ABSTRACT

The Kumbum Monastery is a typical example of a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in China. This study focuses on 12 palace buildings within the Kumbum Monastery and aims to clarify the historical origins of their architecture, the regional architectural characteristics, and the influence of multiple cultures on the monastery. The study uses typological approaches and quantitative methods to analyze the architecture’s characteristics and origins (spatial layout, architectural forms, construction technology, and decorative elements). This paper attempts to provide a typological approach for the study of the history of the architextures in the Kumbum Monastery as well as a comprehensive understanding of the architecture through a culturally pluralistic perspective. The analysis shows that 1) the palace buildings are a complex mixture of traditional Tibetan architecture, Han-style architecture from the Central Plains during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and arched buildings from Central Asia and Inner Mongolia; 2) the palace buildings localized different cultures and reshaped their spatial modeling and spatial meaning through the means of “hybridity” and “adjustment”; 3) the complex multicultural nature of the palace buildings is due to the comprehensive influence of political changes, religious dissemination, trade and transportation, and ethnic migration from the Ming Dynasty to the Republic of China.

1. Preface

1.1. Background and purpose

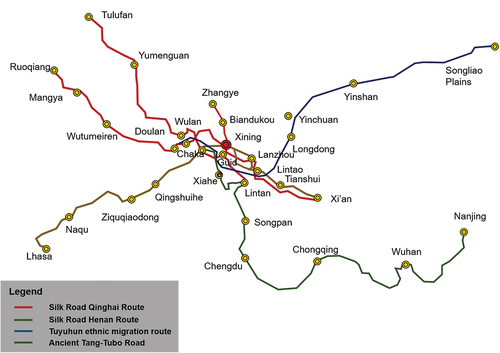

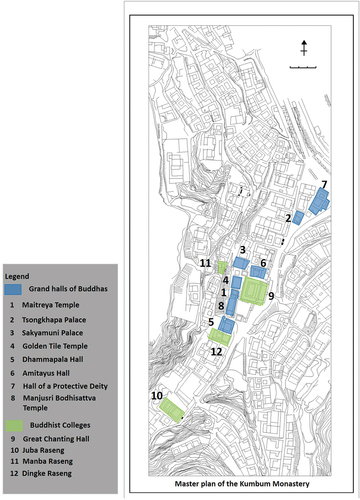

The Kumbum Monastery (Tibetan: སྐུ་འབུམ་བྱམས་པ་གླིང) is one of the Gelugpa sect’s principal monasteries. It covers an area of 480,850 m2, a built area of 100,000 m2, and comprises 52 palace buildings, totaling 9,300 rooms. Its construction lasted 563 years, from 1379 to 1942. It is located in a narrow valley in Lushaer, Huangzhong County, Xining, Qinghai, China (). This geographical location was at the center of the later period of Tibetan BuddhismFootnote1 (978 A.D.) and is the birthplace of the Gelugpa sect. It is also at the juncture of key ancient traffic routes, such as the Silk Road, the ancient Tang-Tubo Road, and the Tuyuhun ethnic migration route in Amdo (). Consequently, the Kumbum Monastery’s architecture exemplifies both religious localization and multicultural integration. As the region’s religious center, the Kumbum Monastery reflects the historical process of reshaping the spatial significance of Qinghai Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the context of religious localization and multicultural integration.

Figure 1. Location of the Kumbum Monastery.

This study focuses on 12 typical palace buildings in the Kumbum Monastery and aims to clarify their characteristics, architectural origins, formation, and evolution from the viewpoint of the spatial layout, architectural forms, construction technology, and decorative elements as well as their relation to religious localization and multicultural integration.

1.2. Correlative concepts

1.2.1. Culture

Though the concept of culture is very broad, this study focuses on traditional culture given that the construction of the palace buildings in the Kumbum Monastery took place between 1379 and 1942. This period covers China’s ancient feudal society (1379–1911) and its transition away from feudalism (1912–1942).

1.2.2. Multiculturalism

This concept signifies that there is not a single cultural force in a given historical context. This paper focuses on the many traditional cultures that have directly and indirectly influenced the palace buildings in the Kumbum Monastery. These cultures include traditional Tibetan architecture, the Han-style architecture of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and those of Central Asia and Inner Mongolia.

1.3. Literature review

Previous research on the Kumbum Monastery’s architecture has predominantly examined its architectural arts and overall spatial characteristics (Su Citation1996; Yang Citation2009; Deng Citation2016). The first author of this study investigated the distribution of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Qinghai (Ran Citation1994). Scholars have also focused on the monastery’s architectural structure and material characteristics (Pu Citation2014) and the decoration of the main buildings (Chen Citation1999; Miao Citation2019). From 1992 to 1994, the Chinese government funded a comprehensive renovation of the Kumbum Monastery, including the surveying and mapping of its main buildings. This work provides the data examined in this article (Jiang and Liu Citation1996).

This research has recognized that the original spatial structure and architectural form of the Kumbum Monastery are well preserved and that its architecture is diverse and complex. However, at present, there is little research exploring the architectural history and development of the monastery. Furthermore, when analyzing the origins of the monastery’s architectural culture, considerable attention has been paid to the development of the relatively strong Tibetan and Han backgrounds (Bo Citation2006; Long Citation2016; Dun Citation2020), while the influence of other cultures has been neglected. The description of the complexity and the totality of the temple is also relatively insufficient. In contrast to the existing literature, this study focuses on the typical palace buildings in the Kumbum Monastery from a culturally pluralistic perspective to explore the origins and vicissitudes of its architecture.

Moreover, with the continuous advancement of cities in Qinghai, the static protection and dynamic development of the 655 Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the province are facing severe challenges. Therefore, to further discuss the originality of the design of Qinghai Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, this study focuses on the Kumbum Monastery’s composition and construction history and tries to reveal the mechanism behind its development. The study is thus significant for the static protection and dynamic improvement of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the region.

Based on the above, this study selects 12 palace buildings in the Kumbum Monastery as its research objects. Looking at the spatial layout, architectural form, building structure, and decorative elements, the study analyzes the architectural characteristics of the Kumbum Monastery. It also explores the origins of its architectural culture, and the process of transformation and localization to further reveal the mechanism of its development.

1.4. Study objects and methodology

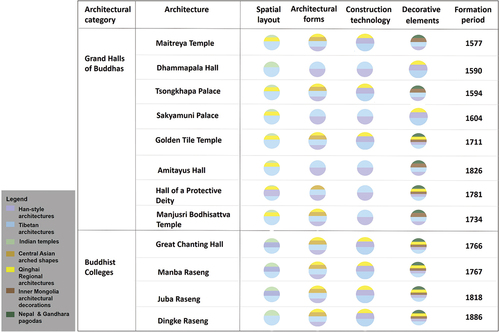

According to the construction priority of each building’s period and the importance of the spatial function of the structure, 12 buildings ( and ) are considered as study objects from a total of 52. The 12 cases comprise eight Grand Halls of Buddhas and four Buddhist colleges. The grand halls constitute spaces that enshrine holy objects for worshippers, while the colleges are where the Gelugpa monks study Buddhism, astronomy, calculus, and medicine, and where they chant the sutras.

Figure 3. The location of the selected buildings.

Table 1. The selected buildings.

Maps of the monastery, photographs, data from the surveys and maps of the 1992–1994 renovation project (Jiang and Liu Citation1996), and related histories and information were collected from the literature; field research and online map services were consulted and classified; and interviews with monks and craftsmen were analyzed and illustrated in the analysis map.

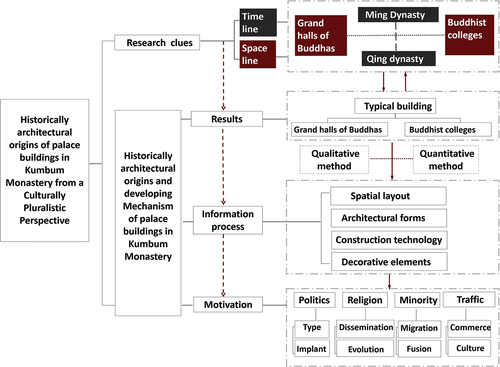

The study then uses time and space as research clues. In terms of temporal clues, since the palace has undergone continual reconstructions and expansions and because historical data for the original building are missing, the time of the primary structure and architectural form is selected as the classification principle for the construction period. In terms of spatial clues, based on the spatial function of the building, the research objects can be divided into Grand Halls of Buddhas and Buddhist colleges.

With regard to the multiple cultural influences on the architecture, four aspects are considered important for investigating historical and architectural origins: spatial layout, architectural form, building structure, and decoration. Based on these four aspects, this study develops as follows. First, the master plan (functional zone, traffic system, and spatial configuration) and the construction period are organized as related background factors. Second, the spatial layout is examined by comparing the similarity between the buildings and the archetype (spatial layout, spatial enclosure elements, and spatial sequence). Third, the architectural form is analyzed through the basic elements and the combination of roof forms and arched doors. Fourth, the building structure is discussed by examining the load-bearing structure and the structural proportions. Then, the decorative elements are investigated through the three main decorative parts of the walls, doors and windows, roofs, and corridors. Fifth, the development process is analyzed by comparing the similarity between the buildings, the archetype, and the historical contexts. Sixth, the mechanism of development is understood according to the construction period and the historical and cultural contexts ().

2. Master plan: functional zone, traffic system, and spatial configuration

The master plan of the Kumbum Monastery can be examined from three different aspects: the functional zones, the traffic system, and the spatial configuration.

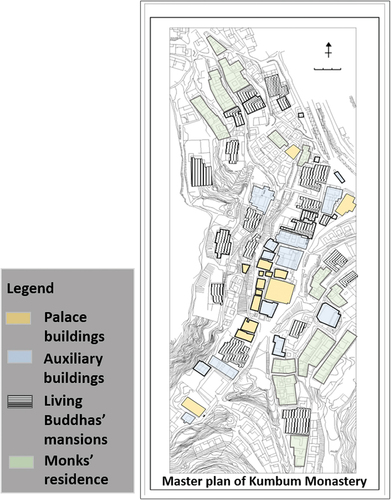

The monastery has four functional zones: the palace buildings district, the auxiliary buildings district, the living Buddhas’ mansions district, and the monks’ residences district. Among them, the palace buildings district, where the dominant Buddhist activities and religious education are conducted, consists of eight Grand Halls of Buddhas and four Buddhist colleges. This district is located in the center-north area. The auxiliary buildings district includes nine auxiliary constructions and is located to the west of the main road, that is, adjacent to the palace buildings district. The living Buddhas’ mansions district is composed of 20 mansions of different hierarchies, which are used for the daily affairs of the living Buddhas. This district is found northwest of the temple. There are also a few scattered buildings in the southeast. The higher the level of the living Buddha mansion, the closer its location to the palace buildings district. The monks’ residences district can be divided into three parts: northernmost, easternmost, and a part that is interspersed at the southernmost end of the monastery ().

Figure 5. The functional zones of the Kumbum Monastery.

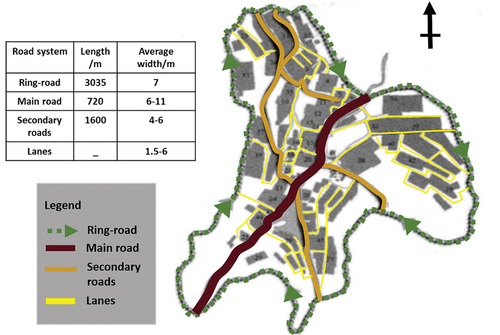

The monastery’s road system consists of a four-level structure with a main road, secondary roads, lanes, and ring roads. Among them, the main road runs southwest–northeast. There are four secondary arterial roads. The laneways are composed of spaces defined by the walls of the individual buildings of the temple, so they vary in width. The total length of the ring road is about 3,050 m. The road system is connected to the entrances and exits ().

The overall spatial features of the monastery can be analyzed from horizontal and vertical perspectives. From a horizontal perspective, the whole monastery is centered on the hall area. The annexes and living Buddhas’ mansions are built around the center and fitted with monastic cells. The prayer wheel path surrounds the spatial layout of the whole monastery. In the four-level road system, the main road crosses the whole monastery from south to north, while the four secondary trunk roads connect the four functional zones. The lanes defined by each exterior wall lead everywhere within the monastery. The horizontal spatial layout has no distinctive axis but is distributed freely in accordance with the topography, showing an obvious centripetal structure. From a vertical perspective, the topography of the monastery is divided into a high area to the south and a low area to the north. The palace buildings and institutes are mainly located in the high areas. The height differences of the structures range from 55 m to 90 m. The biggest difference (90 m) is that between Dingke Raseng (2,750 m) and the eight Great Deeds Stupas (2,660 m). The whole monastery presents a tiered order of main buildings–cells in the spatial section.

3. Construction history

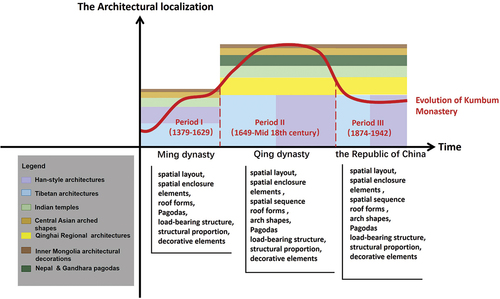

Considering the sociopolitical background, major historical events, and the development of the monastery’s organization, the construction history of the Kumbum Monastery can be divided into three periods: building the prototype (1379–1648), completing the Buddhist colleges (1649–1873), and continuing the construction (1874–1942).

During Period I (1379–1648), six Grand Halls of Buddhas, the Great Chanting Hall, and one pagoda were preliminarily built around the Lianju Pagoda (the first pagoda to be built to commemorate Tsongkhapa) for religious memorial significance.Footnote2 This initial construction happened with the support of the tripartite forces of the Ming Dynasty (La Citation2001),Footnote3 the Tibetan Buddhist groups, and the feudal lords of the ethnic minorities in Qinghai, following the instructions of eminent monks.

In Period II (1649–1873), the Qing Dynasty recognized the wide influence of the Gelugpa sect and hoped to use the sect’s leadership in Tibetan Buddhism to consolidate its rule over Mongolian and Tibetan areas. The religious police,Footnote4 therefore, switched from admiring only the Gelugpa sect to allowing all sects to develop. This led to the Gelugpa sect gradually controlling administrative power in Qinghai. As the central monastery in the region, both the size of the Kumbum Monastery and its number of monks increased significantly. This led to the completion of the Buddhist education system and its buildings. During this period, the overall spatial configuration of the monastery was formed, with the construction of 16 buildings (four Grand Halls of Buddhas, three Buddhist colleges, three mansions, four auxiliary buildings, and two pagodas), including both reconstruction and expansion.Footnote5

In Period III (1874–1942), the Chinese rural economy disintegrated due to political incompetence, and the feudal social system of the Qing Dynasty gradually declined. As a result, little attention was paid to the development and construction of Tibetan Buddhism. After the establishment of the Republic of China, the government intended to redress the long-term spatial imbalance in Tibetan Buddhism’s development in Qinghai. It therefore issued a series of laws and regulations to build more temples outside the Hehuang region (Zhu Citation2006) and limit new construction inside it. Because of this, the Kumbum Monastery shifted its economy from construction to reconstruction and restoration, which involved four Buddhist colleges, one Grand Hall of Buddhas, and one pagoda.

Throughout the three stages above, although the development strategy was important, construction activities always gave priority to the Buddhist temples and colleges ().

Table 2. The historical and cultural contexts of the Kumbum Monastery’s construction.

4. The multicultural architectural origins and the regional formation of the Kumbum Monastery’s palace buildings

4.1. The architectural origins and the regional formation of the spatial layout

According to Tibetan Buddhist thought, the spatial layout of monasteries is the carrier of the religion’s philosophy and rituals (Ran Citation1994; Deng Citation2016). Therefore, the architectural origins and regional formation of the spatial layout of the Kumbum Monastery’s palace buildings can be analyzed from three perspectives: the spatial layout, the spatial enclosure elements, and the spatial sequence.

4.1.1. The spatial layout

The spatial layout of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries reflects the religion’s concept of space and the local cultural contexts (Chen Citation1999; Xu Citation2004; Long Citation2016). In the Kumbum Monastery, the spatial layout of the overall monastery and the individual buildings embody the characteristics of the surrounding layout.

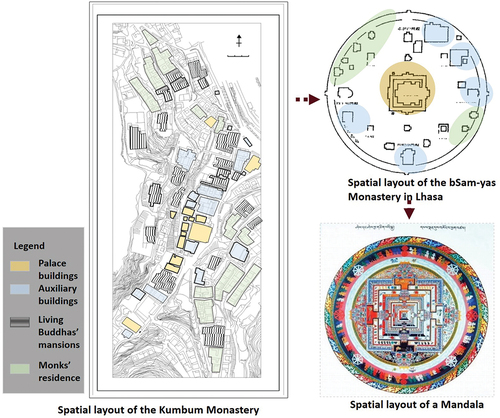

At the macroscale, the overall spatial layout shows that the palace buildings are located in the center, the auxiliary buildings and the living Buddhas’ mansions surround the center, and the monks’ residences are scattered around the fringes of the monastery. This centripetal spatial layout can be seen in the early Tibetan Buddhist monasteries of Lhasa, such as the bsam-yas Monastery, and in the typical configuration of a mandala.Footnote6 This overall spatial layout expresses the distribution pattern around the core elements (). Meanwhile, since the origin of the Kumbum Monastery was the existing tower (the other architecture were built later), its base was chosen in the mountains. Thus, its overall layout was adjusted to adapt to its site. At the same time, the monastery presents the characteristics of the freestyle layout that followed this outline.

Figure 7. The regional formation of the mandala-style spatial layout at the macro level.

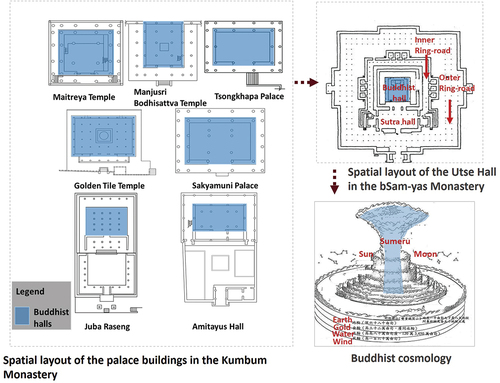

At the micro level, among the 12 cases, seven (six Grand Halls of Buddhas and one Buddhist college) are set up with the statue of the Buddha or sacred objects at the center of the inner sanctuary, and the floor plan indicates a distribution around the central sanctuary. This layout was frequently used in the main halls of monasteries in Lhasa, such as the Utse Hall, the main hall of the bsam-yas Monastery. This layout follows the Buddhist concept of space (Chen Citation1999; Dun Citation2020). In Buddhism, the center of the universe is Sumeru.Footnote7 Because monasteries are the material carriers of the universe, the main hall is the material carrier of Sumeru. (Long Citation2016; Dun Citation2020). To a certain extent, the construction of the Kumbum Monastery imitated the Four Great Monasteries of Lhasa (La Citation2001). In this sense, then, the layout centered on the main hall/sacred objects is a spatial translation of Buddhist cosmology ().

Figure 8. The regional formation of the mandala-style spatial layout at the micro level.

The centripetal spatial layout is also consistent with the typical regional dwelling style in Qinghai, named zhuangke.Footnote8 This vernacular architecture is a quadrangle courtyard formed during the Han Dynasty (202 B.C.–220 A.D.) as a result of the dwelling style and construction methods of the Central Plains (Cui et al. Citation2012). This style was introduced when a large number of Han immigrants and craftsmen moved to the eastern part of Qinghai due to the emperor’s decision to reclaim farmland in the region. Therefore, it is a customary practice in Qinghai to enclose the building within a square wall.

4.1.2. The spatial enclosure elements

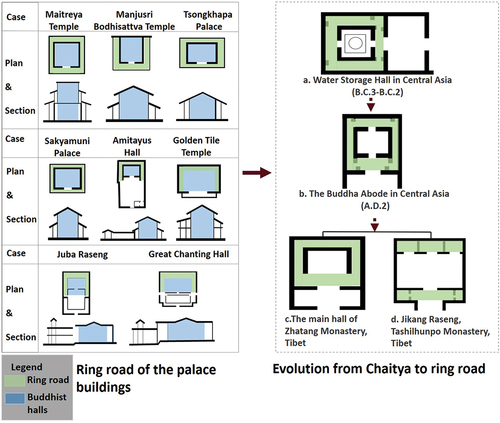

The spatial enclosure elements of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries manifest specific religious rituals and cultural contexts (Chang, Citation1992; Long Citation2016). Ring roads (both interior and exterior) are the most typical spatial enclosure elements of palace buildings in the Kumbum Monastery both at the macro and micro levels. The ring road is designed to provide a specific space for the rite of circumambulating in a clockwise direction.

At the macro level, the monastery is enclosed by a ring road that serves as the spatial and visual boundary of the complex. At the micro level, there is an interior ring road around the sacred objects at the center in five cases (three Grand Halls of Buddhas and two Buddhist colleges) and an exterior one in three cases (three Grand Halls of Buddhas). These roads provide venues for indoor and outdoor religious rituals. The Buddhist ritual of walking in a clockwise direction and the sanctuary space known as chaitya appeared in Central Asia around 2–3 A.D. (Chang, Citation1992).Footnote9 Because Tibetan Buddhism derived from the eastward spread of Buddhism, it also believes in the “reincarnation .” Moreover, Tibetan Buddhism was formed on the basis of the integration of Buddhism and indigenous religions. Because of this, it also believes in the idea that the universe has a cyclical structure and can be reincarnated indefinitely (Chen Citation1999). Hence, ring roads appeared in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and gradually became an indispensable spatial enclosure element. Typical examples are the ring roads built around Buddhist halls or sutra halls and those built inside the four main monasteries of the Gelugpa sect in Lasha (Chen Citation1999; Miao Citation2019). In the sixteenth century, as the number of monks and pilgrims swelled, the demand for indoor space also increased; consequently, the ring road was moved outside (Xu Citation2004; Long Citation2016). The three exterior ring roads of the 12 palace buildings in the Kumbum Monastery are also a product of limited indoor space. The typical spatial enclosure element was thus influenced by the Buddhist concept of the cycle of existence and its religious ritual, and it was adjusted according to each site’s conditions ().

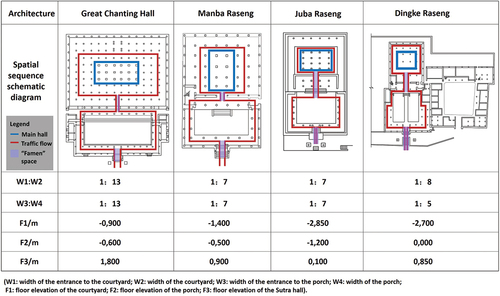

4.1.3. The spatial sequence

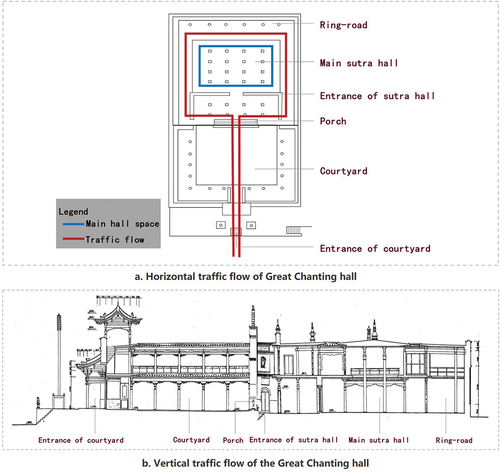

According to Tibetan Buddhist thought, the “pure land” (Sanskrit: sukhāvati) refers to the blissful world that believers yearn for and must be attained via the famen (the door in Buddhist philosophy). This concept should be embodied by the spatial sequence of buildings in monasteries (La Citation2001; Yang Citation2015). Of the 12 cases examined in the Kumbum Monastery, four Buddhist colleges present a linear structure (). The spatial sequence starts from the entrance into the courtyard and, after passing through the porch, continues to the main hall space, such as in the Great Chanting Hall (). The entrance space represents the initial approach to the main hall. Continuous spatial nodes with sudden changes in horizontal and vertical scale are set up at each entrance . This spatial sequence technique is influenced by the meaning of the “pure land” of the Buddhist kingdom through layers of famen (the initial approach to becoming a Buddhist).

Figure 10. The spatial sequence of the case studies, presenting a linear structure.

Figure 11. The spatial sequence of the Great Chanting Hall.

4.2. The architectural origins and the regional formation of the architectural forms

According to Tibetan Buddhist architectural design principles, the roof and other specific forms play an essential role (Long Citation2016). Therefore, the architectural origins and the regional formation of the architectural forms of the Kumbum Monastery’s palace buildings can be discussed in terms of two typical forms – roofs and arches – based on their specific style and location.

4.2.1. Roof forms

Of the 12 buildings selected, combined roofs are present in six (two Grand Halls of Buddhas and four Buddhist colleges). In terms of the combination of the elements, mainly Tibetan flat roofs, gilded roofs, and gable and hip roofs were included. Of these, the gilded roofs appeared in the Tibetan Buddhist Gelugpa sect monastery buildings in Tibet during the seventeenth century (Chen Citation1999; Xu Citation2004). In the Kumbum Monastery, they began to appear in the 1711 expansion project of the Golden Tile Temple, whose form is similar to that of the golden dome of the Potala Palace in Lhasa (). Another example is the Great Chanting Hall, whose roof is a double-layered wooden structure connected to the gable and hip roof of the front porch and a Tibetan flat roof, thus exhibiting complex shapes ().

Figure 12. The roof forms of the golden tile temple.

Figure 13. The roof forms of the great chanting hall.

In terms of the combined techniques, after sorting the data according to the monastery’s construction history, we can determine that the craftsmen responsible for roof construction were mainly Han and Tibetan. “decorativism” prevailed in the Central Plains during the Qing Dynasty (Sun Citation2002), after which the practice of combining various roof forms emerged. The architecture built during Period II in the Kumbum Monastery combine the elements of the Tibetan roof form and the Han-style buildings to achieve the localized expression in question.

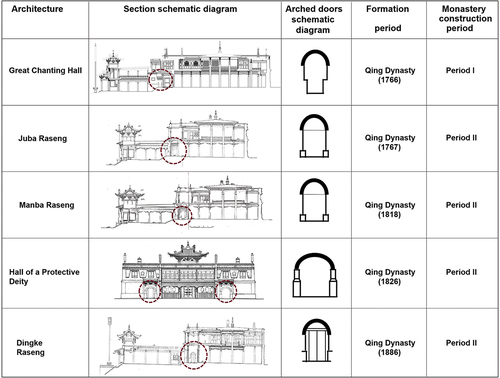

4.2.2. Arched doors

Among the 12 selected buildings, there are six arched doors in five cases (one Grand Hall of Buddhas and four Buddhist colleges) (). Based on historical information, all the arch components were built by Hui craftsmen in Qinghai during Periods I and II. However, previous studies have shown that China’s masonry arch coupon system (Yang Citation2009) originated in the ancient Sogdian region (Wubuli Citation2013). Moreover, the Hui are not indigenous to Qinghai. Their ancestors were east Iranians, Persians, and Arabs from East Asia, who arrived in the region via the Silk Road (Cui Citation2016). Therefore, the architectural culture of East Asia, especially the form of the arch, was introduced to Qinghai with these migrants and was gradually incorporated into the long history of the Kumbum Monastery’s construction.

Figure 14. The arched doors of the palace buildings.

4.3. The architectural origins and the regional formation of the construction technology

Based on the functional and physical characteristics of the structure, the architectural origins and the regional formation of the construction technology of the palace buildings are discussed by examining the load-bearing structure and its proportions.

4.3.1. The load-bearing structure

The load-bearing structure used in the five Grand Halls of Buddhas built in Period I is a beam-lifting structure, while that of the three cases built in Period II combines the chazhuzao (inserted columns) method to connect and reinforce the upper and lower layers of the building.Footnote10 Meanwhile, the historical data on the construction process indicates that the craftsmen in charge of the buildings’ wooden structures were mainly Han.

At the time, the central government of the Central Plains sought to revive traditional Han culture. It aimed to weaken the Mongolian culture, which dominated during the previous (Yuan) dynasty and restore and apply the column grid invented in the Song Dynasty. Among these construction methods and regulations, the beam-lifting structure and the chazhuzao are two widely used structural technologies (Pan Citation2001).

The central government also organized a large number of migrants to move to the north and develop the war-torn areas. These included the Hehuang Valley of Qinghai where the Kumbum Monastery is located. It was at that time that traditional Han culture was introduced to the area and to the building technologies of the Central Plains. As a result, the architectural style of the Yellow River Basin became similar to the structural technologies of the Central Plains, affecting the load-bearing structure of the Kumbum Monastery built in the same period. Based on what we know, the load-bearing structures of the eight Grand Halls of Buddhas built in Periods I and II are consistent with the contemporaneous Han-style architecture of the Central Plains.

Concerning the Buddhist colleges, the load-bearing structure of the four selected buildings built in Period II was made of stone and wood, meaning that the external stone walls and the internal beams and columns bear the weight simultaneously. The main hall is a structure with dense beams and a flat roof. The walls are built with concealed columns that correspond to the column network in the hall to support the load. The outer walls are made of thick bricks and adobes. The craftsmen in charge of the woodwork were mainly Han, while those in charge of the masonry were mostly Tibetan. This arrangement is consistent with the load-bearing construction method of other Tibetan monastery buildings (Xu Citation2004).

4.3.2. The structural proportion

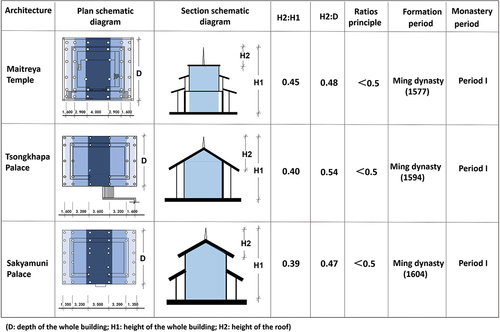

The structural proportion will be discussed separately for the two types of buildings, namely, the eight Grand Halls of Buddhas and the four Buddhist colleges. In terms of the architectural proportion of the grand halls, three selected buildings that were entirely built in Period I follow similar rules, that is, the width between the two pillars in the middle of the plane is less than or equal to 5 m, and the dimensions of the pillars next to it decrease progressively. These rules follow the construction principles of the traditional architecture of the Central Plains (due to the Ming Dynasty’s immigration policy) and those introduced by the Han immigrants from the same area (1368). The other five selected buildings from Periods II and III do not reflect these obvious rules. Moreover, regarding the total height of the building, in eight cases, the proportion of the roof height to the total height and to the depth of the building does not conform to the architectural practice of the Central Plains, according to which the total height of single-story halls is generally kept below 12 m. In halls with three or four depths, the roof height accounts for half of the building’s depth; the roof only accounts for a quarter or a third of the total height (Sun Citation2002). There appears to be no obvious regularity except in the Tsongkhapa Palace ().

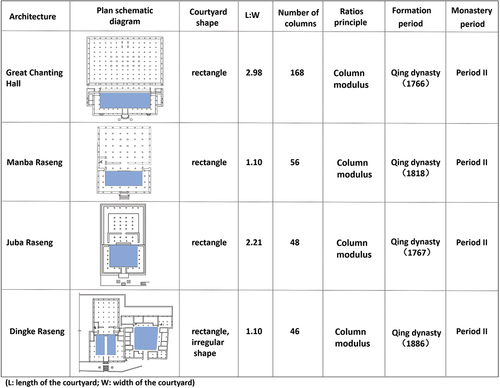

Regarding the Buddhist colleges, the main hall and inner courtyard of the four cases in question all show a rectangular approach consistent with the approach used in important buildings in the Central Plains of the Qing Dynasty (Sun Citation2002). However, this approach does not comply with the rule that the proportion of the long and short sides is 2:1. Furthermore, the hierarchy of the four Buddhist colleges is represented by the number of pillars in the palace (the higher the number, the higher the hierarchy) (). This building hierarchy can be seen in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries as early as the Yuan and Ming Dynasties (Chen Citation1999; Zhang Citation2016; Liu and Han Citation2021). This structural proportion is found in the four Buddhist colleges of the Kumbum Monastery because of the Qing Dynasty’s policy of allowing only the Gelugpa sect’s development in 1638 and the canonization of the sect in Qinghai in 1723.

Based on the findings above, both the eight Grand Halls of Buddhas and the four Buddhist colleges achieved localized expression of Han-style architecture by following a general approach rather than specific numerical proportions.

4.4. The architectural origins and the regional formation of the decorative elements

According to the number and density of decorative elements, the analysis is carried out on the three main parts of the walls, doors and windows, roofs, and corridors.

The walls include different combinations of Tibetan, Central Plains Han-style, Inner Mongolian, Qinghai, and Central Asian decorative architectural elements. The walls are decorated in a ternary form: a stone wall or a brick wall foundation in the lower part; a white and red adobe wall or a bricklaying wall in the middle; and a frieze, a red-striped side wall, or a tiled ridge in the upper part. In terms of the color of the wall decorations, the plinth of the Tibetan walls is laid with blue bricks, while the middle part is whitewashed with white or red paint. The exterior eaves adopt the frieze style or are painted red. As for the brick walls in the Central Plains, the lower part is laid with blue bricks, the middle part with green glazed or vermilion bricks, and the upper part with cinereous tiles. In the zhuangkuo wall in Qinghai, the lower part is laid with earth-colored bricks, the middle is painted white, and the upper part is decorated in red.

The door and window decorations mainly contain Tibetan and Han-style elements. Among them, the Tibetan gateways are usually triple gateways or five gateways, which refer to the “Triple Gateways of Liberation”Footnote11 and the “Five Paths,”Footnote12 respectively. The door lintel is decorated in four layers from top to bottom and incorporates different levels of decorations, such as lion heads, cantilever panels, cantilever beams, or rafters. The window decorations are mainly on the eaves. Meanwhile, the windows and doors are decorated with the lotus design and drapery,Footnote13 which provides shade from the sun and protects the painted windows and doors from erosion.

The decoration on the roofs combines Tibetan, Han-style, and Qinghai elements. The above-mentioned decorative materials are combined based on different roof types (flat roof, gilded roof, saddle roof, and gable roof). Among them, certain typical Tibetan-style elements, including precious vases, turrets, makara (a water monster shaped like a turtle), finials, dharmachakra (the golden wheel), and sleeping deer, are used to decorate the flat roof and the gilded roof. Underneath the golden eaves are the Han-style eave tiles, while below the eaves we find the wavy shape of the Qinghai topography.

The saddle roof and the gable roof are Han-style tile ridges; the eaves have cloud-shaped edges and lotus flowers. The ridge of the palace roof is equipped with precious Tibetan vases, turrets, the Buddha spraying flames, and makara gargoyles (the head of the legendary turtle monster), which are placed on the four corners of the saddle roof with golden tiles.

The corridors are decorated with Tibetan, Han-style, and Inner Mongolian elements, that is, a combination of different pillars, hall murals, scripture tubes, and colored silk ceilings. The above-mentioned decorations are combined according to the locations (corridors and eaves gallery), forming a space that shows the religious concepts and stories of Tibetan Buddhism. The pillars in the corridor are decorated with wooden carvings, and the corridor walls display a large mural of the Buddha.Footnote14 The tops of the pillars are painted, and the walls are drawn with large murals, showing traditional Tibetan auspicious patterns, such as the Mongol driving a tiger.Footnote15

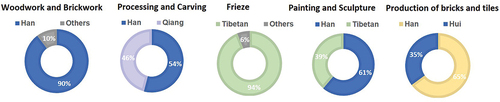

To further explore the origin and formation of these decorative elements, we can draw on information and texts regarding the monastery’s construction history. The analysis shows that there is a long-term one-to-one correspondence between the craftsmen of each type of work and certain ethnic groups: the Han were mainly engaged in woodwork and brickwork; the craftsmen responsible for processing and carving were Han and Qiang; the masons who built the friezeFootnote16 were mainly Tibetans; the artisans engaged in painting and sculpture were Han and Tibetan; and the potters engaged in the production of bricks and tiles were originally from the Han and Hui ethnic groups ().

These craftsmen of different nationalities introduced the construction techniques of their cultures and original settlements into the Kumbum Monastery’s palace buildings. For example, the wall decorations appeared mainly during the Qing Dynasty due to China’s closed-door policy that started with the Ming and Qing Dynasties, when foreign cultures were resisted. The architectural culture of the Central Plains is therefore hardly affected by foreign cultures but continued the Song Dynasty’s ethos and revived ancient traditions. The economic development of the Central Plains during the Qing Dynasty (1713–1847) gave rise to the aesthetic tendency of “decorativism,” thereby promoting the development of craftsmanship. Furthermore, a large number of handmade architectural decorations appeared at this time; decoration methods increased dramatically and different techniques were closely exchanged (La Citation2001; Sun Citation2002). With support from the Qing Dynasty, during which the Gelugpa sect fully developed, the monastery’s palace buildings were also influenced by the Central Plains’ decorative aesthetic.

The reason for this phenomenon lies in the local history. From the Warring States Period to the Qing Dynasty (475 B.C.–1912 A.D.), about 20 ethnic groups lived in Qinghai independently of each other according to ethnic composition. Craftsmen’s skills were passed down orally. Therefore, language differences and the independence of the settlements gave rise to long-term correspondence between different types of work and ethnic groups. This situation affected the Kumbum Monastery’s decorative elements.

5. Conclusion

Based on the findings above, the originality and construction methods of the Kumbum Monastery can be summarized using the concepts of hybridity and adjustment.

Hybridity refers to the monastery’s originality and construction methods, based on the premise of following the spatial concept of Tibetan Buddhism, while taking traditional Tibetan monastery architecture and Han-style architecture from the Central Plains during the Ming and Qing Dynasties as its main motifs. This hybridity is reflected in the spatial layout, the enclosure elements and sequence, the roofs forms, arched doors, and decorative elements. This happened in the context of religious dissemination, political integration, and the development of transportation and commerce as well as architecture from Indian temples, archways in Central Asia, and residential buildings in Qinghai. Decorative elements from Mongolian architecture were also introduced and mixed with local architectural forms and decorative means to express their significance, while reshaping the architectural icons and spatial meaning of the Kumbum Monastery.

Adjustment comprises two levels of content. First, Tibetan architecture was applied via localization through a spatial layout and structural construction based on the translation of the Buddhist concept of space in combination with regional and site-specific characteristics. Second, by following a general approach, instead of obeying specific structural proportions, appropriate adjustments were made to achieve a localized application of the Han-style construction system of the Central Plains during the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Furthermore, this paper reviewed the relevant historical and cultural backgrounds to understand the development of the Kumbum Monastery’s architecture. The monastery’s preliminary spatial configuration was a result of religious dissemination, ethnic migration, sociopolitical integration, and trade and transportation that took place during Period I. The complex multicultural nature of the architecture was also a product of this history. The Buddhist colleges were gradually completed as a result of the social politics of the Qing Dynasty, influenced by local economic development and ethnic integration in the region. The monastery’s complex multicultural architecture matured during Period II. From the end of the Qing Dynasty to the birth of the Republic of China, with the transfer of power and the change in religious policies that accompanied this event, the focus of the Kumbum Monastery turned to its economy rather than its construction. Some activities focused on restoration. The multicultural building complex was also maintained during Period III. To conclude, the development and evolution of the Kumbum Monastery’s architecture reflect the localization of foreign religions and the multiculturalism of Qinghai ().

Figure 18. The architectural characteristics of the palace buildings of the Kumbum Monastery.

Figure 19. The architectural localization and evolution of the Kumbum Monastery.

This article takes architectural culture as the starting point to provide a new approach for the study of the Kumbum Monastery’s architectural history. However, due to the limited permission to survey, data on the Living Buddha Mansion could not be collected during the field investigation. A second limitation of this article is the lack of comparison with other Gelugpa monasteries in Qinghai province, which future research should address.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jing Zhang

Jing Zhang, Lecturer, postdoc, Ph.D.,Research interests: Architectural history and Cultural heritage preservation.

Yunying Ren

Yunying Ren, Professor,Ph.D.,Research interests: Cultural heritage preservation and Urban planning.

Notes

1 The later period of Tibetan Buddhism refers to the renaissance and development of Tibetan Buddhism from the end of the tenth century to the beginning of the thirteenth century.

2 The Lianju Pagoda was the first pagoda built in the Kumbum Monastery to commemorate Tsongkhapa.

3 The emperors of the Ming Dynasty conferred titles to many leaders of religious sects and invited them to participate in the government of Tibet.

4 In 1652, the emperor of the Qing Dynasty established the regency system in Tibet. He appointed the Gelugpa sect to be the leader among the various sects of Tibetan Buddhism and acquiesced to the conversion of other sects to the Gelugpa sect.

5 The Golden Tile Temple was preliminarily built in 1622 (Period I) and reconstructed in 1711 (Period II).

6 A mandala is a design that expresses Buddhist philosophy.

7 Sumeru, also known as World Mountain, is the center of the universe in Buddhist cosmology.

8 This style is particularly popular in the eastern part of Qinghai, including 11 counties and cities in the Yellow River and Huangshui basins.

9 Chaitya refers to a worship space that can be surrounded by various Buddhist holy sites (such as the duo slope, Buddha statues, sacred trees, and inscriptions).

10 Chazhuzao refers to the structure of the pavilion-style architecture of the Qing Dynasty. The upper eaves column had a cross or a single opening at the bottom of the column. The fork fell on the lower floor at the center of the flat paving. The bottom of the column was placed on the paved bucket surface.

11 The Triple Gateways of Liberation refer to the Buddhist belief that there are three ways of moral cultivation: emptiness liberation, unconditional liberation, and desireless liberation.

12 The Five Paths refer to the five ways to relieve pain and alleviate troubles: accumulation, preparation, insight, meditation, and the path beyond learning.

13 In Tibetan architecture, the engraved lotus petals and concave-convex (the monster) symbolize the accumulation of Buddhist texts.

14 One of the typical Tibetan paintings, specifically referring to the murals in the halls and the porches of a monastery.

15 This image is believed to prevent the plague and bring good luck. It is a typical theme in Tibetan Buddhist murals.

16 A frieze is a low wall made of tamarisk branches on the edge of the roof in Tibetan architecture.

References

- Bo, J. 2006. “Research on Traditional Regional Architectural Culture in Gansu.” Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunnan and Tibet (Thesis). University of Tianjing.

- Chang, Q. 1992. The Civilization of the Western Regions and the Changes of Chinese Architecture. Changsha: Hunan Education Press.

- Chen, Y. D. 1999. Tibetan Architecture in China. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Cui, M. M. 2016. “Study on A Brief Account of the Origin of the Hui Nationality in Qinghai.” Thesis. Qinghai Normal University.

- Cui, W., J. Wang, B. Yue, and Y. Li. 2012. “A Study of the Renewal Model of Traditional Houses in Multi-Ethnic Areas—Taking the Example of Zhuangkuo in the Hehuang Area of Qinghai Province as an Example.” Architectural Journal 11: 83–87.

- Deng, C. L. 2016. Tibetan Monastery Architecture. Lhasa: Tibetan Ancient Books Press.

- Dun, L. 2020. “Analysis of the Examples of Han-Tibetan Architectural Cultural Exchanges in Temple Records.” Journal of Tibet Studies 04: 122–125.

- Jiang, H., and Z. Liu 1996. “Qinghai Kumbum Monastery Renovation Project Report.” Beijing: Cultural Relics Press

- La, K. Y. 2001. The History of Kumbum Monastery. Beijing: Ethic Press.

- Liu, T., and Y. Han. 2021. “The Plane Shape of the Tibetan Three-Phase Palace with Dugang as the Main Part.” Huazhong Architecture 39 (7): 111–116.

- Long, Z. D. J. 2016. Research on the Architectural Culture of Tibetan Buddhist Temples. Beijing: Social Science Literature Press.

- Miao, M. L. 2019. “A Study on the Decorative Patterns of Tibetan Buddhist Monastery Architecture.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 7 (4): 355–361. doi:10.4236/jss.2019.74028.

- Pan, G. X. 2001. The History of Ancient Chinese Architecture (Yuan and Ming Dynasty). Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Pu, W. C. 2014. Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Qinghai. Lanzhou: Gansu Ethic Press.

- Ran, G. R. 1994. Tibetan Buddhist Temples in China. Beijing: China Tibetology Press.

- Su, B. 1996. Tibetan Buddhist Temples Archaeology. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press.

- Sun, D. Z. 2002. The History of Ancient Chinese Architecture (Qing Dynasty). Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Wubuli, M. 2013. “Study on the Architecture of Xinjiang Section of the Silk Road.” Thesis. Tsinghua University.

- Xu, Z. W. 2004. Guidelines for Tibetan Traditional Architecture. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Yang, G. M. 2009. Kumbum Monastery. Xining: Qinghai Republic Press.

- Yang, G. M. 2015. Architectural Art History of the Tar Temple. Beijing: China Nationalities Press.

- Zhang, P. J. 2016. “A Study Of the Classification of Palace Halls of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Inner Mongolia Based on the Development of the Dugang Ceremony.” Journal of Architecture 2: 95–100.

- Zhu, P. X. 2006. “Study of the History, Culture and Geography of Tibetan Buddhism in Qinghai.” Thesis. Shaanxi Normal University.