ABSTRACT

In this study, we aimed to identify the planning conditions necessary for child-rearing-friendly housing by investigating an old municipal apartment in Kyoto City that was remodeled for achild-rearing household and determine the residents’ space utilization. The results were as follows: 1) Securing expandable space is highly beneficial for households with young children, especially when they utilize mostly the extended space for daily living. And asouth-facing arrangement is important to ensure comfort. 2) In plans for child-rearing households, it is necessary to secure enough storage space in consideration of the increase in the amount of necessary storage due to the children’s growth. 3) Restricted arrangement of household spaces to reduce movement is effective in supporting childcare. 4) It is desirable to design aspace to support residents so that they can utilize and modify it according to their needs, which change over time according to the age of their children.

1. Introduction

The average total fertility rate of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was 1.61 as of 2019, continuously decreasing compared to 2.79 in 1970.Footnote1 As such, the problem of declining total fertility rates worldwide is significant. Various efforts are being made globally to respond to this problem, and one of these efforts is to support the housing stability of child-rearing households.

Figure 1. Before and after the remodeling of child-rearing-friendly home (Source: Leaflet for recruiting tenants of municipal housing for child-rearing households).

In Japan, the disappearance of regional towns and villages due to alow total fertility rate below the OECD average and rapid population decline has become amajor social and economic problem.Footnote2 In response, the Japanese government included newlyweds and child-rearing households in the “People Requiring Special Assistance in Securing Housing,” and Japan’s new basic programs for housing revised in March2016 sets priority to the goal of “realizing alife in which young people, child-rearing households, and the elderly can live with no worries.”Footnote3 Local governments across the country are providing housing specifically targeted toward child-rearing households and are offering various housing support measures to secure housing stability for newlyweds and child-rearing households in line with the goals set in Japan’s new basic programs for housing.Footnote4

Recently, an increasing number of local governments are remodeling vacant public rental housing into child-rearing-friendly housingFootnote5 units. This has drawn attention since it can solve the problem of supplying suitable housing for child-rearing households while simultaneously resolving the issue of increasing vacancies in old public rental homes. In addition, it is easier to supply units based on existing homes than building new homes. This is because existing homes already have the infrastructure ideal for childcare such as transportation, education, childcare services, and natural amenities; they are thus expected to attract further population inflow and long-term inhabitation.

To achieve such expected benefits, child-rearing-friendly housing that meets the needs of child-rearing households must be supplied first, and already-supplied child-rearing-friendly homes need to be reviewed for any shortcomings through continuous monitoring. However, most existing studies have been conducted to plan child-rearing-friendly housing and have focused on the characteristics of the households’ residential mobility and housing preferences as well as the standardization of housing suitable for them. Research on actual existing child-rearing-friendly homes has not been performed. However, the contents of previous studies on improving the housing environment for child-rearing households in Japan are as follows. First, research on child-rearing households’ residential mobility can be divided into the following areas: (1) housing and location factors involved in the selection of housing and (2) preferences identified indirectly through the physical and locational characteristics of the selected housing depending on the research method. Examples of the former include the studies by Ono and Omura (Citation1999), Takahashi and Ito (Citation2016), and Cho et al. (Citation2019). These authors identified factors of residential mobility and evaluation factors considered when selecting housing and determined the housing and location characteristics preferred by child-rearing households. Examples of the latter include the following: Takahashi (Citation2010) analyzed the relationship between the growth rate of families with children and the nature of the main environment. Itami etal. (Citation2018) identified the characteristics of residential mobility of the child-rearing household through the status of their relationship with the workplace. Saito, Coto, and Sato (Citation2014) identified the characteristics of public housing complexes in areas with alarge influx of young people and the factors that facilitate their long-term inhabitation and Sato and Goto (Citation2019) determined the characteristics of areas where numerous dual-income couples live and conditions of access to daycare centers and workplaces through an analysis of the distribution of households using childcare centers, housing data sold by private real estate companies, and population movement data. They present the necessary conditions for the creation of an urban environment suitable for child-rearing households. Furthermore, Makimura (Citation2014) analyzed the locational characteristics through field surveys in areas with many child-rearing households using the methods (1) and (2) in parallel. In addition, the authors organized town walking with astroller to determine the conditions for creating asafe outdoor environment through interviews and observational surveys for the parents who participated in this event.

Second, examples of research on the housing preferences of the child-rearing households include the following. Kumano etal. (Citation2013) investigated the function of housing building materials preferred by child-rearing households. Kumano etal. found that child-rearing households preferred building materials with noise-preventing, pollution-preventing, and deodorizing functions. Masaoka and Hirai (Citation2021) investigated the use and needs of tatami space in households with infants. They pointed out that tatami allows children to move and play freely because it has heat retention and elasticity; however, it has disadvantages in terms of hygiene, such as being prone to contamination and difficult to manage. In addition, Kobatashi, Koisumi, and Okata (Citation2010) conducted astudy on the child-rearing environment in an apartment complex and examined the possibility of child-rearing support through anetwork of residents in the complex. The results revealed that child-rearing households in the complex need light support, such as temporary care, childcare assistance, and childcare counseling, and there are volunteers who can help. In this regard, the researchers emphasized the need for anetwork entity that connects the child-rearing households who need help with the applicants who can help and aplace where they can comfortably gather for child-rearing support through anetwork of residents.

And an example of research on the standardization of housing units suitable for the child-rearing households includes the study by Hasegawa (Citation2018) of National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management. Several local governments in Japan have developed multi-family housing certification schemes for newlyweds and child-rearing households, and guidelines to provide criteria for them in choosing homes. Hasegawa (Citation2018) aimed to disseminate the local governments’ child-rearing-friendly housing certification schemes as anational policy. To this end, the author investigated the status and challenges of these schemes across the country, investigated and analyzed the importance of child-rearing households against 50 certified items, and summarized the issues for standardization of child-rearing-friendly housing. Using these results, the 「Guideline (draft) for housing and living environment considering child-rearing」 was presented. The basic concept of child-rearing-friendly housing suggested in the guidelines is as follows. (1) Asafe and secure environment for children and pregnant women, (2) an environment where children can grow up healthy, (3) acomfortable environment for raising children, (4) an environment where parents can live comfortably. Drawing upon the basic concept, the authors explain the considerations for the child-rearing households in six areas: (1) housing exclusive and shared parts of detached houses and multi-unit houses, (2) site, (3) location environment, (4) community, (5) community activities, (6) childcare support service.

Additionally, Kuzunishi conducted 12 studies from 2004 to 2021 on housing for single-parent households, whose number has increased recently, and accordingly, they require more consideration from the perspective of housing welfare. Kuzunishi has performed both independent and joint research on the creation of astable residential environment and comfortable living environment for single-parent households. Her studies revealed the housing conditions of single-parent households. Moreover, she investigated their selection of housing and residential mobility. Also, she found that it is important for single-parent households to balance work and child-rearing, whereas there are many restrictions on the residential mobility depending on the workplace, child’s school, presence of acaregiver for the child, and place of residence. Drawing upon the results of her previous studies, Kuzunishi has recently reviewed the possibility of ashare house as one of the housing types that meet the housing needs of single-parent households and summarized the architectural features of single-parent share houses across the country.

Furthermore, asimilar study by Egawa and Mariko (Citation2017) focused on houses supplied as child-rearing-friendly housing. This study investigated the high-quality rental housingFootnote6 for child-rearing households in Tokyo and identified the relationship between the use of childcare support facilities attached to the house and the surrounding residents. The results indicated that it was used not only for the residents of childcare support facilities, but also for local residents, thus fulfilling the role of local childcare support. Other studies on housing supplied as child-rearing-friendly housing include Inoue, Yokoyama, and Yokuono (Citation2013), Fujita., Jung, and Kobayashi (Citation2013), Tamamitsu et al. (Citation2014), Sakai and Hasegawa (Citation2008), and Tatada. et al. (Citation2019). Inoue., Yokoyama, and Tokuono (Citation2013), Fujita., Jung, and Kobayashi (Citation2013), and Takamitsu. et al. (Citation2014) focused on rental apartment units for child-rearing households in private construction companies. Sakai and Hasegawa (Citation2008) investigated public housing for childcare support in Hokkaido. Furthermore, Tatada. etal. (Citation2019) explored the prefectural housing remodeled in consideration of the child-rearing households in Kyoto. However, all these studies are summaries and have not been reviewed, and the scope of the investigation is also partially focused on public spaces attached to the housing and extended spaces within the housing. Therefore, academic research on child-rearing-friendly housing is insufficient.

Thus, this study aims to identify the planning conditions of child-rearing-friendly housing in response to the needs of child-rearing households by investigating the characteristics of the planned child-rearing-friendly housing design and the residents’ status of space usage. It specifically considers the case of remodeling the city-run housing projects in Kyoto, Japan. It identifies the actual conditions of residents’ use of space for four types of child-rearing-friendly remodeled houses with various designs and presents the planning conditions necessary for the supply of remodeled child-rearing-friendly housing in the future. This study is meaningful in that it is the first study to our knowledge to identify real residents’ actual use of space for child-rearing, and the results provide data that can be used to plan future child-rearing-friendly housing in Japan.

The research questions of this study are as follows.

1) What are the plan characteristics of remodeled child-rearing friendly houses in Kyoto?

2) How do the residents of remodeled child-rearing friendly houses in Kyoto use space?

2. Method

Kyoto, the target of this study, has an average total fertility rate of 1.22, which has been declining for four consecutive years since 2016; in addition, it is lower than the national average of 1.36 in Japan.Footnote7 In response, since 2016, the Kyoto City government has been remodeling vacant old municipal housing units into child-rearing-friendly houses and supplying it to encourage child-rearing households to give birth and create asafe and comfortable childcare environment. In addition, in 2017, they conducted apost-occupancy evaluation (POE) for residents to review the supply direction of child-rearing housing. This POE is arare nationwide case. Therefore, this study, which is apart of this POE results, will be good data for future child-rearing housing plans.

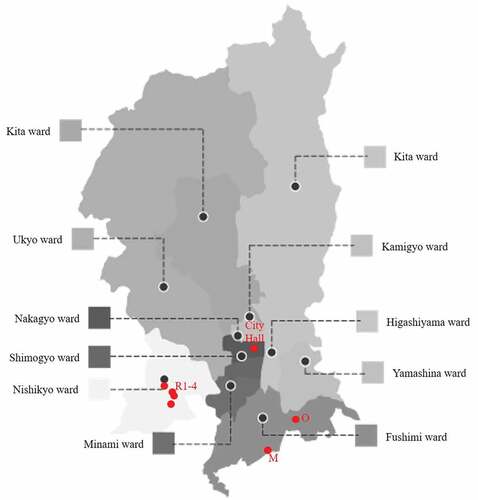

Kyoto city’s government has remodeled its old municipal housing since December2016 and supplied 210 remodeled child-rearing-friendly houses with the goal of supplying 450 units in total ().Footnote8 Of these, this study targets 55 remodeled child-rearing-friendly houses and their residents who moved into these units in April2017. Moreover, asurvey was conducted with seven of these resident households from November to December2017.

The research can be largely divided into the following: (1) analysis of the floor plan characteristics of the remodeled subject and (2) identification of the status of space utilization of residents of the remodeled child-rearing-friendly house. First, regarding the characteristics of the floor plan of the remodeled houses, public data on the remodeling project from the Kyoto city government’s website and non-public data from Kyoto city government officials were collected, compiled, and analyzed.

Second, the status of space utilization of the remodeled house residents was investigated by targeting seven households that expressed their intention to cooperate with home visits and interviews through apreliminary survey. The survey was conducted by three investigators who visited each house for 1 to 1.5 hours to conduct an observation survey and an interview. Two investigators interviewed the residents on their household characteristics, residential mobility, and satisfaction and dissatisfaction with the space, while one investigator sketched the actual conditions of space usage and interviewed and confirmed the status of use as needed.

3. Characteristics of floor plans of the remodeled child-rearing-friendly housing in Kyoto

3.1. Basic design concepts for remodeling housing

The biggest feature of Kyoto’s plan for child-rearing-friendly housing is its use of young people’s novel ideas and know-how of private-sector companies. First, in conjunction with architectural research labs at two universities in Kyoto, college students proposed remodeling plans under the concept of “a house that is easy for parents to raise children and comfortable for children to live in.” Based on this, the remodeling design concept and design conditions were prepared, and the project was conducted as acompetition for private-sector companies to participate. From among the existing four types of units in three complexes, the contestants designed and remodeled 55 units into five types (A, B, C, D, and E). The characteristics of the complexes in question were as follows: all had all been built between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s (i.e., construction age of 30–40 years) and were 4 to 11 stories high () (). In addition, the housing area was 51.25 to 58.28m2, which meets Japan’s minimum residential area standard of 45m2 for afamily of four with two children under the age of 10, but it is lower than the standard of 85m2 for urban residential areas.

Table 1. Overview of the complex & remodeled housing.

Accordingly, conditions for the design of the remodeled child-rearing-friendly housing proposed at the time of the competition in 2016 were as follows. First, it should be created in an environment where parents can easily raise their children and have afloor plan and amenities convenient for children. Second, it should be designed so that children can experience the traditional residential culture through the inclusion of Japanese-style rooms with traditional Japanese tatami flooring (hereafter washitsu). Third, it is necessary to improve the residential modernity, such as through hot water supply, heat insulation, and sound insulation, and to secure the general accessibility and durability of the house, so that it can be used for along time with easy maintenance (Kyoto City Housing Corporation, Citation2016).

In addition, considering specific images provided for the first condition (), housing that accommodates parents raising their children must meet the following requirements: easy movement for performing household chores, storage spaces for children, floor plans in which parents can monitor their children while doing household chores (e.g., akitchen with afull view of the living room and other spaces), sufficient living room space for children to live and play, infant-oriented movement, and sufficient space for astroller to be placed near the entrance. That is, housing convenient for children needs afloor plan where children can study and play while feeling protected by parents, that guarantees an independent space for children, where children can feel or see their family, and that has astorage space convenient for children to organize themselves. The requirements for such housing also vary depending on the age of the child (Kyoto City Housing Corporation, Citation2016).

Table 2. Changes in housing needs by children’s age.

3.2. Floor plan changes and features before and after remodeling

The primary remodeled floor plan based on the design concept and conditions proposed by the Kyoto city government is shown in . Since the structure varies for each remodeled house, the degree of design freedom of the Cand Dplans, which are corridor-type rahmen structures, is higher than that of the stair-type wall structures of the A, B, and Eplans. Commonly, both Aand Dare equipped with one or more washitsu covered with tatami, traditional Japanese flooring, even after remodeling so that children can have access to Japanese culture.

Table 3. Characteristics of the plan before & after remodeling.

The characteristics of each floor plan are as follows. In the Aplan, Toorinawa,Footnote9 the space for raising children, is amodern interpretation of Toorinawa from Kyoto’s traditional Kyomachiya houses.Footnote10 An open living room and dining kitchen are placed sideways to secure aspacious play area for children, and there is aseparable sliding door to expand the space as needed.

The Bplan is a“flexible plan with ashared space.” It is designed to install sliding doors that can be detached so that the living room, which is aspace shared by the family, can be used based on the family’s needs, such as aroom for children’s growth. Moreover, two large storage spaces are installed in the living room for children’s items, which continue to increase as they grow older.

The Cplan is a“plan with aflexible personal space.” It has ceiling-high mobile furniture between rooms so that children can separate them and use the space when an independent space is needed. Further, this makes it convenient to use spaces requiring the use of water such as the changing room, laundry room, bathroom, and kitchen by enabling users to cross the area quickly. It also has aface-to-face kitchen that enables the parents to watch their children playing in the living room or bedroom.

The Dplan is as “plan with free and diverse private rooms.” It has amulti-purpose room between the two washitsu, allowing it to be used for various purposes according to the residents’ lifestyle. It also has awalk-in closet and open windows to help the family feel each other in the room. Like Type C, it also has aface-to-face kitchen that allows the parents to watch their children playing in the living room or bedroom.

The Eplan is a“plan of bringing the household space to the center.” It features aface-to-face kitchen in the center of the house, reducing the movement required for household chores. It also has aliving room and dining room with awashitsu floor in front of it so that parents can watch their children easily. Further, it has alarge walk-in closet to secure storage space.

4. Evaluation and the status of space usage by the residents of child-rearing-friendly housing

4.1. Characteristics of the survey subjects

Since none of the interviewees resided in housing with the Bplan, four types of housing excluding the B-plan were surveyed. These included two cases each of A, C, and Dplans and one case of the Eplan ().

Table 4. Characteristics of Residents of remodeled house.

The surveyed family heads of the seven households were all young people in their 20s and 30s, and six of the households had children who had yet to enter elementary school, except T, who had children attending elementary school. In addition, five households were single-mother households, and only two had parents who worked full time. As for the reason for relocation, three households cited “because their homes have become too small due to the growth and birth of their children,” while two cited “the burden of expensive rent.” On the other hand, five households cited that they chose child-rearing-friendly housing units over other options because “the rent is less expensive than ordinary private rental homes.” This result indicates that the supply of child-rearing-friendly homes using existing public rental housing is agood opportunity for child-rearing households that need to move to alarger house to accommodate the birth and growth of their children.

4.2. Status of space utilization of the survey subjects

The survey on the status of space utilization was conducted by visiting the residents’ houses to visually understand the furniture layout and use of space. The residents were interviewed about their use and evaluation of each room, the space they generally use, and any inconveniences. The results are presented in and . In addition, based on the actual conditions and evaluation of the residents’ use of space, the design conditions of child-rearing-friendly housing can be reviewed in terms of room composition, storage space, chore space, and variability.

Table 5. Evaluation of the status of space usage of the residents of child-rearing-friendly housing.

Table 6. The space usage by behavior.

4.2.1. Room composition

According to the investigation, all six households with A, C, and Dplans removed the sliding doors of the south-facing rooms and extended the space to the dining kitchen or living room and dining room. This room, which is sunny and pleasant, was selected as the space used most frequently by all family members for activities such as hanging out with the family, television viewing, eating meals, entertaining guests, and studying and playing by children. This tendency to heavily utilize this room is especially notable in households with children under the age of one (S, O, and N) who need alot of care. Only in the case of Tdid the children use the colder north-facing room in the winter.

Meanwhile, all four plans of the surveyed child-rearing-friendly households had installed open windows or removable sliding doors, as mentioned above. They planned to use the entrance and living room as open spaces rather than compartmentalizing the rooms by walls. Such open plans have the advantage of being able to expand space, observe children’s behavior such as coming home, and observe the family’s presence. However, they also have disadvantages: as the overall space is open, the efficiency of heating and cooling systems is reduced. It also requires consideration for privacy issues, such as abarrier to prevent the household from being seen from the entrance. This consideration is necessary to separate the entrance to secure privacy.

In addition, the Kyoto city government is installing more than one washitsu in every plan to provide children with asense of traditional culture in their daily lives; the assessment of washitsu varies from person to person. Among the positive reviews was an opinion (H) that tatami is cushioned and safe for children to run around, and an opinion (M) that at least one tatami room is needed for psychological peace. On the other hand, there were many negative reviews in households with children under the age of one. Such opinions (K, T, and O) stated that tatami is difficult to clean and is prone to contamination when children spit out food or there is aneed to change diapers. In fact, one household (M) used mats or carpets to prevent furniture stains on the tatami because they felt burdened by the obligation to restore the house to its original state when moving out. Rather than mandating the installation of washitsu, it may be more desirable to allow the households to choose it as an option.

4.2.2. Storage space

As children grow older, amore spacious storage space is needed. In addition to the storage closet already installed, some households with one child yet to enter elementary school, except T, used the remaining north-facing living room as astorage space. There was no shortage of storage space even during the observation of the scene. On the other hand, T, which has two children in elementary school, had alarge walk-in closet installed, but it was not enough to accommodate the children’s items added after they entered elementary school along with the volume of clothes that increased with their physical growth; therefore, they had stored items all over the house. Thus, it is necessary to determine how to secure enough space to store items that increase as children grow.

4.2.3. Space for household chores

In all four plans, the changing rooms, laundry rooms, and bathrooms are located in one place, where children can take off their clothes to be washed with awashing machine. In particular, the Cplan, in which residents can directly move from the kitchen into the changing room, laundry room, and bathroom, received positive reviews for direct entry from the kitchen as it requires less movement and, hence, less time to do household chores (K, S, and T). Considering that there is ahigh demand for child-rearing-friendly housing from single-mother households, the concentration of space for household chores to optimize movement is effective in supporting childcare.

Meanwhile, in the case of kitchens, there are two types of kitchens: one with asink attached to the wall and aface-to-face kitchen facing the living room. There were varying preferences and evaluations depending on the age of the child in the case of the face-to-face kitchen. First, in households with young children under the age of three, the prevailing positive assessment was that parents were relieved to be able to watch their children in the face-to-face kitchen (M, K, S, O, and N). On the other hand, some pointed out that measures to prevent sudden entrance of children into the kitchen were needed (M, S, and O). Next, H, who has afive-year-old child, said that the kitchen attached to the wall is easier to use with children compared with the narrow face-to-face kitchen, and that it is also better to use when there are guests who come into the kitchen as it is spacious. Thus, for kitchens, it would be ideal if choices could be made based on the children’s maturity and age.

4.2.4. Variability

In the case of Cplan, amobile storage unit is used so that the space can be detached if the child grows up and needs an independent room. Although the user manual was distributed when moving in, both households said that it was not easy for non-experts to move it, and Kis using the house in the condition identical to that of when moving in. In addition, Ksaid that they do not need amobile storage unit as they will not give their children aseparate room even after they grow up. They also pointed out that ready-made storage equipment is inconvenient to fit, and so it is necessary to consider the size of such equipment when installing astorage case. Meanwhile, in the case of S, the household head’s father, who works in the construction industry, had expanded the space by moving the cabinet toward the wall. In this way, if special work is needed that cannot be performed by residents themselves, support to help them will be needed.

On the other hand, similar to the cases of Kand S, differences in the ways of addressing housing needs depending on their level of housing literacy could be seen from Hand Mliving in Aplan type housing. Both pointed out that the entirety of the house was visible from the entrance and that the north-facing living room was cold. While Hused the north-facing living room as the living room, Memployed ado-it-yourself solution to block the view and prevent the draft from the front door (). This is because Mhad architectural knowledge and experience through their father who worked in the construction industry. Therefore, it is necessary to provide away for residents to refit the space according to their needs.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the case of Kyoto, which remodeled vacant old municipal housing units into child-rearing-friendly homes, to examine the planning conditions of such housing. All the subjects of this study are child-rearing households with children who have entered or are yet to enter elementary school, and the following planning conditions necessary for the supply of child-rearing friendly housing based on residents’ status of space usage have been identified.

(1) Securing the ease of expansion of space considering the intensive use of rooms by child-rearing households

In the remodeled child-rearing-friendly housing units in Kyoto, the space is divided by sliding doors to make it possible to expand or separate it as children are born and grow. This space is planned as an open space for parents to watch children from all directions of the house. This ease of space expansion is highly effective in securing comfort considering children’s growth and ensuring the safety of children through securing vision.

According to the resident survey, this study found that most households removed the sliding door as intended by the plan, and the expanded space was concentrated in the south-facing room as it had apleasant environment. In addition, various activities occurred in this expanded space, such as television viewing, eating, studying and playing by children, and entertaining guests. Such usage was more pronounced in households with children under the age of one who need alot of care. On the other hand, due to child-rearing households’ tendency of space usage, the north-facing room, which is relatively less pleasant, was used as astorage space, causing abias in the use of this room due to the environmental differences. Furthermore, it was commonly pointed out that the expansion and openness of the space led to low heating efficiency. Therefore, securing the expandable space is very useful for child-rearing households with young children that live in almost one space, and it is important to secure comfort such as south-facing arrangements. In addition, it is necessary to pay attention to the placement of rooms and the location of heating and cooling equipment so that abias in the use of rooms does not occur due to differences in their environments. Furthermore, the remodeled cases in Kyoto do not provide astorage place for the sliding door that was removed to expand the space. Thus, in the resident survey, residents expressed dissatisfaction with the considerable storage space for the sliding door due to its large volume. Therefore, when planning open space, it is necessary to consider that the residential space can be fully utilized by securing aseparate space for storing temporary walls or windows that need to be stored due to space expansion. Such space can be secured by providing awarehouse outside the house or, in the case of acollective house, in the main building or acommon warehouse within the complex.

(2) Securing sufficient storage space

In remodeled cases in Kyoto, the existing storage space was expanded by adding built-in closets or walk-in closets to respond to the housing needs of the child-rearing households for sufficient storage space. Securing enough storage space can be highly effective in responding to the increased storage volume as children grow and in increasing parental efficiency.

According to the resident survey, there were no complaints about the storage space, as the north-facing room, which is left over due to the households’ focus on the other rooms, has been mainly used as storage space in two-to-three-person households with children yet to enter elementary school. However, on-site inspections confirmed that afamily of three with two elementary school children has more items than ahousehold with pre-school children, and they have storage furniture everywhere to store their children’s items that have increased in both number and volume. Furthermore, the house of this household is the smallest among the case houses with an exclusive area of 51.25m2, and has only one walk-in closet. In the case of housing that lacks storage space, it is also necessary to secure an external warehouse or acommon warehouse in the case of acollective house so that seasonal items can be stored. In addition, the storage space plan needs to be able to respond to changes in space needs by not only securing the quantity, but also introducing planning elements that allow the storage space and the room where the storage space is located to be integrated and used.

(3) Reducing movement within the household space

In the remodeled child-rearing-friendly housing units in Kyoto, household spaces such as changing rooms, laundry rooms, bathrooms, and kitchens were concentrated to one side to reduce movement and realize aspace convenient for parents to take care of their children. This intensive arrangement of water-using areas is highly effective in improving the efficiency of housework and shortening the housework time in child-rearing households that must perform both childcare and housework.

In response, all households surveyed commented favorably about the convenience of their houses, indicating that intensive arrangement of household spaces is effective in supporting childcare.

(4) Support for improving residents’ housing literacy in their daily lives

The remodeling case of Kyoto applied specialized planning elements for child-rearing households, such as introducing awashitsu to preserve the traditional culture, adding variability by setting up amobile storage room to separate the space as the child grows, and installing aface-to-face kitchen to observe the child while working. This can be evaluated as asuitable housing plan to support child-rearing households in terms of forming the child’s identity as aJapanese and securing the child’s independent space and stability. Meanwhile, the housing plan specialized for specific child-rearing households presented adilemma, because it can lead to inconveniences in daily life depending on the growth of children and changes in the family life cycle.

In the survey of residents of the remodeled housing units, preferences in the use of washitsu and face-to-face kitchen differed depending on the children’s age. The study results of Kumano etal. (Citation2013) indicated apositive evaluation in that washitsu is safe for children owing to the cushioning properties of tatami mats. However, there are also many disadvantages considering that tatami is easily contaminated in households with infants. In particular, the demand for mobile storage space differed greatly depending on their architectural knowledge and experience. For aparticular household with abundant architectural knowledge and experience due to the influence of their parents involved in architecture, the residents solved housing-related problems themselves. Therefore, it is desirable to find ways to support residents who can utilize and manage their own space according to their life stages and family situations rather than responding to all varying demands depending on the child’s age. Specifically, regarding remodeled cases in Kyoto, it can be effective to choose an option instead of compulsory installation of Japanese-style rooms and to provide amanual on how to manage tatami or provide aservice to help manage the Japanese-style room. In addition, it is necessary to ensure that all households can use the sliding door or storage cabinet without difficulty, such as by providing instructions on how to use it, examples of usage, or providing assistance when needed to move furniture.

The remodeling of ahouse has many limiting factors considering the planning factors specialized for child-rearing households, because the degree of freedom in design is low compared to anew construction, and the cost required for facility renewal increases as the construction period increases. The remodeled cases in Kyoto have along construction period of 30 to 40 years, and the exclusive area is small, ranging from 51.25 to 58.28m2. These cases were planned with apriority to secure an area and storage space suitable for the growth of children and reduce household movement lines. In addition, aresident survey confirmed that these planning elements are effective for child-rearing households. However, these cases need to be supplemented because they lacked detailed planning elements such as prevention of pinching of sliding doors, rounding of corners, securing safety such as double door locks, use of eco-friendly interior materials, use of building materials with pollution prevention, and deodorization functions. In addition, in the cases in Kyoto, although the scope of remodeling is limited to the exclusive area, it is necessary to consider the extension of the scope to the common area within the complex that falls within the residential living area. In particular in the resident survey, residents expressed their disappointment at the lack of opportunity for interaction between child-rearing households in the complex. Therefore, as suggested in the study by Kobayashi, Koisumi, and Okata (Citation2010), it may also be possible to provide avacant space within the complex as acommunity place for child-rearing households, so that residents can form anetwork and support each other in childcare naturally.

Some limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting the results of this study. First, this study only involved Kyoto City, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Therefore, future studies should investigate similar case studies in other cities and countries. Second, this study was limited to 13 cases, and the analysis was limited to the qualitative analysis method. Therefore, future research should include surveys based on alarger number of cases, and aquantitative analysis should be applied to enable generalization of research results.

Acknowledgments

This paper is developed on journal article 8117 from the Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting (2018) published by Architectural Institute of Japan, appearing tenth on the reference list. We would like to thank Dr.M.Kono, Prof. M.Takada and Prof. K.Narukawa from Kyoto University of Arts and Crafts for their collaboration and valuable advises in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 OECD (2021), Fertility rates (indicator). doi: 10.1787/8272fb01-en (Accessed on 2 August 2021)

2 As of 2019, Japan’s total fertility rates were 1.36 lower than the OECD average.

3 The basic programs for housing can be found at https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001123468.pdf

4 Residential support for child rearing households, which is conducted by local governments, has direct ways to supply housing and indirect ways to subsidize housing purchase costs or rent. In the direct approach, public housing owned by local governments are remodeled, and housing is provided to newlyweds and child-rearing households. This includes Kyoto City, Nagano Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Nagoya City. In the indirect approach, families can be supported in buying, renovating, or renting ahouse. For example, Fukushima Prefecture provides up to 700,000 yen when anew resident from another region buys ahouse to settle in, and Kitakami City provides up to 1million yen when newlyweds or families with children buy anew house in adepopulated area. In addition, Saitama Prefecture, Maizuru City, and Kobe City have programs to support up to 500,000 to 1million yen when they buy or renovate existing houses. Regarding private rental housing, Utsunomiya City, Shizuoka City, and Kobe City subsidize expenses when newlyweds and families with children rent ahouse in adepopulated area.

5 The term “child-rearing-friendly housing” used in this study refers to ahouse where parents in achild-rearing household can raise their children with confidence and care in consideration of the children’s healthy growth and development.

6 This project has been promoted as amodel project by Tokyo Metropolitan Government from 2010 to 2014 for the housing stability of child-rearing households. There are two types of houses: new houses and renovated houses. (https://www.juutakuseisaku.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/juutaku_seisaku/child-care-chintai.html)

7 The total fertility rates in Kyoto City and Japan can be found at https://www2.city.kyoto.lg.jp/sogo/toukei/Publish/Analysis/News/119TFR.pdf

8 The eligibility for child-rearing-friendly remodeled homes is limited to households with children yet to enter middle school that are living or working in Kyoto. By limiting the period of occupancy to the end of theyear when the youngest child turns 18 years old, more child-rearing households are being given the opportunity to move in.

9 Tooriniwa is anarrow and long passageway connecting the entrance of the store space of aKyomachiya, which is long both ways, to the kitchen and courtyard. It has the same height as the ground where shoes are worn.

10 Kyomachiya is atraditional wooden house in Kyoto that dates back to the mid-Heian period (794–1185), and today’s prototype was created in the mid-Edo period (1603–1867). The Kyomachiya house (built for both occupation and habitation) consists of astore space in front of the building and aresidential space in the back. The Kyoto Municipal Ordinance defines it as awooden Hirairi roof building with three stories or less and built before 1950.

References

- Cho, H., M. Takada, K. Narukawa, K. Kono, E. Itami, M. Nakanisi, and K. Shiki. 2019. “The Study on Residential Preference of Residents Living at Public Housing for Child-Rearing Household.” AIJ Journal of Technology and Design 25(60): 807–812. Retrieved 1 February 2021. doi:10.3130/aijt.25.807.

- Egawa, K., and S. Mariko. 2017. “A Study on Use of Child Care Facilities with Rental Housing for Families with Small Children.” Bulletin of the Faculty of Human Sciences and Design, Japan Women’s University, 64: 67–76. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021. http://id.nii.ac.jp/1133/00002583

- Fujita., K., J. Jung, and H. Kobayashi. 2013. “Evaluation by Dwellers and Living Condition on Rental Apartment Houses for Child-rearing Household: Case Study of “BORIKI MUSASHINO”.” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, Architectural Institute of Japan 2013: 1397–1398.

- Hasegawa, H. 2018. “Study on Planning Method of Housing considering Safety, Relief and Ease of Child-care.” Research Report of the National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management, Retrieved 1 February 2021 http://www.nilim.go.jp/lab/bcg/siryou/rpn/rpn0059.htm

- Hidaka, S., C. Murosaki, and L. Kuzunishi. 2017. “Architectural Planning Characteristics of Share House for Single Mother Households and Its Evaluation from the Viewpoint of Living.” Urban Housing Sciences (99): 84–89. Retrieved 4 June 2021 doi:10.11531/uhs.2017.99_84.

- Inoue., Y., S. Yokoyama, and T. Tokuo. 2013. “Study on the Possibility of Way of Living de-nLDK Seen in Housing Child Care Support.” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, Architectural Institute of Japan 2013: 1395–1396.

- Itami., E., M. Kono, K. Yano, K. Shiki, H. Cho, M. Nakanisi, and K. Narukawa. 2018. “Child-Rearing Households’ Selecting Tendency of Housing Environment in Applicants for Public Housing.” Proceedings of the Housing Studies Symposium 13:91–97.

- Kobayashi, S., H. Koisumi, and J. Okata. 2010. “Reappreciation and Problems of Housing Complexes from the Viewpoint of the Child-Care Environment: Based on the Research of the Consciousness of Residents of Government-built Housing Complexes.” Urban Housing Sciences (17): 38–43. Retrieved 3 June 2021 10.11531/uhs.2010.71_38.

- Kondou, T., and L. Kuzunishi. 2017. “Possibility of Shared Housing for Single Mother Household.” Urban Housing Sciences (79): 77–81. Retrieved 4 June 2021 doi:10.11531/uhs.2012.79_77.

- Kono, M., M. Takada, K. Yano, K. Narukawa, H. Cho, M. Nakanishi, E. Itami, and K. Shiki. 2018. “About Building Elements of Dwelling Houses on considering of Child-Rearing Households-As Examples for Renovation Housing of Child-Rearing Households in Kyoto City-Research on Housing Policy by Child-Rearing Households (Part 2).” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, Architectural Institute of Japan2018: 233–234.

- Kumano, Y., T. Yokoi, Kanemaki, M. Tamura, J. Koga, T. Kurihara, M. Morimoto, etal. 2013. “The Questionnaire and Consideration about Housing Construction Material at the Time of Child-rearing.” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting Japan Society for Finishings Technology 15–18. Retrieved 3June 2021. doi:10.14820/finex.2013.0.15.0.

- Kuzunishi, L. 2008a. “Problem Mismatch between the Process of Securing Permanent Housing and Housing Policy for Single Mother Households in Japan.”Proceedings of International Symposium on City Planning. 554–563. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021. https://kuzunishilisakenkyu.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/e8ab96e696879.pdf

- Kuzunishi, L. 2008b. “Moving Situation and Choice of Residential Area for Single Mother Households in Rural Area and Metropolitan Area: Case Study of Tottori Prefecture and Osaka City.” Urban Housing Sciences (63): 15–20. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021 doi:10.11531/uhs1993.2008.63_15.

- Kuzunishi, L. 2009. “Fundamental Study of Single Father Households’ Housing Situation: Comparison between Single Father Households and Single Mother Households.” Urban Housing Sciences (64): 129–136. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021 doi:10.11531/uhs.2009.65_59.

- Kuzunishi, L. 2010. “Single Mother Households ‘ Hosing Condition in Tottori Prefecture, Osaka Prefecture, and Osaka City: The situation of housing tenure, minimum housing standard, housing expense to income ratio.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 75(652): 1533–1540. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021. doi:10.3130/aija.75.1533.

- Kuzunishi, L. 2013. “Single Father’s Moving Situation Form Marital House and Child Care Environment: Private Supporter and Balancing Child Care and Job.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 78(684): 421–428. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021. doi:10.3130/aija.78.421.

- Kuzunishi, L., C. Murosaki, and A. Okazaki. 2018. “The Nationwide Trend of Shared Housing for Single Mother Households -the Situation of Management, Type of Building, Rent Amount, and Care Services.” Urban Housing Sciences (103): 177–186. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021 doi:10.11531/uhs.2018.103_177.

- Kuzunishi, L., and E. Oisumi. 2008. “The Housing Issues of Single Mother Households in Rural Area: Focus on the Acquisition of Homes.” Journal of the Housing Research Foundation “JUSOKEN” (34): 255–266. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021 doi:10.20803/jusokenold.34.0_255.

- Kuzunishi, L., A. Okazaki, and C. Murosaki. 2018. “The Possibility of Shared Housing for Single Mother Households Using Stock of Apartment Complex Planning Process of Renovation and Operations Management.” Urban Housing Sciences (103): 144–149. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from 4 June 2021 doi:10.11531/uhs.2018.103_144.

- Kuzunishi, L., Y. Shiozaki, and Y. Horita. 2005. “AStudy on Insecure Habitation of Single Mother Households.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 70(588): 142–152. Retrieved 4 June 2021. doi:10.3130/aija.70.147_1.

- Kuzunishi, L., and Y. Shiozaki. 2004. “Difference of Housing Situation between General Households and Single Mother Households: The Analysis of Tenure, Area of Floor Space, Housing Expenditure and Rent.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 69(581): 119–126. Retrieved 4 June 2021. doi:10.3130/aija.69.119_4.

- Kyoto City Housing Corporation. 2016. “The Public Recruitment Guidelines for the Child-Rearing-Friendly Housing Childcare-Friendly Housing Remodeling Project in Kyoto City.” Retrieved February 1, 2021 from 1 February 2021 http://www.kyoto-jkosha.or.jp/ijikoujika/rinov/20160726bosyu.pdf

- Makimura, H. 2014. “AStudy of the Assessment Indices about Housing & Regional Conditions Which Support to Take Care of Children and Women’s Works.” Journal of the Institute of Religion and Culture, 27: 93–115. Retrieved June 3, 2021 from 3 June 2021. http://repo.kyoto-wu.ac.jp/dspace/handle/11173/1569

- Masaoka, S., and Y. Hirai. 2021. “The Uses of Tatami Space and Needs of Tatami-mat in Families with Infants.” Memoirs of the Faculty of Education, Shimane University 54: 63–70. Retrieved June 3, 2021 from 3 June 2021. https://ir.lib.shimane-u.ac.jp/52536

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. 2016. “Basic Act for Housing.” Retrieved February 1, 2021 from February 1 https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001123468.pdf

- Ono, H., and K. Omura. 1999. “Basic Study on Urban Development from the View Points of Housing Choice of Two-income Families with Children.”Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan 34: 289–294. Retrieved February 1, 2021 from February 1. doi: 10.11361/journalcpij.34.289.

- Saito, C., H. Coto, and H. Sato. 2014. “The Factors of the Young People’s Inflow and Settlement in the Housing Development Which Is in the Inconvenient Traffic Suburb Area in Yokohama City.” Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan 49(3): 807–812. Retrieved February 1, 2021 from February 1. doi:10.11361/journalcpij.49.807.

- Sakai, S., and M. Hasegawa. 2008. “Research on Planning of the Public Housing for Child Care Support.” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. F-1, Urban Planning, Building Economics and Housing Problems 2008:1473–1474.

- Sato, S., and Y. Goto. 2019. “Transportation and Commuting Behavior according to the Type of Residence of Double-income Childrearing Families in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area.” Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan 54(3): 1570–1575. Retrieved June3 2021 from doi:10.11361/journalcpij.54.1570.

- Takahashi, M., and A. Ito. 2016. “Trends in Social Mobility and Aspiration toward Comfortable Living among Young Women: Findings from a2015 Questionnaire Survey of Social Movement in Kobe, Takasaki City University of Economics.” Studies of Regional Policy18: 49–68. Retrieved February 1, 2021 from http://www1.tcue.ac.jp/home1/c-gakkai/kikanshi/ronbun18-4/08takahashi_ito.pdf

- Takahashi, M., K. Narita, and H. Ochiai 2010. “AStudy on the Residence Environment Suitable for Childcare, Policy Research Institute for Land Infrastructure and Transport.” Retrieved February 1, 2021 from https://www.mlit.go.jp/pri/houkoku/gaiyou/pdf/kkk92.pdf

- Takamitsu, S., K. Fujita, A. Irisawa, K. Takahashi, and H. Kobayashi. 2014. “Evaluation by Dwellers and Living Condition of the First Year on Rental Apartment Houses for Child-rearing Household: Case Study of “BORIKI MUSASHINO” Apartment House Part2.” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, Architectural Institute of Japan 2014: 1129–1130.

- Tatada., R., C. Murosaki, M. Takada, M. Hinokidani, and M. Nakanishi. 2019. “Recognition of Each Other’s States of AFamily and the Child at the Time of the Use Consecutive Two Rooms of Housing Complex Dwelling Unit: ACase Study on the Supportive Built Environment for Child Rearing in Public Housing Estate, Part1.” Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, Architectural Institute of Japan 2019: 1117–1118.