?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The heritage of historic villages is a valuable basic resource, and its utilization is a necessary means for cultural continuation and an important way for the development of villages to be differentiated. In this study, from the perspective of the coordinated development of the heritage utilization and social and economic benefits, historic villages’ heritage utilization was evaluated according to four factors: inheritance, development, society, and economy. Evaluation factors and their priorities were calculated after collecting data through the big data analysis of text, and an evaluation system was established. Ten historic villages in Guangzhou and Foshan, Guangdong Province, China were taken as examples, the data obtained through field surveys and interviews were used in a quantitative evaluation, and the advantages and disadvantages of the villages were analyzed. The evaluation results were compared with the villages’ development strategies, and strategies and methods conducive to improving the performance of heritage utilization were identified, providing a reference for future development.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

In China, traditional historic contexts are gradually disappearing and people are becoming alienated from the historic villages in which they live. Historic villages are developing a uniform style (Li Citation2007). Globalization, urbanization, and industrialization are eroding the cultural medium of historic villages, causing profound changes in the hearts of ordinary people living in villages (Zhang, Xiao, and Zhou Citation2015). Plans for the conservation of historic villages bear high resemblance to each other due to a lack of necessary research into patterns of spatial development (Liu and Liu Citation2016). The historic heritage of villages is a valuable basic cultural resource, and its utilization is necessary for cultural continuation and an important means of differentiating the development of villages.

Countries are considering ways to reinvigorate their rural heritage, and statements of heritage conservation have been issued. On 25 April 2014, for example, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, Ministry of Culture, Bureau of Cultural Heritage, and Ministry of Finance of China issued “Guidance on Effectively Strengthening the Conservation of Chinese Historic Villages.” The utilization of traditional village heritage should make use of various resources and adopt a range of methods, such as the development of tourism and cultural creative industries. Historic villages have unique architectural heritage, agricultural landscapes, folkways, and other intangible forms of cultural heritage. They have the advantage of tourism potential, which has gradually become an important means of rural economic development(Pollock‐Ellwand et al. Citation2009; Kazemiyeh, Sadighi, and Chizari Citation2016; Kastenholz et al. Citation2012; Green Citation2012; Artina, Dewi, and Yulianti Citation2018; Fan Citation2019). Folk customs have a heavy historic force, and they have been shown to trigger a sense of national pride (Silva and Leal Citation2015). To survive, they not only need to be inherited but also need to change dynamically to adapt to real social situations (Liao Citation2014). However, the commercialization of rural tourism should be carefully controlled to avoid the destruction of valued small-town or rural atmospheres(Fan, Wall, and Mitchell Citation2008; Zhao, Nie, and Zhang Citation2018). Problems have also arisen when the cultural creative industry has been used as a top-down planning tool for urbanization and promoting economic growth. For example, in Songzhuang, a famous artist village 28 km east of the Beijing city center, it has been difficult to achieve a balance between top-down and bottom-up planning (Zhao, Nie, and Zhang Citation2018). Considering cultural creative industries as a means of renewal, whether in Songzhuang, the largest art village in Beijing (Yi and Sun Citation2013), or in Xiaozhou Village in Guangzhou (Zacharias and Lei Citation2016), the good environment and cultural characteristics of the countryside have been important conditions for attracting artists to gather.

A heritage conservation evaluation of conservation plans can help reveal problems that may exist in the work of village conservation, and it plays an important role in the conservation and development of historical villages. Previous evaluation studies have focused on the impacts of heritage value, tourism, management models, outsiders, and World Heritage Site designation on the sustainable development of traditional villages(Ma, Li, and Chan Citation2018; Zhu et al. Citation2016; Lu and Li Citation2022; Luo and Qi Citation2019; Jiang Citation2008; Silva Citation2014; Li et al. Citation2019; Kim Citation2016). Most of the evaluations of heritage utilization related to heritage adaptive reuse(Alhojaly, Alawad, and Ghabra Citation2022; Rossitti, Oppio, and Torrieri Citation2021; Bosone et al. Citation2021). Additionally, the focus on heritage has shifted from the materiality of heritage to its role in sustainable development, with increasing attention given to the role played by local communities(Verdini, Frassoldati, and Nolf Citation2017; Guo and Sun Citation2016).

Previous studies have considered the effects of heritage tourism development, building heritage value evaluation and reuse, and specific conservation and management models from the perspective of individual cases. There has been no comprehensive comparative evaluation of the revitalization and utilization of heritage in multiple locations and no summary of universal problems based on a quantification method. In addition, no research has proposed a corresponding development strategy. From the perspective of coordinated development among the heritage utilization and social and economic benefits, this paper establishes an evaluation standard and system and evaluates 10 villages with different heritage utilization performance levels in Guangfo, Guangdong Province, China. The relationship between conservation measures and performance is analyzed, and heritage utilization strategies are proposed.

2. Methodology

2.1. Evaluation system

A system for evaluating historical and cultural village heritage utilization was developed using the big data analysis method described in (Li et al. Citation2019). The data were downloaded from the Tansi Thinktank website (http://tstktk.arch.scut.edu.cn/) developed by the research group. The method uses keyword retrieval and automatically downloads documents from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (https://www.cnki.net/); it then extracts the titles of these documents and performs word segmentation. To eliminate titles with low relevance, the vocabulary data are cleaned and de-noised using intelligent semantic analysis. Then, the term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) method is used to further process synonyms. Finally, vocabulary entries deemed invalid are excluded to obtain the effective vocabulary entries and their frequency of occurrence.

The keyword “historic village utilization” (传统村落活化利用) was queried on 18 September 2020. The resulting search of the full text of the literature published in all academic fields yielded 7,813 related papers. Word segmentation of the titles of these papers by the software yielded 28,736 words. After excluding words with a frequency of less than 1% and those with low relevance, 65 words remained. A further 27 common words, such as “problem,” “thoughts,” “influence,” “cases,” “feature,” and “value” were also excluded. The final 24 words were classified according to the theoretical analysis and the evaluators’ subjective experience; for example, “engineering” and “construction” were placed in the “development” category.

The first-, second-, and third-level factors are denoted by k, i, and p, respectively, and the sequence, word frequency, and priority of the etymology are denoted by j, N, and T, respectively. Thus, Nj represents the frequency of sequence j in the total number of documents. The frequency of a second-level evaluation factor is calculated as the sum of the frequencies of all related words (Formula 1). The priority of an evaluation factor is determined as the ratio of the frequency of a second-level factor to the sum total frequency of all factors at that level (Formula 2). Accordingly, the priority of a first-level factor is obtained as the sum total of the priorities of the encompassed second-level factors (Formula 3). The priority of third-level factors is calculated similarly (Formula 4). presents the resulting evaluation system.

Table 1. Performance evaluation system for historic villages’ heritage utilization.

2.2. Evaluation criteria

The definitions and data sources for the historic village utilization evaluation factors are listed in . Field surveys were conducted and data were collected from sources including application reports, local yearbooks, government work reports, and face-to-face interviews with village officials. For quantifiable factors such as the proportion of indigenous people and the tourism development benefits, the quantity was used for grading. For unquantifiable factors such as the authenticity of the folkways carrier and the heritage vitality, qualitative methods were used for grading. Each third-level factor was evaluated. Each factor was divided into 10 points, and its number or quality was divided into five grades (excellent, good, average, below average, and poor), corresponding to 10–9, 8–7, 6–5, 4–3, and 2–0 points, respectively.

Table 2. Definitions and data sources for historic village heritage utilization evaluation factors.

2.3. Case studies

The application for official heritage site designation reports of historic villages in 16 jurisdictions in the Guangzhou and Foshan Area, Guangdong Province were analyzed and field surveys of representative villages were conducted. Ten typical villages were selected as the evaluation sample: Daling, Shawanbei, Langtou, Xiaozhou, Qiangang, Huangpu, and Liantang in Guangzhou and Daqitou, Songtang, and Bijiang in Foshan. These villages cover three types of conservation and utilization of historic villages, namely conservative, balanced, and developed (see ), and show the different grades of utilization performance.

Table 3. Types of protection and utilization of sample villages.

Shawanbei Village is an Class 4A scenic spot with relatively mature tourism development and is a cultural tourism village. Although the number of traditional style buildings is in the middle level among all villages, the core tourism area has undergone coordinated transformation, and the intangible cultural heritage of the village has been excavated and publicized. Bijiang, Xiaozhou, and Huangpu have almost become urban villages, and their economies depend on industrial parks and houses for rent. Although a few ancestral halls remain, villagers have demolished old houses to build new modern houses, which is difficult to improve.

The economic conditions of Daling and Songtang are relatively good. A large number of traditional public buildings remain in the villages, and the proportion of aboriginal people is very high. Therefore, folk customs are still well inherited. At present, the tourism infrastructure and tourism supporting facilities in Daling have not been improved, and tourism development is still in the primary stage. No relevant publicity and promotion work has been carried out, and there are no tourism benefits. The infrastructure of Songtang is in the process of transformation, and cultural tourism is developing well, with 300,000 tourists visiting the village in 2019.

Daqitou and Langtou, having a long history, are far from the core development area of the city. The government spent heavily on the maintenance and repair of historic buildings in past 15 years, so their traditional style buildings have been preserved intact. These tangible cultural resources have the most advantages and belong to the architectural heritage of villages. In recent years, after the new rural construction all over China, the trend of hollowing out has not slowed and people no longer live in the old villages. Traditional buildings are of high quality, but few new features are implanted. Because the tourism theme of Langtou was mainly Confucianism culture education, its adaptation range was small, and tourism publicity thus did little to grow the number of tourists. The two villages have not yet entered a virtuous cycle of mutual conservation and development. Qiangang’s traditional-style core protected area is also relatively complete, but much of it has been abandoned and collapsed. There is a huge gap in conservation funds, which cannot support utilization and development. The natural environment of Liantang is beautiful, and the geomantic pattern of its layout has high historical value. It is therefore classified as an environmental landscape village. However, the village is small in size and has a small permanent resident population. Only a few ancestral halls and private houses remain, facing the risk of underutilization.

2.4. Comprehensive evaluation

Scores of first- and second-level factors and total scores per village were obtained using the multi-objective linear weighted function (Formula 6).

Here, M is the total score of the comprehensive evaluation and is the score of a single index p.

3. Results

3.1. Overall evaluation

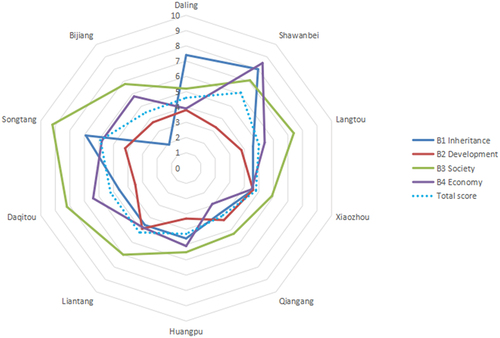

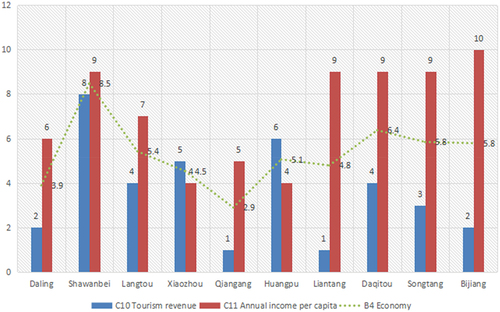

The factor scores of layers A and B were calculated using the weights (). shows that the various villages had large differences in inheritance, economic, and social factors, whereas the scores of development factors were all low, and the overall performance of utilization was thus moderate, with the average score being 5.0. Only the total scores of Shawanbei and Songtang exceeded 6.0. Qiangang had the lowest score, less than 4.0.

Table 4. Evaluation results of 10 historical villages.

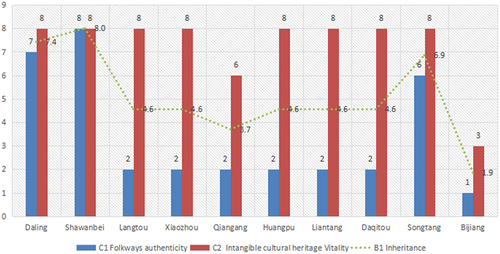

3.2. Inheritance

Most villages had low scores of inheritance factors, with a mean score of 5.1 (). Daling, Shawanbei, and Songtang scored highest overall, and Bijiang the lowest. The authenticity of the folkways carrier was calculated according to the stability degree of the inheritance site of the intangible cultural heritage and the inheritance team of the folk custom activities. The authenticity of the folkways carrier in most villages was generally poor, with seven villages scoring below 2.0. The heritage vitality was evaluated according to the use of major historic buildings and sites, the inheritance of intangible cultural heritage, and the frequency and scope of the influence of the activities. The scores of heritage vitality were good, with eight villages achieving a score of at least 8.0. The villages scored highly on the authenticity of their folkways carrier because they have designated intangible cultural heritage heirs and venues. The other villages scored lower because they do not have designated heirs for intangible cultural heritage. However, the heritage of most villages is well inherited and shows vitality. Qiangang and Bijiang obtained lower scores for heritage vitality due to their average conservation practices. Although a few historical buildings in Bijiang are well preserved, the folk activities in the village have almost completely disappeared.

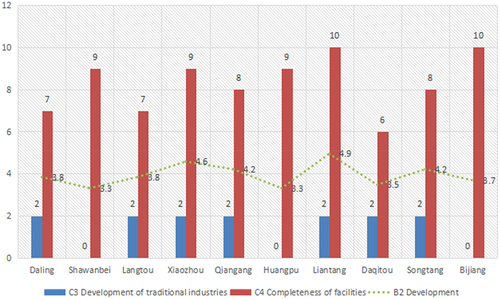

3.3. Development

The 10 villages’ evaluation scores for development factors are shown in . The mean value was only 3.9. All villages scored low on the development of traditional industries. Agriculture continues to be prevalent in most villages, whereas the handicraft industry has few workers.

Since the construction of new rural infrastructure, the infrastructure of each village has greatly improved, but the construction situations of each village are quite different (see ). Households in most villages are connected to a water supply, drainage, and power facilities, but some villages, such as Bijiang, Langtou, and Xiaozhou, have messy outdoor pipelines, which not only have hidden safety hazards and lead to water pollution but are also unsightly.

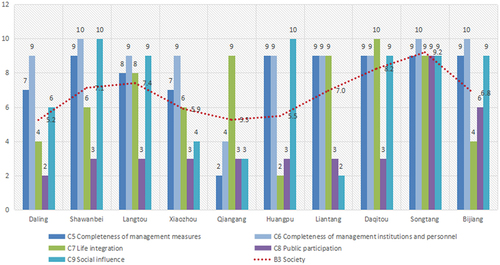

3.4. Society

The 10 villages’ evaluation scores for society factors were good, with a mean value of 6.6 (). In general, management agencies and personnel completeness were good. Other social factors varied greatly from village to village. The evaluation scores were worst for public participation.

Most villages had effective management methods that were well implemented. For example, the land development and utilization of the village and surrounding plots has been controlled in Daqitou, and the legal management of historical and cultural reserves has been strengthened in Langtou. However, in Bijiang a lack of effective management has led to the construction of a large number of modern and large-scale peasant houses, destroying the overall style of the village.

Most villages have established institutions and are equipped with professionals or have full-time management personnel. Only Qiangang is incompletely equipped with institutions and professionals.

Langtou, Qiangang, Daqitou, Liantang, and Songtang are located in remote areas with a weak industrial base and most of their populations are indigenous people. The tourism development of Shawanbei and Xiaozhou was earlier, and some indigenous people have returned to the villages. Most of the other villages have been affected by industrialization, and there are many factories. There are many migrant workers in the villages, and their scores for living integration were low.

Villagers in most villages have few opportunities to participate in management activities, so scores for public participation were low. Songtang and Langtou are better in this regard. In Songtang, self-government organizations, such as the Management Committee for Protection and Tourism Development and the Hanlin Cultural Association, have been set up to discuss and make decisions about major issues.

As Shawanbei, Huangpu, Daqitou, and Bijiang not only have honorary titles above the provincial level, but also often organize cultural festivals to attract tourists, they had high scores for social impact. In Langtou, a ceremony for the first time using a brush attracted students from more than 10 schools in Huadu, Sanshui, Nanhai, and elsewhere ()).

3.5. Economy

The 10 villages’ scores for economic factors are shown in . Among them, Shawanbei had the highest overall score and Qiangang had the lowest overall score. The villages have exerted their advantages to develop tourism, and Shawanbei and Langtou have achieved good results (). Shawanbei allows visitors to experience Lingnan folk culture in the form of education and entertainment that combine humanities and historical knowledge, ancient building excursions, and a traditional dining experience. It scored highest on tourism revenue. The tourism company in Langtou is responsible for the integration and promotion of tourism resources, and has renovated ancient buildings into academies, tea houses, Hanfu halls, historical exhibition halls, anti-drug education bases, and traditional craft exhibition halls.

Except for Huangpu, Xiaozhou, and Qiangang, the per capita income of the villages is more than RMB10,000. Bijiang has the most developed industry, with a per capita income of RMB28,000. Since China’s opening-up reform, the Bijiang community has been vigorously attracting investment and developing local industries. The remaining villages, such as Langtou, Daqitou, and Qiangang, rely mainly on agriculture, forestry, and fishery. Shawanbei has a small number of industries.

4. Discussion

To realize the heritage vitality of historic villages, it is necessary to understand that the local government has a primary responsibility for conservation and development and to establish a working mechanism that incorporates government leadership, villagers’ action, social participation, and expert guidance. It is necessary to clarify the rights and objectives of conservation, integrate resources to mobilize enthusiasm, ensure that conservation and development work are carried out together, and avoid excessive development.

4.1. Inheritance

Heritage conservation and inheritance in villages provide tangible and intangible foundations for future cultural continuity and development. Tangible heritage, such as protected traditional buildings, should be functionally renewed to integrate with modern life.

Intangible cultural heritage needs the support of good material space and cannot exist independently from the material world. The carriers of folk custom activities in many villages have been occupied or destroyed, and some space thus needs to be reserved in the protection and planning scheme stage to create a premise for the inheritance of intangible cultural heritage activities. After a comprehensive and real recording of all the space sites in villages, the identification system should be improved and the cultural space archives should be established. The preservation status of cultural spaces should be screened, and those spaces with good preservation status should be listed as cultural conservation units and maintained and renovated in the future according to traditional construction techniques. Some space needs to be reserved during the conservation planning phase to create prerequisites for intangible heritage activities, such as the square space needed for large-scale folk activities, drama performance viewing venues, handicraft production and exhibition workshops. Due to changing ideas and economic constraints, young people are reluctant to do intangible heritage work. Most of the existing inheritors are the elderly, and much intangible heritage is in danger of disappearing. Inheritor guarantee systems should be improved to attract young people to learn about and inherit intangible cultural heritage.

4.2. Development

The labor force had been lost in most of the villages, and there were few traditional handicraft enterprises. Some villages with good geographical locations have taken advantage of their location and land to develop secondary industry, which greatly affects the village features. Only public buildings such as ancestral halls have been retained in most villages, and the villagers can make much money by renting out their houses. Some villages have excellent conservation of natural and human landscape resources, and developing rural tourism is a suitable development approach. Local governments should do a good job of protection, investment promotion, and scientific development, while addressing the needs of modern tourism to fully display their unique cultural resources to tourists and improve villages’ vitality.

After the construction of the “beautiful countryside” in recent years, most villages have good infrastructure conditions. However, the existing infrastructure in most villages can only meet the daily needs of the villagers. The gap between the needs of tourists and incomplete tourism infrastructure has become a major contradiction. Facilities, such as a tourist service center, a parking lot, map signage, an attraction identification system, trash cans, public event venues, and public toilets, are required. It is advisable to renovate the existing buildings and spaces as much as possible to establish public facilities that are consistent with the overall style of ancient villages. Modern water supply and drainage in villages should respect the wisdom of the ancestors and incorporate ancient canals and wells that have survived from ancient times. Power and communication facilities should be uniformly wired, and multiple trenches should be combined into one. Garbage stations should be planned uniformly, set up centrally, and cleaned regularly.

4.3. Society

The evaluation results show that there were few opportunities for villagers to participate in conservation and management. The enthusiasm of villagers should be brought into play. Aboriginal people are the main participants in the conservation and construction of historic villages, the carriers of intangible culture, and the beneficiaries of revitalized development. These multiple identities of aboriginal peoples determine that they should enjoy the rights of participation, decision-making, supervision, and management in the conservation and development of villages. These duties should be exercised through the village committee, which is a grass-roots organization for protecting and developing a historic village. The village committee is responsible for publicizing relevant laws and regulations, strengthening the protection and management of villages, and cooperating with relevant departments in the registration of material cultural heritage and the census of intangible cultural heritage.

The completeness of the management measures, institutions, and personnel in most villages is good, but multi-sectoral collaborative management should be strengthened. The Ministry of Nature Resources of China must play a role in formulating protection and development plans, establishing written conservation procedures and records for villages, supervising the implementation of protection projects, organizing acceptance inspections, and coordinating relevant departments, such as those responsible for cultural relic protection and land resources.

Some villages have insufficient social influence, and their publicity efforts should be strengthened. To raise awareness of ancient villages, increase the pride of the villagers, enhance the public’s understanding of traditional culture, and increase awareness of the importance of protection, local governments should showcase the charm of historic villages through online and offline methods and widely publicize celebrities and stories, cultural relics, architectural features, landscapes, intangible cultural heritage, and protection significance. Through rich tourism products and educational services, the audience of a historic village culture would be expanded, and the effects on different social groups such as students, enterprise employees, government officials, and the elderly would be enhanced. By increasing network interaction and sharing among “fansi” groups, more people can create products taking the traditional village as the material, and relevant works would be integrated into the open public landscape system to increase participation. At the same time, we suggest striving for recognition from government officials and the mainstream media at all levels.

4.4. Economy

The funds for protecting historic villages mainly come from fiscal support from governments at all levels. The allocation and acceptance of funds by national ministries and commissions and governments at all levels are usually in an independent state. Villages should reasonably plan construction projects, manage and participate in overall planning, and change the previous situation of multiple plans acting independently. The development of the tourism industry has also become an important source of funds, but the tourism industry of most villages has low efficiency and cannot meet the demands of protection investment.

Adopting multiple methods to raise funds and exploring a diversified development model are conducive to giving play to the strengths of multiple parties and jointly creating benefits. Examples include introducing private capital, attracting investment, and promoting non-governmental organizations, such as the Ancient Building Protection Association, to use their resources and funds to participate in projects in the form of investment. The enterprise has important advantages in capital management and market operation. Shawan Ancient Town Tourism Company built a microscale store operation platform, and by linking to Shawan local culture, the company launched “Guangzhou music clip”, “Royal Fu bag”, “Paper-cutting ice cream”, “Shawan characteristic smouldering food pot”, “Ancient town characteristic cultural and creative gift package”, and other products and online and offline sales, making good profits. Villagers can become owners of shares, enabling village protection to have economic benefits. Alternatively, villagers’ old houses can be converted into shares with dividends paid regularly. Low-interest loans can be obtained through banks in accordance with national policies, and other methods of fundraising can also be used to raise funds, such as raising money from the general public for a specific project.

5. Conclusion

From the perspective of coordinated development among the heritage utilization and social and economic benefits, this study describes a method of evaluating the utilization of Chinese historic villages making use of 4 evaluation elements (inheritance, development, society, and economy) and 11 evaluation indicators. Ten villages with different heritage conservation performances in Guangzhou and Foshan, Guangdong Province, were selected as case studies. The evaluation results show that the overall performances of the 10 villages were all average. Shawanbei performed best but scored only 6.2. The best performing of the four factors was the social factor and the worst was the development factor. Except for development factors, Shawanbei and Songtang scored highest and Qiangang and Bijiang scored lowest. The authenticity of the folkways carrier was poor, but heritage vitality was good. All of the villages scored low on development factors, especially for traditional industry. The completeness of management agencies and personnel was good overall, but there were large differences among the scores for other social factors. The mean value for tourism revenue was low, and the revenue differed greatly across villages.

Measures and strategies conducive to the utilization of village heritage can be derived by comparing the quantitative evaluation and analysis of historic village heritage utilization with the conservation and development measures of each village. For inheritance, material cultural heritage can be identified, recorded, and combined with modern functions and living spaces, and spaces and systems for the display and reproduction of intangible cultural heritage can be reserved. For development, it is appropriate to give play to historical and cultural advantages and develop traditional industries to encourage villagers to start businesses relying on these industries. Local governments should attach importance to attracting investment and displaying local culture in light of modern tourism needs. Public facilities and municipal infrastructure should be improved to improve the quality of environmental facilities in villages. Management institutions and management methods that focus on the development of villagers’ enthusiasm, multi-department collaborative management, and strengthening of publicity would increase public participation, integration, and social influence. Diversified financing and the development of the tourism industry would increase the average annual income of villagers.

In this study, the performance evaluation of the heritage for the utilization of historic villages was limited to southern China, and more extensive and in-depth research is required for the analysis of the commonalities and differences with other regions. Each historic village has different cultural characteristics, and case development according to local conditions needs to be addressed in future work.

Author contributions

L.E. (Erwei Li) undertook the investigation and data analysis. H.Y. (Yi Huang) proposed the original concept and methods and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by the National Key R&D Program of China (Monitoring System of Protective & Utilization and Management System Apply to the Value System of Traditional Villages; Grant No. 2019YFD1100903) and the Academician Workstation project of the Tulou Management Committee of Nanjing County, Fujian Province, China, ”The Research on the Integration of the Nanjing Tulou Heritage Protection and Rural Revitalization” (No. D5220890).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yi Huang

Yi Huang, associate professor, School of Architecture, State Key Laboratory of Subtropical Building Science, South China University of Technology, 381 Wushan, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China Erwei Li, assistant architect, Gemdale Group Co., Ltd, Floor 41, 148 Xingang East, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China

Erwei Li

Yi Huang, associate professor, School of Architecture, State Key Laboratory of Subtropical Building Science, South China University of Technology, 381 Wushan, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China Erwei Li, assistant architect, Gemdale Group Co., Ltd, Floor 41, 148 Xingang East, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China

References

- Alhojaly, R. A., A. A. Alawad, and N. A. Ghabra. 2022. “A Proposed Model of Assessing the Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings in Historic Jeddah[J].” Buildings 12 (4): 406. doi:10.3390/buildings12040406.

- Artina, S. V., P. W. Dewi, and T. R. Yulianti. 2018. “SWOT Analysis of the Development of the Tourist Cibuntu Village, Cibuntu Regency West Java[C].” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 145(1): 012074. IOP Publishing.

- Bosone, M., P. De Toro, L. Fusco Girard, A. Gravagnuolo, S. Iodice, et al. 2021. “Indicators for ex-post Evaluation of Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse Impacts in the Perspective of the Circular economy[J].” Sustainability 13 (9): 4759. DOI:10.3390/su13094759.

- Fan, C. N., G. Wall, and C. J. A. Mitchell. 2008. “Creative Destruction and the Water Town of Luzhi, China[J].” Tourism Management 29 (4): 648–660. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.07.008.

- Fan, X. K. 2019. Development and Conservation of Tourism Resources in Historic Villages[M]. Beijing: Beijing Press. In Chinese.

- Green, M. D. 2012. “A Geographical Analysis of the Atalanti Alluvial Plain and Coastline as the Location of A Potential Tourist Site, Bronze through Early Iron Age Mitrou, East-Central Greece[J].” Applied Geography 32 (2): 335–349. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.05.010.

- Guo, Z., and L. Sun. 2016. “The Planning, Development and Management of Tourism: The Case of Dangjia, an Ancient Village in China[J].” Tourism Management 56: 52–62. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.03.017.

- Huang, Y., E. W. Li, and D. W. Xiao. 2021. “Conservation Key Points and Management Strategies of Historic Villages: 10 Cases in the Guangzhou and Foshan Area, Guangdong Province, China[J].” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 2021: 1–12.

- Jiang, H. P. “A Case Study on Xidi and Hongcun Village: Development Model of Rural Tourism of Ancient Village in Southern Anhui[C].” Euro-Asia Conference on Environment and Corporate Social Responsibility - Tourism, MICE and Management Technique Session.Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin. 2008:67–74.

- Kastenholz, E., M. J. Carneiro, C. P. Marques, and J. Lima. 2012. “Understanding and Managing the Rural Tourism experience—The Case of a Historical Village in Portugal[J].” Tourism Management Perspectives 4: 207–214. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2012.08.009.

- Kazemiyeh, F., H. Sadighi, and M. Chizari. 2016. “Investigation of Rural Tourism in East Azarbaijan Province of Iran Utilizing SWOT Model and Delphi Technique.” Journal of Agricultural Science & Technology 18 (4).

- Kim, S. 2016. “World Heritage Site Designation Impacts on A Historic Village: A Case Study on Residents’ Perceptions of Hahoe Village (Korea)[j].” Sustainability 8 (3): 258. doi:10.3390/su8030258.

- Li, J. 2007. “An Analysis of the Causes for the Imbalance of Modern Ecosystem in the Ancient Huizhou Villages[J].” Journal of Anhui University (Philosophy & Social Sciences) 3: 48–51. Chinese.

- Li, X., Z. H. Wang, B. Xia, S. C. Chen, and S. Chen. 2019. “Testing the Associations between quality-based Factors and Their Impacts on Historic Village tourism[J].” Tourism Management Perspectives 32: 100573. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100573.

- Liao, Y. “Village Folk Custom Changes under Tourism Development[C].” 2014 International Conference on Education Technology and Social Science. Atlantis Press, 2014: 398–402.

- Liu, B. T., and Q. Liu. “Research on Protection Methodology of Historic Villages and Towns Based on Spatial Development[C].” Energy, Environmental & Sustainable Ecosystem Development: International Conference on Energy, Environmental & Sustainable Ecosystem Development (EESED2015). 2016.

- Lu, K. R., and W. H. Li. 2022. Research on the Conservation and Revitalization of Historic Villages in Zhejiang Province in China[M]. Wuhu: Anhui Normal University Press. In Chinese.

- Luo, Y. B., and L. H. Qi. 2019. “Construction and Practice of a Conservation Plan Implementation Evaluation System for Historic villages[J].” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 18 (4): 351–361. doi:10.1080/13467581.2019.1661843.

- Ma, H., S. Li, and C. S. Chan. 2018. “Analytic Hierarchy Process (Ahp)-based Assessment of the Value of non-World Heritage Tulou: A Case Study of Pinghe County, Fujian Province[J].” Tourism Management Perspectives 26: 67–77. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2018.01.001.

- Pollock‐Ellwand, N., M. Miyamoto, Y. Kano, and M. Yokohari. 2009. “Commerce and Conservation: An Asian Approach to an Enduring Landscape, Ohmi‐Hachiman, Japan[J].” International Journal of Heritage Studies 15 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1080/13527250902746021.

- Rossitti, M., A. Oppio, and F. Torrieri. 2021. “The Financial Sustainability of Cultural Heritage Reuse Projects: An Integrated Approach for the Historical Rural landscape[J].” Sustainability 13 (23): 13130. doi:10.3390/su132313130.

- Silva, L. 2014. “The Two Opposing Impacts of Heritage Making on Local Communities: Residents’ Perceptions: A Portuguese case[J].” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (6): 616–633. doi:10.1080/13527258.2013.828650.

- Silva, L., and J. Leal. 2015. “Rural Tourism and National Identity Building in Contemporary Europe: Evidence from Portugal[J].” Journal of Rural Studies 38: 109–119. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.02.005.

- Verdini, G., F. Frassoldati, and C. Nolf. 2017. “Reframing China’s Heritage Conservation Discourse. Learning by Testing Civic Engagement Tools in a Historic Rural village[J].” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (4): 317–334. doi:10.1080/13527258.2016.1269358.

- Yi, X., and M. Sun. “Innovative Way for Cultural Creative Industry Development in China’s Urbanization Process - Case Study of Songzhuang in Beijing[C], 6th Knowledge Cities World Summit (KCWS).” Lookus Scientific. 2013:227–237.

- Zacharias, J., and Y. Lei. 2016. “Villages at the Urban fringe–the Social Dynamics of Xiaozhou[J].” Journal of Rural Studies 47: 650–656. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.05.014.

- Zhang, D., H. Xiao, and H. W. Zhou. 2015. “Research Summary of Conservation and Development of China’s Historic and Cultural Town[J].” Urban Planner 32 (S2): 152–158. Chinese.

- Zhao, F., R. Nie, and J. Zhang. 2018. “Greenway Implementation Influence on Agricultural Heritage Sites (AHS): The Case of Liantang Village of Zengcheng District, Guangzhou City, China[J].” Sustainability 10 (2): 434. doi:10.3390/su10020434.

- Zhu, X. M., Y. G. Lin, J. H. Fan, and G. G. Wang. 2016. “Research on the Situation and Protection Utilization of Ancient Villages in Guangdong Province[J].” Journal of South China University of Technology(Social Science Edition) 18 (6): 105–113. In Chinese.