ABSTRACT

The birthrate in Japan is declining rapidly, which is attributed to the lack of perspective and consideration for “child-rearing” in the architecture of cities. Therefore, to gain knowledge of the measures to support child-rearing, determining factors such as how urban space is used is essential. In this study, Japanese parents were requested to send pictures of their surrounding environment. The survey used the caption evaluation method to target naturally low-rise residential, planned residential, and mixed areas. On evaluation of the photographs, we found no regional differences in terms of safety and convenience. Despite the space created for walking, the parents actively enjoyed playing with the children. In the naturally low-rise residential areas, parents could select various routes. Conversely, the planned housing complexes did not have a wide choice of routes, limiting the play area. Therefore, a policy that incorporates this perspective is also necessary to improve the urban environment and consider the differences in each region to create an environment conducive to child-rearing.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

In recent years, rapidly declining birthrate has become a serious issue in Japan. This decline has been attributed to the difficulty of child-rearing due to a lack of consideration for it in society, such as diversification of the working conditions of parents and lack of support for child-rearing services. To improve the birthrate, the Japanese government has implemented child-rearing support measures such as building nursery schools, providing financial support for child-rearing households, and promoting suitable work styles with, for example, shortened working hours and flextime. Currently, there is no environmental consideration for children and parents who are raising them.

When interviewed about “going out,” approximately 27% said they would like to go out actively to various places, whereas about 70% would like to go out without any kind of anxiety. Overall, 96% of the parents like to go out with their children (Child Future Foundation, 2011), but 34.9% of the parents of preschoolers said they did not think it was easy to go out (The Dai-ichi Life Research Institute 2007). Similarly, a report by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, General Policy Bureau, indicated that parents have negative opinions and often hesitate to go out (the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, General Policy Bureau 2010). Such parents face anxiety and dissatisfaction outdoors. Therefore, it is necessary to address their difficulties and dissatisfactions.

1.2. Previous studies

Existing research worldwide has emphasized the need for children’s outdoor activities and the need to improve the urban environment. Yun et al. (Citation2005) observed children playing in six cities in Vietnam and showed that children’s play is highly dependent on the environment due to their interaction with the environmental resources. Tappe et al. (Citation2013) conducted a study in Seattle and San Diego where they made children wear accelerometers and analyzed their activities by location. Studies conclude that a safe playground is indispensable for parents to support the activities of their children. A study conducted at an orphanage for 6- to 11-year-old kids suggests that parents’ awareness of crime prevention influences their children’s activities. Further, Bringolf-Isler et al. (Citation2010) also reported that parents’ concerns about traffic and safety affected their children’s outdoor playtime at elementary schools.

In the city of Eindhoven in the Netherlands, a relatively child-friendly place, observations, workshops, and interviews have revealed great concerns about outdoor play and safety. There is also a need for a wide range of research to meet various demographic requirements in the future (Krishnamurthy Citation2019). Further, the research concludes that for an improved built environment, a separate place that is child-friendly should be created as a safe place (Elshater Citation2018). In addition, there are case studies that introduce actions and projects for child-friendly community development that incorporate children’s perspectives, such as those conducted by Derr and Tarantini (Citation2016) and Malone (Citation2013).

As mentioned above, children’s outdoor play is greatly affected by urban environmental requirements. From this point of view, research that considers regional characteristics is necessary. Contrary to other studies that focus on school children, our study focuses on preschool children, who generally do not make decisions about “going out” with their parents.

In Japan, since the 1950s and 60s, many classical studies on facility planning have been conducted, such as on the standards for setting up nursery schools and plans that reflect childcare content. In recent years, some studies have focused on the behavioral characteristics of children in daycare centers (Sato, Nishide, and Takahashi Citation2004). Furthermore, against the background of diversifying needs for childcare, education, and the declining birthrate, the direction of operation of facilities where kindergarten and nursery schools are unified, the lives of children, the management mode, mixed childcare, and the transition of activity places are discussed (Yamada et al. Citation2008). This research aims to improve the quality of life of children in childcare facilities against the backdrop of the declining birthrate.

In recent years, research has been conducted with parents and children as the survey subjects and also considering the government’s child-rearing support measures. Matsuhashi et al. (Citation2006) studied the preferred place of parents and children and the ideal child-rearing support facilities. They clarified the actual situation of child-rearing facilities in the area for parents and children. In addition, there is a discussion about the accessibility of transportation regarding outings for children, focusing on a barrier-free environment for preschoolers’ outings (Ohmori Citation2015). Based on the research by Matsuhashi et al. (Citation2006), the status of childcare support facilities which correspond to the social background have been examined in our study.

Further, in contrast to these studies, our study aims to clarify, from a micro perspective, how a parent or a caregiver with children uses the urban environment.

1.3. Purpose

Prior research has focused on the actual play conditions of facilities, school children, and preschool children. In this study, the urban environment, including indoor and outdoor facilities, from the viewpoint of parents, was evaluated. The role of “urban space” as an extension of the living environment where children are raised, and the recognition and evaluation of urban space in the daily life of parents and children, is discussed. The goal is to identify behavioral characteristics of parents and children on outings, and discover how to reorganize the current environment by reflecting on the characteristics. The entire study deals with both existing and planned urban areas. It plans to make inferences based on the differences in the environment and discuss urban environment evaluation. In particular, we focus on the “walking space,” where much time is spent, and discuss the behavioral characteristics of each region.

2. Survey outline

This section reveals how parents and children perceive and give meaning to urban spaces in their daily lives, depending on the area in which they reside. We provide a summary of the selection of the survey area, and the analysis of photographs and descriptions taken by the caption evaluation method.

2.1. Survey area

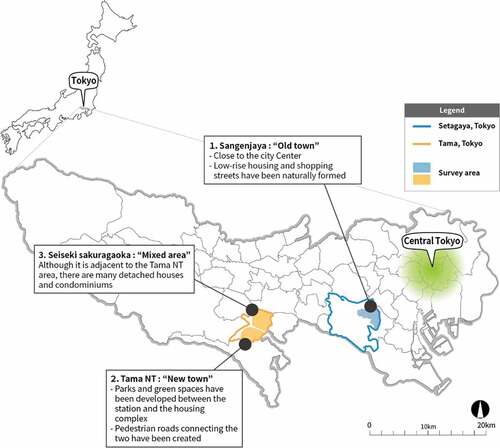

The target areas were Setagaya Ward and Tama City in Tokyo (). Setagaya Ward is approximately 15 km away from the city center and is a typical commuter town where existing urban areas and low-rise housing have naturally formed. In contrast, Tama City is a planned urban area in the suburbs, approximately 30 km from the city center. Despite the distance, it is convenient to access the city center without changing trains.

However, there are differences in the cityscape and road formation in terms of the naturally occurring area and the planned urban area, necessitating an analysis of the differences due to the living environment. As shown in , Tama City and Setagaya Ward differ in terms of area and total population, but the composition ratio of the surveyed preschoolers is similar, and there is no difference in population composition. The lower part of summarizes the public spaces that can be used by parents and children in each area.

Table 1. Overview of the survey area (created based on the information closest to the survey conducted in October 2009).

The park’s total area, which is the main outdoor playground, is larger in Setagaya Ward. However, its per capita park area is about three times that of Tama City due to the large population. The number of nursery schools, kindergartens, children’s centers, etc., is overwhelmingly high in Setagaya Ward. Considering that the population is about six times larger, there is no added advantage of having a large area in this ward.

In Setagaya Ward, the Sangenjaya district is the most prosperous area. Tama City has a new town area (hereinafter referred to as the Tama NT area) and an existing urban area (hereinafter referred to as Seiseki-Sakuragaoka area). Therefore, the analysis was divided into two areas and considered three regional characteristics.

2.2. Survey method

2.2.1. Caption evaluation method

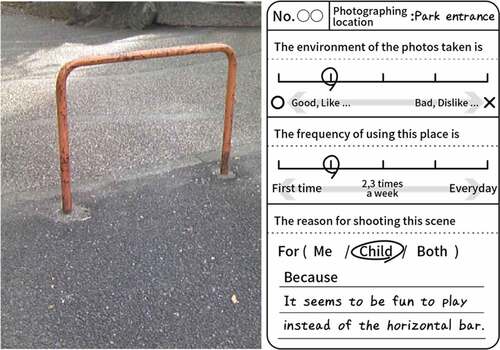

This study used the caption evaluation and photographic projection methods for investigation. The caption evaluation method was developed by Koga et al. (Citation1999), who conducted a landscape survey in Minato-ku, Tokyo, hoping for a more active survey method that would motivate the survey subjects.

To create an urban environment that satisfies users, it is necessary to first grasp users’ needs and incorporate them into the problem to be solved. Conventionally, methods such as questionnaires and interviews were used to determine users’ needs. In questionnaires, the investigator decides the needs items. Conversely, interviews largely depend on the individual qualities and abilities of the investigators to determine people’s needs; their subjectivity may be mixed.

To address the shortcomings of the interviews and survey, we used the caption evaluation method and photographic projection method to discover the needs of users.

2.2.2. Reasons for using the caption evaluation method

The purpose of this survey was to understand how parents who are raising children evaluate urban spaces. The caption evaluation method does not limit the target when evaluating the urban environment. Even if the definition of the evaluation target is not clear, such as “environment” and “space,” the survey subject can freely evaluate it. Thus, it is possible to select a target scene. In addition, this method can be reflected in the evaluation of not only recording photos but also experiencing the act of photography. This allows survey subjects to express their needs more easily than when they are asked, “Please tell us your needs.” In addition, this survey was conducted using a GPS receiver and a digital camera to precisely determine the shooting position.

2.2.3. Specific procedure in this survey

The investigation was carried out for a week during which the following instructions were given to the parents ().

Activate your GPS tracker when going out with the child.

Use the rented digital camera to take pictures of what you feel is “good” or “bad” from the perspective of raising children.

Next, write an evaluation (good/bad) of the scene, frequency of visits to the place, and reason for shooting, on the attached card.

At the end of one week of shooting pictures and evaluating the scenes, collate all the information.

The number of photographs (evaluation cases) indicates the number of photographs taken during the rental period of the device without specifying the subject of investigation, duration, etc. In addition, basic information on the subjects of the survey (age, gender, child-rearing support services used, camera usage time per week, etc.) was collected at the start of the survey.

2.2.4. Survey period and type of survey targets

From October 2009 to March 2010, questionnaires were distributed to parents and children who used nursery schools, kindergartens, and child-rearing support centers located in Setagaya Ward and Tama City. In addition, the outline of the photography survey was included in the questionnaire. The survey was finally conducted among parents and children who cooperated.

The questionnaire survey was distributed to five facilities in Sangenjaya, six facilities in Tama NT, and four facilities in the Seiseki-Sakuragaoka district, where 225 (recovery rate approximately 38%), 454 (recovery rate about 69%), and 314 (recovery rate about 63%) participants, respectively, were observed. Overall, 16 parents in Sangenjaya, 14 in Tama NT, and 15 in the Seiseki-Sakuragaoka district participated in this survey.

shows the child-rearing status of the parents who participated in this district-wise survey. The number and age of children (excluding siblings more than six years old) raised were plotted in the figure. An approximately equal proportion of 55.6% of the surveyed people reported the use of strollers, which can have a significant impact on the behavior of parents and children when moving around.

3. Analysis overview

In total, 630 photographs and 613 descriptions were obtained from the survey. Of these, photos that were not described were considered invalid, as one photo and one description card made a set (613 sets). Regarding the aggregation of the results, the evaluation structure was visualized by classification based on location.

3.1. Where the photo was taken

The places where the photographs were taken were divided into indoor (inside the building) and outdoor spaces (e.g., walking space, park) (). Generally, walking spaces are regarded as places to walk in and parks are regarded as a playground for children. At the time of classification, the location was determined by the photograph and the description content, but if it was unknown, the location was specified by GPS data.

Table 2. Classification of the location taken.

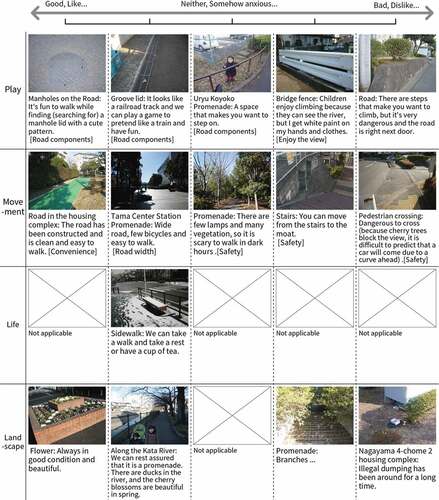

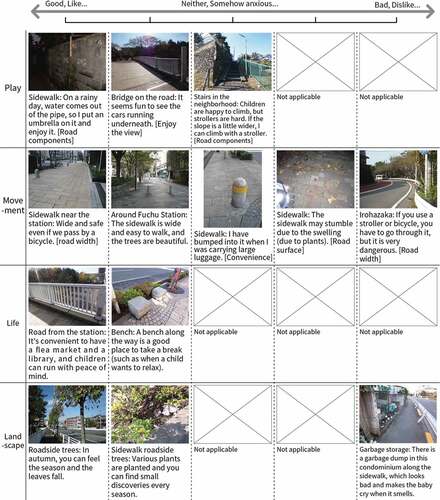

3.2. Scene of photos

Comments on the photographs taken by the survey subjects were written in one sentence. The content was often composed of “what [object]” and “how it feels [reason]” and [evaluates] as “satisfied/dissatisfied/neither can be said.” The content was analyzed using the following procedure.

The description content related to the evaluated environment was categorized into [target] of the evaluation (the title may be judged as the [target]) and [reason] for the evaluation.

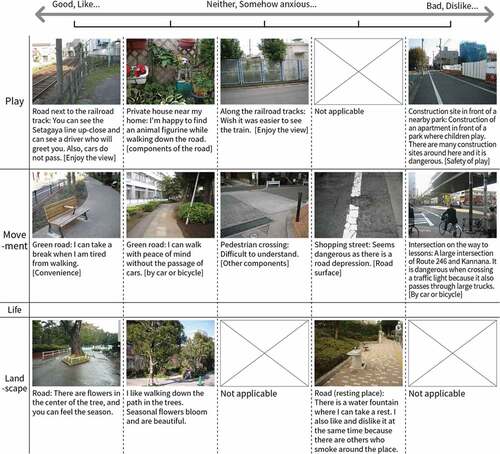

These categories [object] and [reason] were further classified and organized according to several types of items, and those with similar objects were grouped and named [scene]. lists the definitions of the scenes grouped in Step 2. To organize the several factors related to children’s play and movement, they were divided into [play] and [movement], and other photographs were classified into [life] and [landscape].

Each item organized was compared and analyzed [evaluation].

Photos and descriptions for each region were analyzed.

Table 3. Classification of scenes.

3.3. Outline of survey results

shows the percentage of places where the images were taken and the evaluation of those places. The evaluation is divided into five stages. In , the two frames on the left side are regarded as positive evaluations and the two frames on the right side are regarded as negative evaluations. About 64% of all the photographs were evaluated positively and about 28% were evaluated negatively. The photographs evaluated for each location (, the number on the right) were most often taken in the walking space, followed by the park.

Photographs taken in other outdoor spaces and the inside of a building include nursery schools, kindergarten gardens, department store rooftops, child support centers, and other places that are assumed to be used by children. About 80% of the outdoor spaces, including parks, were positively evaluated, implying that parents and children were highly satisfied with the place designed for use by children.

Thus, the purpose of use differs depending on the location, and it is expected that the evaluation criteria and their categorization will change. The pedestrian space is a highly public place, and it is not a place that was originally designed to be used only by “children.” Since nursery schools, kindergartens, and child support centers are facilities that are considered for use by children, many parents and children are positive in their evaluations of them, and it can be seen that there are relatively few problems. In this paper, we analyze the “walking space,” where most photographs were taken.

4. Diversity of meaning of walking space from the viewpoint of child-rearing

4.1. Overview of walking space

shows the breakdown of the photographs taken in the walking space. Since it is a “walking” space, the percentage of descriptions related to [movement] is the highest (approximately 51.6%), followed by that of [play] (approximately 34.6%). Contrary to parents’ and children’s views, a walking space is a place to walk. Not only is the content of [play] described as high, but the evaluation is also very high (a little less than 90%), implying that it serves as a playground rather than a place to [move] in. Further, the number of landscape photos taken was not high, but the rate of their positive evaluation was very high. There are two types of walking spaces: a sidewalk provided along with the roadway, and a promenade used only by pedestrians. The latter is often viewed positively because there is less danger from cars and bicycles.

The status of development of sidewalks and promenades varies depending on the target area. Sangenjaya and Tama NT have promenades and have been photographed by many survey subjects. In contrast, there is no promenade in Seiseki-Sakuragaoka. In addition, because the target area of Tama NT is an apartment complex, a pedestrian deck is provided separately from the promenade. Therefore, considering that the maintenance status of the walking space differs depending on the area, the details are analyzed for each area.

In the next section, we analyze the breakdown of the evaluation for each target area and clarify the relationship between the outing behavior and the evaluation from the representative outing routes of the survey participants. We mainly selected cases where the route connecting the destination and waypoints from home are clearly visible. This is because the survey subjects were instructed to switch on their GPS devices when going out, but the devices were not always carried around every day, and the number of cases recorded by the survey subjects varies. In addition, in the case of each district, distant areas were omitted, and only the area around the house was photographed.

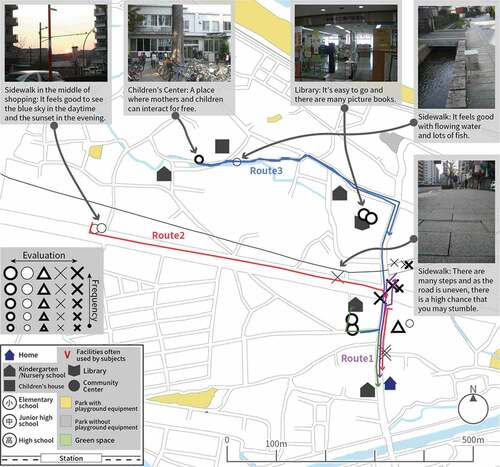

4.2. Recognition and evaluation of walking space by residential area

4.2.1. Sangenjaya district

4.2.1.1. Walking space as seen from photos and description

and show the evaluations of the photographs taken in the walking space of the Sangenjaya area. Compared to other areas (), the percentage of positive evaluations of walking space was the highest (66.29%) in Sangenjaya. The degree of satisfaction was particularly high on the promenade. Many of the scenes shot in the walking space were taken off the “movement” scene, which is the original function. On the other hand, the percentage of “play” scenes was also high, with 94.74% shooting “play” scenes as positive scenes, while 54.17% rated “movement” negatively. The walking space was more satisfying because of the occurrence of play rather than movement. The pedestrian space was more satisfying for the same reason. The contents of the play in the walking space were about the play itself and its safety.

The contents of play can be broadly divided into those that “enjoy the view” and those that use “road components.” As seen in , those in the former group could see the train and they enjoyed seeing a car from the top of the pedestrian bridge. After the survey, interviewed participants confirmed that the route was chosen to see the train. In many photographs of play using “road components,” children’s play was induced by familiar objects (e.g., “I’m happy to find an animal figurine while walking on the road,” “[It] is safe to climb the guardrail and play on the proper sidewalk,” etc.) The positive evaluation about children’s play and visual appeal of what was placed in the garden and entrance of the neighboring residential area are due to the characteristics of the Sangenjaya district, which has many detached residential areas.

In the “walking space,” the photos taken for the original purpose were the most frequently commented on, regarding the safety of children, and the contents related to safety led to a positive evaluation. The descriptions show positive evaluation by comments such as “there are no cars, and you can walk with peace of mind.” There are many cases where evaluations were divided according to the presence or absence of cars and bicycles, such as “the number of people, bicycles, and cars is very large, it is difficult to pass, and it is dangerous.” In addition, regarding ease of movement, most of the opinions were that it was dangerous and inconvenient to push strollers when the road surface was not smooth and even, while the satisfaction level increased when the road was maintained.

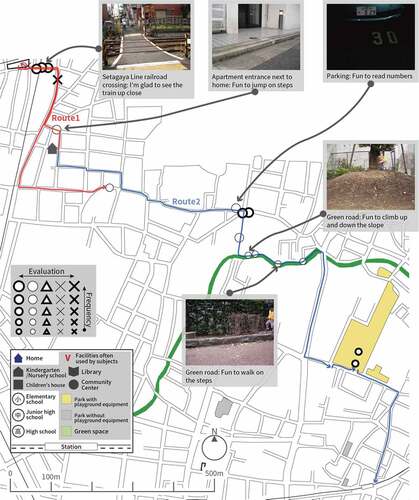

4.2.1.2. Walking space from the viewpoint of route selection when going out

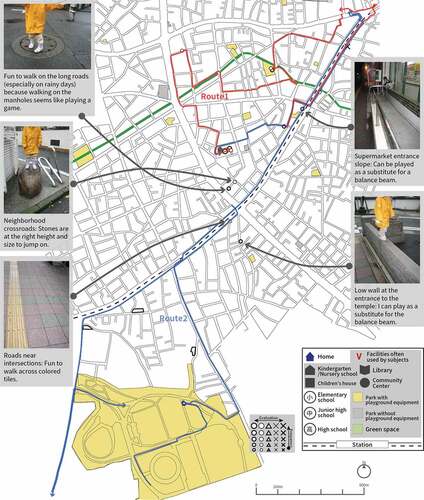

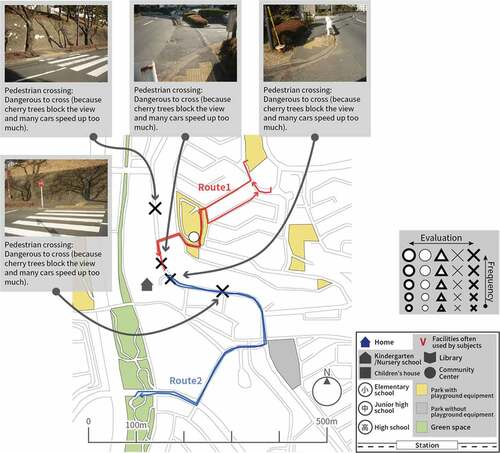

, , are typical examples of the three survey subjects in the Sangenjaya area.

Case 1 () is of a parent raising a 3-year-old child. Their walking route of two days is recorded. In Route 1, the destination is a nearby park, and the outbound and inbound routes are different. In Route 2, the train goes home via the nursery school and park, and the outbound and inbound routes are different.

Case 2 () is a parent with children aged 6 and 3; the 6-year-old attends an elementary school, and they took pictures only when they were out with the 3-year-old child. In Route 1, the destination is around the station and the park, and the outbound and inbound routes are different. In Route 2, after leaving the Sangenjaya area and moving a distance, they head to the station via a large park. In these two cases, because the destinations are far apart, the outbound and inbound routes are not as usual, and the ratio of taking pictures in the walking space is high (in case 1, 14 out of 19 cases, and in case 2, 9 out of 16 cases). In addition, there is a tendency for the percentage of positive evaluations of walking space to be high. In Case 1, 13 out of 14 were positive evaluations, and in Case 2, 8 out of 9 cases were positively evaluated.

In Case 3 (, 2-year-old child), Route 1 follows a similar route; that is, the outbound route to the station and the inbound route are partially different. In Route 2, only the return route is recorded, but it follows a route similar to that of Route 1. In the case mentioned above in the Sangenjaya district, the route went around the house while passing through the destination, but in Case 3, the round-trip routes overlapped. Of the 12 photographs taken, 3 were of the walking space, all of which gave a negative evaluation in terms of “movement.”

From the above cases, the ability to select various routes when going out to different destinations is an opportunity to recognize various elements of the walking space. It also positively affects children’s activities. On the overlapping routes, there is little awareness of the walking space itself, and it is presumed that the focus is on “moving” actions.

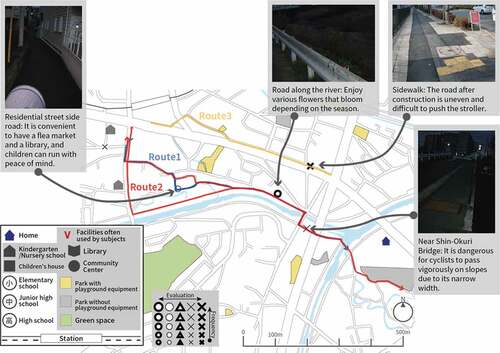

4.2.2. Tama NT district

4.2.2.1. Walking space as seen from photos and description

shows the results of classifying the photographs and descriptions taken in the Tama NT area.

One of the physical environment characteristics in the Tama NT area is that it has a pedestrian deck. An analysis was conducted on how the maintained road, which runs from the station to the complex, influences the recognition and evaluation of parents and children who give importance to pedestrian convenience. Regarding the percentage of places where the photo shoot was done, the number of shots taken on general roads was the highest (48.1%), followed by pedestrian decks at 26.58%. There was a big difference in the evaluation. While the promenade was very satisfactory (75%), the pedestrian deck was positively evaluated by 61.9%, and the general road by 36.84%, which is a significant difference. The positive evaluation of the general sidewalk was very low compared to other areas. Such results reflect the regional characteristics, such as relative anxiety and dissatisfaction in terms of safety due to the presence of cars and bicycles because they are accustomed to an environment without vehicles. Negative evaluation of the general sidewalk is different from other areas because the sidewalk can be seen in the “play” scene (). “Play” in the walking space, which is often seen in all areas, includes “sitting, climbing, jumping, and having fun,” and “trying to balance on a narrow step.” In the Sangenjaya and Seiseki-Sakuragaoka areas, such photographs were evaluated as positive, but in the Tama NT area, there were both positive and negative evaluations.

With regard to the Sangenjaya area, the description of “movement” in the pedestrian space was mainly related to safety and convenience. The evaluation was positive as in “the outlook is good, there are a lot of people, and I can take a walk comfortably” and “easy because there are no steps and slopes.” There were also negative evaluations such as “the visibility is poor and the car is speeding up and it is very dangerous to cross” and “the sound of trees is hitting the asphalt, the stroller is rattling, children are stumbling, and the sidewalk is dangerous.” There were many conflicting opinions.

4.2.2.2. Walking space from the viewpoint of route selection when going out

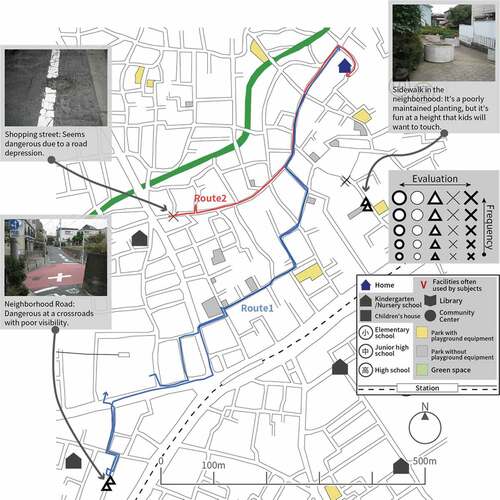

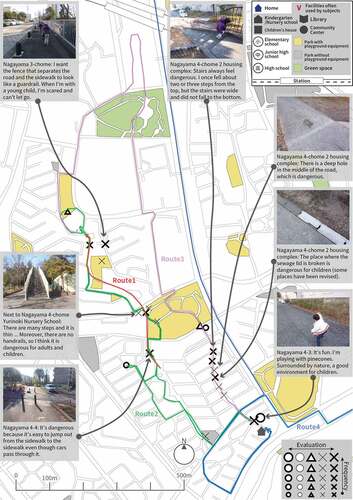

, and show three representative survey subjects in the Tama NT area.

Case 4 () is the case of a parent raising three children aged 8, 6, and 1. Route 1 leads to the kindergarten, and Route 2 to the nearby park. In Route 1, the outbound and inbound routes are partially different near the kindergarten, but the others than that part are duplicated, and in Route 2, all the round-trip routes are duplicated.Similar to the case of in the Sangenjaya area, the monotonous route was selected, and four out of five total evaluations were done of the walking space, all of which were negative and were photographs related to “movement.”

In Case 5 (, children aged 12, 8, and 4), various outgoing patterns are recorded. In Routes 1 to 4, all routes are different, and various walking spaces are selected.

Taking each route and evaluation into consideration, participants photographed Routes 1 and 2 frequently around the route to the kindergarten. On the other hand, in Cases 3 and 4 where a bicycle is used to go to a relatively distant place, no photograph is taken, and it is expected that the surrounding environment is hardly recognized. In addition to the cases shown in , there are many cases of going out of the Tama NT area, and it is presumed that parents and children have few opportunities to come into contact with environmental factors when traveling by bicycle or car. Participants traversed Routes 1 and 2 on foot and took a total of 30 photographs, 11 of which were evaluated in the pedestrian space. Among them, there was only one opinion about children’s play, and the other 10 were all descriptions about “movement,” and the evaluation was negative.

Similarly, in Case 6 (, children aged 3 and 1), various routes were selected, but no photograph was taken when going far. Promenade spaces were mainly interpreted as spaces for “movements” (Route 1 and 2), and evaluations of residential areas were positive, and negative around the complex. Among the three cases, those in Cases 4 and 6, who lived near the complex, routinely moved to (used) the complex because of the facilities and parks therein. However, some opined that the complex was inconvenient because the pedestrian paths and lanes were divided. In this regional background, it is considered that the walking space was widely regarding as a “movement” space for parents and children.

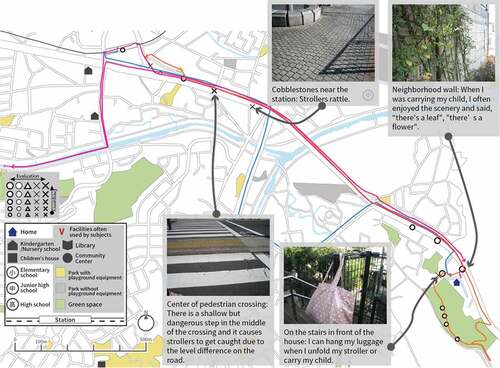

4.2.3. Seiseki-sakuragaoka District

4.2.3.1. Walking space as seen from photos and description

and show the evaluation of the photographs taken in the Seiseki-Sakuragaoka area. Since the promenade was not maintained in the Seiseki-Sakuragaoka area, all photographs were taken on ordinary roads. Owing to the absence of promenades in the region, 44.9% of overall evaluations were negative, which was the highest, compared to other regions. Since there was no promenade, the percentage of shots related to “play” was low (Sangenjaya district: 42.7%, Tama NT district 41.77%, Seiseki-Sakuragaoka district: 28.57%), and it was evaluated mainly for “movement.” As with other areas, the evaluations related to movement were mainly negative due to the presence of cars and bicycles, road outlook, and unevenness of the road surface.

4.2.3.2. Walking space from the viewpoint of route selection when going out

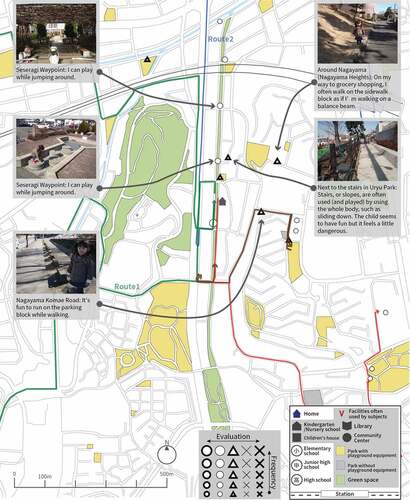

, and are plots of the cases of the three survey subjects in the Seiseki-Sakuragaoka area.

Case 7 () is a part of the position and the route of a parent with a 7-month-old child. In Case 1 they travel far by train and only the route of the walk to the station is shown. Although Case 2 is only of the return trip, the main street near Seiseki-Sakuragaoka Station is used; it is recognized as a moving space as in the comment “I’m about to fall off a step.” In the stream behind the alley, there was a description such as enjoying the elements of nature (Case 3). In addition, the evaluation of indoor facilities used by children, such as children’s halls and libraries, is notable.

Case 8 () is the case of a parent raising a one-year-old child. Round-trip routes were recorded in Cases 1 and 2, and only outbound routes were recorded in Case 3. The destination of all three cases was the station likely because of the nearby commercial facilities such as supermarkets. An interview survey conducted later revealed that welfare facilities were also the main destinations, such as visiting commercial facilities around the station on the opening day of the nursery school. Such facilities are located on the west side of the station. Of all the cases, Cases 1 and 2 had routes that were a detour to the station. Case 3 seems to have had a relatively short travel route, but in two of the three cases a route was chosen, that could be used safely and with peace of mind, enjoying the elements of nature even if a detour was made as in Cases 1 and 2.

Case 9 () is an example of a one-year-old child (and its parents). Strollers affect the evaluation of the urban environment. All three recorded cases had stations as destinations (or transit stops); thus, all destinations were limited.

While there were many overlaps in route selection, the contents of the evaluation were mainly photographs related to movement because the child was young. There were many positive reviews of the low-rise residential areas and green areas around the house, and there were many negative reviews on the road leading to the station. In the Seiseki-Sakuragaoka area, the area around the station had characteristics similar to the Sangenjaya area as a naturally occurring area. There was a part where relatively free route selection was performed. There were some areas where it was difficult to select a route due to natural factors such as rivers, slopes, and large-scale green spaces, and such areas were said to be mixed. Therefore, no clear characteristics were found pertaining to the route selection compared to the Sangenjaya and Tama NT areas, and it seems that the characteristics of both areas were partially mixed. However, in the case of Tama City, street furniture such as benches are installed on the side of the road according to the road maintenance plan, making a positive assessment in terms of convenience, from the perspective of parents who go out with their children.

5. Discussion

5.1. Common characteristics of recognition and evaluation of pedestrian space in residential areas

In many cases, the “walking space” is regarded as the main place to move. The specific content can be broadly divided into safety and convenience. Safety is based on cars/bicycles, outlook, road surface maintenance, and various components on the road; many of the evaluations were negative. There was no difference in the content of any region. In other words, it can be said that many parents raising children have a common sense of value regarding safety in a child-rearing environment.

Next, most of the evaluations regarding convenience are mainly related to the use of strollers, and these evaluations are divided depending on whether the use is convenient or inconvenient. Therefore, as the number of stroller-users increases, so does the number of recognitions and evaluations regarding convenience.

Of the photographs taken in the “walking space” the most numerous photographs following movement are related to [play]. As for the specific comments, those relating to enjoying the view, such as “seeing the train” and “the flowers are beautiful,” and enjoying playing, using the components of the road, were most often seen. Most of the play using the road components captures scenes of climbing and descending steps and slopes and crossing moats, and such photographs were taken in common in all areas. Parents positively perceive such play behavior in the walking space, and the degree of satisfaction is higher than the role of the original walking space as a “moving” place.

5.2. Route selection by geographical factors

Not all participants borrowed cameras for the same period, so it was difficult to claim that pictures were obtained under the same conditions. However, data showed that people in Tama NT and Seiseki-Sakuragaoka area often used bicycles, cars, and subways to travel far. The daily life of the participants living in Tama City covered a wider area and therefore, they were asked to take pictures. When going out by bicycle, car, train, etc., the chances of recognizing the surrounding environment naturally decreases. Therefore, it was presumed that the walking space was often regarded as a “moving space.” In terms of the Tama NT area, pedestrian roads and vehicle roads are separated within the residential complex, guaranteeing pedestrian safety; however, since there is a clear boundary between the complex and the outside area, it creates an obstacle for parents and children when selecting a route. In addition, in an environment where the same dwelling style is repeated within a housing complex, there were several descriptions of “movement” in the pedestrian deck inside.

5.3. Diversity of parent–child route selection and evaluation characteristics ()

The survey subjects in the Sangenjaya area have various destinations, and there are various routes from which to choose. Depending on individual needs, the shortest route can be selected when in a hurry, and the route can be selected as a walking space when relaxing. In the latter case, it is more meaningful to use the walking space for a child to “play” in than as a place for “movement.” Therefore, the path is regarded positively from various perspectives; for example, it becomes a play area and the houses in the neighborhood become a kind of landmark, thus helping the town be positively regarded.

Table 4. Characteristics of parent–child route selection and evaluation.

In the Tama NT area, people often travel by bicycle or car instead of walking. In such a case, because the walking space is regarded as a “moving” space for the parent and child, the round-trip routes often overlap. In addition, many photographs with negative evaluations were taken when the round-trip routes overlapped.

As mentioned above, there are various aspects of recognizing the parent–child environment in each region. In addition, such differences in perceptions and evaluations are considered to be affected by the local environment.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we interviewed parents and asked them to evaluate the “child-rearing environment” in areas with different geographical conditions using the caption evaluation method. We classified the images they sent to us according to “location.” From the photographs, we determined the features and issues in the “moving space.” First, we found no regional difference in “safety” and “convenience”; there was a common and clear evaluation standard. Convenience is often associated with strollers. Regarding children’s play, many places had walking paths and the places were developed by utilizing the characteristics of the environment, such as the sight of a train. The regions had different concrete areas. In the Sangenjaya area, the concrete area was often used as a playground for children, not as a walking space. Therefore, it is presumed that the degree of satisfaction with the walking space is high, and the need for individual parks is not high.

The Tama NT District has many hills, making it difficult to recommend for walking with a child. However, as children in modern society are losing their physical strength and outdoor activities demand the movement of their bodies, various functions of walking spaces are also needed.

Our study corroborates other studies on the safety of children. Globally, parents’ awareness of “safety” remains unchanged regardless of the age of the child. In this study, we used the caption evaluation method to determine the proportion of “safety” in evaluating the environment. In addition, it is easy to assume that negative evaluations regarding safety in the walking environment will prevail, but the walking space is an extension of a defined playground such as a park, and it is not always considered negative. By using the caption evaluation method, it was possible to visualize the evaluation structure from various perspectives. Thus, it can be used to develop measures for environmental improvement that match the environmental characteristics of the region.

Finally, we discuss the limitations of this study and future research directions. First, participants’ photo-taking occurred in different periods. Owing to climate change in Japan, participants’ “going out” was affected by the seasons and the weather. Therefore, future research should conduct a more detailed analysis by considering the climate factors and setting a certain period for the survey. Second, the GPS information in the photographs varied among the participants. At the time of the survey, there was no model that could record GPS information on a digital camera. Participants were not asked to take pictures while carrying the camera and GPS receiver separately. The accuracy of GPS was lower at the time of the survey than it is now, and it is accurately recorded when walking around the participant’s home; however, when using public transportation, the speed could not be maintained and accuracy dropped. Therefore, in this study, mainly the route around the home was analyzed, where accurate information could be obtained. In modern times, everyone owns a smartphone, and it has become easier for smartphones to take pictures that can record GPS information. In future, it will be possible to analyze more accurate data by actively utilizing IT, such as by setting a viewpoint and period and using one’s own smartphone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sungeun Cho

Sungeun Cho is an Assistant Professor at Toyo University. Her research interests are architectural planning and Children's environment.

Kazuhiko Nishide

Kazuhiko Nishide is an Emeritus Professor at The University of Tokyo. His research focuses on architectural planning and the behavioral basis of environmental design for human beings.

References

- Bringolf-Isler, B., L. Grize, U. Mäder, N. Ruch, F. H. Sennhauser, and C. Braun-Fahrländer. 2010. “Built Environment, Parents’ Perception, and Children’s Vigorous Outdoor Play.” Preventive Medicine 50 (5–6): 251–256. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.03.008.

- Derr, V., and E. Tarantini. 2016. “Because We are All People”: Outcomes and Reflections from Young People’s Participation in the Planning and Design of Child-friendly Public Spaces.” Local Environment 21 (12): 1534–1556. doi:10.1080/13549839.2016.1145643.

- Elshater, A. 2018. “What Can the Urban Designer Do for Children? Normative Principles of Child–friendly Communities for Responsive Third Places.” Journal of Urban Design 23 (3): 432–455. doi:10.1080/13574809.2017.1343086.

- Koga, T., A. Taka., J. Munakata., T. Kojima., K. Hirate, and M. Yasuoka. 1999. “Participatory Research of Townscape, Using “Caption Evaluation Method”: Studiesof the Cognition and the Evaluation of Townscape, Part 1.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 64 (517): 79–84. (In Japanese). doi:10.3130/aija.64.79_2.

- Krishnamurthy, S. 2019. “Reclaiming Spaces: Child Inclusive Urban Design.” Cities & Health 3 (1–2): 86–98. doi:10.1080/23748834.2019.1586327.

- Malone, K. 2013. “‘The Future Lies in Our Hands’: Children as Researchers and Environmental Change Agents in Designing a Child-friendly Neighbourhood.” Local Environment 18 (3): 372–395. doi:10.1080/13549839.2012.719020.

- Matsuhashi, K., K. Ohara, Y. Fujioka, N. Miwa, and S. Taniguchi. 2006. “Study on the Childcare Support Center as A Comfortable Place for the Parent and Child in Urban Area: From Analysis of Out-home Life in Mitaka-city, Tokyo.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 71 (600): 25–32. (In Japanese). doi:10.3130/aija.71.25_2.

- Ohmori, N. 2015. “Mitigating Barriers against Accessible Cities and Transportation, for Child-rearing Households.” IATSS Research 38 (2): 116–124. doi:10.1016/j.iatssr.2015.02.003.

- Sato, M., K. Nishide, and T. Takahashi. 2004. “A Study on Children and Environment through Transition of Playgroups: A Study on the Interaction between Children’s Ways of Becoming Members of Society and Space Part 2.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 69 (575): 29–35. (In Japanese). doi:10.3130/aija.69.29.

- Tappe, K. A., K. Glanz, J. F. Sallis, C. Zhou, and B. E. Saelens. 2013. “Children’s Physical Activity and Parents’ Perception of the Neighborhood Environment: Neighborhood Impact on Kids Study.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 10 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-39.

- Yamada, A., E. Satho, M. Sato, and A. Hinuma. 2008. “Management Conformation, the Mixture of Children of Short-And Long-Hour Daycare, Activity Place Changes at Integrated Facilities within Functions of Nursery School and Day Nursery.” Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ 73 (625): 543–550. (In Japanese). doi:10.3130/aija.73.543.

- Yun, J., B. Min, M. Kita, and T. Suzuki. 2005. “Activity and Resource: Alternative Views on the Analysis of Children’s Activity in Neighborhood Environments.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 4 (2): 315–322. doi:10.3130/jaabe.4.315.