ABSTRACT

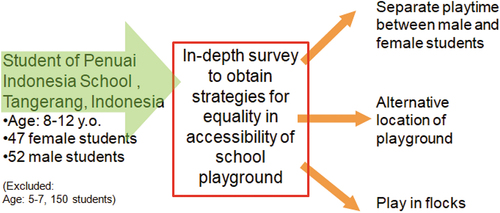

Female marginalization is a common phenomenon, particularly in public spaces, including schools, which should provide equality of rights in space utilization. This research becomes more relevant because the politics in school playgrounds could represent the politics in urban public space, and the way females strategize to deal with it. This study was conducted at Penuai Indonesia School (PIS), a private, mixed-gender school in Tangerang, Indonesia, a country where patriarchal culture is generally the societal norm. This study was conducted using the grounded theory-based qualitative method, and it involved 47 female and 52 male students aged between eleven and twelve years. The data were obtained through questionnaires and deep interviews with female students and management of PIS. This study aims to understand female students’ strategies to overcome male domination (indicated by peers or invisible leaders) in the school playground. In conclusion, to combat male domination and invisible leaders, female students utilize three strategies depending on behavior patterns: they utilize separate playtime, utilize other playgrounds, and play in flocks. Being in flocks was the ideal strategy to cope with the anxiety they experienced; it is an adaptation through adjustment.

1. Introduction

The child-friendly school (CFS) is a concept of a school that recognizes the fundamental needs of children by providing a safe, clean, healthy, and protective environment for them (Fauziati Citation2018). However, the implementation of this kind of environment is not simple, owing to obstacles such as the socioeconomic level of a school, gender of the students, and the grades of the students (Çobanoglu, Ayvaz-Tuncel, and Ordu Citation2018). Several instruments must be improved to enhance the success of CFS, but it is more important to focus on the teachers’ awareness to recognize and understand children and their needs (Weshah, Al-Faori, and Sakal Citation2012; Fitriani and Qodariah Citation2021). An essential need of children that is ignored by the residents of a school is the right to play; during playtime, the marginalization of female students is generally obvious.

For some, especially adults and male students, marginalization is a matter of indifference. However, female students experience it dissimilarly. It is hurtful and interferes with their well-being at school. Naturally, children can play anywhere, and play activities are strategic expressions to reduce stress (Asbury Citation2020; Saragih Citation2021). At school, most play activities occur in the school playground (Larsson and Rönnlund Citation2021). Evidently, gender equality issues on accessibility to school facilities differ by country. Gender equality is practiced more in the Nordic countries, and each school generally promotes gender equality in its own way in every school activity (Heikkilä Citation2020). However, in developing countries, patriarchal culture as the social norm dominates interactions in daily life and massively affects gender equality. In Tehran, female students only can spend their recess talking and socializing with their peers; they do not play games in school playgrounds (Marouf, Che-Ani, and Tawil Citation2016). In South Africa, it was found that hegemonic and masculine performances occur in school facilities among children aged 12–14 years. Males, by culture, are provided the opportunity to manifest their dominance in school playgrounds (Mayeza and Bhana Citation2020). Gender bias was also found in Indian schools, where cultural influences and local values facilitated its occurrence (Thasniya Citation2020). In Bangladesh, ancient traditions and social norms remain valid factors that contribute to gender inequality, resulting in female students facing obstacles to performing active physical activities like sports in schools (Shefali Citation2021).

Patriarchal culture also exists in Asian and African schools. Several studies have found that female students have unequal access to education (Nasir and Lilianti Citation2017) and school playgrounds (Spears Citation2021), which contributes to them being less prosperous. Contestation of space in school playgrounds is an important issue in Indonesia that has the potential to become bullying (Arif and Novrianda Citation2019; Dewi Citation2020), since some schools still do not meet the minimum standard area set by the government (Sinta Citation2019). This is true of most small schools, especially in urban areas, built on a very limited area, especially privately managed schools.

Therefore, this study aims to understand adaptation patterns exhibited by female students in the school playground in response to the marginalization they face in the school playground due to male domination.

1.1. School playground

Architecture is space, the art of organizing and arranging the space (Rapoport Citation2005) with complex and qualitatively distinctive processes (Hirst Citation2005), that sometimes lack a technical solution (Ballantyne Citation2002). Several studies have found that the existence of school playgrounds, as a product of architecture, has become essential, in term of both the physical and nonphysical aspects. While the physical aspects of school playgrounds usually focus on shape, size, equipment, and themes (Jansson Citation2015), the nonphysical aspects, such as gender and bullying (Kilvington and Wood Citation2016; Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014; Reimers and Knapp Citation2017; Spark, Porter, and de Kleyn Citation2019), marginalization and gender equality (Ridgers et al. Citation2011), and loose parts intervention for female students (Snow et al. Citation2019), draw more lively discussions and powerful criticisms. Research suggests that aggressive or bullying behavior often appears in adolescence among peers (Pellegrini Citation2002). The potential triggers for the emergence of aggression and intimidation are facilitated by a patriarchal culture that provides males the opportunity to have a more dominant, superior, and central identity, interest, character, and ability (Boldt Citation2002).

The problems of school playgrounds sometimes originate from politics. School playgrounds are the first arenas in which males and females learn to negotiate their behavior in public (Karsten Citation2003), which plays a role in politics in exercising social influence (Cele and van der Burgt Citation2016). Additionally, this is where conflicts and cultural contestations occur between children (junior and senior) (Cassegård Citation2014). Male and female students behave differently when doing physical activities and in their play behavior (Hallal et al. Citation2012). Power contestation and conflict should not be avoided (Parra, Bakker, and van Liere Citation2021). The domination of space by male students who feel more powerful is common, which causes struggle over power between genders and bullying by older students and/or by older children (Nilsen et al. Citation2019). Female students generally face struggles with power, authority, and influence between genders (Allen Citation2009). However, in the school environment, the roles of parents and teachers are essential. We may choose to subvert “typical” gender roles in our schools (Spears Citation2021). In the social process, adolescents struggle to be accepted by peers, resulting in a behavioral adaptation to receive and understand information and act on the environment with the aim of achieving the satisfaction of needs, which becomes a success determinant of the process. If such a process does not yield satisfaction, maladaptation has occurred (Bennett et al. Citation2017).

1.2. Problem statement

At Penuai Indonesia School (PIS), a contestation of space that has the potential to become bullying, marginalization, and inequality of access to the school playground has been occurring, and it greatly affects the behavior of female students. Evidently, they can deal with these problems. Meanwhile, their response pattern to problems in the school playground, which indicates strategic political adaptation to meet their play needs, is more important. According to Berry’s concept, humans use three types of adaptation strategies when they are in a certain environment: adaptation by reaction, adaptation by adjustment, and adaptation by withdrawal (Berry Citation1986). Based on this, the central problem in this study is to investigate how female students strategize and adapt to deal with marginalization in the school playground despite the existing patriarchal culture dominated by male students.

2. Method

This study was conducted at Penuai Indonesia School (PIS), a private mixed-gender school with about 250 students in primary and lower secondary school. It is located in Medang Lestari housing estate, Tangerang, Indonesia (). Majority of the students are of low-middle socioeconomic status, and most of them are from Bataknese and Javanese tribes. The school is run by a female principal, who leads the teachers (the majority are female teachers) and manages the administration staff, security staff, and other support staff. The school is approximately 1000 m2 in area, smaller than the school standard specified by the existing regulations (minimum 1240 m2). In addition, 70% of the school area is occupied by school building and facilities, while the rest is a limited open space. This has caused the students in the grades in question to claim one of the sports fields as their designated school playground. The research phases were carried out through interviews and questionnaires involving 47 female students and 52 male students aged between eight and twelve years. The rest of the student body (around 150 students) are of five to seven years old, which are too young to be interviewed and therefore are out of scope of this study. According to Glaser and Strauss (Charmaz and Thornberg Citation2021), most grounded theory studies are based on interviews that focus on more detailed questions and sometimes explore questions about aspects not previously anticipated to be important. Comparing and coding the data from interviews and drawing conclusions are an important part of the analysis process of this study.

Figure 1. Location of the school in this study, in (a) Indonesia (scale 1:20.000.000), (b) Banten province, South Tangerang city (next to Jakarta province, scale 1: 200.000), and (c) Penuai Indonesia School (scale 1:400). Source: Google Maps [online] Available through: Bina Nusantara Library http://library.binus.ac.id [Accessed 15 September 2022].

![Figure 1. Location of the school in this study, in (a) Indonesia (scale 1:20.000.000), (b) Banten province, South Tangerang city (next to Jakarta province, scale 1: 200.000), and (c) Penuai Indonesia School (scale 1:400). Source: Google Maps [online] Available through: Bina Nusantara Library http://library.binus.ac.id [Accessed 15 September 2022].](/cms/asset/2d12df96-8aea-4229-906a-06d3e1dc343c/tabe_a_2153061_f0001_oc.jpg)

3. Results

3.1. School playground as a political process

Realizing a school playground requires commitment, particularly in urban areas with limited land. Studies have found that school playgrounds are a result of spatial political processes (Pather and Du Plessis Citation2015), and are configured by power (Hirst Citation2005), as is seen in Penuai Indonesia School (PIS). As a private school, the school foundation has been making efforts to provide a good and comfortable learning environment as one of its strategies to maintain the existence of the school. Playgrounds are important for students’ well-being. Despite the decision process being full of conflicts and contestations between members of the school foundation, the commitment to support students as a stakeholder is always present. To complement children’s play and sports needs in a limited land area, the school foundation has combined the functions of sports and play in the same area – the sports field playground, as shown in .

Figure 2. The sports field as the school playground, (a) as seen from birds eye view, showing that the field is dominated by male students, while (b) female students can just watching at the side of the field, or (c) playing in flocks at other part of the school. (Source: Survey, 2021).

The school foundation’s strategy has been fruitful, and the school playground can meet students’ play needs. The decisions and policies in place have shown that the school principal is in alignment with the goal of all students fulfilling their play needs and preferences:

“ … we realize that children need to play and need to socialize; the students need a school playground … ”

(Management of PIS, 2021)

The school principal actions are in line with the findings of Ndhlovu and Varea (Citation2018), namely, that school principals take into consideration children’s needs and preferences in their policy to improve the designs of playground space.

3.2. Marginalization of female students

Most play activities during school recess are conducted outside of class, in the school playground (Larsson and Rönnlund Citation2021). The data in indicate that 66.7% of the respondents play outside the classroom and 33.3% stay in the classroom or other spaces located around the classroom.

Table 1. Spaces used by male and female students during school recess.

During recess, since the school playground is dominated by male students, female students tend to stay on the side of the school playground or in the classroom. Their preference for the side of the playground or inside the classroom for play activities is believed to be due to the uncomfortable interactions they experience. The data in and the data from in-depth interviews indicate this reality. Most female students feel uncomfortable because of disruptions from other students (from male students, as indicated by the interviews). shows that 51% of the 47 female respondents claim to experience disruptions occasionally, while 43% claim to experience them constantly.

Table 2. Female students’ view on the school playground during recess.

Furthermore, some of the female students’ statements indicate that they feel uncomfortable because of disruptions on the playground during recess/break time, such as male students yelling, confirming the existence of arrogance in communication, and an attitude that restrict opportunities and access for female students to play in the school playground:

“ … get out of the way … likes to annoy other people … ”

“ … go away and move to the side … being threatened … don’t get too close … ”

(Female student at PIS, number 10, Primary 6, 2021)

The domination of male students in the school playground is in line with the findings of several other studies: boys, older children, and highly active children benefit more from this environment than girls (Nilsen et al. Citation2019). Moreover, playgrounds seem to be a place for boys (Reimers et al. Citation2018), and female physical activities are suppressed when males are present in the playground (Mayeza Citation2017). Preference toward playing with the same gender is consistent with the findings of several studies wherein more children preferred same-sex playmates (Johnson, Christie, and Wardle Citation2005). At PIS, the disruptions on the playground are real and felt by female students, regardless of whether physical or emotional. The data prove it. Male students’ behavior causes female students to experience unhappiness, discomfort, unequal access to the facilities, limitations, and restrictions, which indicates the occurrence of marginalization.

3.3. School playground management

Male students tend to dominate (Mayeza Citation2017; Swain Citation2005; Zhang Citation2010), and it occurs at PIS. As female students face inequality in terms of access, limitations, and restrictions in the school playground, they hope for the school authorities to devise a strategy to minimize it. The school principal stated that the disruptions would subside as she pursues strategies to make the playground a safe and comfortable environment for all, such as establishing a clear recess schedule and ensuring recess is supervised by teachers around the playground.

“ … set a specific schedule for use of the school playground, and [ensure the playground is] supervised by teachers … ”

(Management of PIS, 2021)

Despite steps like scheduled and supervised recess, the data in indicate that disruptions still occur, where 94% of the female respondents experienced them occasionally or constantly. As shown in , 10.1% of the students, feel that the school playground is controlled by a group of students (peers) causing unequal access, and limiting and restricting behavior, which is in line with Ndhlovu and Varea (Citation2018). Thus, the use of the space by the rest of the students is constrained, regardless of the fact that 89.9% of the students stated that the school playground is supervised by the teachers and the principal. It is possible for some groups of male students to dominate the play space. Although few, they scream to potentially agitate female students, as suggested by the interviews with female students. The recess schedule and supervision by the teachers do not fully guarantee fairness in the use of the school playground. As the number of teachers and time they can allocate to supervision are limited, they cannot always be on the school playground. This condition serves as an opportunity for certain peers to exercise domination, limitations, and restrictions. The recess schedule is ineffective without intense supervision, which potentially leads to unequal access to the school playground for the female students, except those with authority that dominate the space, as may also happen in other public spaces.

Table 3. Students’ perspective on the supervision of the school playground.

3.4. Patriarchal culture in the school playground

Unequal access to the facility, limiting effort, and restrictions, as the interviews with female students under subchapter 3.2 indicate, suggest the clear occurrence of marginalization. In addition, the female students also experience unfairness and anxiety apart from physical disturbances, as illustrated by their concerns shown below.

“ … resentful, emotional, angry, indignant … perceived by the female students … ”

(Female student at PIS, number 17, Primary 5, 2021)

Subchapter 3.3 recapitulates that the domination of space by peers or male students is obvious, especially when supervision by the teachers is not conducted as it should be. Prioritization of male students over female students proves that patriarchal culture exists in the school playground at PIS. confirms that 10.1% of the students think that certain peers have more dominance and are more aggressive. Their presence is felt by the female students even though it is not detected by the teachers. They are regarded as the “ … invisible leaders,” and their disturbing behavior is felt and is possibly occurring because of superior play skills (Smith Citation1994), greater physical strength, seniority (Olweus Citation1993), or connections with the school management. reveals the feelings experienced by female students:

Table 4. The experiences of female students related to students who can use the playground.

This finding substantiates that older students or students with expertise and status could exercise power like invisible leaders, which is in line with the findings of Malen (Citation2006). Two requirements must be met for power to be exercised. First, the actors must have resources valuable to others. Second, the actors must have the ability and desire to strategically leverage those resources to direct, constrain, or manipulate others. Although invisible leaders exist, it seems that not all female students accept these conditions and therefore refuse them. Swain (Citation2005) found that more females refused to be dominated by males and some were able to exercise power over them deliberately. Some (1) adjust and demonstrate their capabilities (Spark, Porter, and de Kleyn Citation2019), while some (2) resist the uncomfortable conditions, as stated by the female students below.

“ … we argued … we do not disturb you playing … ”

(Female student at PIS, number 25, Primary 6, 2021)

This indicates that less supervision and exercise of power by the teachers will promote the emergence of new powers. There are students who will likely turn into invisible leaders in the school playground. Their presence is highly regarded as a threat by the minority, female students, and other students who are weak and less skillful, and thus, would be counterproductive to the realization of a fair and gender-equal school playground.

4. Discussion

As a product of architecture, school playgrounds are mostly designed, constructed, and managed according to adult expectations, and they dictate what children should do in these spaces (Skelton Citation2009). This is sometimes unfavorable to female students (Paechter and Clark Citation2007) because of lack of play equipment and game availability (Massey et al. Citation2020). confirm a discrepancy between the school principal’s expectations and the behavioral inconvenience experienced by female students. Subchapter 3.2 provides an explanation of the existence of restrictions that indicate the occurrence of marginalization. The existence of invisible leaders (subchapter 3.4) in the school playground is more obvious, and patriarchal culture is factual. Their play behavior is allegedly the cause of the problems experienced by female students. Regardless, as a part of the school community, female students must fight for equality in the right to use the school playground during the limited recess at school. The unpleasant behavior experienced by female students has an impact on their strategy of using school playgrounds as a means of playing during recess. Subchapter 3.4 attests that female students tend to avoid conflict. Often, they are less likely to go to the playgrounds than male students are just to avoid those students (Brown et al. Citation2008). However, research at PIS reveals a different reality; even though there are restrictions imposed by peers, they still struggle to have the same opportunities to play in the school playground.

substantiates the existence of two controlling forces in the school playground: teachers and peers. From the interviews with female students based on their experience of interacting with the actors, it can be concluded that the roles of actors can be grouped into dominant and moderate. The dominant roles are generated if the behavior of the actor is very active, directly involved in the process that is carried out to control the playground directly. Meanwhile, the moderate role is represented by the behavior of actors that tend to be indirectly involved. In this role, there is room for compromises/discussions. Facts prove that each actor can assume a dominant or moderate role depending on the situation and conditions. Teachers can be dominant or moderate, as can peers. explain the role of each actor by referring to each statement:

Table 5. Teachers’ role.

Table 6. Peers (Invisible leader) position.

The statements regarding each of the actors are a determinant for the response pattern of female students during recess, the time when discrimination and marginalization are potentially perceived by them at school. shows their expectations regarding the school playground.

Table 7. Female students’ expectations regarding the school playground.

The main challenges at PIS are marginalization and unequal access to school facilities, limitations and restrictions, and potential gender conflict and bullying (Mulryan-Kyne Citation2014; Reimers and Knapp Citation2017; Reimers et al. Citation2018). shows that 15.2% of the female students tend to opt for separate play times for optimal use of the school playground. Some others feel that there is a need for more supervision from the teachers to mitigate the problem. They believe strict supervision will be more effective, as teachers can become the more dominant leaders needed by students in the school playground. With a schedule determined and controlled by the teachers, the arrangement for the use of the school playground is expected to be more orderly.

Meanwhile, some female students expect to experience different interactions with peers. Around 48.5% believe that marginalization dominated by certain peers in the school playground can potentially be controlled with dialogue and negotiation between teachers, peers, and female students. When dialogue and negotiation occur, the opportunity for female students to play in the school playground at the same time can be realized. “ … asked [them] for permission first […] just to play soccer in the school playground … ” (Female students at PIS, 2021). The activity of students playing together can occur even when the teacher’s role shifts from that of the dominant actor to that of a moderate actor and there is a constructive dialogue between female students and peers. Peers serve a moderate role, and negotiations become important, which is in accordance with research findings by Parra, Bakker, and van Liere (Citation2021).

Based on the experience of interacting with peers, 36.4% of the female students tended to opt for a separate playground. From their experience, peers can become very dominant at certain times and tend to dominate the school playground, as illustrated by the following statement: “ … go away … instead of making a fuss … ”. (Female students at PIS, 2021). This leads to the school management responding with fairer distribution of the school playground between male and female students, with space zoning. Zoning can clearly encapsulate or divide the school playground into several designated areas with boundaries, such as tables and fences (Barnas, Wunder, and Ball Citation2018). However, according to PIS, zoning can be applied if the school playground area is spacious, and while encapsulation is effective enough to reduce bullying due to age differences, it is not as effective for bullying within the same age group. Therefore, when invisible leaders among peers become the dominant actors and zoning cannot be applied, female students tend to withdraw from the school playground to continue their play activities in other areas, such as canteens, school corridors, or classrooms. The phenomenon of students playing in the periphery of the school playground is proof of this case. Female students can only watch while sitting, chatting, or playing hide-and-seek.

The responses of the female students clarify that marginalization experienced will result in a pattern of adaptation. This pattern is part of the political process carried out by students, and it is highly dependent on the attitudes and behavior of the actors. Most female students prefer to continue playing together, through discussions and negotiations. Negotiation is part of politics, the process of bargaining to reach an agreement with the other party through an interactive process. In the case of PIS, negotiations between senior and junior students, skillful and less skillful students, and the dominating groups and the minorities are crucial. shows the pattern of adaptation that occurs.

Table 8. Students’ play adaptation.

The phenomenon occurring at PIS is real evidence that the application of CFS is not simple, especially when related to the gender culture that is still a stigma strongly connected to the country in which the school is located. Female students need specially formulated strategies to assist them to achieve a CFS.

5. Conclusions

The research conducted at PIS indicates the marginalization of female students. Nevertheless, it cannot fully demonstrate the theory of power, because the research was carried out in only one school, with limited research time. The novelty of this study is the presence of certain peers as invisible leaders and dominant actors (with three trigger factors) sometimes defeating the presence of teachers, which has become the main issue at PIS’s school playground and has affected female students in their decision making to play during recess. The research conducted in this study (using the grounded theory method involving male and female students through interviews and questionnaires) strongly supports the implementation of these strategies:

1. Separate playtimes can be utilized when some female students who resist being dominated by male students can deliberately exercise power over them. It has been proven that female students prefer to divide zoning or divide time for play, which is also the case at PIS.

2. Other playgrounds can be utilized to avoid situations in which the influence of certain peers as invisible leaders and dominant actors affects the students, resulting in the needs of some students not being met. The interviews and observations prove that those who lose in the space contestation tend to switch to using another space as a playground.

3. Playing in flocks could be a viable option in the presence of a patriarchal culture that places male over female students in the school playground, which causes most female students to prefer to initiate dialogue or negotiation with their peers. It indicates that even students need a political process requiring communication skills.

In brief, to increase the clarity, this study can be represented with simple schematic in .

In addition to the aforementioned strategies, it is noteworthy that when supervision by teachers weakens, negotiations with peers are required because this strategy provides an opportunity for them to play together. The ideal strategy for female students’ adaptation to their marginalization is to share spaces between both male and female students. In harmony with Berry’s theory, what was done is an adaptation by adjustment, which can also be a model strategy for females in urban public spaces. This strategy is essential to realize and achieve a CFS, a school with equality in accessibility, as a safe, clean, healthy, and protective environment for children. This study proves that limited school land has an impact on student welfare. Therefore, the standards that have been determined should be an important factor in granting a school permit.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express special thanks for Bina Nusantara University for research funding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

J.F. Bobby Saragih

J.F. Bobby Saragih, M.Si is a faculty member of Architecture Department, Faculty of Engineering, Bina Nusantara University. His research interest is cultural, environment and urban context & architectural design. Currently he is serving as the Dean of Faculty of Engineering, Bina Nusantara University. He is an alumnus of Sebelas Maret University and University of Indonesia.

T. Yoyok Wahyu Subroto

T. Yoyok Wahyu Subroto, M.Eng., Ph.D is a professor at Faculty of Engineering, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia. His area of expertise is built environment and design/ space, human and culture/ architecture. He is an alumni of Architecture Department, Gadjah Mada University (undergraduate), Indonesia and Environmental Engineering Department, Osaka University, Japan (masters and doctoral).

References

- Allen, J. 2009. “Three Spaces of Power: Territory, Networks, Plus a Topological Twist in the Tale of Domination and Authority.” Journal of Power 2 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1080/17540290903064267.

- Arif, Y., and D. Novrianda. 2019. “Perilaku Bullying Fisik Dan Lokasi Kejadian Pada Siswa Sekolah Dasar (Behaviour of Physical Bullying and Location of the Event to Elementary School Students).” Jurnal Kesehatan Medika Saintika 10 (1): 135–143. doi:10.30633/jkms.v10i1.317.

- Asbury, G. C. 2020. “Effects of a Physical Activity Intervention on the Stress Reduction of Underserved Adolescent Youth.” Senior Theses, University of South Carolina, Columbia. ( 390)

- Ballantyne, A. 2002. What Is Architecture? 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Barnas, J., C. Wunder II, and S. Ball. 2018. “In the Zone: An Investigation into Physical Activity during Recess on Traditional versus Zoned Playgrounds.” Physical Educator 75 (1): 116–137. doi:10.18666/TPE-2018-V75-I1-7594.

- Bennett, E. V., L. H. Clarke, K. C. Kowalski, and P. R. E. Crocker. 2017. “From Pleasure and Pride to the Fear of Decline: Exploring the Emotions in Older Women’s Physical Activity Narratives.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 33: 113–122. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.08.012.

- Berry, J. W. 1986. The Acculturation Process and Refugee Behavior Refugee Mental Health in Resettlement Countries, 25–37. Vol. 10. Washington DC: Hemisphere Publ. Co.

- Boldt, G. M. 2002. “Toward a Reconceptualization of Gender and Power in an Elementary Classroom.” Current Issues in Comparative Education 5 (1): 7–23.

- Brown, B., R. Mackett, Y. Gong, K. Kitazawa, and J. Paskins. 2008. “Gender Differences in Children’s Pathways to Independent Mobility.” Children’s Geographies 6 (4): 385–401. doi:10.1080/14733280802338080.

- Cassegård, C. 2014. “Contestation and Bracketing: The Relation between Public Space and the Public Sphere.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32 (4): 689–703. doi:10.1068/d13011p.

- Cele, S., and D. van der Burgt. 2016. “Children’s Embodied Politics of Exclusion and Belonging in Public Space.” In Politics, Citizenship and Rights, edited by K. P. Kallio, S. Mills, and T. Skelton, 189–205. Singapore: Springer.

- Charmaz, K., and R. Thornberg. 2021. “The Pursuit of Quality in Grounded Theory.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 305–327. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357.

- Çobanoglu, F., Z. Ayvaz-Tuncel, and A. Ordu. 2018. “Child-Friendly Schools: An Assessment of Secondary Schools.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 6 (3): 466–477. doi:10.13189/ujer.2018.060313.

- Dewi, P. Y. A. 2020. “Perilaku School Bullying Pada Siswa Sekolah Dasar (Behaviour of School Bullying to Elementary School Students).” Edukasi: Jurnal Pendidikan Dasar 1 (1): 39–48. doi:10.55115/edukasi.v1i1.526.

- Fauziati, E. 2018. “UNCRC, Child Friendly School, and Quality Education: Three Concepts One Goal. The 2nd.” International Conference on Child-Friendly Education (ICCE) Surakarta, Indonesia.

- Fitriani, S., and L. Qodariah. 2021. “A Child-Friendly School: How the School Implements the Model.” International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education 10 (1): 273–284.

- Hallal, P. C., L. B. Andersen, F. C. Bull, R. Guthold, W. Haskell, and U. Ekelund. 2012. “Global Physical Activity Levels: Surveillance Progress, Pitfalls, and Prospects.” Lancet 380 (9838): 247–257. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1.

- Heikkilä, M. 2020. “Gender Equality Work in Preschools and Early Childhood Education Settings in the Nordic countries—an Empirically Based Illustration.” Palgrave Communications 6 (1): 75. doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0459-7.

- Hirst, P. 2005. Space and Power: Politics, War and Architecture. 1st ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Jansson, M. 2015. “Children’s Perspectives on Playground Use as Basis for Children’s Participation in Local Play Space Management.” Local Environment 20 (2): 165–179. doi:10.1080/13549839.2013.857646.

- Johnson, J. E., J. Christie, and F. Wardle. 2005. Play, Development and Early Education. Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Karsten, L. 2003. “Children’s Use of Public Space: The Gendered World of the Playground.” Childhood 10 (4): 457–473. doi:10.1177/0907568203104005.

- Kilvington, J., and A. Wood. 2016. Gender, Sex and Children’s Play. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Larsson, A., and M. Rönnlund. 2021. “The Spatial Practice of the Schoolyard. A Comparison between Swedish and French Teachers’ and Principals’ Perceptions of Educational Outdoor Spaces.” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 21 (2): 139–150. doi:10.1080/14729679.2020.1755704.

- Malen, B. 2006. “Revisiting Policy Implementation as a Political Phenomenon: The Case of Reconstitution Policies.” In New Directions in Education Policy Implementation: Confronting Complexity, edited by M. I. Honig, 83–104. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Marouf, N., A. I. Che-Ani, and N. Tawil. 2016. “Examining Physical Activity and Play Behavior Preferences between First Graders and Last Graders in Primary School Children in Tehran.” Asian Social Science 12 (1): 17–23. doi:10.5539/ass.v12n1p17.

- Massey, W. V., N. L. Deanna Perez, J. Thalken, and A. Szarabajko. 2020. “Observations from the Playground: Common Problems and Potential Solutions for school-based Recess.” Health Education Journal 80 (3): 313–326. doi:10.1177/0017896920973691.

- Mayeza, E. 2017. “‘Girls Don’t Play Soccer’: Children Policing Gender on the Playground in a Township Primary School in South Africa.” Gender and Education 29 (4): 476–494. doi:10.1080/09540253.2016.1187262.

- Mayeza, E., and D. Bhana. 2020. “How “Real Boys” Construct Heterosexuality on the Primary School Playground.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 34 (2): 267–276. doi:10.1080/02568543.2019.1675825.

- Mulryan-Kyne, C. 2014. “The School Playground Experience: Opportunities and Challenges for Children and School Staff.” Educational Studies 40 (4): 377–395. doi:10.1080/03055698.2014.930337.

- Nasir, N., and L. Lilianti. 2017. “Persamaan Hak: Partisipasi Wanita Dalam Pendidikan (Equality of Rights: Women’s Participation in Education).” Didaktis: Jurnal Pendidikan Dan Ilmu Pengetahuan 17 (1): 36–46.

- Ndhlovu, S., and V. Varea. 2018. “Primary School Playgrounds as Spaces of inclusion/exclusion in New South Wales, Australia.” Education 3-13 46 (5): 494–505. doi:10.1080/03004279.2016.1273251.

- Nilsen, A. K. O., S. A. Anderssen, G. K. Resaland, K. Johannessen, E. Ylvisaaker, and E. Aadland. 2019. “Boys, Older Children, and Highly Active Children Benefit Most from the Preschool Arena regarding moderate-to-vigorous Physical Activity: A cross-sectional Study of Norwegian Preschoolers.” Preventive Medicine Reports 14: 100837. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100837.

- Olweus, D. 1993. “Bullies on the Playground: The Role of Victimization.” In Children on Playgrounds: Research Perspectives and Applications, edited by C. H. Hart, 85–128. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Paechter, C., and S. Clark. 2007. “Learning Gender in Primary School Playgrounds: Findings from the Tomboy Identities Study.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 15 (3): 317–331. doi:10.1080/14681360701602224.

- Parra, S. L., C. Bakker, and L. van Liere. 2021. “Practicing Democracy in the Playground: Turning Political Conflict into Educational Friction.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 53 (1): 32–46. doi:10.1080/00220272.2020.1838615.

- Pather, M. R., and P. Du Plessis 2015. “Is the School a Playground for Politics? ” Paper presented at the 8th Annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain.

- Pellegrini, A. D. 2002. “Bullying, Victimization, and Sexual Harassment during the Transition to Middle School.” Educational Psychologist 37 (3): 151–163. doi:10.1207/S15326985EP3703_2.

- Rapoport, A. 2005. Culture, Architecture, and Design. Chicago: Locke Science Publishing Company, .

- Reimers, A. K., and G. Knapp. 2017. “Playground Usage and Physical Activity Levels of Children Based on Playground Spatial Features.” Journal of Public Health 25 (6): 661–669. doi:10.1007/s10389-017-0828-x.

- Reimers, A. K., S. Schoeppe, Y. Demetriou, and G. Knapp. 2018. “Physical Activity and Outdoor Play of Children in Public Playgrounds—Do Gender and Social Environment Matter?” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (7): 1356. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071356.

- Ridgers, N. D., L. M. Carter, G. Stratton, and T. L. McKenzie. 2011. “Examining Children’s Physical Activity and Play Behaviors during School Playtime over Time.” Health Education Research 26 (4): 586–595. doi:10.1093/her/cyr014.

- Saragih, J. F. B. 2021. ““The Space Wider, I Can Play Ball … ”: When Children Thinking about Space.“ IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 794(1): 012232. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/794/1/012232.

- Shefali, M. K. 2021. “Bangladesh Women and Sport.” In Women and Sport in Asia, edited by R. L. De D’Amico, M. K. Jahromi, and M. L. M. Guinto, 25–34. New York: Routledge .

- Sinta, I. M. 2019. “Manajemen Sarana Dan Prasarana (Management of Infrastructure and Facilities).” Jurnal Isema: Islamic Educational Management 4 (1): 77–92. doi:10.15575/isema.v4i1.5645.

- Skelton, T. 2009. “Children’s Geographies/Geographies of Children: Play, Work, Mobilities and Migration.” Geography Compass 3 (4): 1430–1448. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00240.x.

- Smith, P. K. 1994. “What Children Learn from Playtime, and What Adults Can Learn from It.” In Breaktime and the School: Understanding and Changing Playground Behaviour, edited by P. Blatchford and S. Sharp, 36–48. London: Routledge.

- Snow, D., A. Bundy, P. Tranter, S. Wyver, G. Naughton, J. Ragen, Engelen, L. 2019. “Girls’ Perspectives on the Ideal School Playground Experience: An Exploratory Study of Four Australian Primary Schools.” Children’s Geographies 17 (2): 148–161. doi:10.1080/14733285.2018.1463430.

- Spark, C., L. Porter, and L. De Kleyn. 2019. “‘We’re Not Very Good at Soccer’: Gender, Space and Competence in a Victorian Primary School.” Children’s Geographies 17 (2): 190–203. doi:10.1080/14733285.2018.1479513.

- Spears, G. K. 2021. “Breaking the Gender Binary: Using Fairytales to Transform Playground Possibilities for Year 3 Girls.” Education 3-13 49 (6): 674–687. doi:10.1080/03004279.2020.1767673.

- Swain, J. 2005. “Sharing the Same World: Boys’ Relations with Girls during Their Last Year of Primary School.” Gender and Education 17 (1): 75–91. doi:10.1080/0954025042000301311.

- Thasniya, K. T. 2020. Gender Bias in School Education Handbook of Research on New Dimensions of Gender Mainstreaming and Women Empowerment, 54–70. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Weshah, H., O. Al-Faori, and R. Sakal. 2012. “Child-Friendly School Initiative in Jordan: A Sharing Experience.” College Student Journal 46 (4): 699–715.

- Zhang, H. 2010. Who Dominates the Class, Boys or Girls?: A Study on Gender Differences in English Classroom Talk in A Swedish Upper Secondary School. Kristianstad, Sweden: Kristianstad University.