ABSTRACT

The main focus of this article is on the changes that occurred to firebreaks planned in this context of continuity of colonial space after Seoul’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule. This study aims primarily to investigate the changes to or the persistence of Seoul’s spatial structures after liberation. Also examined is the process by which the municipal administrative authorities in Seoul separated from the legacy of Seoul’s colonial past through the dismantling of the remnants of the Japanese colonial period. The results of the study should provide a basis for understanding the prestige and magnitude of administrative competence in Seoul immediately after liberation. This article interprets the period through a direct comparison of Korea’s urban space during colonization and after liberation.

1. Introduction

Seoul, the area under study in this paper, was called Gyeongseong during the Japanese colonial period. Seoul witnessed urban planning under the Government-General of Joseon (Japanese colonial government in Korea; hereafter, the “Government-General”) until August 1945. The traces of this planning remain in the current urban structure of Seoul. The Government-General, which carried out its urban renewal projects under the Decree of Urban Area Restructuring in the mid-1930s, revamped them into anti-air raid urban planning as the Pacific War became a bombing campaign. In 1937 the Urban Planning Act was enacted pursuant to the Air Strike Defense Law as a temporary measure against possible air raids. However, given the uncertainty about when and where enemy bombers would launch attacks, Japanese urban planners focused on the preparation of preventive measures aimed at minimizing casualties and fires from bombing rather than urban renewal. As a result, the city was interspersed with open spaces and streets that would serve as firebreaks in case of air strikes.

The main focus of this article is on the changes that occurred to the firebreaks planned in such a context after the liberation from Japanese colonial rule. Previous studies have mostly focused on the modern era and Gyeongseong (the name of Seoul during the Japanese colonial period) as historical and geographical settings, respectively that is, as a temporal background and a spatial background. Typically, they analyze urban planning on the Korean peninsula during the Japanese colonial period (Sohn Citation1990) or examine Gyeongseong urban planning in the context of contemporary Seoul (Yeom Citation2016). Research that analyzed the spatial heritage of the Japanese colonial period from a social history perspective are especially significant for research methodology (Kim Citation2009, Citation2010; Todd Citation2020).

Research on post-liberation Seoul is limited to the sociological aspects of population influx (Lim and Kim Citation2015); no research has been undertaken on its spatial structure. To bridge this research gap, this study aims primarily to investigate the changes to or persistence of Seoul’s spatial structure after liberation. In addition, it examines the process by which the municipal administrative authority in Seoul separated from the legacy of Seoul’s colonial past through the dismantling of the remnants of the Japanese colonial period. Although previous studies criticized the “continuity and discontinuity” of the modern and contemporary, there was no contemplation with regard to the “wartime legacy” and “negative heritage” specific to this paper. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to fill the gaps in the research regarding history’s “continuity and discontinuity” over the changes or continuation of spatial structures after the 1945 liberation. The results of the study results should provide a basis for understanding the prestige and magnitude of administrative competence in Seoul immediately after liberation. It examines in particular firebreaks, a legacy developed during the Pacific War under Japanese colonialism and what these spaces became after the war ended.

2. The urban structure and firebreak planning in Gyeongseong during the late Japanese colonial period

2.1. The urban structure of Gyeongseong

Under the Government-General, Gyeongseong underwent continuous urban planning and spatial restructuring starting with road projects in 1911. In 1912 a radial road network was formed – with a square at Hwanggeumjeong-3-jeongmok, present day Euljiro 3-ga as its hub – as a result of this Gyeongseong street improvement project. The grid-type road network was also designed in an attempt to change the spatial structure of Joseon (Yeom Citation2016, 25–39). In 1920 the Government-General expanded the urban structure of Gyeongseong, with the city undergoing restructuring at the block level (Yeom Citation2016, 89).

After expansion through urban renewal projects under the Decree of Urban Area Restructuring, Gyeongseong developed at the district level with district-specific characteristics. In the eastern district, Cheongnyang-ri and Wangship-ri were designated as light-industrial and industrial zones, respectively, and the district south of the Han River was designated as a residential area backing the industrial zone. In the western district, Mapo/Yonggang was designated as an industrial and light-industrial zone and Yeonhi/Sinchon-ri as residential. This series of city restructuring was implemented within the context of railroad and transportation systems completed earlier. Thus district-wide city development was managed in conjunction with the road network and land-plot reorganization projects, geared towards ensuring a smooth transition between expanded and existing parts of Gyeongseong and solving the housing problems in the aftermath of a mass influx of people into the capital (Yeom Citation2001, 245–246).

However, these projects, established in 1934, encountered difficulties with funding and the provision of raw materials during the phase of full-scale implementation. Furthermore, in the wake of the beginning of the 1937 Sino-Japanese War, Joseon was also placed into wartime conditions, and investment in urban planning had to be reduced. The Namsan roundabout route project, which was the first road project launched in 1937, ended up being officially terminated in 1943 much more an interruption of the project than its completion. In addition, with the outbreak of the Pacific War, the wartime conditions that had begun with the Sino-Japanese War continued, and the city restructuring and plot reorganization projects were ended in the face of the zeitgeist and the demands of the country.

2.2. Firebreak planning

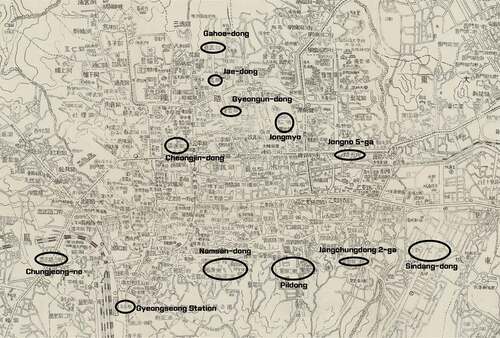

The conditions after the Sino-Japanese War had a great impact on Gyeongseong’s urban planning. Post-1930s warfare was dominated by bombing raids. Threat of air strike was reflected in “regulations concerning structural facilities for buildings within the fire protection area” in the 1937 Decree of Urban Area Restructuring (Sohn Citation1990, 311–313). This was later presented by the Government-General as the enforcement decree to the air defense act (Government-General of Joseon Notification No. 181). With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Japan began to arrange structural planning against air strikes. However, urban planners could not present any measures beyond demolishing buildings to secure open spaces as firebreaks. Apart from this, parks were planned in densely populated areas to reduce damage from air strikes, and an attempt was made to secure open spaces that were as large as possible by creating scenic areas on the outskirts of Gyeongseong (Yeom Citation2016, 217). However, these plans were prematurely terminated for lack of funding, as mentioned above ().

Figure 1. Gyeongseong air defense city planning chart.

By the time Joseon was liberated from Japanese colonial rule, Japan had achieved the publication of firebreak guidelines to minimize damage. On 4 April 1945, the Government-General announced the city firebreak guidelines and designated major cities, including Busan, Gyeongseong, and Pyeongyang, as regions that would be subject to firebreak measures. In the official gazette of 7 April 1945 (Government-General of Joseon Notification No. 196), five areas were designated as firebreak spaces in Gyeongseong: the Jongno Seosaheon-jeong firebreak belt (Jongno-2-jeongmok to Seosaheonjeong), the Jongmyo Daehwajeong firebreak belt (Jongmyo to Daehwajeong-2-jeongmok), the Gyeongunjeong Namsanjeong firebreak belt (Gyeongunjeong to Namsanjeong-3-jeongmok), the Gyeongseong Station Jukcheomjeong firebreak belt (Gyeongseong Station to Junkcheomjeong-3-jeongmok), and the Gyeongseong Station Ganggijeong firebreak belt (Gyeongseong Station to Ganggijeong). Each firebreak belt was planned to have a width and length between 30–50 and 1,000–1,800 meters, respectively. Along with this, regulations that restrict the installation of structures in empty firebreak spaces were announced one after another (Government-General of Joseon Notification No. 208). This project resulted in the demolition of buildings and houses, leaving barren land behind. These open spaces remained an aggravating urban problem after liberation.

3. Absence of urban planning under the US Military Government

3.1. Absence of urban planning

After liberation, the United States Army Military Government in Korea (hereafter, the “US Military Government”) was established in South Korea, and the municipal administration of Seoul began when Beom-seung Lee took office as mayor. Lee worked at the Production Increase Bureau (Siksankuk) of the Government-General of Joseon and as the industrial director of Hwanghae-do. After liberation, he served as Gyeongseong’s deputy mayor and the first police chief of the Yangju Police Station.

The Charter of the City of Seoul was proclaimed on 16 August 1946, and administrative restructuring was announced on October 26, pursuant to the Charter (The Dong-A Ilbo, 15 August 1946). As a result, Seoul was separated from Gyeonggi-do and given authority as a municipal government. Seoul became Korea’s social, political, and cultural hub as its capital city after liberation, undergoing a sudden population increase and spatial expansion.

With the proclamation of the Charter of the City of Seoul, Gyeongseong was renamed Seoul and separated from Gyeonggi-do; after regaining its status as the capital on 2 October 1946, one of the first projects was to begin renaming streets and administrative units. The Japanese-style names jeong, tong, and jeongmok were changed to dong, ro, and street, respectively, returning to older names and receiving new names. In particular, it was suggested that roads bearing Japanese personal names should be replaced with Korean names and streets with historically significant names: Sejong-ro, Eullji-ro, Wonhyo-ro, Chungmu-ro, Teogye-ro, and Chungjeong-ro were suggested and implemented (The Dong-A Ilbo, 18 December 1946).

Apart from this renaming, however, no urban planning was undertaken to improve Seoul as a “free city.” In the three years following liberation, during which the greatest part of the government administration was in the hands of the US Military Government, all construction-related departments and the division of urban planning inevitably focused on refurbishing the buildings managed by the US Military Government (Kim Citation1975, 31) and repairing damage across the city (The Dong-A Ilbo, 9 May 1946). Even if they wanted to repair the destroyed firebreak roads and empty spaces there was a lack of materials, and as most of the manpower was used for the cleaning and collection of the widespread trash at the time, the restoration of the firebreak empty spaces were given a lower priority (Seoul Historiography Institute Citation2017, 127). The urban planning of Seoul could not move forward due to complex issues such as these, and this led to a situation where the spatial heritage of the Japanese colonial period could not help but be neglected.

This part describes the absence of a city plan after the liberation during the US Military Government era. After the renaming of the streets and city dongs, a bare-bones city government reorganization was instituted. City planning in its fullest meaning could not be attained due to a lack of resources, manpower, and budget. For this reason, this paper points out the failure to carry out the plan to clean up the spatial legacy of the Japanese colonial period, with it instead being left abandoned.

3.2. Abandoned firebreaks

That the US Military Government had little interest in the restructuring of Seoul is demonstrated in the removal of the firebreak belts interspersed throughout Seoul. At the time of liberation, Gyeongseong was in an untidy state of unfinished anti-air raid structures and firebreak belts spread across the city, with littered plots of demolished houses abandoned along zigzagging lines (Sohn Citation1990, 336).

In fact, post-liberation Seoul was suffering from various inconveniences because of the abandoned firebreaks. Even three years after liberation, when Seoul’s population had increased substantially, the firebreaks were left abandoned and became trash dumps, raising serious traffic and hygiene problems (The Dong-A Ilbo, 8 February 1947). By 1948 abandoned firebreaks amounted to 72,500 square meters, and no plan had yet been announced (The Dong-A Ilbo, 6 June 1947). This negligence was directly related to an absence of urban planning itself. The Ministry of Civil Engineering, which was in charge of the project at that time, was unable to arrange a plan for the city, and the restructuring of zoning for the city was not yet in place, delaying the reorganization of the land lots and, thus, the removal of the firebreaks (The Dong-A Ilbo, 13 January 1948). That is, the delay in rearranging the blocks, the most basic element of any urban plan, was the direct cause of the negligence regarding the removal of firebreaks.

The fact that the abandoned firebreaks were still not taken care of and neglected after Seoul was designated a special city provides various implications. On the surface, while it may seem that the spatial heritage that was established during the colonial period was being neglected, a comparison with North Korea, which had mostly solved the abandoned firebreak problem during the same period, shows that the reason the abandoned firebreak restoration project was delayed was “liberal democracy” espoused by South Korea (The Dong-A Ilbo, 8 February 1947).

The US government, Korean government officials, and political factions on the right and the left coexisted in Seoul at the time. During the 1945–46 period, when discussions on urban planning should have been in full swing, the relationship between the first mayor Beom-seung Lee and the US official lieutenant colonel Wilson was strained (Seoul Historiography Institute Citation1997, 228), and the fact that there were a lot of leftist officials in the Jeongchongdae, which had been replaced with Joseon people, making the group uncooperative to city administration policies, also acted as a reason why urban planning did not go smoothly (Kim Citation1959).

Conflicts existed after this even during the process of establishing a government. While the relationship between the military government and the city hall was good after Hyung-min Kim, who had studied abroad in the US, became mayor on the recommendation of Major General Lerch, the conflict between the mayor, who called for the elimination of dong associations, and the alliance of dong associations had a negative impact on the city administration (The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 23 March 1947).

This is the point where the processing of firebreak empty spaces and the urban planning project could not help but be delayed under liberal democracy, where the nation needs to be run reflecting the voices of the military government, city administration, and the citizens, compared to North Korea which conducted urban reconstruction using a top-down approach. Such ways of handling firebreak empty spaces can be said to be the point where the varied aspects of Seoul immediately after the liberation, which cannot be defined simply through decolonization and neglect, can be seen.

This does not mean that there was no plan to dispose of the firebreaks. Well aware of the landscape and hygiene problems that might emerge from the presence of the firebreaks, the City of Seoul did plan, in March 1946, shortly after the liberation, to turn all the firebreak belts into roads and parks and all open spaces into parks (The Dong-A Ilbo, 18 March 1946). Parks were planned for in the following places: behind Pagoda Park, Jongno-3-jeongmok, behind Bonjeongseo, behind the old Gyeonggi-do Government building, behind the old Post Bureau building, behind the Telegraph Bureau building, behind the Seoul Newspaper building, behind Seoul City Hall, next to the Seodaemun Police Station, next to the Savings Bank, and behind the Central Post Office. This plan could not be implemented because it did not receive budget approval (The Dong-A Ilbo, 20 May 1946).

For this reason, until 1947 measures taken by the municipality of Seoul regarding firebreaks were limited to the prohibition of unauthorized housing, or any other type of construction, and the demolition of illegally constructed buildings (The Dong-A Ilbo, 26 September 1947). However, public opinion was not favorable because of insufficient compensation for demolished houses (The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 13 January 1948). From early 1948 onwards, strategies were established to dispose of the most problematic firebreaks even without budgetary approval. The 1948 budget of Seoul, subtracting the education budget, was about 1.4 billion won in 1948; a special accounting item of about 202 million won was fixed as the budget for the removal of firebreaks (The Dong-A Ilbo, 27 March 1948).

Firebreaks posed serious urban hygiene and landscape problems and their removal was on the agenda repeatedly. Owner compensation was also a compelling problem that needed to be addressed by the government. However, in the years leading to the formation of the government of the Republic of Korea, the municipal administration was also in the hands of the US Military Government. It was structured around the Central Department, within which the Department of Construction was installed, and it played the role of Government-General Secretariat and Building and Repairs Division. The architectural division was subdivided into the construction, design, and repair units. The Department of Construction of the US Military Government completed little or no new construction, and repairs were provided primarily only where absolutely necessary (Lee Citation1993, 33).

As mentioned previously, most municipal engineering projects during the US Military Government concentrated on street repairs and the water supply and sewer system (The Dong-A Ilbo, 5 February 1947). That is, the municipal administrative projects were geared towards “repairs” rather than towards “planning.” Likewise, the US Military Government could not cope with the housing and urban problems arising from the mass influx into Seoul of people displaced from North Korea and repatriated Koreans in the wake of liberation, and it sought solutions to the problems facing Seoul by addressing the most urgent problems. The first problems that had to be solved by the post-liberation Korean government and the US Military Government were population dispersal and reasonable and adequate allocations of urban facilities and institutions to solve the problem of mass influx and the related problems of traffic, hygiene and security. This situation made the plan for the “free city” of Seoul a secondary problem (the Monthly Review of Municipal Policy, 5 January 1949, 9–12).

This describes the neglect of the firebreaks amidst the absence of a city plan. After that, it explains the implications of this neglect and then the maintenance plan and discussion over its treatment are described. Furthermore, it implies that the discussion can be continued to the city planning of the government of the Republic of Korea after its establishment. It also mentions that after the liberation during the US Military Government era, even if there was a city plan, just like that of the Japanese rule, it had the characteristic of focusing on repairs rather than on planning and new building projects.

4. Urban planning after the establishment of the Republic of Korea

4.1. The expansion of Seoul

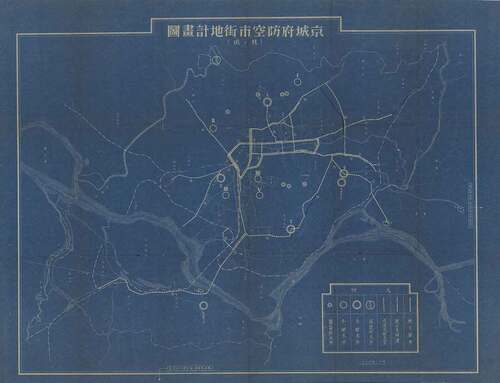

Seoul, which had been left in a neglected state until the establishment of the government of the Republic of Korea on 15 August 1948, launched a systematic urban plan with the creation of the Urban Planning Department. The first project was the expansion of Seoul (The Dong-A Ilbo, 3 August 1949). The City of Seoul incorporated four surrounding areas (Ddukdo-jigu, Eunpyeong-jigu, Sung’in-jigu, and Guro-jigu) belonging to Goyang-gun and Siheung-gun, with Gyeonggi-do covering 13.3 km2 of new areas of the city after the proclamation of the Local Autonomy Act on 4 July 1949 (Lee et al. Citation1999, 35). On 27 December 1949, pursuant to Notification No. 7 of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, a total area of 269,770,641 m2, including these four areas, was designated as an urban planning district (The City History Compilation Committee of Seoul Citation1972, 340; and ).

Figure 2. The expansion plan of administrative areas and urban planning district units (1949).

Table 1. Comparison of before and after the 1949 area expansion.

The purpose of the 1949 expansion of urban planning areas was the creation of land to accommodate a population of two million by expanding the administrative area and adjusting the area of the urban planning district to cope with rapid population growth after liberation. The goal was also to implement Seoul-Incheon integrative urban planning, which had been on the agenda for several years, along with designating the areas nearer Anyang (and which centered around Yeongdeungpo-gu) as industrial areas and the Gwangjang-ri area (upstream along the Han River and nearer Kimpo) as residential (The Dong-A Ilbo, 17 February 1949). This systematic expansion plan could not be established because decisions on accompanying urban projects, such as the street network, water supply, sewer system, parks, and schools, were lagging. That is, urban planning as pursued by the Urban Planning Committee could be established only after solving the many different large and small infrastructure problems, such as the lack of water supply and sewer facilities, the unreasonable designation and abolition of scenic areas, unauthorized restoration and construction of streets, illegal construction of church buildings encroaching on park areas, and the connivance of regulatory authorities (The City History Compilation Committee of Seoul, Citation2016, 134).

4.2. Removal of firebreaks

Once geographical expansion was implemented, the municipal government of Seoul began to dispose of the long-standing nuisance of the firebreaks. It announced at the beginning of 1949 that it would launch a road construction program as one of the three major city plans. This was done by disposing of all firebreaks across Seoul. Of the 26 firebreaks selected as causing urban landscape and hygiene problems, the city began with the eight firebreaks located at the core of the city (The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 17 February 1949). First, the land ownership was clarified: if the land lots had owners, the city bought them from the owners, and those previously owned by the Japanese were nationalized (The Dong-A Ilbo, 10 June 1949). Second, the street borders were clearly defined and the streets expanded. Third, buildings constructed on firebreaks without a permit were demolished. The removal of firebreaks, which had been hampered by budgetary difficulties, started at full throttle when Mayor Chang-young Yoon assigned 528,488,560 won as a special accounting item for the firebreak removal project (Seoul Notification No. 29, 2 May 1949). The eight sites included in the first round of firebreak removal were the firebreak belts from Jongmyo to Chunggindong, Jongmyo to Pil-dong, Gyeong’un-dong to Namsan-dong, Jongno-5-ga to Jangchungdong-2-ga, Pil-dong to Sindang-dong, Cheonjin-dong, Seoul Station to Chungjeong-ro, and Je-dong to Gahoe-dong. A budget of 146,110,000 won was allocated for this project, which was planned to be completed in the same year (The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 18 February 1949).

The work of turning firebreak belts into streets continued throughout 1949. One of the reasons for this rapid street construction immediately after the formation of the government is the existence of related projects of the US Military Government, although they could not be implemented. One of those projects was the designation of urban planning areas in 1947, including the removal of firebreaks and plots earmarked for parks. At that time, 11 firebreaks were included in the repair plan, but they were not part of the municipal budgetary problem (21 August 1947, Chosun Choong’ang Ilbo). Immediately after its formation, however, the government prioritized the rapid realization of the long-cherished project, postponed for three years, and fixed the budget for the removal/repair of firebreaks in order to accelerate the process ( and ).

Table 2. 8 firebreak locations that were designated for priority removal.

4.3. Full-scale city restructuring program

As the City of Seoul was pushing its city renewal program forward at full throttle, the government installed the Urban Planning Committee in October 1949 under the Department of Construction to make Seoul a functional capital of South Korea (The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 22 July 1949). In fact, the Urban Planning Committee already existed when the Charter of the City of Seoul was proclaimed: a nominal organization under the title of the Municipal Urban Planning Committee (The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 26 October 1948). The Urban Planning Committee invited experts in all fields of civil engineering and construction to participate in Seoul’s urban planning; it consisted of 90 experts, including Jeong-keun Park, Dong-won Kim, Chi-young Yoon (1898–996), Sung-ha Hong, and Woo-jeong Yang. The committee aimed to investigate and review matters related to urban planning (The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 23 October 1949).

The Urban Planning Committee thus created drafted the bill for the city renewal plan in February 1950. Its priority projects were repairing roads and bridges at the city’s core and road construction along the firebreak belts. Major sites were as follows: road repair (18 arterial and important roads at the city’s core, a cumulative length of 5,060 m, and budgeted at 550 million won), firebreak belt repair and street construction (Seoul Station to Bongrae Bridge, Namsan-dong to Gahoe-dong, Namdaemun to Taepyeong-ro in front of Changdeok Palace, and Pil-gong to Gwangheemun, budgeted at 150 million won), bridges (Ogansu Bridge and several other bridges, budgeted at 80 million won), national road paving and repair (Seoul-Busan, Seoul-Uiju, and three other lines; cumulative length of 45,000 m; and budgeted at 320 million won), and gravel road repair (on the outskirts, a cumulative length of 45,000 m, and a budget of 85 million won) (The Chosun Ilbo, 24 February 1950; The Seoul Shinmun, 14 February 1950).

However, the City Planning Commission’s road improvement project was unable to progress due to the breakout of the Korean War on 25 June 1950, which also became the cause of the urban hygiene problem up until 1953 (The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 15 July 1953). From then on, even until the late 1950s, the issue of compensation for the firebreaks was not resolved and they were finally compensated and restored for the first time during the implementation of the cadastral survey project in 1959. Hence, the legacy of the Pacific War under Japanese colonial rule held a position as Seoul’s negative heritage after the Korean War until the end of the reconstruction period

5. Conclusions

In September 1945, the Japanese flag flying atop the Government-General building was lowered, the Star-Spangled Banner was hoisted, and Gyeongseong was renamed the Seoul. Efforts to wipe out the remnants of the Japanese colonial period continued across Seoul. Japanese who once worked in the Government-General during the Japanese occupation were hanged every day on the street, and Japanese buildings were burned down, day in and day out. Such scenes show a clear rupture with the preceding period.

However, city structure is another matter. Spaces and architecture are characterized strongly by their fixed attributes and cannot be altered in a brief period of time. Continuity with the past lingers potently in fixed objects because they require long-term planning. While the firebreak space issue was a big problem to Seoul city administration in terms of hygiene and urban aesthetics, it was an issue that was not able to be solved easily. While Seoul city attempted various solutions to solve this problem, it looked like the issue was being neglected, and this was due to the fact that the voices of the US military government, the city administration, and the citizens all needed to be reflected in the process of solving the issue. Due to these issues, the processing of firebreak spaces and the urban planning project could not help but be delayed due to various discussions. The handling of such firebreak empty spaces shows the varied aspects of Seoul immediately after the liberation which cannot be simply defined through decolonization and neglect.

In summary, this article has examined how urban problems caused by firebreaks, remnants of the period of Japanese occupation, were solved after liberation. It showed how the officials of Seoul came to grips with the urban problems left after colonial rule by concentrating on solving the problems associated with firebreaks. This was not limited to Seoul alone. At the same time, Pyongyang in the northern part of the Korean peninsula also faced urban problems posed by the firebreaks that had to be solved by its designers and architects, who approached the issue from a different perspective. Such a comparative study, which has not been covered in this article, would offer an opportunity to interpret the post-1945 Cold War situation on the Korean peninsula from the angle of urban history. In this context, this study may be extended to analyze the effect of the Cold War on the capitals of the two Koreas in their respective construction periods.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kim Taeyoon

Tae-yoon Kim is in the Department of Korean History at University of Seoul and is studying North Korean history and urban history. she is currently serving as a researcher at the Institute for Korean Historical Studies. The research topic and interest are in Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, and it is intended to analyze urban changes in continuity with the Japanese colonial period. Her main research is “Science and Technology Education facilities in North Korea right after the Liberation: Enlisting Teachers, and the Composition of personnel(1945∼1948)”(2018) Legal situation and character of Japanese in North Korea after liberation (1945-1948) - Based on the discriminatory treatment of North Korea(2019) etc.

Lee Kilhun

Kilhun LEE is a Assistant Professor in Cha Mirisa College of Liberal Arts of Duksung Women's University. The main concerns are, urban history, architecture history, urban regeneration and carrying out research and projects related to them.

References

- Kim, B. Y. 2009. Dominance and Space. Moonji Publishing.

- Kim, J.-G. 2010. “A Critical Assessment on the Colonial Duality of Kyungsung(Keijō).” The Journal of Seoul Studies. 38.

- Kim, J.-S. 1975. “Memoir of 30 Years: Period of Confusion under the US Military Government.” Architecture. 19.

- Kim, S. 1959. “The Municipal Administration of Seoul before and after Liberation.” The Hyangto Seoul. 6.

- Lee, J.-H. 1993. “Study of Architectural Institutes in Korea from 1945 to 1955: A Focus on the Chosun Architectural Engineering Group.” Master’s diss., Myongji University.

- Lee, Y.-H., et al. 1999. Seoul’s Architectural History. Seoul Special Metropolitan City.

- Lee, Y.-S. 2001. “A Study of Housing Shortage in Seoul in the Wake of Liberation.” The Journal of Seoul Studies. 16.

- Lim, D.-G., and J.-B. Kim. 2015. The Birth of the Metropolis Seoul. Banbi.

- The City History Compilation Committee of Seoul, 2016. 2000 years of Seoul's History vol 35, 136

- Seoul Historiography Institute. 1997. History of Seoul Administration. Seoul, Korea: Seoul Historiography Institute

- Seoul Historiography Institute. 2017. US Military Declarations regarding the Seoul Region. Seoul, Korea: Seoul Historiography Institute.

- Sohn, J.-M. 1990. Study of Urban Planning during the Period of Japanese Occupation. Seoul: Iljisa.

- Sohn, J.-M. 2005. Study of Urban Social Landscape during the Period of Japanese Occupation. Dongkwang Media.

- Seoul Historiography Institute. The City History Compilation Committee of Seoul. 1972. This is Seoul (2).

- Todd, H. 2020. Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945. Seoul, Korea: Sanbooks.

- Yeom, B.-G. 2001. “Japan’s Gyeongseong Road Projects between 1933 and 1943.” In The Review of Korean History, vol.46, 245~246.

- Yeom, B.-G. 2016. Birth of Gyeongseong (1910–1945), the Origin of Seoul: The History of Gyeongseong from the Perspective of Urban Planning. Seoul, Korea: Idea.