It adopted the Centralized Housing Plan which retains the corridor and entrance of the traditional design. Additionally, it incorporated the ondol system under the floor of the room and included the installation of Western style windows. While the latter [The structure and exterior of the Centralized Housing Plan were in Western style] escaped the traditional Joseon style in its structure and exterior, but rather they were Western style. The maru (wooden floor) in living rooms incorporated the ondol system, and the windows were of the Joseon style. Even though the general atmosphere is Joseon style, in the case of one room, it is installed with the Japanese style room (a room with a tatami floor [a wood floor covered with tatami mattresses]). Either way, the combination is not well harmonized in the Korean context. Anyhow, traditional Korean housing has many deficiencies. We need to abandon it, and attempt to design a new housing style (G. Park Citation1941b, 15; emphasis added).

Park recognized the problems pertaining to traditional Korean architecture, especially housing. He criticized the traditional housing style in Joseon and believed that it was insufficient for the lifestyles of that generation. However, he advocated using the ondol system of traditional houses in new houses in Korea. He insisted the preservation of the ondol system as a heating method and installed this heating method in each room of the houses designed by him in order to respect the traditional lifestyle of inhabitants (Kim Citation2011, 69).

Along with conducting research on houses in Joseon, in the 1930s, Park, who participated in various science movements, was mainly concerned with the design of the kitchen and the ondol system in traditional Korean housing. However, for reforming the kitchen and the ondol system, there was a need to change the arrangement of the houses. In his book, On Dwelling Reform of Traditional Housing, no. 1, published in (G. Park Citation1933), Park compared the “Jungjeongsik (Courtyard Housing Plan)” and “Jipjungsik (Centralized Housing Plan),” and addressed the need to focus on the centralized housing plan, which was a version of a reformed courtyard housing plan, and which respected the elements of traditional Korean housing. In his sketches, he analyzed the movement of people in each of these two plans (). He stated the following regarding this comparison:

Traditional (Jungjeongsik) building plans were originally built based on the idea of connecting the rooms through passages. Thus, the courtyard space could not be allocated to a garden. Additionally, whenever moving across different rooms, the inhabitants need to wear shoes. This is an inconvenient format for Koreans who generally take off their shoes indoors. The residential behaviors in traditional houses are rather restricted and inefficient. The centralized housing plan does not force the necessity of having to wear shoes when moving from one room to another, and it is also more efficient as compared to the traditional Korean housing (G. Park Citation1933, 2; emphasis added).

Park negatively viewed the “Courtyard Housing Plan” of the traditional hanok and insisted on integrating housing improvement elements in the traditional hanoks. In his article “Thoughts on Joseon Housing,” he sketched both the traditional “Courtyard Housing Plan” of the hanok and the new and improved “Centralized Housing Plan” to show the advantages of the latter () (G. Park Citation1941b, 16). Comparing these two plans through these sketches, he criticized the traditional Korean houses in terms of different aspects, such as the “inconvenient” floor plan, “uselessness” of the courtyard, poor ventilation, short lighting conditions, and inefficient fire safety in the rooms, particularly the crowded living quarters in urban area (G. Park Citation1941b, 15–18). While he insisted that Korea adopt the Centralized Housing Plan in the future, he also proposed improvements for both the Courtyard Housing Plan and the Centralized Housing Plan (G. Park Citation1933, image no. 11 &13).

Figure 7. Gilryong Park, sketch of the centralized housing plan (Left) and the courtyard housing plan (Right).

Individual rooms in traditional houses such as the bedrooms, living room, kitchen, or kitchen were not linked to each other. However, these spaces were enclosed in a courtyard called Madang. Park considered this layout inconvenient and inefficient, and for these reasons he proposed the Housing Improvement Theory, which primarily included the Centralized Housing Plan (). Compared with the Courtyard Housing Plan, his Centralized Housing Plan concentrated on the efficient use of the site. The Centralized Housing Plan was identified by a central corridor; the living room of the housing and most of the other rooms faced south, and the kitchen and toilet faced north. This layout of the housing plan created a more efficient and natural flow pattern between the rooms. However, he retained the ondol system in the Centralized Housing Plan to respect the traditional lifestyle of the inhabitants (Kim Citation2011, 69).

Park believed that some facilities in traditional houses, such as the toilet and kitchen, were vulnerable to sanitation and hygiene problems, and determined to improve the sanitation and hygiene in these spaces. He particularly focused on the issue of poor sanitation in the kitchen in traditional houses, which was traditionally situated outside the main structure, and placed the kitchen inside the house in the improved model. He also tried to improve the functionality of the house by integrating improved equipment systems that were not used in traditional houses. These modifications helped solve the sanitation and hygiene problems in traditional houses, and also enhanced the efficiency of the use of spaces.

Thus, Park began to explore the possible improvements relating to kitchens in traditional Korean houses. In August 1932, he published a series of six articles in The Dong-A Ilbo, titled “About the Kitchen (廚에 對하야).” He believed that the kitchen is the most important space in traditional Korean houses because perfect cooking techniques and well-equipped kitchen facilities are important factors to sustain our living and life (G. Park Citation1932a, 4). Thus, he encouraged the public to reform the kitchen for the sustenance of life and for improved sanitation, an important issue in early 20th-century Korea.

Park analyzed different types of kitchens in different areas of Korea, including the Hamheung area in northern Korea and the Gyeongseong area in the central Korean region. Regarding a kitchen in a house in the Hamheung area (), he argued that the kitchen was very efficient as it connected to all the rooms in the house, and the fireplace in the kitchen could heat all the rooms at the same time. In Korea, as the ondol system was commonly used for heating the house, the abovementioned model presented an efficient way to heat the entire house by means of the fireplace in the kitchen as the kitchen was connected to each room in the house. He stated the following regarding this model: “At a glance, it is very convenient because there is no need to make extensive structural changes to incorporate the ondol system. Therefore, the design of the kitchen in the Hamheung area is very efficient” (G. Park Citation1932a, 4).

On the other hand, Park criticized the traditional kitchen in the Gyeongseong area. He stated that this kitchen was poorly designed because many kitchen facilities were located in inaccessible places, the shape of the kitchen was narrow, and there was insufficient natural light (G. Park Citation1932b, 5). He also criticized traditional Korean facilities related to kitchen, including a cupboard shelf, a platform for placing crocks of sauces and condiments (Changdoktae), etc. (). He believed that such traditional kitchens hindered the Korean public from developing new kitchens. He also thought that the modification of the kitchen facilities would increase the efficiency of kitchen utilization. Therefore, he advocated the redesigning of traditional Korean kitchen facilities to overcome the flaws related to these kitchens.

Park published an article titled “The Need for Improvement (改善의 必要)” in The Dong-A Ilbo in August, 1932. Through a layout of a traditional Korean kitchen, he showed that the kitchen was not connected directly to the other rooms in the house, and that this inefficient connection between the kitchen and other rooms leads to discomfort among the inhabitants of the house (G. Park Citation1932c, 5). In his discussion of the improvement of kitchen spaces, he focused on “efficiency” of kitchen utilization because housewives spent a considerable time in kitchens. His analysis of traditional kitchen spaces also focused on “hygiene” because kitchens produce the food consumed by people in their everyday lives. Moreover, he was interested in improving traditional kitchens’ lighting and ventilation systems. His emphasis on improving these systems was based on the reason that imperfect lighting and ventilation in traditional Korean kitchens led to poor sanitation. Due to poor sanitation, traditional Korean kitchen spaces by were often infected by pathogenic bacteria (G. Park Citation1932c, 5). He believed that better lighting and ventilation systems would enable kitchens to become more hygienic spaces.

After highlighting the problems of traditional kitchens, Park suggested changes to enhance the efficiency of traditional kitchens and also incorporated his suggestions in his designs of kitchens. In some samples of his private house designs, he positioned the kitchen next to the maru, where people spent most of their time and whose function is very similar to that of a living room (). He located the fireplace next to the room in which the ondol was installed and inside the kitchen to enhance the efficiency of the ondol system.Footnote24 For improving the ventilation and lighting in kitchens, his kitchen models always faced south; it is the best orientation for the kitchen because when kitchens face south, they get a lot of light during the day (G. Park Citation1932d, 5). However, he also considered east-facing kitchens to be acceptable in the case of a south-facing kitchen hampered the relationship between the other rooms in the house. Whenever Park designed buildings, he focused on enabling direct connections between the kitchen and the other rooms in the house. In Korean houses, the kitchen should connect to other rooms in the house because Koreans use the ondol system for heating the house, a major difference between Western and Korean kitchens: Thus, he stated the following relating to the use of the ondol system:

It is necessary for houses in foreign countries to connect the kitchens to the servants. However, in traditional Korean houses, we use ondol as a heating system. Thus, kitchens should be positioned next to the other rooms in the house in order to use the fire tunnel[for easy functioning of the ondol system]. Kitchens should always be located in such a way so as to directly connect to other rooms in the house (G. Park Citation1932d, 5; emphasis added).

On August 13 and 14, 1932, Park published his designs that included the reformed kitchen facilities in The DongA-Ilbo based on his previous designs (G. Park Citation1932e, 5; G.Citation1932f, 5). He included Western style facilities in these kitchen designs (). His kitchen designs included a sink, a pantry, a cupboard, a stove, an exhaust pipe, etc. – all of which were present in Western kitchens. These facilities and furniture represented a modern kitchen, and he encouraged people to use these modern facilities as the Korean people still used traditional facilities at that time. In these kitchen drawings, he skillfully utilized the central perspective view of the kitchen interior to represent the whole and realistic view of the kitchen in order to highlight the efficiency of this kitchen. In these drawings, he indicated the name of each kitchen facility (for example, the sink, pantry, stove, etc.) to show how they were integrated in the kitchen space.

In terms of Gilryong Park’s residential improvement, tradition and modernity appeared around the kitchen and began to collide. In particular, given that the kitchen involves various chain of steps, it was a suitable space for experimenting with efficiency, a modern concept (Do Citation2020, 74). Christine Frederick’s initial diagram of the chain of steps involved in a kitchen, presented in New Housekeeping (Frederick Citation1913), and Gilryong Park’s “Theory of traditional house improvement” both focused on the flow of the movements in a kitchen (). Park’s intention to reform kitchens can be interpreted in the context of the introduction of the concept of “scientific management of domestic labor,” related with the theory of Taylorism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and the emergence of the “Frankfurt kitchen” resulting from the “practical domestic movement” in the early 1920s in Europe (Lee Citation2019, 93). Moreover, one can assume that the reforms of kitchens in Western countries provoked the aspirations toward and imitation of Western standing-style kitchens in Japan, which subsequently impacted Korea (Do Citation2018, Citation2020).

Figure 12. Christine Frederick’s initial diagram (Frederick Citation1913, 52) of the chain of steps involved in kitchen chores, presented in new housekeeping: efficiency studies in home management (Redrawing by author).

While working on housing improvement, Park attempted to integrate the elements of traditional Korean architecture to construct his architecture (Lim Citation2011, 237). Although his improvements for the new houses included elements of modern living, he insisted that Korean traditional architectural characteristics, such as the ondol system, should be included in the modern designs. To realize the ondol system in modern Korean housing, he made a thorough examination of the system. He subsequently introduced the ondol system in his sketches in the architectural magazine Joseon and Architecture () (G. Park Citation1940, 17).

5. Dongjin Park’s interpretation of tradition in building modernity

Like Gilryong Park, Dongjin Park also aimed to overcome the drawbacks of traditional Korean architecture to construct his architecture. However, Dongjin Park had a more aggressive approach in applying Western architectural modernity to the Korean context, and this is demonstrated his statement: “As an animal adjusts to its environment, we [Korea] should slowly adapt our lives to the modern international way of life to survive” (D. Park Citation1931b, 4). Although rudimentary and lacking in depth from the current perspective, Dongjin Park had made attempts to use the Western modern architectural style since the 1930s.

Park published 16 essays in The Donga Ilbo under the title “About Our Houses (우리 住宅에 對하야)” from 14 March 1931 to 5 April 1931. In these essays, he introduced the “trends of modern architecture (現代建築의 趨勢)” and emphasized the importance of studying other countries’ examples to determine the future of Korean houses (D. Park Citation1931c, 4). Through these articles, he introduced architectural movements of European countries such as the French Art Nouveau Movement, Austrian Secession Movement, Dutch Modernist Movement, and German modernist architectural movement. Furthermore, he introduced the works of individual architects like Le Corbusier of France, Berlage of the Netherlands, and Hans Scharoun of Germany to the public through his writings. He stated the following in one of his articles:

This writing is not intended to explore the technical details of a particular architecture. To determine the trend of our houses, we should know what other countries are doing and what these countries are arguing about architecture. Even if the content of this essay may be inconsistent, I aim to introduce the architectural trends in the modern world …

In modern society, architecture enjoys a significant position among various arts [in other words, the status of architecture is very high]. It is a great product to incorporate a new thinking of architecture in the late 19th century (D. Park Citation1931c, 4; emphasis added).Footnote25

Based on such writings, one can assume that Park was having the Western modernism in mind and considered the works of key leaders of Western modernism to construct Korean modern architecture in the beginning of the 1930s (Kim Citation2018, 216). Therefore, he was considerably favored toward the styles and philosophies of European architecture and volunteered to provide international perspectives to Korean architecture by sharing the architectural culture of the Western countries with Korean citizens. Additionally, through his writings, Korean citizens gained more understanding of the status of Korean architecture of that time.

Park outlined his philosophical understanding of traditional Korean houses in “About Our Houses.” In the first article, he claimed that “housing is a bowl that holds our lives,” that is, traditional Korean houses reflect the lives, customs, and culture of Korea (D. Park Citation1931a, 4). He said that “[in the] East and West [our] home is the best” in The Dong-A Ilbo on 15 March 1931 (D. Park Citation1931b, 4). In this article, “home” indicates traditional Korean houses. He argued that Korean housing should be suitable not only for Korean manners and customs, but also for the natural characteristics and environment of the country and the people. His recognition of tradition, natural characteristics, and environment can be clearly discerned in his following statement:

The climate and natural characteristics are our destiny, granted with respect to the region. We can’t control our climate and natural characteristics. We should accept this fate. Therefore, our housing should be developed and adjusted to this environment. For example, bungalow housing, one of the Indian housing types, has been developed in order to adjust to India’s climate and other natural characteristics. The reason why Japan has strength in wooden structure is that the wooden material is befitting the Japanese vernacular environment. The individuals who designed the Gothic style were sagacious because these were aware that this architectural style was suitable to their climate and natural characteristics (D. Park Citation1931c, 4; emphasis added).

Park believed that if Koreans ignored tradition and adopted Western culture without a deep understanding of that culture, the new culture would not last long. To explain his argument, Park gave an example of Dutch architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage, whom he greatly respected, and quoted his saying that “In order to construct a united composition, the national idea is significant” (D. Park Citation1931i, 4). He believed that Korean modern architecture should be implemented by considering “Korean manners and customs” and should match the “Korean climate” (D. Park Citation1931c, 4). According to him, the natural climate and characteristics of Korea were important not only because these were the foundation of Korean life, but that they were also the most important factors to be considered in forming a new style of architecture. Therefore, he believed that ignoring nature would not only mean ignoring the particulars of Korean life, it would also prevent Korea from developing as a nation because nature represented the culture of Korean life.

In the 1930s, Park realized some problems concerning traditional Korean architecture. Some of these problems were “dysfunctional nature,” “nondurable,” “lack of sanitation,” etc (D. Park Citation1931f, 4; D.Citation1931j, 4).Footnote26 He believed that the main problem concerning traditional Korean architecture was that it was primarily constructed using soil and wood. He encouraged engineers(or architects) to discover new construction materials and use materials suitable to the climate in Korea. He preferred granite as the exterior material, although granite at that time was considered as a premodern material and many modern architects avoided using granite in their structures (D. Park Citation1955).Footnote27 Since granite offered more durability than soil and wood, he chose an architect’s aesthetics over an engineering approach and made use of the advantages that granite offers. He stressed the use of reinforced concrete to supplement the structural weaknesses with traditional Korean architecture.

Similar to Gilryong Park, Dongjin Park also supported housing improvements in accordance with Western modern ideas of “rationality” and “functionality.” Dongjin Park took seriously that the traditional system of hanok was contradictory to modern life. In his opinion, it was impossible to adapt to modern times through the maintaining of our tradition, and he insisted on the reinterpretation of this tradition. His following statement expresses his thoughts regarding hanok:

[Hanok] has a poor appearance, lacking of the capacity to change [to modern life] … It used primeval materials … its design style originated from the feudal age … I cannot change my opinion regarding the inefficiency plan [of hanok] (D. Park Citation1941a, 94; emphasis added).Footnote28

Therefore, Park argued that the relationship between each room in the house needs to be managed in order to improve efficiency, which in turn would save people’s time. These efforts would help residents to avoid wasting time and energy and to focus on their own purposes. Additionally, he believed that the kitchen should be planned scientifically (D. Park Citation1931j, 4).

Park explored traditional Korean housing in detail. He published a series of articles about the living room, the floor, the second bedroom, the kitchen, and the bathroom in The Dong-A Ilbo from 20 March 1931 to 26 March 1931(D. Park Citation1931d, 4; D.Citation1931e, 4; D.Citation1931f, 4). He stressed on the importance of hygiene in each article, but was most forceful in his discussion of hygiene with respect to the bathroom and kitchen, pointing out the various problems and drawbacks of the traditional bathroom in terms of hygiene and sanitation (D. Park Citation1931f, 4). According to him, the spaces urgently in need of alteration were the kitchen and bathroom in traditional Korean houses. In the transitional period from the premodern to the modern period, hygiene became the most important topic, and kitchens and bathrooms were the most-discussed spaces in modern architecture. He, as an architect, wanted to solve the hygiene problems in the bathroom and kitchen in traditional Korean houses.

Until the 1930s, Park supported the use of the ondol system in traditional Korean housing. He strongly believed that the ondol was the heating system that best matched the traditional Korean architecture and life (D. Park Citation1931g, 4). He argued that the ondol is a very unique and innovative system whose variants are found all over the world. He compared the ondol with some similar heating systems in the West, such as the fireplace, radiator, ceiling heating, and stove, and strongly argued that these Western heating systems are not a good fit for the Korean environment.

However, Park’s attitude toward the usage of the ondol changed after the 1940s. At that time, some people criticized the “unhygienic” and “uneconomical” aspects of the ondol, calling for the “abolition of ondol.” He later insisted on reconsidering the use the ondol and urged people to instead adopt the pechka, a Russian brick stove, emphasizing its practical advantages (D. Park Citation1941a, 101). Park’s withdrawal of support to the ondol along with the change of opinion of many Korean people regarding the ondol may be attributed to the Japanese influence on Korea, leading to the suppression of Korean ideals.

The author [I, Dongjin Park] is a prohibitionist of ondol in our life. The use of the ondol not only leads enormous economic loss, but leads to the loss of the sprit and style. There is no end to discussing the harmful effects of ondol. The lethargy and inefficient life of Korean citizens are all related to the use of ondol. The use of ondol has also contributed make our mountains and fields desolate. Let’s put an end to use of the ondol life and make a meaningful new start for a glorious life (D. Park Citation1941a, 101; emphasis added).

Based on his interpretation of Korean tradition and his recognition of architecture’s role in supporting this tradition, Park proposed the concept of New Housing Type (新住家) in Korea. In particular, he focused on improving facilities such as the kitchen and bathroom because he believed that these facilities in traditional Korean housing were far behind those in Western housing. A kitchen is also strongly related to the residents’ hygiene and overall convenience. At that time, people who promoted a modern approach, including him, believed that one of the important differences between modern and traditional life was related to hygiene. Moreover, he commended the scientific management of Western kitchens because people in Western countries easily managed all of the kitchen facilities, such as electric appliances, kitchen stove, and furniture, by using only one switch (D. Park Citation1931j, 4). He believed that if we consider the relationships between each room (space), facilities, and furniture, these considerations will help residents increase their efficiency. He recommended the adoption of Western techniques and functions in the kitchen as a means of overcoming the problems of traditional kitchens.

Park encouraged people to renovate bathrooms in traditional houses because improving the bathroom played a significant role in improving not only their efficiency, but also the aspect of hygiene in traditional Korean architecture. Therefore, he argued that the bathrooms should be located near the main building. Moreover, he suggested that the residents of traditional Korean houses should install new bathrooms that included a tank, a toilet, aeration equipment for the treatment of sewage, etc. for improving the hygiene of Korean housing (D. Park Citation1931k, 4). In order to realize this, he argued that it was necessary for traditional Korean houses to incorporate Western style bathrooms.

6. Conclusion: hermeneutic interpretation of two architects

This research endeavors to reveal the origins of modernism in Korean architecture within the context of East Asian modernism and to explore the cultural encounters between the East and the West in terms of modernity. As philosopher Paul Ricœur emphasized, the significance of “the encounter of other cultures” (Ricoeur Citation1965, 283) for identifying cultural identities and exploring cross-cultural exchanges will not only enable the original cultures to sustain their originality but will also help to redefine the original cultures (Zou Citation2012, 276).

In terms of the influence of the West on the progression of the East Asian towards modernity, Gilryong Park and Dongjin Park were the first generation of Korean modern architects who tried to integrate tradition and modernity. These two architects were aware of the problems associated with traditional Korean housing and expressed their opinions on the need to improve traditional Korean housing. For them, adapting tradition was a significant matter to construct modernity. However, when these two representative modern Korean architects led the movements toward modernity, they had different understandings of tradition and their approaches to inheriting tradition and interpreting modernity were different.

To begin with, Gilryong Park had a positive and active attitude toward integrating tradition into Korean modern architecture. He attempted to explore the orientation of modern architecture that was rooted in the origins and traditions of Korea. For instance, he was persistent in considering the ondol, a heating system used in traditional Korean houses, as one of the key factors of Korean design and sensibility, and insisted that the ondol be included in the design of modern houses (G. Park Citation1939, 9). In 1940, when he wrote a special article on ondol in Joseon and Architect, he introduced the ondol that he himself studied and reformed (G. Park Citation1940, 17). He also tried aggressively to embody the modern elements. For instance, he suggested the specific idea to spatialize the modern effective space, which is accepted under the name of efficiency. In particular, by analyzing the pros and cons of the traditional courtyard housing plan and the centralized housing plan, he recommended the adoption of the centralized housing plan for constructing Korean modern houses.

Gilryong Park’s determination to improve traditional house was also seen concretely around the kitchen. He focused on the shortcomings of the kitchen in Korean houses and tried to improve it by analyzing by each element. For example, he argued that the kitchen, unlike that in traditional houses, should be located in the back of the house or that the kitchen should follow the style of the Western walk-in kitchen, which separates the heating from the kitchen and eliminates the height between living room and kitchen’s floor. In addition, he advocated for the introduction of modern elements in the traditional kitchen in order to reform the traditional kitchen. While more in-depth research is necessary, his efforts to improve kitchens can be attributed to the kitchen improvement movement in the West and the respect, as well as the emulation, of Japan’s Western walk-in kitchen, the influence of which reached the Joseon architect. If Park’s kitchen improvement plan was spurred by the global trend at that time, the improvement plan for ondol was simply a result of his serious distress regarding the heating system of houses in Korea as well as his enthusiasm to improve it. Moreover, he went beyond architecture and worked in various fields. In particular, it was he who publicized the phrase “Scientification of Life” in Korea (G. Park Citation1935, 4).

Dongjin Park had more radical approaches and tried to overcome the tradition of Korean architecture to construct modernity. His view on traditional architecture was negative and even self-deprecating. He described Korean traditional architecture negatively by using expressions including “defective,” “spiritless,” “unrealistic,” “primitive,” and “inefficient” (D. Park Citation1941a, 94). He pointed out several deficiencies of traditional Korean houses. In particular, he proposed to abolish the ondol, which was regarded as the most crucial component of traditional Korean houses since the 1940s, and recommended the adoption of Western heating methods. He used the words “impaired” and “life-threatening” and argued with aggressive and radical content that Korea Joseon needs to overcome their traditional kitchen (D. Park Citation1931f, 4; D. Park Citation1931h, 4). Based on hygiene, Korean kitchen for him was only a disadvantage rather than an advantage; it was the space where should be overcome.

Dongjin Park showed relatively more proactive attitudes in accepting Western modern philosophies. The ideal architecture in his mind was the modern architecture that “rebelled against the architecture bounded by tradition and convention” (D. Park Citation1931c, 4). Of course, the degree of understanding was not in depth by the current standards, but he introduced Western movements such as Art Nouveau or the Secession Movement, he continuously introduced the modern architectural styles of Western countries like the Netherlands, Germany, England, France, and Russia, and their architectural examples to the public through his writings. His various writings included Le Corbusier from France, Otto Wagner from Austria, Hendrick Petrus Berlage from the Netherlands, and Russian constructivist architects. All of them were the architects who advocated for the new architecture that deviates from the classical styles of the old era in the West. They denied decorative elements and pursued geometric forms and materials that reflected the era of industrialization, mechanization, and internationalization.

As such, while Gilryong Park was eclectic and compromising towards inheriting tradition and accepting Western modernity, Dongjin Park was radical and uncompromising on them. Before Korea’s liberation from Japan, Korean modern architecture was motivated by nationalism and reformism. Korean modern architecture embodied selective modern Western materials and styles conceptually rather than in any physical aspect. In this sense, these two architects’ endeavors enabled Korean society to move forward from tradition to modern times, that is, they assisted early Korean modern architecture to find its historical sustainability between two periods.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Zou for his discussion of this topic in the early stage. I am also grateful for the invaluable feedback on this manuscript from anonymous peer reviews of JAABE.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Myengsoo Seo

Myengsoo Seo is currently an Assistant Professor at Hankyong National University (HKNU), South Korea. Before he joined this institute, he was a Post-doc research fellow of Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies at Seoul National University and was a visiting researcher at McGill University in Canada. His research interests include the comparative cultural study of architectural history, Korean modern architecture, historic preservation of the memorable built environment, and urban revitalization.

Notes

1 As stated by the hermeneutical architectural historian Dalibor Vesely, architecture cannot “be confined” to its value “entirely” through its natural character, rather, it can find its value also through outside influences (Vesely Citation2004, 356). His idea has a different perspective from that of “Objective-Oriented ontology” by philosopher Graham Harman, who asserted that the contexts don’t explain what the work is ontologically (Harman Citation2018). However, I agree with Vesely’s viewpoint which emphasizes the context of building. Furthermore, I explain his aspect on context by not only including the physical context in which the building is placed but also including the social and cultural context that helped him expand his thought.

2 Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School (京城工業專門學校) was established in 1916. It was renamed as Gyeongseong High Industrial School (京城高等工業學校) in 1922 and remained in operation until 1946.

3 Originally quoted in the Record of Gyeongseong High Industrial School (1939).

4 Gilryong Park has been introduced to the public as the first Joseon architect to open an architectural office during the Japanese colonial era. However, a recent study shows that the architect Hunwoo Yi served as a public worker before Gilryong Park for the Government General of Joseon and opened an architectural office 11 years before Gilryong Park (Kim, Dylan, and Hwang Citation2020, 37–50). This research will be able to give new interpretation in Korean modern architectural history.

5 The Joseon and Architecture (朝鮮と建築) was a Japanese architectural magazine published by Association of Joseon Architecture in Korea.

6 In the special issue of Joseon and Architecture, Sasa Keiichi wrote an article “Respectable Park’s Memorable Figures”.

7 In the special issue of Joseon and Architecture, Jukura Imazu wrote an article “Park Gilryong’s Activities”.

8 Starting from red-brick “Western-style” buildings in Seongbuk-dong in 1929, he mainly designed public buildings, bank offices, and commercial buildings consisting of four or five floors in the 1930s. His representative buildings include Joseon Life Insurance Headquarters Building (1930), Gyeongseong Imperial College Administrative Building (1930), Jongro Department Store (1931), Nam daemun Branch Office for Jeil Bank (1931), Kim’s Gahoe-dong Residence (1931), Hancheong Building (1934), Hwashin Department Store (1935), Gyeongseong Women’s Business School (1937), Hyehwa Professional School (1934), etc (Kim Citation2013, 367).

9 Information regarding “The Research Association for Traditional Houses of Joseon” can be found in The Dong-A Ilbo published on 2 June 1932.

10 The table of contents consists of: 1. The land area and building area, 2. Room assignment, 3. Room orientation, 4. Unification of “Kan” units, 5. The main gate and the entrance, 6. The main gate and servants’ quarters, 7. The ban-chim (small storage/bedrooms) and attics, 8. Jang-dok-dae (a platform for crocks of sauces and condiments), 9. Toilet, 10. The kitchen, 11. Foundation and poles, and 12. Threshold.

11 The table of contents of this volume consists of 1. Preface [Introduction] 2. Alignment, 3. Furnace [fireplace] and stack [chimney], 4. Drift passages [passage for the drift under the floor for the ondol system] and flagstones [flat stones used for Korean heating system], and 5. Types of modern inner ondol systems.

12 Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School (1916–1922) and Gyeongseong High Industrial School (1922–1945).

13 At that time, working for the Japanese Government-General of Korea after graduating from Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School or Gyeongseong High Industrial School was a preferred career path for Korean architects as well as Japanese architects.

14 According to the conditions that were suggested as the criteria for “the first generation of Korean (modern) architects” in prior studies, they include 1) a person who received modern architecture education at the secondary education level, and 2) a person who autonomously designed his/her work through design and construction practices. The first generation of Korean (modern) architects could experience the “modern architectural ideas,” although it wasn’t enough from the current perspective, through the architecture education provided at the secondary education level.

15 The Japanese course titles in Ahn’s dissertation are translated by the author into Korean and English.

16 For the educational curriculum of the Department of Architecture in Gyeongseong High Industrial School during 1917–18 and 1924–25, please refer to the study by Chang-mo Ahn, “A Study on the Architect Park Dongjin” (Ahn Citation1997, 11–37).

17 Although rudimentary and lacking in depth, Dongjin Park had made attempts to use the Western modern architectural style since the 1930s. For instance, he designed the Office Building of the Chosun Ilbo in 1935, which featured simple facades and asymmetrical surfaces in the repeatedly used window pattern.

18 For buildings designed by Dongjin Park, please refer to the study by Myengsoo Seo “Accommodation of Western Modernism in Korean Architecture – A Case Study of Dong-jin Park (1899–1981)” (Seo Citation2017, 264).

19 The book series Advanced Study of Architecture (高等建築學) were used as references at Gyeongseong High Industrial School. The “Stereotomy” course at this school included the instruction of carpentry skills since Japanese architecture was more focused on using wooden materials at that time. Thus, Japanese faculty members taught Japanese style architecture through courses such as “History of Architecture” and “Stereotomy.” Students developed their design skills through architectural engineering courses focused on Japan’s needs, such as “Applied Mechanics,” “Construction of Houses,” and “Construction Design.” Japan has traditionally possessed knowledge regarding architectural structure design because it frequently experiences earthquakes. Such an external context was reflected in the educational system of Gyeongseong Industrial Professional School. One of the students at the school, Jang Kiin, said that their education was also influenced by Japanized English education because some of the Japanese professors were educated in England (Ahn Citation1997, 29).

20 Bosung College was later renamed as Korea University in 1946. The two buildings were designated as historical landmarks no. 285 and no. 286, respectively, in 1981.

21 For a comparison between the Bosung College Library and the buildings of Duke University, Hyon-Sob Kim criticizes the existing conventional beliefs that both the main building and library building of Bosung College were modeled after the buildings in Duke University. He addressed the significance of differentiating the architectural origins of the main building and library. He highlighted that only the Bosung College Library was influenced by the buildings around the library building of Duke University (i.e., the medical school building and student union building) (Kim Citation2012, 57).

22 Dongjin Park published 16 different essays in The Dong-A Ilbo with the series name “About Our Houses,” on the following dates in 1931: (1) March 14; (2) March 15; (3) March 17; (4) March 18; (5) March 19; (6) March 20; (7) March 25; (8) March 26; (9) March 27; (10) March 28; (11) March 29; (12) March 31; (13) April 2; (14) April 3; (15) April 4; (16) April 5.

23 The author introduced and presented Gilryong Park’s ideas and works at the 13th Docomomo International Conference Seoul, 2014. Also, a part of this section was adopted and modified from the conference presentation proceedings: Myengsoo Seo. “The Recognition of Tradition in Early Modernity: A Cross-Cultural Approach to Korean Modern Architecture,” Proceedings of the 13th Docomomo International Conference Seoul (Seo Citation2014, 402–405).

24 In his housing improvement proposal, “fire” played a crucial role in understanding the meaning of life. In Western tradition, as implied by Plato’s concept of chōra, architectural space is a receptacle to contain our life and is related to the cosmos that constitutes the cosmic elements of fire, air, water, and earth (Plato Citation2000, 67). Vitruvius also emphasized fire in the section of “The Origin of the Dwelling House” in his Ten Books on Architecture. The discovery of fire enabled people to come together, and subsequently led to their assembly, communication, and the construction of architecture (Pollio Citation1960, 38). In Korean culture, fire symbolizes active and energetic new challenges. In Korean traditional architecture, a fire was preserved in a brazier, and it was an important duty of housewives to keep the fire alive in the house. Thus, whenever Koreans moved to a new house, they considered the location of fire in their new house. In this sense, locating fire is not only employing its utility, but it also has significant symbolic meaning in architecture.

25 The quote was adopted from the author’s previous research paper, and the author modified the translation based on the original text: Myengsoo Seo, “Accommodation of Western Modernism in Korean Architecture – A Case Study of Dong-jin Park (1899–1981)” (Seo Citation2017, 265).

26 Park mentioned some problems regarding traditional Korean architecture in his articles.

27 For Dongjin Park, “granite” was very a significant material in the context of Bosung College buildings.

28 The quote was adopted from the author’s previous research paper, and the author modified the translation based on the original text: Myengsoo Seo, “Accommodation of Western Modernism in Korean Architecture – A Case Study of Dong-jin Park (1899–1981)” (Seo Citation2017, 265).

References

- Ahn, C. 1997. “A Study on the Architect Park Dongjin.” PhD diss., Seoul National University.

- Association of Joseon Architecture. 1943. “Park Gilryong Memorial (故朴吉龍君追悼記).” Joseon and Architecture (朝鮮と建築) 22 (5): 13–22.

- Berman, M. 1988. All that Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. New York: Viking Penguin.

- Călinescu, M. 1987. Five Faces of Modernity: Modernism, Avant-garde, Decadence, Kitsch, Postmodernism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Collins, P. 1965. Changing Ideals in Modern Architecture, 1750-1950. London: Faber & Faber.

- Colquhoun, A. 2002. Modern Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Do, Y. 2018. “Adoption and Development of the Modern Kitchen in Korea: Focused on the Rationalization of Housework.” PhD diss., Seoul National University.

- Do, Y. 2020. The Birth of Modern Kitchen and the Other Side. Seoul: Spacetime.

- Frampton, K. 1992. Modern Architecture: A Critical History. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Frederick, C. 1913. New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Frederick, C. 1920. Household Engineering; Scientific Management in the Home. Chicago: American School of Home Economics.

- Green Flag Federation. 1940. “The Number One Architect in Joseon, Park Gilryong (조선건축계의 제1인자 박길룡씨).” Green Flag (綠旗) 5 (5): 87.

- Harman, G. 2018. Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything. London: Pelican Book.

- Heidegger, M. 1977. “On the Essence of Truth.” In Basic Writings from Being and Time (1927), to the Task of Thinking (1964), edited by D. F. Krell, 111–138. New York: Harper & Row.

- Heynen, H. 1999. Architecture and Modernity: A Critique. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Hyeon, W. 1977. “The Promotion Movement of Science and Technology Studies.” Study of Ethical Culture 12: 239–286.

- Kim, D. 2013. History of Korean Architecture. Edited by Gregory A. Tisher and translated by Jong-hyun Lim. Suwon: University of Kyonggi Press

- Kim, H. 2012. “Tracing the Architectural Origin of the Bosung College Library 1935-37.” Journal of Architectural History 21 (3): 47–58.

- Kim, H. 2016. Architecture of Korea University. Seoul: Korea University Press.

- Kim, H. 2018. “Le Corbusier and Modern Architecture in Korea.” In Kim Chung-up Meets Le Corbusier, edited by K. Eunmi and H. J. Kim, 214–233. Anyang: Anyang Foundation for Culture & Arts.

- Kim, H., Y. Dylan, and D. Hwang. 2020. “A Research On Architect Yi Hunwoo.” Journal of Architectural History 29 (3): 37–50.

- Kim, J. 1982. “A Study on the Formation of Korean Modern Architecture.” Master’s thesis, Hongik University.

- Kim, M. 2011. “The Improved Plans of Korean Traditional Folk Houses by Park Gilryong from the Late 1920s to Early 1930s.” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea 27 (4): 61–70.

- Lee, K. 2019. Houses of Gyeongseong. House: Seoul.

- Lee, Y. 1990. “Architectural Representation of National Spirits: The Architect Park Dongjin’s Ideas and Works.” Architecture and Environments 1: 149–157.

- Lim, C. 2011. The Korean Housing, Typology and Changing History. Seoul: Dolbegae.

- Oka, M. 1935. Advanced Study of Architecture 2: Western and Eastern Architectural Style (高等建築學 二編: 西洋東洋建築樣式). Tokyo: Tokiwa Shobo.

- Park, D. 1931a. “About Our Houses 1 (우리 住宅에 對하야 一).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 14, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931b. “About Our Houses 2 (우리 住宅에 對하야 二).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 15, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931c. “About Our Houses 3 (우리 住宅에 對하야 三).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 17, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931d. “About Our Houses 6 (우리 住宅에 對하야 六).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 20, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931e. “About Our Houses 7 (우리 住宅에 對하야 七).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 25, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931f. “About Our Houses 8 (우리 住宅에 對하야 八).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 26, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931g. “About Our Houses 9 (우리 住宅에 對하야 九).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 27, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931h. “About Our Houses 10 (우리 住宅에 對하야 十).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 28, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931i. “About Our Houses 11 (우리 住宅에 對하야 十一).” The Dong-A Ilbo, March 29, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931j. “About Our Houses 14 (우리 住宅에 對하야 十四).” The Dong-A Ilbo, April 3, 1931.

- Park, D. 1931k. “About Our Houses 15 (우리 住宅에 對하야 十五).” The Dong-A Ilbo, April 4, 1931.

- Park, D. 1941a. “On Reforming Korean Housing (朝鮮住宅改革論).” Spring and Autumn (春秋) 2 (7): 92–101.

- Park, D. 1955. “About Granite: Inchon Sung-soo Kim and I.” Korea University Newspaper, May 16, 1955.

- Park, G. 1931. “Housing-Reform the Kitchen and Bathroom (벅과 뒷간을 改良하라).” The Dong-A Ilbo, January 1, 1931.

- Park, G. 1932a. “About the Kitchen 1 (廚에 대하야 一).” The Dong-A Ilbo, August 8, 1932.

- Park, G. 1932b. “About the Kitchen 2 (廚에 대하야 二).” The Dong-A Ilbo, August 10, 1932.

- Park, G. 1932c. “About the Kitchen 3 (廚에 대하야 三).” The Dong-A Ilbo, August 11, 1932.

- Park, G. 1932d. “About the Kitchen 4 (廚에 대하야 四).” The Dong-A Ilbo, August 12, 1932.

- Park, G. 1932e. “About the Kitchen 5 (廚에 대하야 五).” The Dong-A Ilbo, August 13, 1932.

- Park, G. 1932f. “About the Kitchen 6 (廚에 대하야 六).” The Dong-A Ilbo, August 14, 1932.

- Park, G. 1933. On Dwelling Reform of Traditional Housing, No.1. Seoul: Self-published.

- Park, G. 1935. “About Scientification of Life (생활의 과학화에 대하야).” The Dong-A Ilbo, April 19, 1935.

- Park, G. 1937. On Dwelling Reform of Traditional Housing, No.2. Seoul: Yimundang.