ABSTRACT

Pavilions are flexible, open architectural structures, usually erected in parks and gardens. And they played a significant role in the political and cultural propaganda through international exhibitions in the 19th century, as well as in the presentations of new technologies and materials. By focusing on the concept of temporality, this study takes a novel approach and examines the role of the pavilion from the perspective of nomadic, wandering cultures through a case of Serpentine Pavilion Project. This study is based on the interpretive and critical approach which relies on gathering cases and references about the phenomenon or literature in hand. We provide a history overview and trace the changes in the concept of place at the dawn of the modern era, investigating how the Serpentine Pavilion reflects a modern understanding of placeness. Essentially, it argues that the pavilion, as a special temporary architectural form, can be used as the foundation of modern discourse on placeness. As a material and spatial alternative to such placeness, the pavilion constitutes an important architectural type.

1. Introduction

Held annually, the Serpentine Gallery’s Pavilion Project presents artwork that illustrates a materialistic way of expressing new ideas, despite being constructed as a temporary structure in the museum’s space. The contemporary pavilion seems to have established itself as a symbolic work to declare the identity of the architect and the agenda of contemporary urban architecture. Pavilion began to appear in the architectural discourse when the exhibit hall constructed as a political and cultural exhibit for world fairs popularized in the 19th century and was named pavilion. Through the exhibitions’ pavilion, architects of the time presented new technologies and forms symbolizing their culture. Modernists later used it as a model to demonstrate their own architectural solutions or the architect’s biography (Dodds Citation2005). Dodds (Citation2005) and Samson (Citation2016) highlighted its theoretical role, focusing on exhibition constructions such as the Barcelona Pavilion. Their studies also showed that the pavilion was essentially a reflection of the constructional form of wandering and nomadic cultures, the opposite of settlement. From this, we reveal that it is an architectural form expressing modern places based on mobility and nomadic culture that existing theories of place based on fixed settlements cannot explain. However, the role of the pavilion as a spatial reproduction of a particular thought and institution ironically stems from its temporary nature. The definition of a pavilion is a “light temporary or semipermanent structure in the garden”. According to this definition, the main attributes of the pavilion are lightness and temporality. If the monument is a structure fixed to the ground with a ceremonial spirit that yearns for eternity, the pavilion is a tent built for a short time on a field where certain valid experiences are held during specific moments. In other words, if a monument is built to permanently preserve a particular spirit, the pavilion is a surface spread out to relish events of relatively momentary experiences and perceptions. In this light, the pavilion has the potential to become an architectural form that exposes the historical limitations of discourse on place, which is based on the permanence from poetic dwelling and location of construction and universality (Heidegger Citation1971). This study is based on the interpretive and critical qualitative approach which relies on gathering cases and references about the phenomenon or literature in hand. This approach was done by collating, analyzing and interpreting data to reach acceptable generalizations. Therefore, this study argues that the pavilion, as a special temporary architectural form, can be used as the foundation of modern discourse on place. To this end, we trace the changes in the concept of place at the dawn of the modern era and investigate how the Serpentine Pavilion, as a historical one and a modern artwork, reflects contemporary understandings of place.

We argue that modern universal architectural spaces result from “placelessness.” Moreover, they are new sites that enable us to discover the conditions of a “new place” that reflects modern life and thoughts.

2. From rooted place for dwelling to floating space for events

The tendency to emphasize the “place” as part of an act of reflecting on modernity stems from Heidegger, who realized the existence of modern people. The place is understood as “the material background and specific location where humans build social relationships and have a subjective and emotional attachment to.” (Cresswell Citation2013). In other words, the place is a way in which humans exist in relation to the world and refers to their existence itself, including the existence being granted meaning or expressing it.

This concept of the place emphasizes “rooting down” in contrast to a sedentary agricultural life and a wandering nomadic one and argues that the place is the spatial construction of the continuous time of the sedentary life. Citing Hölderlin’s verse, “Human beings live on the earth poetically.”(Heidegger Citation2000). Heidegger considered the combination of the place of dwelling and its meaning to be its essence. The Greek temple that he used as an example reveals the nature of the place, which had been concealed by the construction of a particular site and by it “standing there.” According to Heidegger, Das In-Sein is already an entity that “resides” and cannot be separated from the site it is located in, thus establishing its own space. Dasein can become an open and creative being through art because the essence of artwork is a phenomenon of truth weaved by concealing and revealing. In other words, Dasein earns its location, or place in the world by building its own reproduction. The spatial experience associated with a particular spirit formed through a relationship with nature provides a figure to the location through a boundary and threshold. In addition, the building as a whole integrated into the act of building is a container that collects through the object–body fourfold through its relationship with nature and is simultaneously a “place of dwelling.” Heidegger viewed the architectural space, integrating construction and reproduction as a “place” through the equivalence of the building–dwelling.

However, as the internationalist style and urban design ideologies based on modernism were universalized along with the emergence of an industrial society, the modern urban architecture landscape, distinct from the historical landscape, changed the perception of the place where it took root and the architectural space it was representing. Notably, Relph (Citation1976,) and Shultz (Citation2019) declared that modern urban architecture, characterized by “an open and fluid vast space that causes a loss of a sense of direction, a weakening of the symbolism of façade, and a weakening of regional differences,” is a space of “Placelessness.” The modern space is difficult to provide the experience of the traditional “location” due to its tendency to pursue universality and technological rationality, replacing regionality and history.

Interestingly, modern architects agonized over the format of expressing modernity, which is the reason for “placelessness” in a symbolic way. S. Giedion, in particular, believed in the necessity of monumentality in modern architecture and demanded the reintroduction of symbolism into architecture in a way different from that of the past.

As modernists who rejected the foundation and corrupted ornament of the past looking for a stable form that would maintain the new values of the time, Cenotaph for Newton (1784) by Etienne-Louis Boullée, Barcelona Pavilion (1929) by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and others played the role of messengers of the symbolic values despite their temporary quality.

Since transportation technology has become commonplace in the modern age, lands and regions have become fragmented and the scope of urban life has been greatly expanded, depriving the proximity of the former era; however, at the same time, it has reconnected things that had been disconnected and were far apart, bringing back a different sense of proximity-remoteness. This has revitalized the regional importance and accelerated the speed of globalization. In a global modern society where communities in varying places can be formed and dismantled by electronic network technology, individuals can “select” a place without a connection to existing places or communities. Even if there is a place where the community and the place are equivalent, the place is experienced differently for each member (Massey Citation1994).

From the perspective of viewing nomadic dwelling in its essence, the state of fixating the place is rather special and exceptional. From this point of view, a home is the basis for discovering and occupying the surrounding environment – it is more of a boundary rather than a place and an act of producing differences (Dal Co Citation1990).

Francesco Dal Co saw that the solidarity of the “dwelling–home–place” was dismantled by the de-mythologization of the dwelling. He also saw that all the roots and the “loss of home” outside of the dwelling were the essence of life. He believed that the essential character of a home lies in wandering as an indispensable alternative to establishing a dwelling.

The modern way of existence continues to perceive the place as a production of an event, rather than a revelation of something that permanently exists (Rubio Citation2004). Defining dwelling and location as a continuous production of individual events is to understand the binary oppositional relationship between settlement and wandering as a noncontrastive relation. An event refers to the act of establishing a place and to transform a universal and permanent place into a separate, transient form of occupancy (Derrida Citation1986). With the emphasis on location as a production of events, the uniqueness of the physical site and the importance of fixed forms show a tendency to fade.

The efforts to establish the unique symbol of the modern civilization drive-by transportation technology and mass industrial production aim to overcome the force of gravity and thus regard the act of “taking root” at a place as a loss of uniqueness and peculiarity. The ideal expressed by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s spherical house, which first appeared in the 18th century, was a denial of constructive foundation that had been constrained by gravity. The anti-constructive foundation and simultaneity enabled by amplified mobility brought freedom and transparency into the surface of architectures (Giedion Citation2009).

Meanwhile, the sense of placelessness and mobility weakened the uniqueness bound with a site and a place and the authenticity derived therefrom. It is well-known that the process of “commercialization” where the uniqueness of a good separated from a place transforms into disposableness and repetitiveness has been accelerated by the culture of world fairs popular in the 19th century. On “placelessness,” the architecture of the 1970s referred to the emotional connection between humans and places or environments “topophilia” (Tuan Citation1974) and highlights the endemism and regionality of lands and materials. In addition, Frampton emphasized the architectonic suitability for a particular site through critical regionalism and urged resistance against the homogenization trend of modern capitalism through the means of specific materiality (Frampton Citation1983).

Site specificity, which appeared in art, began with the early work of minimalism and that of Richard Serra, and confronted modernist tabula rasa in the context of a particular land to have meaning only in that space. The works cannot be moved to the exhibition without dismantling them, and thus, they have been given authority because of this (Miller Citation2013). However, subsequent critical works take issue with the institutional influence of the framework of a particular place itself, break down the equivalence between it and the work, and emphasize the work or process of the place. Considered important in performance art are “gestures, events, and performances performed within the framework of temporary boundaries,” and the work is understood to reflect non-configuration and temporality as a movement/process (Kwon Citation2004).

Additionally, post-industrial theorists focus on the trends of deformation and non-materialization of the material world by electronic media. Virtual experiences through the media and simulation deprives the experience of tactile integration from phenomenological bodies. Simulacre, as a reproduction, is not a real experience and questions the authenticity of the place (Baudrillard Citation1992).

Such critical responses to the loss of the place of modernism seem to emphasize the focus on ideological places and their de-materialization. At the same time, however, values such as originality and authorship strayed from the object and leaned toward the location. Although recent place-oriented works may seem to have lost the material basis of the place due to trends such as emphasis on events and performances, and de-objectifying and de-spacing, artworks always seem to be combined with the exhibition site. In addition, the concept of the event as a regenerative action of the place itself and a resistance to the already established order defines the understanding of the modern place.

3. Pavilion: from shelter to events

3.1. Temporary but original: shelter or shrine

The word “pavilion” originates from the French archaic word pavellun, derived from the Latin word papilio, which means butterfly. It refers to the temporary nature of tent structures presented as moving, extraordinary, thin, and light images resembling butterflies.

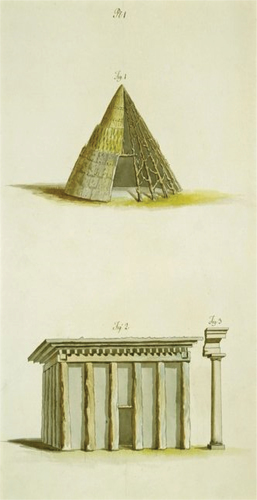

Pavilion in architecture is commonly considered as a “lightweight and largely open structure dedicated to a single purpose” (Samson Citation2016) and refers to a shelter in a garden or an exhibit hall. In addition, it is a free-standing unit exposed in all directions and expresses “the idea of architectural shelter.” Marc-Antoine Laugier (Citation2009) proposed a single-cell type of shelter, “primitive hut”, constructed with natural objects to explain the fundamental elements of architecture.

The idea of primitive hut as a shelter for humans unprotected from nature emphasized the rooted construction based on the tectonics of the pillars and beams anchored on the ground as the origin of architecture; but in fact, such structures intended to function as roofs and walls across the fabric as a barrier between nature and human bodies. Fundamentally, fabricated tents indicated that the dwelling was to cover the exposed body. The tent was originally a form of construction for nomadic dwelling. After humans adopted a lifestyle of settlement, it provided temporary living quarters for trade and transport. As such, “place of dwelling,” which encompass settlement and wandering, were divided into two constructive forms. One was the mass of masonry construction and the bond between the foundation and the ground to support it, and the other was the fabrication of the bough and cloth. Settlement is a vertical force perpendicular to the ground, and mobility is a lateral force drifting the surface of the ground.

The tent also enables reconciliation and coexistence with nature. A garden is known as a combination of the Hebrew gan, which means “fence,” and Oden, which means “joy.” The etymology of garden means the humanization of nature and the experience of joy felt there. The ancient garden was a place of leisure for contemplation, relaxation, and hunting, as well as a venue for events for the display of power. Persia’s gardens were intended to be a “paradise” that did not just lock nature up and domesticate it, but an area in which humans could unite in complete reconciliation with nature. The paradise was square, and the crossroads divided the place into four; the pavilion was at the center as a temporary human residence (Farahani, Motamed, and Jamei Citation2016).

Persians referred to the king’s tent as “heaven” and re-painted the sky on the inside of the roof walls. The desire to humanize nature through artistic activities that “re-enact” the dual attitude toward it on the surface of the architecture emerged. The garden, as cultivated nature surrounded by fences, is a humanized outer world, and the pavilion in it is an artifact representing humanized dwelling in preparation for nature, not an area for daily residence. As such, the pavilion in the garden is a constructive extension and establishment of its meaning. The symbolic aspects of the pavilion were inherited through aedicula and ciborium. Both were small temples in the form of canopy, but if the aedicula was a way to express the “the human action that protects and celebrates that which is lawful and civilized, despite its closeness to the void outside,” (Samson Citation2016) the ciborium was a small pavilion inside a church, containing the meaning of the divine world in the order of the civilized shrine. In each case, the pavilion was the establishment of human positions and territories within the shrine as a reductive Nature, either as a garden or as a divine threshold. As a single free-standing shelter, the pavilion expresses the original constructive principle of architecture and as a temporary shelter in a garden, it plays the symbolic role of expressing the twofold perceptions toward nature.

3.2. Pavilion in landscape garden: folly for pleasure

The pavilion in the garden served as a reduced version of the original form of sacred and institutional things, as well as a place of pleasure to express individuals’ desires. This stems from the fact that the pavilion is a temporary residence in a non-routine and nomadic place. Folly, referring to a whimsical structure, is a homophone to folie, which means madness, and it has a dual meaning. Similar to the meaning of the word, the folly of the garden took a free form away from institutional style and formalism. If the pavilion functioned as an official resting place for the garden, the folly served as one of the elements or decorations of the landscape. It was also a device that provided an element of surprise and eccentricity, rather than a feature that completes the entire scene. Therefore, people wandering in the garden were temporary residents in the pavilion, but became travelers looking for non-routine enjoyment when walking between the follies. The folly, which was inside the mansions of the nobility for private pleasure, emerged as an important formal element in the picturesque garden, which became common in England in the 18th century. As an important aesthetic object to complete the landscape of the picturesque garden, the fabrique followed the stylistic standards of the external decoration of the folly and the reductive structure of the pavilion (Symes Citation2014). The exterior followed the norms of the classical style, but the scale was reduced to an uninhabitable level and had no interior space. It was an important object to complete a single idealized landscape of arcadia, along with camouflaged boundaries and calculated locations to “appear natural.” The stylistic facade completing the arcadia represented an ideal place, but only worked as an ideological image, depriving it of residence. However, fabrique is an important exhibition to realize a picturesque garden with nature being an integrated ideal. The position and external appearance are most important in the overall placement of the garden. Therefore, the key elements for the pavilion were its location and appearance within the entire layout of the garden. The epidermatic display for visual delight made those walking in the garden travelers rather than residents. This helped to make walking in public space an important social rite. The disappearance of “gan” from the picturesque garden is not irrelevant. The spatial relationship that distinguished it from nature was concealed and reduced to a subject only with the epidermis for visual enjoyment. Along with this, the important symbolic function of the pavilion – the expression of dual emotions of the hidden gods in nature and the desire for nature – also disappeared, and the characteristics of the formalistic transformation for the epidermatic style dominated the architecture of a pavilion.

3.3. Follies for events

The interior space of the pavilion, removed from the fabrique, was recovered in the follies at Parc de la Villette. Bernard Tschumi, who designed its master plan, brought back the pavilion as a place of action through follies. At the time, the pavilion was the physical equivalent of the deconstructivist spirit of the time, replacing the meaning of the power and paradise of the pre-modern pavilion with modern thought. Folly is a spatial version of the discourse of deconstructivism of Bernard Tschumi and Jacques Derrida. At that time, Tschumi viewed that the primary issue of modern urban planning was the return of activity and program as “functions” because architectural ideologies of previous eras served to stabilize society and perpetuate the system. He also focused on the problem of capturing human dynamic and unpredictable movements in urban architectural space. Architecture is not just a space and form, but an event and action that takes place in a space. He argued that the architectural space should be transformed into a field where conflicts, disjunction, and dismantlement of programs occur, and coincidental events are triggered anew. This resulted in the denunciation of classical norms and a deconstructionist platform of autonomous combinations of reduced geometric elements. Tschumi’s follies were shown as a constructive play in which basic geometric elements such as dots, lines, and planes were autonomously combined in grid systems. The simplest reduced geometrical elements are considered as neutral form factors that do not enforce any social norms. It is assumed that the void space between the form factors functions as an open field for activity. If a fixed and traditional place was leaning on a solid boundary reminiscent of a thick fabrication and the resulting stark sense of boundary, the place of activity and event appeared to be a neutral empty space created between autonomous geometric elements devoid of meaning. Neutral form factors are generated by morphological variations and should not contain symbolic meaning; only the play activity of people should produce temporary meaning. The movement of people is what is important, and the advent of an event means that various movements invade the architectural space (Tschumi 1981). Derrida, in particular, defined an event as the “establishment of a place to live” and evoked Heidegger’s notion that building is the act of forming a dwelling itself. Therefore, the provision of the shape of a void where an event can take place becomes the sole responsibility of architecture, and the place of dwelling becomes the place of the event. The pavilion, like follies, became a sort of a stage and a field that encompassed the scenes of events where various acts of movement took place.

3.4. Rootless Pavilion

The desire for architecturalization of the sensitivity of art of movements is the main motivation for modern architecture. As an ideal pavilion, Ledoux’s “House of Gardener Project in the Town of Chaux”, according to Sedlmayr, was the starting point of denying “something constructive”(Sedlmayr Citation1957). Avant-gardist El Lissitzky proposed that it was the vision for the future to overcome the base tied to the lands and experimented with the vision in Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House. Named on the basis of “Dynamic + Maximum + Tension,” it was inspired by “Ger” from Mongolia, which is a traditional residence of the nomads as a mobile architecture.

A single foundation like a tent is built with the weight supported with tensile force toward the single central mast. Fuller attempted to provide “a sustainable autonomous single-family dwelling, the living machine of the future” for nomadic residence suitable to the mobile technology and mass productions of machinery in the modern age. A radical example of a mobile machine for residence is “Cushicle and Suitaloon” by Michael Webb, who proposed the “Dwelling Capsule Concept” (). People practice “minimal residence” by wearing an inflatable tent and relying on a cushicle machine that aids movement. By getting rid of all elements of material construction of architecture of the past, it shows that the ensemble of “body-cloth-machine” is the original element of nomadic residency.

While they presented a single structure restored with minimal clothes and mobility machine as an architecture for nomadic dwelling, “Concert Hall Project Montage” by Mies van der Rohe (1942) presented the sensitivity of mobility with an abstract structure by inserting weightless (or rootless) wall-plane within a broad space of machinery image. It looked as if it was floating without supporting the roof formed with the then-modish technology of the space frame, and the wall at the boarder defining the broad space was removed, such that the space became a field extending without limit. By turning and juxtaposing the wall and roof, which are the basic constitutive elements of architecture, into an abstract plane that is flat and expanding, it reflects the reality of mechanical residence in the modern era and idealism toward taking off the lands.

As such, the architectural experiments that pursue an anti-gravitational form reflecting the changing reality of residence driven by the amplified mobility have weakened the concept of “the authenticity of a space that is unique and fixed” based on the binding relationship with the lands.

3.5. Serpentine Pavilion project as a “site-specific” work

Several authors who believed that the restoration of the uniqueness and individuality of space was a cure for modern diseases tended to highlight only the work operating in this particular space. Site-specific works are an attempt to reclaim lost individuality and uniqueness from the site and place, viewing modern homogenized and universalized places as the causes of the failure of modernist art. In response to the fact that modernist architecture and artwork pursued a movable object of autonomy in tabula rasa, it set the establishment of an inseparable relationship between work and place as its top priority. Thus, an object or event is not perceived as a visual manifestation through the eyes separated from the body, but rather as something that is being experienced “now, here” by the subject and through the user’s physical sight and re-evokes the place.

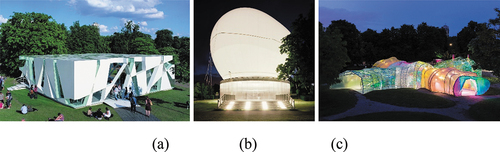

The Serpentine Gallery’s Pavilion Project (2000~) is an example of a temporary exhibition at the extension of “site-specific art” (). This is an event-type exhibition that operates temporarily by condensing the architectural philosophy of the architect selected by the gallery every summer in the garden of Serpentine Gallery in Hyde Park. Through the project, the Serpentine Gallery extends outside the white cube, making the pavilion an event-like object in the gallery garden and a folly. The gallery hosts a summer night event set in the pavilion every year. Through this, the museum is expanded into a garden of the public, simultaneously functioning as a forum where it can meet the public without boundaries and transform into a social place. In 2006, the pavilion’s designer Rem Koolhaas emphasized the social aspects of the project, describing it as “proposing a place that facilitates the inclusion of individuals in communal dialogue and shared experience” (Jodidio, Köper, and Bosser Citation2011).

Table 1. The Serpentine gallery’s Pavilion project.

The architects who participated in the Serpentine Pavilion Project questioned the philosophical, political, and ecological challenges facing architecture today, “arguing against ideas of sign, symbol or irony, bringing about notions of tactility, materiality, tectonics, and authenticity.” (Patteeuw and Szacka Citation2019). Tactility and materiality are based on a phenomenological understanding of space, which emphasizes the physical and sensational perception of a space called a “sense of place.” For an architectural structure to touch people’s hearts, materiality must be

emphasized since it must be able to trigger tactile sensations appealing to common memory and atmosphere. This is an important part of architectural resistance proposed by Frampton, stressing the tactility and indigenous materials and the tectonic aspect to restore the regional cultures that have been dominated by the universal civilization of modernity. The practical form of “placelessness” from the perspective of architectural autonomy is the purely technical structure that is distinct from the tectonic aspect of a structure. Architectural structural elements, in essence, according to Frampton, are the “act of transforming architectural actions into artistic practices.” That is equivalent to an emphasis on tactile elements of a structure. Furthermore, Juhani Pallasmaa said that “the materials from the nature (stone, brick, tree) allow our perspectives to pierce into their surface and to trust their authenticity,” (Pallasmaa Citation2012) and argued that tactility comes from the depth of time one has penetrated into the superficial features.

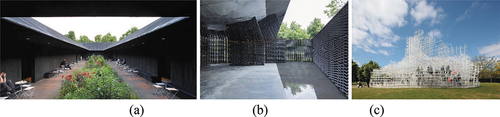

Within the Serpentine Project, the theme of which is tactility, notable works include Zumthor (2011) and Escobedo’s (2018) pavilion, which emphasize the atmosphere through proximity to the architecture’s surface and tactile experience, and Fujimoto’s (2013) work, which expresses the ephemeral contemporary phenomena through the tectonic of thin white steel pipes by presenting structures that permeate the surrounding landscape ().

Figure 2. Serpentine Gallery Pavilion as a tectonic notion (a) Zumthor (2011); (b) Escobedo (2018); (c) Fujimoto (2013).

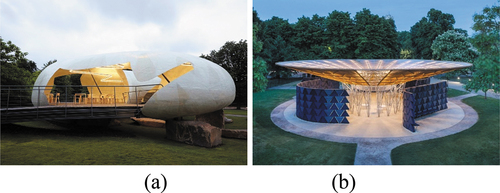

Additionally, works by Radić (2014) and Kéré (2017) that apply the local characteristics of the materials and construction techniques can be understood based on “Critical Regionalism,” (Frampton 1983), which combines universal modern technology with local culture (including geographical characteristics) as an architectural strategy for the same problem consciousness (). Examples, unlike the characteristics of the pavilion, that uniquely do not have a deep foundation on the site, provide a cavernous space by offering a surrounding interior space through site cultivation, in contrast to primitive huts and are also seen as practices of resistance against the placelessness. Zumthor’s (2011) pavilion is particularly interesting (), with its columnless structure and layout reminiscent of the inner courtyard of medieval monasteries and black timber wall’s coordination, which resists against the fact that modern architecture has devoted itself to transparency and provides a cavernous space deconstructing the Greek order or primitive hut (Mallinson Citation2011).

Figure 3. Serpentine gallery Pavilion as a combination of tectonic and representation (a) Radić (2014); (b) Kéré (2017).

Meanwhile, it is an important task of Serpentine Pavilion Project to present new sociality and an architecture form suitable thereto.

These are projects that provide a model of modern technological construction through the experiments of Libeskind’s (2001) deconstructivism autonomy, the new morphology shown by pavilions by Hadid (2000), Ito (2002), and SANNA (2009) of an atypical single roof, and the plan to induce Eliason and Thorsen’s (2007) movement; they offer the architect’s iconic style in a sculpting manner ().

Figure 4. Serpentine Pavilions as an imagery reproduction (a) Libeskind (2001); (b) Zaha Hadid (2000); (c) Toyo Ito (2002); (d) SANAA (2009); (e) Eliason & Thorsen (2007).

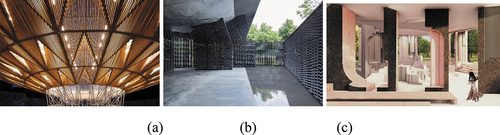

The works by Kéré (2017), Escobedo (2018), and Counterspace (2020) presented rain-collecting roof structures, local material textures, and unique construction methods, aiming to provide a place for discourse for social problems and debate under the ecological and cultural conditions of each region (). This is an approach that emphasizes the fundamental idea of the Serpentine Project, which aims to expand the museum to the outside world and society by providing a place for “social discourse” and “temporary events.”

Meanwhile, like Suitaloon by Webb, which expresses the sensitivity of nomadic residence, an emphasis on the curtain and surface surrounding the body of a structure has been displayed in the Serpentine Project.

Figure 5. Serpentine gallery Pavilion as a place for discourse for social problems (a) Kéré (2017); (b) Escobedo (2018); (c) Counterspace (2020).

Ito (2002), OMA (2006), and SelgasCano’s (2015) pavilion is the outermost edge and external surface of the inner volume, being an exoskeleton that combines a skeleton devoid of an external surface of the tectonic and the masonry’s wall that provides the boundary between the interior and the exterior (). The interior space is expanded to transform into volumes and outer layers like “inflatable Suitaloon.” It is reminiscent of Mies van der Rohe’s 50 × 50 House, which pushed the column to the surface, flattening the distinction between the roof–column–ground, and delivered the impossibility of dwelling (Hartoonian and Frampton Citation1994).

Figure 6. Serpentine Pavilions as an emphasis on the curtain and surface surrounding the body of a structure (a) Ito (2002); (b) OMA (2006); (c) SelgasCano (2015).

These works are related to site-specific art, which transform the place into concepts of audience, social issues, and community. Now, what is specific is not the physical conditions of the place, but the issues that the people who occupy it are interested in. In addition, a series of works to revive the characteristics of the place through the relationship between artworks and the place have become one-off events that cannot be reproduced as they are implemented into a procedural performance.

However, unlike Tschumi’s follies, which act as a venue for routine events, the Serpentine Pavilion is placed in a special context that is not routine as a work that has been given authenticity by the gallery authority. It is a pavilion with an interior space that serves as a venue for events in the park for a certain period, as well as an exhibit of the museum space, including the garden, as a recognized work of art.

This is in line with the phenomenon indicated by Kwon (Citation2004) in which authorship replaces authenticity. When works that are meaningful only in certain places are (re-) installed and (re-) displayed in other exhibitions, place-boundedness is replaced through the author’s “presence.” Therefore, authorship guarantees the quality of the work, and such authorship is established by the authority that accredits it. Serpentine Gallery, through its own authority, places architects on the ranks of artists and star architects, contributing to the brandification of architecture.

In the modern world, in which the process of a product losing its location is referred to as commercialization, the product type is a medium that conveys the essence of the object(Foster Citation1993), and the product becomes one only when it is a symbol(Lefebvre Citation2005). In other words, objects that are devoid of its location become symbols, and symbols, in place of the location, provide a visual and textual experience. The cultural power of a specific location and the artistic authority of the gallery, in this case, the extended gallery area of the Kensington Garden, provides the one-off pavilion its own identity and authorization, making it the gallery’s icon or the architect’s symbol. The pavilion after having been temporarily used as a stage where social programs operate, will then be recorded via texted records in books, articles, and works by artists. The objects built on the site are replaced every year, but the memory of having been a field for works and events is carved into the place. Thus, the repetitive one-off characteristic of events shown in this project is combined with identity and authorship to produce a new authentic placeness that supplants the concept of a place of permanence.

4. Discussion

The pavilion is a place for temporary dwelling, but it has been constructed as a primitive building type, tent, or conical and cubic form, to symbolize the human domain of nature. Samson (2015), citing Colin Rowe, said that “the pavilion as architecture here appears, in its archetypal Western realization, as a repertoire of normative elements” and that “conceptually a pavilion and usually a single volume, it aspires to a rigorous symmetry of exterior and (where possible) exterior.” In addition to the pavilion in the garden, the aedicula and the ciborium, which reproduced the “Holy of Holies” inside the cathedral, took a primitive form consisting of pillars and roofs. As a symbolic place for the human domain in nature, the primitive form was effective in revealing only the duality of hope and concealment of the sky beyond human reach. ()

Figure 7. The origins of buildings and orders.” Sir William Chambers (1722–1796). Primitive buildings of conical and cubic form c.1757.

However, the pavilion of the picturesque garden was an ornamental sculpture that did not express mankind’s mind to nature through architectural constructiveness, but presented a kind of visual norm for the appearance and placement of buildings within nature.

Nevertheless, the pavilion’s characteristic of symmetrical single volume has the advantage of being able to access and view it from four directions, making it suitable for the role of symbolic structures containing specific thoughts. For this reason, the pavilion was built in expo, the arena of national competition, to express national symbols. Likewise, it has been treated as a piece of sculpture symbolizing the typology of modern architecture.

Tschumi’s folly was shown as a tangled structure of place and field and as an actor and its receptor through an autonomous combination of geometrically reduced points, lines, and plane elements. Fragmented or sloping constructors free from gravity make the whole folly look more like a sculpture of composition than a tectonic. As such, the pavilion has two aspects of architecture, tectonic and representation, which are characterized by a weak physical bond with the site and an imagery reproduction to the construction techniques, depending on the temporality of events.

For architecture to embrace the new social identity as a space for actions and events, the geometrical autonomy of an object, as the nature of a pavilion, must be neutral with respect to meaning and symbol. As such, a pavilion has played the role of symbolizing the ideal nature, modernity, and new social identity. The symbolic role of a pavilion has been effective as an autonomous free-standing structure based on a loosely binding relationship with lands and a one-off temporary structure that can be approached experimentally.

As such, the construction and the surface of the pavilion that expressed the dual perception of nature and architectural principles of primitive construction gradually weakened its constructivism, and its symbolic surface has been increasingly emphasized. In the modern era, it was a condensed manifestation of new society and technology, thereby earning a new view of constructivism and the surface. The Serpentine Pavilion project shows that reflective attitudes toward modernism after the 1950s and the 1960s have evolved to emphasize time, programs, and events, or to explore locality, the site and material properties as an autonomous combination of geometric fundamentals, or to reject symbolic descriptions and to reveal the material and tectonic configuration itself.

5. Conclusion

As such, the pavilion is an architectural response to modern, mobile culture, replacing the transition from permanency to events oriented on temporality, the coexistence of epidermality and tactical materiality, and site-specificity with branding authorship.

A place represents an integration of production and being by establishing a place of dwelling through things and positioning it in the world. The place of this dwelling takes root on the site and acquires a permanent physical bond with the world. In contrast, the life of wandering and nomads is different in that it is ephemeral in terms of the depth and time of rooting-down. The rooted place of domiciliation is represented through the masonry construction of heavy stones, but nomads built a tent structure by setting branches and hanging fabric. Moreover, the place of settlement was a material expression of institutional perpetuation such as religious and political power, while the place of wandering and deviation was temporarily installed outside the castle or built in a secret form inside the garden. Such pavilions were treated as an imagery reproduction of a stylized institutional place. The king’s tent with the heaven drawn into it or the fabrique reflect such characteristics. The epidermic surface of the fabrique is the result of the evolution of the “tourist gaze,” (Crang Citation2016) which converts the material and spatial quality of the place associated with the site into a visual object or image.

However, the pavilion as free-standing shell or frame around a place reduced the building program into artistic features playing the role of a model that revealed the architecture’s archetype.

This characteristic was the main reason why the exhibition hall, an event space for showcasing symbols of the new era, was commonly referred to as the “Pavilion.” Only at the fair, the pavilion not only plays a symbolic role in the institutional spatial style that the former site of the settlement contained, but also has been given the function of a place to promote and convey social values.

Today, the modern pavilion serves as a model for reducing contemporary agendas of architecture, while also being a venue for site-specific art events to accommodate social programs. As a symbolic building that will serve as a venue for social exchange and public debate, the Serpentine Pavilion has been placed in the ranks of an artwork through the authorship given by the identity of star architects and the gallery – and the site-specificity.

Such site-specific art emphasizes the location and materiality of the site as a basis for recovering identity and univocity believed to have been lost during modern times. The common purpose of site-specific works was to discover the meaning of differences and uniqueness in places. However, as the number of touring exhibitions that leaned on the author’s identity gradually increased, the authority of the gallery replaced the specificity of the site, and the time-ness of the change acquired through the bond with the place transformed into qualities such as temporality and repeatability of the event. It is interesting that the discourse on site-specificity that emerged with the fear from the fact that the originality of the work lies in the aura fixated in the uniqueness of the place, and the power of modernity lies in the loss of the aura, invoking a placelessness was reproduced centered on “events and performances” that emphasize the place. Its reproductions were characteristic in that they could not be repeated to revoke the uniqueness of that place. The traditional place-boundness, in which aura and uniqueness are carved into the site and things through constant repetition, was to ironically return through its characteristic of being non-repeatable. This seems to be an effort to overcome the present-day crisis of representation (Kaminer Citation2011) (Vesely Citation2004) through the emphasis on authorship and the repetition of events.

The reality that the pavilion is operating as a popular place and as an artwork reveals the decline in its architectural role as a historical monument, both as a social institution and as a cultural symbol. The monuments placed in the community’s spatial environment constantly expose and evoke the events that need to be preserved and delivered to the community members. The monument is not originally intended for dwelling but is an object that functions symbolically.

The construction of the monument is a collective proposition, with the festive nature of poiesis or “building.” The monument appears to be on the opposite side of the “place of dwelling,” given that it excludes residence and has a propositional non-routine nature. However, it has been considered a typical “place of permanence” because the purpose of the monument is ultimately to equalize and perpetuate the collective values of the community.

Concerned about the loss of modern monumentality, Sert, Léger, and Giedion (Citation1958) emphasized the importance of the role of monumentality in the new society, saying that “monuments … have to satisfy the eternal demand of the people for translation of their collective force into symbols.” Art historian Riegl (Citation1982) mentioned the nature and status of monuments that have changed in the modern era and argued that the new unintentional monuments have emerged in addition to the “intentional monuments” from the past. The nature of modernity, which pursues newness and changes, has ironically given rise to the worship of things from the past that have disappeared, pursuing symbolism by granting aura to historical objects or adding a historical image to newly emerged objects.

Unlike the past, the modern era featured monuments honoring the historical traces of old objects, and objects of history in the museum were considered to have an aura. An old object that came from a place of things belonged to an institutionalized one like gallery or museum, and it was recognized for its aura and originality. In other words, the intangible system of empowering things and its space has replaced the traditional place.

The pavilion, thereby, is a model of “place” for modern people. It emphasizes its temporality in the aspect of time, focuses on new morphological construction and phenomenological materiality in the aspect of tectonic, and acts as a field of discourse and event where individual-anonymous socialities intersect. As a material and spatial alternative to such placeness, the pavilion can be considered an important type of architecture.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hyejin Jung

Hyejin, Jung., Ph.D., Assist. Prof., Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Inha University, Incheon, South Korea. Her research interests concern the architectural and urban design, spatial characteristics, and theory of placeness.

Soram Park

Soram Park., Ph.D., Visit.Prof., Division of Architecture, Myongji University, Yongin, Republic of Korea. Her research focuses on theory/history and its interrelationship with architectural and urban design.

References

- Baudrillard, J. 1992. Simulation. Translated by T. Ha. Seoul: Mineumsa. (Original work published in 1981).

- Crang, M. 2016. “Tourist: Moving Places, Becoming Tourist, Becoming Ethnographer.” In Geographies of Mobilities: Practices, Spaces, Subjects, 205–224. London: Routledge.

- Cresswell, T. 2013. Place: A Short Introduction, 3–4. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Dal Co, F. 1990. Figures of Architecture and Thought: German Architectural Culture 1880–1920, 19. New York: Rizzoli.

- Derrida, J. 1986. “Interview with Eva Meyer.” DOMUS 671: 17–24.

- Dodds, G. 2005. Building Desire: On the Barcelona Pavilion. London: Routledge.

- Farahani, L. M., B. Motamed, and E. Jamei. 2016. “Persian Gardens: Meanings, Symbolism, and Design.” Landscape Online 46: 1–19. doi:10.3097/LO.201646.

- Foster, H. 1993. The Anti-aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Translated by H. Yoon, 206. Seoul: Hyun-dai Mihaksa. (Original work published in 1983).

- Frampton, K., Futagawa, Y. 1983 Modern Architecture, 1851-1945 (New York: Rizzoli)

- Giedion, S. 2009. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition. 5th ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hartoonian, G., and K. Frampton. 1994. Ontology of Construction: On Nihilism of Technology in Theories of Modern Architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heidegger, M. 1971. Building Dwelling Thinking. Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by H. Albert, 145–160. New York: Harper Colophon.

- Heidegger, M. 2000. Elucidations of Hölderlin’s Poetry (EHP). Translated by H. Keith. Amherst: Humanity Books.

- Jodidio, P., K. Köper, and J. Bosser. 2011. Serpentine Gallery Pavilions. Cologne: Taschen.

- Kaminer, T. 2011. Architecture, Crisis and Resuscitation: The Reproduction of post-Fordism in Late-twentieth-century Architecture. London: Routledge.

- Kwon, M. 2004. One Place after Another: Site-specific Art and Locational Identity, 27–39. Cambridge: MIT press.

- Laugier, M. A. 2009. An Essay on Architecture. Translated by W. Herrmann, 36–38. Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls, . Translated by W. Herrmann.

- Lefebvre, H. 2005. Everyday Life in the Modern World. Translated by J. Park, 179. Seoul: Giparang. (Original work published in 2000).

- Mallinson, H. 2011. “Zumthor’s Hairy Paradise.” Architectural Research Quarterly 15 (4): 304–308. doi:10.1017/S1359135512000061.

- Massey, D. 1994. A Global Sense of Place. Space, Place, and Gender, 152. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Miller, M. H. 2013, April 24. “Gallery? What Gallery? Robert Barry Masterpiece Reprised in New York.” Observer. https://observer.com/2011/07/gallery-what-gallery-robert-barry-masterpiece-reprised-in-new-york/

- Norberg Schulz, C. 2019 Genius loci: towards a phenomenology of architecture (1979) Cody, J., and Siravo, F. Historic Cities: Issues in Urban Conservation (Los Angeles: Getty Publication)

- Pallasmaa, J. 2012. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Patteeuw, V., and L. C. Szacka. 2019. “Critical Regionalism for Our Time.” Architectural Review 245 (1466): 92–99.

- Relph, E. 1976. Place and Placelessness. Vol. 67. London: Pion.

- Riegl, A. 1982. “The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin.” Oppositions 25 , (1): 20–51.

- Rubio, I. S. 2004. Differences: Topographies of Contemporary Architecture. Translated by J. Lee, 162. Seoul: Sigond Munhwasa. (Original work published in 1997).

- , and S. Giedion. 1958 Nine Points on Monumentality 1943 . “.” Architecture You and Me (London: Oxford University Press) 48–51.

- Samson, M. D. 2016. Hut Pavilion Shrine: Architectural Archetypes in Mid-Century Modernism. London: Routledge.

- Sedlmayr, H. 1957. Art in Crisis: The Lost Centre. Translated by J. Lee and Brian Battershaw. London: Hollis and Carter .

- Symes, M. 2014. “The Concept of the “Fabrique”.” Garden History 42 (1): 120–127. Accessed 5 January 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24636290

- Tuan, Y. 1974. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes and Values. Newyork: Columbia University Press.

- Vesely, D. 2004. Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation: The Question of Creativity in the Shadow of Production. Cambridge: MIT Press.