ABSTRACT

Providing calming environments for children with autism spectrum disorders in schools is a common issue in the world as the unique cultures and characteristics of autistic individuals are increasingly revealed. However, in Japan, no architectural guidelines provide specific information to develop autistic friendly spaces in special schools. Consequently, the provision of “therapeutic” spaces such as calm rooms, soft play rooms, sensory rooms or terraces is lagging behind. We conducted field surveys at six special schools in the UK as model cases. We analysed: 1) the types and functions of therapeutic spaces, and 2) the configuration of therapeutic spaces around a classroom. As a result, we identified the spatial organisation of therapeutic spaces based on a classroom suitable for different age groups. In nursery areas, dedicated playgrounds with direct access from classrooms are in high demand. In primary areas, small terraces next to classrooms and calm rooms nearby play a role in maintaining the children’s well-being. In secondary or high school areas, the settings are becoming more similar to mainstream than to special schools as the students become more independent. These findings suggest the importance of supporting individuals and different age groups through the spatial organisation of therapeutic spaces.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Creating calming environments is an important issue for children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) who are sensitive to their physical surroundings. The purpose of this study is to present how to organise therapeutic spaces in special schools where children with ASD feel calm and comfortable so that they can manage their difficulties in their school life. This paper focuses on Japan and other countries which are struggling with planning special schools by analysing case studies in the UK.

1.1. Special schools in Japan

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, adopted by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in December 2006, had 182 ratifications/accessions and 164 signatories as of October 2020, and the environment for individuals with disabilities has been universally recognized as something that needs to be improved (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2021). Japan signed the Convention in September 2007 and ratified it in 2014, and additional laws and systems based on the principles of normalization and inclusion were developed during this time. There have been various developments in special education, however, regarding facilities in special schools, there are still issues to be addressed. In particular, education for children with intellectual disabilities and autism has a shorter history than other types of disabilities such as hearing and visual impairments or physical disability in Japan. Hence, clear ways to deal with the problems and necessary architectural elements have not been formulated (Ueno and Nakajima Citation2012). Teachers often use cardboards as partitions to make personal spaces for children to do individual work, change and cool down (Imabayashi et al. Citation2012). According to a questionnaire survey to teachers in 725 special schools across Japan conducted by Koga et al. in 2011, cool down spaces and sensory rooms were requested (Koga, Hori, and Yamada Citation2017). These reports indicate a lack of space for children to calm themselves in special schools in Japan. While Japanese special schools have a tenuous relationship between classrooms and other spaces, the National Kurihama School for handicapped children is thought-provoking. This is due to its plan to form units for each year group. A unit consists of three learning spaces, a teachers’ room, a storage, two toilet booths and a playground. The designer conducted research on how the spaces are used and concluded that it is imperative to make the character of the spaces clearer (Sekizawa Citation1998).

In summary, the spatial issues for special schools in Japan lie in securing spaces for intellectual disabilities and autistic children. They might need spaces to calm themselves and clear structure of the spaces based on their classrooms.

1.2. Relationships between the UK and Japan

The UK was chosen as a model country to analyse special school facilities. The European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education compares policies and practices towards the inclusion of pupils with special educational needs in the EU and the candidate countries (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education Citation2003). It shows three categories: a one-track approach; a multi-track approach; and a two-track approach. The UK and Japan both belong to the multi-track approach category. They commonly offer a variety of services between mainstream and special needs education systems, which means that special schools in both Japan and the UK should provide specialist facilities for each specific disability.

The UK government has a continuing commitment to improving school buildings. Building Bulletin 102 (Department for children, schools and families Citation2008) and Building Bulletin 104 (Department for Education Citation2015) set out non-statutory guidance on the planning and designing of schools for disabled children and those with special educational needs. Building Bulletin 102 provides more visual aids and shows a framework for designing and building mainstream and special schools. The UK-wide programme, Building Schools for the Future (BSF), which dates from 2004 and has a substantial budget, led to improved situations in the schools that were more in need (Cardellino, Leiringer, and Clements-Croome Citation2009). The 10-point criteria produced by the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE), which was the UK government’s adviser on architecture, urban design and public spaces, also aided in the development of design quality (Chiles et al. Citation2015). Hence, the wealth of information available allows architects, schools, local authorities and other stakeholders involved in education provision to design better school facilities. Above all, it is thought that analysing case studies of special schools in the UK could reinforce design quality in Japan and other countries with poor guidelines.

1.3. Importance of focusing on ASD

Autism and intellectual disability are diagnosed separately, but the line between them is blurred (Sohn Citation2020). Many social communication deficits that define ASD would be expected to occur to some extent in all individuals with intellectual disability (Thurm et al. Citation2019). For these reasons, this study focuses on the characteristics of children with ASD and addresses the physical environments that affect them in special schools.

The National Autistic Society in the UK has listed the following difficulties that autistic people may share: social communication and social interaction challenges; repetitive and restrictive behaviour; over- or under-sensitivity to light, sound, taste or touch; highly focused interests or hobbies; extreme anxiety; and meltdowns and shutdowns. Furthermore, symptoms vary from mild to severe, and no two cases are alike. Because of the complexity, designing and crafting environments for ASD is challenging.

1.4. Definition of therapeutic spaces

Since Kanner (Citation1943) described a unique syndrome, “infantile autism,” in 11 children with autism, researchers have made significant contributions to reveal the characteristics and culture of ASD. A serious problem among children with autism may be a lack of interest and motivation in academics and learning (Gaines et al. Citation2016). Although many children with ASD exhibit disruptive behaviour when assignments are presented, incorporating specific motivational variables has been shown to lead to improvements in autism symptoms (Koegel, Singh, and Koegel Citation2010). Hence, learning environments for children with ASD should be carefully designed to accommodate their characteristics. In addition to a classroom having a sense of calm and order, additional areas for pupil personal spaces and an external secure play area should be considered in space allocations (McAllister Citation2010).

In this study, the term “therapeutic space” is used to refer to spaces that help children with ASD to remain calm, relax, regroup and regulate themselves. This study was carried out based on the belief that therapeutic spaces encourage children with ASD to work on academic tasks and manage their school life more independently.

Quiet and small spaces that reduce sensory overload are beneficial for helping children with autism to remain calm. On the other hand, sensory rooms that provide sensory inputs, developed by Hulsegge and Verheul (Citation1987) and known as Snoezelen, can allow children with ASD to feel comfortable and relaxed. In the 1970s, Ayres (Citation1972) noted that children with developmental disabilities, including autistic children, have difficulty processing sensory information, and thus developed sensory integration therapy, known as Ayres Sensory Integration, which involves physical activities (Lane et al. Citation2019). Trampolines and balance beams are commonly used for gross motor activities to develop coordination skills. In addition, performing the same action repeatedly is one of the characteristics of autistic children, and allowing them to do so is also a way of calming them down (Lovaas Citation1987). From the above, there are many ways to help children with ASD remain calm. Accordingly, special schools should have a variety of therapeutic spaces.

1.5. Objectives

The Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH) programme developed by Schopler in the 1970s is a series of intervention strategies that are linked to empirical findings about neuropsychological functioning in autism (Mesibov, Shea, and Schopler Citation2004). The theory of “organisation of the physical environment”, which indicates the division of space according to purpose, helps architects, educators and other stakeholders consider room allocations and zoning in special schools. When children can understand their environments, they feel safe and in control of the situation (Vogel Citation2008). Not only is it important to have a variety of therapeutic spaces, but also where to place them.

This study addresses therapeutic spaces in six special schools in the UK as model schools. The objective was to clarify the spatial organisation of therapeutic spaces. The following two major points were analysed. The first is the type and function of therapeutic spaces to understand which spaces can help children with autism remain calm. The second is the configuration of therapeutic spaces around a classroom to grasp how to structure these spaces on school premises. Diagrams showing the adjacency of therapeutic spaces to a classroom were illustrated by age group to highlight different solutions by structuring therapeutic spaces according to age group.

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of schools investigated

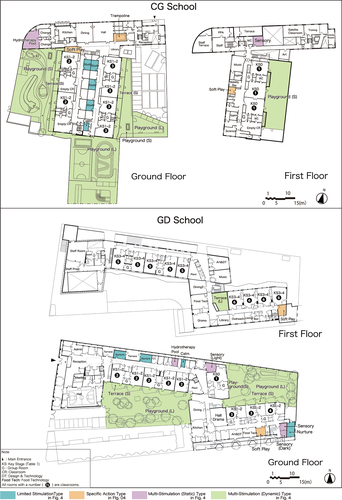

We selected six schools to investigate (). The schools investigated are located in either London or Hampshire, England. London is the capital of the UK and has the economic advantage of being a place where advanced examples can be gathered. Hampshire is about one fifth the size of London in terms of population, but the county council employs in-house architects and has been a leader in the design of advanced educational facilities in the country.

Table 1. Profiles of the schools investigated.

These schools were designed by architects who have a wealth of experience in designing school buildings and knowledge of special needs in regard to autism. We obtained this information from their award-winning works, as well from their works presented in Building Bulletin 102 (2008) or The Architects’ Journal, one of the biggest architectural magazines in the UK (Hawkins\Brown & The Architects’ Journal Citation2015). In addition, in Hampshire, we asked the Hampshire County Council Property Services to make the selection.

In England, the primary types of needs are divided into 12 categories (Department for Education Citation2018), but in many cases, classes in special schools are represented by either ASD or profound and multiple learning difficulties (PMLD) classes as ambulant or non-ambulant classes, respectively. All schools except for the GD school in provide education for children with both ASD and PMLD.

The ages of pupils ranged from 2 to 19 years. shows the education system in England. The standard size of a special school in England is around 100 pupils. The numbers of pupils in the schools investigated ranged from 62 to 197. The CG School listed in had not yet reached its capacity of 85 because it had just opened. The floor area ranged from 3,000 m2 to 4,900 m2.

Table 2. The education system in England.

2.2. Survey

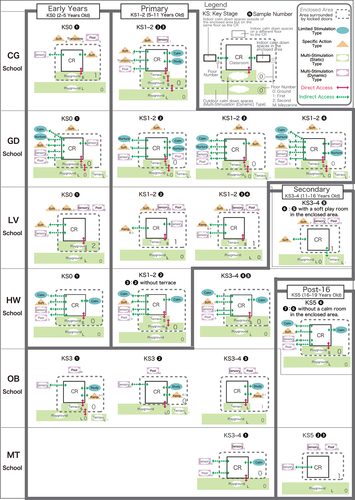

Seven investigators visited the six schools in March 2019 and spent 2 to 3 hours in each one to conduct interview surveys and a school tour. The floor plan of each school was obtained prior to the field survey, and structured survey sheets were prepared for each school to confirm the location of the classrooms and therapeutic spaces. Based on the survey sheets, we asked the principal and business manager at the site to show us around the school building to confirm the use of the spaces and the ages and characteristics of the children who would use them. For the CG, GD, HW and OB schools, the architects who designed the buildings accompanied us on the site visits, and for the LV school, we set up an interview with the architects in their studio on a separate day. For these five schools, we also listened to the intentions of the architects. Through these surveys, therapeutic spaces in the schools investigated were identified and the 71 classroom samples shown in were collected to illustrate adjacency diagrams and analyse spatial organisation of therapeutic spaces around a classroom.

Table 3. Classroom samples.

The research subjects of this study are spaces, not individuals. We conducted the field surveys with the teachers and staff members, who agreed to share the information they provided.

3. Types of therapeutic spaces

For children with ASD who are sensitive to their environment, maintaining a calm state is the first step in receiving education. To identify therapeutic spaces in the investigated schools, the teachers and staff members were interviewed to clarify the utilization of each space. This section is divided into three subsections: the first provides an overview of the school plans, the second explains the function of each therapeutic space, and the third explains how the therapeutic spaces are classified.

3.1. School plans

show the room names and floor plans of each school based on the results of the survey. The floor numbers vary from one to three storeys. The building shapes of the school investigated fall into three types: linear (the LV and OB schools), T-shape (the OG and HW schools) and zig-zag (the GD and MT schools). Their classroom spaces are grouped together according to age group (early years, primary, secondary and post-16). The boundary between the designated areas for each age group is formed by different floors, corridor branches or lockable doors in the corridors.

A typical class has six to 10 pupils. Children are organised into a class with friends who have similar or the same level of special needs.

Ground floor accommodation allows safe, level and easy access to the outdoors, which is especially important for younger children (Department for children, schools and families Citation2008). The basic idea is that the lower floor is for younger and the upper floor is for older classes. However, an exception is the class areas for early years in the CG and LV schools, which are located on the top floors. This idea comes from the fact that as soon as early years children move up to the classroom area in the morning, they seldom move to another floor compared with older children (according to the architects of the LV school). The designated playgrounds for early years are secured in the CG and LV schools by using the rooftops to compensate for the disadvantage of a lack of access to the ground floors.

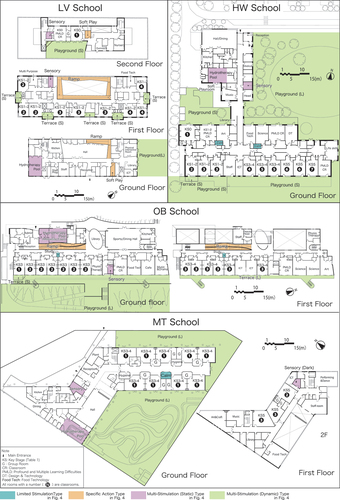

3.2. Functions of therapeutic spaces

Coloured spaces in indicate therapeutic spaces. explains the functions of therapeutic spaces with pictures taken by the investigators of the school surveys. In addition, shows the number and average floor area of each therapeutic space in the investigated schools.

Table 4. Number and area of therapeutic spaces in the schools investigated.

Calm rooms, nurture rooms and study rooms are all quiet spaces. All schools except for the LV school had at least one quiet space. The LV school does not have a particular quiet space, but the food technology and multi-purpose room were used as quiet spaces when some individuals wanted to be alone (according to the principal in the LV school).

Soft play rooms are designed for relatively young children. All schools that contain early years and primary schools (the CG, GD, LV and HW schools) had a soft play room.

Trampolines are an essential item for many autistic children, but they are usually installed at multiple locations in playgrounds or on terraces; they are rarely incorporated into rooms. Only the CG school had a trampoline room, which was installed at the request of the principal.

Ramps are useful for not only wheelchair users, but also autistic children by allowing them to walk slowly and calmly. Some schools choose not to install ramps for a variety of reasons, including insufficient space, budgetary restrictions, layout plans, the advantages of other spaces and the fact that lifts can be used for vertical movement. However, it is necessary to consider the fact that ramps can be a therapeutic space for autistic children.

Sensory rooms and hydrotherapy pools were located in all of the investigated schools, suggesting that they are highly popular. Each school usually has one or two sensory rooms and one hydrotherapy pool, and these are shared by the entire school or large groups. Each child receives special treatment about once a week, and a timetable for the use of each space is set up for individuals or a few children at a time.

Terraces and playgrounds are divided into (S) and (L) according to which groups use them. (S) is an external space adjacent to the classroom and dedicated to a specific class or group of classes, whereas (L) has a large area and is for all grades. The playground (L) is so vast that it is unclear how far it extends, so the area is not shown in . Terraces and playgrounds (S) can be at ground level or on the upper floor. Terraces (S) at ground level are enclosed by a fence and a door, and a playground is located beyond the fence. They could be a buffer zone between the inside and outside (according to the principals and architects of the GD and CG schools). Even a small terrace plays an important role as a recreation space where children can breathe fresh air, feel the natural light and use trampolines and other equipment for physical exercise (according to the principal and architects of the LV school).

Group rooms associated with classrooms are also used as therapeutic spaces. However, we have excluded these from therapeutic spaces in the analyses. Almost every classroom has a group room, or small room that can be used as a group room, which eliminates any differences between schools and age groups. In the same way, corridors were excluded in the analysis because they exist in all cases, even though they can also be the therapeutical spaces in which children can walk around slowly or stand still.

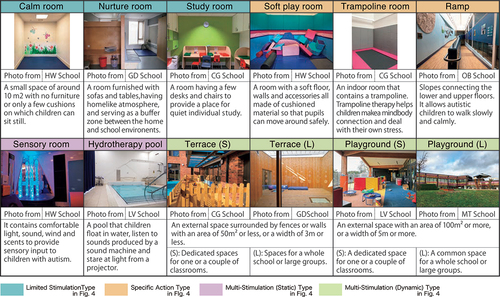

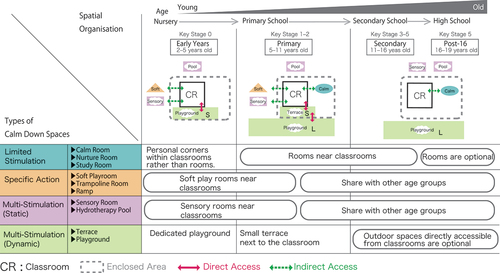

3.3. Classification of therapeutic spaces

As explained above, each therapeutic space has a specific function. It is important for autistic children to learn how to control their anxiety or tantrums, regulate their emotions and maintain their well-being, and therapeutic spaces help them to do so. While children with ASD over-react to some stimuli, they experience comfort and fun with particular stimuli. If they seek time alone and stillness when overwhelmed by their surroundings, they may engage in repetitive actions and gross motor activities to help regulate themselves. In other words, the following methods can help autistic children remain calm: 1) controlling incoming stimuli or providing pleasant stimuli, and 2) relieving anxiety by sitting still or releasing stress through movement. These conflicting aspects were discovered in therapeutic spaces in the schools investigated, which resulted in the classification as shown in Therapeutic spaces are characterized by two indications: whether the sensory stimulation is various or limited, and whether the behaviour is dynamic or static. Hence, therapeutic spaces can be divided into the following four types and described with a combination of the two indications.

(1) Limited stimulation type: Calm rooms, study rooms and nurture rooms fall into this category, where the sensory stimulation available is as limited as possible and the space is small and confined by walls. These are spaces where children can sit down and organise their feelings.

(2) Specific action type: Soft play rooms, trampoline rooms and ramps are spaces where children can attain a sense of calm by performing specific actions such as moving their bodies with soft objects, bouncing up and down and walking.

(3) Multi-stimulation (static) type: Sensory rooms and hydrotherapy pools are spaces where children can receive various types of comfortable sensory stimulation in a relaxed state without moving their bodies much.

(4) Multi-stimulation (dynamic) type: Terraces and playgrounds fall into this category. Outdoor environments provide natural sensory stimulation and allow children to participate in gross motor activities.

4. Spatial organisation of therapeutic spaces based on the classroom

When children feel uncomfortable staying in the classroom, they try to find a therapeutic space themselves or are encouraged by their teachers. The first choice might be a corner or tent inside the classroom, and the second might be a group room or an outdoor space adjacent to the classroom. If the children are still not ready to return to classroom activities, the third choice might be a calm room or a soft play room across the corridor (according to the architects of the LV school; the same thing was heard from the teachers at all schools). For this reason, the sequence of therapeutic spaces should be well considered. This section provides adjacency diagrams between a classroom and therapeutic spaces and clarifies their characteristics.

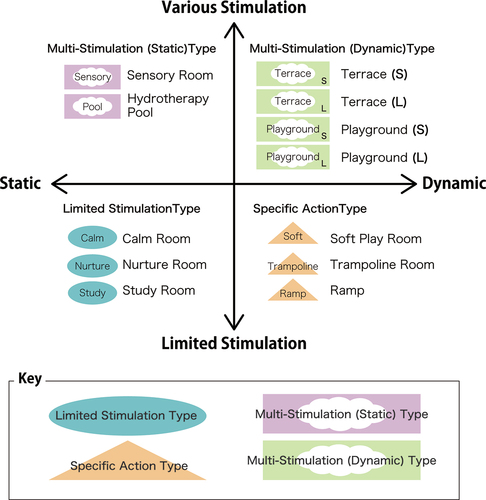

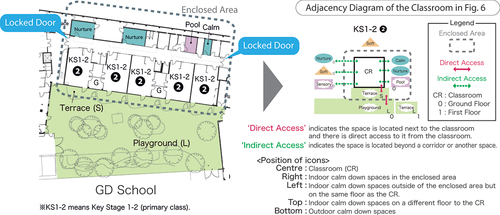

4.1. Methods for displaying adjacency diagrams

In the UK, special schools have lockable doors at some points in corridors to create designated areas for specific age groups, as shown in . The purpose of lockable doors is to identify an area within which children can move freely and to protect their safety. The term “enclosed area” used in this paper refers to the area enclosed by lockable doors. Therapeutic spaces in enclosed areas are relatively more accessible from the classroom, and even if a child needs to use a therapeutic space to relieve frustration during a class, he or she can return to the classroom relatively quickly to resume class activities. Given that children spend most of their time in classrooms, the accessibility of therapeutic spaces from the classroom is important. Accessibility from the classroom can describe whether the therapeutic space has direct access, whether it is located in the enclosed area or whether it is situated on the same floor.

To capture the location relationship between classrooms and therapeutic spaces, a diagram using the rules shown in was created as . Arrows indicate the connection between a classroom and a therapeutic space. Red solid lines mean “direct access,” which indicates that the therapeutic space is located next to the classroom and offers direct access from the classroom. The green dotted lines mean “indirect access,” which indicate that the therapeutic space is located beyond a corridor or another space. In an adjacency diagram, the classroom is drawn in the centre. The right side shows indoor therapeutic spaces in the enclosed area. The left side indicates other indoor therapeutic spaces on the same floor as the classroom. The top shows indoor therapeutic spaces on a different floor than the classroom. The bottom indicates outdoor therapeutic spaces.

4.2. Spatial organisation for each age group

The adjacency diagrams in are divided into four sections to compare the cases between the age groups: early years; primary; secondary; and post-16. shows a list of these adjacency diagrams. The differences between age groups can be described by the terrace (S)s, playground (S)s and limited stimulation types, which are likely to be used only by specific classes rather than the multi-stimulation (static) or specific action types, which are shared by the entire school or large groups. The characteristics of adjacencies for each age group are described below.

Table 5. List of adjacency diagrams.

(1) Early years: In all four early years schools, even in the CG and LV schools, where the classrooms are located on the upper floors, the playground (S) has direct access to the classroom. This strong connection between a playground (S) and a classroom is seen only in early years schools. It is important to separate the playground from the upper grade students, who might hurt small infants in early years schools by accident. Furthermore, children in early years schools require time to move from one place to another, so playgrounds next to classrooms allow more flexible use in classes and the teachers can monitor the children easily. For the same reason, among the specific action and multi-stimulation (static) types, which are often shared with other grades, soft play rooms and sensory rooms, which are frequently used, are located in the same area or on the same floor in all four schools. On the other hand, limited stimulation-type spaces such as calm rooms, which are often found in the same area or on the same floor in primary and secondary schools, are not found in any other GD school. Conversely, quiet corners with furniture or tents are often seen in early years classrooms and might be used as limited stimulation-type spaces.

(2) Primary: A common feature in all of the primary schools is to have a terrace (S) with direct access to the classroom. Even in the LV school, where classrooms are located on the upper floors, the terrace (S) is secured, indicating that it is important to have an external space directly accessible from the classroom, even if the space is small. By having the terrace (S) with direct access to the classrooms, children can briefly refresh themselves outdoors and then resume their classroom activities in a smooth flow. In the OG, GD and HW schools where the classrooms are on the ground floor, the terrace (S) is connected to the playground (S) or (L), which can be accessed through a door. The terrace (S) acts as a buffer zone between indoor and outdoor activities, providing opportunities for emotional stability for children with autism who are uncomfortable with sudden changes in the physical environment. In other schools, except for the LV school, limited stimulation-type spaces are provided in the same area or on the same floor. Limited stimulation-type spaces tend to be separated, unlike the cases in early years schools.

(3) Secondary: In the secondary schools, no clear relationship exists between classrooms and outdoor spaces, as seen in the early years and primary schools. Limited stimulation-type spaces are located in the same area in all school classrooms except the GD school, making it easy for students to leave the classroom, calm down and return to the classroom.

(4) Post-16: The sample number of post-16 schools was small, but when combined with the results of the teacher interviews, the special considerations seen in the lower grades became less necessary, and students were expected to behave independently. Many students have matured to the point where they can find an appropriate place to calm down on their own when they can no longer tolerate the classroom environment, such as by going out into the hallway to walk or sitting still to regulate their feelings (according to the principal in the MT school). However, because each child develops differently, individualised support is necessary, even in post-16 schools. Considering the fact that a group room in the MT school was used as the personal space of a student who had difficulties working alongside his classmates, group rooms allow flexible use and help schools accommodate each situation.

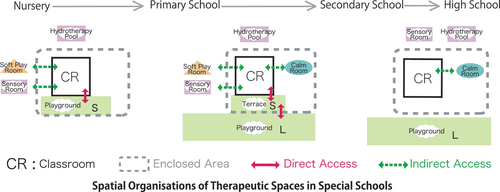

4.3. Summarising results

Looking at the spatial organisations of therapeutic spaces around a classroom, each age group has its own characteristics, so it is important to configure therapeutic spaces in a way that best supports the needs of the child as they develop more independence, coping strategies and life skills through each stage of development. shows a summary of adjacency diagrams for different ages and approaches installing therapeutic spaces. The results of this study suggest the following.

In nurseries (early years), considering the fact that the children are still too young to move around in addition to their differences in physical ability with the older students, the creation of a dedicated area for nursery classes should be the main focus. A playground should have direct access from the classroom, and a sensory room and a soft play room, which are frequently used, should be located within the area or close to the classrooms. Areas for personal space and calming down should be provided in the classroom, and teachers should be able to guide children immediately when they become upset.

(2) In primary schools, providing an outdoor space accessible from the classroom remains an important issue, but the area is much smaller than that in nurseries. Even if a terrace were small, it could be used for getting a breath of fresh air, and if a trampoline were set up, children could jump up and down for a few minutes until calming down and returning to their classroom. If the terrace had a large playground beyond it, it could be a place that would help prevent children from running away suddenly or assist them in gathering themselves for activities at the large playground.

A therapeutic space to stay still, such as a calm room, should be located near the classroom, and the short distance through the hallway should provide a different atmosphere than the quiet spaces in the classroom or adjacent group room.

(3) In secondary and high schools (post-16), the need for special support decreases as students grow older. Students may still need a calm room or a study room, but by the time they reach high school, they are able to find a personal space in the hallway when they want to be alone. If possible, outdoor spaces should be located adjacent to the classroom, but this is not as important as in nurseries or primary schools.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we defined a “therapeutic space” as a space for children with ASD to calm and regroup, and clarified the types and functions of therapeutic spaces and the spatial organisation based on the classroom in six special schools in the UK. We identified 10 different therapeutic spaces. These therapeutic spaces were characterised as a pair of either multi-stimulation or limited stimulation and either dynamic or static by four types: limited stimulation type (calm rooms, study rooms and nurture rooms); specific action type (soft play rooms, trampoline rooms and ramps); multi-stimulation (static) type (sensory rooms and hydrotherapy pools); and multi-stimulation (dynamic) type (terraces and playgrounds). This study also provided adjacency diagrams between a classroom and therapeutic spaces and analysed spatial organisation by age group. Ideally, classrooms in nurseries or primary schools allow direct access to outside spaces. Moreover, having soft play rooms and sensory rooms in close relation to the classrooms is important. In primary schools, calm rooms and other therapeutic spaces of the limited stimulation type close to the classrooms can serve as areas of refuge. The arrangement of therapeutic spaces around classrooms in secondary and high schools becomes simpler as the requirement for older students who have become more independent have fewer requirements. The spatial organisations reflect the educational phase of the students. Hence, structured therapeutic spaces around a classroom suitable for each stage of development is important for designing successful school premises.

The findings of this study regarding the categorisation and spatial organisation of therapeutic spaces could be expected to act as a common language between teachers and architects in discussion and a road map to designing special schools. Although the findings were based on cases in the UK, the spatial characteristics illustrated in this study were implemented based on culture and the characteristics of ASD. It is thought that the same can be applied to special needs schools in Japan and other countries, although some may have to be rearranged.

Although group rooms were excluded from the analyses, they play an important role in complementing the calming environment because they are used to supplement functions that are not available around the classroom (Matthews and Lippman Citation2020). When designing special schools in the future, it will be necessary to examine comprehensively the location of the spaces that were not dealt with in this study in relation to the classrooms.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to all principals, business managers and other staff members at the schools, who took us on school tours and shared their experiences. Special thanks should also go to all who shared their expertise of designing special schools: Andy Gollifer and Mark Langston in Gollifer Langston Architects; Claire Barton and David Givens in Haverstock; Lorna Ryan and Roger Hawkins in Hawkins\Brown; and Liam Presley, Daniel Keeler, Hiroshi Urushibara and Bob Wallbridge in HCC Property Services. This study would not have been possible without our students’ cooperation in school visits and drawings. We would like to express our gratitude to Hazuki Misawa and Marie Kitano in Chiba University and Aoi Kitsuki and Shinya Fukumitsu in National Institute of Technology, Kure College.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ayres, A. J. 1972. Sensory Integration and Learning Disorders. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Western Psychological Services.

- Cardellino, P., R. Leiringer, and D. Clements-Croome. 2009. “Exploring the Role of Design Quality in the Building Schools for the Future Programme.” Architectural Engineering and Design Management 5 (4): 249–262. doi:10.3763/aedm.2008.0086.

- Chiles, P., L. Care, H. Evans, A. Holder, and C. Kemp. 2015. Building Schools: Key Issues for Contemporary Design. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Department for children, schools and families. 2008. Building Bulletin 102: Designing for Disabled Children and Children with Special Educational Needs. Norwitc, England: Stationery Office/Tso.

- Department for Education (2015). “Building Bulletin 104: Area Guidelines for SEND and Alternative Provision.” Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/905693/BB104.pdf Accessed 15 March 2019.

- Department for Education (2018). “Special Educational Needs in England: January 2018.” Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/729208/SEN_2018_Text.pdf Accessed 25 February 2019.

- European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. (2003). “Special Needs Education in Europe.” Publication. January Retrieved from: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/special-needs-education-in-europe_sne_europe_en.pdf Accesses 18 March 2021.

- Gaines, K., A. Bourne, M. Pearson, and M. Kleibrink. 2016. Designing for Autism Spectrum Disorders. New York: Routledge.

- Hawkins\Brown & The Architects’ Journal. 2015. #great Schools, Making the Case for Good Design. London: Emap, powered by Top Right Group.

- Hulsegge, J., and A. Verheul. 1987 Snoezelen : another world : a practical book of sensory experience environments for the mentally handicapped . Chesterfield: Rompa Editorial.

- Imabayashi, H., M. Tsuda, H. Ohki, F. Shiwa, and T. Takeshita. 2012. “Characteristic and the Number of Self-enclosed Space in Special-needs Schools: Research of Self-enclosed Space in Special-needs School Part1 Architectural Institute of Japan.” In Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, 497–498. Tokyo: Architectural Institute of Japan.

- Kanner, L. (1943). “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact. Publisher Not Identified.” Retrieved from: http://mail.neurodiversity.com/library_kanner_1943.pdf Accessed 24 April 2021.

- Koegel, L. K., A. K. Singh, and R. L. Koegel. 2010. “Improving Motivation for Academics in Children with Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 40: 1057–1066. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-0962-6.

- Koga, M., H. Hori, and A. Yamada. 2017. “Actual Conditions of Management and Evaluation to Learning Environment by Teacher by Questionnaire Survey to the Elementary Department of Former Blind-deaf-specail School.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 82 (737): 1673–1683. doi:10.3130/aija.82.1673.

- Lane, S. J., Z. Mailloux, S. Schoen, A. Bundy, T. A. May-Benson, L. D. Parham, S. Smith Roley, and R. C. Schaaf. 2019. “Neural Foundations of Ayres Sensory Integration®.” Brain Sciences 9 (7): 153. doi:10.3390/brainsci9070153.

- Lovaas, O. I. 1987. “Behavioral Treatment and Normal Educational and Intellectual Functioning in Young Autistic Children.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.1.3.

- Matthews, E., and P. C. Lippman. 2020. “Physical and Spatial Organization of Early Childhood Classrooms.” In Encyclopedia of Educational Innovation, edited by M. A. Peters and R. Heraud, 1–5. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- McAllister, K. (2010) “The ASD Friendly Classroom – Design Complexity, Challenge and Characteristics.” in D. Durling, R. Bousbaci, L. Chen, P. Gauthier, T. Poldma, S. Roworth-Stokes, and E. Stolterman (eds.), Design and Complexity - DRS International Conference 7-9 July 2010, Montreal, Canada. https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/drs-conference-papers/drs2010/researchpapers/84

- Mesibov, G. B., V. Shea, and E. Schopler. 2004. The TEACCH Approach to Autism Spectrum Disorders. New York: Springer Verlag.

- Sekizawa, K. 1998. “A Study of Classroom Units at the National Kurihama School for Handicapped Children.” Journal of Architecture, Planning and Environment Engineering 503 (503): 85–92. doi:10.3130/aija.63.85_1.

- Sohn, E. (2020). “The Blurred Line between Autism and Intellectual Disability.” Deep Dive, Spectrum | Autism Research News. : https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/the-blurred-line-between-autism-and-intellectual-disability/ Accessed 27 August 2021.

- Thurm, A., C. Farmer, E. Salzman, C. Lord, and S. Bishop. 2019. “State of the Field: Differentiating Intellectual Disability from Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 10: 526. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00526.

- Ueno, K., and C. Nakajima. 2012. “Fieldwork Study on Acoustical Environment of Learning and Living Spaces for Children with Disability.” Journal of Environmental Engineering (Transactions of AIJ) 77 (682): 933–939. doi:10.3130/aije.77.933.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2021). “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).” Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html Accessed January 7.

- Vogel, C. L. (2008). “Classroom Design for Living and Learning with Autism.” Autism Asperger’s digest 7. Retrieved from: https://studylib.net/doc/7326575/classroom-design-for-living-and-learning-with-autism