ABSTRACT

This article examines the nature of urbanism in British concessions in China from the mid-nineteenth century to the present by investigating the evolution of Tianjin’s Victoria Park, the centre of the largest British concession in China. While existing works often subsume the urban development of concessions under the hegemony of British arrivals, this research explores how residents of the British concession and locals in Tianjin interacted to frame their urbanism, contributing to our understanding of the urban formation of the British concession in China and beyond. It reveals that initially Victoria Park was primarily a place of entertainment, and then, through interaction between the local Chinese and British residents, evolved firstly into the very symbol of British pride in the concession; then into a neglected pocket of parkland – representing the dark side of British settlers; and finally, into an important part of the precious heritage of the city.

Attracted by a vast potential market, many-nineteenth century Britons left their homes and travelled by ship halfway around the globe to the ancient empire of China. However, since the latter part of the eighteenth century, the Chinese government had adopted measures to strictly control and restrict foreign trade, and so the new arrivals were confronted by a “gated community”. In response, Britain militarily defeated China in the First Opium War (1839–1842), and forced China to open foreign trade ports and provide safeguards for foreign merchants through the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. Consequently, in 1845 Britain founded the first foreign concession in China, in Shanghai, and subsequently established six other concessions along the Yangtze River and the east coast during the second half of the nineteenth century. As urban development under the British arrivals was based on their own tastes, traditions, and social practices, the concessions became a locus where British planning ideas encountered Chinese society.

Scholars have been drawing increasing attention to the urbanism of the British concessions in China, carefully studying their administrative system, infrastructure, urban culture, and architectural forms. For example, Jackson explored the urban governance of the British-dominated International Settlement of Shanghai (Jackson Citation2017). Liu Studied the water supplied system in the British Concession of Tianjin (Haiyan Citation2011). Chen examined the bund making in the British Concession of Xiamen (Chen Citation2008). However, given that the British arrivals used force to gain the privilege of founding concessions, the existing works too often subsume the development of the British concessions under the hegemony of British arrivals (Denison and Ren Citation2006; Editing Committee of The Concessions of Powers in China Citation1992; Zhou Citation2009). They neglect to acknowledge that British concessions were not formal British colonies fully under the rule of metropolitan states, such as Hong Kong and in the British Raj. Rather, British concessions were Chinese territories administered by British settlers, resulting in a conflict between the British administration of those settlers and the territorial sovereignty that the Chinese government exercised. Hence, instead of remaining isolated from each other, the British concessions and Chinese towns in the treaty ports evolved under each other’s influence. In contrast to the notion of British arrivals dictating their own terms to the Chinese communities, the residents of Chinese towns and British concessions formed an interrelated and interactive relationship which influenced the urban construction of each entity.

This article intends to contribute to understanding the urban formation of British concessions in China by examining the evolution of Victoria Park, an important built environment in the centre of the largest and the most developed British concession in China, from the mid-19th century, when it was founded, to the present. As urban space, parks are shaped by social, economic, political, and psychological processes and represent these forces in their location, size, shape, composition, and equipment and landscaping (Cranz Citation1982). Hence, rather than viewing Victoria Park as a simple aesthetic green area, that the current scholarship focuses on, this article treats the park as an integral part of urban development in relation to the evolving society of the British concession (Zhang Citation2010; Sun, Aoki, and Zhang Citation2012). This article will, through examining the temporal evolvement of Victoria Park, determine how the residents of the British concession and the locals of Tianjin interacted with each other to shape the urbanism of the concession over the course of urban development of the concession. In doing so, this article will contribute to understanding other British colonial and postcolonial projects in China and beyond, as well as shed light on the contemporary urban development and renewal strategies of the built environments of China’s historical concessions.

1. A place of entertainment for British arrivals, 1887-1900

Two hundred kilometres away from China’s capital Beijing, Tianjin is well known as China’s largest industrial and commercial centre after Shanghai, as well as the city which housed the largest number of foreign concessions in modern China – Britain, France, the United States, and another six nations founded concessions in Tianjin. Since the fifteenth century, Tianjin was a harbour town for rice and salt transportation. The turning point in its urban history came in 1860 when the Chinese and British governments signed the Convention of Peking after China’s defeat in the Second Opium War (1856–1860) (Haiyan Citation2006, 38). As this Convention granted rights to “British subjects to reside and trade”, the British arrivals immediately founded the concession in this city, and thus Tianjin’s urban development was launched on a voyage which led it to become a modern metropolis (Convention of Peking Citation1860, 432).

When the first British arrivals landed in Tianjin, the site of the concession was undeveloped land. This provided a blank slate for British planning ideas on the urban development of the concession. Through the hard work of the arrivals, the first chamber of commerce, newspaper, and literary society successively emerged in this hub city during the 1870s. Thereafter, the British concession apparently thrived. A witness stated that pedestrians “surged back and forth, the traffic streamed endlessly, so that no other metropolis could match it” (Rasmussen Citation1925, 26).

Consequently, this called for the creation of a significant urban space – a public park. The year 1887 was the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria, and the British Municipal Council (BMC) decided to develop a public park to celebrate this event (Rasmussen Citation1925, 63). Officially inaugurated on 21 July 1887, the park occupied 1.23 hectares and was surrounded by Victoria Road (East), Pao Shun Road (North), Meadows Road (South) and Consular Road (West) (Zhang Citation2010, 44). In order to create a memorial for the great queen, the council named this first public park of the British concession Victoria Park. Chinese commoners referred to it as the “British Park” (Tianjin General Annals Editing Committee Citation1996b, 311).

Although developed by British arrivals, the park was influenced by the Chinese environment, and thereby formed a hybrid landscape. () It employed a classical European regular layout: a bandstand was situated at the centre of the park, while four paths connected the centre to the four corners and divided the park into four quarters. Lawn, the distinguishing characteristic of English gardens, made up the main component of this park (Zhang, Wei, and Keqin Citation1982, 158). Nevertheless, the bandstand employed the style of an authentic Chinese pavilion. With a hexagonal tented roof topping six columns, its structure was similar to the traditional Liujiaozanjian Pavilion. Also, the plants in the park were selected from the local flora, such as Chinese Pines (Pinus tabulaeformis Carr.), Midget Crabapples (Malus micromalus Mak.), and Chinese Scholar Trees (Sophora japonica L.) (Zhang Citation2012, 45).

Surrounded by Chinese circumstances, the British arrivals sought to enrich their lives by introducing popular British entertainment activities into the park. Thus, the park became a centre of entertainment in the concession. For example, the residents founded a band – the first one in China – typical of the enthusiasts of that time, to perform in the park. This band rehearsed and played in the central bandstand, adding to the unique and attractive landscape (McLeish Citation1914, 5). Also, the British arrivals established tennis courts in the park in the 1880s, and founded a tennis club, named the “Ladies” Lawn Tennis Club’ in 1889 (Yancevetsky Citation1983, 37).

Given the hybrid designed landscapes and favoured outdoor activities, the park was praised as “a good illustration of what care and skill can do towards beautifying the treeless, marshy, and alkaline plains about Tientsin [Tianjin]” (Drake Citation1900, 3). This, consequently, motivated the British residents to construct a two-storey hall in the extended enclosure of the park in 1890. Being the largest building in Tianjin in the nineteenth century, it was named Gordon Hall, in honour of Charles George Gordon (1833–1885), a British army officer and administrator, and a founder of British concessions (McLeish Citation1914, 10). Officially, Gordon Hall was the town hall of the concession, however it also served as a large-scale entertainment centre. It had a well-furnished public library, which included several thousand books and a large number of the leading magazines and journals from Europe and America (Drake Citation1900, 3). Here also, a large entertainment hall served for social functions, balls and theatrical amusements (Astor House Hotel. Ltd. Citation1904, 6). Even the towers of the hall were interesting sites, which provided viewing platforms to get a bird’s eye view of the suburbs, attracting large numbers of people (McLeish Citation1914, 2). Thus, Victoria Park with Gordon Hall within its boundaries, became the major entertainment place for the residents of the British concession.

2. The heart of the British concession, 1900-1941

The turn of the twentieth century witnessed the rise of anti-colonial struggles in Tianjin. In response to the western invasion in the second half of the 19th century, beginning in 1899 unemployed village men in North China undertook what became known as the Boxer Rebellion, an anti-foreigner and anti-Christian movement (Cohen Citation1997, 114). In 1900, this rebellion spread to Tianjin and the Boxers massacred European settlers and seriously damaged the British concession, demolishing infrastructure and burning Christian churches (Luo Citation1993, 302–3).

In response, the British residents tried to reinforce and strengthen their position in Tianjin. On the one hand, the BMC took advantage of the situation, asking the Chinese government to expand the British concession as compensation (Rogaski Citation2004, 187). In 1897, they extended their concession by 660 hectares from its original area of 186 hectares. In 1902, the 53 hectares of the American concession was incorporated, and with further expansion in 1903, the British enlarged the area by a further 1590 hectares, so that it occupied a total of 2489 hectares, becoming the largest independent British concession in China (Tianjin General Annals Editing Committee Citation1996b, 72). On the other hand, although the British residents in Tianjin were already loosely bound together in the early part of the concession days, the uprising drove them to form a more cohesive collective centred on British identity, which ultimately led to the British state’s formal entry into the private sphere of these residents’ lives by forging direct relations between individual Britons and the British government (Bickers Citation1999, 68).

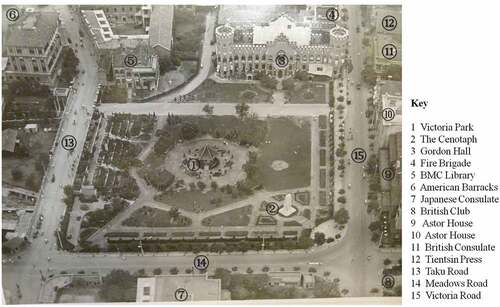

Both the territorial extension and this cohesive, collective British identity called for a central rallying point in the British concession. As Gordon Hall served as the seat of the BMC, which administered affairs both in the area of the initial concession and areas of the new expansions, Victoria Park became the centre of the concession. More and more commercial and official buildings appeared around the park. These included the main official buildings of the concession, such as the British Municipal Council Library, which moved from inside Gordon Hall to a three-story building on the northwest side of Victoria Park, the British Consulate, the British Municipal Council Fire Station, and the American Barracks. Entertainment venues, like Astor House, the earliest and most luxurious hotel, and the British Club, the most fashionable amusement place in the British concession; and cultural institutions, like the Tientsin Press, which published the Peking and Tientsin Times, were also founded near Victoria Park. All the most influential governmental, official, and cultural buildings formed the administrative centre of the British concession, with Victoria Park located at its heart. ()

Figure 2. Plan of Victoria Park and the main buildings around it, bird’s-eye view from the south in 1928. (Source: drawn by author, referenced aerial pictures of Tianjin, 1928, provided by Brussels, general state archives (Archives Générales du Royaume/Algemeen Rijksarchief), Crédit Foncier d’Extrême-Orient, 131.).

The British residents engaged to frame Victoria Park as a British space. Situated within a Chinese world, excluding the Chinese from the park became the most direct path to achieve this aim. In July 1895, a reader using the pseudonym “Whiteman”, proclaimed in the Peking and Tientsin Times, the leading daily English newspaper of Northern China:

Let us try and preserve as much as possible this extremely small spot of Western civilization from being inundated by the ever encroaching Chinese. It is a matter which should be seriously taken up by the Municipality. The Council is charged with the safeguard of the interests of those who contribute to the expense of maintaining our little haven of green, and not of those who would, if allowed, speedily destroy it’ (Whiteman Citation1895, 280).

Another reader, with the pseudonym “Another Mother”, expressed her concerns regarding the security of children by claiming that “if the Chinese, male and female (presumably not of the upper classes) be allowed to overrun the Park as at present, I also shall be unable to allow my little girls to go there” (Another Mother Citation1895, 280). Under pressure from the residents, the BMC issued an announcement in August 1895 requiring all Chinese persons to get a ticket from the British Municipal Council one day before they entered the park, and that Chinese were not permitted to enter the park after five o’clock in the afternoon (Sun, Aoki, and Zhang Citation2012, 38).

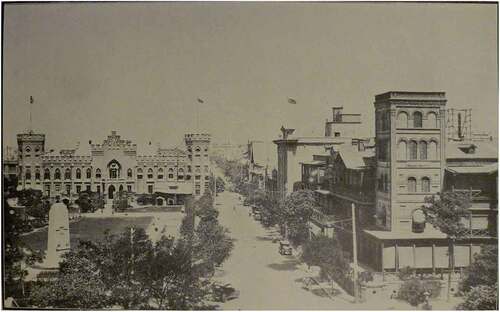

Moreover, the residents further reinforced the Britishness of this park through the constructions within it. For example, in 1921, the British residents decided to construct a cenotaph to commemorate the Allies’ victory in the Great War and the signing of the treaty of Versailles in 1919. () Similar to cenotaphs constructed in London and other British overseas cities, such as Hong Kong, Toronto, and Auckland, this cenotaph was five metres high, and engraved with a soldier holding a sword and the inscriptions, “Glorious Dead” and “MCMXIV-MCMXIX”.Footnote1 As it was located on the southeast corner of Victoria Park, it became the visual focus of the juncture of Victoria Road and Meadows Road, a prominent reminder of the British spirit.

Figure 3. The cenotaph and Victoria Park. (Source: Tientsin, North China. The port, its history, and rotary club activities (Tientsin: rotary club of tientsin, 1934), unpaged, provided by Brussels, general state archives (Archives Générales du Royaume/Algemeen Rijksarchief), Crédit Foncier d’Extrême-Orient, 139.).

While celebrating Britishness, Victoria Park entered its golden age of construction. An article in the Takung Pao Newspaper, an influential Chinese newspaper in modern China, praised it as “the cleanest and tidiest park among all the public parks of foreign concessions in Tianjin” Tianjin Public Park (Four) – British Park Citation1931, 9).Footnote2 Descriptions of the park reported canna herb flowers growing amongst the lawn which beautified the park. In the flowerbeds along the street, a variety of exotic and strangely scented flowers were “blooming in profusion, with luxuriant colours” Tianjin Public Park (Four) – British Park Citation1931, 9). In the western part of the park, a rainbow-shaped frame for grapes was erected, which “looked like a crown and symbolized strength” (Editorial Team of Tianjin Landscape Citation1989, 4). Significantly, an amazing platform greenhouse with “slopes … filled with flowers” was situated near the grape frame Tianjin Public Park (Four) – British Park Citation1931, 9). One observer noted that when visitors stood on this platform, they felt they could fall into a sea of blooming flowers and know the meaning of “resting in the white lotus world and laying under the sweet glade [sic.]” Tianjin Public Park (Four) – British Park Citation1931, 9). These constructions led Victoria Park to be regarded as a tangible and geometric representation of the British character in Tianjin, satisfying the whims of the British residents. One article remarked “[Victoria Park is] just like an unsmiling British Gentleman who looked respectable [sic.]” Tianjin Public Park (Four) – British Park Citation1931, 9).

Being the centre of the British concession, Victoria Park also served as the place where the British residents held a variety of social and memorial activities to mark their identity, which, in turn, strengthened the Britishness of the park. During the first half of the nineteenth century, a number of parades, troop reviews, and other celebrations took place in the park (Power Citation2005, 10). A ceremony celebrating the coronation of King George VI was arranged with this park as the main venue on 14 May 1937 (“Yingqiao Qingzhu Yingguo Jiamian” Citation1937, 7). These ritualized political activities repeatedly promoted the British spirit and national culture and had a significant impact on the people. The playing of the national anthem, religious ceremonies, speeches by distinguished and famous persons, even the posters advertising these activities, represented a particular cultural symbol and promoted the British spirit as being something sacred. By doing this, the British residents in Tianjin both highlighted their particular identity separate from the local Chinese, and exhibited their difference to the public. Victoria Park was not only enhanced as a British space to symbolize the British spirit, but also became firmly entrenched in the symbolic life of the concession, further cementing its position as the heart of the British concession.

3. The erasure of British traces, 1941-1976

At the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the Japanese occupied Tianjin. The concession maintained its established order under British administration for several years. However, when Japan declared war on the British Empire on 8 December 1941, the Japanese army brazenly marched into the British concession, ending Britain’s de facto control of the concession (Historical Accounts Research Committee of the CPPCC Tianjin Committee Citation1986, 31). Nevertheless, the residents of Tianjin continued to interact with the heritage left by British settlers to frame the urbanism of the concession.

To publicly demonstrate their control of the area, the Japanese determined to rewrite the space within the park, eliminating signs of former British control. Although their efforts were limited by the ongoing war, the Japanese did impose new place names on the concession. The British concession was renamed the Second Xingya District (Xingyadi’erqu) – Xingya means Revitalizing the Asian (Editorial Team of the Annals of Heping District Tianjin Citation2004, 74). Likewise, the roads and streets were renamed. For example, Victoria Road was renamed The Third Road of the Second Xingya District (Xingyaerqu Sanhaolu), Meadows Road was renamed The Tenth Road of the Second Xingya District (Xingyaerqu Shihaolu) (Editorial Team of the Annals of Heping District Tianjin Citation2004, 74). Given that Meadows Road was renamed Nanlou Street (Nanlou Jie), Victoria Park was called Nanlou Park (Nanlou Gongyuan) (Guo, Zhang, and Zhang Citation2008, 253).

After Imperial Japan surrendered in August 1945, the Kuomintang (KMT) government was handed sovereignty of the former British concession in October. Like the Japanese, the KMT government did not undertake any changes to physical constructions, but intended to eliminate remaining signs of previous regimes. Thus, they turned the former British concession into a normal administrative area controlled by the Chinese government. The local government’s view was that the previous names represented British aggression and colonial rule of the Chinese. Therefore, they changed them to new Chinese names, further strengthening Chinese sovereignty. For example, the British concession was renamed the Tenth District (Shi Qu), following a sequence-number order (Editorial Team of the Annals of Heping District Tianjin Citation2004, 74). Also the streets and roads were named after Chinese provinces and cities. Hence, the roads surrounding Victoria Park, Meadows Road, Pao Shun Road, and Victoria Road, were renamed Tai’an Street (Taian Dao), Taiyuan Road (Taiyuan Lu) and Zhongzheng Road (Zhongzheng Lu) respectively. Victoria Park itself was renamed Zhongzheng Park (Zhongzheng Gongyuan) (Tianjin Bureau of Parks and Woods Citation1993, 43). Just as Victoria Park had been named after Queen Victoria, Zhongzheng Park was named after Jiang Zhongzheng (Chiang Kai-shek, 1887–1975), the leader of the Republic of China armed forces in the Second Sino-Japanese War. This renaming suggests that the former Victoria Park would continue to be situated at the centre of the city, playing a key role in the layout of the urban space, and that the KMT sought to have its ideology permeate the urban space. This is further illustrated in the use of the town hall of the former British concession, Gordon Hall, which continued to be used as the seat of the Tianjin Municipal Committee (Song Citation1950, 48).

However, the governance of the KMT only lasted four years, and was replaced by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on 17 January 1949. Given Tianjin was a metropolis, the CCP raised the taking over strategy of “follow the system, from top to down, maintain unchanged in its current state, first take over and then govern it” to keep the daily operation of the city (Yang Citation2019, 60). Despite this, with Marxism as its theoretical foundation, the ideology of the CCP viewed imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat-capitalism as the “three big mountains” (Sanzuo Dashan), or obstacles, of modern China, and regarded overthrowing these mountains as its mission (Mao Citation1945, 1102). In their eyes, Tianjin was a typical semi-colonial city with a long history of being under the control of either foreign powers or the KMT Government. Therefore, it was an urgent matter to reform the city Citation(“Tianjinshi Gongwuju 1949 nian Gongzuo Zongjie,” 1950, 651).

Given that the former British concession was created by British arrivals and renamed by the KMT government, the CCP intended to eliminate these characteristics. Just like the KMT government, the CCP renamed roads as a tool to promote its own ideology. Although most of the roads were renamed after provinces and cities, the CCP recognized the spatial significance of the former Victoria Park complex – it also seated its Tianjin municipal office in Gordon Hall – and imposed new names with a strong political and revolutionary spirit. Former Victoria Park was renamed Liberation North Park (Jiefang Beiyuan), while former Victoria Road was renamed Liberation North Road (Jiefang Beilu) (Guo, Zhang, and Zhang Citation2008, 253). In the discourse of the CCP, “liberation” is the mainstream term that was, and still is, used to push and publicize the legitimacy of the CCP’s revolution, insurrection, and usurping of power, and thus, this name once again acknowledges the significance of the former Victoria Park in the urban space of Tianjin (Mohanty Citation1991, 32).

Like the KMT, the CCP did not initially make any alterations to the physical constructions in the park. However, in the 1950s a series of political movements swept across China prompting the authorities to further eliminate traces of British arrivals. In 1954, they removed the cenotaph and replaced it with a red poster wall with an engraved poster and a quote from Mao’s Little Red Book: “People of the world unite to defeat American imperialism and all it runs!” (Quanshijierenmin Lianheqilai, Dabai Meiguoqinluezhe Jiqiyiqiezougou!) Additionally, several red signs, with famous quotes from Chairman Mao, were erected in the park after the breakout of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Continually conveying the message of the revolution to, among other goals, erase traces of British colonialism became a function of the park.

4. The neglected corner, 1976-2005

1976 witnessed a turning point for Tianjin. On the one hand, the Cultural Revolution ended in this year and China entered into a new period of development. On the other hand, the Tangshan Earthquake brought about tremendous losses to Tianjin, particularly the historical British concession. For example, 91 percent of the buildings in Chongren Li, a residential block of the concession, suffered first-degree damage, and the other areas suffered damage to the third to fifth degree (The Urban Construction Headquarters Office of Tianjin Citation1981, 19).

Nevertheless, this forced the residents of Tianjin to pay more attention to urban construction. The Tianjin municipal government invested 153.56 billion RMB in urban construction from 1981 to 1990, and competed a series of significant infrastructure works, such as the diverting of water from the Luan River to Tianjin (Yinluanrujin), and the construction of railways and a communication hub. They also constructed 31.66 million square metres of new housing in the city, as well as a great number of significant official, commercial and transportation buildings, such as the Tianjin Telegraph Building (Tianjindianbao Dalou), the High Court Building (Tianjingaojirenminfayuan dalou), and the Friendship Stores (Youyi Shangdian) (Tianjin General Annals Editing Committee Citation1996a, 42). These new constructions employed modern architectural styles and designs. They well symbolized Tianjin’s stepping into a completely new era. Thus, these buildings soon became significant landmarks in Tianjin and were brightly highlighted on city maps (Citation1984nian Tianjin Jiaotong Lvyoutu [Tianjin Traffic and Travel Map in Citation1984] 1984). ()

Figure 4. The city map of Tianjin in 1984. It shows the significant buildings of Tianjin at that time, most of them were built during the 1980s. (Source: drawn by author based on 1984 nian Tianjin Jiaotong Lvyoutu [Tianjin Traffic and Travel Map in 1984] (Tianjin: Tianjin people press, 1984).).

![Figure 4. The city map of Tianjin in 1984. It shows the significant buildings of Tianjin at that time, most of them were built during the 1980s. (Source: drawn by author based on 1984 nian Tianjin Jiaotong Lvyoutu [Tianjin Traffic and Travel Map in 1984] (Tianjin: Tianjin people press, 1984).).](/cms/asset/8ba7acea-55a8-4eb0-935b-e968823eda16/tabe_a_2153597_f0004_oc.jpg)

In contrast to the prosperous urban renovation, Victoria Park became a neglected corner of the city. A major landmark of the former British concession, Gordon Hall, the seat of the Tianjin Municipal Committee, was demolished in 1981, with the official explanation that damage to the structure resulting from the earthquake was beyond repair, even though the Tangshan Earthquake had taken place five years earlier.Footnote3 An office building was constructed on the site of former Gordon Hall in 1985 (Tianjin Bureau of Real Estate Citation1999, 175). Similar to other significant newly built constructions, this nine-story building featured a modern style, with a symmetrical layout of three lateral zones and a perforation of vertical lines, even though it contrasted with neighbouring constructions that were put up in the concession days (Tianjin General Annals Editing Committee Citation1996a, 816–7). () This new building also included a wall separating it from the former Victoria Park. Likewise, although its layout remained, the former Victoria Park itself was downgraded into a pocket park for providing leisure and relaxation for workers from the governmental centre. A rockery, as well as a water pool, replaced the poster wall with quotations from Mao Zedong in the northeast corner. The amazing greenhouse located in the west part of the park was demolished during the Tangshan Earthquake, and an artificial rock and some service buildings replaced it (Tianjin Bureau of Parks and Woods Citation1993, 136). Furthermore, several sculptures and sports facilities were established in the park (Tianjin Bureau of Parks and Woods Citation1993, 136). Thereafter, Victoria Park became a “must visit” attraction for local inhabitants, especially children. It has been said that this park was a fantasy paradise; even the steps of the central pavilion became slides for the children, which were said to be polished by children’s “behinds”. Even the name of the park was substituted to become the Municipal Committee Park (Shiwei Gongyuan) because it was located in front of the seat of the Tianjin Municipal Committee.

Figure 5. The new City Hall of Tianjin featuring modernism, photographed from Victoria Park. (Source: Contemporary Tianjin Urban Development Editing Studio, Dangdai Tianjin Chengshi Jianshe [Contemporary Tianjin Urban Development] (Tianjin: Tianjin people press, 1987), unpaged.).

![Figure 5. The new City Hall of Tianjin featuring modernism, photographed from Victoria Park. (Source: Contemporary Tianjin Urban Development Editing Studio, Dangdai Tianjin Chengshi Jianshe [Contemporary Tianjin Urban Development] (Tianjin: Tianjin people press, 1987), unpaged.).](/cms/asset/91ef505c-fe1d-46c4-a39c-e7662488f92a/tabe_a_2153597_f0005_oc.jpg)

Even so, the former glory of Victoria Park, together with the other famous buildings constructed in the concession days, was almost completely obscured from the public consciousness. Publications such as urban chronicles, travel guides, and postcards of that time rarely mentioned this park, and any snippets of information portrayed the park in a negative light. For example, Tianjin Landscape and Greening, a monograph published in 1989, stated that “in order to transfer the foreign concessions into an invading base, the foreign imperialists formulated colonial rules and built municipal constructions. Therefore, public parks were subsequently established in the concessions to meet the entertainment needs of the invaders” (Editorial Team of Tianjin Landscape Citation1989, 3).

Newspaper and journal articles sought to reinvent the former Victoria Park as the site of British bullying of local Chinese by repeatedly highlighting the regulations that banned Chinese from entering the park. This report exaggerated the regulation by noting that “a sign with a garden rule was hanging on the front gate during the concession days, which said ‘Dogs and Chinese Not Admitted’ and ‘dogs not on a leash/accompanied by a person are not permitted’” (Zhang, Wei, and Keqin Citation1982, 159). Since the character for “dog” is also a dehumanizing or cursed epithet in the discourse of Chinese culture – such as “goucai” referring to a despicable horde – it is insulting to juxtapose Chinese people with dogs, and especially to post it on a sign for the public (Bickers and Wasserstrom Citation1995, 444). Nevertheless, as previously stated, although there was a rule stating Chinese needed a ticket to visit the park, this rule was abandoned in 1926, and was never displayed on the gate. Also, a photograph, taken some time between 1937 and 1939, indicates this statement was exaggerated. As shows, we can see there was a sign on the front of the gate, however, it simply said “NO DOGS ALLOWED TO ENTER THE PARK” (Buzhun Xiequanruyuan), with no mention of Chinese. ()

Figure 6. A view of Victoria Park in 1930s, which shows the sign in front of the gate. (collected by author).

Both the neglect of the former Victoria Park and the continued emphasis on the hegemony of British settlers, including the bullying of Chinese, resulted in a negative reaction towards concession history. This was what the CCP proposed to achieve. Since the CCP had suffered from mega-disasters of the previous decades, especially the Cultural Revolution, the CCP in Tianjin urgently needed strong support for its own ruling position. Therefore, through these negative assertions, they sought to create a new sense of national purpose. Representing national humiliation, the rule stating “Chinese are not permitted to enter the park” not only inspired patriotic feelings in Chinese commoners, but also strongly highlighted the contributions of the CCP to the Chinese nation, which, in turn, enhanced the rationality of the CCP rule. Also, it was implied that a benefit of the liberation by the CCP was that ordinary Chinese citizens obtained the right to access “the park, where it was impossible to enter before the sovereignty of the concession was given back to China.”(Tianjin Tourism Administration Citation1990, 13) A news article in 1999, entitled The Master of Gordon Hall has been Changed, stated that in the years that followed liberation, a foreign woman allowed her dog to bite a Chinese girl in Victoria Park. It further related that when this came to the attention of the officers of the CCP government, they meted out just punishment to the woman (“Gedengtang Huanle Xinzhuren [Master of Gordon Hall has Been Changed]” Citation1999, 8). Subsequently, many officers who had worked for the former government boasted, “In the past, Chinese people had to show great respect to foreigners, who were untouchable! But today, we are our own masters!” Gedengtang Huanle Xinzhuren [Master of Gordon Hall has Been Changed] Citation1999, 8)

This all conveyed the same message: Thanks to the contribution of the CCP, Chinese could take control of their own country, instead of being bullied by the British settlers. Hence, the more painful the picture of Chinese suffering under the British settlers, the more enormous were the perceived changes under the CCP which was focused on China’s national interests. Likewise, it was natural that the golden time of former Victoria Park, the eliminating of discrimination against the Chinese (including the ban on Chinese entering the park), and the reclaiming of the sovereignty of the concession by the KMT Government, disappeared from the official chronicles. Thereafter, Victoria Park, as well as the other glorious urban constructions created in the concession days, had to be removed, or eliminated from the public realm, to give way to new, modern constructions.

5. A precious heritage, 2005-present

Stepping into the twenty-first century, China launched into a new stage of rapid urbanization. Clusters of new high-rise buildings have emerged in Tianjin, creating an ideal image of an international financial and trading centre. This, in turn, drove the municipal government to draw more attention to its historical monuments.

In 1994, Tianjin Urban Planning Bureau drafted the publication, Several Administration Rules for the Tianjin Historical Protected Block (Government of Tianjin City Citation1994). Two years later, the Bureau introduced the concept of a Historic Conservation Area into its urban plan, and set out eleven Historic Conservation Areas in its General Urban Plan of Tianjin (1996–2010), including Residences around Central Park in the centre of the former French concession, “Yigong” Garden-like Residential Zones in the former Italian concession, and Residences around Five Main Roads in the senior residential district of the former British concession (Government of Tianjin City Citation1996).

In 2005, the General Urban Plan of Tianjin (2005–2020) listed the area centred around the former Victoria Park as Tai’an Street Historic Culture Conservation Area (Government of Tianjin City Citation2005). Since it was a former British concession, this area of British-themed landscape was also named the British Culture Landscape Block (Government of Tianjin City Citation2005). Consequently, a series of improvements and renovation works took place in the Tai’an Street Historic Culture Conservation Area to reconstruct and rejuvenate the cityscape of the former British concession. With repainted façades, buildings that were founded in the concession days presented spectacular views, even losing the signs of aging, while some recent buildings have been constructed to be “more British-looking” by using grey or red brick, and being decorated with new Gothic-style architectural elements, such as mouldings, shutters, and spires. Furthermore, other buildings, such as the office of the Tianjin Municipal Committee that was constructed in the 1980s, were removed and replaced with new buildings. These new buildings, both skyscrapers and multi-storey dwellings, have all been constructed with an ostensibly “more British-looking” design. However, their disproportionate façades and less sophisticated details betray inaccurate Chinese perceptions of contemporary Chinese architecture of nineteenth century England, and thereby appear ridiculous. ()

Figure 7. The view of Victoria Park and its surroundings with “more British-looking” design. The building is Ritz-Carlton Hotel, situated on the former site of Gordon Hall. (Source: photographed by author.).

Being the heart of the historical British concession, the former Victoria Park has been remembered by the public with the rise of Tai’an Street Historic Culture Conservation Area, and praised as a “famous historical park” (“Jiefangbeiyuan Kaifang Kaifangshigongyuan Tixian Oushitedian [Jiefang Bei Park is open to the public. the opened park presents features of a European park]” Citation2011, 2). To restore the brilliance of the concession days, “renovation work” was undertaken in the park in 2011. The sports facilities for children were removed; the old steps of the central pavilion were replaced; the park pathways were paved with granite and anticorrosive wood; and a blooming crab apple tree was planted on the former site of the cenotaph. Importantly, the wall surrounding the park, which had existed since the park was founded, was totally removed, and the park became a square surrounded by high-rise buildings, but no longer an enclosed designed landscape.

Although the conservation work was claimed to be “based on the historical original appearance and partially restored the park to the original British view”, the appearance of the park after the work presented a status quo, a considerable disparity from the view in the historical archives Jiefangbeiyuan Kaifang Kaifangshigongyuan Tixian Oushitedian [Jiefang Bei Park is open to the public. the opened park presents features of a European park] Citation2011, 2). Like other recently completed buildings in this area, the former Victoria Park, except for the layout of the pathways and the inclusion of two pavilions, has changed significantly, and reveals contemporary Chinese presumptions regarding historical British gardens. However, whether the park looks like a real British Park, or the historic Victoria Park, seems to be of no importance to the ongoing development of the former British concession. The Ritz-Carlton Hotel and Starbucks Café have been established at this historical site, and recently built offices and residences around Victoria Park have become first-class property. Involved in the development strategy of Tai’an Street Historic Culture Conservation Area, the former British concession is on the way to becoming the financial, business and service core of Tianjin, becoming a precious heritage for the city.

6. Conclusion

By examining the evolution of Victoria Park from the nineteenth century to the present, we can see that the interaction between the British arrivals and local Chinese residents determined the urban development of the British concession. When the British arrivals landed in Tianjin, they responded to the local situation to construct a hybrid landscape, Victoria Park, providing an entertainment place for the residents. With interaction between the British arrivals and Chinese people during the rise of modern China, this park became the heart of the concession, representing the British spirit. But this glorious era rapidly faded when China regained sovereignty of the concession, and the park’s heritage was not only denied by the CCP, but also rewritten into a legend that the British settlers bullied Chinese, to highlight the CCP’s contribution to the national interest. However, with rapid urbanization in the twenty-first century, the people of contemporary Tianjin recognized the value of their city’s colonial history and turned it into a motivating force to develop the economy. Victoria Park has subsequently been seen as part of the precious heritage of the city.

During this process, the park was shaped by both tangible means – such as construction, reconstruction, or removal of landscape architecture – and intangible means – such as the imposition of new names and restructuring of the public memory – to bestow spiritual significance on the physical landscape of the public park. The latter developments were based on and influenced by the earlier historical phases, while successive generations of varied discourses syncretized, forming the landscape of today. Experiencing this palimpsest-like change, Victoria Park shaped interaction between local Chinese and British residents during a period of rapid evolution within Chinese society. It forged British urbanism in China, chiselling its influence in stone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yichi Zhang

Dr Yichi Zhang is a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo, and editorial board members of the journal Architectural Histories and the journal Landscape Architecture Frontiers. He was a Postdoctoral Fellow (2019) at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale University, and research fellow (2015) in Garden and Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. He is recipient of both the 13th Annual Mavis Batey Essay Prize, 2017 (the Garden Trust, the UK) and the Annual Award for Post-Doctoral Scholars, 2017 (Geographical Society of New South Wales, Australia). His research interests include transnational architecture production, green urbanism, urban geography, modern Chinese urban and garden history, and the history of British settlements in China.

Notes

1 “MCMXIV-MCMXIX” and “1914–1919” are the dates of the beginning of the war and of the Treaty of Versailles.

2 There were eight concession public parks in Tianjin existing around 1931.

3 A satellite aerial map taken in 1980 showed that Gordon Hall was in good condition in the early 1980s.

References

- 1984 nian Tianjin Jiaotong Lvyoutu [Tianjin Traffic and Travel Map in 1984]. 1984. Tianjin: Tianjin People Press.

- Another Mother. 1895. “Correspondence: The Public Gardens.” Peking and Tientsin Times, 6 July 1895, 280.

- Astor House Hotel. Ltd. 1904. Guide to Tientsin. Tientsin: Tientsin press.

- Bickers, R. A. 1999. Britain in China: Community Culture and Colonialism, 1900-1949. Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press.

- Bickers, R. A., and J. N. Wasserstrom. 1995. “Shanghai’s “Dogs and Chinese Not Admitted” Sign: Legend, History and Contemporary Symbol.” The China Quarterly 142: 444–466. doi:10.1017/S0305741000035001.

- Chen, Y. 2008. “The Making of a Bund in China: The British Concession in Xiamen (1852-1930).” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 38: 31–38.

- Cohen, P. A. 1997. History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Convention of Peking. 1860. In Treaties, Conventions, Etc., between China and Foreign States. edited by China Imperial Maritime Customs 430–434. Shanghai: Published at the Statistical Dept. of the Inspectorate General of Customs.

- Cranz, G. 1982. The Politics of Park Design: A History of Urban Parks in America. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Denison, E., and G. Ren. 2006. Building Shanghai: The Story of China’s Gateway. Chichester: Wiley-Academy.

- Drake, N. F. 1900. Map and Short Description of Tientsin. S.l: s.n.

- Editing Committee of The Concessions of Powers in China. 1992. Editing Committee of the Concessions of Powers in China, Lieqiang Zai Zhongguode Zujie [The Concessions of Powers in China]. Beijing: Chinese Literature and History Press.

- Editorial Team of the Annals of Heping District Tianjin. 2004. Tianjinshi Hepingqu Zhi [The Annals of Heping District, Tianjin]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Editorial Team of Tianjin Landscape. 1989. Tianjin Yuanlin Lvhua [Tianjin Landscape and Greening]. Tianjin: Tianjin Science and Technology Press.

- “Gedengtang Huanle Xinzhuren [Master of Gordon Hall has Been Changed].” 1999. Tianjin Ribao [Tianjin Daily], 16 August 1999, 8.

- Government of Tianjin City. 1994. Tianjinshi Fengmaojianzhudiqu Jiansheguanli Ruoganguiding [Rules for the Tianjin Historical Protected Block]. Tianjin: Government of Tianjin City.

- Government of Tianjin City. 1996. Tianjinshi Chengshizongtiguihua (1996-2010) [General Urban Plan of Tianjin (1996-2010)]. Tianjin: Government of Tianjin City.

- Government of Tianjin City. 2005. Tianjinshi Chengshizongtiguihua (2005-2020) [General Urban Plan of Tianjin (2005-2020)]. Tianjin: Government of Tianjin City.

- Guo, X., T. Zhang, and Y. Zhang. 2008. Tianjin Lishi Wenhua Mingyuan [Tianjin Historical Famous Gardens]. Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Press.

- Haiyan, L. 2006. “Shehuibiange Yu Jindai Tianjin Chengshi Kongjian de Yanbian [Foreign Concessions, Social Transformation and Urban Spatial Evolution in Modern Tianjin].” Tianjinshifandaxue Xuebao (Shehuikexueban) [Journal of Tianjin Normal University (Social Science)] 186 (3): 36–41.

- Haiyan, L. 2011. “Water Supply and the Reconstruction of Urban Space in Early twentieth-century Tianjin.” Urban History 38 (3): 391–412. doi:10.1017/S096392681100054X.

- Historical Accounts Research Committee of the CPPCC Tianjin Committee. 1986. Tianjin Zujie [Tianjin Concessions]. Tianjin: Tianjin People Press.

- Jackson, I. 2017. Shaping Modern Shanghai: Colonialism in China’s Global City. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- “Jiefangbeiyuan Kaifang Kaifangshigongyuan Tixian Oushitedian [Jiefang Bei Park is open to the public. the opened park presents features of a European park].” 2011. Jinwan Pao Newspaper, 29 August 2011, 2.

- Luo, S. 1993. Jindai Tianjin Chengshishi [Modern Tianjin Urban History]. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press.

- Mao, Z. 1945. “Yugong Yishan [Mr. Fool Wants to Move the Mountain.” In Mao Zedong Xuanji [Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung], edited by Z. Mao, 1101–1104. Beijing: People Press.

- McLeish, W. 1914. Memories of Tientsin, an Old Hand. Tientsin: Tientsin Press.

- Mohanty, M. 1991. “Swaraj and Jiefang: Freedom Discourse in India and China.” Social Scientist 19 (10/11): 27–34. doi:10.2307/3517801.

- Power, B. 2005. The Ford of Heaven: A Childhood in Tianjin, China. Oxford: Signal Books.

- Rasmussen, O. D. 1925. Tientsin; an Illustrated Outline History. Tientsin: Tientsin Press.

- Rogaski, R. 2004. Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in treaty-port China. Vol. 9Asia-Local studies/global Themes. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Song, Z. 1950. “Jieguang Guomingdang Tianjinshi Zhengfu [The KMT Government Taking over in Tianjin”. In Tianjin Jieguan Shilu [The History of Takeover Tianjin], Edited by Resources Collection Committee of CCP Tianjin, 45–49. Tianjin: CCP History Press.

- Sun, Y., N. Aoki, and T. Zhang. 2012. “Tianjin Weiduoliya Gongyuan Lishijincheng Yu Zaoyuanfengge Tanxi [Research on the Historical Process and Gardening Style of Victoria Park in Tianjin].” Jianzhuxuebao [Architectural Journal] S1: 35–39.

- Tianjin Bureau of Parks and Woods. 1993. Chengshi Yuanlin [Urban Landscape]. Tianjin: Tianjin Bureau of Parks and Woods.

- Tianjin Bureau of Real Estate. 1999. Tianjin Fangdichangzhi. [The Annals of Real Estate in Tianjin]. Tianjin: Tianjin Academy of Social Sciences.

- Tianjin General Annals Editing Committee. 1996a. Tianjin Tongzhi Chengxiangjianshezhi I [General Annals of Tianjin—Urban and Rural Construction I] Tianjin. Tianjin: Academy of Social Sciences Press.

- Tianjin General Annals Editing Committee. 1996b. Tianjin Tongzhi Fuzhi Zujie. General Annals of Tianjin— Foreign Concessions. Tianjin: Tianjin Academy of Social Sciences Press.

- “Tianjin Public Park (Four)—British Park.” 1931. Takung Pao Newspaper, 30 July 1931, 9.

- Tianjinshi Gongwuju 1949 nian Gongzuo Zongjie [The Work Summaries of Tianjin Works Bureau in 1949. 1950. Tianjin Jieguan Shilu [The History of Takeover Tianjin]. edited by Resources Collection Committee of CCP Tianjin 651–667. Tianjin: CCP History Press.

- Tianjin Tourism Administration. 1990. Tianjin Zhinan. Travel Guide of Tianjin. Tianjin: Tianjin Science and Technology Press.

- The Urban Construction Headquarters Office of Tianjin. 1981. Tianjinshi Zhenzai Zhuzhai Huifu Chongjian Ziliaohuibian [The Source of the Reconstruction of Earthquake Damaged Residence in Tianjin]. Tianjin.

- Whiteman. 1895. “Correspondence: The Public Gardens.” Peking and Tientsin Times, 6 July 1895, 280.

- Yancevetsky, D. 1983. The Eye-Witness Account of Eight Allied Armies. Tianjin: Tianjin people press.

- Yang, Y. 2019. “Renminzhengquan Zai Tianjin de Jianli [The Establishment of CCP Government in Tianjin].” Qiuzhi [Seeking Knowledge] 2: 60–62.

- “Yingqiao Qingzhu Yingguo Jiamian [The British Settlers Celebrate the Coronation of the Britain Emperor]” 1937. Takun Pao Newspaper, 15 May 1937, 1.

- Zhang, Y. 2010. “The First British Concession Garden of Tianjin- Victoria Garden.” Modern Landscape Architecture 5: 44–47.

- Zhang, Y. 2012. “Victoria Park in Tianjin: A British Square in the Chinese City, Past, Present and Future.” Master’s dissertation. Faculty of Engineering, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

- Zhang, C., D. Wei, and F. Keqin. 1982. “Tianjin Chengshi Yuanlinshi Gaishu [Tianjin Urban Landscape History].” Tianjin Wenshi Ziliaoji [Tianjin Historical Resources] 2: 153–162.

- Zhou, D. 2009. Hankoude Zujie: Yixiang Lishishehuixuede Kaocha [The Concession in Hankou – An Examination on Historical Sociology]. Tianjin: Tianjin Education Press.