ABSTRACT

From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, a number of missionary universities made outstanding contributions to higher education in China and left valuable heritage on their campuses. Among them, the University of Nanking (UNK) has played a significant role in the modern history of China. This paper uses the renovation of an anonymous building on the UNK campus as an opportunity to address research questions such as: When was the building built?; Who worked or lived in this building? What is the relationship between the building and the campus? Moreover, this research aims to illustrate the value of the building and offer a scheme for its conservation. The research applies archival research methods on historical documents, photos and maps; and empirical research via a site survey examining architectural features. The findings reveal the building was the residence of John Elias Williams, a vice president of UNK. Next to the central axis of the campus, his residence was built temporary with a good view for supervising the construction of the campus. This research enriches the history of UNK by recognising the cultural significance of an anonymous campus building, which provides important evidence for the development process of UNK.

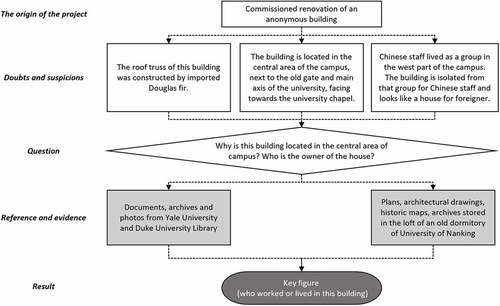

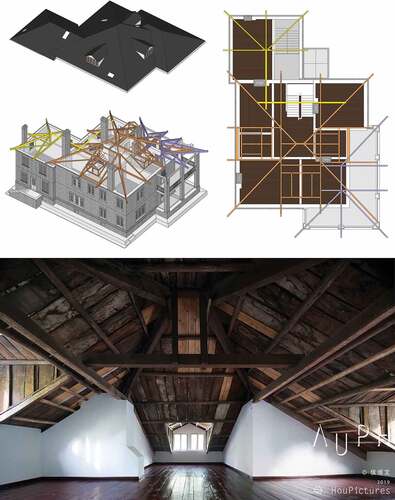

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, a number of universities and colleges were established as the forerunners of modern higher education in China. These universities were mainly established by overseas Protestant and Catholic churches; hence they are called missionary universities. At the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), there were eight missionary universities but only three state-run universities (Imperial University of Peking, Shanxi University and Peiyang University). Towards the end of the 19th century, there were 16 missionary universities in China, 13 of which were established by Protestant churches and three by Catholic churches (Xie and Walker Citation2021). Missionary universities directly introduced Western modern education to China and had a profound influence on culture, education, science and technology, medicine and other fields, with a tremendous influence on China’s higher education.

These missionary universities not only laid a strong foundation for China’s higher education and contributed to the cultivation of talent in many fields, but also left a valuable architectural heritage in campus planning and campus architecture, which has shaped China’s campus planning and design (Tang Citation2004; Tong, Tang, and Li Citation2020). Regarding campus planning, China’s missionary universities imitate characteristics of Western universities such as their symmetry and geometric composition. Regarding architectural style, school buildings in China’s missionary universities incorporate characteristics of traditional Chinese architecture. The University of Nanking (UNK) was the first missionary school to combine the traditional “big roof” style of official architecture in North China with the Western architectural style in its school buildings (); this was later learnt and imitated by many missionary and national universities in China (Leng and Zhao Citation2003). This localised campus architectural style has become the symbol of China’s missionary universities and is part of the precious built heritage in China.

Figure 1. The traditional “big roof” style school buildings in UNK.

Campus buildings, as the architectural heritage of a university, play a significant role in school or campus identity in Western universities. For example, alumni and staff at Florida State University have promoted the Heritage Protocol to preserve the history of the university and its cultural heritage. History and heritage are important for the development of a university because they offer easy ways to connect with its alumni for both friend-raising as social capital and fund-raising as economic capital (Woodward Citation2013a, Citation2013b). According to Poor and Snowball (Citation2010), students place positive intrinsic value on their campus built heritage, and campus symbolic built heritage contains significant marketing implications, particularly in universities those are managing to attract international students from diverse cultural backgrounds. The Forgan Smith Building and the Great Court at the University of Queensland (UQ) are good examples (Moore Citation2011). Generations of Queenslanders, as well as an increasing number of international students, receiving a higher education at UQ have passed through the doors of the university’s landmark Forgan Smith Building, chatting, discussing and laying on the lawn of the Great Court; hence, UQ alumni have strong emotions and memories attached to the campus built heritage. All above reflects a sense of place and its relavent place attachments that belong to a university campus also contribute to shaping the identity to the campus (Malpas Citation2008).

However, campus architectural heritage has not been well preserved in China. The widely accepted awareness of heritage conservation was not raised in China until the 1980s. China has no tradition of architectural heritage conservation until the first generation of architects set rules and regulations for conservation; nor does it follow modern heritage conservation philosophies and principles from the Western world until the end of the 1970s. In other words, China missed an opportunity to follow the modern heritage conservation philosophies and principles such as the International Charter for The Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter) in 1964 because of interruptions caused by internal conflict and movements such as the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). Because of the consequent lack of systematic knowledge of architectural heritage, many campus heritage buildings have been demolished or renovated without consideration of protecting their heritage characteristics, and destroying their heritage values.

The heritage status of China’s historic campus buildings does not often match the value of campus built heritage. In other words, the value of campus built heritage has often been neglected or misunderstood, and consequently damaged in the absence of heritage listing (Smith Citation2006). University campuses are places for knowledge sharing and understanding of the cultural significance, which builds a connection between people and campuses. Therefore, to understand the value of campus built heritage, its history and attached socio-cultural and emotional values should be taken into consideration; and the built heritage along with the campus should be defined as a place full of humanistic spirits and values. However, the sense of place has been diminishing in many Chinese universities, losing their genius loci. Zhao (Citation2007, Citation2012) argues that the mismatch between the history of a university and its campus leads to the loss of genius loci. For example, when people talk about Peking University today, they mention the history of the Imperial University of Peking; however, the picturesque campus of Peking University occupies the campus of Yenching UniversityFootnote1 rather than the campus of the Imperial University of Peking. Similar mismatches between the history and campus occur in many universities in China and cause confusion so that heritage interpretation should be carefully planned and designed to enhance the identity of a place (Uzzell Citation1996). Therefore, matching the history and the campus correctly is crucial to creating a sense of place on a historic campus.

Nowadays, the concept of place is widely used in the field of heritage management. Through the development of world heritage charters and documents, it is common to see the emergence of the significance of place-based value (Australia International Council on Monuments and Sites [ICOMOS] Citation2013) as well as spiritual and emotional value (ICOMOS Canada Citation2008; ICOMOS Citation2011). From this perspective, heritage should be defined as a place that includes a historic building or site, as well as its history and attached socio-cultural environment. As Smith (Citation2006, 75) argues:

This idea of place is vital for understanding heritage. Heritage as place, or ‘heritage places’, may not only be conceived as representational of past human experiences, but also as creating an affect on current experiences and perceptions of the world. Thus, a heritage place may represent or stand in for a sense of identity and belonging for particular individuals or groups. However, it may also structure an individual’s response and the experiences an individual may have at that place, while also framing and defining the social meanings these encounters engender.

In this paper, the research object is an unvalued and anonymous campus building being renovated on the north Gulou campus of Nanjing University that commissioned by the university administration department. Nanjing University derives from UNK and occupies the former site of UNK in the former capital city Nanjing (spelled “Nanking” in the past). Architectural historians and researchers have studied heritage buildings in UNK for years and established a database of campus buildings, such as foreign residences of Pearl S BuckFootnote2 and John RabeFootnote3 (Leng and Zhao Citation2003; Leng Citation2010). However, there is no research on this anonymous building on the campus of UNK before. By examining historic photos, maps, documents and relevant archives, and reporting on a site and architectural inspection, this paper aims to discover the history and value of the anonymous building on campus to address research questions such as When was the building built? Who worked or lived in this building? What was the relationship between this building and the campus? Then, the findings may help to determine how to conserve the value of this building and its surrounding environment in practice. This study may contribute to the history of the campus, so the unvalued campus building deserves careful inspection and the potential cultural significance and place meaning attached to the building on the campus needs to be highlighted. Later, the renovation will further create a sense of place and identities attached to the campus and build connections between the campus and students, staff and alumni.

2. Research framework and method

The writing of history can never avoid the subjectivity of the times. Thus, the writing cannot offer a whole picture of a historical truth without any objective pieces of evidence including historic documents, photos and maps. In addition, architectural heritage is also a type of evidence supporting real history. From this perspective, in this paper, a connection has been built between the anonymous building on the campus of UNK and its history.

In this project-based research, empirical research methods were applied, involving historical materials and material objects that are mutually validated. Specifically, literature and archival research (history, documents, photos and historic maps) were adopted to discover historic information about the anonymous building. Site and architectural surveys were also conducted to examine aspects of the building such as its architectural features.

Historic documents, photos and historic maps were collected from the Nanjing University Library, Nanjing University Archive, Duke University Library and Yale University Divinity School Library Repository. As the historic photos are black and white they may lose some important information. To solve that problem, in recent years, a dramatically developed artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm was used in image processing to colourise the black-and-white photographs. In this research, the online AI Photo Coloriser (https://hotpot.ai/colorize-picture) was applied to automatically colourise old photos. The basic principle of colourising black-and-white photos is based on AI technology, especially a deep learning algorithm (feed-forward convolutional neural networks). By feeding with millions of colour photos, the online AI Photo Coloriser has been trained as a model to map the black-and-white photo from a grayscale input to a distribution over quantised colour value outputs and generate colourised photos automatically (Zhang, Isola, and Efros Citation2016).

Regarding the architectural survey, our team participated in the site and architectural surveys and the conservation process from 2018 to 2019. By carefully examining the building in terms of its space, materials and structure, a digital model of the building was reconstructed to analyse and understand its construction process and characteristics. Then the building was restored based on information of its current state, archival research and the digital model analysis.

These archival research and architectural analyses contributed to the final scenario of building conservation, which may create a sense of place on campus.

3. Discovering an anonymous building on campus

To give the reader an overview of the process of discovering the key figure who worked or lived in this building, a diagram is used to outline the source of a project as a commissioned building renovation and shows the process of having doubts and suspicions, raising questions, finding evidence to reveal the key figure who worked or lived in the building ().

The anonymous building commissioned for renovation in 2018 was an unimpressive building located in the central area of the north campus of Nanjing University being used as an office building by the United Front Work Department. When that department attempted to renovate the building, they were confronted with the issue of roof leakage during heavy rain. Thus, to repair the roof, they removed the ceiling, revealing a magnificent timber roof truss. The construction manager and builder invited our team to determine whether the building has historic values and should be heritage listed.

The research began with an inspection, which revealed a complex roof structure made of strong timber material, with a bottom chord made of Douglas fir and reaching 12 metres. According to Chinese architectural history, Douglas fir was not a local construction material grown in China but was imported from overseas, which was rarely used in local buildings. Therefore, the owner/user/administrator of the building was suspected of having the power to obtain the overseas material to construct such a building. Further, the layout of the building differs from that of a traditional Chinese residence, suggesting it was designed as a foreign residence. Regarding its position, the building is located north of the Twinem Memorial Chapel, south of the Teaching Building and next to the main axis of the historic campus region, which is the central area of the campus. Thus, two emerging questions were why was this building built in the central area of UNK; and who worked or lived in this building? As a missionary university founded by American churches, UNK has separate zones for teaching and residence. The outstanding position of the building, located in the central area on campus, implies it might be used by a Westerner of high social status who must have a close relationship with the university.

Historic maps and documents may contain clues about the identity of who worked or lived in the house. However, from the 1910s to the 1970s, a series of devastating historic events occurred in Nanjing, including the Nanjing Massacre and the nationwide Cultural Revolution. Many precious archives, maps and documents were burned during these events or confiscated for political reasons. According to the Nanjing University Archive, relying on the opportunity of renovating campus buildings during the centennial anniversary of the university in 2002, a box of historic documents, maps and architectural drawings were found in the loft of the campus dormitory. They may have been stored there intentionally to avoid them being destroyed or confiscated.

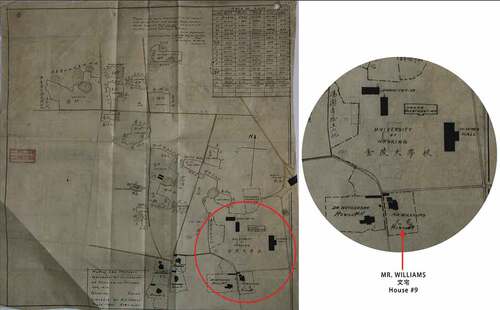

These documents included UNK campus planning maps, which were sorted chronologically to determine when the residence had been built. The first map to show the profile of a “new residence” fitting that of the residence is a 1911 site survey map. The house appears on every campus map since, and on the “Map of Ing Property Purchased by UNK” in 1919 reproduced in the building is labelled “Mr Williams House #9” (“文宅” in Chinese), providing a key piece of information. From this point onwards, the key figure who lived in the house emerged. This led to further questions to be solved in the next section:

Who was Williams?

Why was his house built in the central area of the university campus?

What is the significance for Nanjing University of Williams and his former residence?

4. Discovering Williams

4.1. Who was Williams

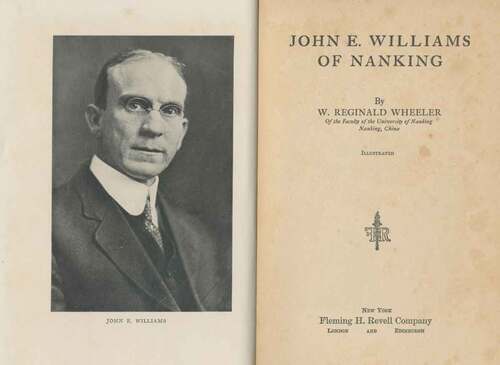

During a visit to the University of Pennsylvania in the United States (US) in 2011, the corresponding author by chance had purchased a second-hand biography entitled John E. Williams of Nanking (Wheeler Citation1937) (). According to this biography, Williams’ full name was John Elias Williams (1871–1927), born in Coshocton, Ohio (US). He began studying at Marietta College in 1890, and in 1896 taught at the Salem Academy (Wheeler Citation1937, 34–36). Later in 1896, he entered advanced theological training at the Auburn Theological Seminary, which he completed in 1899 (Wheeler Citation1937, 37–39). Williams then applied to the Presbyterian Board for a missionary appointment.

Williams received his commission as a missionary, being appointed to the Central China Mission of the Board, with “special funds” supplied by the End Presbyterian Church of New York for his service in China. John and his wife Lilian Williams sailed for China attended a mission meeting held in Soochow on 20 September 1899. It was at these meetings that “newly appointed missionaries were assigned generally to a mission, and the mission had the right of assignment to a particular station on the field” (Wheeler Citation1937, 43). Following the resignation of TW Houston – the second principal of the Presbyterian Academy (益智书院)Footnote4 in Nanjing – Williams was assigned its third principal (Wheeler Citation1937, 58).

During the time in the Presbyterian Academy, Williams considered the issue of scattered educational resources in Nanjing by different missionary schools founded by different churches in China and advocated for cooperation rather than competition among missionary schools and churches. This idea contributed to establishing a united school in Nanjing. To promote consolidation of schools and colleges in Nanjing, during his furlough, Williams raised $30,000 in cash and pledges, and $10,000 credit for land as a foundation for the campus of a new united UNK (Wheeler Citation1937, 65–66). The Presbyterian Academy was merged with the Christian College (基督书院)Footnote5 and united under the name Union Christian College (宏育书院) in 1906. It then merged with Nanking University (汇文书院) in 1910 to become UNK (金陵大学, ) and Williams was appointed as its vice president (Wheeler Citation1937, 58).

4.2. The death of J.E. Williams

Williams was an influential person in the promotion of Chinese higher education. However, he was sadly killed during the Nanjing IncidentFootnote6 in 1927. Despite varying descriptions of this incident, the widely accepted background is as follows. The advancing troops of the Nationalists’ Northern Expedition Army arrived in Nanjing on 23 March and the defending troops of the Zhili–Shandong coalition were forced to withdraw into the city. The Northern Expedition Army thus broke into the city and caused chaos on 24 March. During that period, large-scale anti-foreign activitiesFootnote7 were undertaken throughout China: robberies and looting occurred frequently and some foreigners were even killed. These contributed to the Nanjing Incident, which had a devastating impact on the UNK. Equipment in the attached middle school and science buildings was damaged. Meanwhile, some of the student dorms, the homes of five faculty members were extensively looted or burned down (Jiang Citation2016). Among these impacts, the most grieved was the death of Vice President John E Williams. Wheeler (Citation1937, 25–26) depicts the events of the morning of 24 March 1927 as follows..

The soldier in front of Dr. BowenFootnote8 took his watch; the soldier before Dr. Williams reached for his watch and chain. In a friendly, half-joking way Dr. WilIiams remarked in Chinese, ‘You don’t want to take that, do you? That watch isn’t worth much, but my mother gave it to me and I would like to keep it’. The soldier who had been in such an ugly mood pointed his rifle at Dr. Williams, and shooting from the hip, pulled the trigger. With a cry of ‘Kwai! kwai!’ (‘How strange!’) Dr. Williams fell to the ground with a bullet through his temple.

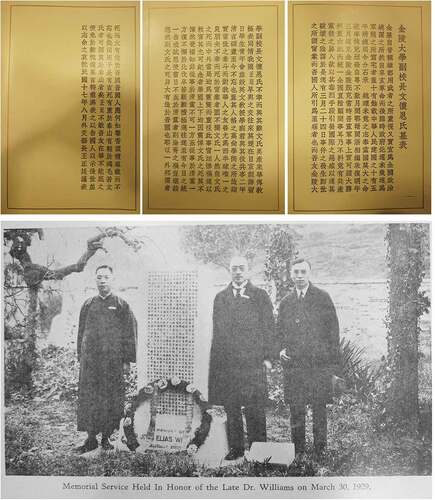

Williams’ death was mournful and tragic. According to Xie (Citation2018), Williams’ tomb was located in the (since destroyed) foreign cemetery in the southwest part of Qingliang Mount in Nanjing. His gravestone was carved with an epitaph written by Zhengting Wang, then foreign minister of the Republic of China, and the epitaph was reproduced in the Tribute in Memory of Dr. John Elias Williams (). Wang outlines the historic background and explains how he met and worked with Williams at the Tokyo Youth Students Association between 1906 and 1907 when Williams was teaching English there. In this tribute, Wang acknowledges Williams’ contribution to China and his kindness to Chinese people and expresses his deep regret and sadness over Williams’ death.

5. Williams’ House and University of Nanking

Having described Williams’ life story and contributions, this section utilises collected historic planning maps and photos to examine why Williams’ House was built in the central part of the UNK campus.

5.1. The reason for the site selection for Williams’ residence

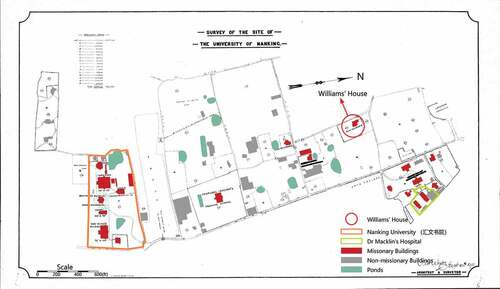

Among the collected materials, the earliest showing Williams’ House is a site survey map of the UNK in 1911 drawn by a US architect (). This precious map clearly presents the road system, ponds and property plots around the campus area of UNK. The map also shows existing missionary buildings (in red colour) and those non-missionary buildings (in grey colour) that were demolished for the construction of campus later.

Figure 7. Survey of the site of UNK in 1911.

By comparing this site survey map with today’s UNK campus map, the orange area at the left (south) side of the map was identified as the former Nanking University,Footnote9 one of the origins of UNK. The group of buildings in the green area on the right-hand side (north-east corner) include Dr Macklin’s Hospital and the Christian College. Based on the positions of Nanking University, Dr Macklin’s Hospital and the road system, we infer that the campus of UNK was planned to be built in the central area of this map. Further, several new residences are shown on the map, including the position of Williams’ House as evident from its shape.

This 1911 site survey map shows no educational buildings within the potential UNK area although there are some residences (Williams’ House, Bullock’s House and Residence of Disciple’s Mission) and a proposed teachers’ training school on the site of the campus. The vacant lot at the northern end of the campus, which is the historic landmark area of Nanjing University today, provides further evidence that Williams’ House is the oldest building in this part of the campus.

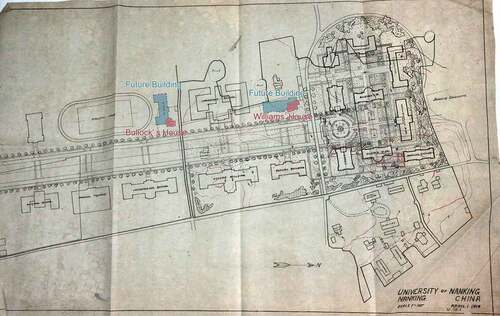

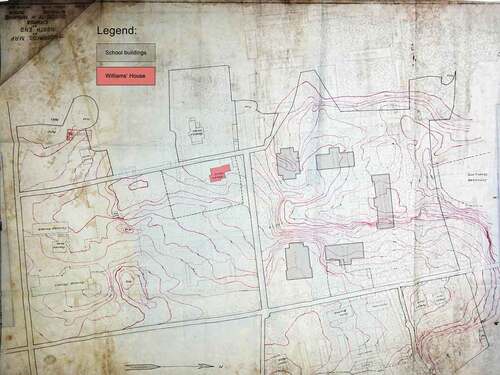

This raises the question of why the house was built in the central area of the university campus. Among the materials, a 1914 campus site planning map offers a clue (). It shows a boulevard as the obvious axis in the central area of the campus, with planned buildings on both sides of the axis symmetrically. However, the outline of Williams’ House overlaps with a building profile drawn with dashed lines, which is also true for Bullock’s House. Architectural drawings thus indicate that the two houses were planned for demolition to accommodate the future construction of new buildings, suggesting that Williams’ House was only supposed to be temporary.

Figure 8. UNK campus planning map (1914).

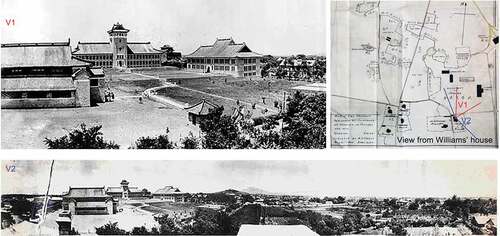

Among the collected materials, two photos taken from Williams’ House show that the position of the house has a broad view over the future campus. Thus it is conceivable that the house was built as a watchtower to supervise the construction of the school buildings on the campus (). In addition, a historic topographical map in 1914, overlayed with the campus plan () using Photoshop, illustrates that Williams’ House had been built before 1914 when the adjoining land for future construction of other school buildings was still a sloped vacant lot, which also supports the above assumption ().

Figure 10. Topographical map of the campus (1914).

All materials examined as described above prove that Williams’ House is one of the oldest buildings at the northern end of the campus, evidence for Williams’ ambition to settle on the campus personally and establish a new university for modern high education in China. Although Williams’ House is small, it was located in the central area of the campus, providing the best location from which to supervise the campus construction. During his period as vice president of UNK, Williams argued that the Chinese architectural style rather than the Western style would be more acceptable to Chinese people. He defended his viewpoint and made UNK the first university in China to employ the distinctive “big roof” style. After more than a century, Williams’ House has revealed Williams’ contribution to UNK and how it witnessed the history and growth of UNK, which creates the spirit of place.

5.2. Architectural information about Williams’ House through historic photos

Having discovered the relationship between UNK and Williams’ House, the heritage value of this residence has been defined. As part of the commissioned project, it is also necessary to understand the original appearance of this building, to conserve and repair it.

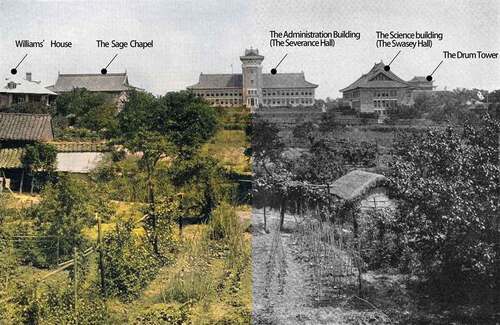

Perkins, Fellows & Hamilton Architects (Citation1925) describe the school buildings and campus planning of the UNK in the journal the American Architect. A panoramic photo attached to their paper shows several buildings including Williams’ House, the Sage Chapel, the Administration Building (the Severance Hall), the Science building (the Swasey Hall) and the Drum Tower outside the campus, respectively ().

Figure 11. Full view of the old campus of UNK (1920).

Another photo of the Sage Chapel of UNK taken between 1924 and 1927 was recovered from the photography collections of Sidney David Gamble.Footnote10 Gamble visited China several times and took many precious photos that recorded the landscape and lifestyle in early 20th century China. To illustrate the complex appearance and surrounding environment of the chapel, Gamble took this photo from the northeast corner of the chapel, also capturing the northern elevation of Williams’ House ().

Figure 12. The Sage Chapel and north elevation of Williams’ House (1924–27).

As a renovation project, restoring the building to its original appearance is the target; however, as it has been renovated several times its exterior and interior architectural characteristics have changed dramatically. provide some evidence regarding the original form and appearance of Williams’ House. According to these photos taken from the north and south side of Williams’ House respectively, the house was built with three dormers (on the south, east and west sides), which are preserved in the current building. A sunporch can also be seen on the east side of the building. A sunporch (i.e. veranda), which was rarely used in traditional Chinese residences, reflects the typical lifestyle of a Western family and influenced the modernisation of residences in China since the late 19th century (Liu Citation2011). However, the sunporch of Williams’ House might be considered more than just a lifestyle feature. Based on our visual analysis in , Williams’ sunporch may have been used as a location from which to supervise the construction progress of campus buildings.

Although offer evidence regarding the original form and appearance of Williams’ House, the colours of the building materials were missing. Thanks to new AI technology, it was able to apply online AI Photo Coloriser to automatically colourise the photos by uploading the black-and-white photos without any tunning.Footnote11 These colourised photos offer evidence for later reconstruction and renovation. For example, the colourised photos show that the house was built using grey bricks with four white timber windows in US style, as well as two chimneys, and the roof was built with a light colour, which all contribute to the later restoration.

6. Conserving Williams’ House as a heritage building

After Williams died in the Nanjing Incident, his house was used as a girls’ dormitory by UNK. When UNK was inherited by Nanjing University after 1949, the house was used by several schools and departments and is now used as the office building for the United Front Work Department.

In 2018, William’s House was listed as a historic building by Nanjing Government (Authorised number: NJ070) and our team was commissioned to propose a conservation scenario for this building, which requires historic research. Our review of archives and historic maps and photos provide us with background information about Williams and his house. However, no clear photos or drawings were found to show the full view or architectural details of the original house, so monographic research on architectural details and constructional features through an on-site architectural survey was necessary to gather important construction information about the building.

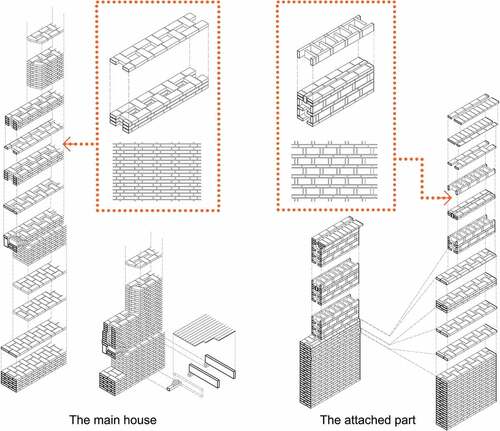

After undertook this commission in 2018, we carefully inspected the oldest building in the north Gulou campus. The survey revealed that Williams’ residence is composed of the main house and an attached part with a total area of 667 m2, including a basement (67 m2) and a loft (73 m2). Bricks and timber are the main materials used: both the main house and the attached part are constructed from masonry and timber. This was the typical structure combining Western and Chinese architectural and structural features in the early 20th century (Li Citation2004, 9). The main house, located to the south, has a typical US house style, while the attached part occupied by a kitchen and staircases is located in the north-west. The main entrance to the house faces east. There are three rooms on the ground floor (originally used as living, reading and dining rooms), and four bedrooms on the upper floor. Sunporches are attached to the southeast corner of the main house at both the ground and upper floors.

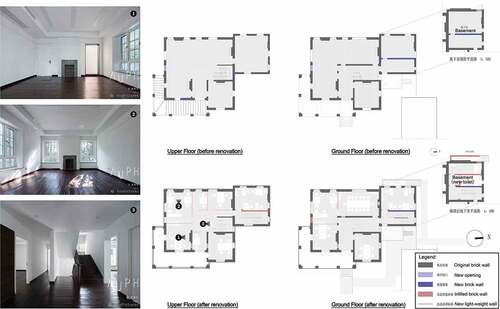

Before explaining our inspection and conservation strategy in the following sections, shows the appearance of Williams’ House before and after conservation, which gives the reader a general impression of the result of the renovation. In the following sections, the survey and conservation scenario are introduced in five parts.

6.1. Survey and conservation of brick walls

As the building has been renovated several times by different departments, the layout has changed drastically. The interior space has been reorganised by the addition of new walls and the façade of the house, originally left with bare brick, has been covered by cement mortar. To repair a historic building, it is necessary to understand how it was constructed. To that end, the cement mortar was peeled off and additional external brick walls were dismantled, which blocked the sunporch, to reveal the original layout and external material for inspection. When inspecting the connection part between the main house and the attached part, we found it is obvious that the main house and the attached part were constructed in different types of masonry bonds were used in their exterior walls (). No strong evidence has been found to explain why the house has two parts and uses different types of bonds in its brick masonry. A possible hypothesis is that the difference reflects the innovation of craftspeople in saving on bricks and construction time. Despite the difference in exterior walls, the plinths in both the main house and the attached part are constructed with a strong bond type called “Flemish Bond” to ensure the steadiness of the foundations.

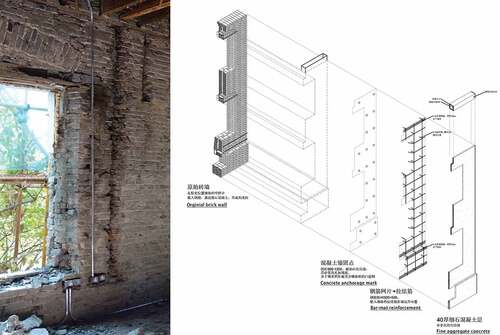

During the survey, after the cement mortar was peeled off, the masonry structure of the building was looked vulnerable that many bricks of the house were destroyed and became rough and fragmented, which is structurally unqualified and needed reinforcementFootnote12 ( left). To conserve the exterior brick wall façade of the building, bar-mat reinforcement was added on the inside of exterior walls ( right).

Some of the openings in the exterior wall were blocked off and bricks around some openings were fragmented. Relying on our research on the construction of openings in brick walls (), the openings were repaired according to vestigial evidence on the walls and the layout of the house. For example, fragmented bricks were replaced and the openings were recovered by adding flat archesFootnote13 using the original construction method (). Via this conservation approach, the original appearance of the walls has been recovered.

6.2. Survey and conservation of the interior space

The layout of the interior space of the Williams’ House has its historic value. However, since the house had been and was planned to be used as an office building before and after renovation, there might be conflicts between its historic values and use value because the layout had been and will be changed to some extent. Thus, the renovation should compromise and balance the historic value and use value.

To balance its historic value and use value, the current ground and upper floor plans were drawn based on the architectural survey and the new plan was designed to maximally recover the original plan of the Williams’ House (). When the cement mortar was peeled off, some traces that implied the original positions of the partition walls of the house were revealed. Thus, new light-weight partition walls have been added based on pieces of evidence that include these existing traces and other similar housing plans (e.g., the Bullock’s House and Pearl S Buck’s House) on campus. As mentioned in section 6.1, to meet the requirement of structural safety, the inner side of the exterior brick walls was reinforced. Both the inner side of the exterior walls and new lightweight partition walls were painted white for the brightness of the interior space. Since white plastering was found originally during the survey, the white coloured interior space balanced the historic value and use value. In addition, some original brick walls were conserved, especially the fireplaces, which act as the mark of its history and the typical indoor features of an American styled house built in Nanjing then.

6.3. Survey and conservation of the sunporch

The sunporch from which we assume that Williams supervised the construction of the school buildings on the campus is another significant element of the façade of Williams’ House. As shows, before conservation, the sunporch was blocked off by later-added brick walls and covered by cement mortar with a white coating. Therefore, the initial step was to deconstruct the additional walls to examine the status of the original sunporch. The architectural survey of the deconstruction process suggested that the structure of the sunporch was weak as the columns were constructed using bricks connected only by timber beams, which had been damaged by moths. A fragment embedded in the columns illustrated that handrails had originally been installed around the sunporch, offering evidence for later conservation; however, the handrails were missing following multiple renovations. Second, the size and position of the holes in the columns implied there were ceilings under the floor.

These speculations were later proven by a historic photo of Williams’ House taken from the southeast corner (). Although the photo is of poor quality, it clearly shows the sunporch with white ceilings and handrails, as well as white windows and doors, which needed to be recovered.

As ceilings covered the structure of the sunporch, it was able to strengthen the structure with new materials and techniques rather than repairing the original beams, without compromising the appearance. To recover the sunporch and ensure its structural safety, steel and reinforced concrete were used to rebuild the floor with timber decking as the surface material. Although steel was not the original material used in the floor of the sunporch, it has better durability as it cannot be damaged by moths, and could be hidden by ceilings under the floor ().

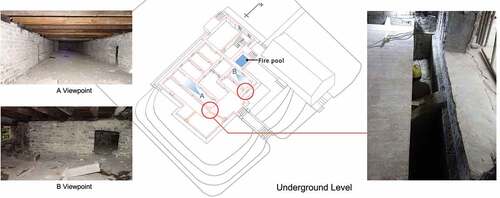

6.4. Survey and conservation of the underground level

To reinforce the brick walls of Williams’ House, the foundations were needed to be strengthened as well. When the timber decking of the ground floor was removed, an interesting underground level was uncovered.

To protect the house from moisture and humidity from underground, the interior was constructed with raised timber flooring and an underground ventilation system. In Williams’ House, the underground level was constructed with brick sleeper walls to support the beams for the raised flooring. These sleeper walls divide the underground space into several zones, with openings between different zones reserved for ventilation. The underground space of the main house is divided into eight zones, including two long rectangular zones, five short rectangular zones and an L-shaped zone (). Except for the latter, each zone has a venting interface on the exterior wall with a ventilation opening. The divisions of the underground level mean that humid air can be taken away, giving the timber flooring of the ground level more durability.

Normally, sleeper walls are constructed in the middle of a ventilation zone and perpendicular to the exterior wall to divide underground zones. However, the sleeper walls of Williams’ House connect obliquely to the exterior walls in two positions (red circles in ). This unusual method of construction avoids the ventilation openings on the central axes of the exterior walls. Thus, the speculation is that Williams’ House may have been constructed in a hurry and the oblique connection may be an on-site adjustment during its construction process.

Given the height difference between the interior and exterior space, two platforms served as side entrances to the attached part of the house. To maximise the use of space under the east-side platform, a partially underground emergency fire pool was installed (). Next to the fire pool under the attached part is an underground area located on the west side. Other than as a venting zone, this area is used as a storeroom, so underground venting zones are isolated between the main house and the attached part.

6.5. Survey and conservation of timber floors

Timber, especially Douglas fir, is widely used in Williams’ House. Douglas fir is a high-quality wood with few knots. It has high strength, wear-resistance and corrosion resistance, and was widely imported and used in buildings in China in the early 20th century. In masonry–timber structures, brick walls are constructed to support timber joists. In Williams’ House, floors are composed of timber joists and decking.

As mentioned in Section 6.3, the timber decking of the ground floor was removed to reinforce the building foundations. Following this step, to protect the heritage value, the timber decking to the ground level should be reinstated to ensure material authenticity; however, as the original timber was scuffed and caused an uneven floor, the university administrator requested it should be replaced with newly qualified timber decking. To preserve the material authenticity and collective memory associated with the original decking timber, it was used as a memorial decoration to cover an interior wall for touching to feel the sense of time and place ().

Figure 22. An interior wall covered by decking timbers disassembled from the ground floor.

Regarding the upper floor, after dismantling the ceilings, it was clear to see that the timber joists were laid into walls at both ends to support the load of the upper floor. In addition, X-shaped timber connections were used in the cavities between the timber joists under the floor to ensure its structural integrity and stability (). This was commonly done in detached houses during the 1920s to 1930s in Nanjing (Han, Chen, and Zhou Citation2020). The quality of the upper floor timbers was better than those of the ground floor, so the timber decking on the upper floor was preserved to ensure the material authenticity.

6.6. Survey and conservation of the roof

The roof of Williams’ House is special and complex. It is composed of a three-roof system. To understand its roof systems, a digital model was built in which the three roof systems are coloured yellow, brown and purple, respectively (). The diagram shows the loft area under the brown roof truss with three dormer windows attached to it. As the brown roof truss covers the main loft space with the largest span, it reaches 12.5 metres, with 120 × 250 mm2 in section size. These spans and sizes of materials are rarely used in Chinese residences in the early 20th century, demonstrating the special architectural heritage value of Williams’ House.

Figure 24. The digital model of the roof truss (top) and photo of the roof truss after renovation (bottom).

In terms of roof conservation, the loft space was renovated and the roof structure was intentionally exposed to show its value. Most of the roof boarding has been retained except for some leaking pieces, and insulation is planned to be added above the roof boarding to meet current requirements; although this process has been cancelled as a result of administrative issues.

7. Discussion and conclusion

This paper first introduces the background of an anonymous building on the north Gulou campus of Nanjing University. After analysing collected historic documents, photos and maps, the anonymous building was identified as one of the earliest campus buildings, constructed before 1911 as the residence of J. E. Williams, a former vice president of UNK. Archives and documents reveal the life story of Williams, especially his contributions to higher education in China and to the construction of the UNK campus, which enrich the history of the university.

In addition, the paper briefly introduces the conservation work on Williams’ House based on the site and architectural surveys, archival research and authors’ empirical knowledge and experiences (derive from other similar campus buildings at Nanjing University) along with limited historic documents.Footnote14 In this conservation program, how to highlight the original form and appearance of the house by researching its construction conditions and techniques, and how to link the architectural heritage of the house with Williams’ contribution to the construction of UNK were deliberately considered. The recovery of the sunporch of the house is an example of how we exhibited the relationship between Williams’ House and the old campus, consistent with his house being located in the central area of the campus to enable him to supervise the construction of future campus buildings.

A campus is a place with genius loci. This requires us – as students, staff and alumni – to understand the history and development process of our campus. As Harvey (Citation2001) argues, a profound understanding of the historically contingent and embedded nature of heritage contributes to the production of identity. According to this viewpoint, an understanding of campus history, along with relevant historic figures and historic buildings, may help us build a connection between us and the campus, and shape our identity. More importantly, architectural heritage along with its built environment becomes the “time-space mark” of campus because they store the history and memory of the place and play a role as an educator and an advocator for the unique information of the campus. Therefore, regarding conservation, the history and information attached to the campus architectural heritage should be respected to maximise its cultural influence and create a sense of place. In this case, the renovation of Williams’ House is based on its heritage values and its surrounding pathway is designed as a public route, which improves the historic built environment and will attract people as a landmark of the campus. Later, collected materials of Williams and his residence are planned to be exhibited on the wall of the sunporch of the house to illustrate the cultural significance of this building and its attached history. In this way, Williams’ House is expected to become an active place with cultural and spiritual values to enhance the identity of students and staff and establish a sense of place at Nanjing University.

In conclusion, this paper introduces the process of discovering an anonymous building (Williams’ House), which offers us an opportunity to see Williams, as a foreign missionary and later vice president of UNK, who fought for higher education in China. His sacrifice should be remembered and his contributions marked along with Williams’ House on campus become a symbol that contributes to the sense of place at Nanjing University.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the support of the Nanjing University Library, Duke University Library and the Yale University Divinity School Library Repository. Thanks to the support of Yuxiu Postdoctoral Institute of Nanjing University. Thankfulness should also be given to Professor Chen Zhao who enlighten us in architectural heritage studies and Professor Xianjin Huang for his kind support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xiaoxin Zhao

Xiaoxin Zhao is a postdoctoral research fellow affiliated with the School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Nanjing University. He obtained his PhD degree at the University of Queensland in the field of architectural heritage management and place studies. Xiaoxin’s academic interests and recent publications include historic urban landscape, heritage studies, rural revitalisation, and vernacular architecture.

Tian Leng

Tian Leng is an associate professor affiliated with the School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Nanjing University. He was a visiting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania in 2011. His research interests focus on modern Chinese architectural history and culture, historic architectural heritage, and architectural conservation and renovation.

Yu Wang

Yu Wang is a teaching assistant affiliated with the College of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Guilin University of Technology. He obtained his master degree in the field of historic architectural conservation and renovation. His research interests focus on historic building techniques and history.

Shuyong Chao

Shuyong Chao is a PhD student affiliated with the School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Nanjing University. He obtained his Master degree in the field of architectural history and theory. Chao’s academic interests focus on Chinese architectural history, urban history and architectural heritage.

Notes

1 A famous missionary university in Beijing designed by Henry Killam Murphy.

2 Pearl S Buck was an American writer and novelist. Pearl Buck spent the most important period of her literary career at the University of Nanking between 1919 and 1934. Her novel The Good Earth was the best-selling book that depicts Chinese peasants’ life and won her the Pulitzer Prize in 1932. In 1938, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

3 John Rabe was a German businessman and a hero best known for his efforts to stop atrocities of the Japanese army during its occupation of Nanjing and his work to protect and help Chinese civilians during the massacre that ensued. He helped to establish the Nanking Safety Zone to shelter approximately 200,000 Chinese people from slaughter when the city fell to the Japanese troops.

4 The Presbyterian Academy was founded by the American Presbyterian Mission.

5 The Christian College was founded by the Christian Mission.

6 The Nanking Incident occurred on March 21–23, 1927 when Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist) troops entered the city as part of their Northern Expedition military campaign (1926–1928). Troops particularly targeted the city’s foreign residents; several were killed or injured and their property looted, and the American, Japanese and British consulates were attacked.

7 Since the early 1920s, “de-Christianise” movements emerged to “take back” education from foreign churches in China. They opposed imperialist cultural invasion by Christian education and aimed to promote nationalist education by Chinese staff; this later intensified unto further nationwide anti-imperialist actions as part of the May 30 Movement of 1925.

8 A J Bowen was then president of UNK.

9 The site of the former Nanking University has been converted into Jinlin High School, one of the top high schools in Nanjing.

10 Sidney David Gamble (1890–1968) was an American socio-economist.

11 In this paper, a collage of the colourised and original photos has been used to show the difference.

12 The structural quality of the house was assessed by structural engineers with a report that the building needs reinforcement. After consulting with the structural engineers, if the exterior brick wall façade needs to be preserved to show the appearance, the inner side of the exterior walls should be reinforced to ensure safety.

13 A flat arch (sometimes called a straight arch) is a beam or lintel formed of cut brick laid in a radiating pattern, having a straight top and a soffit that may be either straight or with a camber.

14 Many of the archives of the university were lost or burned during wars and civil strife in last century. No architectural drawings or clear photos have been found to show the exact original design of the house.

References

- Australia ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites). 2013. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. Burra, South Australia: Australia ICOMOS.

- Han, Y., Y. Chen, and Q. Zhou. 2020. “Research on Detached Housing Construction Technology in Nanjing during 1930s: Baiziting–Fuhougang Residential Area as an Example.” International Journal of Architectural Heritage 14 (9): 1320–1340. doi:10.1080/15583058.2019.1607624.

- Harvey, D. C. 2001. “Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: Temporality, Meaning and the Scope of Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 7 (4): 319–338. doi:10.1080/13581650120105534.

- ICOMOS. 2011. The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas. Paris: ICOMOS XVII Assemblée Générale.

- ICOMOS Canada. 2008. Quebec Declaration on the Preservation of the Spirit of Place. Québec: ICOMOS Canada. doi:10.1017/S0940739108080430.

- Jiang, B. 2016. “Christian Colleges amid Political Changes: The University of Nanking’s Reorganization and Registration (1927–1928).” Journal of Modern Chinese History 10 (1): 19–34. doi:10.1080/17535654.2016.1168162.

- Leng, T., and C. Zhao. 2003. “Yuan Jinlin Daxue Laoxiaoyuan Jianzhukao [Discovery of the School Buildings in the University of Nanking].” Dongnan Wenhua [Southeast Culture] 3: 53–58.

- Leng, T. 2010. “Jinlin Daxue Xiaoyuan Kongjian Xingtai Ji Lishi Jianzhu Jiexi [The Analysis of Campus Form and Historical Buildings of University of Nanking].” Jianzhu Xuebao [Architectural Journal] 2: 22–25.

- Li, H. 2004. Zhongguo Xiandai Jianzhu Zhuanxing [The Transformation of Chinese Modern Architecture]. Nanjing: Southeast University Press.

- Liu, Y. 2011. “Categorization and Distribution of Verandah Style Architecture in China.” South Architecture 2: 36–42.

- Malpas, J. 2008. “New Media, Cultural Heritage and the Sense of Place: Mapping the Conceptual Ground.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 14 (3): 197–209. doi:10.1080/13527250801953652.

- Moore, C. 2011. “The Forgan Smith Building and the Great Court at the University of Queensland.” Crossroads 5 (2): 19–33.

- Perkins, F., and H. Architects. 1925. “The University of Nanking, China.” The American Architect 127 (2464): 55–66.

- Poor, J., and J. Snowball. 2010. “The Valuation of Campus Built Heritage from the Student Perspective: Comparative Analysis of Rhodes University in South Africa and St. Mary’s College of Maryland in the United States.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 11 (2): 145–154. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2009.05.002.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. New York, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203602263.

- Tang, K. 2004. “From Ruined Gardens to Yan Yuan—A Transformed Vision of the ‘Hinese Garde’: A Discussion of Henry K. Murphy’s Yenching University Campus Planning.” Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 24 (2): 150–172. doi:10.1080/14601176.2004.10435318.

- Tong, Q., L. Tang, and Q. Li. 2020. “Analysis of New Campus Planning for Wuhan University in the Early Republic of China (1929–1937).” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering (ahead-of-print). doi:10.1080/13467581.2020.1830777.

- Uzzell, D. L. 1996. “Creating Place Identity through Heritage Interpretation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 1 (4): 219–228. doi:10.1080/13527259608722151.

- Wheeler, W. R. 1937. John E. Williams of Nanking. New York, NY: Fleming H.Revell Company.

- Woodward, E. 2013a. “Building a Donor Base for College and University Libraries: Exploiting Archives as a Foundation for Development.” College and Research Libraries News 74 (6): 308–311. doi:10.5860/crln.74.6.8963.

- Woodward, E. 2013b. “Heritage Protocol at Florida State University.” Journal of Archival Organization 11 (1–2): 83–112. doi:10.1080/15332748.2013.884402.

- Xie, J. 2018. “Jinlin Daxue Diyiren Fuxiaozhang Wenhai’ En Suoji [Life Story of John Williams, the First Vice President of University of Nanking].” Nanjing Daxue Bao [Newspaper of Nanjing University], September 30, Accessed June12, 2021. http://nju.ihwrm.com/index/article/articleinfo/doc_id/2560928.html.

- Xie, Y., and P. Walker. 2021. “Chinese and Christian? the Architecture of West China Union University.” Journal of Architecture 26 (3): 394–424. doi:10.1080/13602365.2021.1897030.

- Zhang, R., P. Isola, and A. A. Efros. 2016. “Colorful Image Colorization.” In Computer Vision – ECCV 2016, edited by B. Leibe, J. Matas, N. Sebe, and M. Welling, 649–666. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46487-9_40.

- Zhao, C. 2007. “Lun Daxue Jianzhu Wenhua Zhong ‘Changsuo Jingshen’ de Queshi [Discussion on the Loss of ‘Genius Loci’ in Campus Buildings].” Zhongguo Gaodeng Jiaoyu [China Higher Education] 13: 72–73.

- Zhao, C. 2012. “University Museum: The Realization of Campus Spirit.” Urban Environment Design Z1: 164–165.