ABSTRACT

This study discussed how seating arrangements and seat selection influence interactions between older people. Two congregate meal sites were selected for the experiment, and a nonparticipant observation was adopted wherein the entire dining process of older people at the site was examined. Further adjustments were then made to seating arrangements and an evaluation of the benefit thereof was made. Observation revealed that over 90% of the participants selected the same seat at each gathering. Participants tended to sit in the same or relatively similar location; additionally, participants who sat in the same area tended to share similar behavioral features. After adjusting the seating arrangements, this study discovered that an orthogonal seating arrangement greatly reduced bilateral gazing and lessened the stress of some participants. A face-to-face seating arrangement can encourage not only bilateral and unilateral gazing but cross-sectional conversation behaviors for participants who linger for a longer mealtime.

1. Introduction

In 2002, the World Health Organization proposed active aging that aims to delay the aging process by encouraging participation by older adults in family, community, peer, and social activities. As a result, adult day service centers (ADSCs) are becoming a preferred option for community-based long-term care for ethnically diverse older adults with chronic health conditions (Institute Citation2010). It provides supervised care to more than 286,000 chronically ill individuals in the United States, nearly 60% of whom are racial or ethnic minorities (cornell, a Citation2019). It also provides an interactive, safe, and secure environment for older adults who require supervised care during the day (Sadarangani and Murali Citation2018). Access to regular meals through the ADSC was a critical component to perceived improvements in quality of life and self-rated health among ethnically diverse ADSC clients (Sadarangani and Murali Citation2018; Dubus Citation2017). Proper nutrition is also an essential part of managing the care of ADSC clients with dementia. Taiwan officially became an aging society in 2018 and is estimated to advance to classification as a super-aged society by 2025. Because of its value to older adults, the government has begun to promote congregate meal services in local communities and foundations. However, the food services provided for senior citizens are generally carried out in a rational (Sydner Mattsson Citation2005) and routine (Harnett Citation2010) manner, and volunteers tend to limit their interactions with residents (Hung and Chaudhury Citation2011), and these tend to undermine the goal of promoting active aging.

The U.S. Evaluation Report of the Elderly Nutrition Program (Ponza et al. Citation1996) compared congregate meals and meal delivery services. Most senior citizens who participated in the activity showed more interest in interacting with other senior citizens rather than in the meal delivery service. Although meal services can meet the bare physiological needs of the participants, the social aspect of the service is as essential as the nutrition aspect. Rowe and Kahn (Rowe and Kahn Citation1998) proposed three key traits of a successfully aging senior citizen, namely (1) low risk of sickness and disability, (2) maintenance of strong physical and psychological functions, and (3) active engagement with life. Nomura et al. (野村知子 et al. Citation1999) concluded that congregate dining activities are beneficial to both physical and psychological health. The participants in their study reported that interactions with others and meeting volunteer workers were both positive experiences. Jacobson, O’Hanlon, Bennett, & McCloskey (O’Hanlon et al. Citation2004) also asserted that opportunities for social interaction provided by senior centers benefit participants physically and psychologically and reduce participants’ risks of depression, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, Gitelson, Ho, Fitzpatrick, Case, & McCabe (Gitelson et al. Citation2008) examined the advantages of congregate meal services. Participants in this study stated that the meal served at the congregate meal site adequately provides essential daily nutrients and the social atmosphere enables participants to make new friends and maintain friendships. Thus, excellent congregate meal services not only provide senior citizens with their nutritional needs but establish an environment conducive to making new friends and maintaining friendships. Senior citizens can obtain a sense of belongings by participating in the congregate meal activities.

The current study investigated care home residents’ experiences of their care, focusing on their experiences of mealtimes. Mealtimes are an integral part of day-to-day life in a care home (Savishinsky Citation2003) and are pivotal for delivering care. Therefore, the mealtime experience may be an essential catalyst for residents’ health, well-being, and quality of life. Yet, a recent systematic review concluded that there is a paucity of research about the resident experience of mealtimes in care homes (Watkins et al. Citation2017). Existing research suggests a positive effect of mealtime interventions on nutritional outcomes of residents and the behavior symptoms of people with dementia(Abbott et al. Citation2013; Whear et al. Citation2014). Mealtimes represent more than just the provision of nutrition; they may offer residents (and staff) the opportunity to form and sustain critical social relationships. Food is used to provide comfort, express feelings, celebrate or reward success, and nurture companionship (Grodner, AnderSon, and Deyoung Citation2000). Eating occasions are integral to tradition, family life, and identity (Philpin et al. Citation2014). In stressful situations or unfamiliar environments, or when the notion of identity is compromised, food (and the social connections to it) may significantly influence the quality of life (Evans, Crogan, and Shultz Citation2005). Mealtimes have a critical socio-cultural role in the care of older people; existing interventions are characterised by their focus on single components and lack the complexity associated with health and well-being determinants (Abbott et al. Citation2013; Whear et al. Citation2014; Vucea, Keller, and Ducak Citation2014).

The seating arrangement at a congregate meal site can affect people’s behaviors (Sommer Citation1967). The arrangement of seats and the distance between seats influences the sitting position and interactions between sitters (Sommer Citation1967). The book Body Language by Allan (Pease Citation1988) introduced four types of seating positions, namely cooperative, independent, competitive–defensive, and corner positions, that one could take at a rectangular table. If one individual is already seated, the seat chosen by a subsequent individual is indicative of his or her relationship with the first individual and affects the quality of their interaction. Dartford (Dartford Citation1990) also identified all types of seating arrangements currently available in dining spaces and offered general measurements based on modular applications and changes in the number of participants with which to evaluate them. In Body Language (Pease Citation1988), Pease presented the common arrangements of three basic table shapes: square, round, and rectangular. The type of table and its use yield different interactions in terms of the host–guest relationship that develops between the participants. Robson (Robson Citation2002) analyzed the seating arrangements at 10 chain restaurants and determined that the ratio of permanent or semipermanent anchored seats affects diner ability to maintain personal space and privacy. The results showed that restaurants with 80% or more anchored seats satisfied the preference of low-context consumers, whereas the placement of 90% or more anchored seats next to exterior or partition walls reduced customers’ eye contact with others and the feelings of personal space invasion. Kimes and Robson (Kimes and Robson Citation2004) explored how consumers’ expense per minute, checkout amount, and dining time were associated with seating arrangements. The results indicated that customers sitting in a booth, which provides the most privacy, incur the most expense per minute and checkout amount and dine for the longest time. By contrast, customers seated in an open area have the lowest checkout amount on average and a shorter dining time. The article “Musical Chairs (Choosing the Right Seat)” published by Alex Cornell from Firespotter Labs in 2013 provided an interesting explanation for the seat selection of a group of people. To attain the most interaction opportunities with others, when selecting a seat, a participant will select a seat on the basis of their relationship with others and usually avoid being the first to take a seat; this is a hedge against foreclosing the possibility of sitting beside a close acquaintance. Robson (Robson Citation2008) discovered that diner seat selection is influenced by their stress level. Diners under considerable stress prefer seats with more anchor points (viz., those with more privacy), whereas those under less stress tend to take seats against windows or walls; this indicates that when in an unfamiliar dining space, diners’ seat selection behaviors vary because of emotional factors. Hwang and Yoon (Hwang and Yoon Citation2009) examined consumers’ seat selection preferences in a dining space and noticed that seats with more privacy and a view are favored by most consumers compared with locations with a high flow of people and low privacy (e.g., seats near the entrance). In a discussion of restaurant management principles, Thompson (Thompson Citation2010) contended that the seating arrangement in a restaurant can affect its seating capacity and management should consider whether anchoring tables and chairs can better meet the requirements of diners. Moreover, some researchers have emphasized the psycho-affective dimensions of food intake and mealtime and pointed out the effects of meal context in nursing homes on residents’ appetite (willingness to eat) and food intake (Wikby and Fägerskiöld Citation2004, 30; Divert et al. Citation2015). In France, Pouyet investigated food attractiveness and consumption in public residential facilities for dependent seniors (more commonly referred to by their acronym, EHPAD), catering mainly to people with cognitive impairments. She demonstrated that attractiveness and consumption depended on sensorial factors (visual aspect, flavor, texture and temperature), cognitive factors (familiarity, sociocultural identity, reminiscence and ease of digestion), and food plating (aspect and quantity) (Pouyet Citation2015). She also showed that cognitive impairment played a significant role in the amount of food consumed (e.g., difficulty eating) but that mealtime assistance, level of dependence, and resident’s social network played a huge role.

Diners typically consider factors other than how seating influences their interactions with others at the same table; for example, they are sensitive to the relative position of a seat within the space, whether anchor points exist around the seat, the flow of people, and whether a seat provides a good view. Nowadays, the congregate dining environment is managed by each congregate meal site. However, most sites have been designed with a focus on staff and venue convenience with respect to storage and movement of tables and chairs; consequently, the needs of senior citizens have been discounted, resulting in suboptimal opportunities for social participation and less strong psychological and physical outcomes from participation in such dining (Pouyet Citation2015). The emphasis should be shifted to promote a better experience for senior citizens (Ericson‐Lidman and Strandberg Citation2015).

This study discussed how seating arrangements and seat selection influence interactions between older people. Two congregate meal sites were selected for the experiment, and a nonparticipant observation was adopted wherein the entire dining process of older people at the site was examined. This study designed a congregate dining space for senior citizens based on nonparticipant observation to promote interaction between senior citizens, improve their dining experience in mealtimes, and enable their activities to meet their psychological need for social participation.

2. Materials and methods

This study was conducted in three stages. First, a site investigation was conducted to identify representative congregate meal sites. Then, the condition of the selected meal sites was closely observed to determine the numbers of participants, overall mealtimes, typical seat selections, and diner behaviors. After the collected information was organized, a new spatial arrangement was created and implemented and then evaluated to determine whether it was beneficial.

2.1. Study sample

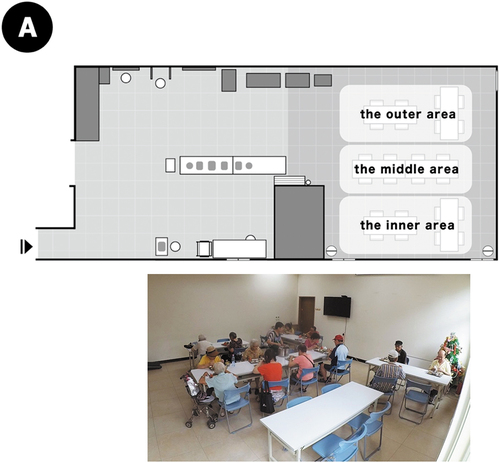

This study visited nine of the senior congregate meal sites listed by the Taipei Department of Social Welfare and identified representative congregate meal sites on the basis of their scale and frequency of service to ensure a stable number of participants throughout the survey. Finally, two sites, referred to here as site A and site B, were selected as research sites for A broad study of the general pattern of elderly dining in different spaces.

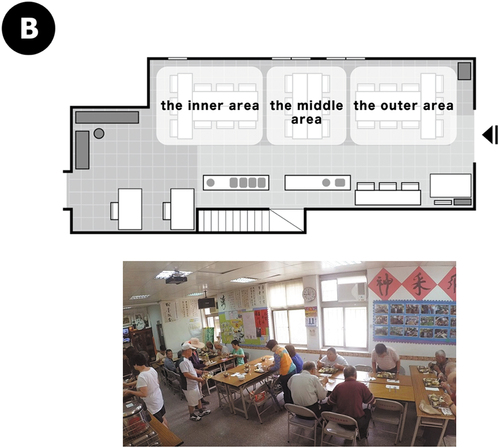

Both sites are private institutions that have already screened the criteria for participants, all of whom are over 65 years old. A total of 67 (34 men, 33 women) and 76 participants (47 men, 29 women) signed up for the activity at Sites A and B, respectively.

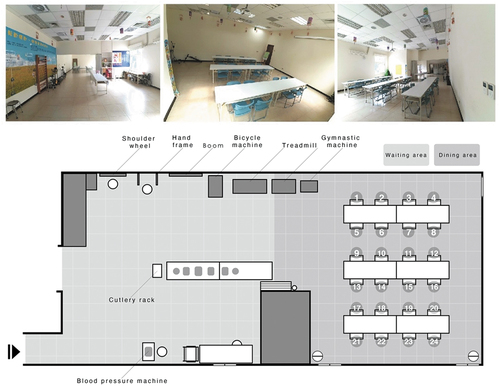

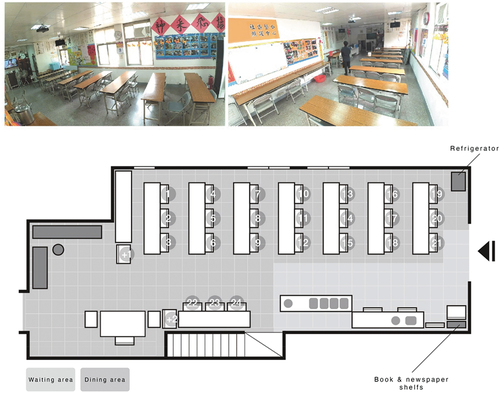

Site A. This site was graded “excellent” in the Social Care Center Evaluation 2018. The congregate dining activity in the village is open only to senior citizens aged 65 years and above, and meal service is 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. from Monday to Friday. Site A is in a regular cooperation with a central kitchen and is equipped with rectangular dining tables. Two people can be seated on each long side of the tables, but sometimes three sit on a side when senior citizens choose to cluster themselves on a side ().

Site B. The congregate dining activity in this village is open only to senior citizens aged 65 years and above, and meal service is 11:30 a.m. to 12:10 p.m. from Monday to Friday. Site B also has a central kitchen it regularly cooperates with and is equipped with two types of rectangular dining tables, both of which accommodate twelve seats. Folding chairs are stored at the side of the room, and senior citizens can use them as needed ().

2.2. Method

This study is based on the existing area for investigation. We used the Non-participant observational method. Experimenting with the most natural does not interfere with looking at an object. The researchers, without intervention activities, use the camera to record in detail the actual circumstances of the dining field, avoid the dis-turbance observer’s dining process, and obtain conforms to the real situation of information. Before the investigation, we had obtained management permission to conduct this recording process. We also verbally informed the diners and obtained their consent. We arranged three cameras with different camera angles in field A and field B. Cameras were used to scrutinize selected dining locations to determine the number of participants, overall meal times, typical seating choices, and dining behavior.

A total of four observations were recorded at each site during the lunch period, and each recording lasted about one hour, with slight differences depending on the actual meal situation. We made statistics on the seating preference of each participant at each meal serving and observed the habitual characteristics of the participant in choosing the location. We recorded each participant’s meal and stayed time and the communication and interaction among participants. Including the room for all the behaviors of the elderly entering the space, serving food, choosing a seat, eating, staying after the elderly, and leaving. After col-lating the information collected, create and implement a new spatial arrangement, which is then evaluated to determine benefits.

We divided the whole dining activity into three parts: members’ attendance, interaction with space, and members’ behaviors during the dining process. Furthermore, by using the model of interdependence proposed by Levinger (Levinger Citation1980), this study established the two stages in interpersonal relationship development, unilateral awareness and bilateral surface contact. This model focuses on how interpersonal relationships develop from unilateral to bilateral disposition and from superficial to in-depth contact. The observed behaviors are listed in the following table ()., such as talking (CV), looking around (LA), killing (GZ), watching others interact (GO), and so on. The frequency and duration of participants’ nonverbal communication behaviors, such as nodding (ND), waving (WH), and gesturing (GE), were counted.

Table 1. Observed behaviors.

The data from these observations provided the basis for the subsequent determination of the space requirements of the site. In this study, we implemented new seating arrangements to the space requirements of stage 2, implemented new structures at venues A and B, and assessed the proposal’s benefits. The same observations were made again, comparing whether the new seating scheme improved participants’ interaction.

3. Results

3.1. Member composition and attendance

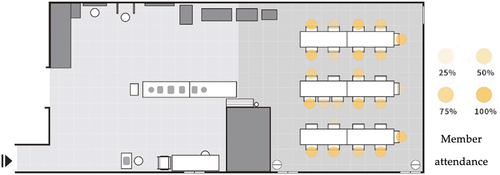

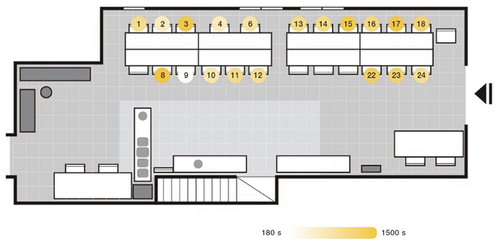

Site A. The outer table seats were evenly selected, and almost every seat was taken. The seats at the middle table were evenly selected as well. A participant would move his or her chair around to sit alongside two other participants. A seat on the outer side of this table and between two participants was never taken, and the additional seat at this table was rarely selected. At the inner table, seats on the inner side and also the additional seat were preferred. A seat selection pattern was evident at Site A.

At Site A, more than 50% of participants tended to sit at the same seat repeatedly. Seventeen participants selected the same seat in all four instances of observation, and the overall rate of repeat seat selection was as high as 92%. Attendance varied among participants. Three participants had an attendance rate of 25%, and another three had a rate of 50% (). The male-to-female ratio was relatively even; men and women were 50.7% and 49.3%, respectively, of the participants at Site A. Before the activity began, 28.4% of the participants were already seated. This could be considered a resting behavior, or they were ensuring the seat would not be taken by another participant. Half the participants brought personal items (e.g., bags) to the site; each participant brought 1.4 items on average.

Site B. The four outer tables near the door were evenly selected by participants, and every seat was taken. The three inner tables were selected in a random manner, and the middle seat was never taken at two of the inner tables. The three seats at the table on the side and the one next to the innermost long table were usually taken. At Site B, the outer seats and those close to the inner aisles were regularly selected.

With regard to seat selection, the repetition of all participants at Site B were above 50%. Eighteen participants always selected the same seat during the four observations, and the overall rate of selecting the same seat was 90.9% (). Compared with Site A, the attendance at Site B was more regular, but the seat selection pattern at Sites A and B did not vary greatly. Specifically, some participants preferred to always have the same seat.

At Site B, more men (61.5%) than women (38.5%) signed up for the activity. Before the activity started, 34.6% of the participants were already seated. Each participant brought 1.7 items with them on average. Compared with Site A, approximately 10% more participants brought personal items, implying that participants at Site B had a greater demand for personal item storage.

3.2. Seat selection and overall dining time

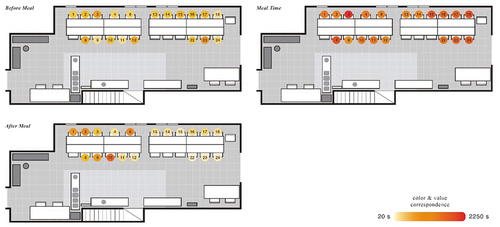

At Site A, the time spent before and after meal at the tables was highest to lowest in the following order: outer, middle, and inner tables. Participants at the inner table spent the least time at the table in all three stages (i.e., before the meal, during meal time, and after the meal). During meal time, participants at the middle table spent the most time at the table and participants at the outer table exhibited the greatest variation in overall dining time ().

At Site B, participants in the aisle seats at the inner table exhibited an irregular distribution of time spent before meal time, whereas those at the outer table exhibited a relatively regular distribution. The time spent on dining declined from right to left for participants at the outer table. The overall dining time spent by the majority of participants at the inner table was even but slightly lower than time spent by participants at the outer table. After the meal, participants at the outer table did not exhibit great differences in the time spent on cleaning; however, those at the inner table spent more time on cleaning on average and had highly variable distribution. In summary, the time spent after meal time for participants at the outer table at Site B, where the spatial arrangement was rectangular dining tables on both sides, was relatively shorter and the time spent by each participant was even (). However, the time spent after meal time for participants at the inner table was longer, and the time spent by each participant was uneven ().

Table 2. Overall Dining Time at Site A & B (Bilateral Dining Table).

3.3. Seat selection and dining behaviors

At Site A, the time spent at the table during meal time for participants at the outer table descended for participants seated right to left and differed greatly between participants. Participant 1 spent the most time at table, participants 4 and 3, seated nearby 1, were above average, and participant 2, a volunteer at the site, had an entirely different pattern of behavior. The time spent at the table during meal time for participants at the middle table declined from left to right and was relatively consistent. Except for participant 23, the remaining participants spent a below average amount of time at the table ().

Figure 7. Relationship between the time spent at the table during meal time and seat selection at Site A.

At Site B, participants at the inner table exhibited high variability in the time spent at the table during meal time. Participants 3 and 8 spent the most and third most time, and their times greatly exceeded the time spent by the participants nearby. Participant 9 spent the least time at the table. The time spent during meal time was more even for the participants at the outer table ().

Generally, no direct relationship was discovered between the time spent at a table during meal time and seat selection. At Sites A and B, the average time spent concentrating on dining (DC), the average times of DC, and the average DC duration per occasion all accounted for approximately 64% of the overall dining time ().

Table 3. Comparison of the Time Spent Concentrating on Dining (DC) at Site A and B.

Table 4. Interactive Behavior and Conversation (CV).

3.4. Congregate dining activity process

Although slight differences were evident between the congregate meal sites, based on the activity process at each site, the general process of congregate dining can be divided into five stages: entering the room, waiting, food distribution, meal consumption, and after meal. For rehabilitation activities, the sites provided a shoulder wheel, weight cable machine, and arm extension device, which were placed on or against the walls. Only one participant at Site A used the equipment, for a total time of 153 seconds. During operation, the participants did not interact with others in any particular manner. Participants tended to face the entrance and serving area while operating the equipment; therefore, they were able to perceive the situation at the entrance and be alert to meal service.

3.1.1. Food distribution and participant’s behaviours

Only volunteers at Site A distributed the food at meal time. Distribution was divided into two rounds taking a total of 188 seconds. Unilateral gazing (GZ) and gazing at the interactions of others (GO) occurred because of the movements of the volunteers and interactions with others. A ratio calculation between the occurred behavior due to food distribution and the total behaviors produced by participants was conducted, and the results revealed that up to 13.3% of the bilateral GZ behaviors and 10% of the unilateral GO occur because of food distribution. An average of 17.6-second interaction made by each participant was derived from the nearly 10 second interaction with the volunteer during food distribution ().

Table 5. Behaviors During Food Distribution in Site A.

3.1.2. Tableware returning and participant lingering

Only participants at Site A were responsible for returning their own tableware. The tableware return area was located in the service area, which was some distance from the seating area; therefore, if participants wanted to interact with others sitting nearby, they would leave their plates and tableware on the table or return them and then return to their seats. Fifty-six percent of the participants were observed leaving the site after returning their tableware, 22% returned their tableware and returned to their seat, and 11% lingered at the site after returning their tableware or washing the tableware they brought by themselves. At Site A, more than half the participants left their plates and tableware on the table after the meal and did not return them until they were about to leave. Although retrieval of tableware by volunteers was considered a more effective measure, the organizers thought that the congregate dining activity should encourage participants to do tasks they are capable of doing by themselves (e.g., returning tableware or cleaning up their table). These tasks give participants the opportunity to be active and also improve the quality of the activity.

3.1.3. Proposals for new seating arrangements

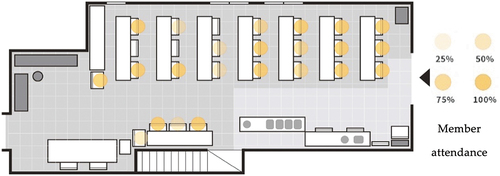

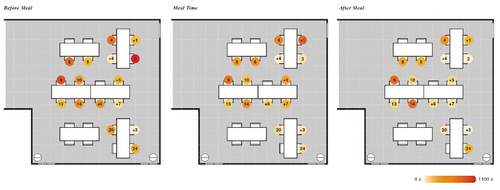

The proposal for a new seating arrangement at Site A was designed to encourage cross-sectional interaction between participants by changing the direction of the tables on the right side in the outer and inner table areas. An orthogonal seating arrangement was implemented to expand participants’ visual range (). Furthermore, the seats were divided into three areas, namely the outer, middle, and inner areas, and the results of the adjustments were compared with those of the former arrangement.

A middle area was added to Site B to enable a comparison between changes in the outer and inner areas, as well as determining behavioral differences between participants in the middle area and those in the other two areas. The aim was to create a seating arrangement that encourages cross-sectional interaction between participants. An orthogonal seating arrangement was implemented to reduce the chance of eye contact. By adjusting the direction of the seats, participants could have a wider visual range; additionally, unilateral and interaction behaviors could be increased because of the orthogonal relation between the middle area and the other two areas ().

4. Discussion

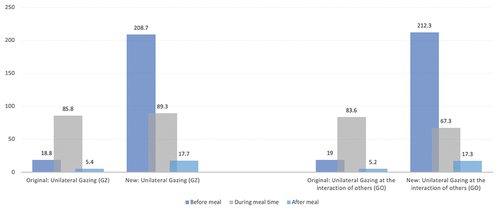

The time spent on four of the behaviors increased at Site A. From observation, CV increased 63.7%, unilateral GZ increased 47.5%, unilateral GO increased 59.7%, and bilateral GO increased 69.1%. However, the other two behaviors took less time, and looking around (LA) and bilateral GZ decreased 67.5% and 27.2%, respectively ().

Table 6. Site A Comparison of the Results of Observation and Verification for Each Behavior.

After the adjustment, participants at Site A were observed to engage in more cross-sectional CV before and after the meal. This suggested that the reduced distance and the changes in the direction of the seats facilitated communication. Additionally, before and after meal time, participants were not restricted by the dining position. Participants who left their seats after finishing dining opened up obstructed sightlines, which led to more opportunities for cross-sectional interaction. Bilateral CV and GO were noticeably increased; however, bilateral GZ behaviors were reduced after the adjustment in seating arrangement (). This suggested that most bilateral interaction behaviors increased after the adjustment. The decrease of bilateral GZ occurred because the original face-to-face arrangement was changed to an orthogonal one, which reduced the occurrence of bilateral GZ.

The unilateral GZ and GO behaviors of participants at the inner table changed after the adjustments were made. Unilateral behaviors greatly increased before-meal time. During meal time, less unilateral GO behaviors were evident, but more unilateral GZ behaviors were observed. After the meal, both behaviors had increased compared with their performance in the former arrangement (). The results revealed that participants’ behaviors were influenced to a certain degree by the changes in time duration before meal; in addition, participants who took a seat early and exhibited unilateral interactions also increased. This showed that with more waiting time before the meal, more participants would take a seat first, which resulted in more flexible seat selection and an increase in the interaction opportunities that also affected unilateral interaction behaviors.

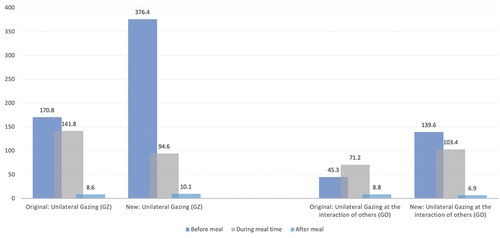

At Site B, the time spent on unilateral GZ, unilateral GO, and bilateral GO increased by 65.7%, 65.9%, and 23.0%, respectively. However, CV, LA, and bilateral GZ decreased by 0.3%, 94.8%, and 80.5% ().

Table 7. Comparison of the Results of Observation and Verification of Each Behavior at Site B.

After the meal, several participants at the middle and inner tables initiated cross-sectional CV. When almost all participants had finished their meals, the participant +7 at the inner table began to interact with participant +1 at the middle table. Although they were sitting a relatively far distance apart, interactions easily occurred because they were sitting opposite each other, with no other participants between them. Subsequently, more participants engaged in the interaction. Participants +8 and +7 approached the middle table and talked with several participants before leaving. This indicated that this type of distant face-to-face seating arrangement is likely to stimulate cross-sectional interactions before and after meals for participants who engage in more bilateral interactive behaviors(). The CV behavior did not change at Site B; however, bilateral GO had a considerable increase, which implied that this type of arrangement continued to facilitate bilateral table communication behavior and further increased the number of participants who engaged in the interaction. The T-tables at both ends enabled easier interactions with others.

The reason for switching the bilateral table on the side to a unilateral table was that some participants felt stress engaging in bilateral interactions. After the adjustment was made, participants at this table spent less time in bilateral GZ and GO, which signified that a vertical seating arrangement effectively reduced eye contact between participants (). The adjustments lessened participants’ stress and created a more pleasant dining space for those who are not comfortable with bilateral interaction.

Furthermore, participants at this table had a considerable increase in unilateral interactive behaviors after the adjustment, particularly before the meal. Unilateral GO also took place more frequently during meal time, which proved that the participants at the outer table could engage in unilateral interaction more conveniently ().

The observation of the original seating arrangement revealed that most participants tended to select a certain seat and regularly sit with certain members; additionally, they also tended to save seats by using their personal items. Between the original arrangement and the new adjustment, no considerable changes occurred in the overall dining time, and the time spent during meal time under both arrangements accounted for approximately 64% of the overall dining time, accounting for the highest proportion of all stages of the congregate dining activity. The results of this study revealed that CV is the behavior that occupies the most time. Less CV occurs when a participant sits one or more seats apart from another participant on the same side or is seated in a back-to-back arrangement. If participants sit face-to-face and are not separated by objects or individuals, CV continues despite being seated apart. Unilateral GZ is the behavior that consumes the second most time. It occurs mostly before the meal and during meal time but greatly declines after the meal. Bilateral GZ is more likely to occur between participants sitting opposite to each other. This behavior has a communicative effect; however, excessive bilateral GZ cause stress for some participants.

In general, this study determined that a space wide enough for an individual to pass through should be reserved between two participants who are sitting on the same side. To save space for a wider aisle, the distance between the seats and the objects behind should be considered. The width and the relative position of aisles should also be designed to accommodate wheelchair and walker users as well as the use of dining carts. Furthermore, for participants with similar behaviors who are sitting in different areas, visual barriers should be removed through adjustments to the seating arrangement. This can facilitate participant engagement in cross-sectional interactions or seat changes. Organizers should provide seats that are more convenient for CV or more closely spaced for participants who linger for a long time after the meal.

This study also discovered that CV and unilateral and bilateral GZ and GO behaviors are all influenced by space arrangements. Corner seating encourages more participants to engage in interactions. Participants sitting at the table facing the wall exhibited less GZ and GO behaviors. Seats placed on the side and facing the interior space should be provided for participants who prefer unilateral interactions to reduce their visual barriers. In addition, an orthogonal seating arrangement can reduce participants’ stress that results from bilateral GZ behaviors. Food service volunteers determine the amount of food each participant receives, and food distribution can even trigger a certain degree of bilateral GZ and unilateral GO behaviors. People-oriented care requires the awareness of the well-being of residents and health care providers alike (Tellis-Nayak Citation2007).

5. Conclusion

This study discovered that an orthogonal seating arrangement significantly reduced bilateral gazing and lessened the stress of some participants. A face-to-face seating arrangement can encourage bilateral and unilateral gazing and cross-sectional conversation behaviors for participants who linger for a longer mealtime. Understanding all participants’ behaviors at the congregate meal site is beneficial for establishing a suitable seating arrangement and can further improve the quality of the congregate dining service. This study visited nine of the senior congregate meal sites listed by the Taipei Department of Social Welfare, and two sites were selected as research sites. The subjects of this study only focus on the congregate meal environment in Taiwan. We did not consider national dietary habits and cultural differences, although we believe these differences may affect the table layout of the dining environment. In addition, many public congregate meal spaces are gradually opening up to other non-senior users, such as children. Diverse users’ behavior is one of the future directions of congregate meal research, considering the diversity of users eating and communicating.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbott, R. A., et al. 2013. “Effectiveness of Mealtime Interventions on Nutritional Outcomes for the Elderly Living in Residential Care: A Systematic Review and meta-analysis.” Ageing Research Reviews 12 (4): 967–981. DOI:10.1016/j.arr.2013.06.002.

- cornell, a. “Musical Chairs (Choosing the Right Seat).” 2019. https://www.alexcornell.com/musical-chairs-choosing-the-right-seat/

- Dartford, J. 1990. Architects’ Data Sheets. Dining Spaces. London: Architecture Design and Technology.

- Divert, C., et al. 2015. “Improving Meal Context in Nursing Homes. Impact of Four Strategies on Food Intake and Meal Pleasure.” 139–147. Vol. 84. Appetite.

- Dubus, N. 2017. “A Qualitative Study of Older Adults and Staff at an Adult Day Center in A Cambodian Community in the United States.” Journal of Applied Gerontology 36 (6): 733–750. doi:10.1177/0733464815586060.

- Ericson‐Lidman, E., and G. Strandberg. 2015. “Troubled Conscience Related to Deficiencies in Providing Individualised Meal Schedule in Residential Care for Older people–a Participatory Action Research Study.” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 29 (4): 688–696. doi:10.1111/scs.12197.

- Evans, B. C., N. L. Crogan, and J. A. Shultz. 2005. The Meaning of Mealtimes: Connection to the Social World of the Nursing Home, 11–17. NJ: Slack Incorporated Thorofare.

- Gitelson, R., et al. 2008. “The Impact of Senior Centers on Participants in Congregate Meal Programs.” Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 26 (3).

- Grodner, M., S. AnderSon, and S. Deyoung. 2000. Foundation and Clinical Applications of Nutrition. St, 293. Louis: Mosby.

- Harnett, T. 2010. “Seeking Exemptions from Nursing Home Routines: Residents’ Everyday Influence Attempts and Institutional Order.” Journal of Aging Studies 24 (4): 292–301. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2010.08.001.

- Hung, L., and H. Chaudhury. 2011. “Exploring Personhood in Dining Experiences of Residents with Dementia in long-term Care Facilities.” Journal of Aging Studies 25 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2010.08.007.

- Hwang, J., and S.-Y. Yoon. 2009. “Where Would You like to Sit? Understanding Customers’ privacy-seeking Tendencies and Seating Behaviors to Create Effective Restaurant Environments.” Journal of Foodservice Business Research 12 (3): 219–233. doi:10.1080/15378020903158491.

- Institute, T. M. M. M. 2010. “The MetLife National Study of Adult Day Services.” Providing Support to Individuals and Their Family Caregivers.

- Kimes, S. E., and S. K. Robson. 2004. “The Impact of Restaurant Table Characteristics on Meal Duration and Spending.” Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 45 (4): 333–346. doi:10.1177/0010880404270063.

- Levinger, G. 1980. “Toward the Analysis of Close Relationships.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 16 (6): 510–544. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(80)90056-6.

- Nijs, K., et al. 2009. “Malnutrition and Mealtime Ambiance in Nursing Homes.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 10 (4): 226–229. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2009.01.006.

- O’Hanlon, J., et al. 2004. The Impact of Senior Centers and Geriatric Healthcare Policy. Institute for Public Administration.

- Pease, A. 1988. Body Language. Camel Publishing Company.

- Philpin, S., et al. 2014. “Memories, Identity and Homeliness: The Social Construction of Mealtimes in Residential Care Homes in South Wales.” Ageing and Society 34 (5): 753–789. DOI:10.1017/S0144686X12001274.

- Ponza, M., et al. 1996. Serving Elders at Risk: The Older Americans Act Nutrition Programs: National Evaluation of the Elderly Nutrition Program, 1993-1995. MATHEMATICA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant.

- Pouyet, V. 2015. Attractivité des aliments et consommation alimentaire chez les personnes âgées selon leur statut cognitif. Thèse de doctorat. Paris: ABIES-AgroParistech.

- Robson, S. K. 2002. “A Review of Psychological and Cultural Effects on Seating Behavior and Their Application to Foodservice Settings.” Journal of Foodservice Business Research 5 (2): 89–107. doi:10.1300/J369v05n02_07.

- Robson, S. K. 2008. “Scenes from a Restaurant: Privacy Regulation in Stressful Situations.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 28 (4): 373–378. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.03.001.

- Rowe, J. W., and R. L. Kahn. 1998. Successful Aging. Random House. New York: Pantheon.

- Sadarangani, T. R., and K. P. Murali. 2018. “Service Use, Participation, Experiences, and Outcomes among Older Adult Immigrants in American Adult Day Service Centers: An Integrative Review of the Literature.” Research in Gerontological Nursing 11 (6): 317–328. doi:10.3928/19404921-20180629-01.

- Savishinsky, J. S. 2003. Bread and Butter” Issues: Food, Conflict, and Control in a Nursing Home. Gray Areas: Ethnographic Encounters with Nursing Home Culture, 103–120. New Mexico: School of American Research Press.

- Sommer, R. 1967. “Classroom Ecology.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 3 (4): 489–503. doi:10.1177/002188636700300404.

- Sydner Mattsson, Y. 2005. “Måltiden mer än ett näringsintag. ÄLDRE i CENTRUM.” 18 (4): 18–20.

- Tellis-Nayak, V. 2007. “A person-centered Workplace: The Foundation for person-centered Caregiving in long-term Care.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 8 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2006.09.009.

- Thompson, G. M. 2010. “Restaurant Profitability Management: The Evolution of Restaurant Revenue Management.” Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 51 (3): 308–322. doi:10.1177/1938965510368653.

- Vucea, V., H. H. Keller, and K. Ducak. 2014. “Interventions for Improving Mealtime Experiences in long-term Care.” Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics 33 (4): 249–324. doi:10.1080/21551197.2014.960339.

- Watkins, R., et al. 2017. “Attitudes, Perceptions and Experiences of Mealtimes among Residents and Staff in Care Homes for Older Adults: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Literature.” Geriatric Nursing 38 (4): 325–333. DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.12.002.

- Whear, R., et al. 2014. “Effectiveness of Mealtime Interventions on Behavior Symptoms of People with Dementia Living in Care Homes: A Systematic Review.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 15 (3): 185–193. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.10.016.

- Wikby, K., and A. Fägerskiöld. 2004. “The Willingness to Eat: An Investigation of Appetite among Elderly People.” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 18 (2): 120–127. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00259.x.

- 野村知子, et al. 1999. “食事サービス環境に関する研究 (2) 会食サービスの実態と効果に関する研究.” 住宅総合研究財団研究年報 (25): 189–200.