ABSTRACT

Traditional houses and villages are a cultural asset of the West Sulawesi region and should be passed down to future generations to preserve the community’s identity. The Orobua settlement, located in Mamasa Regency, West Sulawesi Province, is a settlement that had maintained its traditional landscape until the 1990s. However, since the mid-2000s, most traditional houses have either been modified or replaced with modern ones. This paper examines the cultural heritage of the Orobua settlement and suggests strategies to preserve its traditional landscape. Source data were obtained through a literature review, field survey, and interviews with residents.

1. Introduction

The conservation of historical heritage often begins as an antithesis to modernization. Case in point: the United Kingdom, where the Industrial Revolution began, is also where the conservation movement originated in the 19th century. The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty (National Trust), a volunteer organization aiming to promote the protection of historic buildings, was founded in 1895. It has since worked towards building social consensus on the significance of historical heritages for over a century. Today, the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England (Historic England) states that “it is the government’s overarching aim that “the historic environment and its heritage assets should be conserved for the quality of life they bring to this and future generations” (CitationHistoric England n.d.). It also defines conservation as a process; “maintaining and managing change to a heritage asset in a way that sustains and where appropriate enhances its significance.” Indeed, absolute physical preservation of a building or site may be very rare except for the most sensitive and important buildings. “The vast majority of our heritage assets are capable of being adapted or worked around to some extent without a loss of their significance”, and conservation of historic heritages could potentially be “a catalyst for regeneration in an area, in particular through leisure, tourism, and economic development.” In summary, the purpose of preserving historic buildings is to pass on their cultural value to future generations. For this purpose, it is considered acceptable to modify them to the extent that their cultural value is not compromised. In some cases, cultural value can be linked to economic value through the promotion of tourism.

In Indonesia, there has been a growing awareness of the need to preserve traditional architecture. Indonesia’s traditional artifacts are in danger of disappearing due to changes in lifestyles caused by rapid economic growth and the introduction of modern technologies. In 2010, the Indonesian government amended the Law on the Protection of Cultural Heritage to promote the protection of cultural heritage groups, including groups of buildings, village settlements, and related natural features, expanding its previous policy of preserving cultural heritage alone. The law clearly states that the protection of cultural heritage is the basis for cultural prosperity, which is achieved through developing and utilizing a region. One example is the Revitalization of Traditional Villages (Revitalisasi Desa Adat) project, led since 2013 by the Directorate of Belief in God and Tradition (Direktorat Kepercayaan terhadap Tuhan YME dan Tradisi) to restore traditional architecture in a settlement on Nias Island. However, the project’s scope is limited to public buildings (Ono et al. Citation2019).

Japan has had a similar experience. After WWII in 1945, the country experienced a period of reconstruction from the war damage and rapid economic growth during the 1950s and 1960s, and traditional townscapes were rapidly replaced by modern buildings. Consequently, it became critical to develop a framework for the conservation of the country’s historical heritage and to make systematic efforts to ensure its conservation. As a result, the “Preservation Districts for Groups of Historic Buildings (PDGHBs)” regulation was established in 1975. Its aim is to preserve historical villages and townscapes. The following year, in 1976, Shirakawa-go and Tsumago-juku were designated as the first group of historical heritage buildings. Shirakawa-go was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995. Many of the designated districts are in remote areas where means of transport are limited and have been left behind by modernization as a result. Shortly before the conservation movement, the Japan National Railways (now JR) launched the “Discover Japan” campaign to attract tourists after the Osaka World Exposition (1970). “Discover Japan” was a nationwide campaign based on the concept of “discovering Japan and rediscovering oneself.” Some of the designated districts for PDGHBs became popular tourist destinations. New jobs were created to meet the demand of visitors, and the younger generation of the local community has since returned to participate in the maintenance and management of traditional houses, such as the replacement of thatched roofs in Shirakawa-go.

When it comes to the conservation and restoration of old wooden buildings, the emphasis is on authenticity. The original materials are retained as far as possible, and in case of partial damage, new wood of the same species that has been processed using the original construction methods is used. Japan also has a great deal of experience in the preservation and restoration of old wooden buildings. Horyuji Temple in Nara was originally built in the seventh century and is considered one of the oldest existing wooden structures in the world. It was restored between 1934 and 1985 and was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. In fact, this Japanese restoration technique was also used by the Association for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage Buildings of Japan in 1994 when it restored a traditional house called banua tamben in Tana Toraja, Sulawesi (Uekita et al. Citation2014).

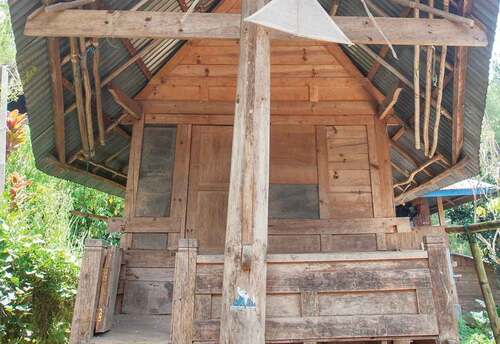

The traditional wooden architecture of the Toraja people is a stilt house with a triangular roof extending back and forth, built without the use of any nails, and is well known for its high cultural value. The ten traditional settlements of Tana Toraja in Sulawesi and Bawomataluo settlement in the South Nias are on the Indonesian government’s World Heritage Tentative List. However, the Mamasa Toraja traditional village, also on Sulawesi, is not as well-known as the aforementioned villages. This is probably due to its smaller size the fact that its buildings do not seem to have been well preserved. The Orobua village in Mamasa Regency, West Sulawesi (), is comprised of eleven settlements based on clan (Toriogoe and Wakabayashi Citation1995). The Oroabua settlement belonged to powerful tribal chiefs who ruled the region several decades ago. The settlement is located in hilly terrain with a total area of about 0.55 hectares and a population of 56 in 2020. Most of the inhabitants are elderly and work in agriculture, livestock rearing, and simple labor. The younger generations leave the village upon reaching working age.

The traditional houses of the Mamasa Toraja () have similar characteristics to those of Tana Toraja, but the Orobua settlement has not been placed on the World Heritage Tentative List. This does not seem to reflect the cultural value of the Orobua settlement. In general, to evaluate historical wooden buildings and traditional villages as cultural heritage, it is necessary to understand their condition and the historical environment of the village. Unfortunately, no survey of traditional buildings in the Orobua settlement has been carried out in recent years, and there is no information on their condition. Therefore, the cultural value of the Orobua settlement and the steps required to preserve its traditional buildings has not been clarified.

There have previously been three major studies on the Orobua settlement. Torigoe and Wakabayashi surveyed the settlement in 1992 (published in Citation1995) in the first comprehensive study of the settlement that included its layout, actual measurements of houses, and interviews with residents. In 1992, the Orobua people had far simpler lifestyles compared to other Torajanese who lived in the Sa’dan area; electricity was unavailable, and yet the culture remained intact. Villagers still used communal toilets.

In 2006, the Department of Culture and Tourism did a second study of the Orobua settlement focused on conservation (Agustono and Asriyadi Citation2006). The study showed that one of the houses was severely damaged and called for its restoration and maintenance. It also reported that several houses had had their roofing materials switched from wood or thatched to tin, and those traditional houses were being expanded. After the study, to preserve such traditional areas, the government provided support to repair one of the traditional houses (banua sura’-layuk) and the infrastructure around the renovated traditional houses. The government also recommended dubbing the roof to prevent further deterioration of the house. Ironically, many traditional houses have changed their roofs to tin afterward as a result.

The third study, undertaken by Kees Buijs in Citation2018, is a survey of the Mamasa settlement from a cultural anthropological perspective. Traditional houses in Toraja (Tongkonan) and Mamasa (banua) are compared in the study. It finds that the shapes and ornaments of banua in Mamasa show ancient traditions and confirm the possibility that the settlers migrated from Sa’dan Toraja a long time ago.

Both 1992 and 2006 surveys show the settlement layout. However, these maps were prepared without using satellite images. Thus, the location of buildings within the settlement is inaccurate. In addition, some buildings clearly appear to have been missing when compared to the 2020 satellite images. Therefore, based on the 2020 satellite images and field interviews, these were corrected in Chapter 2.

2. Research methods and materials

2.1. Research methods

This study aims to clarify the following:

(1) Changes in the settlement: To clarify the impact of modernization on the Orobua settlement, changes in the buildings between 1992, 2006, and 2020 are analyzed. The base maps used are from an academic survey published in 1992, a survey report from 2006, and satellite images from 2020. Interviews with residents of all traditional houses have been conducted to fill in missing information from the 1992 and 2006 data and to collect records of partial additions and renovations. The field survey and interviews were conducted over a period of three months, from September to November 2020. (2) Status of traditional houses: The current condition of the traditional houses in the Orobua settlement is examined through field surveys of all houses and interviews with the residents. (3) Impacts of modernization of lifestyle on the houses: The impact of modernization of lifestyle on the houses are examined through case studies of renovation of traditional houses and construction of modern houses. (4) Measures for conservation: Based on interviews with residents regarding tourism, the possibility of measures to extend the economic potential of the Orobua settlement to the whole community and help conserve the traditional houses is examined.

2.2. Research materials

First, the accuracy of the research materials used was verified. The layout of the buildings in 1992 (Torigoe and Wakabayashi) and 2006 (Department of Culture and Tourism) was compared with the results of interviews regarding the house age and modifications conducted in 2020, and the maps were corrected if necessary. In case of discrepancies between the interview results and the existing map, the interview results were given priority for houses whose construction date could be determined, and the maps of each period were given priority for other houses.

Although the site map of 1992 () shows the buildings themselves in detail and it is mostly accurate, the distance between buildings and the orientation of the buildings seems inaccurate, and several buildings that are over 100 years old are missing in the plan (). There are similar issues in the site map of 2006 (). The site plans of 1992 and 2006 have been revised based on the satellite images and the results of the questionnaire survey in 2020 ().

In this study, the houses are divided into three types: traditional, modified, and modern. Modified houses are those with material changes or those with extended structures and renovation. Modern houses are new houses built with mixed materials of traditional and modern materials.

2.2.1. Reproduction of site map in 1992

Through interviews with residents and comparison with satellite images, it is found that the layout of buildings on the map in1992 (Toriogoe and Wakabayashi Citation1995) was inaccurate in parts and missing several buildings () Therefore, the map of 1992 was redrawn (). The angle of houses along the north-south axis was corrected based on current satellite images. According to the map of 1992, the number of buildings in total was 20; ten traditional houses (banua) and ten granaries (alang). It was found that four existing buildings were missing from the map; one traditional house which was over 100 years old (banua rapa’), one modern house built in the 1970s, one granary on the south side, and another on the west side. They have been added to the reproduced map accordingly ().

2.2.2. Reproduction of site map in 2006

The 2006 map by the Ministry of Tourism does not show the buildings as accurately as the 1992 version (). Some of the new buildings are missing, and the changes to traditional houses are not visible. The dimensions of the buildings are inaccurate, and the shape of the landscape and the position of the houses is not clearly shown. To reproduce the map, interviews and surveys with residents were carried out and matched with the satellite images.

However, the 2006 research report by the Ministry of Tourism contains some important information about changes in houses. There are ten traditional houses on the 2006 map. The number of traditional houses has not changed from the previous study done in 1992. However, two houses have changed their roofing material to tin, six buildings (one house and five granaries) have expanded, and one building was reconstructed. These corrections did not change the overall number of traditional houses ().

Figure 5. Redrawn sitemap of the Orobua settlement in 1992 (Based on Torigoe and Wakabayashi 1995, satelite images, interview with Ambe’ Langi (local resident))

Figure 6. Sitemap of the Orobua settlement in 2006 (Source : Culture Heritage Agency Citation2006)

3. Physical changes between the three periods

This chapter analyses the changes in the number of buildings and their modifications in order to reveal the impact of modernization on the Orobua settlement.

Legend : / not existing - no change ✓ change

3.1. State of the settlement in 1992

In 1992, the Orobua settlement was little affected by modernization. Electricity was unavailable. There were 24 buildings in total, including 11 traditional houses, one modern house, and 12 granaries (alang)(and ). Of those 11 houses, three were around 200 years old, three were around 100 years old, and one was around 80 years old (in the present-day). The year of construction for the other four houses is unknown. The two-storied modern house was built in 1972. The two buildings on the upper plateau are banua sura’, where the previous traditional leader resided, and one granary. There are 12 buildings on the inside plateau; the five houses include banua sura’-layuk, banua sura’, banua bolong, banua rapa’ (biasa), banua samba (banua misa lantang), and seven granaries. There are 10 buildings on the lower plateau: six houses, including five banua rapa’ (biasa), one modern stilt house, and four granaries beside them. At this time, all traditional houses were still in their original condition, and the settlement was far from modern.

3.2. Changes between 1992 to 2006

The research report in 2006 mentions that some traditional houses have been changed, but unfortunately, detailed information is unavailable. Interviews with residents were conducted to examine the transformation of settlement between 1992 and 2006. shows the results, the number of buildings in 2006 was 24 after corrections. The number has not changed from 1992. However, the number of houses increased from 12 to 16, and the number of granaries decreased from 12 to 8 ( and ). One traditional house had been removed. The significant changes in the landscape are the increase of five modern houses and the modification of five traditional houses (). Only four traditional houses kept their original condition in 2006. Of the five traditional houses modified, four had been expanded using wood or bamboo for the structure and walls, two at the rear and two on the side. The expanded parts were used for kitchens, which suggests that the modernization of traditional houses begins with water facilities meant to provide residents with convenience. Two traditional houses had had their wooden roofing replaced with tin. Among the eight granaries, two had changed their roofing to tin.

Table 1. Number and percentage of buildings of specific types

Table 2. Modification made to house by type and age

Table 3. Transformation of a modern house (ID 5–1).

3.3. Changes between 2006 to 2020

The total number of buildings increased to 29 in 2020 (). Between 2006 and 2020, the number of modern houses doubled from six to 12 while the number of modified houses also increased from five to nine. Only one traditional house is in its original condition. Among the nine modified houses, eight have replaced roofs. Eight houses had been expanded; six at the rear and two at the sides (). One house was connected to a modern house. There are also changes in construction materials.

While modern houses built before 2006 used natural materials such as wood and bamboo, those built after 2006 use industrialized materials such as bricks and concrete. In addition, such industrialized materials are used for the modification of traditional houses. Modern houses and modified houses with industrialized materials change the landscape characterized by traditional houses (). One of the traditional houses (ID 2–2 on ) has changed its function to become a guesthouse for tourists. In addition, a public bathroom and restroom for residents and visitors (ID 7 on ) were built. It is clear that tourism has now reached the Orobua settlement.

The landscape of the Orobua settlement has changed significantly since 2006 (). However, it is also interesting that when modifying a traditional house or building a new house, residents avoid damaging the original structures as much as possible. The traditional houses are connected with deities as they are considered a religious center among the Mamasa community (Buijs Citation2016). This may be related to the belief of residents that destroying traditional houses can bring bad luck to their families. If the newly added modern houses and modifications of traditional houses are removed, the landscape before modernization which had been maintained for hundreds of years could be restored.

4. Modifications of houses

This chapter analyses how modernization has transformed traditional houses. Modifications of modern houses are also analyzed.

4.1. Traditional house

4.1.1. Replacement of roof material

The ship-shaped roofs are the hallmark of traditional houses (banua) among Toraja tribes. For roofing material, the Mamasa Toraja used wood () or thatched, depending on the owner’s economic status, while the Toraja used bamboo. The adoption of wood-thatched roofs by the Mamasa Toraja was probably influenced by the fact that they live in a highland area with high precipitation. The cross-section by Torigoe and Wakabayashi (Citation1995) shows the maximum height of the roof ridge is about ten meters.

In 1992, all traditional houses were in their original condition (). However, in 2006, two traditional houses had replaced the roof material with tin, and one modern house was constructed with a tin roof (). Between 2006 and 2020, six traditional houses had had their roofs replaced with tin. As a result, only two houses still have wooden roofs ( and ). Similarly, in a traditional settlement on Nias Island, some traditional thatched roofs made of sago palm leaves had been replaced with tin roofs (Sataka et al. Citation2014).

Banua sura’-layuk (1) (), the village chief’s house, is a place for cultural and ritual activities and events in the village. The last roof renovation using wood was done in 1995 with the support of a cultural heritage institution in Makassar (Interview with Ir. Timoti, a village chief, 65 years old). A similar example is banua sura’ (ID:2–2), the house of a former village chief many years ago (). It also received support from the Department of Culture and Tourism in 2006. However, currently, these roofs are damaged. Some parts of the roofs have collapsed due to climate and age.

Based on interviews with residents, several other houses received support from the local government and individual donations for roof replacement in the 2010s. The purpose was to avoid further damage and collapse of traditional houses. The estimate of the total cost for a roofing renovation of a traditional house with all traditional materials (Uru’ wood: Elmerrillia Ovalis, Miq: Dandy Magnoliaceae) is Rp.150–200 million (1.16–1.55 million yen). However, the subsidy was not enough to cover the re-roofing with traditional materials. The government did not instruct on the use of traditional materials either. The cost of a tin roof is only 10–15% of traditional wooden materials. Therefore, using the subsidy, residents renovated the roofs of traditional houses with tin ().

4.1.2. Replacement of materials for other house parts

There was no replacement of materials for other house parts except roofs among the traditional houses between 1992 and 2006 (. However, there were significant changes made after 2006. Between 2006 and 2020, seven traditional houses replaced their walls (rinding) and the triangular wall on top (para ba’ba) due to degradation caused by age and climate (). In addition, two houses had their doors and windows redone in a modern style using non-traditional woods. As with roofing materials, wall material changes are primarily due to economic issues. A renovation of a house using traditional rare wood can cost 450–600 million rupiah (3.4–4.6 million yen), 30–50% higher than other readily available woods. However, it is much more durable.

Modifications to doors hold a slightly different meaning. It is due to a change in customs. Traditionally, the door, the entrance to the house, had a symbolic meaning. shows a traditional door (height 80 cm x width 60 cm). Due to the low height of the door, people entering the house had to bend down. That attitude was said to show respect for the ancestors thought to have ties with the house. In addition, the sculptures on the wall around the door indicated respect for their ancestors.

However, the refurbished door of a traditional house (banua rapa’ ID 4–6) is taller (height 180 cm x width 60 cm) to allow people to enter without bending, and the surrounding wall carvings are omitted (). Thus, entrance renovations were done from a practical standpoint and lacked cultural meaning.

4.1.3. Expansion of room

There was no expansion of traditional houses in 1992 (. Three houses had been expanded by 2006, and the number increased to seven in 2020. The houses were expanded at the rear or side. The expanded spaces are used as kitchens, dining rooms, living rooms, or bedrooms. Before 2006, wood was the main construction material. However, after 2006, the use of bricks and concrete became common ().

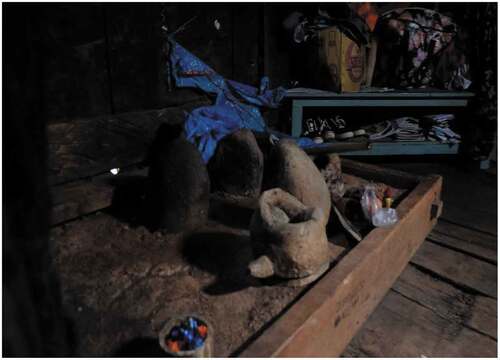

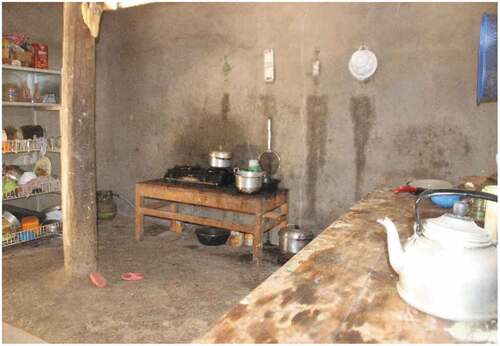

Banua sura’ (ID 2–1) is one of the traditional houses that has been expanded (). The rooms are lined up in a row as shown in ; (1) sali-sali is a public space for guests, (2) tado is a room for closed guests, (3) baba is a room for families and a bedroom for families and guests at night, (4) tambing is a private bedroom, and (5) lombon is a dining room with a kitchen sometimes used for religious activities. A new kitchen was installed in the expanded room (6), covered with fire-resistant concrete ().

The traditional kitchen had a stone hearth used not only for cooking but also for religious rituals to pray for the peace of the family and community (aluk) (). However, after a new kitchen had been installed in the expanded room, the old kitchen became a bedroom and storage space. The new kitchen is equipped with a gas stove and sink and is used only for cooking without religious functions (). The changes in the meaning of traditional spaces may be explained partly by the introduction of Christianity in the settlement.

4.2. Modern houses

4.2.1. A typical modern house (ID 5-4)

As with the renovation of traditional houses, the construction materials for modern houses are also changing over time. Modern houses built before 2006 were mainly built of wood, but since 2006, the use of industrial materials such as bricks and concrete has gradually increased. The wood most often used in modern houses is pine wood (Tusam), readily available, unlike the local wood used in traditional houses (Uru’ wood: Elmerrillia Ovalis, Miq: Dandy Magnoliaceae). Modern houses are also expanded and renovated based on family needs. As of 2020, five out of 12 modern houses have been renovated and expanded.

show a modern house made using wood and industrial materials (ID 5–4). The house was built around 2003, according to the owner (Mr. Tasik, 45 years old). Initially, the house was built using wood and bamboo with a tin roof. Since 2006, the house has been renovated several times. Materials are selected based on budget and availability. Walls, floors, and roofs are now built with mixed materials of wood and industrial materials. The windows and doors are larger than traditional ones.

4.2.2. Transformation of a modern house (ID 5-1)

The transformation of the house reflects the history of the family inhabiting it. Forty-eight years ago, the first modern house in the Orobua settlement was built (ID 5–1). The renovation of the house was done in two phases (). First, a stilt house was built with a pyramid-shaped thatched roof for three family members, a couple and one child. The floor plan was simple, consisting of a living room and a bedroom. As more children were born, the first expansion was made to the space under the raised floor, adding two bedrooms and a kitchen. As the number of children increased further to a total of nine, a one-story annex was built. The expansion added a living room, a bedroom, and a new kitchen. The kitchen consists of two rooms. The one in the front is a modern kitchen with a gas stove, while the one in the rear is a traditional kitchen with a stone hearth for traditional cooking. At this time, the pyramid roof of the main building was also replaced by a traditional ship-shaped tin roof ().

According to the owner, Mr. Bernardus, 65 years old, the purpose of expansion and renovation was to make up for the lack of space. The pyramid roof was chosen because it was cheaper than a traditional ship-shaped roof. However, during the second renovation, the roof was replaced with a traditional one over a terrace (sali-sali) (). For the Toraja people, the terrace has been a symbolic place to entertain guests.

Mr. Bernardus also explained the construction of the traditional ship-shaped roof () was done to preserve their cultural identity and create a traditional impression. This change was done based on the instruction of the village chief to attract tourists. However, most modern houses’ residents did not follow the instruction because of the high cost involved – the construction cost of a traditional roof is estimated to 50 million rupiah (400 thousand yen).

5. Discussion

When considering a traditional house as a cultural heritage, its authenticity is essential. In particular, its materials and construction methods should be as close to the original as possible. In the case of the Orobua settlement, the modifications done to traditional houses can be classified into three categories: replacement of roofing materials, replacement of components in other parts of the house, and room expansion. Believing that destroying a traditional house would bring disaster to the family, the local people have maintained their traditional houses without damaging them. For this reason, most of the traditional houses are still intact, although modified, and the modified parts can be removed if necessary to restore them to their original forms. However, the kinds of trees that were traditionally used for the houses can no longer be cut unless special permission is obtained. In the long term, these trees should be planted continually to provide future construction material.

On the other hand, modernization has reached the Orobua settlement, especially after 2006. It is becoming the norm to install a modern kitchen and private bedrooms, which were not a part of traditional houses. It is challenging for traditional houses to accommodate such needs. Therefore, it is necessary to mix traditional houses and modern functions within the same village or build a new settlement with modern houses outside the old village to keep traditional settlements in their original form. In the latter example, the old village would be a museum exhibit without a real community, perhaps with only a few older people inhabiting it.

In modern houses, traditional elements such as stone-lined stoves, low doors, and wall carvings, which were also connected with religious ceremonies, have been omitted. In other words, the connection with the ancestors of the former traditional houses is no longer seen. As these new values become more common, people living in traditional houses also may stop maintaining their old houses in the future.

Interestingly, modern houses are also transforming. The first modern house in the Orobua settlement was expanded twice in response to growing family needs. Later, the owner added the traditional ship-shaped roof on top to preserve their cultural identity. The overlay of a traditional-style roof over a modern house may not be authentic as a cultural heritage. However, it is also true that this renovation allowed the house to blend in better with the traditional landscape of the Orobua settlement. If traditional houses and modern houses are to coexist in the village, such renovations would be an option.

Compared to the settlements of Tana Toraja in Sulawesi and in Nias, which are on the Indonesian government’s World Heritage Tentative List, the Orobua settlement is not considered as significant, mainly due to its small size. However, as can be observed through this study, the Orobua settlement has its unique Mamasa Toraja characteristics that differentiate it from Tana Toraja, with an example being boat-shaped roofs thatched with wood.

Perhaps it is good to start by restoring traditional thatched roofs from tin roofs, which may be easier agreed upon by the local community. However, the construction cost is a problem. Traditional materials cost more than modern materials today. For example, wood-thatched roofs are characteristic of the traditional houses of the Mamasa Toraja, which are different from the traditional houses of the Tana Toraja, which have bamboo-thatched roofs. It is estimated that the total cost of renovating a roof of a traditional house with traditional wood (uru wood) is 150–200 million rupiah (1.0–1.4 million USD). It would be difficult for the residents in the Orobua settlement to bear such a cost entirely on their own.

As a way to fund conservation, it is worth considering collecting tourist fees from visitors. However, the promotion of tourism needs to be done carefully. Tourism development in Tana Toraja started in earnest in the 1970s during the Suharto administration. The number of tourists increased from only 58 in 1971 to 25,537 in 1979. The rapid transformation of the village into a tourist destination brought changes to the region. There has been a situation where the schedule of traditional rituals has been changed to suit the convenience of tourists, and dance performances for tourism have been brought. It has also been pointed out that the tourism industry (hotels, souvenir shops) only enriches a small portion of the population and does not contribute to the overall economic well-being of the community (Yamashita Citation1988, 271–278).

Recently, in Asian countries, while being designated a UNESCO World Heritage site tends to stimulate the regional economy, the adverse effects of excessive tourism have also been observed. In Lijiang, China, the conversion of residential buildings into commercial facilities has progressed, causing their original residents to move out of the city (Fujiki Citation2010). In Hoi An, Vietnam, the excessive installation of signboards has disrupted the historical townscape. In order to maintain the traditional townscape of the town, a new set of guidelines has been formulated (Utsumi Citation2010).

In order to both maintain the traditional landscape and contribute to the economic well-being of the local community, it is necessary to manage tourism in a small-scale settlement such as Orobua in a responsible manner. In any case, the local community must decide, and the government and researchers need to act as advisors in order to seek the necessary solutions to preserve the traditional landscape.

6. Conclusion

The traditional landscape of the Orobua settlement has gradually been changing since 1992; before 2006, the number of granaries had begun to decrease, and after 2006, more traditional houses had been modified and extended with modern houses, and the use of industrial materials such as bricks and concrete became common. It was also necessary to change the roofs of houses to tin roofs to protect their structure from collapsing. The impact of these changes in the landscape is significant. However, behind the changes, traditional houses, which are considered to be an integral part of religious practices (aruk), have been left intact. If the newly added modern houses and modifications of traditional houses are removed, the pre-modern landscape that has been maintained for hundreds of years may be restored.

Meanwhile, modernization of lifestyle and values is beginning to penetrate the community. Renovations, such as replacing roof and wall materials or adding rooms, are based on functional requirements. However, changes in elements that once had a symbolic meaning, such as the size of the front door, wall decoration, and kitchens with stone stoves, indicate that modernization is affecting the consciousness of the residents. If the religious practice of maintaining traditional houses fades away, there is a possibility that traditional houses will be damaged or demolished in the future. The aging of the community is a particularly serious problem as the younger generation leaves the village in search of jobs.

In order to preserve the traditional landscape, it is essential to make people aware of the cultural value of traditional houses in the Orobua settlement. It would be very effective if the cultural value of the Orobua settlement could be duly assessed and it were placed on the Indonesian government’s World Heritage Tentative List. Restoring the thatched roofs that characterize the traditional houses of the Mamasa Toraja with tourism revenue may bring the Orobua settlement closer to being inscribed on the Tentative List. However, it is costly to restore traditional houses with traditional materials and methods. One way to raise the cost is to consider the promotion of tourism. Excessive tourism is a problem, but appropriate tourism can create employment for the younger generation and revitalize the village. Such an approach should be considered by outsiders such as government officials and academics. Nevertheless, it is up to the local people to decide whether to preserve the cultural values of the Orobua settlement.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance of the Cultural Conservation Preservation Centre in Makassar South Sulawesi, Mamasa City Culture and Tourism Agency, Local Government in Sesenapdang district, chief of Orobua Village, and all of communities and respondents from the Orobua settlement for their permission and cooperation during the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agustono, M., and Y. Asriyadi 2006. “Studi Teknis Kompleks Rumah Adat Indonasesenapdang, Kabupaten Mamasa Provinsi Sulawesi Barat [Study on the Indonesian Traditional House Complex in Sesenapdang, Mamasa Regency, West Sulawesi Province]. Departemen Kebudayaan Dan Pariwisata [Ministry of Culture and Tourism]. Balai Pelestarian Peninggalan Purbakala Makassar[Makassar Ancient Heritage Preservation Centre].”

- Buijs, Kees 2016. Personal Religion and magic in Mamasa, West Sulawesi: the search for powers of blessing from the other world of the gods (Leiden: Brill)

- Buijs, Kees. 2018. Ancient Traditions in Toraja Houses of Mamasa. West Sulawesi, Banua as Centre of Power of Blessing. Makassar: Ininnawa .

- Fujiki, Y. 2010. “Senryakuteki Kanko Kaihatsu to Dentoteki Buka Hozen No Katto: Chugoku Reiko [Conflict between Strategic Tourism Development and Traditional Cultural Preservation in Lijiang, China]” Fujiki, Y. ed. . Ikiteiru Bunka Isan to Kanko [Living Cultural Heritage and Tourism] (Kyoto: Gakugeishuppansha) 208–227.

- Historic England. “Heritage Conservation Defined.” Accessed January 26 2022. (https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/hpg/generalintro/heritage-conservation-defined/)

- Ono, K. et al, et al. 2019. Kanshu mura fukko’ no tame no seifu hojo jigyo niyoru mokuzo kenzobutsu no hozen katsuyo: Indoneshia Niasu-to dento shuraku ni nokoru mokuzo kenzobutsu hozon no kenkyu sono 18 [Preservation of Wooden Structures through Government-Subsidized Projects for the Reconstruction of Customary Villages: A Study on the Preservation of Wooden Structures in the Traditional Settlements of Nias Island, Indonesia, Part 18] Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting (Hokuriku) July 2019, 69–70. Architecture Institute of Japan.

- Sadaka, N. et al, et al. 2014. Bawomataruo Mura Dento Mokuzo Kaoku no Onshitsudo Monitaringu: Indonesia Niasu-to dento shuraku ni nokoru mokuzo kenzobutsu hozon no kenkyu sono 8 [Temperature and Humidity Monitoring of Traditional Wooden Houses in Bawomataluo Village: Study on Preservation of Wooden Structures in Traditional Settlements in Nias Island, Indonesia Part 8].Traditional Settlements in Nias Island, Indonesia Part 8]. Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting (Kinki) September 2014, 731–732. Architecture Institute of Japan.

- Toriogoe, K., and H. Wakabayashi. 1995. Wazoku Toraja [Warrior Toraja]. Tokyo: Taishukan Shoten.

- Uekita, Y et al, et al. 2014 . “International Collaboration Research for Preservation of Wooden Structures in Indonesia: Application of Japanese Restoration Techniques and Significance of Preservation, Research Report for Kakenhi [Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research].” Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

- Utsumi, S. 2010. Kankochika Ni Tomonau Keikan No Henka to Kontororu: Betonamu Hoian [Change and Control of Landscape in the Context of Tourist Attraction Hoi An, Vietnam] Fujiki, Yosuke ed. Ikiteiru Bunka Isan to Kanko [Living Cultural Heritage and Tourism] (Kyoto: Gakugeishuppansha) 166–187.

- Yamashita, S. 1988. Girei No Seijigaku [The Politics of Rituals]. Tokyo: Kobundo.