ABSTRACT

The traditional Chinese gardens are an essential source of inspiration for Wang Shu’s architectural creations. Taihu stone is a porous, irregularly shaped rock used to compose mountain landscapes in traditional gardens, which informs the architectural interpretation of Wang’s gardening philosophy. This paper illuminates Wang’s design approach, in particular the way he abstracts the shape and form of Taihu stone in his works creating architecture that embodies the qualities of tradition. We examine seven of his architectural works built between 2003 and 2018 where the architect used the Taihu stone in two principal manners. The first is a formal conceptualisation that is reflected in the overall form of the building named “Taihu-house”. A total of 19 “Taihu-houses” were founded in Wang’s works through three strategies: addition, insertion, and subtraction, of which the “addition” including 14 “Taihu-houses” is the most representative design. The second is using the Taihu stone as an inspiration for surface design such as the shape of windows or doors. Several walls with stone-shaped openings are further used to recreate a traditional promenade experience. Wang’s application of Taihu stone in his architectural works creates continuity with the traditional values of Chinese architecture while working within a modern aesthetic.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and AIM

Ji Cheng, a Ming Dynasty architect, suggested that there are no gardens without stones and no stones without gardens (Liu Citation2015). This implies that the artificial mountainous landscape built of stones is the most essential component of traditional garden composition when juxtaposed with the other major elements: architecture, water, and plants (Peng Citation1988). In traditional Chinese philosophy and culture, the shanshui idea (literally mountains and water) is presented as a theme and symbol to incarnate the ideal harmony between nature and humans (Ping and Ozawa Citation2021). The reinterpretation of the mountain element is very relevant in today’s debate topic of exploring the continuity of traditional gardens in modern architecture.

The contemporary Chinese architect Wang Shu, the 2012 Pritzker Architecture Prize winner, has been committed to research on the modernization of traditional gardens. As he explained in To Build a House (Citation2016), “in the architecture of traditional Chinese literati, there are more important things than building houses.” In other words, Wang’s architectural philosophy echoes traditional garden aesthetics since he considers that natural elements such as water and mountains are more important than buildings (Wang Citation2016). Especially the mountain element has influenced his architectural plastic creation, in which the Ningbo History Museum imitates the natural geometry of large mountains in traditional landscape paintings such as Fuan Kuan’s Travelers Among Streams and Mountains (Wang Citation2009). The building – the geological texture, the precipitous walls, and rocky outlines – embody Wang’s philosophy that the built environment should narrate about the natural forms and integrate into the natural surroundings (Edward and Guang Citation2012).

The Ningbo History Museum represents Wang’s design approach to the “big mountain” and his small-scaled building employs another formal philosophy on the natural stone form (Wang Citation2009). Then, the Taihu stone echoes this idea due to its entire form, which is shaped like a reduced version of the mountain. It is the most famous type of stone that has been used for garden mountain landscapes (Hardie Citation1988). Wang abstracted and transformed its unique, variable shape and form to create an overall building form in a modernistic approach. As Mohsen Mostafavi stated that the combination of Chinese and Western traditions with new and old influences creates a unique fusion of different sensibilities, However, Wang’s designed buildings are deeply rooted in modernism (Perlez Citation2012). In other words, his design approach to rethinking the Taihu stone has become a paradigm to echo this issue. This article aims to illuminate Wang Shu’s approach to design by investigating how Taihu stone is re-used and re-imagined in Wang’s work reviving the continuity of traditional Chinese architecture’s values.

1.2. Review

Previous studies on Wang Shu published in international forums or journals often examined his architectural characteristics and design philosophy in the context of Western theories. For instance, Ding (Citation2020) studied the return of repressed subjectivity in Wang’s architecture, relying on Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s emphasis on bodily experience and Michel Foucault’s analysis of power. Chau (Citation2018) interpreted Wang Shu’s design as an ecological practice according to the phenomenological theory of Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Juhani Pallasmaa. Moreover, some studies have discussed Wang’s architecture practice and design elements in terms of Western critical regionalism (Thorsten Citation2009; Wang Citation2018; Zhu, Sun, and Zhang Citation2021), architectural urban topology (Jin Citation2021; Yu, Zhang, and Wang Citation2017), and western architectural avant-garde theory (Chau Citation2015). However, little attention has been paid to the design ideology of mountain imagery in traditional Chinese gardens embodied in his architecture. To further discuss the architect’s comprehension of the garden mountain element, this study focuses on the Taihu stone, which is the most representative example of the gardening influence on Wang’s works, and analyse its formal Taihu-house practice on the architectural plastic design as well as its surface intervention on window and door openings.

2. Method

This study adopts the case studies method to explore this subject matter. Wang’s seven representative projects built between 2003 and 2018 are collected for the following analysis. Those projects include Five Scattered Houses (2003–06), Xiangshan Campus second phase of China Academy of Art (2004–07), Ningbo History Museum (2003–08), Old Town Conservation of Zhongshan Street (2007–09), Shili Hongzhuang Cultural Center (2012–18), Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion (2010), and Waterfront and Mountain Residence Hotel (2013–14). In those works, Taihu stone is transformed in various ways such as “Taihu-house” forms and Taihu stone-inspired openings. This research carefully analyses those buildings and investigates how these different Taihu stone concepts work with other architectural elements to form Wang’s contemporary garden architecture.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows (). In section 3, it reviews the spatial characteristics and two design methods of Taihu stone in traditional Chinese gardens. Section 4, clarifies the reinterpretation of Taihu stone in architectural modernity by focusing on Wang’s understanding of natural stone form. In sections 5 and 6, this research seeks to analyses the practice of Taihu stone in the architect’s several designs in terms of its two general manners: formal conceptualisation and surface interventions. Simultaneously, this study tries to discuss and explore the relevance between the traditional qualities of Taihu stone and Wang’s designs in the context of spatial characteristics and formal innovation, thus elucidating the significance of Wang Shu’s design approach with regard to the continuity of traditional Chinese architecture’s values in contemporary form aesthetic.

3. Taihu stone in the traditional Chinese garden

Traditional Chinese gardens, although built by humans, seek to imitate the beauty of nature created by God (Wu, Chen, and Wu Citation2012). Rather than organising a garden by formal arrangements of natural elements (conquering nature to the pursuit of artificial beauty), the Chinese garden promotes natural beauty, and subtly combines artificial and natural elements (Zhou Citation2005). In the design of Chinese gardens, there are four essential elements: rocks, water, buildings (pavilions), and plants (Bedingfeld Citation1997). Traditional gardeners always use these elements to build architectural landscapes that are in a harmony with nature. For instance, rocks are the main element to compose artificial mountain landscapes, and mountains and water are considered the key components of the Chinese conception of a landscape (Bedingfeld Citation1997). Taihu-stone is the most famous type of rock that has been used for this purpose since ancient times (Hardie Citation1988). It has an unusual, organic appearance with a porous structure formed by water erosion (). The surface holes vary in size and shape and form “deep hollows”, “eyeholes”, “twists”, and “strange grooves” (Liu Citation2015). Characterized by a special form, Taihu stone has high ornamental value and was well-liked by ancient Chinese artists. Garden architects use various forms of mountain landscapes to enhance the atmosphere of the outdoor space. There are two main methods of using Taihu stone for creating mountain scenery in Chinese gardens: Duoshan (掇山) for artificial mountains and Zhishi(置石) for sculptural rockery landscapes (Wei Citation2009).

3.1. Duoshan: big artificial mountain landscape

Duoshan methodology builds an artificial mountain by piling up many small stones to create a larger artificial mountain landscape (Liu Citation2015). The principles of creating artificial mountains can be understood only by landscape architects who have a thorough understanding of traditional garden design (Liu Citation2015). The garden architect not only needs to consider how to create the artificial mountain, but must also focus on the impact that it will have on visitors and the meaning and spatial atmosphere that the garden radiates. The Duoshan gardening method offers two ways of experiencing the artificial mountains. The first is to simply appreciate the sculptural scenery of a long, large mountain scene where one can walk around the landscape, viewing it from different angles and distances (). The second method allows visitors to access the interior of the mountains and experience a different atmosphere by walking up and down the rocks (). This kind of design mimics the feeling of climbing a natural mountain. The caves that are created in the rock allow visitors to appreciate views of the surrounding gardens framed by the stone.

3.2. Zhishi: single sculptural rockery landscape

In contrast, the Zhishi gardening methodology reveals the natural beauty of the form of the single stone. In this methodology, the mountain landscape is created by using a single large stone. The unique shapes and high ornamental value of Taihu stone make it a popular material as a single rockery in traditional gardens. In his book YuanYe, Ji Cheng claimed that such stone can convey the emotions of the garden. A single Taihu stone can be placed in three different ways: “special placement”, “symmetry placement”, and “scattered placement” () (Shen Citation2018). In “special placement”, a single Taihu stone is placed in the corner of the courtyard to create a visual connection with other elements of the garden. In “symmetry placement”, two Taihu stones are placed symmetrically, usually in the center of a courtyard with other, smaller stones being arranged around them. The “scattered placement”, presumes one big Taihu stone placed in the middle of the garden with smaller stones carefully scattered around it to enhance the atmosphere of the garden. Whichever method the garden’s architect chooses, the rockery landscape of the garden is enriched.

Figure 5. a: Special placement of Taihu stone in the Yuyuan Garden © Gisling, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons; b: Symmetry placement of Taihu stone in the Lion Grove Garden © King of hearts, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons; c: Scattered placement of Taihu stone in the lion grove garden © King of Hearts, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia commons.

However, it is worth noting that the size of the rockery landscape is not a necessary condition to distinguish Zhishi and Duoshan. In the Yunlin Stone Spectrum of the Song Dynasty, Du Wan writes, “Even a stone with the size of a fist can be comparable to the magnificent view of a large mountain. The larger-sized stone can be arranged in the garden, whereas, the small ones can be placed on the table as a bonsai decoration.” (Du Citation2009) In others words, the artistic conception of mountains is not limited to large rocks, as even some small rocks can convey their charm. The small rocks with mountain shapes can become a rockery landscape work that has the artistic conception of a real mountain (Shen Citation2018).

4. Wang Shu’s gardening philosophy

Wang Shu’s architecture has a close relationship with traditional gardens. After completing his doctoral degree from Tongji University, he has been committed to research on the modernization of traditional gardens. Wang introduced the “gardening method” for the first time at the UIA (International Union of Architects) in 1999. As he explained, “The gardening method indicates a transition of consciousness. Gardens are not just gardens, but a kind of method for the architectural creation shifting toward the natural forms” (Wang Citation2009). The natural form mentioned here is Wang’s particular interpretation of the garden. In his vision, architecture is a part of imaginary of the living space of humans. This imaginary belongs together with natural things: mountains, rocks, plants, and so on, indicating that architecture can share this kind of natural form (Wang Citation2009). In other words, architecture does not have to follow strict geometry, it can resemble mountains and rocks that are not constrained by formal restrictions. Thus, Wang’s architectural design embodies a narrative of natural forms. Taihu stone is a representative case of the architecturalization of natural forms through Wang’s gardening philosophy. He believes that “the Taihu stone evokes the natural world of Jiangnan traditional garden” (Wang Citation2009), and thus, he uses Taihu stone to replicate the rockery landscape of the gardens. According to Wang, Taihu stone evokes “intensive mountain awareness”. He appreciates its form and spatial qualities and uses them in his design works by abstracting and transforming their form and shape. Thus, Taihu stone becomes an embodiment of his gardening philosophy by which natural things like mountains and waters are more important than architecture. Therefore, the Taihu stone has become one of Wang’s design motifs applied in two manners: architectural formal conceptualisation and surface interventions, both of which have been analysed in this article.

5. Formal conceptualisation of “Taihu-house”

The irregular surface of Taihu stone pitted with holes was for the first time abstracted by Wang Shu as an architectural mass in his project for the Tea House – one of the Five Scattered Houses(2003–06) in Yinzhou Park, Ningbo City. In this building, he inserted an irregularly shaped brick mass in an overall modern composition in a form of a three-story small-scale building with a six-meter-long, five-meter-wide floor plan. This particular segment of the building Wang named “Taihu-house” because of its geometry resembling the natural form of the stone () (Wang 2019). The “Taihu-house” in Ningbo Tea House is adjoined to an “S-shaped” mass made of glass and steel. Here, the side of the “Taihu-house” extends into the water, which reinforces the presence of the “mountain imagery” of this house. It also responds that the role of the water element is coordinated with the stone to create the “Shanshui idea” of the traditional garden landscape. On the surface of the “Taihu-house”, Wang Shu has designed several windows with diverse sizes and shapes, irregularly arranged, evoking the surface qualities of Taihu stone (Wang Citation2009). As distinct from the Taihu stone, the “Taihu-house” is a small building with a practical function. It is used as a management office and the design of windows satisfies the need for practical light and ventilation. The architect reused this idea in several of his later works usually not designing the “Taihu-house” as an independent mass but integrating it with other architectural forms as part of a larger architectural project. These projects reflect the shape and form of Taihu stone in various ways, encompassing the “Taihu-house” aesthetic.

Figure 6. Taihu-house is inspired by Taihu stone through the method of formal conceptualisation drawn by author.

5.1. “Taihu-house” as an independent mass

Wang reused the idea of an independent “Taihu-house” element in his project for Building No. 13 in the Xiangshan Campus of China Academy of Art (2002–07). This unique, irregularly shaped structure of “Taihu-house”, placed at the corner of Building No. 13, is visible along the pedestrian road on the campus. Its form is more notably disturbed than it is in the case of the Ningbo project’s “Taihu-house”. A part of the elevation is horizontally moved to form a zig-zag-shaped mass (). The retruded part of the elevation, used as an outdoor terrace, is intersected with a partially outdoor staircase, set up to provide an experience of change from indoor to outdoor and back to indoor. Nevertheless, the mass of the building keeps the strict cubic form with all surfaces being horizontal or vertical. The facade is made of concrete with a few irregularly arranged windows, insignificant in size comparing the mass itself. The material, the shape, and the surface of the building evoke the qualities of Taihu stone, yet the form of the building is rigidly geometric. Similar to the “special placed” Taihu stone in the garden, this “Taihu-house” stands out from its surroundings.

Figure 7. “Taihu-house” at the corner of building No. 13, Xiangshan Campus (2002–07), Hangzhou (photo by author).

Building No. 13 incorporates another “Taihu-house”, subtly concealed in the long and narrow courtyard. This “Taihu-house” is three-floor-tall and its form combines the solid and the void mass, just like the natural Taihu stone. Unlike previous “Taihu-houses”, this structure is not an impermeable concrete body with scarce windows – a part of it is a void that integrates a semi-outdoor staircase connecting with the main building vertically (, a). The surface of the solid is made with exposed concrete, imitating natural materials by emphasising the roughness of the surface. A small pond adjoining the “Taihu-house” is placed in the middle of the courtyard. However, except on rainy days, this pool is always dry. Rainwater flows into this pool during the rainy season through a slightly sloping floor slab above. The water and “Taihu-house” are illuminated by each other, forming a natural landscape painting. Corridors that surround the “Taihu-house” and the pond, allow the inhabitants of this space to enjoy the view reminiscent of a rockery landscape close by water in the traditional garden. A similar layout can be found in the courtyard of Building No. 15. The “Taihu-house” structure here is facing the main entrance of the courtyard. Its surface, composed of glass and wood, has a different appearance from the house placed in the courtyard of Building No. 13. As the main landscape theme of this space, a small enclosed garden planted with trees is placed between the “Taihu-house” and entrance, so that this structure is not directly visually open to visitors but it is looming behind the tree canopies (), b. This idea can be associated with the space composition method of “hiding and exposing” present in the traditional gardens, where the hidden elements of the landscape are revealed gradually along the path creating the impression of the depth in the courtyard. Both of these “Taihu-houses” are not put for a high level of functional necessity but are placed inside the courtyard to enrich the space.

Figure 8. a: “Taihu-house” in the courtyard of building No. 13, Xiangshan campus (2002–07), Hangzhou (photo by author); b: “Taihu-house” in the courtyard of Building No. 15, Xiangshan Campus (2002–07), Hangzhou (photo by author).

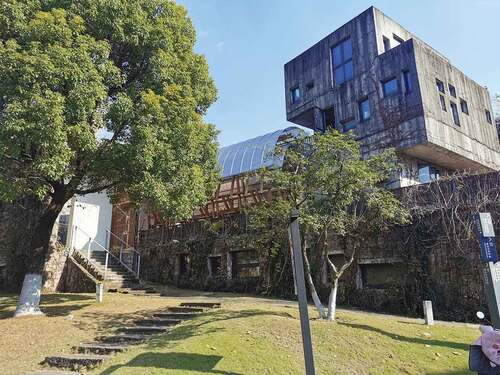

“Taihu-houses” mentioned above generally have a rather simple structure, usually made up of three cuboid masses where the middle one is translationally moved from the vertical axis. In this structure, all surfaces are horizontal or vertical. However, the “Taihu-house” in Building No. 19 is not restricted by the Cartesian frame but rather a free-form mass. As Wang explained, the form of these three “Taihu-houses” was shaped directly according to the Taihu stone’s form (Wang Citation2009). They are more organically modeled and closer to the shape of natural geometry. Building No. 19 is a composition made up of a large mass that resembles the shape of a mountain ridge with three “Taihu-houses” placed in front of it (). Viewed from the distance these three “Taihu-houses” appear negligible comparing with the large mountain-shaped mass. It can be inferred that the inspiration for this architectural composition comes from the lofty scenery of Chinese landscape paintings, with the main building representing a distant mountain, and the three “Taihu-houses” smaller pavilions near the observer. The water element is located between the large mountain mass and the “Taihu-house” structures, keeping the two objects geographically distant. However, the reflections of these objects in the water bring the two kinds of mountain-shaped elements together. Two bridges over the water connect the main mountain-shaped building with the smaller “Taihu-houses”. Visitors walk on the bridge and move between the big mountain and three small stone-shaped masses scenery that recall a sense of comfort in landscape. These three “Taihu-houses” give a similar first impression in terms of architectural form, but on closer inspection, the orientation, shape, and form of the windows vary. Each is designed to provide a different view of the scenery from their particular perspective (Wang Citation2009). Moreover, the windows face each other allowing viewers to explore the adjoined “Taihu-house” at close range, as well as the distant views of the cityscape and high-rise buildings beyond. The view from the Taihu-houses evokes the “where one can view” space experience that is frequently used in traditional Chinese landscape paintings. The observing subjects feel the same sense of comfort that they experience when observing the mountain scenery in traditional paintings.

Figure 9. Three different “Taihu-houses” forms are placed in front of Building No. 19, Xiangshan campus (2002–07), Hangzhou (photo by author).

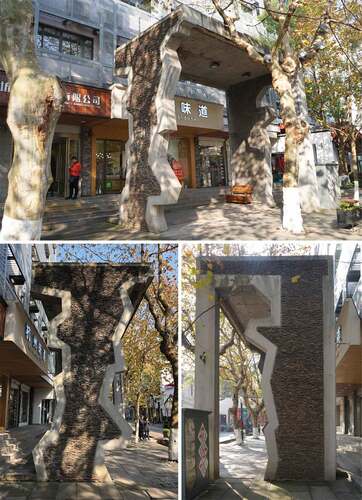

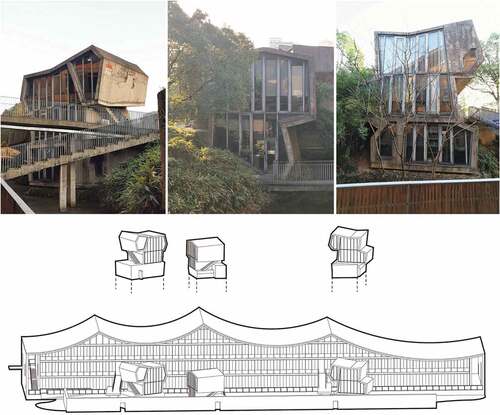

In his following projects, Wang Shu continued using the organically shaped “Taihu-houses”. Old Town Conservation of Zhongshan Street (2007–09) was his next project that encompasses several Taihu stone-inspired buildings. Zhongshan Street is a commercial street located on the north-south axis of Lin-an (临安) city, which was the capital of the Song Dynasty. Wang Shu designed a one-kilometer landscape of Zhongshan Street, from West Lake Avenue to the Drum Tower. In this project, the architect referenced the street’s historical background by using traditional materials and forms, and, thus, created a place that evokes people’s memory of old cities (Wang Citation2016). The unique architectural forms of “Taihu-house” buildings that conjure the shape of Taihu stones are used widely in this street. They have become landmarks that are put to a variety of uses, including offices, tea shops, and travel and tourist centers. In two of the “Taihu-houses” constructed on top of a historical brick wall, the architect used the modern material of concrete to achieve their unique form (). These small-scale buildings cleverly combine traditional elements with modern materials creating an interesting and dynamic juxtaposition. Their distinct modern forms composed of concrete walls and large glass windows with hanging staircases make a strong contrast to the brick wall retaining old doors and windows. The irregular mass of “Taihu-houses” with stone-shaped forms also contrasts with the regularly-shaped brick wall. Here, the traditional and the modern forms, as well as the new and the old materials blend into a harmonious whole. Moreover, the placement of the two Taihu-houses echoes the “symmetry placement” strategy of Taihu stone in traditional gardens. The combination of forms, styles, and materials exemplifies Wang Shu’s philosophy that modern cities should not seek to create an entirely new aesthetic by removing all references to their unique heritage.

Figure 10. Two “Taihu-houses” are placed closely at the major intersection, old town conservation of Zhongshan Street (2007–09), Hangzhou (photo by author).

Shili Hongzhuang Cultural Center (2012–17) in Ninghai city is Wang Shu’s recently completed project built to display the traditional marriage custom culture of the Chinese Jiangnan area. This large architectural complex includes five “Taihu-houses”, distributed across the complex and used for different functions. In these five projects, Wang reused the initial simple “Taihu-house” idea, rather than the more organic stone-resembling structure from later works. Their surfaces composed of red brick and windows varying in sizes are the most notable features of these five “Taihu-houses”. The red brick symbolises festivity, related to traditional Chinese marriage culture. Upon entering the complex, a large courtyard that contains a bridge and a pond surrounded by trees appears. One of the five “Taihu-houses”, formed by three cuboid masses of similar size, is adjacent to the water (). The three masses of the “Taihu-house” are stacked one over another creating a vertically asymmetrical composition. Its three-story-tall form creates a powerful contrast to the other mainly single-story buildings in the garden. Furthermore, the red brick material of this “Taihu-house” contrasts the grey brick of the surrounding buildings rendering it the most noticeable element of the complex. In traditional gardens, elements such as towers, terraces, and pavilions provide the best view of the surroundings. In this complex, the “Taihu-house” takes on this role. From the first floor, visitors get a close-up view of the pond with its flourishing plants while the third floor provides a wide vista across the entire architectural complex and the mountain scenery beyond. In general, the “Taihu-house” abstractly uses the shape of the Taihu stone in artistic form. It is built on top of a pond scenery to blend in with the water, creating a landscape of traditional “mountain-water” gardening. But in terms of the architectural function, it is used as a tea room and artist studio, and thus intimately connected to people’s daily activities that the people working in the building often forget its overall stone-shaped appearance. This perfectly encapsulates Wang Shu’s approach to design, combining modern architectural design with the structural forms of traditional Chinese gardens and at the same time not losing sight of the building’s practical needs.

5.2. “Taihu-house” integrating with other architectural forms

In the above projects, Wang used the “Taihu-house” as an independent stone-resembling mass or a kind of “addition” attached to the main building. However, the “Taihu-house” can be integrated with other architectural forms not as an “addition” but as an “insertion” element. For instance, this inserted structure occurs on the east elevation of Building No. 13 in the Xiangshan Campus. Compared to the first “Taihu-house” with an overall solid form, this structure has a lighter appearance. It consists of a thick concrete outline resembling the Taihu stone defining an inner void used as an outdoor deck (), a. In front of the building, the architect placed a bridge and a pond rendering the deck a good place to enjoy the outside scenery. In this imaginary, being inside the deck is equated with being inside a Taihu stone in the traditional garden. The elevation of Building No. 18 also features a “Taihu-house” mass is inserted into a regular cubic frame in a similar manner (), b. However, it is different from the “Taihu-house” in Building No. 13, as it is a solid structure. The surface of this “Taihu-house” is made of dark wood, masterly coordinated with the surroundings. The wood colour makes an extraordinary contrast to the dense green plants in the corner of the building. Well blended into the surroundings, this elevation has become a symbol of Building No. 18.

Figure 12. a: “Taihu-house” in the elevation of Building No. 13, Xiangshan Campus (2002–07), Hangzhou (photo by author) b: “Taihu-house” in the elevation of Building No. 18, Xiangshan Campus (2002–07), Hangzhou (photo by author).

The south façade of Building 18 also encompasses the idea of “Taihu-house”, however, in a completely new form. The long white façade incorporates a large number of irregular openings with several recesses shaped like a “Taihu-house” (). This idea of subtracting, where the Taihu-house becomes a void in the larger mass was for the first time applied in this project. The relationship of the “Taihu-house” with the subject changes here. In the previous projects, the subject is outside of the Taihu mass, an external observer. In this project, the subject is inside the Taihu mass looking toward the outside, fashioning the experience similar to the traditional gardens’ penetrable mountain landscapes. Moreover, the façade incorporates a path in a form of a ramp enhancing the walkability of the space. The “Taihu-house” recesses, as transitional spaces, connect the interior of the building with the external hanging promenade. This space forms outdoor decks where people can rest, relax and enjoy the view of Building No. 19 “mountain ridge”, and the city beyond. A similar concept of subtracted Taihu mass Wang applied in the design for the north entrance of Ningbo Museum (2003–07). The overall form of this building imitates the natural geometry of large mountains in landscape paintings such as Fuan Kuan’s Travelers Among Streams and Mountains (Wang Citation2009). Ningbo Museum is designed to resemble a fragment of a continuous mountain ridge that resembles a silhouette of a city (Wang Citation2009). In this building, the main entrance is designed as a simple, 30-meter-wide opening in the middle of the building’s mass. However, on the other side, a small “cave” resembling the “Taihu-house” form is used as an exit of the building (). Here Wang repeated the idea of subtracting the “Taihu-house” from the main building mass. The form of this building, its texture, and the cave-like openings embody Wang’s philosophy that the built environment should narrate about the natural forms and integrate into the natural surroundings.

5.3. Strategies of “Taihu-house” forms

According to the above, regarding Wang’s design process, the architect firstly formally conceptualises the natural Taihu stone in the shape of a more geometrically rigid “Taihu-house”, and then uses this element either as an independent mass or to create an intervention in the main building mass (). These strategies evoke the traditional gardens in a different manner and have a different relationship with the subject.

Figure 15. Taihu-house form is used in two manners. Type 1 is used as an independent mass; Type 2 is used to create an intervention in the larger mass (diagram by author).

From the projects above, there are several design strategies that Wang uses in his design to evoke the qualities of traditional gardens. These strategies assume reviving the visual qualities of the traditional gardens in the use of materials and forms, in particular the use of “Taihu-house” mass. The “Taihu-houses” designed by Wang Shu, generally have a three-floor-tall volume but they subtly vary in forms and materials and can be applied in several manners. In his initial attempts, he used the strategy of addition where “Taihu-house” is added to the mass of the building as an independent element. In this composition, the “Taihu-house” mass is taller than the other mass, and its prominent shape creates a contrast with the simplistic form of the other mass. It can be recognized as a point of decoration for the whole building. Seen from the outside, this mass stands out from the surroundings making an impression similar to a “specially placed” Taihu stone in a garden. “Taihu-house” itself had an evolution in Wang’s design, from strict, cubic, and impermeable forms made with concrete or brick (Ningbo Tea House, Buildings No. 13 and No. 15 in the Xiangshan Campus, Shili Hongzhuang cultural center) to those more irregularly shaped with large glass facades (Building No. 19 in the Xiangshan Campus, Old Town Conservation of Zhongshan Street).

Apart from creating “Taihu-house” as an independent mass, Wang used this element to enrich his design in other manners – adding it and subtracting it from the main building mass. In some projects, the Taihu-house mass is not simply added to the mass of the building but rather inserted into the façade expanding its spatiality. The insertion method, applied in the elevation of Building No. 13 and 18, Xiangshan Campus, still envisions “Taihu-house” as a solid mass, here less dominant, placed within a larger architectural frame.

An inversion of this idea appears in Building No. 18, Xiangshan Campus, and the north entrance form of Ningbo Museum, where Wang applied the subtraction method. In these projects, the “Taihu-house” mass is subtracted from a bigger cuboid mass. The resulting subtracted void is used mostly as a deck space – a threshold between interior and exterior. Perforating the massive walls of the building with these recesses of a particular shape, the architect created an impression of the natural porous rock. It is worth noting that these different strategies also evoke different relationships of the subject with the garden. When “Taihu-house” from impermeable solid becomes an inhabitable void it changes the relationships with the subject. It becomes a Duoshan setting, where one can enter inside the “rock” and enjoy the view toward the outside.

6. Surface interventions inspired by Taihu stone

6.1. Shaping windows and doors

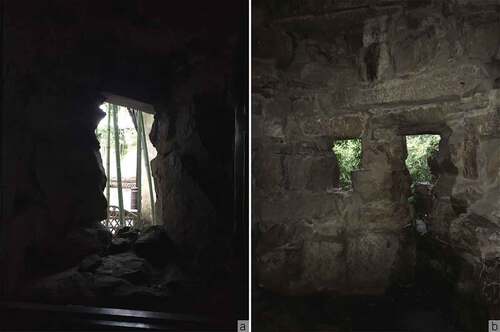

The preceding part of the article examines Wang Shu’s use of the Taihu stone in the formal conceptualization. However, Wang also employs the concept of Taihu stone in the surface interventions, in a new manner. The windows and doors with the form and shape of Taihu stone have become a signature of Wang’s design approach. In Building No. 13 and No. 15 in the Xiangshan Campus, the façade is decorated with a number of irregularly shaped window-like resembling a silhouette of a Taihu stone (). Their uniqueness leaves a deep impression on the visitors of the campus. The natural light passes through these openings, creating unique shades on the ground and walls of the courtyard behind the façade. When staying inside of the courtyard, these shades evoke the visitor’s imagination of traditional mountain landscapes. Wang’s inspiration for this spatial experience was derived from the traditional Chinese gardens. According to his book To Build a House, he had been visiting traditional gardens in Suzhou every year since 2000, and he singled out the Canglang Pavilion as his favourite garden from which he had derived a great deal of inspiration for his design approach (Wang Citation2016). KanShanLou (看山樓) and CuiLingLong (翠玲瓏) are two buildings located close by in the Canglang Pavilion garden, and there are rockery structures at the bottom of those two buildings. Both of these rockeries have doorways and windows bearing the characteristic Taihu stone shape (). Despite being artificially made the openings on the buildings’ bases made of rock have a natural appearance. The patterns of light and shade that are created in this way are something that visitors can enjoy. The desire to create such aesthetic experiences was very much to the fore of Wang Shu’s mind when he designed the architecture of buildings No. 13 and No. 15. The irregularly shaped voids on their facades provide a “picture frame” for the outdoor scene beyond the walls of the building, creating the impression of looking out at a traditional Chinese garden. From the inner courtyard of these buildings, it is possible to observe how the balance and contrast between light and shade change throughout the day.

6.2. A tour passes through windows and doors

The idea of walls perforated with Taihu stone-resembling openings, Wang Shu reused in his projects for Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion (2010) and Waterfront and Mountain Residence Hotel (2013–14). In both of these buildings, the architect used a similar design approach with many fragments of walls being placed along a designed movement line, within a cuboid framework.

Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion was firstly built in the northern part of the Urban Best Practice Zone in Shanghai Expo Park in 2010. Wang’s design of this building was inspired by a demolished Tengtou Village in the Jiangnan area of China. After Expo, Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion was removed but rebuilt in another place – the location near the original Tengtou Village. The exterior wall of Tengtou encompasses the traditional elements of Chinese Jiangnan vernacular dwellings, with more than five hundred thousand pieces of demolished tiles reused in this facade. The surface of thick concrete walls in the interior of the exhibition hall is emphasised with a special texture made by using bamboo cast in the production process. In this manner, Wang created a new architectural form by using elements of traditional building techniques. But the most striking intervention is hidden in the interior of the building. Visitors to the Pavilion are directed along a designated route – a curved and undulating ramp that coincides with the main flow of pedestrian traffic. Walking along this meandering ramp, visitors can pass through the whole building from the first to the second floor, and then again descend toward the exit. Along the ramp, the building is divided into eight segments by the walls that contain sizeable openings mimicking the shapes found in Taihu stones (). The architect intended to create an experience reminiscent of a walk in the mountains, and for this reason, the ramp rises and falls much like a mountain path. During the walk, visitors can pause and admire the views of the surrounding city framed by the uniquely shaped doors and windows. This spatial experience is the most outstanding aspect of the Tengtou Pavilion.

Figure 18. A tour pass through several walls with Taihu stone-shaped openings, Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion (2010) (diagram by author).

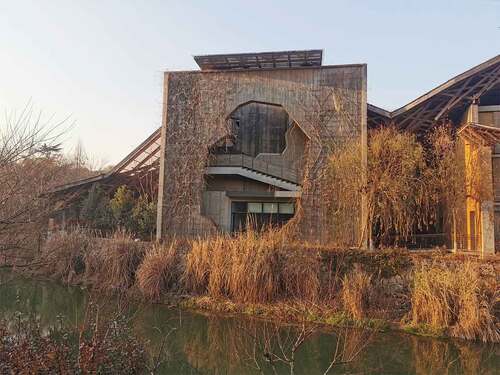

A similar spatial strategy Wang Shu used in the design for Waterfront and Mountain Residence Hotel (2013–14) that was recently built in the Xiangshan Campus. This long building is divided into four distinct sections from east to west, each having a specific function – a tea lounge, a conference space, a restaurant, and a hotel. The three-storey structure used for the hotel of this building has a similar form to Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion. The hotel has three levels. The first and second floors consist of a lobby and standard rooms, while the third floor encompasses an outdoor garden, a conference room, and a deluxe lounge area. An open staircase that connects the first floor with the third floor, located behind the main façade, has a very large Taihu stone-shaped opening toward the outside (). Alongside this staircase, there is a close-up view of the stream in the front of the building, the skyline of the city in the background, and the campus in between. The staircase leads to the roof garden. Similar to Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion, this garden is divided into smaller segments by six walls, each with a uniquely shaped doorway reminiscent of a Taihu stone (). The walls are strategically positioned to create a meandering pathway between various spaces providing visitors with a sequence of different spatial experiences.

6.3. Two types of walls

One of the pavilions in the landscape of Zhongshan Street also contains elements inspired by Taihu stone. This free-standing Pavilion is located in the middle of the pedestrian street with commercial shops and is used as a rest space for tourists. It is simply composed of three elements: two pieces of walls on each side and a ceiling on top (). The form of the walls is designed by abstracting the overall appearance of Taihu stone using two opposite strategies. One of the walls is designed with an irregular form resembling the shape of Taihu stone. In contrast, the other wall has an external regular form, but it has an opening in the form of a Taihu stone. In this figure-ground play, Wang Shu used the traditional Chinese thinking, of two opposite principles of nature – yin-yang. In this relatively small urban intervention, Wang created a striking landmark bringing traditional spirit into modern architecture.

6.4. Strategies of Taihu stone-shaped openings

As an inspiration for surface design, Taihu stone has been employed in Wang Shu’s architecture in several manners. Taihu stone-shaped openings that Wang uses in his buildings originate from the traditional artificial mountain landscapes. He reused this element in the façade design to recreate the spatial experience of garden pavilions. In addition, these openings connect the internal scenery with the outside space, awakening the experience of accessing the interior of the mountain landscapes in the gardens. Wang applied this type of design in the interior as well. However, the perforated walls here have a different function – fashioning the space experience through movement. This experience that he attempts to create is similar to the experience of walking inside the artificial mountain in a traditional garden. An inversion of this wall strategy appears in the design for the Zhongshan Street Pavilion, where one of the walls is the result of an intersection between an imagined Taihu stone and the sidewall, while the other is designed by subtracting the Taihu stone element from the wall. The juxtaposition of these two walls embodies the traditional Chinese philosophy of the two principles of nature – yin-yang. The former represents presence, while the latter represents the absence of the stone.

7. Conclusion

Since ancient times, Taihu stone has been renowned material used for creating artistic and architectural works. In particular, it is widely used in traditional gardens to build sculptural rockery and artificial mountain landscapes applying the methods of Duoshan and Zhishi. Wang Shu’s design approach has been influenced by these two traditional landscaping methods, in particular the idea of spatial sequence, surface design, and the “special placement” of the Taihu stone.

The Taihu stone has become Wang’s design theme in two manners: in architectural form conceptualisation and surface design (). This study has identified seven of Wang Shu’s works where he utilized the natural shape of Taihu stone as an inspiration. The form and the aesthetic of these buildings have become a signature of his designs. In the conceptualisation of architectural forms, he used the “Taihu-house” element implementing it in the buildings’ mass through strategies of addition, insertion, and subtraction. In particular, the “addition” principle of “Taihu-house” evokes the methods of “special placement” of Taihu stone in the gardens. Surface interventions such as perforating walls with Taihu stone-shaped openings appear on both, the exterior and interior walls, creating different kinds of experiences for the users. Especially, the space sequences created by walls with such openings seek to recreate the feeling of walking in the mountains.

Table 1. Comprehensive analysis of Taihu stone’s formal evolution form in Wang Shu’s architecture.

With the characteristic forms and shapes of Taihu stone, the architect manages to capture the essence and spirit of the traditional Chinese garden. By using the Taihu stone as an inspiration for the design strategies presented above, Wang Shu not only visually evokes the traditional gardens but also recreates a spatial experience of the garden. He does this by creating paths, caves, framed views, and sculptural structures combining visitors’ bodies into his “gardening experience”. Juxtaposing such traditional shapes with modern architecture Wang Shu successfully merges the old with the new, making a valuable contribution to architecture in modern China. Wang’s design approach that assumes the translation of traditional garden elements to modern buildings provides an exemplar of the successful practice of blending traditions into contemporary Chinese architecture.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mingyue Zhang

Mingyue Zhang is a Ph.D. Candidate at the Department of Architecture and Architectural Engineering, Seoul National University. She received Master of Science in Architecture and Architectural Engineering from Seoul National University. She is currently researching the continuity and transformation of tradition by articulating the characteristics of the traditional Chinese garden and their influence on the conception and design of contemporary architecture. [email protected]

Jin Baek

Jin Baek is a full professor at the Department of Architecture and Architectural Engineering, Seoul National University. He graduated from Seoul National University (B.S.), Yale University (M.A.), and the University of Pennsylvania (Ph.D.). Before joining the Department of Architecture and Architectural Engineering, Seoul National University, he taught and researched at various institutions including Pennsylvania State University and the University of Tokyo. He is the author of Nothingness: Tadao Ando’s Christian Sacred Space (Routledge, 2009), Architecture as the Ethics of Climate (Routledge, 2016), and Punggyeongryuheang (Hyohyung, 2013). [email protected]

References

- Bedingfeld, K. 1997. “Wang Shi Yuan: A Study of Space in a Chinese Garden.” The Journal of Architecture 2 (1): 11–41. doi:10.1080/136023697374531.

- Chau, H. 2015. “Xianfeng? Houfeng? Youfeng? - an Analysis of Selected Contemporary Chinese Architects, YungHo Chang, Liu Jiakun, and Wang Shu (1990s-2000s).” Frontiers of Architectural Research 4 (2): 146–158. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2015.03.005.

- Chau, H. 2018. “Wang Shu’s Design Practice and Ecological Phenomenology.” Architectural Research Quarterly 22 (4): 1–10. doi:10.1017/S1359135518000684.

- Ding, G. 2020. “The Return of Repressed Subjectivity in China: Feng Jizhong and Wang Shu.” Architecture and Culture 8 (3–4): 433–451. doi:10.1080/20507828.2020.1794130.

- Du, W. translated by Y. Y. Chen. 2009. Yunlin Stone Spectrum. Chongqing: Chongqing Publishing.

- Edward, D., and Y. Guang. 2012. “The Reluctant Architect: An Interview with Wang Shu of Amateur Architects Studio.” Architectural Design 82 (6): 122–129. doi:10.1002/ad.1506.

- Ji, C. translated by A. Hardie. 1988. Craft of Gardens (Ji Cheng, Ming Dynasty). New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Jin, X. 2021. “Text-Structure-Typology, from Language Metaphor to “Fictionalising” Culture: A Critique of WANG Shu’s Architectural Thesis.” Design, and Pedagogy, Architect 1: 26–33.

- Liu, C. 2015. Yuanye (Original Author Ji Cheng, Ming Dynasty). Nan Jing: Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing .

- Peng, Y. 1988. Analysis of Chinese Classical Gardens. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Perlez, J. 2012. “An Architect’s Vision: Bare Elegance in China”. The New York Time, August 9. Accessed 20 December 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/12/arts/design/wang-shu-of-china-advocates-sustainable-architecture.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20120812

- Ping, H., and T. Ozawa. 2021. “Composition of water-featured Open Spaces on Chinese University Campuses.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 20 (6): 615–626. doi:10.1080/13467581.2020.1803077.

- Shen, M. 2018. “Archetypal Refinement of the Classical Gardens in the South of the Yangtze River and Design Transformation in Contemporary Architecture: Taking Taihu stone as an Example.” unpublished master’s thesis, Nanjing: Southeast University.

- Thorsten, B. 2009. “WANG Shu and the Possibilities of Architectural Regionalism in China.” Nordic Journal of Architectural Research 21 (1): 04–17.

- Wang, S. 2009. “The Narration and Geometry of Natural Appearance, Notes on the Design of Ningbo Historical Museum.” Time+Architecture 3: 66–79.

- Wang, S. 2016. To Build a House. Chang Sha: Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Wang, J. 2018. “The Everyday: A Degree Zero Agenda for Contemporary Chinese Architecture.” Architectural Research Quarterly 21 (3): 234–246. doi:10.1017/S1359135517000276.

- Wei, F. 2009. “A Study on Theories and Methods of Placing Stones and Piling Hills in Chinese Landscape.” unpublished doctor’s thesis, Beijing: Beijing Forestry University.

- Wu, Z., Y. Chen, and D. Wu. 2012. Illustrative Interpretation of Yuan Ye (Ji Cheng) – The Inheritance of Traditional Culture. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Yu, C., Z. Zhang, and S. Wang. 2017. “Recurrence and Superposition: The Study of the Native Architecture Elements of Wang Shu’s Architecture.” Architect 3: 67–76.

- Zhou, W. 2005. “A Comparative Study on Chinese and Western Classical Garden Arts.” Canadian Social Science 1 (3): 83–90.

- Zhu, J., C. Sun, and L. Zhang. 2021. “WANG Shu and LI Chengde: Comparing the Two Campuses of CAA Hangzhou with an Assessment of the Critical Regionalism Discourse.” Architect 1: 4–16.