ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to investigate the correlation between gender and urban space. The tropes of Korean women illustrated by media and the changing urban structures influenced by women were examined, focusing on the Gangnam District of Seoul from the 1970s to the 1990s. We draw on insights from social-geographic theories to conceptualize the city as a social space formed by the experiences and relationships between individuals and to indicate how women have been excluded and represented through the gendered segregation of space since the modernization of Korea in the 1960s. My study argues about the tropes of “Gangnam-themed Women” who are portrayed as “speculators,” “influential customers,” “oversolicitous mothers,” and “women crazy about their appearance.” Gangnam women were framed as ideal females became they were the very first women to broaden their area of activity into public space with their financial powers. As they played a role in improving the social status of women and fostering Gangnam as a prospective area, an illusion was created that women’s rights had been fully achieved. This paper closes by exploring how present-day Korean women struggle against the fantasy of their social position to gain authentic women’s rights and space for women.

1. Introduction

Gender issue has become a major issue in today’s Korean society. After a misogyny hate crime occurred on May 17th, 2016,Footnote1 the movement for women’s rights gained more momentum and affected recent research on women, gender, and sexuality in South Korea (Jang Citation2017, 14–18). Korean architectural academia is no exception to this current growing interest in gender. With the positional progress made by Korean female experts in the architectural field,Footnote2 women have become a significant research subject on their own.

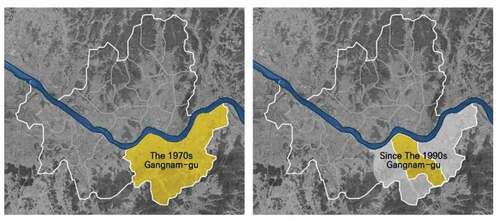

Figure 1. The transformation of the administrative district in Gangnam. This paper will focus on area within the current district lines because most factors that regulate the traits of Gangnam are found in this area.

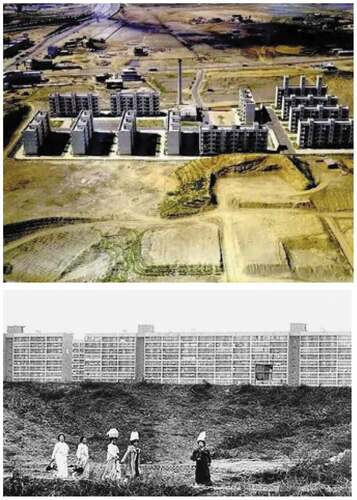

Figure 2. The Nonhyun-dong Apartment Complex was constructed in 1971 (Top), with the Daechi-dong Eun Ma Apartment Complex being constructed in the 1980s (Bottom).

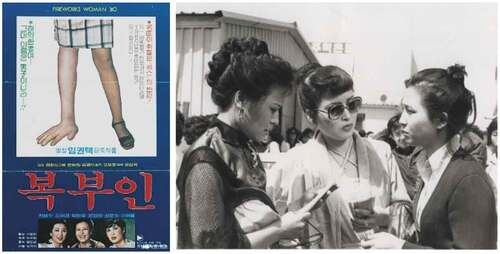

Figure 3. A poster and scene from the film BokBooIn directed by Im Kwon Taek. BokBooIn and their speculation was a severe phenomenon in Gangnam in the 1970s and was often mentioned in the news while commonly being criticized in movies as a dire social issue.

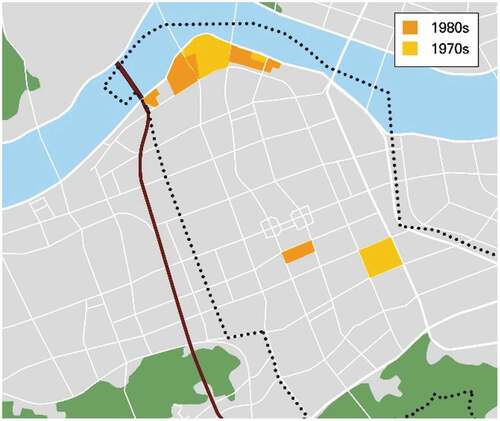

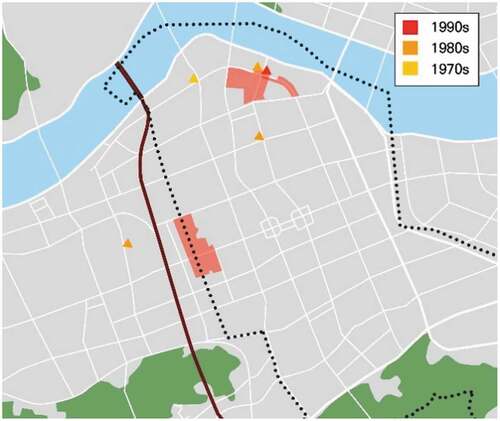

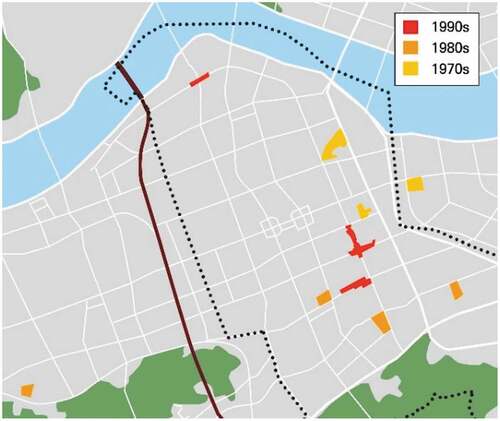

Figure 4. Spread of apartment complexes from the 1970s to the 1980s. Apartments build from the 1990s were excluded because they were not directly related to the speculation of BokBooIn discussed in this paper. Due to the success of apartment complexes in Gangnam, the apartment became the main type of residence in Korea and spread throughout the country in the 1990s.

Figure 5. In an advertisement for the Donghwa Department Store (the predecessor of the Shinsegae Department Store) in 1963, women were shown shopping with their husbands before they attained independent financial power.

Figure 6. Articles about the newly rising commercial area in Gangnam in the 1980s. The financial power of women led to the development of a new commercial area in Gangnam and triggered the move of shops, fashion industries and entertainment facilities to Gangnam from Gangbuk.

Figure 7. Shopping districts and department stores opening from the 1970s to the 1990s. Triangles indicate department stores including two which no longer exist today because of financial problems and structural collapse. With the development of Gangnam as a space of consumption, department stores and shopping malls were constructed at a rapid pace but were structurally and financially unstable.

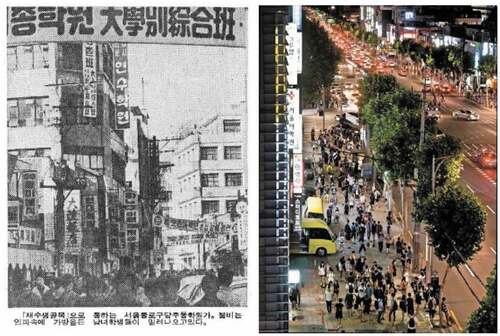

Figure 8. Cram schools usually opened in Dangju-dong, Gangbuk until the 1980s, but from the early 1990s, Daechi-dong, Gangnam grew into the most well-known private cram school zone in Korea.

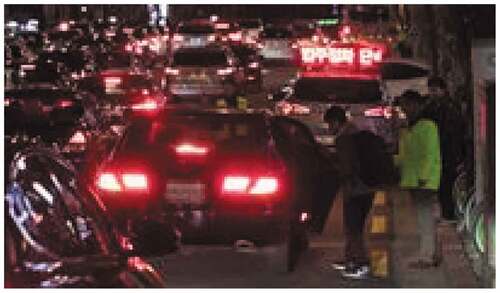

Figure 9. Curbside pick-ups are the reason for parking difficulties and traffic jams near the private cram school zone, which has long been regarded as a serious social problem for the area.

Figure 10. Prestigious schools and private cram schools opening from the 1970s to the 1990s. When the private cram school zones are evaluated in regard to apartment complexes, we can see that these educational zones have formed where prestigious schools and residential areas come into contact.

Figure 11. Luxurious city buildings for plastic surgery clinics that take on the appearance of sophisticated offices or luxury goods stores to subtly lower any repulsion about biased aesthetic values toward women’s bodies.

Figure 12. Advertisements for plastic surgery clinics inculcate distorted concepts for female bodies and beauty into women during everyday life in urban spaces such as subway stations, bus stops, etc.

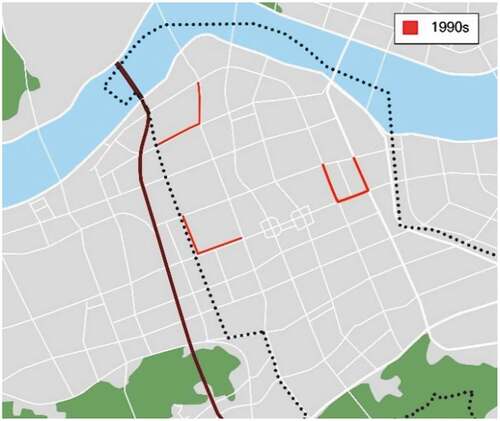

Figure 13. Plastic surgery district since the 1990s. After the craze for attaining a “feminine” appearance began, a fully-fledged plastic surgery industry that was previously scattered over the city converged intensively in Gangnam.

Figure 14. Hubertus House, Aldo van Eyck and Hannie van Eyck (1973–1981) (Left). Space Sallim, Units UA (2017–2020) (Right).

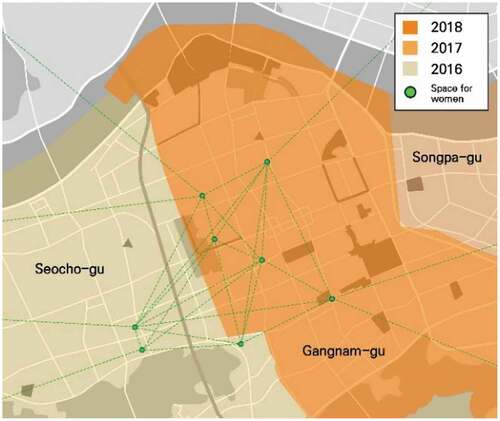

Figure 15. Emergence of space for Korean women and its current network. Different shades indicate the enforcement of a woman-friendly city in each borough of Gangnam. Spaces for women in the Gangnam area include facilities and institutions for multicultural families, working moms, sexual violence victims, etc. These organizations continue to expand from Gangnam to other parts of Seoul.

The recent women’s movement and social concern about feminism in Korea need to be understood through the social position of women in space. Images of Korean women have been formed differently according to the relationships between space, time, and political powers. In the middle of male-dominated relations in the city, women have been placed and replaced (McDowell Citation1999, 2). The pictured women who have been reproduced by dominant powers are one of the images most correlated with the city. Today, Korean women have begun to subvert this enforced framework that previously repressed and secluded them by pushing through urban space to contend their rights and identities. At this point in time, I would like to explore the correlation between gender and space in Seoul by focusing on changes seen in the Gangnam District and its representations of Korean women from the 1970s to the 1990s. Although Gangnam was developed according to a masterplan designed by male-dominated authorities and urban planners, Korean women in Gangnam have built up their own cultural context and social phenomena. Through my analysis on Gangnam women, I will observe how the changing social positions of Korean women influences and is influenced by the historical transformation of Gangnam.

2. Methodology

To investigate the correlation between Korean women and Gangnam in a theoretical framework, the social character of Gangnam in regard to women identities was explained by social geography.Footnote3 Then, four newspapers published from the 1970s to the 1990s, were examined to identify the changing representations of Gangnam women. The above temporal research scope was chosen because development plans for the Gangnam District were announced by the Seoul Metropolitan Government in 1970 and because the impact of Gangnam or what was perceived as Gangnam had completely spread throughout South Korea by the 2000s.

2.1. The theoretical framework

Space is concerned with identities affected by power relations (Choi Citation2009, 25–27). Massey’s contention that “thinking space in terms of stretched-out social relations confronts an important aspect of the spatiality of power” (Massey Citation1994, 4) lead to the matter of gender identities in society such as femininity and masculinity. Social identities appear variable and fluid in different places and times because people perceive their identities through subjective experiences happening in daily living spaces. Thus, social identities can be manipulated by power relations and material conditions. However, people also can confront and alter social identities constructed by the dominant powers in their everyday lives (Pain Citation2001, 4–5). Therefore, it is important to examine phenomena at an everyday scale to correlate gender and the socio-spatial world.

The city is one of the most reasonable scales used to observe everyday life. Urban ideology affects the concept of specific urban space in a certain society. As urban ideology is the basis for the preference, values, and desires of a particular public place, ultimately the capitalistic politics, economy, and culture of that society are underpinned by the chosen urban ideology (Park and Hwang Citation2017, 20). In terms of urban ideology, Gangnam is politically, socially, and economically one of the most powerful urban spaces in Korean society. The transformation process seen in Gangnam is connected to a distinctive urban desire and coveted image of the Korean middle class which differentiates it from the transformations seen in western countries (Park and Hwang Citation2017, 20–22). I chose to examine the Gangnam District because it is a significant place for both preconstructed images and prospective alternative representations of Korean women and because of its influence on other regions of Korea.

Gangnam’s influence can be seen in terms of gender, particularly in the tropes of Korean women. When conceptualizing the development of Gangnam, President Chung-hee Park pushed for national modernization in both public and private spaces. For this microscopic modernization in the family, ‘Korean women took over all domestic life such as households, purchasing homes, child rearing and education and were positioned as ‘economical and rationally spending subjects” (Jang Citation2017, 96–102) Housewives appeared as subjects with autonomous rights in private space whereas they were asked to be passive in public space. After this ideal image of Korean women was set, specific characteristics of Korean society such as paternalism, military fashion in society, and Confucian tradition affected the representations and roles of Korean women to their current state.

2.2. The archival materials

To investigate how Korean women were represented in Gangnam through the imagery of the ideal woman portrayed from the 1970s to the 1990s, I examined the following newspapers: The Dong-A Ilbo (first published in 1920), The Kyunghyang Shinmun (1946), Maeil Business Newspaper (1966), and The Hankyoreh (1988). Because these four newspapers have archived their past publications online, they are appropriate and accessible sources to investigate the changes in women and Gangnam. I searched for articles published from 1970 to 1999 that included the keywords “Gangnam” and “Women”. There were 2,653 articles containing the two terms, and I determined 108 materials as reasonable sources to look into the tropes of Gangnam women during the study period in question after excluding articles related to subjects who were outside the chosen research scope. Through my investigation, I proposed 4 characteristics of Gangnam women from 1970 to 1999 ().

Table 1. The tropes of Gangnam women and the number of related articles.

shows the changes in stereotypes chronologically during the 30-year study period. Gangnam women are described as real estate speculators in a majority of the material, and this image is sustained into the 1980s. However, most articles discuss Gangnam women as consumers in the 1980s because this was the decade in which Gangnam women started to become more active in public space with their financial power. This power can also be associated with an excessive interest in education. In the 1990s, Gangnam women also began to take an interest in their appearance, while broadening their role beyond their homes. The evidence for stereotypical figures is worthwhile to note because crimes objectifying the female body have become more common in conventional public places since then. These stereotypes still influence the Gangnam women of today and even women in other regions. Thus, it is likely that this will continue until the issues prompting the engagement of Korean women in social actions for women’s rights are resolved.

3. Gangnam, the beginning of the desired land

3.1. Reasons for developing the Gangnam District

The population of Seoul experienced an unprecedented growth triggered by a dictatorship authority in the 1960s.Footnote4 The military regime that seized power through the 1961 May coup enacted “Growth First”Footnote5 policies to justify its political legitimacy (Choi Citation2009, 69). With economic growth, people converged in Seoul to work and the city population rapidly increased. Although the elites of the government prioritized “building up an urban environment to house the overowing urban population” (Jung Citation2013, 51), housing shortages became a critical concern and many migrants settled in shantytowns which sprung up on vacant hillsides and riversides around the city, and these areas were considered a possible factor for social anxiety and disturbance (Park and Hwang Citation2017, 212–213). To overcome social unrest, methods were employed to expand urban boundaries and construct huge apartment complexes (Jung Citation2013, 51). Meanwhile, the president desired to change the public’s perception of the coup into a revolution undertaken for the good of the common people and he chose to do this by introducing modern lifestyles. The government tried to pacify the public by supplying housing with the enactment of the Housing Construction Promotion Act (Park Citation2013, 79–82). Gangnam was chosen as an appropriate site across the Han River to enlarge the administrative district of Seoul. The government took authoritarianism and developmentalism as its governance guidelines when developing Gangnam (Park and Hwang Citation2017, 209–211). These distinctive beginnings of Gangnam have impacted the following Gangnam-themed ways of thinking and living.

3.2. The construction of Gangnam

3.2.1. The coming of “Gangnam”

“Gangnam,”Footnote6 now summarized with images such as wealth, real estate, and fervor for education, was merely wetlands before being developed. In fact, Gangnam was part of Gyeonggi-do until its administrative district was transferred to Seoul in 1963 (Han and Kang Citation2016, 17–26). When politicians decided to disperse the urban functions of Seoul, there were two principal factors that facilitated the Gangnam project: the third bridge of the Han River (the Hannam Bridge) and the Gyeongbu Motorway. The 1969 completion of the Bridge and the 1970 opening of the Motorway caused land prices to surge in the Gangnam region (Seoul Museum of History Citation2011, 22). Then, the Seoul Metropolitan Government declared the New Town Development Plan for the Yeongdong area on November 5th, 1970 (Seoul Museum of History Citation2009, 22). Gangnam was the first development project for a New Town after Korea gained independence and it was consequently an experimental ground for diverse urban planning discourses between various subjects such as bureaucrats, urban planners, and architects. Furthermore, the development of Gangnam greatly influenced following projects in other urban areas (Youn and Jung Citation2009). More importantly over the urban system and infrastructure build up during this time, the thing that makes the Gangnam District “Gangnam” is the imagery that people have and consume about the district in their daily lives.()

3.2.2. Conciliatory policies for movement to the Gangnam District

The administrative and institutional advantages of the development of Gangnam and its disadvantages were already obvious in the 1970s. A variety of policies related to the movement of women were enforced through the government (Park and Hwang Citation2017, 205–207).

Firstly, the Seoul Metropolitan Government constructed apartments for the 360 families of its public officers in Gangnam. Then, 1350 municipal dwelling houses were added to provide housing as an incentive for the public to move (Seoul Museum of History Citation2009, 33–34; Seoul Historiography Institute Citation2012, 20). An additional “Article 16. Apartment district” was inserted during the 1976 revision of the Town Planning and Zoning Act, which became the foundation behind raising 16 apartment complexes in Gangnam (Youn and Jung Citation2009). It is indisputable that those apartments have been a subject of desire to most Koreans since their completion. Many women were ready to bet on the future real estate value of those apartments and this ambition was considered a major social phenomenon at the time. Secondly, the government restricted the development of Gangbuk to specific facilities in 1972, whereas the Gangnam area had the benefit of being exempt from new restrictions. Entertainment facilities, factories, universities, etc. were damaged financially by these new prohibitions, so they started to move to Gangnam where they could profit from tax reductions (Seoul Museum of History Citation2009, 32–33; Seoul Historiography Institute Citation2012, 21). Tax benefits gradually attracted other commercial facilities that boosted the consumption of Gangnam women. Lastly, the authorities relocated prestigious high schools and private educational institutes to promote the migration of students and their families. When the governing elites enforced this policy, they appealed to Korean parents who were willing to sacrifice their current comfort for their children’s education (Seoul Museum of History Citation2009, 34–36; Seoul Historiography Institute Citation2012, 25–29). The outstanding school zones of Gangnam remain one of the most powerful elements attracting families to the area today.

3.2.3. Ideal Korean women entering Gangnam

The dictatorship governed the public by the construction of women as superwomen, “Hyunmoyangcheo”Footnote7 who dedicated themselves to modernizing the nation in both public and private domains (Kim Citation2008). Under this strategy, female Koreans were pressured to take responsibility for purchasing real estate and increasing property value while also maintaining family households (Jang Citation2017, 101–102). Women were expected to have a twofold attitude toward life by pursuing modern lifestyles and material desires while adhering to traditional values (Chung Citation2009). The Gangnam apartments were promoted as the most idealistic place to fulfill the duties and desires of these women. Housewives were thought capable of handling almost all tasks, demands, and needs within the apartment complexes which incorporated the concept of a Residential Neighborhood (Han and Kang Citation2016, 69). Korean women who had previously limited themselves to just child rearing and domestic chores started to concern themselves with consumption such as interior design and other hobbies that could be done within their limited space, the household (Kim and Kim Citation2008). It was as if they were asked to take up a new position as “the subject of consumption.” It could be argued that Korean women began to raise their social position through financial power after becoming residents of the Gangnam area.

4. Who are Gangnam-themed women?

4.1. BokBooIn and speculation in Gangnam

After the Hannam Bridge was completed, the land value of Gangnam skyrocketed. With the rapid increase in property investment and construction of the Apgujung Hyundai Apartments in 1975, property speculation moved from agricultural land to apartment flats. From the 1970s to the 1980s, women in Gangnam were illustrated as “Bokbooin” which indicated upper-class women who speculated in real estate.()

The term, “Bokbooin” first began to appear in newspapers in 1978. Gangnam women were introduced as a new social stratum who made fortunes by investing in apartments. However, a male-dominated perspective was reflected in how two types of Bokbooin were categorized: women could be either the smart Bokbooin or the erratic Bokbooin. Smart Bokbooins purchased apartments and then took a break from further speculation following their husband’s advice whereas erratic Bokbooins ruined their family fortunes by immoderate speculation or by being cheated by young male real estate agents (Unknown Citation1978a, 3, Citation1978b, 3). However, the archival material confirms that Gangnam women did attain economic power to a certain extent at this point, because some were able to invest independently without their husband’s permission. After the middle 1980s, Bokbooins changed the main target of their speculation to stocks. Again, articles stressed their deficiency compared to men and explained the high investment success rate of women as coincidence due to female delicacy and sensibility (Kim Citation1986a, 11; Hong Citation1986, 13; Unknown Citation1987b, 6; Park Citation1989a, 10; Kim Citation1987, 3).()

Gangnam women were represented as gullible and greedy even though they had been socially pushed into their new responsibilities of buying the family home, a given under the national stratagem for modernization. However, newspapers published from the late 1970s started to show women as subjects of the domestic economy instead of just housekeepers (Choi Citation2015). This changing tendency signifies that women gradually gained their rights by escaping spatially from the domestic space and ideologically from the patriarchy. Gangnam women expanded their social activities into the male-dominated city riding on their newfound financial power. The Bokbooins were the beginning of “Gangnam-themed women” that most Korean women would later on desire to be. This was the starting point for Gangnam, which was first created by androcentric power and completed by the financial investment activities of women.()

4.2. Influential consumers of Gangnam

Gangnam was the place where major changes occurred to the consumption culture of Korea under modernization and industrialization (Park and Hwang Citation2017, 81–82). With tax reductions being given for relocation to Gangnam, many entertainment businesses moved to Gangnam from the 1970s to the 1980s. The initial consumer culture in Gangnam was formed in an androcentric way. Women who worked in the entertainment industry ended up in Gangnam by the forced policy of the authorities, but the commercial and entertainment facilities were mostly built for men.()

From the early 1980s, Gangnam women were able to enjoy hobbies such as swimming, tennis, and floral arrangements after their children entered primary school. Because women became bigger consumers, saunas and massage parlors for women appeared with luxurious interiors (Kim Citation1983b, 3). In articles, housewives in Gangnam suddenly become objects of denunciation by being positioned at the opposite side of ideal Korean women who were regarded as being virtuously frugal (Kim Citation1989a, 7, Citation1989b, 5; Lee Citation1990, 15; Park Citation1989, 8; Unknown Citation1989, 9). Ironically, despite this condescension, the government promoted the economic power growth of Gangnam women to generate “a city of consumption”. Urban space also contributed to reinforcing the stereotype of Gangnam women as significant consumers. In the late 1980s, high-class dress shops started to move to Gangnam from Myung-dong which had been the traditional fashion district of Seoul (Unknown Citation1987a, 10). With the spatial transformation of the city, the layout of department stores were also adjusted to appeal to Gangnam women. The number of floors for women’s apparel was increased to cover two levels at the Apgujeong Hyundai Department Store (Jung Citation1988, 13). The perception of Gangnam altered from the decadence and pleasure of men to the consumption and extravagance of women. This trend was a result of women being regarded as more influential consumers then men.()

Despite the economic recession in the 1990s, the commercial, medical, and financial industries in Gangnam established high-end strategies architecturally and institutionally to attract Gangnam women who want to be treated differently from other social classes (Hong Citation1996, 7; Park Citation1996, 27; Unknown Citation1997, 9). Under democratization, individualism, and globalization in the late 1990s, women broadened their boundaries by participating in production and consumption. To note, the next generation of Gangnam women were the daughters of the Bokbooins and highly educated. They expected to actively participate in society. This next generation started to define themselves as individuals and citizens through work and did not identify themselves as mothers who sacrificed all for the family (Shin Citation1998). Korean women who were influential consumers became influential producers of architecture and urban space as well.()

4.3. Gangnam women as mothers being oversolicitous to sincere

After the Korean War, the former elite had considerably collapsed, and education become the main way of climbing up the social ladder. To do this, a person needed to graduate from “a so-called prestigious university” to reach a high social position and attain wealth. After middle school entrance examinations were abolished in 1969, the fever for “prestigious schools” transferred to high schools as they became the gateways to entering prestigious universities (Seoul Historiography Institute Citation2012, 25–29).() This phenomenon was evident in the high number of parents following the schools which relocated to Gangnam. With the first relocation in 1976, the era of Gangnam education began. The fact that most people who lived in Gangnam were families with school-age children was noticed by the media. Apartments were generally resold at a profit as soon as they were put on the public market with the last-end buyers being parents. For these parents, the renown school districts were the main attraction of Gangnam rather than future real estate profits (Kim Citation1983a, 5). In the late 1980s, it was quite common to see mothers chauffeuring their children to private cram schools. Gangnam mothers achieved wealth through their husbands, but were not allowed to do other constructive outside work for their own identities. They ended up focusing on their children and pouring their passion into child rearing (Lee Citation1989, 15; Kim Citation1990, 13). All this was thought to cumulate into the oversolicitous and overprotective concern for children in Gangnam.()

Today, Gangnam is described as the “Gangnam educational special district”. In Gangnam, one of the most male-dominant urban space economically and politically, women powerfully influenced the urban structure of Gangnam through the education industry. Every big city in Korea now has a similar “Gangnam-style” educational district. Even when there are down turns in the economy, the high home prices of the private educational district are sustained, showcasing the “Korean-style” relationship between cram schools and apartments seen in Gangnam (Park and Hwang Citation2017, 39–40; Han and Kang Citation2016, 289–300). These educational districts are rooted in the desires of Korean mothers who think of themselves as “Gangnam-themed women.”()

4.4. Women’s bodies and femininity in Gangnam

Under capitalism, urban space compels individuals to commercialize their bodies despite the human body being the most microscopic territory that people can have (Choi Citation2009, 57). Capitalism constantly reproduces certain femininity and masculinity traits. Then, these traits are inscribed in bodies by producing a craving for proper appearance (Mitchell Citation2000, 472). In the 1980s, a new patriarchal principle about intimacy for “a beloved wife” and “a successful husband” appeared. This kind of rationale reinforced men to be more masculine and women to be more feminine (Jang Citation2017, 109–111). Femininity regulating women’s bodies tended to be represented in two ways: charming schools and proper appearance with a “female-like” personality. Since the middle 1980s, lectures for young women that taught cooking, manners, marriage, and parent education started to become prevalent in Gangnam (Kim Citation1985, 7). In the 1990s, “charming schools” were popping up all over Gangnam. The schools trained women to have a more physically feminine perspective (Kim Citation1992, 25, Citation1993, 9; Lee Citation1992b, 11). This trend spread to other regions, and outer appearance was considered a vital trait of competitiveness by both society and women themselves (Lee Citation1992a, 11). Meanwhile, women’s bodies were framed in what was considered desirable and feminine. In the Gangnam District, housewives kept themselves slim and wore showy and flattering dresses according to the standardized beauty of society (Kim Citation1986b, 6). The tendency to objectify women’s bodies intensified with the appearance of the ‘Orange-jok.Footnote8 The objectification of women in public places has further provoked the voyeuristic “peeping Tom” crimes with hidden cameras since being acknowledged as a crime in 1997.() ()

Under post-capitalism, women’s bodies were designed and improved to fit the ideal and desirable feminine image through diet, exercise, and plastic surgery (McDowell Citation1999, 37). Women’s bodies were reproduced by the merchandising logic of the market and of the patriarchy. However, women’s bodies as a new type of capital were transformed from a passive form for birth and domestic chores to an active form of self-directed transformation (Jang Citation2017, 125–126). As Gangnam women have encountered this modification, beauty industries and plastic surgery clinics have become imbedded into the urban tissue of Gangnam reinforcing these representations of a woman’s body.()

5. Korean women from the boudoir to the public

5.1. Gangnam-themed women’s power and influence

Korean authorities assigned ideal feminine and gender roles to women to achieve economic growth and for socio-political stabilization. However, Korean women broke free from these preconceptions to develop individual lives with their new-found financial powers discovered by entering Gangnam.

Women in Gangnam established the trope of “Gangnam-themed women” that was desired by women in other parts of Korea. This stereotype has influenced the overall gender identity of Korean women. As Gangnam-themed women symbolizes women who consume and enjoy life based on their financial power, many women who dream of reaching the top of the social ladder accumulate their own financial power by participating in production in public space. Especially, women who reaped the benefits of their mothers’ passion for education tend to have high self-esteem and strong inner image of themselves as individuals. It could be argued that they are not afraid of struggling to gain their rights and to discover their own gender identity.

Gangnam women have also changed the organization and structure of the city. For example, the consumer culture and the interest in outward appearance in the 1990s caused plastic surgery clinics to pop up not only in Gangnam but throughout Seoul (Han and Kang Citation2016, 251). The craze for cultivating the appearance of an upper-class Gangnam woman, a woman in accord with the granted femininity and gender roles in private space, spread to other women in public space. Advertisements for cosmetic surgery are now openly displayed in public places. Furthermore, with the buildings of the plastic surgery clinics being designed like luxury goods stores and decorated with state-of-the-art products, women have deluded themselves into consuming beauty procedures like luxury items. Gangnam has been cultivated from architecture to urban space by Gangnam -themed women.

During the period of economic growth, women in Gangnam saw themselves as role models for contemporary females and these women wanted to reclaim women’s rights, dignity, and high-class femininity. Through their assertiveness, various female leaders appear today in the post-capitalist society. Although Gangnam women were negatively illustrated by the media, they have played a significant role in creating the local identity of Gangnam. Gangnam women were not mere peripheral beings; rather they cultivated the district into the Gangnam of today.

5.2. Urban space derived from women’s rights

5.2.1. Illusions of women’s rights in Korea

As the elevated social status of Korean women is based on past profits from real estate speculation and high education expenses, doubts must be raised about its sincerity. Although Korean women have attained social status, the contemporary representation of womankind is confined by capitalist and political powers. Many Korean women of today possess purchasing power and the capability to get a job, however, the height of supposed female emancipation coincides so perfectly with consumerism (Power Citation2009, 1). Power points out that “what looks like emancipation is nothing but a tightening of the shackles” (Power Citation2009, 2).

Under spatial segregation, public space has been highly evaluated as a place for paid production while private space has been underestimated as a place for unpaid reproduction (McDowell Citation1999, 73–75). Public space is portrayed as an ideal place that women should enter, but private space is regarded as a suppressive place that women should escape from. Thus, Korean policies for gender equality had a primary goal of helping women enter public space. The government and media generated illusions about Korean women’s rights by reporting successful examples of women who enter the preexisting power stratum (Ahn Citation2011). However, the actual number of women who penetrate the male-dominated society is a tiny minority. Most female workforces are positioned in low-quality workplaces that create a “feminized ghetto” (Sook Young Ahn Citation2012).

Gangnam-themed women’s social activities, with a minority of influential women, have gratified the fantasy of Korean women’s rights. There is no doubt that the financial power of Gangnam women changed the social position of Korean women. However, the amount of Gangnam women’s rights and independent lifestyle sustained under the social system of androcentrism and sexism were limited, and Gangnam reinforced the existing system and idea through its spatial structure and formation. Authentic Korean women’s power and rights can be reached when the established system including urban space is subverted. Thus, it is difficult to assert that Korean women’s rights are accomplished without changing urban space gender-equally and without recognizing the exclusion of women in the city.

5.2.2. Struggles against female tropes in public space

The streets possess the possibility of being a location for political activities and concord with strangers. Public space is “a site of authentic political action” and “a place of inclusiveness where people can come together and therefore are inherently democratic spaces” (Valentine Citation2001, 171). ‘The city’s streets offer opportunities for genuine social interaction, resistance, and disorder, for play rather than work and for (social) use rather than (economic) exchange. In the streets, people can reclaim a renewed urban society and their “right to the city” (Harvie Citation2009, 52). Changing urban space is possible by socially and challengingly resisting through the practices of urban performativity (Harvie Citation2009, 54). Endeavors to change the streets do not alter enforced stereotypes and gender identities at once, but they can tackle hegemonic understanding and gendered customs.

After the misogyny hate crime in Gangnam, similar anti-hate movements were started by artists, feminists, and the public. Right after the murder, people commemorated the victim by putting up memos on Exit 10 of Gangnam Station. Through this performance, many women shared the experiences and fears that they face every day everywhere. Beyond the murder crime, they asserted gender equality and women’s rights with the enactment of proper laws and the realization of justice in the judicature (Kim and Suk Citation2018). Through this interaction between different members of society, Gangnam could be argued as Arendt’s “public realm” that people can build a consensus through the speech and action with the plurality (Arendt Citation2019, 101–132). In Gangnam, Korean women continue to make a “space of appearance” which comes into a space of political freedom and equality by acting in concert through the medium of speech and action (CitationStanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

Today, Korean women often march and protest on the streets to define their identities and to protect their rights. Their performative practices show that the place to change hegemonic understanding is the “being right here” street, not the “being far away” assembly or other authorities. Under the menaces of capitalism and neoliberalism, Korean women are generating “a space of solidarity” (Ahn Citation2012b) during the process of organizing their struggles. These successive performative practices alter individuals into “social agents”, and their actions have changed “our lives, destinies, and urban society” (Harvie Citation2009, 66). Urban space “Gangnam” and “Korean women” in Gangnam are creating new relationships on another level.

5.2.3. Space of appearance for Korean women

The movement of Korean women to fight for their own rights and space have led to the emergence of alternative spaces for women with supportive policies. The spatial map and network for women’s spaces have been constructed in and near Gangnam. Within the business environment of Gangnam, Korean women have been able to work and act beyond simple labor based on their gender role to achieve real power and actual rights. According to Arendt, labor, work, and action are closely connected with the universal conditions for human existence.Footnote9 Korean women who spent their whole lives as mothers and wives can now work to bring other meaning to their lives and act to realize and recognize their own identities.

As Korean women’s rights have strengthened, the tropes of Korean women have diversified from the limited images of sacrificial mothers to various subjectivities such as single mothers, working moms, and women who do not want to get married, with Gangnam being developed as a place for their participation in society. For example, the Women Enterprise Supporting Center opened in 2007 to promote the activities of female entrepreneurs and to aid them in establishing businesses on their own merits (Women Enterprise Supporting Center Citation2007). Seoul Woman Up which is a center supporting women’s jobs, education, and welfare in the eastern area of Seoul was founded in 2014, and a platform was developed to help women who want to start their own business with little capital (Seoul Women Up Citation2022). These places based on the business network of Gangnam are putting in efforts to support women in diverse ways from specialized fields for business to auxiliary parts such as childcare and counselling. The biggest support center for female entrepreneurs is Space Sallim which has operated since 2021. Space Sallim targets gender equity at work and extends its help to any citizen who is struggling to balance work and family (Space Sallim Citation2020). These institutions are now physically present in all parts of Korea, and their supportive scope and recipients have been broadened to other genders and sexualities. The changing women’s tropes that Korean women obtain continue to transform social systems and cognizance and from these efforts, women’s collectivity has finally emerged.

The movements of marginalized subjects can precipitate great transformations in society. Aldo van Eyck who actively participated in architecture for the public to include women and children reintroduced timeless elements ignored by others into the Modern movement. When explaining Hubertus House which was built for single mothers and their children, Van Eyck stressed the importance of choice such as experiential variety and opportunities that a single flat plane can offer against Modernism that achieved more alienation than liberation. Through architectural elements he encouraged residents to take part in the life of the House and society. Architecture can create new and catalytic relationships between isolated activities,Footnote10 and Space Sallim was the first architectural function for women’s space that went beyond previous programmatic support.() More architectural aids are expected throughout cities in Korea. Gangnam women’s struggles since the 1970s have shaped the characteristics of Gangnam and its spatial features have become a cornerstone from which the women’s space seen in today’s Korea has been built. Korean women are claiming their right to the city by creating their space and painting it with their collectivity.()

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I tried to correlate gender and urban space in a modern city focusing on the changes that occurred in the Gangnam District of Seoul from the 1970s to the 1990s. During this time, Korean women were granted certain gender roles in private space to contribute to national modernization. However, women started to alter preconceived notions and broadened their area to public space after entering Gangnam. Although Gangnam was initially formed by male-dominated powers, women found ways to create their niches in this space. Gangnam women helped to rebirth Gangnam as a desirable place that attracted the middle and upper class. However, in doing so, Gangnam women were represented negatively with terms such as “speculation”, “obtrusion”, “extravagance”, and “grooming” by media and society. Gangnam is the place where recognition of women’s rights and identities grew, and Gangnam women were the driving force behind the current preconceptions people have about urban space in Gangnam. Although Korean women gained power and social status, the imagery of women’s financial power consuming public space created the illusion of women’s rights being achieved. In Korea, women’s rights and gender equality have not even reached moderate global standards. Nevertheless, the public space is changing into a place for political issues that showcase the struggle to convey women’s contentions to the public and authorities and Gangnam has become the starting point for space to emerge as a foundation for Korean women’s collectivity. Korean society is working its way towards gender equality and women’s safety and rights.

This paper tried to study the issue of women’s rights and social position by focusing on the relationship between changing women’s tropes and urban space. However, the study did not cover low-income female workers and bar hostesses who are important subjects in terms of women’s rights as well as in the modernization of Korea. The interrelationship between other classes of Korean women and urban space needs to be studied in following studies to grasp the full problem of gender inequality that runs throughout the city.

Disclosure statement

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Soojin Cho

Soojin Cho is now a lecturer at Chung-Ang University of Architecture in Korea. This article is based on her Master’s research at The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL.

Hayub Song

Hayub Song is now a professor at Chung-Ang University of Architecture in Korea.

Notes

1 A young woman was attacked and killed on 17 May 2016 in a public restroom of a karaoke building near Gangnam Station by a male stranger. The attacker confessed that he targeted the female victim based on delusions of persecution from women, imagining that women ignored and abhorred him.

2 OPENHOUSE SEOUL began the program, “W Interview” in 2018 that talks with Korean female specialists in architecture to record them and their works countering the past in which women were excluded from the male-dominated architectural history of Korea. CitationOPENHOUSE SEOUL, accessed on 21 June 2021, https://www.ohseoul.org/2019/interview/w-interview.

3 Social geography which is as “the study of social relations and the spatial structures that underpin those relations”, Johnston et al., (2000, 735) cited in Valentine (Citation2001, 1).

4 In Korea, capitalism was promoted nationally rather than by each city independently. The city was organized as a material environment for capitalism and a spatial center for the political authorities. Seoul encases these characteristics since the 1960s when its economic growth and urbanization was radically propelled by the dictatorship regime. Choi (Citation2009, 59–61).

5 This can be noticed in the president’s inaugural speech on December 17th, 1963: “The fundamental objective of the government is national modernization, and economic growth is the overriding target in the modernization projects” Ahn (Citation2012a).

6 The word “Gangnam” literally means “the south part of the Han River” and administratively “Gangnam-gu (ward)”. Gangnam-gu makes up the scope of this study.

7 The concept of “Hyunmoyangcheo” was introduced by Japan as a modern ideology for the education of women after Korea first opened its ports to the outside world. The main theme of “Hyunmoyangcheo” discourse is that women can be a responsible member of society by taking care of their households and family members in the domestic space while men perform waged work in the public space. At first, “Hyunmoyangcheo” defined new women who gained benefits from modern education, but after the 1930s, it identified traditional women as such in comparison to “modern girls” who were represented as bad women blindly submitting to the decadent culture of the western world., CitationEncyclopedia of Korean Culture, accessed on 28 June 2021, (http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%ED%98%84%EB%AA%A8%EC%96%91%EC%B2%98&ridx=0&tot=4).

8 “Orange-jok” was the term for young men in their 20s who enjoyed an affluent lifestyle due to the wealth of their parents in Gangnam. They consumed luxury items and drove expensive imported cars when they tried to attract women. Kim and Choi (Citation2009, 199).

9 According to Arendt, labor is related to the survival of individuals and species. Work which is the product or artifact of human offers continuity and perpetuity for finite lives. Action creates conditions of history insofar as action participates in establishment and preservation of political organization. Arendt (Citation2019, 85).

10 Street urchin: Mothers’ House (Amsterdam) by Aldo van Eyck, The Architectural Review, accessed on 16 April 2022, https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/street-urchin-mothers-house-amsterdam-by-aldo-van-eyck.

References

- Ahn, S. Y. 2011. “Understanding the Relationship between Gender and Space from a Gender Equality Perspective.” PNU Journal of Women’s Studies 21 (2): 7–37.

- Ahn, C. M. 2012a. “A Divided Korea and Urban Structures of Seoul under the Cold War.” Hyangto Seoul, 1(81): 161–205.

- Ahn, S. Y. 2012b. “Gender, Space, and Politicization of Space: A Theoretical Sketch.” PNU Journal of Women’s Studies 29 (1): 157–183.

- Arendt, H. 2019. The Human Condition. Translated by Jin Woo Lee. Paju: Hangilsa.

- Buchanan, P. 1982 The Architectural Review. Accessed 16 April 2022. https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/street-urchin-mothers-house-amsterdam-by-aldo-van-eyck

- Choi, B. D. 2009. A Labyrinth of Urban Space. Seoul: Hanul press.

- Choi, Y. S. 2015. “Commercialization of the Korean Press Industry and the Gender Politics of Women’s Pages in the 1960s~1970s.” Journal of Korean Society for Journalism and Communication Studies 59 (2): 287–323.

- Chung, Y. H. 2009. “Popular Magazines and Composition of Modern Urban Life in the 1960s.” Journal of Science & Media 9 (3): 468–509.

- Han, J. S., and H. Y. Kang. 2016. The Birth of Gangnam. Seoul: Mizi books.

- Harvie, J. 2009. Theatre and the City. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hong, K. H. 1986. “Rapid Increase in the Number of Housewives with Professional Knowledge.” Dong-A Ilbo, October 23.

- Hong, K. Y. 1996. “We Serve Only Female Customers.” Maeil Business, June 19.

- Hong, Y. H. 2017 Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Accessed 28 June 2021. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%ED%98%84%EB%AA%A8%EC%96%91%EC%B2%98&ridx=0&tot=4

- Jang, M. H. 2017. 70 Years of Korean Women·Family·Social Changes. Sungnam: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

- Jung, S. K. 1988. “Changes in Commercial Supremacy with the Springing up of Department Stores.” Maeil Business, August 19.

- Jung, I. H. 2013. Architecture and Urbanism in Modern Korea. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press.

- Kim, H. J. 1983a. “Speculation in Gangnam Due to Prestigious School Zones.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, February 11.

- Kim, K. M. 1983b. “Where Does the Money Flow <21> Corporatization of the Sauna.” Dong-A Ilbo, May 24.

- Kim, S. D. 1985. “Private Lessons for Brides-to-Be.” Dong-A Ilbo, April 5.

- Kim, S. W. 1986a. “More Housewives Investing in Stocks.” Dong-A Ilbo, April 15.

- Kim, Y. K. 1986b. “Changing Fashion Trends of Apartment-Dwelling Middle-Aged Housewives.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, February 19.

- Kim, S. H. 1987. “The Changing Cultural Landscape of the Stock Market (3) Female Investors.” Maeil Business, March 16.

- Kim, H. P. 1989a. “Economy, Challenges, and Ordeals (9) the Trend of Excessive Consumption.” Dong-A Ilbo, December 22.

- Kim, W. J. 1989b. “Overspending Leads to Avarice.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, October 27.

- Kim, J. K. 1990. “Tottering Families <2> Adrift Housewives.” Dong-A Ilbo, May 3.

- Kim, S. R. 1992. “Beauty Being Created through the Charming School Boom.” Maeil Business, March 5.

- Kim, S. D. 1993. “The New Generation (27) Women Who are ‘Half of Humankind’.” Dong-A Ilbo, October 24.

- Kim, S. J. 2008. “The Invention of Tradition and the Nationalization of Women in Postcolonial Korea Imagery of Shin Saimdang as a Good Mother and a Good Wife.” Journal of Korean Social History Association. 1(80): 215–255.

- Kim, K. R., and G. H. Choi. 2009. Dictionary for Pop Culture. Seoul: Hyunsil Munhwa press.

- Kim, J. H., and Y. C. Kim. 2008. “Cultural Discourses on the Modern Home in Women’s Magazines from the 1960s through the 1970s.” Journal of Korean Women Communication Association. 1(10): 109–155.

- Kim, M. Y., and J. H. Suk. 2018. “Two Years after the Gangnam Station Crime, ‘We Do Not Stop’ Protests despite Heavy Rain in 7 Cities.” The Hankyoreh, May 18.

- Lee, S. C. 1989. “Middle-Aged Mothers (5) Depression and Stress Due to Excessive Competition at College Entrance Examinations.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, October 31.

- Lee, B. G. 1990. “Overspending of Rich Housewives in December.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, December 22.

- Lee, G. K. 1992a. “Charming Schools Opening in the Poor Village.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, October 9.

- Lee, J. T. 1992b. “Prospective University Students and Booming ‘Charming Classes’.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, February 28.

- Massey, D. 1994. Space, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- McDowell, L. 1999. Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Mitchell, D. 2000. Cultural Geography. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- OPENHOUSE SEOUL. Accessed 21 June 2021. https://www.ohseoul.org/2019/interview/w-interview

- Pain, R., ed. 2001. Introducing Social Geographies. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Park, H. S. 1989a. “Catch the Handbag Troops! Emergency in the Stock Market.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, October 23.

- Park, J. M. 1989b. “Imported Luxury Items at Department Stores Fuel Overspending.” The Hankyoreh, July 29.

- Park, G. Y. 1996. “Sumptuous Hospitals in Gangnam.” The Hankyoreh, November 20.

- Park, C. S. 2013. Apartments: Society Dominated by Public Sarcasm and Private Ardor. Seoul: Mati Press.

- Park, B. G., and J. T. Hwang, Eds. 2017. Creating Gangnam, Imitating Gangnam. Paju: Dongnyok Press.

- Power, N. 2009. One Dimensional Woman. Hants: O Books.

- Seoul Historiography Institute. 2012. Relocation of the Prestigious Schools of Old Seoul to the New Gangnam. Seoul: Seoul Historiography Institute.

- Seoul Museum of History. 2009. Gangnam Seen Through Stories. Seoul: Seoul Museum of History.

- Seoul Museum of History. 2011. 40 Years of Gangnam, Exponential Growth. Seoul: Seoul Museum of History.

- Seoul Women Up. 2022. Accessed 29 December 2021. Accessed on 13 April. https://dongbu.seoulwomanup.or.kr/

- Shin, K. A. 1998. “From the Embodiment of Sacrificed to Desire.” Journal of Women and Society. 1(9): 159–180.

- Space Sallim. 2020. Accessed 13 April 2022. http://www.spacesallim.or.kr/

- Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Webpage. 2019. Accessed 29 December 2021. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/arendt/#ActFrePlu

- Unknown. 1978a. “The Troops of BokBooIn (1).” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, February 14.

- Unknown. 1978b. “The Troops of BokBooIn (2).” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, February 16.

- Unknown. 1987a. “Myeong-Dong, the Transformation of the Shopping District.” Maeil Business, September 3.

- Unknown. 1987b. “When It Comes to Stock Investment, Gangnam Housewives are the Best.” The Kyunghyang Shinmun, March 18.

- Unknown. 1989. “Worries of Spending Sprees.” Dong-A Ilbo, September 9.

- Unknown. 1997. “Nine Million Won to Dress like Cinderella at the Ball.” The Hankyoreh, June 2.

- Valentine, G. 2001. Social Geographies: Space and Society. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Women Enterprise Supporting Center, 2007. Accessed 13 April 2022. http://www.wesc.or.kr/

- Youn, E. J., and I. H. Jung. 2009. “A Study on the Formation of Urban Space in the Gangnam Area and an Urban Discourse on City Planning in the 1960s.” Journal of Architectural Institute of Korea 25 (5): 231–238.