?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Studies on the factors of the COVID-19 pandemic that influence architecture and spaces have presented various, often contradictory, findings, and the same is true for studies making predictions. Considering this, this study aims to use the Delphi technique, an analytical method for synthesizing the opinions of experts across diverse fields to determine major issues in the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 eras as wells as the architectural and urban spaces in which future changes are expected. This study derived keywords representing major trends and issues that would lead to changes in architectural and urban spaces in the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 eras, predicted the change patterns for each keyword, and determined the architectural and urban spaces expected to undergo major changes. The experts predicted these keywords to show a variety of changes, including the pattern of increasing influence during the COVID-19 pandemic and then decreasing in influence after the pandemic, the pattern of small influence during the pandemic and the increase in influence after the pandemic, and the pattern of greater influence during and after the pandemic. Furthermore, they predicted that most of the post-COVID-19 changes would occur in the housing sector. Developing architectural guidelines that could incorporate these changes is thus necessary.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and purpose of the study

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) began to spread at the end of 2019, and even now, two years later, infections are globally rampant. In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, and countless aspects of economic and social activities changed in response to COVID-19 infectious disease. It was hoped that the COVID-19 pandemic would end as vaccines were developed and distributed, and various countermeasures were implemented, but the virus is still a threat to humanity with the continued emergence of the mutant viruses.

As part of the response to COVID-19, relevant discussions and studies have been conducted in various fields, and the architectural and urban fields is no exception. Although previous studies have proposed various findings based on literature reviews and empirical analyses, they do not present consistent results on COVID-19”s influencing factors or predicted future. Given this uncertainty, it is important to gather these conflicting findings and opinions as research that systematically predict future changes in architectural and urban spaces based on experts” opinions are much needed. Although predicting the end of the pandemic is difficult, it is important to examine how society will change in the current era when people must exercise caution in view of the rampant spread of the virus and also in such time when society no longer has to worry about COVID-19 due to vaccines and therapeutic agents that weaken the spread of the virus.

Thus, this study aims to review a variety of literature related to COVID-19 and apply the Delphi technique to determine major issues in the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 eras and the architectural and urban spaces in which future changes are expected. This will lay a foundation for determining the response direction for architectural and urban spaces in the COVID-19 era.

1.2. Research method and procedure

The main goal of this study is to make predictions for architectural and urban spaces based on social changes in the COVID-19 era. This study applies the Delphi technique, which is mainly used to make predictions. The Delphi technique is an iterative survey method that combines the opinions of multiple experts to reach consensus and is used to make predictions about the future.

The research procedure is as follows. First, trends and issues stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic are reviewed in the literature and summarized. Second, a Delphi survey is conducted with a panel of experts on how the major trends and issues related to COVID-19 will develop. Third, by analyzing the Delphi survey results, this study predicts the direction of changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic and discusses the expected future of architectural and urban spaces based on the results.

2. Literature review

2.1. Related works

COVID-19 is a contagious disease caused by a virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Although COVID-19 does not have a higher fatality rate than other infectious diseases, it is known to be particularly deadly to elderly people with underlying diseases. Its transmission power is also found to be very strong, with transmission through close contact, airborne transmission, and transmission through contact with contaminated surfaces (Ministry of Health and Welfare Citation2020).

Even at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, analysts expected its spread to be slow, considering the nature of previous respiratory viruses, the spread of which tended to drop during the summer when temperatures rise (Kim, Ki, and Lee Citation2021, 215). However, contrary to the initial expectations, the continued emergence of mutant viruses prolonged the spread of COVID-19. Vaccinations have begun in the UK, the US, and other parts of the world, and this was expected to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. However, due to the emergence of breakthrough infections and the limitation of 6-month validity period of vaccine efficacy, countermeasures against “with-COVID-19” rather than the “post-COVID-19” must be considered (Hwang Citation2020, 29).

Plenty of studies have been published to determine the spatial causes of the spread of COVID-19. Scholars have also discussed various urban factors as the spatial causes of infectious diseases, such as population movement and urbanization, economic growth, land-use patterns, globalization, environmental change, and climate change (Matthew and McDonald Citation2006), while analysts have investigated diverse causes of the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, including insufficient green spaces and connectivity (Menéndez and García Citation2021). After analyzing each cause one by one, however, they could not be definitively identified as factors. For example, regarding the density of spaces, although many studies initially suspected the correlation between infectious disease and urban density (Florida, Rodriguez-Pose, and Storper Citation2020), empirical studies have also found that a direct relationship between density and infectious disease is not clear (Hamidi, Sabouri, and Ewing Citation2020). Meanwhile, as the likelihood of airborne transmission of COVID-19 increased, more studies on other aspects of the spatial causes of the spread of COVID-19 have emerged – for example, studies on the extent of the spread of the virus from the body of the infected (Dbouk and Drikakis Citation2020), studies analyzing the process of spreading based on actual cases of mass infection in enclosed spaces (Kwon et al. Citation2020), and studies suggesting the possibility of infection through water and sewer lines (Hwang et al. Citation2021).

As the pandemic situation has become more protracted, people’s space use behavior has changed noticeably. With the social distancing policies, telecommuting, online meetings, and remote classes have made online remote services commonplace. The increase in the amount of time spent at home has led to an increase in the use of streaming services, as well as an increase in online consumption and delivery orders. A number of studies have been published with regard to these changes, mainly on changes in consumer culture and changes in transportation. Studies related to changes in consumer culture can be summarized as the change of commercial topography such as the decline of the central commercial district and the rise of the hyper-local living areas (Lee and Choi Citation2020). Studies on transportation changes have found an increase in the choice of personal means of transport where it is less likely to encounter others than in public transportation used by an unspecified majority (Kim, Ki, and Lee Citation2021).

The spread of COVID-19 and changes in people’s space use behavior have led to examinations on changes in architectural and urban space. Through the analysis of existing literature and the empirical analysis of the changes, studies have proposed that the future of architectural and urban spaces in response to COVID-19 at the macro level (Tricarico and Vidovich Citation2021; Florida, Rodriguez-Pose, and Storper Citation2020; Barbarossa Citation2020; Megaheda and Ghoneim Citation2020). However, these studies are fragmented and are not synthesized into a single discussion, and some studies even show conflicting findings. Therefore, it is necessary to synthesize various views and discuss the future of architecture and urban space in response to COVID-19 holistically ().

Table 1. Review of the related works.

2.2. Delphi technique

The Delphi technique is a structured communication method that obtains the consensus of a group of experts in a specific field. It is used to derive solutions to specific problems, devise policy alternatives, and predict the future. The Delphi technique is based on the premise that the opinions and predictions of a group of experts are more valid or accurate than those of individual experts, and it repeats a process of collecting and revising the experts’ opinions until consensus is reached. The Delphi technique was developed by the RAND Corporation in the US in the 1950s to address the shortcomings of face-to-face discussions and solve urgent defense problems during the Cold War. Originally a military secret, the Delphi technique was revealed in the 1960s and has since been applied as a research method in numerous fields as well as to predict the future (Lee Citation2001).

The Delphi technique is a panel-based research method that can avoid the potential negative effects from council-based discussions. In other words, the participants’ communication process is structured so that the discussion group can address complex problems effectively (Lee Citation2001). The main characteristics of the Delphi technique for this purpose are “iteration and feedback,” “anonymity,” “consensus,” and “statistical representation.” Hence, it arrives at consensus through iteration and feedback while ensuring each expert’s anonymity, and statistical analysis and representation from the collected data are also possible (Noh Citation2006).

The method generally involves selecting an expert panel, completing a questionnaire, and conducting two or more rounds of surveys; individual interviews or group conferences to reach a final conclusion are sometimes added. Generally, to arrive at consensus, statistics (mean or median, mode, variance, quartile, etc.) of the first survey round’s responses are used to challenge the agreement in the second survey round, and the process is repeated until the final result is derived (Noh Citation2006).

The following statistical methods are typically used with the Delphi technique to verify the suitability of the survey or the extent to which opinions converge. Content validity indicates the extent to which specific questions in a questionnaire are evaluated as appropriate, and if the content validity ratio (CVR) is above a specific value, then the question is judged to have content validity. This value varies with the number of respondents; 0.29 is commonly used for 40 or more respondents. Degree of convergence is an indicator of whether the responses are converging, and degree of consensus is an indicator of how much consensus has been reached among the experts. Stability is an indicator of how stable the results are in repeated surveys (Kang Citation2008).

(Ne: Number of questions evaluated as appropriate, N: total number of respondents)

(Q3: third quartile coefficient, Q1: first quartile coefficient, Mdn: median)

(SD: standard deviation, M: mean)

The use of traditional methods to predict the future of architectural and urban spaces due to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as brainstorming with a small number of related experts, could have both methodological and procedural shortcomings. However, the Delphi technique can overcome these challenges by remotely recruiting a large number of experts, collecting their opinions, and allowing them to freely share and review their in-depth opinions under anonymity. Additionally, it can obtain more reliable consensus via iteration and feedback.

3. Delphi survey

Delphi survey was conducted using the following procedure. First, preparation of Delphi survey was conducted, in which keywords of architectural and urban trends and issues related to COVID-19 were derived, a questionnaire was drafted, and an expert pool was configured. Second, the Delphi survey was conducted, comprising three stages of pilot survey with an expert council, first Delphi survey, and second Delphi survey. Third, analysis of the Delphi survey results was conducted using statistical methodologies ().

3.1. Preparation of Delphi survey

3.1.1. Derivation of architectural and urban keywords related to COVID-19

To prepare the Delphi survey, this study first derived keywords of architectural and urban trends and issues related to COVID-19 in the literature before and after COVID-19. Based on reviews by Lee et al. (Citation2009, Citation2011) and Cho et al. (Citation2019), among others, which were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, 15 keywords of trends and issues related to the future of architecture and cities were derived, including “diversification of housing types,” “increase in complexes,” “universalization of green transportation,” “expansion of residential area per capita,” and “universalization of green and intelligent buildings.” From studies by Im et al. (Citation2020) and Kim (Citation2021), as well as many special articles related to COVID-19 including Marr (Citation2020), 15 keywords of trends and issues related to changes in architecture and cities were derived, including “distancing,” “online remote services,” “unmanned services,” “telecommuting,” and “anti-virus air conditioning.” Thus, a total of 30 keywords were derived.

3.1.2. Selection of experts

As the Delphi technique represents the subjective judgments of experts with an objective numerical value, the expert selection step is crucial for deriving a reasonable result. Based on a review of previous studies using the Delphi technique, the expert pools varied in size between each study, ranging from 10 to 50 experts (based on the final valid questionnaire). Some scholars argue that a small number of experts is effective, some that a large number of experts ensures high reliability, and some that there is no large difference in the median for groups of about 15 experts (Noh Citation2006). However, as the survey is repeated, the number of experts who answer all the questions until the final survey round may be small, so this should be kept in mind when the experts are first recruited. Previous studies recruited about two to three times the number of experts in consideration of the final response rate when configuring the expert pool.

Choi, Eum, and Jun (Citation2006) noted that it may be difficult to obtain various opinions when the experts are limited to similar fields, and thus, it is important to consider diverse areas to configure the expert pool. Accordingly, the panel in this study consisted of Korean experts from mainly architectural and urban fields but also included experts from fields related to environmental psychology, sociology, and infectious diseases. The number of valid subjects of questionnaire for the final analysis was set to 50, and an expert pool of about three times this number was configured considering the response rate of two survey rounds.

3.1.3. Questionnaire drafting

The survey questions were designed using the 30 keywords derived as outlined in Subsection 3.1.1. The survey questions can be divided into two categories: 1) questions measuring whether the respondent agrees with statements about the 30 keywords and their importance and 2) questions related to architectural and urban spaces expected to undergo many changes. Questions on agreement with the keywords and their importance were closed-ended Yes/No questions, and the respondents could respond according to “during COVID-19” and “post-COVID-19” separately. Some questions also asked the respondents to rank the presented keywords in order of importance and to suggest keywords they consider important other than those presented. Questions about architectural and urban spaces expected to undergo many changes were open-ended questions asking respondents for up to five short responses paired with the reasons.

3.2. Implementation of Delphi survey

The Delphi survey in this study comprised a total of three stages: (1) pilot survey, (2) first Delphi survey, and (3) second Delphi survey.

3.2.1. Pilot survey (expert council)

The pilot survey was conducted with an expert council to review the suitability and validity of the draft questionnaire. A total of 11 experts-six in architecture and five in the urban field – were selected, and an expert council meeting was held for the pilot survey. At the meeting, experts firstly responded to the draft questionnaire and then discussed on the questionnaire items’ suitability and effectiveness, along with suggestions for the composition of the survey questions.

The experts’ opinions were synthesized after the pilot survey. Many experts thought that the hierarchies of the 30 keywords differed, and a considerable number of keywords had overlapping or unclear content. As such, keywords with ambiguous or overlapping meanings were revised or consolidated, those insignificant in terms of COVID-19 were removed, and new ones suggested by the experts were included. This resulted in a new total of 35 keywords. Furthermore, a structure of clear and hierarchical categories was applied to classify the keywords, and since each expert’s level of understanding of the keywords might vary, explanations of the keywords were added below the questions to minimize misunderstandings and confusion ().

Table 2. The 35 keywords for trends and issues related to COVID-19.

There were other opinions that the questions about agreement with and importance of the keywords were not independent of each other, and the questions about importance overlapped with that about prioritizing the keywords. Thus, the question about importance was replaced with a question asking about the change pattern (increase ↔ decrease or strengthen ↔ weaken) on a 5-point Likert scale. For the questions about architectural and urban spaces, the opinion that it would be preferable to present examples of facilities and spaces along with the questions was reflected, and a list of specific examples of facilities and spaces was added, which was based on the classification of uses under the Building Act. The questionnaire for the first Delphi survey was constructed through this process.

3.2.2. First Delphi survey

The first Delphi survey was carried out using a questionnaire revised based on the results of the pilot study. A total of 50 respondents were randomly selected from the pre-configured expert pool and were sent the Delphi questionnaire. Additional experts were selected according to the number of uncollected questionnaires (i.e., according to the number of vacancies) after two weeks of responding and were sent the Delphi questionnaire again. Through this process, the Delphi questionnaires of the final 50 respondents were collected.

A statistical analysis of content validity, degree of convergence, degree of consensus, and stability was conducted on the responses regarding agreements with and change patterns of the 35 keywords. According to the results, some keywords showed content validity that did not reach a significant level of 0.29. In particular, more keywords did not reach a significant level for “post-COVID-19” than “during COVID-19.” Regarding degree of convergence and degree of consensus, for “during COVID-19.” about three or four keywords did not reach a significant level (degree of convergence <1, degree of consensus >0), whereas for “post-COVID-19,” most keywords, including these, exceeded the level of significance. Thus, it is difficult to conclude that any of the 35 keywords have low suitability. Therefore, 35 were included in the second Delphi survey. Furthermore, descriptive statistics for responses to each question in the first Delphi survey were included under their corresponding questions, allowing the respondents to refer to them during the second Delphi survey.

In response to the question asking respondents to name keywords they thought were meaningful or important in relation to COVID-19 other than the 35 keywords, the experts named the following keywords at least three times: “education (services),” “public transportation,” “metaverse,” “delivery services,” “medical/healthcare services such as hospitals,” “disparities or polarization within society,” “privacy/personal information,” and “rest/leisure/hobby activities.” Accordingly, these eight keywords were presented in the open-ended question asking respondents to name keywords they thought were meaningful or important in relation to COVID-19 other than the 35 keywords, and the open-ended question was converted to a closed-ended question asking the respondents to select five of the eight keywords to help converge the respondents’ opinions.

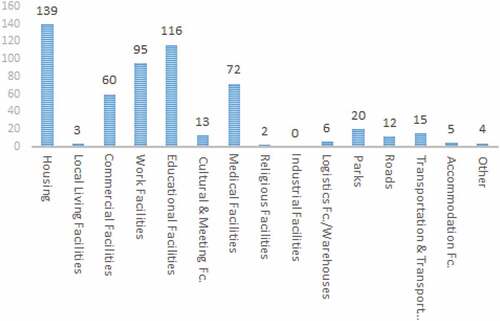

The responses to the question asking respondents to name facilities or spaces expected to undergo many changes due to COVID-19 were reviewed, and they could be classified into 15 major categories: “housing,” “local living facilities,” “commercial facilities,” “work facilities,” “educational facilities,” “cultural and meeting facilities,” “medical facilities,” “religious facilities,” “industrial facilities,” “logistics facilities/warehouses,” “parks,” “roads,” “transportation and transport facilities,” “accommodation facilities,” and “others.” Reflecting this in the second Delphi survey, the previous open-ended question was converted to a closed-ended question asking the respondents to make selections within these 15 major categories, and the first survey responses classified according to the 15 major categories were included under the question. As explained above, the survey questions were developed based on the results of the first Delphi survey to construct the questionnaire for the second Delphi survey.

3.2.3. Second Delphi survey

The second Delphi survey was conducted using a questionnaire developed based on the first Delphi survey. The questionnaire was distributed to the 50 experts who were the subjects of the first Delphi survey. However, as the questionnaires could not be collected from some of the experts owing to individual circumstances, the Delphi questionnaires were collected from a total of 39 respondents.

The descriptive statistics, such as frequency, median, quartile coefficient, mean, and standard deviation, were firstly obtained for each item from the Delphi survey results. A statistical analysis was then conducted to evaluate content validity, degree of convergence, degree of consensus, and stability. This was all performed using MS Excel and the statistical analysis tool KESS.

4. Analysis results

4.1. Agreement with keywords and perception of changes

A statistical analysis of content validity, degree of convergence, degree of consensus, and stability was conducted on the responses regarding agreement with and change patterns of the 35 keywords. Overall, the results were similar to the analysis results of the first survey. Content validity was significant except for some keywords, and degree of convergence and degree of consensus were significant overall. Stability was slightly lower than that of the analysis results of the first survey overall, signifying that the experts’ opinions become more stable with repeated Delphi surveys ().

Table 3. Agreement with and change patterns of the 35 keywords.

Regarding the respondents’ agreement with the 35 keywords, the results were nearly identical to those of the first Delphi survey for both “during COVID-19” and “post-COVID-19”; keywords with a high agreement rate in the first survey showed an even higher agreement rate, whereas keywords with a low agreement rate in the first survey showed an even lower agreement rate. A similar tendency was observed in the change patterns. This was likely caused by the consensus of opinions due to the Delphi method’s iterative surveys.

For the five keywords in the “drivers of change” category, the agreement rate was considerably high at 90% or more for during COVID-19, whereas for post-COVID-19, the agreement rate of all keywords other than “anti-virus air conditioning” fell to below 50%. A similar tendency was observed in the change patterns; for during COVID-19, all five keywords exceeded a mean of 4 points, but for post-COVID-19, all keywords except “anti-virus air conditioning” fell to around 3 points. This means that the experts predict as follows: because the keywords in the “drivers of change” category represent main factors that will drive change in the COVID-19 era while the COVID-19 pandemic continues, they will exert considerable influence on social changes and changes in architectural and urban spaces, whereas after the pandemic their degree of influence will wane and their presence as drivers of change will decrease. However, the experts predict that “anti-virus air conditioning” would have a huge influence during the pandemic and maintain its influence even after the pandemic.

Regarding the 11 keywords in the “social changes” category, for during COVID-19, all keywords showed agreement rates of 70% or higher except for “population relocation,” and for post-COVID-19, “moving distance/frequency,” “individualized transportation and services,” “tourism industry,” “sharing economy” as well as “population relocation” showed lower agreement rates. “Online remote services,” “telecommuting,” “unmanned services,” and “logistics industry” showed very high agreement rates for both during and post-COVID-19. As for change patterns, for during COVID-19, “moving distance/frequency,” “tourism industry,” and “sharing economy” recorded low scores of 2 to 3 points, whereas for post-COVID-19, these three keywords all exceeded 3 points. “Online remote services,” “unmanned services,” and “logistics industry” showed high scores for both during and post-COVID-19 at over 4 points. This means that the experts have predicted as follows; the keywords of “Online remote services,” “telecommuting,” “unmanned services,” and “logistics industry” are leading rapid social and spatial changes as direct social responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and will continue to do so. Meanwhile, during the COVID-19 pandemic, keywords such as “moving distance/frequency,” “tourism industry,” and “sharing economy” will lead social and spatial changes in a way that is controlled or contracted due to the spread of COVID-19, whereas after the pandemic this tendency will weaken and social and spatial changes will tend to recover toward pre-COVID-19 conditions, that is, moving out of the “shadow of COVID-19.”

Regarding the six keywords in the “buildings” category, for during COVID-19, no keywords showed especially high agreement rates except for “complexification of housing functions,” whereas for post-COVID-19, the agreement rate of all keywords exceeded 70%. In the change patterns as well, all six keywords showed higher scores for post-COVID-19 than during COVID-19, ranging from 4 to 5 points. In particular, the level of agreement for “diversification of housing types” and “mixed-use buildings” during COVID-19 was low enough to indicate low significance in terms of content validity. This reflects the expectation that the keywords “diversification of housing types” and “mixed-use buildings” will not have a direct relationship to architectural and urban spatial changes due to COVID-19, whereas “residential area per capita,” “complexification of housing functions,” “intelligent buildings,” and “flexible buildings” will gradually increase in presence as the main pillars of architectural and urban spatial changes through COVID-19 era. The experts predicted that “complexification of housing functions” would become the main pillars of architectural and urban spatial changes both during and after COVID-19.

Regarding the seven keywords in the “street blocks and complexes” category, for during COVID-19, all keywords except “industrial complex recycling” showed considerably high agreement rates, and for post-COVID-19, the agreement rates of “industrial complex recycling,” “hyper-local living areas,” and “temporary change of use” fell substantially. “Public movement spaces,” “public rest spaces,” “green spaces,” and “commercial spaces” maintained relatively high agreement rates both during and after COVID-19. Regarding the change patterns, “industrial complex recycling,” “Public movement spaces,” “public rest spaces,” and “green spaces” showed a stronger change pattern for post-COVID-19 than during COVID-19, while “hyper-local living areas” and “temporary change of use” showed a weaker change pattern for post-COVID-19 than during COVID-19. This reflects the expectation that “Public movement spaces,” “public rest spaces,” and “green spaces” will gradually increase in presence in terms of architectural and urban spatial changes as it goes through the COVID-19 pandemic and continue to increase even after the pandemic. These keywords have a somewhat lower presence than the keywords under “drivers of change” and “social changes” in terms of immediate response to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, in terms of long-term change through the pandemic, they can be considered highly significant. In contrast, the experts expected “hyper-local living areas” and “temporary change of use” to show a considerable presence in architectural and urban spatial changes in terms of direct and immediate responses to COVID-19, but that their presence as the main pillars of architectural and urban spatial changes and the degree of actual changes would decrease after COVID-19.

Of the six keywords in the “cities” category, for during COVID-19, “transportation facilities and services,” “urban – rural disparities,” and “smart city” showed relatively high agreement rates, whereas “land use density,” “expansion of urban periphery,” and “mega city” showed fairly low agreement rates. This tendency was nearly identical for post-COVID-19 as well. Regarding change patterns, all six keywords showed a stronger change pattern after COVID-19 than during COVID-19, although they varied in degree. This suggests the expectation that “transportation facilities and services,” “urban – rural disparities,” and “smart city” will have a significant presence in architectural and urban spatial changes in terms of long-term change as well as direct and immediate responses to COVID-19. In contrast, the experts expected that “land use density,” “expansion of urban periphery,” and “mega city” would not have a strong correlation with architectural and urban spatial changes caused by COVID-19, and would be major pillars of architectural and urban spatial changes regardless of COVID-19.

4.2. Importance of keywords

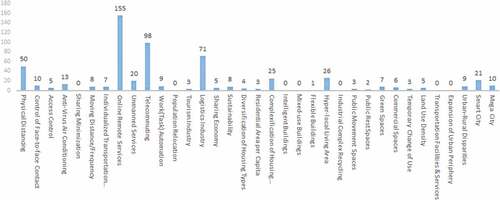

Regarding the response results of the importance of the 35 keywords, an overwhelming number of experts selected “online remote services” as the most important keyword, and many selected “telecommuting” as the second-most important. Many experts ranked “logistics industry” and “telecommuting” in third place, “telecommuting,” “complexification of housing functions,” and “logistics industry” in fourth place, and “logistics industry” and “hyper-local living areas” in fifth place. This study assigned differential points according to the ranking and calculated the weighted sum of the number of selections for each keyword: 5 points for first, 4 points for second, 3 points for third, 2 points for fourth, and 1 point for fifth. As a result, the most important keywords in order were “online remote services,” “telecommuting,” “logistics industry,” “physical distancing,” “hyper-local living areas,” “complexification of housing functions,” “smart city,” “unmanned services,” “anti-virus air conditioning,” and “control of face-to-face contact.” ()

The experts were also asked to select five among eight keywords derived from the first survey results in the question on keywords expected to be important other than the 35 presented keywords. “Disparities or polarization within society” was selected the most, “delivery services” and “medical/healthcare services such as hospitals” was ranked second, “education (services)” was ranked third, and “rest/leisure/hobby activities,” “metaverse,” and “privacy/personal information” were ranked fourth. This suggests that the experts expected “Disparities or polarization within society” to be quite important given its similar keywords mentioned in the first survey, combined with other ones such as disparities in education and disparities in medical services. Meanwhile, although “delivery services” can be seen as overlapping with “logistics industry,” the experts focused more on the rapid spread of delivery services and the resulting changes in social customs from the perspective of everyday life, rather than the macro perspective of “logistics industry.”

4.3. Relationship with architectural and urban spaces

Regarding the facilities or spaces expected to undergo many changes, “housing” was most commonly ranked first, “educational facilities” both second and third, “work facilities” fourth, and “educational facilities,” “work facilities,” and “commercial facilities” fifth. Differential points were assigned according to the ranking and the weighted sum was calculated of the number of selections for each keyword: 5 points for first, 4 points for second, 3 points for third, 2 points for fourth, and 1 point for fifth. “housing” ranked first, followed by “educational facilities,” “work facilities,” “medical facilities,” “commercial facilities,” “parks,” “culture and meeting facilities,” and “transportation and transport facilities” (). If “roads” were combined with “transportation and transport facilities” to form “roads and transportation facilities,” from the viewpoint that both comprise transportation infrastructure, then “roads and transportation facilities” would rise in rank, followed by “housing,” “educational facilities,” “work facilities,” “medical facilities,” and “commercial facilities.”

The rank for “housing” can be somewhat expected given that houses are people’s most basic living and use spaces and that it is directly related to the keywords “complexification of housing functions” and “residential area per capita.” The rank for “educational facilities” reflects the experts’ view that measures for educational facilities are urgently needed in response to COVID-19 in that the educational facilities like schools are prime examples of spaces where the users gather in groups and the primary users of these spaces are underage students who are relatively vulnerable to COVID-19. Like “educational facilities,” the users of “work facilities” gather in groups, forming spaces where most members of society are engaged in productivity activities. Hence, its high ranking reflects the perception that a response to COVID-19 is urgent. Meanwhile, as “medical facilities” are at the forefront of the health response to COVID-19, one would expect them to rank highly; however, “medical facilities” ranked below “housing,” “educational facilities,” and “work facilities,” which suggests that the experts more strongly valued part-of-life measures in their selections. Despite the fact that COVID-19 infections and transmission occur most frequently in “commercial facilities,” their lower ranking than other facilities reflects the fact that society is already quite aware of their vulnerability, that public measures are being actively proposed and implemented, and that commercial facilities are not considered as essential for living as other facilities. “Road and transportation facilities” received some level of attention in that they can serve as a kind of “buffer” for responding to COVID-19 when it is difficult to implement adequate measures in existing facilities due to space limitations and the like. The result for “parks” reflects the rising demand for outdoor spaces owing to the vulnerability of indoor spaces to COVID-19, as well as growing interest in local parks in terms of “hyper-local living areas.” The result for “cultural and meeting facilities” reflects that these facilities overlap the most in meaning with the multi-use facilities, which are known to be the most vulnerable facilities to the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

5. Discussion

To systematically predict future changes in society and architectural and urban spaces due to COVID-19, this study conducted a Delphi survey with related experts to derive keywords representing major trends and issues that would lead changes in architectural and urban spaces in the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 eras, predict the change patterns for each keyword, and determine the architectural and urban spaces expected to undergo major changes.

The predictions of experts regarding the drivers of change can be interpreted as follows: While the rapid spread of “non-face-to-face” in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic restricted social activities to a considerable extent, as society finds appropriate measures to deal with COVID-19 and the recovery of social activities continues to be required over time, the influence of such keywords as “physical distancing” and “control of face-to-face contact,” which are part of “non-face-to-face,” will decrease. Meanwhile, the influence of “anti-virus air conditioning” will remain unchanged in that it can be applied in a way that does not restrict social activities, and it is also valid in case of a future outbreak of a similar infectious disease.

The predictions of experts regarding the social changes can be interpreted as follows: Despite the continued development of information and communications technology (ICT), the social spread of ICT has not taken place dramatically. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic acting as a catalyst, ICT-based services such as “online remote services,” “telecommuting,” “logistics industry (delivery services),” and “unmanned services” have spread rapidly throughout society, and this trend will continue into the future. The facets of social changes such as “moving distance/frequency,” “tourism industry,” and “sharing economy” are the trend of the times, so they may be suppressed in the short term by the COVID-19 pandemic, but in the long run they will regain their momentum as the trend of the times. However, in this trend of change, “disparities or polarization within society” caused by imbalances in accessibility to technology and information may intensify, and social attention would be needed.

The predictions of experts regarding the buildings to cities can be interpreted as follows: The “hyper-local living areas” and “temporary change of use” can be seen as architectural and urban spatial changes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and these changes will be deactivated in order to restore their previous state after the COVID-19 pandemic. The “complexification of housing functions” has been rapidly activated thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic with which social perception and behavior change as well, and the degree of activation will remain after the COVID-19 pandemic. The “public movement/rest spaces” and “green spaces” will become more active after the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of a long-term response to the COVID-19 and similar infectious diseases. Advances in ICT and building technologies, in line with the COVID-19 pandemic, will lead to changes in “intelligent buildings,” “flexible buildings,” and “smart city.” At the same time, the “urban – rural disparities” will deepen due to regional imbalances in accessibility to the technologies.

As for facilities or spaces expected to undergo many changes, the experts most frequently selected “housing” followed by “educational facilities,” “work facilities,” “medical facilities,” and “commercial facilities.” “educational facilities,” “work facilities,” “medical facilities,” and “commercial facilities” were regarded as the facilities where urgent changes were required in response to COVID-19, and numerous architectural experts and organizations have already presented related planning guidelines (American Institute of Architects Citation2020; Gensler Citation2020; Allen et al. Citation2020; MASS Design Group Citation2020). Conversely, measures for “housing” remain at the level of fragmentary proposals, such as the use of balconies in apartment buildings and improving air purification facilities. For this reason, establishing comprehensive architectural guidelines for housing in response to COVID-19 is necessary.

To facilitate communication between experts and researchers, this study limited the pool of experts to experts in Republic of Korea, and focused on Korean society throughout the research. In future studies, research on other societies needs to be conducted.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dongpil Son

Dongpil Son is a research fellow and a director of Sustainable Urban Research Group in Architecture & Urban Research Institute. He is interested in urban planning & design, urban regeneration, and CPTED, among others.

Minseok Kim

Minseok Kim is a professor at the Division of Architecture and Design, Pukyong National University in Busan, South Korea. He is interested in architectural/urban spatial analysis, architectural/urban planning & design, and architectural/urban computation, among others.

Youngjin Cho

Youngjin Cho is a research fellow and a director of Bigdata Research Group in Architecture & Urban Research Institute. He is interested in architectural/urban computation, architecture-IT conversion, and architectural/urban bigdata management, among others.

References

- Allen, J., E. Jones, A. Young, K. Clevenger, P. Samilifard, E. Wu, M. Luna, et al. 2020. Schools for Health: Risk Reduction Strategies for Reopening Schools. Harvard: School of Public Health.

- American Institute of Architects. 2020. “Risk Management Plan for Buildings.” https://www.aia.org/resources/6299432-risk-management-plan-for-buildings

- Barbarossa, L. 2020. “The Post Pandemic City: Challenges and Opportunities for a Non-Motorized Urban Environment.” An Overview of Italian Cases, Sustainability 12: 1–19.

- Cho, S., H. Baek, J. Han, and S. Lee. 2019. “An Analysis on the Expert Opinions of Future City Scenarios.” Regional Research 35 (5): 59–76.

- Choi, H., S. Eum, and M. Jun. 2006. “Study on Methodology for Predicting Future in the Digital Society.” Korea Information Society Development Institute 06-20 27–28.

- Dbouk, T., and D. Drikakis. 2020. “On Coughing and Airborne Droplet Transmission to Humans.” Physics of Fluids 32 (5): 053310.

- Florida, R., A. Rodriguez-Pose, and M. Storper. 2020. “Cities in a Post-COVID World, Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography (PEEG), 2041.” Utrecht University, 1–28.

- Gensler. 2020. “Back to the Office: Return Strategies for the Workplace and Office Buildings.” https://www.gensler.com/back-to-the-office

- Hamidi, S., S. Sabouri, and R. Ewing. 2020. “Does Density Aggravate the COVID-19 Pandemic? Early Findings and Lessons for Planners.” Journal of the American Planning Association 86 (4): 495–509.

- Hwang, J. 2020. “Untact Consumption Trends Triggered by the COVID-19 and Future Prospects.” Future Horizon 46: 28–35.

- Hwang, S. E., J. H. Chang, B. Oh, and J. Heo. 2021. “Possible Aerosol Transmission of COVID-19 Associated with an Outbreak in an Apartment in Seoul, South Kore A, 2020.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 104: 73–76.

- Im, H., S. Lee, N. Park, C. Park, E. Jeong, J. Ahn, A. Cho, and S. Jee. 2020. “Future Prediction and Promising Technology for the Post-COVID Era.” Korea Institute of S&T Evaluation and Planning 2020-01 1–28 .

- Kang, Y. 2008. “Comprehension and Application of the Delphi Technique, Korea Employment Agency for the Disabled - Nonscheduled Report, 1–17.

- Kim, M. 2021. “A Study on Architectural Approaches Corresponding to the Post-COVID Era: Proposal of Prevention of Infectious Disease Through Environmental Design.” Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea 37 (2): 67–75.

- Kim, J., D. Ki, and S. Lee. 2021. “Analysis of Travel Mode Choice Change by the Spread of COVID-19 : The Case of Seoul, Korea.” Journal of Korea Planning Association 56 (3): 113–129.

- Kim, J., J. Kim, S. Choi, Y. Cho, S. Kim, and J. Kim. 2021. “Prevalence of Respiratory Viral Infection Using Multiplex Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction.” Korean Journal of Family Practice 11 (3): 210–216.

- Kwon, K. S., J. I. Park, Y. J. Park, D. M. Jung, K. W. Ryu, and J. H. Lee. 2020. “Evidence of Long-Distance Droplet Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by Direct Air Flow in a Restaurant in Korea.” Journal of Korean Medical Science 35 (46 e415).

- Lee, J. 2001. Research Method 21: Delphi Method. Paju: Kyoyookbook, 1–2.

- Lee, Y., S. Byun, J. Park, J. Lim, J. Lee, and G. Park. 2011. Futures of National Territory (III). Sejong: Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements.

- Lee, S., and S. Choi. 2020. “Analysis of the Impact of COVID-19 on Local Market Areas Using Credit Card Big Data: A Case of Suwon.” Space and Environment 30 (3): 167–208.

- Lee, Y., I. Jeong, S. Lee, S. Byun, S. Lim, J. Lim, and B. Lim. 2009. Futures of National Territory (I). Sejong: Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements.

- Marr, B. 2020. 9 Future Predictions for A Post-Coronavirus World, Forbes. Accessed 3 April 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2020/04/03/9-future-predictions-for-a-post-coronavirus-world/?sh=5b4ead1b5410

- MASS Design Group. 2020. “Spatial Strategies for Restaurants in Response to COVID-19.” Accessed 8 May 2020. https://massdesigngroup.org/COVIDresponse

- Matthew, R. A., and B. McDonald. 2006. “Cities Under Siege: Urban Planning and the Threat of Infectious Disease.” Journal of the American Planning Association 72 (1): 109–117.

- Megaheda, N. A., and E. M. Ghoneim. 2020. “Antivirus-Built Environment: Lessons Learned from Covid-19 Pandemic.” Sustainable Cities and Society 61: 1–9.

- Menéndez, E., and E. García. 2021. “Urban Sustainability versus the Impact of COVID-19.” The Planning Review 56 (4): 64–81.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2020. “What is COVID-19?.” Accessed 2 March 2021. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/baroView.do?brdId=4&brdGubun=41

- Noh, S. 2006. “Delphi Technique: To Predict the Future Through Professional Insight.” Planning and Policy 2006.9 53–62.

- Tricarico, L., and L. D. Vidovich. 2021. “Proximity and Post-COVID-19 Urban Development: Reflections from Milan, Italy.” Journal of Urban Management 10: 302–310.