ABSTRACT

Ieoh Ming Pei completed his work on the Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing in the year of 1983. This has been a piece of significant work in modern Chinese architecture. Corresponding studies and discussions have been mainly attracted to its style and its exploration of modernity, while relatively less concentrated on a close reading of the design. Taking “site reconstruction” as a clue, this paper traces the historic transformations of the site condition of this hotel. Following a chronological review and a formal analysis of different time periods, the paper revisits the discourse of the Fragrant Hill Hotel both in Chinese and American contexts. It examines the gaps between Chinese and American critiques and speculates on the reasons for the discrepancies. By comparing the discursive focus of “hunting park” and “imperial garden,” this paper attempts to uncover the tension between history and identity concealed in I.M. Pei’s address on the site. While the inconsistency is partly due to the time and people’s standpoints originating from the time, it still shows how design functions as a form of power in the history.

1. Introduction

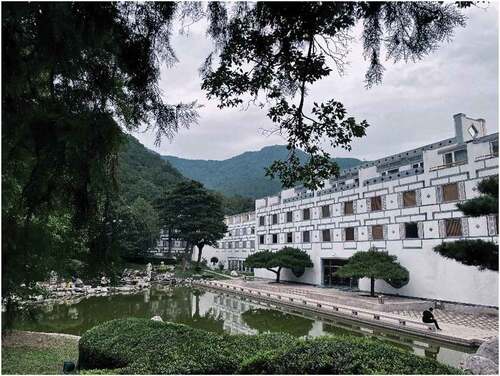

The Fragrant Hill Hotel was the first work of the Chinese-American architect Ieoh Ming Pei in Mainland China. It is also the earliest work by an introduced foreign architectural expert after China’s reform and opening up (Zou et al., Citation2010, p. 106). Since I.M. Pei accepted the design invitation of the Fragrant Hill Hotel in late 1978, he had participated in numerous seminars, interviews, and speeches both in China and in the West. According to his repeated statements in American and Chinese contexts, it has been a narrative model that he was going to design by encapsulating Chinese architectural traditions into the process of “modernization” in China. At the end of 1982, the “Symposium on the Fragrant Hill Hotel”, attended by more than 30 Chinese scholars and experts, marked the climax of the domestic debate, but I.M. Pei was absent. The Jianzhu Xuebao (建筑学报) published the symposium’s outcomes in its March and April 1983 issues, together with nine critical papers on the Fragrant Hill Hotel. ()

Figure 1. The current state of the central courtyard of the Fragrant Hill Hotel in 2021. photograph by Zhang Nan

The New York Times published its first report on the construction a week after the opening ceremony of the Fragrant Hill Hotel in October 1982. While the major crowd of international reviews of the project appeared mainly in 1983, The New York Times, Connoisseur, House & Garden and Architecture published further critiques on the Hotel in January, February, April, and September that year. () The English coverage primarily focused on the role it played in the evolution of I.M. Pei’s design career from the perspectives of the design and construction narrative. Conversely, the Chinese critiques of that period were aimed at “comparing the Fragrant Hill Hotel with ‘our architecture’ and thus integrating it into the discussion of Chinese architectural traditions and approaches.” (Liu Citation2009, 53) After 1990, I.M. Pei’s biographies and portfolios lent the details of previous media reports and hence helped to establish a discursive set of information.

Figure 2. Several Chinese and American periodicals in 1983 with the Fragrant Hill Hotel on their covers, from left to right: Jianzhu Xuebao, 1983(03); Xin Jianzhu (New Architecture), 1983(01); Connoisseur, 1983(02); Architecture, 1983(09).

After more than forty years, discussions about the modern transformation of Chinese architectural tradition around the Fragrant Hill Hotel are still ongoing. Behind the academic community’s efforts is the desire to uncover the original context of modern Chinese architecture from historical materials, which ensures theoretical discussions and a perspective in further research. Recent studies on the Fragrant Hill Hotel have gradually moved from subjective critiques to textual and discursive analysis in the following two directions. One is to revisit the 1982 Symposium organized by the Jianzhu Xuebao so that whose vitality in modern Chinese architecture history can be defined (Liu Citation2009; Hu Citation2014). By detecting the subtle contrasts between the experts’ speeches at the symposium, researchers examined the cognition and the transformation of the concept of “modernism” in Chinese architecture in the 1980s. Another direction is to refer to I.M. Pei’s biographies, archives, and interviews, in order to locate the significance of the Fragrant Hill Hotel in Pei’s architectural career and the complex role of this design in the dual context of China’s early economic reforms and the American post-modernist ideology (Fang Citation2008; Zhu Citation2009; Chen Citation2017; Roskam Citation2015, Citation2017).

However, multiple lines of evidence indicate that the Fragrant Hill Hotel was a reconstruction project on a site with historical remains according to the documentations kept by the Pei archives at the Library of Congress and other related institutions. This perspective has long been neglected by the architectural community. Although several experts noticed this information during the 1982 symposium, it did not receive agreement from the general criticism on economy and practicality. It did not attract the attention of subsequent architectural studies either. However, the site of the Hotel has been mentioned in studies relevant to the history of the Fragrant Hill, as it used to be the Central Palace (中宫) in the Qing Dynasty’s imperial Jing Yi Garden (静宜园), then it became the Republican-era Protectory (香山慈幼院) and finally the site of the former Fragrant Hill Hotel after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Most historical studies were restricted to a specific period and did not form an overall chronological narrative. Furthermore, I.M. Pei was often reticent to talk about the history of the Fragrant Hill Hotel site in the Chinese context, whereas he would refer to it as a “former imperial hunting park” in the English-speaking world. Other American critiques continued following this unfamiliar term, resulting in the site design of the Fragrant Hill Hotel being shadowed by its absence.

Though neglected in the field of architecture, the site information is still very necessary in understanding deeper the design and discourse of the Fragrant Hill Hotel. The “site reconstruction” provides an essential perspective that is both circumstantial and analytical on the relationship between architecture and site. Moreover, it orients a critical evaluation of the contrasting discourses on the “site choice” in China and the West. Therefore, this paper attempts to examine the 40-year-long controversy on the Fragrant Hill Hotel from the perspective of site reconstruction. How has the site of the Fragrant Hill Hotel evolved during its history? What would it mean to take the absence of site information as the historical condition under which the Fragrant Hill Hotel is produced as design work and understood as discursive formation?

2. Methodology

Taking the Fragrant Hill Hotel as a site reconstruction project, the Archaeology of Knowledge is the primary methodology to provide a critical perspective on modern Chinese architectural criticism. Based on “discursive analysis” in linguistic philosophy, this paper is devoted to establishing the structure of discourse into a genealogy. The paper then interprets discursive formation and reveals the hidden ideological power by probing images and textual content.

Hu (Citation2014) examined fifteen critical articles on the Fragrant Hill Hotel that appeared in the Jianzhu Xuebao from 1980 to 1992. He concluded three discursive modes around the Fragrant Hill Hotel and the different meaning systems. Different from Hu’s study, we endeavored to critically understand I.M. Pei’s approach to the site and its historical reference by taking “site reconstruction” as a central concept and combining historiography with formal analysis. We then compare the evidence from maps with the ambiguous “site” discourse. On this basis, this paper describes two interrelated but separate discursive structures. The first one is the site of the Fragrant Hill Hotel itself. Here we are interested in the historical transformations of different architecture for different usages, that is, from an imperial garden to a school, and then to a guest house and finally an international hotel. The second is the discussion of the set Chinese attitudes towards the site against the Western ones. In other words, we will compare how scholars and architects from different cultural backgrounds have each made their comments on the design so that the historical reference of the site was obscured.

These analyses are implied in the following three sections. In the first section, a connection of the historical lineage to a transparent and credible narrative is established, according to the transformation of the site from an imperial garden in the Qing Dynasty to the Fragrant Hill Hotel’s redevelopment after the Chinese economic reform. In the second section, we compare the site reconstruction proposals of the five periods horizontally, converting ourselves from historical research to a brief formal analysis exploring I.M. Pei’s design strategies and historical references in his approach to the redevelopment of the Fragrant Hill Hotel. In the third section, to understand the starting point of architectural criticism and its contextual basis in diversified contexts, we analyze the studies on the history of the site, and then the different proposals within Chinese and Western discourse systems, respectively. On this basis, we attempt to identify the self-contradictions of I.M. Pei and the reasons behind them in terms of cultural identity. Accordingly, this paper aims to respond to the research questions through the above three steps. In each point of historical, formal and discursive analysis, we always focus on the “site” as the center of the discussion.

3. The archaeology of the Fragrant Hill Hotel site

3.1. From the Central Palace in Jing Yi Garden to the Girls’ School of Protectory

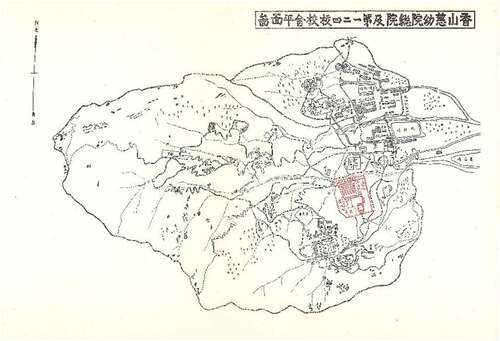

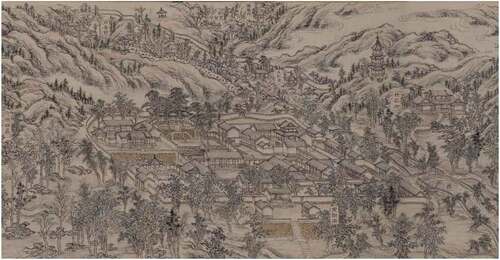

Located in the northwestern suburb of Beijing, Fragrant Hill is in the ranges of the Western Hills (西山). Several imperial temples have been built on the Fragrant Hill from Tang Dynasty (618–907) to Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).Footnote1 The Kangxi Emperor in Qing Dynasty constructed a garden here in 1677. It was further expanded by the Qianlong Emperor in 1745, who gave it the name of Twenty-eight Attractions of Jing Yi Garden. The courtyard of “Xulang Hall (the hall of modesty and enlightenment),” located in the Central Palace (), was one of these attractions (Qianlong and Yu Citation1746).

Figure 3. Xulang Hall (Central Palace) group in the scroll of “Twenty-eight Attractions of the Jing Yi Garden,” painted by Zhang Ruocheng, Qing dynasty, Copyright © Online Archives of the Palace Museum of China

The Jing Yi Garden was one of the imperial gardens in the Western Hills that were twice ransacked and burned by foreign aggressors in 1860 and 1900. During the Guangxu years, the imperial family entrusted the Yangshi Lei (样式雷) with restoring the Jing Yi Garden. “However, most of the work remained schematic, and only a few buildings were restored. Besides the buildings in Qianlong Emperor’s plan, the new scheme added a courtyard in the southwest corner and eliminated the miscellaneous courtyard on the south side of Huachan Room; in spite of these changes, the layout was not significantly reversed.” (Li and Yang Citation2022, 32)

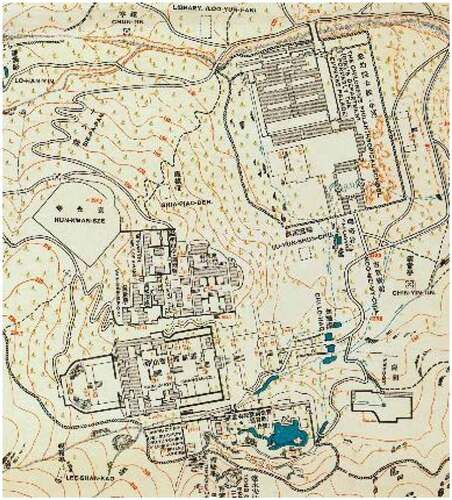

In 1912, Ma Xiangbo and Ying Lianzhi petitioned the former Empress Dowager of the Qing Dynasty, Long Yu, to borrow the grounds of the Fragrant Hill for a girls’ school, called Jing Yi Girls’ School (静宜女子学校) (Qian and Zhang Citation2020, 195). Xiong Xiling established the Fragrant Hill Protectory nine years later. He expanded the grounds of the original girls’ school to accommodate orphans during the war and natural disasters (Xiong Citation1920). () When the Protectory was first established, it was divided into two schools, one for boys and another for girls. The girls’ school of the Protectory is located in the former Central Palace, where the current Fragrant Hill Hotel stands. The new school buildings partly followed the original layout of the Central Palace. There were eight classrooms, four dormitories, a library, several offices, several shops, and several bathrooms in the girl’s school, and these functional places counted altogether 46 buildings (Xiong Citation1922).

3.2. Two “Fragrant Hill Hotels” in image and text

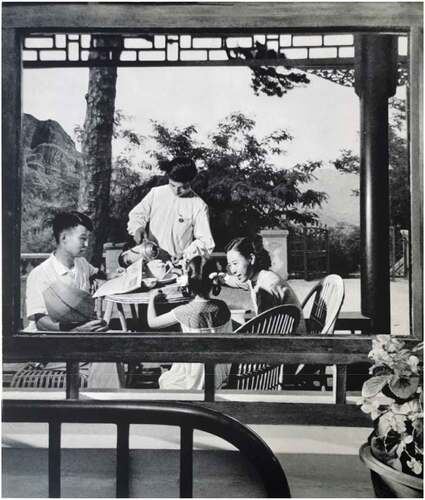

After the opening of the Protectory, Xiong Xiling opened a “Fragrant Hill Hotel” on the site of the former Fragrant Hill Temple to subsidize educational expenses. According to Li (Citation1937), who taught at the Protectory, “now that the temple no longer exists, the buildings were converted into the originally Ganlu Hotel, which was renamed to the Fragrant Hill Hotel in 1930. When I was working at the Protectory, most of my colleagues hosted their guests there. The food was immaculate. However, the room rent was expensive, so most visitors would not spend a night there.” In addition, Preston Moore once visited the original Fragrant Hill Hotel with his family when his father was a military officer stationed in China in 1931 (Wiseman Citation1990, 203). He became an architect in I.M. Pei’s company and engaged in the design and on-site construction of the Fragrant Hill Hotel half a century later. () It can be determined that the original Fragrant Hill Hotel (Ganlu Hotel) of the Republican period was near the Fragrant Hill Temple, but it is not the same site as the present Fragrant Hill Hotel.

Figure 5. Partial map of Central Palace and Ganlu Hotel (later renamed as Fragrant Hill Hotel). copyright © Chen Anlan 1920.

After the Pingjin campaign, the People’s Liberation Army arrive in the suburbs of Beijing in 1948. The Protectory was then moved from Fragrant Hill to the city to spare enough space for the army (Fragrant Hill Park Administration Citation2001, 20–24). In April 1957, the government approved utilizing the existing buildings to open a “Fragrant Hill Hotel,” which was officially opened in June. This former Fragrant Hill Hotel was one of the eight largest hotels in Beijing in the 1950s. It was a place for dignitaries to stay and dine for short periods and was not precisely for profit. Although it was called a “hotel,” it more functioned as a government guest house under the planned economy. ()

Figure 6. The interior of the former Fragrant Hill Hotel between 1957 and 1978. The original description was “Enjoy the summer at the Fragrant Hill Hotel in the dense forest (在层峦密林的香山饭店里消夏)”. Copyright © Picture album of Beijing, Beijing Editorial Board Press. 1959, pp. 138.

The former Fragrant Hill Hotel inherited the name of the original Fragrant Hill Hotel of the Republican era. However, it was no longer located within the Fragrant Hill Temple. Instead, it occupied the grounds and buildings of the former Protectory, which also included the present Fragrant Hill Hotel site.Footnote2 (Fragrant Hill Park Administration Citation2001, 299) We can refer to the People’s Daily (Ji Citation1982) cover of the opening of I.M. Pei’s Fragrant Hill Hotel: “The new Fragrant Hill Hotel was rebuilt on the former Fragrant Hill Hotel site. The total area of the new hotel does not exceed that of the former one.”

Impacted by several significant earthquakes in the surrounding region, the original buildings of the former Fragrant Hill Hotel sank and cracked in the 1970s. With the approval of the State Council, the Beijing City Planning Commission and the Construction Commission issued a notice to renovate the Fragrant Hill Hotel in October 1979. Following discussions in Beijing, I.M. Pei and his firm determined the final design for the Fragrant Hill Hotel, agreeing that all original buildings inside the retaining wall would be demolished. (Chen and Guo Citation2012, 235) Demolition was initiated in November 1979, marking the end of the former hotel’s history from 1957. The groundbreaking for the new hotel started in April 1980. (Hoving Citation1983, 78) A grand opening ceremony for the I.M. Pei-designed Fragrant Hill hotel was held on 17 October 1982.

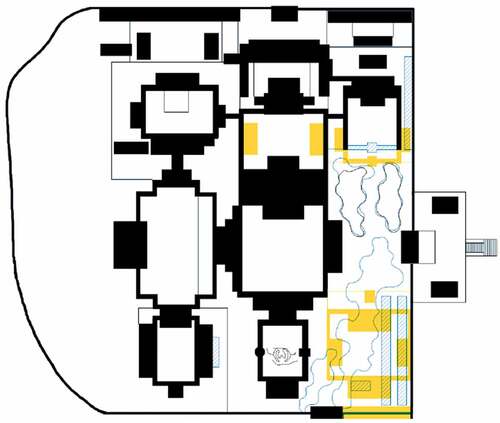

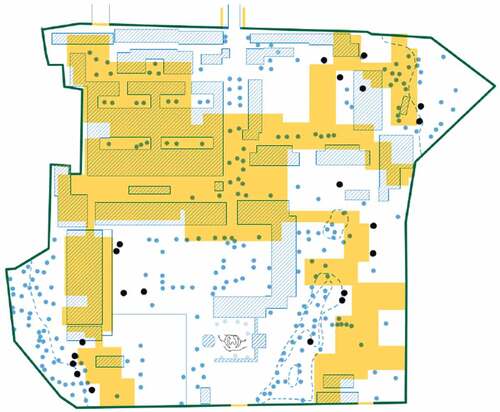

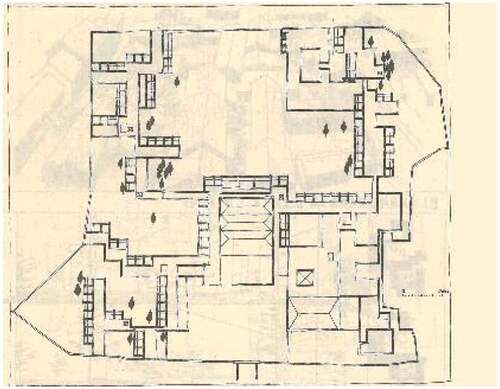

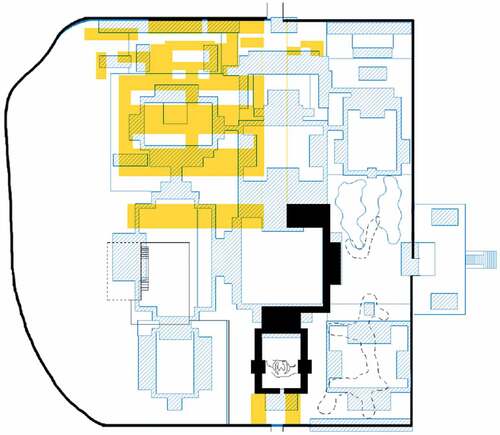

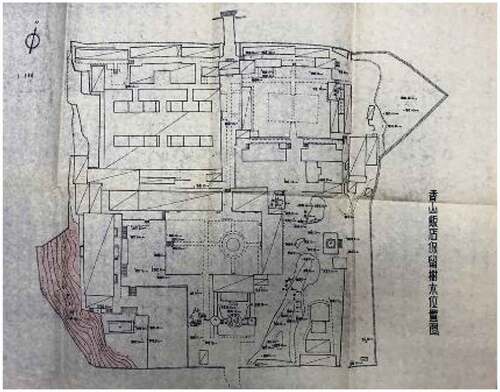

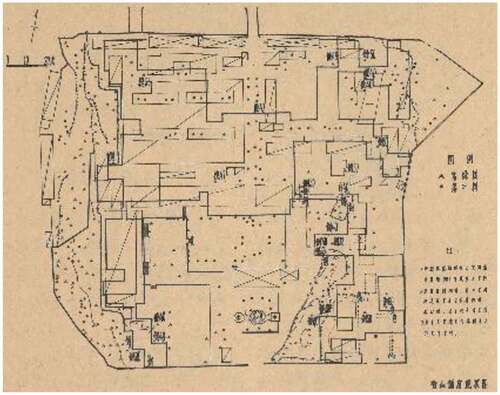

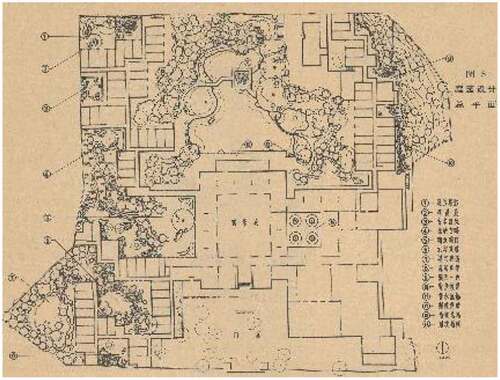

4. Five reconstruction plans for the site

The site of the Fragrant Hill Hotel underwent several reconstructions between the 17th and 20th centuries. The Kangxi Emperor constructed a palace upon the original Yong’an Village in the 17th century. The Qianlong Emperor later expanded it into the Central Palace of Jing Yi Garden in the mid-18th century. Unfortunately, the site was subjected to two military disasters in the 19th century, in between which Yangshi Lei designed the reconstruction but failed to realize. The 20th century saw even more rapid changes. It was home to the Jing Yi Girls’ School and the later Protectory during the Republican era. Between 1957 and 1978, the former Fragrant Hill Hotel served as a government-owned guest house. The original buildings were all demolished in 1979, and the present Fragrant Hill Hotel was built during 1980–1982. In considering the five reconstruction plans for the site, we can identify the following significant revisions (). We use blue to indicate areas that have been removed, black to indicate portions that have been retained, yellow to indicate portions that have been added newly, and grey to denote that the change cannot be determined from our available materials.

Figure 7. a) Central Palace scheme of Qianlong years (redrawn from a Yangshi Lei drawing provided by Li Jiang and Yang Jing). b) Central Palace scheme of Guangxu years (redrawn from a Yangshi Lei drawing provided by Li Jiang and Yang Jing). c) The Fragrant Hill Protectory, Republican period (redrawn from the entire map of the Jing Yi Garden by Chen Anlan). d) 1957–1978 Former Fragrant Hill Hotel (redrawn from archival drawings provided by Liu Shaozong and Pei Architects). e) Diagram of trees preserved at the Fragrant Hill Hotel since 1982 (redrawn from a diagram provided by Wang Tianxi). f) The general plan of the courtyard planting of the Fragrant Hill Hotel since 1982 (redrawn from a plan provided by Liu Shaozong). A 1920 photograph of the Girls’ School of Protectory. Provided by (Qian and Zhang Citation2020).

4.1. Site remnants

A comparison of the general plan of Jing Yi Garden with that of the Protectory shows that the main building of the Protectory was built roughly on the foundations of the former theatre (戏台) and the area around the Xuegu Hall (学古堂) of Jing Yi Garden (). The building on top of the theatre foundation was the dining hall of the Girls’ school (Chen and Guo Citation2012, p. 231). The foundations of the western part are relatively well-preserved, at least before the Protectory period of this site (). The elevations of Kuangzhen Hall (旷真阁), its courtyard, and Yiqing Shushi (怡情书史) were 2.7, 1.3 and 4.1 meters respectively, as shown on Chen Anlan’s mapping. In the design of the Fragrant Hill Hotel, I.M. Pei transformed the site’s original terrace (which should have been the foundation of the Yiqing Shushi) into an outdoor swimming pool.

Figure 8. A 1920 photograph of the Girls’ School of Protectory. Provided by (Qian and Zhang Citation2020).

Figure 9. Architecture in the west compound of Protectory. Provided by Yang Jing Citation2022.

It is controversial why the outline of the courtyard wall in the Protectory differs from that of the former Fragrant Hill Hotel period. The “restoration of the broken wall and retaining wall” in the 1950s-1970s might be the reason, for it has been mentioned several times in the “Fragrant Hill Park Chronicles.” The eastward extension increased the site area. A group of buildings framed a courtyard during the former Fragrant Hill Hotel period. In addition, two bar-shaped buildings appeared on the west side, roughly situated on the former foundation of the Kuangzhen Hall. The changes thus created a semi-enclosed layout on the southwestern side, but the overall plan was still not systematic.

4.2. Site elements

We compared the original site plan before reconstruction (, ), the general plan of the new courtyard design provided by the Beijing Landscape Bureau (), and the diagram of the preserved trees provided by Wang Tianxi, who was then the intern architect of PEI Architects (). It is likely that the trees in the garden of I.M. Pei’s Fragrant Hill Hotel were mostly redesigned and transplanted, for they were originally not on the site. The “Fragrant Hill Park Chronicles” documented three discussions related to the “Cutting of Trees”:

Figure 10. Map of the preserved trees at the Fragrant Hill Hotel, copyright © Box 138, Folder 6, I.M. Pei Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Figure 11. The original state of the former Fragrant Hill Hotel, provided by Liu Shaozong, Tan Xin 1983.

Figure 12. The general plan of the courtyard design of the Fragrant Hill Hotel, provided by Liu Shaozong 1983.

“On 24 May 1979, the Landscape Bureau reported that the renovation plan of the Fragrant Hill Hotel would cut down 485 ancient pines and cypresses, which would severely damage the scenic area of Fragrant Hill as well as the greening project. On 5 September, the Beijing Municipal Infrastructure Commission replied: according to the layout of the design scheme, 31 cypress and tulip trees could be cut down within the hotel site, and the others should be preserved as far as possible. On 19 May 1980, a meeting was held at Fragrant Hill to study issues relating to the protection of trees and the construction of the new hotel. On 25 June 1982, Fragrant Hill Park reported to the Landscape Bureau the fact of cutting down 245 trees during the construction of the Fragrant Hill Hotel, including more than 70 trees aged over 100 years old.” (Fragrant Hill Park Administration Citation2001, 34-37)

In contrast to the case of trees being cut down and replanted, I.M. Pei remade the Qianlong years’ Water Maze (流觞曲水) in its original form in the design of the Fragrant Hill Hotel. As it was recorded by Cannell (Citation1995, pp. 316–317):

“The relics left on the Fragrant Hill site included a gray marble platform, known as a liu shui yin, carved with a serpentine channel. According to legend, poets floated wineglasses down the Water Maze in the moonlight. They were permitted to drink only if they could compose a poem in the seven or so minutes it took the slow-moving current to carry a glass to the end of the 165-foot passage. This particular liu shui yin, one of five left in all of China, was damaged by workmen mixing cement, so Pei ordered a replica cut from a thousand-year-old quarry outside Beijing. He positioned it as an island in an ornamental pond inhabited by goldfish.”

From the photo of the Republican period (), it is clear that the courtyard of the Water Maze occupied a prominent position in the spatial layout. However, the drawings of site conditions provided by the Pei archives at the Library of Congress and Beijing Landscape Bureau respectively diverged graphically. In the former drawing, the Water Maze was still enclosed within the courtyard, while the latter shows that there were only two walls remaining.

Figure 14. Water Maze in the Girls’ School of Protectory, copyright © Beijing Experimental School History Library online archive.

The Water Maze has undergone the most fundamental revision in I.M. Pei’s design (). It was transformed from an enclosed, relatively private space into a public art and sculpture, which is displayed in an open courtyard. I.M. Pei’s choice embodies a modernist reinvention. It was in some ways based on his own interpretation and idealization of Chinese architectural traditions rather than on the restoration of historical accuracy.

4.3. Site layouts

I.M. Pei utilized the southeastern corner of the site, the east-road courtyard in the Qianlong scheme, with four original Sandhills (砂山). In the restoration plan of Yangshi Lei, a combined courtyard was proposed for the southeast corner, reducing the number of Sandhills to two. However, the four Sandhills are still visible on the map of the former Fragrant Hill Hotel site, which indicates that the revisions made during the Guangxu years have not been conducted.

According to I.M. Pei’s Complete Works (Jodidio and Strong Citation2008, 183), “I.M. Pei reversed the traditional Chinese entry from the south to maximize the main garden within existing retaining walls. Combining classic Chinese axiality and spatial sequencing that alternately expands and contracts (not unlike the Forbidden City), the hotel radiates out from the central atrium with guestroom wings shifted asymmetrically to preserve the site’s many trees.” However, if we look at the plans of the five periods, we find inaccuracies in that description. The East Palace Gate should be the main gate among all the original ones. During the Republican era, the main entrance to the Protectory had been reversed from the east one to the north one. People entered the main road of the campus through the North Gate, while the East Gate and the South Gate were the secondary entrances. I.M. Pei adopted the main entrance on the north side and made no modifications. In addition, the map of the preserved trees in the archives of I.M. Pei papers shows the original site before the construction of the Fragrant Hill Hotel (). As it shows, the original central garden was located on the south side and consisted of three parts: a cross-shaped square, the Water Maze and Sandhills.

4.4. Site functions

The differences among the site’s functions during its transformation are particularly noteworthy apart from the differences in the architectural layout. It evolved from a garden to a school, and then from a guest house to a high-standard international hotel. The two larger volumes designed by I.M. Pei are located in the former canteen of the Protectory and the central courtyard of the Jing Yi Garden, which respectively function as cafeteria and lobby at present. Influenced by the American “international style,” I.M. Pei probably instinctively assumed that a modern, high-standard hotel would necessarily accompany a grand lobby and a full-service restaurant. It inevitably increased the footprint of the concentrated volumes, which is difficult to reconcile between the site and function.

Combining a hotel and a Chinese garden also overextended the interior circulations. The original Jing Yi Garden is a grouping of single units according to the organization of traditional Chinese courtyards: “A ‘Jian (间)’ is the unit that forms a single building, a single building forms a courtyard, and a courtyard forms various groups.” (Huang Citation1983, 67) I.M. Pei has deliberately used the meandering volumes to enclose courtyards of different sizes. Still, most of them are linked by interior corridors subordinated to an integrated building rather than by an architectural group consisting of several sequences. The extension of the internal circulation leads to a corresponding increase in energy consumption and a decrease in management efficiency. The 1982 Symposium kept criticizing repeatedly: “It is difficult to guarantee the quality of service as it is about three hundred meters from the rooms at the end of the passage to the main service desk. ”(Guo Citation1983, 68)

5. Two contexts of the site discourse

If the chronological tracing of the site has given a comprehensive context of the design, then the horizontal comparison of the five plans will further reveal the historical reference of I.M. Pei’s spatial treatments. Given the Fragrant Hill Hotel was the catalyst of an architectural controversy around 1983, the attitudes towards the “site” were somewhat divergent in the Chinese and American contexts.

5.1. Criticism of the site in the 1982 Symposium

By reading the 1982 Symposium on the Fragrant Hill Hotel critically, we find that the issue of “site” contributes largely to criticism inside of the country. However, the critics mainly took the economic practicality as the main reason for that criticism, which to some extent undermined the information of “reconstruction”. In a summary of 17 experts’ speeches compiled by Gu Mengchao, a total of 11 experts mentioned the issue of “site.” The arguments centered on three aspects. (1) The hotel is too far from the city to reach conveniently. (2) The sizable volume will disfigure the landscape. (3) Building in a scenic area will lead to an extensive investment in the infrastructure of water, electricity and sewage discharge, which is not economical ().

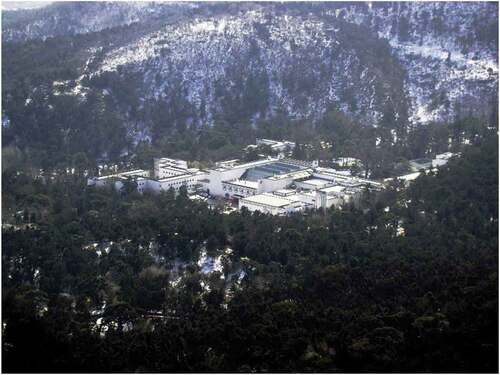

Figure 16. An aerial photograph of the Fragrant Hill Hotel. The building’s color and massing are distinctly different from its surroundings, which Chinese experts in the Symposium widely criticized. Photograph by Yang Jing.

In contrast, there were only four references to “I.M. Pei’s reconstruction of the Fragrant Hill Hotel occupying the ancient Jing Yi Garden,” and three of these statements were brief. As Liu Kaiji emphasized, “The site was inappropriately chosen. Leave aside the occupation of the ancient gardens by the Fragrant Hill Hotel, it is also difficult to attract foreign tourists due to the hotel’s distance from the city, its inaccessibility, and the lack of facilities for tourists.” According to a written statement by Li Daozeng and Guan Zhaoye, “Trespassing on public gardens has harmed the environment to some degree. It shows mainly accomplishments in the destruction of the landscape, which is all the more unfortunate as the Fragrant Hill Park is a famous scenic spot evolving from the former imperial garden of the Qing Dynasty.” Ma Mingyi, on the other hand, noted from a technical perspective that “The building site, which was originally the Jing Yi Garden and the Protectory, has undergone several manual leveling and transformation, resulting in volatile lithology and uneven soil quality.” (Gu Citation1983a)

Only Fu Xinian in the Symposium emphasized the effect of the reconstruction. From the perspective of historical heritage conservation, he affirmed the aforementioned experts’ criticism that the Fragrant Hill Hotel “is a good building built in an inappropriate location.” He also stressed that the occupation of the ancient gardens was the main reason for its “inappropriateness.” In addition, Fu Xinian’s presentation referenced the site’s original appearance and conservation value:

“After its destruction by the British and French forces in 1860, only a few remnants of the Jing Yi Garden survived. However, the original site is still identifiable, and the archives possess maps of the original state. The low-standard buildings built in the Republican era are easy to remove, and the restoration conditions are better and less expensive than those of the Yuan Ming Garden. If gradually rebuilt, it is good news for the capital since an important historical garden could be restored afterward. However, the new-built Fragrant Hill Hotel, a building with a different style and tone, has damaged the original Chinese landscape and the atmosphere of the monuments, making it extremely difficult to reconstruct the Fragrant Hill.” (Gu Citation1983a, pp. 61-62)

In the early years of China’s reform and opening up, experts and scholars usually chose relatively cautious rhetoric for the semi-public symposiums, trying to approach the collective goal of “modernization.” It led to examinations of economic practicality outweighing concerns about the site’s history in the Fragrant Hill Hotel Symposium. Roskam (Li Citation2017) once praised I.M. Pei’s courage in experimenting with “localness” in the design of the Fragrant Hill Hotel, arguing that “for Chinese people who have just experienced the Cultural Revolution, it is sensitive to talk about history and tradition. People will reflexively associate them with the remnants of feudalism.” It is debatable whether this assessment is appropriate for I.M. Pei, who has lived in the United States and has been away from China for dozens of years. Still, perhaps experts and scholars in China were even more empathetic. However, it is noteworthy that four more articles discussing the occupation of the ancient gardens were published in the same issue of the Jianzhu Xuebao that recorded the symposium.

Landscape architects Liu and Tan (Citation1983) noted that the original buildings of the Jing Yi Garden did not exist anymore on the site, but that “the present road system and remnants of the site reflect the original pattern.” Professor Zhu (Citation1983) of Tsinghua University mentioned that the former Fragrant Hill Hotel was damaged after the Tangshan Earthquake in 1976. In terms of the site reconstruction, “it was originally a good opportunity to renovate the classical garden,” but instead, “the pattern of the garden was irreparably damaged by the construction of the new Hotel.”

Ouyang (Citation1983), the architect of the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design, examined the historical nature of the site. He pointed out the role of the site from a garden to a reconstruction of the former Fragrant Hill Hotel. As for its role as a garden, he argued that the Fragrant Hill Hotel resulted from I.M. Pei’s extremely liberal approach to choosing the site, which did not match the general reality of the Chinese architectural profession. Therefore it was out of typical significance. In terms of its role as a reconstruction, he criticized that “The remains should be reconsidered in the light of the overall planning of the Jing Yi Garden. There is no good reason why it must be rebuilt on an expanded scale from the original.”

The architectural commentator Gu (Citation1983b) gave a further critical comment. “The designers overthought how the small environment of the ‘precious land and trees’ of Fragrant Hill would benefit the hotel. They did not pay enough attention to the larger context of the city’s master plan. As a result, the design cast a poor choice of location and hence made the mistake of occupying the old site of the Jing Yi Garden, bringing about many conflicts in the protection of monuments, hotels, and park management. The architects were also responsible for the inappropriate site choice and the hotel standard.” Different from most critics, Gu did not seem to attribute the disadvantages of the Fragrant Hill Hotel entirely to I.M. Pei’s design failures. He weighed the site’s legitimacy objectively, implying that planning decisions are also responsible for the disadvantages.

5.2. Overlap between the two discursive types in the American context

The above criticism was made in the absence of I.M. Pei. It would trigger our curiosity about Pei’s response if he were present. In the three interviews of the 1980s given by I.M. Pei in the Chinese context, neither the history of the site nor the reconstructive nature of the project was mentioned. It is only in Beijing Daily (Wang Citation1982) that Pei mentioned something about the aforementioned two items. In the newspaper, he spoke of his love for the natural scenery of Fragrant Hill and iterated that his first intention was “not destroying the stunning scenery but preserving the beautiful trees”.

The beauty of the natural landscape and the history of the “imperial hunting park” almost define the site’s identity in American critiques. Fewer critics mentioned the existence of a “deteriorated hotel” on the site. Only one critic mentioned the Jing Yi Garden, but no one ever mentioned the influential Protectory in the Republican era. The earliest description came from a report by the journalist Wren (Citation1982) published in The New York Times a week after the opening of the Fragrant Hill Hotel: “The hotel, which the Chinese say cost about $25 million, covers 397,000 square feet on the site of an old imperial hunting lodge.” The architecture critic Goldberger (Citation1983) also commented in The New York Times:

“He chose to build a new hotel at Fragrant Hill Park, a rural area near Peking that had long had a small and rather primitive resort hotel. … It is a site of magnificent trees, many of which are quite old, and it is nestled in a cradle of mountains.”

A month later, Connoisseur published a lengthy review by Thomas Hoving (Citation1983, pp. 72), former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, recording I.M. Pei’s typical description of the site:

“‘Then we went to a place that intrigued me,’ he continues. ‘It was a great public park in Fragrant Hill, a park which was once an imperial hunting preserve. The people revere it. There are thousands of trees there—some of them centuries old. It was perfect. There was a deteriorated old hotel that could come down. I felt certain the Chinese would want a building that would not destroy the green.’”

In April, William Walton (Citation1983, p. 182), a close friend of I.M. Pei, mentioned: “The region is soaked in historical associations. The hotel occupies a corner of a national park, Jingyiyuan, meaning Park of Tranquility and Rest, site of a palace built in 1186. All of it, like so many choice sites in China, was once an Imperial garden.” Although it is difficult to define why Walton would date Jing Yi Garden back to 1186 (indeed it took shape and got its name in the 18th century), Walton’s description is the only English-language critique that currently mentions the site’s originality as an imperial garden.

The site descriptions in several English-language biographies of I.M. Pei primarily relied on accounts from 1983. Descriptions of “Fragrant Hill” often appear in the context of I.M. Pei’s famous refusal to build a high-rise in the center of Beijing, which was followed by his first visit and choice of Fragrant Hill. It was mainly described as a “former imperial hunting park” versus the less frequently mentioned “existing deteriorated hotel” (Wiseman Citation1990, 190; Cannell Citation1995, 304).

Of particular note is a 1996 interview with I.M. Pei by Janet Adams Strong, who held the position of Director of Public Relations at I.M. Pei’s office (Jodidio and Strong Citation2008, 350):

“The fact that such privileged land could be secured ‘was nothing short of miraculous,’ said Pei. ‘It was occupied by a cheap hotel with outdoor plumbing. Terrible! Nature was so beautiful and the man-made buildings were a disgrace. As soon as I saw those magnificent trees, I knew this was where I wanted to build.”

As I.M. Pei rarely wrote personally, we can hardly retrace his words from resources except for the writings of journalists, critics and biographers. Conversely, the terms of I.M. Pei and his architects turned into the most important sources about the Fragrant Hill Hotel for Western authors. This leads to an intriguing phenomenon. That is, I.M. Pei’s words helped construct the Western authors’ writings, so that the discourses from these two identities overlapped greatly. As it appears, the site description in English is mainly around three points: the beautiful natural surroundings and trees, the former imperial hunting park, and the existing deteriorated hotel. In contrast to the overwhelming emphasis on the first point, the latter two are only attached to the scenario in which I.M. Pei chose Fragrant Hill as a perfect site.

The Fragrant Hill Hotel was awarded the Honor Award by the American Institute of Architects in 1984. Regardless of the ambiguity over whether the Fragrant Hill Hotel is a Chinese architecture or an American one, there presents a rare “architect’s statement” under the Jury Comment: “The hotel is located on a 30,000-square-meter walled site within the Fragrant Hill Park. … This park is famous for its beautiful scenery. Once a part of the Imperial hunting grounds, it contains many well-known temples.”

This quotation can be regarded as I.M. Pei’s most straightforward description of the site. However, I.M. Pei’s description obviously contradicts criticism in the Chinese context, the facts of the construction process, and the widely known history of Fragrant Hill in the following three points. He exceedingly appreciated the trees on the site and promised to preserve them to the possibly greatest extent, but in the end, hundreds of them still died. In addition, he made very few references to the existence of a deteriorated hotel on the site, but Chinese scholars claimed that the garden pattern was still clearly identifiable. Most importantly, it’s pretty unfamiliar to describe the Jing Yi Garden as “former imperial hunting grounds” in the Chinese context. Suppose we suspend the inconsistent testimony in the first two points, namely the beautiful trees, and the existing deteriorated hotel and then we consider the third point, that is, the former imperial hunting park from a historical perspective. Fragrant Hill was indeed a hunting park in Liao and Jin dynasties. But the Western Hills of Beijing, including Fragrant Hill, had evolved into imperial gardens that functioned as temples and palaces in Qing Dynasty. Meanwhile, major hunting activities have shifted to the Mulan Hunting Ground (木兰围场) near the Mountain Resort in Chengde (承德避暑山庄). (Siu Citation2013, 205) Thus the Fragrant Hill is usually described as part of the imperial gardens, a scenic area with a collection of famous monuments, without any deliberate emphasis on being hunting grounds in most Chinese discourses. Why would I.M. Pei pass over its nearer history of being an imperial garden and describe it as the hunting grounds whose history dates back to an older period?

5.3. The hidden self-contradiction in the site discourse

From the existing research on Fragrant Hill in English, it appears that the term “hunting grounds” may be a more common Western concept of Manchu nomadic gardens. It can be traced back to Malone’s book (Citation1934), “History of Peking Summer Palaces under the Ch’ing (Qing) Dynasty.” However, I.M. Pei should have known that the site used to be the former Qing imperial Jing Yi Garden when he designed the Fragrant Hill Hotel, as inferred from Walton’s article. Besides, I.M. Pei consulted several experts during the design process. He was close friends with the garden expert Chen Congzhou, who visited the site together with Pei on several occasions. (Wiseman Citation1990, 201) It is clear that I.M. Pei had the opportunity to be well informed about the history of Fragrant Hill from a Chinese academic context. In addition, the Sandhills, the Water Maze, the surrounding traditional pavilions, and several terraces should still be present before the 1980s’ reconstruction according to the metric map (). Therefore, it can be inferred that what Pei saw was not just a “cheap hotel,” but an identifiable garden pattern. Moreover, I.M. Pei retained the Water Maze in his design. He never withheld the fact that it was a site relic, rather, he featured it as a symbol of the literati tradition. When the Water Maze was inadvertently damaged during the reconstruction, he spared no expense in restoring it and positioned it in the center of the central garden. The Water Maze demonstrates the self-explanatory nature of the classical garden system. Therefore, it seems untenable to suggest I.M. Pei just followed the Western knowledge of Fragrant Hill as hunting grounds.

When faced with a site, an architect’s emotions and intuition often prevail over the precision of historical facts. It is perhaps inconsequential to dwell on the terms “hunting grounds” and “imperial garden.” Nevertheless, if we consider that the Fragrant Hill Hotel is a project that has been extensively “debated,” it remains intriguing to reflect on I.M. Pei’s reticence about the site remnants in the Chinese context, and the many contradictions in his American expression. The phrase “former imperial hunting grounds” is perhaps more of strategic rhetoric than the fact of “reconstruction on the site of an imperial garden and existing buildings.” On the one hand, it obscures the site’s existence as a built rather than a natural environment for at least the last three centuries. On the other, it subtly transgresses the ethical criticism involving damaging the original appearance of a historical site.

I.M. Pei’s expression of the site’s history might be considered a trick to avoid or blur the focus on its originality, and this consideration seems to reflect precisely his self-contradiction in the design. I.M. Pei advised the Chinese government “not to build high-rise buildings near the Forbidden City” in 1978, and famously refused the design commission for a high-rise hotel on Chang’an Avenue. He has mentioned proudly on several occasions that if he had moved the government in any way toward the new policy (which refers to the guidelines for future construction in Beijing), it was “my major contribution to China.” (Wiseman Citation1990, 191) In several lectures to Chinese architecture students, I.M. Pei earnestly reminded them that “a new form, a new creative path for modern Chinese architecture must emerge precisely from China’s own traditional architectural pattern.” He also emphasized that the design of the Fragrant Hill Hotel was “to find a way to nationalize Chinese architectural creation (Wang Citation1990, pp. 253–255).” However, in his practice, I.M. Pei demolished a site with such a rich history and built it almost totally by his own design. Hundreds of trees were cut down because of the reconstruction, despite Pei enthusiastically praising and promising to preserve them.

We are not meant to be critical or accusatory with the benefit of hindsight. As Liu (Citation2009) points out, “The Fragrant Hill Hotel may have accomplished a comprehensive attempt to be so-called ‘Chinese yet new,’ but it may not be a thoroughgoing ‘base’ experiment in Fragrant Hill. This is one of Pei’s regrets. When the vision is too high, it always drifts into vagueness; when the ‘culture’ is not implemented into the site, it always drifts into universality.” I.M. Pei was perhaps more concerned with the higher value of the project, rather than the design of a hotel on the site of Fragrant Hill. For I.M. Pei, this project will bring about two kinds of self-fulfillment: his cultural vocation as an overseas Chinese, and his professional ambition as an architect. Once these two kinds of self-fulfillment have come together to construct I.M. Pei’s design intention, the “site” is no longer an actual design condition and physical space, but an imaginary reference to Pei’s concept of “China.”

Jing Shuping, who was a classmate of I.M. Pei at St. John’s University and later became a famous banker, once said: “People of our generation in China had for so long felt humiliated by foreigners, whether British, American, French, or Japanese. We always secretly thought that we should stand up for China, because her culture was so old. When l.M. and I got together, I sensed this feeling in him. … When Ieoh Ming told me about Fragrant Hill, I knew it was more than just a hotel for him. Every Chinese is very proud of our ancestry, and he said that he wanted to develop some kind of architectural language to leave to our descendants.” (Wiseman Citation1990, pp. 191–192)

Imagine I.M. Pei when he first saw Fragrant Hill. The twice-burned garden ruins and the deteriorated hotel may have stimulated him to change the site so that it would become a contribution to his imaginary “China.” His nationalist sentiments as a Chinese and the instinct as a modernist architect possibly far surpassed his historical sensitivity at that moment. To some extent, I.M. Pei in 1978 was being empowered by the Chinese government to practice “reform” through his reputation and talents in design. Because international hotels crucially characterized China’s modernization in the early years of reform and opening up by symbolizing the image and strength of the country. Thus, rather than being attentive to the stylistic character and strategy of the new design, the government was more concerned with proving its ability to invite such a renowned Chinese-American architect as I.M. Pei to design an international hotel. The corresponding propaganda and political significance conveyed the determination of the government and showed the brand new appearance of the country under the policy of economic reform. The motive and act of maintaining historical sites, which were usually presented in an ambiguous manner, were largely replaced by the undeniable “progress”.

But at any rate, the Fragrant Hill Hotel is an architecture interwoven with conflicts. It was claimed to be a modern exploration out of Chinese tradition and culture, but the authenticity of its site is obscured in the actual treatment at the outset of the design. Pei kept reticent in the Chinese context to conceal the conflict while opting for strategic rhetoric in the American context. For this reason, most Western authors who have not visited the Fragrant Hill Hotel relied mainly on I.M. Pei’s statements, and hence had no way of knowing the historical narrative behind the Hotel as a reconstruction project. More unfortunately, the critical voices of Chinese experts, who were once legitimately outraged by the reconstruction of the site, were slowly drowned in the dusty archives of the time.

6. Discussion

Taking the “site” of the Fragrant Hill Hotel as a theoretical perspective for conducting architectural criticism, this paper explores the duality of the Hotel as a design project and a discursive system in both Chinese and American contexts. The paper challenges the discursive analysis of the Chinese perspective that began with the Fragrant Hill Hotel Symposium in 1982. In addition, it contests the heroic narrative of “I.M. Pei’s return to China” and its implied sense of novelty from an American perspective.

Historical archives and resources are keystones in analyzing the site’s transformation. The research looks for historical connections across a wider chronological range in order to explain several arguments that have remained unclear in earlier studies. The formal analysis makes significant observations about choices such as: the extensive tree cutting, the postmodern interpretation of historical allusions like the Water Maze, the hotel’s new boundaries, the challenges posed by the hotel’s enormous scale and occupation of the original gardens, as well as the difficulties with circulation caused by the new volumes.

When examining the discursive formation of the Fragrant Hill Hotel, one central problem is the subjective perspective of architectural criticism. In the 1980s, Chinese and American critiques of the Fragrant Hill Hotel revealed vast differences in the perspectives they chose to criticized a work. This is due to the long isolation before. One of the most significant differences was that Chinese critics tended to focus on the ways and means of modernizing Chinese architecture, while American commentators tended to observe China’s reform and opening up through I.M. Pei’s return.

Recent Chinese studies can be divided into two groups: one focuses on the Fragrant Hill Hotel Symposium; the other takes the English biographies of I.M. Pei as a source and encapsulates the Fragrant Hill Hotel in the discussion of postmodernism. We argue that these two forms of writing kept the dichotomy between Chinese and American critical discourse of the 1980s. This reduced the Fragrant Hill Hotel to an undefined symbol and a misinterpreted discourse by both the Oriental and Western camps, while critiques of design remain elusive.

This research has potential limitations. Although our inference regarding I.M. Pei’s cultural identity is supported by a range of evidence and reasoning, it remains a generalized speculation because I.M. Pei never explicitly explained the design specifics of the site during his lifetime. To ensure the relative neutrality of the inference, we draw attention to the discrepancies between Pei’s design and his rhetoric through the analysis of archives, texts, and images, and place his words in the context in both China and the United States.

The paper focuses on two periods when criticism of the Fragrant Hill Hotel reached its climax: 1982–1983, following the hotel’s completion, and 1990, following I.M. Pei’s announcement of his retirement from PCF and the release of multiple biographies in English. Two further areas of study need particular consideration if the chronological frame is stretched: (1) The contradictions of viewing the Fragrant Hill Hotel as a modern or postmodern architecture in the context of China and the United States. (2) The recent-proposed views on the nationalism and regionalism of I.M. Pei’s cultural identity.

7. Conclusion

Taking the “site” as a narrative thread, this paper attempts to explain the complex entanglement between the historical background of the Fragrant Hill Hotel and I.M. Pei’s cultural identity. For this purpose, it combined discursive analysis and formal analysis, which have been proven to be two critical methodologies in the field of Architectural History, Theory and Criticism. The proposed methodology employs a comprehensive examination of the site’s transformation and the various discourses underlying the Fragrant Hotel’s reception in both the American and Chinese architectural milieus to achieve the historiographical criticism of I.M. Pei’s design.

The contradictions that entwine the Fragrant Hill Hotel have stimulated the curiosity and desire for further explanation, keeping the architectural discourse vibrant to this day. If the process of unearthing historical material is like exploring for unknown petroleum in a stratum, then understanding the implications of the discourse is more like cross-examination in forensic science. Perhaps it is no longer possible to fully collate the truth about the Fragrant Hill Hotel regardless of the number of exposed facts. It is even more challenging to quantify the proportion of the various influences. Nevertheless, only by situating the Fragrant Hill Hotel in I.M. Pei’s architectural career, which encompasses both Chinese and Western cultures, can we gain a more comprehensive perception and understanding of the motivations and commitments behind the building. Conversely, this gives rise to a cultural echo that goes beyond architectural design.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the M+ Museum’s curators, Shirley Surya, Fei Tse, and Aric Chen for providing essential materials. In writing this paper, Architect Liu Yanchuan and Associate Professor Yang Jing of Tianjin University offered valuable advice. Sincere appreciation to the reviewers for their enlightening comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xuerui Wang

Wang Xuerui is now a visiting scholar at GTA, ETH Zurich and a PhD candidate at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University. This paper is based on her curatorial research for the 2023 I.M. Pei exhibition at M+ Museum, Hong Kong.

Xiangning Li

Li Xiangning is now the dean and professor at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University.

Notes

1 These temples included Yong’an Temple (永安寺), Jinshan Temple (金山寺), Biyun Temple (碧云寺), and Hongguang Temple (洪光寺).

2 The hotel at that time covered the area of Fenglin Village, Kindergarten of Protectory, East Court of Wofo Temple, Red Leaf Village and eight villas on the hill, which could accommodate thousands of people.

References

- Cannell, M. 1995. I.M. Pei: Mandarin of Modernism. Danvers: Clarkson Potter.

- Chen, A. (2017, October 6). I. M. Pei’s Groundbreaking Fragrant Hill Hotel, Revisited. Retrieved from https://www.mplus.org.hk/en/magazine/i-m-peis-ground-breaking-fragrant-hill-hotel-revisited

- Chen, F., and C. Guo. 2012. “Xiangshan Fandian Xiaoji [A Short Note on the Fragrant Hill Hotel.“ In Chen F, Baifang Jinghua Mingjia [Visiting Beijing Celebrities], edited by Y. Sun, 228–242. Beijing: Central Literature Publishing House.

- Fang, X. 2008. “Beiyuming de Xungen Zhilu: Cong Xiangshan Fandian Dao Suzhou Bowuguan [I.M. Pei’s Journey to His Roots: From the Fragrant Hill Hotel to Suzhou Museum.” In Wei Zhongguo Er Sheji: Jingwai Jianzhushi Yu Dangdai Zhongguo Jianzhu [Designing for China: Foreign Architects and Contemporary Chinese Architecture], edited by D. Yang and D. Li, 14–49. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Fragrant Hill Park Administration. (2001). Xiangshan gongyuan zhi [Fragrant Hill Park Chronicles]. Beijing: China Forestry Press.

- Goldberger, P. (1983, January 23). “I.M. Pei Rediscovers China.” The New York Times, Section 6, pp. 27.

- Gu, M. 1983a. “Beijing Xiangshan Fandian Jianzhu Sheji Zuotanhui [Architectural Design Symposium of the Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing].” Jianzhu Xuebao 03: 57–64+83.

- Gu, M. 1983b. “Cong Xiangshan Fandian Tantao Beiyuming de Sheji Sixiang [Exploring I.M. Pei’s Design Ideas from the Fragrant Hill Hotel].” Jianzhu Xuebao 04: 61–64.

- Guo, Y. 1983. “Cong Jingying Jiaodu Kan Xiangshan Fandian [Fragrant Hill Hotel from a Business Perspective].” Jianzhu Xuebao 03: 64–69.

- Hoving, T. 1983. “More than a Hotel.” Connoisseur 2: 68–81.

- Hu, H. 2014. “Dang tamen tanlun “xiandai jianzhu” shi, tamen zai tanlun shenme? 1980-1982 niande jianzhu xuebao yu xiangshan fandian [What are they talking when they talk about ‘Modern Architecture’?—The Architectural Journal and the Fragrant Hill Hotel, 1980-1992].” Jianzhu Xuebao Z1: 40–45.

- Huang, M. 1983. “Xiangshan Fandian Sheji de Deshi [The Gains and Losses of the Design of the Fragrant Hill Hotel].” Jianzhu Xuebao 04: 65–71.

- Ji, H. (1982, November 8). “Beiyuming de xin yuezhang [I.M. Pei’s ‘New Melody’].” Renmin ribao, Section 2.

- Jodidio, P., and J. Strong. 2008. I.M. Pei: Complete Works. Rizzoli International Publications.

- Li, S. 1937. Yandu Mingshan Youji [Travels to Famous Mountains in Peking], 56–57. Peking: Bei Xin Bookstore.

- Li, N. (2017, May 4). “30 nianqian de guoji fandianmen, shi ruhe zaizhongguo kaiqile yichang jianzhu he shehui de shuangchong shiyan? [How did the international hotels started a double experiment of architecture and society in China 30 years ago?].” Retrieved from http://www.qdaily.com/articles/40403.html2017-05-04

- Liu, D. 2009. “Chongwen Yici Zhujue Quexide Zuotanhui [Remembering an Official Seminar about I.M. Pei’s Fragrant Hill Hotel at His Absence].” Time + Architecture 3: 52–54.

- Liu, S., and X. Tan. 1983. “Beijing Xiangshan Fandian de Tingyuan Sheji [The Garden Design of Beijing Fragrant Hill Hotel].” Jianzhu Xuebao 04: 52–58+84.

- Li, J., and J. Yang. 2020. “Yangshilei Tuzhi Shangde Xiujian Jihua: Jiedu Wanqing Jingyiyuan Chongxiu Fangan [The Construction Plan in Yangshi Lei Archives — Reading of the Restoration Project of Jingyi Garden in Fragrant Hill in the Late Qing Dynasty].” Jingguan Sheji 02: 30–37.

- Malone, C. 1934. History of the Peking Summer Palaces under the Ch’ing Dynasty. Urbana: University of Illinois.

- Ouyang, S. 1983. “Xiangshan Fandian Chufang [First Visit to the Fragrant Hill Hotel].” Jianzhu Xuebao 03: 70–74.

- Qianlong, E. 1746. “Yuzhi Jingyiyuan Ji [A Record of the Imperial Jing Yi Garden.” In Rixia Jiuwen Kao [Old News under the Sun], edited by M. Yu, 1437–1438. Beijing: Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House.

- Qian, Y., and J. Zhang. 2020. “Beijing Xiangshan Jindai Jianzhude Lishi Yu Xianzhuang [The History and Current Situation of Modern Architecture in Beijing Fragrant Hill].” Sanshan Wuyuan Yanjiu 01: 194–210.

- Roskam, C. (2015). “Envisioning Reform: The International Hotel in Postrevolutionary China, 1974-1990.” Grey Room, 58, 84–111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43832223

- Roskam, C. ( Lecturer). (2017). “The Fragrant Hill Hotel: Reassessing the Politics of Tradition and Abstraction in China’s Early Reform Era [Lecture].” Retrieved from https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/event/rethinking-pei-a-centenary-symposium

- Siu, V. 2013. Gardens of a Chinese Emperor: Imperial Creations of the Qianlong Era, 1736-1796. Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Lehigh University Press.

- Walton, W. 1983. “New Splendor for China.” House & Garden 04: 95–103+180+182.

- Wang, J. (1982, October 18). “Beiyuming Tan Xiangshan Fandian [I.M. Pei on Fragrant Hill Hotel].” Beijing Daily.

- Wang, T. 1990. I.M. Pei. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.

- Wiseman, C. 1990. I.M. Pei: A Profile in American Architecture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers.

- Wren, C. (1982, October 25). “I.M. Pei’s Peking Hotel Returns to China’s Roots.” The New York Times, Section C, pp. 13.

- Xiong, X. 1920. “Zai Xiangshan Ciyouyuan Kaiyuanshi Shang de Baogao [Report on the Opening Ceremony of the Fragrant Hill Charity School.” In Xiong Xiling’s Collection, edited by Q. Zhou, 375–378. Vol. 7. Changsha: Hunan People’s Publishing House.

- Xiong, X. 1922. “Xiangshan Ciyouyuan Chuangbanshi [History of the Founding of the Fragrant Hill Charity School.” In Xiong Xiling’s Collection, edited by Q. Zhou, 551–557. Vol. 7. Changsha: Hunan People’s Publishing House.

- Zhu, C. 1983. “Fengjing Huanjing Yu Lyuyou Binguan: Ping Xiangshan Fandian de Guihua Sheji [Scenic Environment and Tourist hotels–Review of the Planning and Design of Fragrant Hill Hotel].” Jianzhu Xuebao 04: 59–60.

- Zhu, Y. 2009. “Cong Xiangshan Fandian Dao CCTV: Zhongxi Jianzhude Duihua Yu Zhongguo Xiandaihuade Weiji [From Fragrant Hill Hotel to CCTV: Architectural Dialogue between China and the West and the Crisis of Chinese Modernization.“ In Zhu, Y., Houjijin Shidai de Jianzhu Biji [Architectural Notes for the Post-Radical Era], edited by Z. Li, 177–187. Shanghai: Tongji University Press.

- Zou, D., L. Dai, and X. Zhang. 2010. Zhongguo Xiandai Jianzhushi [Chinese Modern Architecture History]. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.