ABSTRACT

The early industrial heritage of Anshan Steel Works is not only an important contested heritage to the spread of technology after the world industrial revolution, but also a typical representative of “passive receiving” the modernization of Chinese architecture. This research analyzes the colonial construction institutions and their technicians’ construction activities, professional backgrounds and ideology in different development stages through the historical staging of the construction of the Japan-ruled Anshan Steel Plant and city streets from 1916 to 1945, interpreting the power and construction process of Anshan, a unique industrial-dependent colonial society and urban space.

Graphical Abstract

1. Research background

The victory of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 entitled Japan to the governance right of the leased territories in Lvshun, Dalian, and the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER), which unveiled Japan’s forty-year colonial rule and construction in northeastern China [Manchuria]. Thus, colonialism has become a significant political driver for the modernization of cities in Northeast China. With the rich iron ore resources and superior geographic transportation in Anshan [Jp. Anzan], the Japanese imperialists decided to build the Anshan Iron Works [Cn. Anshan Zhitiesuo; Jp. Anzan Seitetsujo] in 1916, which was taken over by the Showa Steel Works [Cn. Zhaohe Zhigangsuo; Jp. Showa Seikojo] in 1933 to meet growing Japanese demand for steel. Anshan, therefore, became an important industrial and mining city in Manchuria.

To better rule the colonial regions, Japanese architects, with the construction organization of the South Manchuria Railway Company [SMR] as the core, took the initiative in the colonial urban planning and architectural design of the so-called Manchurian Railway Zone. They took Manchuria as a pilot area to practice western modernist architectural ideas and technologies (Yasuhiko Citation2009). Just in this colonial context of “passive receiving”(Xu Subin Citation2020, 97), the Anshan Steel Works, as well as the Anshan Zone settlement’s urban planning, were designed and implemented gradually.

1.1. Modernization of colonial architectural organization

The development of architecture and civil engineering organizations constitutes a crucial subject in the study of modern history. On the one hand, the architectural historian, Nishizawa Yoshihiko (Citation1996), pointed out that the colonial technical institutions, as a communication medium, introduced the culture of the suzerain state and the Western modernist knowledge system into the construction of colonial cities. Meanwhile, the research emphasized the critical media role played by external recruitment, overseas study, and colonial architects in technology transplantation and development against the modern social background of China and Japan (Sha Citation2001; Xu Subin Citation1991). On the other, based on the historical analysis, historical researchers found that the development of occupations and professional groups composed part of the process of state formation (Macdonald Citation1999, 100; Collins Citation1990, 11). Xu Xiaoqun (Citation2001, 23) considered the establishment and development of the Shanghai freelance group in the early 20th century as a standard to measure China’s modern transformation. In his research on the formation of colonial occupational groups, British scholar Terrence J.Johnson (Citation1972, 39), proposed that the colonial government often invested more in the management of occupational groups and the formulation of occupational systems than the suzerain government, thereby taking better control of the colonial society and concealing their political intention in the name of “professionalism.”

This phenomenon and standard also apply to the modern transformation of Manchuria in the first half of the 20th century. To better serve the colonial rule through urban modernization, Japanese colonists established many official institutions and technological associations that engaged in technical rule formulation, theoretical research, and design practice in Manchuria, including the SMR’s architecture section, the Civil Engineering Department of the Guangdong Government-General, the Manchurian Architectural Association, and the Manchurian Civil Engineering Association (Yasuhiko Citation1994, Citation1996). These architectural organizations and technicians served as a major driver for the modernization of Manchuria cities and buildings, providing services for the colonial government by advancing urban planning, railways, factories, housing, medical care, education, and other urban projects (Bao Citation2016).

The increasing expansion and specialization of construction organizations and technicians also verified the development and mission of urban evolution in another way around (Lzumi Citation2014; Moore Citation2013). For example, after inspecting the previous organizational transformations of the Manchurian Construction Association, Chen Chien-Chung (Citation2017, 28) believed that there is a clear correspondence between the development of associations and changes in colonial political purpose. From this perspective, it seems that the construction of the Anshan Iron Works and the city has provided significant research material for further exploration of the process in which a colonial city at the local level was built by architectural organizations and technicians during the colonial time.

1.2. Colonialism and contested heritage: reconstruction of the heritage value of Anshan Steel Works

The study of colonialism reveals how modernity exerted its significant implications on colonial planning. As Tani Barlow (Citation1997, 1–20) said, when it comes to the interpretation of “colonial modernity,” colonialism and modernity are inseparable. Regarding the relationship between colonial architecture and modernization, architectural historians focus on the inspection of the relationship between urban architectural styles, technologies, ideas, and colonial policies and social development, aiming at clarifying the process of colonial modernization by analyzing the innovation of materials, spaces, and systems (Bao Citation2016; Matsusaka Citation2010). Akira Citation1988) and Bill Seweel (Citation2019) described how Japan built a modern colonial empire in Manchuria from four perspectives of planning, architecture, economics, and social structure. Other scholars, including Mark Driscoll (Citation1999), Wang Jing (Citation2018), and Faye Yuan Kleeman (Citation2003), depicted how Japanese colonial expansion was reflected in the construction of colonies, such as Taiwan and Manchuria, through the narratives of Japanese colonial literature in the first half of the 20th century, and discussed the relationship between Japanese colonial projects and modernity.

When the Japanese government promoted the application of “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” for world cultural heritage in 2014, China, South Korea and other countries strongly opposed it, which triggered discussions on the value interpretation and protection of “contested heritage” or “dissonant heritage” in East Asia (Nobuo, Subin, and Ruoran Citation2016, 397). As the remaining “dissonant heritage” during the Sino-Japanese War, we urgently need a comprehensive evaluation and interpretation of the value and history of Anshan Steel Works so as to arouse public thinking and empathy and give play to the warning role of the heritage for the future. The research on “dissonant heritage” was first started by Ashworth and Tunbridge (Citation1996, 21). They recognized the controversial nature of heritage, believing that the essential reason for dissonant heritage lies in that the value of heritage is created by interpretation. Not only does it include what to interpret but also how to interpret and who to interpret. At present, the research on contested heritage mainly focuses on three parts: historical research, value cognition and interpretation strategy (Harrison Citation2013; Smith Citation2006; Battilani, Bernini, and Mariotti Citation2018). Through a systematic review of heritage research, Liu Yang summed up the inherent characteristics and decision-making methods of contested heritage and stressed the importance of considering cultural diversity and multi-stakeholder participation in dealing with contested heritage (Yang, Karine, and Xin Citation2021). “Historical England” provided guidelines for the handling of “contested heritage”, arguing that it is necessary to recognize the value of heritage from multiple angles after understanding the true historical appearance and provide thoughtful, lasting and forceful reinterpretation (Historic England Citation2021).

The current discussion on the heritage value of Anshan Steel Works has long focused on modern industrial history, with little attention paid to its architectural planning history research. Xie Xueshi and Zhang Keliang (Citation1984) introduced the site selection and plant construction of Anshan Iron Works and Showa Steel Works in the Anshan Iron and Steel History(1909–1948). However, the deprivation of local subjectivity has led to the prolonged absence of research concerning the modern Anshan construction from the Chinese architectural history study. Only Wang Li (Citation2010) has focused on describing and investigating necessary historical materials and examples based on macro studies of the general history framework.

In October 2019, the Chinese government announced that the early buildings of the Anshan Steel Works are listed in the eighth batch of China’s key cultural relics protection.Footnote1 The selected heritage includes the Showa Steel Works Office Building, the No. 1 blast furnace, and other industrial sites with colonial marks, as well as other ethnic ruins built in the First Five-Year Plan of New China, such as the No. 2 sintering workshop and Seamless Steel Tube Plant. Colonial modernity was constructed without a subject. Hence, whether there is any preservation for colonial heritage or not greatly challenges the influence and construction of the colonial architectural history (Hsia Citation2020, 88–89). Because of others’ invasion, the modern Anshan has suffered a long-term separation of the subject and the object in construction. To strengthen the continuous collective memory of the subject and the architectural heritage with the characteristics of the Chinese community, reflective and critical thinking is required on the identity and purpose of the colonial planners and builders at that time and their construction of the colonial city space. Furthermore, objective environment creation and subjective memory should be combined in terms of preserving the physical aspect of the heritage, to reinforce the perception of the colonized contemporary society over the exploiting nature of the colonial class in history.

2. Research focus and methods

Anshan, as an industrial and mining city completely independently planned and constructed by the Japanese after its invasion, constitutes a crucial example for exploring the colonists’ design intentions. The thesis adopts a diachronic comparative research method to compare the construction activities, architectural organizations, and technicians and their ideology in different periods in the same city, thereby deeply exploring the complex historical motives and purposes behind the formation of urban space. It should be noted that the technicians referred to in this article mainly refer to the technical bureaucrats and technicians who work in architectural design, urban planning, and civil engineering. Most are Japanese, while those engaged in basic labor are Chinese laborers. Much of the research material was sourced from Japanese records, including official documents, academic journals, and popular sources such as newspapers and memoirs, a major feature of colonial architectural history. As a new city established by Japanese colonists, Anshan’s construction process not only illustrated the complexity and diversity of urban development in modern China, but also demonstrated the construction path and mechanism of colonial cities driven by industrial-dependent colonialism.

3. Initial stage (1916-1923)

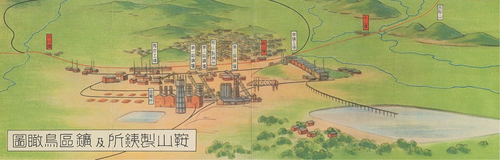

In the first phase, SMR basically completed the purchase of the mining and land in Anshan, and the planning and construction of an industrial and mining city with factories in the northwest and residential in the south began to take shape (). The phase ranged from the establishment of the committee of Anshan Iron Works to the near completion of the construction in 1923.

Figure 1. Map of Anshan in 1918. Map from Chizu (Shiryo Hensan Kai Citation1986), 30.

3.1. Changes in the construction administration

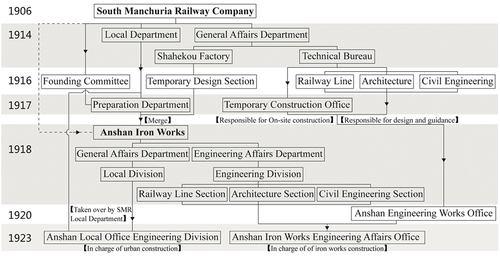

In September 1916, the SMR set up a Temporary Design Section in the Shahekou Factory in Dalian,Footnote2 and the Founding Committee for the Ironworks was established in December. The two were in charge of the preparatory for the construction of the Anshan Iron Works. In March of the following year, the Anshan Plant Preparation Department, headed by Hatta Ikutaro, the engineer of the Imperial Steel Works, replaced the committee, being responsible for land acquisition, management, and staff training (Azawa Citation1940, 2). In April, the General Affairs Department of the SMR set up the Temporary Construction Office, with Sato Ojiro as the director, under which the Railway Line Section, Civil Engineering Section, and Architecture Section were established to be responsible for the construction and supervision of railways, civil engineering, and water supply (Masuda Citation1976, 241–243). Shahekou Factory Design Section was renamed as the Temporary Construction Section in July, responsible for the equipment and materials procurement, and merged with the Anshan Factory Preparation Department in March 1918 to establish the Anshan Iron Works, becoming an independent business department directly under the President’s Office of SMR. In May 1918, the Anshan Iron Works made a formal decision to establish the Engineering Division. Under the division, there was the Civil Engineering, Architecture, and Railway Line Section in charge of the material and machinery procurement, on-site construction, and repair of the Works (Manshikai Citation1965, 614).

The design and planning of the early factories, company apartment houses, railways, and civil engineering facilitiesFootnote3 of the Anshan Iron Works were directly designed and guided by the technical bureaus of the General Affairs Department.Footnote4 In 1917, the General Affairs Department found the Temporary Construction Office as a temporary organization for the construction management of Anshan engineering (Mantetsu Sosai Shitsu Chihobu Zammu Seiri Iinkai Citation1977, 433). The Anshan Engineering Works Office was formally established in February 1920, and handed its construction authority over to the Anshan Iron Works in 1923. Meanwhile, the Anshan Iron Works Engineering Affairs Office was established to take complete charge of the civil and construction of the Works ().

Anshan Iron Works had certain jurisdiction over the operation of Anshan urban facilities in early times. Its subordinate organization, General Affairs Department, took charge of the Local Division. By April 1920, the Local Division affairs of the Steel Works were handed over to the SMR’s Local Department. An investment of 7.93 million yen of the SMR for the civil and engineering facilities, residential buildings, etc., was transferred to the Local Department (Azawa Citation1940, 331). The Anshan Local Office of the SMR formally came into being in May 1923, with Yoko Tata Kisuke, the former head of the General Affairs Department of the Steel Works, as its first director. The office had a Division of Engineering,Footnote5 in full charge of the construction of Anshan city street civil engineering, water, and sewage, marking the formal separation of the Steel Works from the management and construction rights of the city.

3.2. Early construction led by the SMR technology bureau

As recorded in the Forty-Year History of Manchuria Development, the construction plan of the Anshan Iron Works during this period was mainly led by staff from the SMR’s architecture Section, including Onogi Takaharu (), Yokoi Kensuke (), Aoki Kikujiro, Yuge Shikajiro, Kariya Tadamaro, etc. Yasui Takeo and Ono Takeo designed the residential buildings (Manshikai Citation1965, 614), and the construction was supervised by the on-site organization led by Oguro Ryutaro, Deriha Kiichiro, and Kariyazono Moriichi from the SMR’s architecture section (Deriha Citation1933, 68). The waterway was designed by Kato Yonokichi (), the director of the SMR’s civil engineering section, and the construction of the city was led by Sato Ojiro () with guidance offered by Onogi Takaharu (Koshizawa Citation1988, 56).

Figure 3. Onogi Takaharu. Source from (Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1933), 1–4.

Figure 4. Yokoi Kensuke. Source from (Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1942), 3.

The impact of the SMR’s architecture section on the Anshan Iron Works can also be verified from the changes in the business scope of the section. According to the SMR Construction Organization regulations, its business was limited to the construction and repair of residential buildings (Mantetsu Shomubu Chosaka Citation1928, 39). However, based on the memory of Kariyazono Moriichi, the construction supervisor of the Manchurian Railway Construction Organization, since 1918, the business scope of the architecture section has covered the construction of buildings such as sanitation, coal mines, iron making, hospitals, hotels, and employee houses (Kariyazono Citation1976, 266) . Additionally, it can be seen from the designer’s experience () that most of the technicians boasted construction of colonies experience in Japan, Taiwan, or Northeast China, and most of them graduated from the Department of Architecture, Technical College, Tokyo Imperial University. Among them, Onogi Takaharu is the most representative. His career had gone through a technician at the Governor’s Office in Taiwan, a director of the SMR Architecture Section and a private architectural firm. He is an important promoter of the modernization of the colonial cities in Manchuria.

Table 1. Background of the main technicians in the initial stage.

At this stage, due to the changes and conflicts of the jurisdiction of various departments within the SMR, the construction organization was operated in a disordered manner. However, the fundamental construction was still controlled mainly by the SMR Construction Department. After establishing the Anshan Local Office, the factory and city construction authority became more apparent, leading to unified economic, administrative, and construction powers.

3.3. The rise of real estate and building materials industry

The civil engineering projects of the Anshan Iron Works were all contracted by Japanese civil works contractors, for example, the Sugawara Works responsible for the site construction, the Ookuragumi responsible for the construction of the ironworks, the Yoshikawagumi responsible for the excavation of the water source, and the reservoir, the Iizuka Kotei Kyoku responsible for the basic construction of the blast furnace, and the Hazamagumi responsible for the railway branch line construction between the ironworks and the mine (Watanabe Citation1917). Other civil works contractors involved in the construction included Shikigumi and Kubotagumi (Okayama Citation1918). In terms of street construction, Takaokagumi took charge of the construction of the school, with Ookuragumi, Hasegawagumi, and Mitagumi responsible for the construction of employee houses. With extensive construction of colonies experience, these civil contractors were the first batch of civil works contractors established by Japanese colonists in Northeast China ().

Table 2. Overview of the Primary Civil Works Contractors in the Initial Stage.

Meanwhile, large-scale real estate companies controlled by Japanese consortiums emerged in Anshan, responsible for constructing and leasing the residential buildings used by the ironworks. For example, in 1918, the SMR commissioned Manchu Kogyo Co. Ltd, governed by Tokyo Tatemono Co. Ltd. (Tokyo Tatemono Citation1998, 50–75), to build 193 rental houses in Otowamachi and Suzukamachi. A total of 660 households were used as residential areas for senior employees, including the residence of the first director of the Anshan Iron Works. For the first time, SMR has commissioned large-scale real estate companies to build employee housing in accordance with SMR’s standards (Yasuhiko Citation2001, 93). In this period, other real estate companies included Kangde Real Estate Co. Ltd. and Anshan Real Estate Co. LtdFootnote6Footnote7 (Kogyobu Shokoka Citation1922, 170–177, Citation1927, 278–288).

Anshan also established many companies engaged in the production and trading of building materials, such as Manchu Kogyo Co. Ltd Anshan Bricks Factory (), Lishan Tile Factory, Anshan brick kiln Factory, and Anshan Building Materials Factory (Hirao Citation1939, 25–28; Teikoku Shokokai Citation1935, 185), which were responsible for producing bricks for the construction of civil buildings. The refractory bricks for the ironworks were manufactured and supplied by the Manchu Brick Kiln Industry Pilot Factory of the Dalian SMR Central Research Institute (Minamimanshu Tetsudo Kabushiki Gaisha Chuo Shikenjo) built in 1916.

After 1919, with the end of World War I and the outbreak of the global economic crisis in 1920, the iron and steel industry continued to hit a downturn. Anshan Iron Works, for its low iron content, failed to reduce the high cost and was confronted with the risk of suspending production. Furthermore, the construction of the city also remained to stagnate.

4. Recovery period (1923-1932)

In the second phase, Anshan Iron Works gradually stepped out of the shadow of the economic crisis after World War I and began the expansion plan centered on the construction of the concentrating plant. This phase was called “the revitalization of Anshan and the steel industry “ by Manshu Nichinichi Shinbunsha (Citation1923). The phase lasted from the expansion plan of the concentrating plant in 1924 to the establishment of Manchukuo in 1932.

4.1. The establishment of the dominant position of the Anshan Iron Works engineering affairs office

In May 1923, with the urgent need for steel by Japanese militarism and the solution of Anshan’s poor mine technology, Anshan, once known as the “death capital” due to its sluggish steel industry, began a new round of construction. The Ironworks Engineering Affairs office headed by Shioda Chuzo carried out a series of construction in the ironworks at this stage, and designed and supervised the third blast furnace cast iron plant, chemical experiment plant, member production group, and other additional construction. Architectural technicians in the department included Sako Ukichi, Bokura Atsuyoshi, Muta Masanao, Fujii Takeo, Tanaka He (Sako Citation1976, 214).

In September 1930, the Ironworks Engineering Affairs office was transferred to the Anshan Local Office for management by the SMR headquarters to integrate technical capabilities(Showa Seikojo Gyomuka Citation1934, 39). The Ironworks Architecture Section Director, Shioda Chuzo, returned to Japan, and the Section’s staff, Sako Ukichi, Bokura Atsuyoshi, Muta Masanao, Fujii Takeo, Tanaka He, etc., changed their work units from the Iron Works to the Engineering Affairs Office of Anshan Local Office, or other engineering offices such as Dalian and Fengtian(Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1930a, 73, Citation1930b, 77). The Anshan Local Engineering Division’s staff, Deriha Kiichiro, was transferred to the Dashiqiao Engineering Affairs Office.

In the following year, because of the contradiction between the Local Office and the Ironworks, as well as inconvenient communication, the Anshan Engineering Affairs Office was disbanded. Its director, Kariya Tadamaro, was transferred back to the SMR headquarters, and the director of the Section of Architecture Yamagata Kaichi was transferred to the Dalian railway office. The Engineering Affairs Office was re-administrated by the Ironworks, with the Section of Architecture and Civil Engineering under its administration. In this period, the improvement of the Anshan Local Office and the Ironworks significantly pushed forward the construction schedule of Anshan ().

4.2. The revival of the iron industry – construction of the concentrating plant

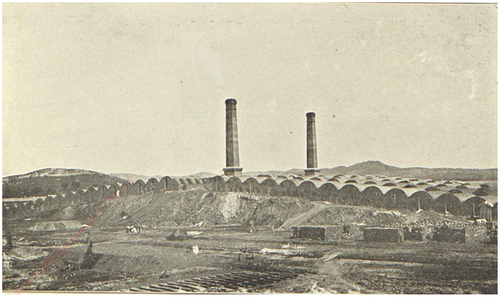

The construction plan of the Concentrating Plant of the Anshan Iron Works in 1923 is representative of the civil engineering undertakings of the Iron Works during the recovery period, marking the beginning of a new phase of construction. Due to the continuous low price of iron and steel, the disposal of Anshan’s poor iron ore has become an urgent task for iron production. In 1923, the lean ore treatment technology test developed by Umene Tsunesaburo, staff from the Temporary Research Department of the Iron Works Institute, succeeded. In October, the iron plant expansion plan was approved,Footnote8 led by Umeno Minoru (the famous Japanese civil and mining engineer), focusing on the Concentrating Plant and a total investment of 1.1 million yen. The Engineering Affairs Office of the Iron Works finished the construction drawings, allowing the construction to start in April of the following year (Umene Citation1927, 149–165).

Given the requirements of industrial processes and the site’s status quo, the Concentrating Plant was selected on Higurashiyama (), 1,200 meters away from the blast furnace. The construction of the factory was coordinated with the production flow lines and mountain-shaped undulations. The raw material feeding inlet was 55 meters above sea level, with the highest point being 66 meters, and the finished product outlet was 37.5 meters high (). The outlet consisted of crushing equipment, roasting reduction furnace equipment, concentrator equipment, briquette equipment, and conveying equipment, creating a steel-framed brick wall structure factory with a total area of 9,474.5 square meters (Adachi Citation1925, 529–542).

4.3. Urban construction – recovery of the private civil construction industry

During the recovery period, the city construction activities were characterized by increased public construction works designed by private architectural firms. Remarkably, after the SMR implemented the design agency commission system in 1925, many engineering projects of the SMR were entrusted to private firms. Among them, the SMR Anshan Hospital, designed by Dalian Onoki Yokoi Joint ArchitectsFootnote9 in 1927, was the most typical one (Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1928, 42). According to Takaoka Mataitirou, director of the Manchuria Architectural Association, the civil engineering of Anshan Hospital was completed by the Takaoka-Kudome Komusho, which was established in 1922 with Kudome Hirobumi, and it also responsible for the construction of the Anshan Power Plant (Takaoka Citation1933, 41). The joint venture company, Yamazaki Hidetake Komusho, established in 1926, was the representative of Anshan’s local construction office. Its founder, Yamasaki Hidetake, served as the representative of the Anshan Council of the Manchurian Architectural AssociationFootnote10 from 1924 to 1926 and from 1929 to 1930, with long-term service in the Anshan Institution (Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1924, 55). The Company acted as a designated contractor for SMR civil engineering works of ironworks, railways, and cities. Statistics showed that at least 17 private companies engaged in architectural design and construction in Anshan in 1932, and 11 companies engaged in the trading and manufacturing of building materials, bricks, wood, steel, hardware, water and electricity, and construction equipment. Thanks to these companies, the private civil construction industry has recovered in the construction of Anshan. But these companies were all founded by the Japanese, aiming at serving Japanese daily construction.

5. Climax period (1933-1945)

The third phase was marked by the establishment of Manchukuo and Showa Steel Works. In this stage, Anshan gradually formed clear urban functional zoning and completed the construction of colonial urbanization from an industrial plant area to the iron-smelting and steel-making industry. The phase began with the takeover of Anshan Iron Works by Showa Steel Works in 1933 and ended with Japan’s defeat and surrender in 1945.

5.1. Changes in the construction organization

The Manchu Nipposha introduced the construction of Anshan during this period with the title “Anshan March of Iron Capital,” which described the revitalization of Anshan (Manshu nippo Citation1933). With the official takeover of the Anshan Iron Works [Anzan Seitetsujo] by the Showa Steel Works [Showa Seikojo] in June 1933, and out of the political needs of urbanization after the establishment of Manchukuo [Ch, Manzhouguo; Jp, Manshukoku], Anshan ushered in the golden age of the civil engineering industry.

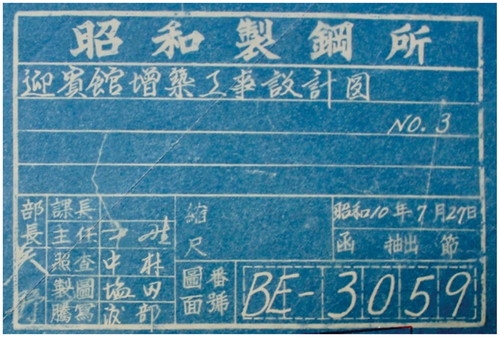

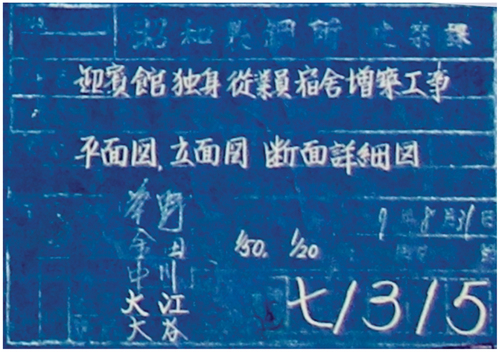

In June 1933, Showa Steel Works’ first divisional organization decided to change the former Ironworks Engineering Affairs office into the Engineering Affairs Office of the Department of Works, with the Section of Civil Engineering and Architecture was retained (), with Shishino as the director, and Guto and Tokatsu successively served as the heads of the Architecture Section (), being responsible for the design and construction of the Showa Steelworks Office and the Guest House (Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1934, 28).

In 1937, the Engineering Affairs office was renamed the Engineering Division of the Department of Works, employing KusanoYoshio (), a member of the Manchuria Architects Association and the architect of Yokoi Architect, as a special consultant. He worked in Anshan four days a week and was formally hired as the director of the Engineering Division in 1938 (Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1937, 37). Kusano himself was very skilled in the calculation of reinforced concrete structures and the design of large-span buildings. He was responsible for the design and construction of many factory of the Steelworks for 37 to 45 years, including the expansion project of the Showa Guesthouse, the affiliated hospital of the Showa Steel Works, the consumer cooperatives, and the martial arts field (Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1939, 8). In 1938, the Engineering Division was reorganized into the Civil Engineering Department of the Construction Bureau. In 1943, the Showa Steel Works was revoked and placed under the Manchuria Steel Corporation [Manshu Seitetsu Kabushiki Gaisha]. After the reorganization of the Civil Engineering Division, KusanoYoshio served as the deputy director (Showa Seikojo Gyomuka Citation1934, 39). In addition, the large-scale construction of Showa Steel Works’ affiliated companies also recruited many construction technicians, such as Fujiwara Koji from the Manchuria Sumitomo Metal Industrial Pipe Manufacturing Co. Ltd. and Tokuyama Hisato, the head technician of the Anshan Steel Co. Ltd.

Figure 13. Drawing Title of Staff Dormitory of Showa Guesthouse, 1942. Source from Ansteel Museum Collection.

From 1933 to 1937, the Engineering Division of the SMR Anshan Local Office was still in charge of the urban construction. According to SMR technician Fujita Sadao, under the guidance of Takimura Moritoshi (the head of the Engineering Division of the local office), KaiTsu Maru Hideo from Architecture Section, he, together with Nakajima Shigeshi, was engaged in the design and supervision of the Anshan Women’s Hospital, Higher Girls’ School, Fire Department, and a large number of residential buildings (Sadao Citation1976, 236). In 1937, with the SMR’s Local Department revocation, the power of the SMR was further weakened. Most of the technicians from the Engineering Division of the Anshan Local Office were transferred to the construction department of the railway bureau of the SMR. For instance, Takimura Moritoshi was transferred to the Dalian Engineering Affairs office, and Fujita Sadao to the Planning Section of the Construction Bureau of Fengtian Railway Administration.

The administrative power of the Anshan urban area was taken over by the Anshan Municipal Office of the Puppet Manchurian State. The former director of the SMR Anshan Local Office, Mieno Masaru, was appointed as the mayor. There were five divisions, including General Affairs, Administration, Health and Sanitation, Finance, and Engineering Works. In 1939, the Engineering Works Division was restructured into the Engineering Works Department, with the Management Division, the Urban Planning Division, and the Civil Engineering Division under its control. In 1940, the Housing Division was established under the Administration Department.

5.2. Busy architects and civil builders

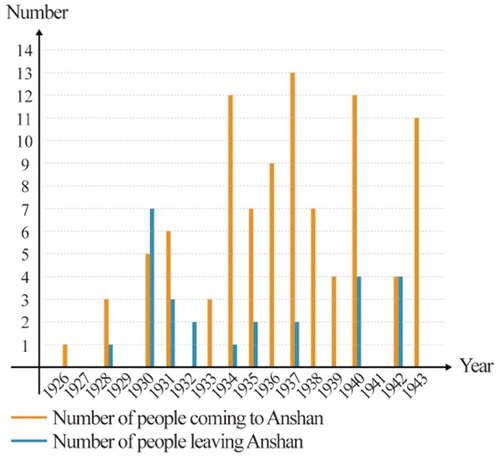

During the climax period, the personnel transfer of Anshan construction technicians showed two characteristics. First, the frequency of transfers increased. As shown in , with the dissolution of the SMR Anshan Engineering Affairs Office from 1931 to 1932, a large number of technicians were transferred from Anshan, and the population rose swiftly in 1933 and 1934. This trend indicates that the accelerated urbanization in Anshan has increased the demand for civil and building technicians.

Figure 14. The Personnel Transfer of members of Manchuria Architectural Association in Anshan, 1926–1943. Data from Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi.

The second characteristic lies in the change in the professional background of architects. Before 1933, the transfer of the members of the Manchuria Architectural Association in Anshan roughly took place as internal transfer within the SMR. After 1933, the proportion of association members working in private companies rose rapidly to more than 50%, and numerous private companies technicians rushed into Anshan. The change and increase in the number of architects with backgrounds were essentially the results of the development and expansion of Anshan urban. Furthermore, the increase of architects in private companies reflected the gradual change in the mode of dissemination of colonial ideas and technological systems, from the political enforcement of official colonial institutions to the introduction of private architects. As the SMR’s control over the Steelworks was squeezed and challenged by the military government and other chaebols, the Showa Steel Works became an independent legal entity, and the construction technicians of the Works Department were no longer transferred by the employees of the SMR. In 1932, 1933, and 1934, no SMR staff in Manchuria Construction Association Anshan Councilors proved this phenomenon ().

Table 3. List of Councilors of Anshan Manchuria Architectural Association from 1924 to 1944.

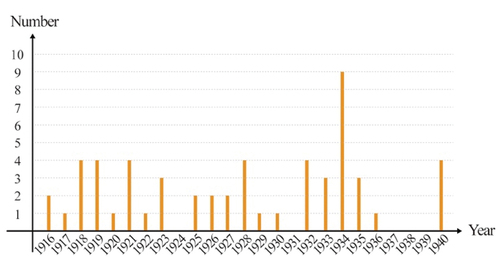

Private civil construction companies also welcomed a peak period from 1933 to 1934 to settle in Anshan (), witnessing the successive establishment of branch offices by many companies in Anshan, including the Ookuragumi, Yoshikawa Kensetsu Kabushiki Gaisha, Takaokagumi, Fukui-Takanashigumi, Igaharagumi, Oobayashigumi, Etc. Take the OobayashigumiFootnote11 as an example, from 1934 to 1939, and it inherited the internal railway of Showa Steel Works, the 9th blast furnace foundation, the third storage plant of Dagushan Mining, the No. 5–8 blast furnace auxiliary storage plant, and the first, second and third phases of Manchuria foundry iron Anshan factory.

Figure 15. The Number of Civil Construction Companies Established in Anshan City each year. Data from Dairen (Shogyo Kaigisho Citation1916, 67; Nihon Jitsugyo Shokokai Citation1939, 55; Mantetsu Kogyobu Shokoka Citation1922, 170–177; MantetsuCitation1927, 278–288; Hirao Citation1939, 25–28; Teikoku Shokokai Citation1935): 185.

5.3. The “Steel Kingdom” of the entire industry chain

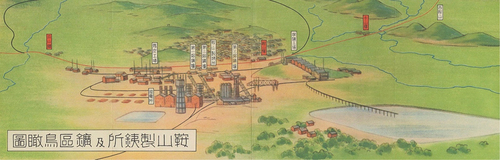

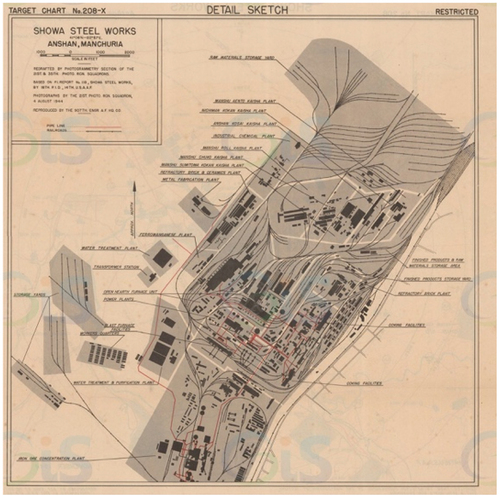

During the climax period, Showa Steel Works gradually established a heavy industry system centered on the iron and steel industries. Moreover, an industry chain was formed in the steel plant, covering mining operations, beneficiation operations, iron smelting operations, coke operations, and by-product operations (). At the same time, various chaebols and industrial associations established a series of upstream and downstream enterprises that involved Manchuria Sumitomo Kosai Kaisha Plant, Anshan Kosai Kaisha Plant, Manchuria Aento Kaisha Plant, Manchuria Chuko Kosai Kaisha Plant Anshan Factory, Onoda Cement Anshan Factory, and Manchuria Refractory Brick & Ceramics Plant ().

Figure 16. Showa Steel Works Operating System Diagram. Source from Showa Steel Works. 1934. “Showa Seikojo Seisen Sagyo Keito Zu.” Papers. Hitotsubashi University Institutional Repository Collection. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/10086/54253.

Figure 17. Layout of Showa Steel Works in 1944. Source from 14th U.S. AAF. 1944. “No.208-x Showa Steel Works.” Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences, RCHSS Collection. B-3741-1562-4_t008b.

The rapid economic revitalization not only attracted immigrants but also stimulated the commercial development of the streets. The massive increase in the number of commerce and government public buildings featured most prominently. Kondo Nobuyoshi, the editor of Manchuria Architectural Association, said in the Journal of Manchurian Architecture published in February 1934 that the establishment of Showa Steel Works had injected the Anshan construction with tremendous momentum. Centering on the theme of “Renaissance of Anshan Architecture,” he also praised the significant achievements of Anshan’s urbanization construction (Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Citation1934). The buildings include the Showa Steel Works office building and Showa Guesthouse built-in 1933, the Manchuria Bank Anshan Branch, Yokohama Specie Bank Anshan Branch, and the Iron Capital Anshan Store designed by Yokoi Architects in 1934 all demonstrated modernism. Since there is no need to show dominance like the political center of Changchun, the buildings preferred flat roofs over Asian-style sloping roofs (crown-style buildings).

In 1938, in consideration of the production increase plan of the Showa Steel Works during the climax period, the Central Government of Manchukuo and the Anshan Municipal Office made the “Anshan Phase I Urban Planning” with a population target of 500,000, which divided the urban into eight zones, including Showa Steel Works factory land, office, and residential land, (other) factory land, hospital land, school land, market land, slaughterhouse land, and entertainment land. The plan covered five years (1938–1942), with a total investment of seven million yen. In the first year, the Puppet Manchukuo government sold two million yen of Anshan public bonds. After that, Toyo Takushoku Kabushiki Gaisha borrowed 1 to 2 million yen each year (Toyo Takushoku Kabushiki Gaisha Citation1939).

6. The technologist’s imagination: ideology and urban modernization

Colonial technicians in wartime Japan displayed a complex fascist ideology. On the one hand, technicians were portrayed as empire-building tools, achieving ultra-nationalist political appeals through modern thinking and technology. On the other hand, technicians actively display a utopian vision of society, expecting to use the power of technology to create a modern “harmonious” society.

The research attempts to analyze the professional ideology of technicians from different perspectives. From a personal perspective, through the recollection of the technicians working in Anshan, one can clearly feel the pride in the construction achievements and the high recognition of the construction technology level. For example, the architect of Showa Steel Works, Matsuki Genjiro, compared Showa Steel Works with steel plants in Japan, Europe and the United States in the Journal of Manchurian Architecture in 1939, illustrating its outstanding construction(Matsuki Genjiro Citation1939). From the perspective of colonial politics, technicians attempted to solve colonial social problems with architectural solutions, and introduced the modernity of Western society into Northeast China by acting as an intermediary to establish the authority of colonial rule. For example, in the early planning, the technicians classified the wider and flat land as the steel plant construction area, and the narrow foothills as the city site (Okayama Citation1918) . This chaotic planning revealed that the colonists were motivated by plundering industrial and mining resources. During the climax period, especially after the establishment of the Anshan Municipal Administration in 1937, technicians began to try again to beautify its colonial purpose by building a modern city, which was manifested in the introduction of a modern planning and zoning system, the construction of parks, and luxurious public buildings. Its purpose is to show off to European and American countries its national strength to build a strong city of heavy industry centered on the steel industry on the one hand and to use modern values such as “progress, science and rationality” to ensure the authority and longevity of their rule on the other hand. In addition, Anshan has also become a testing ground for Japanese technicians to solve the domestic social improvement of the suzerain. For example, in 1919, Mantetsu experimentally built dense and large-scale housing and dormitories on the open land of Anshan. The success of this attempt led to the climax of Japanese colonists building collective housing in Manchuria and Japan, showing the reverse impact of the colony on the society and politics of the suzerain.

7. Conclusion

In recent years, the Chinese government has gradually begun to include the architectural heritage left by the Japanese colonists during the Sino-Japanese War in the list of cultural heritage protection, which has triggered academic discussions on the protection and utilization of “dissonant heritage”. Heritage can be interpreted from many angles, and people always tend to believe their own stories. From the perspective of colonists, Anshan Steel Works, a crucial link in the Japanese imperialist plan to build the heavy industry in Manchuria, is a symbol of an empire and modernity (Louise Young Citation1998). From the perspective of the colonized people, the construction of Anshan Steel Works has brought immense suffering to local residents. The completion of the steel plant was realized by colonial conditions such as exploitative plunder, forced labor and state violence.

From the perspective of colonial technicians, this paper narrates the construction process of Anshan Steel Works and examines how technicians implement their modernized design under the influence of the colonial ideology and transform technology into a force of colonial management and resource exploitation. Concerning the nearly 30 years of construction of Anshan during the occupation of Japan, the process and mode of urban space construction directly depended on the rise and fall of the steel plant, showing an intense industry-dependent colonial social relationship. Finally, it formed clear urban functional zoning (), completed the transformation from the primary mining industry to the heavy industrial technology system centered on the iron-smelting and steel-making industry. This construction process is neither an integrated whole planned by Japanese planners nor a single entity designed by architects. Actually, it should be ascribed to a series of complex political and economic factors, involving the cooperation and conflict of various stakeholders.

In short, the construction concept of the Japanese colonists in Manchuria is not the same as that in Japan. The colonial construction method in early Manchuria was mainly derived from Japan’s colonial experience in Taiwan, where the colonial construction was forcibly promoted by the huge official Architectural Organization. Its main colonial idea was determined by Goto Shimpei, the first president of Mantetsu. He firmly believed that the most crucial foundation for building a modern civilization lies in civil engineering, health, and education, and tried to prove the feasibility of his theory through the development of Manchuria. After the establishment of Manchukuo in 1932, a large number of Japanese technicians came to Manchuria, along with the arrival of the climax of urbanization. To escape Japan’s political pressure and cultural constraints and to realize its ambition to compete with Western countries for modernization, Manchuria has become an experimental site for Japanese architects to realize their ideals. From this perspective, we think that the construction concepts and technologies of Japanese technicians in Northeast China are more accessible and advanced than those in Japan. On the one hand, it is to demonstrate the authority of its colonial rule and compare it with the construction of Japan and Western countries; on the other hand, it is due to the “historical role” of the technicians who believe that they shoulder the task of spreading modernization to the backward regions. However, for the colonized people, such a forced modernization process came at a heavy price.

Acknowledgments

During the investigation, this research was helped by the staff of the Ansteel Museum, Ansteel Veteran Cadre Activity Center, and Ansteel Design Institute Archives. At the same time, special thanks to Xie Yishi and Wang Ruoran of the School of Architecture of Tianjin University for their opinions on this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/KNQBW, reference number “The Activities of Architectural Organizations and Professionals Under Colonial Rule.” https://osf.io/knqbw/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zijie Zhao

Zijie Zhao is a Ph.D. Candidate at School of Architecture, Tianjin University. His research interests are Architectural History and Theory.

Subin Xu

Subin Xu is a Professor at School of Architecture, Tianjin University. Her research interests are Architectural History and Theory.

Nobuo Aoki

Nobuo Aoki is a Professor at School of Architecture, Tianjin University. His research interests are Architectural History and Theory.

Tian Tian

Tian Tian is a Researcher School of Architecture, Taiyuan University of Technology. Her research interests are Architectural History and Theory.

Notes

1 The early buildings of the Anshan Steel Works included eight places, namely, the Showa Steel Works Office Building, Showa Guest House, Jingjingliao Dormitory, Manchuria Artificial School, No. 2 sintering Works, Rolling Works, Seamless Steel Tube Plant, and No. 1 Blast Furnace.

2 In accordance with the SMR Division Regulations, the Shahekou Railway Factory of the General Affairs Department was mainly responsible for the mechanical design, inspection, and repair of Manchurian Railways and locomotives, as well as the industrial design, research and development, and experimentation with the SMR Central Laboratory.

3 Including the first and second phases of blast furnaces, power plants, coal, by-product factories, and major civil construction works such as waterways, city houses, and gas.

4 In the first division of courses by SMR in 1907, the Company was divided into General Affairs Department, Investigation Department, Transportation Department, Mining Department, and Local Department. The Construction Section was subordinated to the Civil Engineering Division of the General Affairs Department. In 1914, it was restructured into the Department of General Affairs, Transport, Planning, Mining, and Local. The Department of General Affairs consisted of the Affairs Bureau, the Negotiation Bureau, the Technical Bureau, and the Technical Bureau consisted of the Architecture Section, Civil Engineering Section, and Railway Line Section.

5 The Anshan local office was formally established in 1923, with four departments: General Affairs Department, Local Department, Manager Department, and Engineering Department. It also administered various schools, libraries, and health centers. The Department of Construction was explicitly responsible for civil construction, improvement, and preservation of buildings, water and sewage, pump operation, and water purification equipment operation.

6 The Ookuragumi Chamber of Commerce was one of the largest chaebol groups in Japan in modern times. The founder, Okura Kihachiro, established the Ookuragumi Chamber of Commerce in 1873 to engage in merchandise sales and other industries. Since then, he has made his fortune through arms sales and actively expanded the scope of business, responsible for a few civil engineering projects in North Korea, China, and Taiwan. Later, he was mainly engaged in investment in mining activities.

7 Anshan Real Estate Trust Co. Ltd. was established in 1921, headed by Makoto Kametaro, with Manchurian Railway as its largest shareholder. Its main business involved real estate sales, construction, leasing, and trust.

8 The first phase of the expansion plan included the construction of the concentrating plant, the expansion of the blast furnace, coke and by-product plants, the expansion of water channels and power equipment, the repair of the repairing plant, and the mining plant.

9 In 1923, Onogi Takaharu, Ichida (later Aoki) Kikujiro, and Yokoi Kensuke founded the Onoki Yokoi Ichida Joint Architectural Office in Dalian. In February of the following year, Ichida Kikujiro resigned from the Company to head the SMR Architecture Section. The office was renamed Onoki Yokoi Joint Architects. In 1930, Onogi Takaharu withdrew due to illness, and the joint office was dissolved. After that, Yokoi Kensuke opened the Yokoi Architects office in his own name.

10 The role of councilors is to advise the chairman and consider essential matters. The other Anshan councilors of the Manchuria Architectural Association in the same period were all employees of the SMR, including Shimada Kichiro, Shioda Chuzo, and Deriha Kiichiro.

11 The Oobayashigumi was founded by Obayashi Yoshigoro in Osaka, Japan. During the Russo-Japanese War, he contracted civil and railway works in Lushun and other places. In 1933, the Dalian branch was formally established, headed by Takahashi Seiichi. It founded the Changchun and Shenyang branches in 1934, the Tianjin branch in 1938, and the Beijing branch in 1938.

References

- Akira, K. 1988. Manshukoku No Shuto Keikaku: Tokyo No Genzai To Mirai O Tou [Manchukuo capital plan: Asking the present and future of Tokyo]. Tokyo: Nihon keizai hyoronsha.

- Bao, M. 2016. “Japanese Architectural Activities in Mainland China.” In History of Modern Chinese Architecture, edited by, X. Subin, J. Wu, and D. Lai. Part15. Vol. 5 3–186. Beijing: China Architecture Publishing & Medal Press.

- Barlow, T. E., ed. 1997. Formations of Colonial Modernity in East Asia. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Battilani, P., C. Bernini, and A. Mariotti. 2018. “How to Cope with Dissonant Heritage: A Way Towards Sustainable Tourism Development.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26 (8): 1417–1436. doi:10.1080/09669582.2018.1458856.

- Chen, C.-C. 2017. “The Study of the Emergence, Development and Influence of the Architectural Institute of Manchu under Japanese Rule.” Ph.D diss, National Cheng Kung University.

- Chiyoji, M. 1976. “Tateyama Rinji Koji Jimusho No Omoide [Memories of Li-Shan Temporary Construction Office.” In Mantetsu No Kenchiku to Gijutsu Jin [The Architects and Engineers of SMR], Mantetsu No Kenchiku To Gijutsu Jin HenshuIin Kai, 241–243. Tokyo: Mantetsu Kenchiku Kai.

- Chu-joe, H. 2020. Representation of Space. Shanghai: Tongji University Press.

- Collins, R. 1990. “Changing Conceptions In The Sociology Of The Professions.” In The Formation of Professions: Knowledge, State and Strategy, edited by R. Torstendahl and M. Burrage, 11–23. London: Sage.

- Driscoll, M. 1999. “Imperial Textuality, Imperial Sexuality.” In Proceedings of Midwest Association for Japanese Literary Studies 5: 156–174. West Lafayette: Association for Japanese Literary Studies.

- Faye-Yuan, K. 2003. Under an Imperial Sun: Japanese Colonial Literature of Taiwan and the South. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Genjiro, M. 1939. “Manshu Kenchiku Gukan [Manchurian Architecture in My Opinion].” Manshu Kenchiku Zasshi 19 (4): 32–34.

- Historic England. 2021. “Checklist to Help Local Authorities Deal with Contested Heritage Decisions.” Historic England, October 26. Accessed 14 December 2021. https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/planning/planning-system/contested-heritage-listed-building-decisions/

- Jing, W. 2018. “Spatializing Modernity: Colonial Contexts of Urban Space in Modern Japanese Literature.” PhD diss, Toronto University.

- Jitsugyo Shokokai, N. 1939. Nihon Jitsugyo Shoko Meikan [Japanese Business Directory]. Osaka: Nihon Jitsugyo Shokokai.

- Johnson, T. J. 1972. Professions and Power. London: Macmillan.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1924. “Kaiho [Report].” Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi 04 (4): 55.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1928. “Mantetsu Anzan Iin Shinchiku Koji Gaiyo [Outline of New Construction of Mantetsu Anshan Hospital].” Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi 08 (1): 42.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1930a. “Kaiho [Report].” Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi 10 (10): 73.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1930b. “Kaiho [Report].” Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi 10 (11): 77.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1933. “Kojin Kyo Reki[History of the Deceased].” Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi 13 (2): 1–4.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1934. “Kenchiku Kai IKiki- Anzan No Toshi Kei Egaki [Anecdote of Architecture - Anshan City Plan].” Manshu Kenchiku Zasshi 14 (2): 38.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1937. “Kaiho [Report].” Manshu Kenchiku Zasshi 17 (10): 37.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1939. “Kan Atama [Volume Head].” Manshu Kenchiku Zasshi 19 (2): 8.

- Kenchiku Kyokai, M. 1942. “Ryakureki [Biography].” Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi 13 (2): 1–4.

- Kensetsu Shashi Iinkai Hen, T. 1963. Taisei Kensetsu Shashi [History of Taisei Kensetsu]. Tokyo: Taisei Kensetsu.

- Kiichiro, D. 1933. “Kacho Jidai He No Kai so [Reminiscing about the Era of Chief Onogi Takaharu].” Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi 13 (2): 68–72.

- Kogyobu Shokoka, M. 1922. Manshu Shoko Yoran [Manchurian Commerce and Industry Handbook]. Dalian: Manmo Bunka Kyokai.

- Kogyobu Shokoka, M. 1927. Manshu Shoko Yoran [Manchurian Commerce and Industry Handbook]. Dalian: Mantetsu Kogyobu Shokoka.

- Kuroishi, L. 2014. Constructing the Colonized Land: Entwined Perspective of East Asia around WWII. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing.

- Laurajane, S. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

- Macdonald, K. M, ed. 1999. “Professions and the State”. In The Sociology of the Professions, 100–123. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Mainichi Shinbunsha, O. 1919. “Tetsu No to [City of Iron].” Osaka Mainichi Shinbunsha, June 10. Accessed 13 July 2021. Kobe University Library Sumida Maritime Materials Collection. http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/infolib/meta_pub/G0000003ncc_00045690

- Manshikai. 1965. Manshu Kaihatsu Nen Shi [Forty Years of Development in Manchuria]. Vol. 2. Tokyo: Manchuria Kaihatsu Nen Shi Kankokai.

- Mataitirou, T. 1933. “ChoShi [The Eulogy].” Manshu Kenchiku Kyokai Zasshi 13 (6): 41–42.

- Matsusaka, Y. T. 2010. “Japan’s South Manchuria Railway Company in Northeast China, 1906–1934.” In Manchurian Railways and the Opening of China: An International History, edited by B. A. Elleman and S. Kotkin, 37–58. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Moore, A. S. 2013. Constructing East Asia: Technology, Ideology, and Empire in Japan’s Wartime Era 1931-1945. California: Stanford University Press.

- Moriichi, K. 1976. “Tsuioku No Katadan[Reminiscence of the Past].” In Mantetsu No Kenchiku to Gijutsu Jin [The Architects and Engineers of SMR], Mantetsu No Kenchiku To Gijutsu Jin HenshuIin Kai, 266. Tokyo: Mantetsu Kenchiku Kai.

- Nen Shi Iinkai, H. 1989. Hazamagumi Nen Shi: 1945-1989 [Century History of the Hazamagumi]. Tokyo: Hazamagumi.

- Nichi Nichi Shinbun, M. 1923. “Anzan Fukkatsu to Seiko Gyo [Anshan Renaissance and the Iron and Steel Industry].” Manshu Nichi Nichi Shinbun, August 18. Accessed 30 April 2021. Kobe University Library Sumida Maritime Materials Collection. http://www.lib.kobeu.ac.jp/infolib/meta_pub/G0000003ncc_00049714

- nippo, M. 1933. “Tetsu-to Anzan Koshinkyoku [The Marching Song of Anshan, the Capital of Steel].” Manshu Nippo, October 18-24, August 18. Accessed 30 April 2021. Kobe University Library Sumida Maritime Materials Collection. http://www.lib.kobeu.ac.jp/infolib/meta_pub/G0000003ncc_00053156

- Nobuo, A., X. Subin, and W. Ruoran. 2016. “The Humanistic Value Orientation - Reevaluation and Cultural Strategy of Modern Industrial Heritage Sites Involving Sensitive Issues.” Urban Environment Design 102 (8): 396–401.

- Okayama. 1918. “Anzan Seitetsujo O Miru [Observation of Anshan Iron Works].” Osaka Asahi Shinbunsha, April 10. Accessed 10 July 2021. Kobe University Library Sumida Maritime Materials Collection. http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/infolib/meta_pub/G0000003ncc_00045507

- Rodney, H. 2013. Heritage Critical Approaches. NY: Routledge.

- Saburo, A. 1940. Showa Seikojo Niju Nen Kokorozashi [Twenty Years of Showa Steel Works]. Anshan: Showa seikojo.

- Sadao, F. 1976. “Mantetsu Ni Okeru Watashi No Ayumi [My growth path in SMR].” In Mantetsu No Kenchiku to Gijutsu Jin [The Architects and Engineers of SMR], Mantetsu No Kenchiku To Gijutsu Jin HenshuIin Kai, 236. Tokyo: Mantetsu Kenchiku Kai.

- Seikojo Gyomuka, S. 1934. “Gyomu Kanri Shiryo [Showa Seikojo Business Management Papers].” Nihon Kyumanshu Tekko Gyo Shiryo. HERMES-IR, Hitotsubashi University Repository. https://hdl.handle.net/10086/51098

- Sewell, B. 2019. Constructing Empire: The Japanese in Changchun, 1905-45. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Sha, Y. 2001. A Comparation Research on Development of Architecture between Modern China and Japan. Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers.

- Shengjing Times. 1903. “Fan Zhong Gong Cheng Ju Guang Gao [Iizuka Engineering Advertisement].” Shengjing Times(Shenyang), April 1.

- Shiryo Hensan Kai, C. 1986. Kindai Chugoku Toshi Chizu Shusei [Atlas of Modern Chinese Cities]. Tokyo: Kashiwa Shobo.

- Shogyo Kaigisho, D. 1916. “Dairen Shogyo Kaisho Jimu Hokoku [Dalian Commercial Council Office Report].” Dalian: Dairen Shogyo Kaigisho.

- Shokokai, T. 1935. Teikoku Shoko Shinyo Roku: Bunsatsu (Manshuban) [Empire Commerce and Industry Credit Record: Separate Volume (Manchurian Edition)]. Osaka: Teikoku Shokokai.

- Shomubu Chosaka, M. 1928. Minami Manshu Tetsudo Kabushiki Gaisha Dai Ji Nen Shi [The Second ten-year History of Manchurian Railway Co. Ltd.]. Dalian: Mantetsu.

- Sosai Shitsu Chihobu Zammu Seiri Iinkai, M. 1977. Mantetsu Fuzoku Chi Kyo Ei Enkaku Zenshi [The History of the Management of Mantetsu’s Affiliated Territories]. Vol. 2. Tokyo: Ryukei Shosha.

- Subin, X. 1991. “Comparison, Communication and Enlightenment: Research on the History of Modern Architecture between China and Japan.” PhD diss, Tianjin University.

- Subin, X. January 2020. “Rethinking on the Driving Force Mechanism of the Development of Modern Chinese Architecture.” The Architect 203 (1): 96–102. CNKI:SUN:JZSS.0.2020-01-015.

- Takushoku Kabushiki Gaisha, T. 1939. “Anzan Shi Dai Ki Toyu Keikaku Shikin Kashidashi No Ken [Fund Loan-out to Anshan City 1st Term City Planning in 6th Year of Kangde].” JACAR (Japan Center for Asian Historical Records) Ref.B06050256900, 9. Other/(9) Fund Loan-out to Anshan City 1st Term City Planning in 6th Year of Kangde (1939), Handled by Xinjing Branch (E88) (Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

- Tatemono Shashi Iinkai, T. 1998. Shinrai O Mirai He: Tokyo Tatemono Nen Shi [Trust in the future: Century history of Tokyo tatemono]. Tokyo: Tokyo Tatemono.

- Tsunesaburo, U. 1927. “Anzan Seitetsujo No Tokusei to Nihon Sei Kurokane Kai Ni Oite Ri Ru Chii [Characteristics of Anshan Seitetsujo and Its Position in the Japanese Steel Industry].” Manshu Gijutsu Kyokai Zasshi 04 (19): 149–165.

- Tunbridge, J. E., and G. J. Ashworth. 1996. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the past as a Resource in Conflict. NY: Wiley.

- Ukichi, S. 1976. “Mantetsu to Tomoni Ayun Ta Boku No Hansei [Half of My Life with Manchuria Railway].” In Mantetsu No Kenchiku to Gijutsu Jin [The Architects and Engineers of SMR], Mantetsu No Kenchiku To Gijutsu Jin HenshuIin Kai, 214. Tokyo: Mantetsu Kenchiku Kai.

- Wang, L. 2010. Anshan Jin Dai Jian Zhu [Modern Architecture in Anshan]. Shenyang: Northeastern University Press.

- Watanabe. 1917. “Iwayuru Anzan Seitetsu Kojo [The so-called Anshan Iron Works].” Osaka Asahi Shinbunsha, August 3. Accessed 5 July 2021. Kobe University Library Sumida Maritime Materials Collection. http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/infolib/meta_pub/G0000003ncc_00045313

- Xiaoqun, X. 2001. Chinese Professionals and the Republican State. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Xie, X., and K. Zhang. 1984. An Gang Shi (1909-1948) [The History of Anshan Steel Works(1909-1948)]. Beijing: Matallurgical Industrial Press.

- Yang, L., D. Karine, and J. Xin. 2021. “A Systematic Review of Literature on Contested Heritage.” Current Issues In Tourism24 (4): 442–465.

- Yasuhiko, N. 1994. “The Architects’ Office of South Manchuria Railway and Its’ History : Studies on the Japanese Architects in the Northeastern Province of China ‘Manchuria’ in the First Half of the 20th Century Part 3.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians of Japan 457 (March): 215–224. doi:10.3130/aija.59.215_1.

- Yasuhiko, N. 1996. Japanese Oversea Architects: Architectural Activities in Northeastern China in the First Half of the 20th Century. Tokyo: Shokokusha Press.

- Yasuhiko, N. 2001. “Residential Policies of Former South Manchuria Railway Ltd.” In Anthology of 2000 International Conference on Modern History of Chinese Architecture, edited by Z. Fuhe. Beijng: Tsinghua University Press.

- Yasuhiko, N. 2009. Nihon No Shokuminchi Kenchiku: Teikoku Ni Kizuka Reta Nettowaku [Japanese Colonial Architecture: A Network Built by Japanese Emperor]. Tokyo: Kawade Shobo Shinsha Press.

- Yasuo, H. 1939. “Anzan Tokei Nempo [Anshan Statistics Annual Report].” Anshan: Anzan Shoko Kokai.

- Young, L. 1998. Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Yuichi, A. 1925. “Anzan Seitetsujo Sen Aragane Kosho Ni Tsu Te [About the Concentrating Plant in Anshan Steel Works].” Manshu Gijutsu Kyokai Zasshi 2 (10): 529–542.

- Yutaka, T., and H. Fujii. 2013. Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Modern Japan. Tokyo: Kajima Publishing.