ABSTRACT

This article is the first thorough account of the dragon-wrapped column in a Western language. In contrast to previous scholarship, this study finds that the initial prototype of the dragon-wrapped column dates to the Han dynasty rather than the Song dynasty. This study delves into the imagery of dragon-wrapped columns and other dragon-related serpentine columns in Han literature and in artifacts discovered in Han tombs. It also addresses the thinking process of “wrapping the column,” referencing earlier instances of wrapped columns that served as the technological and conceptual ground for creating the dragon-wrapped column at the time. Furthermore, this article demonstrates that the use of a helical design on the bodies of columns is not exclusive to ancient Chinese art but is also present in ancient Greco-Roman art of the eastern Mediterranean region, where it may have originated from the Mesopotamian serpent-wrapped column. Meanwhile, the numerous foreign images and Western Asian–style objects uncovered in Han tomb excavations in southern Shandong and northern Jiangsu provinces and all along the coast indicate that these regions had close maritime trade and cultural exchange channels with the West.

1. Introduction

The image of the dragon occupies a special place in traditional Chinese visual art, as it is considered to be both a legendary creature that communicates with heaven and earth and a supernatural power that is mysterious and unpredictable. Through the course of ancient Chinese history, the dragon grew into a symbol of divine and imperial power, appearing in temples, shrines, and particularly in scenarios depicting the emperor and the imperial family. As a result, the ancient construction of an upper-class built environment was always adorned abundantly with depictions of dragons. The dragon-wrapped column is one of the most distinctive and impressive forms of architectural column decoration, and it can be found in some magnificent palaces and temples. Its distinctive visual effect and intense symbolic meaning draw the viewer’s attention, making it one of the architectural environment’s visual focal points.

The most well-known wrapped-column case is undoubtedly the pair of white marble huabiao 華表 (ornamental pillar) in front of Tian An Men 天安門 (Gate of the Heavenly Peace, built during the Yongle永樂 years of the Ming dynasty) (1368–1644) (). Most of the surviving ancient wooden dragon-wrapped columns are mainly from the Ming and Qing dynasties. Distinctive examples are a pair of frontal dragon-wrapped columns in the Dazhen dian 大政殿 of the Imperial Palace in Shenyang, built in 1625 (), and, within the same palace compound, a pair of openwork, carved golden dragon-wrapped columns in front of the throne of Chongzheng Hall 崇政殿 (designed and produced in 1747) (). Other examples are in the 1729 reconstruction of the Dacheng 大成 Hall of the Confucius Temple in Qufu 曲阜, Shandong Province. The main building and its annexes are adorned with several dragon-wrapped stone pillars, a symbol of reverence for Confucius ().

Figure 1. Huabiao (ornamental pillar) in front of Tian An Men (Gate of the Heavenly Peace, built during the Yongle years of the Ming dynasty). Beijing. Height: 957 cm, diameter: 98 cm.

Figure 2. A pair of frontal dragon-wrapped columns in the Dazhen dian of the Imperial Palace in Shenyang, built in 1625.

Figure 3. A pair of openwork, carved golden dragon-wrapped columns in front of the throne in Chongzheng Hall in the Imperial Palace in Shenyang. Designed and produced in 1747.

Figure 4. Top: Stone-carved dragon-wrapped pillar on the front of the Dacheng Hall, Confucius Temple, Qufu. Lower left: Dragon-wrapped pillar in Dacheng Hall annex building (courtyard gate). Lower right: Incense Burner in the courtyard of Dacheng Hall in the form of a stone dragon-wrapped column. Photographs by the authors of this article.

Occurrences of dragon-wrapped columns and accompanying documents have also been discovered from earlier dynasties, including the Song (960–1279), Liao (916–1125), and Jin (1115–1234). Moreover, there is documentation of dragon-wrapped columns from other dated stone carvings. In other words, the dragon-wrapped column is not an occasional creation of individual craftsmen in a particular period or region but a tradition that has a history stretching back more than one thousand years.

For a long time, most of the research on dragon-wrapped columns in architectural history and art history began with the periods of the Song, Liao, and Jin dynasties and considered these columns as a distinctive category of carved embellishment in architecture. For example, encyclopedic architectural books such as Li Jianping’s 李劍平 Zhongguo gujianzhu mingci tujie cidian 中國古建築名詞圖解辭典 (Illustrated Dictionary of Chinese Ancient Architecture Terms) (Li Citation2011, 362) and Lei Dongxia 雷冬霞’s Zhongguo gudian jianzhu tushi 中國古典建築圖釋 (Illustration of Chinese Classical Architecture) (Lei Citation2015, 14), provide an introduction to the form, construction process, and application of surviving dragon-wrapped columns from the Song, Liao, and Jin dynasties to the Ming and Qing dynasties. Fu Xinian 傅熹年, a renowned historian of Chinese architecture, mentions an older instance of a dragon-wrapped stone column in the Northern Qi dynasty’s Xiangtang Mountain 响堂山 Grottoes in Handan 邯鄲, Hebei 河北 (Fu Citation2009, 242). None of the above studies, however, discusses the origin and cultural importance of the dragon-wrapped columns.

The literature on Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE) Chinese architecture is relatively scarce compared to the wealth of articles and monographs on Han tombs (especially the pictorial stone tombs). The preliminary investigation and study of the architecture of the Han dynasty did not begin until the early twentieth century, represented by works such as Édouard Chavannes’s Mission Archéologique dans la Chine Septentrionale (Chavannes Citation1909), Marc Aurel Stein’s Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal Narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China (Stein Citation1912), and Liang Sicheng’s article “A Han Terra-Cotta Model of a Three Story House” (1927–28) (Liang Citation2001, 1–7). In recent years there has been some writing about Han Dynasty tombs and other contemporaneous building remains in both the Chinese and English languages, such as Jing Xie’s “Pillars of Heaven: The Symbolic Function of Column and Bracket Sets in the Han Dynasty” (Xie Citation2020), Yang Aiguo’s 楊愛國 article “Cong shiguo dao shishi” 從石槨到石室 (From Stone Outer Coffin to Stone Burial Chamber) (Yang Citation2013), Zhang Zhuoyuan’s 張卓遠 monograph Handai huaxiang zhuanshi muzang de jianzhuxue yanjiu 漢代畫像磚石墓葬的建築學研究 (An Architectural Study of Han Dynasty Pictorial Stone Tombs) (Zhang Citation2011),Guo Qinghua’s The Mingqi Pottery Buildings of Han Dynasty China, 206 BC – AD 220: Architectural Representations and Represented Architecture (Guo Citation2010) and Huang Xiaofen’s 黃曉芬’s monograph Hanmu de kaoguxue yanjiu 漢墓的考古學研究 (Archaeological Study of Han Tombs) (Huang Citation2003). However, none of the studies above treats the dragon-wrapped column comprehensively. As a decorative element in architecture, the dragon-wrapped column has received insufficient attention from art and architectural historians. While it has been briefly mentioned in numerous works on the general history of architecture and architectural terminology, it has not yet been written about in detail in a monograph or a dedicated article.

Architectural columns in a spirally wrapped style from other cultures have been similarly overlooked by scholars. For example, spiral columns from the late Hellenistic to Roman periods in the eastern Mediterranean, which are potentially related to the dragon-wrapped columns, were likewise neglected for a lengthy period of time until the mid-twentieth century. However, as related archaeological excavations progressed, this subject gained the attention of researchers, as evidenced by J. L. Benson’s “Spirally Fluted Columns in Greece” (Benson Citation1959) and “Spirally Fluted Columns in Cyprus” (Benson Citation1956); G. B. Waywell, J. J. Wilkes, and S. E. C. Walker’s “The Ancient Theatre at Sparta” (Waywell, Wilkes, and Walker Citation1998); Paul Stephenson’s The Serpent Column: a Cultural Biography (Stephenson Citation2016); Esen Ogus’s Columnar Sarcophagi from Aphrodisias (Ogus Citation2018) and Georgina J. Henderson’s “Turn, Turn, Turn: The Construction of the Architectural Spiral Fluted Column in the Ancient Mediterranean World” (Henderson Citation2018) which is a relatively comprehensive analysis based on previous studies.

In a similar vein, recent findings from Han archaeological excavations, particularly the discovery of a number of early dragon-wrapped columns and their depiction in pictorial stone tombs as well as the discovery of spiral pillars associated with them, have established a basis for the analysis and academic significance of this subject in China. The time is ripe for an article like ours, dedicated to the comprehensive study of the dragon-wrapped column.

This article introduces and explores thoroughly the dragon-wrapped column for the first time in a Western language, and situates it within the context of Han dynasty, rather than Song dynasty, architecture in China. We argue that the dragon-wrapped column, which appears to be a typical indigenous Chinese architectural element, arose from the fusion of local and foreign cultures during the Han dynasty, allowing us to gain a better understanding of the complexities of early East-West architectural and cultural exchange via the Maritime Silk Road. Our theory is based on a combination of old and new archaeological findings of dragon-wrapped columns from Han dynasty tombs.

2. Dragon-wrapped columns in the song dynasty

The earliest credible documentary record of the dragon-wrapped column can be found in the Yingzao fashi (written in 1100 CE and officially published in 1103 CE), where information about the dragon-wrapped column is mentioned twice: once in volume 3, “Stonemasonry Specification,” in regard to a wangzhu 望柱 (baluster), with an illustration in volume 29 about the normative prototype of a high-relief, winding, dragon-wrapped column (); and again in volume 20, “Sculpture,” regarding dragon decoration on timber columns (Li Citation2006, 82).

Figure 5. A wangzhu (baluster), with an illustration of the normative prototype of a high-relief, winding, dragon-wrapped column in the Yingzao fashi (written in 1100 AD and officially published in 1103 AD), vol. 29 (Li Citation2006).

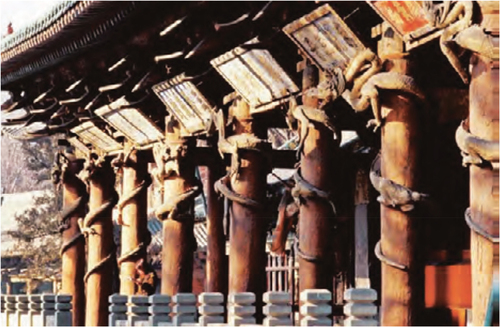

Therefore, according to the Yingzao fashi, the dragon-wrapped columns in the Song dynasty could be made of both stone and wood. A representative example comes from the Jinci shengmu dian 晉祠聖母殿 (Hall of Saintly Mother of Jinci Memorial Temple) in Taiyuan 太原 (built in 1023–32 CE and rebuilt in 1102 CE). The eight frontal timber columns supporting the eaves () were all carved around 1087 CE with wrapped dragons, which are very close to the prototype of the illustration hunzuo chanzhu long 混作纏柱龍 (column with openwork wrapped dragon decoration) in the Yingzao fashi ().

Figure 6. Eight dragon-wrapped frontal timber columns supporting the eaves of the Jinci shengmu dian (Hall of Saintly Mother of Jinci Memorial Temple) in Taiyuan, built in 1023–32 AD.

Figure 7. Hunzuo panlongzhu (column with openwork wrapped-dragon decoration) in the Yingzao fashi (written in 1100 AD and officially published in 1103 AD), vol. 32.

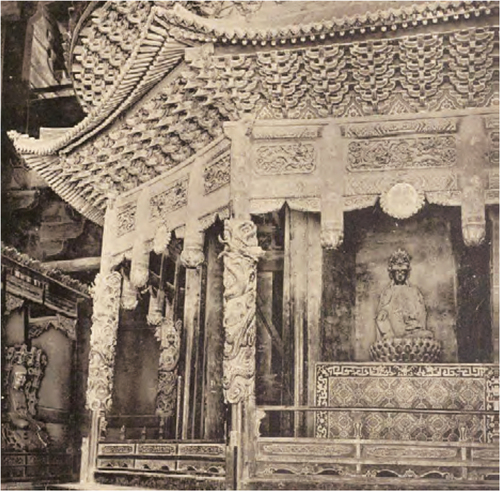

In addition, there was also a relief-carved, dragon-wrapped column from the Northern Song Dynasty that supported the eaves of the Longxing Temple 隆興寺, Zhengding 正定 (), but unfortunately the temple’s relief decorations were all destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). The images used in this article were taken by Japanese scholars 常盤大定 Tokiwa Daijo (1870–1945) and Sekino Tadashi関野貞 (1868–1935) when they visited the temple in Hebei in the early twentieth century, before its destruction.

Figure 8. Relief-carved, wrapped-dragon column for supporting the eaves of Longxing Temple, Zhengding. Northern Song dynasty (Tokiwa Citation1914, 90).

It can be inferred from the aforementioned records and shreds of physical evidence that the dragon-wrapped column was fully developed at least throughout the Northern Song Dynasty and was already being used as a common ornament for prestigious temples at the time of the Yingzao fashi’s writing.

Two examples of dragon-wrapped columns in pre-Song architecture, described by Fu Xinian, can be found at both sides of the doorway of Cave 1 in the South Xiangtang Mountain of the Northern Qi dynasty. The cave is dated to the second half of the sixth century (), thus advancing the use of the dragon-wrapped column by about five hundred years. However, we found an even older example in the Goguryeo 高句麗 Ssang-Yeongchong 雙楹塚 (twin-column tomb) in Korea, built in the second half of the fifth century; it has two octagonal stone columns embellished with painted images of wrapped dragons in the hallway between the front and back rooms (). This not only extends the dragon-wrapped column’s history by nearly a hundred years but also broadens its geographical dispersion from central China to the remote Liaodong 遼東 area and the Korean Peninsula.

Figure 9. Dragons wrapping the column at both sides of the doorway of Cave 1 in the South Xiangtang Mountain of the Northern Qi dynasty in Handan, Hebei.

Figure 10. Two octagonal stone columns painted with images of wrapped dragons in the passageway between the front and back rooms of the Goguryeo Ssang-Yeongchong (twin-column tomb). Discovered in 1913 in Nampo, South Pyongan Province, Korea. Built in the second half of the fifth century. Left: Perspective line drawing of the tomb room. Right: photograph of the tomb room.

Nonetheless, the Goguryeo example is not the earliest dragon-wrapped column discovered in the course of our research. With the discovery of Han dynasty tombs in recent decades of archaeological excavation, we are able to provide new information about the origin of the dragon-wrapped column, especially in regard to the materials used in the construction of the column, which came from the provinces of Lunan魯南 (south of Shandong Province), Subei 蘇北, Zhengjiang 浙江 and Sichuan 四川in the middle and late periods of the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220).

3. The image of dragon-wrapped columns in the han dynasty

Han Pictorial stone carvings that were discovered in tombs dating from the mid-Western Han dynasty through the Eastern Han dynasty provide a wealth of visual information. Stone-carved images related to architecture are an important means of understanding and analyzing the Han dynasty’s building-construction activities in ancient Chinese architectural historiography.Footnote1 A pair of columns decorated with a curled dragon were carved out in line relief in a late Eastern Han dynasty pictorial stone tomb unearthed in 1973 in Haining 海寧, Zhejiang Province ().

Figure 11. Dragon-wrapped columns in the late Eastern Han dynasty pictorial stone tomb, excavated in 1973 in Haining County. Image source: Left: (Zhang Citation2002, 72); Right: (Pan Citation1983, 13–14).

This discovery could be the first pictorial evidence that the dragon-wrapped column existed during the Han dynasty. We have been unable to find any above-ground material evidence for these columns from the same period, owing mainly to the fact that the Han dates to thousands of years ago and that most of the columns were made of wood. Thus, the images from this tomb provide valuable evidence. The image presented in could be a genuine representation of an actual decorative dragon-wrapped column in a real Han dynasty architectural context.

Despite the fact that the thickness of the column in the image suggests that it is insufficient for use as a load-bearing component of the building, it is crucial to remember that the objects depicted in the tomb’s stone carvings are usually scaled-down and metaphorical in nature. Based on the dragon columns’ locations on both sides of the tomb’s doorway, it is clear that they undoubtedly functioned as doorposts.

Both the practice of carving architectural imagery onto two-dimensional pictorial stones and the practice of mimicking the construction and decoration of real-world timber buildings using three-dimensional pieces of stone were increasingly prevalent in the vaults of tombs in the middle and late Eastern Han dynasty. One of the most representative of these components was the wood-like stone column, usually adorned with a shallow relief or a line-carved motif, which was commonly manifested in the tomb as a center column located under a beam. Multiple examples of such columns carved with dense figures or animal reliefs have been discovered in Shandong, primarily in the central region. Despite the fact that some of them are currently preserved in museums outside of the context of their original finds, archaeological reports state that they are weight-bearing center columns. Examples include the column of the tomb of Dawenkou大汶口in Tai’an泰安, excavated in 1960 (, left)(Cheng Citation1989); the column carved in relief under the center partition beam of the back chamber of tomb of Dongjiazhuang 董家莊 in Anqiu 安丘 County (, middle) (Anqiuxian wenhuaju Citation1992, 21); and the column inside the Han tomb of Baiyangdian 白楊店 in Jiyang 濟陽 County, excavated in 2014 (, right)(Xing, Fang, and Guo Citation2015).

Figure 12. Left: the column of the tomb of Dawenkou excavated in 1960. Middle, the column carved in relief under the middle partition beam of the back chamber of the tomb of Dongjiazhuang in Anqiu County. Right: the column inside the Han tomb of Baiyangdian in Jiyang County. Photographs by the authors of this article.

The stone column in the Han tomb in Banjing班井Village features a dragon carved in shallow relief, making it one of the earliest instances of a dragon column discovered thus far (, left)(Liang and Meng Citation1997). A stone wall column with two dragons standing opposite one another in relief has been preserved in the Xuzhou Han Pictorial Stone Art Museum, showing a different style from cylindrical wrapped column yet comparable to that of the dragon-wrapped column (, middle). Finally, a stone center column found initially under the beam in the front room of the Eastern Han portrait stone tomb in Wu Baizhuang 吳白莊, Linyi 臨沂, portrays dynamic flying dragons, winged tigers, rabbits, and birds (storks or cranes) (, right). With its openwork, high-relief carving, this column has an aesthetic impact similar to that of the dragon column, but features a broader selection of animal designs.

Figure 13. Left: Stone column in the No. 1 Eastern Han tomb in Banjing Village, Tongshan County, Xuzhou, excavated in 1992. Middle: A stone wall column with two dragons standing opposite one other in relief, Xuzhou Han Pictorial Stone Art Museum. Right: A stone center column in the front room of the Eastern Han portrait stone tomb in Wu Baizhuang, Linyi. Photographs by the authors of this article.

Taking the above examples into consideration, it can be concluded that the fundamental practice of carving dragon-wrapped columns in relief emerged in the brick and stone chamber tombs found in many locations throughout northern Jiangsu and Shandong during the Eastern Han dynasty (mid-to-late period). However, the columns’ ornamental motifs and themes, and the process of their modeling, are inconsistent, suggesting that the dragon-wrapped columns from the Eastern Han were still in an early stage of their development.

This suggestion has two ramifications. One is that the dragon-wrapped columns located above ground during the Han period (of which there are no tangible remains) were modeled after ornate stone columns discovered in an Eastern Han tomb. However, taking into account the inherent relationship between the “yin house” of ancient Chinese tombs and the “yang house” of the living, most underground tombs imitate the form of above-ground building components rather than vice versa. Thus, a more plausible implication is that the dragon-decorated columns of the Eastern Han dynasty’s underground tombs are copies and reproductions of similar columns seen in wooden, above-ground residential structures of the time. In other words, the actual prototype of a column with decoration akin to the dragon-wrapped column we see today was already in use during the Han dynasty. There are, however, few, if any, physical remains of Han dynasty timber architecture. This means that we must observe and evaluate a greater number of cases in order to determine the true origin of the decorative shape of the dragon-wrapped column, both in terms of its aesthetic concept and its technique.

4. Wrapped-style stone columns inside an eastern han dynasty tomb

Although there are numerous forms of dragon-wrapped columns in traditional architecture, all of them are based on the practice of wrapping and winding ornamentation around the column body. As a result, uncovering the remains of such decorative technique is another possible avenue for tracing the origins of the dragon-wrapped column’s design.

Aside from the stone columns ornamented with carved dragons found in Shandong and northern Jiangsu Provinces, other similar burials in the region have excavated columns wrapped in peculiar configurations. For example, during the 1974 excavation of the Eastern Han dynasty pictorial stone tomb of Jiu Nüdun 九女墩 in Dongzhifang 東紙坊 Village, Lanling 蘭陵 County, archaeologists discovered a stone column with a relief carving on the body that imitates a braided fabric belt decorated with a mythical Chinese hybrid creature known as a bixie 辟邪 (literally meaning “to ward off evil spirits”) plinth (). Our close examination of the column, which is illustrated in a detailed photograph in , reveals exotic foreigners carved on the lower side of the column, each of whom is wearing a pointed hat, has a higher nose bridge, deeper eye socket, and is kneeling on one leg. In Chinese literature, these foreigners are commonly referred to as the huren 胡人 (Hu people), who traveled both the overland and Maritime Silk Roads. The question of what ethnic group the Han dynasty Hu people belonged to is currently a major topic of academic dispute. The word “hu” itself means “chaos” and “uncertainty.” Theoretically, the Xiongnu, the Kushans (or the Greater Yuezhi), the Bactrians, the Persians, and the Scythians are all plausible contenders for the title of “hu.” However, regardless of which ethnic group the foreigners depicted on the column belonged to, the trademark features we observe in the carvings, like high noses, deep-set eyes, pointed hats, and narrow-sleeved attire, would have been understood by those living during the Han dynasty as foreign and exotic characteristics.

Figure 14. Stone column with detail. The Eastern Han dynasty Pictorial Stone Tomb of Jiu Nüdun in Dongzhifang Village, Lanling County. Photographs by the authors of this article.

The column’s relief appears to mimic the texture of bamboo, bamboo skin, hemp, or leather, as well as the durability and flexibility of those materials. Closer inspection of each stone strip of “fabric” reveals line drawings of dragon scales. Dragons’ heads with open mouths are carved into the end of the column’s upper section. Unfortunately, part of this area has been defaced, so it is impossible to establish the exact number of those heads. In general, the relief covering the column is most likely imitating a woven layer of fibrous materials (such as bamboo) carved in the shape of dragons to protect and decorate the column.

A stone column excavated in the northern portion of Jiawang 賈汪 District, Xuzhou (currently conserved in the Xuzhou Museum) (), contains other details directly connected to the later dragon-wrapped column. The column’s carved surface mimics the effect of a braided covering. Relief carving can be seen between the prominent interwoven and overlapping braided bands, although the specific images cannot be identified. The braided bands are carved in a dragon-scale pattern, leading some scholars to conclude, after a thorough examination, that this is a column with nine dragons coiled around each other (Yang Citation2009).

Figure 15. Dragon-wrapped column excavated from the northern portion of Jiawang District, Xuzhou. Photographs by the authors of this article.

This column is similar to the relief-carved braided stone column recovered from Jiu Nüdun and illustrated in . Such stone columns were most likely modeled after other materials, such as bamboo, which were probably utilized to wrap the columns during their actual construction above ground. Furthermore, the braided bands are frequently carved with images of scales resembling those on the bodies of dragons and serpents making them a possible source for the later dragon-wrapped columns.

Although no direct descriptions of the details of column decoration have been found in Han dynasty texts outside of the underground-tomb setting, the incorporation of imagery related to dragons and snakes into actual examples of above-ground architecture would not have been uncommon at the time, especially in the construction of upper-class palaces. Despite the fact that there are no above-ground remains of palaces that existed more than two thousand years ago, literary evidence supports our hypothesis. Wang Yanshou 王延壽’s book Lu Lingguang dian fu 魯靈光殿賦 (Rhapsody on the hall of numinous brilliance in Lu), for example, notes that when constructing the roof frame of the Lingguang dian 靈光殿 (Palace of numinous brilliance), “the dragon and cloud are carved in an openwork design into the rafter and column, with the dragon meandering across the area, its head up and running, and its mouth hovering and twisting. The vermilion bird flaps its wings and spins to balance itself during this period, while the flying serpent coils and twists itself around the rafters.”Footnote2

He Yan 何晏 (195–249; a Chinese philosopher and politician of the state of Cao Wei in the Three Kingdoms period in China), in his book Jingfudian fu景福殿賦 (Rhapsody on the Jingfu Hall), described the building’s railings as follows: “In contrast to the horizontal wood of the railing, which has the appearance of a flying serpent, the connecting pieces of the railing have the appearance of beautiful jade. The former is analogous to a chi 螭 dragon that has been coiled up, while the latter is analogous to a qiu虯dragon that has halted and rested.”Footnote3

Long 龙 (dragon), qiu 虬 (coiling dragon), chi 螭 (hornless dragon), and teng she 騰蛇 (flying snake) are all words for dragon-related creatures, which in modern Chinese are commonly referred to simply as “dragons.” In addition, the verbs wan shan 蜿蟺 (wind), kui ni 躨跜 (coiling and writhing), rao 绕 (go around), and pan 蟠 (coil) all refer to coiling. As a result, it would be logical to infer that the practice of wrapping columns in coiled images of dragons and serpents occurred in Han dynasty architecture, and served as the primary template for the later dragon-wrapped column.

Aside from dragons wrapped around a column in a more ordered form as individuals or in braided bands, there are instances when the bodies of numerous dragons are twisted and wrapped around one another. For example, in a column (, left) unearthed in 1979 approximately three meters in front of the late Eastern Han dynasty portrait stone tomb in Wayao 瓦窯 Village, Xinyi 新沂 county, Xuzhou徐州,Footnote4 six dragons are sculpted in relief, their heads and tails entwined (Wang and Xia Citation1985). In the Xuzhou Museum’s storage room, a shorter Han dynasty stone column (, right) is similarly encircled by several serpentine creatures. There are three different representations of the heads and faces of these creatures in the center of the column. These serpentines are most likely dragon- and snake-themed decorative images.

Figure 16. Left: stone column unearthed approximately three meters in front of the late Eastern Han dynasty portrait stone tomb in Wayao village, Xinyi county, Xuzhou, in 1979. Right: Han dynasty relic stone column preserved in the Xuzhou Museum’s storage room. Photographs by the authors of this article.

The dragons and snakes carved in relief on top of the columns in these two cases are not as neat in their coiling as those carved in relief on the stone columns in the aforementioned tombs of Lanling county and Jiawang county. However, they certainly add to the plausibility of the speculation, above, regarding the possible use of coiled dragons and snakes as decoration on the columns in Han dynasty architecture.

Of the columns discussed so far, the dragon-wrapped column carved in the pictorial stone tomb in Haining () and the column from the tomb in Banjing (, left) are the closest in shape to the dragon-wrapped architectural columns of later periods, a typical example of which must contain an image of a dragon represented in a clearly articulated and regularized spiraling, coiling, or winding form on the column body. The other cases discussed above either do not possess these traits, or their aesthetic effect of orderly, spiralized winding is negligible, indicating that they are not examples of the later, mature model of the dragon-wrapped column, which had not yet been fully established.

A stone column with the sacred male mythical creature tianlu 天祿 was discovered in Jiunüdun (), in conjunction with the bixie plinth column shown in . The top of the column is fractured and the body of the column is sculpted in relief, picturing a spirally coiled balustrade, trees, winged animals, and a feathered figure holding an elixir, which could indicate ascension to immortality. Although different in scale, this column’s narrative and spiraling composition are conceptually comparable to Trajan’s Column, which was completed in Rome in 113 AD ().

Figure 17. Stone column in the shape of a beast discovered in the Han portrait stone tomb of Jiunüdun Hill at the East Zhifang village of Lanling county. Photographs by the authors of this article.

So far in our discussion of the origins of dragon-wrapped columns we have focused on columns with a “wrapping” aspect. Let us not forget another important design element of the dragon-wrapped column, notably its helical (spiral) form, in which the dragons usually curl around the column from bottom to top, with their heads raised at the top. A rare, Han dynasty, spiral-line stone column (, left) owned by a private collector in Jining 濟寧 (Shandong) could be relevant to our discussion of the dragon-wrapped column, as could a comparable item found in the storage room of the Tengzhou 滕州 Museum in Shandong Province (, middle). On our recent visit to a site near Tengzhou, the Shanting山亭 Cultural Center’s storage yard, we discovered yet another column with finer-grained spiral flutes (, right). The exact date and excavation information for these three columns is unknown, and few researchers have been able to study them for many years. Fortunately, the stone chamber tomb from the Middle and Late Eastern Han dynasties uncovered in March 2017 in the Qian maogu 前毛堌 Village, Yangzhuang羊莊Town, Tengzhou County (), has expanded our knowledge and understanding of this sort of column as well as aided us in contextualizing it. Qian maogu lies sixty-four kilometers northwest of Jiu Nüdun. We were privileged to be able to visit the tomb and take the photograph shown in . The middle column, which holds the capital column and is located beneath the tomb’s middle chamber (arched), is divided into two upper and lower halves. The upper section has a very distinct and regular spiral-fluted texture, while the lower section has straight prismatic edges with a triangular cross section. Although stone columns with shallow grooves and prismatic edges have been discovered in a variety of locations throughout China during the Eastern Han dynasty, such as the examples shown in the , the stone columns with helical flutes found in the southern Shandong region are unique in Han dynasty archaeology. These columns exhibit exotic styles of architectural decoration, lending credence to the hypothesis that such styles are most likely Western in origin.

Figure 19. Left: Han dynasty spiral-line stone column from a private collector shown in Jining, Shandong. Middle: a stone column with spiral grooves on the body and a capital supporting it. Collected in Tengzhou Museum’s storage room. Exact age and excavation information unknown. Right: a stone column with finer-grained spiral grooves. Collected in the storage yard of Shanting Cultural Center. The exact date and location of the excavation are uncertain. Photographs by the authors of this article.

5. Mesopotamian and greco-roman helical columns

This preliminary judgment that the spiral-fluted columns are Western in origin is based on the premise that indigenous Chinese architectural objects did not feature spirally coiled embellishments until the time of the Han dynasty. The earliest extant representations of helical form on the body of a column are found on a green steatite libation vase (ca. 2150 BCE) from Lagash in Neo-Sumeria, showing a relief of two serpents coiling around each other on a pillar (); and on a column consisting of a pair of entwined serpents engraved on an Elamite cylinder (ca. 1600 BCE) () (Stephenson Citation2016, 63–65). These two cases suggest that such helical form originated in early Mesopotamia. Furthermore, concrete spiral columns were first discovered in a building at Tell Al Rimah in Iraq (near Mosul, in northern Iraq) from the post-Assyrian period (911–612 BCE). The walls of this temple are covered with a total of 277 side-by-side columns, fifty of which are giant columns with a rhombus pattern (imitating the trunk of a palm tree) and a spiral pattern (Fletcher Citation1996), according to the results of the site excavation in 1966 ()(Oates Citation1967). Although the aforementioned early Mesopotamian serpent-wrapped columns and post-Assyrian spiral pillars are remarkably similar in subject and content to the Han dynasty dragon-wrapped pillars, there is a time gap of nearly a thousand years and a distance of ten thousand miles between the Mesopotamian examples and the dragon-wrapped column we are examining from Shandong during the Eastern Han period, indicating that there cannot be a direct connection between the two.

Figure 22. Libation vase of Gudea, dedicated to Ninĝišzida. Neo-Sumerian. Lagash (Tello), ca. 2150. BCE. Green Steatite, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Figure 23. Elamite cylinder seal of the judge Ishme-karab ilu, ca. 1600 BCE. Line drawing after Barnett 1987 (Stephenson Citation2016, 65).

Figure 24. Spiral Column of Tell Al Rimah, Iraq. post-Assyrian period (911–612 BCE). Image source: Left:(Oates Citation1967, Plate XXXII b); Right:(Fletcher Citation1996).

The helical serpentine column motif in Mesopotamia, nevertheless, was expanding westward. Various indirect image evidence (such as those appearing on cups, coins, sarcophagi, seals, and frescoes) implies that spiral columns emerged in early ancient Greek civilization in the Aegean region, and later physical remains demonstrate that the distinctive form persisted uninterruptedly throughout the Roman era. For instance, a Lakonian cup depicts a Python (the serpent or earth-dragon in Greek mythology) encircling a pillar, with a Greek warrior opposing it (). A more powerful example is a bronze, columnar, spirally serpentine monument from Delphi, which dates to the Classical period and is said to commemorate the victory over the Persians in 479 BCE (). In all instances, the picture of the coiled serpent connotes the adversarial Persians, bolstering the theory that the theme originated in the East, in Mesopotamia.

Figure 25. A Lakonian cup dated to ca. 550–540 BCE, attributed to the Rider Painter, or Painter of Horsemen, Musée de Louvre, Paris. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/ Art Resource, NY.

Figure 26. The Serpent Column. Left: Part of an ancient Greek sacrificial tripod, originally in Delphi and relocated to Constantinople by Constatine the Great in 324. Originally built after 479 BCE. Right: Drawing of 1574 showing the column with the three serpent heads.

In contrast to the representational “serpentine column,” the helical column was eventually divorced from such symbolism and continued to flourish in the eastern Mediterranean. For example, a marble candelabrum with spiral shaft of two entwined acanthus stalks, appears to have been effectively revitalized throughout the eastern Mediterranean during the late Hellenistic to Roman periods, and had grown in popularity in the region (). More important, the spiral line was abstracted and fused with mature Greco-Roman column design during this period, resulting in the spiral-fluted column. In this regard, the German archaeologist Ludwig Ross conducted a preliminary survey in the nineteenth century; and in 1924, the British School in Athens explored the site of an amphitheater in Sparta, which is located on the slopes of the Acropolis hill below the shrine of Athena Chalkioikos, where preliminary excavations showed spiral columns studded with acanthus leaves ()(Waywell, Wilkes, and Walker Citation1998, 110).

Figure 27. Marble candelabrum with a spiral shaft of two entwined acanthus stalks, in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Source: Photograph by the authors of this article.

In 1956, J. L. Benson published an article detailing more scientifically the spiral columns found at the ancient site of Kourion in Cyprus (Benson Citation1956, 387). The city was founded in the eighth century BCE and abandoned in the fourth century CE due to an earthquake. It flourished during the first century BCE to second century CE. Thus, while the precise dating of these spiral columns is unknown, there is little doubt that they come from the Roman period.

Benson’s interest in spiral columns did not end in Cyprus; in another 1959 piece, he argued that one of the most underappreciated creations of the ancient stonecutter is the spirally fluted column, and included a detailed account of the spiral columns found on the Greek islands (Benson Citation1959, 265). It is difficult to verify the exact dating of these columns because excavation data is frequently lost or columns were reused in subsequent generations of buildings. The composite spirally fluted columns discovered in Athens, Corinth, and Rhodes bear a strong homologous relationship to their later Roman equivalents (). According to Benson, the use of spirally fluted columns and a composite variant related to composite Ionic columns was known in Greece from the Roman imperial periods until the sixth century after Christ, and maybe beyond (Benson Citation1959, 261). The Rhodes Column and the Qian maogu column are similar in both their capitals and their bases, and their bodies are even more strikingly similar, as both have spiral flutes in the upper portion and a straight groove in the lower part (). Although the chronological relationship between the two columns is quite vague, their connection is impossible to explain as simply coincidence. Additionally, when comparing the spiral columns discovered in the other Shandong districts described above to those found in the eastern Mediterranean during the Roman period, there is a clear resemblance in terms of size and style.

Figure 29. Upper left and middle: Column in Qian maogu eastern Han dynasty tomb. Upper right: Spiral fluted columns from Rhodes. Below: Spiral fluted columns from Greece (Benson Citation1959).

More precisely, the growing body of excavated evidence and fieldwork suggests that Asia Minor and its environs may have been the site of the continuation of the Assyrian tradition of spiral column decoration, the most concentrated application of this architectural form from the late Hellenistic to the Roman period, and the birthplace of its outward diffusion. For instance, the second century CE Roman colonnade at Apamea in Syria has spectacular extant relics consisting of spiral columns, each of which has spiral flutes cut in a direction running opposite to those in the column next to it (). Additionally, new excavations at the ancient city of Perge in southern Turkey, some eighteen kilometers from the port city of Antalya, have found a number of marble spiral columns from Roman-era structures (). Esen Ogus described the columnar sarcophagi S-432, S-446, and S-224 from the Roman site of Aphrodisias in southwestern Turkey, which all clearly replicate the use of spiral columns in contemporary building () (Ogus Citation2014, 123). These columns are similar in appearance to those discovered in Tengzhou, China ().

It should be noted, however, that south Shandong is close to China’s eastern coast, which is physically distant from the traditional area inhabited by exotic foreigners and domestic farmers along the Great Wall in the north, as well as the main overland path of the Silk Road on the Hexi 河西 Corridor, a historically significant region in China’s western Gansu province. There are no historical records of Hu-Han battles or Hu dwellings in the region during the Han dynasty. Therefore, the existence of the Maritime Silk Road should be the most acceptable explanation for why the figure of the Hu and accompanying embellishments appear so frequently in graves from the late Eastern Han dynasty.

Therefore, taking all the above-mentioned material and phenomena into account, we are inclined to believe that the late Eastern Han spiral-fluted column discovered southeast of Shandong originated in the eastern Mediterranean region in the Roman period, as a direct outcome of the Maritime Silk Road’s development.Footnote5 However, before reaching a definitive judgment, it would be preferable to gather evidence along this lengthy Maritime Silk Road, going from west to east, in order to make our hypothesis more persuasive, which is undoubtedly a challenging assignment. For now, the closest tangible architectural evidence in South Asia for this theory comes from the second phase of the Ajanta Caves in India, where portions of the spiral ornamentation are apparent, particularly on the pillars of caves from the second half of the fifth century (). While the shape and design of these pillars are unmistakably Indian, and it is debatable whether there is a securely established connection to Western style, there is no spiral design on the body of the pillars in caves 9 and 10 of the first phase of the Ajanta Caves (third century–second century BCE), and no indication of this design has been discovered in early indigenous Indian architectural locations and elements. Thus, the likelihood that the Indian spiral-fluted column also originated in the West cannot be ruled out, despite the fact that it appeared around three centuries later than the Chinese Eastern Han instance discussed in this article.

Figure 33. Ajanta Cave 1 Façade, Exterior, From right. ca. 462–80. Rock-cut stone. Gupta period, Vakataka dynasty, India. © Asian Art Archives, University of Michigan.

Other evidence for the column’s origin as a result of the Maritime Silk Road is Lukas Nickel’s article in 2012 discussing a foreign-looking, lobed-pattern silver box apparently borrowed from Iranian silverware excavated from the tomb of the Nanyue南越King in Guangzhou (mid-Western Han dynasty) () in the second century BCE. The ornament (two bands of tear-shaped lobes facing in alternate directions) has no Chinese precedents but was popular in contemporary Central and Western Asia as well as in the Eastern Mediterranean. Based on residual metal holes on the body of the Nanyue silver box, proof that it was created using Chinese casting technology rather than the cold- hammered technology of Iran, Nickel deduced that this artifact was a combination of foreign style and Chinese technology, and that the silver box was made in China rather than imported.

Figure 34. Silver Box from the tomb of Nanyue King who named of Zhaomo (Nickel Citation2012).

The case of the silver box reveals that Han China may have purposefully adopted a Western Asian pattern, demonstrating that the Chinese were already aware of civilization beyond the Pamir Mountains in the third century BCE. Or, the box might have been included in the enormous corpus of nomadic artifacts and themes that infiltrated Chinese art during this period (Nickel Citation2012). In turn, the example of the box illustrates the role of East-West maritime transport in exchanging products and technology at that time.

Other evidence to support our argument is that Western, Asian-style architectural elements such as Hu statue columns and arched doorways () indicate the influence of foreign styles in some of the large, high-grade Han pictorial stone tombs currently found in this region, such as the aforementioned Wu Baizhuang 吳白莊 tomb in Linyi 臨沂, Shandong.

Figure 35. Western-style architectural elements such as Hu statue columns and arched doorways found in Wu Baizhuang Han tomb in Linyi, Shandong. Photographs by the authors of this article.

If we consider the diverse cultural relics discovered in the same area throughout the Han and Jin dynasties, particularly from the southeast of Shandong to the north of Jiangsu, we can see that Western cultural components may be found in abundance, whether as direct item imports or as indirect exotic aesthetic influence. According to recent studies, the area stretching from the southeast coast of Shandong to the coastal areas of northern Jiangsu was likely to have served as the northern landing port area of the Maritime Silk Road for an extended period of time, with Buddhist statues, cliff carvings, and various other material culture being discovered there.Footnote6 Archaeological discoveries in nations along the Maritime Silk Road, such as the 2001 finding of silk pieces from the early Western Han dynasty in Sri Lanka, underscore the importance of East-West maritime trade during the period.Footnote7 As a result, it is reasonable to infer that the introduction of Western architectural styles and techniques was most likely part of the exchange of cultures and people (including craftsmen) that took place between the East and the West at the time. As for the question of how the dragon-wrapped column came to exist in later buildings, we believe it was a hybrid case which combined the indigenous images of dragon and serpent with the spiral-fluted column structure imported from the West. These gradually merged, evolved, and finally became the dragon-headed column that we see today.

Following the above analysis of the evolutionary process of the serpent-wrapped column and spiral-fluted column from their Mesopotamian origin and their development in the eastern Mediterranean during the Greek and Roman periods, we have a clearer picture of the relationship of these columns to the propagation of the Han dynasty dragon-wrapped and spiral-fluted columns. Although it is difficult to know for certain if their similarity is due to exchange and borrowing – for devising and building a spiral column in either culture was not challenging to begin with – the large number of exotic foreign statues, relief carvings, and flat line carvings found in the Han tombs of Jiangsu, Shandong, Henan, and Anhui indicates that foreign decorative motifs and forms had penetrated deeply into the local Han burial system, which may lead researchers to develop fresh insights and hypotheses about the concept and the act of tomb construction at the time.

Additionally, the location in which spiral-fluted columns were discovered in the Eastern Han is remarkably congruent with the area in which the exotic decorative themes appeared (). Furthermore, as illustrated in , the Chinese spiral-fluted column from the Han tomb is nearly identical to its Greek counterpart. Thus, we might conclude that the Han Dynasty spiral-fluted column has some connection to the ancient Greco-Roman spiral-fluted column, the latter of which is most likely Mesopotamian in origin.

6. Conclusions

It can be challenging to investigate any specific construction technique or decorative form in the realm of ancient Chinese wooden architecture, given the absence of direct and accurate documentation as well as complete architectural remains from before the Tang and Song dynasties. However, such an effort is fundamentally necessary in order to gain a thorough grasp of ancient Chinese architecture and culture. Historically, only the subsurface remains and foundations of early construction projects from the pre-Qin through the Tang dynasties are presently visible, due to extrinsic natural and human-made factors as well as the intrinsic qualities of the timber wooden buildings, the latter of which are often poorly preserved. Fortunately, the Han dynasty’s lavish burial practice resulted in an unintended preservation of a wealth of detailed information about actual building processes and ornamentation, which has become a valuable resource for modern scholars researching Chinese architectural culture prior to the Tang and Song eras.

The existence of the dragon-wrapped column is unequivocally evident in the Song dynasty, but this article shows that the column was also present in the Han dynasty. As a result of our research, we have discovered first-hand, tangible evidence, not only from Han dynasty texts but also from the Han tomb artifacts, that has allowed us to trace the origins of the dragon-wrapped column to the Han dynasty. We have investigated not just the dragon-wrapped column itself but also the two essential design concepts inherent to it, namely the wrapping and winding upward of the ornamentation. This study also draws attention to the fact that spiral-fluted columns existed throughout the Han dynasty and are inextricably linked to early East-West Asian exchanges along the Maritime Silk Road.

Previous scholarship on Chinese architectural history has focused on the indigenous and distinctive technological conceptions of ancient Chinese architecture and construction activities. In reality, a growing number of Han dynasty structural or ornamental components from archaeological finds may point in another direction. The analysis of the decoration of stone columns in Han tombs indicates that, during the Han dynasty’s cultural exchanges between East and West Asia, the importation of foreign architectural forms significantly impacted the period’s construction activities through the incorporation of indigenous people’s decorative motifs and techniques.

We hypothesize that the spiral-fluted column first originated in Mesopotamia, and was then popularized during the Greco-Roman period in the eastern Mediterranean and subsequently transmitted to China via the Maritime Silk Road during the eastern Han dynasty. But the spiral-fluted column never gained popularity or localization once in China, and there were only a few traces of such columns left inside tombs of South Shandong during the latter half of the Eastern Han dynasty. However, spiral-fluted columns did not completely disappear; they were evolved into a column that incorporated the indigenous Chinese theme of dragons and mythological serpents, resulting in the dragon-wrapped pillar that persisted in ancient Chinese architecture for a long period of time.

This article demonstrates a significant reversionary phenomenon in cultural and visual communication. While the Greco-Roman spiral-fluted column is an abstraction of the Mesopotamian serpent-wrapped column, when the former came into contact with the indigenous Chinese tradition of dragon and serpent imagery, it “reverted” to its origins in the Mesopotamian serpent-wrapped column, the difference being that the dragon and snake wrapped around the column in the Han tombs were infused with the belief in Han culture that the dragon and the dragon-related divine serpent could ward off evil spirits., rather than the original Mesopotamian meaning of serpent or Python in the Greek setting.

This article examines the phenomenon of the Maritime Silk Road’s epic dissemination, beginning with the dragon-wrapped column found in many monumental Chinese palaces and temples today, rewriting its history from the Song to the Han dynasties, and revealing that the Han dynasty spiral-fluted column may have originated from exchange via the ancient Greco-Roman Maritime Silk Road, which itself originated from the abstraction and western transmission of the Mesopotamian serpent-wrapped column.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Guan Liu

Guan Liu 刘冠 is the deputy director at Han-Art Institute of Peking University and a Professor at Beijing Forestry University. Liu received his Ph.D. from Peking University in China.

Bing Huang

Bing Huang 黄冰 is an assistant professor of Chinese art at Providence College in the United States and received her Ph.D. from the History of Art and Architecture program at Harvard University.

Notes

1 According to Liang Sicheng, the Han dynasty’s architectural remains fall into two categories: direct and indirect. The construction of tombs, shrines, and que闕 (pair of mark pillars) in the Shandong, Henan, Liaoning, and Sichuan provinces, as well as other scattered components or debris such as stones, bricks, tiles, murals, and stone statues of humans or animals in the Han tombs, are among the direct architectural remains of the Han dynasty. Examples of indirect evidence of architectural remains include pictorial stone carvings discovered in tombs and ceramic models of residences, pavilions, gatehouses, watchtowers, and other supporting constructions. See (Bao, Liu, and Liang Citation1934, 27).

2 Original:“雲楶藻棁, 龍桷雕鏤。 … … 虯龍騰驤以蜿蟺, 頷若動而躨跜。朱鳥舒翼以峙衡, 騰蛇蟉虯而繞榱.” Translated by the authors. Cited in (Wang Citation2000, 71).

3 Original: “楯類騰蛇, 槢似瓊英。如螭之蟠, 如虯之停.” Translated by this author. Cited in (He Citation1986, 529).

4 The stone column is now preserved in Xuzhou Museum.

5 The spiral-fluted style was probably introduced by artisans and masons and eventually entered the tomb-construction industry.

6 The archaeological evidence suggests that the Shandong region was not only a major supplier of export products for the Silk Road but was also a major destination for imported goods and exotic culture during the Han dynasty. See (Yang, Wang, and Sun Citation2018).

7 Ancient Chinese silk relics were discovered in 2011 at the Delivala Stupa archaeological site in Rambukkana, Sri Lanka. Prof. Judith Cameron of the Australian National University led the identification, and discovered that the textile was created in the 2nd century BCE using carbon-14 dating. See (Chandima Citation2011).

References

- Bao, D., D. Liu, and S. Liang. 1934. “Handaide Jianzhu Shiyang Yu Zhuangshi 漢代的建築式樣與裝飾 [Architectural Styles and Decorations of the Han Dynasty].” Zhongguo Yingzaoxueshe Huikan 中國營造學社彙刊 5 (2).

- Benson, J. L. 1956. “Spirally Fluted Columns in Cyprus.“American Journal of Archaeology 60 (4): 385–387. doi:10.2307/500877.

- Benson, J. L. 1959. “Spirally Fluted Columns in Greece.” Hesperia 28 (4): 253–272. American School of Classical Studies at Athens. doi:10.2307/147247.

- Chandima, A. 2011. “Sili Lanka Cang Zhongguo Gudaiwenwu Yanjiu: Jiantan Zhong-Si Maoyi Guanxi 斯里蘭卡藏中國古代文物研究:兼談古代中斯貿易關係[A Critical Examination of Ancient Economic Relationships between China and Sri Lanka Based on Sri Lankan Artifacts].” Shandong University doctoral dissertation.

- Chavannes, E. 1909. Mission Archéologique Dans La Chine Septentrionale. Planches. Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

- Cheng, J. 1989. “Taian Dawenkou Huaxiang Shimu 泰安大汶口汉画像石墓 [Taian Dawenkou Han Pictorial Stone Tomb].” Wenwu 文物 1: 48–58.

- Fletcher, B. 1996. Sir Banister Fletcher’s a History of Architecture. 20th ed./edited by Dan Cruickshank; consultant editors, A. Saint, P. B. Jones, and K. Frampton; assistant editor, Fleur Richards. Oxford; Boston: Architectural Press.

- Fu, X. 2009. Zhongguo Gudai Jianzhushi Dierjuan 中國古代建築史第二卷 [History of Ancient Chinese Architecture Volume 2]. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press.

- Guo, Q. 2010. The Mingqi Pottery Buildings of Han Dynasty China, 206 BC-AD 220: Architectural Representations and Represented Architecture. Brighton [England] ; Portland, Or: Sussex Academic Press.

- He, Y. 1986. Jingfudian Fu景福殿賦 [Rhapsody on the Jingfu Hall], ed. T. Xiao. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House.

- Henderson, G. J. 2018. “Turn, Turn, Turn: The Construction of the Architectural Spiral Fluted Column in the Ancient Mediterranean World.“ Technology and Culture 59 (2): 363–409. doi:10.1353/tech.2018.0033.

- Huang, X. 2003. Hanmu de Kaoguxue Yanjiu 漢墓的考古學研究 [Archaeological Study of Han Tomb]. Changsha: Yuelu shushe.

- Lei, D. 2015. Zhongguo Gudian Jianzhu Tushi 中國古典建築圖釋 [Chinese Classical Architecture Illustration]. Shenyang: Liaoning University Press.

- Li, J. 2006. Yingzao Fashi營造法式corrected and Annotated by Zou Qichang 鄒其昌. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

- Li, J. 2011. Zhongguo Gujianzhu Mingci tujiecidian 中國古建築名詞圖解辭典 [An Illustrated Dictionary of Chinese Ancient Architectural Terms]. Taiyuan Shi: Shanxi Science and Technology Press.

- Liang, S. 2001. Liang Sicheng Quan Ji 梁思成全集 [The Complete Works of Liang Sicheng]. Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe.

- Liang, Y., and Q. Meng. 1997. “Jiangsu Tongshanxian Banjingcun Donghanmu 江蘇銅山縣班井村東漢墓 [Eastern Han Tomb in Jiangsu Province Tongshan County Banjing Village].” Kaogu 考古 5: 40–45.

- Nickel, L. 2012. “The Nanyue Silver Box.” Arts of Asia 42: 98–107.

- Oates, D. 1967. “The Excavations at Tell Al Rimah, 1966.” Iraq 29 (2): 70–96. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq. doi:10.2307/4199827.

- Ogus, E. 2014. “Columnar Sarcophagi from Aphrodisias: Elite Emulation in the Greek East.“ American Journal of Archaeology 118 (1):113–136. doi: 10.3764/aja.118.1.0113.

- Ogus, E. 2018. Columnar Sarcophagi from Aphrodisias. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag.

- Pan, L. 1983. “Zhejiang Haining Donghan Huaxiangshi Fajue Jianbao 浙江海寧東漢畫像石墓發掘簡報 [Briefing on the Excavation of the Eastern Han Pictorial Stone Tomb in Haining, Zhejiang].” Wenwu文物 5: 1–20.

- Stein, A. 1912. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal Narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China. London: Macmillan.

- Stephenson, P. 2016. The Serpent Column: ACultural Biography. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Tokiwa, D. 1914. Shina bunka shiseki: Zuhan. Tōkyō: Hōzōkan.

- Wang, Y. 2000. Lu Lingguangdian Fu 魯靈光殿賦 [Rhapsody on the Hall of Numinous Brilliance in Lu]. T. Xiao and W. Z. 昭. 明. 文. 選. 注. 析. Zhaoming, Xi’an: Sanqin Publishing House.

- Wang, K., and K. Xia. 1985. “Jiangsu Xinyi Wayao Hanhuaxiang Shimu 江蘇新沂瓦窯漢畫像石墓[Han Pictorial Stone Tomb in Jiangsu Xinyi Wayao].” Kaogu 考古 7: 614–626.

- Waywell, G. B., J. J. Wilkes, and S. E. C. Walker. 1998. “The Ancient Theatre at Sparta.” British School at Athens Studies 4. The British School at Athens: 97–111.

- wenhuaju, A. 1992. Anqiu dongjiazhuang hanhuaxiang shimu 安丘董家莊漢畫像石墓 [Stone relief tomb of Han dynasty in Anqiu county Dong Jia Zhuang village]. Jinan: Jinan Publishing House.

- Xie, J. 2020. “Pillars of Heaven: The Symbolic Function of Column and Bracket Sets in the Han Dynasty.“ Architectural History 63: 1–36. doi:10.1017/arh.2020.1.

- Xing, Q., Z. Fang, and J. Guo. 2015. “Shandong Jiyangxian Baiyangdiancun Handai Huaxiangshimu Fajuejianbao 山東濟陽縣白楊店村漢代畫像石墓發掘簡報 [A Brief Introduction to the Excavation of Han Dynasty Pictorial Stone Tomb in Shandong Jiyang County Baiyangdian Village].” Dongnan Wenhua 東南文化 6: 43–49.

- Yang, X. 2009. “Jiangsu Xuzhou Chutu Handai Lingmu Shidiao 江蘇徐州出土的漢代陵墓石雕 [A Stone Carving of a Han Dynasty Tomb Excavated in Jiangsu Xuzhou].” Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 1: 80–85.

- Yang, A. 2013. “Cong Shiguo Dao Shishi 從石槨到石室 [From Shiguo to Shishi].” Qilu Wenwu齊魯文物 2: 12–25.

- Yang, A., H. Wang, and Y. Sun. 2018. “Handai Shandong Yu Sichouzhilu: Yi Kaogufaxian Weizhude Guancha 漢代山東與絲綢之路:以考古發現為主的觀察 [Shandong and the Silk Road in the Han Dynasty: An Archaeological Discovery-Based Observation].” Haidai Kaogu 海岱考古: 498–523.

- Zhang, L. 2002. Jiangxue Qishuo 匠學七說. Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe.

- Zhang, Z. 2011. Handai Huaxiang Zuanshi Muzang de Jianzhuxue Yanjiu 漢代畫像磚石墓葬的建築學研究 [An Architectural Study of Han Dynasty Pictorial Stone Tombs]. Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou guji chubanshe.