ABSTRACT

The Gyeonghoeru Pavilion was built during the Joseon Dynasty. It is a historical representative of Joseon’s architecture, both internally and externally. It once served as a venue of entertainment for important people, and today, it is often used as the backdrop for modern entertainers’ music videos. Even after the entire Gyeongbokgung Palace was burned down during the Japanese Invasion of Joseon in 1592, it remained for 270 years as a symbol of Gyeongbokgung Palace. Finally, Gyeongbokgung took 1,000 days to rebuild, but more than half of the time was devoted to the reconstruction of Gyeonghoeru. It took so long is because the construction methods of the nineteenth century were implemented while preserving the construction methods of the early fourteenth century. After 150 the construction of Gyeonghoeru and the pond required complex civil engineering, gardening, masonry, and woodwork, as well as a tremendous amount of labor. Gyeonghoeru’s restoration was explicitly stated as serving architecture and cultural heritage above all else, and not just political or social factors.

1. Introduction

Gyeongbok Palace (景福宮) was built following the traditions of Joseon architecture. It served as the main palace of the Joseon dynasty and has long remained symbolic of the dynasty’s prestigious reign. In the Japanese Invasion of Joseon in 1592 led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Gyeongbokgung Palace was burned and laid to ruin. It remained abandoned for about 270 years before its reconstruction began in April of 1865, the second year of King Gojong’s reign.

Among the buildings in the Gyeongbokgung Palace complex, the Gyeonghoeru Pavilion (慶會樓) was the only building where the stone columns on the first floor had been left standing. The pavilion was constructed to embody Neo-Confucian philosophy, the ruling ideology of Joseon. It is located on a square pond within the palace and served to receive foreign envoys and host royal banquets. Taepyeong-gwan (太平館), Dongpyeong-gwan (東平館), and Bukpyeong-gwan (北平館) were legations that served as accommodations for envoys from the Chinese Ming and Qing dynasties and from Japan. Gyeonghoeru, on the other hand, was a banquet space close to the private quarters of the sovereign, and subjects sought harmony within the palace. Qing’s Ziguang Pavilion (紫光閣) in Beijing was similar in construction,Footnote1 and pavilions adjacent to a pond within a palace, Yeonuru (煙雨樓), the Chengde Qing Dynasty’s summer palace, and Japan’s Katsura Imperial Villa (桂宮) are also comparable (Kim Citation2007).

During the Joseon dynasty’s reign, Gyeonghoeru Pavilion became the symbol of Gyeongbokgung Palace. Before the Japanese invasion of Korea in 1592, it was a spectacular example of Joseon architecture and scenic beauty. It remained the only “memory” of the previous Gyeongbokgung Palace once the pavilion was destroyed by Hideyoshi. The pavilion was a central feature of the palace restoration, for which the entire kingdom’s efforts were mobilized in the nineteenth century. At the time, it was the only architecture of its scale and glory. More than two centuries after its destruction, it was reborn, combining original fourteenth-century and newer nineteenth century techniques and architectural styles.

The reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung Palace in the nineteenth century was a project that lasted one thousand days and employed three thousand workers daily. It was the last construction of the Joseon dynasty, and it reflected the “old system” and changing conditions of the existing site. Despite its gargantuan difficulty, the project was necessary to restore the legitimacy of the royal family and secure its authority. The restoration was a symbol of unity for the people and was long desired by the Joseon family. The reconstruction was much larger than the fourteenth century Gyeongbokgung Palace. The scale and importance of the reconstruction have meant that this project is often studied for its historical and political importance. But the true value of the Gyeongbokgung Palace restoration is in its architectural accomplishment. However, the palace has seldom been evaluated for its architecture because there are no records of its construction specifications until we discovered the Yeonggeon Chronicle (景福宮營建日記; A Daily Record of the Construction of Gyeongbokgung Palace) in Japan in 2018. Architectural research on Gyeonghoeru had only been carried out to the extent of analyzing the architectural concept of the upper half of the pavilion by considering Gyeonghoerujeondo (慶會樓全圖; which is in the collection of the National Library of Korea and Waseda University in Japan (Cultural Heritage Administration, Citation2000).

Until the Seoul Institute of History discovered The Palace’s Yeonggeon Chronicle, held by Waseda University, Japan, the nineteenth-century reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung Palace (Historic Site) was recorded only as a political event due to the lack of detailed records on the reconstruction process.

It came to light that a complete version of the Gyeongbokgung Yeonggeon Chronicle is present in Japan’s Waseda University Library, and Seoul Historiography Institute published a complete translation in 2019. Until now, the reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung Palace was only a political event symbolizing the economic and social trends of the Joseon Dynasty and the confrontation between the royal and the divine powers. Despite the physical reality of buildings and land, research in the field of architecture only dealt with the appearance of the early 14th century and the mid-15th century. In other words, after the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592, Gyeongbokgung Palace had no choice but to rely on abstract painting materials. There have been few studies on architectural activities in the 19th century that can explore today’s Gyeongbokgung Palace. However, the discovery of Yeonggeon Diary made it possible to study Gyeongbokgung Palace in the 19th century. Consequently, further research is being conducted (Seoul Historiography Institute Citation2019).

The Yeonggeon Chronicle is a record of the daily process of Gyeongbokgung construction period written by the directorate responsible for the execution of the actual construction. The amount is huge, so you can check the construction process of all the halls of Gyeongbokgung Palace. It is a useful and unique source as it reflects the political economic circumstances of the time, and it is a valuable source to understand the realities of the late Joseon construction industry, since it has records of the atmosphere of the construction site from a person who was actually involved in the construction.

This study is based on the investigation and analysis of the stone reconstruction of Gyeonghoeru Pavilion (National Treasure) from the Chronicle. The Gyeonghoeru record shows a wide variety of information, such as who led the construction, where the quarry was located, how they moved to the construction site after quarrying, and who the masons were.

Thus, this study will consider the masonry construction involved in the nineteenth century reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung Gyeonghoeru, in the order that it was recorded in the Yeonggeon Chronicle. We hope to understand the significance of Gyeonghoeru’s construction in the architectural history of the Gojong period by unpacking the masonry construction, which took up the most time and money in the reconstruction of Gyeonghoeru.

2. Masonry construction mentioned in the Yeonggeon Chronicle

Gleaning information about the construction of the palace from the two existing records of the palace – The Daily Records of the Royal Secretariat of the Joseon Dynasty (承政院日記) and The Diaries of the Kings of Joseon (日省錄) – has proven to be difficult because the details therein were recorded according to the king’s insight. This changed with the revelation of a complete version of the Gyeongbokgung Yeonggeon Chronicle (營建日記; a Chronicle of the Construction of Gyeongbokgung Palace) at Japan’s Waseda University Library. In 2019, Seoul Historiography Institute published a complete translation (Seoul Historiography Institute, Citation2019),Footnote2 triggering research on the subject (Kim and Jo, Citation2020).

The Yeonggeon Chronicle recorded the daily construction of Gyeongbokgung. It was written by the directorate responsible for executing and being involved in the palace’s actual construction. It proves to be a useful source for detailed notes on the political and economic state of affairs at the time as well as insights on the realities of construction then. The contents of the Yeonggeon Chronicle of Gyeongbokgung Palace thus provide the best insights into the architectural value of the palace within the context of architecture and construction in the nineteenth century.

According to records, Gyeonghoeru could hold 1,200 people within the pavilion. Not only was its size impressive, but its magnificence was exemplary, and many foreign envoys who visited the pavilion from the early Joseon period wrote poems about it. After the Japanese 1592 invasion and subsequent sacking of the pavilion, only the stone columns and the square pond of Gyeonghoeru remained to prove the existence of Gyeongbokgung.

In contrast to the other destroyed villas in Gyeongbok Palace, then, Gyeonghoeru Pavilion is the only architectural feature that contained relics. Although it was only a one-story stone column, it also provided some information that helps us imagine the pavilion’s beautiful pre-war appearance. According to the Yeonggeon Chronicle, the construction of the pavilion did not begin immediately at the empty site like with the other villas; instead, the early Joseon building techniques were studied by examining the remains. All of the remains were reused as well, giving birth to a new Gyeonghoeru Pavilion that became a marriage of two distinct architectural techniques, one from the fifteenth century and another from the nineteenth century. These details are reported in the Yeonggeon Chronicle.

The size of the pond was four times the size of the pavilion. In the actual construction process, the construction of the pond was more time-consuming and involved far greater complexity than that of the pavilion itself. It demanded careful engineering, waterway maintenance, masonry, gardening, and further civil engineering. Its masonry was especially challenging and dominated construction, much like the pavilion. For example, the open granite columns had to support the huge eleven wooden purlins on the upper floor.

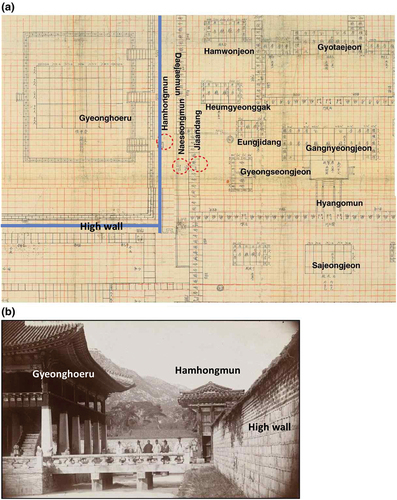

Until now, research on Gyeonghoeru (Yi and Jo Citation2005; Woo Citation2017) had focused on the architectural aspects of the upper half of the pavilion, such as Diagrams of the 36 Gung of Gyeonghoeru Pavilion (慶會樓全圖; ), in the collection of the National Library of Korea and at Waseda University, Japan. The book was the only record of the plan of Gyeonghoeru during the reign of King Gojong. It reveals how the relationship between the king and his subjects was expressed in architectural planning from a Neo-Confucian perspective. While it uniquely describes the composition of the Gyeonghoeru floor plan as a principle of Neo-Confucianism, it does actually cover the actual construction and engineering of the project.

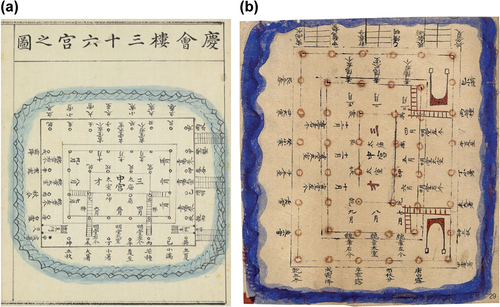

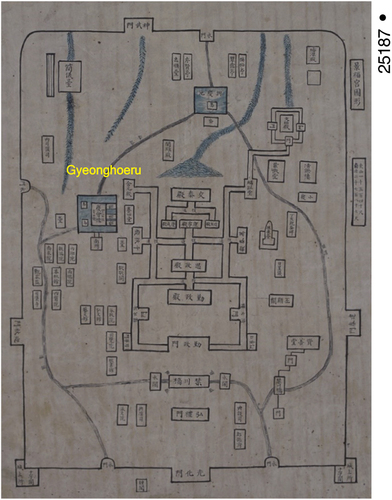

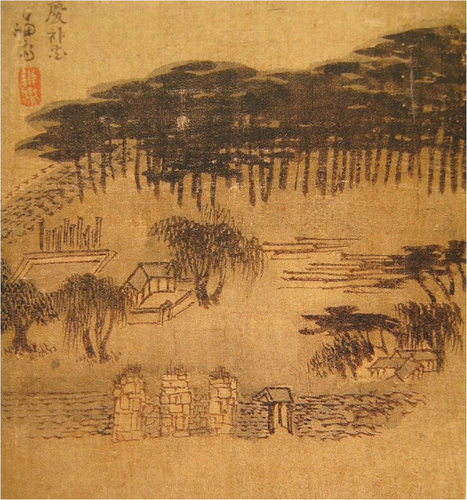

Figure 1. Gyeonghoeru Pavilion, Bukgwoldohyeong.

The current study focuses on the masonry involved in the nineteenth century reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung Gyeonghoeru as per the Yeonggeon Chronicle. The exhaustive details recorded in the Chronicle make it impossible to deal with all the content at once. Thus, the study elaborates on the content of the Gyeonghoeru stonework, a symbol of the Gyeongbokgung Palace in the Joseon dynasty. Moreover, we also cross-examine these details with data from the Yeonggun Ilgam (營建日監) and the Seungjeongwon Chronicle (承政院日記), the other existing records of the reconstruction.

We hope to understand the significance of the architectural history of the Gyeonghoeru reconstruction during the Gojong period by unpacking the masonry in particular, which took most of the time and financial resources available for reconstruction.

According to the Yeonggeon Chronicle, the Gyeongbokgung reconstruction of the Gojong period required far more stones than the original construction, especially for the foundations and flooring.

The palace architecture during the Gojong period was markedly different from the earlier Joseon period. First, ondol (an underfloor heating system) heating became more common during the late Joseon dynasty. Second, the palace buildings were equipped with a wide platform protruding from the front of the terrace stones (檐階). A staircase climbing the stylobate was installed on the side as well as on the front. Third, the techniques used for building a foundation had changed remarkably. The Gojong-era Gyeongbokgung did not deviate too drastically from where the early Joseon building was originally located. The excavation and foundation work were changed to a mat foundation by placing rectangular stones (Choi Citation2008), which increased the number of rectangular and rubble stones needed.Footnote3 Finally, the palace walls were constructed using stone. Before the destruction of war, not all of the border walls of palace buildings were made of stone.Footnote4 This changed in the nineteenth-century reconstruction when the walls separating the different areas in the palace were also planned to be built from stones. Toward the end of the construction, the date of the king’s move into the palace was tightly scheduled; hence, the walls between areas of the palace were temporarily built using mud. After the king moved, these temporary walls were rebuilt with stone. outlines the masonry work of the Gyeongbokgung reconstruction, including Gyeonghoeru. outlines Gyeonghoeru construction process of the the Yeonggeon Diary.

Table 1. Outline of Gyeongbokgung Stone Production Area and Logistics.

Table 2. Gyeonghoeru Construction Process.

3. The location and symbolism of Gyeonghoeru

3.1. Gyeonghoeru’s location

It is currently possible to enter the Gyeonghoeru’s premises without any barriers to the entrance through Sujeongjeon. However, when looking through Bukgwoldohyeong, Gyeonghoeru is seen to be surrounded by high fences, and the path toward it leads to Gangnyeongjeon (the king’s sleeping quarters), Gyotaejeon (the queen’s living quarters), Sujeongjeon (the office quarters for subjects), and Sajeongjeon (the office quarters for the king). This actually makes Gyeonghoeru less accessible.

The Gyeonghoeru-gi of Ha Ryun referred to Gyeonghoeru as the western pavilion of the hujeon (rear court room, Sajeongjeon), noting that the Gyeongbokgung Jegeosa (景福宮提擧司), the palace’s management office, reported that the western pavilion was leaning and in jeopardy. According to Gyeonghoerugi and Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, King Taejong did not simply repair Gyeonghoeru in 1413, but expanded significantly. He hoped it would be an architecture that could show the pride of Joseon to foreign envoys. However, Ha Ryun wrote that the king should run the country stably from the pavilion and treat his subjects with tolerance and intelligence.Footnote5

The construction of Gyeonghoeru during the Gojong period (r. 1863–1907) has a similar context. Jo Dusun, the prime minister, said to Gojong upon the completion of Gyeonghoeru that “this pavilion was called Gyeonghoeru because it was intended to bring good luck to the country and households, and that the sovereign and the subjects will be in harmony.”

Taejong (r. 1400–1418) and Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450) would spend the summer at Gyeonghoeru to escape the heat in the capital. The latter was known to conduct political affairs and business with a close public servant at the pavilion. There were many kinds of celebratory texts commemorating the completion of Gyeonghoeru, three of which still exist today, the texts of Sin Jawmo and Heo Jeon state that Gyeonghoeru was “a warm palace building” where the sovereign and kind subjects would discuss political affairs.Footnote6

At Gyeonghoeru, the internal court feasted for the Queen Dowager, and the royal relatives and royal son-in-law would pay their respects. Even among the palace members, royal relatives and close civil servants could access Gyeonghoeru only with the sovereign’s permission (Seok Citation2020). This made Gyeonghoeru part of the inner palace. The lower floor surface was composed of jeondol (traditional floor paving bricks) because the pavilion hosted the king and the royal family.

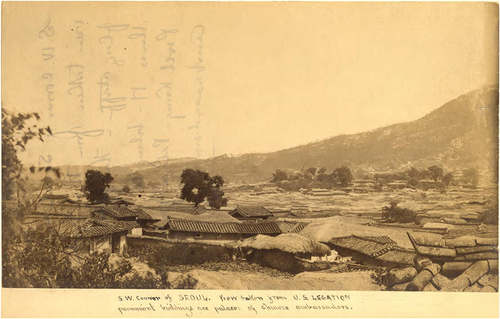

The pictures of Gyeonghoeru taken by the First Korean Diplomatic Mission to the United States in 1884 (twenty-first year of Gojong’s reign), Percival Lowell, confirm that the vicinity of Gyeonghoeru was blocked by high walls and doors (see ).

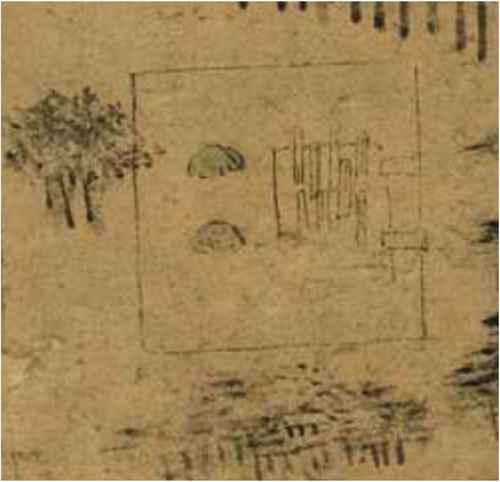

Figure 2. Gyeonghoeru thirty-six palaces map of Diagrams.

During the Japanese occupation, Gyeongbokgung hosted the Joseon Industrial Exhibition. The border walls that surrounded Gyeonghoeru, were demolished, and a bridge was constructed over the pavilion pond.

3.2. Motivations for Gyeonghoeru expansion and construction

Gyeonghoeru was originally referred to as a western pavilion, but it was expanded to its current size by Park Ja-cheong (朴子靑) in the thirteenth year of Taejong (1413), as documented in Ha Ryun’s Gyeonghoerugi.

Park Ja-cheong surveyed the land and extended the rectangular area slightly toward the west. Based on this site, it was constructed to be larger. Because the soil was moist, they dug a pond surrounding the pavilion. After its completion, His Majesty went up the pavilion and is recorded to have said, “I was hoping to retain the original form and fix the structure. However, is this not greater than what it was previously?” In response, Park Ja-cheong said, “Your Highness, we were afraid that it would lean and become dangerous, so we built it like this” (Ha Ryun, 1478 Gyeonhoerugi, Dongmunseon vol. 81).

The western pavilion that was originally built during Taejo’s reign was small; the water of the pond would drain and leave dead fish on the surface. Upon hearing the report of the Gyeongbokgung Jegeosa,Footnote7 Taejong made Gongjopanseo (Head of Construction and Transportation) Park Ja-cheong responsible for the reconstruction. Park Ja-cheong fixed the water works such that the water that came from north of Gyeongbokgung would pool into the pond; he expanded the pond and the pavilion under the pretext of repairs, right before the farming season. In the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, it is stated that it was originally Taejong’s intention to rebuild Gyeonghoeru to welcome Chinese envoys, unlike what is stated in Gyeonghoerugi. Two things can be inferred from these records – first, architect Park Ja-cheong’s abilities, and second, Taejong’s patronage.

Taejong was the third king of the Joseon dynasty and settled Hanyang (漢陽Seoul’s old name) as the capital of the dynasty (Choe Citation2019).Footnote8 He pursued powerful royal authority, and used construction as an act of governance. The expansion of Gyeonghoeru was carried out by King Taejong despite strong opposition from officials. Taejong was also interested in diplomatic relations to foster stable domestic politics (Kim and Cho Citation2016). The Ming dynasty’s diplomatic rituals were adopted, and diplomatic facilities such as Taepyeonggwan (太平館) and Mohwaru (慕華樓) were built during his time. This was why King Taejong pushed through the expansion work of Gyeonghoeru despite opposition from scholars that it was excessive construction, much like the situation during the renovation of the Gyeonghoeru of Seongjong (r. 1469–1494), which was opposed by the Saheonbu (Office of Inspector General). According to records stating that the Gyeonghoeru columns were built on November 5, the fourth year of Seongjong’s reign (1473), this reconstruction was extensive and required reconstructing the columns of the pavilion.Footnote9 However, the rectangular ponds remained the same. Based on the poems of envoys and articles of the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, images of dragons, clouds, and flowers were carved into the columns; the eaves and roof formed a dome; and copper decorative tiles called mangsae were placed. Envoys from Ryukyu and Ming left poems that extolled the scenery of Gyeonghoeru and its surroundings.Footnote10

Gyeonghoerujeondo (慶會樓全圖; diagrams of the 36 Gung of Gyeonghoeru pavilion), written by Jeong Hak-soon in the second year of Gojong (1865), explains the principles underlying the architectural planning in the reconstruction of Gyeonghoeru. Based on the foundation stones of Gyeonghoeru, Jeong Hak-soon interpreted the logic of Park Ja-cheong’s planning of Gyeongbokgung during the Taejong period.

According to Gyeonghoerujeondo, each column, window, and door of Gyeonghoeru was in the Neo-Confucian style. As a middle palace of heaven, earth, and man, he distinguished each row of columns with some difference between each row. The 48 columns of Gyeonghoeru are made up of 24 columns and pillars, and the second bay 12 rooms symbolize one year and 12 months, and the 64 doors symbolize 64 possible sets. In addition, the length of the column, the number of rafters, and the shape of the column are all related to the number of the Yi Jing (易經). The most central part of Gyeonghoeru is the seat of the king who oversees all these changes. Gyeonghoeru is the place where the king and his subjects meet with virtue, and it is an architecture that symbolizes the authority of the ruler, the king (see ).

Jeong Hak-soon’s Gyeonghoerujeondo is, however, not mentioned in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty or the Yeonggeon Chronicle. According to the postscript of the book, Jeong Hak-soon organized the material as heard from his ancestors, and the books are a culmination of long research. He dedicated the book to the Yeonggeonso (營建所; a construction site), indicating the possibility of a formal discourse. However, while the Yeonggeon Chronicle focuses on technicalities in the field or the receipt and payments of materials, it does not contain details on architectural planning as such.

3.3. Gyeonghoeru in paintings and maps

3.3.1. The placeness of Gyeongbokgung Palace

The restoration of Gyeongbokgung Palace was a long-cherished dream of the royal family, but the will to restore it had long been dampened. Joseon relied on agriculture for its economy, but the seven-year war had devastated farmlands. The kingdom’s treasury could not afford post-war projects, such as rebuilding Gyeongbokgung Palace. Instead, kings constructed smaller, detached palaces (Lee Citation1991).

King Sukjong (r. 1674–1720) sought to restore Gyeongbokgung Palace as the main palace of the Joseon dynasty. His plan to restore it was met by opposition from ministers, who referred to him as “Yonsan-gun,” the epitome of tyranny (r. 1494–1506).

Later, King Yeongjo (r. 1724–1776) visited the old district of Gyeongbokgung Palace several times, organized a ceremony (civil service examination and royal rituals) and used it as his own governing space. State examinations and royal rituals were held at the Gyeongbokgung Palace. King Yeongjo clarified the perception that Gyeongbokgung Palace was the king’s space, and made subjects investigate the site of the pavilion in Gyeongbokgung Palace, and then recorded its function and status (Yoon Citation2005) (see ).

Figure 3. Site Plan of Gyeongbokgung Palace.

At the time, Gyeongbokgung Palace evoked intense and complex emotions among ordinary people. The palace in the early Joseon dynasty was a place of honor and pride but became a source of lamentation and resentment after the Japanese invasion of Korea in 1592. A century after the war, it began to be referred to as a place of pleasure. Flowers, silkworms, pine trees, and glasses appear in the verses honoring the palace (Kim Citation2016).

The Joseon dynasty began preparing for the restoration of the Gyeongbokgung Palace after the reign of King Yeongjo. The royal family, as well as their subjects, began to make personal records of the palace. This is the case with Yu Deuk-gong’s (1748-1807) Chunseongyugi (春城遊記; a record of Yu’s trip to Seoul in the Spring).Footnote14 (Yu, Citation1780) These efforts of generations fostered more interest in Gyeongbokgung Palace, and ultimately secured the legitimacy of the restoration.

3.3.2. Gyeonghoeru, the symbol of Gyeongbokgung Palace

The stone columns of the lower floors of Gyeonghoeru remained after the Japanese invasion. They symbolized the sacking and destruction of Gyeongbokgung, until the Gojong reconstruction. It represented the image of Gyeongbokgung in late Joseon documents, paintings, and maps. The soldiers of Sugung (守宮, palace guards) protected Gyeonghoeru, and laymen imagined the space in various cultural and ideological manners.

King Yeongjo, in particular, had keen interest in Gyeongbokgung. At the time, Gyeongbokgung Gyeonghoeru pond was added as a location for the ritual for rain, with lizards, along with Mohwagwan Mohwaru and Changdeokgung Chundang ponds. Children participated in the ritual, with songs composed by the king’s father, Sukjong. Gyeonghoeru became more than a representative image of Gyeongbokgung: because the royalty held rituals to bring good luck here, it was embedded in the memory of the royal family, the lord ministers, and the subjects.

The “Gyeongbokgung Palace Picture” drawn by Jeong-seon (鄭敾, 1676–1759), is a realistic representation of the remnants of Gyeonghoeru. Next to the Gyeonghoeru pond, eleven stone columns are illustrated. Overgrown willow trees and pine trees are shown in the empty site of Gyeongbokgung.

Yu Deuk-gong carefully detailed the status of Gyeonghoeru during Yeongjo’s reign in Chunseongyugi as well.Footnote11 The stone bridge connecting the Gyeonghoeru Pavilion to the stonework was shaky, and Yu Deuk-gong is reported to have sweated as he crossed it. This way, it was possible to determine that, since the early Joseon period, Gyeonghoeru had retained the composition of the pavilion on top of the stonework, which rested on top of the rectangular pond, and the structure was connected to the shore with a bridge (see ).

Figure 4. Site Plan of Gyeongbokgung Palace.

Yu Deuk-gong further stated that, out of the forty-eight stone columns, eight were broken. The length of the bridge was three gil (about 450 cm). The exterior columns were referred to as square columns, and the inner columns as circular columns. He also stated that the cloud and dragon patterns were engraved on the columns during the Seongjong period. In the eighteenth century, when Yu Deuk-gong was active, Gyeonghoeru was depicted as having eight columns and two islands on Gyeonghoeru pond in “The great Map of Seoul, Joseon Dynasty.” This appears to be consistent with Yu Deukgong’s records (see ).

Figure 5. Part of Gyeonghoeru from the great map of Seoul (都城大地圖).

4. Gyeonghoeru construction

4.1. Participants of the Gyeonghoeru construction

4.1.1. Gyeonghoeru construction supervisor, Yi Gyeong-ha

Yi Gyeong-ha (李景夏, 1811–1891)Footnote12 directed the construction of Gyeongbokgung, and, during this time, became leader of Geumwiyeong (禁衛營, a military camp, which was established in the center in the late Joseon Dynasty to guard the king and defend the capital) and Hullyeondogam (訓鍊都監, another military camp in charge of defending the capital during the Joseon Dynasty). He also held the position of the governor of Suwon, which meant he oversaw the investigation of the pillage of the tomb of Prince Namyongun (南延君. King Gojong’s grandfather). As he conducted the investigation, he would also visit Seoul the same day to direct the reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung. He clearly played a significant role in the reconstruction of Gyeonghoeru. At Nakdong, the place of his residence, Yi Gyeong-ha discoursed with Catholic missionaries, and was known as Nakdong’s “king of the underworld.” (Kim, Citation2005) He was subsequently appointed as the minister of construction and transportation and the governor of Hanseong (Seoul’s old name). During the Im-O Military Rebellion of 1882, he was a military commander, and eventually exiled to Gogeumdo in Jeolla-do as punishment. During this time, Ching’s diplomat, Chen Shu-tang (陳樹棠) took over the site of Yi Gyung-ha’s home, the location of the current-day Chinese embassy (see ).Footnote13

Figure 6. Chinese Embassy in southwestern Seoul viewed from the U.S. Embassy.

Geumwiyeong quarried sixteen stone columns from Samcheongdong and moved them to the construction site at Gyeongbokgung with three hundred workers laboring over twenty-four days. The leader of Geumwidae, Yi Gyeong-ha propelled the project forward and gained public acknowledgement. He eventually became the official responsible for the movement of the arched lower stone of Geonchunmun (建春門; Gyeongbokgung Palace east gate). He was also a royal scribe to Geonchunmun. At the time, the directors of construction for the Gyeongbokgung Palace gates were also scribes who wrote the signage of the gates they were individually in charge of.14

Yi Gyeong-ha directed the latter half of the construction of Gyeongbokgung Geunjeongjeon Hall (勤政殿, the Throne Hall). He quickly assessed the damage caused by the fire at Changuigung (彰義宮, where Youngjo used to live before he became king), which would have dramatically affected the conclusion of Gyeongbokgung’s construction. He thus avoided a potentially devastating setback to the construction. Yi Gyeong-ha also made numerous financial donations and assisted greatly in the reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung.Footnote15

4.1.2. Management of the mason Paejang (牌將; responsible for execution)

The refining and installation of roughly trimmed stone materials in the workshop is called ipbae, and the worker in charge of such work is called the ipbae stoneworker. The stone has a high transportation cost, and the structure of Gyeonghoeru’s first floor is only made of stone. There is no scope for mistakes, as it would require substantial labor and time to transport and trim the stone again. Thus, the masonry work required highly skilled stoneworkers. Kim Jin-sung and Yi Sa-bok were the master craftsmen responsible for the trimming and ipbae of the stonework in Gyeonghoeru. Both artisans are historically important masonry specialists. Paejang Kim and Lee were in charge of not only Gyeonghoeru, but also all the stonework of Gyeongbokgung Palace. Kim was later named the leader of the construction of Gyeonghuigung Palace.

Unlike Kim, Yi Sa-bok was awarded the role of chief governmental construction worker in the construction of artillery at Incheon, and a sanneungdogam (山陵都監; Temporary Organization for the Construction of the Tomb of the King and Queen) after the reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung. He was not appointed as a byeonjang but as the Deokjeok-cheomsa (德積僉使; Defensive Captain of Deokjeok) by His Majesty’s order in the seventeenth Gojong year (1880).

Although he was not a chief government construction worker, a mason from Pyeongyang, Kim Ji-hyun, had died at the site the spring of fourth Gojong year (1867). In response, the dogam (都監; Temporary Government Offices for the Construction of Gyeongbokgung Palace) paid ten nyang (the currency unit of the Joseon dynasty). In October of the same year, his son came to collect the remains to bury his body in his hometown, and he was paid ten more nyang. In this way, the construction of the pavilion took many lives, but the authorities were quick to offer money for burial at home.Footnote16

The extent of masonry, even at the tail end of the reconstruction, at Gyeongbokgung meant that the project always seemed far from completion. Each palace building still lacked stone material for ondol, leaving the buildings incomplete. Stone material for fences and stone pavements that were to be laid at the court of the main palace had not even arrived. These drawbacks continued even one month away from the date of the king’s move into the dwelling quarters, that is, the fifth year of Gojong, in May of 1868. The Yeonggeon Chronicle notes that the masons were the most urgently needed, and the staircase stones of each building and the corridor had still not been placed. The masons at the Nampo of Anseong (in Gyeonggi province) had also run away. Indeed, at the end of the construction, public notices were frequently sent to provinces to capture runaway workers, stone masons, gigeo-jang (an artisan who uses a big saw), ingeo-jang (an artisan who uses a small saw), roof tilers and metalworkers.

4.2. The masonry of the Gyeonghoeru pond

4.2.1. Removing vine roots and dredge construction

Prior to Gyeonghoeru construction, dirt accumulated in the pond had to be dug out. The dredging of the Gyeonghoeru pond started by removing the vine roots twenty days after the Queen Dowager Jo’s Gyeongbokgung reconstruction plans were announced.Footnote17 It took nine thousand laborers fourteen days to complete this labor. The vines had grown into a dense thicket, and had to be cut using a shovel, and then pulled out using ropes. The Yeonggeon Chronicle details this process, reporting that the large vine roots looked like rafts, and the small vine roots appeared as if they were cushions. Only once the vines had been cleared could construction of the pond begin. The mud that was dredged out along with the stubborn and overgrown, thick vines was used to fill the hole at the fence behind Gyotaejeon (交泰殿; the residence of the queen) and Munsojeon (文昭殿; shrine for the spirits of the dead king and queen). This mud had good integrity and would not collapse under the weight of people or after heavy rain.

The main dredging occurred in the second year of Gojong on 5 May 1865. Five days after the dirt was removed, the surface of the pond came into view. As the workers dug deeper, the rotting smell of dirt became too pungent for work to continue digging using baskets meant to carry dirt. Military soldiers were called. The soldiers lined up and dug out the dirt using wooden baskets, passing these baskets from one man to the next, like a “a colony of ants.” The Yeonggeon Chronicle offers a lively report of the construction, not limited to only the technicalities.Footnote18

4.2.2. Surveying the early Joseon stone pile-up

On Intercalary 12 May 1865, a month after the workers had started digging up the dirt, the stone foundations were revealed and specialists began surveying the old sites: Only three stone columns remained out of the eight columns that were present until Jeongjo’s reign (1776–1800). In most of the stone material, hun-dok (poison that permeates old stones) was deeply embedded, so only a select few were to be repurposed for the boundary stairs. Ten days later, it was decided to polish all the old stone materials and use them for the stairs under the eaves. The current stairs under the eaves in Gyeonghoeru are stone columns from the early Joseon period.

During the survey of the old sites of Gyeonghoeru, Do-gam praised the architectural techniques of the forefathers, especially Park Ja-cheong (朴子靑).Footnote19 In addition to solving the problem of the building being almost under collapse, Park Ja-cheong expanded Gyeonghoeru from a western pavilion to its current appearance.Footnote20 The stonework from the early Joseon period was so skillfully held together that, when they hammered in nails to check if water penetrated into the inner parts, they appeared clean and without any hint of water damage.Footnote21 Consequently, it was decided to maintain the stonework techniques from the early Joseon period. The stone wall technique used in the pond’s edifices, including Hyangwonjeong (香遠亭), which were built during the Gojong period (r. 1863–1907), were built by stacking natural slopes that were raked back; however, the masonry for the Gyeonghoeru pond was done with a perpendicular pile-up, which is characteristic of the pond border masonry of the early Joseon period (Yi et al., Citation2001) (see ).

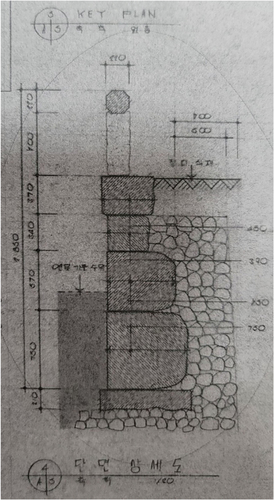

Figure 7. Rock Revetment restoration project (1984). Cross section of the northern part of the stonework used as shore protection in Gyeonghoeru.

If Park Ja-cheong solved the drainage issue of Gyeonghoeru pond with a gradient adjustment and intricate masonry construction, the Gyeonghoeru reconstruction of the Gojong period added eomseok. Eomseok is a material that is used for foundation construction; it is also called chojidaseok (the lowest ground stone). The Chijangjo of Gukjosangnyebopyeon (國朝喪禮補編a book on royal rituals and procedures) describes eomsoek as a material commonly used for the sovereigns’ graves. It has a height of one ja (about 30.7 cm in Gyeongbokgung construction), length of 4.5 ja, and width of 1 ja. The upper and side surfaces of eomseok are consistent,Footnote22 though this cannot be confirmed currently because they are no longer visible after the construction. The existence of eomseok can be confirmed at the excavation site of Euijeongbu (議政府; the highest administrative agency of the Joseon Dynasty), which was rebuilt at the same time as Gyeongbokgung (see ).

4.2.3. Mansesan masonry and levee construction

The stone piling on the the first of two Mansesans (artificial hills) was completed with seven hundred and twenty-eight masons over fourteen days.Footnote23 The pair were piled up in four layers, each with a height of 5 ja, north–south distance of 15 ja, and east–west width of 20 ja, and were finished with a covering of Pogonatherum crinitum grass (see ).

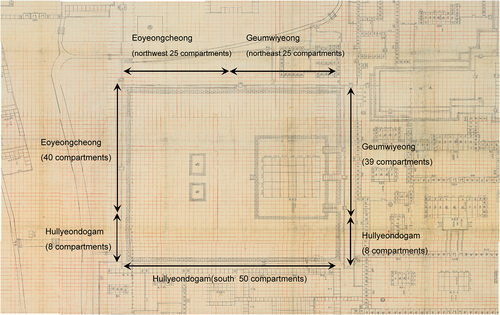

Figure 9. The responsible areas for the three commands for the Gyeonghoeru embankment construction; Bukgwoldohyeong.

The levees for the pond had the following dimensions: east–west 47 kan and north–south 50 kan. The Three Commands, Geumwiyeong, Eoyeongcheong, and Hullyeondogam (on Guards of Hanyang) divided areas based on the function of each command. shows the details of the records.

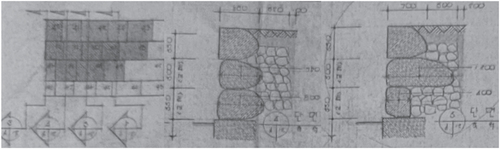

The height of each levee was 4.5 ja, and in each area, ten eomseok were set in place; further, walls were set in place by layering them four times. One layer had four stones, and a stick of 4 ja was installed.Footnote24 These walls were four stories high – from the first story above the eomseok, to the third story, three layers of two piles per story and a rectangular stone of four cheoks. In the fourth story, there was a single layer comprised of four stones. This record can be confirmed from the blueprint surveying the pond stonework right after the water was drained out (see ).

4.3. Gyeonghoeru stone construction

4.3.1. Quarrying

Because stone is difficult to transport, unless it has a special purpose, (uch as a flag stone or ondol) it was quarried from nearby areas to the construction site. The stone construction for Gyeonghoeru used the largest quantity of stone in the construction of Gyeongbokgung. The stone columns had different locations from where they were quarried based on each command’s function in the Three Commands: Geumwiyeong was quarried from Samcheongdong, Eoyeongchoeng from North Yeongpungjeong and Buram, and the Capital Command from the east of Eoyeongcheong. According to the Yeonggeon Chronicle, it took a day and a half for three hundred Geumwiyeong soldiers to cut a stone for one stone column from Samcheongdong. Transportation of stone materials was the most difficult task. “Rough work or first work,” which was the process of trimming down the weight of the stone at the location of quarrying, was conducted for this reason. The first work on stone columns for Gyeonghoeru was conducted based on a predetermined size. These stone columns were to be the exterior and inner columns, and accordingly trimmed at the location of quarrying.Footnote25

4.3.2. Transport of stone

To safely transport stone materials, preliminary work on fixing the bridges and streets was necessary. For instance, when moving the arch foundation stone for Gwanghawmun, the Hyejeonggyo bridge collapsed, and two masons were injured.Footnote26 The dogam (directorate) placed wooden panels and layered it with soil to make it function as an embankment on all streets where wood and stone material were transported.17 In particular, when workers passed through an incline, they needed to pay attention so that the center of gravity would not pull toward the front. To prevent this, they pushed and pulled on each side of the low mound. Because the transport of stone material was not possible by manpower alone, carts were used. Different carts, such as daegeo (大ं; a cart pulled by 40 cows), pyeonggeo (平; a cart pulled by four or eight cows), and donggeo (童; a four-man cart), which w ere large to small carriers, were used based on the size of the stone.,Footnote27, Footnote28

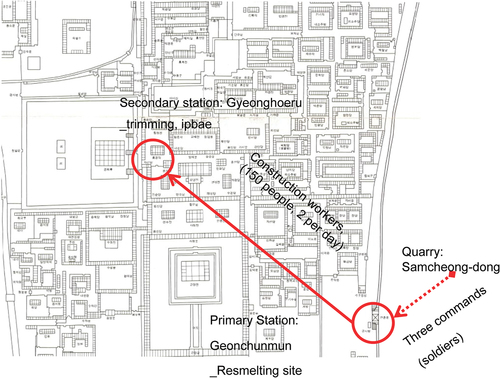

The transported stones were stored within Geonchunmun Gate, which was the first workstation. For assembly, the stones were transported to the Gyeonghoeru levees, which was the second workstation, where the stones were trimmed. For transport from Geonchunmun Gatr to Gyeonghoeru levees, one hundred and fifty construction workers moved two stones daily (see ).Footnote29

Figure 11. Transportation of stone.

We can infer that the Three Commands started moving the pavilion column stones by cart six months after the start of the construction. They learned how to transport these stones using cows and carts, and the roads were fixed so that the carts could pass through.Footnote30 To transport one pavilion column, one daegeo was required, and to transport one daegeo, forty-five cows were needed. The Yeonggeon Chronicle records the process of moving the stone by daegeo in detail. When moving through an incline, half of the forty-five cows would move in the direction of the incline, and the other half in the opposite direction; in doing so, their speed could be controlled.

4.3.3. Placement of foundation stones and installation of columns

The main stone trimming work began twenty-one months after the construction began. Stone trimming and stones were released for the placement of the foundation stone at the second workstation next to the levees of the Gyeonghoeru pond. Ten days later, a foundation stone ceremony was conducted, where the responsible official, Yi Sa-bok, was assigned as a service manager. From the open space between the rooms (eokan) to the edge columns, forty-eight stone columns were built in three and a half days. The edge columns were bangju and the columns for eokan had pyeonjeongcheol wrapped around them, and their appearance can still be seen today. The records show that the metal work that covered the columns was broken because of lightening, indicating the existence of pyeonjeongcheol since the early Joseon period (see ).Footnote31

4.4. Carpentry and other construction

4.4.1. Timber cutting and transport

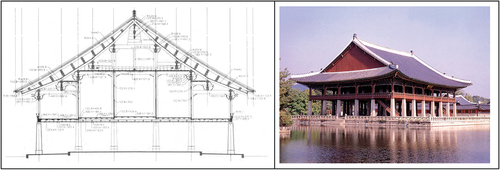

On 12 April 1867, the carpentry of the second floor began. The ridge beam was raised to complete the framework of the roof, with an eleven-purlin structure of thirty-six kan, on April 20. The assembly progressed quickly because the wood was polished beforehand (see ).

Figure 13. Cross section and photo of Gyeonghoeru. Cultural Heritage Administration, The survey and repair report of Gyeonghoeru, 2000, 103.Photo by author, 2016

Moving stone is one of the most challenging tasks in masonry, while finding the ideal wood for constructing inner columns and girders is the most difficult part of wooden construction. The precincts of royal mausoleums sent carpenters, not officials, to cut down trees and deliver the timber overnight. They were able to find this wood from Sungangwon (順康園), the tomb of King Seonjo’s concubine, but there were not enough men to transport the timber. The capital protection force then sent carts. This phase of construction thus took place at a rapid pace.Footnote32

4.4.2. Rafter and roof tile construction

Gyeonghoeru is a second story building structure with double-eaves and resting hill roofs. Its corners, where the eaves are cantilevered and curve upward, had to be stable. The Yeonggeon Chronicle shows the construction of Gyeonghoeru rafters as an exemplary case of construction. It was prepared by placing nails on the rafters’ heads, which were then assembled in a curved shape without direct vertical support.

However, Geunjeongjeon Hall (勤政殿, National Treasure No. 223, the Throne Hall), which was about the same size as Gyeonghoeru, was reconstructed because the rafters rested upon wooden brackets that were fitted against the heads of the columns during the roof tiling process.

In the construction of Geunjeongjeon, the rafters were hung higher than their original location in order to prevent them from sliding down because of the weight of the roof, as well as to prevent them from pressing down against the wooden brackets. Despite this preparation, the rafter separated, creating an open space during the roof tiling. Reconstruction was inevitable. The Yeonggeon Chronicle states that, for the construction of Geunjeongjeon, workers had to use the same methods as in Gyeonghoeru – that is, they had to secure the rafter using a nail and another bent nail. The writer opines that “for palace buildings, it is best to use this method to hang in the rafter.” The roof construction method of Gyeonghoeru was considered to be useful at the site; at the time, it wasn’t a commonplace method.Footnote33

After the rafters were assembled, they were covered by wooden panels, and then straw bags and raised roof tiles. The roof incline was steep, so friction was used to prevent the roof tiles from slipping.

Gyeonghoeru was large in size, so the type of roof tiles and the number of tiles needed were decided at the start of construction.Footnote34 The roof tiles used in Gyeonghoeru covered 1,648 m2 in total area and because of their size (330 mm*420 mm*25 mm), special tiles and ones larger than regular roof type, needed to be created beforehand. The tiles that were left over after the construction were placed inside the bakgong (gable) and stored for possible future use for repairs. As a result, the most difficult work until the end of the Gyeongbokgung Palace reconstruction was the production of the roof tiles. The Yeonggeon Chronicle states that there were many official documents ordering local government offices to keep a record of the roof tilers, noting that many had deserted or not returned since the holidays.

4.4.3. Reuse of pre-existing materials

The Yeonggeon Chronicle shows cases of reusing pre-existing masonry in the stonework and the vicinity of the pavilion. The current Gyeonghoeru boundary stones are, indeed, the reused old Gyeonghoeru stone columns. Stone from the Ilyeongdae (sundial pedestal) in the Heumgyeongak site (a pavilion with a water clock) was removed and polished.

In February 1868, a balustrade was added to the square pond and nearby stairwells.Footnote35 To compensate for the lack of stone materials, the stone bridge near Yeongmijeong was demolished on 14 March 1868,Footnote36 and reused for the Yeongjegyo in Gyeongbokgung and for the stone bridge in Gyeonghoeru.

The Gyeonghoeru pavilion was on an island, so there had to be a bridge connecting it to the mainland and there are indeed three stone bridges in Gyeonghoeru, and one is connected to the Yigyunmun of Sajeongjeon. It is unique because it was a path reserved for the sovereign alone.

4.5. Gyeonghoeru, the place of good luck rituals

During the Gojong era, numerous fires delayed the construction of Gyeongbokgung. In one instance, woodworks and decorations that were waiting to be assembled were destroyed, forcing the woodwork for the windows to be outsourced.

Gyeonghoeru was perceived as the safest place from fires within Gyeongbokgung. During the major fire in Gyeongbokgung in the eighth year of King Myeongjong (1553), important books of Gangneyongjeon, Sajeongjeon, and Heumgyoengak were moved to a boat in the pond of Gyeonghoeru.Footnote37 Despite the fires at Gyeongbokgung, the materials near Gyeonghoeru were always safe.

Indeed, one event stands out to illustrate Gyeonghoeru’s protection from fire. Two months into the reconstruction, during the dredging of the Gyeonghoeru pond, a jade stone was discovered,Footnote38 engraved with the dynasty’s efforts to prevent manmade disasters such as fires. This stone, and its engraving, also symbolized that the construction of Gyeongbokgung was God’s will. This discovery gave divine legitimacy to the reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung. The stone’s discovery at the Gyeonghoeru pond, instead of a place like the king’s residence or the main hall, symbolized, at the time, the significance of Gyeonghoeru for the Joseon dynasty and Gyeongbokgung. However, historical records show that this event was especially manufactured by the Regent Daewongun (1820–1899)Footnote39 to raise public enthusiasm for the restoration of Gyeongbokgung Palace.

After the vicinity of the pond was somewhat organized, dogam prepared the ritual to bring in good luck and chase away bad luck (guiyangeuirye). For this purpose, a pair of specially made bronze dragons were discovered in the pond, near by stone pillars. Bronze dragons had been in production since the beginning of the reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung. The mold was produced in the second Gojong year on 20 August 1865. The blueprint shows that the ritual had been planned since the very beginning of construction. A pair of bronze dragons were placed below the stone column on 12 July 1867. One was discovered on the bottom of the Gyeonghoeru pond during dredging in November 1997 and is now a part of the National Palace Museum of Korea collection. In February 1998, duplicates replaced the original dragon in the positions.

It is in the culture of the royal family to host a ritual praying for good fortune. Because the state monopolizes the hosting of the ritual, the royal family can both exhibit its dignity in all pomp, while praying with the subjects for good luck (see ).

Figure 14. Bronze metal dragon excavated from Gyeonghoeru pond Time: 1865, Joseon.

In the railings of the bridge that connects the pond to the pavilion, the bulgasari, a fabled monster, was engraved to protect against disaster, one of the numerous additions to Gyeonghoeru that served to protect against fire (see ).

5. Conclusion

We examined the masonry construction of Gyeonghoeru during the reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung, which started in the second year of Gojong and continued for thousands of days. We especially focused on the pond and Gyeonghoeru, with its numerous stones and intricate constructions that offer a glimpse into masonry during the nineteenth century Gojong period. Our findings are summarized as follows.

First, the construction of Gyeonghoeru and the pond involved complex civil engineering, gardening, masonry, and carpentry. It continued for the entirety of the reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung. The dredging of the pond involved construction workers from across the empire and soldiers from the Three Commands. For the pond’s stonework, each construction sector was responsible for a different unit of Three Commands, which was responsible for cutting the stone before delivery.

Second, the assembly of carpentry on the top floor of Gyeonghoeru was done on site after pre-planning, and the polishing of the wood was completed beforehand. The ridge beam was raised within eight days after the columns were set in place. This was especially notable because it preceded the installation of the rafters and angle-rafters, the most structurally burdened parts of the eleven- purlin wooden structure.

Third, the Gyeonghoeru construction director Yi Gyeong-ha led the soldiers of Geumwiyeong for the polishing and transport of stone, the toughest part of the construction. Later, he directed the construction of Geunjeongjeon, taking charge of the stone construction, which required the manpower of soldiers. He also completed the construction of Geonchunmun Gate and the walls of the palace.

Fourth, the two responsible executors of masonry who participated in the construction of Gyeonghoeru also participated in the trimming and release of stones for all of the masonry constructions of Gyeongbokgung. They were the most skilled masons at the time. They also served as sanneung-dogam and composed part of the Incheon artillery. They were thus part of the major masonry construction of the Gojong era.

Fifth, Gyeonghoeru was a place for the sovereign and his subjects to seek harmony. Workers from all over the region, including Three Commanders, participated in its reconstruction. Through a good luck ritual hosted by the state, the monarchy was able to demonstrate its dignity and reassert the legitimacy of the reconstruction. The existence of the bronze dragon and reports of the jade stone support these points.

To conclude, Gyeonghoeru was a classic symbol of the foremost palace of the entire Joseon dynasty, even while Gyeongbok palace was in ruins. And Gyeonghoeru’s status reaffirmed the legitimacy of the palace reconstruction. So reconstruction was effected by gathering Joseon’s last capacity in the nineteenth century. This study is an architectural and construction analysis of Gyeonghoeru, which had been studied only from a political, social, and economic perspective.

The reconstruction of the Gyeonghoeru Pavilion at Gyeongbokgung Palace in the 19th century was a sophisticated project that required many complicated processes. Through this study, it was confirmed that there was a consensus among the people mobilized for labor and the collaboration of experts in Gyeonghoeru. Above all, I was able to confirm the names of the real people who participated in the stonework, and I was able to confirm the method of transporting the stone and the quarry map.

Most importantly, thanks to thorough investigation and verification, 14th-century building techniques have been preserved and can still be seen today. This attitude towards cultural heritage is still needed today.

Our work can supplement the construction studies of pavilions in the future. We hope that this study will show the way for fresh and unique perspectives on Gyeonghoeru.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bue-Dyel Kim

Bue-Dyel Kim is Curator, Ph.D. Cultural Heritage Repair Engnieer.

Notes

1 The banquets of the Ming and Qing dynasties were staged in the main palace building, which were cordoned off by columned alleyways. In contrast, the banquets at Gyeonghoeru were conducted on a pavilion. It was a relatively open space.

2 Only the second the of five volumes of the Yeonggeon Chronicle are held in the Korean collection. The Korean collection was translated by the National Institute of Cultural Heritage in 2013. Younggeon Ilgam, which is in the collection of the Land and Housing Museum, was translated by Jeong Jeongnam and Lee Sunhee in 2017 and published by the National Palace Museum. The copyright of Gyeongbokgung Palace Yeonggeon Chronicle belongs to Waseda University, Japan. The complete volume and original text of the Younggeon diaries can be found there. http://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wa03/wa03_05101

3 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle; August 17, fourth year of Gojong’s reign in 1867, 285.

4 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle; second year of Gojong’s reign on 26 May 1865, 121.

5 See the Sinjungdonggukyeojiseungram(新增東國輿地勝覽; Revised Joseon Humanities and Geographical Books) Vol 2., Gyeonghoeru of Note. 한국고전종합DB (itkc.or.kr)

6 During the Sejong era, banquets for civil servants close to the king were held at Gyeonghoeru, and poems by those who participated in the banquets have survived.

7 The Gyeongbokgung Jegeosa was an oversight body that was established in the third year of King Taejo’s reign in 1394. It was responsible for managing the materials and the locks of Gyeongbokgung. During the early Joseon period, the administrative organizations and systems of Goryeo were inherited, and these Jeojesa were later incorporated into the Gunjagam. (軍資監: The government office that was in charge of storing, managing, and exporting military supplies such as military rice during the Joseon Dynasty)

8 Taejo founded Joseon in 1392 in Gaegyeong (now Gaeseong in North Korea), the royal capital of Goryeo, and then went to Hanyang. Jeongjong, the second king, returned to the city, and it was not until King Taejong’s reign that he was able to return to Hanyang completely. Some scholars say that the two-capital system was operated at least until Taejong in the early Joseon period (see Choe Citation2019).

9 See The Annals of Seongjong, the first article dated 29 October 1474, the fifth year of Seongjong. The repair of the Gyeonghoeru during the Seongjong era took five months from when the decision to repair it was made (July 17, the fourth year of Seongjong) to when the blueprint was released (December 14, the fourth year of Seongjong). It took another ten months to move in (November 5, the fifth year of Seongjong). According to the December 14 article (December 14, the fifth year of Seongjeong), Seongjong tried to expand the pavilion into a three-story structure, but the construction was suspended owing to the construction of palace buildings, bad weather, and drought. (history.go.kr)

10 See The Annals of Seongjong, 12 May 1475, the sixth year of Seongjong and see also The Annals of Injong, the fourth article dated 27 June 1545, the first year of Injong (history.go.kr).

14 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle, July 12 and 14, 1865, the second year of Gojong, 184-185. Yi Geong-ha, the Geumwidaejang, was responsible for the construction of Gyeonghoeru and Geonchunmun Gate, and Yim Tae yeong, the training captain, for the construction of Gwanghwamun Gate. According to an article dated 26 January 1867, the fourth year of Gojong, eighteen gwe of stone columns were carried from Buksan under the direction of Yi Gyeong-ha. That day, Yi Gyeong-ha gave the soldiers thirty nyang as a prize.

11 Yu Deuk-gong, fifteenth book of Yeongaejip, Japjeo, in Chunseongyugi.

12 Yi Gyeong-ha (1811–1891) served as Geumwidaejang (general), Hullyeondaejang (captain), and Suwon Yusu (governor), shortly after Heungson Daewongun (興宣大院君; the father of King Gojong) came into power. Later on, he served as the Hanseongbupanyun (Mayor of Seoul) and Gongjopanseo (Minister of construction). During the Gapsin Coup, he was a loyal official to the monarchy: He helped the Queen Dowager Jo, Empress Myeongseong, and Sunjong, who was the prince at the time, to flee his son Yi Beomjin’s home. He led the military, held key positions, and was responsible for the security detail of the monarchy.

13 Later, Yi Gyeong-ha(李景夏) became the ambassador to the United States. He was the first permanently stationed ambassador to Russia. During the Gapsin coup of 1884, he helped Empress Myeongseong flee to the home of his son Yi Beomjin(李範晉; 1852-1910) Yi Beomjin committed suicide in 1910 at the time of the Japan–Korea Treaty. His grandson Yi Wijong was one of the three members that participated in the Hague Convention of 1907 and later took part in the Bolshevik revolution.

15 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle, 4 January 1866, the third year of Gojong, 359. Yi Gyeong-ha, the Geumwidaejang, donated over 500 nyang received by Jongchinbu.

16 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 2, 16 September 1867, 323. At the time of the drafting of sangnyangmun for Gyeonghoeru (20 April 1867), 1,840 artisans and 1,737 construction workers participated in the construction of Gyeonghoeru.

17 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle, 2 April 1865, the second year of Gojong, 44-45.

18 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle, 10 May 1865, the second year of Gojong, 104.

19 See “The Annals of Gojong,” the third article dated September 10, the second year of Gojong, and the first article dated on July 2, the fifth year of Gojong.

20 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 2, 13 September 1867, the fourth year of Gojong, 317.

21 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 1, 13 January 1866, the third year of Gojong, 363.

22 See the Research Society of Yeonggeoneugye, Yeonggeoneugye, 2010, 913.

23 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 1, Intercalary, 21 May 1865, the second year of Gojong, 141.

24 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 2, 1 July 1866, the third year of Gojong, 42-43.

25 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 1, 26 May 1865, the second year of Gojong, 204.

26 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 1, Intercalary, 4 May 1865, the second year of Gojong, 130.

27 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 1, Intercalary, 3 May 1865, 129. The workers moved with two carts, with twenty-five cows for each cart.

28 Hwaseong Songyouk Eugye (華城城役儀軌), 172–174., https://www.gogung.go.kr/ancientBooksView.do?bbsSeq=6175&bizDiv=2

29 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 2, 26 January 1867, 155. Construction workers carried all the stone materials to the Gyeonghoeru embankment. On the same day, Yi Gyeong-ha (then Hwaseong Yusu(華城 留守; concurrent position, Hwaseong is the city of Suwon’s old name) awarded them thirty nyang as a prize.

30 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 1, 3 November 1865, 295.

31 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 1, 7 February 1867, the fourth year of Gojong, 160.

32 Actually, timber could not be cut at the royal mausoleum, or the nearby whaso (reserved area for royal tomb). If this was unavoidable, an official should be sent after giving public notice.

33 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle 12 September 1867.

34 see the Yeonggeon Chronicle, 19 August 1865.

35 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 2, 5 February 1868, 410.

36 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 2, 14 March 1868, 427. Yeongmijeong does not appear in the texts, although the oral tradition points this to be the Yeongdogyo bridge and Jeoncheongyo bridge in front of Yeongdosa Temple. It was built in stone during the Seonjong era. Its material was requisitioned during Gojong, and it was rebuilt in wood at the time of the Gyeongbokgung restoration.

37 See “The Annals of Myeongjong,” the first article dated 14 September 1553, the eighth year of Myeongjong.

38 See the Yeonggeon Chronicle Vol 1, 25 May 1865, 119

39 The father of King Gojong. In the early days of his ascension, King Gojong wielded power in place of King Gojong.

References

- Choe, S.-W. 2019. “King Jeongjo’s Construction of Hwaseong City and the Design of Separate Capital.” The History Education 151: 263–300.

- Choi, I.-H. 2008. Archaeological Research on the Site of Gyeongbokgung Palace. Master’s th., Graduate School of Pusan National University.

- Cultural Heritage Administration. 2000. “Gyeonghoeru Survey and Repair Report”.

- H-R, 1478. “Gyeonhoerugi.” Dongmunseon. 81: 2127–2130. itkc.or.kr Accessed 31 May 2021.

- Kim, H. 2005. “Life and Death of Spiritual Forefathers in Suwon during the Persecution.” Church Historical Studies 2: 93–131.

- Kim, Y.-T. 2016. “About the Image of Gyeongbokgung Palace on the Chinese Poetry in Joseon Dynasty.” Dongyang Hanmoon Association 43: 103–127.

- Kim, B.-D., and J.-S. Cho. 2016. “A Study on the Taepyeonggwan, Mohwagwan and the Architects Contrived These Architectures as Shown in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty of 15C.” Journal of Architectural History 25 (4): 19–29. doi:10.7738/JAH.2016.25.4.019.

- Kim, B.-G., and D-H.Kim. 2007. Gyeongbokgung Palace Gyeonghoeru, Korea’s Beauty. Finding the Best Art, 194–207. Seoul: Dolbege.

- Kim, B.-D., and J. J-S. 2020. “A Study on the Construction of Gyeonghoeru in Gyeongbokgung Palace during Gojong’s Second Year of Reign (1865).” History of Architecture Research 29 (6): 101–113.

- Lee, K.-G. 1991. “The Reconstruction of Kyungbok Palace in 1865–1867.” Architecture 35 (2): 30–33.

- “National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage.” Joseon Ancient Books 10: 1377. nrich.go.kr Accessed 3 September 2019

- Seok, J. 2020. A study on the architectural characteristics of the palace banquet space during the Joseon dynasty. PhD diss., Hanyang University.

- Seoul Historiography Institute. 2019. “Gyeongbokgung Palace Yeonggeon Chronicle. Seoul Historiography Institute.” Accessed 31 May 2021)

- University of Wisconsin Milwaukee /Digital Library. Accessed 3 April 2020) https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agsphoto/id/226/rec/19

- Woo, J. 2017. “Explanation and Research of Gyeonghoerujeondo.” Architectural History Research Data Collection 26 (3): 69–78.

- Yeonggeoneuigwe Research Society. 2010. “Yeonggeoneuigwe.” Dongnyeok. Seoul

- Yi, S.-M., et al. 2001. “A Study on the Construction Techniques of Korean Palaces’ Pond Edifices.” Journal of the Korea Landscape Association 29 (1): 124–13.

- Yi, S.-H., and I.-C. Jo. 2005. “A Study on the Logical System of the Architectural Planning of Gyeongbokgung Palace Gyeonghoeru.” Architectural History Research 14 (3): 39–52.

- Yoon, J. 2005. “Events and Ceremonies Held in the 18th Century, at the Vestige of the Gyeongbok-gung Palace (景福宮 遺址).” Seoul Studies 24: 191–225.

- Yu, D. G. 1780. “Fifteenth Book of Yeongjaejip.” Japjeo, in Chunseongyugi (春城遊記). itkc.or.kr (Accessed 31 May 2021) https://db.itkc.or.kr/dir/item?itemId=MO#/dir/node?dataId=ITKC_MO_0579A_0160_010_0010&solrQ=query%E2%80%A0%EC%B6%98%EC%84%B1%EC%9C%A0%EA%B8%B0USDsolr_sortField%E2%80%A0%EA%B7%B8%EB%A3%B9%EC%A0%95%EB%A0%AC_s%20%EC%9E%90%EB%A3%8CID_s$solr_sortOrder%E2%80%A0USDsolr_secId%E2%80%A0MO_AA$solr_toalCount%E2%80%A02USDsolr_curPos%E2%80%A00USDsolr_solrId%E2%80%A0GS_ITKC_MO_0579A_0160_010_0010