ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the large number of existing defense-dwellings built in the Ming and Qing dynasties with distinct regional characteristics in Fujian, and explores the relationship between major conflicts and defense-dwellings. A four-year field survey involving 459 historic villages was conducted. ArcGis was used to superimpose the high-resolution satellite map of Fujian with the borders of towns to classify defense-dwellings and establish the attribute database. By comparing the spatial types and their provincial distribution characteristics, and analyzing them with the conflicts in Fujian history, this paper presents a unique relationship between the unity and diversity of space forms and how they changed or were maintained. The results show: 1. Major military conflicts had a profound and lasting impact on the spatial pattern, residential form, and daily life of historic villages in Fujian; 2. The time and space difference of regional conflicts makes defense-dwellings present a distribution state of different types of central gathering and edge transition; 3. Persistent conflict for limited resources between clan groups made defense-dwellings remain vital, finally forming a typical “architectural atlas”. The results of this study are helpful in understanding the systematic view of morphological changes of historic villages in a highly conflicting social environment.

1. Introduction

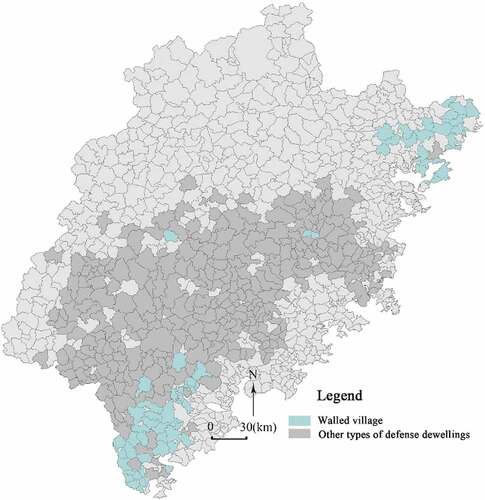

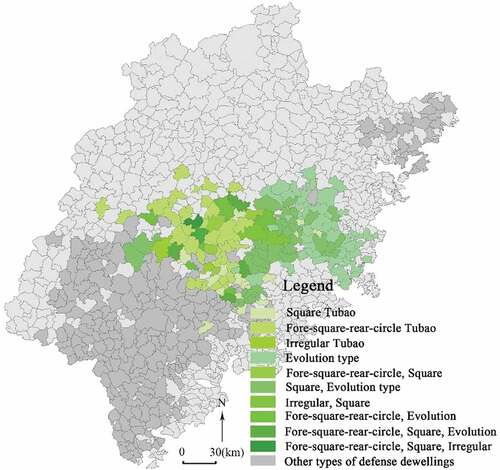

Whether ancient or modern, it can be said that “conflict” is everywhere. Conflicts between countries, tribes, classes, and individuals will arise because of limited resources. Sometimes conflicts are transmitted to the spatial layout, such as by construction of fortifications. In Germany alone, over 10,000 military castles were constructed during medieval times. They can also be found in countries such as Italy, Switzerland, Portugal, Sicily, France, Great Britain, Russia, Denmark, Poland, Syria, Turkey, Jordan, and many more.Smith Citation1988 Spain has more than 2,500 in existence.Beck, Moore, and Rodning et al. Citation2018 There is also China’s 8851.8 km long Great Wall defense system across 9 provinces, as well as military settlements along this lineCao and Zhang Citation2018. To complete these military facilities required power and financial support to mobilize of a large amount of manpower and resources, and therefore easily became the focus of attention. However, there is another type of ancient dwelling built by civilians, that were scattered in the countryside and had outstanding defensive functions in southern China. They are not often mentioned, or more accurately, are not often mentioned as buildings with military combat functions. This type of historic architecture reflects the instinctive demands for security of lower classes during turbulent periods. They did not have enough funds, technology, or manpower to build specialized fortifications, and were only able to unite villages to strengthen their homes. Among them, 46 representative TulouFootnote1 dwellings in Yongding, Nanjing, and Hua’an, Fujian Province, China, have been included as World Cultural Heritage sites. Also, in Datian County, the TubaoFootnote2 group is in the process of applying for this list. In recent years, many foreign experts and scholars have come to research them and have been surprised by their unique construction. Additionally, there are more than 10,000 vernacular architectures with similar defense functions in Fujian.Footnote3 (As shown in )These historical relics are of great significance in the study of the influence of the state’s political will, military decision-making, and ethnic cooperation on the spatial form of civilians in the late period of Chinese feudal society.

Defense architecture refers to those buildings that show distinct and strong defense purposes, have clear physical facilities, external performance of construction, and more significant security defense functions than other buildings. Since the Tang Dynasties, the Fujian people have built simple mountain fortresses and village forts. However, the defense-dwellings in this paper mainly refer to houses with highly integrated functions of defense and living, such as Tulou, Tubao, and Walled Village, which arose due to then widespread social turbulence. They all signify a dwelling meant for both living and defense purposes. Most were built in the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Previous studies on defense-dwellings (settlements) in Fujian tended to focus on the static analysis of the space in the early stage, such as characteristics of the spatial form, construction technology, and materials, etc. and were mostly presented in the form of local or case studies. Footnote4Footnote,5(Japan) 茂木計一郎[Mao Muji Yilang] Citation1996,(珍夫[Zhen Fu] Citation2007), A few also considered cultural causes, but more work is needed on this subject. Most of them were simple correspondence between society and space, which was not enough to explain the complexity and diversity of the space forms.(林嘉书, 林浩[Lin Jiashu, Lin Hao] Citation1992) Fujian’s defense-dwellings have a wide variety of types and forms. In recent years, there have been several in-depth excavations on the construction technology of Fujian Tulou, a single type(Briseghella, Colasanti, and Fenu et al. Citation2019),(Luo, Yin, and Peng et al. Citation2019),(Luo, Yang, and Ni et al. Citation2020). This is the most extensive research on Fujian’s defense-dwellings in the past 30 years, from which the most valuable and detailed fieldwork data could be found. However, realization dawned that this research direction cannot determine the dynamic relationship between society and space, cannot understand the complex interweaving state of social life and spatial entities in the process of settlement development and evolution, and cannot clearly describe the specific and real micro world behind defense-dwellings. To truly understand this kind of village fortress landscape, the historical roots in the local social unrest and changes from around 300 years ago must be found(陈春声[Chen chunsheng], 肖文评[Xiao wenping] Citation2011).

By comparing the spatial types of defense-dwellings and their provincial distribution characteristics, and analyzing them with the major conflicts in Fujian history, this paper presents the unique relationship between the unity and diversity of defense-dwellings forms, and how they changed or were maintained. Or, more simply, using the two dimensions of time and space to find the dynamic relationship between social conflicts and historic dwellings. In this way, we can further explain the internal shaping force of large-scale centralized construction of defense-dwellings (villages) in Fujian. The results of this study will help in deeply understanding the systematic view of morphological changes of historic villages in a highly conflicting social environment, revealing the influence mechanism behind static residential space.

2. Methods

(1) Research basis

First, we need to fully understand the historical environment at the time. For this, we can rely on some credible historical material. The records related to Fujian’s defense-dwellings (settlements) have been around since the Ming Dynasty, with official as well as local documents. The official records include “Records of Ming Dynasty”, “Ming History”, “Du Shi Fang Xing Ji Yao”,(顾祖禹 [Gu Zuyu] Citation2005) “Tian Xia Jun Guo Li Bing Shu”,(顾炎武[Gu Yanwu] Citation2005) “ Integration of Chinese military books”,Footnote6 “Cheng Shou Chou Lue”, “Defense Integration”, “Chou Hai Tu Bian”, “The Coastal Defense Theory”, and some officially edited “local chronicles”, such as “Pinghe County”(Qing Dynasty Citation2016) and “Funing County”. Folk historical materials were mainly local manuscripts, genealogies, and inscriptions, such as the “Kou Bian Ji”(Qing Dynasty Citation2005) and “Fujian genealogy”(陈支平[Chen Zhiping] Citation2009). These documents helped in understanding the tense situation of the China Seas, the state’s decision-making intentions, and the social living environment of local people in a multi-dimensional way; there was no major understanding bias due to different perspectives of some historical books.

(2) Research methods

Due to the lack of direct written records, the study of villages with a long history largely relies on field investigation, which is both the difficulty and charm of this study. Many well-preserved historic villages and dwellings in Fujian provide abundant information. In order to fully determine the defense characteristics of villages and dwellings, a research method combining spatial distribution and case analysis was adopted.

Firstly, using ArcGIS as the working platform, a high-resolution satellite image (2010 Landsat-7 image data) of Fujian Province was used as the base map, and the spatial boundaries of 1024 township (street) in the province were superimposed. Next, take each town as the research object, mark the factors that may be related to defensiveness based on satellite imagery, such as village layout, plane shape, group relationship, residential type, defense facilities (moat, turret, which may be seen from the satellite map), and so on. This work is not carried out blindly, but starts from the published list of 495 National Traditional Villages, 573 Provincial Traditional Villages, 23 Historical Towns and 43 Villages, the Most Beautiful Ancient Villages, Heritage Conservation Units in Fujian, the list of immovable cultural relics, and the research results of defense architectures mentioned above, we can identify the villages and dwellings with defensive performance, it is easier to identify the features on satellite images of these deterministic villages, and then to see if other villages in the township have these features. The advantage of using ArcGIS markers is to truly achieve full coverage of the research samples, rather than just selecting typical ones.

Then, a large-scale field survey was carried out to collect as many defense-dwellings samples as possible; through interviews with local residents, the defense strategies and technologies, especially the engineering technologies related to structure, materials, and details were discussed. The project had a four-year survey history. In 2015, a preliminary investigation was conducted in Zhangzhou, Longyan, Quanzhou, Sanming, Fuzhou, and other areas in Fujian in order to verify whether the defense characteristics observed by satellite images are biased. Based on this preliminary investigation, some adjustments have been made to form the current data collection system and classification standards. In 2016 and 2017, a more extensive survey was carried out on a village-by-township scale. The survey scope was extended to Ningde and Nanping in northern Fujian. Field survey data was collected from a total of 459 village samples, although not all of these villages have defense-dwellings. In this process, the database of dwellings (villages) types and spatial distribution was constantly being verified, revised, and supplemented.

Finally, the ArcGIS database showed the distribution of different types of defense-dwellings. Through the superposition analysis of the defense types and spatial distribution and the major conflicts in different periods of Fujian history, the unique relationship between the unity and diversity of defense-dwellings forms and how they changed or were maintained is presented. Additionally, it made the relationship more vivid in the form of case analyses.

3. The construction of defense systems in the evolution of conflict

The 14th-18th century is a critical period that may have influenced the world pattern today. It can be referred to as “the era of expansion”. Oriental spices, jewelry, and silk were first transported to the eastern Mediterranean coast by Persians, Arabs, and Eastern Romans, and were then transported to other parts of Europe; Portugal’s Bartolomeu Dias led the fleet to the Cape of Good Hope at the southwestern tip of Africa; Columbus of Italy, with the support of Spain, opened a new route to America. These ocean trade and geographical explorations were the early stages of globalization. If we look at China, we find that these explorations triggered a series of conflicts and riots.

3.1. The establishment of official coastal defense under foreign conflicts

In the middle and late 14th century, China’s Ming Dynasty had just been established. At this time, Japan was in conflict between the North and South, the lords in the southwest often sent warriors to plunder the coastal areas of China, from North Korea to Fujian and Guangdong. After the defeat of Japan’s Southern Dynasty, exiled soldiers, armed men, unemployed, and merchants escaped to the sea. Facing the sea, Fujian had natural convenient maritime transportation, which was also beneficial for Japanese pirates. There are many related records: “plundered the city, injured the townspeople “(明太祖实录[Taizu Records of Ming Dynasty] Citation1962a); “attacked Tongshan Fortress, and plundered Moon Port and Yunxiao town. There were 27 major crimes committed in Zhangzhou, more than 1,000 homes were burned, killing thousands of soldiers and civilians.”(姜天裁[Jiang Tianzai] Citation2019) According to the statistics of Records of Ming Dynasty, there were roughly 289 incidents of Japanese invasion.(程龙吟[Cheng Longyin] Citation2014)

On the other hand, with the discovery of new geographical routes, maritime trade in the southeastern region of China had become unusually active, the Ming government was wary of these unfamiliar commercial colonists. After the Portuguese attempt to trade with Guangdong was blocked they turned to the Zhejiang, resulting in turmoil in this area; Dutch harassment to the southeast coastal area after occupying Taiwan made the Ming government more concerned about the situation in the China Sea.

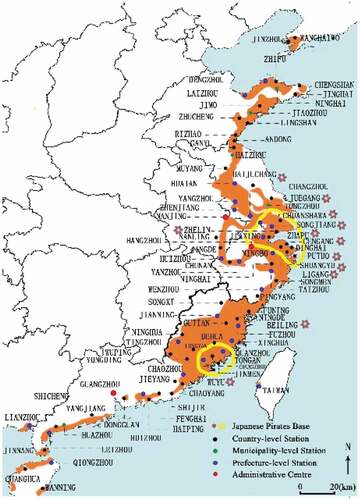

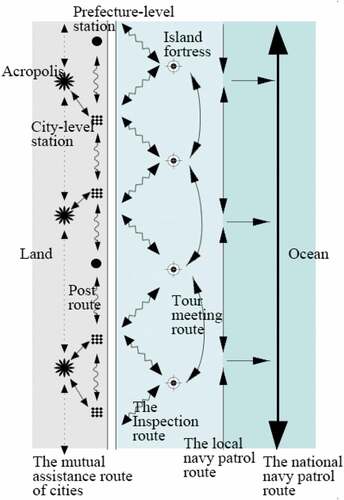

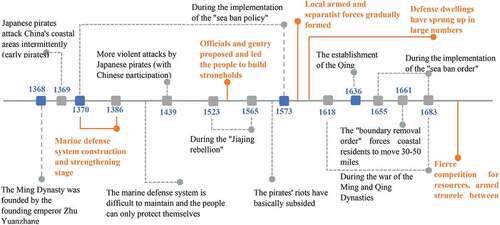

In order to combat Japanese pirates and compete with foreign merchants, Zhu Yuanzhang, the Ming Dynasty emperor, successively decreed “Forbid coastal dwellers going to sea without permission”, “Forbid coastal dwellers communicating with foreigners”, “No fishing around the sea”,(明太祖实录 [Taizu Records of Ming] Citation1962) and other prohibitions, so as to block contact between the inland and sea to ensure security. About one-third of China’s national boundaries face the sea, and the emperor was particularly worried about marine security. Japanese pirates plundered China’s coastal areas in a wide range and to a serious degree (). The Ming government, which lacked experience in ocean warfare, had to take action, like sending officials to the coast for defense deployment and building military cities, Island fortresses, and watchtowers, as well as setting up guards at all transport hubs, important towns, and small Islands. Seven defense regions were formed, they were Liaodong – North Zhili – Shandong – South Zhili – Zhejiang – Fujian – Guangdong, of which Fujian coastal defense was divided into three zones and five Islands. () Fujian was an area frequently targeted by pirates and a key area for coastal defense deployment. According to incomplete statistics, in the Ming Dynasty, there were 66 citadels, 107 military cities, 58 Island strongholds, 23 infantry barracks, 543 fortresses for patrol and reconnaissance, and 1382 stations for lookout, alarm, and military information transmission.(中国人民解放军工程兵学院研究室[Research Office of Engineering Academy of PLA] Citation1985) ()

3.2. Decline of official defenses and rise of folk defenses

The implementation of the coastal defense system did play a major role in combating pirates and foreign merchants; however, the high cost was difficult to sustain, and its disadvantages gradually became apparent around the middle of the Ming Dynasty. Many soldiers fled and military power declined. In 1547, when Zhu Wan, a minister of the Ming, oversaw the coastal affairs of Fujian, he carried out a general survey and found that coastal defense failure was widespread.(王日根[Wang Rigen] Citation2006) On the other hand, “Ban of Maritime Trade” implemented together with the Coastal Defense System curbed the normal development of Fujian’s maritime trade. Merchants and people who lived by the sea took risks to trade,(明太祖实录[Taizu Records of Ming Dynasty] Citation1962b) leading to underground trade, commercial disputes could not be settled, and brought about armed conflict. This caused more chaos from pirates, becoming the historically well-known “Jiajing rebellion event “[嘉靖倭乱],” referring to a series of brutal slaughters during the Jiajing period (1522–1566). Notably, in 1555, 53 pirates (composed of Chinese and Japanese) ran rampant along the coast for more than 80 days. When they came to shore, they attacked towns and fought against officers and soldiers, causing 4000 to 5000 casualties, including several senior officials.(姜天裁[Jiang Tianzai] Citation2019) Some natives colluded with the Japanese pirates, causing more extensive banditry.(戴志坚[Dai Zhijian] Citation1999)Footnote7 The boundaries between officials, civilians, soldiers, and bandits had become very blurred, and it had become difficult for the government to find a specific target to blame. In such an environment, merchants began to form large-scale commercial groups, constantly competing with governments over commercial interests.Footnote8

With the official armament system being unable to effectively play a defensive role, many officials began to realize that these problems could only be dealt with by making use of villagers. They proposed to “train villagers like soldiers” for self-protection, making rural soldiers an important part of the military system. It was also a critical opportunity for the growth of local rural forces. In terms of personal safety, “building forts” and “training villagers” came together. For example, the scholar-official Huo Tao proposed that the local people in Fujian and Guangdong should be organized to build forts for self-defense.(Ming) 张萱[Zhang Xuan] Citation2018 In addition, Lin Xichun, a scholar-official in Zhangzhou Prefecture, repeatedly put forward the idea that people should build fortresses to defend themselves by armed force, recommending that the court allow people to do so.(Ming Dynasty) 林偕春[Lin Xichun] Citation1999 These proposals were approved and implemented, initially with construction manuals.Footnote9 () The government also encouraged small villages to merge into larger ones, establish strongholds, and defend in groups.塘湖刘公御倭保障碑记, edited by陈历明 [Chen Liming]: 潮汕文物志(上) Citation1985 This policy caused major changes in the settlement pattern of Fujian since the Jiajing Dynasty. The scattered small villages had been reduced, and military fortresses appeared in many villages. With the prevalence of building fortresses, civil forces began to step into the official defense system and took on the responsibility of protecting ethnic groups. Sometimes, if they could not get official approval, they defended themselves even against the wishes of the government.

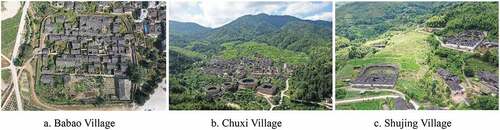

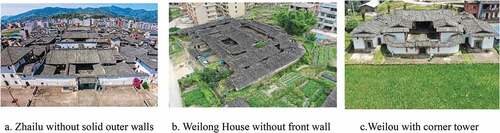

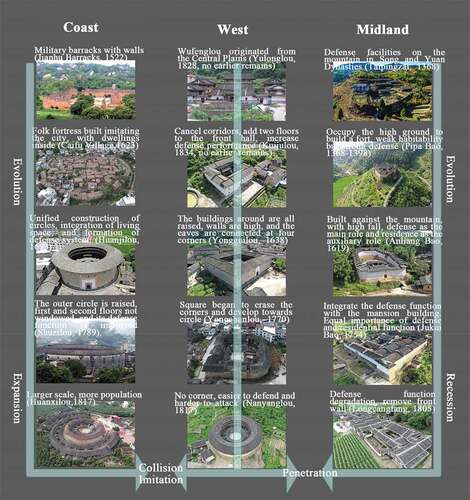

Although many defense settlements were built in Fujian during this period, they were mostly in the form of Enclosed Villages and Walled Villages, imitating the practice of military cities. The residences and defense functions were relatively independent, the exterior was protected by ramparts and moats, and the interior was residential buildings. Gun holes, turrets, and gates like those found on exterior walls in the military cities could also be found here. Generally, they were built by an entire family or village or several families and villages with strong economic capacity, the scale was relatively large. The Walled Villages in the early days were more like temporary defense-dwellings where villagers could hide and defend in case of attack. Later, after hundreds of years of development, they gradually became encircled villages with a combination of residence and defense functions(As shown in ).

Table 1. Types of defense settlements.

3.3. Diversified development of defense-dwellings in local continuous conflicts

Piracy in the Ming Dynasty can be roughly divided into two periods: in the early stage, about 1368–1424, pirates were active in the coastal areas of Liaodong, Shandong, and Zhejiang. They were composed of feudal lords, warriors, merchants, and Japanese ronin, the main strategy was small group harassment. In the later period, about 1523–1565, pirates concentrated their strength to invade the southeast coastal areas mainly in Fujian. The groups were quite complicated. There were Chinese Pirates such as Wang Zhi and Xu Hai who fled to Japan and colluded with Japanese pirates. There were also Chinese local smugglers, pirates, bankrupt farmers, and coastal aristocrats. The maintenance of the “Ban of Maritime Trade” policy and the suppression of coastal riots in the Ming Dynasty greatly depleted the nations strength, so it had difficulty protecting itself in the late period of the dynasty.

In 1636, the Qing Dynasty was established. In order to annihilate Zheng Chenggong’s troops who had failed in the regime war and retreated to an Island of Taiwan, the new court enacted a more stringent “Ban of Maritime Trade” order so as to stabilize the regime, prohibiting private maritime trade to ensure the supply of all goods was cut off. In 1661, When this order failed to achieve the expected result, the court implemented another “Coastal Evacuation order” that forced coastal residents to move inland 30–50 miles and drove out the people many times using high-pressure means, burning houses, crops, and other living supplies. As a result, thousands of families were destroyed and displaced along the coast, and many refugees were forced to plunder the countryside to survive.(赵尔巽[Zhao Er’xun] Citation1977) It can be said that this policy caused Fujian to suffer a devastating blow from the coast to the inland.

During this fierce social unrest, government control was limited, and people had to build fortresses to defend themselves. In the short period of a hundred years, highly developed defense-dwellings such as Tulou and Tubao were built in Fujian(As shown in ). Their defense performance was constantly upgraded in the process of resisting invasion with a growing variety of residence-defense integrated buildings. During this time, defense-dwellings tended to be mature, mainly large-scale single buildings. Shunyu building, the largest round Tukou in Fujian, has a diameter of 86 m and a total of 368 rooms with four floors. At the peak of conflict, it could accommodate nearly 1000 people simultaneously.

Table 2. Types of Tulou.

Table 3. Types of Tubao.

From the aspect of morphology, some Tulou and Tubao are easily confused, but their building materials, construction methods, and spatial organization are quite different. The outer walls of Tulou are not only used for enclosure, but also for bearing loads. The internal room and external wall are not independent but are erected on the wall side by side to build a circle of rooms with a public patio or ancestral hall in the middle. The Tubaois outside a well-designed group of buildings, enclosing a defensive wall. There are defense facilities on the wall, including turrets, raceways, and shooting holes. The wall itself does not bear loads. Even if the outer wall collapses, it will not affect the houses inside.

3.4. Defense performance improvement in conflict

The construction of civil defense-dwellings largely refers to the military defensive system. The main body of defense in Fujian was to build heavy rammed earth walls, some key positions would also be defense points. The defense of Walled Villages was basically similar to the military defense system. Tulou and Tubao were mainly defended by sentry walks, bucket windows, gun holes, turrets, and lookout towers. Few standing Tulou had turrets and a sentry walk inside the wall, but most Tubao did(As shown in ).

Table 4. Types of defense facilities.

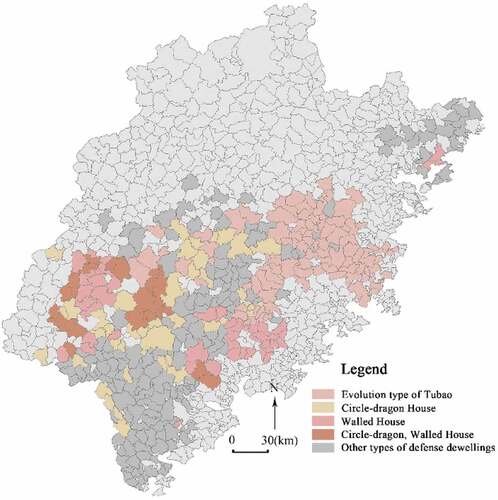

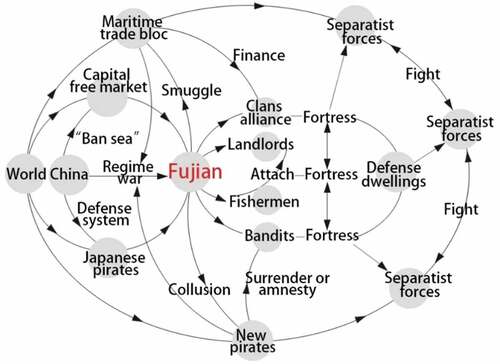

As shown above, from early Ming Dynasty to late Qing Dynasty, Fujian’s defense system experienced a transformation from state-led heavy military defense to clan-led folk defense(As shown in ). The decay of the Coast Defense Army, which was the core of national military power, directly promoted the rise of civil military power. “Village soldiers”, “fishing soldiers”, or so-called “recruited pirates”, were the bulk of local military forces. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties the political situation was unstable and the boundary between “ Civilians” and “ Bandits “ was more complicated.(陈春声[Chen Chunsheng] Citation2001) Everyone, including former dynasty forces occupying Islands, scattered military powers, and the army of the court, were fighting for their interests using force. In a word, this situation of continuous conflicts since the beginning of the Ming Dynasty shows that Fujian was undergoing a serious transformation of economic and social organization structure. These conflicts that occurred continuously on the time axis are not continuous in the vast geographical space of Fujian. Although the morphology of villages and dwellings has undergone major changes as a result, these changes were not synchronized, but have obvious type differentiation.

4. The spatial distribution characteristics and evolution driving mechanism of defense-dwellings

4.1. The spatial distribution characteristics

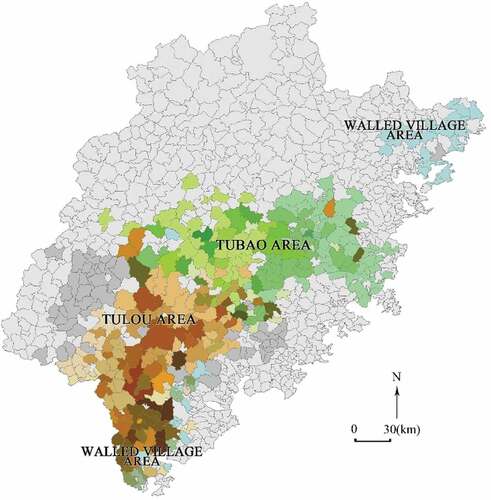

Enclosed Villages and Walled Villages were mainly distributed in Zhaoan County, which borders Guangdong Province, and several counties in the northeast of Ningde, which borders Zhejiang Province(As shown in ). They were the main point of entry to Fujian for outsiders. There were many outlaws committing crimes here, such as Xu Chaoguang, Wu Ping, Lin Daoqian, and Zeng Yiben. Because of the vague jurisdictional boundary, officials passed the buck and conspired to form clans in these places. Like the “Wan-surname group” in Zhaoan, some participants even changed their surnames to “Wan” to form an alliance.(Jidong Citation1996) Because of the early years of construction, only a few Enclosed Villages and Walled Villages have survived.

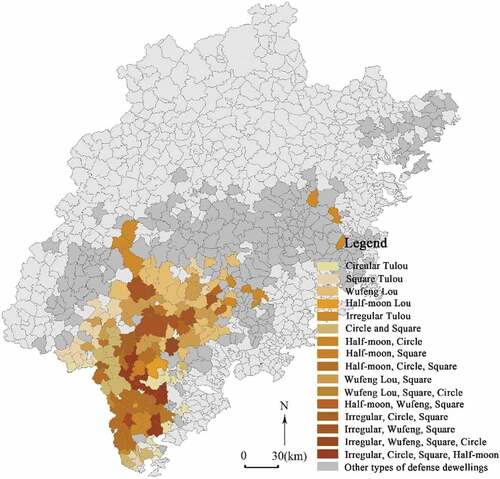

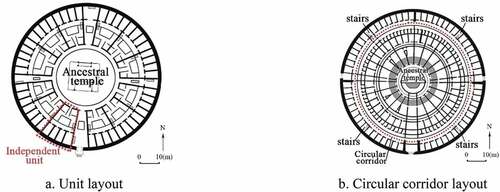

Fujian Tulou can be divided into Hakka Tulou (mainly in Longyan area) and Minnan Tulou (mainly in Zhangzhou and Quanzhou). They are similar in appearance and are difficult to distinguished by most people, but their internal structure is very different. Most Hakka Tulou adopt the inner corridor layout, that is, the space is organized by circular corridors and multiple public stairs. The Minnan Tulou is more of a unit layout and each unit runs through all floors by its own stairs, units are independent and not connected with each other. () These two types of Tulou represent the settlement characteristics of the two major ethnic groups in Fujian, and truly reflect the construction characteristics of Tulou at different construction times. The Tulou in South Fujian can be traced back to 1558, that is, during the “Jiajing rebellion”. In addition, there are many existing Tulou that were built in the Ming Dynasty, while the earliest Hakka Tulou was recorded in 1628. Most of the Hakka Tulou were built after the Qing Dynasty, so Zhangzhou rather than Longyan was the first area where Tulou were built(谢重光[Xie Chongguang] Citation2007). This is because, during the reign of Jiajing, Japanese pirates attacked coastal China, with Zhangzhou being even more severely attacked. The purpose of building Tulou was to resist invaders, so Tulou appeared first along the coast. Generally, Fujian Tulou were mainly distributed in the west and south which was the border area of the three provinces of Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong(As shown in ). It was an area where several ethnic groups mixed. Conflicts over resources never ceased. The policy of “Ban of Maritime Trade,” which had been implemented for hundreds of years, suppressed the development of coastal trade, which was the livelihood of many. The “Coastal Evacuation order” intensified the competition and conflict from the coast to the inland. The turmoil which spanned two dynasties had not subsided, so Tulou, as a kind of civil military fortress, played an important role.

The political power struggle in the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties led to social turbulence and constant uprisings occurred in central Fujian. The vulnerable peasants who had difficulty surviving were desperate to carry out armed resistance. The Deng Maoqi Uprising in Shaxian County of Fujian during the orthodox period was a typical event that alarmed several provinces in Southeast China and affected the whole country. Other peasants who lost their livelihood became bandits, robbing houses and destroying tools, even founding villages that made a living through robbery. Some wanted pirates would also flee to the inland mountainous areas. Generally speaking, whether soldiers, civilians, bandits, or wealthy people, there was a realistic need to build defense dwellings. Various forms of Tubao were distributed in all parts of Fujian, especially in central Fujian(As shown in ). They were also distributed in Longyan, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, and other areas, but the number of existing Tubao is not large, and their shape is closer to Weilongwu and Wufeng buildings.(曹春平[Cao Chunping], 福建的土堡 [Tubao in Fujian] Citation2002) Compared with Tulou, the residential and defensive functions of the Tubao are relatively independent. The thick outer wall is only equipped with defense facilities, there is no room for residence. The courtyard building inside the wall is limited, the population it can accommodate is not as large as Tulou. As a result, when turmoil subsided, the Tubao, as a kind of building which pioritized defense, gradually evolved into more rich forms. There were not many and most were residential, but some defense facilities could also be seen

.In the transition zone where defense-dwellings were concentrated, there were also a large number of quasi defense-dwellings, such as Weilong House, Weilou, Zhailu, etc. () Although these were mainly residential, they were also large-scale single buildings, with walls, turrets, bullet holes, and other defense facilities. In general, the defense function is weaker than real defense-dwellings and was used more to gather people for defense. From , we can see that different types of defense-dwellings have significant characteristics of gathering in the center and transition at the edges, which makes their form present a unique relationship between the unity and diversity This is highly consistent with the major conflicts recorded in historical materials. It is worth mentioning that the “Coastal Evacuation order” caused serious damage to the residential buildings within dozens of kilometers of the coast; the remaining defense-dwellings were very scarce, which is the main reason why there were not many near the coastline even though they were places with high incidence of conflict.

4.2. Driving mechanism of defense-dwellings space evolution

Throughout the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the national policy was “forbidding”, the fundamental starting point of rulers was to cut off internal and external connections to ensure territorial security at any cost and stabilize the situation at sea. In fact, the activity of coastal trade was the beginning of a capitalist free market, which was contrary to the power rule of the dynasty, reflecting the conflict between the new demands of the people under the global tide and the official desire to maintain an independent feudal society. In the era of great navigation, the world’s maritime trade was booming. China’s coast was an important part of it, containing great wealth and business opportunities. The flourishing maritime trade could not be stopped, it could only be forced to develop in abnormal ways. A series of policies with “ban sea” as the main focus suppressed the normal development of Fujian’s social economy. The natives and pirates colluded to form a maritime separatist regime. Large and small maritime groups continued to develop in cooperation against the imperial court, in competition with each other for resources, and in dependence of interests. In addition, the state paid more attention to the management of coastal defense, but ignored the overall disadvantages of the society, which caused frequent incidents such as desertion of soldiers, inland uprisings, burglaries, and so on. In the face of large-scale riots, the country could only adopt the initiative of local officials to vigorously implement the policy of “building civil forts and training civilian soldiers” to ensure local security, which provided institutional support for the development of defense settlements in Fujian.The demand of villagers for security defense grew rapidly, which contributed to the militarization of grass-roots society.(郑振满[Zheng Zhenman] Citation2009) It could be said that “Japanese Pirates” and “Ban of Maritime Trade” promoted the construction of united families. Many families sought to build fortresses for self-defense. In the initial defense, when nearby villages were attacked, villagers took refuge in the fort. The villagers gradually formed a strong defense system, which was different from the loose individuals under the official command. It was this sense of identity based on consanguinity and geography that made the more closely connected local clans no longer obey the government. In the process of leading the resistance, the local forces mainly composed of local clans continuously accumulated their strength. The local gentry began to control local security affairs, and the corresponding clan system became more and more extensive. It was normal to build houses with clan groups as a unit. In the process of resistance, local forces mainly based on clans constantly accumulated strength, squires began to control local security affairs, and the corresponding clan system gradually improved. Small families used to peacetime could not adapt to the sudden turbulent social environment. Instead, it was normal to build big houses with clan groups. More and more large-scale defense single houses appeared due to the continuous improvement of defense performance. (see )

In the middle and late Qing Dynasty, although invasion was eliminated, the influence of the village clan spread to almost every corner of Fujian. Their participation in local security was no longer by order of the government. Village clans often fought each other because of resource allocation and honor.(Freedman Citation1958) When disputes could not be reconciled, they resorted to force.For a detailed discussion of clan fighting, see Maurice Freedman, Citation1958) Local officials often stood by and let the patriarchs solve problems on their own. At this time, defense-dwellings were a product of rural separatism.

Under the construction of civil defense spaces, the differences of social forms, economic basis, topography, and other factors in different regions of Fujian formed differences of defense residential forms and types. However, the differences were weakened in the upgrading of the defense function, and the defense function tended to be integrated with early residential forms. From , we can see the clear evolution context and the relationship among the coastal, western, and central defense residential areas in Fujian.

5. Conclusion and discussion

From the above analysis, we can draw several conclusions:

1. Major military conflicts have a profound and lasting impact on the spatial pattern, residential morphology, and social daily life of historic villages in Fujian. The implementation of policies such as building fortresses and small villages merging into large ones provided institutional support for the early construction of defense villages. Once this construction system was formed, it was maintained by group forces and played a long-term role. Even after its objective basis disappeared, the role of institutional authority still persisted for a long time.

2. The time and space differences of regional conflicts made the defense-dwellings present a distribution state of different types of central gathering and edge transition, and their spatial organization was different due to the different habits of ethnic groups. The non-synchronization of time and space made the form of defense-dwellings present a unique relationship between the unity and diversity of forms.

3. The conflict of clan groups’ competition for limited resources made the defense-dwellings vigorous and lasting until modern times. As the government’s control over the countryside declined, clan groups, local heroes, illegal businessmen, bandits, and others arrived. It became a social norm to fight for everything using violence. Buildings with both residential and defensive functions in different areas eventually formed their conventional model “Architectural atlas” after a long history of development, becoming a typical form of local villages and dwellings.

In the long history of development, the construction concept and technology of Fujian defense-dwellings gradually formed. Through continuous trial and improvement, these houses skillfully integrated defense and residential functions. From location selection to village form, from single scale to architectural layout, from defense facilities to detailed structures, a complete defense system was formed. Their technical part was easy to understand and improve, but the humanistic characteristics behind this system are not easily noticed. The historical origin of building defense-dwellings, which lasted for hundreds of years, was obviously related to the rapidly changing social environment after the Ming Dynasty. Without understanding the social organization network at that time, it is difficult to understand the depth and breadth of this kind of special architectural space and its flexibility and strength. When discussing the changes of such buildings, the emphasis tends to be on the static factors, such as technology, resources, the role of geographical environment, and so on. Or the preference is to analyze it as a construction method with some “ideal mode”. Both Chinese traditional geomantic culture and Western Renaissance formalism are seeking a reference for the occurrence of historic architecture as the ideal prototype of architectural creation. However, this does not help people establish a rational foundation for architectural cognition. On the contrary, the combination of fieldwork and literature analysis, diachronic research and structural analysis, and national system and grass-roots social studies can go back historically as far as possible emotionally, mentally, and rationally. The reconstruction of the space diachronic process and scene can often give us a deeper understanding of how these exquisite buildings used to be created over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Qiaohua Qin

Qiaohua Qin (1990), a doctoral student, mainly studies the history and spatial form of Chinese traditional villages.

Dawei Xiao

Xiao Dawei (1956), Professor, doctoral supervisor, director of State Key Laboratory of subtropical Architectural Science.

Junwei Ma

Junwei Ma (1995), a master's student, studies the protection and development of vernacular architecture.

Jin Tao

Jin Tao (1981), associate professor, master Supervisor.

Notes

1 It is a kind of multi-storey giant residential building distributed in the West and south of Fujian Province, which adapts to the large family settlement, has prominent defense function, and uses rammed earth wall and timber beam column to bear the load together. See黄汉民[Huang Hanmin],福建土楼[Tulou in Fujian], Beijing, SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2017,112.

2 It is kind of large-scale single ancient residential building composed of a courtyard style dwelling surrounded by the extremely thick earth-rock wall. See戴志坚[Dai Zhijian],陈琦[Chen Qi],福建土堡[Tubao in Fujian], Beijing, China Architecture& Building Press,2014,6.

3 Huang Hanmin, an expert of Tulou research, found a total of 3733 Tulou with recognizable characteristics in Fujian Province, including 17 counties (districts) in Longyan, Zhangzhou and Quanzhou. See黄汉民[Huang Hanmin], 福建土楼[Tulou in Fujian], Beijing, Sanlian bookstore, 2017,35. However, according to a statistics of Nanjing County Government, there are more than 1300 standing Tulou in Nanjing alone. See 南靖县人民政府 编[Nanjing County Government], 福建土楼故里南靖 [Tulou in Fujian, Hometown in Nanjing], (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House,2018:3). Based on field investigation and high-definition satellite images, our team also has reason to believe that Huang Hanmin underestimated the number of Tulou in Fujian. We estimate that there are more than 10,000 Tulou buildings of different sizes in Fujian. In addition, there are about 10,000 Tulou buildings built in history, but there are only more than 500 left. See戴志坚[Dai Zhijian],陈琦[Chen Qi],福建土堡[Tubao in Fujian], Beijing, China Architecture& Building Press,2014,8. Therefore, we conservatively estimate that there are more than 10,000 defense-dwellings in Fujian.

4 In the study of defense-dwellings (settlements) in Fujian, Tulou started earlier. For example, Huang Hanmin has investigated Tulou in Fujian area for many times, and published many related books and articles. See 黄汉民 [Huang Hanmin], 客家土楼民居[Hakka Tulou dwellings], Fuzhou, Fujian Education Press, 1995. Huang Hanmin, 福建土楼中国传统民居的瑰宝图集 [Fujian Tulou, treasure Atlas of Chinese traditional houses] Beijing, Sanlian bookstore, 2003. 黄汉民, 陈立慕 [Huang Hanmin, Chen Limu], Fujian Tulou Architecture [福建土楼建筑], Fuzhou, Fujian’s Science and Technology Press, 2012. Huang Hanmin, 福建土楼[Tulou in Fujian], Fuzhou, Straits Literature and Art Press, 2013.

5 In 1985, Yang Guozhen and Chen Zhiping, the historians of Xiamen University, made an in-depth field investigation. Based on the remains of Tubao in Ming and Qing Dynasties and the folk literature materials, they analyzed the Tubao. See 杨国桢, 陈支平 [Yang Guozhen, Chen Zhiping], 明清时代福建的土堡[Tubao in Fujian in Ming and Qing], Research on the social and economic history of China, 1985 (02).

6 Integration of Chinese military books is a collection of 119 ancient military books in three thousand years, with a total of 771 volumes.

7 At that time, the famous bandits, such as Ruan Qibao, Li Dayong, Xie He, Wang Qingxi, Yan shanlao, Xu Xichi, Zhang Wei, Zhang Lian, Xiao Xuefeng, Xu Dongzhou and Wu Pingping, were all from the south coast of Fujian and the east of Guangdong. We can see from: (Ming) 谢肇淛[Xie Zhaoyu], 地部 [Di Bu], from Wu Za Zu Shang [五杂爼上], central bookstore, 1935 (4), 145. (Ming) 胡宗宪[Hu Zongxian], 筹海图编 [Chou Hai Tu Bian], Taipei, photocopy of Taipei Commercial Press, 1986(1), 280.

8 For example, when the sea merchants group headed by Wang Zhi failed to ask government to permit sea trade with Japan, he teamed up with Xu Hai and other people to introduce the Japanese pirates to plunder the rich land in the southeast coast, making it in a long-term war. 采九德[Caijiude], 倭变纪略[Kou Bian Ji Lue], Volume 4.

9 The contents of “alliance”, “Castle learning”, “Castle Building”, “Castle power”, “Castle system”, “castle guard” and “Wang Minghe’s Castle style” recorded in the 城守筹略[cheng shou chou lue] compiled in the Ming Dynasty teach the people how to select the site, the shape, the defense, the division of labor, and how to train the local soldiers.

References

- (Japan) 茂木計一郎[Mao Muji Yilang]. 1996. 中国民居研究[A study of Chinese folk houses]. Taipei: Nantian bookstore.

- (Ming Dynasty) 林偕春[Lin Xichun], “云山居士集 [Yunshan Jushu Ji]”, vol 1, p. 11, (1999 Edition of Yunxiao County Cultural Relics Protection Association and Yunshan Academy Lin Taishi Tomb Working Committee).

- (Ming) 张萱[Zhang Xuan]. 2018. 西园闻见录[Xi Yuan Wen Jian Lu], 3129. Vol. 98. printed by Harvard Yanjing Xueshe.

- Beck R A, Moore D G, Rodning C B et al. 2018. “A Road to Zacatecas: Fort San Juan and the Defenses of Spanish La Florida.” American Antiquity 83 (4): 577–597. DOI:10.1017/aaq.2018.49.

- Briseghella B, Colasanti V, Fenu L, et al. 2019. “Seismic Analysis by Macroelements of Fujian Hakka Tulous, Chinese Circular Earth Constructions Listed in the UNESCO World Heritage List”. International Journal of Architectural Heritage 8(10): 1–16.

- Cao Y, Zhang Y. 2018. “The Fractal Structure of the Ming Great Wall Military Defense System: A Revised Horizon over the Relationship between the Great Wall and the Military Defense Settlements.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 33.

- Freedman, M. 1958. Lineage Organization in Southeastern China. London: Athlone Press.

- Jidong, X. 1996. “诏安天地会发源地 [Birthplace of Zhao’an Tiandi society].” In Zhao’an Literature And History Materials [诏安文史资料]. Vol. 16, 48. compiled by the Research Committee of literature and history materials of Zhao’an County Committee.

- Luo Y, Yin B, Peng X, et al. 2019. “Wind-Rain Erosion of Fujian Tulou Hakka Earth Buildings”. Sustainable Cities and Society 50: 101666. DOI: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101666.

- Luo Y, Yin B, Peng X, et al. 2020. “Degradation of Rammed Earth under Wind-driven Rain: The Case of Fujian Tulou, China”. Construction and Building Materials 261: 119989. DOI: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119989.

- Qing Dynasty. 2005. 台湾文献会刊 [Taiwan Literature Journal (Volume 14, Volume 2)]. Beijing: Kyushu publishing house.

- Qing Dynasty. 2016. 平和县志(康熙版影印) [Pinghe county annals (photocopy of Kangxi Edition)]. Fuzhou, Fujian people’s Publishing House.

- Smith, B. 1988. Castles, Library Of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data, 17.

- 中国人民解放军工程兵学院研究室[Research Office of Engineering Academy of PLA]. 1985. 中国古代筑城述要[A summary of ancient Chinese fortification]. Beijing: China Construction Industry Press.

- 塘湖刘公御倭保障碑记, edited by陈历明 [Chen Liming]: 潮汕文物志(上). 1985. 汕头市文物管理委员会办公室[Shantou Cultural Relics Administration Committee Office], 335. Vol. I.

- 姜天裁[Jiang Tianzai]. 2019. “明代福建海疆防卫述略(上) [Overview of Fujian coastal defense in Ming].” Fujian Historical Records 1: 1–5.

- 戴志坚[Dai Zhijian]. 1999. “福建古堡民居略识以永安”安贞堡”为例[A brief introduction to Fujian ancient fort dwellings, taking Anzhen Fort as an example].” Huazhong Architecture 4. 15-16.

- 明太祖实录 [Taizu Records of Ming], Vol 70, 139, 159, Taiwan, School of History and Language, Taipei Academy of Central Studies, 1962.

- 明太祖实录[Taizu Records of Ming Dynasty], Vol 52, Taiwan, Taipei Academy of Central Studies, School of History and Language, 1962a. Taizu Records of Ming Dynasty.

- 明太祖实录[Taizu Records of Ming Dynasty], Taiwan, School of History and Language, Taipei Academy of Central Studies, 1962b(205).

- 曹春平[Cao Chunping], 福建的土堡 [Tubao in Fujian]. 2002. Huazhong Architecture, 68–71. Vol. 3.

- 林嘉书, 林浩[Lin Jiashu, Lin Hao]. 1992. 客家土楼与客家文化[Hakka Tulou and Hakka culture]. Taipei: Boyuan Publishing Co., .

- 王日根[Wang Rigen]. 2006. 明清海疆政策与中国社会发展 [The policy of maritime areas in Ming and Qing Dynasties and China’s social development], 92–133. Fuzhou: Fujian people’s publishing house.

- 珍夫[Zhen Fu]. 2007. 南靖土楼探寻[Exploring the Tulou in Nanjing]. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press.

- 程龙吟[Cheng Longyin]. 2014. “明朝晋江的筑城防倭[Building cities and preventing Japanese pirates in Jinjiang of Ming Dynasty].” 历史档案[Historical archives] 2014(4): 76–80.

- 谢重光[Xie Chongguang]. 2007. “闽粤土楼的起源和发展[The origin and development of Tulou in Fujian and Guangdong].” Chinese Historical Relics 2007(1): 76–82.

- 赵尔巽[Zhao Er’xun]. 1977. 清史稿[Draft of Qing History]. Shanghai: Zhong Hua Book Company.

- 郑振满[Zheng Zhenman]. 2009. 乡族与国家—多元视野中的闽台传统社会[The village and the country: The traditional society of Fujian and Taiwan in a multi perspective]. Beijing: Sanlian bookstore.

- 陈支平[Chen Zhiping]. 2009. 福建族谱[Fujian genealogy]. Fuzhou: Fujian people’s publishing house.

- 陈春声[Chen chunsheng], 肖文评[Xiao wenping]. 2011. “明清之际韩江流域地方动乱之历史影响[Settlement form and social transformation: The historical influence of local unrest in Hanjiang River Basin during the Ming and Qing].” Journal of Historical Science 2011(2): 55–68.

- 陈春声[Chen Chunsheng]. 2001. “从“倭乱”到“迁海”——明末清初潮州地方动乱与乡村社会变迁[From “Japanese piratesrebellion” to “moving to the sea” – Local unrest and rural social changes in Chaozhou at the end of Ming and early Qing]”. 明清论丛[Treatises of Ming and Qing Dynasty]. (Vol. 2, 96). Beijing: Forbidden City Press.

- 顾炎武[Gu Yanwu]. 2005. “A Historical and Geographical Work, Recording the Social, Political and Economic Conditions of Various Regions in the Ming Dynasty. (Qing Dynasty).” In 天下郡国利病书[Tian Xia Jun Guo Li Bing Shu]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Works Press. 89-90.

- 顾祖禹 [Gu Zuyu]. 2005. “Gu Zuyu Wrote It in the Early Qing Dynasty, Which Has a Strong Feature of Historical Military Geography. See (Qing Dynasty).” In 中国古代地理总志丛刊:读史方舆纪要[A series of Chinese ancient geography: Du Shi Fang Yu Xing Yao (12 volumes in a set)]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. 338-339.